Introduction: The Strategic Imperative of Drug Patents

In the high-stakes world of pharmaceutical innovation, a single, well-crafted drug patent strategy can be the definitive line between market dominance and obscurity. For business professionals navigating this complex terrain, transforming raw scientific data and legal frameworks into actionable competitive advantages isn’t just a skill—it’s a superpower. How do you take a groundbreaking scientific discovery, a molecule with the potential to change millions of lives, and build an impenetrable fortress around it, shielding it from competitors while maximizing its commercial potential? The answer lies not in a single legal document, but in a comprehensive, dynamic, and deeply integrated drug patent strategy—a strategic roadmap that blends legal savvy, market insight, and scientific precision.1

The pharmaceutical industry thrives on innovation, but it is fundamentally a race against time. From the moment a patent application is filed, a 20-year clock starts ticking.3 This may seem like a generous period of exclusivity, but it’s a deceptive figure. The arduous journey of drug development—spanning preclinical research, multiple phases of rigorous clinical trials, and a demanding regulatory review process—can easily consume 10 to 15 years of that term.1 The result is an effective market exclusivity period, the time a company actually has to sell its product without generic competition, that often shrinks to a mere 7 to 12 years.3 This compressed timeline places immense pressure on companies to not only protect their initial invention but to strategically manage its entire lifecycle to ensure a viable return on an astronomical investment.

Beyond Protection: Patents as the Cornerstone of the Pharma Business Model

It’s impossible to overstate the foundational role of patents in the pharmaceutical ecosystem. They are more than mere legal shields; they are the fundamental pillars upon which the entire drug development model is built. A patent grants an inventor the exclusive right to make, use, and sell their invention, creating a temporary monopoly that is the primary economic engine driving the industry forward.1 This exclusivity is the indispensable mechanism that allows companies to recoup the vast costs associated with bringing a new medicine to market and, crucially, to fund the research and development (R&D) for the next generation of therapies.4

This unique economic model, built on the bedrock of patent protection, seeks to strike a delicate balance between incentivizing private-sector innovation and ensuring public access to medicine. Consequently, patent strategy in the pharmaceutical sector is not a siloed function confined to the legal department. It is a core element of corporate strategy, profoundly influencing which drug candidates are pursued, how R&D portfolios are structured, and how development is financed. For startups and smaller biotech firms, a robust patent portfolio is often the most critical asset for attracting venture capital and securing the partnerships necessary for survival and growth.9 In essence, the patent is not just a byproduct of innovation; it is the enabler of it.

The High-Stakes Economics of Innovation: Justifying the Monopoly

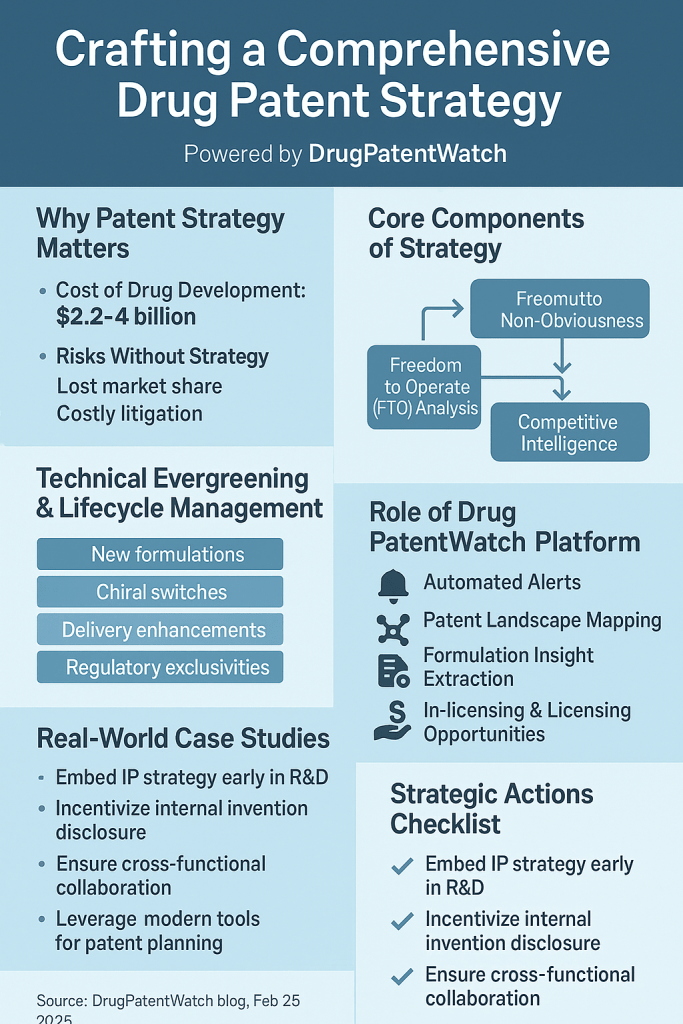

The justification for this temporary monopoly is rooted in the staggering economics of drug development. The journey from a promising compound in a lab to an approved medicine on a pharmacy shelf is one of the most expensive and risky commercial endeavors in any industry. Estimates for the average cost to develop a new drug vary, but consistently run into the billions, with recent analyses from Deloitte and others placing the figure at over $2.2 billion per asset.4 Some studies suggest the capitalized cost, accounting for failures, can approach $4 billion or even more.12 This figure accounts for the high attrition rates in drug development, where for every one drug that successfully makes it to market, many others fail in preclinical or clinical stages.

To offset these immense costs and risks, pharmaceutical companies invest a substantial portion of their revenues back into R&D. Data from industry leaders like Merck, Pfizer, Johnson & Johnson, and Eli Lilly consistently show R&D expenditures ranging from 15% to over 28% of their total sales.12 In 2020 alone, Merck spent $13.6 billion on R&D, representing 28.3% of its revenue, while Pfizer invested $9.4 billion, or 22.4% of its revenue. This level of reinvestment is the lifeblood of the industry, fueling the discovery of future therapies.

However, this narrative, while accurate, is incomplete. A deeper analysis of pharmaceutical company financials reveals a more complex reality. While R&D spending is undeniably high, it is often dwarfed by expenditures on selling, general, and administrative (SG&A) costs, which include marketing and sales. One analysis of six major drug makers found that while 11% of revenues went to R&D, a staggering 31%—nearly three times as much—was allocated to marketing and administration. A separate 2020 analysis by AHIP of the ten largest pharmaceutical companies found that seven of them spent more on selling and marketing than on R&D, with the collective gap amounting to $36 billion.

This doesn’t invalidate the need for R&D investment, but it reframes the purpose of the patent monopoly. The exclusive revenue stream generated by a patent is not solely an R&D incentive; it is a powerful commercialization engine. It funds the entire go-to-market apparatus, from massive sales forces and physician outreach to multi-million-dollar direct-to-consumer advertising campaigns. This commercial reality is the primary driver behind the aggressive, sophisticated, and often controversial lifecycle management strategies that define the modern pharmaceutical patent playbook. A successful patent strategy must be robust enough not only to protect the underlying science but also to defend a multi-billion-dollar commercial franchise for as long as legally and strategically possible. This understanding transforms patent strategy from a defensive necessity into a central pillar of offensive corporate strategy.

Section 1: Laying the Foundation – The Anatomy of a Drug Patent Portfolio

To the uninitiated, a drug may seem to be protected by “a patent.” The reality is far more complex and strategically layered. A single successful drug is rarely, if ever, protected by a single patent. Instead, it is shielded by a meticulously constructed portfolio of patents, each with a distinct purpose, scope, and expiration date. This multi-layered “web of protection,” often referred to as a “patent thicket,” is designed to create a formidable fortress around the innovation, making it exceedingly difficult for competitors to enter the market.5 Building this fortress requires a deep understanding of the different types of patents available and how they can be strategically deployed in concert.

