The Multi-Trillion-Dollar Pivot

If you are an IP strategist, a business development leader, or an R&D chief in the pharmaceutical world, you already know the truth: the game has changed. The era of the small-molecule blockbuster, while far from over, has ceded the strategic high ground. The future—and the present, for that matter—is being written by biologics.

This isn’t hype; it’s a multi-trillion-dollar market pivot. Biologics, including monoclonal antibodies, cell and gene therapies, and next-generation RNA therapeutics, represent the industry’s undisputed growth engine.1 This shift is profound. In the United States, biologics account for a staggering portion of prescription medicine spending—over half by some estimates—despite representing only about 3% of all prescriptions.3

This creates a high-stakes environment where a single patent, or a single legal decision, can be worth tens of billions of dollars. But here is the central paradox of our industry today: even as the science of biologic development becomes more predictable—think of AI-driven protein design or high-throughput platform technologies 4—the patent law governing these life-saving innovations has become profoundly unpredictable.

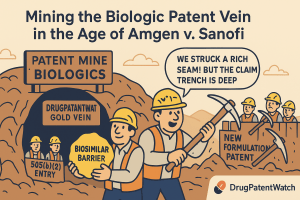

Landmark court decisions have shattered decades of accepted patenting strategy. The Supreme Court’s 2023 ruling in Amgen v. Sanofi 6 sent a shockwave through every IP department, invalidating a multi-billion-dollar patent estate and redrawing the boundaries of the “patent bargain.” In parallel, cases like REGENXBIO v. Sarepta 7 are questioning the very patent-eligibility of gene therapies, creating existential legal risk for the industry’s most advanced technologies.

This report is not an academic review of these cases. It is a strategic map for navigating this new, high-risk, high-reward territory. We are here to answer the questions that keep you, your general counsel, and your investors awake at night. How do you build a patent fortress that can withstand this new legal reality? How do you dismantle a competitor’s fortress? And how do you turn patent data into durable competitive advantage?

The Stakes: Why IP Strategy is Everything for Biologics

For small-molecule drugs, the IP strategy is often elegant in its simplicity: secure a rock-solid composition-of-matter (CoM) patent on the active ingredient and you’ve secured the asset.

This is not the world of biologics.

The cost to develop a biologic is immense, but its true value is not locked in a single molecule. It’s embedded in a complex, sprawling ecosystem of intellectual property.2 The biologic itself is just the start. The real, durable monopoly is built by patenting the genetically engineered host cell that creates it, the complex purification process that refines it, the novel formulation that stabilizes it, the specific dosing regimen that administers it, the diagnostic assay that measures it, and the autoinjector pen that delivers it.

This “patent thicket,” long criticized by outsiders, is not just a legal strategy; it is the only strategy that reflects the scientific reality of the product.

This report is your playbook for building, defending, and challenging these 21st-century IP fortresses. We will move from the foundational legal principles that separate biologics from small molecules to the landmark court battles that have defined the new rules of engagement. We will deconstruct the “thicket” brick by brick, analyze the multi-billion-dollar sagas of Humira and Enbrel, and finally, look over the horizon at the next-generation challenges of patenting AI-designed proteins and cell therapies.

Your competition is already operating under these new rules. Let’s make sure you are too.

More Than a ‘Big Molecule’: Deconstructing the Biologic Patenting Paradigm

The Fundamental Chasm: Why Biologics Aren’t Just ‘Big Drugs’

Before you can build a strategy, you must understand the terrain. The single biggest mistake we see in this field is teams applying small-molecule IP logic to a biologic asset. It’s like using a 19th-century map to navigate a modern city. The core principles simply do not apply.

This strategic divergence isn’t driven by lawyers or regulators; it’s driven by fundamental, non-negotiable science.

Size, Complexity, and Heterogeneity

First, consider the sheer scale. A typical small-molecule drug like paroxetine (Paxil) has a molecular weight of about 329 grams per mole.9 It’s a simple, well-defined chemical structure. A biologic like human growth hormone, by contrast, weighs in around 22,000 g/mol.9 A standard monoclonal antibody (mAb) — the workhorse of the industry—is a behemoth, tipping the scales at approximately 150,000 Daltons.10

You don’t synthesize a 150,000-Dalton molecule in a lab; you grow it. Biologics are produced in living organisms or cells 9—a complex, messy, and inherently variable biological process.

This process leads to the most important concept in our entire field: “inherent heterogeneity”.11 Unlike a pure chemical, a batch of a biologic drug is never 100% uniform. It’s a population of highly similar, but not identical, molecules. These molecules have subtle but unavoidable variations in their three-dimensional folding and, most critically, in their complex “sugar-coatings,” a process called glycosylation.9 These glycosylation patterns are not decorative; they are integral to the drug’s safety, efficacy, and stability.

“Identical” vs. “Highly Similar”: The Birth of the Biosimilar

This scientific reality has a profound legal consequence. Because of this inherent heterogeneity, it is scientically impossible for a competitor to create an exact replica of an innovator’s biologic.11

Therefore, the law cannot have “generic” biologics.

Instead, the regulatory framework created an entirely new category: the “biosimilar”. A biosimilar is a product that is “highly similar” to the innovator’s reference product, with “no clinically meaningful differences” in terms of safety, purity, and potency.11

This distinction is the bedrock of your entire IP strategy. The impossibility of perfect replication is the scientific and legal justification for the “process is the product” doctrine. And the “process is the product” doctrine is the engine that fuels the “Type I” patent thicket, which we will deconstruct in detail.

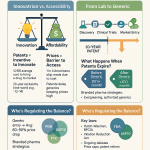

The Regulatory and Exclusivity Divide

These scientific differences created two parallel universes for drug development, each with its own set of laws, timelines, and strategic loopholes.

Hatch-Waxman (Small Molecules) vs. BPCIA (Biologics)

For your small-molecule assets, your world is governed by the Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984, universally known as the Hatch-Waxman Act.8 This framework governs the approval of “generic” drugs.

For your biologic assets, your world is the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act of 2009 (BPCIA).8 This is the law that created the “biosimilar” pathway, and its mechanisms—particularly the “patent dance”—are a central focus of this report.

The 12-Year vs. 5-Year Exclusivity “Myth”

On the surface, the BPCIA seems to give biologics a major advantage. Innovator biologics receive 12 years of FDA-granted regulatory exclusivity, meaning the FDA cannot approve a biosimilar during that time.13 New small-molecule drugs, by contrast, typically receive only 5 years of exclusivity.20

But relying on this 12-year clock is one of the most dangerous strategic myths in our industry.

Congress granted this longer exclusivity period based on a key assumption: that biologics development was far more expensive and, critically, that biologic patents were weaker and easier to design around than small-molecule patents.20

The last decade has proven this assumption spectacularly wrong. As the Humira and Enbrel case studies will demonstrate, the 12-year exclusivity clock is merely the opening bid. The real monopoly, which can stretch to 20 or even 30 years, is not maintained by this FDA-granted exclusivity. It is maintained by a dense, multi-layered, and brilliantly executed patent thicket.21

The Orange Book vs. The Purple Book: A Critical Strategic Difference

Here is a subtle but powerful difference that many teams overlook. For small-molecule drugs, the Hatch-Waxman Act requires an innovator to proactively list all relevant patents in the FDA’s “Orange Book”.24 This gives generic competitors perfect, early visibility into the patent fortress they will have to challenge.

The BPCIA has no such requirement. The FDA’s “Purple Book” (the biologic equivalent) does not require the innovator to list its patents.25 In fact, the full scope of the innovator’s patent estate is often only disclosed after a biosimilar competitor has already spent hundreds of millions on development and formally initiates the BPCIA “patent dance”.25

This “reactive” patent disclosure system is a powerful strategic feature for innovators. It creates a “fog of war” for biosimilar developers. They are forced to invest time and capital to navigate the complex biosimilarity development path, all without knowing the full scope of the patent minefield they will have to cross.

This fundamental chasm between the two asset classes is summarized below. Every difference in this table represents a strategic opportunity—or a costly pitfall.

