Executive Summary

In the high-stakes pharmaceutical industry, where intellectual property is the primary driver of value, the ability to conduct effective patent research is not a mere technical skill but a critical strategic function. Google Patents has emerged as a powerful, accessible, and comprehensive platform that democratizes access to global patent information. This report provides an expert-level guide for pharmaceutical professionals—including R&D scientists, competitive intelligence analysts, and business development managers—on leveraging this tool for strategic advantage.

The analysis begins by establishing the profound economic context of pharmaceutical IP, where the immense cost of R&D and the existential threat of the “patent cliff” have driven the evolution of sophisticated lifecycle management strategies like “evergreening” and the creation of “patent thickets.” Understanding this landscape is essential for interpreting the patent data uncovered through any search tool.

The report then deconstructs the Google Patents platform, tracing its evolution from a simple repository to an interconnected ecosystem of patent, academic, and legal data. It provides a detailed, practical tutorial on mastering its search functionalities, from foundational keyword strategies to advanced Boolean, proximity, and field-specific operators. Crucially, it emphasizes the use of the Cooperative Patent Classification (CPC) system as the hallmark of a professional, systematic search.

Strategic applications are explored in depth, demonstrating how to use the platform for competitive intelligence, deconstructing competitor lifecycle management strategies, and conducting preliminary Freedom-to-Operate (FTO) analyses. Case studies of two blockbuster drugs, Lipitor (atorvastatin) and Humira (adalimumab), are presented to illustrate the historical evolution of patent strategy from a defensive posture to an aggressive commercial fortress-building exercise.

However, the report concludes with a critical assessment of the platform’s inherent risks. While invaluable for preliminary research, Google Patents suffers from limitations in data completeness, update frequency, and the absence of specialized tools essential for pharmaceutical research, such as chemical structure searching. Furthermore, its use creates a discoverable legal record that can be leveraged by opposing counsel in litigation to argue for willful infringement.

The primary recommendation is to adopt a tiered approach to patent research. Google Patents should be the tool of choice for broad landscape analysis and initial competitive monitoring. However, for any high-stakes commercial or legal decision, its findings must be cross-verified with official patent office databases and, ultimately, supplemented by professional-grade subscription services and the indispensable counsel of a qualified patent attorney. Used with strategic wisdom and disciplined caution, Google Patents is an invaluable asset; used naively, it can become a significant liability.

Part I: The Strategic Landscape of Pharmaceutical Intellectual Property

To effectively utilize any patent research tool, one must first comprehend the environment in which it operates. The pharmaceutical industry’s relationship with intellectual property is unique in its intensity and economic significance. Patent strategy is not a secondary legal function but the central pillar supporting the entire business model, dictating R&D investment, commercial strategy, and corporate longevity.

1.1 The Economic Imperative: Why Patents are the Lifeblood of Pharma Innovation

The foundation of the pharmaceutical industry rests on a societal agreement known as the “patent bargain”: in exchange for the public disclosure of a new invention, society grants the inventor a temporary monopoly, typically for 20 years from the patent’s filing date.1 This period of exclusivity is the engine of innovation. It provides the necessary incentive for companies to undertake the monumentally expensive, time-consuming, and high-risk process of drug discovery and development.

The financial stakes are immense. Bringing a single new medication to market is estimated to cost as much as $2.6 billion, a figure that accounts for the vast number of failed candidates for every one that succeeds.4 With global prescription drug revenues exceeding $1.5 trillion annually, the ability to protect a successful product from competition is paramount.6 Patents are the “cornerstone” of this protection, allowing companies to recoup their R&D investments and fund future research.1 Without this protection, the low cost of replicating a drug would allow competitors to enter the market and drastically undercut prices, decimating the innovator’s ability to recover its initial outlay.

Furthermore, a robust patent portfolio is a critical asset for attracting capital. For startups and established companies alike, patents signal a protected market opportunity and de-risk the venture for investors, making them essential for securing the financing required to navigate the long development pathway.3

1.2 The 20-Year Term vs. Effective Market Exclusivity: The Ticking Clock

A critical factor shaping all pharmaceutical patent strategy is the significant disparity between the statutory 20-year patent term and the actual period of market exclusivity a drug enjoys. The journey from initial discovery and patent filing to market launch is a lengthy one, consuming an average of 10 to 15 years for clinical trials and rigorous regulatory review.8

This means that by the time a drug is finally approved and available to patients, a substantial portion of its 20-year patent life has already expired. The “effective patent life”—the actual time a drug is on the market with no generic competition—is often reduced to a mere 7 to 10 years.3 This compressed timeline for recouping a multi-billion-dollar investment creates immense pressure on pharmaceutical companies and is the primary driver for the development of sophisticated strategies aimed at maximizing a drug’s commercial lifespan.

1.3 Navigating the “Patent Cliff”: The Existential Threat of Exclusivity Loss

The end of a drug’s market exclusivity period is known as the “patent cliff,” a term that aptly describes the subsequent precipitous drop in sales.9 Once the primary patents on a blockbuster drug expire, generic manufacturers can enter the market, often leading to an 80% or greater reduction in the branded drug’s market share within the first year.10

The scale of this threat is staggering. By 2030, an estimated $300 billion in annual pharmaceutical revenue is at risk from patent expirations, affecting 190 drugs, including 69 “blockbusters” (drugs with over $1 billion in annual sales).10 The patent cliff is not merely a financial challenge; it is an existential threat that can reshape a company’s future. It is this threat that has transformed pharmaceutical IP from a simple act of protecting an invention into a complex, proactive strategy of defending a revenue stream.

1.4 Anatomy of a Modern Patent Strategy: “Patent Thickets” and “Evergreening”

In response to the immense financial pressure of the patent cliff, pharmaceutical companies have developed sophisticated lifecycle management (LCM) strategies. These strategies have evolved from a defensive act of protecting a single core invention to an offensive commercial strategy of building a fortress around a product’s market franchise. Two central tactics define this modern approach: “evergreening” and the creation of “patent thickets.”

Evergreening is a strategy to extend a drug’s monopoly by obtaining new, secondary patents on minor modifications or new discoveries related to the original drug.2 These secondary patents do not cover the original active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) but instead protect incremental innovations such as:

- New formulations (e.g., an extended-release version)

- New delivery methods (e.g., a pre-filled syringe instead of a vial)

- New methods of use (i.e., discovering the drug is effective for a different disease)

- New dosage forms or strengths.8

This practice is widespread. Studies have shown that 78% of new patents listed in the FDA’s records are for existing drugs, not new chemical entities.15 For the top-selling drugs, a staggering 72% of patent applications are filed

after the drug has already received FDA approval, demonstrating a clear strategic intent to prolong market exclusivity.6

The accumulation of these secondary patents around a single product creates what is known as a patent thicket—a dense, overlapping web of intellectual property rights.8 The purpose of a patent thicket is to create a formidable “litigation barrier” for potential generic or biosimilar competitors. Even if some of the individual secondary patents are weak, the sheer number and complexity of the thicket make it prohibitively expensive and time-consuming for a competitor to challenge them all in court, thereby delaying or deterring market entry.8 This systemic response—driven by the high cost of R&D, the short effective patent life, and the threat of the patent cliff—is the crucial context for interpreting the patent portfolios that are uncovered using tools like Google Patents.

