In the high-stakes world of pharmaceutical intellectual property, where a single patent can shield billions in revenue and a decade of research, the tools we use to navigate this complex landscape are not just a matter of convenience—they are a matter of corporate survival. Enter Google Patents. With its familiar, clean interface, its promise of access to over 120 million patent publications from more than 100 patent offices worldwide, and an unbeatable price tag of zero, its allure is undeniable.1 It has, without question, democratized access to a universe of technical information that was once the exclusive domain of highly trained specialists with expensive subscriptions.3

But herein lies a dangerous paradox. The very simplicity that makes Google Patents so appealing creates a powerful and perilous “illusion of thoroughness”. For the pharmaceutical professional—the IP attorney, the competitive intelligence analyst, the R&D strategist—relying on a generalist tool for a specialist’s job is not a savvy shortcut; it is a strategic gamble with the company’s future. The effortless delivery of millions of documents masks the critical data that is missing, the dangerous lag in its updates, and its fundamental inability to perform the specialized searches essential for pharmaceutical and biologic innovation.

This report will deconstruct that illusion. We will embark on a deep dive into the 15 critical reasons why Google Patents is a high-risk, unsuitable, and ultimately inadequate tool for professional drug patent analysis. We will explore the structural deficiencies in its data, the crippling limitations of its search algorithms, and the gaping void where actionable intelligence ought to be. This is not an academic critique; it is a business-critical assessment of risk. By the end, it will be clear why turning to a free, generalist platform for answers that determine the fate of multi-billion-dollar drug programs is a strategic error that no modern biopharma company can afford to make.

Part I: The Foundation of Failure – Critical Flaws in Data Integrity and Coverage

Before any search query is typed, before any analysis is performed, the bedrock of any reliable intelligence platform is its data. The information must be comprehensive, accurate, and timely. Anything less is unacceptable when strategic decisions hang in the balance. It is in this fundamental requirement that Google Patents first reveals its most critical flaws. A strategy built upon the data within Google Patents is a strategy built on shifting sands, vulnerable to the hidden risks of jurisdictional gaps, dangerous data lags, and legally unreliable information. These are not minor inconveniences to be worked around; they are structural deficiencies that create a distorted and dangerously misleading picture of the patent landscape.

Reason 1: Jurisdictional Blind Spots and the Myth of “Global” Coverage

The modern pharmaceutical market is a global battlefield. A successful drug launch in the U.S. and Europe can be quickly undermined by a generic competitor emerging from India or a blocking patent filed in China. A truly global commercial strategy, therefore, demands a truly global intellectual property analysis. Google Patents, with its headline claim of indexing documents from over 100 patent offices, creates a powerful impression of comprehensive global coverage.1 This impression, however, is a mirage.

Digging into the fine print reveals a more complex and concerning reality. Google itself explicitly states that it “cannot guarantee complete coverage” of all documents from these offices.3 This is not a standard legal disclaimer; it is a frank admission of tangible gaps in the data that can have severe consequences. Multiple analyses and user reports confirm that crucial jurisdictions for the global pharmaceutical market—such as Japan, China, India, and Brazil—often have incomplete, partially indexed, or significantly delayed data.7 In some instances, only the abstract of a foreign patent is available, rendering a thorough analysis of its claims—the legally operative part of the patent—impossible.

The strategic implications of these jurisdictional blind spots are profound. Imagine a mid-sized biotech company preparing for a global launch. They conduct a Freedom to Operate (FTO) search on Google Patents and find no blocking patents. They confidently proceed, investing millions in manufacturing scale-up and marketing preparations for key emerging markets. What they don’t know is that a critical piece of prior art, a Chinese patent application that fully anticipates their invention, was never properly indexed by Google. As one case example illustrates, a pharmaceutical patent attorney completely missed a pivotal Chinese prior art document that was only available on a specialized platform. The biotech’s “clear” FTO was, in fact, a direct path to an infringement lawsuit and a complete blockade of their entry into one of the world’s largest healthcare markets.

This reveals a deeper, more subtle risk. The “100+ patent offices” figure is a vanity metric that masks a critical lack of depth. Business strategists can be lulled into a false sense of security, mistaking breadth for the depth and quality of coverage that actually matters. A professional platform like DrugPatentWatch builds its value not on the sheer number of jurisdictions covered, but on the quality, timeliness, and completeness of the data from the jurisdictions that are commercially vital to the pharmaceutical industry, often secured through direct data feeds from patent offices.10 The strategic error is focusing resources on markets where data is easily accessible (like the US and Europe) while inadvertently ignoring massive commercial risks in markets where Google’s data is sparse. This isn’t just incomplete data; it’s a distorted lens that can warp a company’s entire global strategy.

Reason 2: The Peril of Lag Time – When “Recent” Isn’t Recent Enough

In the hyper-competitive pharmaceutical sector, timing is everything. A few weeks’ head start can translate into a significant market advantage. Conversely, a few weeks of operating with outdated information can be catastrophic. This is the peril of lag time, and it is a structural flaw woven into the very fabric of Google Patents’ data acquisition model.

Multiple independent analyses and user reports confirm that the database is not updated in real-time. There is often a considerable lag, ranging from several weeks to even a couple of months, between the moment a patent document is officially published by a patent office and when it becomes discoverable on Google Patents.3 For example, a new patent application published by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) on a Thursday might not appear in Google’s index for weeks.

This delay creates a critical “window of vulnerability.” Consider the 18-month “blackout” period, where all patent applications are kept secret from their initial filing date until publication.3 No search tool can see into this period. The real risk begins the moment that secrecy lifts. A competitor’s application is published, revealing a new R&D direction or a potential threat to your pipeline. Professional databases with direct, paid data feeds from patent offices often ingest and index this new information within hours or days. A researcher using one of these platforms is aware of the new threat almost immediately.

A researcher relying on Google Patents, however, is flying blind. They are operating in a state of artificially extended uncertainty. They might conduct an FTO search for a planned clinical trial, find no issues, and authorize a multi-million-dollar milestone payment. Two weeks later, the competitor’s patent finally appears on Google Patents, revealing that the trial they just funded directly infringes on a newly published claim. The “free” tool has just cost them millions. This lag time fundamentally undermines the core purpose of competitive intelligence, which is to anticipate, not react. If your data source is weeks behind reality, you are perpetually reacting to old news, making decisions based on an outdated map of the competitive landscape.

Reason 3: Incomplete and Inaccurate Data Sets

Beyond jurisdictional gaps and update delays, the very integrity of the data that is present in Google Patents is questionable. The platform is plagued by issues of incompleteness and inaccuracy that can derail any serious analysis.7 These are not isolated glitches but systemic problems stemming from Google’s method of aggregating data from myriad sources with varying standards and formats.

Critical data points are often missing or flawed. This includes incomplete bibliographic metadata, such as incorrect assignee names or missing priority claims, which are essential for tracking a company’s portfolio or an invention’s history. More alarmingly, the platform struggles with accurately compiling patent families—the collection of related patents filed in different countries based on a single original invention. As one user on a patent law forum noted, a search for a large, well-known patent family yielded only two results on Google Patents, while the same search on The Lens, a more specialized non-profit tool, returned 31 distinct patent documents. This is not a minor discrepancy; it represents a fundamental failure to connect related intellectual property, leaving a user with a dangerously fragmented view of a competitor’s global protection strategy.

Furthermore, crucial procedural events that determine a patent’s strength and enforceability—such as post-grant oppositions, re-examinations, or appeals—are often missing or not updated in a timely manner. A company could invest significant resources designing around a competitor’s patent, completely unaware that the patent is simultaneously being challenged and is on the verge of being invalidated at the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB).

