Imagine this scenario: your health system’s pharmacy budget is finalized for the year, built around the high cost of a blockbuster drug that treats thousands of your patients. Six months later, a generic equivalent hits the market at an 80% discount. The sudden availability is a win for patients, but a catastrophe for your budget. The millions of dollars you overpaid for the branded drug in those intervening months represent a massive, avoidable loss—capital that could have funded a new outpatient clinic, upgraded diagnostic equipment, or hired a dozen new nurses. This isn’t a hypothetical; it’s a reality that plays out in healthcare organizations across the country. And it happens for one simple reason: a failure to understand and strategically track drug patent information.

For too long, the world of pharmaceutical patents has been seen as an arcane, impenetrable domain reserved for lawyers and industry executives. Healthcare leaders—hospital administrators, formulary managers, chief medical officers, and managed care executives—have often viewed themselves as passive participants, forced to react to market events rather than anticipate them. But in an era of skyrocketing healthcare costs, where prescription drugs are a primary and relentless driver of spending, this passive stance is no longer tenable.1

This report is your guide to changing that dynamic. It is built on a single, powerful premise: understanding the drug patent landscape is no longer an ancillary skill but a core competency for modern healthcare leadership. It is about transforming your organization from a price-taker into a proactive, informed stakeholder capable of navigating the complex interplay of innovation, regulation, and competition. Think of patent intelligence as a new kind of diagnostic tool—a stethoscope that allows you to listen to the very heartbeat of the pharmaceutical market, hear the approaching footsteps of generic competition, and make strategic decisions that protect your financial health and enhance patient value.

Over the course of this comprehensive guide, we will embark on a journey to demystify the world of pharmaceutical intellectual property (IP). We will start by dissecting the bedrock of biopharma innovation—the patent itself—to understand its purpose and the economic engine it fuels. We will then build a multi-layered understanding of the “exclusivity stack,” exploring the different types of patents and FDA-granted exclusivities that form a fortress around a brand-name drug. From there, we will navigate the complex U.S. regulatory maze, decoding the landmark legislation that governs the battle between brand and generic manufacturers.

Finally, and most importantly, we will move from theory to practice. I will provide you with a strategist’s toolkit, including practical, step-by-step guides on how to read a patent document and how to use essential resources like the FDA’s Orange and Purple Books. We will see how this intelligence directly impacts the front lines of healthcare delivery, shaping formulary decisions, influencing physician prescribing habits, and ultimately determining the cost of care. My goal is to equip you not just with knowledge, but with a new lens through which to view the pharmaceutical market—a lens that reveals opportunities, mitigates risks, and empowers you to turn patent data into a powerful competitive advantage.

Section 1: The Bedrock of Biopharma Innovation: Deconstructing the Drug Patent

To master the strategic implications of drug patents, we must first understand their fundamental purpose. A patent is not merely a legal document; it is the central gear in the engine of biopharmaceutical innovation. It represents a carefully calibrated, high-stakes bargain between society and the inventor, a bargain designed to solve one of the most difficult problems in economics: how to incentivize the creation of inventions that are incredibly expensive to discover but relatively cheap to copy.

The Grand Bargain: Recouping R&D and Fueling Discovery

At its core, a patent is a legal instrument that grants an inventor the exclusive right to make, use, and sell their invention for a limited time—in the United States and most of the world, this term is 20 years from the date the patent application was filed.3 This is the fundamental “grand bargain” of the patent system: in exchange for fully disclosing the invention to the public, allowing others to learn from it and build upon it, the inventor is awarded a temporary monopoly.7

Nowhere is this bargain more critical than in the pharmaceutical industry. The journey of a new drug from a laboratory concept to a patient’s bedside is one of the most expensive and riskiest commercial ventures on the planet. Estimates for the cost of developing a single new drug range from hundreds of millions to over $2 billion, and the process can easily span 10 to 15 years.9 The vast majority of drug candidates that enter clinical trials—nearly 90%—will fail to ever reach the market.

Without the promise of a patent, this business model would collapse. If a company could spend a decade and a billion dollars to bring a new life-saving drug to market, only to have a competitor immediately copy the molecule and sell it at a fraction of the price, the incentive to undertake that initial investment would vanish. Patents provide the legal shield that allows innovator companies to recoup their massive R&D investments and, ideally, generate a profit that can be reinvested into the search for the next generation of cures.1

This system creates a powerful, self-reinforcing cycle that can be thought of as the Patent-Investment-Innovation Flywheel. It works like this:

- The high cost and immense risk of drug development necessitate billions of dollars in external investment.

- Investors, whether venture capitalists or public shareholders, require a clear mechanism to ensure a return on that high-risk capital.

- A patent on a promising new molecule provides the legal guarantee of a future, temporary monopoly if the drug is successful.

- This legal guarantee is what attracts the necessary capital to fund the long and arduous process of clinical trials.3

- If the drug is approved by regulators like the FDA, the patent-protected monopoly allows the company to set a price that can recoup the initial investment and generate substantial profits.

- These profits are then used to reward investors and, crucially, to fund the company’s next wave of R&D, starting the cycle all over again.

This flywheel reframes the patent from a simple legal document into the linchpin of the entire biopharmaceutical economic model. It is also why patents are often filed very early in the development process, long before a drug’s safety or efficacy has been proven. A strong patent position is essential not just for future protection, but for the immediate task of attracting the investment needed to even begin the journey through clinical development.

The Three Pillars of Patentability: Novelty, Utility, and Non-Obviousness

A patent is not granted lightly. The U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) acts as a gatekeeper, and an invention must clear several high legal hurdles to be deemed patentable.7 For healthcare leaders, understanding these criteria is important because they determine the strength and validity of the patents that underpin a drug’s monopoly.

- Novelty: The invention must be genuinely new. It cannot have been previously patented, described in a printed publication, or otherwise made available to the public anywhere in the world before the patent application was filed.7 A patent examiner will conduct a thorough search of “prior art” to ensure the invention is novel.

- Utility (or Usefulness): The invention must have a practical, real-world purpose. In the context of pharmaceuticals, this means the patented compound or method must have a credible therapeutic application.8 This requirement prevents the patenting of purely theoretical molecules with no known function.

- Non-Obviousness: This is often the most subjective and highly contested requirement. An invention is not patentable if the differences between it and the prior art are such that the invention as a whole would have been obvious to a “person having ordinary skill in the art” (a legal construct representing a typical practitioner in the relevant field).7 This pillar is designed to prevent patents on trivial advancements or predictable combinations of known elements. It is a central point of contention in litigation over “secondary” patents, such as new formulations of an existing drug.

In addition to these three pillars, there is a fourth critical requirement: Enablement. The patent application must describe the invention in such full, clear, concise, and exact terms as to enable any person skilled in the art to make and use it. This is the inventor’s side of the “grand bargain”—the public disclosure that justifies the temporary monopoly.

From Nostrums to New Chemical Entities: A Brief History

To fully appreciate the modern patent system, it’s helpful to understand its historical roots, which are far murkier than today’s highly regulated environment. The term “patent medicine” is often associated with the 18th and 19th centuries, but it referred to something quite different from today’s patented drugs. These were proprietary concoctions, often with colorful names and even more colorful claims, whose ingredients were kept secret.

These “nostrum remedium” (Latin for “our remedy”) were typically trademarked, not patented in the modern sense. They originated in England as remedies granted “patents of royal favor” and were exported to America, where they became notorious for their wild claims and dangerous ingredients. Many of these mixtures were fortified with alcohol, morphine, opium, or cocaine and were tragically marketed for everything from colic in infants to cancer, often with tragic results.

The evolution from this era of secrecy and quackery to our modern system reveals a fundamental philosophical shift. The old system was based on protecting secret formulas. This provided a commercial advantage to the seller but was a public health disaster, as consumers had no idea what they were taking and were often discouraged from seeking legitimate medical care.