Part II: Deconstructing Google Patents: A Digital Library for Global Innovation

Google Patents has evolved from a simple search engine into a multifaceted platform that integrates patent, academic, and legal data from around the globe. Understanding its architecture, features, and data structure is the first step toward leveraging it effectively for pharmaceutical research.

2.1 Platform Origins and Evolution: From USPTO Index to Global Database

Launched on December 14, 2006, Google Patents began as a search engine that indexed the full text of patents and patent applications from the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO).17 Its initial technology was based on the same platform as Google Books, allowing for easy page scrolling and zooming of patent documents.17

Over the following decade, Google systematically expanded its coverage to become a truly global database. Key milestones include:

- 2012: Integration of patents from the European Patent Office (EPO) and the launch of the “Prior Art Finder” tool.17

- 2013: A major expansion to include documents from the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), the German Patent Office (DPMA), the Canadian Intellectual Property Office (CIPO), and China’s National Intellectual Property Administration (CNIPA).17

- 2015: A significant user interface overhaul and deeper integration with Google Scholar, which began machine-classifying documents with Cooperative Patent Classification (CPC) codes.17

- 2018: The addition of global litigation information through a partnership with Darts-ip, a global patent litigation database.17

To make this vast collection universally accessible, Google employed Optical Character Recognition (OCR) to convert millions of older, image-based patents into searchable text and used Google Translate to make all non-English patents searchable via their English translations.17

2.2 Core Features and Functionality: Interface, Data Coverage, and Integrated Tools

The power of Google Patents lies not just in its breadth but in its integration of diverse data sources and user-friendly features.

- Accessible Interface: The platform’s interface is intentionally designed to be familiar to users of the main Google search engine, making it approachable for those without specialized patent search training.18

- Integrated Non-Patent Literature: A key advantage is the seamless integration of documents from Google Scholar and Google Books. When searching, users can opt to include this non-patent literature, which is essential for conducting comprehensive prior art searches and understanding the scientific context of an invention.17

- Litigation Data: The platform indicates whether a patent or any member of its family has a litigation history anywhere in the world, providing a direct link to the Darts-ip database for more detailed case information. This feature connects the technical patent document to its real-world commercial and legal enforcement.17

- Systematic Classification: Google Patents has machine-classified its indexed documents using Cooperative Patent Classification (CPC) codes. This allows for more systematic and language-independent searching and helps cluster search results by technical area, a significant improvement over simple keyword searching.17

2.3 Understanding the Data: Patent Families, Citations, and Legal Events

Each patent page on Google Patents is a rich source of interconnected information. A sophisticated user must look beyond the abstract and drawings to understand the full context of the invention.

- Patent Families: A patent family is the group of patents and applications filed in different countries that relate to the same invention, typically sharing a common priority application.20 Google Patents displays this family information, allowing a researcher to quickly assess the global scope of a competitor’s patent protection strategy.21

- Citations: The platform displays both backward and forward citations, which are crucial for analysis.

- Backward Citations (“Patent citations”): These are the earlier patents and scientific articles that the current patent cites as prior art. They reveal the technological foundations upon which the invention was built.19

- Forward Citations (“Cited by”): These are later patents that cite the current document. This is a powerful metric for assessing a patent’s influence and impact; a patent that is cited many times is likely a foundational piece of technology.19

- Legal Events: At the bottom of each patent page, a timeline of legal events is often provided. This can include information on when the patent was granted, reassignment of ownership, and payment of maintenance fees, offering clues to the patent’s current legal status.20

The platform should not be viewed as a static archive but as a dynamic ecosystem. The true value is unlocked by tracing the connections it reveals: from a patent to the scientific literature it cites (via Google Scholar), to the subsequent inventions it influenced (via forward citations), and to its commercial enforcement (via litigation data). This ecosystem approach allows a user to build a 360-degree view of an invention’s scientific context, technological legacy, and strategic importance.

Part III: Mastering the Search: A Practical Guide for Pharmaceutical Researchers

Effective patent searching is an iterative process that combines broad discovery with precise refinement. For pharmaceutical research, this requires a nuanced understanding of both the search tool’s syntax and the industry’s specific terminology. This section provides a practical, step-by-step guide to mastering Google Patents for drug-related inquiries.

3.1 Foundational Search Techniques: Crafting Effective Keyword Strategies

The starting point for most searches is a well-crafted set of keywords. In the pharmaceutical context, this goes beyond simply using a drug’s brand name. A comprehensive strategy should cast a wide net to capture documents that may use different terminology to describe the same technology.19

A robust keyword list for a drug patent search should include:

- Drug Names: The International Nonproprietary Name (INN) (e.g., “adalimumab”), brand names (e.g., “Humira”), and any known chemical names or code names (e.g., “D2E7”).19

- Mechanism of Action: Terms describing how the drug works (e.g., “TNF alpha inhibitor,” “tumor necrosis factor”).19

- Chemical Class: The broader family of compounds the drug belongs to (e.g., “monoclonal antibody”).19

- Therapeutic Application: The diseases or conditions the drug treats (e.g., “rheumatoid arthritis,” “Crohn’s disease”).19

For example, a foundational search for patents related to the diabetes drug class SGLT2 inhibitors should include terms like “sodium-glucose cotransporter inhibitors”, “gliflozins”, specific drug names like “dapagliflozin”, and applications like “type 2 diabetes treatment”.19

To refine these searches, use basic operators:

- Exact Phrases: Enclose terms in quotation marks (” “) to search for the exact phrase, which is crucial for multi-word technical terms like “sustained release formulation”.25

- Exclusion: Use a minus sign (-) before a word to exclude patents containing that term. For example, a search for a therapeutic needle might use needle -sewing to remove irrelevant results.25

3.2 Advanced Search Operators: A Deep Dive into Boolean, Proximity, and Field-Specific Queries

To move beyond basic searches and conduct professional-level queries, one must master the advanced search syntax supported by Google Patents.

Boolean Operators

These operators (AND, OR, NOT) allow for the construction of complex logical queries. While AND is the default operator between terms, explicitly using them provides clarity and control.19

- OR: Broadens a search by finding documents that contain either term. It is essential for searching synonyms.

- Example: (metformin OR biguanide) will find patents mentioning either the specific drug or its chemical class.

- AND: Narrows a search by requiring that all terms be present in the document.

- Example: (sitagliptin AND “Januvia”)

- NOT or -: Excludes documents containing a specific term.

- Example: antibody NOT murine

Proximity Operators

These operators are exceptionally powerful for finding relationships between concepts, as they search for terms that appear close to each other within the document. This is more precise than a simple AND search, which could find the terms pages apart.25

- NEAR/x or /xw: Finds terms within ‘x’ words of each other, in any order.

