Introduction: Beyond the Pill Counter – Formulary Management as a Strategic Imperative

In the world of healthcare the pharmaceutical formulary has evolved far beyond a simple, static list of covered medications. It is now the central nervous system of cost control, patient access, and clinical quality for any health plan, hospital system, or Pharmacy Benefit Manager (PBM). The modern formulary’s dual mandate is to provide members with access to appropriate, life-altering therapies while simultaneously ensuring the financial sustainability of the organization in an era of skyrocketing drug costs.1 This is no longer a back-office administrative task; it is a frontline strategic function.

Welcome to what industry insiders call “Formulary Management 2.0,” a dynamic arena where data science, predictive analytics, and the principles of value-based care converge to reshape how medicines are chosen, paid for, and delivered.3 The game has shifted from merely reacting to price changes to proactively anticipating and shaping market dynamics. Instead of just favoring the cheapest option, today’s forward-thinking formulary managers weigh a drug’s real-world performance—its ability to reduce hospitalizations, improve quality of life, and deliver measurable outcomes.

This strategic chessboard is populated by several key players, each with distinct roles and motivations. At the heart of clinical decision-making are the Pharmacy & Therapeutics (P&T) Committees. Comprised of a diverse group of physicians, pharmacists, nurses, and other healthcare professionals, these committees serve as the scientific and ethical backbone of the formulary.2 Their primary function is to objectively appraise, evaluate, and select drugs for the formulary based on a rigorous review of evidence-based medicine, clinical trial data, and real-world evidence.5 They are the gatekeepers of clinical value, tasked with developing the utilization management (UM) policies—such as prior authorizations, step therapies, and quantity limits—that ensure appropriate medication use.1

Orchestrating the commercial and administrative aspects are the Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs). These powerful intermediaries sit at the center of the pharmaceutical supply chain, contracted by health plans and employers to manage prescription drug benefits.7 PBMs wield immense influence; they build and manage pharmacy networks, process billions of claims, and, most critically, negotiate rebates with drug manufacturers to determine which drugs gain preferential placement on the formulary.9 This role, however, is fraught with inherent conflict. While PBMs are positioned as agents of cost control, saving the U.S. healthcare system a projected $1.2 trillion over the next decade , their business models can create a paradox. Rebates are often calculated as a percentage of a drug’s list price, which can create a perverse incentive to favor high-list-price, high-rebate brand drugs over potentially more cost-effective alternatives.8 This dynamic means a PBM might secure a massive rebate that lowers the net cost for the health plan, while the patient at the pharmacy counter faces a staggering out-of-pocket cost based on the inflated list price—a crucial disconnect that every formulary manager must comprehend.

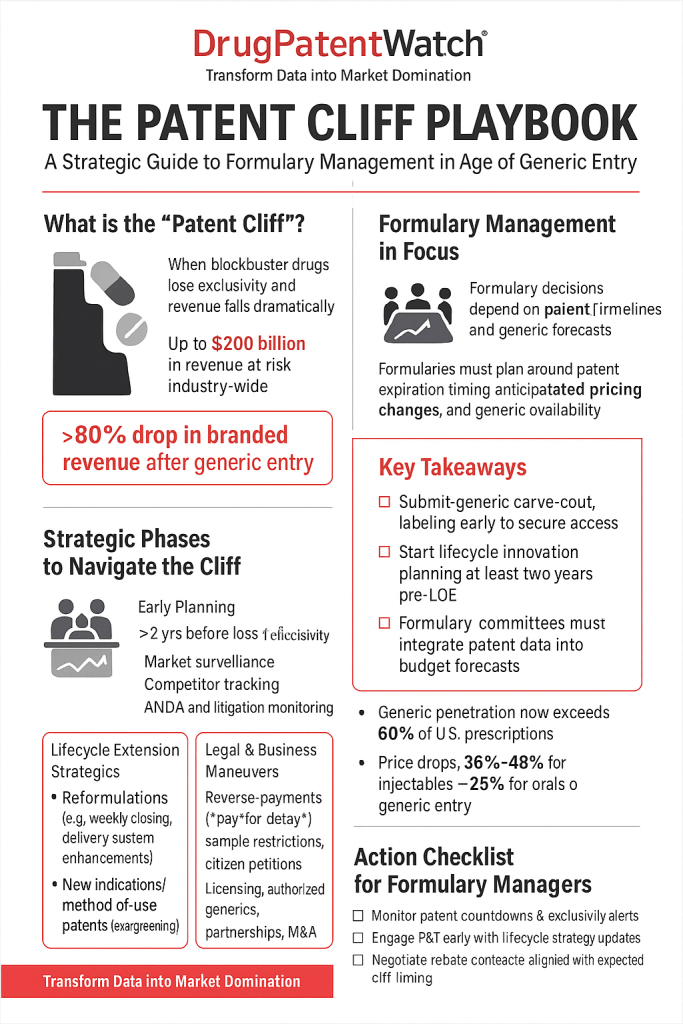

Nowhere are these strategic tensions more pronounced than on the precipice of the “patent cliff.” This term captures the dramatic, often catastrophic, revenue loss a brand-name drug manufacturer faces when its market exclusivity ends and a flood of lower-cost generic competitors enters the market.14 The scale of this challenge is monumental. Between 2025 and 2030 alone, an estimated

$236 billion in global pharmaceutical revenue is at risk due to patent expirations. For payers and formulary managers, this cliff is not a threat but a massive opportunity. It represents the single greatest inflection point for recalibrating drug spend and generating billions in savings.

This report is your playbook for navigating that cliff. It is designed for the business professional—the formulary director, the PBM executive, the health plan strategist—who needs to turn complex patent data, regulatory filings, and litigation intelligence into a decisive competitive advantage. We will dissect the process of anticipating generic entry, identifying the first challengers, and projecting the inevitable price erosion that follows. The goal is to move your organization from a reactive posture, where you are surprised by market shifts, to a proactive one, where you anticipate them, plan for them, and capitalize on them to the fullest extent.

Decoding the Rules of the Game: The Hatch-Waxman Act and the Architecture of Market Exclusivity

To win any game, you must first master its rules. In the high-stakes world of U.S. pharmaceutical competition, the rulebook was written in 1984. The Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act, known universally as the Hatch-Waxman Act, was a landmark piece of legislation that fundamentally reshaped the industry. It was a grand compromise, meticulously designed to balance two competing interests: incentivizing brand-name companies to undertake the risky, expensive journey of drug innovation, and facilitating the timely entry of low-cost generic drugs to ensure affordability and access for the public.17

Before Hatch-Waxman, the generic drug market was nascent. Generic manufacturers faced a nearly insurmountable barrier: they were required to conduct their own expensive and time-consuming clinical trials to prove the safety and efficacy of their products, even if the active ingredient was identical to a long-approved brand. As a result, in 1984, generics accounted for a mere 19% of all prescriptions filled in the United States.17 The Act dismantled this barrier, creating the modern generic industry and, with it, a new strategic landscape for formulary managers.

The Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA): The Engine of the Generic Industry

At the heart of the Hatch-Waxman Act is the creation of the Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) pathway. This regulatory mechanism is the engine that drives the generic drug industry, allowing for a streamlined approval process that makes low-cost alternatives economically viable.21

The core principle of the ANDA is that a generic manufacturer can rely on the FDA’s previous finding of safety and effectiveness for the innovator drug, known as the Reference Listed Drug (RLD). This elegantly simple provision eliminates the need to repeat duplicative, multi-million-dollar clinical trials, which represent the largest portion of a new drug’s development cost.

Instead of proving safety and efficacy from scratch, the generic firm’s primary scientific burden is to demonstrate bioequivalence. This is the cornerstone of the entire system. Through carefully designed studies, typically in a small group of healthy volunteers, the generic manufacturer must prove that its product delivers the same amount of the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) into a person’s bloodstream over the same period of time as the RLD.25 By proving bioequivalence, the generic is deemed to be therapeutically equivalent, meaning it can be substituted for the brand-name drug with the full expectation that it will produce the same clinical effect and safety profile. It is crucial to note that while the API must be identical, U.S. trademark laws often prevent the generic from looking exactly like the brand. This means inactive ingredients (like fillers and dyes) can vary, resulting in differences in size, shape, and color—a point of frequent confusion for patients that can impact adherence.28

The ANDA submission and review process is a rigorous, multi-step journey.21 It begins with extensive pre-ANDA preparation, where the sponsor meticulously characterizes the RLD and conducts its bioequivalence studies. The sponsor then compiles a comprehensive dossier containing Chemistry, Manufacturing, and Controls (CMC) data, stability testing reports, labeling information, and the pivotal bioequivalence data. This application is submitted electronically to the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER). Upon receipt, the FDA conducts a multi-phase review that scrutinizes the data, inspects the manufacturing facilities for quality, and ensures the labeling is compliant. This entire process, from submission to a final decision, can take approximately 30 months, though it can be expedited for drugs addressing shortages or other priority needs.21

The Fortress of Exclusivity: Understanding the “Exclusivity Stack”

For a formulary manager, simply tracking a brand drug’s primary patent expiration date is a rookie mistake that can lead to disastrously inaccurate budget forecasts. A drug’s market monopoly is not a single wall; it is a fortress built with multiple layers of protection. Understanding this complex “exclusivity stack,” composed of various patents and non-patent regulatory exclusivities, is absolutely critical for accurately predicting the earliest possible date of generic entry.