The Cornerstone: The Composition of Matter Patent

At the very heart of any drug patent portfolio lies the composition of matter patent. This is the foundational patent, the cornerstone of the entire structure, and it provides the broadest and strongest form of protection.4 It covers the new chemical entity (NCE) or new molecular entity (NME) itself—the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) that is the core of the medicine.4

As defined by the U.S. Supreme Court, a composition of matter includes “all compositions of two or more substances and all composite articles, whether they be the results of chemical union, or of mechanical mixture, or whether they be gases, fluids, powders or solids”. In the pharmaceutical context, this means the patent claims the specific chemical structure of the drug molecule. This “base patent” is typically the first to be filed, often early in the discovery phase, and its 20-year term establishes the initial period of market exclusivity.2

To be granted, a composition of matter patent must meet three stringent criteria :

- Novelty: The molecule must be new and not previously disclosed in any public forum, such as a scientific publication or another patent.

- Non-Obviousness (Inventive Step): The invention must not be an obvious modification of a known compound to a person having ordinary skill in the art. This is often the most contentious and heavily litigated requirement.

- Utility: The invention must have a specific, substantial, and credible utility. For a drug, this means it must have a demonstrated therapeutic effect.

Securing a strong, defensible composition of matter patent is the primary goal of any early-stage drug patent strategy. It is the most difficult type of patent for a generic competitor to challenge or design around, and it forms the bedrock upon which all subsequent layers of protection are built.4

Building the Fortress Walls: The Role of Secondary Patents

While the composition of matter patent is the cornerstone, a fortress is not built with a single stone. The true strength of a modern drug patent portfolio comes from the strategic layering of numerous secondary patents. These patents do not cover the core molecule itself but instead protect every conceivable aspect of the drug’s development, formulation, manufacturing, and use. This deliberate strategy creates a dense and overlapping network of protection—the “patent thicket”—that serves as a powerful deterrent to generic competition.5

The strategic value of a patent thicket lies not in the individual strength of any single secondary patent, but in its cumulative deterrent effect. A generic competitor must navigate a minefield of intellectual property. They don’t just have to invalidate or design around one patent; they may have to confront dozens. This dramatically increases the legal risk, financial cost, and time required to bring a generic product to market. This transforms patent strategy from a simple legal exercise into a form of economic warfare. The objective is often not to win every potential court battle, but to make the prospect of litigation so daunting and expensive that competitors are deterred from even attempting a challenge, or are pushed towards settlements that are highly favorable to the brand manufacturer.

The key types of secondary patents that form the walls of this fortress include:

Formulation Patents

These patents protect the specific recipe or formulation of the final drug product. They cover the unique combination of the active ingredient with various inactive ingredients (excipients), carriers, or delivery mechanisms.3 A formulation patent might protect an extended-release version of a pill that allows for once-daily dosing instead of twice-daily, a specific coating that improves the drug’s stability, or a novel nanoparticle delivery system that enhances bioavailability.22 These patents are strategically valuable because they can offer genuine patient benefits—like improved compliance or reduced side effects—while simultaneously creating a new, 20-year patent term that extends well beyond the expiration of the original composition of matter patent.

Method-of-Use / New Indication Patents

Perhaps one of the most powerful tools in the lifecycle management arsenal, a method-of-use patent protects a new way of using a known drug.3 This is the legal foundation for drug repurposing. If a company discovers that a drug originally approved for hypertension is also effective at treating a different condition, like hair loss, it can obtain a new method-of-use patent for that new indication. This can breathe new life into an older compound, opening up entirely new markets and revenue streams. A classic example is Pfizer’s Viagra; beyond the original compound patent, the company secured method-of-use patents specifically for the treatment of erectile dysfunction, which became the drug’s blockbuster indication and extended its commercial life.1

Process Patents

Instead of protecting the drug itself, a process patent protects a specific, novel, and non-obvious method of manufacturing that drug.3 For complex molecules like biologics, the manufacturing process can be as innovative as the product itself. A process patent can create a significant hurdle for generic manufacturers, who must either prove their manufacturing process is different and non-infringing or invest in developing an entirely new process from scratch, which can be costly and time-consuming.

Other Key Patent Types

The patent thicket can be further reinforced with several other specialized types of patents:

- Polymorph Patents: These protect specific crystalline structures of the drug molecule. Different polymorphs can have different properties, such as stability or solubility, and patenting a specific, advantageous form can create another barrier to entry.18

- Chiral Switch Patents: Many drug molecules are “chiral,” meaning they exist as a pair of mirror-image molecules called enantiomers. Often, one enantiomer is therapeutically active while the other is inactive or may even cause side effects. A drug initially marketed as a 50/50 mixture (a racemate) can be “switched” by developing and patenting the single, more effective enantiomer. AstraZeneca’s Nexium (esomeprazole) is a famous example of a successful chiral switch from the racemic drug Prilosec (omeprazole).22

- Metabolite Patents: These patents cover the active metabolites that a drug is converted into within the body.

- Delivery Device Patents: For drugs that require a specific device for administration, such as an inhaler for an asthma medication or an auto-injector for a biologic, the device itself can be patented. This can force competitors to develop their own delivery system, adding another layer of complexity and cost.

By strategically combining these different patent types, a company can construct a formidable and resilient portfolio. The following table provides a summary of these key components of the pharmaceutical patent armory.

| Patent Type | What It Protects | Strategic Value/Purpose | Example |

| Composition of Matter | The new chemical/molecular entity (API) itself. | The foundational, broadest, and strongest protection; establishes the initial monopoly. | The original patent on atorvastatin (Lipitor). |

| Formulation | The specific “recipe” of the drug product, including excipients and delivery mechanisms. | Extends exclusivity with improved versions (e.g., extended-release), enhances patient compliance, creates new patent term. | Bristol-Myers Squibb’s Glucophage XR, an extended-release version of metformin. |

| Method of Use | A new therapeutic use or indication for a known drug. | Revitalizes older drugs, opens new markets, and creates a new layer of patent protection for a new patient population. | The use of sildenafil (Viagra) for erectile dysfunction, a different use from its original cardiovascular purpose.1 |

| Process | A novel and non-obvious method of manufacturing the drug. | Creates a significant hurdle for generics, especially for complex biologics, forcing them to develop alternative processes. | A patented process for synthesizing a complex API with higher purity and yield. |

| Polymorph | A specific crystalline form of the active ingredient. | Protects a more stable or soluble form of the drug, which can be a key feature of the marketed product. | Patents on specific crystalline forms of an API that are used in the final tablet. |

| Chiral Switch | The single, therapeutically active enantiomer of a previously marketed racemic drug. | Offers an improved version of an older drug with potentially better efficacy or fewer side effects, creating a new product with a new patent life. | AstraZeneca’s Nexium (esomeprazole) as a follow-on to the racemic Prilosec (omeprazole).22 |

| Delivery Device | The physical device used to administer the drug (e.g., inhaler, auto-injector). | Forces biosimilar/generic competitors to develop their own device, adding significant development time, cost, and regulatory hurdles. | Sanofi’s patents on the Lantus SoloSTAR insulin pen, which extended market protection for its insulin glargine product. |

Section 2: The Strategic Blueprint – Integrating Patent Strategy Across the Drug Lifecycle

A winning patent strategy is not a static document drafted by lawyers and then filed away. It is a living, breathing component of corporate strategy that must be woven into the fabric of the company’s operations from the earliest stages of discovery through to commercialization and beyond. A reactive, siloed approach to patent management is a recipe for missed opportunities, unnecessary risks, and ultimately, commercial failure.1 The most successful pharmaceutical companies adopt a proactive, forward-looking mindset, integrating patent considerations into every stage of the drug development lifecycle. This means transforming patent strategy from an afterthought into a concurrent, collaborative process involving R&D, clinical, legal, and commercial teams all working in concert.10

Phase 1: Discovery and Preclinical – Laying the Strategic Groundwork

The decisions made in the earliest phases of R&D have profound and lasting implications for a drug’s ultimate patent strength and commercial viability. This is where the strategic foundation is laid.