- Example: (adalimumab NEAR/15 formulation) finds documents where “adalimumab” and “formulation” are within 15 words of each other.

- ADJ/x or +xw: Finds terms within ‘x’ words of each other, in the specified order.

- Example: (“extended release” ADJ/5 coating) finds documents where “extended release” is followed by “coating” within 5 words.

- WITH and SAME: Broader proximity operators, equivalent to NEAR/20 and NEAR/200 respectively.27

Field-Specific Searches

This technique allows you to target your search to a specific section of the patent document, dramatically increasing relevance.19

- TI=() or title:(): Searches only within the patent title.

- AB=() or abstract:(): Searches only within the abstract.

- CL=() or claims:(): Searches only within the legally critical claims section.

- assignee:(): Searches for patents owned by a specific company or entity.

- Example: assignee:(“AbbVie Inc”)

- inventor:(): Searches for patents by a specific inventor.

- Example: inventor:(“Roth, Bruce”)

By combining these operators, a researcher can construct highly specific and powerful queries. For instance, to find patents for extended-release metformin formulations from specific companies, one could use: assignee:(Merck OR Novartis) AND CL:((metformin OR biguanide) AND (“extended release” OR “sustained release”)).19

3.3 Systematic Searching with Cooperative Patent Classification (CPC) Codes

While keyword searching is essential, it is limited by variations in terminology and language. The most systematic and comprehensive search method relies on the Cooperative Patent Classification (CPC) system. The CPC is a detailed, hierarchical classification scheme jointly managed by the EPO and USPTO that organizes inventions by their technical subject matter, independent of the language used in the document.28

For pharmaceutical research, several CPC classes are of primary importance:

| Table 2: Key CPC Codes for Pharmaceutical Research | ||

| CPC Code | Description | Relevance to Pharma Research |

| A61K | Preparations for medical, dental, or toiletry purposes | The broadest and most important class for pharmaceuticals. Covers drug compositions, formulations, and cosmetics.19 |

| A61K 9/00 | Medicinal preparations characterised by special physical form | Covers specific dosage forms like tablets (A61K 9/20), injectable compositions (A61K 9/0019), or aerosols.32 |

| A61K 31/00 | Medicinal preparations containing organic active ingredients | Classifies drugs based on their chemical structure. Essential for small molecule drug searches.31 |

| A61K 39/00 | Medicinal preparations containing antigens or antibodies | Crucial for vaccines and antibody-based therapies (biologics).33 |

| C07K | Peptides | Covers peptides, proteins, and immunoglobulins (antibodies). This is the fundamental class for researching biologics.34 |

| C07K 16/00 | Immunoglobulins, e.g., monoclonal antibodies | A key subclass within C07K specifically for antibody technologies.36 |

| A61P | Specific therapeutic activity of chemical compounds | Classifies a drug based on its intended use or the disease it treats. This is an indexing code used in conjunction with others.37 |

| A61P 35/00 | Antineoplastic agents (anticancer drugs) | Used to find all drugs intended for cancer treatment, regardless of their chemical structure or mechanism.39 |

| A61P 3/10 | Drugs for hyperglycaemia, e.g., antidiabetics | Used to find drugs for treating diabetes.39 |

| C12N 15/09 | Recombinant DNA or RNA | Covers genetic engineering technologies, essential for the production of biologics and for gene therapies.33 |

The optimal search workflow integrates both keyword and classification methods:

- Discover: Start with a targeted keyword search to find a few highly relevant patents.

- Identify: Examine these patents to identify the primary CPC codes assigned to them. Google Patents conveniently lists these on each patent’s page.17

- Expand: Conduct new searches using these CPC codes (e.g., cpc:(A61K31/40)) to find all patents in that technical area, capturing documents that may have used different keywords or are in different languages.40

3.4 Step-by-Step Search Protocols for Specific Pharmaceutical Inquiries

The following protocols provide a structured approach to common research tasks.

Protocol 1: Preliminary Novelty/Prior Art Search

- Objective: To determine if a new drug concept has been previously disclosed.

- Steps:

- Brainstorm a comprehensive list of keywords for the drug’s structure, function, and use.

- Conduct initial keyword searches to find closely related patents and identify relevant CPC codes.

- Construct a main search string combining keywords with OR and CPC codes. Example: (cpc:C07K16/2878 OR “PD-1 inhibitor”) AND (cpc:A61P35/00 OR cancer OR tumor)

- Filter results by date using the advanced search menu or the before:priority:YYYYMMDD operator to exclude any art published after your invention date.

- Check the “Include non-patent literature” box to search Google Scholar for academic papers.

- Review the most relevant results and perform citation analysis (backward and forward) to find more related art.

Protocol 2: Competitor Monitoring

- Objective: To track the R&D activities of a specific competitor.

- Steps:

- Identify the correct legal name of the competitor company. Be aware of subsidiaries and parent companies.

- Use the assignee:() operator with the company’s name. Example: assignee:(“Merck Sharp & Dohme”)

- Combine the assignee search with keywords or CPC codes for a specific technology area of interest. Example: assignee:(“Gilead Sciences”) AND (cpc:A61P31/18 OR HIV)

- Filter results by publication or filing date to see only recent activity.

- Download the results as a CSV file for further analysis and tracking over time.17

| Table 3: Google Patents Advanced Search Operator Cheat Sheet | |||

| Operator Type | Operator Syntax | Function | Pharmaceutical Example |

| Boolean | A OR B | Finds documents containing either A or B. | (aspirin OR “acetylsalicylic acid”) |

| A AND B | Finds documents containing both A and B. | (atorvastatin AND formulation) | |

| A NOT B or A -B | Finds documents containing A but not B. | vaccine -adjuvant | |

| Field | assignee:(A) | Searches for patents owned by assignee A. | assignee:(“Pfizer Inc.”) |

| inventor:(A) | Searches for patents by inventor A. | inventor:(Kariko, Katalin) | |

| cpc:(A) | Searches for patents in classification A. | cpc:(A61P35/00) | |

| CL:(A) | Searches for term A only in the claims. | CL:(“crystalline form”) | |

| Proximity | A NEAR/x B | Finds A and B within x words, any order. | (sildenafil NEAR/10 “pulmonary hypertension”) |

| A ADJ/x B | Finds A and B within x words, in that order. | (“monoclonal antibody” ADJ/3 “humanized”) | |

| Wildcards | * | Zero or more characters (stemming). | immuno* (finds immune, immunology, etc.) |

| ? | Zero or one character. | analy?e (finds analyze and analyse) | |

| Phrases | “A B” | Finds the exact phrase “A B”. | “antibody-drug conjugate” |

Part IV: Strategic Applications in Drug Development and Commercialization

Mastering the technical aspects of searching is only the first step. The true value of Google Patents is realized when these search capabilities are applied to answer critical strategic questions that drive business decisions throughout the drug lifecycle.

