I. Executive Summary

The modern pharmaceutical landscape is defined by a paradox of immense opportunity and unprecedented risk. While breakthrough innovations in biologics, cell therapies, and AI-driven drug discovery promise to revolutionize medicine, the economic model underpinning this progress is under constant pressure. This report provides a comprehensive, expert-level analysis of the strategic framework required to navigate this environment: the pharmaceutical patent fortress. It posits that contemporary intellectual property (IP) strategy has evolved far beyond the simple protection of an invention. It is now a highly sophisticated, multi-disciplinary function of lifecycle management, competitive warfare, and commercial optimization, essential for securing a return on investment (ROI) in an industry where development costs are astronomical and market exclusivity windows are perpetually shrinking.

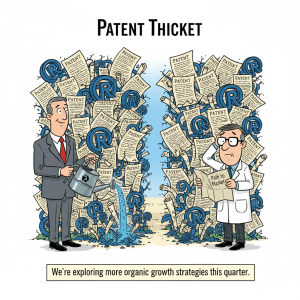

The central thesis of this analysis is that a single patent is no longer sufficient. Success requires the construction of a “patent fortress”—a meticulously layered portfolio of composition of matter, method of use, formulation, and process patents. This “thicket” of overlapping IP is designed not only to protect the core innovation but also to create a formidable deterrent to generic and biosimilar competition, a strategy exemplified by AbbVie’s multi-billion-dollar defense of HUMIRA®. This report deconstructs the anatomy of such fortresses and the controversial but legally affirmed practice of “evergreening.”

A deep dive into the U.S. regulatory-patent interface reveals the critical interplay between the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO). The Hatch-Waxman Act for small molecules and the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA) for biologics are dissected not as mere legal frameworks, but as strategic battlegrounds. Mechanisms such as Patent Term Extension (PTE), regulatory exclusivities (e.g., New Chemical Entity, Orphan Drug), the 30-month litigation stay, and the BPCIA’s “patent dance” are analyzed as essential tools for maximizing commercial longevity.

Recognizing that the pharmaceutical market is global, this report extends its analysis to the key international arenas of the European Union, China, and India. It contrasts their divergent legal and regulatory philosophies—from the EU’s Supplementary Protection Certificates (SPCs) and the new Unified Patent Court (UPC) to China’s pro-enforcement patent linkage system and India’s formidable Section 3(d) barrier against secondary patents. The analysis demonstrates how sophisticated players engage in a form of “geographic arbitrage,” leveraging favorable outcomes in one jurisdiction to influence litigation and commercial strategy in another.

Litigation is framed not as a failure of strategy, but as an integral component of it. Data-driven analysis of outcomes in U.S. District Courts, at the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB), and under the BPCIA reveals clear trends. The report explores how challengers strategically “forum shop” between venues to exploit different legal standards, forcing innovators to defend their IP on multiple fronts simultaneously.

Furthermore, this report argues for a paradigm shift in the use of patent data, transforming it from a defensive legal tool into a proactive commercial weapon. Patent analytics, Freedom-to-Operate (FTO) analysis, and competitive landscaping are presented as indispensable methods for de-risking R&D, identifying “white space” opportunities, and gaining a predictive edge by monitoring competitors’ patent-pending applications.

Finally, the analysis looks to the future, addressing the profound IP challenges and opportunities presented by emerging technologies. The patentability of AI-driven drug discoveries, the unique complexities of protecting cell and gene therapies, and the rise of digital therapeutics are examined. These new frontiers demand a hybrid IP strategy that converges patent law with data governance and trade secret management.

This report is designed for senior executives, in-house counsel, and business development leaders. It moves beyond theoretical concepts to provide a data-centric, ROI-focused framework for building, defending, and monetizing a patent fortress in a dynamic and intensely competitive global market. The ultimate conclusion is that a proactive, globally coordinated, and commercially integrated patent strategy is no longer just a legal necessity—it is the central pillar of sustainable value creation in the biopharmaceutical industry.

II. The Strategic Imperative: Patents as the Engine of Pharmaceutical ROI

The Grand Bargain: Balancing Innovation Incentives and Public Access

The global pharmaceutical industry operates on a foundational principle, a grand bargain between the innovator and society. This “quid pro quo” is the core of the patent system: in exchange for the complete public disclosure of a new and useful invention, the government grants the inventor a temporary, legally enforceable monopoly.1 This exclusive right to make, use, and sell the invention, typically for 20 years from the patent’s filing date, is not merely a certificate of achievement; it is the primary economic engine that fuels the entire biopharmaceutical ecosystem.3

This system is designed to solve a specific market failure inherent in pharmaceutical innovation. The process of discovering and developing a new medicine is extraordinarily expensive and fraught with risk, but the final product—the chemical compound—is often easy and cheap to replicate.5 Without the promise of a protected period of market exclusivity, generic manufacturers could immediately copy a new drug, sell it at a fraction of the price, and eliminate any possibility for the innovator to recoup their development costs. Consequently, the incentive to undertake the initial investment would vanish.6 Patents provide this crucial incentive, enabling companies to attract the massive capital required for research and development (R&D).6

However, this temporary monopoly inherently creates a tension between innovation and access.3 While the patent is in force, the lack of competition allows for premium pricing, which is necessary to fund future R&D but can restrict patient access to new medicines. Upon patent expiration, this tension is resolved as generic competition enters the market, often leading to dramatic price reductions of 80-90% within the first year.3 This dynamic underscores the dual purpose of the patent system: to foster “dynamic long-term efficiency in the form of greater innovation” while ensuring that, in the long run, those innovations become widely and affordably available.6 Understanding this fundamental balance is the prerequisite to formulating any effective patent strategy.

Quantifying the Stakes: The Modern Cost of Drug Development

The strategic necessity of a robust and sophisticated patent protection strategy is anchored in the staggering financial realities of modern drug development. The figures associated with bringing a new medicine from the laboratory to the patient bedside are immense and continue to escalate, making the ability to secure a return on investment a matter of corporate survival.

According to a comprehensive analysis by the U.S. Congressional Budget Office (CBO), the pharmaceutical industry’s investment in R&D has grown exponentially. In 2019, the industry expended $83 billion on R&D activities. When adjusted for inflation, this figure represents a tenfold increase compared to the average annual spending in the 1980s.8 This investment has yielded a corresponding increase in output, with the number of new drugs approved by the FDA between 2010 and 2019 rising by 60% compared to the previous decade.8

The cost per approved drug is equally daunting. The CBO estimates that the capitalized cost to develop a new drug—a figure that critically includes the cost of capital and accounts for the high rate of failures in the pipeline—ranges from under $1 billion to more than $2 billion.8 Other analyses, which factor in the full cost of failed candidates that never reach the market, place the figure even higher, approaching $4 billion.4 This high attrition rate is a defining feature of the industry; for every single drug that successfully navigates the multi-year gauntlet of preclinical studies and human clinical trials, many others fail, and the revenue from the one success must cover the losses of all the failures.9

This level of investment is reflected in the financial structures of major pharmaceutical companies. Industry leaders such as Merck, Pfizer, and Johnson & Johnson consistently reinvest a substantial portion of their revenues back into R&D, with expenditures often ranging from 15% to over 28% of their total sales.4 This ratio far exceeds the R&D spending of other manufacturing sectors; even R&D-intensive industries like software and semiconductors spend less than 20% of net revenue on innovation.10

These figures directly inform the industry’s approach to pricing and patent protection. While the CBO notes that sunk R&D costs do not directly determine the launch price of a new drug, the expected lifetime global revenues—which are entirely dependent on the strength and duration of patent protection—are the primary consideration that justifies the initial R&D investment.8 Without a predictable period of market exclusivity to generate those revenues, the financial model collapses.

