Introduction: Beyond the Blueprint

In the high-stakes, multi-billion-dollar world of pharmaceuticals, the Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) is far more than a regulatory hurdle; it is the central instrument of competitive strategy for the generic drug industry. To view the ANDA filing process as a mere administrative checklist is to fundamentally misunderstand its power. This is not simply about creating a “copy” of a brand-name drug; it is about strategically dismantling a monopoly, navigating a complex legal and scientific gauntlet, and ultimately, delivering affordable medicines to millions while capturing significant market share.1 The journey from identifying a target molecule to launching a generic product is a masterclass in calculated risk, scientific precision, and legal acumen.

The modern generic industry, a behemoth that now accounts for over 90% of all prescriptions filled in the United States, was forged in the legislative crucible of the 1984 Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act, more commonly known as the Hatch-Waxman Act.3 This landmark legislation created the ANDA pathway, allowing generic manufacturers to rely on the safety and efficacy data of an innovator’s product—the Reference Listed Drug (RLD)—thereby avoiding the prohibitively expensive and time-consuming process of conducting their own clinical trials.3

Yet, this “abbreviated” path is anything but simple. It is a significant undertaking fraught with financial risk. Under the Generic Drug User Fee Amendments (GDUFA), the cost to simply file an ANDA with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) stands at $252,453 and is projected to climb to $321,920 in 2025.9 A failure to meet the FDA’s stringent completeness requirements can result in a “Refuse to Receive” decision, forfeiting 25% of that substantial fee immediately. This financial barrier serves as a powerful strategic filter, ensuring that every ANDA filed is not a speculative whim but a calculated corporate investment demanding a clear and compelling return. It elevates the entire process from a regulatory task to a critical capital allocation decision, forcing a level of discipline and strategic foresight that defines the industry’s most successful players. This report is a playbook for that discipline—a deep dive into the strategies that transform the ANDA from a regulatory submission into a strategic weapon.

The Arena and the Rulebook: Deconstructing the Hatch-Waxman Framework

To win the game, one must first master the rules. The Hatch-Waxman Act is the foundational text governing the relationship between brand and generic manufacturers. It is a grand legislative compromise, meticulously designed to balance two competing, yet equally vital, public interests: fostering groundbreaking pharmaceutical innovation through robust intellectual property protection and promoting widespread access to affordable medicines through vigorous generic competition.3 Understanding the delicate equilibrium it created is the first step toward crafting a winning ANDA strategy.

A Tale of Two Interests: The Grand Compromise of 1984

Before 1984, the generic industry was nascent and hamstrung. Generic manufacturers faced the same monumental task as innovators: conducting full clinical trials to prove safety and efficacy, a duplicative and economically unviable proposition for drugs whose patents were about to expire.3 The Hatch-Waxman Act revolutionized this landscape by creating a symbiotic framework of incentives and pathways.

For the generic industry, the Act provided two transformative tools. First, it established the modern ANDA pathway under Section 505(j) of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic (FD&C) Act, the regulatory superhighway for generic approvals.3 Second, and just as critically, it created a statutory “safe harbor” under 35 U.S.C. §271(e)(1).10 This provision shields generic companies from patent infringement lawsuits for activities “reasonably related to the development and submission of information” to the FDA. This safe harbor is not merely a legal technicality; it is the starting gun for the generic race. It allows a generic manufacturer to begin formulation, development, and bioequivalence testing work long before the brand’s patents expire. Without it, any such work would constitute infringement, effectively handing brand companies a de facto patent term extension as generics would be forced to wait until after patent expiry to even begin their multi-year development process. The safe harbor is the critical enabler of timely generic competition and the legal bedrock upon which the entire high-stakes strategy of pre-expiry patent challenges is built.

For the brand-name, innovator industry, the Act offered its own set of valuable concessions. It introduced mechanisms for extending a patent’s term to compensate for the time lost during the lengthy FDA review process for a new drug.12 Furthermore, it codified various periods of regulatory exclusivity, which are distinct from patent protection. These exclusivities, such as the five-year New Chemical Entity (NCE) exclusivity for drugs containing a never-before-approved active moiety, provide a guaranteed period of market protection, barring the FDA from even accepting an ANDA for a set time.3 This dual-sided structure created the dynamic tension that defines the industry today: a system where brands are incentivized to innovate and generics are incentivized to challenge.

The Central Intelligence Hub: The FDA’s Orange Book

If the Hatch-Waxman Act is the rulebook, the FDA’s publication Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations—universally known as the Orange Book—is the official battlefield map.10 It is the central public ledger that links the world of drug approvals with the world of patent law, and mastering its nuances is a non-negotiable prerequisite for any serious generic strategist.15

The Orange Book serves as a comprehensive database of all FDA-approved drugs, their designated therapeutic equivalence ratings, and, most importantly for strategic purposes, the patents and regulatory exclusivities that protect them.15 Under the Act, brand manufacturers are required to submit to the FDA a list of all patents that they believe have a claim covering their drug product or an approved method of using it.10 These patents, along with their expiration dates and specific “use codes” describing what they cover, are then published in the Orange Book.

However, a critical feature of this system—and a source of immense strategic opportunity for generics—is the FDA’s role. The agency acts merely as a ministerial record-keeper. It does not conduct a substantive review of the patents submitted for listing; it does not verify their validity, their enforceability, or whether they truly cover the drug in question.12 This administrative posture creates a powerful incentive for brand companies to engage in a strategy known as creating a “patent thicket”—listing numerous patents, some strong and some weak, in an effort to create a formidable-looking fortress of IP that might deter potential challengers.18

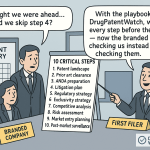

An unsophisticated generic firm might see a long list of patents in the Orange Book and abandon the project. A savvy strategist, however, sees an opportunity. They understand that the Orange Book is not a definitive statement of a drug’s patent protection but rather the brand’s assertion of it. The core of a sophisticated pre-filing strategy, therefore, is not simply to read the Orange Book but to deconstruct it. It involves a rigorous, independent patent landscape analysis to vet every listed patent, distinguishing the foundational “load-bearing walls”—like a strong composition of matter patent—from the “drywall”—weaker or narrower patents covering specific formulations, crystalline forms, or methods of use that may be more susceptible to a validity or non-infringement challenge. This deep-dive analysis, often powered by specialized business intelligence platforms like DrugPatentWatch which aggregate and analyze this complex data, is the essential first step in identifying the weak links in a brand’s armor and formulating a targeted Paragraph IV challenge.

Mastering the Fundamentals: Anatomy of a Winning ANDA Submission

Before a generic company can engage in the high-stakes legal chess match of a patent challenge, it must first prove its scientific and manufacturing prowess to the FDA. The ANDA dossier is a testament to a company’s ability to produce a safe, effective, and high-quality therapeutic equivalent to the RLD. A flaw in the scientific foundation can cause an application to be delayed or rejected long before any patent considerations come into play. A winning strategy, therefore, begins with an unwavering commitment to excellence in the two scientific cornerstones of the ANDA: Chemistry, Manufacturing, and Controls (CMC) and Bioequivalence (BE).

The Scientific Cornerstones: CMC and Bioequivalence

These two sections form the heart of the ANDA submission, providing the FDA with the evidence it needs to be confident that the generic product is a true therapeutic substitute for the brand-name drug.