4.1 Competitive Intelligence

Patent filings are a lagging indicator of invention but a leading indicator of commercial strategy. Because patent applications are typically published 18 months after their initial filing, they create a valuable intelligence window, offering a glimpse into a competitor’s strategic intentions years before a product reaches the market.12

- Mapping R&D Pipelines: By systematically tracking the patent filings of competitors using assignee: searches filtered by recent dates, a company can effectively map their R&D pipeline. A sudden increase in filings within a specific CPC class or related to a particular biological target can signal a new strategic focus. For example, observing a competitor known for small molecules suddenly filing numerous patents in C07K 16/00 (Immunoglobulins) is a strong indicator of their entry into the biologics space. This serves as a powerful early warning system, allowing a company to adjust its own R&D priorities in response.41

- Identifying “White Space” and In-Licensing Opportunities: A patent landscape analysis involves mapping all the patents within a given technological field. By combining broad CPC codes (e.g., A61P 25/28 for drugs for dementia) with targeted keywords, analysts can visualize the density of patenting activity. Areas with few patents represent “white space”—potential opportunities for innovation with less competition.12 Conversely, this analysis can identify universities, research institutions, or smaller biotech companies that hold foundational patents in an area of interest, flagging them as potential partners for in-licensing or acquisition.42

- Monitoring Key Players: Setting up alerts or routine searches for key inventors or assignees allows a company to stay abreast of the latest developments from industry leaders and academic pioneers. This can help identify emerging technologies, potential collaborators, or future competitive threats.44

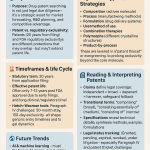

4.2 Drug Lifecycle Management (LCM)

For a company’s own products and those of its competitors, patent data provides a roadmap for lifecycle management and anticipating the patent cliff.

- Analyzing Portfolios to Predict the Patent Cliff: A deep analysis of a competitor’s patent portfolio for a blockbuster drug is essential for strategic planning. By using Google Patents to identify the core “composition of matter” patent and all subsequent secondary patents (formulation, method of use, etc.), an analyst can map out the expiration dates for each. This reveals the true, layered expiration of market exclusivity, not just the date the primary patent expires. This intelligence is crucial for predicting when generic or biosimilar competition will realistically be able to enter the market and for timing the launch of a competing product.4

- Deconstructing Evergreening Strategies: The type of secondary patents being filed is as important as their number. By analyzing the claims of a competitor’s recent filings, one can decode their specific LCM strategy. A flurry of patents with claims directed to new crystalline forms or extended-release formulations indicates a focus on product improvements. A series of patents for new therapeutic indications (new A61P codes) reveals a market expansion strategy. This allows a company to anticipate a competitor’s next move long before it is announced in a press release or to a sales force.12

4.3 Preliminary Freedom-to-Operate (FTO) Analysis

Before investing significant resources into developing a new drug or technology, a company must assess whether it has “freedom to operate”—that is, whether its planned commercial activities would infringe on the valid, in-force patent rights of a third party.46 While a formal FTO opinion requires a qualified patent attorney, Google Patents is an invaluable tool for conducting a preliminary risk assessment.

A preliminary FTO search follows a structured process:

- Deconstruct the Invention: Break down the product or process into its essential components. For a new drug, this includes the Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API), its specific formulation (excipients, delivery system), the method of manufacture, and the intended method of use (therapeutic indication).46

- Conduct Targeted Searches: Perform separate, focused searches on Google Patents for each component. The search should be limited to the specific jurisdictions (countries) where the product will be manufactured or sold and should be filtered to show only granted, in-force patents.46

- Analyze the Claims: This is the most critical step. Infringement is determined not by what is written in the abstract or description, but by the legal scope defined in the claims section.46 Each element of the product must be compared against the elements listed in the independent claims of potentially relevant patents.

- Interpret Claim Language: Pay close attention to transitional phrases. A claim that “comprises” elements A, B, and C is open-ended and is infringed by a product that contains A, B, C, and D. A claim that “consists of” elements A, B, and C is closed and is not infringed by a product containing A, B, C, and D.8

Crucial Caveat: This preliminary search is a screening tool for identifying obvious risks. It is not a substitute for a formal, legally binding FTO opinion from a patent attorney. The complexity of claim interpretation and the potential for undiscovered pending applications make professional legal analysis non-negotiable before any major commercial decision.46

Part V: Case Studies in Blockbuster Patent Strategy

The theoretical concepts of patent strategy are best understood through real-world examples. The contrasting patent histories of two of the most commercially successful drugs in history—Lipitor and Humira—illustrate a fundamental evolution in pharmaceutical IP strategy over the past two decades. The lessons learned from Lipitor’s patent cliff directly informed the “fortress” strategy employed for Humira.

5.1 Humira (Adalimumab): Anatomy of a Fortress

AbbVie’s strategy for Humira (adalimumab) is the modern archetype of the “patent thicket.” It represents a shift from merely protecting an invention to aggressively defending a multi-billion-dollar market franchise through a dense and overlapping web of intellectual property.

- The Thicket by the Numbers: Humira was first approved by the FDA in 2002.50 Over the course of its market life, AbbVie filed an astonishing 257 patent applications, resulting in 130 granted patents in the U.S. alone.51 Critically, between 90% and 94% of these patent applications were filed

after the drug was already on the market.51 This systematic, post-approval filing campaign was designed to create a patent monopoly that would last far beyond the expiration of the original patents. - Types of Secondary Patents: The Humira portfolio is a masterclass in layered protection. The patents cover not just the adalimumab antibody itself, but a vast array of secondary characteristics, including:

- Formulations: Patents on specific formulations, such as the citrate-free version (which reduces injection pain) and high-concentration versions, were key to maintaining market share.53

- Methods of Use: As Humira was approved for new indications—from rheumatoid arthritis to psoriasis to Crohn’s disease—AbbVie secured new method-of-use patents for each one.50

- Manufacturing Processes: Patents were also filed on various aspects of the manufacturing process, adding another layer of complexity for potential biosimilar competitors.8

- The Strategic Outcome: The result was a nearly impenetrable fortress. The primary U.S. patent on the adalimumab molecule expired in 2016, but the patent thicket successfully delayed the launch of any biosimilar competitors in the lucrative U.S. market until 2023.8 This strategy protected the world’s best-selling drug, which generated cumulative sales of over $200 billion and allowed AbbVie to capture an estimated $167 billion in U.S. sales after the primary patent’s expiry.6 The litigation barrier was so formidable that AbbVie asserted over 60 patents against a single biosimilar applicant, Alvotech.57

A researcher can visualize the construction of this fortress on Google Patents with a search like assignee:(“AbbVie Inc” OR “Abbott Laboratories”) AND (adalimumab OR Humira). By sorting the results by filing date, the massive wave of post-2002 patent filings becomes immediately apparent.

5.2 Lipitor (Atorvastatin): A Study in Lifecycle Management and Market Defense

The story of Pfizer’s Lipitor (atorvastatin) is both a tale of immense commercial success and a cautionary tale that redefined the industry’s approach to patent cliffs.