This creates what can be described as “data chasms”—gaps that break the essential chain of legal and commercial analysis. A complete patent assessment requires linking multiple, distinct types of information: the patent document itself, its up-to-the-minute legal status, its family members across the globe, its corresponding regulatory listings (like the FDA’s Orange Book), and any associated litigation.3 Google Patents provides, at best, a shaky and incomplete view of the first element in that chain. It lacks the reliable, curated links to the other critical datasets. This forces the user to attempt to manually and unreliably bridge these data chasms, a process that is not only monumentally inefficient but also dangerously prone to error. A professional platform, in contrast, is built on the principle of

integration. A service like DrugPatentWatch, for example, builds its core value by connecting patent data directly to FDA regulatory data, clinical trial information, and court litigation records, transforming a simple document lookup into a comprehensive intelligence-gathering exercise.11

Reason 4: Legal Status Roulette – Relying on Unreliable and Outdated Information

For a Freedom to Operate search, the legal status of a patent is not just a data point; it is the entire game. An FTO analysis is concerned only with active, in-force patents that pose a real threat of litigation.18 A patent that has expired, been abandoned by its owner through non-payment of maintenance fees, or been invalidated in court is legally irrelevant for an infringement analysis. It is precisely on this most critical of data points that Google Patents fails most spectacularly.

The platform is notorious for having outdated, inaccurate, or simply missing legal status information.7 A patent that expired six months ago might still be listed as “Active.” A patent that was successfully invalidated in an

inter partes review (IPR) might show no record of the proceeding. This is not a minor flaw; it renders the tool fundamentally unsuitable for any professional FTO or clearance search.

The consequences of relying on this “legal status roulette” are severe. A startup, in a now-classic cautionary tale, licensed a patent they found on Google Patents, only to discover later through a professional database that the patent had already lapsed due to non-payment of fees—they had licensed nothing. Conversely, a generic company might see a patent listed as “Abandoned” and proceed with a product launch, only to be hit with an infringement suit because the status was incorrect and the patent owner had successfully revived it. Millions of dollars in R&D, legal fees, and strategic planning can be wasted based on a single, incorrect data point.

This unreliability reveals a fundamental weakness in Google’s data model: it is a passive aggregator, not an active curator. Google’s systems crawl and index publicly available information from patent office websites. They do not appear to make the significant investment in technology and human expertise required to actively collate, verify, and normalize legal status data from dozens of disparate, often non-standardized, official registers around the world. Professional databases, in stark contrast, build their entire value proposition on this curation. They invest heavily to provide a single, reliable, and up-to-date legal status indicator, which is a core reason they command subscription fees.20

This issue extends to the highly complex and financially critical calculations of Patent Term Adjustment (PTA) and Patent Term Extension (PTE). PTA compensates for delays by the USPTO during prosecution, while PTE restores patent life lost during lengthy FDA regulatory reviews.22 For a blockbuster drug, a single day of patent term can be worth millions of dollars in revenue. These calculations are notoriously complex, involving overlapping delays and statutory caps.24 Google Patents often fails to display this information correctly, if at all, making it impossible to determine a drug’s true, commercially relevant expiration date. Relying on Google Patents for legal status information is, quite simply, a high-stakes gamble that no prudent business should be willing to take.

Part II: The Search That Misses – Why Generalist Algorithms Fail Specialized Science

Assuming for a moment that the data in Google Patents were perfect—complete, timely, and accurate—the platform would still be woefully inadequate for pharmaceutical research. A database is only as good as the tools you have to query it. It is here, in the realm of search capability, that we see a fundamental mismatch between Google’s generalist, text-based search paradigm and the specific, complex, and multimodal language of pharmaceutical and biological sciences. This section will demonstrate how Google’s algorithms, so powerful for searching the web, are simply the wrong tools for uncovering the scientific and legal nuances buried within drug patents.

Reason 5: The Semantic Trap – Keyword Limitations in Complex Pharma Terminology

At its heart, Google Patents is a keyword search engine. While it supports Boolean operators like AND, OR, and NOT, and some proximity operators like NEAR and ADJ, its implementation is often described as not robust enough for the complex queries required in patent law, with results that can be inconsistent and unpredictable.8 The core problem, however, is more profound than just the syntax of the search query. The very reliance on keywords is a semantic trap in the world of pharmaceutical patents.

Patents are, by their nature, written in a complex and often deliberately obtuse blend of technical and legal language, designed to maximize scope while meeting statutory requirements.27 This is amplified in the pharmaceutical field, where a single chemical compound can be referred to by a dizzying array of names. Take, for example, the active ingredient in Pfizer’s Paxlovid. A keyword search for “Paxlovid” would miss patents that refer to it only by its generic name, “nirmatrelvir.” Both of those searches would miss patents that refer to it only by its internal company project code, “PF-07321332.” And all of those would miss patents that refer to it only by its formal IUPAC chemical name or, even more broadly, as part of a claimed chemical class.

Relying on keywords forces the searcher into a constant, and likely losing, guessing game about which specific terms the patent drafter chose to use. This inevitably leads to two poor outcomes: “false negatives,” where critical patents are missed because they used a different term, and “false positives,” where the searcher is swamped with thousands of irrelevant “junk” results that happen to contain a keyword out of context.

This failure points to a deeper issue: the need for an ontological, rather than a purely lexical, approach to searching. A lexical search, like Google’s, matches strings of characters. An ontological search understands the concepts behind the words and the relationships between them. A true pharmaceutical patent database has a built-in ontology; it knows that “Januvia,” “sitagliptin,” and its complex IUPAC name all refer to the exact same active pharmaceutical ingredient. It connects these terms automatically, so a search for one finds them all. Google’s algorithm lacks this deep, domain-specific knowledge. Consequently, the immense burden of building this complex network of synonyms, codes, and chemical names falls upon the user—a task that is virtually impossible to perform comprehensively. This is not just a limitation; it is a recipe for search failure.

Reason 6 & 7: The Unsearchable Core – No Chemical Structure or Biologic Sequence Searching

If the reliance on keywords is a trap, the complete absence of chemical structure and biologic sequence searching is a fatal flaw. This is arguably the single greatest technical failure of Google Patents for pharmaceutical and biotechnology research, rendering it incapable of searching for the very essence of the invention in a vast and growing proportion of life science patents.7

For small-molecule drugs, especially new chemical entities (NCEs), the core invention is the molecule’s structure. Patent attorneys often use a claiming strategy known as a “Markush structure” to protect not just one specific molecule, but an entire family of related compounds within a single, generic chemical formula.10 These claims define variables (e.g., R1, R2, X) that can represent dozens or even hundreds of different chemical groups. A text-based keyword search is, as one expert noted, “utterly useless” against such claims because it cannot interpret the drawing or the chemical formula. The only way to determine if your specific molecule is covered by a competitor’s Markush claim is with a dedicated chemical substructure search engine, a feature Google Patents completely lacks. A company could develop a novel molecule, run exhaustive keyword searches on Google, find nothing, and proceed with development, all while their molecule is explicitly claimed—and blocked—by a competitor’s patent.

The situation is even more critical for biologics—the monoclonal antibodies, cell and gene therapies, and therapeutic proteins that dominate modern drug development.30 For these complex molecules, the invention

is the sequence of amino acids (for proteins) or nucleotides (for DNA/RNA). A keyword search for “an antibody that binds to PD-L1” is hopelessly broad and insufficient. A proper FTO or patentability search requires the ability to search for specific biologic sequences, such as the six complementary-determining regions (CDRs) that define a monoclonal antibody’s unique binding site.32 Without this capability, it is impossible to know if your therapeutic antibody is novel or if it infringes on a competitor’s sequence claims.

