Part 1: The Bedrock of Biosimilarity: Foundational Principles

Beyond “Generic Biologics”: A New Paradigm for Competition and Access

In the high-stakes world of pharmaceuticals, language matters. For decades, the term “generic” has been synonymous with cost-effective, chemically identical copies of small-molecule drugs. It’s a simple, powerful concept: a generic ibuprofen is, for all intents and purposes, the same as brand-name ibuprofen. It’s tempting, then, to apply this same mental shortcut to the burgeoning world of biosimilars, labeling them as mere “generic biologics.” This, however, is a profound and costly misunderstanding. The analogy doesn’t just fall short; it describes a completely different reality.

Imagine a small-molecule drug is like a simple brick, manufactured through a predictable chemical synthesis. Its structure is well-defined and easily replicated. A biologic, in stark contrast, is like a sprawling, intricately designed cathedral, built not from inert chemicals but from the complex and dynamic machinery of living cells.1 These therapies—monoclonal antibodies, growth factors, and enzymes—are large, exquisitely complex proteins whose final, functional form is dictated by a thousand subtle variables within a proprietary manufacturing process.4 The temperature of the bioreactor, the pH of the growth medium, the specific purification columns used—each step leaves an indelible mark on the final molecule, influencing its three-dimensional folding, the delicate patterns of sugar molecules (glycosylation) that adorn its surface, and its propensity to form aggregates.

This inherent complexity leads to a fundamental scientific truth: it is impossible for two different manufacturers, using two independently developed processes, to create identical biologics.7 Even the originator manufacturer sees slight, controlled variations from one batch to the next.10 This reality shatters the generic paradigm and necessitates a completely new scientific and regulatory framework. The goal is no longer to prove “identity,” but to demonstrate “similarity”—a high degree of structural and functional likeness with no clinically meaningful differences in safety or efficacy compared to the original, approved biologic.12

This is where the concept of analytical similarity assessment moves from a technical footnote to the very heart of the biosimilar enterprise. It is the scientific and economic linchpin upon which the entire industry is built. It is through an exhaustive, state-of-the-art analytical comparison that a biosimilar developer convinces regulators that their product, while not an identical twin, is a functionally indistinguishable sibling to the originator. Mastering this process is the key to unlocking one of the most significant commercial opportunities in modern medicine.

The stakes could not be higher. The global biosimilar market, valued at approximately $26.5 billion in 2024, is projected to skyrocket to an astonishing $185.1 billion by 2033, exhibiting a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of over 24%. Other forecasts echo this explosive growth, predicting a market size of over $102 billion by 2032. This surge is fueled by a “patent cliff” of blockbuster biologics—drugs with tens of billions in annual sales—losing their market exclusivity, creating a once-in-a-generation opportunity for competition.14 For healthcare systems buckling under the weight of high-cost therapies, and for patients seeking access to life-altering medicines, biosimilars represent not just a market shift, but a vital lifeline.17 This report will serve as your guide through the intricate regulatory landscape of analytical similarity, transforming its complexities from a daunting challenge into a powerful competitive advantage.

Defining the Core Concepts: Biosimilar, Reference Product, and the “Highly Similar” Standard

To navigate this landscape, we must first speak the language of the regulators. The definitions are precise, nuanced, and carry significant strategic weight.

A biosimilar is a biological product that is approved based on a comprehensive dossier of evidence demonstrating it is highly similar to an already approved biological product.20 This previously approved product is known as the

reference product (or originator biologic). The reference product is the single, specific biologic against which the proposed biosimilar is compared throughout its development program. It is the benchmark, the gold standard, that the biosimilar must match.22

While this core concept is shared globally, the two most influential regulatory bodies, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA), frame their definitions with subtle but important differences.

The FDA, operating under the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA), defines a biosimilar as a biological product that is “highly similar to the reference product notwithstanding minor differences in clinically inactive components” and for which there are “no clinically meaningful differences between the biological product and the reference product in terms of the safety, purity, and potency of the product”.2

The EMA, which pioneered the biosimilar pathway, defines a biosimilar as a biological medicine that is “highly similar to a reference medicine already approved in the EU… in terms of structure, biological activity and efficacy, safety and immunogenicity profile“.4

At first glance, these definitions appear to be two sides of the same coin. Both hinge on the term “highly similar” and the principle of “no clinically meaningful differences.” However, the nuances matter. The FDA’s language explicitly carves out an allowance for “minor differences in clinically inactive components.” This provides a specific, though narrow, regulatory space for a biosimilar to differ from its reference product—for instance, in the use of a different stabilizing excipient in the final formulation, provided that excipient can be proven to have no clinical effect. The EMA’s definition is more holistic, focusing on the overall similarity of the entire profile.

These distinctions are not merely academic; they reflect differing regulatory philosophies that can shape a developer’s strategy. When presenting a case to the FDA, a developer might need to construct a specific, targeted argument to justify why a different buffer or stabilizer is “clinically inactive.” For the EMA, the narrative might focus more broadly on demonstrating that the overall safety and efficacy profile, as a whole, is unchanged, regardless of the specific component-level difference. A successful global development program, therefore, must be designed from the outset with the sophistication to satisfy the unique demands of both definitions. The data package must be robust enough, and the regulatory strategy flexible enough, to tell a compelling story of similarity to multiple audiences, each with its own dialect.

The Totality-of-the-Evidence Pyramid: Why Analytical Assessment is the Foundational Cornerstone

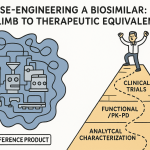

How does a developer prove this high similarity? The answer lies in a paradigm that fundamentally inverts the traditional drug development process: the totality-of-the-evidence approach.12 This is the universal standard for biosimilar approval, embraced by both the FDA and the EMA.