- The “Me-Too” Blockbuster: Lipitor was the fifth statin (a class of cholesterol-lowering drugs) to enter the market upon its FDA approval in 1997.58 Despite being a “me-too” drug, it became the best-selling drug in the world, with cumulative sales exceeding $125 billion over 14.5 years, due to its superior cholesterol-lowering efficacy and an aggressive marketing campaign.58

- The Patent Portfolio: The patent strategy for Lipitor, developed by its original inventor Warner-Lambert (later acquired by Pfizer), was more traditional than Humira’s.60 It was anchored by a strong core “composition of matter” patent on the atorvastatin molecule, which was patented in 1986.61 This was supported by a smaller number of supplementary patents covering different formulations and potential combination therapies (e.g., atorvastatin combined with aspirin).60 While Pfizer actively defended these patents, the portfolio was not the dense, overlapping thicket seen later with Humira.60

- The Patent Cliff in Action: The main U.S. patent for Lipitor expired on November 30, 2011.61 The result was immediate and dramatic. Generic versions of atorvastatin entered the market, and Lipitor’s annual revenue collapsed. This event became the canonical example of the “patent cliff,” serving as a stark warning to the entire industry about the financial devastation that follows the loss of exclusivity for a blockbuster product.59

Using Google Patents to search assignee:(Pfizer OR “Warner-Lambert”) AND (atorvastatin OR Lipitor) reveals a portfolio with a clear anchor in the mid-1980s composition patent, followed by a more modest number of secondary filings. The contrast with the Humira portfolio is a clear illustration of a strategic paradigm shift. The hard lesson learned from Lipitor’s fall directly spurred the development of the hyper-aggressive, defense-in-depth patent thicket strategy that was later perfected for Humira and other modern biologics.

| Table 4: Patent Portfolio Summary – Humira vs. Lipitor | ||

| Metric | Lipitor (Atorvastatin) | Humira (Adalimumab) |

| Primary Patent Filing Year | 1986 61 | c. 1993-1994 8 |

| FDA Approval Year | 1996/1997 58 | 2002 50 |

| Primary U.S. Patent Expiration | 2011 61 | 2016 57 |

| Approx. Granted U.S. Patents | ~49 (mean for blockbusters of its era) 63 | 130+ 51 |

| % of Patents Filed Post-Approval | Lower (strategy less developed) | 90-94% 51 |

| Key LCM Strategies | Formulation patents, combination therapy patents. | Dense “patent thicket” covering formulations, manufacturing, dozens of methods of use. |

| Outcome at Primary Patent Expiry | Immediate and sharp revenue decline (“patent cliff”).59 | U.S. biosimilar entry delayed by ~7 years through litigation on the patent thicket.8 |

Part VI: A Critical Assessment: The Promises and Perils of Google Patents

Google Patents has fundamentally changed the intellectual property landscape by providing unprecedented access to a global library of innovation. However, for the pharmaceutical professional, its use requires a disciplined and critical approach. The platform’s undeniable strengths in accessibility are counterbalanced by significant risks in reliability and legal implications.

6.1 The Professional’s Dilemma: Accessibility vs. Reliability

The primary value proposition of Google Patents is its combination of comprehensive global coverage, a user-friendly interface, and cost-free access.23 It is an outstanding tool for initial exploration, academic research, and gaining a broad understanding of a technology landscape.

However, for high-stakes professional applications—such as making multi-million-dollar investment decisions or assessing legal infringement risk—this accessibility can create an illusion of comprehensiveness. The core dilemma for the professional user is balancing the platform’s convenience against its inherent limitations in data integrity and analytical depth.19 Relying on it as the sole or final source of information for critical decisions is a significant strategic error.

6.2 Key Limitations: Data Integrity, Update Frequency, and Lack of Specialized Tools

Despite its vast index, Google Patents has several critical limitations that are particularly relevant to pharmaceutical research.

- Data Gaps and Latency: Google itself acknowledges that it “cannot guarantee complete coverage”.67 The data can be incomplete or outdated compared to the official records of patent offices or the curated databases of paid subscription services. In the fast-moving pharmaceutical industry, a delay of even a few months in data updates can mean missing a critical new filing from a competitor.66

- Lack of Specialized Search Tools: Pharmaceutical and biotechnology patent research often requires highly specialized search capabilities that Google Patents lacks. The most significant omissions are chemical structure searching and biosequence (e.g., DNA, protein) searching. For a chemist or biologist, the ability to search for a specific molecular structure or amino acid sequence is often more important than searching for keywords. This functionality is a standard feature in professional-grade databases but is absent from Google Patents.66

- Inadequate Support and Analytics: The platform does not offer expert support services to help users construct complex searches or interpret results.66 It also lacks the sophisticated analytical and visualization tools found in paid platforms that can help users quickly identify trends, map competitive landscapes, and track patent portfolios.65

- Incomplete Data Sets: While patent family and citation data are provided, they may not be as complete or reliable as those found in specialized databases that invest heavily in data curation and verification.19

6.3 The Legal Minefield: Willful Infringement and the Limits of a “Free” Tool

Perhaps the most significant and least understood risk of using Google Patents in a corporate setting is the legal trail it creates. In U.S. patent law, the doctrine of “willful infringement” allows a court to award up to treble (triple) damages if it is found that a company knowingly infringed a patent.46

A company’s search history, including searches conducted on public platforms like Google Patents, can be discoverable during litigation. If a company’s researchers are found to have viewed a competitor’s patent on Google Patents and the company proceeded to launch an infringing product, opposing counsel can use this search record as powerful evidence of “willful blindness” or actual knowledge of the patent. This can transform what would have been a standard infringement case into a much more costly one. This risk turns a seemingly innocuous research tool into a potential source of significant legal liability.19

6.4 Best Practices and Recommendations: Integrating Google Patents into a Professional Workflow

Given its strengths and weaknesses, Google Patents should not be abandoned but rather integrated intelligently into a disciplined, multi-tiered research workflow.

- Tier 1: Initial Exploration and Broad Monitoring. Use Google Patents for its strengths: conducting broad landscape analyses, initial prior art searches, tracking general competitor activity, and academic research. Its speed and ease of use are ideal for these preliminary tasks.

- Tier 2: Verification and Deeper Analysis. For any findings of potential importance, cross-verify the information using official, free databases like the USPTO’s Patent Public Search and the EPO’s Espacenet. These platforms provide the most accurate and up-to-date information on legal status and file histories for their respective jurisdictions.

- Tier 3: Critical, High-Stakes Decisions. For business-critical activities such as formal Freedom-to-Operate (FTO) opinions, validity challenges, due diligence for mergers and acquisitions, or final investment decisions, it is imperative to use professional-grade, subscription-based databases. Services like DrugPatentWatch, CAS STNext, or Clarivate’s Derwent Innovation offer curated data, specialized search tools (e.g., structure searching), and robust analytics. Most importantly, these activities must be conducted under the guidance of a qualified patent attorney who can provide a formal legal opinion, which can help shield the company from claims of willful infringement.