The modern patent system is built on the opposite principle: mandated disclosure. In exchange for a limited-time monopoly, the inventor must teach the public exactly what the invention is and how it works, as per the “enablement” requirement. This foundational shift reflects the dual, and often conflicting, goals of today’s system: to harness the power of private enterprise to drive innovation, while simultaneously ensuring that the fruits of that innovation ultimately enter the public domain to advance science and improve public health. This inherent tension between commercial incentives and the public good is a recurring theme that explains many of the complexities and controversies surrounding drug patents today.

Section 2: The Anatomy of Protection: A Multi-Layered Look at Patents and Exclusivities

When a blockbuster drug is launched, its market protection is rarely based on a single patent. Instead, innovator companies construct what can best be described as a “patent fortress”—a multi-layered, overlapping defense system of various types of patents and regulatory exclusivities designed to protect their valuable asset from every conceivable angle and, crucially, to extend its revenue-generating life for as long as possible.8 For any healthcare leader aiming to forecast budgets and manage formularies, understanding the distinct components of this fortress is not just helpful; it’s absolutely critical.

The Patent Fortress: Types of Pharmaceutical Patents

Let’s explore the key types of patents that form the walls, moats, and towers of this intellectual property fortress.

Composition of Matter Patents: The Crown Jewel

This is the “gold standard” of pharmaceutical patents, the very heart of the fortress.9 A

composition of matter patent covers the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) itself—the core molecule or chemical compound that produces the therapeutic effect.14

Its strategic importance cannot be overstated. It provides the broadest and most powerful protection available. If a competitor’s product contains the patented molecule, it infringes the patent, regardless of how it’s formulated, what disease it’s used to treat, or how it’s manufactured.16 The expiration date of the primary composition of matter patent is the single most important event in a drug’s lifecycle, as it typically marks the first real opportunity for generic competition to emerge.

Method of Use Patents: Teaching an Old Drug New Tricks

A method of use patent does not protect a compound itself, but rather a specific, novel way of using it.16 This could involve:

- Repurposing: Discovering that a drug approved for one condition (e.g., heart disease) is also effective for a completely different one (e.g., cancer).3

- New Dosing Regimen: Finding that a new dosing schedule provides superior efficacy or safety.

- New Patient Population: Identifying a new sub-group of patients who benefit from the drug.

These patents are a cornerstone of “lifecycle management.” They allow a company to breathe new commercial life into an older drug, often creating a new stream of protected revenue long after the original composition of matter patent has expired.3 For a healthcare provider, this means that even when a drug’s main patent expires, it may still be protected for certain high-value indications, complicating generic substitution strategies.

Formulation, Process, and Combination Patents

These secondary patents add further layers of defense to the fortress:

- Formulation Patents: These protect the specific “recipe” of the final drug product. This includes the unique combination of the API with inactive ingredients (excipients) or a novel drug delivery system, such as an extended-release tablet, an inhaler device, or a nanoparticle-based formulation.3 These are often aimed at improving patient compliance (e.g., moving from twice-daily to once-daily dosing) or enhancing the drug’s performance.

- Process Patents: These patents protect the specific, innovative method of manufacturing the drug.1 They are especially critical for biologics, where the complex manufacturing process is inextricably linked to the final product’s identity and efficacy.

- Combination Patents: These are granted for therapies that combine two or more distinct active ingredients into a single product, such as a single pill to treat both high blood pressure and high cholesterol.3

To help clarify the hierarchy and strategic purpose of these different patent types, the following table provides a concise summary. For a healthcare leader trying to predict generic entry, this framework is invaluable. It shows that while a late-expiring formulation patent might exist, it’s often a weaker barrier that a generic company can “design around,” whereas the expiration of the core composition of matter patent is the main event to watch.

| Patent Type | What It Protects | Strategic Importance |

| Composition of Matter | The core active molecule or chemical compound itself.19 | The Crown Jewel. Provides the broadest and strongest protection against any generic version.16 |

| Method of Use | A new therapeutic use or indication for an existing drug.1 | Lifecycle Extension. Repurposes old drugs for new markets, creating new revenue streams after the core patent expires.3 |

| Formulation | The specific “recipe” or delivery system (e.g., extended-release tablet, inhaler).6 | Improved Patient Experience. Can enhance compliance, efficacy, or safety, creating a new barrier to entry.16 |

| Process | The specific, innovative method of manufacturing the drug.1 | Critical for Biologics. Can create a formidable barrier for biosimilar competitors, as the process defines the product. |

The Regulatory Shield: Understanding FDA-Granted Market Exclusivity

Operating in parallel to the patent system is a completely separate set of protections granted not by the USPTO, but by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). These are called regulatory exclusivities, and they are statutory periods of market monopoly designed to incentivize specific types of drug development that the market might otherwise neglect.8

Crucially, these exclusivities can block the FDA from approving a competing generic or biosimilar application for a set period, even if all patents on the drug have expired or been invalidated.13 They are an independent and powerful layer of protection.

Key types of FDA exclusivity include:

- New Chemical Entity (NCE) Exclusivity: A 5-year period of exclusivity is granted to a drug that contains an active ingredient (active moiety) never before approved by the FDA. This is a powerful incentive for companies to pursue truly novel, first-in-class medicines.9

- Orphan Drug Exclusivity (ODE): A 7-year period of exclusivity is granted to a drug approved to treat an “orphan disease”—a rare condition affecting fewer than 200,000 people in the U.S. This is designed to encourage R&D in areas with small patient populations that might otherwise be unprofitable.3

- New Clinical Investigation Exclusivity: A 3-year period of exclusivity can be granted for an application that contains reports of new, essential clinical investigations. This typically applies to new uses, new formulations, or new dosage strengths of a previously approved drug.23

- Pediatric Exclusivity (PED): This is a unique incentive that provides an additional 6 months of protection added on to all existing patents and exclusivities for a drug. It is granted if the manufacturer conducts pediatric studies in response to a written request from the FDA.9

- Biologics Exclusivity: The Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA) provides a lengthy 12-year period of exclusivity for new biologic products, reflecting their complexity and high development costs.9

- 180-Day Generic Exclusivity: This is an incentive for the generic industry. The first generic company to file an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) with a successful patent challenge is awarded 180 days of market exclusivity, during which no other generic version can be approved.23

This table provides a quick reference to these complex regulatory tools. For a formulary manager analyzing a new drug for a rare disease, knowing about the 7-year ODE is vital. It means that even if the drug’s patents seem weak or expire early, no generic competition is possible for at least seven years from the approval date, fundamentally altering any financial forecasting.

| Exclusivity Type | Duration | What It Protects / Incentivizes |

| New Chemical Entity (NCE) | 5 years | Truly novel drugs with active ingredients new to the FDA. |

| Orphan Drug (ODE) | 7 years | Development of treatments for rare diseases. |

| Biologics (BPCIA) | 12 years | Innovation in complex, large-molecule biologic therapies. |

| New Clinical Investigation | 3 years | New uses, formulations, or strengths for existing drugs that require new clinical trials. |

| Pediatric (PED) | Adds 6 months | Conducting pediatric studies to ensure drug safety and efficacy in children. |

| 180-Day Generic | 180 days | The first generic company to successfully challenge a brand-name drug’s patent. |

Patent vs. Exclusivity: Two Different Clocks on the Wall

It is absolutely essential to understand that patents and exclusivities are distinct concepts governed by different laws and agencies.25

- Source: Patents are granted by the USPTO. Exclusivity is granted by the FDA.

- Timing: A patent’s 20-year term starts from the filing date, which can be years before the drug is approved. Exclusivity begins on the date of drug approval.25

- Independence: They can run concurrently, overlap, or exist independently. A drug might have years of patent life remaining but no exclusivity, or its patents might expire while it still has years of exclusivity left.8

The true period of monopoly protection for a drug is determined by whichever of these protections—the last-to-expire relevant patent or the last-to-expire FDA exclusivity—lasts longer. This leads to a more sophisticated way of thinking about a drug’s market protection: the “Exclusivity Stack.”