Table 1: Small Molecule vs. Biologic: The Strategic IP Chasm

| Feature | Small-Molecule Drug | Biologic Drug |

| Molecular Weight | Low (e.g., < 900 Daltons) 11 | High (e.g., 10,000-150,000+ Daltons) [9, 10] |

| Structure/Complexity | Simple, well-defined chemical structure [11, 12] | Large, complex 3D structure; inherently heterogeneous 9 |

| Replication | “Generic” (identical) 11 | “Biosimilar” (highly similar, but not identical) 11 |

| Manufacturing | Chemical synthesis [10] | Produced in living cells (e.g., CHO) [9, 12] |

| Regulatory Path | Hatch-Waxman Act [9, 18] | Biologics Price Competition & Innovation Act (BPCIA) 8 |

| Patent Listing | Proactive: Innovator lists patents in “Orange Book” 25 | Reactive: Patents listed in “Purple Book” after BPCIA litigation is initiated 25 |

| Base Regulatory Exclusivity | 5 years (New Chemical Entity) 20 | 12 years (New Biologic) 13 |

| Primary Patent Strategy | Core composition-of-matter (CoM) patent. | Patent Thicket: Layered patents on CoM, manufacturing process, formulation, device, method of use, etc. 21 |

The Amgen Earthquake: Why “The More You Claim, The More You Must Enable” Changes Everything

The Case That Redefined the Patent Bargain: Amgen v. Sanofi

On May 18, 2023, the Supreme Court issued a unanimous decision that effectively ended a 40-year-old patenting strategy. This wasn’t a minor tweak; it was a fundamental reset of the “patent bargain” for the entire biopharmaceutical industry.6

The case, Amgen v. Sanofi, was a battle of titans. It pitted Amgen’s Repatha against Sanofi’s Praluent, two blockbuster monoclonal antibodies that lower LDL cholesterol by targeting the PCSK9 protein.28

The dispute centered on Amgen’s “genus” patents. Amgen had not just patented the 26 specific antibodies it had discovered. It patented the entire class of antibodies that performed a specific function: (1) binding to a specific sweet-spot (epitope) on the PCSK9 protein, and (2) blocking PCSK9 from binding to LDL receptors.28 This “functional” claim was breathtakingly broad, potentially covering millions of undiscovered antibody sequences.30

Sanofi’s Praluent, a different antibody that performed the same function, was a clear infringer. Sanofi’s only defense was to argue that Amgen’s patents were invalid. They argued that Amgen’s specification, which only described 26 antibodies, could not possibly “enable” a person skilled in the art to make and use the millions of antibodies Amgen claimed.

The Supreme Court unanimously agreed with Sanofi.28

Deconstructing 35 U.S.C. § 112: The “Quid Pro Quo”

To understand why this ruling is so transformative, you must understand the “quid pro quo” (this for that) of patent law, codified in 35 U.S.C. § 112. This law contains two distinct and often-confused requirements: Written Description and Enablement.31

Written Description vs. Enablement: A Critical Distinction

For IP teams, the distinction is critical:

- Written Description (WD): This requirement is backward-looking. It is evidentiary. It asks: “Does this patent application prove that you, the inventor, were in possession of the claimed invention at the time you filed?”. It’s a “what did you have?” test.

- Enablement: This requirement is forward-looking. It is instructive. It asks: “Does this patent application teach a person of ordinary skill in the art (POSA) how to make and use the invention across its full scope?”.27 It’s a “what can you teach?” test.

The Amgen case was decided on enablement.6 Amgen may have possessed its 26 antibodies (meeting the WD requirement), but it failed to teach the world how to make and use the entire genus of antibodies it claimed to own.

Table 2: The Amgen Impact: Enablement vs. Written Description

| Requirement | 35 U.S.C. § | Core Question | Strategic Focus |

| Written Description | 35 U.S.C. § 112(a) | “Did you possess the invention on your filing date?” | Evidentiary (Backward-Looking): Proving possession with data, sequence listings, and examples. |

| Enablement | 35 U.S.C. § 112(a) | “Can a skilled person make and use the full scope of your claim?” 31 | Instructive (Forward-Looking): Providing a reliable “recipe” for the entire class, not just a “hunting license.” |

The Supreme Court’s Maxim: “The More One Claims, The More You Must Enable”

The Fall of the Functional Genus Claim

Justice Gorsuch, writing for the unanimous Court, distilled the case down to a simple, powerful maxim: “The more one claims, the more one must enable”.31

Amgen’s “functional” claim to millions of potential antibodies 30 was supported by a specification that only provided 26 concrete examples.29 The Court found that Amgen’s “roadmap” for finding other antibodies that worked was “little more than a trial-and-error process” 30—a “research assignment” or a “hunting license”.29

This was not enough. The Court’s holding was a clear directive: “If a patent claims an entire class… the patent’s specification must enable a person skilled in the art to make and use the entire class”.31 In an “unpredictable art” like antibody engineering, where changing a single amino acid can destroy function, Amgen’s specification was woefully inadequate.

The Wands Factors and “Undue Experimentation”

This ruling does not mean all broad claims are invalid. The long-standing legal test for enablement is whether a POSA would have to engage in “undue experimentation” to practice the invention.32

For decades, courts have used a set of eight “Wands factors” 32 to determine what “undue” means, including:

(A) The breadth of the claims;

(E) The level of predictability in the art;

(G) The existence of working examples; and

(H) The quantity of experimentation needed.

The Supreme Court’s Amgen decision didn’t overturn the Wands test; it supercharged it. The ruling effectively says that in an “unpredictable art” (Factor E), the “quantity of experimentation” (Factor H) needed to validate a “broad claim” (Factor A) will almost always be “undue.”

Post-Amgen Strategy: The New Playbook

For innovators and patent challengers, the strategic implications are immediate and profound.

The Pivot from Broad Functional Claims

The Amgen holding is a “clear caution signal” for anyone drafting broad, functionally defined antibody claims.27 The strategy of “claiming all antibodies that bind to X and do Y” is, for all practical purposes, dead. Patent prosecutors must change their claiming strategy.28

The Rise of the “Structural” Claim

The future of core biologic patenting now rests on narrower, but far more defensible, structural claims. This means claiming the specifics of your invention:

- The specific amino acid sequences of the six Complementarity-Determining Regions (CDRs) that form the “fingers” of the antibody.33

- The specific nucleic acid sequences that encode the antibody.35

- Or, if you must claim a genus, you must also disclose a “general quality… running through the class” that gives it a “peculiar fitness” and reliably enables a POSA to make and use the entire class.

Amgen is a classic double-edged sword. On one hand, it makes it much harder for innovators to get the broad, powerful, “block-the-whole-target” patents they once coveted.

On the other hand, this ruling has a tectonic strategic consequence. By blowing up the front gate, Amgen has made the rest of the fortress more valuable. The Amgen decision strategically devalues the core composition-of-matter (CoM) patent, which is now narrower and more vulnerable.

As a result, the AmIS_S massively increases the strategic value of the patent thicket. The battle is no longer about winning the war with one “super-patent.” The battle has moved to the perimeter—to the hundreds of secondary patents on formulations, manufacturing processes, and delivery devices. This is the new landscape.

Claiming the Core Asset: Strategies for the Biologic Molecule

In this new post-Amgen world, your core asset strategy must be sharper, more specific, and more diversified. You can no longer rely on a single, broad functional claim. Instead, you must build a portfolio of claims around the molecule itself.

The “What”: Patenting the Molecular Structure

Sequence Claims (The New Gold Standard)

This is now the most secure, defensible, post-Amgen claiming strategy. You claim what you know you have invented:

- Amino Acid Sequences: The specific amino acid sequences of the full-length antibody, or, more commonly, the six specific CDRs that define its binding properties.34

- Nucleic Acid Sequences: The DNA or RNA sequences that encode your protein.34

These claims are narrow—a competitor could theoretically change an amino acid and “design around” them. However, they are exceptionally strong against an exact biosimilar copy.

Fragments, Isoforms, and Fusion Proteins

This is where the claiming strategy gets more complex, pushing into the legal “gray zones” of 35 U.S.C. § 101, which bars the patenting of “products of nature.”

Fragments and Isoforms: The “Markedly Different” Hurdle

What if your invention isn’t a full protein, but a fragment of one, or a naturally-occurring isoform? Here, you run into the “product of nature” doctrine. To be patentable, your claimed invention must be “markedly different” from what exists in nature.

This creates a high-stakes argument. An innovator might claim a protein fragment and argue it has a new, “markedly different” function, such as “increased solubility” where the full-length protein was insoluble.37 This makes it a viable vaccine antigen, a new and useful invention.

However, a patent examiner may (and often will) reject this. The examiner can argue that (a) a change in function is not a change in structure, and (b) protein fragments occur naturally when proteins are digested. This is a high-risk, high-reward claim that must be supported by extensive data in the specification.

“Bio-betters” and Fusion Proteins (Half-Life Extension)

A more common and commercially powerful strategy is “lifecycle management” via the creation of a “bio-better”.2 You take your existing, successful biologic and improve it.