Chemistry, Manufacturing, and Controls (CMC): The Product’s Blueprint

The CMC section is the technical blueprint of the generic drug product. It is a comprehensive and meticulously detailed dossier that describes the drug’s composition, the entire manufacturing process, the quality control measures in place, and the data supporting the product’s stability over its shelf life.5 The FDA’s review of this section, often guided by its Question-Based Review (QbR) framework, is designed to ensure that the applicant can consistently produce a high-quality product that meets all specifications for identity, strength, purity, and quality.20

Every aspect of production is scrutinized, from the synthesis of the Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) to the final packaging of the finished dosage form. The applicant must demonstrate strict adherence to Current Good Manufacturing Practices (cGMP), the set of regulations that govern pharmaceutical manufacturing.5 A critical and often overlooked strategic element is the selection of manufacturing partners. The ANDA must identify every facility involved in the manufacturing and testing process, and these sites are subject to pre-approval inspections by the FDA. Choosing a contract manufacturing organization (CMO) with a stellar FDA audit history is not just an operational choice; it is a crucial strategic decision that can prevent catastrophic delays. A negative inspection finding at a key facility can halt an application in its tracks, regardless of the strength of the rest of the submission.9

Bioequivalence (BE): The Proof of Sameness

Bioequivalence is the scientific bedrock of the entire generic drug approval system. Because the ANDA applicant relies on the brand’s clinical data for safety and efficacy, it must prove that its product behaves identically to the brand’s product in the human body. This is the essence of bioequivalence: demonstrating that the generic drug delivers the same amount of the active ingredient into a patient’s bloodstream over the same period of time as the RLD.1

This proof is typically generated through pharmacokinetic (PK) studies conducted in a small cohort of healthy volunteers. These subjects are given both the generic (test) product and the brand (reference) product in a crossover design, and blood samples are drawn at multiple time points to measure the concentration of the drug in their plasma. The key PK parameters measured are the maximum concentration (Cmax) and the total drug exposure over time, represented by the area under the concentration-time curve (AUC).7 For the generic to be deemed bioequivalent, the 90% confidence interval for the geometric mean ratio (Test/Reference) of both

Cmax and AUC must fall entirely within the acceptance range of 80.00% to 125.00%.7

A pivotal policy shift by the FDA has fundamentally altered the strategic calculus of BE testing. The agency now requires applicants to submit the results of all bioequivalence studies conducted on a given formulation, not just the successful, or “passing,” ones.23 In the past, a company could conduct multiple studies, tweaking the formulation until it achieved a passing result, and submit only the final, successful study. This practice, however, could mask underlying formulation inconsistencies or “borderline” performance. The new requirement for full transparency means that a company’s entire development history, including any failed attempts, is now part of the regulatory record. A single “failed” BE study, even if followed by a successful one, can raise questions for FDA reviewers and must be thoroughly justified. This forces a much more rigorous and conservative approach to formulation development, shifting the strategy from “test until you pass” to a “right-the-first-time” philosophy grounded in Quality by Design (QbD) principles to avoid creating a problematic paper trail that could complicate and delay the approval narrative.26

The Regulatory Gauntlet: Navigating the FDA Review Process

Even a scientifically flawless ANDA can be derailed by procedural missteps or a poorly organized submission. Navigating the FDA’s multi-stage review process requires precision, responsiveness, and a proactive mindset. The entire process is now digital, with all applications submitted in the electronic Common Technical Document (eCTD) format through the FDA’s Electronic Submission Gateway (ESG).5

The journey begins with the FDA’s Division of Filing Review, which conducts an initial assessment to ensure the application is “substantially complete” and can be accepted for a full, substantive review.1 An application that is missing critical components or is poorly organized can be issued a Refuse-to-Receive (RTR) letter, a costly setback that sends the applicant back to the drawing board.

Once an ANDA is accepted for filing, the formal review clock begins, and the dossier is dissected by various specialized teams within the Office of Generic Drugs (OGD), including reviewers for CMC, bioequivalence, and labeling. During this substantive review, the agency may issue Information Requests (IRs) or Discipline Review Letters (DRLs) seeking clarification or additional data on specific aspects of the application.27 Minor issues can often be resolved through this back-and-forth communication.

However, if significant deficiencies are identified across one or more disciplines, the FDA will issue a Complete Response Letter (CRL).5 A CRL is not a final rejection, but it halts the review cycle. It provides a comprehensive list of all deficiencies that the applicant must address before the application can be reconsidered. The applicant generally has one year to prepare and submit a complete response to the CRL.27 Each review cycle adds significant time to the approval process, delaying market entry and eroding potential revenue.

The key to successfully navigating this gauntlet is to view the review not as a passive submission but as an active dialogue. Responsiveness is paramount; delays in answering FDA queries directly translate to longer approval timelines.9 The most effective strategy is proactive. For complex generics, such as drug-device combination products, applicants are encouraged to request Pre-ANDA meetings with the agency to align on development and data requirements before the application is even filed.14 The goal is to build a robust, well-organized, and easily navigable eCTD dossier that anticipates reviewers’ questions and provides clear, comprehensive answers upfront. The return on this upfront investment in quality and clarity is a smoother, more predictable review cycle—a critical advantage in the race to market.

The Four Doors to Market Entry: Strategic Patent Certifications

At the heart of every ANDA submission lies a single, pivotal strategic decision. For every patent listed in the Orange Book as protecting the RLD, the generic applicant must make a formal declaration, known as a patent certification. This is not a mere formality; it is a legally binding statement that dictates the regulatory pathway, the timeline to market, the risk of litigation, and the ultimate commercial potential of the generic product. There are four possible certifications, each representing a distinct door to the market with its own unique set of consequences.29

Choosing Your Path: An Overview of the Four Certifications

The choice of certification is a direct reflection of the generic company’s assessment of the brand’s patent landscape and its own appetite for risk.

- Paragraph I (PI) Certification: This is the most straightforward path. A PI certification states that, to the best of the applicant’s knowledge, no patent information for the RLD has been submitted to the FDA and listed in the Orange Book.31 If the scientific and manufacturing data are in order, an ANDA with a PI certification can be approved by the FDA without patent-related delays.

- Paragraph II (PII) Certification: This path is taken when patents for the RLD were once listed in the Orange Book but have now expired.31 Similar to a PI certification, this allows for an unimpeded path to approval once the scientific review is complete.

- Paragraph III (PIII) Certification: This is a strategy of patience. A PIII certification states that there is an unexpired patent listed in the Orange Book and that the generic applicant will wait to market its product until that patent expires on its stated date.31 The FDA can fully review and grant approval to the ANDA, but the approval will not become effective until the date of patent expiry. This is a low-risk, no-litigation pathway, but it concedes the entire patent term to the brand company.

- Paragraph IV (PIV) Certification: This is the path of the challenger. A PIV certification is a bold declaration that a patent listed in the Orange Book is invalid, unenforceable, or will not be infringed by the manufacture, use, or sale of the generic drug product.31 This certification does not seek to wait for the patent to expire; it seeks to neutralize it. It is an aggressive, high-risk strategy that almost guarantees a multi-million-dollar patent infringement lawsuit from the brand company. It is also, however, the only pathway to potentially launch a generic product years before a patent’s natural expiration and the only route to securing the coveted 180-day market exclusivity period for being the “first-to-file.”