Pharmaceutical Patents: The First Line of Defense

Patents are the first and most formidable line of defense, granting the innovator exclusive rights for a period of 20 years from the patent’s filing date.33 However, this protection is not monolithic. Brand companies strategically build a “patent thicket”—a dense, overlapping web of different patent types designed to frustrate and delay generic challengers.35 Key patent types include:

- Composition of Matter Patents: These are the crown jewels. They cover the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) itself—the core molecule. These patents are the strongest, provide the broadest protection, and are the most difficult for a generic to invalidate or design around.33

- Secondary Patents: This is where the strategy of “evergreening” comes into play. These patents cover incremental innovations related to the drug and are layered on top of the core compound patent to extend exclusivity. They include:

- Formulation Patents: Protecting novel delivery methods, such as an extended-release tablet, an inhaler device, or a nanoparticle-based formulation. These can improve patient compliance or efficacy and create a new barrier to entry.33

- Method of Use Patents: Covering a new therapeutic use or indication for an existing drug. For example, a drug initially approved for hypertension might later be patented for treating heart failure.33

- Process and Polymorph Patents: Protecting the specific manufacturing process used to create the drug or a particular crystalline structure (polymorph) of the API, which can affect the drug’s stability and bioavailability.33

All patents that a brand manufacturer claims cover its approved drug are listed in the FDA’s publication, Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations, universally known as the “Orange Book.” This public database is the definitive starting point for any analysis of a drug’s patent landscape.17

Regulatory Exclusivities: Non-Patent Monopoly Periods

Operating independently of patents are several types of regulatory exclusivities granted by the FDA. These are statutory periods of market monopoly that can block generic approval even if all patents have expired or been successfully challenged. A savvy analyst must account for these in their timeline.

- Five-Year New Chemical Entity (NCE) Exclusivity: This is a critical barrier for entirely new drugs. When the FDA approves a drug containing an active moiety never before approved, it grants a five-year period of data exclusivity. During this time, the FDA is prohibited from even accepting an ANDA submission. There is a key exception: a generic company planning to challenge a patent with a Paragraph IV certification can file its ANDA after four years, a milestone known as “NCE-1”.19

- Three-Year “New Clinical Investigation” Exclusivity: This is granted for certain changes to a previously approved drug, such as a new dosage form, a new strength, or a new indication, if the approval of that change required new clinical investigations (other than bioavailability studies). This can protect a line extension from generic competition for three years.

- Pediatric Exclusivity (PED): This is one of the most powerful tools in a brand’s lifecycle management arsenal. If a manufacturer conducts pediatric studies requested by the FDA, it is rewarded with a six-month extension that is added to all existing patent terms and other regulatory exclusivities (like NCE or Orphan Drug) for that active moiety.19 A seemingly minor six-month add-on can delay generic entry across the board, significantly impacting budget forecasts.

- Orphan Drug Exclusivity (ODE): For drugs designated to treat a rare disease or condition (affecting fewer than 200,000 people in the U.S.), the FDA grants seven years of market exclusivity upon approval.

The table below summarizes these critical layers of protection and their direct implications for formulary management strategy.

| Exclusivity Type | Description | Typical Duration | Strategic Implication for Formulary Management |

| Composition of Matter Patent | Covers the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) itself. | 20 years from filing | The core barrier to entry. Its expiration date is the primary, but not final, date to watch. |

| Secondary Patents (Thicket) | Patents on formulations, methods of use, polymorphs, etc. | 20 years from filing | Creates a complex web of overlapping protections that can delay generic entry long after the main compound patent expires. Requires detailed analysis. |

| 5-Year NCE Exclusivity | For drugs with a new active moiety. FDA cannot accept an ANDA. | 5 years from approval | Creates a hard floor of 4-5 years before any generic can be considered, regardless of patent status. Calendar the 4-year “NCE-1” date as a high-probability start for generic challenges. |

| 3-Year Marketing Exclusivity | For new indications or formulations requiring new clinical studies. | 3 years from approval | Can protect a specific, often more profitable, version of a drug (e.g., an extended-release formulation) even when the base drug is off-patent. |

| Pediatric Exclusivity (PED) | Reward for conducting requested pediatric studies. | 6 months | Adds 6 months to ALL other existing patents and exclusivities. A seemingly minor detail that can push back generic entry and savings by half a year. Always check for this. |

| Orphan Drug Exclusivity (ODE) | For drugs treating rare diseases. | 7 years from approval | Provides a long period of monopoly for specialty drugs, often independent of patent status. A key factor in the high cost of rare disease treatments. |

By meticulously mapping out every one of these protections for a given brand-name drug, a formulary manager can move from a simplistic patent expiration date to a sophisticated, multi-layered forecast of the true “loss of exclusivity” (LOE) date. This is the first and most fundamental step in building a proactive formulary strategy.

The First Shot Fired: Mastering Paragraph IV Filings to Identify the First Challenger

If the Hatch-Waxman Act provides the rulebook, then a Paragraph IV (PIV) certification is the first shot fired in the war for market share. It is the single most important early signal that a brand drug’s monopoly is being actively challenged, and it sets in motion a predictable cascade of legal and regulatory events that a savvy analyst can track to anticipate generic entry.

When a generic company files its ANDA, it must make a formal declaration, or “certification,” for every single patent listed in the FDA’s Orange Book for the reference drug.26 There are four possible certifications:

- Paragraph I: A statement that no patent information has been filed with the FDA. This is extremely rare for modern drugs.

- Paragraph II: A statement that the listed patent has already expired.

- Paragraph III: A statement that the generic company will wait to market its product until the date the listed patent expires.

- Paragraph IV (PIV): A bold declaration that, in the generic company’s opinion, the listed patent is invalid, unenforceable, or will not be infringed by the proposed generic product.38

A PIV filing is a declaration of war. It signals that a generic company has invested significant resources in legal and scientific analysis, believes it has a legitimate path to circumvent the brand’s patent protection, and is willing to engage in high-stakes litigation to launch its product years ahead of schedule. For a formulary manager, this is the flashing red light that a blockbuster drug’s revenue stream is now officially under threat.

So, how do you track these critical filings? The process is governed by strict regulations, creating a trail of breadcrumbs for those who know where to look.

- The PIV Notice Letter: The process doesn’t begin in public. After a generic company files a PIV ANDA and receives an acknowledgment from the FDA that its application is complete enough for review, a new clock starts. The generic applicant has just 20 days to send a formal, detailed PIV notice letter to the brand-name drug’s owner and the patent holder. This letter serves as the official notice of the patent challenge, outlining the full factual and legal basis for the generic’s claim.

- Public Disclosures (SEC Filings): While the notice letter itself is confidential, its receipt is almost always considered a material event for a publicly traded brand-name company. Therefore, the brand will typically disclose the challenge to its investors in a Form 8-K filing with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) or in its next quarterly (10-Q) or annual (10-K) report. Monitoring these financial filings is one of the most reliable and timely ways to confirm that a PIV challenge has officially begun.

- FDA’s Paragraph IV Certifications List: The FDA itself provides a crucial public resource. The agency maintains and regularly updates a Paragraph IV Patent Certifications List. This database provides the drug name, dosage form, the RLD and its NDA number, the date of the first PIV submission for that drug, and, critically, the number of potential first applicants who filed on that first day. This list is an invaluable tool for identifying not just the first challenge, but the potential intensity of future competition.

- Integrated Competitive Intelligence Platforms: Synthesizing this information—tracking SEC filings, court dockets, and multiple FDA databases—can be a monumental task. This is where specialized business intelligence services like DrugPatentWatch provide a profound competitive advantage. These platforms aggregate the disparate data streams into a single, searchable, and dynamic interface. They track patent expirations, PIV challenges, ANDA filings, and ongoing litigation, transforming a complex research task into an efficient strategic analysis.41 For a formulary management team, leveraging such a tool is no longer a luxury; it’s a necessity for staying ahead of the market.