The Primacy of Patent Landscape Analysis

You wouldn’t build a multi-billion-dollar manufacturing plant without surveying the land, and you shouldn’t invest hundreds of millions in a drug candidate without first conducting a thorough patent landscape analysis. This process involves systematically searching and analyzing existing patents, patent applications, and scientific literature to create a comprehensive map of the intellectual property terrain in a specific therapeutic area.28

A robust landscape analysis serves several critical strategic functions:

- Identifying “White Space”: It reveals areas with limited patent coverage, highlighting opportunities for innovation where a company can establish a strong, defensible patent position with a lower risk of infringement.31

- Assessing Competitor Activity: It provides invaluable competitive intelligence, showing which companies are active in the space, what technologies they are pursuing, and where their R&D efforts are focused. This can inform decisions on which drug candidates to prioritize or deprioritize.5

- Avoiding Infringement: It identifies existing patents that could block the development and commercialization of a new drug, allowing a company to “design around” them or seek a license early in the process, long before significant resources are committed.28 A 2022 study found that 68% of pharma companies using landscape analyses successfully avoided infringement lawsuits, saving an average of $15 million per case.

Strategic Filing: The “File Early, File Smart” Doctrine

In the United States and most of the world, patent rights are awarded to the “first to file” an application, not the “first to invent”. This places a premium on filing early to secure a priority date, which establishes your invention’s place in line against all subsequent filings and disclosures. A common and effective tactic is to file a provisional patent application. This is a less formal and less expensive filing that secures a priority date for one year, during which the company can conduct further research and gather more data before filing a more detailed non-provisional application.1 This “file early” approach is about beating competitors to the patent office and laying the groundwork for future protection.

The Timing Dilemma

While the “first-to-file” system encourages early filing, this must be balanced against a critical strategic trade-off. As previously discussed, the 20-year patent term begins on the date of filing. Every day that filing is delayed is potentially an extra day of high-value, post-approval market exclusivity added to the end of the patent’s life, a decade or more in the future.10 This makes the decision of

when to file one of the most important financial calculations a company can make.

The optimal strategy is not to file as soon as an idea is conceived, but to file at the latest possible moment that does not jeopardize the patent’s validity. This requires a sophisticated understanding of what constitutes a “public disclosure” or “public use” that could invalidate a future patent. A key insight from legal precedent is that Phase I clinical trials, which primarily establish a drug’s safety in healthy volunteers, often do not generate the efficacy data needed to demonstrate that the invention “works for its intended purpose.” Therefore, they may not trigger the one-year “public use” grace period in the U.S.. This suggests that a company can often safely delay filing a patent application until after Phase I is complete and Phase II (which begins to test for efficacy) has started. This seemingly small delay of a year or two in the early stages can translate into an additional one or two years of blockbuster sales on the back end, a difference worth billions of dollars.

This sophisticated risk analysis—balancing the legal risk of a competitor filing first against the immense financial gain of extending the effective patent term—is the essence of a “file smart” strategy. It requires a deep integration of legal, clinical, and commercial thinking and necessitates a culture of “patent awareness” that permeates the entire scientific organization.10 Every researcher and clinician must understand that their day-to-day activities, from conference presentations to scientific publications, have multi-million-dollar implications for the company’s future revenue.

Phase 2: Clinical Development – Balancing Disclosure and Protection

As a drug candidate moves into the costly and lengthy clinical development phase, the patent strategy must evolve to manage new challenges and capitalize on new opportunities.

The Clinical Trial Conundrum

Clinical trials, by their nature, involve a degree of public disclosure. Trial protocols are often registered on public databases like ClinicalTrials.gov, and results are eventually published. This creates a tension between the need for transparency in clinical research and the need to protect nascent intellectual property. The primary strategy for managing this risk is to ensure that all clinical trial investigators, site staff, and other partners are bound by strict confidentiality and non-disclosure agreements (NDAs). This legally prevents them from publicly disclosing inventive concepts before a patent application can be filed.

Mining Clinical Trials for New IP

Far from being just a risk, the clinical development process is a fertile ground for generating valuable new intellectual property. The intensive study of a drug in human subjects often uncovers new, unexpected, and patentable inventions that can be used to build out the patent thicket.2 A proactive, integrated team should be constantly looking for opportunities to file secondary patents on:

- Novel Formulations: Clinical studies might reveal that a new extended-release formulation is more effective or has fewer side effects.

- New Dosing Regimens: The optimal dose and frequency of administration discovered during Phase II or III trials can be patented.

- Methods of Administration: A trial might show that administering the drug with food significantly improves absorption, a finding that could be protected with a method-of-use patent.

- New Indications: A drug being tested for one disease might show unexpected efficacy in treating another, creating a valuable opportunity for a new indication patent.

- Combination Therapies: Clinical research may demonstrate that the drug is particularly effective when used in combination with another known therapy, leading to a patent on the combination treatment.

By systematically identifying and patenting these clinical-stage innovations, a company can add multiple layers of protection that will extend its market exclusivity long after the original composition of matter patent expires.

Phase 3: Commercialization – Aligning IP with Market Strategy

As a drug approaches regulatory approval and commercial launch, the patent strategy must be fully aligned with the company’s commercial goals. The strength and breadth of the patent portfolio directly impact pricing power, market access, and the ability to attract partners and investors.2

Building the Bridge from R&D to Market

The transition from a research-focused organization to a commercial entity is a critical inflection point. There must be a seamless bridge between the R&D, legal, and commercial teams. The commercial team’s market analysis and go-to-market strategy should inform the patent strategy. For example, if the commercial plan is to target a specific patient sub-population, the patent team should ensure there are claims in the portfolio specifically covering the use of the drug in that group.

The Role of Patents in Attracting Investment

For many pre-commercial biotech companies, their patent portfolio is their single most valuable asset. A strong, well-prosecuted, and strategically layered portfolio is a powerful signal to potential investors and pharmaceutical partners. It demonstrates that the company’s core innovation is protected, that there is a clear path to market exclusivity, and that the potential for a significant return on investment exists.9 When seeking funding or negotiating a licensing or acquisition deal, the ability to present a robust and defensible patent estate is paramount. It de-risks the investment for the other party and can dramatically increase the valuation of the company.

Section 3: Extending the Golden Age – Mastering Lifecycle Management and “Evergreening”

The expiration of a blockbuster drug’s primary patent is one of the most feared events in the pharmaceutical industry. The resulting “patent cliff” can wipe out 80-90% of a product’s revenue in a matter of months as low-cost generics flood the market.3 To counteract this, companies employ a sophisticated set of strategies known as

lifecycle management or, more controversially, “evergreening”. This involves the strategic use of secondary patents and regulatory exclusivities to extend a drug’s commercial life far beyond the term of its initial patent.18

While critics argue that these practices can stifle competition and keep drug prices high, proponents contend they are essential for recouping the massive costs of R&D and for funding the incremental innovations that can lead to genuine patient benefits, such as improved safety, efficacy, or convenience.41 Regardless of the debate, mastering these strategies is a critical component of any comprehensive drug patent playbook. The most sophisticated approaches do not rely on a single tactic but strategically

stack multiple technical and regulatory exclusivities, creating a complex and staggered timeline of protection that is incredibly difficult for competitors to penetrate.

The Art of the Second Act: Technical Evergreening Strategies

Technical evergreening strategies are rooted in science and R&D. They involve creating new, patentable improvements to an existing drug product. These are not just legal maneuvers; they often represent real scientific advancements that can enhance the product’s value proposition.

New Formulations and Delivery Systems

One of the most common and effective evergreening tactics is to develop a new formulation of a drug as its original patent nears expiration. This could be a sustained-release version that allows for once-daily dosing, a new injectable form, or an orally disintegrating tablet that is easier for certain patients to take. As long as the new formulation is novel, non-obvious, and offers a clinical advantage, it can be patented, starting a new 20-year term of protection.