The strategic implications of this choice are profound, as summarized in the table below.

| Feature | Paragraph I (PI) | Paragraph II (PII) | Paragraph III (PIII) | Paragraph IV (PIV) |

| Meaning | No patents are listed for the RLD. | The listed patent(s) have expired. | The generic will launch after the listed patent(s) expire. | The listed patent(s) are invalid, unenforceable, or not infringed. |

| Implied Action | Proceed directly to market upon FDA approval. | Proceed directly to market upon FDA approval. | Wait for patent expiration to launch. | Challenge the brand’s patent(s), likely through litigation. |

| Litigation Risk | None | None | None | Extremely High |

| Time to Market | Fastest (limited only by FDA review). | Fastest (limited only by FDA review). | Slowest (tied to patent expiry date). | Potentially fast (pre-expiry), but subject to 30-month stay and litigation outcome. |

| Potential Reward | Standard generic profits in an unpatented market. | Standard generic profits in a post-patent market. | Standard generic profits, but with a delayed start. | Highest potential reward: early market entry and possible 180-day exclusivity. |

This decision matrix makes the trade-offs clear. PI and PII are straightforward, low-risk options for drugs with no or expired patent protection. PIII is a conservative, “wait-and-see” approach. PIV is the high-stakes gambit, a strategic decision to invest heavily in litigation with the goal of unlocking a blockbuster market ahead of the competition.

The High-Stakes Gambit: Mastering the Paragraph IV Challenge

The Paragraph IV (PIV) certification is the engine of the modern generic drug industry. It is the legal mechanism that transforms a generic manufacturer from a passive follower, waiting for patents to expire, into an active challenger, capable of disrupting a brand’s monopoly years ahead of schedule. It is a strategy defined by immense risk, but also by the potential for extraordinary reward. Understanding the mechanics, incentives, and strategic nuances of the PIV pathway is essential for any company seeking to compete at the highest level.

The PIV Imperative: Why Challenge a Patent?

The motivation behind a PIV challenge is purely economic. Brand-name drugs, particularly “blockbuster” products with billions in annual sales, are protected by a period of monopoly pricing granted by their patents. A successful PIV challenge that invalidates a key patent or proves non-infringement can open that market to generic competition years early. The resulting price drop generates massive savings for the healthcare system and consumers—one study on the hypertension market found that PIV-driven generic entry created nearly $100 billion in additional consumer surplus over a decade.33 For the successful generic challenger, it unlocks a revenue opportunity that can be worth hundreds of millions, or even billions, of dollars.32

While the prospect of facing off against a well-funded brand legal team is daunting, the odds are often more favorable than they might appear. Generic challengers have historically demonstrated a high rate of success in these litigations. One analysis found that generic companies prevailed in ANDA litigation roughly 75% of the time between 1992 and 2002 35, while a more recent report cited a 76% success rate for PIV challengers, concluding that the potential payoff is often worth the risk.32

The single greatest incentive for undertaking this risky and expensive endeavor is the prize established by the Hatch-Waxman Act: a 180-day period of marketing exclusivity for the first generic company to file a successful PIV challenge.4 This exclusivity is the holy grail of generic strategy.

The First-to-File (FTF) Race: Speed, Precision, and the Winner’s Curse

The 180-day exclusivity period is a powerful reward. For six months, the FDA is barred from approving any subsequent ANDAs for the same drug product. This effectively creates a duopoly between the brand company and the “first-to-file” (FTF) generic, allowing the FTF to capture significant market share at a price point well above what would be possible in a fully competitive multi-generic market. This six-month window is often the most profitable period in a generic drug’s lifecycle, with some estimates suggesting that a company can earn 60-80% of its total profit on a product during this time.36 The economic value is immense; in 2020, generics launched with 180-day exclusivity were credited with saving the U.S. healthcare system nearly $20 billion.4

The importance of 180-day exclusivity cannot be overstated. Because it is the only incentive for generic companies to challenge brand patents, it is perhaps the most significant driver of competition – and lower prices – within the pharmaceutical industry. 4

This enormous prize triggers a frantic race among generic competitors. To win, a company must be the first to submit an ANDA containing a PIV certification that the FDA deems “substantially complete” upon receipt.32 This creates a fundamental strategic tension between speed and precision. Companies invest heavily to accelerate their R&D and regulatory affairs timelines to be the first to the FDA’s doorstep.4 However, rushing the process and submitting an incomplete or flawed application can be disastrous. If the FDA issues an RTR because the application is not “substantially complete”—for instance, due to missing data or even a failure to pay the user fee on time—the company loses its original submission date. A competitor who filed a day later, but with a complete application, would then be crowned the first filer.39 This “winner’s curse” means that millions of dollars in potential revenue can be lost due to a single clerical error. The winning FTF strategy is therefore not just about being fast, but about being

fast and right. It demands an integrated project management approach where the R&D, manufacturing, regulatory, and legal teams work in lockstep to prepare a “litigation-ready” ANDA dossier that is both scientifically sound and regulatorily flawless from the moment it is submitted.

The Mechanics of the Challenge: From Notice Letter to Litigation Stay

Filing a PIV ANDA initiates a tightly choreographed legal and regulatory dance with strict timelines that every participant must follow.

- The Notice Letter: The process officially begins after the generic company files its ANDA and the FDA issues a confirmation that the application is sufficiently complete to be reviewed. Within 20 days of receiving this confirmation, the ANDA filer must send a formal “notice letter” to the brand company (the NDA holder) and the owner of the patent being challenged.32 This is no simple notification; it is a detailed legal document that must lay out the factual and legal basis for the generic’s assertion that the patent is invalid, unenforceable, or not infringed. The quality of this letter is critical, as it forms the initial basis of the legal dispute.

- The 45-Day Countdown: Upon receiving the notice letter, the clock starts ticking for the brand company. It has a 45-day window to decide whether to sue the ANDA filer for patent infringement.32

- The 30-Month Stay: The brand’s decision in this 45-day window has profound regulatory consequences. If the brand company files a lawsuit within that period, it automatically triggers a 30-month stay of FDA approval for the ANDA.13 This provision is one of the most powerful tools for brand companies under Hatch-Waxman. It effectively grants them an automatic preliminary injunction, preventing the generic from coming to market for up to two and a half years while the patent litigation plays out in court. This stay provides a significant period of continued monopoly revenue, regardless of the ultimate merits of the patent case. If the brand fails to sue within the 45-day window, the FDA can proceed with reviewing and approving the ANDA without this statutory delay.

This sequence—the PIV filing, the notice letter, and the potential for an automatic 30-month stay—forms the procedural backbone of all Hatch-Waxman litigation.

Navigating the Minefield: ANDA Litigation and Risk Management

The filing of a PIV certification and the subsequent infringement lawsuit by the brand company mark the beginning of a complex, expensive, and high-stakes legal battle. ANDA litigation is a highly specialized field of law, a unique intersection of patent law, FDA regulatory law, and antitrust principles. Success requires not only a deep understanding of the science and the law but also a sophisticated strategic playbook.

The Brand and Generic Playbooks

Over decades of Hatch-Waxman litigation, distinct strategic approaches have emerged for both plaintiffs (brand companies) and defendants (generic challengers).

