Executive Summary

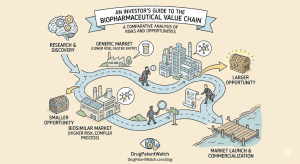

The global pharmaceutical market presents two primary avenues for investors seeking to capitalize on the expiration of brand-name drug monopolies: generic drugs and biosimilars. While both offer lower-cost alternatives to originator products and are foundational to healthcare cost-containment strategies, they represent fundamentally different investment classes with non-interchangeable risk profiles, development pathways, and commercial dynamics. Mistaking one for the other is a critical strategic error. This report provides a comprehensive comparative analysis for sophisticated investors, dissecting the scientific, regulatory, legal, and commercial distinctions between these two sectors to illuminate their unique investment theses.

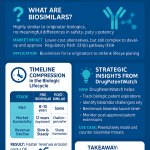

The core divergence stems from molecular complexity. Generic drugs are identical, chemically synthesized copies of small-molecule medicines. Their development is a low-cost, predictable manufacturing exercise, costing $1-5 million over approximately two years. This low barrier to entry fosters a hyper-competitive market characterized by a rapid and severe “race to the bottom” on price. Consequently, the generic investment thesis is a high-volume, cost-efficiency play, where success is dictated by operational scale, supply chain mastery, and the strategic pursuit of the lucrative 180-day market exclusivity for first-to-file patent challengers. The global generic market is a mature behemoth, valued at approximately $450 billion, with stable, mid-single-digit growth projected at a Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) of around 5.04% through 2034.1

In stark contrast, biosimilars are “highly similar” versions of large, complex biologic drugs produced in living cells. Exact replication is impossible, necessitating a high-cost, high-risk, and lengthy development process akin to novel drug R&D, costing $100-300 million over six to nine years. This formidable barrier to entry limits competition, allowing for more modest price discounts and the potential for durable, brand-like margins. The biosimilar investment thesis is a high-stakes bet on scientific execution, regulatory navigation, and legal acumen to capture a share of the rapidly expanding biologics market. The biosimilar market, while smaller at roughly $34 billion, is in a high-growth phase, with a projected CAGR of 17.78%, forecasted to reach approximately $176 billion by 2034.2

This report analyzes the key drivers of value and risk in each sector. For generics, the primary risks are commercial: extreme price erosion, supply chain fragility, and disruptive government policies like the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA). For biosimilars, the primary risks are upstream: prohibitive development costs, complex manufacturing hurdles, clinical trial failures, and navigating dense “patent thickets.”

Ultimately, this analysis concludes that investors must deploy entirely different frameworks for asset evaluation in each space. Generic opportunities are best assessed through the lens of operational efficiency and legal strategy to capture first-mover advantages. Biosimilar opportunities demand deep diligence into a company’s scientific capabilities, manufacturing prowess, and ability to fund a protracted, high-risk development and litigation cycle. As the pharmaceutical industry confronts an unprecedented patent cliff for blockbuster biologics between 2025 and 2030, understanding these fundamental distinctions will be paramount for successful capital allocation in the biopharmaceutical value chain.

I. The Scientific and Economic Foundations: Why Generics and Biosimilars Are Fundamentally Different Investment Classes

To comprehend the profound differences in the investment profiles of generic drugs and biosimilars, one must first grasp the fundamental scientific distinctions at the molecular level. These differences in size, structure, and manufacturing are not academic details; they are the ultimate upstream determinants that dictate every downstream variable an investor must consider, from regulatory pathways and development costs to competitive dynamics and profit potential. The entire investment thesis for each asset class can be traced back to its molecular architecture.

Section 1.1: The Small-Molecule Paradigm – The Generic Drug Model

Molecular Simplicity and Chemical Synthesis

Generic drugs are therapeutic alternatives to brand-name drugs that are composed of small, chemically synthesized molecules.3 These molecules typically have a low molecular weight, generally under 900 Daltons, and are comprised of a relatively small number of atoms—aspirin, for instance, has just 21.5 Their structure is simple, stable, and well-defined.8

The manufacturing process for a small-molecule drug is a predictable and highly reproducible chemical synthesis.9 This process allows manufacturers to create an active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) that is, for all practical purposes, identical from one batch to the next.10 This consistency and replicability form the scientific and economic cornerstone of the generic drug industry. Because the final product can be proven to be an exact copy, the path to market is significantly simplified.

The Concept of Bioequivalence: An Identical Copy

The regulatory standard for generic drug approval in both the United States and Europe is “bioequivalence”.11 A generic drug is considered bioequivalent to its brand-name counterpart, or reference listed drug (RLD), if it contains the identical active ingredient and is proven to be absorbed into the bloodstream at the same rate and to the same extent.12 The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) require generic manufacturers to demonstrate that their product has the same dosage form, strength, route of administration, quality, safety, and intended use as the original.14

This standard is met not through extensive new clinical trials in patients, but through straightforward pharmacokinetic studies, typically involving 24 to 36 healthy volunteers, which measure the concentration of the drug in the blood over time.13 The FDA allows for a slight, medically unimportant level of natural variability, just as exists between different batches of the brand-name drug itself.11 However, the core principle is identity. Minor differences are permitted only in inactive ingredients, known as excipients (such as fillers, dyes, or flavorings), and these must be shown to have no effect on the drug’s performance, safety, or effectiveness.3 Once approved, a generic is considered therapeutically equivalent and can be automatically substituted for the brand-name drug by a pharmacist, a critical factor in driving market uptake.15

Section 1.2: The Large-Molecule Revolution – The Biologic and Biosimilar Model

Molecular Complexity and Manufacturing in Living Systems

Biologics, and by extension their biosimilar versions, represent a fundamentally different class of medicine. They are large, complex molecules, often 200 to 1,000 times the size of small-molecule drugs, and can be composed of tens of thousands of atoms.6 Unlike generics, which are created through chemical synthesis in a lab, biologics are produced by or derived from living organisms, such as genetically engineered bacteria, yeast, or mammalian cells.8 These products include monoclonal antibodies, vaccines, and cell therapies used to treat complex conditions like cancer and autoimmune diseases.23

The manufacturing process is not a simple chemical reaction but a highly sensitive and complex biological process. It involves cultivating living cells under tightly controlled conditions, followed by intricate multi-step processes to extract and purify the desired protein.7 The final product’s three-dimensional structure is critical to its function, and this structure is highly sensitive to even minor changes in the manufacturing environment.6

The “Highly Similar” Standard: Navigating Inherent Variability

The living systems used to produce biologics introduce a crucial factor: inherent variability. It is scientifically impossible to create an exact copy of a complex biologic molecule.10 Minor variations in the protein structure, such as glycosylation patterns, are a natural and expected feature, not only between a reference biologic and a biosimilar but also between different manufacturing batches of the originator biologic itself.10

Consequently, the regulatory standard for a follow-on biologic cannot be “identity” or “bioequivalence.” Instead, regulatory bodies like the FDA and EMA have established a more nuanced standard: a biosimilar must be “highly similar” to its reference product, with no “clinically meaningful differences” in terms of safety, purity, and potency.22 This subtle but critical distinction—”similar” versus “identical”—is the source of the vast scientific, regulatory, and commercial complexities that define the biosimilar market and differentiate it from the generic space. Proving “high similarity” requires a far more extensive and costly evidence package than proving “bioequivalence.”

Naming Conventions as a Signal of Difference

The regulatory distinction between generics and biosimilars is reinforced by their naming conventions. Generic drugs share the same International Nonproprietary Name (INN) or United States Adopted Name (USAN) as their brand-name counterparts, reinforcing the concept of identity.3 For example, the generic for Lipitor is simply atorvastatin.