Simply tracking the expiration date of a drug’s main patent is, as one industry report bluntly states, a “rookie mistake that can lead to disastrously inaccurate budget forecasts”. The true barrier to generic entry is this multi-layered stack. At the base is the core composition of matter patent. Layered on top are secondary patents for formulations and new uses. Running alongside this entire patent structure are the various FDA exclusivities. A generic competitor cannot launch until it has cleared every single layer of this stack, either by waiting for it to expire or by successfully challenging it in court. Therefore, strategic planning for healthcare leaders requires a comprehensive mapping of this entire stack to identify the true loss of exclusivity (LOE) date—the final expiration date of the last relevant piece of the puzzle. This transforms the analysis from a simple date lookup into a complex and vital strategic assessment.

Section 3: The Rulebook: Navigating the U.S. Regulatory and Legal Maze

The world of drug patents does not exist in a vacuum. It is governed by a complex and often overlapping web of laws and regulations administered by two powerful federal agencies: the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Understanding the distinct roles of these two gatekeepers, and the landmark legislation that defines their interactions, is essential to grasping the real-world dynamics of pharmaceutical competition.

The Two Gatekeepers: The Roles of the USPTO and the FDA

Think of the journey of a new drug as requiring two separate keys to unlock the market. The USPTO provides the key of invention, while the FDA provides the key of safety and efficacy.

- The USPTO’s Role: The Arbiter of Invention

The USPTO is responsible for examining patent applications and granting patents.1 Its sole focus is on determining whether an invention meets the statutory requirements of patentability: novelty, utility, and non-obviousness. The USPTO’s examiners are technical experts who assess the invention against the backdrop of existing science and technology. Crucially, their mandate does

not include evaluating whether a proposed drug is safe for patients or effective at treating a disease. A patent is a right to exclude others from practicing an invention, not a right to practice the invention yourself. - The FDA’s Role: The Guardian of Public Health

The FDA’s mission is entirely different. It is charged with protecting public health by ensuring that human drugs are safe and effective. The FDA reviews the massive dossiers of preclinical and clinical trial data submitted by a manufacturer in a New Drug Application (NDA) and decides whether to grant marketing approval. The FDA also administers the various regulatory exclusivities we discussed previously, which are designed to further specific public health goals, like developing drugs for rare diseases or for children.1 - The Collaboration (and Disconnect)

While their roles are distinct, the actions of one agency profoundly impact the other, creating a systemic friction that defines the industry. The value of a patent granted by the USPTO is only realized after the drug receives marketing approval from the FDA. This gap is the source of the “effective patent life” problem; a company may hold a patent for a decade while the drug is still in clinical trials, burning through its 20-year term before it can generate a single dollar of revenue.

In recent years, there has been a push for greater collaboration between the USPTO and FDA to address issues like “patent thickets” and high drug prices.33 However, a significant disconnect remains. For example, when a brand company submits a list of patents to be included in the FDA’s Orange Book, the FDA’s role is purely ministerial. The agency lists the patents as submitted; it does not independently verify their accuracy or relevance to the approved drug.37 This has led to accusations that companies can “game the system” by listing patents that are weak or irrelevant, creating additional hurdles for generic competitors. For a healthcare leader, this means recognizing that a drug’s patent filing date is an early signal of potential innovation, but its true commercial and clinical relevance only crystallizes upon FDA approval.

The Hatch-Waxman Act: The Law That Built the Modern Generic Market

Prior to 1984, the U.S. generic drug market was virtually nonexistent. Generic manufacturers faced the same daunting regulatory path as innovators, requiring them to conduct their own costly and time-consuming clinical trials to prove safety and effectiveness—a duplicative and inefficient process. At the time, only 19% of prescriptions in the U.S. were for generics.

The Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984, universally known as the Hatch-Waxman Act, fundamentally reshaped this landscape.39 It was a masterful legislative compromise, creating a balanced framework that simultaneously bolstered incentives for innovation and paved the way for robust generic competition.

- What the Generic Industry Gained:

- The ANDA Pathway: The Act created the Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA). This streamlined process allows a generic manufacturer to gain FDA approval by relying on the innovator’s original safety and efficacy findings. The generic firm only needs to demonstrate that its product is bioequivalent to the brand-name drug—meaning it delivers the same amount of active ingredient to the bloodstream over the same period of time.37 This eliminated the need for duplicative clinical trials, dramatically lowering the cost and time required to bring a generic to market.

- The “Safe Harbor”: The Act created a statutory exemption from patent infringement for activities reasonably related to developing and submitting an ANDA.13 This allows generic companies to begin their development work and conduct bioequivalence studies

before the brand’s patents expire, so they are ready to launch on day one of patent expiry. - What the Brand Industry Gained:

- Patent Term Extension (PTE): To compensate for the patent life lost during the lengthy FDA review process, the Act allows brand companies to apply to have the term of one patent extended for up to five years.7

- Data Exclusivity: The Act created new forms of FDA-administered exclusivity, most notably the five-year New Chemical Entity (NCE) exclusivity, which provides a guaranteed period of monopoly free from generic competition, even if there are no patents on the drug.40

- The Framework for Competition: Paragraph IV and the 30-Month Stay

Perhaps the most ingenious and contentious part of Hatch-Waxman is its unique litigation framework. When filing an ANDA, a generic company must make a certification for each patent listed in the Orange Book for the brand-name drug. A “Paragraph IV” (PIV) certification is a declaration that the generic company believes a listed patent is invalid, unenforceable, or will not be infringed by its product.

This filing is considered a technical, artificial act of patent infringement. It serves as a legal trigger, allowing the brand company to sue the generic manufacturer for patent infringement immediately, long before the generic product is actually on the market. If the brand company files suit within 45 days of receiving notice of the PIV certification, the FDA is automatically barred from granting final approval to the generic for 30 months (or until the court case is resolved, whichever comes first). This “30-month stay” gives the brand company a period of certainty to resolve the patent dispute in court. As a powerful incentive for generics to undertake these risky and expensive legal challenges, the Act grants a 180-day period of marketing exclusivity to the first generic applicant to file a successful PIV challenge.37

The BPCIA: A Brave New World for Biologics and Biosimilars

For decades, the Hatch-Waxman framework applied only to traditional, small-molecule chemical drugs. It did not cover biologics—large, complex molecules like monoclonal antibodies and vaccines that are derived from living organisms.1 Because of their complexity and manufacturing processes, it is impossible to create a chemically identical “generic” copy of a biologic. Instead, competitors develop “biosimilars,” which are products that are “highly similar” to the original biologic with “no clinically meaningful differences” in safety and efficacy.44

To create a pathway for these products, Congress passed the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA) in 2010 as part of the Affordable Care Act.1 While inspired by Hatch-Waxman, the BPCIA created a distinct and in many ways more complex system.

The scientific differences between small molecules and biologics necessitate a different legal and regulatory approach, which has profound strategic implications for healthcare providers.

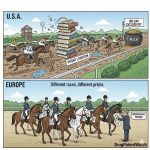

- Scientific Complexity: Small molecules like aspirin are simple, well-defined chemical structures that can be perfectly replicated. Biologics, produced in living cell lines, are large, intricate proteins whose final structure is sensitive to the slightest variations in the manufacturing process.43 This means proving biosimilarity is a far more extensive and expensive undertaking than proving bioequivalence for a generic, often requiring additional clinical data.