This absence represents a fundamental disconnect between Google’s technological architecture and the core needs of the life sciences industry. Google’s core competency is indexing and searching the text and images of the public web. Building, curating, and maintaining searchable databases of millions of chemical structures and biological sequences is a completely different technological paradigm. It requires deep, specialized scientific expertise in fields like cheminformatics and bioinformatics. Companies like CAS (for chemistry) and specialized platform providers like Questel have built their entire businesses around this specific, complex capability.20 Google’s failure to offer these essential search modes demonstrates that it is a generalist tool that has been

extended to cover patents, not a specialist tool built for pharmaceutical patents from the ground up. For any serious researcher in this field, this distinction makes all the difference.

Reason 8: The Unreliability of Machine Translations

In a globalized pharmaceutical market, the ability to understand patents filed in any language is critical. Google Patents offers on-the-fly machine translation, a feature that seems to solve this problem with a single click. However, for the precise and high-stakes world of patent law, this convenience is a double-edged sword. Relying on these automated translations for anything more than a cursory overview is a significant strategic risk.7

Patent documents are not ordinary technical manuals; they are legal instruments where every single word carries immense weight. The scope of a patent’s protection is defined by its claims, and the language of those claims is meticulously crafted and interpreted according to decades of case law. Simple-sounding words can have very specific legal meanings. For example, the transitional phrase connecting the preamble of a claim to its body—words like “comprising,” “consisting of,” or “consisting essentially of”—has a profound and legally defined impact on the claim’s scope.16 “Comprising” is open-ended, meaning the invention can include other unlisted elements. “Consisting of” is closed and absolute. A machine translation algorithm, trained on general language corpuses, cannot grasp these critical, context-specific legal nuances. It might translate two legally distinct phrases into the same word, completely altering the perceived scope of the patent.

Misinterpretations due to these translation errors can lead directly to misinformed decisions and missed opportunities. An analyst might read a poor machine translation of a Japanese patent’s claims and conclude it is narrow and not a threat, when in fact the original language defined a broad scope of protection that blocks their company’s product. Relying on a machine translation for a formal FTO opinion would be considered professional malpractice.

This creates a subtle but pervasive risk: the promotion of a “good enough” culture. A researcher gets a rough, translated gist of a foreign patent, decides it’s “probably not relevant,” and moves on, without ever realizing that a critical limitation or a key piece of enabling disclosure was lost in translation. The easy availability of a flawed solution (machine translation) discourages the use of the difficult but correct solution (engaging professional human translators or native-language searchers for critical documents), thereby directly increasing the company’s strategic risk.

Reason 9: Inadequate Prior Art Coverage

A comprehensive prior art search is the cornerstone of the entire patent system. It is the process by which an inventor, and later a patent examiner, determines if an invention is truly novel and non-obvious and therefore deserving of a patent.7 A company that files a patent application without a thorough prior art search is flying blind, risking millions in legal and R&D costs on an invention that may not be patentable. An FTO search that misses key prior art can lead to a product launch that infringes a competitor’s patent. On all fronts, comprehensive prior art coverage is non-negotiable.

Google Patents’ prior art coverage is fundamentally inadequate, crippled by the very limitations we have already discussed: its incomplete database scope and its flawed search capabilities. But the problem runs deeper. A critical, and often misunderstood, aspect of patent law is that “prior art” is not limited to other patents. It encompasses any information made publicly available before the invention’s filing date. This includes a vast universe of non-patent literature (NPL): scientific journal articles, academic dissertations, conference presentations, technical standards, product manuals, and websites.1

While Google Patents commendably integrates results from Google Scholar, providing some access to academic papers, this integration is not as comprehensive or systematically curated as that found in professional databases.1 Specialized platforms like those from Clarivate or CAS invest heavily in licensing and indexing a wide array of NPL sources specifically chosen for their relevance to patent examiners and IP professionals.21 They understand that the “killer” prior art that invalidates a multi-billion-dollar drug patent is just as likely to be found in a 1998 biochemistry PhD thesis as it is in another patent.

Furthermore, a generalist tool like Google cannot grasp the nuanced legal doctrines that define what constitutes “prior art.” For example, the doctrine of “inherent anticipation” states that a prior art reference can invalidate a patent even if it doesn’t explicitly mention every feature of the invention, as long as those features are an inherent or necessary result of what is described. A search tool that can only match keywords cannot make these subtle but legally dispositive connections. It can find documents, but it cannot assess their legal weight or strategic importance as prior art. An incomplete prior art search is not just an inconvenience; it can lead to the grant of a weak, “junk” patent that is easily invalidated later, or worse, a decision to abandon a truly innovative idea based on a flawed understanding of the existing landscape.

Part III: From Data to Dead Ends – The Absence of Actionable Intelligence

Even if Google Patents provided flawless data and perfect search tools, it would still fall short of the needs of a modern pharmaceutical enterprise. In today’s data-driven world, raw information is a commodity. The real value lies in the ability to analyze, visualize, and contextualize that information to generate actionable intelligence. This is the realm of analytics, and it is a realm where Google Patents is conspicuously absent. Using the platform is like being handed a 1,000-page phone book with no index, no map, and no way to identify the most important numbers. It provides a list of results, but it offers no pathway from that data to a strategic decision.

Reason 10: No Proprietary Analysis or Visualization Tools

A typical patent search in a competitive therapeutic area can yield thousands, if not tens of thousands, of relevant documents. A simple, linear list of these results is functionally useless for understanding the bigger picture. To make sense of such a large dataset, you need analytical and visualization tools. Specialized patent databases are built around this principle, offering a suite of proprietary tools to visualize patent landscapes, track competitor activity, and identify technology trends.4 Google Patents provides none of these capabilities.7

Patent landscaping is a critical strategic exercise for any R&D-intensive organization. It involves creating a visual map of the intellectual property in a given field to answer crucial business questions.13 Professional platforms like PatSnap, Orbit Intelligence, or XLSCOUT use sophisticated algorithms to generate interactive heatmaps, 3D cluster diagrams, and trend charts that can reveal, at a glance:

- Who the key players are: Which companies hold the most patents in a specific technology?

- Where R&D is concentrated: Are all the patents clustered around a single biological target, or are multiple approaches being explored?

- Technology evolution over time: How has patenting activity in this area changed over the last decade?

- “White space” opportunities: Where are the gaps in the landscape—the unexplored areas with little patenting activity that might represent a prime opportunity for innovation? 42

Without these tools, the Google Patents user is lost in a sea of data. They are forced to resort to manual, time-consuming, and inefficient methods like downloading results into spreadsheets for painstaking analysis. This is not only a massive drain on productivity but also leads to inferior insights. The human eye cannot detect the subtle patterns and connections within a dataset of 10,000 patents that a machine learning algorithm can visualize in seconds.

This lack of analytical power relegates patent searching to a purely defensive, administrative task (“Did we find any blocking patents?”) rather than the proactive, strategic function it should be (“Where is the industry going, and how do we get there first?”).16 Google Patents, by its design, traps the user in this defensive mindset, preventing them from leveraging patent data as a strategic GPS for innovation and growth.42

Reason 11: Absence of Comprehensive Citation Analysis

Patents do not exist in a vacuum. They form a dense, interconnected web of knowledge, with each new invention building upon those that came before it. This web is mapped through citations. Just as in academic literature, patent citations are a powerful indicator of influence and importance. Analyzing these citation networks is a cornerstone of sophisticated IP intelligence, and it is another area where Google Patents’ capabilities are severely limited.

There are two types of citations:

- Backward Citations: These are the prior art documents (both patents and NPL) that a patent application cites as the foundation upon which it is built. Analyzing these reveals the technological lineage of an invention.

- Forward Citations: These are the subsequent patents that cite the patent in question. The number of forward citations a patent receives is widely regarded as a strong proxy for its technological and commercial impact. A patent that is cited hundreds of times by later innovators is clearly a foundational piece of technology.

While Google Patents provides basic hyperlinks to cited and citing documents, it lacks the robust analytical tools needed to make sense of these networks. It cannot, for example, generate a visualization of a citation tree, identify the most influential patents in a search result based on citation frequency, or track the citation velocity (the rate at which a new patent is being cited). Furthermore, its arbitrary display limitation of 300 results per query can make a comprehensive analysis of a heavily cited patent impossible.