This strategy offers several advantages. First, it can provide a meaningful benefit to patients, improving compliance and potentially leading to better health outcomes. Second, because the new formulation is based on a known and approved active ingredient, it may qualify for a shorter, less expensive FDA approval pathway. Classic examples include Eli Lilly’s development of a once-weekly, sustained-release version of Prozac and Bristol-Myers Squibb’s launch of Glucophage XR, an extended-release formulation of its diabetes drug metformin.

New Routes of Administration

Closely related to new formulations is the development of entirely new ways to deliver a drug. If a migraine medication is only available as an oral tablet, developing and patenting a new formulation for intranasal delivery can create a new product line with its own patent protection. This was precisely the strategy employed by GlaxoSmithKline for its blockbuster migraine drug, Imitrex (sumatriptan), to extend its market exclusivity.

Chiral Switching (Stereoselectivity)

This highly scientific strategy leverages the chemistry of chiral molecules. Many drugs are sold as a racemic mixture, which contains equal parts of two mirror-image enantiomers. Often, only one of these enantiomers is responsible for the drug’s therapeutic effect, while the other may be inactive or contribute to side effects. A “chiral switch” involves isolating, developing, and patenting the single, active enantiomer as a new and improved drug.

The most famous example of this strategy is AstraZeneca’s Prilosec (omeprazole), a blockbuster acid-reflux drug. As Prilosec’s patents were nearing expiration, AstraZeneca developed and launched Nexium (esomeprazole), which contained only the single (S)-enantiomer. AstraZeneca successfully argued that Nexium offered superior clinical efficacy and secured new patents, allowing it to transition a significant portion of the market from Prilosec to the newly protected Nexium before generic omeprazole became available.22

Combination Products

Another powerful strategy is to combine an existing drug with one or more other active ingredients into a single, fixed-dose combination pill.4 If the combination is novel and offers a therapeutic advantage (such as improved efficacy or better patient compliance than taking the pills separately), it can be patented. This strategy is particularly common in areas like HIV treatment, where multi-drug cocktails are the standard of care. The creation of Truvada, which combined the antiretroviral drugs tenofovir and emtricitabine into a single pill, revolutionized HIV treatment and prevention and was protected by its own set of patents.

The Regulatory Toolkit: Leveraging Exclusivity Provisions

Beyond patenting new inventions, pharmaceutical companies can also leverage a powerful set of regulatory exclusivities granted by the FDA. These exclusivities are separate from patents and provide additional periods of market protection, often running concurrently with or even extending beyond the patent term.

The Hatch-Waxman Act – A Grand Bargain

The Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984, commonly known as the Hatch-Waxman Act, was a landmark piece of legislation that created the modern generic drug industry in the U.S..44 It struck a “grand bargain”: in exchange for creating an abbreviated pathway for generic drug approval, the Act provided brand-name drug manufacturers with several valuable forms of exclusivity to compensate them for the time lost during the lengthy FDA review process.44

- Patent Term Extension (PTE): This is a critical provision that allows a company to apply to have the term of one patent on a new drug extended to restore some of the time lost during clinical trials and FDA review. The extension can be for up to five years, though the total effective patent life post-approval cannot exceed 14 years.1 This allows companies to reclaim a portion of their most valuable period of market exclusivity.

- Data Exclusivity: This provision protects the clinical trial data that a brand company submits to the FDA to prove its drug is safe and effective. For a drug containing a New Chemical Entity (NCE), the FDA is prohibited from approving a generic version that relies on that data for five years from the date of the brand drug’s approval.45 A three-year period of data exclusivity is also available for new clinical investigations on previously approved drugs, such as for a new indication or formulation.18

The Orphan Drug Act (ODA)

To incentivize the development of drugs for rare diseases (defined in the U.S. as conditions affecting fewer than 200,000 people), Congress passed the Orphan Drug Act in 1983.50 In addition to tax credits and research grants, the Act provides a powerful incentive:

seven years of market exclusivity for a drug that receives “orphan drug” designation.50 This exclusivity period begins on the date of FDA approval and prevents the FDA from approving any other version of the same drug for the same rare disease indication for seven years, regardless of the drug’s patent status. This can provide a crucial period of protection, especially for drugs with weak or expired patents.

Pediatric Exclusivity

To encourage drug companies to study their products in children, the FDA can issue a Written Request for pediatric studies. If a company completes these studies in accordance with the request, it is rewarded with an additional six months of market exclusivity.18 This six-month extension is particularly valuable because it is tacked on to

all existing patent and regulatory exclusivities for that drug, including any patent term extensions and orphan drug exclusivity. It is one of the most widely used and effective extension tactics in the industry.

For a business strategist, the key is to understand that these exclusivities create a complex, overlapping timeline. The “patent expiration date” is often a misleadingly simple concept. The real strategic question is, “What is the effective loss of exclusivity (LOE) date?” Answering this requires a dynamic model that maps out all relevant patents, their potential for extension, and all applicable regulatory exclusivities. This complex map, not a single date, is the true timeline that must guide all strategic planning, from R&D investment in follow-on products to forecasting the inevitable revenue cliff.

Section 4: Charting a Global Course – International Patent Strategy and the PCT

In today’s interconnected world, the pharmaceutical market is unequivocally global. A blockbuster drug generates revenue not just in one country, but across dozens of markets in North America, Europe, Asia, and beyond. Consequently, a patent strategy that is confined to a single jurisdiction, even one as large as the United States, is a fundamentally flawed and losing strategy. Protecting an invention in the U.S. alone leaves it completely vulnerable to being legally copied, manufactured, and sold by competitors in every other country in the world. A comprehensive drug patent strategy must, therefore, be a global one, designed to secure protection in all key commercial markets.

Thinking Globally: Why a US-Only Strategy is a Losing Strategy

The decision of where to file for patent protection is a critical strategic choice that must be closely aligned with the company’s long-term commercialization plan. It is not feasible or cost-effective to file in every country. Instead, companies must prioritize key markets based on a careful analysis of several factors :

- Market Size and Potential: Which countries represent the largest potential revenue opportunities for the specific drug?

- Regulatory Environment: How predictable and efficient is the drug approval process in that country?

- Patent Enforcement: Does the country have a robust legal system that reliably enforces patent rights? Filing a patent in a country where infringement is rampant and legal recourse is weak may be a waste of resources.

- Competitive Landscape: Where are key competitors located and likely to launch their own products?

By mapping out a global commercialization strategy early, a company can develop a corresponding global patent filing strategy that protects its most valuable current and future markets.

The Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT): Your Global Launchpad

Navigating the process of filing patents in multiple countries can be complex, time-consuming, and extraordinarily expensive. Each country has its own patent office, its own laws, its own deadlines, and its own language requirements. Fortunately, there is a powerful international mechanism designed to streamline this process: the Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT).56

Administered by the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), the PCT provides a unified system for filing a single “international” patent application in one language, at one patent office, which has the same effect as filing separate national applications in all of the PCT’s 158 member states.56 It is important to note that the PCT system does not grant a “world patent”; the decision to grant a patent remains the sovereign right of each national or regional patent office. However, the PCT provides a centralized and simplified pathway to get to that point.

The Strategic Advantage of Delay

The single most important strategic benefit of using the PCT is the time it provides. Under the traditional “Paris Convention” route for international filing, a company must file all of its foreign patent applications within 12 months of its initial (priority) filing. At this early stage, a company often has very limited clinical data and a high degree of uncertainty about a drug’s ultimate commercial potential. Committing to the enormous expense of multiple national filings at this point is a significant financial gamble.

The PCT system, however, allows an applicant to delay the “national phase entry”—the point at which they must file and prosecute applications in individual countries—for up to 30 or 31 months from the original priority date.60 This provides an additional 18 months of invaluable “strategic breathing room.”

