The High-Stakes Arena of Pharmaceutical Intellectual Property

The intersection of pharmaceutical science and patent law represents one of the most complex, high-stakes, and strategically intricate battlegrounds in modern commerce. At its core is a fundamental tension: the societal need for life-saving innovation, which requires massive private investment, and the equally pressing need for affordable access to medicine. This tension is managed through a delicate and often contentious system of intellectual property (IP) rights, primarily patents and regulatory exclusivities. Understanding the architecture of this system is the first step in mastering the art of challenging it. It is a world where legal doctrines are shaped by scientific data, and business strategies are dictated by the ticking clock of a patent’s life.

The Foundation of Exclusivity: The Patent Bargain and the 20-Year Illusion

The modern pharmaceutical industry is built upon a foundational legal and economic principle known as the “patent bargain.” This is a quid pro quo in which a government grants an inventor a temporary monopoly—the exclusive right to make, use, and sell an invention—in exchange for the inventor’s complete public disclosure of that invention.1 This system is designed to solve a critical economic problem: the staggering cost and risk of pharmaceutical research and development (R&D). Bringing a new drug to market is an arduous journey that can span 10 to 15 years and consume capital ranging from an estimated $300 million to over $2.6 billion.4 Without the promise of a protected period of market exclusivity, few entities would undertake such a perilous investment, knowing that competitors could simply reverse-engineer the final product and sell it at a fraction of the cost, thereby preventing the innovator from ever recouping their initial outlay.2 Patents provide this essential shield, creating the temporary monopoly needed to recover R&D costs, fund future innovation, and finance the enormous commercialization apparatus required to bring a drug to market.1

However, the statutory 20-year patent term, a global standard established for all World Trade Organization (WTO) member nations under the TRIPS agreement, creates what is often called the “20-year illusion”.4 The patent clock begins ticking from the date the application is filed, not from the date the drug is approved for sale.4 Pharmaceutical companies are strategically compelled to file for patent protection very early in the development process, often as soon as a promising molecule is discovered, to secure a priority date and attract the necessary investment capital.7 The subsequent journey through extensive preclinical research, multi-phase clinical trials, and rigorous regulatory review by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) consumes a substantial portion of this 20-year term—frequently 10 to 15 years.4 The result is that the “effective patent life”—the actual period during which a drug enjoys monopoly sales on the market—is significantly shorter, typically averaging only 7 to 10 years from the date of market launch.4

This fundamental misalignment between the start of the patent term and the start of the revenue-generating period is the single most important strategic driver in the pharmaceutical industry. It creates a profound and inescapable tension that dictates nearly all subsequent IP and commercial behavior. The immense pressure to maximize revenue within this compressed timeframe directly incentivizes two key strategies that define the industry: aggressive pricing at launch to recoup massive R&D investments as quickly as possible, and a relentless, systematic search for any and all legal and regulatory means to extend the period of market exclusivity.1 This structural “time crunch” is the very genesis of the entire field of pharmaceutical “lifecycle management.” It explains the strategic necessity of building complex patent portfolios, the development of so-called “evergreening” tactics, the meticulous pursuit of every available regulatory exclusivity, and the fierce, high-stakes litigation that inevitably ensues when these layers of protection are challenged. The art of both challenging and defending drug patents is a direct consequence of this foundational conflict between the legal term of the patent and the practical timeline of drug development.

To supplement the patent system, a parallel framework of regulatory exclusivities exists, granted by the FDA not for invention, but for achieving specific regulatory milestones.1 These statutory grants of market protection run independently of patents and can provide a critical additional shield for innovators.6 Key U.S. regulatory exclusivities are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1: U.S. Patent Protection vs. FDA Regulatory Exclusivity

| Attribute | Patents | Regulatory Exclusivity |

| Granting Body | U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) | Food and Drug Administration (FDA) |

| Basis for Grant | Meeting statutory requirements of novelty, non-obviousness, and utility 14 | Meeting specific statutory criteria (e.g., new chemical entity, orphan disease) 4 |

| Scope of Protection | Right to exclude others from making, using, or selling the claimed invention 9 | Right to prevent FDA from approving a competitor’s application relying on innovator’s data 1 |

| Standard Duration | 20 years from filing date 4 | Varies by type: 5 years (NCE), 7 years (Orphan), 12 years (Biologic), 180 days (First Generic) 4 |

| Potential for Extension | Patent Term Extension (PTE), Patent Term Adjustment (PTA) 4 | Pediatric Exclusivity (adds 6 months to existing patents and exclusivities) 4 |

While the 20-year patent term is a global standard, the mechanisms for extending market life vary significantly across key jurisdictions. The European Union utilizes Supplementary Protection Certificates (SPCs) to compensate for regulatory delays, Japan and China have their own forms of Patent Term Extension (PTE/PTR), and India employs stringent patentability criteria to prioritize affordable access to medicines over extended exclusivity.4 This global patchwork requires a sophisticated, market-by-market approach to both protecting and challenging pharmaceutical IP.

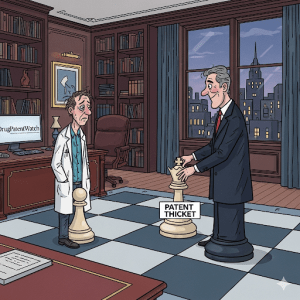

The Innovator’s Fortress: Anatomy of a “Patent Thicket”

An innovator company rarely relies on a single patent to protect a blockbuster drug. Instead, it constructs a formidable defensive fortress known as a “patent thicket”—a dense, overlapping web of numerous patents covering a single product.1 The “crown jewel” of this portfolio is the composition-of-matter patent, which claims the new molecular entity (NME) itself.6 This patent provides the broadest and most robust protection and is the most difficult to challenge. However, it is only the beginning of the defensive strategy.

Surrounding this core patent, innovators strategically file a multitude of secondary patents that claim every conceivable aspect of the drug’s development, formulation, manufacturing, and use.4 This multi-layered defense is designed to make it prohibitively difficult, expensive, and risky for a generic competitor to enter the market.1 Common types of secondary patents that form the walls of this fortress include:

- Formulation Patents: These protect the specific “recipe” of the final drug product, such as extended-release tablets that allow for once-daily dosing, novel coatings that improve stability, or nanoparticle delivery systems that enhance bioavailability.4 These patents are valuable because they can offer genuine patient benefits while creating a new 20-year patent term that extends well beyond the expiration of the original composition-of-matter patent.

- Method-of-Use Patents: These patents protect a new therapeutic use for a known drug, a practice known as drug repurposing.4 For example, a company might discover that a drug originally approved for hypertension is also effective for treating migraines and secure a new patent for that specific use, breathing new commercial life into an older compound.11

- Process Patents: These cover novel and non-obvious methods of manufacturing or purifying the drug.1 While a generic company can try to develop an alternative, non-infringing manufacturing process, this adds another layer of complexity and cost to their development.