The greatest risk of Google Patents is not its known limitations, but the false sense of security its user-friendly interface can provide. It empowers non-experts to access complex legal documents, which can lead to firm conclusions being drawn from incomplete or misinterpreted data. The ultimate best practice is to use the tool with a full understanding of its boundaries, embracing it as a powerful instrument for discovery but never mistaking it for the final word in a high-stakes professional analysis.

| Table 1: Comparison of Free Patent Search Platforms | |||

| Feature / Criterion | Google Patents | USPTO Public Search | Espacenet |

| Global Coverage | Excellent (100+ patent offices) 70 | U.S. only 70 | Excellent (global coverage) 65 |

| Data Timeliness | Good, but can have lags 68 | Excellent (most current for U.S.) 68 | Very Good |

| Search Interface Usability | Excellent (intuitive, Google-like) 70 | Moderate (less intuitive, more complex) | Good (more suitable for experienced users) 65 |

| Advanced Search Syntax | Very Good (Boolean, proximity, fields) 27 | Excellent (very fine-grained field searching) 70 | Good (supports complex queries) |

| Integrated Non-Patent Lit. | Yes (Google Scholar/Books) 17 | No | No |

| Litigation Data | Yes (via Darts-ip integration) 17 | No | No |

| Analytics/Visualization | Basic (graphs of assignees/inventors) 17 | None | Basic |

| Special Features | PDF with OCR, machine translation, Prior Art Finder 17 | Official legal status (Public PAIR), file history | Detailed citation view (inventor vs. examiner), “My patents list” feature 72 |

Appendix

A.1 Glossary of Key Pharmaceutical Patent Claims

- Composition of Matter: Often called a “product patent,” this is a claim to a new chemical entity (NCE) or biological molecule itself. It is considered the “crown jewel” of pharmaceutical intellectual property because it provides the broadest protection, covering the active ingredient regardless of how it is made, formulated, or used.8

- Method of Use: Also known as a “process patent,” this claim protects a specific way of using a product to achieve a result. In pharmaceuticals, this typically means a new therapeutic application for a known drug (e.g., patenting the use of Drug X to treat Alzheimer’s, when it was previously only known to treat high blood pressure). These patents are a cornerstone of drug repurposing and “evergreening” strategies.56

- Formulation: A claim to a specific formulation of a drug, including the active ingredient and various inactive ingredients (excipients) that affect its delivery, stability, or release profile. Examples include patents on an extended-release tablet, a citrate-free injectable solution, or a specific nanoparticle delivery system.76

- Process: A claim to a specific method of manufacturing a drug or compound. This can protect a novel, more efficient, or purer synthesis pathway, creating a barrier for competitors even if the final compound itself is off-patent.3

A.2 Essential Tables for Reference

Table 1: Comparison of Free Patent Search Platforms

| Feature / Criterion | Google Patents | USPTO Public Search | Espacenet |

| Global Coverage | Excellent (100+ patent offices) 70 | U.S. only 70 | Excellent (global coverage) 65 |

| Data Timeliness | Good, but can have lags 68 | Excellent (most current for U.S.) 68 | Very Good |

| Search Interface Usability | Excellent (intuitive, Google-like) 70 | Moderate (less intuitive, more complex) | Good (more suitable for experienced users) 65 |

| Advanced Search Syntax | Very Good (Boolean, proximity, fields) 27 | Excellent (very fine-grained field searching) 70 | Good (supports complex queries) |

| Integrated Non-Patent Lit. | Yes (Google Scholar/Books) 17 | No | No |

| Litigation Data | Yes (via Darts-ip integration) 17 | No | No |

| Analytics/Visualization | Basic (graphs of assignees/inventors) 17 | None | Basic |

| Special Features | PDF with OCR, machine translation, Prior Art Finder 17 | Official legal status (Public PAIR), file history | Detailed citation view (inventor vs. examiner), “My patents list” feature 72 |

Table 2: Key CPC Codes for Pharmaceutical Research

| CPC Code | Description | Relevance to Pharma Research |

| A61K | Preparations for medical, dental, or toiletry purposes | The broadest and most important class for pharmaceuticals. Covers drug compositions, formulations, and cosmetics.19 |

| A61K 9/00 | Medicinal preparations characterised by special physical form | Covers specific dosage forms like tablets (A61K 9/20), injectable compositions (A61K 9/0019), or aerosols.32 |

| A61K 31/00 | Medicinal preparations containing organic active ingredients | Classifies drugs based on their chemical structure. Essential for small molecule drug searches.31 |

| A61K 39/00 | Medicinal preparations containing antigens or antibodies | Crucial for vaccines and antibody-based therapies (biologics).33 |

| C07K | Peptides | Covers peptides, proteins, and immunoglobulins (antibodies). This is the fundamental class for researching biologics.34 |

| C07K 16/00 | Immunoglobulins, e.g., monoclonal antibodies | A key subclass within C07K specifically for antibody technologies.36 |

| A61P | Specific therapeutic activity of chemical compounds | Classifies a drug based on its intended use or the disease it treats. This is an indexing code used in conjunction with others.37 |

| A61P 35/00 | Antineoplastic agents (anticancer drugs) | Used to find all drugs intended for cancer treatment, regardless of their chemical structure or mechanism.39 |

| A61P 3/10 | Drugs for hyperglycaemia, e.g., antidiabetics | Used to find drugs for treating diabetes.39 |

| C12N 15/09 | Recombinant DNA or RNA | Covers genetic engineering technologies, essential for the production of biologics and for gene therapies.33 |

Table 3: Google Patents Advanced Search Operator Cheat Sheet

| Operator Type | Operator Syntax | Function | Pharmaceutical Example |

| Boolean | A OR B | Finds documents containing either A or B. | (aspirin OR “acetylsalicylic acid”) |

| A AND B | Finds documents containing both A and B. | (atorvastatin AND formulation) | |

| A NOT B or A -B | Finds documents containing A but not B. | vaccine -adjuvant | |

| Field | assignee:(A) | Searches for patents owned by assignee A. | assignee:(“Pfizer Inc.”) |

| inventor:(A) | Searches for patents by inventor A. | inventor:(Kariko, Katalin) | |

| cpc:(A) | Searches for patents in classification A. | cpc:(A61P35/00) | |

| CL:(A) | Searches for term A only in the claims. | CL:(“crystalline form”) | |

| Proximity | A NEAR/x B | Finds A and B within x words, any order. | (sildenafil NEAR/10 “pulmonary hypertension”) |

| A ADJ/x B | Finds A and B within x words, in that order. | (“monoclonal antibody” ADJ/3 “humanized”) | |

| Wildcards | * | Zero or more characters (stemming). | immuno* (finds immune, immunology, etc.) |

| ? | Zero or one character. | analy?e (finds analyze and analyse) | |

| Phrases | “A B” | Finds the exact phrase “A B”. | “antibody-drug conjugate” |

Table 4: Patent Portfolio Summary – Humira vs. Lipitor

| Metric | Lipitor (Atorvastatin) | Humira (Adalimumab) |

| Primary Patent Filing Year | 1986 61 | c. 1993-1994 8 |

| FDA Approval Year | 1996/1997 58 | 2002 50 |

| Primary U.S. Patent Expiration | 2011 61 | 2016 57 |

| Approx. Granted U.S. Patents | ~49 (mean for blockbusters of its era) 63 | 130+ 51 |

| % of Patents Filed Post-Approval | Lower (strategy less developed) | 90-94% 51 |

| Key LCM Strategies | Formulation patents, combination therapy patents. | Dense “patent thicket” covering formulations, manufacturing, dozens of methods of use. |

| Outcome at Primary Patent Expiry | Immediate and sharp revenue decline (“patent cliff”).59 | U.S. biosimilar entry delayed by ~7 years through litigation on the patent thicket.8 |