Beyond the Molecule: The Shift from a Single Patent to a Lifecycle Fortress Strategy

In response to the immense financial pressures and the compressed timeline for market exclusivity, the paradigm of pharmaceutical patent strategy has undergone a fundamental transformation. The historical model, which viewed patenting through a narrow, defensive lens of simply protecting a core invention, is now dangerously obsolete.1 The modern strategic approach has evolved from a “molecule-centric” focus on a single patent to a holistic, “lifecycle-centric” IP strategy.1

This evolution has given rise to the concept of the “patent fortress.” A single, successful drug is rarely, if ever, shielded by a single patent. Instead, it is protected by a meticulously constructed portfolio of patents, each with a distinct purpose, scope, and expiration date.4 This multi-layered “web of protection,” often referred to by critics as a “patent thicket,” is a deliberate and sophisticated strategy designed to create a formidable and near-impenetrable fortress around the innovation, making it exceedingly difficult for competitors to enter the market.4

This fortress is not built at a single point in time. It is constructed over the entire lifecycle of the drug, from early discovery through post-market improvements. The strategy involves layering different types of patents—covering the core molecule, its various formulations, its methods of manufacture, and its therapeutic uses—to create a dense and overlapping network of protection. The objective is to ensure that even when one patent expires, others remain in force, thereby extending the product’s overall period of commercial viability. This shift from a single defensive shield to an offensive, multi-layered fortress represents one of the most significant developments in the industry and is the central theme of modern pharmaceutical IP strategy.1

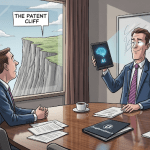

A critical driver for the development of these complex fortress strategies is the “effective patent life” paradox. The statutory 20-year patent term, which begins at the time of filing, is a highly misleading figure for strategic and financial planning.3 The arduous journey of drug development, which encompasses preclinical research, multiple phases of rigorous clinical trials, and a demanding regulatory review process, can easily consume 10 to 15 years of that term.4 As a result, the actual period of market exclusivity a company has from the moment a drug is approved to the moment its foundational patent expires—the “effective patent life”—is often only 7 to 10 years.7 This severely compressed commercial window is often insufficient to guarantee an adequate ROI on a multi-billion-dollar R&D investment. This paradox creates a powerful and unavoidable economic incentive for companies to employ every available legal and regulatory mechanism to extend this commercial window for as long as possible. The sophisticated and sometimes controversial strategies of lifecycle management, patent thicketing, and leveraging regulatory exclusivities are not peripheral activities; they are direct and logical responses to this fundamental structural challenge of the pharmaceutical business model.

III. The Building Blocks: A Strategic Analysis of Core Pharmaceutical Patents

A formidable patent fortress is constructed from several distinct but interconnected types of patents. Each serves a specific strategic purpose, and their combined strength lies in creating multiple, overlapping layers of protection. Understanding the function and value of each of these building blocks is essential for both the innovator seeking to construct the fortress and the competitor seeking to breach its walls.

The Foundation: Composition of Matter Patents

The bedrock of any pharmaceutical patent portfolio is the composition of matter patent.3 This is the most powerful and valuable form of protection, as it claims the novel chemical entity (NCE) or active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) itself.4 It is typically the first patent to be filed, often early in the discovery phase, and its 20-year term establishes the initial period of market exclusivity.3

The strategic power of a composition of matter patent lies in its breadth. It protects the molecule regardless of how it was manufactured, what it is formulated with, or for which disease it is being used.1 If the molecule is present in a competitor’s product, that product infringes the patent. This makes it the most difficult type of patent for a generic competitor to challenge or “design around”.4

To be granted, the invention must meet three stringent criteria:

- Novelty: The chemical compound must be new and not previously disclosed in any public forum.2

- Non-Obviousness (Inventive Step): The invention must not be an obvious modification of a known compound to a “person having ordinary skill in the art.” This is often the most contentious and heavily litigated requirement in pharmaceutical patent law.3

- Utility: The invention must have a specific, substantial, and credible utility. For a drug, this means it must have a demonstrated therapeutic effect or a clear potential for one.4

Securing a strong, defensible composition of matter patent is the primary objective of any early-stage drug patent strategy. It is the cornerstone upon which all subsequent layers of protection are built.4

Extending the Franchise: Method of Use & New Indication Patents

While the composition of matter patent protects the “what,” a method of use patent protects a specific “how”—a novel way of utilizing a known compound or drug.3 This type of patent is a cornerstone of strategic lifecycle management, particularly in the context of drug repurposing or repositioning.14

If a company discovers that a drug originally approved for one condition, such as hypertension, is also effective at treating an entirely different condition, like hair loss, it can obtain a new method-of-use patent for that new indication.4 A classic real-world example is Pfizer’s Viagra (sildenafil). Beyond the original compound patent, the company secured method-of-use patents specifically for the treatment of erectile dysfunction, which became the drug’s blockbuster indication and significantly extended its commercial life.4

These patents are strategically valuable because they can breathe new life into older compounds, opening up entirely new markets and revenue streams long after the initial indication was established.3 They allow companies to leverage existing safety and manufacturing data, reducing the cost and time of development for the new indication compared to developing a new chemical entity from scratch.

Enhancing the Product: Formulation and Delivery System Patents

Formulation patents protect the specific “recipe” or composition of the final drug product, rather than the active ingredient itself.3 These patents cover the unique combination of the API with various excipients (inactive ingredients) and the processes used to create the final dosage form.3

The strategic goal of formulation patents is to create product differentiation and enhance a drug’s clinical profile or commercial appeal.3 For example, a formulation patent might protect:

- An extended-release version of a pill that allows for convenient once-daily dosing instead of multiple times a day, improving patient compliance.4

- A specific coating that improves the drug’s stability, taste, or absorption profile.

- A novel delivery system, such as a transdermal patch, an inhaler, or a nanoparticle-based system that enhances bioavailability or targets the drug to specific tissues.4

These innovations, while not changing the core API, can provide significant therapeutic benefits and serve as powerful barriers to generic competition. Even if a generic manufacturer can produce the API after the composition of matter patent expires, they may be blocked from marketing a more convenient or effective version of the drug protected by a formulation patent.

Defending the Process: Manufacturing and Process Patents

Process patents, or methods of manufacture patents, protect the specific techniques used to produce a drug.3 Instead of claiming the final product, these patents claim the novel and non-obvious steps involved in its synthesis or purification.14

The strategic value of process patents is primarily defensive. They provide an additional layer of protection that can be particularly effective against generic manufacturing.3 A competitor may be able to legally synthesize the API after the composition of matter patent expires, but a process patent can prevent them from using the most efficient, highest-yield, or most cost-effective manufacturing method. This forces the competitor to invest in developing their own, potentially more expensive or less efficient, manufacturing process, thereby creating a significant cost barrier to market entry. In some jurisdictions, particularly developing countries, process patents have historically been a primary form of protection, allowing for variations in manufacturing while curbing the monopoly on the final product.16

The true defensive strength of a pharmaceutical patent portfolio emerges not from the individual power of any single patent type, but from their synergistic and overlapping nature. The various patents are strategically layered to create a cumulative defensive barrier that is far greater than the sum of its parts. A generic competitor attempting to enter the market does not face a single hurdle, but a legal and technical minefield.4

Consider the path of a challenger. They might first attempt to “design around” a specific formulation patent by developing a different extended-release mechanism. However, even if they succeed, they may find that the only economically viable way to synthesize the active ingredient infringes a process patent held by the innovator. If they then invest in developing a non-infringing synthesis route, they may discover that the resulting API naturally crystallizes into a form protected by a polymorph patent. All of this effort occurs under the shadow of the primary composition of matter patent, which remains the ultimate barrier until its expiration.