- Polymorph and Chiral Switch Patents: These are highly technical patents that claim specific variations of the drug molecule itself. Polymorph patents cover different crystalline structures of the active ingredient, which can affect properties like solubility and stability.1 Chiral switch patents cover a single, therapeutically active enantiomer (a mirror-image version of a molecule) of a drug that was previously sold as a racemic mixture of both enantiomers.11

The strategic value of a patent thicket lies not in the individual, unassailable strength of each secondary patent but in its cumulative effect of creating economic and legal friction. Many of these secondary patents are inherently weaker and more vulnerable to invalidity challenges than the core composition-of-matter patent. However, a generic challenger cannot simply ignore them. Each patent in the thicket represents a potential lawsuit, forcing the challenger to engage in a costly and time-consuming war of attrition.1 The innovator’s strategy is to make the aggregate cost, time, and risk of litigating the entire portfolio so daunting that it either deters generic entry altogether or forces the challenger into a settlement that preserves a portion of the brand’s market exclusivity. This dynamic transforms the challenge from a quest for a single “silver bullet” invalidation into a complex exercise in patent triage. The art of the challenge becomes identifying the weakest links in the thicket—often the secondary patents on formulations or methods of use—and targeting them first. A successful early victory on a more vulnerable patent can create the necessary leverage to negotiate a favorable resolution for the entire portfolio, effectively finding a chink in the fortress’s armor rather than attempting to breach the main gate.

The Hatch-Waxman Compact: Engineering Patent Litigation

The modern framework for challenging drug patents in the United States was deliberately constructed by the Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984, universally known as the Hatch-Waxman Act.22 This landmark legislation fundamentally re-engineered the pharmaceutical market by creating a sophisticated legal and regulatory compact designed to balance the competing interests of innovator and generic drug companies.22 Before 1984, there was no streamlined pathway for generic drug approval, and generic competition was rare; today, generic drugs account for over 90% of all prescriptions filled in the U.S., a direct result of the Act’s architecture.22

The Act established several key mechanisms that now define the patent challenge landscape:

- The Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) Pathway: This was the Act’s most significant gift to the generic industry. It allowed generic manufacturers to gain FDA approval by simply demonstrating that their product was bioequivalent to the innovator’s drug, permitting them to rely on the brand company’s extensive and costly safety and efficacy data.6 This dramatically lowered the barrier to entry for generic competition.

- The “Orange Book”: The Act mandated the creation of the FDA’s publication, “Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations,” now known as the Orange Book. Innovator companies are required to list the patents they assert cover their approved drugs in the Orange Book, which then serves as the official battlefield map for all subsequent patent disputes.6

- The Paragraph IV Certification: The Act created a formal, highly stylized mechanism for initiating a patent challenge. When a generic company files an ANDA, it must make a certification for each patent listed in the Orange Book for the reference drug. A “Paragraph IV” certification is an assertion by the generic company that the listed patent is invalid, unenforceable, or will not be infringed by the generic product.28 Critically, the Act defines the filing of a Paragraph IV certification as an “artificial” act of patent infringement, which allows the innovator to sue the generic company immediately, long before the generic drug is actually sold.6

- The 30-Month Stay of Approval: To give innovators a meaningful chance to defend their patents, the Act created an automatic injunction. If the brand company files a patent infringement lawsuit within 45 days of receiving notice of a Paragraph IV certification, the FDA is automatically prohibited from granting final approval to the generic’s ANDA for a period of up to 30 months.6 This provides a crucial window for litigation to proceed.

- The 180-Day Exclusivity Incentive: To encourage these challenges, the Act created a powerful financial reward. The first generic applicant to file an ANDA with a Paragraph IV certification is granted a 180-day period of marketing exclusivity upon approval.4 During this six-month period, the FDA cannot approve any other generic versions of the same drug, allowing the first challenger to capture a significant portion of the market, often at a price only moderately lower than the brand.

The genius of the Hatch-Waxman Act lies not just in creating a pathway for generics, but in its deliberate engineering of patent litigation as the primary engine of market competition. The law inextricably links the FDA approval process to the patent system. The only way for a generic company to enter the market before a patent’s natural expiration is to proactively challenge that patent through a Paragraph IV filing. The Act then defines this very act of challenging as an infringement, thereby guaranteeing that the dispute will land in court. Furthermore, the lucrative 180-day exclusivity prize creates a powerful “race-to-file” incentive among generic manufacturers, ensuring that the patents on nearly every commercially successful drug will be challenged.28 This makes patent litigation not an unforeseen risk, but a predictable and integral part of the business model for both innovator and generic companies. This legislatively engineered conflict has, in turn, spawned a highly specialized ecosystem of law firms with deep scientific expertise, expert witnesses, and competitive intelligence platforms all dedicated to navigating this unique intersection of science, law, and commerce.35

Deconstructing the Patent: The Scientific and Legal Grounds for Invalidation

Challenging a drug patent is an exercise in deconstruction. It requires a challenger to dissect the patent’s claims and demonstrate that the invention, as claimed, fails to meet the strict legal requirements for patentability set forth in the U.S. Patent Act. While several grounds for invalidity exist, the battle is most often fought on the scientific and technical merits of three core pillars: novelty, non-obviousness, and adequate disclosure. Each represents a distinct line of attack, requiring a unique blend of legal argument and scientific evidence.

The Novelty Requirement (35 U.S.C. § 102): Proving It Wasn’t New

The most fundamental prerequisite for a patent is novelty: an invention must be new.14 If an invention was already known or publicly disclosed before the patent application was filed, it cannot be patented. In legal terms, a patent claim that fails the novelty test is said to be “anticipated” by the “prior art”.33

To prove anticipation, a challenger must satisfy the stringent “single prior art reference” rule. This requires showing that each and every element of the patent’s claim is disclosed, either explicitly or inherently, within the four corners of a single piece of prior art.15 This prior art reference can be a previously issued patent, a published scientific journal article, a doctoral thesis, a conference presentation, or any other information made publicly available anywhere in the world before the patent’s effective filing date.33

A more nuanced form of this challenge is the doctrine of “inherent anticipation.” This argument applies when a prior art reference does not explicitly spell out every element of the claimed invention, but a property or outcome of the claim is the natural and inevitable result of practicing what is described in the prior art.33 For instance, imagine a new patent claims a specific crystalline form (polymorph) of a drug that offers improved stability. A challenger could invalidate this patent by finding an old scientific paper that describes a method of synthesizing the drug. If the challenger can then prove through new experimental data that following the old paper’s method

inherently and necessarily produces the newly claimed, more stable polymorph—even if the original authors never recognized it—the new patent is invalid for lack of novelty.33