In the U.S., however, the FDA requires that biosimilars be given a nonproprietary name that includes the core name of the reference product’s active ingredient plus a unique, meaningless four-letter suffix.33 For example, a biosimilar to Amgen’s Neupogen (filgrastim) is Sandoz’s Zarxio (filgrastim-sndz). This policy was designed primarily to facilitate pharmacovigilance—making it easier to track adverse events to a specific manufacturer’s product.33

However, this decision is not merely an administrative detail; it is a powerful market signal that institutionalizes the concept of “difference.” For physicians and patients accustomed to the generic model where the name signifies identity, the distinct name of a biosimilar can create uncertainty and a perception of inferiority, even though the FDA has determined there are no clinically meaningful differences.34 This creates a psychological barrier to adoption that does not exist for generics, adding a significant commercialization risk that must be factored into investment models. Overcoming this “confidence gap” requires biosimilar manufacturers to invest in education and marketing efforts that are unnecessary for generic producers.

Section 1.3: Economic Implications of the Scientific Divide

The scientific chasm between small-molecule generics and large-molecule biosimilars translates directly into a vast economic divide, shaping their respective investment profiles through profound disparities in development costs, timelines, and probabilities of success.

Disparities in Development Costs, Timelines, and Success Probabilities

The economic implications of these scientific realities are stark and represent the first layer of an investor’s risk assessment.

- Generics: The development pathway for a generic drug is relatively straightforward, fast, and inexpensive. Because manufacturers can rely on the brand’s established safety and efficacy data, the process primarily involves demonstrating bioequivalence and manufacturing competence. This typically costs between $1 million and $5 million and can be completed in approximately two years.4 Once a viable product target is selected and patent hurdles are assessed, the technical and regulatory probability of success is very high, often exceeding 90%.

- Biosimilars: Developing a biosimilar is a monumental undertaking, far more comparable to developing a new drug than a generic. The need to independently develop a manufacturing process and then prove “high similarity” through a comprehensive “totality of the evidence” approach requires massive capital investment and a long-term commitment. Development costs range from $100 million to $300 million and take six to nine years to complete.4 This includes extensive spending on process development, analytical characterization, and, crucially, clinical trials—which can account for over half the total cost.39 The probability of success, while higher than for a novel biologic, is significantly lower than for a generic. An analysis by McKinsey found an average success rate of just 53% across U.S., European, and Japanese markets, though it noted many failures were for strategic rather than clinical reasons.40

Initial Insights into Divergent Pricing Power and Margin Potential

This vast disparity in upfront investment and risk directly dictates the commercial strategy and potential for profitability. A generic manufacturer, with minimal sunk costs, can afford to enter the market with an aggressive pricing strategy, often offering discounts of 80% or more to rapidly capture volume.41 This strategy is viable because the low barrier to entry ensures numerous competitors will quickly follow, turning the market into a high-volume, low-margin commodity business.

A biosimilar manufacturer, needing to recoup a nine-figure investment, cannot compete in the same way. It must launch with a more modest price discount, typically in the range of 15% to 50% relative to the originator biologic’s price.44 The high barriers to entry—technical, financial, and regulatory—naturally limit the number of competitors, creating a more oligopolistic market structure. This allows for more rational pricing and the potential for higher, more durable profit margins, provided the manufacturer can successfully navigate the development gauntlet and achieve significant market uptake.

| Characteristic | Generic Drugs | Biosimilars |

| Core Product | Small-molecule, chemical synthesis 3 | Large-molecule, from living systems 4 |

| Size & Complexity | Low molecular weight, simple structure 5 | High molecular weight, complex 3D structure 21 |

| Manufacturing | Reproducible chemical process 9 | Sensitive biological process with inherent variability 10 |

| Regulatory Standard | Bioequivalent / Identical Active Ingredient 11 | Highly Similar / No Clinically Meaningful Differences 22 |

| Naming Convention (U.S.) | Shared Nonproprietary Name (INN/USAN) 3 | Core Name + Unique 4-Letter Suffix 33 |

| Development Cost | $1-5 Million 4 | $100-300 Million 37 |

| Development Timeline | ~2 Years 4 | 6-9 Years 39 |

II. The Rules of Engagement: Navigating Disparate Regulatory and Patent Landscapes

The scientific differences between generics and biosimilars are codified into distinct legal and regulatory frameworks that create fundamentally different pathways to market. These rules of engagement, established by landmark legislation in the U.S. and Europe, define the timelines, costs, risks, and incentives associated with market entry. For an investor, a deep understanding of these disparate systems is crucial for modeling time to market, litigation risk, and the potential for exclusivity-driven returns.

Section 2.1: The Generic Pathway – Speed and Predictability

The Hatch-Waxman Act

The modern generic drug industry in the United States was born from the Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984, commonly known as the Hatch-Waxman Act.50 This legislation created a grand bargain: it streamlined the approval process for generic drugs to foster price competition while offering brand-name manufacturers incentives for innovation, such as patent term extensions to compensate for time lost during the FDA review process.13 The act established a clear, predictable, and rules-based system that has successfully balanced these competing interests, leading to a market where generics now account for over 90% of prescriptions filled in the U.S..50

The ANDA Process

The cornerstone of the Hatch-Waxman Act is the Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) pathway.50 The process is “abbreviated” because it allows a generic manufacturer to rely on the FDA’s previous finding that the brand-name reference drug is safe and effective.12 This critical provision eliminates the need for generic companies to conduct their own costly and duplicative preclinical and clinical trials, which was a major barrier to entry before 1984.13 Instead, the ANDA submission focuses on demonstrating two key things: first, that the generic drug is bioequivalent to the reference drug, and second, that the company can manufacture the drug consistently and to the same high-quality standards as the brand manufacturer.12 This streamlined process dramatically reduces the time, cost, and risk of bringing a generic to market.

EU Regulatory Pathways

The European Union has established a parallel set of abbreviated pathways for generic medicines, governed by Directive 2001/83/EC.58 While the structure differs, the underlying principle is the same: to provide an expedited route to market based on demonstrating sameness to an authorized reference medicine.16 Companies can seek approval through several routes, including the Centralised Procedure (for approval across the entire EU), the Decentralised Procedure, or the Mutual Recognition Procedure (where approval in one member state is recognized by others).58 Regardless of the specific path, the core requirement is to prove that the generic has the same qualitative and quantitative composition and is bioequivalent to the reference product, thus avoiding the need for new efficacy and safety trials.58

Section 2.2: The Biosimilar Gauntlet – Complexity and Uncertainty

The BPCIA

The regulatory framework for biosimilars in the U.S. was established much later, through the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA) of 2009, which was passed as part of the Affordable Care Act.61 Reflecting the greater scientific complexity of biologics, the BPCIA is a more intricate and cautious piece of legislation than Hatch-Waxman. A key provision is a significantly longer period of market exclusivity for innovator biologics: 12 years of data exclusivity from the date of first licensure, compared to just five years for new small-molecule drugs.61 This extended protection acknowledges the higher cost and risk associated with developing novel biologics.

The 351(k) Pathway

The BPCIA created an abbreviated licensure pathway for biosimilars under section 351(k) of the Public Health Service Act.66 However, this pathway is far more demanding than the ANDA process for generics. It requires the biosimilar applicant to demonstrate biosimilarity through a “totality of the evidence” approach.69 This means the FDA evaluates a comprehensive data package that must include:

- Analytical Studies: Extensive, state-of-the-art laboratory tests comparing the structural and functional characteristics of the biosimilar and the reference product to demonstrate they are “highly similar”.69

- Animal Studies: Data from animal studies, including assessments of toxicity.69

- Clinical Studies: A clinical study or studies sufficient to demonstrate safety, purity, and potency. This typically includes comparative pharmacokinetic (PK) and pharmacodynamic (PD) studies and an assessment of immunogenicity (the potential to provoke an immune response).69 In many cases, especially for complex molecules like monoclonal antibodies, the FDA also requires at least one large, comparative clinical efficacy trial in patients to confirm there are no clinically meaningful differences.66

The FDA retains the discretion to waive certain requirements if it deems them unnecessary, which introduces an element of regulatory uncertainty into the development process.40 This extensive data requirement is the primary driver of the high cost and long timeline of biosimilar development.