- Longer Exclusivity: To incentivize the massive investment required to develop original biologics (and the significant, though smaller, investment for biosimilars), the BPCIA provides a much longer 12-year period of data exclusivity for the innovator biologic, compared to the 5 years for a small-molecule NCE.44

- The “Patent Dance”: The BPCIA introduced a complicated, multi-step process for exchanging patent information and narrowing disputes before litigation, known as the “patent dance.” While the Supreme Court has since ruled that this process is optional, it remains a key feature of the biosimilar landscape.43

- The Purple Book: The BPCIA also led to the creation of the Purple Book, the official FDA resource listing licensed biologics and any approved biosimilars or “interchangeable” products.49 An interchangeable biosimilar has met an even higher standard and can be substituted by a pharmacist without physician intervention, much like a generic drug.

For a healthcare leader, the key takeaway is that the timeline for biosimilar competition is inherently longer, more expensive, and more uncertain than for small-molecule generics. The 12-year exclusivity period provides a long runway of monopoly protection, and the complexity of “patent thickets” around biologics often leads to protracted legal battles. This requires different forecasting models and more conservative budget assumptions when dealing with high-cost specialty biologics.

Section 4: The Commercial Lifecycle: From Filing Day to the Patent Cliff

A drug’s patent is not a static document; it’s the centerpiece of a dynamic commercial lifecycle that begins long before a product ever reaches a patient and extends far beyond its initial expiration date. Understanding this lifecycle—from the erosion of the patent term during development to the strategic maneuvers used to prolong it and the dramatic financial consequences of its ultimate expiry—is crucial for anticipating market shifts and managing healthcare costs.

The 20-Year Myth: Understanding “Effective Patent Life”

One of the most common misconceptions about drug patents is that they provide 20 years of market monopoly. This is a myth. While the statutory term of a U.S. patent is indeed 20 years from its filing date, a significant portion of that time is consumed before the drug can be sold.3

The clock on a patent starts ticking the day the application is filed with the USPTO, often very early in the R&D process. What follows is a long and arduous journey through preclinical research, multiple phases of human clinical trials, and a comprehensive review by the FDA. This entire pre-market process can easily take 10 to 15 years.

The result is that the “effective patent life”—the actual period during which a drug is on the market with patent protection—is consistently and significantly shorter than the nominal 20 years. On average, a new drug enjoys only about 7 to 12 years of market exclusivity before its core patent expires and it faces the threat of generic competition.4 This truncated timeline is the central economic reality that drives the entire industry’s obsession with lifecycle management and patent extension strategies.

Life After Launch: Lifecycle Management and “Evergreening” Strategies

Because the initial period of exclusivity is so limited, innovator companies do not simply wait for their patents to expire. They engage in a continuous and sophisticated set of legal and commercial strategies designed to extend their monopoly for as long as possible. This practice is known within the industry as “lifecycle management” and, more critically by its detractors, as “evergreening”.1

These strategies are not about protecting the original invention, but about creating new layers of IP protection around the successful product. Common tactics include:

- Filing Secondary Patents: As we’ve discussed, companies will file a barrage of new patents on incremental innovations, such as new formulations (e.g., a once-daily version of a twice-daily pill), new methods of use for different diseases, new dosage forms, or different crystalline structures of the API (polymorphs).3

- Creating “Patent Thickets”: This involves strategically building a dense, overlapping web of dozens or even hundreds of patents around a single blockbuster drug. The goal is not necessarily that each individual patent is invincible, but that the sheer volume and complexity of the “thicket” makes it prohibitively difficult, time-consuming, and expensive for a generic or biosimilar competitor to challenge them all.1

- “Product Hopping” or “Product Switching”: In this controversial tactic, a brand manufacturer will introduce a new, slightly modified version of a drug (e.g., a new dosage or formulation) that is covered by new patents, just as the patents on the original version are about to expire. The company then aggressively markets the new version to physicians and patients, effectively destroying the market for the original product just before a generic version can launch.

- “Pay-for-Delay” Settlements: Also known as “reverse payment” settlements, these are agreements where a brand-name company, after being sued by a generic challenger in a Paragraph IV case, pays the generic company to drop its lawsuit and delay the launch of its product for a specified period. Critics argue these deals are anti-competitive, costing consumers billions by keeping cheaper alternatives off the market.1

When the Shield Falls: Anatomy of the Patent Cliff

Despite these defensive strategies, for most drugs, the day of reckoning eventually arrives. The term “patent cliff” is a vivid industry colloquialism that captures the sharp, sudden, and often catastrophic decline in revenue a company experiences when a blockbuster drug finally loses its market exclusivity and is inundated with generic competition.57

The financial impact is staggering. It is not uncommon for a drug that generated billions in annual sales to see its revenue plummet by 80-90% within the first year of generic entry.57 For a pharmaceutical company that relies heavily on one or two key products, the patent cliff represents an existential threat that shapes corporate strategy for years in advance.

This dramatic revenue loss is a direct result of brutal price competition. The entry of generic drugs triggers a rapid and predictable price erosion:

- The first generic competitor typically enters the market at a modest discount to the brand price.

- With the entry of a second competitor, prices fall significantly further.

- Once three to five generic competitors are in the market, prices can plummet by 60% to 90% or more compared to the pre-expiry brand price.60

This dynamic is a boon for payers, providers, and patients, unlocking immense savings. For the innovator company, however, it marks the end of an era of high profitability for that product.

Case Study: The Fall of a Titan – Pfizer’s Lipitor

No case study better illustrates the patent cliff than that of Pfizer’s Lipitor (atorvastatin). For years, Lipitor was the best-selling drug in the history of the pharmaceutical industry, a cholesterol-lowering medication that generated over $125 billion in sales during its patent-protected life.10 Its main patent expiration in the U.S. in November 2011 was a landmark event, a moment the entire industry watched with bated breath.57

Pfizer’s response to the Lipitor patent cliff was a masterclass in reactive defense, employing a multi-pronged strategy to manage the decline and extract as much value as possible from the brand in its final monopoly moments:

- Litigation and Settlement: Years before the expiry, Pfizer was engaged in global patent litigation with generic challengers. In a key move, it reached a settlement agreement with the first challenger, Ranbaxy, which provided certainty about the exact date of generic entry (November 30, 2011). This allowed Pfizer and the market to plan for the event, rather than face uncertainty.

- Aggressive Rebate Programs: In the crucial 180-day period when Ranbaxy was the sole generic competitor, Pfizer went to war on price. It launched the “Lipitor-For-You” program, offering discount cards to insured patients that lowered their co-pay for branded Lipitor to just $4—often less than the co-pay for the new generic.65 It also offered deep rebates to pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) and health plans to keep Lipitor in a preferred position on formularies.

- The Authorized Generic Gambit: Simultaneously, Pfizer did not cede the generic market entirely. It entered into a deal with Watson Pharmaceuticals to launch an “authorized generic”—a chemically identical product, just without the Lipitor brand name. This allowed Pfizer to capture a share of the generic market’s revenue and compete directly with Ranbaxy during its 180-day exclusivity window.57

Case Study: The Thicket Strategy – AbbVie’s Humira

If Lipitor was the classic case of the patent cliff, AbbVie’s Humira (adalimumab) became the new playbook for how to avoid it. Humira, a biologic drug for autoimmune diseases, became the world’s top-selling drug, peaking at over $21 billion in annual sales. Its primary composition of matter patent expired in the U.S. in 2016, yet the first biosimilar competitors did not enter the U.S. market until 2023—a seven-year delay that generated an estimated $114 billion in additional revenue for AbbVie.54

How did they achieve this? Through the most extensive and successful “patent thicket” strategy the industry had ever seen.