The most common way to do this is to extend its half-life, reducing dosing frequency. This is often done by fusing the biologic to a long-lasting carrier protein, such as Human Serum Albumin (HSA) or the Fc (constant) fragment of an antibody.38

This strategy, however, is now a victim of its own success. As a patenting strategy, it is now “considered an obvious approach to take”. Patent offices are saturated with these applications.

This means you can no longer get a patent simply for claiming the expected benefit (a longer half-life). To overcome an “obviousness” rejection, your patent application must demonstrate “unexpected results”.42 For example, you must show that your new fusion protein doesn’t just last longer, but also has a new biological activity, a surprisingly high increase in potency, or a novel and beneficial change in biodistribution.

The “How”: Patenting by Function and Property

This is a more sophisticated strategy: claiming the biologic not just by its sequence, but by its unique, engineered properties.

Post-Translational Modifications (PTMs): The Glycosylation Fortress

This is one of the most elegant and defensible strategies available, precisely because it is so complex. As we’ve established, biologics have complex sugar molecules (glycans) attached to them.9 This glycosylation is critical to function 43 but is inherently variable.13

A savvy innovator can build a three-walled fortress around PTMs. You file a portfolio of patents that claim:

- A Specific, Desirable Glycosylation Pattern: A patent on the final product, claiming a specific “glycoform” that is correlated with higher efficacy or stability.45

- The Manufacturing Method to Produce That Pattern: A patent on the novel cell culture conditions or purification steps used to control PTMs and produce that specific desirable pattern.45

- The Analytical Assay to Measure That Pattern: A patent on the novel mass spectrometry or liquid chromatography method 46 used to characterize and confirm that the desired glycosylation pattern exists.

This creates an incredibly difficult-to-penetrate barrier. A biosimilar competitor is trapped.

Epitope and Functional Binding (The Amgen Minefield)

This brings us back to Amgen. This strategy involves claiming an antibody by what it does (e.g., “an antibody that binds to epitope X”) rather than what it is (e.g., “an antibody with sequence Y”).

As we’ve seen, this strategy is now in the middle of a legal minefield. Post-Amgen, filing a broad functional claim is exceptionally high-risk.27 It is only viable if your specification provides a truly enabling roadmap for the entire claimed genus—something far more robust than a “research assignment”.29

Navigating Obviousness (35 U.S.C. § 103)

Even if your claim is novel, eligible, and enabled, it can still be rejected as obvious under 35 U.S.C. § 103.

The “Obvious to Try” Trap

Since the Supreme Court’s 2007 decision in KSR v. Teleflex, it has become much easier for patent examiners to reject claims as “obvious to try”.48 This is a major hurdle. If the prior art suggests a “reasonable expectation of success,” your invention—even if novel—might be deemed unpatentable.48

Structural Non-Obviousness: The US vs. EPO Divide

This is one of the most critical and often-misunderstood differences in global patent strategy.

- In the United States: A novel amino acid sequence is typically considered “structurally non-obvious”.33 The USPTO generally accepts that if you created a new sequence, it is non-obvious, unless the prior art provided a clear reason to make that specific change.

- In Europe: This is not true. The European Patent Office (EPO) has explicitly held that “the fact that an antibody’s structure… is not predictable is not a reason for considering the antibody to be non-obvious”.49

The strategic implication is massive: A US-centric patent application that relies only on a novel sequence will fail at the EPO. To win in Europe, your application must demonstrate an inventive step. You must show that your antibody:

- Overcomes a specific technical difficulty in its generation or manufacturing.49

- Possesses a new, unexpected functional property.42

“Unexpected Results”: The Universal Antidote to Obviousness

This brings us to the universal antidote. The single best way to overcome an obviousness rejection (in any jurisdiction) is to fill your patent specification with data demonstrating unexpected results.42

Your invention isn’t just different; it’s better in a way no one could have predicted. Your specification should be loaded with data showing your biologic has:

- Vastly improved affinity or specificity.42

- New or improved biological activity.42

- Superior stability in solution.42

- Reduced toxicity.42

Without this data, you are handing an examiner the ammunition to reject your claims as “obvious to try.”

The Unseen Fortress: How “Process is the Product” Creates Durable Exclusivity

The Core Concept: “The Process Defines the Product”

We now move from the asset itself to the creation of the asset. This is where biologic patent strategy truly diverges from the small-molecule world and where the most durable, long-term fortresses are built.

We’ve established that biologics are complex, heterogeneous, and impossible to fully characterize.11 This scientific problem has a profound legal and regulatory solution. If you cannot fully define the product, you must define it by the process used to make it.9

For biologics, the FDA-approved manufacturing pathway is the product.12 This is the “process is the product” doctrine.

This means that every single step of your complex biomanufacturing workflow is a potential source of a new, powerful, and

long-lasting patent.

Patenting the Biomanufacturing Workflow (The “How-To”)

This is the “Type I” patent thicket.26 It is not a collection of duplicative, “junk” patents. It is a layered defense of legitimate, inventive patents covering every critical step of your proprietary workflow.8

Host Cell Lines (The “Factory”)

Your biologic is not made in a test tube; it’s made in a “factory”—a living cell line, typically a genetically engineered Chinese Hamster Ovary (CHO) cell.51 The value of this “master cell bank” is immense.

A powerful and fundamental patenting strategy is to patent the host cell line itself.51 Even more advanced strategies involve patenting a novel method for creating “super-producer” cell lines—for example, a proprietary cell fusion technique 53 or a method for selecting cells with a higher density of protein-producing organelles like the endoplasmic reticulum.53

A patent on the “factory” is one of the strongest barriers you can build.

Upstream Processes (The “Recipe”)

“Upstream” refers to the cell growth phase. Here, you patent the “recipe” for making the cells thrive and produce your protein. This includes:

- The unique, proprietary cell growth medium (the “food”).8

- The specific culture conditions (temperature, pH, bioreactor design).

- The novel feeding strategies used to maximize protein expression.

Downstream Purification (The “Refinery”)

This is a massive and high-value area for patenting. Your bioreactor produces a complex “soup” of your desired antibody and millions of other host cell proteins (HCPs) and impurities. “Downstream” is the “refinery” process used to purify your biologic to 99.999% purity.

You must patent your entire, unique purification “train”:

- Novel chromatography steps (e.g., affinity, ion-exchange, hydrophobic interaction).55

- Proprietary affinity resins (e.g., a new Protein A resin).58

- Specific filtration methods (e.g., tangential flow filtration).59

A competitor may be able to make a similar protein, but they cannot purify it using your patented, FDA-approved process.

Analytical and QC Methods (The “Rule”)

This is, in our opinion, the most brilliant and subtle strategy in the entire playbook. You patent the assays and diagnostic methods 60 that you use to prove to the FDA that your biologic meets its quality, purity, and potency specifications.14

This creates a devastating “Catch-22” for the biosimilar applicant.

To get FDA approval, the biosimilar must conduct extensive analytical studies to prove its product is “highly similar” to your reference product.63 What happens if you, the innovator, have patented the only reliable, high-resolution QC assay to demonstrate that similarity?

The biosimilar is left with two terrible choices:

- Don’t use the assay: They fail to provide the FDA with the required comparability data and their application is rejected.

- Use the assay: They provide the FDA with the data, get approved… and are now guilty of infringing your patent.

The Strategic Value of Process Patents

For decades, process patents were seen as “secondary” or “weak.” In the biologic space, they are a primary line of defense.13

What makes them uniquely powerful in the U.S. is the BPCIA “patent dance” itself. As noted in research and analysis, the “dance” requires the biosimilar applicant to disclose its confidential manufacturing process to the innovator at the very beginning of litigation.

This is an unprecedented strategic gift. In any other industry, proving infringement of a competitor’s internal manufacturing process is nearly impossible. You would have to get inside their factory.

In the BPCIA, the competitor hands you their blueprints.13 The innovator’s legal team can then calmly compare those confidential blueprints against their “Type I” thicket of process patents—the cell line patent, the medium patent, the purification patents, the QC assay patent. They can identify guaranteed points of infringement before the lawsuit has even truly begun.

This turns your process patents from a defensive shield into an offensive spear.

The Architecture of the “Patent Thicket”: A Strategic Playbook

Defining the “Thicket”: Innovation or Exploitation?