Brand Company Tactics: The primary goal for the brand is to delay generic entry for as long as possible to maximize the revenue from their patented product. Their strategies often include:

- Building a Patent Thicket: As discussed, this involves obtaining and listing multiple patents covering various aspects of the drug—different formulations, crystalline forms (polymorphs), methods of use, and even metabolites—in the Orange Book. This forces a generic challenger to navigate a more complex IP landscape and increases the cost and difficulty of a PIV challenge.18

- Aggressive Litigation Posture: Brand companies often assert a large number of patents and claims at the outset of litigation. This forces the generic defendant to expend significant resources on discovery and analysis for all asserted claims, even those the brand may not ultimately pursue at trial. This can be a tactic to drain the generic’s resources and pressure them into a more favorable settlement.42

- “Product Hopping”: A controversial but sometimes used strategy involves the brand company introducing a new, slightly modified version of the drug (e.g., an extended-release formulation) that is covered by new patents. They then work to switch patients from the old version to the new one before the patents on the original product expire. This can diminish the market opportunity for the generic version of the original drug when it finally launches.32

Generic Company Tactics: The generic’s goal is to invalidate or design around the brand’s patents as efficiently as possible to secure early market entry. Their strategies include:

- Targeted Challenges: A thorough pre-filing patent analysis allows the generic to focus its PIV challenge on the brand’s weakest patents. Composition of matter patents are typically the strongest and hardest to defeat, so generics often focus their challenges on more vulnerable secondary patents, such as those covering specific methods of use or formulations.43

- Standard Invalidity Defenses: The core of the generic’s legal case typically revolves around proving the patent is invalid based on established patent law principles, such as anticipation (the invention was not new) or, more commonly, obviousness (the invention would have been obvious to a person of ordinary skill in the art at the time).44

- Leveraging the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB): The 2011 America Invents Act created a new venue for challenging patent validity: the PTAB at the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. A generic company can file an Inter Partes Review (IPR) petition to challenge a patent’s validity in a parallel administrative proceeding. The PTAB offers several potential advantages over district court: the proceedings are typically faster and less expensive, the cases are heard by technically expert administrative patent judges, and the burden of proof for invalidating a patent is lower (“preponderance of the evidence” vs. “clear and convincing evidence” in district court). A successful IPR can invalidate the patent, effectively ending the district court litigation. This has created a powerful “second front” in ANDA disputes, forcing the brand to defend its patents in multiple venues simultaneously and increasing the generic’s leverage.46

The “At-Risk” Launch: A Calculated Gamble

Perhaps the most dramatic and high-stakes decision a generic company can make is the “at-risk” launch. This occurs when a generic manufacturer receives final FDA approval (for example, after the 30-month stay expires) but the underlying patent litigation is still ongoing, perhaps pending an appeal. The company then faces a choice: wait for the final resolution of all appeals, or launch the product immediately “at risk”.48

The upside is enormous: immediate market entry and the chance to capture hundreds of millions in revenue while the appeal proceeds. The downside is potentially catastrophic. If the generic company launches and ultimately loses the appeal—meaning the patent is found to be valid and infringed—it can be liable for massive damages. These damages are typically calculated based on the brand’s lost profits during the at-risk period and can even be tripled if the infringement is found to be willful.49

The history of at-risk launches is littered with both spectacular successes and cautionary tales:

- Case Study: Protonix (pantoprazole): In one of the most famous examples of the risks involved, Teva Pharmaceuticals and Sun Pharmaceutical launched generic versions of the blockbuster acid reflux drug Protonix at-risk. They ultimately lost their patent case on appeal and were ordered to pay the brand manufacturer, Pfizer, a staggering $2.15 billion in damages. The case serves as a stark reminder of the immense financial exposure an at-risk launch entails.50

- Case Study: Tarka (trandolapril/verapamil): In a contrasting example, Glenmark Pharmaceuticals launched a generic version of the blood pressure medication Tarka at-risk. While they also ultimately lost the patent suit, the damages and settlement were far more modest, reflecting the smaller market size of the drug. This illustrates that the risk/reward calculation is highly specific to each product’s commercial potential.50

The decision to launch at-risk is therefore a sophisticated financial modeling problem, not merely a legal one. It requires a rigorous, data-driven analysis that weighs the potential profits from an early launch against the potential damages, with both figures discounted by the company’s perceived probability of winning the case on appeal. A key inflection point in this calculation is the district court’s decision. A trial court victory for the generic dramatically shifts the odds in its favor. While an appeal is still possible, the probability of a reversal is statistically lower. As a result, empirical data shows that for first-filer generics that have not already settled, a favorable district court decision combined with FDA approval makes an at-risk launch almost a certainty.48 Brand companies must understand this dynamic; after a loss at trial, an at-risk launch by the generic is not a remote possibility but a near-inevitability, a fact that should heavily influence their post-verdict settlement strategy.

The Art of the Deal: Settlement Dynamics and Authorized Generics

Given the immense cost and uncertainty of litigation, the vast majority of ANDA disputes do not go to a final verdict. Instead, they are resolved through a negotiated settlement agreement. These settlements typically involve the generic company agreeing to delay its market entry until a specific, negotiated date—a date that is later than it would get if it won the lawsuit, but years earlier than the patent’s natural expiration date.35

However, some settlements have drawn intense antitrust scrutiny from the Federal Trade Commission (FTC). These are the so-called “pay-for-delay” or “reverse payment” agreements, in which the brand company not only agrees to an early entry date for the generic but also provides a payment or other form of value transfer to the generic company in exchange for the delayed entry.35 The FTC argues that these settlements are anti-competitive, costing consumers and the healthcare system an estimated $3.5 billion per year by keeping lower-priced generics off the market.52 The Supreme Court’s landmark 2013 decision in

FTC v. Actavis ruled that such payments could be subject to antitrust challenge, opening the door to ongoing legal battles over the practice.

A crucial and often misunderstood element in these negotiations is the concept of the “Authorized Generic” (AG). An AG is a generic version of a drug that is marketed by the brand company itself or with its permission. It is the exact same drug as the brand product, sold under the brand’s approved NDA, but marketed as a generic.53 Because it is not approved under an ANDA, an AG is not blocked by the first-filer’s 180-day exclusivity. This means the brand company can launch its own AG to compete directly with the first-filer generic during that lucrative six-month period.54

The competitive impact of an AG is substantial. An FTC report found that the presence of an AG during the 180-day exclusivity period reduces the first-filer generic’s revenues by an average of 40% to 52%.54 This makes the brand’s promise

not to launch an AG an incredibly valuable, non-cash bargaining chip in settlement negotiations. Many modern settlements include a “no-AG” clause, which effectively preserves the first-filer’s monopoly during the exclusivity period in exchange for a later entry date.52 For generic strategists, understanding the threat of an AG and leveraging a “no-AG” commitment is a critical component of the settlement endgame.

Choosing Your Battles: Intelligent Product Selection and Pathway Strategy

The most sophisticated and consistently successful generic companies understand that winning in the marketplace begins long before an ANDA is ever filed. It begins with a disciplined and data-driven process of product selection. In a world of limited R&D resources and high filing fees, choosing which drugs to pursue is arguably the most critical strategic decision a generic company makes. This process involves not only identifying commercially attractive targets but also meticulously analyzing the patent and regulatory landscape to find viable paths to market.