This deliberate layering transforms the strategic calculus for a potential competitor. The objective for the innovator is often not to win every potential court battle on the merits of each secondary patent, but to make the prospect of litigation so daunting, expensive, and complex that competitors are deterred from even attempting a challenge. The cumulative deterrent effect of the entire portfolio becomes the primary weapon, forcing competitors toward settlements that are highly favorable to the brand manufacturer.4 This is the foundational logic of the patent thicket and the essence of modern, sophisticated pharmaceutical patent strategy.

IV. Mastering the U.S. Regulatory-Patent Interface

In the United States, the world’s largest pharmaceutical market, patent strategy cannot be executed in a vacuum. It is inextricably linked with the complex regulatory framework overseen by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). The interplay between patent rights granted by the USPTO and marketing approval granted by the FDA creates a unique and highly strategic environment. Mastering this interface is paramount for maximizing the commercial lifespan of a pharmaceutical asset.

The Hatch-Waxman Act: A Dual-Edged Sword for Innovators and Generics

The Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984, commonly known as the Hatch-Waxman Act, is the foundational legislation governing the relationship between innovator (brand-name) and generic drugs in the U.S..3 It was a landmark compromise designed to achieve two competing goals: to streamline the approval of lower-cost generic drugs and to provide incentives for innovators to continue investing in R&D.18

For generics, the Act created the Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) pathway. This allows a generic manufacturer to gain FDA approval by demonstrating that its product is bioequivalent to the innovator’s drug, without having to repeat costly and time-consuming clinical trials.17

To enter this pathway, a generic applicant must make a certification for each patent listed by the innovator as covering the branded drug. The most aggressive and strategically significant of these is the Paragraph IV certification, in which the generic applicant declares that the innovator’s patent is invalid, unenforceable, or will not be infringed by the proposed generic product.20 The very act of filing an ANDA with a Paragraph IV certification is defined by statute as an “artificial act of patent infringement,” which allows patent litigation to commence immediately, long before the generic drug is actually sold.20

This triggers two powerful mechanisms:

- The 30-Month Stay: If the innovator files a patent infringement lawsuit against the generic applicant within 45 days of receiving the Paragraph IV notice, the FDA is automatically barred from granting final approval to the generic’s ANDA for up to 30 months.21 This “stay” provides the innovator with a critical window to litigate its patent rights without facing immediate market competition.

- The 180-Day Exclusivity: To incentivize these risky and expensive patent challenges, the Act grants a 180-day period of marketing exclusivity to the “first-to-file” generic applicant that successfully challenges a patent.3 During this six-month period, the FDA cannot approve any subsequent generic versions of the same drug, effectively creating a duopoly between the brand and the first generic. This exclusivity is the primary economic driver for generic patent challenges.20

The Orange Book: More Than a Listing, A Strategic Battlefield

The central nexus of the Hatch-Waxman framework is the FDA’s publication, Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations, colloquially known as the “Orange Book”.3 This public database serves as the official register linking FDA-approved drugs to the patents that the innovator claims cover them.23

When submitting a New Drug Application (NDA), an innovator company is required to identify and submit information on patents that claim the drug. However, not all patents are eligible for listing. The statute and FDA regulations specify that only patents claiming the drug substance (active ingredient), the drug product (formulation or composition), or an approved method of use can be listed.21 Critically, patents that claim manufacturing processes, packaging, metabolites, or intermediates are

not listable in the Orange Book.23

This distinction makes the act of listing a patent a key strategic decision. By listing a patent, the innovator forces any prospective generic applicant to address it with a certification, thereby bringing it into the Hatch-Waxman litigation framework and making it a potential basis for triggering a 30-month stay. The Orange Book is therefore not just a passive list; it is an active strategic tool used to construct the outer defenses of a patent fortress.

Clawing Back Time: Maximizing Patent Term Extension (PTE) and Regulatory Exclusivities

Recognizing that a significant portion of a patent’s 20-year term is consumed by the lengthy drug development and regulatory review process, the Hatch-Waxman Act also created mechanisms to restore some of this lost time, extending a product’s market protection beyond the original patent expiration date. These extensions are among the most valuable assets in an innovator’s portfolio.

Patent Term Extension (PTE): This provision allows for the extension of the term of one patent covering an FDA-approved product to compensate for time lost during regulatory review.3 The rules governing PTE are complex and strict:

- Eligibility: The patent must claim the approved product, a method of its use, or a method of its manufacture. The application for extension must be submitted within 60 days of the drug’s marketing approval, and the approval must be the first permitted commercial marketing or use of that product.26 Only one patent can be extended for any given regulatory review period.28

- Calculation: The length of the extension is calculated based on the time spent in clinical trials (the “testing period”) and the time the application was under review at the FDA (the “approval period”). However, only one-half of the testing period is credited.29

- Statutory Caps: The total extension period cannot exceed five years. Furthermore, the total remaining patent term after the extension is applied cannot exceed 14 years from the date of the drug’s approval.1

Regulatory Exclusivities: Separate from and in addition to patent protection, the FDA grants several types of statutory exclusivities that provide fixed periods of market protection. These exclusivities run in parallel with patents and can provide protection even if the underlying patents are challenged or expire.3 Key types include:

- New Chemical Entity (NCE) Exclusivity: A drug containing an active moiety that has never before been approved by the FDA is granted five years of market exclusivity from the date of its approval. During this period, the FDA cannot accept an ANDA from a generic competitor (unless it is filed with a Paragraph IV certification after year four).3

- New Clinical Investigation Exclusivity: Three years of exclusivity are granted for the approval of an application that contains reports of new clinical investigations (other than bioavailability studies) that were essential to the approval. This is often granted for new indications, new dosage forms, or other significant changes to a previously approved drug.3

- Orphan Drug Exclusivity (ODE): To incentivize the development of treatments for rare diseases (affecting fewer than 200,000 people in the U.S.), the FDA grants seven years of market exclusivity to a drug approved with an orphan designation.3

- Pediatric Exclusivity (PED): If a company conducts pediatric studies at the written request of the FDA, it is granted an additional six months of exclusivity. This six-month period is a powerful incentive as it is “tacked on” to all other existing patents and regulatory exclusivities for that drug, often translating into hundreds of millions of dollars in additional sales.3

The Biologics Frontier: Navigating the BPCIA and the “Patent Dance”

The Hatch-Waxman framework was designed for traditional, small-molecule chemical drugs. The rise of large-molecule biologics—complex proteins derived from living organisms—required a new legislative approach. This came in the form of the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA) of 2009, which created an abbreviated approval pathway for “biosimilars”.33

The BPCIA establishes its own distinct set of powerful regulatory exclusivities for the innovator’s reference product. A biosimilar application cannot be submitted to the FDA until four years after the reference product’s initial approval (data exclusivity), and the FDA cannot approve a biosimilar until 12 years have passed from the reference product’s first approval (market exclusivity).33 This 12-year period is one of the longest statutory exclusivities available and provides a substantial period of protection for innovative biologics.