The timing of these filings is not random. For New Chemical Entities (NCEs), which are granted a five-year data exclusivity period, the law allows a generic to file a PIV challenge at the four-year mark (the “NCE-1” date). This has created a predictable “starting gun” event in the industry. Since about 2012, it has become common for multiple generic companies to prepare their ANDAs in advance and file them on the very first day possible. For a formulary manager, this is a powerful predictive tool. By simply calendaring the four-year anniversary of a major NCE’s approval, you can anticipate the likely start of generic challenges. If the FDA’s PIV list or company disclosures reveal multiple filers on that NCE-1 date, it’s a strong signal of a highly competitive future market, which in turn implies steeper and faster price erosion once the generics finally launch.

Once the brand company receives the PIV notice letter, it has 45 days to respond by filing a patent infringement lawsuit against the generic applicant. If it does so, it triggers one of the most significant provisions of the Hatch-Waxman Act: an automatic 30-month stay of FDA approval.38 This means the FDA is legally barred from granting final approval to the generic’s ANDA for up to 30 months, or until the court case is resolved in the generic’s favor, whichever comes first. This stay provides a predictable, albeit lengthy, timeline for both sides to litigate and for formulary managers to plan and budget for a potential market-changing event.

The Race to Be First: The Economics and Strategy of 180-Day Exclusivity

In the high-stakes race to market, simply being early is not enough; being first is everything. The Hatch-Waxman Act created the ultimate prize for the generic company willing to take on the risk and expense of a patent challenge: 180 days of marketing exclusivity.18 This provision is the primary economic engine driving PIV litigation and is a critical factor for any formulary manager to understand, as it directly shapes the competitive landscape and pricing dynamics in the first six months after a brand loses exclusivity.

This powerful incentive is granted to the “first applicant”—the first company (or companies, if they file on the same day) to submit a “substantially complete” ANDA containing a Paragraph IV certification. For the 180-day period following the launch of its product, the FDA is barred from approving any other generic ANDAs that also contain a PIV certification for the same drug.

The economics of this temporary, government-granted duopoly are compelling. With only the brand-name drug and a single generic on the market, the first-filer is shielded from the brutal price competition that ensues when multiple generics enter. It can price its product at a modest discount to the brand—enough to rapidly capture significant market share—while still maintaining exceptionally high profit margins. This 180-day window can be worth “several hundred million dollars” and is the primary reward for undertaking a costly patent challenge.38

However, the brand-name company is not a helpless bystander during this period. It holds a powerful trump card: the Authorized Generic (AG). This strategic gambit can completely upend the first-filer’s expectations and has profound implications for pricing.

An AG is the brand-name drug itself, simply packaged and marketed without the brand name. Because it is the exact same product, it is sold under the brand’s original New Drug Application (NDA) and does not require a separate ANDA approval from the FDA. Critically, federal courts have ruled that the 180-day exclusivity only blocks the approval of subsequent ANDAs. It does not prevent the brand company from launching its own generic version of its own drug.47

The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) has conducted extensive analysis on the impact of AGs, and its findings are essential for any formulary manager’s playbook. The launch of an AG during the 180-day period has two major, opposing effects:

- It Devastates First-Filer Revenue: The introduction of a third competitor (Brand, First-Filer Generic, Authorized Generic) shatters the profitable duopoly. The FTC found that an AG launch reduces the first-filer’s revenues by a staggering 40% to 52% during the exclusivity period.

- It Lowers Prices for Payers and Patients: This increased competition, however, is good news for the consumer. The FTC’s analysis showed that when an AG is present, wholesale generic prices are 7% to 14% lower, and retail prices are 4% to 8% lower than they would be with only a single generic on the market.

This dynamic transforms the AG from a simple product into a powerful strategic weapon. The threat of launching an AG gives the brand company enormous leverage in settlement negotiations with a first-filer. The brand can offer a highly valuable “no-AG agreement”—a promise not to launch an authorized generic—in exchange for the generic company agreeing to delay its market entry. This is not a theoretical risk; it is a well-documented practice. The FTC found that in fiscal year 2010, nearly 60% of settlements that involved both compensation to the generic and a delayed entry date included a no-AG agreement. These deals delayed generic entry by an average of 37.9 months. For a formulary manager, this is a critical insight. When a patent litigation settlement is announced, one must scrutinize the terms. The presence of a no-AG clause is a red flag for a “pay-for-delay” deal. It signals that the generic entry date was likely pushed back and that initial generic prices during the 180-day period will be higher than they could have been, as the first-filer will enjoy a true duopoly.

Finally, a first-filer is not guaranteed its exclusivity. The statute includes several forfeiture provisions that can cause the 180-day prize to be lost. The most significant of these is the “failure to market” provision. If a first-filer receives FDA approval but fails to launch its product within a specified timeframe (typically 75 days after a final court decision of non-infringement or invalidity, or 75 days after another generic’s ANDA is approved), it can forfeit its exclusivity, opening the door for the next generic applicant in line. This prevents a first-filer from “parking” its exclusivity indefinitely and blocking all other competition.

From Courtroom to Formulary: Tracking Litigation and Settlements to Refine Forecasts

The 30-month stay triggered by a PIV lawsuit creates a window of relative certainty, but the legal battle that unfolds within that window provides a rich stream of data for refining forecasts. Patent litigation is not an impenetrable black box; it is a process with predictable milestones, each offering clues about the likely timing and outcome of generic entry.26

Monitoring this process begins with knowing the key venues. A disproportionate amount of pharmaceutical patent litigation occurs in the federal district courts of Delaware and New Jersey, where judges have developed deep expertise and established local rules specifically for handling these complex cases.

Within the litigation timeline, several key events serve as critical inflection points:

- Complaint Filing: This is the brand’s opening move, filed within 45 days of receiving the PIV notice. Its primary significance is confirming that the 30-month stay of FDA approval has officially begun.

- Markman Hearing (Claim Construction): Arguably the most critical non-trial event in a patent case. In a Markman hearing, the judge hears arguments from both sides and issues a ruling that legally defines the meaning and scope of the patent’s claims. This ruling often determines the outcome of the entire case. A ruling that construes the patent’s claims narrowly is a major victory for the generic company, dramatically increasing its odds of proving non-infringement and signaling a higher probability of an early launch or a more favorable settlement.

- District Court and Federal Circuit Decisions: The final rulings from the trial court and, subsequently, the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (which has exclusive jurisdiction over patent appeals) provide the ultimate resolution. A definitive court victory for the generic company lifts the 30-month stay and clears the path for the FDA to grant final approval.

However, the vast majority of these battles never reach a final court decision. Over 75% of PIV challenges are resolved through settlement agreements. For formulary managers, a settlement announcement is a game-changing event, as it replaces the inherent uncertainty of litigation with the contractual certainty of a negotiated launch date.

These settlements, however, are often the subject of intense antitrust scrutiny due to the controversial practice of “pay-for-delay” or “reverse payment” agreements. In a typical lawsuit, the defendant pays the plaintiff to settle. In the pharmaceutical context, the payment often flows in the “reverse” direction: the brand-name plaintiff pays the generic defendant to settle the case and, in doing so, to delay its market entry.52

The economic impact of these deals is staggering. They are a win-win for the companies involved, allowing them to share the brand’s monopoly profits. But they are a significant loss for the healthcare system and consumers. A National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) working paper estimated that settling a single PIV challenge reduces consumer surplus by an average of $835 million over five years. Another NBER study found that these collusive settlements cost U.S. purchasers $3.1 to $3.2 billion per year between 2014 and 2023. The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) arrived at a similar figure, estimating that pay-for-delay deals cost consumers and taxpayers $3.5 billion in a single year by keeping lower-cost generics off the market.

Therefore, when a settlement is announced, it is imperative to decode its terms to understand its true market impact. Key provisions to look for include:

- Licensed Entry Date: This is the most critical piece of information—the specific, contractually agreed-upon date when the generic company is permitted to launch its product. This date becomes the new anchor for all budget forecasts.

- Acceleration Clauses: Also known as Most-Favored Entry (MFE) clauses, these are common provisions that protect the settling generic. They stipulate that if another generic company manages to enter the market even earlier (e.g., by winning its own litigation), the settling generic’s licensed entry date will be “accelerated” to match, ensuring it is not left behind.50

- No-AG Agreements: As previously discussed, a promise by the brand not to launch an authorized generic is a valuable form of non-cash payment. Its inclusion in a settlement is a strong indicator of a pay-for-delay arrangement and suggests that initial generic prices will be higher during the 180-day exclusivity period.