Imagine the evidence required for approval as a pyramid. In traditional drug development for a novel molecule, the pyramid is balanced on its point. The vast bulk of the evidence, the weight of the entire structure, rests on massive, expensive, and time-consuming Phase 3 clinical trials that are designed to independently establish the product’s safety and efficacy.26

For biosimilars, this pyramid is flipped on its head. The goal is not to independently establish safety and efficacy—that has already been done for the reference product.21 The goal is to demonstrate similarity. Therefore, the foundation of the pyramid, its broad and unshakeable base, is an exhaustive and highly sensitive

comparative analytical assessment.22 This foundational layer involves a deep, multi-faceted characterization of the proposed biosimilar side-by-side with the reference product, using a battery of state-of-the-art scientific instruments to compare everything from the primary amino acid sequence to the complex 3D structure and biological function.

Built upon this massive analytical foundation are progressively smaller, more targeted layers of evidence. The next layer may consist of non-clinical studies in animals, if necessary, to address any specific questions that remain after the analytical comparison. Above that is a layer of clinical pharmacology studies, typically in healthy volunteers, to demonstrate that the biosimilar behaves the same way as the reference product in the human body (pharmacokinetics, or PK) and has the same immediate biological effect (pharmacodynamics, or PD). Finally, at the very apex of the pyramid, sits a targeted, confirmatory clinical study in patients.

The logic of this inverted pyramid is powerful and pragmatic. The analytical tools used today are far more sensitive than clinical trials at detecting small differences between two products.21 A subtle change in a glycosylation pattern that might have a potential, albeit unlikely, impact on immunogenicity would be immediately obvious in a mass spectrometer but would be completely invisible in a 500-patient clinical trial. Regulators recognize this. The more robust, comprehensive, and convincing the demonstration of analytical similarity at the base of the pyramid, the less “residual uncertainty” there is about the product’s behavior. With less uncertainty, the need for extensive clinical data at the top of the pyramid diminishes.

This creates a profound strategic opportunity. In this new paradigm, the analytical development team is not a support function; it is a primary driver of value. Every dollar invested in acquiring the most sensitive analytical technology and the expertise to use it is an investment in de-risking the entire development program. A flawlessly executed analytical package can reduce the scope of clinical trials, shorten timelines by years, and save hundreds of millions of dollars. It is the engine that makes the abbreviated pathway—and the entire biosimilar market—possible.

Part 2: The Regulatory Gauntlet: FDA and EMA Frameworks

A Tale of Two Agencies: An Overview of the FDA and EMA Pathways

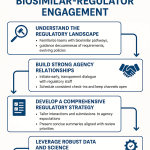

While united by the core principles of totality-of-the-evidence and analytical similarity, the regulatory pathways of the FDA and the EMA have distinct histories, structures, and nuances that every biosimilar developer must master. These differences shape not only the submission process but also the strategic decisions made years before a dossier is ever compiled.

The European Medicines Agency (EMA) is the undisputed pioneer in biosimilar regulation. Having established its legal framework in 2004 and approved the first biosimilar (a somatropin product) in 2006, the EMA has nearly two decades of experience in this space.25 This long history has created a mature, predictable, and well-understood regulatory environment. The EMA’s approval process operates under a centralized procedure, meaning a single application and evaluation grants marketing authorization across all EU member states, offering a streamlined path to a massive market.1 The EMA’s approach is grounded in a comprehensive “comparability exercise,” a stepwise process that begins with quality (analytical) data and proceeds to non-clinical and clinical data as needed to demonstrate similarity.7

The evidence acquired over 10 years of clinical experience shows that biosimilars approved through EMA can be used as safely and effectively in all their approved indications as other biological medicines.

Citation: European Medicines Agency. (2017). Biosimilars in the EU: Information guide for healthcare professionals.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) entered the biosimilar arena later, with its pathway established by the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA) of 2009, which was part of the Affordable Care Act. The first US biosimilar was not approved until 2015. The FDA’s framework is characterized by a “stepwise” approach to generating data, which, like the EMA’s, is founded on robust analytical comparison.1 However, the US system introduced unique concepts and complexities, most notably the legal and commercial distinction between a “biosimilar” and an “interchangeable biosimilar,” a designation that allows for pharmacy-level substitution without prescriber intervention, subject to state laws.

The EMA’s head start has had a tangible impact. With a longer track record and a vast repository of real-world data from dozens of approved biosimilars, the agency has grown increasingly confident in the scientific principles underpinning the pathway. This confidence is reflected in its forward-thinking initiatives, such as the recent reflection paper exploring a “tailored clinical approach”. This initiative signals a potential future where, for well-understood molecules, a comparative clinical efficacy study might be waived entirely if analytical and pharmacokinetic data are sufficiently convincing, a move that would dramatically reduce development costs and timelines.

The FDA, while building on the EMA’s experience, has followed its own evolutionary path. Initially perceived as more conservative, the agency is now rapidly adapting its guidance based on accumulating scientific evidence. Its recent proposal to eliminate the need for dedicated “switching studies” for the interchangeability designation is a landmark example of this evolution, demonstrating a growing alignment with the global scientific consensus on the safety of switching between reference products and their biosimilars.38

For a developer, this “tale of two agencies” presents a critical strategic choice. A Europe-first launch strategy may benefit from the EMA’s more predictable pathway and deep well of precedent. Conversely, a US-first strategy, while navigating a more complex and litigious landscape, might be necessary to pursue the valuable market exclusivity period granted to the first biosimilar deemed “interchangeable”. The decision of where to launch first is not merely a commercial one; it is a complex regulatory calculation based on the specific molecule, the competitive landscape, and a deep understanding of the subtle but significant differences between these two powerful agencies.