The BPCIA also created a unique, highly structured process for resolving patent disputes, colloquially known as the “patent dance”.33 This is a complex, multi-step exchange of information between the biosimilar applicant and the reference product sponsor, designed to identify and narrow the patents that will be litigated before the biosimilar launches.36 The process involves the sharing of the confidential biosimilar application, lists of patents, and detailed statements on infringement and validity.37

Crucially, the Supreme Court has ruled that participation in the patent dance is optional for the biosimilar applicant.36 This creates a major strategic decision point: a biosimilar developer can choose to engage in the structured process to gain clarity on the patent landscape, or it can opt out, potentially leading to a more chaotic and immediate litigation scenario where the innovator can sue on any patent it believes might be relevant.37

The existence of regulatory exclusivities alongside patent protection creates a critical, independent safety net for innovators. While the validity of a patent can be challenged and potentially overturned in court or at the PTAB at any time, regulatory exclusivities, once granted by the FDA upon drug approval, are statutory protections that are not subject to the same types of validity challenges. This means that a company with a newly approved drug that qualifies for 5-year NCE exclusivity is guaranteed at least that period of protection from generic competition, even if its foundational patents are immediately invalidated in litigation. For an orphan drug, this guaranteed protection extends to seven years under ODE. This statutory backstop provides a baseline of predictable market exclusivity, which significantly de-risks the enormous investment required for drug development. Therefore, structuring a development program to qualify for these exclusivities is a primary strategic goal. The pediatric exclusivity is particularly valuable as a “tack-on” that extends all other forms of protection—both patent and regulatory—by an additional six months, often representing the most profitable period in a drug’s lifecycle. Understanding this dual-layer system of protection is fundamental to accurately forecasting a product’s commercial lifespan and maximizing its ROI.

V. Advanced Lifecycle Management: The Art of the Patent Thicket

In the modern pharmaceutical industry, the period of market exclusivity afforded by a drug’s initial patents is rarely sufficient to achieve the desired return on investment. As a result, companies have developed sophisticated strategies to manage a product’s entire commercial life, aiming to maximize its value from launch to post-patent expiration. This practice, known as Lifecycle Management (LCM), has evolved into a complex art form, often blurring the line between legitimate innovation and controversial market protection tactics.

From Lifecycle Management to “Evergreening”: A Strategic and Ethical Analysis

Lifecycle Management (LCM) is a holistic business strategy encompassing all activities designed to maximize a drug’s value throughout its commercial lifetime.38 It is a multi-pillar approach that integrates developmental, commercial, and regulatory/legal strategies.38 Developmental LCM focuses on enhancing a product’s clinical profile by expanding its use into new indications, developing new formulations (e.g., extended-release versions), or creating new delivery systems to improve patient compliance.11

However, the legal and regulatory component of LCM, which focuses on extending market exclusivity, has given rise to the controversial practice known as “evergreening.” This term refers to a range of strategies used by pharmaceutical companies to obtain secondary patents on minor modifications, improvements, or new applications of existing drugs, with the primary goal of extending their monopoly protection and delaying generic competition.15 These secondary patents may cover new dosage forms, different methods of administration, or combinations with other active ingredients.15

The debate around evergreening is highly polarized. Proponents and industry representatives argue that these practices are a legitimate and necessary part of ongoing innovation. They contend that so-called “evergreening” initiatives lead to tangible improvements in product quality, safety, and efficacy, such as by reducing side effects or improving dosing convenience, which directly benefit patients.15 Furthermore, they argue that protecting these incremental innovations is essential to recouping the billions of dollars invested in R&D and to funding the development of future breakthrough therapies.15

Critics, on the other hand, view evergreening as an abuse of the patent system that prioritizes profits over public health.44 They argue that it stifles fair competition by blocking the market entry of more affordable generic products, thereby keeping drug prices artificially high and increasing costs for patients and healthcare systems.15 A central critique is that this strategy diverts resources toward making trivial tweaks to existing blockbuster drugs rather than pursuing riskier, but potentially more impactful, research into truly novel medicines.15

Anatomy of a Patent Thicket: Layering Secondary Patents for Maximum Defense

The practical implementation of an evergreening strategy is the creation of a “patent thicket”—a dense, overlapping web of patents covering a single product.46 While the primary patent covers the core innovation (the active ingredient), the thicket is built from dozens or even hundreds of secondary patents targeting peripheral features like dosage forms, manufacturing methods, or new therapeutic uses.46

The strategic objective of a patent thicket is not necessarily to ensure that every single secondary patent is an impenetrable invention in its own right. Instead, the goal is to create a cumulative deterrent effect.4 A generic or biosimilar competitor seeking to enter the market must navigate a legal minefield. They do not have to invalidate or design around just one patent; they may have to confront dozens. The sheer volume of patents makes the prospect of litigation so daunting, time-consuming, and expensive that it can deter challenges altogether or force competitors into settlements that are highly favorable to the innovator company.4

Data reveals the prevalence of this post-approval patenting strategy. For top-selling drugs, an estimated 66% of all patent applications are filed after the drug has already received FDA approval, highlighting the intense focus on LCM.46 Furthermore, analysis shows that approximately 78% of new patents granted are for modifications to existing drugs, rather than for entirely new medicines, underscoring the industry’s strategic focus on defending existing revenue streams.46

Case Study in Focus: AbbVie’s HUMIRA® – Deconstructing a Multi-Billion Dollar Defensive Strategy

No case better illustrates the power and controversy of the patent thicket strategy than AbbVie’s defense of its blockbuster anti-inflammatory drug, HUMIRA® (adalimumab). AbbVie’s approach has become the definitive real-world example of how a meticulously constructed and aggressively defended patent fortress can extend a drug’s monopoly and generate tens of billions of dollars in revenue.

HUMIRA® was first approved by the FDA in 2002, and its primary patent on the active ingredient was set to expire in 2016.51 In a textbook execution of an LCM strategy, AbbVie constructed one of the most formidable patent thickets in industry history. The company filed over 247 patent applications in the United States, ultimately securing a portfolio of more than 130 granted patents covering various aspects of the drug.51 A staggering 89% of these patent applications were filed

after HUMIRA® was already on the market, with the explicit aim of delaying competition for a potential 39 years.52

This strategy was remarkably successful. When biosimilar competitors sought to enter the U.S. market, AbbVie initiated litigation, asserting dozens of its secondary patents in each case—in some instances, suing a single competitor with over 100 patents.53 The immense legal and financial pressure created by this thicket effectively delayed any biosimilar competition in the U.S. until 2023, nearly seven years after the primary patent expired and five years after biosimilars had already launched in Europe.51

The financial impact was enormous. The extended monopoly in the U.S. allowed HUMIRA® to become the world’s best-selling drug, generating revenue of $47.5 million per day just before biosimilar entry.46 This delay is estimated to have cost the U.S. healthcare system and taxpayers an excess of $14.4 billion, with some estimates putting the total wasted spending on HUMIRA® and two other drugs post-EU generic entry at $167 billion.46

AbbVie’s strategy was challenged in court on antitrust grounds, with plaintiffs arguing that the sheer numerosity of the patents constituted an illegal monopoly. However, in a landmark decision, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit affirmed the dismissal of the case. The court reasoned that as long as the patents were validly obtained through the proper USPTO process, accumulating a large number of them is not, by itself, a violation of antitrust law.51 This ruling set a major legal precedent, effectively validating the patent thicket strategy and signaling to the industry that such aggressive patenting, short of fraud or sham litigation, is a permissible competitive tactic.51

Designing Around: Counter-Strategies for Generic and Biosimilar Challengers

For generic and biosimilar companies, confronting a patent thicket requires a sophisticated counter-strategy focused on “designing around” the innovator’s IP fortress. This involves meticulously analyzing the innovator’s patent portfolio to identify potential weaknesses, gaps, or opportunities for non-infringing alternatives.57

The goal is to develop a product that is therapeutically equivalent to the branded drug but falls outside the specific scope of its patent claims. Common design-around strategies include:

- Developing Novel Formulations: If the innovator has patented an extended-release formulation, a challenger might develop a different controlled-release mechanism that achieves the same clinical effect through a different technical approach.4

- Identifying Alternative Polymorphs: A challenger may conduct extensive screening to discover a new crystalline form (polymorph) of the API that is not covered by the innovator’s patents but possesses the necessary stability and bioavailability for a viable drug product.4

- Creating Alternative Manufacturing Processes: If the most efficient synthesis route is protected by a process patent, a generic company must invest in developing a novel, non-infringing process to manufacture the API.16

Success in designing around requires a deep integration of scientific R&D with expert patent analysis. It is a high-risk, high-reward endeavor that necessitates a thorough Freedom-to-Operate (FTO) analysis from the earliest stages of development to ensure the chosen path is clear of infringement risks.