The following timeline provides a clear roadmap of this entire process, translating complex legal events into actionable business intelligence.

| Event | Typical Timing | Implication for Formulary Manager |

| Stage 1: Pre-Litigation | ||

| ANDA with PIV Certification Filed | 4 years post-NCE approval (“NCE-1”) or anytime for other drugs | The earliest signal of a challenge. Begin preliminary budget impact modeling. |

| PIV Notice Letter Sent to Brand | Within 20 days of FDA accepting ANDA for review | Confirms the challenge is proceeding. Monitor brand’s SEC filings for public disclosure. |

| Stage 2: Litigation | ||

| Complaint Filed by Brand | Within 45 days of PIV notice | Triggers the 30-month stay of FDA approval. This provides a concrete, albeit long, planning horizon. |

| Markman Hearing (Claim Construction) | ~12-18 months into litigation | A critical inflection point. A pro-generic ruling significantly increases the probability of an early launch or a favorable settlement. Re-evaluate forecasts. |

| District Court Decision | ~24-30 months into litigation | A generic win lifts the 30-month stay and can lead to launch upon FDA approval. A brand win likely delays entry until patent expiration. |

| Federal Circuit Appeal | ~12-18 months after district court decision | The final word on patent validity/infringement. |

| Stage 3: Settlement | ||

| Settlement Announcement | Can occur at any point during litigation | Provides a firm launch date, removing uncertainty. This is the most reliable predictor. Scrutinize terms for no-AG clauses or other signs of “pay-for-delay,” which signal higher initial generic prices and a likely delayed entry date. |

The Final Countdown: Projecting Price Erosion and Maximizing Savings

Once a generic launch date is firmly on the horizon, the next critical question for any formulary manager is: what will the financial impact be? Accurately projecting the erosion of the brand-name drug’s price is essential for budgeting and for designing strategies to maximize savings. A common misconception is that the arrival of the first generic immediately triggers a massive, 80-90% price drop. The reality is far more nuanced. Price erosion is a process, not a singular event, and its speed and depth are almost entirely driven by one factor: the number of competitors in the market.

“In 2022, it was estimated that 91% of all prescriptions in the United States were filled as generic drugs…. Prices continue to decline by 70% to 80% relative to the pre-generic entry price in markets of 10 or more competitors following 3 years after first generic entry.”

Synthesizing data from the FDA, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), and major industry studies provides a clear, evidence-based model for this price decay.24

- First Generic Entry (The Duopoly): The arrival of the first generic competitor marks the beginning of the end for the brand’s monopoly, but the initial price impact is modest. The first-filer, often protected by 180-day exclusivity, has little incentive for deep discounting. An FDA analysis found that the introduction of a single generic manufacturer reduced the drug’s price by a mere 6%. More recent data suggests a more significant, but still limited, reduction of about 39%. During this initial duopoly period, prices tend to plateau as the generic captures market share without initiating a price war.

- Second Generic Entry (The Start of Real Competition): The end of the 180-day exclusivity period and the arrival of the second generic competitor is the true tipping point. With a second entrant, genuine price competition begins. Studies show that with two generics on the market, the average price falls to about 52% of the original brand price, representing a 54% reduction from the brand’s monopoly price.24

- Multiple Generic Entrants (The Price Plunge): To achieve the dramatic savings often associated with generics, the market needs robust competition. Research consistently shows that at least three to four independent generic manufacturers are required to drive prices down substantially. As more competitors enter, the price plummets. The data paints a clear picture:

- With four competitors, the average generic price is 79% lower than the brand price.

- With six or more competitors, the price reduction can exceed 95%.

- Data from Medicare Part D reinforces this, showing that in markets with 10 or more competitors, prices fall by a staggering 70% to 80% relative to the pre-generic entry price.

It is also important to acknowledge the “generics paradox.” Counterintuitively, the price of the brand-name drug itself does not always fall after generic entry; sometimes, it even increases. This occurs because the market bifurcates. A large, price-sensitive segment of patients and plans rapidly switches to the low-cost generic. However, a smaller, price-insensitive segment of brand-loyal patients and prescribers remains. The brand manufacturer, having lost the price-sensitive portion of the market, may then increase its price to extract maximum value from the remaining loyalists who are unwilling to switch.

Finally, the rate of price decay is not uniform across all drug types. The model described above applies most accurately to traditional, small-molecule oral solid drugs. For more complex products—such as creams, inhalers, injectables, or biologics—the manufacturing barriers to entry are significantly higher. This results in fewer competitors entering the market, and consequently, a slower and less dramatic price decline.

The following table provides a powerful, data-driven tool for forecasting. By tracking the number of announced ANDA filers for a given drug, a formulary manager can use this model to project the likely level of price reduction and build more accurate and defensible budgets.

| Number of Generic Competitors | Average Generic Price Reduction vs. Brand Price (%) |

| 1 | 39% |

| 2 | 54% |

| 3 | ~65% (Interpolated) |

| 4 | 79% |

| 5 | ~85% |

| 6+ | >95% |

Case Studies in Action: Lessons from the Patent Cliff

The theoretical frameworks and predictive models come to life when applied to real-world battles over blockbuster drugs. By examining the history of major patent cliffs, we can see the entire playbook in action—from brand defense strategies and litigation tactics to the stark financial consequences of generic entry. Two cases in particular, Lipitor and Gleevec, offer invaluable and contrasting lessons for every formulary manager.

Case Study 1: Lipitor (Atorvastatin) – The Archetypal Blockbuster Cliff

For years, Pfizer’s Lipitor was not just a drug; it was a global phenomenon. As the world’s best-selling prescription medicine, it generated nearly $11 billion in annual sales at its peak, making its patent expiration one of the most anticipated and feared events in pharmaceutical history.62 The story of Lipitor’s fall is the archetypal case study of the patent cliff, demonstrating the immense financial impact and the aggressive, multi-pronged strategies brands will deploy to defend their franchises.

Pfizer’s defense began years before the cliff arrived. It was a textbook execution of pre-emptive lifecycle management. The company invested heavily in aggressive marketing and brand building, making “Lipitor” a household name and fostering deep loyalty among both physicians and patients. It also employed strategic pricing, initially launching at a competitive price to unseat the then-market leader, Merck’s Zocor, before raising prices once its dominance was established. Behind the scenes, it built a formidable patent thicket, layering on secondary patents to create a more complex legal barrier for would-be challengers.

When the primary patent cliff finally arrived in late 2011, Pfizer’s strategy shifted from long-term defense to fierce, hand-to-hand combat for market share. The company did not simply surrender to the first generic challenger (a partnership between Ranbaxy and Watson Pharmaceuticals). Instead, it launched a two-pronged counter-attack:

- The “Lipitor-For-You” Rebate Program: In an unprecedented move for a brand facing generic competition, Pfizer went to war on price. It established a program that offered deep rebates directly to payers and mail-order pharmacies, effectively matching the generic price for many patients in an attempt to retain as much market share as possible.

- The Authorized Generic Gambit: Simultaneously, Pfizer executed the classic AG strategy. It licensed its own drug to Watson Pharmaceuticals to be sold as an authorized generic. This move had a dual purpose: it allowed Pfizer to capture a significant portion of the revenue from the “generic” market, and it immediately introduced a third competitor into what would have been a cozy duopoly, drastically reducing the profitability of the 180-day exclusivity period for its primary challenger, Ranbaxy.

The outcome was as swift as it was brutal. Despite Pfizer’s aggressive tactics, the financial impact was staggering. Lipitor’s worldwide revenues plummeted by 59% in a single year, falling from $9.6 billion in 2011 to just $3.9 billion in 2012. The Lipitor case serves as the ultimate illustration of the sheer financial force of a patent cliff and provides a masterclass in the defensive strategies—from brand loyalty and rebate wars to the authorized generic play—that formulary managers must anticipate from innovator companies.14

Case Study 2: Gleevec (Imatinib) – The Specialty Drug Conundrum

If Lipitor was the classic blockbuster cliff, Novartis’s Gleevec represents the modern specialty drug conundrum. Hailed as a “miracle” drug for its revolutionary effectiveness against chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), Gleevec also came with a notoriously high and escalating price tag, rising from about $30,000 per year at its 2001 launch to over $120,000 per year by 2016, the year its first generic competitor entered the market.65

The Gleevec case offers a profoundly different, and perhaps more important, lesson for today’s formulary managers: the savings from generic entry are not automatic. The case highlights a dangerous disconnect between the wholesale price of a generic and the actual price paid by health plans and patients.