The Reference Product Conundrum: Sourcing, Variability, and Bridging Studies

Perhaps the single greatest operational challenge in biosimilar development is the reference product itself. It is the sun around which the entire development program orbits, yet it can be an elusive, variable, and frustratingly complex benchmark. The challenges fall into two main categories: characterizing the inherent variability of a single reference product and navigating the differences between reference products sourced from different regions.

First, a biosimilar cannot be shown to be “highly similar” to a single data point. It must be shown to be similar to the reference product as it exists in the market, which includes its own natural, batch-to-batch variability. To do this, a developer must procure and extensively analyze multiple lots of the originator drug, preferably with a wide range of manufacturing dates and expiry periods.41 This allows them to establish a “quality range” for the originator’s critical attributes, creating a target for their own product to hit. However, this process is fraught with difficulty. Originator companies carefully control their supply chains, making it logistically challenging and expensive to source the dozens of lots required for a full characterization and all subsequent comparative studies.41 Furthermore, developers face the risk of the “moving target”: the originator may change its own manufacturing process over time, a common practice to improve yield or efficiency. If the reference product on the market today is different from the one available when the biosimilar program began, the developer may be forced to restart parts of their characterization work.

This challenge is magnified exponentially in the context of a global development program. The FDA requires a demonstration of biosimilarity to the US-licensed reference product. The EMA requires comparison to a reference product authorized in the European Economic Area (EEA). While these products share the same active substance, they are often manufactured in different facilities or using slightly different (though approved) processes. This can lead to minor but measurable differences in their analytical profiles.

Consequently, a developer cannot simply use data from a European clinical trial comparing their biosimilar to the EU-sourced reference product and submit it to the FDA. They must first build a scientific “bridge” to demonstrate that the EU- and US-sourced reference products are themselves highly similar, and that the clinical data generated against the EU product is therefore relevant to the US product. This typically requires a complex and costly 3-way bridging study, which often involves both analytical and clinical pharmacokinetic comparisons 43:

- Biosimilar vs. US-Sourced Reference Product

- Biosimilar vs. EU-Sourced Reference Product

- US-Sourced Reference Product vs. EU-Sourced Reference Product

This requirement adds a significant layer of cost, time, and logistical complexity to global programs. Sourcing multiple lots of two different reference products from two different continents is a Herculean task. Designing and executing a clinical study with three arms is more complex and expensive than a standard two-arm study. This is a major pain point for the industry and a key driver behind the push for global harmonization and the establishment of a “global reference standard” that could be used for development programs worldwide, eliminating the need for these duplicative and costly bridging exercises.45 For now, however, navigating the reference product conundrum is a critical test of a developer’s operational and regulatory prowess.

Part 3: The Anatomy of Similarity: Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs)

Identifying What Matters: An Introduction to Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs)

Once a developer has thoroughly characterized the reference product, the next crucial step is to translate that mountain of data into a focused plan for action. A complex monoclonal antibody can have hundreds of measurable physical, chemical, and biological properties, or Quality Attributes (QAs). It is neither practical nor scientifically necessary to treat all of them with the same level of scrutiny. The key is to identify which attributes truly matter for the product’s clinical performance. This is the role of the Critical Quality Attribute (CQA).

A CQA is formally defined as a physical, chemical, biological, or microbiological property or characteristic that should be within an appropriate limit, range, or distribution to ensure the desired product quality.26 In the context of biosimilarity, these are the attributes that have a potential impact on the product’s activity, pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics (PK/PD), safety, or immunogenicity.26 The process of identifying CQAs is a systematic, risk-based exercise that forms the strategic blueprint for the entire analytical similarity assessment.

The process typically begins with the creation of a Quality Target Product Profile (QTPP), which is a prospective summary of the quality characteristics of a drug product that ideally will be achieved to ensure the desired quality, taking into account safety and efficacy. Based on the QTPP and an exhaustive analysis of the reference product, the developer compiles a comprehensive list of all potential QAs.

Then, the critical step: a risk assessment is performed to distinguish the truly “critical” attributes from the rest. This is not a guess; it’s a structured scientific evaluation. A common approach, as described by industry experts, involves scoring each QA on two axes:

- Impact: The known or potential effect of the attribute on clinical performance (bioactivity, PK, immunogenicity, safety). This is often scored on a numerical scale.27 For example, the primary amino acid sequence would receive the highest possible impact score, as a single change could completely abrogate function.

- Uncertainty: The level of confidence in the information used to assess the impact. This score reflects how much is known about the attribute’s role. An attribute with a well-documented impact in the scientific literature would have low uncertainty, while a novel impurity with unknown effects would have high uncertainty.27

Attributes that score high on this risk matrix are designated as CQAs and become the focus of the most rigorous comparative analysis. This CQA identification process is where science and strategy converge. An incomplete list of CQAs risks a rejection from regulators, while an overly inclusive list wastes precious time, resources, and capital on analyzing attributes that have no bearing on clinical performance.