EU Regulatory Framework

The EMA was a global pioneer in this field, establishing the first comprehensive regulatory pathway for biosimilars in 2005 and approving the first biosimilar in 2006, nearly a decade before the U.S..32 The EU’s framework is widely regarded as a mature, science-based, and predictable system that has influenced regulatory standards worldwide.32 Like the FDA, the EMA requires a robust comparability exercise to demonstrate high similarity in quality, safety, and efficacy, allowing for a reduction in the nonclinical and clinical data required compared to an originator biologic.32

Section 2.3: The Patent Battleground

The process of resolving patent disputes is a critical and highly divergent aspect of the generic and biosimilar pathways, with profound implications for investment risk and strategy.

Generic Litigation: Paragraph IV Challenges

Under the Hatch-Waxman Act, when a generic company files an ANDA, it must make a certification for each patent listed by the brand manufacturer in the FDA’s “Orange Book”.72 A “Paragraph IV” certification is a declaration that the generic company believes the brand’s patent is invalid, unenforceable, or will not be infringed by the generic product.73 This filing is an act of patent challenge and typically triggers a lawsuit from the brand manufacturer within 45 days.75

The filing of such a lawsuit initiates an automatic 30-month stay of FDA approval for the ANDA, providing a defined period for the parties to litigate the patent dispute.53 The most crucial aspect of this system is the incentive it provides: the first generic applicant to file a substantially complete ANDA with a Paragraph IV certification is eligible for a

180-day period of market exclusivity upon approval.72 During this period, the FDA cannot approve any other generic versions of the same drug. This “first-to-file” (FTF) exclusivity is the single most powerful economic driver in the generic industry. It transforms patent litigation from a simple cost of doing business into a high-stakes, offensive investment strategy. The potential to capture six months of duopoly or even monopoly profits on a blockbuster drug can be worth hundreds of millions of dollars, justifying the significant expense and risk of litigation.75

Biosimilar Litigation: The “Patent Dance” and “Patent Thickets”

The BPCIA established a very different, and far more complex, system for resolving patent disputes. Innovator biologics are often protected by a large and overlapping portfolio of patents—sometimes numbering in the hundreds—that cover not just the molecule itself but also manufacturing processes, formulations, methods of use, and delivery devices. This strategy, known as creating a “patent thicket,” is designed to be a formidable barrier to entry, making it incredibly costly and time-consuming for a biosimilar developer to clear a path to market.80

To manage this complexity, the BPCIA created a unique, multi-step process of pre-litigation information exchange colloquially known as the “patent dance”.83 This process involves a series of timed disclosures and negotiations between the biosimilar applicant and the reference product sponsor to identify the patents that will be litigated.86 However, in a landmark Supreme Court decision (

Sandoz v. Amgen), it was determined that this dance is optional for the biosimilar applicant.83

This optionality, combined with the sheer complexity of the patent landscape, creates a highly uncertain and protracted legal risk. Unlike the generic pathway, there is no automatic 30-month stay of approval, nor is there a statutory market exclusivity period awarded to the first biosimilar that successfully litigates a patent.84 The absence of an incentive equivalent to the 180-day exclusivity means that for biosimilar developers, patent litigation is a purely defensive maneuver—a massive cost center and a significant risk with no direct, litigation-driven upside. This fundamentally alters the investment calculus, shifting the focus from value creation through litigation to one of risk mitigation and cost control.

Section 2.4: The Interchangeability Factor – A Uniquely American Wrinkle

Regulatory Definition and Requirements

A further layer of complexity in the U.S. biosimilar market is the regulatory designation of “interchangeability”.88 An interchangeable biosimilar is one that has met additional requirements to demonstrate that it can be expected to produce the same clinical result as the reference product in any given patient. Crucially, this designation allows a pharmacist to substitute the interchangeable biosimilar for the prescribed reference product without needing to consult the prescriber, subject to state laws—a practice mirroring that of generic drugs.90

Historically, achieving this designation required biosimilar manufacturers to conduct additional, expensive, and time-consuming clinical “switching studies,” in which patients are alternated between the reference product and the biosimilar to show that switching poses no additional risk.88 This high bar has meant that very few biosimilars have sought or achieved interchangeable status. However, in a potentially game-changing move, the FDA has recently proposed draft guidance that would eliminate the need for these switching studies, relying instead on other analytical data.94 This signals a regulatory convergence with the long-held European view that all approved biosimilars are, from a scientific standpoint, interchangeable.32

Impact on Stakeholder Perceptions

The existence of this two-tiered system—”biosimilar” and “interchangeable”—has created significant confusion in the U.S. market. Many physicians, pharmacists, and patients incorrectly perceive the interchangeable designation as a marker of higher quality or superior safety, even though the FDA has stated that both types of products meet the same high standard of biosimilarity.90 This misperception can heavily influence prescribing habits, with some physicians being much more comfortable with a product that has the interchangeable seal of approval.95

Investment Implications

From an investment perspective, the interchangeability designation presents a strategic dilemma. The central question is whether the substantial investment required to achieve the designation—even if switching studies are no longer needed—will generate a sufficient return on investment through faster or greater market uptake. The value is highly context-dependent. For physician-administered oncology biosimilars, which have seen high uptake without the designation, it may be unnecessary.95 However, for self-administered, pharmacy-dispensed products for chronic conditions (such as adalimumab biosimilars), where automatic substitution at the pharmacy is a key lever for capturing market share, the designation could be critical. The FDA’s potential rule change could dramatically lower the cost-benefit barrier, possibly transforming interchangeability from a niche strategy into a competitive necessity for certain product classes.

| Feature | Generics (Hatch-Waxman Act) | Biosimilars (BPCIA) |

| Governing Law | Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984 50 | Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act of 2009 65 |

| Approval Application | Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) 54 | 351(k) Biologics License Application (BLA) 67 |

| Innovator Data Exclusivity | 5 years (New Chemical Entity) 99 | 12 years 61 |

| Patent Information Source | Orange Book 50 | “Patent Dance” exchange 83 |

| Litigation Trigger | Paragraph IV Certification 74 | Information Exchange / Notice of Commercial Marketing 83 |

| Automatic Stay of Approval | 30 months 53 | None 84 |

| Key Market Incentive | 180-day First-to-File (FTF) Exclusivity 72 | None (First interchangeable gets 1 year, but this is rare) 61 |

| Substitution Standard | Automatic (Therapeutic Equivalence) 15 | Requires Interchangeable Designation for pharmacy-level substitution 89 |

III. Market Dynamics and Competitive Intensity: A Tale of Two Markets

The scientific and regulatory differences between generics and biosimilars give rise to two distinct market environments, each with its own size, growth trajectory, pricing behavior, and adoption hurdles. Investors must analyze these market dynamics to accurately forecast revenue streams, model profitability, and understand the competitive pressures that will shape the return on their capital.

Section 3.1: Market Size and Growth Projections

The Mature Generic Market: A Stable, High-Volume Behemoth

The global generic drugs market is a mature and massive industry. Valuations for 2023-2024 place the market size between $425 billion and $468 billion.1 Despite its large base, the market is projected to grow at a stable but modest pace. Forecasts indicate a Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) in the range of 5% to 8%, with the market expected to reach approximately $728 billion to $916 billion by the early 2030s.1

The defining characteristic of the generic market is its volume-driven nature. In the U.S., generic drugs account for the vast majority of prescriptions dispensed—around 90%—yet they represent a disproportionately small fraction of total prescription drug spending, typically between 13% and 18%.46 This underscores the fundamental business model: high volume and low margin. The primary growth drivers are the ongoing patent expirations of small-molecule drugs and increasing healthcare cost-containment pressures from governments and payers worldwide.1

The High-Growth Biosimilar Market: Capturing the Biologic Wave

In contrast, the biosimilar market is smaller but is experiencing explosive, dynamic growth. Global market size estimates for 2024 range from approximately $26 billion to $36 billion.2 The growth forecasts are exceptionally strong, with projected CAGRs ranging from 15% to as high as 24%, depending on the source and forecast period.2 This rapid expansion is expected to propel the market to a value of $100 billion to $185 billion by the early 2030s.2

This high growth rate is fueled by two main factors. First, biologics represent the fastest-growing segment of the overall pharmaceutical market, now accounting for over 40% of total pharma spending in Europe and the U.S..5 As these expensive products come off patent, they create a massive revenue pool for biosimilars to capture. Second, the upcoming “patent cliff” for biologics between 2025 and 2030 is unprecedented in scale, opening up tens of billions of dollars in annual sales to competition.112

Section 3.2: The Price Erosion Curve

The pricing dynamics upon market entry are perhaps the most dramatic illustration of the difference between the two sectors and are a primary determinant of investment returns.