The data on the generic’s wholesale cost is unambiguous. Following the first generic entry by Sun Pharma in February 2016, and subsequent entry by other manufacturers, the wholesale acquisition cost (as measured by the National Average Drug Acquisition Cost, or NADAC) for imatinib plummeted. Within two years, the price had fallen by 89% from its initial generic level. By all standard models, this should have generated massive savings for the healthcare system.

However, the reality for payers and patients was starkly different. A study published in Health Affairs found that after nearly two years of generic competition, the net price paid for a month of treatment had dropped by only 10%. Further analysis of state Medicaid data revealed a shocking disparity: some state managed care programs were paying nearly the full brand price for the generic drug. In the first quarter of 2018, the cost per pill in Washington state’s program was $108, while in Indiana, it was an astonishing $295—nearly three times higher, and well above the drug’s actual acquisition cost.

What explains this massive disconnect? The Gleevec case is a cautionary tale about the complexities of the pharmaceutical supply chain and the critical importance of PBM contract management. The enormous potential savings were being absorbed somewhere in the middle, through mechanisms like “spread pricing,” where a PBM pays the pharmacy a low price for the generic but charges the health plan a much higher price, pocketing the difference. The case also highlighted the impact of brand loyalty in the specialty space; one study noted that 24% of imatinib prescriptions were still being filled with a “dispense as written” order, indicating that physicians or patients were actively resisting the switch to the generic.

The lesson for formulary managers is clear and urgent: the entire predictive framework for anticipating generic entry and price drops is only the first half of the equation. The second, equally critical half is ensuring those savings are actually captured. The Gleevec case proves that winning the prediction game is useless if you lose the contracting game. It underscores the absolute necessity of sophisticated PBM contract negotiation, demanding transparency, and conducting rigorous audits to ensure that the hard-won savings from generic competition flow through to the plan and its members, rather than being siphoned off within the supply chain.65

Strategic Synthesis: The Proactive Formulary Management Playbook

Anticipating and navigating the patent cliff is not an academic exercise; it is a core business function that demands a systematic, data-driven, and proactive approach. The insights gleaned from the legal framework, litigation tracking, and market dynamics must be synthesized into a coherent, actionable strategy. This playbook provides a step-by-step guide for transforming your formulary management team from a reactive cost center into a proactive value-creation engine.

Building Your Competitive Intelligence Engine

Success begins with information superiority. You cannot manage what you do not measure, and you cannot anticipate what you do not track. Building a robust competitive intelligence engine is the foundational step.

- Essential Data Sources: Your team must have routine, systematic access to a core set of data sources. This includes:

- FDA Databases: The Orange Book for patent and exclusivity data, the Paragraph IV Certifications List to identify first challengers, and the Drugs@FDA database for monthly approval reports are non-negotiable starting points.70

- Financial and Legal Filings: Routinely monitor SEC filings (10-K, 10-Q, 8-K) for brand company disclosures of PIV notices and litigation updates. Access to federal court dockets, such as PACER, is necessary to track key litigation milestones.

- Integrated Intelligence Platforms: To avoid being overwhelmed by disparate data, leveraging a professional-grade platform like DrugPatentWatch is essential. These services aggregate and synthesize patent, regulatory, and litigation data into a single, actionable dashboard, providing the critical efficiency and depth needed for timely decision-making.26

- The Cross-Functional Team: This data is useless without the right people to interpret it. Effective patent cliff management requires a dedicated, cross-functional team that breaks down internal silos. This team should include experts from pharmacy (to assess clinical interchangeability), legal (to interpret patent and litigation data), and finance/analytics (to model the budget impact).

The 4-Step Forecasting Process

With your intelligence engine in place, you can implement a structured forecasting process for any key brand drug in your portfolio.

- Step 1: Map the Exclusivity Landscape. For every high-spend brand drug, your first step is to build a comprehensive “exclusivity map.” Go beyond the primary patent. Using the Orange Book and other sources, identify every single patent (composition of matter, formulation, method of use) and every regulatory exclusivity (NCE, Pediatric, Orphan) and their respective expiration dates. This creates a baseline “last possible date” for generic entry and highlights the complexity of the patent thicket you are facing.32

- Step 2: Monitor for the First Signal (PIV Filing). The moment a PIV challenge is identified (via SEC filings, the FDA’s list, or your intelligence platform), the forecast changes dramatically. This is your first concrete signal of a potential early entry. Immediately start the 30-month countdown clock from the date of the ensuing lawsuit and begin modeling a more aggressive timeline.26

- Step 3: Track Litigation & Settlement. Follow the case through the key milestones: the Markman hearing, summary judgment motions, and district court decisions. Each event provides new data to refine the probability of an early launch. Be prepared for a settlement announcement at any time. When it comes, it provides a firm, contractual launch date, removing nearly all uncertainty. Your job then becomes to analyze the settlement’s terms, paying close attention to no-AG clauses or other signs of pay-for-delay that will impact initial pricing.49

- Step 4: Identify All Challengers. Do not make the mistake of only tracking the first filer. The steepness of the price erosion curve is a direct function of the number of competitors. Use the FDA’s PIV list and other sources to identify every generic applicant challenging the brand. Knowing whether you are facing a single challenger or a wave of five or more is the critical variable needed to accurately model the financial impact.24

Translating Forecasts into Formulary Strategy

Forecasting is not the end goal; it is the input for action. This intelligence must be translated into tangible formulary and contracting strategies.

- Dynamic Budgeting: Use the price erosion model detailed in the previous section, combined with your forecast of the number of competitors, to create accurate, data-driven budget impact analyses. Move from static annual budgets to dynamic forecasts that can be updated with each new piece of litigation or regulatory intelligence.

- Proactive Tier Design: Do not wait for the generic to launch to decide on its formulary placement. Months in advance, plan to move the upcoming generic to the most favorable tier (e.g., Tier 1) with the lowest member cost-sharing. Communicate this planned change to your provider network to encourage rapid adoption and maximize savings from day one.

- Strategic Utilization Management (UM): For high-cost brands where generic entry is significantly delayed—either due to a strong patent thicket, protracted litigation, or a pay-for-delay settlement—you cannot afford to wait passively. Use this intelligence to justify implementing or tightening UM controls, such as prior authorization or step therapy requiring the trial of other cost-effective agents first, to manage spend in the interim.1

- Leveraged Contract Negotiations: Your competitive intelligence is a powerful negotiating tool.

- With Brand Manufacturers: As a brand’s patent cliff approaches, its desperation to secure volume increases. Use your knowledge of the impending generic entry as leverage to negotiate higher rebates and more favorable terms in the final years of its exclusivity.

- With Your PBM: The Gleevec case is your mandate. Armed with data on when a generic is coming and what its wholesale price should be, you must negotiate PBM contracts that guarantee transparency and ensure that the savings are passed through to your plan and members. Demand clear definitions of cost, audit rights, and protections against spread pricing.

A Final Word: From Prediction to Value Creation

The ultimate goal of this playbook is to empower a fundamental shift in mindset. It is about moving from being a price-taker to a market-shaper. By mastering the rules of the game, building a robust intelligence engine, and translating predictive insights into proactive strategies, formulary leaders can do more than just save money. You can unlock billions of dollars in value that can be reinvested into lower premiums, reduced patient out-of-pocket costs, and expanded access to innovative care. The patent cliff is not a problem to be weathered; it is a strategic opportunity to be seized. The work is complex, but the rewards—for your organization and for the members you serve—are immense.

Key Takeaways

- Formulary management is a strategic function, not an administrative task. It requires a deep understanding of legal, regulatory, and commercial market dynamics to balance cost, access, and quality.

- The “Exclusivity Stack” is the true barrier to entry. Predicting generic launch requires analyzing a complex web of patents (compound, formulation, method of use) and regulatory exclusivities (NCE, Pediatric, Orphan), not just a single patent expiration date.

- A Paragraph IV (PIV) filing is the earliest, most reliable signal of a patent challenge. Tracking PIV notices via SEC filings, FDA lists, and intelligence platforms like DrugPatentWatch is the first step in proactive planning.

- The number of competitors dictates price erosion. The entry of the first generic leads to modest discounts. Significant price drops of 80% or more only occur with the entry of three to four or more competitors. This model is crucial for accurate budget forecasting.

- Authorized Generics (AGs) are a critical brand defense. They lower prices for payers but devastate first-filer generic revenues, making the threat of an AG a powerful bargaining chip in “pay-for-delay” settlement negotiations.

- Litigation and settlements provide firm launch dates. While complex, tracking litigation milestones (Markman hearings) and, most importantly, settlement announcements, transforms uncertain forecasts into concrete timelines.