This is also where competitive intelligence can provide a powerful edge. A deep dive into an originator’s patent portfolio, particularly its formulation and manufacturing process patents, can be incredibly revealing. These documents often describe the specific technical challenges the originator faced and the attributes they had to control to overcome them. For instance, a patent might detail experiments to reduce aggregation by controlling the level of a specific excipient. This is a clear signal to the biosimilar developer that aggregate levels are a CQA for that molecule. Tools like DrugPatentWatch are invaluable for this type of analysis, providing a structured platform to dissect competitor patents and extract this crucial intelligence, transforming a legal document into a scientific roadmap.16

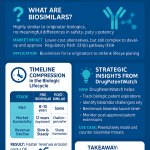

The FDA’s Tiered Approach: A Risk-Based Framework for Analysis

Having identified the CQAs, the FDA provides a structured framework for how they should be evaluated statistically. This is the three-tiered approach, a risk-based system that matches the level of statistical rigor to the criticality of the attribute.51 This system is not just a regulatory checklist; it is a practical guide for allocating analytical resources efficiently.

Tier 1: The Most Critical Attributes

This tier is reserved for CQAs with the highest potential impact on clinical outcomes. These are typically attributes directly linked to the molecule’s mechanism of action—for example, a cell-based potency assay that measures the drug’s intended biological effect, or a binding assay for the primary therapeutic target.

For these paramount attributes, the FDA recommends the most stringent statistical evaluation: equivalence testing.53 This formal statistical test is designed to provide a high degree of confidence that the means of the biosimilar and reference product are sufficiently close to be considered equivalent.

Tier 2: Attributes with Moderate Risk

Tier 2 includes CQAs that have a lower, but still potentially meaningful, impact on clinical performance. Examples might include certain glycosylation patterns that are known to have a minor influence on PK, or levels of certain charge variants.

For these attributes, the FDA recommends a slightly less stringent quality range approach.51 In this method, a statistical range is established based on the variability of the reference product (typically, the mean ± a certain number of standard deviations). The biosimilar then demonstrates similarity by showing that a high percentage of its measured values (e.g., 90%) fall within this pre-defined range.

Tier 3: Attributes with Low Risk

The final tier is for attributes with the lowest risk or those that are not easily quantifiable (e.g., the appearance of a solution). For these CQAs, the FDA considers raw data and graphical comparisons to be sufficient.51 This involves presenting the data from the biosimilar and reference lots side-by-side in plots or tables for visual inspection by the regulator.

Table 1: The FDA’s CQA Tiered System for Analytical Similarity

| Tier | Risk to Clinical Performance | Example CQAs | Recommended Statistical Approach | Relative Resource Intensity |

| Tier 1 | Highest | Potency (cell-based assay), Target Receptor Binding | Formal Equivalence Testing (e.g., TOST) | High |

| Tier 2 | Moderate | Specific Glycoform levels, Charge Variant profile | Quality Range Approach (e.g., 90% of lots within Mean ± 3 SD of Reference) | Medium |

| Tier 3 | Lowest | Aggregate levels (if low risk), Qualitative attributes (e.g., visual appearance) | Raw Data & Graphical Comparison (side-by-side plots) | Low |

This tiered system provides a clear roadmap for developers. However, the classification of an attribute into a specific tier is not always clear-cut and is often a point of negotiation with the agency. A developer’s ability to provide a strong scientific justification for placing an attribute in a lower tier can have significant financial implications. For example, successfully arguing that a specific PTM should be moved from Tier 1 to Tier 2 based on new scientific evidence could save the company from having to conduct a difficult and high-risk equivalence test. This requires a deep, molecule-specific understanding of structure-activity relationships, empowering a company to engage with the FDA from a position of scientific strength and optimize its analytical strategy.

The EMA’s Perspective on Quality Attributes: A Holistic Comparability Approach

While the FDA has outlined a relatively prescriptive tiered system, the EMA takes a more principles-based and holistic approach. The EMA does not formally use the “Tier 1, 2, 3” nomenclature, but its underlying scientific philosophy is remarkably similar, focusing on risk and the depth of evidence.

The cornerstone of the EMA’s quality assessment is the comparability exercise.34 The agency’s guidelines (such as the overarching

Guideline on similar biological medicinal products containing biotechnology-derived proteins as active substance: quality issues) call for an extensive, side-by-side comparison of the biosimilar and the reference product using a panel of state-of-the-art analytical methods.

Instead of a rigid tiering system, the EMA emphasizes the establishment of quantitative ranges for relevant quality attributes. These ranges are to be based on the characterization of a suitable number of reference product batches to capture its inherent variability. The goal for the biosimilar is to demonstrate that its own attributes fall within these established ranges. The key principle is that the biosimilar’s range of variability should not be wider than that of the originator, unless a compelling scientific justification is provided.

Where the EMA’s approach offers more flexibility, it also places a greater burden of justification on the sponsor. Any observed difference between the biosimilar and the reference product, no matter how small, must be thoroughly investigated and its potential impact on safety and efficacy must be scientifically justified.34 If a difference is found and its clinical impact cannot be confidently dismissed, the EMA may require additional non-clinical or clinical data to resolve the uncertainty.

This approach can be seen as less of a checklist and more of a scientific dissertation. An FDA submission might focus on demonstrating that each CQA passes its pre-defined statistical gate (e.g., the Tier 1 equivalence test). An EMA submission, in contrast, must weave the results from all analyses into a single, cohesive scientific narrative that, in its totality, makes a compelling case for similarity. A minor difference in one attribute might be acceptable to the EMA if the developer can show overwhelming similarity across a dozen other orthogonal attributes and provide a strong mechanistic argument for why the observed difference is clinically irrelevant.