Generics: The Precipitous “Race to the Bottom”

The generic market is defined by severe and immediate price erosion. Upon the entry of the first generic competitor, the price of the drug typically falls by 30% to 40% compared to the brand price.41 This decline accelerates dramatically as more competitors enter the market. With two competitors, the price reduction can exceed 50%. In markets with six or more generic manufacturers, prices can plummet by a staggering 80% to 95%.3

This “race to the bottom” is a direct result of the low barriers to entry and the product’s status as a commodity. Since all approved generics are considered therapeutically identical, competition is based almost exclusively on price. This dynamic makes long-term profitability on any single, simple generic product extremely challenging and is a primary risk for investors in this space.

Biosimilars: A More Gradual Decline and the Potential for Sustained Margins

The price erosion curve for biosimilars is markedly different. Due to the high development costs and manufacturing complexity, biosimilar manufacturers cannot afford the deep discounts seen with generics. Initial launch prices are typically 15% to 50% lower than the price of the reference biologic.44

While prices do decline further as more biosimilar competitors enter a given market, the erosion is far more gradual and less severe than for small-molecule generics.100 The high barriers to entry naturally limit the number of competitors, preventing the hyper-competitive, commodity-like environment of the generic market. This more rational pricing dynamic allows for the potential of higher and more durable profit margins over the product lifecycle, which is a key component of the biosimilar investment thesis.

Section 3.3: Market Adoption and Stakeholder Influence

Beyond pricing, the path to capturing market share is vastly different for generics and biosimilars, heavily influenced by the perceptions and financial incentives of key healthcare stakeholders.

Payer & PBM Dynamics: The “Rebate Wall” and Formulary Strategy

For generics, market adoption is typically swift and seamless. Automatic substitution laws in many jurisdictions mean that once a generic is available, it rapidly displaces the brand-name drug at the pharmacy counter.116

For biosimilars, the path is fraught with obstacles, primarily constructed by Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs) and payers. A major barrier to biosimilar uptake is the “rebate wall”.117 Brand biologic manufacturers often provide large, confidential rebates to PBMs in exchange for maintaining exclusive or preferred status on their drug formularies. A biosimilar, even with a lower list price, may offer a smaller total rebate to the PBM, creating a perverse financial incentive for the PBM to favor the higher-priced brand product.48 This dynamic can significantly slow or even block biosimilar adoption, particularly for pharmacy-dispensed drugs.

However, there are signs of a potential market inflection. In a high-profile move, major PBMs like CVS Caremark have begun to remove the blockbuster biologic Humira from their formularies in favor of its biosimilars.121 This demonstrates that as biosimilar competition intensifies and savings potential grows, PBMs can and will shift their strategies, becoming powerful drivers of adoption rather than barriers.

Physician and Patient Perspectives: Overcoming the Confidence Gap

The trust of prescribers and patients is another critical variable. For generics, decades of use have built a high level of confidence; they are widely accepted as being identical to the brand.123

Biosimilars, however, must overcome a significant “confidence gap.” The regulatory language of “highly similar” but not “identical,” combined with distinct naming conventions, can create hesitancy among physicians and patients.96 Surveys have shown that while physicians are generally confident in biosimilars, they are often reluctant to switch a patient who is stable on a reference biologic, fearing potential differences in efficacy or side effects.96 This is particularly true in chronic conditions like rheumatology, where treatment success can be hard-won.95 This prescriber and patient reluctance represents a major commercial hurdle that requires significant investment in education, clinical data, and real-world evidence to overcome. The “interchangeable” designation is intended to bridge this gap, but its impact has been mixed and created its own layer of confusion.92

This dynamic reveals that the biosimilar market is not a single entity but a collection of distinct micro-markets. Adoption curves are heavily influenced by the specific therapeutic area and site of care. For instance, in oncology, where biologics like bevacizumab and trastuzumab are administered in a hospital or clinic setting, uptake of biosimilars has been rapid and high, often exceeding 80%.115 This is driven by centralized institutional purchasing decisions, which are highly sensitive to cost, and by the quick endorsement of these products by influential professional societies like the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO).95 In this environment, the lack of an interchangeable designation has been largely irrelevant. In contrast, self-administered, pharmacy-dispensed biosimilars for chronic autoimmune conditions, such as those for Humira, face the much stronger headwinds of the PBM rebate wall and greater patient and physician hesitancy about switching a stable therapy. Therefore, an investor cannot apply a single market uptake model to all biosimilar assets; the investment case must be rigorously tailored to the specific drug’s reimbursement channel and clinical context.

Reimbursement Policies

Reimbursement policies, particularly within Medicare Part B in the U.S. (which covers physician-administered drugs), create different incentives. For a brand drug and its generics, Medicare often uses a single billing code and calculates a bundled reimbursement based on the weighted average sales price (ASP) of all products.127 As low-priced generics enter, the ASP for the entire group falls, creating a strong financial incentive for providers to dispense the lowest-cost option to maximize their margin.

Initially, CMS applied a similar bundled approach to biosimilars. However, the policy was changed to provide separate billing codes and reimbursement rates for each biosimilar and the reference biologic, each paid at 106% of its own ASP.128 This can create a disincentive to use a lower-priced biosimilar, as the 6% add-on payment is larger in absolute dollar terms for the higher-priced originator product, a phenomenon that can slow adoption.48

The extreme price erosion in the generic market is also creating a “profitability paradox.” The very mechanism that delivers immense savings to the healthcare system—intense price competition—is simultaneously making the production of many essential, low-cost medicines economically unsustainable for manufacturers.41 This relentless downward pressure on margins forces companies to exit less profitable markets or aggressively cut costs, often by eliminating supply chain redundancies and consolidating manufacturing in a few low-cost overseas locations.118 This leads to market concentration, where only a handful of highly scaled manufacturers remain for a given product.114 The consequence is a fragile supply chain; if one of these few suppliers experiences a quality issue or a plant shutdown, there is often no alternative capacity to fill the gap, leading directly to widespread drug shortages.118 Thus, the greatest strength of the generic model is also the source of its greatest systemic risk, posing a long-term challenge to the industry’s sustainability and reliability.

IV. Investment Analysis: A Deep Dive into Risks and Opportunities

Synthesizing the scientific, regulatory, and market realities allows for the construction of distinct investment theses for generics and biosimilars. The risk profiles of these two asset classes are effectively inverted. For generics, the primary risks are commercial and manifest after a successful launch. For biosimilars, the overwhelming risks are technical, regulatory, and legal, occurring before a product ever reaches the market. An investor’s due diligence and risk assessment must reflect this fundamental inversion.

Section 4.1: The Generic Investment Thesis

The generic investment thesis is a play on operational efficiency, legal acuity, and speed to market. The goal is to navigate a predictable but hyper-competitive landscape to capture transient but significant profits.