While conceptually straightforward, a successful novelty challenge against the core composition-of-matter patent for a truly new drug is relatively rare. The patent examiners at the USPTO are required to conduct their own prior art search before granting a patent, and they are unlikely to miss a direct disclosure of the exact same molecule.9 However, anticipation is a potent weapon against weaker, later-filed secondary patents. Innovators often file patents on new formulations or new methods of use years after the initial drug discovery, by which time a much larger body of scientific literature and public knowledge exists. Challengers frequently find success by unearthing an obscure journal article that hinted at a new therapeutic use or described a formulation so similar to a later-patented one that it anticipates the claims. This dynamic creates a strategic tension for innovator companies: they must publish clinical data to promote their drug and support its approval, yet every publication they produce becomes potential prior art that could be used to invalidate their

future patents on lifecycle improvements.9

The Non-Obviousness Hurdle (35 U.S.C. § 103): The Ultimate Question of Inventiveness

By far the most common, complex, and frequently successful ground for invalidating a drug patent is the requirement of non-obviousness.33 Under 35 U.S.C. § 103, an invention, even if it is technically new (i.e., not anticipated), is not patentable if the differences between the invention and the prior art are such that the invention as a whole would have been “obvious” at the time it was made to a “person having ordinary skill in the art” (a POSITA).15 This standard prevents the patenting of trivial advancements that do not represent a true inventive leap.

The Supreme Court, in its seminal 1966 case Graham v. John Deere Co., established a foundational four-part factual framework for the obviousness inquiry 39:

- Determine the scope and content of the prior art.

- Ascertain the differences between the prior art and the claims at issue.

- Resolve the level of ordinary skill in the pertinent art.

- Evaluate objective evidence of non-obviousness, known as “secondary considerations.”

For decades, courts applied a rigid “teaching, suggestion, or motivation” (TSM) test, which required a challenger to find an explicit suggestion in the prior art to combine different references to arrive at the claimed invention. However, in its 2007 landmark decision KSR International Co. v. Teleflex Inc., the Supreme Court rejected this rigid test in favor of a more flexible, expansive, and common-sense approach.39 This decision fundamentally shifted the balance of power in obviousness litigation toward challengers by opening up several potent lines of argument:

- Combining Prior Art References: The most common obviousness argument involves combining the teachings of two or more prior art references. The challenger argues that a POSITA, faced with a known problem, would have been motivated to piece together known elements from different sources and would have had a “reasonable expectation of success” in doing so.15 For example, if one reference discloses a class of compounds for treating a disease and a second reference teaches that adding a specific chemical group to similar compounds improves their bioavailability, it may be obvious to add that group to the first compound.

- “Obvious to Try”: This argument is particularly powerful in pharmaceutical development, which often involves routine optimization. If the prior art identifies a known problem (e.g., poor stability) and there are a finite number of identified, predictable solutions (e.g., a handful of well-known stabilizing agents), a court may find it was obvious to try those solutions.41 This applies to optimizing variables like dosage, pH, or excipients in a formulation.

- Obviousness of Ranges: A patent claim reciting a specific range (e.g., a dosage of 5-10 mg, a pH of 3.0-4.0) can be rendered obvious if the prior art discloses an overlapping range for a structurally and functionally similar compound.46 The Federal Circuit has affirmed that this can establish a

prima facie case of obviousness, shifting the burden to the patent holder to prove the specific claimed range is critical and yields unexpected results.46

To rebut a charge of obviousness, the patent holder must present objective evidence—the “secondary considerations” from the Graham framework—to show that the invention was, in fact, not obvious. This evidence can be very powerful and includes 33:

- Unexpected Results: Demonstrating that the invention produced a surprising or superior result that would not have been predicted from the prior art. In combination therapies, this often involves showing a synergistic effect, where the combination is more effective than the sum of its parts.48

- Long-Felt But Unsolved Need: Proving that others were aware of a problem for a long time but were unable to solve it until the patented invention came along.

- Failure of Others: Showing that other skilled researchers tried and failed to achieve the same result.

- Commercial Success: Evidence that the product was a commercial success can be an indicator of non-obviousness, although this argument can be weakened if the success is due to marketing or other factors rather than the merits of the invention itself.

The KSR decision’s shift away from a rigid TSM test has made secondary patents significantly more vulnerable. It is no longer enough for an innovator to argue that no single paper explicitly suggested combining two ideas. The inquiry is now whether the combination was a “predictable use of prior art elements according to their established functions”.42 This places a much greater burden on innovators to demonstrate non-predictability. As a result, the “unexpected results” argument has become the paramount defense against an obviousness challenge.48 To build a defensible patent portfolio, particularly for lifecycle improvements, it is no longer sufficient to make a logical, incremental advance; the advance must be demonstrably surprising. This legal standard now directly influences scientific methodology, compelling companies to conduct extensive comparative testing early in development to generate the data needed to prove unexpected superiority over the prior art, knowing that an obviousness challenge is all but inevitable.

The Disclosure Mandates (35 U.S.C. § 112): Enablement and Written Description

A patent is a bargain with the public: in exchange for a limited monopoly, the inventor must provide a full and clear disclosure of the invention so that the public may practice it after the patent expires. This is enforced through two distinct but related requirements under 35 U.S.C. § 112: written description and enablement.49

- Written Description: The patent’s specification must demonstrate that the inventor was “in possession” of the claimed invention as of the filing date.39 This requirement prevents an applicant from later adding claims to cover developments made after the initial filing, ensuring they cannot claim more than they had actually invented at the time.

- Enablement: The specification must teach a person of ordinary skill in the art (POSITA) how to make and use the full scope of the claimed invention without requiring “undue experimentation”.39 The disclosure cannot be so vague or incomplete that a skilled person would have to embark on their own research project to replicate the invention.

For years, these requirements were a standard battleground, but the landscape was dramatically reshaped by the Supreme Court’s 2023 decision in Amgen Inc. v. Sanofi. The case involved patents covering an entire class of antibodies defined by their function: binding to the PCSK9 protein and lowering LDL cholesterol. Amgen’s patents disclosed the amino acid sequences for only a small number of exemplary antibodies and provided a “roadmap” for scientists to generate and screen other candidates that would perform the same function. The Supreme Court unanimously held that this was not enough.19 The Court ruled that when an inventor claims an entire genus of compounds by their function, the patent must enable a POSITA to “make and use the entire class.” Providing a few examples and a method for trial-and-error discovery—a “hunting license,” in the Court’s words—is insufficient to enable the “vast” scope of such a claim.19

The Amgen decision represents a seismic shift in patent law, swinging the pendulum decisively against broad, functionally-defined genus claims. It has created a significant new vulnerability for many existing patents, particularly in the field of biologics, and has forced a fundamental rethinking of patent drafting strategy. Patent applicants can no longer rely on broad functional language to corner an entire field of research. Instead, claims must be more closely tethered to the specific structures that have been actually made and tested. This likely necessitates a strategy of filing a series of narrower patents over time as new discoveries are made, rather than a single, all-encompassing patent at the outset. For early-stage biotechnology companies, this creates a difficult strategic dilemma: they rely on broad patent claims to attract venture capital and signal their command of a technology platform, but the very breadth of those claims now makes them highly susceptible to an enablement challenge. This landmark ruling has opened a new and powerful front for challenges by generic and biosimilar manufacturers and is already reshaping investment and innovation strategy in the life sciences.