No term in our industry is more loaded than “patent thicket.” It’s defined as a dense, overlapping web of patents on a single drug.21

To its critics, the thicket is “systemic abuse,” “exploitation” 21, and a “numbers game” 23 played with “duplicative” 23 or “non-inventive” 26 patents. The sole purpose, they argue, is to create an impenetrable legal “force field” that deters competition through prohibitive litigation cost and uncertainty, even after the core patents have expired.65

To its defenders, the thicket is simply “life cycle management”.67 A biologic is not one invention; it is, quite literally, dozens of separate, complex, and patentable inventions.8 The “thicket” is just the legitimate and necessary patenting of the molecule, the cell line, the manufacturing process, the formulation, and the delivery device.2 As one court asked in the Humira litigation, “what’s wrong with having lots of patents? If AbbVie made 132 inventions, why can’t it hold 132 patents?”.68

The “Two Thicket” Model: A Critical Distinction

The problem with this debate is that both sides are right.

The term “patent thicket” is imprecise because it bundles two strategically distinct types of patent portfolios. A 2018 analysis proposed a “Two Thicket” model that is, in our view, the single most important framework for any legal or business development team to understand.26

Type I Thicket (Inherent Complexity)

- Definition: A large number of non-overlapping or inventive patents that cover different, legitimate aspects of the drug.26

- Source: This thicket is the natural result of the “process is the product” doctrine.26

- Composition:

- One patent on the molecule (e.g., the CDR sequences).

- One patent on the CHO cell line used to make it.51

- A patent on the novel purification step.55

- A patent on the high-concentration, citrate-free formulation.67

- A patent on the autoinjector pen.69

- Strategic Profile: These are strong, inventive, high-quality patents. They are difficult to invalidate. A biosimilar’s best strategy against a Type I patent is often to design around it (e.g., develop a different formulation).

Type II Thicket (Strategic Duplication)

- Definition: A large number of arguably overlapping or non-inventive patents that are “prone to double patenting”.26

- Source: This thicket is the artificial result of a deliberate legal strategy.

- Composition:

- Often composed of dozens of continuation applications.65

- These patents cover the same aspect of the drug with minor, often trivial, tweaks.

- Analysis of the Humira thicket, for example, found that approximately 80% of its patents were “duplicative”.23

- Strategic Profile: The purpose of this thicket is not to protect invention, but to create litigation friction. The goal is to build a “numbers game”.23

This “Type I / Type II” distinction is the key to both building and defeating a thicket. You don’t “challenge the thicket”; you challenge it patent by patent. Your strategy to defeat a weak “Type II” continuation patent (e.g., arguing obviousness-type double patenting) is completely different from your strategy to defeat a strong “Type I” process patent (e.g., arguing non-infringement or designing around it).

The Bricks of the Fortress: Mastering Secondary Patent Strategy

The “Type I Thicket” is built from high-quality, inventive “bricks.” These are the so-called “secondary” patents that, when layered correctly, create a fortress that can last for decades. Let’s examine the most important bricks in the playbook.

Formulations and Excipients (The “Vehicle”)

The core biologic (the “payload”) is often fragile. It must be protected by its “vehicle”: the formulation. Patenting the formulation is a classic and highly effective “evergreening” tactic.24

This strategy often manifests as a “product hop.” Years before the core patent on Humira expired, AbbVie patented and moved the entire market to a new, high-concentration, “citrate-free” (i.e., less painful) formulation.68

When biosimilars finally arrived, they were approved to compete with the old, painful, low-concentration formulation that doctors were no longer prescribing. It’s a brilliant “checkmate” move that renders the biosimilar commercially obsolete before it even launches.

A related strategy is to patent the use of novel excipients—the inactive ingredients.73 If a biologic requires a unique stabilizing agent to maintain its shelf life, a patent on the formulation containing that excipient can be just as powerful as the patent on the biologic itself.72

Delivery Devices (The “Weapon”)

Autoinjectors and Pen Devices

Biologics are not pills. They are complex molecules that are typically injected or infused.10 This is not a bug; it’s a strategic feature.

Patenting the delivery device—the autoinjector pen—is one of the most critical and powerful strategies in the entire playbook.69 A device patent grants a new 20-year monopoly that is completely independent of the drug patent.

A biosimilar manufacturer may win the right to manufacture the biologic drug, but if they cannot legally put that drug into a user-friendly, patent-protected pen, they cannot compete. Patients will not abandon a simple “click-to-inject” pen (like the Humira pen 75) for a 19th-century vial-and-syringe kit.

Case Study: Kymanox and the Blockbuster Biologic

The value of this strategy is underscored by the sheer complexity of device development. A case study from Kymanox, a firm that manages this process, highlights the end-to-end challenge.74 Developing a new autoinjector is an “end-to-end” R&D program in itself. It requires:

- Complex device and primary container engineering.

- Comprehensive Human Factors (HF) optimization to ensure patient usability and safety.

- Robust quality planning and design verification testing.

- A new regulatory submission for the “combination product.”

Each of these steps—the unique spring mechanism, the ergonomic casing, the needle-shrouding system—is a new source of patentable inventions.74

Methods of Use and Dosing (The “Instructions”)

New Indications and Patient Subgroups

This is a core part of lifecycle management.8 The patent on “Molecule X” may expire in 2025. But the patent on “using Molecule X to treat Crohn’s disease” might not expire until 2030. The patent on “using Molecule X to treat patients who are positive for Biomarker Y” (a precision medicine play 76) might last until 2035.

These method-of-use patents can create a “picket fence” of protection that long outlives the original CoM patent.

Dosing Regimens

A related strategy is to patent a specific dosing schedule or amount (e.g., “100 mg administered subcutaneously every three weeks”).50 This is harder than it sounds.

A 2025 Federal Circuit case, ImmunoGen v. Stewart, provides a cautionary tale.77 The court invalidated a dosing patent, finding it obvious. The court’s reasoning is critical: what matters is the “objective reach of the claim,” not the patentee’s “particular motivation”.77 ImmunoGen argued its new dosing regimen was inventive because it solved a previously unknown toxicity problem. The court didn’t care. It found that a person skilled in the art would have been motivated to try that dosing regimen for other reasons, even if they didn’t know about the specific toxicity benefit.

Combination Therapies (The “Alliance”)

Biologic + Small Molecule

As treatment paradigms move toward combination therapies, so has patent strategy.1 This involves patenting the co-administration of a biologic and a small molecule 78 or, even better, a novel co-formulation that combines both in a single vial or syringe.1

The Obviousness Hurdle: Proving “Synergy”

The primary challenge here is, once again, obviousness.79 In fields like oncology and HIV, combination therapy is not just common; it is the standard of care.78 You cannot get a patent for simply adding two known, effective drugs together.

To get a valid patent, your specification must demonstrate synergy.79 You must show that the combination of Drug A + Drug B is more effective than the expected, additive effect of (Drug A) + (Drug B).

The litigation around Entresto (a small-molecule combo, but the principle holds) provides a master-class in claiming strategy.80 The innovators filed broad, foundational claims on the combination of two drugs. Years later, it was discovered that these two drugs, when combined, formed a new, stable co-crystal (a complex). A challenger argued the original patent was invalid because it didn’t describe this complex. The Federal Circuit decisively rejected this argument and upheld the patent.80

The lesson: well-drafted, broad combination claims 80 can “reach through” time to cover future discoveries about how the combination works, providing a powerful and durable shield.80

The Battlefield: Navigating the BPCIA, the “Patent Dance,” and Global Exclusivity

Understanding the assets and the “thicket” is half the battle. The other half is navigating the complex legal and regulatory frameworks that govern the fight. For biologics, this means mastering two very different systems: the BPCIA in the United States and the EMA framework in Europe.

The U.S. Framework: The BPCIA

12-Year Market Exclusivity vs. 4-Year Data Exclusivity

Let’s start with the basics. The BPCIA grants the innovator biologic two key “patent-independent” exclusivity periods 13:

- 12-Year Market Exclusivity: The FDA cannot approve a biosimilar for 12 years from the date of the innovator’s first licensure.13

- 4-Year Data Exclusivity: A biosimilar applicant cannot even file their application (an abbreviated Biologics License Application, or aBLA) with the FDA for 4 years from that first licensure.13

These two clocks run in parallel. And, critically, they are completely separate from the 20-year term of your patents.8 This is why Humira’s 12-year exclusivity (which expired in 2014) was just the beginning of its monopoly.

The “Patent Dance” (The BPCIA Litigation Process)

The BPCIA’s most complex and controversial feature is its unique, multi-step process for resolving patent disputes before a biosimilar launches. This is the so-called “patent dance”.3

An Optional, High-Stakes Waltz

First, the Supreme Court, in Sandoz v. Amgen, ruled that the entire “dance” is optional.84 The biosimilar applicant can choose whether or not to engage. This creates a critical, first-move strategic decision.