This flaw has direct financial consequences, particularly in the context of mergers, acquisitions, and investment due diligence. When evaluating a potential acquisition target, the quality of its patent portfolio is a key driver of its valuation. A simple count of patents is a meaningless metric. A company could have 100 patents that have never been cited and are essentially worthless. Another company might have only five patents, but if those five are foundational and have been cited thousands of times, they represent an immensely valuable strategic asset. An investor or M&A team relying on Google Patents would have no reliable way to perform this crucial valuation analysis. They could grossly overvalue a company with a portfolio of trivial patents or, conversely, completely miss the hidden value in a company with a small but powerful portfolio, leading to flawed investment decisions.

Reason 12: No Alerts or Monitoring Features

The intellectual property landscape is not a static photograph; it is a constantly evolving motion picture. New patent applications are published every week, the legal status of existing patents changes daily, and competitors are constantly shifting their strategies. To stay competitive, a company cannot rely on periodic, manual searches. It needs a dynamic, automated monitoring system. This is a standard feature in any professional IP intelligence platform, and it is completely absent from Google Patents.

Professional databases allow users to set up automated alerts for virtually any parameter of interest.20 An R&D manager can set an alert to be notified every time a key competitor files a new patent application in their technology space. A patent attorney can set an alert to monitor a specific, high-risk patent, receiving an immediate notification if its legal status changes—for example, if it is granted, abandoned, or challenged in court. This transforms competitive intelligence from a reactive, labor-intensive task into a proactive, automated workflow.

The lack of this single feature forces a company using Google Patents into a perpetually reactive posture. They are the ship sailing without radar, only able to react to obstacles after they have appeared directly in front of them. By the time they manually run their quarterly search and discover that their main rival filed a groundbreaking patent application two months ago, it is already old news. The competitor has had a two-month head start in executing the strategy that the patent filing signaled. A company with automated monitoring, however, sees the threat appear on the horizon the day it is published. They have time to analyze the competitor’s move, adjust their own R&D strategy, begin searching for invalidating prior art, or even consider a licensing approach. The absence of alerts and monitoring is not just an inconvenience; it fundamentally changes a company’s ability to navigate its competitive environment, forcing it to absorb strategic shocks rather than anticipate and mitigate them.

Reason 13: Limited Integration with Other Essential Research Tools

A patent is a legal document, but its value is derived from its connection to a commercial product. In the pharmaceutical industry, this connection is explicit and governed by a complex regulatory framework. To understand the true commercial landscape of a drug, one cannot look at patent data in isolation. It must be integrated with regulatory data, litigation records, and clinical trial information. This integration is the hallmark of a true pharmaceutical intelligence platform, and it is a capability that Google Patents entirely lacks.3

The most critical data integration for any drug patent search is with the FDA’s official publications: the “Orange Book” (for small-molecule drugs) and the “Purple Book” (for biologics).11 When an innovator company receives FDA approval for a new drug, it is required to list the patents that cover that drug in these publications. The Orange and Purple Books also list various types of FDA-granted regulatory exclusivities (e.g., New Chemical Entity, Orphan Drug) that provide market protection independent of patents.

A drug’s true Loss of Exclusivity (LOE) date—the date when generic or biosimilar competition can actually begin—is determined by the later of its patent expiry and its regulatory exclusivity expiry. Because Google Patents is not integrated with the Orange and Purple Books, a user is forced to manually shuttle between the two disconnected systems. They might find a patent’s expiration date on Google but be completely unaware of a seven-year Orphan Drug Exclusivity listed in the Orange Book that extends the drug’s market monopoly for years beyond the patent’s life. This manual cross-referencing is not only inefficient but dangerously prone to error, leading to a fundamentally flawed understanding of a product’s commercial lifecycle.

This lack of integration creates a “siloed” view of intellectual property, divorcing the legal asset (the patent) from its real-world commercial context (the drug). This is where a specialized platform like DrugPatentWatch demonstrates its immense value. Its entire architecture is built on the principle of integration.11 It doesn’t just provide a list of patents; it provides a holistic view of a drug, linking its patents to its FDA approval status, its regulatory exclusivities, its clinical trial history, its litigation records, and even its sales data.12 This allows a user to ask complex, business-critical questions that are simply unanswerable with a tool like Google Patents. For example: “Show me all patents protecting blockbuster biologics that are currently involved in BPCIA litigation and are expected to face biosimilar competition in the next two years.” Answering this requires an integrated database. The lack of integration makes Google Patents a tool for looking up isolated documents, not a platform for generating strategic business intelligence.

Reason 14: User Interface Limitations and Lack of Customization

Ironically, one of Google Patents’ most praised features—its simple, user-friendly interface—is also a significant limitation for professional use.3 While its clean, familiar design lowers the barrier to entry for casual users, it comes at the cost of the power, customization, and collaborative features that are essential for enterprise-level IP management.

Professional patent analysis is rarely a solo activity. It is a complex, iterative, and collaborative process that involves teams of R&D scientists, in-house and outside patent counsel, and business development strategists. An effective workflow requires tools to support this collaboration. Professional platforms are designed with this in mind, offering features such as:

- Project-based organization: The ability to create dedicated workspaces or folders to save, organize, and annotate patents related to a specific project (e.g., “Project X FTO,” “Competitor Y Portfolio”).4

- Advanced sharing and collaboration: Tools that allow teams to share curated lists of patents, add comments, and track review status within the platform, creating a centralized and auditable record of the analysis.54

- Customizable views and exports: The ability to tailor the display of search results and export data in flexible formats (e.g., Excel) for further analysis or reporting.

Google Patents lacks nearly all of these enterprise-grade workflow features. There is no robust way to save and organize work into projects, no integrated system for team collaboration, and limited customization options.4 A user cannot even perform a simple function like highlighting multiple keywords simultaneously in a document. This forces professional teams to fall back on inefficient and disconnected methods like managing massive spreadsheets, sharing links over email, and trying to consolidate feedback from scattered documents—a process that is a recipe for duplicated effort, version control nightmares, and the loss of valuable institutional knowledge.

This reveals a fundamental difference in design philosophy. Google Patents has a consumer-grade, “one-size-fits-all” UI, optimized for individual, ephemeral lookups. Professional IP platforms have an enterprise-grade UI, optimized for the project-based, collaborative, and long-term nature of corporate IP management. This design choice makes Google Patents fundamentally misaligned with the way serious IP analysis is actually conducted in a business environment.

Reason 15: Privacy and Confidentiality Concerns

In the fiercely competitive pharmaceutical industry, information is power, and confidentiality is paramount. A company’s R&D strategy, its next blockbuster target, and its assessments of competitors’ weaknesses are among its most valuable trade secrets. The use of free, public-facing online tools for sensitive research inevitably raises significant privacy and confidentiality concerns.

When a researcher at a major pharmaceutical company types a query into Google Patents—for example, searching for a novel chemical structure combined with a specific biological target—they are revealing a piece of their company’s confidential R&D strategy. While Google has a privacy policy, the fundamental business model of a free, data-driven company is different from that of a paid, enterprise software provider. There is an inherent risk that search query data could be logged, aggregated, analyzed, or even inadvertently exposed.

Beyond the risk of data logging, some legal experts have raised the concern that entering the details of a new, unpatented invention into a public search engine could, under certain circumstances, be argued to constitute a form of “public disclosure”.57 Such a disclosure, if proven, could destroy the novelty of the invention and render it unpatentable worldwide. This risk is amplified when researchers use third-party AI tools in conjunction with their searches, as some of these tools may incorporate user inputs into their training data, potentially broadcasting trade secrets to the world.