Table 2: Key Grounds for Patent Invalidity and Common Scientific Arguments

| Legal Ground for Invalidity | Governing Statute | Common Scientific Arguments & Evidence |

| Lack of Novelty (Anticipation) | 35 U.S.C. § 102 | Finding a single prior art reference (e.g., a scientific paper, another patent) that discloses every element of the patent’s claim. Providing experimental evidence that a process described in the prior art inherently and necessarily produces the claimed invention.33 |

| Obviousness | 35 U.S.C. § 103 | Combining teachings from multiple prior art references to argue a person of skill would have arrived at the invention with a reasonable expectation of success. Arguing it was “obvious to try” a finite number of predictable solutions (e.g., testing known stabilizers). Showing a claimed range overlaps with a prior art range for a similar compound.45 |

| Lack of Enablement / Written Description | 35 U.S.C. § 112 | Arguing that the patent’s claims are broader than what the specification teaches, requiring “undue experimentation” to practice. Arguing the inventor was not in “possession” of the full claimed scope, especially for broad genus claims with few examples, per the Amgen v. Sanofi standard.19 |

| Patent Ineligible Subject Matter | 35 U.S.C. § 101 | Arguing the claim is directed to an unpatentable law of nature (e.g., a correlation between a biomarker and a disease), a natural phenomenon, or an abstract idea, without adding a sufficient “inventive concept”.33 |

Other Avenues of Attack

Beyond the “big three” of novelty, obviousness, and disclosure, challengers have several other weapons in their arsenal:

- Lack of Utility (35 U.S.C. § 101): An invention must have a “specific, substantial, and credible” utility.15 While this is rarely a successful challenge against a drug that has already received FDA approval, it can be a vulnerability for patents filed very early in the discovery process before a clear therapeutic use has been established.

- Patent Ineligible Subject Matter (35 U.S.C. § 101): The Supreme Court has affirmed that laws of nature, natural phenomena, and abstract ideas are not patentable.43 This has had a profound impact on patents for diagnostic methods (which often claim a natural correlation between a biomarker and a disease state), as seen in

Mayo v. Prometheus, and on patents claiming isolated human DNA, as decided in Association for Molecular Pathology v. Myriad Genetics.40 - Incorrect Inventorship: A patent can be invalidated if it fails to name all of the true inventors or improperly names individuals who did not make an inventive contribution.33

- Inequitable Conduct: This is a defense that can render a patent completely unenforceable. It requires proving that the patent applicant intentionally withheld material information from the USPTO or submitted false information with an intent to deceive the patent examiner.33 This is a very high bar to meet, as it requires clear and convincing evidence of deceptive intent, but it can be a “death penalty” for a patent if proven.

The Challenger’s Playbook: Forums, Tactics, and Execution

A successful drug patent challenge is not merely a legal argument; it is a meticulously planned and executed strategic campaign. It involves choosing the right battlefield, deploying the right intelligence-gathering tools, and assembling a multidisciplinary team of experts. The modern challenger’s playbook is defined by a sophisticated understanding of the procedural advantages offered by different legal forums and the use of data analytics to identify and exploit the weakest points in an innovator’s patent fortress.

Choosing the Battlefield: District Court vs. The Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB)

Perhaps the most critical strategic decision a challenger makes is where to fight. Since the passage of the America Invents Act (AIA) in 2011, challengers have two primary forums: traditional Hatch-Waxman litigation in federal district court and administrative challenges before the USPTO’s Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB).25 The PTAB offers a proceeding known as

Inter Partes Review (IPR), which has become the preferred venue for many challengers due to its distinct procedural advantages.25

The IPR process was created by Congress as a faster, more efficient, and less expensive alternative to district court litigation, specifically designed to allow the USPTO to take a “second look” at issued patents and weed out those of poor quality.25 For a generic or biosimilar manufacturer, the IPR process offers a powerful set of advantages that are detailed in Table 3.

Table 3: A Tale of Two Forums: Hatch-Waxman Litigation vs. Inter Partes Review (IPR)

| Feature | District Court (Hatch-Waxman Litigation) | PTAB (Inter Partes Review) |

| Decision-Maker | Federal District Judge; potentially a jury on factual questions | Panel of 3 technically-trained Administrative Patent Judges (APJs) 25 |

| Standard of Proof | Invalidity must be proven by “Clear and Convincing Evidence” 51 | Unpatentability proven by a “Preponderance of the Evidence” (a lower standard) 51 |

| Presumption of Validity | An issued patent is presumed to be valid by statute 51 | There is no presumption of validity 54 |

| Grounds for Challenge | All grounds of invalidity (novelty, obviousness, enablement, written description, etc.) 17 | Limited to novelty (§ 102) and obviousness (§ 103) based only on prior art patents or printed publications 33 |

| Timeline to Final Decision | Typically 2.5 to 4 years 56 | Statutorily mandated to be completed within 18 months from institution 25 |

| Cost | Can run into millions or tens of millions of dollars 51 | Typically in the hundreds of thousands of dollars 51 |

| Claim Construction | Phillips standard: claims are given their ordinary and customary meaning to a POSITA | Broadest Reasonable Interpretation (BRI) consistent with the specification (historically; now closer to Phillips) |

| Estoppel Effect | Narrower preclusive effect on future litigation | Broader: petitioner is estopped from later asserting any ground that it raised or reasonably could have raised during the IPR 30 |

The procedural advantages of the PTAB are so significant that it has fundamentally altered the strategic calculus of patent litigation. An issued patent is objectively more likely to be invalidated in an IPR than in a district court. The combination of a lower burden of proof, no presumption of validity, and technically expert judges has led to high rates of IPR institution and claim cancellation.25 For fiscal year 2024, the institution rate for bio/pharma patents was approximately 73%, the highest of any technology sector.57 This has made the PTAB an indispensable tool for challengers.