The Steps of the Dance

If the biosimilar chooses to dance, it triggers a highly-structured timeline of information exchange 15:

- 20 Days: After the FDA accepts its aBLA, the biosimilar applicant sends a copy (and its manufacturing blueprints) to the innovator.

- 60 Days: The innovator provides a list of all patents it believes are infringed.

- 60 Days: The biosimilar responds with its invalidity and non-infringement arguments.

- 60 Days: The innovator sends a counter-response.

- Negotiation: The parties try to agree on which patents to litigate first.

- Phase I Litigation: The first wave of lawsuits begins on the agreed-upon patents.87

- 180-Day Notice: The biosimilar must give a 180-day “notice of commercial marketing.”

- Phase II Litigation: This notice triggers a second wave of litigation on any patents that were not included in Phase I.87

The Strategic Calculus: To Dance or Not to Dance?

This is the billion-dollar question for the biosimilar.

- Why “Dance”? For certainty. The dance is a “litigation-forcing mechanism”.86 It allows the biosimilar to litigate the patents and “clear the thicket” before launch.15 This provides a clear, de-risked path to market.

- Why “Opt Out”? For secrecy and control. By opting out, the biosimilar avoids the 20-day requirement to hand over its confidential manufacturing process and its detailed legal strategy.82 The innovator’s only remedy is to file a standard (and now “blind”) patent infringement suit.82 The innovator loses control over the timing and scope of the litigation.82 This can be a powerful strategic advantage, though it often means the biosimilar will have to launch “at risk.”

The PTAB Alternative: Attacking Patents at the Source

A savvy biosimilar company rarely fights on just one front. In addition to the BPCIA “dance” in district court, the smart money is on parallel challenges at the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB).87

Challengers can use Inter Partes Review (IPR) and Post-Grant Review (PGR) to attack the validity of the innovator’s patents. The PTAB is a much more favorable venue for challengers 87:

- It’s faster (typically 12-18 months vs. multi-year court battles).

- It’s cheaper (by an order of magnitude).

- It has a lower standard of proof to invalidate a patent (“preponderance of the evidence” vs. “clear and convincing”).

The best-in-class biosimilar strategy is to “dance” in court on the most critical “Type I” patents while simultaneously filing a barrage of IPRs to efficiently kill the weaker, “Type II” patents in the thicket.87

The E.U. Framework: A Different World

Your US-centric BPCIA strategy will be useless in Europe. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) 17 operates on a completely different philosophy.

The “8+2+1” Model

The EU’s exclusivity clock is different from the BPCIA’s 12-year term. The EMA uses an “8+2+1” model 89:

- 8 years of data exclusivity (a biosimilar cannot file its application).

- +2 years of market exclusivity (a biosimilar cannot be marketed).

- +1 year extension available if the innovator gets approval for a significant new therapeutic indication.

- Total: A 10- or 11-year regulatory exclusivity period.

The Critical Difference: No “Patent Linkage”

This is the single most important difference in global pharmaceutical strategy.

In the United States, the BPCIA creates an explicit link between the FDA’s regulatory approval and the innovator’s patent estate. The whole point of the “patent dance” is to resolve patent disputes before the FDA grants final approval.

In the European Union, there is no “patent linkage”.16

The EMA approves biosimilar medicines based on a purely scientific assessment of quality, safety, and efficacy.16 The innovator’s patent portfolio is irrelevant to the EMA’s decision.

This “de-linking” of regulation and IP means a biosimilar can be fully approved by the EMA while the innovator’s patents are still in force. The biosimilar can then launch “at risk,” forcing the innovator to run to court in multiple European countries to sue for patent infringement after the product is already on the market.

This single, fundamental difference in legal philosophy is why the European biosimilar market is far more mature, competitive, and robust than the US market.91 It is also why Humira biosimilars were available to patients in Europe an average of 7.7 years before they were available in the United States.66

Table 3: The BPCIA vs. EMA Regulatory Framework

| Feature | United States (BPCIA) | European Union (EMA) |

| Base Exclusivity Term | 12 years Market Exclusivity 13 | 10 years (8+2) Market Exclusivity 89 |

| Data Exclusivity | 4 years (no aBLA filing) 13 | 8 years (no MAA filing) 89 |

| Exclusivity Extension | 6-month pediatric extension 13 | +1 year for new therapeutic indication 89 |

| Patent Linkage | YES. System (BPCIA “dance”) is designed to resolve patents before FDA approval. 15 | NO. Patent status is completely separate from EMA regulatory approval. [16, 91] |

| Patent Dispute Mechanism | BPCIA “Patent Dance” (pre-launch) [19] | National court litigation (post-launch) 91 |

| Resulting Market | Delayed biosimilar entry; less competition. 91 | Faster biosimilar entry; high competition. 91 |

Case Studies in IP Warfare: The Multi-Billion-Dollar Sagas of Humira and Enbrel

Theory is useful. Real-world case studies are invaluable. To understand how these strategies work in practice, we must look at the two most important biologic patent battles of our time. They offer two very different, but equally successful, playbooks for monopoly extension.

The Archetype: AbbVie’s $200 Billion Humira Fortress

The Strategy: “Quantity has a Quality All Its Own”

AbbVie’s strategy for Humira (adalimumab) is the archetype of the modern patent thicket.22 The core composition-of-matter patent for Humira expired in the United States in 2016.22 By that date, the drug should have faced biosimilar competition.

It didn’t. Not for seven more years.

The Thicket by the Numbers

How did AbbVie do it? They executed a masterful “Type II Thicket” strategy focused on overwhelming quantity.

“All told, AbbVie filed about 250 patent applications for Humira in the U.S., 90% of them following the drug’s 2002 approval, according to the advocacy group Initiative for Medicines, Access & Knowledge. One hundred and thirty have been granted. The strengthened patent shield has stretched AbbVie’s legal monopoly in the U.S. for six years beyond the expiration of Humira’s main patent in 2016.” 22

This is the very definition of a “thicket.” Independent analysis concluded that approximately 80% of these post-approval patents were “duplicative” 23—overlapping, non-inventive “Type II” patents 26 designed to create a legal minefield.26

The Litigation and The Result (ROI)

AbbVie’s goal was not necessarily to win 130+ patent lawsuits. Its goal was to force settlements by making the cost, time, and uncertainty of litigation unpalatable.23

The strategy was a spectacular success. AbbVie asserted dozens of these patents against every single biosimilar challenger.65 Faced with this “numbers game” 23, every single competitor—Amgen, Sandoz, Pfizer, Boehringer Ingelheim—settled. They all agreed to delay their U.S. launch until 2023.22

The Return on Investment for this legal strategy is staggering. Those extra six years of U.S. monopoly (2016-2023) generated billions in revenue. In 2020 alone, Humira’s U.S. net revenue was $16 billion.93

The “patent cliff” is now real. With biosimilars finally on the market, Humira revenues are in freefall.94 But AbbVie’s strategy was never to prevent the cliff; it was to delay it, very, very profitably.

The “Double Patenting” Saga: Amgen’s Enbrel

The Strategy: “Quality over Quantity”

Amgen’s strategy for its own blockbuster, Enbrel (etanercept), was just as effective but surgically different.23 Instead of building a “Type II” thicket of 130 patents, Amgen relied on a handful of “Type I” quality patents.

The Amgen v. Sandoz (Enbrel) Litigation

This is not the Supreme Court Amgen case. This was a separate, decade-long battle over Enbrel.86 Sandoz received FDA approval for its Enbrel biosimilar, Erelzi, in 2016.97 It should have launched immediately.

It is still not on the U.S. market.

Why? Because Amgen blocked them with just two key, late-expiring “Type I” patents: U.S. Patent Nos. 8,063,182 (‘182) and 8,163,522 (‘522).99 These patents covered the etanercept fusion protein itself and the method of making it.

Sandoz (and its licensor, Hoffmann-La Roche) sued, arguing the patents were invalid for obviousness-type double patenting and lack of written description.

The Result (ROI): A Total Victory for Amgen

Amgen didn’t settle. Amgen fought. And Amgen won.

The District Court and, critically, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit upheld the validity of Amgen’s two patents.99

This single victory on just two high-quality patents has blocked Sandoz’s FDA-approved biosimilar from the U.S. market. This legal victory has maintained Amgen’s Enbrel monopoly, potentially resulting in an astonishing 30 years of market exclusivity for the drug.23

These two cases give us two different and proven playbooks. AbbVie’s “Type II” (Quantity) strategy forces settlements. Amgen’s “Type I” (Quality) strategy wins in court. Both are highly effective, multi-billion-dollar strategies.