Works cited

- The Crucial Role of Pharmaceutical Patents in Fostering Innovation – Sagacious IP, accessed August 3, 2025, https://sagaciousresearch.com/blog/crucial-role-pharmaceutical-patents-fostering-innovation/

- Pharmaceutical Patents and Evergreening (VIII) – The Cambridge Handbook of Investment-Driven Intellectual Property, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/cambridge-handbook-of-investmentdriven-intellectual-property/pharmaceutical-patents-and-evergreening/9A97A3E6D258E9A47DCF88E5EA495F44

- Optimizing Your Drug Patent Strategy: A Comprehensive Guide for …, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/optimizing-your-drug-patent-strategy-a-comprehensive-guide-for-pharmaceutical-companies/

- How Drug Life-Cycle Management Patent Strategies May Impact Formulary Management, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.ajmc.com/view/a636-article

- How drug life-cycle management patent strategies may impact formulary management – PubMed, accessed August 3, 2025, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28719222/

- Annual Pharmaceutical Sales Estimates Using Patents: A …, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/annual-pharmaceutical-sales-estimates-using-patents-a-comprehensive-analysis/

- Managing Patent Portfolios in the Pharmaceutical Industry – PatentPC, accessed August 3, 2025, https://patentpc.com/blog/managing-patent-portfolios-in-the-pharmaceutical-industry

- The Evolution of Patent Claims in Drug Lifecycle Management …, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-evolution-of-patent-claims-in-drug-lifecycle-management/

- pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov, accessed August 3, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4899342/#:~:text=Against%20this%20background%2C%20a%20dependence,cliff%E2%80%9D%20(Jimenez%202012).

- The Patent Cliff: From Threat to Competitive Advantage – Esko, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.esko.com/en/blog/patent-cliff-from-threat-to-competitive-advantage

- Patent Cliff: What It Means, How It Works – Investopedia, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.investopedia.com/terms/p/patent-cliff.asp

- The Art of the Second Act: A Six-Step Framework for Mastering Late-Stage Drug Lifecycle Management – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/6-steps-to-effective-late-stage-lifecycle-drug-management/

- Drug patents: the evergreening problem – PMC, accessed August 3, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3680578/

- Evergreening Strategy: Extending Patent Protection, Innovation or Obstruction?, accessed August 3, 2025, https://kenfoxlaw.com/evergreening-strategy-extending-patent-protection-innovation-or-obstruction

- Evergreening – Wikipedia, accessed August 3, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Evergreening

- Patent Portfolios Protecting 10 Top-Selling Prescription Drugs – PMC, accessed August 3, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11091822/

- Google Patents – Wikipedia, accessed August 3, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Google_Patents

- (PDF) Google Patents: The global patent search engine – ResearchGate, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/280301154_Google_Patents_The_global_patent_search_engine

- Using Google Patents for Drug Patent Research: A Comprehensive Guide, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/using-google-patents-for-drug-patent-research-a-comprehensive-guide/

- Google Patents: Tutorial and Guide | Proofed’s Writing Tips, accessed August 3, 2025, https://proofed.com/writing-tips/google-patents-tutorial-and-guide/

- How to Search for Patents Using Google Patents, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.pinepat.com/en/insights/columns/gugeul-teugheo-geomsaeg-bangbeob

- Google Patents Search – A Definitive Guide by GreyB, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.greyb.com/blog/google-patents-search-guide/

- How to Use Google Patents for Effective Patent Searches, accessed August 3, 2025, https://patentpc.com/blog/how-to-use-google-patents-for-effective-patent-searches

- www.drugpatentwatch.com, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/using-google-patents-for-drug-patent-research-a-comprehensive-guide/#:~:text=Navigating%20the%20Google%20Patents%20Interface&text=The%20homepage%20features%20a%20prominent,delivery%20systems%2C%20or%20disease%20states.

- 7 Advanced Google Patents Search Tips – GreyB, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.greyb.com/blog/google-patents-advanced-search/

- Google Patents Complete Search Guide | BatonRougePatentAttorney.com, accessed August 3, 2025, https://batonrougepatentattorney.com/

- Searching – Google Help, accessed August 3, 2025, https://support.google.com/faqs/answer/7049475?hl=en

- Cooperative Patent Classification (CPC) | epo.org, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.epo.org/en/searching-for-patents/helpful-resources/first-time-here/classification/cpc

- Patent classification | epo.org, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.epo.org/en/searching-for-patents/helpful-resources/first-time-here/classification

- Overview of CPC scheme and list of biotechnology classes/subclasses • CPC classification • Searching using CPC, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.aipla.org/docs/default-source/committee-documents/bcp-files/2019/cpcforbcp-approved.pdf

- CPC Definition – A61K PREPARATIONS FOR MEDICAL, DENTAL OR TOILETRY PURPOSES (devices or methods, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.uspto.gov/web/patents/classification/cpc/html/defA61K.html

- CPC Scheme – A61K PREPARATIONS FOR MEDICAL, DENTAL OR TOILETRY PURPOSES – USPTO, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.uspto.gov/web/patents/classification/cpc/html/cpc-A61K.html

- A61K – WIPO, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.wipo.int/classifications/ipc/en/ITsupport/Version20170101/transformations/ipc/20170101/en/htm/A61K.htm

- CPC Definition – C07K PEPTIDES (peptides in foodstuffs A23; obtaining protein compositions for f… – USPTO, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.uspto.gov/web/patents/classification/cpc/html/defC07K.html

- The image compares the frequency of patents categorized by their… – ResearchGate, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/figure/The-image-compares-the-frequency-of-patents-categorized-by-their-respective-codes-Panel_fig4_392054544

- C07K – Cooperative Patent Classification, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.cooperativepatentclassification.org/sites/default/files/cpc/scheme/C/scheme-C07K.pdf

- CPC Definition – A61P SPECIFIC THERAPEUTIC ACTIVITY OF CHEMICAL COMPOUNDS OR MEDICINAL PREPARATIONS – USPTO, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.uspto.gov/web/patents/classification/cpc/html/defA61P.html