While the precise legal risk may be debatable, for a pharmaceutical company managing a multi-billion-dollar pipeline, even a small, non-zero risk of a confidentiality breach is often unacceptable. Professional, subscription-based platforms make data security and client confidentiality a core part of their value proposition. Their business model depends on being a trusted, secure vault for their clients’ most sensitive information. This is a guarantee that a free, public platform simply cannot and does not offer. The old adage, “if you’re not paying for the product, you are the product,” is a stark reminder of the strategic calculation a company must make. The “cost” of the free tool may well be the confidentiality of the very innovations that drive the company’s future.

Part IV: The Professional Imperative – From Basic Search to Strategic Intelligence

Having systematically deconstructed the 15 critical failures of Google Patents, it is clear that relying on this generalist tool for professional pharmaceutical IP analysis is not a viable strategy. The cascade of failures—from unreliable data and incomplete coverage to crippled search functions and a complete lack of analytical power—makes it a source of unacceptable risk.

So, what is the alternative? The answer lies in shifting from a mindset of basic, free searching to one of investing in true, professional-grade IP intelligence. This section will build the positive case for specialized platforms, moving beyond a simple list of features to explain how these tools enable essential business workflows that are simply impossible with Google Patents. This is what “good” looks like, and why it is a necessary investment for any serious player in the biopharmaceutical industry.

The Specialist’s Toolkit: The Power of Curated, Integrated, and Actionable Data

The deficiencies of Google Patents are not random bugs; they are the predictable outcome of a generalist approach applied to a specialist’s domain. Professional platforms, in contrast, are purpose-built to solve the specific, high-stakes problems of the pharmaceutical industry. Their power derives from a combination of curated data, specialized search, integrated intelligence, and advanced analytics.

A platform like DrugPatentWatch is not merely an aggregator of patent documents; it is a sophisticated intelligence engine. Its core value is built on several key pillars that directly address the failings of Google Patents:

- Curated & Verified Data: Instead of passively crawling public websites, professional platforms invest in direct data feeds from major patent offices, and employ teams of experts to clean, normalize, and verify the information. This ensures the data, particularly critical legal status and patent term information, is timely and reliable.10

- Specialized Search Capabilities: They are built from the ground up with the necessary tools for life sciences, including integrated chemical structure and biologic sequence search engines that can handle the complexities of Markush claims and therapeutic proteins.16

- Integrated Intelligence: This is perhaps the most crucial differentiator. They do not treat patent data as a silo. They seamlessly link patent information with other critical datasets, including FDA regulatory data from the Orange and Purple Books, court litigation records from PTAB and District Courts, and clinical trial information from registries like ClinicalTrials.gov.11

- Advanced Analytics & Visualization: They provide the tools to move beyond a simple list of results, enabling users to create patent landscapes, perform trend analysis, and generate visual reports that turn complex data into clear, strategic insights.12

- Workflow & Collaboration Tools: They are designed for enterprise use, with features for monitoring, alerting, saving, and sharing work across teams in a secure, project-based environment.20

The following table provides a direct, feature-by-feature comparison that crystallizes the chasm between a generalist tool and a professional platform.

Table 1: Feature-by-Feature Comparison: Google Patents vs. Professional Pharmaceutical IP Platforms (e.g., DrugPatentWatch)

| Feature | Google Patents | Professional Platform (e.g., DrugPatentWatch) | Strategic Implication of the Gap |

| Data Coverage | Incomplete/unverified coverage in key pharma markets (e.g., China, India, Brazil) 7 | Curated, full-text coverage focused on commercially relevant jurisdictions | False sense of global clearance; high risk of missing blocking patents in key markets. |

| Data Timeliness | Lags of weeks to months behind official publication | Updates within hours or days via direct data feeds | Critical “window of vulnerability” where decisions are made on outdated information. |

| Legal Status Accuracy | Unreliable, often outdated or incorrect (Active, Expired, PTA/PTE) 7 | Actively curated, verified, and updated legal status, including complex term calculations 20 | Wasted resources designing around expired patents or infringing active ones; catastrophic for FTO. |

| Chemical Structure Search | None | Fully integrated exact, substructure, and Markush search engines 18 | Inability to conduct FTO/validity searches for most new chemical entities, leading to high infringement risk. |

| Biologic Sequence Search | None | Integrated sequence search (e.g., BLAST, Motif) for proteins and nucleotides 33 | Impossible to assess novelty or freedom to operate for biologics like monoclonal antibodies. |

| Regulatory Integration | None 3 | Seamless integration with FDA Orange Book and Purple Book data 11 | Inability to determine true Loss of Exclusivity (LOE); siloed view of patents divorced from their commercial product. |

| Litigation Integration | Limited to a “litigation” filter; no structured data | Integrated, searchable databases of PTAB (IPR/PGR) and District Court litigation 11 | Blindness to ongoing patent challenges that could invalidate a key patent or signal early generic entry. |

| Analytical/Visualization Tools | None 7 | Suite of tools for patent landscaping, heatmaps, trend analysis, and competitive charting 13 | Inability to see the “big picture,” identify trends, or find “white space” opportunities; data without intelligence. |

| Monitoring & Alerts | None | Automated, customizable alerts for competitors, technologies, or specific patents 20 | Perpetually reactive posture; inability to anticipate competitive moves in real-time. |

| Collaboration/Workflow | Minimal; no project folders or team features 4 | Secure, project-based workspaces for saving, annotating, and sharing results across teams 54 | Inefficient, disconnected workflows using spreadsheets and email; loss of institutional knowledge. |

| Data Curation | Automated aggregation of public data | Human-expert and AI-powered cleaning, normalization, and enhancement of data 20 | “Garbage in, garbage out”; search results are noisy and analysis is based on potentially flawed data. |

| Support & Expertise | General feedback form | Access to subject matter experts, patent analysts, and dedicated support teams 20 | Users are left to interpret complex data on their own; no expert guidance available. |

Essential Workflow 1: The High-Stakes Freedom to Operate (FTO) Search

Perhaps no task in pharmaceutical IP management is more critical or carries more risk than the Freedom to Operate (FTO) analysis. An FTO search is the formal, rigorous process of determining whether a planned commercial product or process can be launched in a specific country without infringing the active, in-force patent rights of a third party.18 It is a proactive due diligence exercise designed to mitigate the risk of a crippling infringement lawsuit.18 It is crucial to understand that an FTO search is

not a patentability search. Patentability asks, “Can I get a patent on my invention?” FTO asks, “Can I sell my product without being sued?”.18 You can have a valid patent on an improvement to a technology but still infringe a broader, underlying patent covering the core technology itself.

Given the stakes, conducting an FTO search on Google Patents is not just ill-advised; it is strategically reckless. Every limitation discussed in Part I and II—the jurisdictional gaps, the data lags, the unreliable legal status, and the complete lack of structure and sequence search—makes the platform dangerously inadequate for this task. A formal FTO opinion, which can be used in court to defend against allegations of “willful infringement” and the threat of triple damages, must be based on a search that is thorough and competent.18 An opinion based on a Google Patents search would likely be considered worthless by a court.

A professional FTO workflow, enabled by a specialized platform, looks entirely different. The process begins by precisely defining the product and the key jurisdictions for launch.18 The searcher then uses the platform’s advanced tools to:

- Filter the search to include only active, in-force patents and published applications within the relevant jurisdictions.

- Conduct keyword searches using a comprehensive, iteratively refined strategy.

- Critically, conduct parallel searches using the chemical structure and/or biologic sequence of the drug product, ensuring that non-obvious threats like Markush claims are identified.

- Analyze the claims of the resulting patents to determine if they “read on” the proposed product.

- If a blocking patent is found, use the platform’s integrated litigation data and citation analysis tools to assess its strength and history of enforcement.