Table 4: Case Study: Humira vs. Enbrel Thicket Strategy

| Feature | AbbVie (Humira) | Amgen (Enbrel) |

| Core Drug | Adalimumab | Etanercept |

| Primary Thicket Strategy | “Type II” (Quantity): Overwhelm with sheer volume of patents. | “Type I” (Quality): Defend a handful of key, high-quality patents. |

| Est. No. of U.S. Patents | 130+ [22, 101] | ~2 (for the key litigation) [99] |

| Key Patent Types | Duplicative, non-inventive, “Type II” continuation patents 23 | Core “Type I” patents on the fusion protein and manufacturing method |

| Key Legal Tactic | Assert dozens of patents to create a “numbers game” [23, 65] | Defend the validity of two core patents against double-patenting challenge |

| Litigation Outcome | Forced Settlements: All competitors settled for a 2023 launch date. 22 | Won in Court: Federal Circuit affirmed validity of key patents. [99] |

| Resulting Monopoly | Extended monopoly by ~7 years (2016-2023) 22 | Extended monopoly to ~30 years; biosimilar still blocked. 23 |

Turning Data into Domination: The Strategic Role of CI, FTO, and Landscaping

A patent portfolio is a static asset. Patent intelligence is the dynamic, offensive, and defensive use of patent data to win in the market. For R&D, BD, and IP teams, mastering this “data” part of the game is no longer optional.

Competitive Intelligence (CI): Your Early Warning System

Competitive Intelligence (CI) is the offensive use of patent data.102 It’s about systematically collecting and analyzing information about your rivals to anticipate their next move—not next quarter, but next decade.103

Using Patent Databases for R&D Monitoring

A patent application is the earliest public signal of a competitor’s secret R&D pipeline.106 It is often filed years before any clinical trial data is published or a press release is issued.

This is where sophisticated IP teams deploy their secret weapon: patent intelligence platforms. Using a service like DrugPatentWatch, a strategic team doesn’t just “search” for patents; they monitor.107 They set up alerts in their therapeutic areas to track new filings from key competitors.106

This allows them to decode a competitor’s long-term strategy in real-time. By analyzing the claims of these new applications, you can see what they are working on. Are they filing new formulation patents? That signals a “product hop” is coming.108 Are they patenting new manufacturing processes? That signals an effort to reduce costs or improve purity. Are they filing on new combination therapies? That tells you their next-gen clinical trial design. This is your “early warning system”.106

The Originator’s Defense: War-Gaming the Biosimilar Threat

For an innovator, CI is about defending your franchise.109 You use patent intelligence to “war game” the biosimilar threat.105

Using comprehensive patent intelligence tools like DrugPatentWatch, an innovator’s defense team can:

- Map a Challenger’s IP: Conduct exhaustive searches to create a comprehensive map of a potential biosimilar competitor’s entire IP portfolio.110

- Monitor Legal Challenges: Track all relevant legal challenges in real-time, including IPRs filed at the PTAB.110

- Anticipate Moves: This data allows you to anticipate which biosimilar player is approaching launch readiness, what their legal strategy will be, and when they are likely to initiate the “patent dance”.109 This enables a strategic shift from a reactive posture (waiting to be sued) to a proactive one.110

Freedom-to-Operate (FTO): Mapping the Minefield

If CI is offensive, Freedom-to-Operate (FTO) analysis is defensive.111 It is a formal, legal assessment that answers one simple, critical question: “Can we develop and sell our product without being sued for patent infringement?”.111

For a complex biologic, a rigorous FTO process is the single most important R&D investment you can make. It is not a “one-and-done” checkbox; it is a continuous process that must be integrated into the entire R&D lifecycle.112

The FTO Lifecycle

A best-in-class FTO strategy is iterative and timed to key R&D milestones 112:

- Early-Stage FTO (Feasibility): This must occur at the earliest meaningful stage, as soon as the API, indication, and potential formulation are defined.111 This is the cheapest and easiest time to “design around” a blocking patent.

- Iterative FTO (Development): The FTO analysis is not a static report; it’s a living document. It must be updated every time the product evolves. If R&D changes the formulation, you must re-clear the FTO. If the manufacturing team changes a purification step, you must re-clear the FTO.

- Pre-Launch FTO (Final Clearance): This is the final, formal FTO opinion from patent counsel.112 This written opinion is your “insurance policy.” In the U.S., it is the single most powerful shield against a devastating finding of “willful infringement,” which can lead to a court tripling the damage award.

Strategic Mitigation: Navigating the Thicket

An FTO analysis will inevitably find a “blocking” patent. This is not a dead end; it’s a “go-to” decision point. You have three primary paths forward 113:

- Design Around: The best and cheapest option, especially if caught at the Early Stage. Change the formulation. Tweak the purification process. Find a different path.

- License: If the patent is valid and unavoidable, approach the patent holder to negotiate a license.113

- Invalidate: If the patent looks weak, attack it. Proactively file an IPR at the PTAB to invalidate the blocking patent before it can be asserted against you.

FTO for biologics is exponentially more complex than for small molecules. You are not just clearing a molecule. You must clear the entire platform: the sequence 34, the host cell 51, the process 55, the assays 61, the formulation 50, and the device.69 Your FTO analysis must be a core, budgeted part of R&D from day one.

Patent Landscaping: Finding the “White Space”

If CI is the offensive spear and FTO is the defensive shield, Patent Landscaping is the 10,000-foot strategic map of the entire battlefield.115 A landscape analysis shows you who is patenting what, where, and how fast.116

Identifying Opportunities for R&D and M&A

For R&D and BD teams, landscaping is a goldmine for identifying opportunity.

Technology Gaps / “White Space”

Landscaping visually identifies the “patent thickets”—the crowded, contested, high-risk areas of R&D. More importantly, it shows you the “white space”: the valuable, commercially relevant technological areas where your competitors are not patenting.115 This is an objective, data-driven “treasure map” that allows you to direct your precious R&D resources toward less crowded, high-potential fields.

M&A and Licensing Targets

A patent landscape is also a map of who owns what.115 This is invaluable for your business development team. The map clearly identifies the key players, from “Big Pharma” to small, innovative academic labs.117 This allows you to pinpoint the exact companies that own a critical piece of technology, making them perfect targets for a licensing deal 118 or a strategic acquisition.119

The Next Frontier: Patenting AI-Designed Biologics, CAR-T, and Gene Therapies

The strategies that defined the first generation of monoclonal antibodies are already being challenged by the next wave of innovation. Two new frontiers are creating existential questions for IP law: Artificial Intelligence and Cell & Gene Therapy.

The “Human Inventorship” Problem: Patenting AI-Designed Biologics

The AI Revolution in Drug Discovery

Artificial intelligence and machine learning are transforming R&D. AI models are no longer just screening compounds; they are designing them. New platforms can predict complex protein structures 4 and even generate de novo (from scratch) antibody sequences that are optimized for specific targets.120 This is the future of biologic discovery.2

The Thaler v. Vidal Hurdle: AI Cannot Be an “Inventor”

This new power has created a profound legal crisis. Patent law is built on a simple premise: a human “inventor.”

The Federal Circuit, in Thaler v. Vidal, confirmed this, holding that an “inventor” must be a natural person. An AI system, no matter how sophisticated, cannot be listed as an inventor.

What happens when an AI, not a human, designs the new “inventor-less” drug?

The 2024 USPTO Guidance: “Significant Human Contribution”

The U.S. Patent and Trademark Office’s (USPTO) February 2024 guidance is the new rulebook for this frontier.122 The guidance is a compromise: an invention is patentable, if a natural person “contributed significantly” to every claim in the patent.

What does “significant” mean? Merely presenting a problem to an AI (e.g., “find me a drug that binds to PCSK9”) is not enough to make you an inventor. A human must contribute to the conception of the invention.

This means innovator companies must adopt new strategies to protect their AI-designed assets:

- Document Human Input: You must meticulously document how human scientists designed the AI model, curated the training data, or provided specific, inventive prompts that guided the AI’s “conception”.122

- Modify the Output: The most bulletproof strategy is to have human scientists materially modify the AI-generated molecule in the wet lab to improve its performance. This is a clear “significant contribution”.

We are now at the intersection of two landmark rulings. Amgen (enablement) and Thaler (inventorship) are on a collision course. An AI can generate millions of potential antibody candidates. Amgen says you can’t patent that genus without enabling all of them.29 Thaler says you can’t patent any of the individual “species” unless a human “significantly contributed” to their conception.

The only path forward is a new paradigm of human-AI collaboration and, even more importantly, meticulous documentation of that human contribution. Your lab notebook just became more important than your AI model.