The HUMIRA® case study and the legal precedent it established reveal a critical reality of the modern pharmaceutical industry: for blockbuster drugs, patent strategy is inseparable from litigation strategy. The patent portfolio is no longer just a passive shield to protect an invention; it is a stockpile of ammunition for a war of attrition. AbbVie’s strategy demonstrated that the success of a patent thicket hinges less on the individual, unassailable strength of each secondary patent and more on the cumulative financial and legal burden imposed by the sheer volume of the portfolio. The cost of defending against a single patent lawsuit can run into the millions of dollars 59; the cost of defending against a hundred is prohibitive for all but the largest and most well-capitalized challengers. This dynamic transforms patent law from a tool to reward invention into a commercial weapon to control markets through strategic, resource-draining litigation. For any company, innovator or generic, understanding this shift is crucial to survival.

VI. The Global Chessboard: Comparative Patent Strategies for Key Markets

A comprehensive pharmaceutical patent strategy cannot be confined to a single country. The world’s major pharmaceutical markets—the United States, the European Union, China, and India—each possess distinct legal, regulatory, and economic landscapes. Navigating this fragmented global chessboard requires a nuanced understanding of each region’s unique rules and leveraging those differences to create a strategic advantage.

The European Union: Leveraging SPCs, the “8+2+1” Exclusivity Rule, and the Unified Patent Court (UPC)

The European Union represents a complex but highly valuable market, characterized by strong regulatory protections and a newly unified patent litigation system.

- Supplementary Protection Certificates (SPCs): The EU’s equivalent of the U.S. Patent Term Extension (PTE) is the Supplementary Protection Certificate (SPC). An SPC can extend the effective life of a patent for a medicinal product by up to five years to compensate for the time lost during the lengthy regulatory approval process.60 A further six-month pediatric extension is available, allowing for a maximum SPC term of 5.5 years.61 This mechanism is crucial for recouping R&D investments in Europe.63

- Data & Market Exclusivity: The EU offers one of the most robust regulatory data protection (RDP) periods in the world, known as the “8+2+1” formula.64 An innovator company receives eight years of data exclusivity, during which a generic or biosimilar applicant cannot reference the innovator’s preclinical and clinical trial data. This is followed by two years of market protection, during which a generic/biosimilar cannot be launched even if it has been approved. An additional one-year extension of market protection can be granted if the company obtains approval for a new therapeutic indication with significant clinical benefit during the first eight years.3 This provides a potential total of 11 years of market protection, independent of patent status.

- Unified Patent Court (UPC): Since its launch in 2023, the Unified Patent Court (UPC) has begun to reshape European patent litigation. The UPC provides a single forum for litigating European patents across all participating EU member states.65 This presents a powerful opportunity for innovators to obtain a single, pan-European injunction against an infringer. However, it also carries a significant risk: a competitor can seek to invalidate a patent in a single action across the entire UPC territory, a so-called “central revocation”.65 Early trends indicate that many pharmaceutical companies, wary of this risk for their high-value assets, have chosen to “opt out” their key European patents from the UPC’s jurisdiction, preferring to rely on the older system of national court litigation. In contrast, the medical device sector has been more active in using the new court.65

China: Capitalizing on the Patent Linkage System and a Pro-Enforcement Environment

China’s intellectual property system has undergone a dramatic transformation. Once viewed with skepticism, it has rapidly matured into a sophisticated and robust framework that is increasingly favorable to patent holders, including foreign entities.69 Today, China is a premier venue for patent enforcement, boasting high success rates for plaintiffs, efficient timelines, and a powerful new patent linkage system.70

- Patent Linkage System: Implemented in 2021, China’s patent linkage system closely mirrors the U.S. Hatch-Waxman Act.71 It establishes a platform for listing patents covering approved drugs. When a generic company files for marketing approval and challenges a listed patent (a “Type IV” declaration), the patent holder has 45 days to file a lawsuit or an administrative action.72 This triggers an automatic 9-month stay on the generic’s approval, providing a window for dispute resolution.73

- Market Exclusivity for Generics: To incentivize challenges, the system grants a 12-month period of market exclusivity to the first generic applicant that successfully challenges a patent and obtains marketing approval.74

- Patent Term Extension (PTE): China has also introduced a PTE system to compensate for regulatory delays. The framework allows for up to five years of patent term extension, with the total effective patent term post-approval capped at 14 years, aligning its policies with those of the U.S. and EU.75

- Pro-Enforcement Judiciary: China has established specialized IP courts that handle patent disputes with technical expertise.70 Litigation is notably efficient, with many cases resolved within 12 months. Foreign plaintiffs have achieved high success rates, and courts have shown a willingness to grant significant damages awards, transforming China from a market of high infringement risk to a key jurisdiction for strategic patent enforcement.70

India: Overcoming Section 3(d) and Managing the Risk of Compulsory Licensing

India’s patent system is unique, shaped by a strong national policy aimed at balancing innovation incentives with the imperative of ensuring access to affordable medicines for its large population.77 This has created a challenging but navigable environment for innovator companies.

- Section 3(d): The most distinctive and controversial feature of Indian patent law is Section 3(d) of the Patents Act, 1970. This provision is explicitly designed to prevent “evergreening”.78 It states that “the mere discovery of a new form of a known substance which does not result in the enhancement of the known efficacy of that substance” is not patentable.77 This creates a high bar for obtaining secondary patents on new salts, polymorphs, or other variations of existing drugs. The landmark Supreme Court of India case involving Novartis’s cancer drug Gleevec firmly established that “efficacy” must be interpreted as “therapeutic efficacy.” This means that improvements in properties like bioavailability or stability are insufficient to overcome a Section 3(d) objection unless they translate into a demonstrable improvement in the drug’s clinical effect.78

- Compulsory Licensing: India’s patent law also includes broad provisions for compulsory licensing, which are among the most expansive in the world.81 After three years from a patent’s grant, any interested party can apply for a compulsory license on several grounds, including if the patented invention is not available to the public at a reasonably affordable price, if the public’s reasonable requirements have not been met, or if the invention is not “worked” in the territory of India.83 To date, only one such license has been granted for a pharmaceutical product—to Natco Pharma for a generic version of Bayer’s cancer drug Nexavar in 2012—but the provision remains a significant strategic consideration and a point of leverage for the Indian government and local manufacturers.83

Global Filing Strategy: The Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) and Strategic Prioritization

For companies seeking protection in multiple countries, the Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) is an indispensable procedural tool.86 Administered by the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), the PCT system, with over 150 member states, streamlines the process of initiating patent protection globally.87

An applicant can file a single “international” patent application in one language with one receiving office.89 This application undergoes a unified international search, which provides an early indication of the invention’s patentability.86 It is crucial to understand that the PCT does not grant a “world patent”; no such thing exists.88 The applicant must still “enter the national phase” and prosecute the application separately in each individual country or region where they seek protection.87

The primary strategic value of the PCT is the time it buys. It provides a period of up to 30 or 31 months from the initial priority filing date before the applicant must incur the significant expenses of entering the national phase (including translation fees, local attorney fees, and official filing fees) in multiple jurisdictions.86 This extended period allows a company to gather more clinical data, assess the commercial potential of a drug candidate, and make more informed decisions about which markets are worth the investment, thereby optimizing the allocation of its IP budget.86

The stark differences in patent laws, regulatory frameworks, and enforcement environments across major global markets create not just challenges, but also significant strategic opportunities. A sophisticated global strategy involves a form of “geographic arbitrage,” where actions and outcomes in one region are deliberately used to influence strategy and finance operations in another.