For developers, this means that success with the EMA depends not just on generating high-quality data, but on the strength of the scientific argumentation presented in Module 3 of the Common Technical Document (CTD). It favors companies that possess not only top-tier analytical labs but also deep scientific expertise and excellent regulatory science communication skills to build and defend a comprehensive, data-driven story of similarity.

Part 4: The Scientist’s Toolbox: State-of-the-Art Analytical Characterization

Demonstrating analytical similarity is not a theoretical exercise; it is a meticulous, hands-on scientific endeavor that relies on a sophisticated arsenal of analytical instruments. These technologies are the eyes and ears of the developer, allowing them to “fingerprint” the reference biologic with incredible precision and then demonstrate that their own product bears the same essential marks. The evolution of these tools is the primary reason regulators now have the confidence to approve biosimilars with streamlined clinical programs.30

Mapping the Molecule: Techniques for Primary and Higher-Order Structure

At the most fundamental level, a biosimilar must be a structural match to its reference product. This comparison is conducted across multiple levels of structural organization, from the linear sequence of amino acids to the complex three-dimensional fold that is essential for biological function.

Primary Structure

The primary structure—the unique sequence of amino acids that forms the protein’s backbone—is the one attribute where identity is expected. Any difference in the amino acid sequence would mean the product is not a biosimilar but a different molecule altogether.17

- Key Techniques: The gold standard for confirming the primary sequence is peptide mapping combined with liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS). In this method, the protein is enzymatically digested into smaller, more manageable peptides. These peptides are then separated by liquid chromatography and their mass and sequence are determined with high accuracy by a mass spectrometer. By piecing together the information from all the peptides, scientists can confirm the entire amino acid sequence with full coverage.2 Older techniques like

Edman degradation can also be used to sequence the ends of the protein chain.

Post-Translational Modifications (PTMs)

After the protein chain is synthesized, it undergoes a variety of chemical modifications known as PTMs. These are not encoded in the gene but are added by the cellular machinery. For many biologics, particularly monoclonal antibodies, PTMs are critical for function, stability, and immunogenicity.

- Key Attribute – Glycosylation: This is the enzymatic addition of complex sugar chains (glycans) to the protein. The pattern of glycosylation can significantly affect a monoclonal antibody’s ability to engage the immune system.

- Key Techniques: A suite of chromatographic and mass spectrometric methods is used. Glycans can be cleaved from the protein and analyzed separately using techniques like High-Performance Anion-Exchange Chromatography with Pulsed Amperometric Detection (HPAEC-PAD). Alternatively, LC-MS analysis of the intact protein or its subunits can reveal the profile of different glycoforms attached to the molecule.2

- Other Critical PTMs: Other important PTMs that must be compared include the formation of disulfide bonds (which stabilize the protein’s structure), oxidation of certain amino acids (which can be a sign of degradation), and deamidation (a common degradation pathway). These are typically assessed using highly sensitive peptide mapping LC-MS methods.

Higher-Order Structure (HOS)

The linear chain of amino acids folds into a specific, complex three-dimensional shape, known as its higher-order structure (HOS). This includes secondary (alpha-helices, beta-sheets), tertiary (the overall fold of a single chain), and quaternary (the arrangement of multiple chains) structures. The correct HOS is absolutely essential for the biologic’s function; a misfolded protein is an inactive and potentially immunogenic one.

- Key Techniques: Because HOS is a global property of the molecule, a panel of orthogonal techniques is required to assess it.

- Circular Dichroism (CD) Spectroscopy: Far-UV CD provides information on the secondary structure content, while near-UV CD is sensitive to the tertiary structure.

- Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy: This is another powerful technique for comparing the secondary structure of the biosimilar and reference product.

- Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC): This technique measures the thermal stability of the protein, providing an indirect but sensitive measure of the integrity of its tertiary structure.

- Hydrogen-Deuterium Exchange Mass Spectrometry (HDX-MS): This is a cutting-edge technique that provides high-resolution information on protein conformation and dynamics in solution. It measures the rate at which backbone hydrogens exchange with deuterium in the solvent, which is highly dependent on the local protein structure. Comparing the HDX-MS profiles of a biosimilar and reference product is a powerful way to demonstrate conformational equivalence.

The increasing power and sensitivity of these analytical tools, especially advanced mass spectrometry techniques like HDX-MS, are game-changers. They allow scientists to see differences between molecules with a level of detail that was unimaginable a decade ago. This technological leap is what underpins the entire modern biosimilar regulatory philosophy: if you can show with this level of precision that two molecules are structurally identical, or that any minor differences have no impact on conformation, the confidence that they will behave the same way in a patient increases dramatically. Companies that invest in and master these state-of-the-art platforms are not just improving their quality control; they are building a more compelling totality-of-the-evidence package that can directly lead to a more streamlined and successful regulatory outcome.

Function Follows Form: Potency and Binding Assays

Demonstrating that a biosimilar has the same structure as its reference product is a necessary but not sufficient condition for approval. The ultimate test is whether that structure translates into the same biological function. A perfectly folded antibody that cannot bind to its target is useless. Therefore, a comprehensive panel of functional assays is a critical component of the analytical similarity package, serving as the crucial link between the structural data and the clinical expectation.

These assays answer the vital “so what?” question for any minor structural differences observed during characterization. For instance, if peptide mapping reveals a slight difference in the glycosylation profile between the biosimilar and the reference product, it creates a point of residual uncertainty. Does this difference matter? A well-designed functional assay can provide the answer. If an Fc receptor binding assay shows that the biosimilar, despite its slightly different glycan profile, binds with equivalent affinity to key immune receptors like FcγRIIIa, it provides powerful evidence that the structural difference is not functionally significant and therefore unlikely to be clinically meaningful. This ability to mitigate the risk of minor structural deviations is the primary strategic value of a robust functional testing program.