How to Use the PCT Delay Strategically

This 18-month delay is not just a procedural convenience; it is a powerful strategic tool that fundamentally alters the risk profile of global commercialization. During this period, a company can:

- Gather More Data: By the 30-month mark, a company may have progressed from early Phase I to having initial Phase II data. This provides a much clearer picture of the drug’s efficacy, safety profile, and likelihood of success, allowing for a much more informed decision about which markets are worth pursuing.

- Secure Funding and Partnerships: The extended timeline provides more opportunity to attract investors or secure a partnership with a larger pharmaceutical company before having to commit to the high costs of national phase filings. A positive set of Phase II data can dramatically increase the value of the asset and the company’s negotiating leverage.

- Refine the Patent Strategy: During the PCT international phase, the application is subjected to an “International Search” and a “Written Opinion” on patentability from an International Searching Authority (ISA). This provides early feedback on the strength of the patent claims and highlights any potential prior art issues. The applicant can then amend the claims during the international phase before entering the national phase, strengthening their position and potentially saving time and money during national examination.

- Manage Capital Efficiently: The PCT allows a company to defer the very large costs associated with national phase entry—including official filing fees, translation costs, and local patent attorney fees—for an additional 18 months. This allows for more efficient capital allocation, as funds can be directed toward critical R&D activities instead of speculative legal fees.58

The PCT effectively transforms a high-risk, high-uncertainty decision at 12 months into a much more data-driven, strategically sound decision at 30 months. It allows a company to treat its global patent portfolio like a venture capital investment. For a relatively low initial cost, the PCT application keeps the option open to pursue patent protection in over 150 countries. Then, using the clinical and commercial data gathered during the extended delay, the company can make a much more targeted “Series B” investment, choosing to enter the national phase only in those countries that offer the most promising return. This dynamic and financially efficient approach to building a global IP footprint is an essential component of a modern, comprehensive drug patent strategy.

Section 5: The Competitive Battlefield – Intelligence, Freedom to Operate, and Risk Mitigation

In the intensely competitive pharmaceutical landscape, a successful patent strategy cannot be developed in a vacuum. It must be forged in the crucible of the competitive environment, informed by a deep understanding of rivals’ activities and fortified against potential legal challenges. This requires a dual-pronged approach: an offensive strategy based on robust competitive intelligence to anticipate and outmaneuver competitors, and a defensive strategy based on rigorous Freedom to Operate analysis to ensure your own path to market is clear of infringement risks. These two activities are not separate; they are two sides of the same coin, and the data gathered for one should feed directly into the other, creating a virtuous cycle of strategic insight.

Offensive Strategy: Competitive Patent Intelligence

Pharmaceutical competitive intelligence (CI) is the systematic process of collecting, analyzing, and transforming information about rival companies into actionable insights that support strategic decision-making.62 It goes far beyond simple market research, encompassing a deep dive into competitors’ R&D pipelines, regulatory strategies, commercial infrastructure, and, most importantly, their patenting activities.62

Using Patent Data as a Crystal Ball

Patent databases are one of the most powerful and underutilized sources of competitive intelligence. Because companies must file patents early in the development process to protect their inventions, patent applications serve as an invaluable early warning system. They can reveal a competitor’s strategic direction, research priorities, and specific pipeline assets years before that information is disclosed in a press release, at a scientific conference, or in a clinical trial registration.32 By systematically monitoring patent filings, a company can:

- Identify emerging competitive threats long before they become a commercial reality.

- Detect shifts in competitors’ R&D focus, such as a move into a new therapeutic area or a new technological modality (e.g., from small molecules to biologics).

- Uncover “stealth programs”—research projects with significant patent activity but no public disclosure.

- Identify potential partners or acquisition targets by spotting smaller companies with strong and innovative patent portfolios in a niche area of interest.31

Practical Application with Tools like DrugPatentWatch

The sheer volume of patent data can be overwhelming. Specialized platforms and databases are essential for transforming this raw data into structured, actionable intelligence. Tools like DrugPatentWatch are designed specifically for the pharmaceutical industry and provide a powerful suite of features for competitive intelligence.65 A strategic CI program can leverage such a platform to:

- Monitor Competitor Filings: Set up automated alerts to be notified whenever a key competitor files a new patent application in a specific therapeutic area or for a particular class of compounds. This allows for real-time tracking of their R&D activities.31

- Track Patent Litigation: Follow ongoing patent litigation and settlement agreements. This can provide critical insights into the strength of a competitor’s patents and, in the case of settlements, can signal the likely timing of an early generic or biosimilar entry.65

- Reverse-Engineer Formulation Strategies: By carefully analyzing the claims, examples, and detailed descriptions within a competitor’s formulation patents, it is often possible to deduce their strategies for enhancing solubility, stability, or bioavailability. This can inform your own formulation development and design-around efforts.

- Identify “White Space” Opportunities: Use patent landscape mapping tools to visualize the patent density in a given field. These maps can quickly identify crowded areas to avoid and less-populated “white spaces” that represent opportunities for innovation with a clearer path to patentability.31

Defensive Strategy: Freedom to Operate (FTO) Analysis

While competitive intelligence is about looking outward at competitors, Freedom to Operate (FTO) analysis is about looking inward at your own product and ensuring it has a clear path to market. An FTO analysis is a detailed investigation to determine whether a planned product, process, or service is at risk of infringing on the valid, in-force patent rights of a third party.68

Conducting a thorough FTO analysis is not just a legal formality; it is a critical risk mitigation tool and a strategic imperative. The consequences of launching a product that infringes on a competitor’s patent can be catastrophic, leading to costly litigation, court-ordered injunctions forcing the product off the market, substantial damages, and irreparable harm to a company’s reputation.69

When and How to Conduct an FTO Analysis

FTO is not a one-time, pre-launch check. To be effective, it must be an iterative process that begins early in R&D and is updated at key milestones throughout the development lifecycle.71 Conducting an FTO analysis early, before a product design is finalized, provides the maximum flexibility to make changes and “design around” any blocking patents that are identified.

The FTO process generally involves four key steps:

- Scope Definition: Clearly define the specific features of your product that will be searched, the key geographic markets where you plan to launch, and the relevant timeframe for the search.

- Searching: Conduct comprehensive searches of patent databases (such as those from the USPTO, EPO, and WIPO) to identify any issued patents or pending applications with claims that could potentially cover your product.69

- Analysis: A qualified patent attorney or IP professional must then carefully analyze the claims of the identified patents to provide a legal opinion on the risk of infringement. This involves interpreting the scope of the claims and comparing them to the features of your product.69

- Action: Based on the risk assessment, the company can make a strategic decision. If the risk is low, they may proceed with development. If a high-risk blocking patent is identified, the options include:

- Licensing: Negotiating a license with the patent holder to use their technology.

- Designing Around: Modifying the product to avoid infringing on the patent’s claims.

- Challenging the Patent: Attempting to invalidate the blocking patent in court or through a post-grant proceeding at the patent office.

- Abandoning the Project: In some cases, the risk may be too high, and the most prudent decision is to halt the project before investing further.68

FTO Case Studies – Lessons from the Trenches

The importance of FTO is best illustrated by real-world examples. In the infamous case of Kodak v. Polaroid, Kodak was found to have willfully infringed on seven of Polaroid’s instant photography patents. The result was a court order to halt all sales, a massive product recall, and damages that ultimately cost Kodak nearly $1 billion—a devastating blow from which its instant camera business never recovered.

Conversely, a well-executed FTO can pave the way for market entry. When the Indian pharmaceutical company Ranbaxy planned to launch a generic version of the antibiotic cefuroxime axetil in the U.S., it identified a process patent held by Apotex that appeared to block its manufacturing method. However, a meticulous FTO analysis revealed a subtle but critical difference: Ranbaxy’s process used acetic acid as a solvent, whereas the Apotex patent claimed the use of sulfoxides, amides, or formic acid. Based on this narrow distinction, the court granted Ranbaxy a declaratory judgment of non-infringement, giving it the freedom to operate and successfully launch its product.