For example, a generic company facing a formidable patent thicket in the United States can employ a “European Launch First” strategy.20 Due to differing patent landscapes and the fixed term of SPCs, it may be possible to launch a generic or biosimilar product in the EU years before it is possible in the U.S. The revenue generated from these early European sales can then be used to fund the expensive and protracted Paragraph IV litigation required to challenge the innovator’s patents in the lucrative U.S. market.20 Furthermore, a successful patent invalidation achieved in a European Patent Office (EPO) opposition proceeding, while not legally binding in the U.S., can serve as powerful persuasive evidence in U.S. court proceedings, increasing pressure on the innovator to settle. This transforms global patent prosecution and litigation into an interconnected game of chess, where a move on one part of the board is calculated for its ripple effects on another. A truly effective global strategy is not a series of isolated national filings, but a coordinated, multi-year campaign that sequences legal challenges, market launches, and revenue generation across jurisdictions to maximize global commercial success.

| Feature | United States | European Union | China | India |

| Core Patent Term | 20 years from filing | 20 years from filing | 20 years from filing | 20 years from filing |

| Patent Term Extension/Restoration | Patent Term Extension (PTE) up to 5 years; total term post-approval capped at 14 years 26 | Supplementary Protection Certificate (SPC) up to 5 years (5.5 with pediatric extension) 60 | Patent Term Compensation (PTC) up to 5 years; total term post-approval capped at 14 years 75 | No provision for patent term extension |

| Data Exclusivity (New Entity) | 5 years for New Chemical Entity (NCE); 12 years market exclusivity for biologics 3 | 8 years data exclusivity + 2 years market protection (“8+2”) 3 | Not explicitly defined in the same manner; relies on other protections | No formal data exclusivity; relies on other mechanisms 81 |

| Market Protection/Exclusivity | 12 years for biologics; 7 years for Orphan Drugs; 180-day for first generic 3 | 10 years total (8+2); 10 years for Orphan Drugs; 1-year extension for new indication possible 3 | 12-month market exclusivity for first successful generic challenger 74 | No explicit market protection separate from patent term |

| Patent Linkage System | Yes (Hatch-Waxman Act); 30-month stay of generic approval upon litigation 3 | No formal linkage system; relies on patent enforcement through national courts/UPC | Yes (Implemented 2021); 9-month stay of generic approval upon litigation 71 | No formal linkage system |

| Key Legal Hurdles for Innovators | Aggressive Paragraph IV challenges; Inter Partes Review (IPR) at PTAB | Central revocation risk at Unified Patent Court (UPC); stringent SPC requirements | Rapid litigation timelines; evidence collection challenges (no discovery) 70 | Section 3(d) “enhanced efficacy” requirement; risk of compulsory licensing 79 |

| Key Litigation Forum(s) | U.S. District Courts (esp. DE, NJ); Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) | National Courts; Unified Patent Court (UPC); European Patent Office (EPO) for opposition | Specialized IP Courts (e.g., Beijing); CNIPA for administrative actions | High Courts; Intellectual Property Appellate Board (IPAB, now dissolved and functions moved to High Courts) |

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Global IP & Regulatory Frameworks

VII. Litigation as Strategy: Defending the Fortress and Challenging Rivals

In the high-stakes pharmaceutical sector, patent litigation is not merely a last resort for resolving disputes; it is a core component of commercial strategy. For innovator companies, it is the primary mechanism for defending the patent fortress and preserving revenue streams. For generic and biosimilar challengers, it is the essential tool for clearing a path to market entry. Understanding the rules, venues, and strategic calculus of litigation is therefore indispensable.

The Paragraph IV Gauntlet: An Innovator’s Playbook for Hatch-Waxman Litigation

The receipt of a Paragraph IV notice letter from a generic applicant initiates a high-pressure, time-sensitive sequence of events for an innovator company. This notice signals a direct challenge to the innovator’s patent rights and triggers the start of the “Hatch-Waxman gauntlet”.92

The first and most critical strategic decision is whether to file a patent infringement lawsuit. This decision must be made within a strict 45-day window following receipt of the notice.17 Filing suit within this timeframe is the only way to trigger the powerful 30-month stay of FDA approval for the generic’s ANDA.21 This stay is a crucial defensive weapon, providing a substantial period to litigate the patent’s validity and infringement without facing immediate generic competition.

The choice of where to file the lawsuit is another key strategic consideration. The vast majority of Hatch-Waxman cases are filed in the U.S. District Courts for the District of Delaware and the District of New Jersey, largely because many pharmaceutical companies are incorporated in Delaware or headquartered in New Jersey.94 These jurisdictions have judges with deep experience in complex patent law and the specific procedural nuances of ANDA litigation, making them predictable and preferred venues.94

Once initiated, the litigation proceeds through standard phases, including discovery (exchange of evidence), a Markman hearing (where the court construes the meaning of the patent claims), summary judgment motions, a bench trial (decided by a judge, not a jury), and potential appeals to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit.92 Throughout this process, the innovator’s legal team works to prove that the generic’s proposed product will infringe the patent and that the patent is valid, while the generic’s team argues the opposite.

The Biosimilar Battle: Offensive and Defensive Strategies in BPCIA Litigation

Patent litigation for biologics and their biosimilar competitors operates under a different framework, the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA). A central strategic element of BPCIA litigation is the “patent dance,” the complex, optional information exchange process.37

For a biosimilar developer, the decision to engage in the dance or to opt out is a critical one. Participating provides a structured pathway to identify and narrow the patents in dispute, offering a degree of predictability. Opting out can lead to a more immediate and potentially broader litigation, as the innovator (Reference Product Sponsor, or RPS) is then free to sue on any patent it reasonably believes could be infringed.36

BPCIA litigation is often structured in two waves. The “first wave” occurs after the patent dance (or the decision to forgo it) and focuses on an initial set of patents. The “second wave” can be triggered when the biosimilar applicant provides a 180-day notice of commercial marketing, at which point the RPS can seek a preliminary injunction to block the biosimilar’s launch and litigate any remaining patents.33

Key strategies in these battles include:

- For Biosimilar Developers (Defense): The primary defenses are arguing for patent invalidity (e.g., the invention was obvious or not novel) and non-infringement (e.g., the biosimilar’s manufacturing process or final structure falls outside the scope of the patent’s claims).33

- For Innovators (Offense): The most powerful offensive tool is the motion for a preliminary injunction, which asks the court to block the biosimilar from launching while the litigation is ongoing. This is a critical step to prevent irreversible market share and price erosion.97

The PTAB Arena: Using and Defending Against Inter Partes Review (IPR)

A parallel and increasingly important venue for patent challenges is the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB), an administrative tribunal within the USPTO. The America Invents Act of 2011 created the Inter Partes Review (IPR) process, which provides a faster and more cost-effective mechanism for challenging the validity of an issued patent compared to traditional district court litigation.98

Generic and biosimilar companies strategically use IPRs to attack patents they believe are weak or were improperly granted.100 An IPR proceeding is focused solely on validity based on prior art patents and printed publications.99 The process has two key features that make it attractive to challengers:

- Different Legal Standard: Unlike in district court, where a patent is presumed valid and must be proven invalid by “clear and convincing evidence,” there is no presumption of validity at the PTAB. The standard of proof is lower: a “preponderance of the evidence”.101

- Speed and Cost: An IPR must be completed within 18 months from the petition filing, a significantly faster timeline than the 30-plus months a typical district court case can take. The costs are also substantially lower.98

Filing an IPR can be a powerful negotiation tool. The threat of a faster, lower-cost validity challenge at the PTAB can pressure an innovator to settle the parallel district court litigation on more favorable terms for the challenger.100

Data-Driven Decisions: Analyzing Litigation Success Rates and Trends

Analyzing historical litigation outcomes provides critical data for strategic decision-making.