The PTAB is not merely an alternative venue; it is a strategic lever. A common and highly effective strategy is to launch a parallel attack: filing an IPR at the PTAB while simultaneously defending against an infringement suit in district court.30 The threat of a relatively quick, inexpensive, and high-probability loss at the PTAB puts immense pressure on the innovator company. It can force the innovator to consider settling the entire dispute on terms more favorable to the generic, transforming the IPR into a tool for achieving a business resolution, not just a legal one. This strategic power has not gone unnoticed. Innovator lobbying groups have criticized the PTAB, arguing it creates undue uncertainty and represents a “second bite at the apple” that disrupts the delicate balance of the Hatch-Waxman Act.55 In contrast, generic industry groups defend the PTAB as a vital administrative check on the issuance of weak patents by an overburdened USPTO.25 This political tug-of-war has led to legislative proposals, such as the PREVAIL Act, which seeks to raise the standard of proof in IPRs and limit who can file them, demonstrating that the procedural rules of this administrative body have become a central battleground for the future of pharmaceutical competition.58

The Art of the Prior Art Search: Uncovering the Achilles’ Heel

The foundation of any invalidity challenge based on novelty or obviousness is an exhaustive and meticulously executed prior art search.60 The goal is to uncover the “smoking gun” reference or combination of references that can fatally undermine a patent’s claims. This process is far more than a simple keyword search; it is a sophisticated investigative discipline.

A comprehensive search must canvas a wide array of sources, including both patent and non-patent literature.62 This includes global patent databases like those maintained by the USPTO, the European Patent Office (Espacenet), and the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), as well as search engines like Google Patents.18 Equally important is a deep dive into non-patent literature, such as peer-reviewed scientific journals, academic dissertations, conference proceedings, and textbooks, as these often contain the critical scientific disclosures needed to build an obviousness case.61 For complex pharmaceutical inventions, specialized databases are indispensable. Platforms like CAS STNext provide powerful tools for searching chemical structures (including broad Markush structures) and biological sequences, capabilities that are absent from public databases.62

Effective search strategies employ a multi-pronged approach:

- Keyword and Classification Searching: This involves developing a comprehensive list of keywords and synonyms for the invention’s key concepts and using patent classification systems like the Cooperative Patent Classification (CPC) to systematically search relevant technology areas.61

- Citation Analysis: This involves “backward” searching to review the prior art cited by the patent in question and “forward” searching to find later patents that have cited the target patent, often revealing a web of closely related art.64

- Advanced Search Logic: Expert searchers utilize Boolean operators (AND, OR, NOT) and proximity operators (e.g., NEAR/n, which finds terms within a specified number of words of each other) to construct highly precise queries that can uncover connections between concepts that a simple keyword search would miss.18

In the modern era, the prior art search has evolved from a purely defensive legal step into a proactive form of competitive intelligence that shapes both R&D and business strategy.12 Because patent applications are typically published 18 months after filing, they provide an early window into a competitor’s research pipeline, often years before a product reaches the market.4 A generic company’s search for invalidating prior art can simultaneously reveal technical gaps and opportunities for designing a non-infringing alternative product. An innovator’s “freedom to operate” search, conducted to ensure its own product does not infringe on existing patents, can identify potential acquisition targets or in-licensing opportunities.12 The search thus becomes a dual-purpose tool for both offensive litigation and strategic business development. The increasing sophistication of search platforms, particularly those leveraging artificial intelligence, is making the vast universe of prior art more accessible than ever.65 This, in turn, is raising the bar for what a POSITA is presumed to know, subtly but surely influencing the legal standard of non-obviousness itself.

Assembling the Team and Leveraging Experts

Successfully challenging a drug patent is a team sport that requires the seamless integration of legal, scientific, and regulatory expertise.30 The complexity of the subject matter demands a multidisciplinary approach.

The legal team is led by experienced patent litigators who possess not only deep knowledge of the law but also a strong grasp of the underlying science. Many of the most effective pharmaceutical patent attorneys hold advanced scientific degrees, such as Ph.D.s in organic chemistry, molecular biology, or pharmacology, which allows them to communicate effectively with scientific experts and translate highly technical concepts into persuasive legal arguments for a judge or jury.35 This team must also include regulatory counsel who are masters of the intricate rules of the Hatch-Waxman Act and FDA procedures.

Equally critical to the team are the external expert witnesses.17 These are typically highly respected academics or seasoned industry veterans who are retained to provide testimony on the central questions of a case: the scope of the prior art, the level of skill of a POSITA, and whether the patented invention would have been obvious.30 The credibility, clarity, and persuasiveness of these experts can be the deciding factor in a case. They are responsible for educating the judge and jury on the complex science and providing the technical foundation for the legal arguments of obviousness or non-infringement. In the specialized forum of the PTAB, where the decision is made by technically-trained judges, the quality of the expert’s declaration and deposition testimony is paramount.52

The Role of Competitive Intelligence and Data Analytics

While legal and scientific arguments are the weapons of a patent challenge, the strategy is guided by data. Winning is not just about invalidating a patent; it is about winning the market, which requires a deep understanding of the commercial landscape and the economic stakes involved.31 Modern challengers leverage sophisticated data analytics and competitive intelligence platforms to inform every stage of their strategy.8

Platforms like DrugPatentWatch provide a comprehensive, integrated view of the biopharmaceutical landscape, combining data on patent portfolios, expiration dates, ongoing litigation, regulatory exclusivities, historical drug sales, and Paragraph IV filing activity.4 This data is transformed into actionable intelligence that allows a challenger to:

- Identify High-Value Targets: By tracking upcoming “patent cliffs”—the period when blockbuster drugs are set to lose exclusivity—companies can prioritize which drugs offer the most lucrative opportunities for a generic challenge.67

- Assess Portfolio Vulnerability: Analyzing an innovator’s entire patent thicket helps identify the weakest patents—those with questionable validity or narrow claims—which can be targeted first to gain leverage.37

- Optimize Market Entry Timing: Data on 30-month stays, ongoing IPRs, and settlement trends helps companies forecast potential launch dates and plan their manufacturing and supply chain readiness accordingly.37

- Refine Legal Strategy: Studying the outcomes of past patent challenges, including failed challenges and settlement terms, provides valuable insights into which arguments are most effective against certain types of patents and which judges or forums may be more favorable.37

By integrating this data-driven approach, a challenger can move beyond a purely legal analysis and craft a holistic business strategy designed to maximize the probability of a successful and profitable market entry.

The Innovator’s Defense and the Evolving Landscape

The battle over drug patents is a dynamic chess match, and for every offensive strategy employed by a challenger, there is a corresponding defensive maneuver from the innovator. Brand-name pharmaceutical companies have developed a sophisticated playbook to protect their revenue streams, extend the commercial life of their products, and counter the threats posed by generic and biosimilar competition. This playbook, however, is constantly being tested and reshaped by a rapidly evolving legal and regulatory landscape, where landmark court rulings and new technologies continually redraw the boundaries of the battlefield.

Defending the Fortress: The Innovator’s Playbook

An innovator’s best defense is built long before a patent challenge is ever filed. It is a proactive, multi-layered strategy designed to fortify their intellectual property and commercial position.