- Generic savings are not automatic. As the Gleevec case proves, without transparent and well-structured PBM contracts, the massive savings from generic price drops can be lost in the supply chain. Forecasting must be paired with rigorous contract management.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. How can I assess the likely strength of a brand’s patents to predict if a PIV challenge will be successful?

Assessing patent strength requires a multi-faceted analysis. First, examine the type of patent. Composition of Matter (API) patents are the strongest and hardest to invalidate. Method of Use and Formulation patents are generally considered weaker and more susceptible to being “designed around” by a generic competitor.26 Second, look at the litigation history of the patent holder and the specific patents. Have these patents been challenged before in the U.S. or other jurisdictions? Third, monitor for proceedings at the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB), specifically Inter Partes Reviews (IPRs). An IPR is a faster, lower-cost way for a generic to challenge a patent’s validity. The filing of an IPR is a strong signal of the generic’s confidence, and a PTAB decision to institute a review suggests the patent has significant vulnerabilities. Finally, the number of PIV filers is a powerful proxy for perceived weakness; if multiple major generic companies all challenge the same patents, it signals a broad industry consensus that the patents are vulnerable.

2. How do biosimilars fit into this framework, and how does their entry differ from small-molecule generics?

While the strategic principles are similar, biosimilar entry has key differences. Biologics are large, complex molecules, and biosimilars are “highly similar,” not identical copies like small-molecule generics. This leads to several distinctions. First, the approval pathway (the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act, or BPCIA) is more complex and costly, leading to fewer competitors. Second, price erosion is much slower. Instead of the 80-90% drops seen with generics, biosimilar entry typically leads to price reductions of only 20-40%. Third, and most critically, automatic substitution at the pharmacy is not a given. A biosimilar must be designated as “interchangeable” by the FDA to be substituted without a new prescription, a high bar that few have met. This means physician and patient acceptance play a much larger role, and uptake is slower. Therefore, while you track patent expirations (listed in the FDA’s “Purple Book” for biologics), your financial models must assume fewer competitors, less steep price decay, and slower market conversion.

3. My PBM claims their rebate negotiations lower our overall drug spend. How can I verify this and protect my plan from the “Gleevec scenario”?

This is the central challenge. To verify PBM claims and avoid the Gleevec scenario, you must demand radical transparency in your contracts. This includes several key elements: 1) A clear, pass-through pricing model: Your contract should specify that you pay the pharmacy the actual acquisition cost plus a fixed dispensing fee, eliminating “spread pricing.” 2) Full rebate transparency: Demand 100% of all manufacturer rebates, discounts, and administrative fees be passed directly to the plan. Require detailed, drug-level reporting on all rebates received. 3) Audit rights: Your contract must include robust rights to audit the PBM’s claims processing, payments to pharmacies, and rebate collections. 4) Define “generic”: Ensure your contract clearly defines how generics are treated. Prevent situations where a PBM can classify a high-cost generic (like early Gleevec) as a “brand” to avoid lower generic dispensing rates or to apply brand-level rebates. By building these protections into your contract, you shift the focus from opaque rebate games to transparent, lowest-net-cost management.

4. What is a “skinny label,” and how can it accelerate generic entry even when some patents are still valid?

A “skinny label” is a powerful strategic tool for generic manufacturers to navigate a patent thicket. It allows a generic to launch even if a valid Method of Use patent for a specific indication is still in effect.26 The generic company files a “Section viii statement” with the FDA, essentially stating it will not seek approval for the patent-protected indication. The FDA then approves the generic with a “carved-out” or “skinny” label that omits the protected use. For example, if a brand drug is approved for both hypertension (off-patent) and heart failure (on-patent), a generic can launch with a label that only lists the hypertension indication. This allows it to enter the market and compete for the majority of the drug’s sales years before the final patent expires. For formulary managers, identifying the potential for a skinny label launch—by comparing a drug’s various indications with its method-of-use patent expiration dates—can reveal opportunities for generic entry that are not apparent from looking at the last-to-expire patent alone.

5. If a brand company loses its patent case in district court, can I assume the generic will launch immediately?

Not necessarily. A district court loss for the brand lifts the 30-month stay, but the brand company will almost certainly appeal the decision to the Federal Circuit, a process that can take another 12-18 months. This creates a period of significant “at-risk launch” consideration for the generic company. If the generic launches after the district court win but the decision is later reversed on appeal, the generic company could be liable for massive damages for patent infringement. Therefore, many generic companies, particularly for smaller products, may choose to wait for the appeal to be resolved before launching. For a blockbuster drug, however, the potential profits from an at-risk launch are often so immense that a generic company may be willing to take the risk. As a formulary manager, a district court win for the generic should prompt you to prepare for an imminent launch, but you must also factor in the risk appetite of the specific generic manufacturer involved.

References

- A primer on formulary structures and strategies – PMC, accessed August 2, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10838136/

- Formulary Management | AMCP.org, accessed August 2, 2025, https://www.amcp.org/concepts-managed-care-pharmacy/formulary-management

- Behind the Prescription: The Quiet Revolution in Formulary Management – Pharmacy Times, accessed August 2, 2025, https://www.pharmacytimes.com/view/behind-the-prescription-the-quiet-revolution-in-formulary-management

- A Formulary Management Group Consensus | Global Journal on Quality and Safety in Healthcare – Allen Press, accessed August 2, 2025, https://meridian.allenpress.com/innovationsjournals-JQSH/article/7/2/88/499009/A-Formulary-Management-Group-Consensus

- AMCP Partnership Forum: Principles for Sound Pharmacy and …, accessed August 2, 2025, https://www.jmcp.org/doi/10.18553/jmcp.2020.26.1.48

- Pharmacy and Therapeutics Committee Policies and Procedures – HealthPartners, accessed August 2, 2025, https://www.healthpartners.com/ucm/groups/public/@hp/@public/documents/documents/cntrb_043361.pdf

- PBM Basics – Pharmacists Society of the State of New York, accessed August 2, 2025, https://www.pssny.org/page/PBMBasics

- 5 Things To Know About Pharmacy Benefit Managers – Center for American Progress, accessed August 2, 2025, https://www.americanprogress.org/article/5-things-to-know-about-pharmacy-benefit-managers/

- What Pharmacy Benefit Managers Do, and How They Contribute to Drug Spending, accessed August 2, 2025, https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/explainer/2025/mar/what-pharmacy-benefit-managers-do-how-they-contribute-drug-spending

- The Role of PBMs in the US Healthcare System – Avalere Health Advisory, accessed August 2, 2025, https://advisory.avalerehealth.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/The-Role-of-PBMs-in-the-US-Healthcare-System_White-Paper.pdf

- Testimony of Juan Carlos “JC” Scott President and Chief Executive …, accessed August 2, 2025, https://www.judiciary.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/2025-05-13_testimony_scott.pdf

- Pharmacy Benefit Managers Practices Controversies What Lies Ahead, accessed August 2, 2025, https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2019/mar/pharmacy-benefit-managers-practices-controversies-what-lies-ahead

- Hearing Wrap Up: Pharmacy Benefit Managers Push Anticompetitive Drug Pricing Tactics to Line Their Own Pockets – United States House Committee on Oversight and Accountability, accessed August 2, 2025, https://oversight.house.gov/release/hearing-wrap-up-pharmacy-benefit-managers-push-anticompetitive-drug-pricing-tactics-to-line-their-own-pockets%EF%BF%BC/

- What is a patent cliff, and how does it impact companies? – Patsnap Synapse, accessed August 2, 2025, https://synapse.patsnap.com/article/what-is-a-patent-cliff-and-how-does-it-impact-companies

- The End of Exclusivity: Navigating the Drug Patent Cliff for Competitive Advantage – DrugPatentWatch – Transform Data into Market Domination, accessed August 2, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-impact-of-drug-patent-expiration-financial-implications-lifecycle-strategies-and-market-transformations/

- Patent Defense Isn’t a Legal Problem. It’s a Strategy Problem. Patent Defense Tactics That Every Pharma Company Needs – Drug Patent Watch, accessed August 2, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/patent-defense-isnt-a-legal-problem-its-a-strategy-problem-patent-defense-tactics-that-every-pharma-company-needs/

- 40th Anniversary of the Generic Drug Approval Pathway | FDA, accessed August 2, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/cder-conversations/40th-anniversary-generic-drug-approval-pathway

- Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act – Wikipedia, accessed August 2, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Drug_Price_Competition_and_Patent_Term_Restoration_Act