The functional characterization program must be comprehensive, using multiple, orthogonal assays to probe all known biological activities of the molecule. These typically fall into two categories:

- Binding Assays: These assays measure the direct interaction of the biologic with its target(s). They are critical for confirming that the business end of the molecule is working correctly.

- Key Techniques:

- Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA): A widely used, plate-based method to quantify binding to a target antigen.

- Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR): A highly sensitive, real-time technique that provides detailed kinetic information about the binding interaction, including the association rate (kon) and dissociation rate (koff), which combine to give the affinity (KD).

- Flow Cytometry: Used to measure binding to targets expressed on the surface of cells.

- For monoclonal antibodies, it is essential to measure not only binding to the therapeutic target (e.g., TNF-α, VEGF) but also to the family of Fc receptors (e.g., FcγRs, FcRn), which are critical for the antibody’s immune effector functions and its half-life in the body.

- Cell-Based Potency Assays: These assays go a step further than binding and measure the ultimate biological consequence of that binding. They are considered one of the most important measures of a biologic’s function because they often reflect the product’s mechanism of action in a physiological context.

- Key Techniques: The specific assay depends entirely on the molecule’s mechanism of action. Examples include:

- Proliferation/Apoptosis Assays: Measuring the ability of the biologic to stimulate cell growth or induce programmed cell death.

- Neutralization Assays: Measuring the ability of an antibody to block the activity of a cytokine or virus.

- Reporter Gene Assays: Using an engineered cell line where target binding leads to the expression of an easily measurable reporter protein (e.g., luciferase).

- Antibody-Dependent Cell-Mediated Cytotoxicity (ADCC) Assays: A complex assay that measures the ability of an antibody to recruit immune cells (like Natural Killer cells) to kill a target cell.

A well-designed panel of functional assays provides a multi-dimensional view of the product’s activity. By demonstrating high similarity across a range of binding and cell-based assays, a developer builds a powerful case that their product will perform just like the originator when administered to a patient.

Ensuring Purity and Consistency: Analyzing Impurities and Aggregates

The final piece of the analytical puzzle is to characterize not just what you want in the vial, but also what you don’t. The analytical similarity assessment must include a rigorous comparison of the purity and impurity profiles of the biosimilar and the reference product. This is more than a simple quality control check; it serves as a sensitive fingerprint of the entire manufacturing process. Because the biosimilar developer must reverse-engineer the originator’s proprietary process, demonstrating a highly similar impurity profile provides strong indirect evidence that they have successfully replicated the critical process controls.

Impurities are generally categorized into two types:

- Product-Related Impurities: These are molecular variants of the desired product that form during manufacturing or storage. They are often structurally similar to the active drug but may have different activity or safety profiles.

- Key Impurities:

- Aggregates: When protein molecules clump together. This is a major concern as aggregates are frequently linked to an increased risk of unwanted immune responses (immunogenicity).26

- Fragments: Pieces of the protein that have broken off.

- Charge Variants: Versions of the protein with slight differences in electrical charge, often due to modifications like deamidation (creating more acidic species) or incomplete processing of the C-terminal lysine (creating more basic species).

- Key Techniques: A combination of separation techniques is used. Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC-HPLC) is the workhorse for quantifying aggregates and fragments. For higher resolution and to detect large aggregates that might be missed by SEC, Analytical Ultracentrifugation (AUC-SV) is often used as an orthogonal method. Charge variants are typically analyzed by Ion-Exchange Chromatography (IEX-HPLC) or Capillary Isoelectric Focusing (cIEF).

- Process-Related Impurities: These are substances that come from the manufacturing system itself.

- Key Impurities:

- Host Cell Proteins (HCPs): Residual proteins from the production cell line (e.g., Chinese Hamster Ovary cells).

- Host Cell DNA: Residual DNA from the production cell line.

- Leachables: Chemicals that may leach from manufacturing equipment (e.g., bags, tubing) into the product.

- Key Techniques: Highly sensitive immunoassays (e.g., HCP ELISA) and quantitative PCR (for DNA) are used to ensure these impurities are cleared to exceptionally low and safe levels.

A developer who discovers a new impurity in their product that is not present in the reference product faces a significant regulatory hurdle. They must either invest in re-developing their purification process to remove it or conduct extensive toxicological studies to prove that the new impurity is safe. Both options add considerable time and expense to the program. Therefore, meticulous process development aimed at matching the reference product’s purity and impurity profile from the very beginning is a critical risk-mitigation strategy.

Table 2: Key Analytical Techniques for Biosimilar Characterization

| Structural/Functional Category | Specific Attribute Measured | Key Analytical Technique(s) | Purpose in Similarity Assessment |

| Primary Structure | Amino Acid Sequence | Peptide Mapping LC-MS | Confirm identical sequence to reference. |

| Post-Translational Modifications | Glycosylation, Oxidation, Deamidation | HPAEC-PAD, LC-MS | Ensure critical modifications affecting function and immunogenicity are highly similar. |

| Higher-Order Structure | Folding, Conformation | CD, FTIR, DSC, HDX-MS | Verify that the 3D structure, essential for activity, is maintained and comparable. |

| Purity & Impurities | Aggregates, Fragments, Charge Variants | SEC-HPLC, IEX-HPLC, AUC-SV | Demonstrate a comparable purity profile and control of impurities linked to safety risks. |

| Biological Function | Target Binding, Potency | ELISA, SPR, Cell-Based Assays | Confirm that structural similarity translates to equivalent biological activity and mechanism of action. |

Part 5: The Statistician’s Role: Proving Similarity with Numbers

Generating vast amounts of analytical data is only half the battle. The ultimate challenge is to distill this complex information into a clear, statistically sound conclusion of “high similarity.” This is where biostatisticians play a pivotal role, applying rigorous methods to compare the biosimilar and reference products and provide regulators with the quantitative confidence needed for approval. The statistical framework, particularly the one outlined by the FDA, is a critical component of the regulatory submission.