- Proactive Fortress Building: Rather than waiting to react at the end of its patent life, AbbVie spent over a decade proactively building a nearly impenetrable fortress of secondary patents. The company filed over 250 patent applications and was granted more than 130 patents in the U.S. for Humira.68

- Layered Defense: These patents covered every conceivable aspect of the product beyond the molecule itself: dozens of patents on manufacturing methods, specific formulations (including a crucial citrate-free version that reduced injection pain), and various methods of use for different autoimmune conditions.69

- The Litigation Barrier: This dense thicket created an insurmountable legal barrier for potential biosimilar competitors. The cost and complexity of challenging over 100 patents simultaneously were prohibitive. Instead of fighting a losing battle in court, every single biosimilar competitor ultimately settled with AbbVie, agreeing to a licensed and staggered market entry beginning in 2023.69

The contrast between the Lipitor and Humira cases reveals a crucial evolution in pharmaceutical strategy. Pfizer’s approach was largely reactive, focused on managing the revenue decline after the primary patent expired. AbbVie’s strategy was intensely proactive, focused on building a defensive fortress for a decade before the primary patent expired. The Humira case demonstrated that the most effective defense against the patent cliff is one that is meticulously planned and executed years in advance. For a healthcare leader, this means that assessing a drug’s future risk of competition requires looking beyond the expiration date of its main patent. The density and complexity of its entire patent portfolio serve as a powerful leading indicator of how aggressively and successfully the innovator will defend its monopoly.

Section 5: The Strategist’s Toolkit: Turning Data into a Competitive Advantage

Knowledge of patent law and market dynamics is powerful, but it’s only actionable if you know where to find the data and how to interpret it. This section is your practical, hands-on guide to the essential tools of the trade. We will move from the theoretical to the tactical, providing you with the skills to read a patent, navigate the key FDA databases, and understand when to leverage more advanced competitive intelligence platforms. This is about transforming you from a passive observer into a data-driven strategist.

How to Read a Patent: A Practical Guide for the Non-Lawyer

At first glance, a patent document can be intimidating—a dense mix of legal jargon and technical description. However, understanding its basic structure can unlock a wealth of strategic information. A utility patent is typically divided into three main parts 72:

- The Cover Page: This provides bibliographic information at a glance: the patent number, issue date, inventor names, assignee (the company that owns the patent), and a brief abstract.

- The Specification (or Detailed Description): This is the scientific heart of the patent. It describes the invention in detail, explains the problem it solves, discusses prior art, and provides examples and data from experiments. It is written to “enable” a person skilled in the art to replicate the invention.73

- The Claims: This is the most important section from a legal perspective. The claims, found at the end of the document, are a series of numbered, single-sentence statements that define the precise legal boundaries of the invention.72 Anything that falls within the scope of a claim is considered infringing.

For competitive intelligence, your focus should be on the claims. Each claim has three parts:

- Preamble: The introduction that identifies the category of the invention (e.g., “A pharmaceutical composition…”).

- Transitional Phrase: A critical legal term that connects the preamble to the body. The word “comprising” is open-ended, meaning the invention includes the listed elements but could also have others. The phrase “consisting of” is closed and restrictive, meaning the invention has only the listed elements and nothing more.73 This distinction is vital for determining the scope of protection and potential ways to “design around” the patent.

- Body: The list of the invention’s essential elements or steps and how they interrelate.

Claims are also structured hierarchically:

- Independent Claims: These stand alone and define the broadest scope of the invention. Claim 1 is typically the primary independent claim.72

- Dependent Claims: These refer back to an independent claim (or another dependent claim) and add further limitations or specifics. For example, “The composition of claim 1, wherein the active ingredient is present in an amount of 5 mg.” A dependent claim is narrower and incorporates all the limitations of the claim it depends on.72 Analyzing this hierarchy allows you to understand the core invention (in the independent claim) and the inventor’s preferred embodiments or specific variations (in the dependent claims).

Decoding the Orange Book: Your Map to the Small-Molecule Landscape

The FDA’s “Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations,” universally known as the Orange Book, is the single most important public resource for patent and exclusivity information on small-molecule drugs in the U.S..39 Mastering this tool is a non-negotiable skill for any healthcare strategist.

Here is a step-by-step guide to using the online Electronic Orange Book (EOB) to find the data you need:

- Access the Database: Navigate to the FDA’s official EOB website. The database is updated daily with new approvals, making it a timely resource.79

- Search for a Specific Drug: The homepage offers several search options. The most direct methods are searching by “Proprietary Name” (the brand name) or “Active Ingredient.” Let’s use the example of searching for the blood thinner “Brilinta” by its proprietary name.

- Interpret the Initial Search Results: The results page will display all approved products matching your search. Here, you’ll find key information like the active ingredient (ticagrelor), dosage form, and the applicant (AstraZeneca). The most important column for an initial assessment is the “TE Code” (Therapeutic Equivalence Code).

- If this column is blank, it means there are no FDA-approved generic equivalents for that specific product.

- If it contains a code beginning with “A” (e.g., “AB”), it signifies that the FDA has determined there are therapeutically equivalent generic products available that can be substituted.

- Drill Down to Patent and Exclusivity Data: To find the monopoly information, locate the brand-name product, which is designated as the “RLD” (Reference Listed Drug). Click on the hyperlinked “Application Number” (e.g., N022433 for Brilinta) associated with the RLD.

- Analyze the Monopoly Information: This click will take you to a detailed product page. At the bottom, you will find a link for “Patent and Exclusivity Information.” This is the goldmine. This page provides a table listing:

- Every U.S. patent that the brand company claims covers the drug.

- The expiration date for each of those patents, including any Patent Term Extensions (PTE) or Pediatric Exclusivity (PED) additions.

- Any FDA-granted regulatory exclusivities and their expiration dates.

This final table provides the raw data needed to begin mapping the drug’s “Exclusivity Stack” and forecasting its true Loss of Exclusivity (LOE) date.

Navigating the Purple Book: The Essential Guide for Biologics

For biologics, the counterpart to the Orange Book is the Purple Book. Its full title is the “Lists of Licensed Biological Products with Reference Product Exclusivity and Biosimilarity or Interchangeability Evaluations”.50 It is the official FDA database for licensed biologics, including their biosimilar and interchangeable competitors.83

While its purpose is similar, there are critical differences from the Orange Book:

- Less Comprehensive Patent Data: This is the most significant distinction. Patent information in the Purple Book is not as robust. Under the BPCIA, patent listings are only required after a biosimilar applicant engages in the “patent dance” with the brand manufacturer. This means the Purple Book often contains an incomplete list of the patents in a biologic’s “thicket” and cannot be relied upon as the sole source for a freedom-to-operate analysis.38

Using the Purple Book is straightforward:

- You can use the simple or advanced search functions to look up a biologic by its brand or proper name.50

- The results page will show the reference product and list any approved biosimilars or interchangeables.83

- The “Patent List” link, accessible from the main navigation or a product’s details page, will display the patent information that has been submitted to the FDA.88

Leveraging Competitive Intelligence Platforms: A Word on DrugPatentWatch

The Orange and Purple Books are indispensable, free government resources. They are the starting point for any analysis. However, they are databases, not strategic intelligence platforms. They provide the raw data, but the work of synthesizing that data with litigation outcomes, clinical trial data, and global patent filings to create an actionable forecast is left to the user.90

This is where specialized commercial platforms become invaluable. Services like DrugPatentWatch are designed specifically for this purpose. They aggregate data from dozens of disparate sources—global patent offices, regulatory agencies like the FDA, court dockets, and clinical trial registries—and curate it into a single, easy-to-use interface.18

The benefits of such a platform include:

- Efficiency: They automate the time-consuming process of data collection and integration, allowing your team to focus on analysis and strategy rather than data entry.

- Completeness: They provide a more holistic view by including international patent data, detailed litigation tracking (e.g., Paragraph IV challenges), and information on drugs still in the development pipeline.90

- Actionable Insights: They often provide their own analysis and forecasting, helping users to quickly identify market entry opportunities, anticipate revenue events, and manage portfolios more effectively.90

This highlights a clear Data-to-Decision Pathway for the modern healthcare strategist.