The cost of getting this wrong is astronomical. The median cost of patent litigation through trial and appeal can be as high as $5.5 million.68 Major infringement verdicts can run into the billions, as seen in the $2.5 billion judgment Merck won against Gilead. When viewed against this backdrop, the subscription fee for a professional database is not an expense; it is a minuscule insurance premium against a catastrophic financial and commercial risk.

Essential Workflow 2: Strategic Patent Landscaping and Competitive Intelligence

While FTO is a defensive necessity, patent landscaping is an offensive strategic weapon. It is the process of creating a comprehensive, visual map of the entire IP landscape for a given technology area to identify trends, understand the competitive environment, and uncover opportunities for innovation.13

As established, Google Patents is completely incapable of performing this function due to its lack of any analytical or visualization tools.7 It allows you to see individual trees, but it can never show you the forest.

A professional platform with advanced analytics enables a fundamentally different level of strategic inquiry. By transforming raw patent data into interactive charts and maps, an analyst can quickly answer critical business questions:

- Competitor Strategy: Which companies are the most active filers in the field of KRAS inhibitors? Where are they filing geographically? How has their strategy evolved over the last five years? This allows you to benchmark your own efforts and anticipate their next moves.42

- Technology Trends: Is research in this area moving towards combination therapies or novel delivery mechanisms? Visualizing patent classifications over time can reveal the trajectory of innovation.43

- White Space Analysis: The landscape map can reveal “white spaces”—areas with low patenting activity. Is there an underexplored biological pathway or a patient population with unmet needs that represents a prime opportunity for your company to be first-to-market?.42

- M&A and Licensing Opportunities: The landscape can identify smaller companies or academic institutions with valuable, highly-cited patents, flagging them as potential partners for licensing or targets for acquisition.

The DrugPatentWatch advantage becomes particularly clear in this context. By integrating patent landscape data with clinical trial and commercial data, it provides a uniquely powerful, multi-dimensional view of the competitive environment. An analyst can not only see what a competitor is patenting, but also what they are actively developing in clinical trials and what they are successfully selling on the market.12 This allows for a much more sophisticated and accurate assessment of a competitor’s true strategy and capabilities, transforming patent data from a historical record into a predictive intelligence tool.

“Patent landscape analysis provides a basis for understanding innovation activity, including which organizations are working in the area, what technologies and industries are being targeted, how technical problems are being solved, and how long it takes for innovations to reach the market.”

— IP Checkups

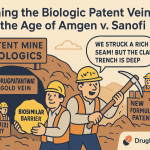

Case Study: Navigating the Biologics Frontier and the “Patent Dance”

Nowhere are the limitations of Google Patents and the necessity of professional tools more apparent than in the field of biologics. Biologic drugs are fundamentally more complex than traditional small-molecule drugs. They are large, heterogeneous molecules produced in living systems, and their manufacturing process is inextricably linked to the final product.30 This complexity gives rise to unique IP challenges.

Innovator companies protect their blockbuster biologics not with a single patent, but with a dense “patent thicket”—a web of dozens or even hundreds of overlapping patents covering the core molecule, specific formulations, manufacturing processes, methods of use, and delivery devices.71 For example, the world’s top-selling drug, Humira, is protected by a thicket of over 100 patents, which has successfully delayed biosimilar competition for years.

Navigating this thicket is governed by the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA), which established a complex patent dispute resolution framework colloquially known as the “patent dance”.74 This is a highly structured, multi-step process of information exchange and phased litigation between the biosimilar applicant and the innovator company.74

Attempting to navigate this landscape using Google Patents is an exercise in futility.

- It lacks the essential biologic sequence search needed to analyze the core patents.

- Its inability to reliably handle large patent families makes it impossible to map the full extent of a patent thicket.

- It has no integration with the FDA’s Purple Book, which lists the reference products and their exclusivities.

- It has no structured BPCIA litigation data, making it impossible to track the outcomes of the patent dance for other biosimilars.78

A biosimilar company needs a specialized platform to even begin to formulate a strategy. They need to map the entire patent thicket, analyze the claims of each patent, search for prior art to invalidate the weaker secondary patents (e.g., those on formulations or methods of use), and track ongoing BPCIA litigation to see which patents have been successfully challenged by others. An innovator company needs these same tools to manage its portfolio, monitor for biosimilar challengers, and prepare for the patent dance. For any company operating in the biologics or biosimilars space, investing in a professional, integrated intelligence platform is not optional; it is the absolute price of admission.

Conclusion: Beyond the Search Bar – Investing in True IP Intelligence

The evidence is overwhelming and the conclusion is unequivocal. While Google Patents stands as a remarkable feat of engineering for democratizing basic access to patent information, it is fundamentally the wrong tool for the specialized, high-stakes needs of the pharmaceutical industry. The 15 reasons detailed in this report are not a list of minor flaws or inconveniences; they represent a cascade of failures across the three pillars of any serious intelligence platform: data integrity, search capability, and strategic analysis.

The data is unreliable, with jurisdictional blind spots, dangerous time lags, and inaccurate legal statuses that make it a minefield for critical decisions. The search capabilities are crippled by a generalist, keyword-based algorithm that cannot handle the complex language of chemistry and biology, and completely lacks the essential tools of structure and sequence searching. Finally, the platform is an analytical void, offering no tools to visualize landscapes, analyze trends, or integrate patent data with the regulatory and commercial context that gives it meaning.

Ultimately, the choice of a patent search tool is not an IT procurement decision or a line-item expense to be minimized. It is a core strategic business decision that reflects a company’s entire approach to innovation and risk management. To rely on a free, generalist tool is to implicitly accept a reactive, high-risk IP strategy, where decisions are based on incomplete, outdated, and decontextualized information.

To invest in a professional, specialized platform like DrugPatentWatch is to commit to a proactive, intelligence-driven strategy. It is an investment in risk mitigation, in competitive advantage, and in the transformation of patent data from a legal hurdle into a powerful strategic weapon. In an industry where the difference between success and failure is measured in billions of dollars and years of research, the question for business leaders is not “Can we afford a professional tool?” but rather, “Can we possibly afford the consequences of not having one?”

Key Takeaways

- Data Integrity is Non-Negotiable: Google Patents suffers from critical flaws in data integrity, including incomplete global coverage, significant update delays, and unreliable legal status information, making it unsuitable for high-stakes decisions like FTO searches.

- Generalist Search Fails Specialized Science: The platform’s keyword-based search algorithm and its complete lack of chemical structure and biologic sequence searching make it incapable of finding the most relevant and critical drug patents.

- Analytics Separate Data from Intelligence: Google Patents provides a list of documents but lacks the analytical and visualization tools necessary to perform patent landscaping, identify trends, or generate actionable competitive intelligence.

- Integration is Essential for Context: A patent’s value is tied to its commercial product. The failure to integrate patent data with regulatory information (FDA Orange/Purple Books), litigation records, and clinical trial data leaves users with a siloed and incomplete picture.

- The Right Tool is a Strategic Investment: Relying on a free tool for pharmaceutical IP analysis is a high-risk gamble. Investing in a professional, integrated platform like DrugPatentWatch is a strategic imperative for managing risk, driving innovation, and securing a competitive advantage.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. Is it ever appropriate to use Google Patents in a professional pharmaceutical setting?