Ultimately, companies that treat FTO as a mere legal clearance checkbox are squandering a priceless strategic asset. An integrated strategy recycles the data from a defensive FTO search back to the R&D and business development teams. The FTO report should not just state the level of risk; it should provide strategic guidance. For example, it might conclude: “The risk of infringement is high due to Competitor X’s dense patent thicket around extended-release formulations. However, our search reveals they have no patents covering transdermal delivery for this compound class. This represents a potential ‘design-around’ opportunity that also aligns with an unmet patient need for less frequent dosing. We recommend R&D explore this path.” This approach transforms a legal cost center into a powerful engine for value creation and strategic R&D guidance.

Section 6: Navigating the Patent Cliff – Strategies for a Graceful Descent

For every blockbuster drug, the day of reckoning is inevitable. The moment the last key patent or regulatory exclusivity expires, the protective walls crumble, and a flood of low-cost generic or biosimilar competitors rushes in. This event, known as the “patent cliff,” is characterized by a sudden, sharp, and often brutal decline in revenue for the branded product.14 Effectively managing this loss of exclusivity (LOE) is one of the most critical challenges in pharmaceutical strategy. While the cliff cannot be entirely avoided, a proactive and multi-faceted strategy can transform a potential free-fall into a more controlled and graceful descent, preserving significant value long after the primary patent has expired.

Understanding the Patent Cliff

The term “patent cliff” is not hyperbole. The financial impact of generic entry is immediate and severe. Generic drugs are typically priced 80-90% lower than their branded counterparts, and because they are therapeutically equivalent, payers and pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) rapidly switch patients to the cheaper alternative.3 As a result, it is common for a branded drug to lose 80% or more of its market share within the first year of generic competition.38

The history of the pharmaceutical industry is littered with examples of this phenomenon. When Pfizer’s cholesterol-lowering drug Lipitor, once the best-selling drug in the world with annual sales exceeding $10 billion, lost its patent protection in 2011, its sales plummeted dramatically.14 The scale of this challenge is massive; between now and 2030, it is estimated that drugs with over $300 billion in annual revenue are at risk of losing exclusivity, with 190 drugs, including 69 blockbusters, facing their own patent cliffs.77

The most crucial lesson for any business leader is that the patent cliff is not a sudden event to be dealt with at the last minute. It is the predictable culmination of a strategic failure that began a decade or more earlier. Effective mitigation is not about last-minute tactical maneuvers; it is the result of long-term, proactive lifecycle planning that is integrated into a drug’s development from the very beginning. A company facing a patent cliff in 2030 without a next-generation follow-on product already in late-stage clinical trials is already too late.

Pre-LOE Strategies: Maximizing Value Before the Fall

The 12 to 24 months leading up to the loss of exclusivity is a critical period for maximizing the value of the branded product and preparing the market for what comes next.

Strategic Price Increases

A common, though highly controversial, practice is “surge pricing.” This involves implementing systematic and often significant price increases on the branded drug in the final years and months of its monopoly. The rationale is to extract the maximum possible revenue from the product before the price collapses due to generic competition. For example, one major pharmaceutical company began gradually increasing the price of its nerve pain medication as early as three years before its LOE to brace for the looming revenue cliff. However, this strategy must be managed carefully, as excessive price hikes can attract negative attention from payers, policymakers, and the public, and a historical analysis has shown that price increases greater than 9% can actually have a negative impact on revenues and profits.

Rebate and Formulary Management

In the years leading up to LOE, brand manufacturers must strategically manage their relationships and contracts with payers and PBMs. Initially, high rebates are offered to secure a preferred position on the drug formulary. As LOE approaches, the dynamic shifts. Payers, anticipating the switch to cheaper generics, become less demanding. This allows the manufacturer to terminate or reduce rebate contracts, boosting net revenue in the final months of exclusivity without a significant loss of formulary access. At the same time, the company can begin offering aggressive rebates on its next-generation product to encourage payers to favor it and facilitate a smooth transition for patients.

Post-LOE Strategies: Softening the Landing

Once the patent cliff arrives, the focus shifts to strategies that can soften the financial impact and retain a portion of the market.

Authorized Generics

One of the most direct ways to compete in the new generic market is to launch an authorized generic. This is a generic version of the drug that is produced by the brand manufacturer itself (or by a partner with its permission) and marketed under a different name.25 Because it is identical to the branded product, it does not require a separate FDA approval process. By launching an authorized generic, the brand company can enter the generic market immediately, capture a share of the generic revenue, and create price competition for the other generic manufacturers, thereby squeezing their profit margins. Pfizer employed this strategy effectively with Lipitor, launching its own authorized generic to maintain a foothold in the market after losing exclusivity.

Next-Generation Products and “Product Hopping”

The single most effective long-term strategy to mitigate the patent cliff is to make the original product obsolete by developing a superior, next-generation follow-on product. The goal is to switch as many patients as possible from the old drug to the new, patent-protected drug before the original’s patent expires, effectively migrating the revenue stream to a new product with a fresh period of exclusivity.

This can involve any of the evergreening strategies discussed previously, such as developing an extended-release formulation with more convenient dosing or a combination product with enhanced efficacy. In some cases, companies have engaged in more aggressive tactics known as “product hopping,” where they not only introduce the new version but also take steps to remove the old version from the market, forcing patients and physicians to switch. For example, when Forest Laboratories was facing patent expiration for its twice-daily Alzheimer’s drug memantine, it introduced a new, once-daily extended-release version (Namenda XR) and attempted to severely restrict access to the original formulation, a move that drew significant legal and regulatory scrutiny.

Patient Access Programs

For some drugs with high brand loyalty, patients may be willing to stick with the branded product even after cheaper generics become available. To encourage this, companies can implement robust patient access programs, such as co-pay cards and financial assistance programs, that reduce the out-of-pocket cost for commercially insured patients. This strategy can help retain a loyal patient base and soften the erosion of market share. Novartis, for example, extended its co-pay assistance program for its multiple sclerosis drug Gilenya following its LOE in 2022 to delay the impact of generic competition and help patients stay on the branded therapy.

Ultimately, navigating the patent cliff successfully requires a holistic and forward-thinking approach. It reframes R&D portfolio management from a linear process to a continuous, overlapping cycle. As soon as a new drug enters late-stage development, the R&D and commercial teams should already be planning and working on its replacement or a significant line extension. The patent strategy must then be aligned with this continuous innovation cycle, protecting not just the current blockbuster but also the vital bridge to the next one.

Section 7: Landmark Battles and Defensive Tactics – Learning from the Titans

The theoretical principles of patent strategy are best understood through the lens of real-world application. The pharmaceutical industry has been the arena for some of the most complex, high-stakes, and consequential intellectual property battles in modern business history. By dissecting the strategies employed by the titans of the industry in these landmark cases, we can extract invaluable, actionable lessons on both offensive and defensive patent tactics. These case studies reveal how the “patent thicket” is constructed and wielded not just as a legal shield, but as a powerful competitive weapon.

Case Study Deep Dive: The Titans of the Patent Thicket

The following cases represent masterclasses in modern pharmaceutical lifecycle management, demonstrating how a combination of prolific patenting, aggressive litigation, and strategic settlements can extend a drug’s monopoly far beyond what was envisioned by its original patent.

Humira (adalimumab) – The Masterclass in Evergreening

AbbVie’s strategy for its blockbuster anti-inflammatory drug, Humira, is arguably the most cited and studied example of a successful—and controversial—patent thicket in history. Humira, first approved in 2002, became the world’s best-selling drug, with peak annual sales exceeding $20 billion. This unprecedented commercial success was protected by an equally unprecedented patent fortress.