- Proactive Portfolio Construction: As discussed previously, the primary defensive strategy is the meticulous construction of a “patent thicket”.17 By securing a dense web of patents covering the active ingredient, formulations, methods of use, manufacturing processes, and polymorphs, the innovator raises the cost and complexity of any potential challenge, creating a powerful deterrent.11

- Lifecycle Management and “Evergreening”: This is the practice of continuously innovating around a successful drug to obtain new patents that extend its effective market exclusivity.1 This can involve developing and patenting new extended-release formulations, discovering and patenting new therapeutic indications for the drug, or creating new combination products that pair the drug with another active ingredient.6 While critics argue this practice can stifle competition without providing significant new therapeutic value, defenders maintain it protects new and useful inventions that often improve patient compliance or outcomes.1

- Litigation and Settlement Strategies: When a Paragraph IV challenge is inevitably filed, the innovator must react swiftly. Filing a lawsuit within the 45-day window triggers the automatic 30-month stay of FDA approval, providing a critical buffer to litigate.17 The innovator then faces a strategic choice: fight the case through trial or seek a settlement. Settlements can be advantageous, providing certainty and potentially preserving some period of exclusivity. However, so-called “pay-for-delay” or “reverse payment” settlements, where the innovator compensates the generic manufacturer to delay its market entry, have come under intense antitrust scrutiny from the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and courts.1

- Commercial Defense Tactics: Innovators also deploy commercial strategies to mitigate the impact of generic entry.

- Authorized Generics: The brand company can launch its own generic version of the drug, often through a subsidiary.4 This allows them to compete directly on price and capture a share of the generic market. A key strategic use of this tactic is to launch during the first challenger’s 180-day exclusivity period, which can dramatically reduce the first filer’s profits and lessen the incentive for future challenges.

- “Product Hopping”: Just before a patent expires on an older formulation (e.g., a twice-daily pill), the innovator may pull that product from the market and heavily promote a new, patent-protected version (e.g., a once-daily pill).1 This “hard switch” can effectively migrate the market to the new product, making it difficult for pharmacists to automatically substitute a generic version of the older drug. This practice has also faced significant antitrust challenges.

Landmark Rulings and Their Strategic Implications (2023-2025)

The legal ground beneath the pharmaceutical patent landscape is constantly shifting, with recent court decisions creating new vulnerabilities for innovators and new opportunities for challengers.

- Enablement and Genus Claims (Amgen v. Sanofi, 2023): As detailed in Part II, this Supreme Court decision has made it significantly more difficult to defend broad, functionally-defined patent claims, particularly for biologics. The ruling provides a powerful new weapon for biosimilar manufacturers to challenge entire classes of antibody patents based on a lack of enablement.19

- Orange Book Listing Requirements (Teva v. Amneal, 2024): The Federal Circuit’s landmark ruling that a patent must claim the active ingredient to be properly listed in the Orange Book has major implications.69 This decision invalidates the common practice of listing patents that cover only a drug delivery device (like an inhaler) but not the drug substance itself. It is expected to trigger a wave of delisting challenges from generic companies and has been championed by the FTC as a victory against anticompetitive practices that exploit the 30-month stay.

- Obviousness of Polymorphs (Salix v. Norwich, 2024): The Federal Circuit’s decision in this case has made it easier to challenge patents on specific crystalline forms (polymorphs) on obviousness grounds.56 By distinguishing from prior precedent that had made such challenges difficult, the court has weakened a key tool used in lifecycle management, making these secondary patents more vulnerable.

- “Skinny Labels” and Induced Infringement (Amarin v. Hikma, 2024): The Federal Circuit revived an induced infringement lawsuit against a generic manufacturer that had used a “skinny label” to carve out a patented use. The court found that the generic company’s public statements and press releases could be used as evidence that it intended to encourage doctors to prescribe the drug for the patented (infringing) use.70 This decision creates significant new risks for generic companies relying on the skinny label strategy to enter the market for unpatented uses.

- Obviousness-Type Double Patenting and PTA (In re Cellect, 2023): The Federal Circuit held that Patent Term Adjustments (PTA)—granted to compensate for USPTO delays—do not shield a patent from being invalidated for obviousness-type double patenting (ODP) by an earlier-expiring patent in the same family.47 This ruling complicates patent prosecution strategies and creates new vulnerabilities for patent families, potentially forcing applicants to disclaim patent term they would have otherwise been granted.

Recent litigation statistics reflect this dynamic environment. While innovator companies tend to prevail more often when cases go to a final decision at trial in district court, a significant number of cases are resolved through settlement.56 ANDA case filings, after a period of decline, appear to be stabilizing, with the Districts of Delaware and New Jersey remaining the primary judicial battlegrounds.47

The Next Frontier: AI, Biologics, and Legislative Reform

The future of pharmaceutical patent challenges will be shaped by emerging technologies and potential legislative changes.

- The Impact of Artificial Intelligence (AI): AI is poised to revolutionize drug discovery by dramatically accelerating the identification of new drug candidates.65 This creates profound new challenges for patent law. The U.S. requirement for a human inventor means that an invention conceived solely by an AI is not patentable.65 The key legal question will be what level of “significant contribution” a human scientist must make to an AI-assisted discovery to qualify as an inventor.71 Furthermore, as AI tools become a standard part of the toolkit for a POSITA, the legal standard for non-obviousness will inevitably rise. It will become harder to argue that a new molecule is non-obvious if a standard AI algorithm could have easily predicted it.65

- The Complexity of Biologics: Litigation over biosimilars is governed by a separate but parallel statutory scheme, the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA), which has its own unique procedures for resolving patent disputes, including a complex information exchange known as the “patent dance”.4 Because biologics are large, complex molecules often defined by their manufacturing process, their patent thickets tend to be even denser and more focused on process patents than those for small-molecule drugs.11

- The Legislative Horizon: The ongoing debate over the proper balance between innovation and access continues in Congress. Proposed legislation like the PREVAIL Act seeks to strengthen patents by making it harder to challenge them at the PTAB, for example, by raising the burden of proof to “clear and convincing evidence”.58 Conversely, other legislative efforts aim to curb perceived abuses of the patent system, such as “pay-for-delay” settlements. These proposals reflect the deep political and economic divisions over the role of patents in healthcare costs and signal that the rules of the game will continue to evolve.

Conclusion

The art of challenging a drug patent is a sophisticated endeavor that operates at the dynamic confluence of advanced science, intricate law, and high-stakes business strategy. It is a field defined not by singular events, but by a continuous, strategic interplay between innovator and challenger, played out across multiple forums and governed by a legal framework that is itself in a constant state of flux.