- Hatch-Waxman Litigation: Statistics from 2024 show a clear advantage for innovators in resolved court cases. Innovator companies prevailed on the issues 20% of the time, whereas generic companies prevailed in only 2% of cases (these figures exclude the large number of cases that are settled).94 At trial, courts found infringement more frequently than non-infringement, and upheld patent validity more often than not.94 However, this data must be contextualized. Some analyses suggest that when generic companies challenge

secondary patents (the kind used in patent thickets) and see the litigation through to a final decision, they win most of the time.102 The apparent high success rate for innovators may reflect the fact that generics often settle cases where they perceive a high likelihood of winning, rather than litigating to the end.95 - BPCIA Litigation: A key trend in biosimilar litigation is the impact of complexity on outcomes. To date, every case that has proceeded to a final court resolution on the merits (a trial verdict or summary judgment) has involved five or fewer patents. In contrast, no case that initially asserted more than five patents has reached such a resolution; they have all been settled or resolved on other grounds.103 This strongly indicates that as the complexity and cost of the litigation increase (i.e., as the patent thicket gets denser), the likelihood of a settlement also increases dramatically.

- IPR Proceedings: The data from the PTAB reveals a different picture. While the institution rate for IPR petitions against bio/pharma patents is lower than in other technology sectors (around 61-62%) 98, the patents that are accepted for review face a high risk of being invalidated. One analysis found that 65.6% of instituted bio/pharma claims that reached a final decision were cancelled.104 More recent data from FY24 shows that across all technologies, of the patents that reached a final written decision, approximately 68% were found to have all claims unpatentable.105 This demonstrates that the PTAB is a formidable venue for patent challengers.

The existence of multiple, distinct legal venues for patent disputes—each with its own procedures, timelines, and legal standards—creates a crucial strategic opportunity known as “forum shopping.” A patent challenger is not limited to a single path; they can choose the arena that best suits their specific case and objectives. For instance, a generic company believing an innovator’s patent is invalid due to prior art publications is faced with a strategic choice. They can raise this defense in a district court Hatch-Waxman case, where the patent is presumed valid and the burden of proof is high (“clear and convincing evidence”).101 Alternatively, they can file an IPR at the PTAB, where there is no presumption of validity, the burden of proof is lower (“preponderance of the evidence”), and the timeline is much faster.98 Given the high rate of claim cancellation for instituted IPRs, a challenger with a strong prior art case is heavily incentivized to use the PTAB.104 This forces the innovator into a difficult position, often having to defend the same patent in a costly district court case and a specialized PTAB proceeding simultaneously, under different and less favorable rules. This multi-front legal battle significantly increases the innovator’s costs and risks, making an early settlement a more attractive outcome.

| Feature | Hatch-Waxman (District Court) | BPCIA (District Court) | Inter Partes Review (PTAB) |

| Triggering Event | Filing of an ANDA with a Paragraph IV certification 17 | Filing of a biosimilar application (aBLA); can be initiated with or without the “patent dance” 36 | Petition filed by a third party challenging an issued patent 99 |

| Key Parties | NDA Holder (Innovator) vs. ANDA Filer (Generic) | Reference Product Sponsor (Innovator) vs. aBLA Filer (Biosimilar) | Petitioner (Challenger) vs. Patent Owner |

| Typical Timeline | 30-month stay period; litigation can take 2.5+ years 21 | Multi-wave litigation; can last several years post-aBLA submission 33 | 18 months from petition to final written decision 98 |

| Presumption of Validity | Yes, patent is presumed valid | Yes, patent is presumed valid | No presumption of validity 101 |

| Standard of Proof for Invalidity | Clear and Convincing Evidence | Clear and Convincing Evidence | Preponderance of the Evidence 98 |

| Strategic Objective for Challenger | Invalidate/prove non-infringement to gain market entry and potential 180-day exclusivity 20 | Invalidate/prove non-infringement to clear path for launch after 12-year exclusivity expires 96 | Invalidate patent claims quickly and cost-effectively; create leverage for settlement in parallel court case 100 |

| Strategic Objective for Patent Holder | Obtain finding of infringement/validity to trigger 30-month stay and block generic entry 21 | Obtain preliminary injunction to block biosimilar launch; defend patents to extend monopoly 33 | Defend patent validity and prevent institution of IPR; if instituted, defend claims on the merits |

| Key Statistical Outcome/Trend | Innovators have a high success rate in decided cases (20% vs 2% for generics in 2024), but most cases settle 94 | Cases with >5 patents asserted tend to settle before a final court decision on the merits 103 | Lower institution rate for pharma patents, but high rate of claim cancellation once instituted 104 |

Table 2: Strategic Patent Litigation Pathways: A Comparative Overview

VIII. Patent Analytics as a Commercial Weapon: Driving Business Intelligence

Historically, patent searching was often viewed through a narrow, defensive lens—a cumbersome legal check to be performed late in the development cycle to avoid infringement.1 This perspective is now dangerously obsolete. In the modern biopharmaceutical landscape, the strategic paradigm has shifted. Patent data is no longer just a legal record; it is a vast and dynamic repository of technical, commercial, and strategic intelligence. Organizations that master the art of patent analytics can transform this data from a defensive shield into a powerful offensive weapon, driving competitive intelligence, de-risking R&D, and identifying new commercial opportunities.

Beyond Legal Defense: Using Patent Data for Competitive Intelligence (CI)

The systematic collection and analysis of competitor patent filings is a cornerstone of effective competitive intelligence (CI) in the pharmaceutical industry.106 Patent applications, which typically become public 18 months after their initial filing, provide an invaluable early warning system, offering a window into a competitor’s R&D pipeline years before a product is mentioned in a press release or enters clinical trials.108

By monitoring these filings, a company can gain unprecedented insights into:

- R&D Directions: Identify the specific therapeutic targets, mechanisms of action, and technological modalities (e.g., small molecules vs. biologics) that competitors are investing in.108

- Emerging Threats: Detect potential new competitive products long before they appear on clinical trial registries, allowing for proactive adjustments to one’s own portfolio and market strategy.108

- Strategic Priorities: Analyze the breadth and language of patent claims to understand the core innovations a competitor seeks to protect. For example, a flurry of formulation patents may signal a focus on lifecycle management for a key product.108

- Market Expansion: Track the jurisdictions where competitors are filing patents to predict their future geographic expansion plans.110

An organization that only conducts a “freedom to operate” search at the eleventh hour is playing defense, reacting to a landscape already shaped by others. In contrast, a company that integrates continuous patent monitoring into its CI function is playing offense, anticipating market shifts and making data-driven strategic decisions.1

Freedom-to-Operate (FTO) Analysis: De-Risking R&D and Commercial Launch

A Freedom-to-Operate (FTO) analysis is a targeted investigation to determine whether a proposed product, technology, or manufacturing process may infringe on the valid, in-force patent rights of a third party.112 It is a critical risk mitigation tool that should be conducted at key stages of the development lifecycle.