AbbVie and its predecessor, Abbott, constructed a massive patent thicket around Humira, filing a staggering 247 patent applications in the U.S. alone. The most telling statistic is that 89% of these applications were filed after Humira was already approved by the FDA and on the market. This relentless post-approval patenting was a deliberate strategy to create a dense web of overlapping IP that would delay biosimilar competition for as long as possible. While the primary patent on the adalimumab molecule expired in 2016, AbbVie’s thicket of secondary patents—covering everything from new formulations and manufacturing processes to specific methods of use for different autoimmune diseases—was designed to extend its monopoly for a total of 39 years.79

This strategy was not accidental. A 2021 investigation by the U.S. House Committee on Oversight and Reform revealed that AbbVie had worked with the consulting firm McKinsey & Company as early as 2010 to develop a plan to “broaden” Humira’s “patent estate” specifically to “minimize the risk of competition”.81

The impact was profound. AbbVie used its massive patent portfolio to sue every company that attempted to launch a biosimilar version in the U.S. Faced with the prospect of years of costly, high-risk litigation fighting over 100 patents, every biosimilar competitor eventually settled with AbbVie, agreeing to delay their U.S. launch until 2023. This strategy secured AbbVie an additional seven years of monopoly sales in the U.S. compared to Europe, where biosimilars launched in 2018. The estimated cost of this delay to the American healthcare system was over $14 billion.79 The Humira case is a powerful illustration of how a patent thicket can be used to create such significant legal and financial uncertainty that it effectively blocks competition, even if many of the underlying patents are potentially weak.

| Strategic Tactic | Description | Impact on Exclusivity |

| Primary Patent Expiration | The core patent on the adalimumab molecule expired in 2016. | In a simple model, this would have been the LOE date. |

| Post-Approval Patent Filings | AbbVie filed over 220 patent applications after Humira’s 2002 FDA approval. | Created a dense “thicket” of secondary patents with later expiration dates. |

| Formulation Patents | Patents on new formulations, such as a higher-concentration, citrate-free version that reduced injection pain. | Created new patent barriers and was used to switch patients to a new, protected version. |

| Method of Use Patents | Patents covering the use of Humira for new indications like Crohn’s disease, psoriasis, and ulcerative colitis. | Each new indication was protected by its own set of patents, expanding the thicket. |

| Aggressive Litigation | AbbVie sued every potential biosimilar entrant for infringement of dozens of patents. | Created immense legal cost and uncertainty for competitors, delaying their market entry. |

| Favorable Settlements | All biosimilar competitors settled, agreeing to a staggered launch schedule beginning in 2023. | Secured AbbVie an additional 7 years of U.S. monopoly sales, worth billions of dollars. |

Enbrel (etanercept) – The 30-Year Fortress

Amgen’s strategy for its anti-inflammatory biologic, Enbrel, provides another compelling case study in extending a drug’s lifespan. Through a combination of strategic patenting, high-stakes litigation, and a fortuitous quirk of patent law, Amgen has managed to protect Enbrel from biosimilar competition in the U.S. until 2029—a remarkable 31 years after its FDA approval and 37 years after the first patent application was filed.

While Amgen, like AbbVie, built a thicket of secondary patents around Enbrel, the key to its extraordinary longevity lies in two specific patents acquired from Roche. These patents, related to a fusion protein and a DNA encoding it, were filed in the early 1990s. Crucially, they were filed just before a change in U.S. patent law that shifted the patent term from 17 years from the date of grant to 20 years from the date of filing. Because of this timing, and a long delay in their examination at the patent office, these patents were not granted until 2011 and 2012. This gave them expiration dates of 2028 and 2029, respectively.

When Novartis’s Sandoz division received FDA approval for its Enbrel biosimilar, Erelzi, in 2016, Amgen sued for infringement of these two late-expiring patents. Sandoz argued that the patents were invalid due to obviousness-type double patenting over Amgen’s earlier patents. However, the courts ultimately sided with Amgen, upholding the validity of the patents. As a result, despite being approved for nearly a decade, no Enbrel biosimilar has been able to launch in the U.S., and none are expected until 2029. The Enbrel case demonstrates how a few strategically important and resilient patents, even if acquired rather than internally developed, can be more critical to long-term exclusivity than the sheer volume of patents in a thicket.

Revlimid (lenalidomide) – The REMS Shield and Settlement Strategy

The case of the multiple myeloma drug Revlimid, marketed by Celgene (now part of Bristol Myers Squibb), showcases a different but equally effective set of tactics for delaying generic competition. While Celgene also built a patent thicket, its strategy uniquely leveraged a regulatory requirement and controlled the supply chain.85

Due to the risk of severe birth defects associated with Revlimid (a derivative of thalidomide), the FDA required Celgene to implement a strict safety and distribution program called a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS). Under this program, Revlimid could only be dispensed by specialty pharmacies under controlled conditions. Celgene then used this FDA-mandated safety program as a shield to block generic competition. When generic companies needed to purchase samples of Revlimid to conduct the bioequivalence studies required for their FDA applications, Celgene repeatedly refused to sell them the drug, citing the safety restrictions of the REMS program. This tactic, which was the subject of a Congressional investigation and antitrust litigation, successfully delayed generic development for years.

Ultimately, like AbbVie, Celgene used its patent thicket and the threat of prolonged litigation to force generic competitors into settlement agreements. However, these settlements came with a unique twist: they included volume restrictions. Generic versions of Revlimid were allowed to enter the market in 2022, years after the primary patent expired in 2019, but the settlement agreements severely limited the quantity of the generic drug they could sell. These volume caps gradually increase but will not be fully lifted until January 2026. This strategy allowed Celgene/BMS to maintain the majority of the market and its high prices for several additional years, effectively creating a slow, controlled erosion of its monopoly rather than a steep cliff.

Defending Your Fortress: Navigating Patent Challenges

These case studies demonstrate the power of an offensive patent strategy. However, companies must also be prepared to defend their patents against challenges from competitors.

The Generic Challenge: Paragraph IV Certification and the 30-Month Stay

The Hatch-Waxman Act provides a specific pathway for generic companies to challenge branded drug patents. When filing an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA), a generic company must make a certification for each patent listed in the FDA’s Orange Book for the branded drug. A “Paragraph IV” certification is a declaration that the generic company believes the patent is invalid, unenforceable, or will not be infringed by their product.3

Filing a Paragraph IV certification is considered an act of patent infringement and gives the brand company 45 days to file a lawsuit. If a suit is filed, it triggers an automatic 30-month stay of FDA approval for the generic drug.45 This gives the brand company time to litigate the patent dispute in court before the generic can enter the market. The first generic company to successfully file a Paragraph IV certification is rewarded with 180 days of generic market exclusivity, a powerful incentive to challenge patents.

Post-Grant Challenges at the USPTO

In addition to federal court litigation, the America Invents Act of 2011 created streamlined, trial-like proceedings at the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office’s Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) for challenging the validity of issued patents. The two most relevant for the pharmaceutical industry are:

- Inter Partes Review (IPR): Allows a third party to challenge a patent’s validity based on prior art consisting of patents or printed publications.

- Post-Grant Review (PGR): Allows a challenge on any ground of invalidity, but must be filed within nine months of the patent’s grant.

These PTAB proceedings are generally faster and less expensive than district court litigation, and they have become a popular tool for generic and biosimilar companies seeking to clear a path to market.

The High Cost of Litigation

A key element of the patent thicket strategy is leveraging the sheer cost of litigation as a deterrent. Patent litigation is incredibly expensive, with the average cost for a case that goes through trial estimated at $3 million, and complex pharmaceutical cases often costing much more, sometimes upwards of $10 million per case.89 When a generic company is faced with a thicket of 100 patents, the potential litigation cost becomes astronomical, making a settlement that delays entry often seem like the more economically rational choice. This reality underscores that the strength of a patent portfolio is measured not only by the legal validity of its claims but also by the economic burden it can impose on would-be challengers.