Opportunities

- The Strategic Value of 180-Day Exclusivity: The 180-day market exclusivity for the first-to-file (FTF) generic patent challenger is the primary mechanism for generating outsized returns in the small-molecule space.72 This period of duopoly (against the brand) or monopoly (if the brand launches an authorized generic) allows the FTF generic to capture substantial market share at a price point well above the eventual commoditized level.77 The entire investment case for developing a specific generic often hinges on the calculated probability of securing this lucrative exclusivity period. In 2020, generics launched with 180-day exclusivity saved the healthcare system nearly $20 billion.79

- Identifying Profitable Niches: While the market for simple oral solid generics is largely commoditized, significant opportunities remain in more complex product categories. These “complex generics,” such as sterile injectables, transdermal patches, and inhalation products, have higher technical and manufacturing barriers to entry.132 These barriers naturally limit the number of potential competitors, leading to a less severe price erosion curve and more sustainable profitability.134

- Leveraging Patent Intelligence for First-to-File Advantage: A core competency for successful generic firms is the use of sophisticated patent intelligence to identify brand drugs protected by weak or narrow patents. By conducting thorough prior art searches and validity analyses, companies can identify promising targets for a Paragraph IV challenge.74 An investment in a generic company is often an investment in its legal and analytical ability to consistently identify these opportunities and be the first to file a successful ANDA, thereby winning the 180-day prize.136

Risks

- Extreme Margin Compression: The primary and most certain risk in the generic market is the rapid and severe price erosion that follows the entry of multiple competitors. This dynamic compresses gross margins to razor-thin levels, making long-term profitability on any single product highly challenging and threatening the viability of producing many essential medicines.41

- Supply Chain & Quality Crises: The industry’s intense price pressure has led to a heavy concentration of API and finished drug manufacturing in a few low-cost regions, primarily India and China.41 This creates significant geopolitical and operational risk. A single plant shutdown due to quality issues (as seen in the Ranbaxy scandal), a natural disaster, or an export ban can trigger crippling global shortages of critical medicines.118

- Brand Defense Tactics: Innovator companies deploy several strategies to blunt the impact of generic competition. They may launch their own “authorized generic” (AG) through a subsidiary, which enters the market during the 180-day exclusivity period and can reduce the FTF generic’s revenues by 40-52%.77 Another tactic is “product hopping,” where the brand makes a minor change to a drug’s formulation to secure a new patent and switch patients before the original patent expires, stranding the generic competitor.41

- The Impact of the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA): The IRA’s drug price negotiation program poses a systemic threat to the generic business model. By allowing Medicare to set a “Maximum Fair Price” (MFP) for high-spend drugs nine years after approval, the IRA may substantially lower the brand price before generic entry is possible (which occurs on average after 12-14 years).142 This transforms the lucrative “patent cliff” into a much less attractive “patent slope,” dramatically reducing the potential profit for a generic challenger and weakening the incentive to engage in costly patent litigation.41

- The High-Stakes Gamble of “At-Risk” Launches: A generic company can choose to launch its product after receiving FDA approval but before all patent litigation is resolved. This “at-risk” launch allows it to start generating revenue earlier but exposes it to the risk of catastrophic damages if the courts ultimately rule in favor of the brand.73

Case Study: Protonix (pantoprazole). A quintessential example of the perils of an at-risk launch involves the acid-reflux drug Protonix. In 2007 and 2008, generic manufacturers Teva and Sun Pharmaceutical launched their versions of the drug while patent litigation was still ongoing. Their gamble was based on a strong belief that the originator’s patent was invalid. However, in 2010, a jury upheld the patent. The at-risk launch ultimately proved to be a disastrous financial decision, culminating in a settlement where the generic companies agreed to pay $2.15 billion in damages to the brand manufacturers, Pfizer and Takeda. This case stands as a stark reminder of the immense financial liability associated with at-risk launches and the critical importance of the underlying patent litigation outcome.146

Section 4.2: The Biosimilar Investment Thesis

The biosimilar investment thesis is a high-risk, high-reward proposition based on successfully navigating a complex R&D and legal gauntlet to capture a share of the most valuable segment of the pharmaceutical market.

Opportunities

- The $200B+ “Patent Cliff” (2025-2030): The single greatest opportunity in the biosimilar space is the impending loss of exclusivity for an unprecedented number of blockbuster biologics. Between 2025 and 2030, drugs with combined annual sales exceeding $200 billion are set to face competition.40 This includes mega-brands like Merck’s cancer immunotherapy Keytruda (>$29 billion in 2024 sales; patent expiry 2028), J&J’s Stelara, and BMS’s Opdivo, creating a massive revenue pool for successful biosimilar entrants to tap into.112

- Potential for Higher, More Durable Margins: The formidable scientific, regulatory, and financial barriers to entry naturally limit the number of competitors in any given biosimilar market. This less crowded landscape, combined with the need to recoup substantial R&D investment, leads to more rational pricing and less severe price erosion compared to generics. This creates the potential for biosimilars to achieve more sustainable, brand-like profitability over their lifecycle.36

- First-Mover Advantage: While not as codified as the 180-day exclusivity for generics, being one of the first biosimilars to launch for a given reference product can confer a significant commercial advantage. Early entrants have the opportunity to establish relationships with payers, secure favorable formulary positions, and build confidence and familiarity among prescribers before the market becomes more crowded.40

Risks

- Prohibitive Upfront Investment: The development cost of $100 million to $300 million represents a massive capital risk.36 A single late-stage failure can be a catastrophic, company-threatening event, particularly for smaller, less-diversified developers. This high cost is a primary barrier to entry and a key consideration for any investor.

- Manufacturing and Batch Consistency Hurdles: The inherent variability of biologic manufacturing is a major technical risk.154 A developer must not only create a process that yields a “highly similar” product but also demonstrate that this process is robust and can consistently produce the product within tight quality specifications from batch to batch.29 Failure to achieve this consistency can result in regulatory rejection or costly delays.157

- Protracted and Costly Patent Litigation: As discussed, biosimilar developers must contend with dense “patent thickets” that can involve litigating dozens or even hundreds of patents simultaneously.80 This process can take years and cost tens of millions of dollars in legal fees, creating immense financial strain and uncertainty around the launch timeline.39

- Slow Market Uptake and Payer Barriers: Even after securing regulatory approval and clearing patent hurdles, a biosimilar can fail commercially. The “rebate wall” erected by brand manufacturers and PBMs can block formulary access, while physician and patient hesitancy can lead to a slow and unpredictable revenue ramp, severely delaying the return on a massive upfront investment.80

- Clinical Development Failures: Despite being based on a molecule with proven efficacy, biosimilar development programs can and do fail. The risks inherent in large-molecule development, such as unexpected immunogenicity or loss of effect, are always present.

Case Study: Pfizer’s Bococizumab. While bococizumab was a novel biologic, not a biosimilar, its failure provides a powerful case study of the risks inherent in large-molecule antibody development that are directly relevant to biosimilar investors. Bococizumab was a PCSK9 inhibitor for lowering cholesterol, in the same class as the successful drugs Praluent and Repatha. After investing heavily in a massive late-stage clinical trial program (the SPIRE studies), Pfizer abruptly discontinued development in 2016. The reasons cited were an “unanticipated attenuation” of LDL cholesterol lowering over time and a higher-than-expected rate of immunogenicity (patients developing antibodies against the drug) and injection-site reactions.161 This outcome, after multiple Phase 3 trials had met their primary endpoints, highlights the unpredictable nature of clinical development for complex biologics and the catastrophic financial loss (a $0.04 per share charge) that can result from a late-stage failure.164

Case Study: Teva’s Filgrastim Withdrawal. Regulatory approval does not guarantee commercial success. Teva’s biosimilar to filgrastim, Tevagrastim, was approved by the EMA in 2008.167 However, another filgrastim biosimilar, Ratiograstim (from a Teva subsidiary), was voluntarily withdrawn from the EU market by the manufacturer in 2011.168 While the specific commercial reasons are not public, such withdrawals typically occur when a product fails to gain sufficient market share in a competitive environment to be profitable. This case illustrates that even after clearing the high hurdles of development and approval, a biosimilar can still fail as an investment if it cannot compete effectively on price and market access against both the originator and other biosimilar players.170

| Metric | Generic Drugs | Biosimilars |

| Upfront Investment | Low ($1-5M) 4 | Very High ($100-300M) 39 |

| Time to Market | Short (~2 years) 4 | Long (6-9 years) 40 |

| Primary Risk Driver | Commercial (Post-launch price collapse) 41 | Technical/Regulatory/Legal (Pre-launch failure) 36 |

| Probability of Success | Very High (>90%) | Moderate (~50-75%) 39 |

| Key Value Driver | 180-Day FTF Exclusivity 72 | Targeting High-Value Biologics & Early Market Entry 40 |

| Pricing Power | Very Low (Rapid commoditization) 42 | Moderate (Durable discounts of 15-50%) 44 |

| Margin Profile | Low, rapidly eroding 41 | Higher, more sustainable 36 |

| Competitive Intensity | Extremely High (Many players) 114 | Moderate (Fewer players due to high barriers) 36 |

| Litigation Strategy | Offensive (Win exclusivity) 79 | Defensive (Clear the path to market) 81 |

| Market Adoption Risk | Low (Automatic substitution) 116 | High (Payer/Physician hurdles) 96 |

V. The Strategic Playbook for Investors

Armed with an understanding of the fundamental differences and risk profiles of generics and biosimilars, investors can develop tailored strategies for identifying attractive assets and navigating the competitive landscape of each sector. Success is not about choosing one market over the other, but about applying the correct analytical framework to the specific opportunity at hand.