- CPC Scheme – A61P SPECIFIC THERAPEUTIC ACTIVITY OF CHEMICAL COMPOUNDS OR MEDICINAL PREPARATIONS – USPTO, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.uspto.gov/web/patents/classification/cpc/html/cpc-A61P.html

- SPECIFIC THERAPEUTIC ACTIVITY OF CHEMICAL COMPOUNDS OR MEDICINAL PREPARATIONS – Cooperative Patent Classification, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.cooperativepatentclassification.org/sites/default/files/cpc/scheme/A/scheme-A61P.pdf

- Advanced Guide to Google Patent Search | Bold Patents, accessed August 3, 2025, https://boldip.com/blog/google-patent-search-bp/

- How to Track Competitor R&D Pipelines Through Drug Patent Filings, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/how-to-track-competitor-rd-pipelines-through-drug-patent-filings/

- Google Patents Public Datasets: connecting public, paid, and private patent data, accessed August 3, 2025, https://cloud.google.com/blog/topics/public-datasets/google-patents-public-datasets-connecting-public-paid-and-private-patent-data

- Best Practices for Drug Patent Portfolio Management: Leveraging Patent Data for Competitive Advantage – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/best-practices-for-drug-patent-portfolio-management-2/

- How to Search for Patents by Company Name Efficiently – Lumenci, accessed August 3, 2025, https://lumenci.com/blogs/search-for-patents-by-company-name/

- New Guide Explains How to Use Google Patents to Identify Drug Patent Holders and Track Competitor Activity – GeneOnline News, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.geneonline.com/new-guide-explains-how-to-use-google-patents-to-identify-drug-patent-holders-and-track-competitor-activity/

- How to Conduct a Drug Patent FTO Search: A Strategic and Tactical …, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/how-to-conduct-a-drug-patent-fto-search/

- IP: Writing a Freedom to Operate Analysis – InterSECT Job Simulations, accessed August 3, 2025, https://intersectjobsims.com/library/fto-analysis/

- How do you conduct a FTO Patent Search? – Quora, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.quora.com/How-do-you-conduct-a-FTO-Patent-Search

- Tool 5 Freedom to Operate – WIPO, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.wipo.int/documents/d/tisc/docs-en-tisc-toolkit-freedom-to-operate-description.pdf

- Adalimumab – Wikipedia, accessed August 3, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Adalimumab

- Humira – I-MAK, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.i-mak.org/humira/

- FACT SHEET: BIG PHARMA’S PATENT ABUSE COSTS AMERICAN PATIENTS, TAXPAYERS AND THE U.S. HEALTH CARE SYSTEM BILLIONS OF DOLLARS – CSRxP.org, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.csrxp.org/fact-sheet-big-pharmas-patent-abuse-costs-american-patients-taxpayers-and-the-u-s-health-care-system-billions-of-dollars-2/

- US10493152B2 – Adalimumab formulations – Google Patents, accessed August 3, 2025, https://patents.google.com/patent/US10493152B2/en

- US11229702B1 – High concentration formulations of adalimumab – Google Patents, accessed August 3, 2025, https://patents.google.com/patent/US11229702B1/en

- When will the HUMIRA patents expire, and when will biosimilar HUMIRA launch? – Drug Patent Watch, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/p/biologics/tradename/HUMIRA

- The value of method of use patent claims in protecting your …, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-value-of-method-of-use-patent-claims-in-protecting-your-therapeutic-assets/#:~:text=What%20Exactly%20is%20a%20Method,or%20utilization%20of%20a%20product.

- Getting Lost in the Thicket: AbbVie Wields Its Expansive Humira® Patent Portfolio Against Alvotech’s Adalimumab Biosimilar, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.biosimilarsip.com/2021/06/24/getting-lost-in-the-thicket-abbvie-wields-its-expansive-humira-patent-portfolio-against-alvotechs-adalimumab-biosimilar/

- “For Me There Is No Substitute”: Authenticity, Uniqueness, and the Lessons of Lipitor, accessed August 3, 2025, https://journalofethics.ama-assn.org/article/me-there-no-substitute-authenticity-uniqueness-and-lessons-lipitor/2010-10

- Lipitor History and Information – DrugClaim.com, accessed August 3, 2025, https://drugclaim.com/lipitor-history/

- Who holds the patent for Atorvastatin? – Patsnap Synapse, accessed August 3, 2025, https://synapse.patsnap.com/article/who-holds-the-patent-for-atorvastatin

- Atorvastatin – Wikipedia, accessed August 3, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Atorvastatin

- US6235311B1 – Pharmaceutical composition containing a combination of a statin and aspirin and method – Google Patents, accessed August 3, 2025, https://patents.google.com/patent/US6235311B1/en

- EVIDENCE OF ‘EVERGREENING’ IN SECONDARY PATENTING OF BLOCKBUSTER DRUGS – Melbourne Law School, accessed August 3, 2025, https://law.unimelb.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0006/3606513/Christie,-Dent-and-Studdert-442-Advance.pdf

- Google Patent Search vs. USPTO: Which One Should You Use? – Emanus LLC, accessed August 3, 2025, https://emanus.com/google-patent-search-vs-uspto-guide/

- Different Types of Patent Searches – What’s Available and Why Use Them?, accessed August 3, 2025, https://sourceadvisors.co.uk/insights/knowledge-hub/different-types-of-patent-searches/

- Using Google Patents to Find Drug Patents? Here’s 15 Reasons Why You Shouldn’t, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/using-google-patents-to-find-drug-patents-heres-15-reasons-why-you-shouldnt/

- Google Patents: Why It’s a Risky Tool for Finding Drug Patents – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/google-patents-why-its-a-risky-tool-for-finding-drug-patents/

- Google Patents Search – Neustel Law Offices, accessed August 3, 2025, https://neustel.com/patents/google-patents-search/

- The Hidden Pitfalls of Searching Drug Patents on Google Patents – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-hidden-pitfalls-of-searching-drug-patents-on-google-patents/

- “That means nothing to me as a normal person who doesn’t know about patents”: Usability testing of Google – Clemson OPEN, accessed August 3, 2025, https://open.clemson.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1034&context=jptrca

- search – Are there differences between Google Patents, Espacenet …, accessed August 3, 2025, https://patents.stackexchange.com/questions/23195/are-there-differences-between-google-patents-espacenet-the-lens-and-patentscop

- What Are The Differences Between Google Patents And Espacenet? – SearchEnginesHub.com – YouTube, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=l21-sAYbfdA

- library.fiveable.me, accessed August 3, 2025, https://library.fiveable.me/key-terms/introduction-to-pharmacology/composition-of-matter-patents#:~:text=Citation%3A-,Definition,combination%20of%20ingredients%20or%20components.

- Composition of matter – Wikipedia, accessed August 3, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Composition_of_matter

- Method of Use Patents – (Intro to Pharmacology) – Vocab, Definition, Explanations | Fiveable, accessed August 3, 2025, https://library.fiveable.me/key-terms/introduction-to-pharmacology/method-of-use-patents

- The Role of Patents and Regulatory Exclusivities in Drug Pricing | Congress.gov, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/R46679