- Start with a strategic question: “When can I expect biosimilar competition for Humira, and what will the budget impact be?”

- Gather foundational data: Use the Purple Book to identify the reference product and see which biosimilars are already approved and what limited patent data is listed.

- Conduct deeper analysis: Use the USPTO database to pull the full text of the listed patents and analyze their claims to understand the scope of protection.

- Synthesize and monitor: Use a comprehensive platform like DrugPatentWatch to integrate this information with ongoing litigation updates, settlement agreements, and the status of other biosimilars in the pipeline. This platform transforms the raw data points into a dynamic, reliable forecast.

By following this structured pathway, you can move beyond simple data lookups to a robust, ongoing competitive intelligence process that yields superior strategic and financial decisions.

Section 6: The View from the Front Lines: How Patent Status Shapes Healthcare Delivery

We have explored the legal foundations, regulatory frameworks, and commercial lifecycle of drug patents. Now, let’s bring this knowledge to the front lines of healthcare. How does this seemingly distant world of patent law and corporate strategy directly impact day-to-day operations, clinical decisions, and the financial health of your organization? The connections are more direct and profound than you might think.

The Formulary Chessboard: Using Patent Expiry to Manage Drug Spend

At the heart of any health system or managed care organization’s cost-control efforts is the drug formulary—the official list of prescription drugs covered by the plan. The decisions about which drugs make it onto this list, and on what terms, are made by a Pharmacy & Therapeutics (P&T) Committee. This committee is tasked with the difficult job of balancing clinical efficacy, patient safety, and, increasingly, financial sustainability.92

For these P&T committees and the formulary managers who support them, a drug’s patent status is not just a piece of trivia; it is a critical input for strategic planning and budget management.17 Accurately forecasting the Loss of Exclusivity (LOE) date for a high-cost, high-volume branded drug is one of the most powerful levers they have to control pharmaceutical spending.

This intelligence drives a series of strategic actions on the formulary chessboard:

- Pre-LOE Strategy: In the 12 to 18 months leading up to a major patent expiration, a formulary manager’s position strengthens. Knowing that a low-cost alternative is on the horizon provides significant leverage in negotiations with the brand manufacturer. The brand company, desperate to maximize revenue before the cliff, may be willing to offer steeper rebates to maintain preferred formulary status for its final months of exclusivity.

- Post-LOE Execution: The moment a generic or biosimilar becomes available, the formulary is updated. The new, lower-cost alternative is typically moved to the most preferred tier (e.g., Tier 1 with the lowest patient co-pay), while the branded drug may be moved to a non-preferred tier or require prior authorization.92 These utilization management tools are designed to drive rapid substitution, ensuring the health system captures the cost savings as quickly as possible.

The Power of the Pen: Patent Status and Physician Prescribing Habits

A drug’s patent status also exerts a powerful, though often subtle, influence on the prescribing habits of physicians. During the years a drug is under patent protection, its manufacturer invests billions of dollars in marketing efforts aimed directly at prescribers. This includes visits from pharmaceutical sales representatives (“detailing”), sponsored medical education, provision of free drug samples, and other gifts.2

The goal of this enormous expenditure is to build brand awareness, familiarity, and loyalty, ultimately shaping the physician’s choice at the moment of prescription.97 Numerous studies have demonstrated a clear correlation between these industry interactions and a higher rate of prescribing expensive, branded medications.98

What happens when the patent expires? The marketing support for the brand-name drug typically dries up. The sales reps stop visiting, the free samples disappear, and the advertising budget is slashed. At the same time, P&T committees and health plans begin actively promoting the new generic alternative. The result is a measurable shift in prescribing patterns. Research has shown that when marketing activities are restricted, physicians’ prescribing behavior changes, moving away from expensive, patent-protected drugs and towards cheaper, generic equivalents. This reveals that prescribing decisions are influenced not just by pure clinical evidence, but also by the powerful commercial ecosystem that a drug’s patent status creates and sustains.

The Bottom Line: The Macroeconomic Impact of Generic Competition on Healthcare Costs

The cumulative effect of these formulary and prescribing shifts is a massive, deflationary force within the U.S. healthcare system. The availability of generic drugs is arguably the single most effective cost-containment mechanism we have.

The statistics are staggering. Generic drugs now account for approximately 91% of all prescriptions filled in the United States. Yet, due to their dramatically lower prices, they are responsible for only about 13% to 18% of total prescription drug spending.10 This incredible disparity highlights their value. The other 9% of prescriptions—overwhelmingly for on-patent, brand-name drugs—account for over 80% of the nation’s pharmaceutical bill.

Over the last decade, the U.S. healthcare system has saved trillions of dollars thanks to generic drugs, with annual savings now exceeding $400 billion and growing each year.95

“Generic and biosimilar medicines have saved the U.S. healthcare system trillions of dollars over the past decade. For the decade ending in 2023, savings reached an extraordinary $3.1 trillion. The annual savings have shown a consistent upward trend, reaching a record $445 billion in savings in 2023.”

However, the most sophisticated insight for a healthcare leader is to understand the Ripple Effect of a single patent expiration. The impact goes far beyond the simple one-for-one substitution of a brand drug with its generic. When a major blockbuster drug in a therapeutic class goes off-patent, it fundamentally recalibrates the financial dynamics of the entire category.

Consider the statin class for cholesterol management. When Lipitor’s patent expired, low-cost generic atorvastatin flooded the market. P&T committees and PBMs immediately made it the preferred first-line agent.94 This created immense pricing pressure not just on branded Lipitor, but on

all other branded statins that were still on patent, like Crestor. To remain competitive on formularies against a highly effective and now incredibly cheap alternative, the manufacturers of other branded statins were forced to offer much deeper rebates and discounts. Therefore, the expiration of a single key patent didn’t just lower the cost of atorvastatin; it drove down the net cost of the entire therapeutic class, creating a wave of savings that rippled across the entire health system. This systemic impact is a critical strategic consideration for any leader managing a large and diverse pharmaceutical budget.

Conclusion: The Strategic Imperative of Patent Literacy in Modern Healthcare

We have journeyed through the intricate world of pharmaceutical patents, from the fundamental “grand bargain” that fuels innovation to the practical tools and strategic frameworks that can turn complex data into a powerful competitive advantage. We have seen that a drug patent is far more than a legal document; it is a commercial asset, a regulatory trigger, and a strategic weapon that profoundly shapes the cost, accessibility, and delivery of healthcare.

The central argument of this report has been to reframe patent information not as an esoteric subject for specialists, but as an essential and actionable intelligence source for healthcare leaders. In an environment of relentless cost pressures, understanding the “Exclusivity Stack” is no longer optional—it is a core competency. Knowing how to map the fortress of patents and exclusivities around a blockbuster drug allows you to accurately predict the timing of the patent cliff, a predictable event that unlocks billions of dollars in potential savings. Mastering the rulebooks—the Hatch-Waxman Act for small molecules and the BPCIA for biologics—provides the context needed to understand the competitive battles that determine when and how lower-cost alternatives will reach your patients. And learning to use the strategist’s toolkit, from the FDA’s public databases to advanced platforms like DrugPatentWatch, empowers you to move from being a reactive price-taker to a proactive, data-driven decision-maker.

The call to action is clear: for hospital administrators, formulary managers, managed care executives, and physician leaders, patent literacy is a strategic imperative. It is the key to negotiating better contracts, building more accurate budgets, designing smarter clinical pathways, and ultimately, fulfilling the core mission of delivering high-value care. By embracing this knowledge, you can not only protect your organization’s financial health but also play a more active role in bending the cost curve for the entire healthcare system.