The analysis reveals that the entire system of pharmaceutical patent litigation is a direct and intended consequence of a foundational structural tension: the significant gap between a patent’s 20-year statutory term and its much shorter 7-to-10-year effective market life. This “20-year illusion” creates the immense economic pressure that drives innovators to construct formidable “patent thickets” and employ complex lifecycle management strategies to extend their monopolies. In turn, the Hatch-Waxman Act was ingeniously designed to harness the competitive pressures of the market by engineering patent litigation—incentivized by the lucrative 180-day exclusivity period—as the primary mechanism for policing the validity of these patents and facilitating generic entry.

A successful challenge is therefore not a simple legal contest but a multi-front campaign. It requires a deep scientific deconstruction of the patent to identify vulnerabilities in novelty, non-obviousness, or disclosure, supported by exhaustive prior art research. It demands a shrewd choice of battlefield, strategically leveraging the procedural advantages of the PTAB’s Inter Partes Review process to exert maximum pressure on the patent holder. Ultimately, it relies on the seamless integration of a multidisciplinary team of legal, scientific, and regulatory experts, all guided by data-driven competitive intelligence.

The landscape is becoming ever more complex. Landmark court decisions like Amgen v. Sanofi and Teva v. Amneal are creating significant new vulnerabilities in long-held patenting strategies for biologics and drug-device combinations. At the same time, the rise of artificial intelligence in drug discovery is beginning to challenge the very definitions of inventorship and obviousness. For both the innovator defending their fortress and the challenger seeking to breach its walls, success will depend on an adaptive, forward-looking strategy that anticipates these shifts and masterfully integrates scientific evidence with legal acumen. In this high-stakes arena, the art of the challenge is, and will remain, the art of turning science into legal leverage.

Works cited

- The Role of Patents and Regulatory Exclusivities in Drug Pricing | Congress.gov, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/R46679

- The Role of Patents in the Pharmaceutical Sector – Minesoft, accessed August 5, 2025, https://minesoft.com/the-role-of-patents-in-the-pharmaceutical-sector/

- WIPO/IFIA/BUE/00/9: Patenting Strategies: When, What and Why: How Should Inventors amd SMEs Plan for Obtaining Protection for their Inventions; Use of Public or Private Services, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.wipo.int/edocs/mdocs/innovation/en/wipo_ifia_bue_00/wipo_ifia_bue_00_9-main1.doc

- Drug Patent Life: The Complete Guide to Pharmaceutical Patent …, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/how-long-do-drug-patents-last/

- When Do Drug Patents Expire: Understanding the Lifecycle of Pharmaceutical Innovations, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/when-do-drug-patents-expire/

- How Drug Life-Cycle Management Patent Strategies May Impact Formulary Management, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.ajmc.com/view/a636-article

- Drug Patents: How Pharmaceutical IP Incentivizes Innovation and Affects Pricing, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.als.net/news/drug-patents/

- Managing Patent Portfolios in the Pharmaceutical Industry | PatentPC, accessed August 5, 2025, https://patentpc.com/blog/managing-patent-portfolios-in-the-pharmaceutical-industry

- Patent protection strategies – PMC, accessed August 5, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3146086/

- Why Are Patents Important to Drug Development? | Infinix Bio, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.infinixbio.com/why-patents-important-drug-development/

- The Pharmaceutical Patent Playbook: Forging Competitive …, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/developing-a-comprehensive-drug-patent-strategy/

- Strategic Imperatives: Leveraging Patent Pending Data for …, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/leveraging-patent-pending-data-for-pharmaceuticals/

- Navigating pharma loss of exclusivity | EY – US, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.ey.com/en_us/insights/life-sciences/navigating-pharma-loss-of-exclusivity

- Pharmaceutical Patent Regulation in the United States – The Actuary Magazine, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.theactuarymagazine.org/pharmaceutical-patent-regulation-in-the-united-states/

- Patent Requirements (BitLaw), accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.bitlaw.com/patent/requirements.html

- Drug patents: innovation v. accessibility – PMC, accessed August 5, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3680575/

- Patent Defense Isn’t a Legal Problem. It’s a Strategy Problem. Patent …, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/patent-defense-isnt-a-legal-problem-its-a-strategy-problem-patent-defense-tactics-that-every-pharma-company-needs/

- A Business Professional’s Guide to Drug Patent Searching – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-basics-of-drug-patent-searching/

- Patent Decisions Affecting Pharma & Biotech Companies – McDermott, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.mwe.com/insights/2023-ip-outlook-patent-decisions-affecting-pharma-and-biotech-companies/

- Pharmaceutical Lifecycle Management – Torrey Pines Law Group, accessed August 5, 2025, https://torreypineslaw.com/pharmaceutical-lifecycle-management.html

- Optimizing Your Drug Patent Strategy: A Comprehensive Guide for Pharmaceutical Companies – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/optimizing-your-drug-patent-strategy-a-comprehensive-guide-for-pharmaceutical-companies/

- 40th Anniversary of the Generic Drug Approval Pathway | FDA, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/cder-conversations/40th-anniversary-generic-drug-approval-pathway

- What is Hatch-Waxman? – PhRMA, accessed August 5, 2025, https://phrma.org/resources/what-is-hatch-waxman

- A Bipartisan Success: Celebrating 40 Years of the Hatch-Waxman …, accessed August 5, 2025, https://itif.org/publications/2025/02/03/a-bipartisan-success-celebrating-40-years-of-the-hatch-waxman-act/

- Inter Partes Review (IPR) Is Necessary to Lower Drug Prices by …, accessed August 5, 2025, https://accessiblemeds.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/AAM-IssueBrief-InterPartesReview_0.pdf

- 40 Years of Hatch-Waxman: What is the Hatch-Waxman Act? | PhRMA, accessed August 5, 2025, https://phrma.org/blog/40-years-of-hatch-waxman-what-is-the-hatch-waxman-act

- Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act – Wikipedia, accessed August 5, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Drug_Price_Competition_and_Patent_Term_Restoration_Act

- The Hatch-Waxman Act (Simply Explained) – Biotech Patent Law, accessed August 5, 2025, https://berksiplaw.com/2019/06/the-hatch-waxman-act-simply-explained/

- 21 U.S. Code § 355 – New drugs – Law.Cornell.Edu, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/21/355

- Key Strategies for Successfully Challenging a Drug Patent …, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/key-strategies-for-successfully-challenging-a-drug-patent/

- You Don’t Need to Win the Patent — You Need to Win the Market: What No One Tells You About Winning Drug Patent Challenges – DrugPatentWatch – Transform Data into Market Domination, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/you-dont-need-to-win-the-patent-you-need-to-win-the-market-what-no-one-tells-you-about-winning-drug-patent-challenges/

- Hatch-Waxman Act – Practical Law, accessed August 5, 2025, https://uk.practicallaw.thomsonreuters.com/Glossary/PracticalLaw/I2e45aeaf642211e38578f7ccc38dcbee