- Hatch-Waxman 101 – Fish & Richardson, accessed August 2, 2025, https://www.fr.com/insights/thought-leadership/blogs/hatch-waxman-101-3/

- HOW INCREASED COMPETITION FROM GENERIC DRUGS HAS AFFECTED PRICES AND RETURNS IN THE PHARMACEUTICAL INDUSTRY JULY 1998 – Congressional Budget Office, accessed August 2, 2025, https://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/cbofiles/ftpdocs/6xx/doc655/pharm.pdf

- The ANDA Process: A Guide to FDA Submission & Approval – Excedr, accessed August 2, 2025, https://www.excedr.com/blog/what-is-abbreviated-new-drug-application

- Abbreviated New Drug Applications (ANDA) Explained: A Quick-Guide – The FDA Group, accessed August 2, 2025, https://www.thefdagroup.com/blog/abbreviated-new-drug-applications-anda

- ANDA Submissions — Content and Format Guidance for Industry Rev. 1 – FDA, accessed August 2, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/media/128127/download

- The Impact of Generic Drugs on Healthcare Costs – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 2, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-impact-of-generic-drugs-on-healthcare-costs/

- The Hatch-Waxman Act: A Primer – EveryCRSReport.com, accessed August 2, 2025, https://www.everycrsreport.com/reports/R44643.html

- The Pre-Approval Playbook: How to Identify Generic Entrants and …, accessed August 2, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/customer-success-how-do-we-identify-generic-entrants-before-they-get-fda-approval/

- The Generic Drug Approval Process – FDA, accessed August 2, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/cder-conversations/generic-drug-approval-process

- The Definitive Guide to Generic Drug Approval in the U.S.: From ANDA to Market Dominance – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 2, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/obtaining-generic-drug-approval-in-the-united-states/

- 7 FAQs About Generic Drugs | Pfizer, accessed August 2, 2025, https://www.pfizer.com/news/articles/7_faqs_about_generic_drugs

- Navigating the ANDA and FDA Approval Processes – bioaccess, accessed August 2, 2025, https://www.bioaccessla.com/blog/navigating-the-anda-and-fda-approval-processes

- Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) Forms and Submission Requirements – FDA, accessed August 2, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/abbreviated-new-drug-application-anda/abbreviated-new-drug-application-anda-forms-and-submission-requirements

- How to own a Market you Don’t Own: Market Access Strategies Post-Patent Expiration, accessed August 2, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/how-to-own-a-market-you-dont-own-market-access-strategies-post-patent-expiration/

- The Hard Truth About Patent Strategy in a Formulary World …, accessed August 2, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/formulary-management-and-lcm-patent-strategies-a-complex-interaction/

- How Drug Life-Cycle Management Patent Strategies May Impact Formulary Management, accessed August 2, 2025, https://www.ajmc.com/view/a636-article

- The Role of Patents and Regulatory Exclusivities in Drug Pricing | Congress.gov, accessed August 2, 2025, https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/R46679

- The Patent Playbook Your Lawyers Won’t Write: Patent strategy development framework for pharmaceutical companies – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 2, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-patent-playbook-your-lawyers-wont-write-patent-strategy-development-framework-for-pharmaceutical-companies/

- Patent Litigation in the Pharmaceutical Industry: Key Considerations, accessed August 2, 2025, https://patentpc.com/blog/patent-litigation-in-the-pharmaceutical-industry-key-considerations

- Paragraph IV Explained – ParagraphFour.com, accessed August 2, 2025, https://paragraphfour.com/paragraph-iv-explained/

- Patent Certifications and Suitability Petitions – FDA, accessed August 2, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/abbreviated-new-drug-application-anda/patent-certifications-and-suitability-petitions

- Paragraph IV Filings & ANDA Explained – Minesoft, accessed August 2, 2025, https://minesoft.com/paragraph-iv-filings-generic-drugs-big-pharma/

- Find Your Next Blockbuster – Biotech & Pharmaceutical patents …, accessed August 2, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/about.php

- DrugPatentWatch | Software Reviews & Alternatives – Crozdesk, accessed August 2, 2025, https://crozdesk.com/software/drugpatentwatch

- Hatch-Waxman Act – Practical Law, accessed August 2, 2025, https://uk.practicallaw.thomsonreuters.com/Glossary/PracticalLaw/I2e45aeaf642211e38578f7ccc38dcbee

- The Law of 180-Day Exclusivity (Open Access) – Food and Drug Law …, accessed August 2, 2025, https://www.fdli.org/2016/09/law-180-day-exclusivity/

- GENERIC DRUGS IN THE UNITED STATES: POLICIES TO …, accessed August 2, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6355356/

- Authorized Generics In The US: Prevalence, Characteristics, And Timing, 2010–19, accessed August 2, 2025, https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/10.1377/hlthaff.2022.01677

- Authorized Generic Drugs: Short-Term Effects and Long-Term Impact | Federal Trade Commission, accessed August 2, 2025, https://www.ftc.gov/sites/default/files/documents/reports/authorized-generic-drugs-short-term-effects-and-long-term-impact-report-federal-trade-commission/authorized-generic-drugs-short-term-effects-and-long-term-impact-report-federal-trade-commission.pdf

- Authorized Generic Pharmaceuticals: Effects on Innovation – Every CRS Report, accessed August 2, 2025, https://www.everycrsreport.com/files/20060808_RL33605_614fbabb10204df97b150df1964ef6956ffdf726.pdf

- FTC Report Examines How Authorized Generics Affect the …, accessed August 2, 2025, https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/news/press-releases/2011/08/ftc-report-examines-how-authorized-generics-affect-pharmaceutical-market

- Most-Favored Entry Clauses in Drug-Patent Litigation Settlements: A Reply to Drake and McGuire (2022) – American Bar Association, accessed August 2, 2025, https://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/publications/antitrust/magazine/2023/december/most-favored-entry-clauses.pdf

- ANDA Litigation: Strategies and Tactics for Pharmaceutical Patent Litigators, accessed August 2, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/anda-litigation-strategies-and-tactics-for-pharmaceutical-patent-litigators/

- Pharmaceutical Patent Litigation Settlements: Implications for Competition and Innovation, accessed August 2, 2025, https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub/574/

- Entry limiting agreements: first mover advantage, authorized generics and pay-for-delay deals – University of East Anglia, accessed August 2, 2025, https://research-portal.uea.ac.uk/files/181549656/bmp2014_1_v04f.pdf

- Are Settlements in Patent Litigation Collusive? Evidence from …, accessed August 2, 2025, https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w22194/w22194.pdf

- NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES USING STOCK PRICE MOVEMENTS TO ESTIMATE THE HARM FROM COLLUSIVE DRUG PATENT LITIGATION SETTLEMENTS Kei, accessed August 2, 2025, https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w33196/w33196.pdf

- Do “Reverse Payment” Settlements of Brand-Generic Patent Disputes in the Pharmaceutical Industry Constitute an Anticompetitive Pay for Delay? – NBER, accessed August 2, 2025, https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w20292/w20292.pdf

- Most-Favored Entry Clauses in Drug-Patent Litigation Settlements | Cornerstone Research, accessed August 2, 2025, https://www.cornerstone.com/insights/articles/most-favored-entry-clauses-in-drug-patent-litigation-settlements/

- Drug Competition Series – Analysis of New Generic … – HHS ASPE, accessed August 2, 2025, https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/510e964dc7b7f00763a7f8a1dbc5ae7b/aspe-ib-generic-drugs-competition.pdf

- Price Declines after Branded Medicines Lose Exclusivity in the US – IQVIA, accessed August 2, 2025, https://www.iqvia.com/-/media/iqvia/pdfs/institute-reports/price-declines-after-branded-medicines-lose-exclusivity-in-the-us.pdf

- Effects of Generic Entry on Market Shares and Prices of Originator Drugs – PubMed Central, accessed August 2, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12209137/

- Generic pharmaceutical price decay – Wikipedia, accessed August 2, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Generic_pharmaceutical_price_decay

- Another Lurking Patent Cliff: Industry Challenges and Strategies for the Future – Medium, accessed August 2, 2025, https://medium.com/@gianlucaradesich/another-lurking-patent-cliff-industry-challenges-and-strategies-for-the-future-ef73ca405aa1

- Case study: how Sanofli dealt with the patent cliff | Business Valuation Resources, accessed August 2, 2025, https://www.bvresources.com/blogs/intellectual-property-news/2011/11/09/case-study-how-sanofli-dealt-with-the-patent-cliff

- Patent cliff and strategic switch: exploring strategic design possibilities in the pharmaceutical industry – PMC, accessed August 2, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4899342/