The Gold Standard: Equivalence Testing for Tier 1 Attributes

For the most critical quality attributes (CQAs) in Tier 1, the FDA requires the highest level of statistical rigor: equivalence testing.54 This approach is fundamentally different from standard hypothesis testing. In a typical superiority trial, the goal is to reject the null hypothesis that there is

no difference between two products. In equivalence testing, the logic is flipped. The null hypothesis (H0) is that the products are not equivalent (i.e., the difference between them is unacceptably large). The goal is to gather enough evidence to reject this null hypothesis and conclude that the products are equivalent.

This is typically accomplished using a Two One-Sided Tests (TOST) procedure. The core of this test is the Equivalence Acceptance Criterion (EAC), which defines the “zone of equivalence.” To pass the test, the entire 90% confidence interval for the mean difference between the biosimilar and the reference product must fall completely within this pre-defined margin.

So, what is this margin? The FDA, in its guidance, has recommended a specific, though controversial, approach. The EAC is not a fixed number but is derived from the data itself. The recommended margin is ± 1.5 * σR, where σR is the standard deviation of the reference product, estimated from the lots tested in the comparability study.54

The choice of 1.5 as the multiplier was based on extensive FDA simulations and is intended to provide a reasonable balance between statistical power and the ability to detect meaningful differences. However, the reliance on the estimated variability of the reference product (denoted as SR or σ^R) introduces a significant strategic challenge. The width of the goalposts is determined by the performance of the reference product during the game.

This creates a precarious situation for the developer. If the specific lots of the reference product they manage to source happen to be unusually consistent and show very low variability, the calculated σ^R will be small. This, in turn, creates an extremely narrow equivalence margin (1.5 times a small number), making it statistically very difficult to pass the test, even if the biosimilar is truly an excellent match. A program could fail not because the biosimilar is different, but because of a statistical artifact arising from an unrepresentative sample of reference lots.

This underscores the critical importance of the reference product sourcing strategy. It is not enough to simply obtain the required number of lots. A developer must make every effort to source lots manufactured over a wide period to capture the true historical variability of the reference product, not just the low variability of a few recent, highly-controlled batches.41 Failure to do so introduces a major, and potentially fatal, risk into the statistical assessment of the most critical attributes.

Beyond Equivalence: The Quality Range Approach and Graphical Comparisons

For CQAs deemed to have a lower clinical risk, the statistical burden is lessened, though the need for scientific justification remains high.

For Tier 2 attributes, the FDA recommends the quality range approach.53 This method avoids the formal hypothesis testing of the equivalence approach. Instead, it focuses on characterizing the distribution of the reference product and ensuring the biosimilar fits within it.

- Methodology: A quality range is calculated from the reference product data, typically defined as the MeanR ± k*σR, where MeanR and σR are the mean and standard deviation of the reference product, and ‘k’ is a multiplier.

- Acceptance Criteria: The biosimilar demonstrates similarity if a pre-specified high percentage of its lot values (e.g., 90% or 95%) falls within this calculated range.

- The ‘k’ Factor: The choice of the multiplier ‘k’ is not fixed and must be “appropriately justified” by the sponsor. A ‘k’ value of 3 would encompass approximately 99.7% of the reference product data (assuming a normal distribution), setting a very high bar. A ‘k’ of 2 would be less stringent. The justification for the chosen ‘k’ will depend on the criticality of the attribute, the known impact of its variability, and the capability of the analytical method used to measure it.

For Tier 3 attributes, the lowest-risk category, the requirement for complex statistical analysis is waived in favor of raw data and graphical comparisons.51

- Methodology: This involves presenting the data for all tested lots of the biosimilar and reference product in clear, side-by-side formats. This can include summary tables of means and standard deviations, box plots, scatter plots, or overlayed chromatograms.

- Acceptance Criteria: There are no formal statistical criteria. Acceptance is based on a qualitative assessment by the regulatory reviewer that the data distributions are visually similar and that no concerning trends or differences are apparent.

- The Strategic Element: While seemingly simple, this approach is not without its challenges. The presentation of the data is critical. A well-constructed graph can tell a compelling story of similarity, while a poorly designed one can highlight minor, irrelevant differences and invite unnecessary questions from regulators. The developer must proactively use these graphical tools to build a visual narrative that supports their overall claim of high similarity.

Harmonizing the Numbers: Statistical Considerations in Global Development

The statistical complexity escalates significantly when a developer pursues a global approval strategy that requires bridging between US and EU reference products. A naive statistical plan that simply performs a series of separate pairwise comparisons is likely to be rejected by regulators for failing to address the fundamental problem of multiplicity.43

When multiple statistical tests are performed within the same study, the overall probability of making a Type I error (falsely concluding there is a difference when none exists) inflates. For a 3-way bridging study with at least three primary comparisons, if each is tested at a 5% significance level, the overall chance of at least one false positive result is much higher than 5%.