Section 8: The New Frontiers – Patenting Biologics, AI-Discovered Drugs, and Personalized Medicine

As science and technology continue to advance at a breathtaking pace, the landscape of pharmaceutical innovation is undergoing a profound transformation. The rise of large-molecule biologics, the integration of artificial intelligence into the discovery process, and the advent of personalized medicine are revolutionizing how we treat disease. These new frontiers, however, present formidable and novel challenges to the traditional intellectual property frameworks that have governed the industry for decades. Navigating this evolving terrain requires a forward-looking and adaptable patent strategy that can grapple with unprecedented questions of complexity, inventorship, and subject matter eligibility.

The Complexity of Biologics and Biosimilars

For much of the 20th century, the pharmaceutical industry was dominated by “small molecule” drugs—relatively simple chemical compounds that can be precisely characterized and easily replicated. The new era is increasingly defined by “biologics”—large, complex molecules such as monoclonal antibodies, therapeutic proteins, and vaccines that are derived from living organisms.92

Unlike small molecules, biologics are often impossible to characterize completely. They are not synthesized through a predictable chemical reaction but are produced in living cell lines, and the final product is highly sensitive to the specific manufacturing process. This inherent complexity has two major implications for patent strategy:

- Broader Patent Thickets: The complexity of biologics provides far more opportunities for patenting. Companies can patent not only the primary amino acid or nucleic acid sequence but also countless variations, formulations, and, crucially, every minute detail of the complex manufacturing process.92 This allows for the creation of even denser and more formidable patent thickets than are seen with small molecules.

- The Rise of Biosimilars: Because it is impossible to create an identical copy of a biologic, the generic equivalents are known as “biosimilars”—products that are “highly similar” to the original biologic with “no clinically meaningful differences”.93

To govern this new class of medicines, the U.S. Congress passed the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA) in 2009. This act created an abbreviated regulatory pathway for the approval of biosimilars. In a parallel to Hatch-Waxman, the BPCIA also granted innovator biologics a generous 12 years of data exclusivity from the date of FDA approval, during which the FDA cannot approve a biosimilar application.18

The BPCIA also established a unique and highly complex process for managing patent disputes between innovator and biosimilar companies, often referred to as the “patent dance.” This is a series of prescribed steps and timelines for the two parties to exchange lists of relevant patents and their arguments on infringement and validity before litigation formally begins. This intricate process adds another layer of complexity and cost for biosimilar developers seeking to enter the market.

Artificial Intelligence in Drug Discovery: Who Owns the Invention?

Artificial intelligence is poised to revolutionize drug discovery. AI platforms can analyze vast biological and chemical datasets to identify novel drug targets, design new molecules from scratch, and predict their efficacy and safety with a speed and scale that is impossible for human researchers alone.95 Companies like Insilico Medicine have demonstrated the potential to slash preclinical development timelines from the traditional 5-6 years to under two years.95

This technological leap, however, runs headlong into a fundamental tenet of patent law: inventorship.

The Inventorship Dilemma

U.S. patent law is unequivocal that an inventor must be a “natural person”—a human being.95 This principle was famously tested in the case of

Thaler v. Vidal, where computer scientist Stephen Thaler filed patent applications naming his AI system, DABUS, as the sole inventor. The U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) rejected the applications, and the courts, all the way up to the Supreme Court (which declined to hear the case), affirmed that an AI cannot be an inventor under current law.

USPTO Guidance and the “Significant Human Contribution” Standard

This does not mean that inventions made with the help of AI are unpatentable. In 2024, the USPTO issued crucial guidance clarifying that AI-assisted inventions are patentable, provided that one or more humans made a “significant contribution” to the conception of the invention.95 The guidance suggests that a “significant contribution” could involve:

- Designing, building, or training the AI model for a specific problem.

- Curating the specific data used to train the AI.

- Significantly modifying the AI’s output, for example, by selecting a promising candidate from a large list of AI-generated molecules and then experimentally validating or improving it.95

Merely recognizing and appreciating the output of an AI system without further inventive contribution is generally not enough to qualify for inventorship.

The Shifting Standard of “Obviousness”

A more subtle but perhaps more profound challenge posed by AI relates to the non-obviousness requirement. The standard for non-obviousness is based on what would have been obvious to a “person of ordinary skill in the art”. As AI tools become more powerful and widely available, the capabilities of this hypothetical skilled person are effectively augmented by AI. An invention that would have been a brilliant, non-obvious leap for a human chemist might be considered an “obvious” output for a skilled chemist using a state-of-the-art generative AI model. This will inevitably raise the bar for patentability, making it harder to secure patents for AI-generated discoveries.98

This creates a fascinating paradox for patent strategy. On one hand, AI can be used to generate thousands of examples of molecules, which can help satisfy the heightened disclosure and enablement requirements needed to secure broad patent claims. On the other hand, the very power of the AI tool used to generate those examples weakens the argument that the invention was non-obvious. The future of patenting in the AI era will therefore hinge on meticulous documentation. Companies must shift from simply documenting what was invented to documenting how the human-AI partnership led to the invention. The patent strategy must focus on highlighting the specific, critical, and non-obvious contributions of the human researchers in guiding the AI, interpreting its results, and transforming its output into a real-world invention.

Personalized Medicine: Patenting the Unpatentable?

Personalized medicine, which tailors treatments to an individual’s unique genetic profile, represents the future of healthcare. However, it presents one of the most significant challenges to patent eligibility. Many personalized medicine innovations are based on the discovery of a correlation between a specific genetic biomarker and a patient’s likely response to a particular drug. The problem is that this correlation is a “law of nature”.102

Two landmark Supreme Court decisions have profoundly shaped this area of law:

- Mayo Collaborative Services v. Prometheus Laboratories (2012): The Court ruled that a patent claiming a method for optimizing drug dosage by observing a natural correlation between metabolite levels and drug efficacy was an unpatentable law of nature. The Court found that the additional steps in the patent were merely routine activities that were not sufficiently inventive to transform the natural law into a patent-eligible application.104

- Association for Molecular Pathology v. Myriad Genetics (2013): The Court held that isolated, naturally occurring human DNA sequences (in this case, the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes) were not patentable subject matter because they were products of nature. However, the Court did find that synthetic DNA, or cDNA, could be patentable because it is not naturally occurring.104

These decisions have made it extremely difficult to patent diagnostic methods and other innovations that are based on natural biological correlations. The strategic response for companies innovating in this space has been to focus their patent claims not on the natural law itself, but on a specific, practical, and inventive application of that law. This might include patenting a novel diagnostic kit that uses a new method to detect the biomarker, a new man-made composition of matter (like a synthetic probe), or a specific method of treatment that goes beyond simply stating the natural correlation. Navigating this complex and evolving legal landscape is a critical challenge for the future of personalized medicine.

Conclusion: Weaving a Cohesive and Dominant Patent Strategy

In the intricate and high-stakes tapestry of the pharmaceutical industry, a comprehensive patent strategy is the master thread that weaves together scientific innovation, commercial ambition, and legal fortitude. As we have explored, patents are far more than defensive legal instruments; they are the central economic engine of the industry, the strategic assets that justify billion-dollar R&D investments, and the competitive weapons that secure market dominance.1

The journey from a nascent discovery in the lab to a market-leading therapy is a marathon, not a sprint, and patent strategy must be a constant companion at every step. It begins with a meticulous patent landscape analysis before the first major investment is made, identifying the opportunities and risks that lie ahead. It evolves through the preclinical and clinical phases, balancing the need for disclosure with the imperative of protection, and continuously mining the development process for new, patentable innovations.2 It requires a global perspective, leveraging tools like the Patent Cooperation Treaty to build an international fortress that aligns with a worldwide commercialization plan.58