Section 5.1: Identifying Winning Candidates

Framework for Evaluating Generic Opportunities

A data-driven approach is essential for identifying profitable generic drug candidates amidst a sea of commoditized products. The evaluation framework should prioritize assets that possess inherent barriers to competition. Key analytical steps include:

- Patent Landscape and Litigation Analysis: The process begins with a rigorous assessment of the target brand drug’s patent portfolio. The ideal candidate is a product protected by a small number of patents that appear vulnerable to a validity or infringement challenge. This increases the probability of a successful Paragraph IV filing and the capture of 180-day exclusivity.74

- Market Size vs. Competitive Intensity: An analysis of the brand’s annual sales must be cross-referenced with an estimate of the number of potential ANDA filers. The most attractive opportunities are often not the absolute largest markets, but those where the competitive density is likely to be low, preserving margins for a longer period post-launch.133

- Technical and Manufacturing Complexity: Investors should screen for products with high technical barriers to entry. This includes complex formulations (e.g., extended-release), difficult-to-synthesize APIs, or specialized manufacturing requirements (e.g., sterile injectables). These complexities naturally limit the field of competitors and create a more defensible market position for companies with the requisite technical expertise.132

Framework for Evaluating Biosimilar Opportunities

Evaluating a biosimilar asset requires a different lens, one focused on de-risking a massive, long-term R&D investment. The framework should assess:

- Technical and Manufacturing Prowess: The single most important factor is the developer’s demonstrated expertise in large-molecule development and manufacturing. Due diligence must scrutinize the company’s cell line development, process optimization, and analytical characterization capabilities. A history of successfully and consistently manufacturing complex biologics is a critical indicator of a lower technical risk profile.36

- Freedom to Operate (FTO) and Legal Strategy: Before significant capital is committed, a thorough FTO analysis is required to map the reference product’s “patent thicket” and develop a credible strategy for navigating it. This involves identifying which patents to challenge, which to “design around,” and budgeting for a potentially protracted and expensive legal battle.81

- Market Access and Commercialization Plan: The investment case must include a sophisticated analysis of the target market’s specific access dynamics. Key questions include: Is the product physician-administered (like in oncology), where uptake can be driven by institutions, or is it a self-administered, pharmacy-dispensed product that will have to contend with PBM rebate walls? The company must have a clear and credible strategy for engaging with payers, PBMs, and physician groups to drive adoption post-launch.39

Section 5.2: The Role of Competitive Intelligence

In both the generic and biosimilar arenas, competitive intelligence—particularly patent intelligence—is not a peripheral legal function but a central pillar of corporate strategy and a primary driver of investment returns. The ability to effectively “weaponize” patent and regulatory data to select targets, predict competitor moves, and clear a path to market is the key differentiating capability for successful companies.

“Designing Around” Patents as a Core Strategy

A critical defensive and offensive strategy is “designing around” an innovator’s patents. This involves creating a product that achieves the same therapeutic outcome but does so using a formulation, manufacturing process, or delivery mechanism that does not literally infringe the claims of the originator’s patents.82 For a biosimilar developer, this could mean engineering a different, non-infringing cell culture medium. For a complex generic, it might involve using a different polymer to achieve extended release.175 This requires a deep integration of scientific innovation and legal analysis and is fundamental to establishing Freedom to Operate.

Leveraging Patent Intelligence Platforms

Modern pharmaceutical competition is impossible without leveraging sophisticated business intelligence tools. Platforms like DrugPatentWatch provide essential, curated data that forms the basis of strategic decision-making. These services offer:

- Comprehensive Patent Databases: Tracking all patents associated with a specific drug, including their expiration dates, legal status, and litigation history.177

- Regulatory and Clinical Trial Monitoring: Providing real-time updates on competitor ANDA and BLA filings, clinical trial progress, and regulatory communications, allowing companies to anticipate market entry timelines.136

- FTO and Landscape Analysis: These platforms are indispensable tools for conducting the initial patent landscaping and FTO analyses that guide product selection and “design around” strategies.81

- Litigation Intelligence: Tracking Paragraph IV challenges and “patent dance” proceedings provides critical insights into competitors’ legal strategies and the potential for early market entry via settlements.179

For an investor, a target company’s investment in and sophisticated use of such intelligence platforms is a key indicator of its strategic maturity and ability to compete effectively.

Section 5.3: Future Outlook and Emerging Trends

The Evolution of the Generic Market

The generic industry is undergoing a strategic transformation in response to the “profitability paradox.” Key trends include:

- Consolidation and Scale: The market continues to consolidate as smaller players are squeezed out by margin pressure, leaving a few large, global manufacturers with the scale necessary to compete on cost.103

- Vertical Integration: Successful players are increasingly integrating backward into API manufacturing to control costs and secure their supply chains.134

- Domestic Manufacturing and Supply Chain Resilience: In response to chronic drug shortages and geopolitical risks, there is a growing policy and commercial push to “onshore” or “near-shore” the manufacturing of essential generic medicines, creating opportunities for companies that invest in domestic production capacity.118

The Next Frontier for Biologics: The Rise of “Biobetters”

A significant emerging trend is the development of “biobetters” or “biosuperiors.” These are next-generation biologics that are intentionally modified to be superior to an existing reference product—for example, by engineering a longer half-life to allow for less frequent dosing, improving efficacy, or reducing immunogenicity.26

While biobetters do not benefit from an abbreviated regulatory pathway and must be approved as new drugs, they represent a powerful strategic evolution for biosimilar developers.185 This strategy allows a company to move up the value chain from imitation to innovation, creating its own novel intellectual property and potentially capturing a premium price point. For investors, companies with a pipeline of biobetters represent a hybrid investment, combining the market knowledge of a biosimilar player with the higher-margin potential of an innovator.94

Long-Term Impact of the IRA

The Inflation Reduction Act is poised to have a profound and lasting impact on the entire pharmaceutical investment landscape. The law’s “pill penalty,” which subjects small-molecule drugs to price negotiation four years earlier than biologics (9 years vs. 13 years post-approval), creates a strong incentive for capital to shift away from small-molecule R&D and toward biologics.142 This could have a long-term chilling effect on the generic market; if fewer innovative small-molecule drugs are developed, there will be fewer generic opportunities in the future. Conversely, it could further fuel the growth of the biologics and biosimilars market, making it an even more critical sector for investment.

VI. Conclusion and Strategic Recommendations

The investment landscapes for generic drugs and biosimilars, while both rooted in providing alternatives to high-cost brand-name medicines, are fundamentally divergent. They demand distinct analytical frameworks, risk appetites, and strategic approaches from the investment community. Generics represent a mature, high-volume, low-margin industry where value is created through operational efficiency and legal maneuvering. Biosimilars constitute a high-growth, high-risk sector where value is created through scientific execution and navigating immense development complexity.