The landscape we have explored is not static. The rise of artificial intelligence is poised to revolutionize drug discovery, raising new and complex questions about inventorship and patentability that will reshape the industry in the years to come.103 Ongoing policy debates about drug pricing and patent reform will continue to alter the rules of the game. Therefore, the journey does not end here. This report is a foundation, a new lens through which to view your world. The imperative now is to continue learning, to stay vigilant, and to integrate this strategic intelligence into the very fabric of your organization’s decision-making process.

Key Takeaways

- The “Exclusivity Stack” is the Real Barrier: A drug’s monopoly is a complex fortress of multiple patents (composition, use, formulation) and FDA-granted exclusivities. The true Loss of Exclusivity (LOE) date is the expiration of the last relevant protection, not just the primary patent.

- Know the Rulebooks: The Hatch-Waxman Act (for small-molecule generics) and the BPCIA (for biologics/biosimilars) are the foundational laws governing competition. Their significant differences, especially the 12-year exclusivity for biologics, have major strategic implications for forecasting and budgeting.

- The Patent Cliff is a Predictable Opportunity: The dramatic revenue loss for a brand drug upon generic entry is a predictable event. Proactive analysis of a drug’s patent portfolio, ongoing litigation, and competitor pipelines can forecast its timing and financial impact with remarkable accuracy.

- Master the Toolkit: The FDA’s Orange Book (for small molecules) and Purple Book (for biologics) are essential, free starting points for data gathering. For deep, actionable intelligence, specialized platforms like DrugPatentWatch are necessary to synthesize this data with litigation and global market information.

- Think in Ripples, Not Drops: A major patent expiration doesn’t just lower the price of one drug. It creates a “ripple effect,” resetting the pricing and formulary dynamics for an entire therapeutic class by creating intense competitive pressure on other branded alternatives.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. If a drug’s main “composition of matter” patent expires, but it has a later-expiring “method of use” patent for a specific disease, can a generic still launch?

Yes, this is a very common scenario and a cornerstone of generic strategy under the Hatch-Waxman Act. A generic company can launch using a “skinny label.” This means they submit their ANDA to the FDA with proposed labeling that deliberately “carves out” or omits the specific indication that is still protected by the method of use patent. The generic is then approved only for the uses that are off-patent. This allows for earlier market entry while avoiding infringement of the remaining use patent. For a hospital system, this means a generic may become available, but its approved uses might be narrower than the brand-name drug’s, requiring careful communication and system-level management to ensure appropriate use.

2. What is the difference between a “biosimilar” and an “interchangeable” biologic, and why does it matter for my hospital’s pharmacy?

This distinction is critically important for pharmacy operations and cost-saving initiatives. A biosimilar is a biologic that is “highly similar” to an already-approved reference product with no clinically meaningful differences. However, it cannot be automatically substituted for the reference product by a pharmacist; a physician must specifically prescribe the biosimilar.44 An

interchangeable biologic has met an even higher regulatory standard, requiring additional studies to show that it can be switched back and forth with the reference product without any loss of efficacy or increase in risk. Once a biologic is designated as interchangeable, a pharmacist can substitute it for the reference product without needing to consult the prescribing physician, subject to state pharmacy laws. This makes interchangeables function much more like traditional small-molecule generics, streamlining the substitution process and accelerating the uptake of the lower-cost agent within a health system.

3. My PBM claims we’re getting “generic savings,” but our overall drug spend is still rising. How can patent intelligence help me hold them accountable?

Patent intelligence empowers you to have a more informed and data-driven conversation with your Pharmacy Benefit Manager (PBM). By tracking patent expirations and the number of generic competitors entering the market, you can understand the true wholesale acquisition cost (WAC) and expected price erosion for a newly genericized drug. This knowledge allows you to scrutinize your PBM contracts for practices like “spread pricing,” where the PBM charges you a higher price for a generic than what it reimburses the pharmacy, pocketing the difference. Armed with data on the actual market price of a generic, you can demand greater transparency, negotiate for 100% pass-through of rebates and savings, and conduct more effective audits to ensure the savings generated by generic competition are actually reaching your health plan and patients.

4. We’re considering a value-based contract for a new, expensive on-patent drug. How can its patent landscape inform our negotiation strategy?

A drug’s patent landscape is a direct indicator of the durability of its monopoly and, therefore, its manufacturer’s long-term pricing power. Before entering a multi-year value-based agreement, a thorough analysis of the drug’s “Exclusivity Stack” is crucial. If the drug is protected by a single, strong composition of matter patent with many years of life remaining, the manufacturer has a very strong negotiating position. However, if its protection relies on a “thicket” of weaker secondary patents that are already facing multiple legal challenges (Paragraph IV filings), its monopoly is far less secure. This intelligence gives you significant leverage. You can argue for shorter contract terms, steeper performance-based rebates, or price protection clauses that trigger if unexpected generic competition emerges sooner than projected.

5. How is Artificial Intelligence (AI) expected to change the drug patent landscape in the coming years?

Artificial intelligence is poised to be a disruptive force in both drug discovery and patent law. On one hand, AI can dramatically accelerate the process of identifying new drug targets and designing novel molecules, potentially shortening the lengthy R&D timeline and reducing costs.103 On the other hand, it creates profound legal challenges. Current patent law in the U.S. and Europe requires an inventor to be a human being.107 As AI systems become more autonomous in generating novel drug candidates, it raises the question of who the true inventor is. Furthermore, if AI tools become standard for “a person skilled in the art,” it could make it much harder for new inventions to be considered “non-obvious,” potentially raising the bar for patentability across the board.104 This is a rapidly evolving area that could fundamentally alter the balance of innovation and competition in the coming decade.

References

- The Role of Patents and Regulatory Exclusivities in Drug Pricing …, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/R46679

- Patents, profits & American medicine: conflicts of interest in the testing & marketing of new drugs, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.amacad.org/publication/daedalus/patents-profits-american-medicine-conflicts-interest-testing-marketing-new-drugs

- Drug Patents: How Pharmaceutical IP Incentivizes Innovation and Affects Pricing, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.als.net/news/drug-patents/

- Drug Patents and Generic Pharmaceutical Drugs – News-Medical.net, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.news-medical.net/health/Drug-Patents-and-Generics.aspx

- www.drugpatentwatch.com, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/how-long-do-drug-patents-last/#:~:text=They%20are%20a%20form%20of,date%20of%20patent%20application%20filing.

- Patent protection strategies – PMC, accessed August 5, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3146086/

- Medical Patents and How New Instruments or Medications Might Be Patented – PMC, accessed August 5, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6139778/

- Pharmaceutical Patent Regulation in the United States – The Actuary Magazine, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.theactuarymagazine.org/pharmaceutical-patent-regulation-in-the-united-states/

- Drug Patent Life: The Complete Guide to Pharmaceutical Patent …, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/how-long-do-drug-patents-last/

- Patents and Drug Pricing: Why Weakening Patent Protection Is Not in the Public’s Best Interest – American Bar Association, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.americanbar.org/groups/intellectual_property_law/resources/landslide/2025-spring/drug-pricing-weakening-patent-protection-not-best-interest/

- The Impact of Patent Expiry on Drug Prices: A Systematic Literature …, accessed August 5, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6132437/

- Managing Patent Portfolios in the Pharmaceutical Industry – PatentPC, accessed August 5, 2025, https://patentpc.com/blog/managing-patent-portfolios-in-the-pharmaceutical-industry

- The Hatch-Waxman Act: A Primer – EveryCRSReport.com, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.everycrsreport.com/reports/R44643.html

- Composition of Matter Patents – (Intro to Pharmacology) – Vocab, Definition, Explanations, accessed August 5, 2025, https://library.fiveable.me/key-terms/introduction-to-pharmacology/composition-of-matter-patents

- History of Patent Medicine – Hagley Museum, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.hagley.org/research/digital-exhibits/history-patent-medicine

- The value of method of use patent claims in protecting your therapeutic assets, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-value-of-method-of-use-patent-claims-in-protecting-your-therapeutic-assets/