The Subject Matter Eligibility Problem: Patenting Cell and Gene Therapies (35 U.S.C. § 101)

The Mayo/Myriad/Alice Framework

The other major legal hurdle is 35 U.S.C. § 101.123 A series of Supreme Court cases (Mayo, Myriad, Alice) established that you cannot patent “laws of nature, natural phenomena, and abstract ideas”.124

For a biologic, this means your claimed invention (a gene, a cell, a protein) must be “markedly different” from what exists in nature.7

The CAR-T and Gene Therapy Challenge

The most advanced therapies in our pipeline—CAR-T cells and gene therapies 2—are dangerously close to this line. Is a gene therapy vector just a “natural” AAV virus sequence combined with a “natural” human gene? Is a CAR-T cell just a “natural” T-cell with a new receptor?

The 2024 REGENXBIO v. Sarepta case is a terrifying warning shot.7 A federal district court invalidated gene therapy patents, finding that the combination of two “natural products” (an A_AV sequence and a non-AAV sequence) in a host cell was not “markedly different” from nature and was therefore ineligible for patent protection under § 101.

The Patent vs. Trade Secret Dilemma

This § 101 risk creates the central strategic dilemma for all cell and gene therapy (CGT) companies.127

The “patent bargain” is a quid pro quo: you disclose your invention to the public, and in exchange, you get a 20-year monopoly. But what happens if the patent is invalid?

Consider this nightmare scenario:

- You spend 10 years and $1 billion perfecting a complex, finicky manufacturing process for your CAR-T therapy.

- You patent this process. Your patent publishes, disclosing your “secret sauce” to the world.

- A competitor challenges your patent. A court, following the Sarepta logic, invalidates your patent under § 101.

- The Result: You have just given away your $1 billion manufacturing process to all your competitors for free.

Because of this existential risk, many CGT companies are now making a radical strategic pivot: they are protecting their most critical manufacturing know-how as a trade secret.10

- Patent: A 20-year monopoly, if it’s valid. But it’s vulnerable to § 101 (eligibility) and § 112 (Amgen) challenges.

- Trade Secret: Protection lasts forever… if you can keep it secret. It’s immune to § 101 and § 112. The risk? If a competitor independently reverse-engineers it, you have zero protection.127

The new consensus is a hybrid model: Patent the “front-end” (the public-facing product, like the novel CAR construct) and protect the “back-end” (the complex, “secret sauce” manufacturing and QC process) as a closely-guarded trade secret.

This is the high-stakes, multi-dimensional chess of modern biologic IP.

Conclusion: Actionable Insights for the Biologic IP Strategist

The era of simple, broad patenting for biologics is over. The Amgen v. Sanofi decision was not an anomaly; it was the exclamation point on a new reality. The strategic center of gravity has shifted definitively away from relying on a single, broad composition-of-matter patent and toward a holistic, multi-layered IP fortress.

Success in this new era requires a radical change in thinking:

- The Thicket is the Strategy: The “thicket” is no longer a pejorative term; it is the strategy. The Humira and Enbrel sagas prove there are two paths to a multi-billion-dollar victory: AbbVie’s “quantity” (Type II) model to force settlements, and Amgen’s “quality” (Type I) model to win in court.

- Process is the New Composition: The “process is the product” doctrine is your most powerful offensive weapon. Thanks to the BPCIA “patent dance,” your process patents (on cell lines, purification, and assays) are the rare weapons your competitors are legally required to hand you infringement evidence for.

- Secondary is Primary: “Secondary” patents on devices, formulations, and dosing are now your primary defense. A product hop to a new, patent-protected, “citrate-free” formulation or a new autoinjector pen can be more effective at blocking biosimilars than your original molecule patent.

- The Law is Fracturing: The new frontiers of AI and cell therapy are creating existential questions that the law cannot yet answer. Thaler forces a re-examination of who an “inventor” is, while Sarepta forces a re-examination of what an “invention” is. In this uncertain environment, the “patent vs. trade secret” decision for your manufacturing process has become the most important, high-stakes choice you will make.

Ultimately, winning in this new gold rush requires a new corporate structure. The old model—where R&D invents, IP patents, and Regulatory files, all in separate silos—is a recipe for failure.

The only successful model is one where R&D, IP, Regulatory, and Business Development are fused into a single, data-driven unit. An IP strategy that is not informed by the “Type I / Type II” thicket model, that does not plan for the BPCIA “dance” vs. “opt-out” choice, and that is not using CI tools to “war game” competitor moves, is not a strategy at all. It’s a liability.

Key Takeaways

- The Amgen Pivot: The Supreme Court’s Amgen v. Sanofi ruling invalidated broad, “functional” genus claims. The new standard is “the more you claim, the more you must enable.” This devalues the broad CoM patent and makes the patent thicket more important, not less.

- Embrace “Process is the Product”: A biologic is defined by its manufacturing process. Your process patents (host cells, purification, QC assays) are a primary, offensive weapon, as the BPCIA “patent dance” forces biosimilars to disclose their infringing processes.

- The “Two Thicket” Model: Understand what you’re building (or fighting). A “Type I Thicket” is a legitimate layering of inventive patents (molecule, process, device). A “Type II Thicket” is a duplicative legal strategy to create litigation friction.

- Secondary Patents are Primary Defenses: The most durable monopolies are now built on “secondary” patents. A patent on a new autoinjector or a “product hop” to a new formulation can be more valuable than the original drug patent.

- Master the “Patent Dance”: The BPCIA “patent dance” is optional. Deciding “to dance” (for certainty) or “opt out” (for secrecy) is a critical, case-by-case strategic choice for biosimilar developers.

- The PTAB is Your Hammer: For biosimilars, the PTAB is a faster, cheaper, and more favorable venue than district court for invalidating “Type II” thicket patents. Fight on two fronts.

- Global Strategy is Not “One-Size-Fits-All”: The U.S. has “patent linkage.” The E.U. does not. This single difference means your U.S. strategy (BPCIA) and E.U. strategy (post-launch litigation) are completely different.

- AI Needs a Human Co-Pilot: AI cannot be an “inventor.” The 2024 USPTO guidance requires “significant human contribution.” You must document how your scientists conceived the invention alongside the AI, or materially modified its output.

- The CAR-T § 101 Risk: The Sarepta case shows a real risk that gene therapies and CAR-T products could be found “patent ineligible” as “products of nature.”

- The Patent vs. Trade Secret Dilemma: Because of the § 101 risk, patenting your complex CAR-T manufacturing process is a gamble. If the patent is invalidated, you’ve given it to the world for free. Protecting it as a trade secret is now a dominant strategy.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. After Amgen v. Sanofi, are broad, functional “genus” claims completely dead for antibodies?

Not completely dead, but they are critically wounded and on life support. The Supreme Court left a narrow door open, stating that a specification might enable a broad genus if it discloses a “general quality… running through the class” that gives it a “peculiar fitness” and reliably teaches a skilled person how to make and use the entire class.

However, in an “unpredictable art” like antibody engineering, proving this is now almost impossible. The “roadmap” Amgen provided was deemed “trial and error”.30 For innovators, the strategy has definitively pivoted: claim by structure. This means patenting the specific amino acid sequences, particularly the six CDRs.33

2. What is the single most effective “secondary” patent to file for a new biologic?

While every asset is different, the two most powerful and durable secondary patent types are Delivery Device Patents and Manufacturing Process Patents.

- Delivery Device: Patenting the autoinjector pen 69 creates a brand new 20-year monopoly that is completely independent of the drug. A biosimilar may have a legal drug, but if they have no legal pen to put it in, they cannot compete.

- Manufacturing Process: These patents are uniquely powerful in the U.S..13 The BPCIA “patent dance” forces a biosimilar applicant to hand over its confidential manufacturing blueprints. This allows the innovator to easily find and prove infringement, turning these patents into offensive spears.

3. As a biosimilar, when does it make strategic sense to “opt out” of the BPCIA patent dance?

You “opt out” of the dance when the strategic value of your secrecy is higher than the value of pre-launch certainty.

- The main reason to “dance” is to get legal certainty by litigating and “clearing” the patents before you launch.15

- The main reason to “opt out” is to deny the innovator two critical pieces of information: 1) Your confidential manufacturing process, which they could use to find infringement of their process patents, and 2) Your detailed invalidity arguments, which gives them a roadmap to your legal strategy.82 By opting out, you force the innovator to sue you “blind,” which can be a significant litigation advantage, even though it means you will likely launch “at risk.”