It is essential to distinguish FTO from patentability. As one expert analogy puts it: “Patentability is about securing a deed to a new piece of land you’ve discovered… Freedom to Operate, on the other hand, is about surveying the entire route to your new land”.115 A company can successfully obtain a patent on a new extended-release formulation of a drug, only to find it cannot commercialize that product because another company still holds a valid patent on the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) itself.115

The ROI of a thorough FTO analysis is immense. Given that bringing a new drug to market can cost billions of dollars, an FTO analysis helps to avoid the catastrophic scenario of investing heavily in a product only to be blocked from launching it by an existing patent. Furthermore, conducting a diligent FTO analysis and obtaining a legal opinion can serve as crucial evidence to defend against a charge of “willful infringement” in the United States. A finding of willfulness can expose a company to enhanced damages of up to three times the assessed amount, making FTO a vital tool for mitigating potentially devastating financial liability.115 The process is systematic, typically involving four key phases: scoping (defining the product and markets), searching (identifying relevant patents), analysis (evaluating infringement risk), and reporting (delivering actionable conclusions).115

Patent Landscaping to Identify “White Space” Opportunities and M&A Targets

While FTO analysis is the “microscope,” providing a detailed, narrowly focused view on infringement risk, patent landscaping is the “telescope,” offering a broad, panoramic view of the competitive and technological universe.115 A patent landscape analysis involves mapping the patent activity across an entire therapeutic area, technology platform, or competitive set.

This broad analysis can reveal critical strategic opportunities:

- “White Space” Identification: By visualizing the density of patent filings related to different biological targets or technological approaches, a landscape analysis can identify “white spaces”—areas with significant scientific and commercial potential but limited patent activity.109 These represent fertile ground for innovation with a lower risk of encountering a crowded and competitive IP environment.

- M&A and Licensing Targeting: Landscaping can identify smaller biotech companies or academic institutions that have developed strong, foundational patent positions in niche but valuable areas. These entities can become prime targets for mergers and acquisitions (M&A), strategic partnerships, or in-licensing deals that allow a larger company to quickly acquire new technology and bolster its pipeline.108

- Tracking Technology Trends: Analyzing the volume and type of patent filings over time can reveal major technological shifts, such as a move from small molecules to biologics or the rise of new delivery platforms, allowing a company to align its R&D strategy with emerging trends.108

Integrating IP Intelligence into Commercial Forecasting and ROI Models

Ultimately, the value of patent analytics lies in its integration into core business development and financial planning processes. A strong and well-managed patent portfolio is a critical corporate asset that directly impacts valuation and the ability to secure funding. For startups and early-stage biotechs, a robust IP portfolio is a magnet for venture capital and other forms of investment, providing tangible proof of protected innovation and a clear path to market exclusivity.6

Advanced business intelligence platforms, such as DrugPatentWatch, have become indispensable tools in this process. They move beyond simple patent databases by integrating IP data with a wealth of other critical information, including FDA regulatory data (Orange Book listings, exclusivities), litigation records from district courts and the PTAB, clinical trial information, and historical sales data.1 This integrated approach allows for more sophisticated and accurate commercial forecasting. By combining patent expiration dates with regulatory exclusivity timelines and the status of ongoing patent challenges, analysts can develop more precise models for predicting a drug’s “loss of exclusivity” (LOE) date—the point at which generic competition will begin and revenues will sharply decline. This capability is fundamental to accurate revenue forecasting, portfolio management, and strategic M&A valuation.

A particularly powerful, yet often underutilized, aspect of patent analytics is the strategic use of “patent pending” data. The fact that most patent applications become public 18 months after their priority filing date is not a limitation but a strategic feature of the global patent system.108 This predictable publication timeline provides a “crystal ball” into the R&D pipelines of competitors.122 While a patent-pending application does not grant any enforceable rights, it is a rich source of forward-looking intelligence.117 It reveals, with technical specificity, the inventions that a competitor has deemed valuable enough to protect, signaling their research direction, the targets they are pursuing, and the technologies they are developing. By systematically monitoring these 18-month publications, a company can effectively map out a competitor’s future product pipeline years before that competitor issues a press release or registers a Phase 1 clinical trial. This transforms patent data from a historical record of granted rights into a predictive intelligence tool. A company might observe a rival heavily patenting a new mechanism of action, providing the foresight to either pivot its own R&D to a less crowded “white space” or to double down and prepare for direct competition. This is a strategic decision made years earlier than would be possible by relying solely on traditional sources of competitive intelligence, providing a profound and sustainable competitive advantage.

IX. The Future of Pharma IP: Navigating Emerging Technological and Legal Frontiers

The pharmaceutical industry is on the cusp of a technological revolution. Breakthroughs in artificial intelligence, cell and gene therapy, and digital therapeutics are poised to redefine drug discovery and patient care. However, these new frontiers present profound challenges to the traditional intellectual property frameworks that have governed the industry for decades. A forward-looking patent strategy must not only master the current landscape but also anticipate and adapt to these emerging legal and technological shifts.

Patenting the Unseen: AI-Driven Drug Discovery and the Question of Inventorship

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) is accelerating nearly every phase of the drug discovery process, from target identification to lead optimization.123 AI platforms can analyze vast biological and chemical datasets to identify novel drug candidates with unprecedented speed and efficiency.125 However, this technological leap has created a fundamental conflict with a cornerstone of patent law: the requirement of human inventorship.

- The Inventorship Hurdle: U.S. patent law, and indeed the law in most jurisdictions worldwide, unequivocally states that an inventor must be a “natural person”.127 An AI system cannot be named as an inventor on a patent application. This principle was decisively affirmed in the landmark case of

Thaler v. Vidal, where the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit rejected an attempt to list the AI system DABUS as an inventor.127 - The “Significant Contribution” Standard: In response to the growing role of AI, the USPTO issued guidance in February 2024 clarifying its position on AI-assisted inventions.123 The guidance states that while the use of an AI tool does not preclude patentability, at least one human must have made a “significant contribution” to the conception of the invention. To determine what constitutes a “significant contribution,” the USPTO directs examiners to apply the

Pannu factors, a legal test traditionally used to determine joint inventorship.123 This means a human inventor must do more than simply recognize and appreciate the output of an AI system; they must have contributed significantly to the conception of the invention, for example by designing the AI model for a specific problem, skillfully curating the input data, or making critical selections and modifications to the AI’s output.128 - The Obviousness Challenge: As AI tools become more sophisticated and widely accessible, the legal standard for non-obviousness is likely to evolve. An invention that would have been considered a breakthrough a decade ago might be deemed “obvious to a person skilled in the art” if it can now be routinely generated by a standard AI platform. This will raise the bar for patentability, requiring a greater degree of human ingenuity to secure protection.127

The immediate strategic imperative for companies leveraging AI in R&D is the implementation of meticulous record-keeping. It is crucial to document every step of the inventive process, detailing the human contributions in designing AI prompts, training models, selecting data, and conducting the wet-lab experiments that validate or refine AI-generated hypotheses.127

The New Wave: IP Challenges in Cell & Gene Therapies and Digital Therapeutics

Beyond AI, other disruptive technologies are creating their own unique IP challenges that demand novel strategic approaches.

- Cell & Gene Therapies: This rapidly advancing field, which involves modifying a patient’s cells or genes to treat disease, presents a complex IP landscape. U.S. Supreme Court precedent has placed limits on the patentability of naturally occurring biological material, such as isolated human genes, creating challenges for protecting the core components of some therapies.130 As a result, IP protection often focuses on other aspects of the technology, such as:

- Vectors and Delivery Systems: Patenting the viral or non-viral vectors used to deliver the genetic material into cells.

- Genetically Modified Constructs: Protecting the specific engineered genetic constructs, such as the chimeric antigen receptors (CARs) used in CAR-T cell therapy.

- Manufacturing Processes: The complex, multi-step processes for manufacturing these therapies are often protected as valuable trade secrets.132