Intelligence-Led Targeting: Finding the Right Opportunity

A winning portfolio strategy is built on a foundation of robust competitive intelligence. The process starts with the basics: identifying drugs with high sales volumes whose key patents and regulatory exclusivities are set to expire in the coming years.38 But this is merely the first step. A comprehensive feasibility study is required to truly vet a potential target. This analysis must go deeper, evaluating factors such as:

- Market Potential: What is the true size of the generic opportunity? How many other generics are likely to enter? Will the brand launch an authorized generic? What is the projected price erosion curve?

- Technical Feasibility: Can the drug be successfully reverse-engineered? Are there formulation or manufacturing challenges (e.g., complex APIs, sterile injectables) that could increase development costs and timelines?

- Patent Landscape: A deep dive into the Orange Book and beyond is essential. What is the quality of the listed patents? Are there obvious weaknesses? What was the outcome of prior litigation involving similar patents or technologies?.38

This level of analysis is impossible without specialized tools. Competitive intelligence platforms like DrugPatentWatch are indispensable for modern generic strategists. These platforms aggregate and synthesize vast amounts of disparate data—Orange Book listings, patent filings and litigation records from the USPTO, FDA regulatory updates, and competitor pipeline information—into a single, actionable dashboard.56 By leveraging such tools, companies can move beyond simple patent expiration dates and conduct a holistic assessment of an opportunity. They can identify crowded development pipelines to avoid, spot drugs with surprisingly weak patent protection, and uncover niche opportunities that others may have overlooked. This intelligence-led approach allows for the strategic allocation of resources to projects with the highest probability of success and the greatest potential return on investment.

The Strategic Fork in the Road: ANDA (505(j)) vs. 505(b)(2)

A critical early decision in the development process is choosing the correct FDA regulatory pathway. While the traditional ANDA pathway, governed by section 505(j) of the FD&C Act, is the route for true generics—products that are identical copies of the RLD—it is not the only abbreviated pathway available. For products that are similar to, but intentionally different from, an existing approved drug, the 505(b)(2) pathway offers a flexible, “hybrid” alternative.5

The ANDA (505(j)) pathway is appropriate only when the proposed generic product has the same active ingredient, dosage form, strength, route of administration, and conditions of use as the RLD. The application’s primary burden is to demonstrate bioequivalence.5

The 505(b)(2) pathway, in contrast, is designed for products that represent some modification of a previously approved drug. Examples include:

- A new dosage form (e.g., changing a tablet to a liquid suspension).

- A new strength or dosing regimen.

- A different formulation with new inactive ingredients (excipients).

- A new indication (repurposing the drug for a new use).

- A change in the active ingredient, such as using a different salt or ester.62

Like an ANDA, a 505(b)(2) application can rely on the FDA’s prior findings of safety and efficacy for the RLD, avoiding the need for a full slate of new clinical trials. However, the applicant must conduct its own “bridging studies”—which can range from simple BE studies to more complex clinical trials—to establish the safety and efficacy of the specific changes made to the product.64 While more expensive and time-consuming than a standard ANDA, the 505(b)(2) pathway offers a significant advantage: a product approved via this route can often qualify for its own period of regulatory exclusivity (typically three years), a benefit not available to traditional generics.63

This pathway can be used as a powerful strategic tool, as illustrated by a classic case study involving the blockbuster blood pressure drug Norvasc® (amlodipine besylate).

- Case Study: Dr. Reddy’s vs. Norvasc®: When the first generic company filed a PIV ANDA for amlodipine besylate, it became eligible for the 180-day exclusivity, which would have blocked all other ANDA filers. Seeing this barrier, another generic competitor, Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories, pursued a different strategy. Instead of filing an ANDA for the same besylate salt, they developed a version with a different salt—amlodipine maleate—and filed a 505(b)(2) application. Because their product was not an ANDA, it was not subject to the first-filer’s 180-day exclusivity. This clever regulatory maneuver allowed Dr. Reddy’s to circumvent a key competitive barrier and potentially enter the market alongside the first ANDA filer, gaining a significant market advantage.66

The choice between these two pathways is a fundamental strategic decision, with each offering a different balance of risk, cost, time, and reward.

| Feature | ANDA (505(j)) | 505(b)(2) NDA |

| Product Type | True generic; a duplicate of the RLD. | “Hybrid” or modified drug; differs from the RLD in some way. |

| Relation to RLD | Must be identical in API, dosage, strength, route, etc. | Can have different API (salt/ester), dosage, strength, formulation, indication. |

| Key Data Requirement | Bioequivalence to the RLD. | Bioequivalence plus “bridging studies” to support the changes. |

| Clinical Studies | None required (relies entirely on RLD’s safety/efficacy data). | May require new, limited clinical studies to support the modification. |

| Market Exclusivity | Only the 180-day FTF exclusivity is possible. | Can qualify for 3, 5, or 7 years of its own regulatory exclusivity. |

| Development Cost/Time | Lower cost, faster timeline. | Higher cost, longer timeline than ANDA, but less than a full NDA. |

| Strategic Use Case | Competing in the traditional generic market post-patent expiry. | Creating a differentiated product, circumventing ANDA exclusivities, or improving on an existing drug. |

The Shifting Landscape: Future-Proofing Your ANDA Strategy

The strategic environment for generic pharmaceuticals is in a constant state of flux. Regulatory policies evolve, new legislation reshapes economic incentives, and litigation trends shift. The strategies that guaranteed success five years ago may be obsolete today. Companies that thrive in this dynamic landscape are those that are not only masters of the current rules but are also adept at anticipating and adapting to future changes.

Adapting to New Realities: Recent FDA Policies and Legislative Changes

Staying ahead requires constant vigilance of the regulatory and legislative environment. The FDA, for its part, is continually refining its processes. The agency periodically updates its Manual of Policies and Procedures (MAPP), which governs how ANDAs are reviewed. A recent update, for example, revised the detailed filing checklist used by reviewers to determine if an application is “substantially complete,” underscoring the need for applicants to stay current with the agency’s expectations.67 Furthermore, each reauthorization of the Generic Drug User Fee Amendments (GDUFA) brings changes. The most recent iteration, GDUFA III, introduced new performance goals and refined the classification system for amendments submitted to pending applications, affecting review timelines and strategic planning.68

Savvy companies can also leverage certain FDA policies to their advantage. The agency has established programs to prioritize the review of ANDAs that are deemed critical to public health. These include applications for “first generics” (the first generic version of a brand drug), drugs that are in shortage, and certain public health emergencies.70 Qualifying for a priority review can significantly shorten the approval timeline, providing a powerful competitive edge.

On the legislative front, the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) of 2022 represents arguably the most significant paradigm shift for the pharmaceutical industry in decades. A key provision of the IRA empowers the federal government to “negotiate” (effectively, set) the price for certain high-expenditure drugs covered by Medicare.71 This has profound and potentially disruptive implications for the traditional generic business model.

Historically, the most attractive targets for PIV challenges have been blockbuster drugs with billions in sales and high prices, as these offered the greatest potential return during the 180-day exclusivity period. The IRA, however, targets these very same drugs for price setting. This means that a generic company might spend years and millions of dollars developing a product and winning a patent case, only to find that the brand price it will compete against has been artificially lowered by government action. A lower brand price directly translates to a lower generic price, which can dramatically reduce the profitability of market entry and severely diminish the economic value of the 180-day exclusivity incentive.71

This new reality forces a fundamental reassessment of product selection strategy. The “biggest prize” in terms of brand sales may no longer be the most profitable target for a generic challenger. The industry must now factor in the probability of a drug being selected for price negotiation when modeling the potential ROI of a PIV challenge. This may lead to a strategic pivot towards:

- Targeting drugs that fall outside the IRA’s selection criteria.