- Cost savings from the use of generic Gleevec (imatinib), accessed August 2, 2025, https://gabionline.net/generics/research/Cost-savings-from-the-use-of-generic-Gleevec-imatinib

- Generic imatinib — impact on frontline and salvage therapy for CML – PMC, accessed August 2, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5450934/

- The cancerous design of the U.S. drug pricing system – 46brooklyn Research, accessed August 2, 2025, https://www.46brooklyn.com/research/2018/7/23/the-cancerous-design-of-the-us-drug-pricing-system

- Study finds generic options offer limited savings for expensive drugs – VUMC News, accessed August 2, 2025, https://news.vumc.org/2018/05/09/study-finds-generic-options-offer-limited-savings-for-expensive-drugs/

- Realized and Projected Cost-Savings from the Introduction of Generic Imatinib Through Formulary Management in Patients with Chronic Myelogenous Leukemia – PMC, accessed August 2, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6996618/

- Search Databases – FDA, accessed August 2, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/industry/fda-basics-industry/search-databases

- Drug Approvals and Databases | FDA, accessed August 2, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/development-approval-process-drugs/drug-approvals-and-databases

- Generic Drugs Program Monthly and Quarterly Activities Report | FDA, accessed August 2, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/industry/generic-drug-user-fee-amendments/generic-drugs-program-monthly-and-quarterly-activities-report

- Will Biosimilars Help Save Employers Money?, accessed August 2, 2025, https://www.bbrown.com/us/insight/will-biosimilars-help-save-employers-money/

- Small Business Assistance | 180-Day Generic Drug Exclusivity – FDA, accessed August 2, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/cder-small-business-industry-assistance-sbia/small-business-assistance-180-day-generic-drug-exclusivity

- A primer on formulary structures and strategies | Journal of Managed Care & Specialty Pharmacy – JMCP.org, accessed August 2, 2025, https://www.jmcp.org/doi/10.18553/jmcp.2024.30.2.206

- Strategic Directions in System Formulary, Drug Policy, and High-Cost Drug Management – ASHP, accessed August 2, 2025, https://www.ashp.org/-/media/assets/about-ashp/docs/PELA/ASHP-PELA-Virtual-Strategic-Directions-System-PT-Drug-Policy-High-Cost-Drugs-Whitepaper.pdf

- The Role of Pharmacy Benefit Managers in Formulary Design: Service Providers or Fiduciaries? – PMC, accessed August 2, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10438040/

- Understanding the Role of Pharmacy Benefit Managers in Healthcare – Elevance Health, accessed August 2, 2025, https://www.elevancehealth.com/content/dam/elevance-health/articles/ppi_assets/55/EHPPI_PBM_r5_Final.pdf

- Hatch-Waxman Letters – FDA, accessed August 2, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/abbreviated-new-drug-application-anda/hatch-waxman-letters

- Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) Consulting Services – The FDA Group, accessed August 2, 2025, https://www.thefdagroup.com/services/anda

- Inside P&T committees: The key players in formulary decision-making – Definitive Healthcare, accessed August 2, 2025, https://www.definitivehc.com/blog/pharmacy-and-therapeutics-committee

- A Method for Approximating Future Entry of Generic Drugs – PubMed, accessed August 2, 2025, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30502781/

- Estimating the Timing of Future Generic Drug Entry- Study Reports Accuracy of New Prediction Method – ISPOR, accessed August 2, 2025, https://www.ispor.org/heor-resources/news-top/news/view/2018/12/18/estimating-the-timing-of-future-generic-drug-entry-study-reports-accuracy-of-new-prediction-method

- DrugPatentWatch Pricing, Features, and Reviews (Jul 2025) – Software Suggest, accessed August 2, 2025, https://www.softwaresuggest.com/drugpatentwatch

- DrugPatentWatch 2025: Reviews, Press Coverage, and Pricing | LawNext Directory, accessed August 2, 2025, https://directory.lawnext.com/products/drugpatentwatch/

- Drug Safety Communications – FDA, accessed August 2, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/drug-safety-communications

- Generic Drug Development | FDA, accessed August 2, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/abbreviated-new-drug-application-anda/generic-drug-development

- Office of Generic Drugs – FDA, accessed August 2, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/about-fda/cder-offices-and-divisions/office-generic-drugs

- Understanding Recent Trends in Generic Drug Prices – HHS ASPE, accessed August 2, 2025, https://aspe.hhs.gov/reports/understanding-recent-trends-generic-drug-prices

- Prescription Drugs | Congressional Budget Office, accessed August 2, 2025, https://www.cbo.gov/topics/health-care/prescription-drugs

- CBO Report on Prescription Drug Trends – Pharmaceutical Care Management Association, accessed August 2, 2025, https://www.pcmanet.org/rx-research-corner/cbo-report-on-prescription-drug-trends/03/23/2022/

- Drug Competition Series: Analysis of New Generic Markets Effect of Market Entry on Generic Drug Prices: Medicare Data 2007-2022 – HHS ASPE, accessed August 2, 2025, https://aspe.hhs.gov/reports/analysis-new-generic-markets-effect-market-entry-generic-drug-prices

- Standing Committee on Health – House of Commons, accessed August 2, 2025, https://www.ourcommons.ca/Content/Committee/421/HESA/Evidence/EV8279873/HESAEV11-E.PDF

- Discussions of Health Web Sites in Medical and Popular Media – University of Pennsylvania, accessed August 2, 2025, https://repository.upenn.edu/bitstreams/9ddbf52a-a42d-4630-8f8a-3c720319644e/download

- Tobacco-Free Toolkit for Behavioral Health Agencies – State of Michigan, accessed August 2, 2025, https://www.michigan.gov/-/media/Project/Websites/mdhhs/Folder3/Folder93/Folder2/Folder193/Folder1/Folder293/Tobacco-Free_Toolkit_for_Behavioral_Health_Agencies.pdf?rev=dc1eeb256dd940bb8c26101356f6b103

- Health Information Technology Oversight Council – Oregon.gov, accessed August 2, 2025, https://www.oregon.gov/oha/HPA/OHIT-HITOC/HITOC%20Meeting%20Docs/20111006_MeetingMaterials.pdf

- Medicine Is About to Get Personal – Time Magazine, accessed August 2, 2025, https://time.com/3643841/medicine-gets-personal/

- A Blueprint for Pharmacy Benefit Managers to Increase Value – PMC – PubMed Central, accessed August 2, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2737824/

- FTC Releases Interim Staff Report on Prescription Drug Middlemen, accessed August 2, 2025, https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/news/press-releases/2024/07/ftc-releases-interim-staff-report-prescription-drug-middlemen

- The Evolution of Patent Claims in Drug Lifecycle Management – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 2, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-evolution-of-patent-claims-in-drug-lifecycle-management/

- STAT quotes Sherkow on pharmaceutical patents – College of Law, accessed August 2, 2025, https://law.illinois.edu/stat-quotes-sherkow-on-pharmaceutical-patents/

- The Unseen Engine of Healthcare: A Comprehensive Review of …, accessed August 2, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/development-of-generic-drug-products-by-pharmaceutical-industries-considering-regulatory-aspects-a-review/

- AAM Update on the Status of Generic Drugs – U.S. Pharmacist, accessed August 2, 2025, https://www.uspharmacist.com/article/aam-update-on-the-status-of-generic-drugs

- Generic Drugs – FDA – Regulations.gov, accessed August 2, 2025, https://downloads.regulations.gov/EPA-HQ-OAR-2024-0196-0003/attachment_87.pdf

- Are Generic Drugs Just As Good As Branded Drugs? – HealthMatch, accessed August 2, 2025, https://healthmatch.io/blog/are-generic-drugs-just-as-good-as-branded-drugs

- The Honorable Melissa Wiklund, Chair, Health and Human Services Committee Minnesota … – Minnesota Senate, accessed August 2, 2025, https://www.senate.mn/committees/2025-2026/3123_Committee_on_Health_and_Human_Services/Prime-Therapeutics_SF1876_Oppose-324251719626561.pdf

- Authorized Generic Pharmaceuticals: Effects on Innovation – IP Mall, accessed August 2, 2025, https://ipmall.law.unh.edu/sites/default/files/hosted_resources/crs/RL33605_080110.pdf

- Federal Trade Commission Reports: Authorized Generics, during the 180-day Exclusivity Period, Benefit Consumers and the American Healthcare System – Prasco.com, accessed August 2, 2025, https://prasco.com/federal-trade-commission-reports-authorized-generics-during-the-180-day-exclusivity-period-benefit-consumers-and-the-american-healthcare-system/