Yes, but with extreme caution and for very limited purposes. Google Patents can be a useful tool for a quick, preliminary lookup if you already have a specific patent number and want to view the document text or its basic, non-time-sensitive bibliographic data.57 It can also serve as a starting point for brainstorming or getting a very rough, high-level sense of a technology field. However, it should

never be used as the sole or primary tool for any formal, decision-driving analysis, such as a patentability search, a Freedom to Operate (FTO) clearance, an invalidity analysis, or competitive landscaping. Any findings from Google Patents must be independently verified using a professional, curated database and official patent office records.10

2. How does the “patent thicket” strategy for biologics make tools like Google Patents particularly ineffective?

A “patent thicket” is a dense web of dozens or even hundreds of overlapping patents protecting a single biologic drug, covering not just the molecule but also formulations, manufacturing methods, dosages, and delivery devices.31 This strategy creates several challenges that overwhelm Google Patents. First, the sheer volume of patents is difficult to manage and analyze without specialized portfolio analysis tools. Second, many of these patents involve biologic sequences or complex manufacturing processes that are poorly suited to keyword searching. Third, understanding the thicket requires mapping the complex relationships and dependencies between family members and related patents, a task for which Google’s family data is unreliable. A professional platform is needed to visualize the entire thicket, identify the key blocking patents, and assess the strength of each component.

3. What is the single biggest risk of relying on Google Patents for an FTO search?

The single biggest risk is a “false negative” FTO—that is, concluding you have freedom to operate when you actually infringe a valid, in-force patent. This risk stems from a combination of Google’s critical flaws: a blocking patent could be missed because it was in a jurisdiction with poor coverage (e.g., China) , because it was recently published and not yet indexed due to data lag , because it used a Markush structure that keyword search could not find , or because its legal status was incorrectly listed as expired. A false negative FTO can lead to a company investing hundreds of millions of dollars to launch a product, only to be hit with an injunction and a multi-million dollar infringement lawsuit, potentially destroying the product’s commercial viability.

4. Can’t I just compensate for Google’s limitations by being a more skilled searcher and cross-referencing with other free sites like the USPTO’s?

While a skilled searcher can certainly achieve better results than a novice, and cross-referencing is always good practice, this approach cannot fully compensate for the platform’s structural deficiencies. You cannot find data that simply isn’t in the database (jurisdictional gaps). You cannot overcome the data lag. You cannot perform a structure search where no such tool exists. Furthermore, manually cross-referencing across multiple, non-integrated government websites (e.g., USPTO Public PAIR, Espacenet, FDA Orange Book) is incredibly time-consuming, inefficient, and prone to human error.4 Professional platforms add value precisely by automating this integration, cleaning the data, and providing specialized search tools, saving hundreds of hours and reducing the risk of critical errors.

5. How does the lack of integration with FDA regulatory data (like the Orange Book) specifically impact a generic drug company’s strategy?

For a generic drug company, the FDA Orange Book is the roadmap for market entry. It tells them which patents the innovator claims protect a branded drug and when those patents and any regulatory exclusivities expire. A generic company’s entire business model revolves around challenging these patents or designing around them to launch on the earliest possible date. The lack of integration in Google Patents means a generic strategist cannot see the full picture. They might analyze a patent on Google and devise a legal strategy, but without the integrated Orange Book context, they won’t know if that patent is even listed against the drug, what its “patent use code” is, or if there are other, more formidable regulatory exclusivities (like a 7-year orphan drug exclusivity) that make challenging that specific patent a moot point. This forces them to work with two disconnected datasets, increasing the risk of a flawed strategic calculation that could cost millions in wasted legal fees and development effort.

References

- Coverage – Google Help, accessed August 4, 2025, https://support.google.com/faqs/answer/7049585?hl=en

- How to Use Google Patents for Effective Patent Searches, accessed August 4, 2025, https://patentpc.com/blog/how-to-use-google-patents-for-effective-patent-searches

- Google Patents: Why It’s a Risky Tool for Finding Drug Patents – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/google-patents-why-its-a-risky-tool-for-finding-drug-patents/

- Different Types of Patent Searches – What’s Available and Why Use Them?, accessed August 4, 2025, https://sourceadvisors.co.uk/insights/knowledge-hub/different-types-of-patent-searches/

- Top 18 Patent Databases – The only list you will ever need! – GreyB, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.greyb.com/blog/patent-databases-best-search-platforms/

- The Risks of Using Free Patent Search Tools – XLSCOUT, accessed August 4, 2025, https://xlscout.ai/the-risks-of-using-free-patent-search-tools/

- Using Google Patents to Find Drug Patents? Here’s 15 Reasons Why You Shouldn’t, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/using-google-patents-to-find-drug-patents-heres-15-reasons-why-you-shouldnt/

- Limitations of Google Patents Advanced Search for Invalidation …, accessed August 4, 2025, https://dev.to/patentscanai/limitations-of-google-patents-advanced-search-for-invalidation-what-ip-professionals-need-to-know-3ep2

- Why Google Patents Is Not a Good Solution to Identify Drug Patents – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/why-google-patents-is-not-a-good-solution-to-identify-drug-patents/

- The Hidden Pitfalls of Searching Drug Patents on Google Patents – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-hidden-pitfalls-of-searching-drug-patents-on-google-patents/

- DrugPatentWatch | Software Reviews & Alternatives – Crozdesk, accessed August 4, 2025, https://crozdesk.com/software/drugpatentwatch

- Our search for a reliable patent intelligence solution ended with DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/

- Revolutionizing Patent Landscaping: Combining Human Supervision and AI in Identifying Tech Clusters for Pharmaceutical and Biotechnology Innovation – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/revolutionizing-patent-landscaping-a-human-supervised-ai-approach-to-identify-tech-clusters/

- Evaluating The Effectiveness And Limitations Of Google Patent Search And Impact Of Artificial Intelligence Technologies On Paten – IJCRT, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.ijcrt.org/papers/IJCRT2412515.pdf

- Are there differences between Google Patents, Espacenet, The Lens and PatentScope?, accessed August 4, 2025, https://patents.stackexchange.com/questions/23195/are-there-differences-between-google-patents-espacenet-the-lens-and-patentscop

- A Business Professional’s Guide to Drug Patent Searching – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-basics-of-drug-patent-searching/

- The Strategic Value of Orange Book Data in Pharmaceutical Competitive Intelligence, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-strategic-value-of-orange-book-data-in-pharmaceutical-competitive-intelligence/

- How to Conduct a Drug Patent FTO Search: A Strategic and Tactical Guide to Pharmaceutical Freedom to Operate (FTO) Analysis – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/how-to-conduct-a-drug-patent-fto-search/

- Conducting a Biopharmaceutical Freedom-to-Operate (FTO) Analysis: Strategies for Efficient and Robust Results – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/conducting-a-biopharmaceutical-freedom-to-operate-fto-analysis-strategies-for-efficient-and-robust-results/

- Advanced patent searching techniques | CAS, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.cas.org/resources/cas-insights/patent-searching-going-beyond-basics-increase

- Patent Search Services – Patent Validity Search – Clarivate, accessed August 4, 2025, https://clarivate.com/intellectual-property/patent-intelligence/patent-search-services/

- Unique Challenges for Patents in the Pharmaceutical Industry …, accessed August 4, 2025, https://gearhartlaw.com/unique-challenges-for-patents-in-the-pharmaceutical-industry/

- Challenging the USPTO’s Patent Term Adjustment calculation: An uphill battle | DLA Piper, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.dlapiper.com/en/insights/publications/synthesis/2024/challenging-the-usptos-patent-term-adjustment-calculation

- Maximizing Patent Term in the United States: Patent Term Adjustment, Patent Term Extension, and the Evolving Law of Obviousness-Type Double Patenting | Thought Leadership, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.bakerbotts.com/thought-leadership/publications/2025/january/maximizing-patent-term-in-the-united-states

- Calculating Patent Term Adjustment (PTA) – An Overview – More Than Your Mark®, accessed August 4, 2025, https://norrismclaughlin.com/mtym/drafting-patents/calculating-patent-term-adjustment-pta-an-overview/

- Introduction to Patent Term Extensions (PTE) – Fish & Richardson, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.fr.com/insights/ip-law-essentials/intro-patent-term-extension/

- 7 Advanced Google Patents Search Tips – GreyB, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.greyb.com/blog/google-patents-advanced-search/

- Google Patents Search – A Definitive Guide by GreyB, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.greyb.com/blog/google-patents-search-guide/

- How to do Chemical Markush Structure Search Patent? – GreyB, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.greyb.com/blog/chemical-structure-search-patent/

- Navigating the Complexities of Biologic Drug Patents – PatentPC, accessed August 4, 2025, https://patentpc.com/blog/navigating-complexities-biologic-drug-patents

- Securing Innovation: A Comprehensive Guide to Drafting and Prosecuting Patent Applications for Biologic Drugs – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/drafting-drug-patent-applications-for-biologic-drugs/

- Tips for stronger IP searches during biologics R&D – CAS, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.cas.org/tips-stronger-ip-searches-during-biologics-rd

- www.questel.com, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.questel.com/resourcehub/a-guide-to-bio-sequence-patent-searching/#:~:text=Using%20a%20dedicated%20bio%20sequence,to%20obtain%20complete%20search%20results.