- Focusing more on complex or “value-added” generics via the 505(b)(2) pathway to create products that are differentiated from the brand and potentially less susceptible to direct price linkage.

- Accepting lower margins on blockbuster drugs, which could make some high-risk, high-cost PIV challenges economically non-viable.

The full impact of the IRA will unfold over the coming years, but it is clear that it has introduced a new and powerful variable into the strategic equation for every generic drug manufacturer.

Conclusion: The Integrated Strategy for Sustainable Success

The path to a successful generic drug launch is not a simple, linear progression. It is a complex, interwoven tapestry of scientific development, regulatory navigation, legal warfare, and commercial foresight. A winning ANDA strategy cannot be formulated in a silo. A brilliant legal theory for a PIV challenge is worthless if the R&D team cannot develop a bioequivalent and stable formulation. A scientifically perfect product can be fatally delayed by a sloppy regulatory submission. A hard-won, first-to-file exclusivity can see its value slashed by the unexpected launch of an authorized generic or the implementation of new government pricing policies.

Sustainable success in the generic pharmaceutical industry belongs to those organizations that can master this integration. It requires breaking down the traditional walls between departments and fostering a culture of cross-functional collaboration. The legal team’s patent analysis must inform the R&D team’s formulation strategy from day one. The regulatory affairs team’s understanding of FDA guidance must shape the project timelines and risk assessments used by the business development team. Commercial intelligence on market dynamics must feed back into the portfolio selection process.

The ANDA is the ultimate expression of this integrated strategy. A well-crafted submission is more than just a collection of data; it is a narrative that speaks to scientific excellence, regulatory compliance, and a clear-eyed understanding of the competitive landscape. By mastering the intricate rules of the Hatch-Waxman Act, leveraging patent intelligence to choose battles wisely, executing with scientific and regulatory precision, and adapting to an ever-changing market, generic manufacturers can continue to fulfill their dual mission: achieving commercial success while increasing access to affordable, life-saving medicines.

Key Takeaways

- ANDA Filing is a Strategic Investment: The high GDUFA user fees transform the ANDA from a simple regulatory filing into a significant capital allocation decision that demands rigorous pre-filing due diligence and a clear ROI strategy.

- Master the Hatch-Waxman Framework: Understanding the foundational compromise of the Hatch-Waxman Act—including the “safe harbor” for development and the central role of the Orange Book—is non-negotiable for crafting effective strategies.

- The Orange Book is a Map, Not Gospel: The FDA’s administrative role in Orange Book listings creates opportunities. The best strategies are born from critically analyzing and vetting listed patents to identify weak links, rather than being deterred by a “patent thicket.”

- Scientific Precision is Paramount: Flawless execution of CMC and Bioequivalence sections is the foundation of any successful ANDA. The requirement to submit all BE studies necessitates a “right-the-first-time” approach to formulation development.

- The Paragraph IV Challenge is the Engine of Early Entry: The PIV certification, while guaranteeing litigation, is the primary tool for pre-expiry market entry. Its main incentive is the highly lucrative 180-day first-to-file (FTF) exclusivity.

- The FTF Race is About Speed and Precision: Winning the 180-day exclusivity requires being the first to file a “substantially complete” ANDA. A rushed, sloppy application can result in a Refuse-to-Receive decision, forfeiting the prize to a more careful competitor.

- Litigation is a Multi-Front War: Modern ANDA litigation strategy must consider both district court and the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB). Using the PTAB’s Inter Partes Review (IPR) process can be a highly effective parallel strategy for invalidating patents.

- Know Your Pathways (505(j) vs. 505(b)(2)): Choosing the correct regulatory pathway is a critical early decision. The 505(b)(2) pathway offers a strategic alternative for modified drugs, allowing companies to create differentiated products and potentially circumvent ANDA-specific barriers like FTF exclusivity.

- Adapt to the Evolving Landscape: The economic and regulatory environment is dynamic. New legislation like the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) is fundamentally altering the economic calculus of product selection, requiring a strategic pivot away from a sole focus on high-revenue blockbuster drugs.

- Integration is Everything: Success depends on a holistic strategy that seamlessly integrates legal, regulatory, scientific, and commercial functions. Siloed thinking is a recipe for failure in this complex and interconnected industry.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. How does the potential launch of an “Authorized Generic” (AG) by the brand company affect the strategic decision to pursue a Paragraph IV challenge?

The potential for an AG launch is a critical variable in the risk/reward calculation for a Paragraph IV challenge. An AG, which is the brand’s own product marketed as a generic, can compete directly with the first-to-file (FTF) generic during the 180-day exclusivity period. This can slash the FTF’s revenue during that crucial period by 40-52%. Therefore, when evaluating a PIV opportunity, a generic company must assess the likelihood of the brand launching an AG. This involves analyzing the brand’s past behavior, the terms of their agreements with other companies, and the overall market dynamics. If an AG launch is considered highly likely, it diminishes the value of the 180-day exclusivity prize. This may lead a company to: (a) decide a high-risk PIV challenge is not worth the reduced reward, especially for smaller market drugs; or (b) place a higher value on negotiating a settlement that includes a “no-AG” clause, where the brand contractually agrees not to launch an AG in exchange for other concessions, such as a later entry date for the generic.

2. Under what specific circumstances should a company choose the 505(b)(2) pathway over a traditional ANDA (505(j)), even if it means higher development costs?

A company should strategically opt for the more complex 505(b)(2) pathway in several key scenarios. First, when the goal is to circumvent a competitive barrier in the traditional generic space, such as a first-filer’s 180-day exclusivity. As seen in the Norvasc® case, developing a product with a different salt form and filing a 505(b)(2) can allow a company to enter the market without being blocked by the ANDA exclusivity. Second, it is the correct path when the company has developed a product that offers a clinical advantage over the RLD (e.g., a new, more convenient dosage form, a better dosing regimen, or a new indication). While this requires additional “bridging” studies, the resulting product is differentiated from both the brand and other generics and may qualify for its own 3-year period of market exclusivity. This creates a higher-value, “branded generic” or “supergeneric” product with a more durable market position.

3. What is the strategic role of Inter Partes Review (IPR) at the PTAB, and when should it be deployed in an ANDA litigation strategy?

An IPR is a powerful tool that should be considered in nearly every PIV litigation strategy. It allows a generic company to challenge the validity of a patent before a panel of technically expert administrative patent judges at the USPTO, a process that is often faster and less costly than district court litigation. The decision to file an IPR should be made early, typically within one year of being sued for infringement to avoid a statutory bar. It is most effective when the generic has strong invalidity arguments based on prior art patents and publications, as these are the only grounds permitted in an IPR. A successful IPR can invalidate the patent(s)-in-suit, effectively ending the litigation on favorable terms. The risk is that if the IPR fails and the patent is upheld by the PTAB, the generic company is estopped from raising the same invalidity arguments in district court. Therefore, the decision to file an IPR requires a careful calculation of the strength of the invalidity case versus the risk of estoppel.

4. How is the “substantially complete” standard for a first-to-file ANDA practically defined, and what are the most common pitfalls that cause companies to fail this standard?