4. I’m developing a new CAR-T therapy. Should I patent my complex manufacturing process or keep it as a trade secret?

This is now the most critical strategic choice for any cell and gene therapy company.127

- Patent: You get a 20-year monopoly… if the patent is valid. The massive risk is that a court, following the logic of REGENXBIO v. Sarepta 7, could find your process “patent ineligible” under § 101 as a “natural phenomenon.” If your patent is invalidated, you have just publicly disclosed your “secret sauce” for nothing.

- Trade Secret: Protection lasts forever… if you can keep it secret. It is immune to § 101 and § 112 challenges. The risk is that if a competitor independently reverse-engineers your process, you have zero protection.127

- The New Strategy: Most leading companies use a hybrid model. They patent the “front-end” (the public-facing components, like the novel CAR construct) and protect the complex, finicky, “back-end” manufacturing and QC know-how as a trade secret.10

5. How can I use a platform like DrugPatentWatch to predict a competitor’s next move, not just see their last one?

You use it for trend analysis, not just alerts. A single patent filing tells you what a competitor did 18 months ago. A cluster of filings tells you what they are planning to do in the next 3-5 years.

- Set up broad monitoring in your therapeutic area.107 When a key competitor files a cluster of new patents, analyze the claims.

- Are they all for new formulations?108 This is a strong signal of a “product hop” to avoid biosimilar competition.

- Are they all for combination therapies?78 This reveals their next-generation clinical trial strategy.

- Are they for new dosing regimens? This signals a “safer” or “more convenient” product is in the pipeline.

You are not looking at individual patents; you are looking for the pattern in the data. This allows you to “war game” their long-term strategy 105 and proactively adjust your own.

Works cited

- Advancements in the co-formulation of biologic therapeutics – PMC – PubMed Central, accessed November 5, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7426274/

- The Future of Biologics: ‘Bio-Betters’ and the Dawn of Next-Generation Therapies, accessed November 5, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-future-of-biologics-bio-betters-and-the-dawn-of-next-generation-therapies/

- Increasing Transparency in the Biologic Patent Dance – The Regulatory Review, accessed November 5, 2025, https://www.theregreview.org/2025/05/20/wen-increasing-transparency-in-the-biologic-patent-dance/

- Patenting AI: Artificial intelligence and drug discovery – Carpmaels & Ransford – Law Firm, accessed November 5, 2025, https://www.carpmaels.com/patenting-ai-artificial-intelligence-and-drug-discovery/

- The Future of Biopharmaceuticals: Patent Trends to Watch – PatentPC, accessed November 5, 2025, https://patentpc.com/blog/the-future-biopharmaceuticals-patents-trends-to-watch

- Supreme Court Affirms Lack of Enablement for Amgen’s Patent Claims | Alerts and Articles | Insights | Ballard Spahr, accessed November 5, 2025, https://www.ballardspahr.com/insights/alerts-and-articles/2023/05/supreme-court-affirms-lack-of-enablement-for-amgens-patent-claims

- Recent Decision Raises Patent Eligibility Concerns Regarding Certain Gene Therapy-Related Inventions – WilmerHale, accessed November 5, 2025, https://www.wilmerhale.com/en/insights/client-alerts/20240111-recent-decision-raises-patent-eligibility-concerns-regarding-certain-gene-therapy-related-inventions

- The Role of Patents and Regulatory Exclusivities in Drug Pricing | Congress.gov, accessed November 5, 2025, https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/R46679

- Claiming the Products of Biotechnology – Law and Biosciences Blog …, accessed November 5, 2025, https://law.stanford.edu/2011/04/13/claiming-the-products-of-biotechnology/

- Patent Strategies for Small Molecule Drugs versus Biological Drugs – Caldwell Law, accessed November 5, 2025, https://caldwelllaw.com/news/patent-strategies-for-small-molecule-drugs-versus-biological-drugs/

- Securing Innovation: A Comprehensive Guide to Drafting and …, accessed November 5, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/drafting-drug-patent-applications-for-biologic-drugs/

- Regulatory Knowledge Guide for Small Molecules | NIH’s Seed, accessed November 5, 2025, https://seed.nih.gov/sites/default/files/2024-03/Regulatory-Knowledge-Guide-for-Small-Molecules.pdf

- Biologics, Biosimilars and Patents: – I-MAK, accessed November 5, 2025, https://www.i-mak.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Biologics-Biosimilars-Guide_IMAK.pdf

- Up to Par: The Necessity of Quality Assurance and Quality Control for Biologics Research – Beckman Coulter, accessed November 5, 2025, https://www.beckman.com/resources/biologics-drug-discovery-and-development/qa-qc-testing/qa-qc-necessity-in-biologics-research

- How Biosimilars Are Approved and Litigated: Patent Dance Timeline, accessed November 5, 2025, https://www.fr.com/insights/ip-law-essentials/how-biosimilars-approved-litigated-patent-dance-timeline/

- Biosimilar medicines: marketing authorisation – EMA – European Union, accessed November 5, 2025, https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/human-regulatory-overview/marketing-authorisation/biosimilar-medicines-marketing-authorisation

- Biosimilar medicines: Overview – EMA – European Union, accessed November 5, 2025, https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/human-regulatory-overview/biosimilar-medicines-overview

- Predicting patent challenges for small-molecule drugs: A cross-sectional study – PMC, accessed November 5, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11867330/

- THE SUCCESS AND FAILURES OF PATENT DANCE AS SHOWN BY BPCIA LITIGATION CASES FILED AFTER SANDOZ V. AMGEN – University of Pittsburgh Law Review, accessed November 5, 2025, https://lawreview.law.pitt.edu/ojs/lawreview/article/download/874/534/1778

- Differential Legal Protections for Biologics vs Small-Molecule Drugs in the US – PubMed, accessed November 5, 2025, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39585667/

- The Dark Reality of Drug Patent Thickets: Innovation or Exploitation? – DrugPatentWatch, accessed November 5, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-dark-reality-of-drug-patent-thickets-innovation-or-exploitation/

- Two decades and $200 billion: AbbVie’s Humira monopoly nears its …, accessed November 5, 2025, https://www.biopharmadive.com/news/humira-abbvie-biosimilar-competition-monopoly/620516/

- Patent Settlements Are Necessary To Help Combat Patent Thickets, accessed November 5, 2025, https://accessiblemeds.org/resources/blog/patent-settlements-are-necessary-to-help-combat-patent-thickets/

- Frequently Asked Questions on Patents and Exclusivity – FDA, accessed November 5, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/development-approval-process-drugs/frequently-asked-questions-patents-and-exclusivity

- 1 Differential Legal Protections for Biologics vs. Small-Molecule Drugs in the US Olivier J. Wouters, PhD1, accessed November 5, 2025, https://eprints.lse.ac.uk/126180/1/2024.08.03_manuscript.pdf

- Into the Woods: A Biologic Patent Thicket Analysis – Scholarly …, accessed November 5, 2025, https://scholarship.kentlaw.iit.edu/context/ckjip/article/1263/viewcontent/3._Into_the_Woods___Final__2_.pdf

- Amgen Inc. v. Sanofi – Food and Drug Law Institute (FDLI), accessed November 5, 2025, https://www.fdli.org/2024/05/amgen-inc-v-sanofi/

- Impact Of Amgen Inc. v. Sanofi On Patenting Antibody Based Therapeutics – American Bar Association, accessed November 5, 2025, https://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/publications/Jurimetrics/winter-2024/impact-of-amgen-inc-v-sanofi-on-patenting-antibody-based-therapeutics.pdf

- AI and Enablement After Amgen v. Sanofi: Implications for Life Sciences Patents | Insights, accessed November 5, 2025, https://www.venable.com/insights/publications/2025/10/ai-and-enablement-after-amgen-v-sanofi

- 21-757 Amgen Inc. v. Sanofi (05/18/23) – Supreme Court, accessed November 5, 2025, https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/22pdf/21-757_k5g1.pdf

- Post-Amgen v. Sanofi: What the Enablement Ruling Means for Your …, accessed November 5, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/post-amgen-v-sanofi-what-the-enablement-ruling-means-for-your-biologic-patent-strategy/

- 2164-The Enablement Requirement – USPTO, accessed November 5, 2025, https://www.uspto.gov/web/offices/pac/mpep/s2164.html

- Patentability Considerations for Antibody-Related Inventions – BioPharm International, accessed November 5, 2025, https://www.biopharminternational.com/view/patentability-considerations-for-antibody-related-inventions

- How to Patent Biologics in Clinical Development – Collier Legal, accessed November 5, 2025, https://collierlegaloh.com/how-to-patent-biologics-in-clinical-development/