Based on the comprehensive analysis presented in this report, the following strategic recommendations are offered for different investor profiles:

- For Venture Capital and Early-Stage Investors:

- Generics: The traditional generic space offers limited opportunities for venture-style returns due to rapid commoditization and high competition. Investment should be highly selective, focusing on companies with proprietary technologies that create high-barrier “complex generics” or novel manufacturing processes that offer a disruptive cost advantage.

- Biosimilars: This sector presents more viable, albeit high-risk, opportunities. The primary focus should be on companies developing novel manufacturing platforms or analytical technologies that can demonstrably and significantly reduce the cost and timeline of biosimilar development. A secondary, and potentially more lucrative, focus is on companies leveraging their biologic expertise to develop “biobetters,” which allows them to transition from imitation to innovation and create their own intellectual property.

- For Private Equity and Growth Equity Investors:

- Generics: The generic market is ripe for consolidation and operational improvement strategies. Attractive opportunities lie in “buy-and-build” plays that create scale, drive manufacturing and supply chain efficiencies, and rationalize product portfolios to focus on more profitable, complex generics. There is also a significant opportunity to invest in the reshoring of essential medicine manufacturing to address systemic supply chain fragility.

- Biosimilars: The most compelling opportunity is financing the late-stage development and commercial launch of biosimilar assets targeting the multi-billion-dollar blockbuster biologics losing patent protection between 2025 and 2030. This involves backing management teams with proven regulatory and market access expertise. Carve-outs of biosimilar divisions from large pharmaceutical companies or roll-up strategies to create specialized biosimilar platforms in high-growth therapeutic areas like oncology and immunology also represent attractive theses.

- For Public Market Investors:

- Generics: Investing in large, publicly traded generic companies like Teva or Sandoz is a bet on scale, global reach, and a diversified pipeline that can weather the price erosion of individual products. Due diligence should focus on the company’s portfolio mix (proportion of complex vs. simple generics), operational efficiency metrics, and its strategy for managing supply chain risks and the impact of the IRA.

- Biosimilars: Investing in companies with significant biosimilar exposure (such as Amgen, Pfizer, or specialized players like Coherus) is a higher-risk, higher-growth proposition. The investment thesis is a direct play on the company’s ability to successfully execute its pipeline against the upcoming biologic patent cliff. Key metrics to scrutinize include the number of late-stage biosimilar candidates, the commercial potential of their reference products, and the company’s track record in navigating both the FDA regulatory process and the complex PBM and payer landscape.

In conclusion, both the generic and biosimilar markets will continue to play a critical role in the global healthcare ecosystem. However, investors must recognize them as distinct asset classes. The generic market is a game of inches, won on cost and speed. The biosimilar market is a game of high-stakes R&D, won on scientific and regulatory excellence. A clear-eyed understanding of this fundamental dichotomy is the essential first step toward successful capital deployment in either sector.

Works cited

- Generic Drugs Market Size to Hit USD 728.64 Billion by 2034, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.precedenceresearch.com/generic-drugs-market

- Biosimilars Market Size to Hit USD 175.99 Billion by 2034, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.precedenceresearch.com/biosimilars-market

- Generic drug – Wikipedia, accessed August 8, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Generic_drug

- Biosimilar vs Generic Drugs: Key Differences in Healthcare – Medical Packaging Inc, accessed August 8, 2025, https://medpak.com/biosimilar-vs-generic-drugs/

- From Small Molecules to Biologics, New Modalities in Drug Development – Chemaxon, accessed August 8, 2025, https://chemaxon.com/blog/small-molecules-vs-biologics

- Small Molecules vs. Biologics: Key Drug Differences – Allucent, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.allucent.com/resources/blog/points-consider-drug-development-biologics-and-small-molecules

- Understanding Biologic and Biosimilar Drugs, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.fightcancer.org/policy-resources/understanding-biologic-and-biosimilar-drugs

- Difference Between Small Molecule and Large Molecule Drugs – Caris Life Sciences, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.carislifesciences.com/difference-between-small-molecule-and-large-molecule-drugs/

- How Similar Are Biosimilars? What Do Clinicians Need to Know About Biosimilar and Follow-On Insulins?, accessed August 8, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5669137/

- Foundational Concepts Generics and Biosimilars – FDA, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/media/154912/download

- Facts About Generic Drugs – FDA, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/media/83670/download

- 7 FAQs About Generic Drugs | Pfizer, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.pfizer.com/news/articles/7_faqs_about_generic_drugs

- Abbreviated New Drug Application – Wikipedia, accessed August 8, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abbreviated_New_Drug_Application

- Generic Drugs – Glossary | HealthCare.gov, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.healthcare.gov/glossary/generic-drugs/

- Generic Drugs: Questions & Answers – FDA, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/frequently-asked-questions-popular-topics/generic-drugs-questions-answers

- Generic medicine – EMA – European Union, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/glossary-terms/generic-medicine

- Generic Medicines, accessed August 8, 2025, https://accessiblemeds.org/about/generic-medicines/

- Generic and hybrid medicines | European Medicines Agency (EMA), accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/human-regulatory-overview/marketing-authorisation/generic-hybrid-medicines

- Did you know? | Medicines for Europe, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.medicinesforeurope.com/generic-medicines/did-you-know/

- FDA definitions of generics and biosimilars, accessed August 8, 2025, https://gabionline.net/biosimilars/general/FDA-definitions-of-generics-and-biosimilars

- synergbiopharma.com, accessed August 8, 2025, https://synergbiopharma.com/biologics-vs-small-molecules/#:~:text=Size%20and%20Structure,down%20in%20the%20digestive%20system.

- What Is a Biosimilar? – FDA, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/media/108905/download

- Biosimilars Basics for Patients – FDA, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/biosimilars/biosimilars-basics-patients

- Biosimilars: Key regulatory considerations and similarity assessment tools – PMC, accessed August 8, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5698755/

- Understanding the Differences: Large Molecules vs Small Molecules – Adragos Pharma, accessed August 8, 2025, https://adragos-pharma.com/understanding-the-differences-large-molecules-vs-small-molecules/

- Biosimilar – Wikipedia, accessed August 8, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Biosimilar

- Biosimilars: Not Simply Generics – U.S. Pharmacist, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.uspharmacist.com/article/biosimilars-not-simply-generics

- Biosimilars: Manufacturing and Inherent Variation – YouTube, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rPuwPh63z2Y

- Innovative Formulation Strategies for Biosimilars: Trends Focused on Buffer-Free Systems, Safety, Regulatory Alignment, and Intellectual Property Challenges – PMC – PubMed Central, accessed August 8, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12196224/

- Biologics and Biosimilars: Background and Key Issues – Congress.gov, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/R44620

- Definition of biosimilar drug – NCI Dictionary of Cancer Terms, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms/def/biosimilar-drug

- Biosimilar medicines: Overview | European Medicines Agency (EMA), accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/human-regulatory-overview/biosimilar-medicines-overview

- Nonproprietary Naming of Biological Products Guidance for Industry | FDA, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/files/drugs/published/Nonproprietary-Naming-of-Biological-Products-Guidance-for-Industry.pdf

- Naming Convention, Interchangeability, and Patient Interest in Biosimilars – PMC, accessed August 8, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7428664/

- The Naming of Biosimilar Medicines Worldwide Should Promote Patient Safety and Prescriber Confidence, accessed August 8, 2025, https://biosimilarscouncil.org/resource/the-naming-of-biosimilar-medicines-worldwide-should-promote-patient-safety-and-prescriber-confidence/

- The Economics of Biosimilars – PMC, accessed August 8, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4031732/

- Can Biosimilar Development Costs Be “Genericized”? |, accessed August 8, 2025, https://biosimilarsrr.com/2022/09/16/can-biosimilar-development-costs-be-genericized/

- Biosimilars Market Growth, Drivers, and Opportunities – MarketsandMarkets, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.marketsandmarkets.com/Market-Reports/biosimilars-40.html