While there is no exhaustive public list, the FDA’s “substantially complete” standard means the ANDA, on its face, contains all the scientific data and administrative information required by statute and regulation to permit a substantive review. Common pitfalls that lead to a Refuse-to-Receive (RTR) decision and the loss of a filing date include both major and seemingly minor errors. Major issues include missing or grossly deficient bioequivalence data, incomplete CMC information, or a failure to address all patents listed in the Orange Book. However, seemingly minor administrative errors can also be fatal, such as failing to include the correct FDA forms (like Form 356h), missing signatures, or, critically, failing to pay the GDUFA user fee within the specified timeframe. The best practice is to use the FDA’s own filing checklists and guidance documents, such as the “Good ANDA Submission Practices” guidance, as a meticulous pre-flight check before submission to ensure every required element is present and correctly formatted.

5. With the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) potentially lowering the prices of top-selling drugs, how should generic companies adjust their product selection models for PIV challenges?

The IRA fundamentally complicates product selection for PIV challenges. Generic companies must now build a new layer of predictive analysis into their models. Instead of just forecasting brand sales, they must now also forecast the probability of a drug being selected for IRA price negotiation and the potential magnitude of the resulting price reduction (the “Maximum Fair Price” or MFP). This requires analyzing a drug’s total Medicare spend, its time on the market, and whether it is a small molecule or biologic, as these are key criteria for IRA selection. A blockbuster drug that is highly likely to face a steep price cut under the IRA becomes a much less attractive PIV target, as the potential profit margin is severely compressed. The strategic adjustment will likely involve a diversification of targets: some companies may still challenge the biggest drugs but with lower profit expectations, while others will pivot to focus on “middle-tier” drugs that generate substantial revenue but are less likely to hit the IRA’s radar, or on more complex 505(b)(2) products where value is less dependent on the brand’s price alone.

Works cited

- The Definitive Guide to Generic Drug Approval in the U.S.: From ANDA to Market Dominance – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/obtaining-generic-drug-approval-in-the-united-states/

- The Generic Drug Approval Process – FDA, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/cder-conversations/generic-drug-approval-process

- 40th Anniversary of the Generic Drug Approval Pathway – FDA, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/cder-conversations/40th-anniversary-generic-drug-approval-pathway

- The Hatch-Waxman 180-Day Exclusivity Incentive Accelerates Patient Access to First Generics, accessed August 17, 2025, https://accessiblemeds.org/resources/fact-sheets/the-hatch-waxman-180-day-exclusivity-incentive-accelerates-patient-access-to-first-generics/

- The ANDA Process: A Guide to FDA Submission & Approval – Excedr, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.excedr.com/blog/what-is-abbreviated-new-drug-application

- Navigating the ANDA and FDA Approval Processes – bioaccess, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.bioaccessla.com/blog/navigating-the-anda-and-fda-approval-processes

- What is a generic drug, and how does it get approved? – Patsnap Synapse, accessed August 17, 2025, https://synapse.patsnap.com/article/what-is-a-generic-drug-and-how-does-it-get-approved

- Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) – FDA, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/types-applications/abbreviated-new-drug-application-anda

- Essential ANDA Checklist: Key Steps to Streamline Your Filing Process, accessed August 17, 2025, https://vicihealthsciences.com/anda-checklist-for-filing-process/

- The Hatch-Waxman Act: A Primer – Congress.gov, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.congress.gov/crs_external_products/R/PDF/R44643/R44643.3.pdf

- What is Hatch-Waxman? – PhRMA, accessed August 17, 2025, https://phrma.org/resources/what-is-hatch-waxman

- Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act – Wikipedia, accessed August 17, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Drug_Price_Competition_and_Patent_Term_Restoration_Act

- Hatch-Waxman Act | Practical Law – Westlaw, accessed August 17, 2025, https://content.next.westlaw.com/practical-law/document/I2e45aeaf642211e38578f7ccc38dcbee/Hatch-Waxman-Act?viewType=FullText&transitionType=Default&contextData=(sc.Default)

- The Regulatory Pathway for Generic Drugs: A Strategic Guide to Market Entry and Competitive Advantage – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-regulatory-pathway-for-generic-drugs-explained/

- Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations …, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-approvals-and-databases/approved-drug-products-therapeutic-equivalence-evaluations-orange-book

- Patent Use Codes for Pharmaceutical Products: A Comprehensive Analysis for Strategic Advantage – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/patent-use-codes-for-pharmaceutical-products-a-comprehensive-analysis/

- The NBER Orange Book Dataset: A user’s guide – PMC, accessed August 17, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10731339/

- ANDA Litigation: Strategies and Tactics for Pharmaceutical Patent Litigators, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/anda-litigation-strategies-and-tactics-for-pharmaceutical-patent-litigators/

- ANDA Submissions: Guidance, Process & Requirements – DocShifter, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.docshifter.com/blog/abbreviated-new-drug-applications/

- Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) Forms and Submission Requirements – FDA, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/abbreviated-new-drug-application-anda/abbreviated-new-drug-application-anda-forms-and-submission-requirements

- What Is the Approval Process for Generic Drugs? – FDA, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/generic-drugs/what-approval-process-generic-drugs

- Bioequivalence Studies & Abbreviated Drug Applications – Allucent, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.allucent.com/resources/blog/bioequivalence-studies-support-abbreviated-new-drug-applications

- Requirements for Submission of Bioequivalence Data; Final Rule – Federal Register, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2009/01/16/E9-884/requirements-for-submission-of-bioequivalence-data-final-rule

- Requirements for Submission of In Vivo Bioequivalence Data; Proposed Rule, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2003/10/29/03-27187/requirements-for-submission-of-in-vivo-bioequivalence-data-proposed-rule

- Title: Requirements for Submission of In Vivo Bioequivalence Data; Proposed Rule – Reginfo.gov, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.reginfo.gov/public/do/DownloadDocument?objectID=8710101

- Quality by Design for ANDAs: An Example for Immediate-Release Dosage Forms – Pharma Excipients, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.pharmaexcipients.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/Quality-by-Design-for-ANDAs.pdf

- Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) Approval Process – FDA, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/media/166141/download

- Comprehensive Guide to Streamline Generic Drug Applications(ANDA) Submission Process, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.freyrsolutions.com/blog/a-comprehensive-guide-to-streamline-generic-drug-applications-anda-towards-fda

- Paragraph 1,2,3,4 certification usfda | PPTX – SlideShare, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.slideshare.net/slideshow/paragraph-1234-certification-usfda/99185767

- How many types of patent certifications are available to file an ANDA? – Patsnap Synapse, accessed August 17, 2025, https://synapse.patsnap.com/blog/how-many-types-of-patent-certifications-are-available-to-file-an-anda

- 21 CFR 314.94 — Content and format of an ANDA. – eCFR, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-21/chapter-I/subchapter-D/part-314/subpart-C/section-314.94

- What Every Pharma Executive Needs to Know About Paragraph IV …, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/what-every-pharma-executive-needs-to-know-about-paragraph-iv-challenges/

- NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES REGULATION AND WELFARE: EVIDENCE FROM PARAGRAPH IV GENERIC ENTRY IN THE PHARMACEUTICAL INDUSTRY Lee G., accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w17188/w17188.pdf