- The Patent Cliff Playbook: A Strategic Guide to Formulary …, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-patent-cliff-playbook-a-strategic-guide-to-formulary-management-in-the-age-of-generic-entry/

- Optimizing Your Drug Patent Strategy: A Comprehensive Guide for Pharmaceutical Companies – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/optimizing-your-drug-patent-strategy-a-comprehensive-guide-for-pharmaceutical-companies/

- Composition of matter – Wikipedia, accessed August 5, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Composition_of_matter

- What is the difference between a composition of matter and a method of treatment? – Wysebridge Patent Bar Review, accessed August 5, 2025, https://wysebridge.com/what-is-the-difference-between-a-composition-of-matter-and-a-method-of-treatment

- What are the types of pharmaceutical patents? – Patsnap Synapse, accessed August 5, 2025, https://synapse.patsnap.com/blog/what-are-the-types-of-pharmaceutical-patents

- The Hard Truth About Patent Strategy in a Formulary World – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/formulary-management-and-lcm-patent-strategies-a-complex-interaction/

- Patents and Exclusivity | FDA, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/media/92548/download

- Patents and Exclusivities for Generic Drug Products – FDA, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/cder-conversations/patents-and-exclusivities-generic-drug-products

- Frequently Asked Questions on Patents and Exclusivity | FDA, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/development-approval-process-drugs/frequently-asked-questions-patents-and-exclusivity

- FDA Regulatory Exclusivities Guide – Number Analytics, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.numberanalytics.com/blog/fda-regulatory-exclusivities-guide

- Exclusivity for pharmaceutical products – MedCity, accessed August 5, 2025, https://medcityhq.com/2023/06/27/exclusivity-for-pharmaceutical-products/

- How can I better understand Patents and Exclusivity? – FDA, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/industry/fda-basics-industry/how-can-i-better-understand-patents-and-exclusivity

- What Is The Difference Between Drug Patents And Drug Exclusivity? – Biopharma Institute, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.biopharmainstitute.com/faq/what-is-the-difference-between-drug-patents-and-drug-exclusivity

- Patents vs. Market Exclusivity: Why Does it Take so Long to Bring Generics to Market?, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.raps.org/news-and-articles/news-articles/2016/8/patents-vs-market-exclusivity-why-does-it-take-s

- Generic Drugs – Friends of Cancer Research, accessed August 5, 2025, https://friendsofcancerresearch.org/glossary-term/generic-drugs/

- ELI5: What is the difference between exclusivity and patents for brand name drugs? What is the implication when one runs out vs the other? : r/explainlikeimfive – Reddit, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.reddit.com/r/explainlikeimfive/comments/907e9y/eli5_what_is_the_difference_between_exclusivity/

- FDA Collaboration Initiatives | USPTO – USPTO, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.uspto.gov/initiatives/fda-collaboration

- Distinguishing Patent Protection from Patient Safety – A Role for the FDA | Mintz, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.mintz.com/insights-center/viewpoints/2231/2023-08-21-distinguishing-patent-protection-patient-safety-role-fda

- What are USPTO-FDA collaboration initiatives?, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.uspto.gov/initiatives/fda-collaboration/what-are-uspto-fda-collaboration-initiatives

- Drug Patent and Exclusivity Study available – USPTO, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.uspto.gov/initiatives/fda-collaboration/drug-patent-and-exclusivity-study-available

- Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act – Wikipedia, accessed August 5, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Drug_Price_Competition_and_Patent_Term_Restoration_Act

- Drug Patent Research: Expert Tips for Using the FDA Orange and Purple Books, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/drug-patent-research-expert-tips-for-using-the-fda-orange-and-purple-books/

- 40th Anniversary of the Generic Drug Approval Pathway | FDA, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/cder-conversations/40th-anniversary-generic-drug-approval-pathway

- The Hatch-Waxman Act: A Quarter Century Later – UM Carey Law, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www2.law.umaryland.edu/marshall/crsreports/crsdocuments/R41114_03132013.pdf

- What is Hatch-Waxman? – PhRMA, accessed August 5, 2025, https://phrma.org/resources/what-is-hatch-waxman

- Hatch-Waxman Litigation 101: The Orange Book and the Paragraph IV Notice Letter, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.dlapiper.com/insights/publications/2020/06/ipt-news-q2-2020/hatch-waxman-litigation-101

- Pharmaceutical Patent Disputes: Biosimilar Entry Under the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA) – Congress.gov, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.congress.gov/crs_external_products/IF/PDF/IF13029/IF13029.1.pdf

- Biologics, Biosimilars and Patents: – I-MAK, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.i-mak.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Biologics-Biosimilars-Guide_IMAK.pdf

- Biosimilars and the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA), accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.venable.com/-/media/files/publications/2018/06/biosimilars-and-the-bpcia.pdf?rev=5ca3638b6bc540acbdc0bff30b43b9a8&hash=0815F00D8BDDC2F873F5A23FF219A4FD

- Biosimilars | Health Affairs, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hpb20131010.6409/

- Commemorating the 15th Anniversary of the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/cder-conversations/commemorating-15th-anniversary-biologics-price-competition-and-innovation-act

- “Purple Book” Patent Listing Under Biological Product Patent Transparency Act: What Is Required, and What to Expect? – Kslaw.com, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.kslaw.com/attachments/000/009/011/original/9-1-21_Intellectual_Property___Technology_Law_Journal.pdf?1629994170

- Patent Listing in FDA’s Orange Book – Congress.gov, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/IF12644

- FAQs – FDA Purple Book, accessed August 5, 2025, https://purplebooksearch.fda.gov/faqs

- Purple Book: Lists of Licensed Biological Products with Reference Product Exclusivity and Biosimilarity or Interchangeability Evaluations | FDA, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/therapeutic-biologics-applications-bla/purple-book-lists-licensed-biological-products-reference-product-exclusivity-and-biosimilarity-or

- How Drug Life-Cycle Management Patent Strategies May Impact Formulary Management, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.ajmc.com/view/a636-article

- Market Exclusivity and U.S. Prescription Drugs – Commonwealth Fund, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/journal-article/2017/sep/determinants-market-exclusivity-prescription-drugs-united

- The Connection Between Patents and High Drug Prices – Politico, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.politico.com/sponsored/2024/12/the-connection-between-patents-and-high-drug-prices/

- How drugmakers exploit the patent system to delay competition and inflate prices | Evernorth, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.evernorth.com/articles/how-drugmakers-exploit-patent-system-delay-competition-and-inflate-prices

- Strategies That Delay Market Entry of Generic Drugs – Commonwealth Fund, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/journal-article/2017/sep/strategies-delay-market-entry-generic-drugs

- The End of Exclusivity: Navigating the Drug Patent Cliff for Competitive Advantage – DrugPatentWatch – Transform Data into Market Domination, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-impact-of-drug-patent-expiration-financial-implications-lifecycle-strategies-and-market-transformations/

- Patent cliff and strategic switch: exploring strategic design possibilities in the pharmaceutical industry – PMC, accessed August 5, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4899342/

- What is a patent cliff, and how does it impact companies? – Patsnap Synapse, accessed August 5, 2025, https://synapse.patsnap.com/article/what-is-a-patent-cliff-and-how-does-it-impact-companies

- Patent Expiration and Pharmaceutical Prices | NBER, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.nber.org/digest/sep14/patent-expiration-and-pharmaceutical-prices

- Strategic Patenting by Pharmaceutical Companies – Should Competition Law Intervene? – PMC, accessed August 5, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7592140/

- Drug Competition Series – Analysis of New Generic Markets Effect of Market Entry on Generic Drug Prices – HHS ASPE, accessed August 5, 2025, https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/510e964dc7b7f00763a7f8a1dbc5ae7b/aspe-ib-generic-drugs-competition.pdf