- Evaluating Biosimilar Development Projects: An Analytical Framework Utilizing Net Present Value – PMC, accessed August 8, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11955401/

- Three imperatives for R&D in biosimilars | McKinsey, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/life-sciences/our-insights/three-imperatives-for-r-and-d-in-biosimilars

- From Chaos to Clarity: Streamlining Your Generic Drug Portfolio …, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/from-chaos-to-clarity-streamlining-your-generic-drug-portfolio/

- Drug Competition Series – Analysis of New Generic Markets Effect of Market Entry on Generic Drug Prices – HHS ASPE, accessed August 8, 2025, https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/510e964dc7b7f00763a7f8a1dbc5ae7b/aspe-ib-generic-drugs-competition.pdf

- Price Declines after Branded Medicines Lose Exclusivity in the US – IQVIA, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.iqvia.com/-/media/iqvia/pdfs/institute-reports/price-declines-after-branded-medicines-lose-exclusivity-in-the-us.pdf

- Biosimilars: A Cure for the Higher Price of Complex Drugs? – American Century Investments, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.americancentury.com/insights/biosimilars-cure-for-the-higher-price-of-complex-drugs/

- Decreasing Drug Costs Through Generics and Biosimilars – National Conference of State Legislatures, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.ncsl.org/health/decreasing-drug-costs-through-generics-and-biosimilars

- Report: 2023 U.S. Generic and Biosimilar Medicines Savings Report …, accessed August 8, 2025, https://accessiblemeds.org/resources/reports/2023-savings-report-2/

- Biosimilars: where will the market be in five years? | Alvarez & Marsal, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.alvarezandmarsal.com/insights/biosimilars-where-will-the-market-be-in-five-years

- The Biosimilar Reimbursement Revolution: Navigating Disruption and Seizing Competitive Advantage – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-impact-of-biosimilars-on-biologic-drug-reimbursement-models/

- Biological Product Definitions | FDA, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/files/drugs/published/Biological-Product-Definitions.pdf

- 40th Anniversary of the Generic Drug Approval Pathway | FDA, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/cder-conversations/40th-anniversary-generic-drug-approval-pathway

- www.fda.gov, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/abbreviated-new-drug-application-anda/hatch-waxman-letters#:~:text=The%20%22Drug%20Price%20Competition%20and,Drug%2C%20and%20Cosmetic%20Act%20(FD%26C

- What is Hatch-Waxman? – PhRMA, accessed August 8, 2025, https://phrma.org/resources/what-is-hatch-waxman

- Hatch-Waxman Act – Practical Law, accessed August 8, 2025, https://uk.practicallaw.thomsonreuters.com/Glossary/PracticalLaw/I2e45aeaf642211e38578f7ccc38dcbee

- What is ANDA? – UPM Pharmaceuticals, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.upm-inc.com/what-is-anda

- Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) – FDA, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/types-applications/abbreviated-new-drug-application-anda

- Abbreviated New Drug Applications (ANDA) Explained: A Quick-Guide – The FDA Group, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.thefdagroup.com/blog/abbreviated-new-drug-applications-anda

- Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) Forms and Submission Requirements – FDA, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/abbreviated-new-drug-application-anda/abbreviated-new-drug-application-anda-forms-and-submission-requirements

- Generic and hybrid applications | European Medicines Agency (EMA), accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/human-regulatory-overview/marketing-authorisation/generic-hybrid-medicines/generic-hybrid-applications

- Comparing Pathways for Making Repurposed Drugs Available In The EU, UK, And US, accessed August 8, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11788669/

- How Generic Drugs are Registered in Europe, United Kingdom, Australia and New Zealand? – International Journal of Pharmaceutical Investigation, accessed August 8, 2025, https://jpionline.org/storage/2023/07/IntJPharmInvestigation-13-3-440.pdf

- Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.dpc.senate.gov/healthreformbill/healthbill70.pdf

- An unofficial legislative history of the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act of 2009 – PubMed, accessed August 8, 2025, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24479247/

- Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act of 2009 – Wikipedia, accessed August 8, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Biologics_Price_Competition_and_Innovation_Act_of_2009

- “The Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act 10–A Stocktaking” by Yaniv Heled – Texas A&M Law Scholarship, accessed August 8, 2025, https://scholarship.law.tamu.edu/journal-of-property-law/vol7/iss1/3/

- Commemorating the 15th Anniversary of the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/cder-conversations/commemorating-15th-anniversary-biologics-price-competition-and-innovation-act

- A Systematic Review of U.S. Biosimilar Approvals: What Evidence Does the FDA Require and How Are Manufacturers Responding?, accessed August 8, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10398206/

- Key Terms & Concepts – FDA, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/media/182177/download

- What are 351(a) & 351(k)? – DDReg Pharma, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.ddregpharma.com/what-are-351a-351k-in-biologics

- Overview of the Regulatory Framework and FDA’s Guidance for the …, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/media/113820/download

- Biosimilar Regulatory Approval Pathway – FDA, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/media/154914/download

- Biosimilar medicines: marketing authorisation – EMA – European Union, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/human-regulatory-overview/marketing-authorisation/biosimilar-medicines-marketing-authorisation

- Small Business Assistance | 180-Day Generic Drug Exclusivity – FDA, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/cder-small-business-industry-assistance-sbia/small-business-assistance-180-day-generic-drug-exclusivity

- NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES NO FREE LAUNCH: AT-RISK ENTRY BY GENERIC DRUG FIRMS Keith M. Drake Robert He Thomas McGuire Alice K. N, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w29131/w29131.pdf

- Key Strategies for Successfully Challenging a Drug Patent …, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/key-strategies-for-successfully-challenging-a-drug-patent/

- Paragraph IV Explained – ParagraphFour.com, accessed August 8, 2025, https://paragraphfour.com/paragraph-iv-explained/

- The timing of 30‐month stay expirations and generic entry: A cohort study of first generics, 2013–2020, accessed August 8, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8504843/

- Authorized Generic Drugs: Short-Term Effects and Long-Term Impact | Federal Trade Commission, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.ftc.gov/sites/default/files/documents/reports/authorized-generic-drugs-short-term-effects-and-long-term-impact-report-federal-trade-commission/authorized-generic-drugs-short-term-effects-and-long-term-impact-report-federal-trade-commission.pdf

- The 180-Day Rule Supports Generic Competition. Here’s How., accessed August 8, 2025, https://accessiblemeds.org/resources/blog/180-day-rule-supports-generic-competition-heres-how/

- The Hatch-Waxman 180-Day Exclusivity Incentive Accelerates Patient Access to First Generics, accessed August 8, 2025, https://accessiblemeds.org/resources/fact-sheets/the-hatch-waxman-180-day-exclusivity-incentive-accelerates-patient-access-to-first-generics/

- Failure to Launch: Biosimilar Sales Continue to Fall Flat in the United States – PMC, accessed August 8, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7255927/

- Cracking the Biosimilar Code: A Deep Dive into Effective IP Strategies – Drug Patent Watch, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/cracking-the-biosimilar-code-a-deep-dive-into-effective-ip-strategies/

- The Pharmaceutical Patent Playbook: Forging Competitive …, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/developing-a-comprehensive-drug-patent-strategy/

- What Is the Patent Dance? | Winston & Strawn Law Glossary, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.winston.com/en/legal-glossary/patent-dance

- What Are the Patent Litigation Differences Between the BPCIA and Hatch-Waxman Act? | Winston & Strawn Law Glossary, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.winston.com/en/legal-glossary/BPCIA-Hatch-Waxman-Act-differences

- Patent Dance Insights: A Q&A on Reducing Legal Battles in the Biosimilar Landscape, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.centerforbiosimilars.com/view/patent-dance-insights-a-q-a-on-reducing-legal-battles-in-the-biosimilar-landscape

- Five key questions about the ‘patent dance’ answered – Generics and Biosimilars Initiative, accessed August 8, 2025, https://gabionline.net/switchlanguage/to/gabi_online_en/policies-legislation/Five-key-questions-about-the-patent-dance-answered