- A Guide to Bio Sequence Patent Searching – Questel, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.questel.com/resourcehub/a-guide-to-bio-sequence-patent-searching/

- Orbit Intelligence – Patent Analytics & Search Software – Questel, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.questel.com/patent/ip-intelligence-software/orbit-intelligence/

- Biopharmaceutical Patenting: The Importance of Prior Art Searches – PatentPC, accessed August 4, 2025, https://patentpc.com/blog/biopharmaceutical-patenting-the-importance-prior-art-search

- Where Can I Identify Relevant Patents Using Non-Patent Literature? – Patentskart, accessed August 4, 2025, https://patentskart.com/where-can-i-identify-relevant-patents-using-non-patent-literature/

- Non-Patent Literature – MDPI, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.mdpi.com/2673-8392/1/1/19

- Why non-patent literature can make or break your business – IP.com, accessed August 4, 2025, https://ip.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/IQ_NPL_ebook_P2.pdf

- Inherent Anticipation in the Pharmaceutical and Biotechnology Industries – PMC, accessed August 4, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4526724/

- Conducting a Patent Landscape Analysis for Drugs – ChemIntel360, accessed August 4, 2025, https://chemintel360.com/conducting-a-patent-landscape-analysis-for-drugs/

- The Importance Of Patent Landscape Analysis To Business Strategy – TT Consultants, accessed August 4, 2025, https://ttconsultants.com/the-importance-of-patent-landscape-analysis-to-business-strategy/

- Patent landscape analysis—Contributing to the identification of technology trends and informing research and innovation funding policy – PubMed Central, accessed August 4, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10034625/

- Patent Landscape Visualization: Intellectual Property Analysis Tools – Dev3lop, accessed August 4, 2025, https://dev3lop.com/patent-landscape-visualization-intellectual-property-analysis-tools/

- Expert Guide To Patent Landscape Analysis – TT Consultants, accessed August 4, 2025, https://ttconsultants.com/patents-as-your-gps-a-guide-to-patent-landscape-analysis/

- Competitive Landscape Analysis: Advantages of Visualization – XLSCOUT, accessed August 4, 2025, https://xlscout.ai/competitive-landscape-analysis-advantages-of-visualization/

- Leveraging Drug Patent Data for Strategic Investment Decisions: A Comprehensive Analysis, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/leveraging-drug-patent-data-for-strategic-investment-decisions-a-comprehensive-analysis/

- Using Google Patents for Drug Patent Research: A Comprehensive Guide, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/using-google-patents-for-drug-patent-research-a-comprehensive-guide/

- Optimize a Freedom to Operate Search with AcclaimIP™, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.acclaimip.com/infringement/optimize-a-freedom-to-operate-search/

- Taking Advantage of the New Purple Book Patent Requirements for Biologics, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.morganlewis.com/pubs/2021/04/taking-advantage-of-the-new-purple-book-patent-requirements-for-biologics

- Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations | Orange Book – FDA, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-approvals-and-databases/approved-drug-products-therapeutic-equivalence-evaluations-orange-book

- Drug Patent Research: Expert Tips for Using the FDA Orange and Purple Books, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/drug-patent-research-expert-tips-for-using-the-fda-orange-and-purple-books/

- (PDF) Google Patents: The global patent search engine – ResearchGate, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/280301154_Google_Patents_The_global_patent_search_engine

- The Dangers of Free Patent Search Tools | PatSnap, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.patsnap.com/resources/blog/the-dangers-of-free-patent-search-tools/

- Compare Google Patents vs. PowerPatent in 2025 – Slashdot, accessed August 4, 2025, https://slashdot.org/software/comparison/Google-Patents-vs-PowerPatent/

- Compare PCS vs. Google Patents in 2025 – Slashdot, accessed August 4, 2025, https://slashdot.org/software/comparison/Dolcera-PCS-vs-Google-Patents/

- Google Patents Search: A Complete Guide to Finding and Reviewing Patents Online, accessed August 4, 2025, https://abounaja.com/blog/google-patents-search-a-complete-guide-to-finding-and-reviewing-patents-online

- Navigating the opportunities and risks of patenting AI-designed drugs: Part 3 – Potential obstacles, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.fpapatents.com/news-insights/insights/navigating-the-opportunities-and-risks-of-patenting-ai-designed-drugs-part-3-potential-obstacles/

- How to Use Patent Data Analytics for Portfolio Decisions – PatentPC, accessed August 4, 2025, https://patentpc.com/blog/how-to-use-patent-data-analytics-for-portfolio-decisions

- Structure Search – Patsnap Help Center, accessed August 4, 2025, https://help.patsnap.com/hc/en-us/articles/19217213957021-Structure-Search

- Bio Sequence Searches | Dexpatent, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.dexpatent.com/biosequence-search/

- Intellectual Property Solutions – IP Solutions – Clarivate, accessed August 4, 2025, https://clarivate.com/intellectual-property/

- What’s the best way to ask patent attorneys or agents in the US to participate in user research? : r/patentlaw – Reddit, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.reddit.com/r/patentlaw/comments/177bx8u/whats_the_best_way_to_ask_patent_attorneys_or/

- Freedom to Operate: How to Safely Launch Products – UpCounsel, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.upcounsel.com/freedom-to-operate

- Considerations for combined Patentability and Freedom to Operate (FTO) Searches, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.tprinternational.com/combined-patentability-and-freedom-to-operate-fto-search/

- Freedom to Operate Opinions: What Are They, and Why Are They Important? | Intellectual Property Law Client Alert – Dickinson Wright, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.dickinson-wright.com/news-alerts/arndt-freedom-to-operate-opinions

- Freedom to Operate Search: A Short Guide – Parola Analytics, accessed August 4, 2025, https://parolaanalytics.com/guide/fto-search-guide/

- How Much Does a Drug Patent Cost? A Comprehensive Guide to Pharmaceutical Patent Expenses – DrugPatentWatch – Transform Data into Market Domination, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/how-much-does-a-drug-patent-cost-a-comprehensive-guide-to-pharmaceutical-patent-expenses/

- Patent Litigation Statistics: An Overview of Recent Trends – PatentPC, accessed August 4, 2025, https://patentpc.com/blog/patent-litigation-statistics-an-overview-of-recent-trends

- DrugPatentWatch 2025 Company Profile: Valuation, Funding & Investors | PitchBook, accessed August 4, 2025, https://pitchbook.com/profiles/company/519079-87

- Revolutionizing the Fight Against Biologic Drug Patent Thickets – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/revolutionizing-the-fight-against-biologic-drug-patent-thickets/

- Biologics, Biosimilars and Patents: – I-MAK, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.i-mak.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Biologics-Biosimilars-Guide_IMAK.pdf

- Pharmaceutical Patent Abuse: To Infinity and Beyond! | Association for Accessible Medicines, accessed August 4, 2025, https://accessiblemeds.org/resources/blog/pharmaceutical-patent-abuse-infinity-and-beyond/