- Handling Drug Patent Invalidity Claims – DrugPatentWatch – Transform Data into Market Domination, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/handling-drug-patent-invalidity-claims/

- Hatch-Waxman Litigation: A Deep Dive – Number Analytics, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.numberanalytics.com/blog/hatch-waxman-litigation-deep-dive

- Overview | Patent Litigation | Patterson Belknap Webb & Tyler LLP, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.pbwt.com/patent-litigation

- Life Sciences Patent – IP Law Firm | Fish & Richardson, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.fr.com/industries/life-sciences/

- DrugPatentWatch not only saved us valuable time in tracking patent …, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/

- Patent Litigation | Paul, Weiss, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.paulweiss.com/practices/litigation/patent-litigation

- patent | Wex | US Law | LII / Legal Information Institute, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/patent

- Identifying and Invalidating Weak Drug Patents in the United States – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/identifying-and-invalidating-weak-drug-patents-in-the-united-states/

- Requirements for a Patent: Utility, Novelty, and Non-obviousness, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.brettoniplaw.com/requirements%20for%20a%20patent.html

- 2141-Examination Guidelines for Determining Obviousness Under …, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.uspto.gov/web/offices/pac/mpep/s2141.html

- Patent Cases That Shaped Modern Intellectual … – Robert Walat, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.robertwalat.com/landmark-patent-cases-that-shaped-modern-intellectual-property-law/

- Federal Circuit refines obviousness framework for drug and biologic dosing regimens, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.dlapiper.com/en/insights/publications/synthesis/2025/federal-circuit-refines-obviousness-framework-for-drug-and-biologic-dosing-regimens

- 2143-Examples of Basic Requirements of a Prima Facie Case of Obviousness – USPTO, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.uspto.gov/web/offices/pac/mpep/s2143.html

- Federal Circuit Ruling in Patent Case Expands ‘Obviousness’ Doctrine, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.harrisbeachmurtha.com/insights/federal-circuit-ruling-in-patent-case-expands-obviousness-doctrine/

- Hatch-Waxman 2023 Year in Review – Fish & Richardson, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.fr.com/insights/thought-leadership/articles/hatch-waxman-2023-year-in-review-2/

- Obviousness in Drug Combinations – Unexpected Results Vs. Unexpected Mechanisms of Action | MoFo Life Sciences, accessed August 5, 2025, https://lifesciences.mofo.com/topics/obviousness-in-drug-combinations-unexpected-results-vs-unexpected-mechanisms-of-action

- What is the difference between the written description and enablement requirements in patent law? – BlueIron IP, accessed August 5, 2025, https://blueironip.com/ufaqs/what-is-the-difference-between-the-written-description-and-enablement-requirements-in-patent-law/

- Recent Pharmaceutical Patent Decisions in the United States – niscair, accessed August 5, 2025, http://op.niscair.res.in/index.php/JIPR/article/download/3293/92

- The Patent Trial and Appeal Board and Inter Partes Review – Congress.gov, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/R48016

- Patent Basics: Practice Tips for Achieving Success in Inter Partes Reviews, accessed August 5, 2025, https://ipwatchdog.com/2023/10/25/patent-basics-practice-tips-achieving-success-inter-partes-reviews/id=168632/

- Inter Partes Disputes | USPTO, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.uspto.gov/patents/laws/america-invents-act-aia/inter-partes-disputes

- Understanding Inter Partes Review in Patent Law – Barcelo, Harrison & Walker, LLP, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.patentlaw.us/understanding-inter-partes-review-in-patent-law/

- What is inter partes review and why does it matter? – PhRMA, accessed August 5, 2025, https://phrma.org/blog/what-is-inter-partes-review-and-why-does-it-matter

- 2024 Hatch-Waxman Year in Review | Womble Bond Dickinson, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.womblebonddickinson.com/us/insights/articles-and-briefings/2024-hatch-waxman-year-review

- Trial Statistics Trends at the PTAB: 2024 Edition | PTAB Law Blog, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.ptablaw.com/2025/01/06/trial-statistics-trends-at-the-ptab-2024-edition/

- Legislative Developments in Patents: Prospects for the PREVAIL …, accessed August 5, 2025, https://ipwatchdog.com/2025/01/02/legislative-developments-patents-prevail-restore-acts-pera-2025/id=184349/

- Outlook for 2025: How Trump and the USPTO Will Affect Life …, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.sternekessler.com/news-insights/insights/outlook-for-2025-how-trump-and-the-uspto-will-affect-life-sciences-ip-2/

- Understanding Patentability Requirements for Drug Inventions – PatentPC, accessed August 5, 2025, https://patentpc.com/blog/understanding-patentability-requirements-drug-inventions

- Searching for Patents and Prior Art | Institute for Translational Medicine and Therapeutics, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.itmat.upenn.edu/mtr-entsci-blog/searchingforpatentsandpriorart.html

- Prior art search and analysis for scientific IP strategies – CAS, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.cas.org/resources/cas-insights/prior-art-search-and-analysis-scientific-ip-strategies

- Performing a Basic Prior Art Search | Office of Technology Licensing, accessed August 5, 2025, https://otl.stanford.edu/performing-basic-prior-art-search

- Three things every patent analyst should know when searching prior art | CAS, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.cas.org/resources/article/three-things-every-patent-analyst-should-know-when-searching-prior-art

- Patenting Drugs Developed with Artificial Intelligence: Navigating …, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/patenting-drugs-developed-with-artificial-intelligence-navigating-the-legal-landscape/

- What is a patent challenge, and why is it common in generics?, accessed August 5, 2025, https://synapse.patsnap.com/article/what-is-a-patent-challenge-and-why-is-it-common-in-generics

- Finding Generic Drug Entry Opportunities in Emerging Markets …, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/generic-drug-entry-emerging-markets/

- 5 Pharma Powerhouses Facing Massive Patent Cliffs—And What …, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.biospace.com/business/5-pharma-powerhouses-facing-massive-patent-cliffs-and-what-theyre-doing-about-it

- Landmark Ruling Reshapes Pharmaceutical Patent Litigation …, accessed August 5, 2025, https://todaysgeneralcounsel.com/landmark-ruling-reshapes-pharmaceutical-patent-litigation/

- Noteworthy Hatch-Waxman Decisions From 2024 | Law Bulletins …, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.taftlaw.com/news-events/law-bulletins/noteworthy-hatch-waxman-decisions-from-2024-2/

- The Implications of AI-Assisted Drug Development on Patent …, accessed August 5, 2025, https://perspectives.bipc.com/post/102k8yy/the-implications-of-ai-assisted-drug-development-on-patent-challenges

- Life Sciences & Pharma IP Litigation 2025 – Global Practice Guides, accessed August 5, 2025, https://practiceguides.chambers.com/practice-guides/life-sciences-pharma-ip-litigation-2025