- Pre-ANDA Litigation: Strategies and Tactics for Developing a Drug Product and Patent Portfolio – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/pre-anda-litigation-strategies-and-tactics-for-developing-a-drug-product-and-patent-portfolio/

- The Role of Regulatory Agencies and Intellectual Property: Part II – PMC, accessed August 17, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4484957/

- Earning Exclusivity: Generic Drug Incentives and the Hatch-‐Waxman Act1 C. Scott – Stanford Law School, accessed August 17, 2025, https://law.stanford.edu/index.php?webauth-document=publication/259458/doc/slspublic/ssrn-id1736822.pdf

- Patent Certifications and Suitability Petitions – FDA, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/abbreviated-new-drug-application-anda/patent-certifications-and-suitability-petitions

- How to get the first ANDA Approval for a generic drug? – GreyB, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.greyb.com/blog/getting-the-first-anda-approval/

- Pre-ANDA Litigation, Chapter 18: ANDA Preparation (with an Eye toward Approval and Litigation) and the FDA Review – Duane Morris, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.duanemorris.com/articles/static/preanda_litigation_2014_ch18.pdf

- Antitrust Issues in the Settlement of Pharmaceutical Patent Disputes, Part II, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/news/speeches/antitrust-issues-settlement-pharmaceutical-patent-disputes-part-ii

- The timing of 30‐month stay expirations and generic entry: A cohort study of first generics, 2013–2020 – PMC, accessed August 17, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8504843/

- Beyond the Merits: Generic Company Defense Strategies – Pharmaceutical Executive, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.pharmexec.com/view/beyond-merits-generic-company-defense-strategies-hatch-waxman-litigation

- Generic Drug Challenges Prior to Patent Expiration C. Scott Hemphill* and Bhaven N. Sampat – NYU Law, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.law.nyu.edu/sites/default/files/ECM_PRO_064165.pdf

- Paragraph IV Cases – Orange Book Blog, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.orangebookblog.com/hatchwaxman_litigation/

- Generic Drug / ANDA Litigation – Husch Blackwell, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.huschblackwell.com/industries_services/generic-drug-/-anda-litigation

- PTAB statistics show interesting trends for Orange Book and biologic patents in AIA proceedings | Mintz, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.mintz.com/insights-center/viewpoints/2231/2021-08-24-ptab-statistics-show-interesting-trends-orange-book-and

- Hatch-Waxman 2023 Year in Review – Fish & Richardson, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.fr.com/insights/thought-leadership/articles/hatch-waxman-2023-year-in-review-2/

- NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES NO FREE LAUNCH: AT-RISK ENTRY BY GENERIC DRUG FIRMS Keith M. Drake Robert He Thomas McGuire Alice K. N, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w29131/w29131.pdf

- Launch-at-Risk Analysis | Secretariat, accessed August 17, 2025, https://secretariat-intl.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/CaseStudy-Launch-at-Risk-Analysis-Draft.pdf

- The Role of Litigation Data in Predicting Generic Drug Launches – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-role-of-litigation-data-in-predicting-generic-drug-launches/

- No Free Launch: At-Risk Entry by Generic Drug Firms – IDEAS/RePEc, accessed August 17, 2025, https://ideas.repec.org/p/nbr/nberwo/29131.html

- Strategies that delay or prevent the timely availability of affordable generic drugs in the United States, accessed August 17, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4915805/

- Understanding the Impact of Authorized Generics on Drug Pricing: A Strategic Imperative for Market Domination – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/understanding-the-impact-of-authorized-generics-on-drug-pricing-the-entacapone-case-study/

- Authorized Generic Drugs: Short-Term Effects and Long-Term Impact | Federal Trade Commission, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.ftc.gov/sites/default/files/documents/reports/authorized-generic-drugs-short-term-effects-and-long-term-impact-report-federal-trade-commission/authorized-generic-drugs-short-term-effects-and-long-term-impact-report-federal-trade-commission.pdf

- Study: Delaying authorized generics is on the decline | RAPS, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.raps.org/news-and-articles/news-articles/2025/6/study-delaying-authorized-generics-is-on-the-decli

- How to Track Competitor R&D Pipelines Through Drug Patent …, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/how-to-track-competitor-rd-pipelines-through-drug-patent-filings/

- Inside the ANDA Approval Process: What Patent Data Can Tell You – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/inside-the-anda-approval-process-what-patent-data-can-tell-you/

- Drugpatentwatch Business Intelligence: Make Better Decisions : Finding and Evaluating Generic and Branded Drug Market Entry Opportunities (Series #1) (Paperback) – Walmart, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.walmart.com/ip/Drugpatentwatch-Business-Intelligence-Make-Better-Decisions-Finding-Evaluating-Generic-Branded-Drug-Market-Entry-Opportunities-Series-1-Paperback-9781934899397/265313004

- Abbreviated New Drug Applications (ANDA) Explained: A Quick-Guide – The FDA Group, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.thefdagroup.com/blog/abbreviated-new-drug-applications-anda

- ANDA or 505(b)(2): Choosing the Right Abbreviated Approval Pathway for Your Drug, accessed August 17, 2025, https://premier-research.com/perspectives/choosing-the-right-abbreviated-approval-pathway-for-your-drug/

- Understand the difference between 505(j), 505(b)(1) and 505(b)(2) – Veeprho, accessed August 17, 2025, https://veeprho.com/understanding-difference-between-505j-505b1-and-505b2/

- 505(b)(2) vs. 505(j): NDA or ANDA for Your Drug? – Allucent, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.allucent.com/resources/blog/what-difference-between-andas-and-505b2-ndas

- What Is 505(b)(2)? | Premier Consulting, accessed August 17, 2025, https://premierconsulting.com/resources/what-is-505b2/

- Abbreviated Approval Pathways for Drug Product: 505(b)(2) or ANDA? – FDA, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/cder-small-business-industry-assistance-sbia/abbreviated-approval-pathways-drug-product-505b2-or-anda

- Understanding the Differences Between 505(j), 505(b)(1), and 505(b)(2) Drug Approval Pathways – Pharma Growth Hub, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.pharmagrowthhub.com/post/understanding-the-differences-between-505-j-505-b-1-and-505-b-2-drug-approval-pathways

- The 505(b)(2) Drug Approval Pathway: A Potential Solution for the Distressed Generic Pharma Industry in an Increasingly Diluted ANDA Marketplace? | Sterne Kessler, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.sternekessler.com/news-insights/insights/505b2-drug-approval-pathway-potential-solution-distressed-generic-pharma/

- FDA updates policies for reviewing ANDAs – RAPS, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.raps.org/news-and-articles/news-articles/2023/10/fda-updates-policies-for-reviewing-andas

- ANDA Submissions | Amendments to Abbreviated New Drug Applications Under GDUFA, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/anda-submissions-amendments-abbreviated-new-drug-applications-under-gdufa

- ANDA Submissions – Amendments to Abbreviated New Drug Applications under GDUFA – 09/10/2024 | FDA, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/news-events-human-drugs/anda-submissions-amendments-abbreviated-new-drug-applications-under-gdufa-09102024

- Prioritization of the Review of Original ANDAs, Amendments, and Supplements – FDA, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/media/89061/download

- How the IRA is impacting the generic drug market – PhRMA, accessed August 17, 2025, https://phrma.org/blog/how-the-ira-is-impacting-the-generic-drug-market