To address this, sponsors must use more sophisticated statistical methods that control the overall error rate. These can include:

- Multiplicity-Adjusted TOST (MATOST): This approach applies a statistical correction (like the Bonferroni or Holm method) to the p-values or confidence levels of the individual equivalence tests to ensure the overall study-wide error rate is controlled.

- Simultaneous Confidence Intervals: This method constructs a single confidence region that covers the differences for all comparisons simultaneously. If the entire region falls within the acceptance criteria, all comparisons are considered to have passed.

These advanced methods, while statistically sound, often require larger sample sizes to achieve the desired statistical power, which has direct implications for the cost and duration of the clinical pharmacology study.

The EMA, while not having the FDA’s formal tiered system for analytical attributes, does have well-established statistical expectations for clinical pharmacology studies. For pharmacokinetic parameters like AUC and Cmax, the EMA consistently requires an equivalence approach, with a standard, pre-defined acceptance margin of 80% to 125% for the ratio of the geometric means of the biosimilar to the reference product.12 This contrasts with the FDA’s data-driven EAC for analytical attributes and highlights another area where global statistical plans must be carefully designed to meet the specific requirements of each agency.

Ultimately, the statistical analysis plan is not a boilerplate document. It is a highly strategic component of the development program that must be tailored to the molecule, the global regulatory strategy, and the specific risks identified. Early and continuous engagement with expert biostatisticians who have direct experience in biosimilar development is not just recommended; it is essential for success.

Part 6: From Lab to Market: Challenges, Strategies, and Competitive Intelligence

Successfully navigating the scientific and statistical hurdles of analytical similarity is a monumental achievement, but it is only part of the journey. The path from a well-characterized molecule in a lab to a commercially viable product on the market is fraught with formidable operational challenges, competitive pressures, and strategic decisions that can make or break a program.

Navigating the Development Maze: Common Hurdles in Manufacturing and Scale-Up

The beautiful analytical data package that forms the foundation of a biosimilar submission is only as good as the manufacturing process that created the product. The technical challenge of designing a process that consistently produces a biologic with the desired CQAs, and then scaling that process from a small laboratory bench to massive commercial bioreactors, is one of the most underestimated hurdles in biosimilar development.69

The core challenge is managing manufacturing variability. As discussed, biologics are products of living cells, and a certain degree of lot-to-lot variation is inherent and expected.7 The goal of the biosimilar manufacturer is not to eliminate variability, but to understand it, control it, and demonstrate that the range of their product’s variability is comparable to that of the reference product. This requires an incredibly robust process development effort, using Quality by Design (QbD) principles to identify the Critical Process Parameters (CPPs)—such as temperature, pH, and nutrient feed rates—that impact the final product’s CQAs, and then implementing a control strategy to keep those CPPs within a validated range.

This challenge is amplified during process scale-up. The physics and biology inside a 50-liter development bioreactor are very different from those inside a 15,000-liter commercial-scale tank. Changes in factors like shear stress from mixing, oxygen transfer rates, and the removal of metabolic waste products can all impact how the cells grow and how they produce and modify the target protein. A process that works perfectly at the small scale can fail spectacularly at the large scale, producing a product with a different glycosylation profile or higher levels of aggregation.

This presents a critical risk to the entire program. Regulatory submissions are based on data from product manufactured using the final, locked-in commercial process. If the scaled-up process yields a product that is different from the material used for the initial analytical characterization and early clinical studies, the developer faces a nightmare scenario. They must conduct a whole new, costly, and time-consuming comparability exercise (as per ICH Q5E guidelines) to demonstrate that their own pre-scale-up and post-scale-up material is comparable, before they can even finalize the comparison to the reference product. Such a late-stage setback can delay a program by years and add tens of millions of dollars in unexpected costs.

To mitigate this risk, successful developers invest heavily in creating robust “scale-down” models—small-scale laboratory systems that accurately predict the performance of the commercial-scale process. This allows them to optimize and de-risk the process early, ensuring a smooth and predictable transition to full-scale manufacturing. For many companies, particularly those without extensive in-house biologics manufacturing experience, partnering with a specialized Contract Development and Manufacturing Organization (CDMO) can be a critical strategic decision to access the necessary expertise and infrastructure.69

Case Study Deep Dive: The Journey of Zarxio® (filgrastim-sndz) and Inflectra® (infliximab-dyyb)

To see these principles in action, we can examine the development journeys of two landmark biosimilars that paved the way in the United States. Their stories perfectly illustrate the core concept that the level of evidence required is directly proportional to the complexity of the molecule.

Zarxio® – The First US Biosimilar

In March 2015, Sandoz’s Zarxio® (filgrastim-sndz) became the first biosimilar approved by the FDA under the new BPCIA pathway.75 Its reference product, Amgen’s Neupogen® (filgrastim), is a recombinant granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) used to stimulate the production of white blood cells in cancer patients.

- The Molecule: Filgrastim is, in biologic terms, a relatively simple molecule. It is a single, non-glycosylated protein chain with a molecular weight of approximately 18.8 kDa. Its structure can be thoroughly and confidently characterized by modern analytical methods.

- The Development Program: As the very first product to go through the 351(k) process, Sandoz’s program was a pathfinder that helped shape the FDA’s regulatory thinking. The totality-of-the-evidence package was built on a massive analytical foundation. Sandoz used 22 different state-of-the-art analytical methods to compare 19 different quality attributes of Zarxio and Neupogen. This demonstrated a high degree of structural and functional similarity.

- The Clinical Confirmation: Because filgrastim has a well-understood mechanism of action and a readily measurable biological effect (increasing neutrophil counts), the clinical program could be streamlined. Instead of a large, lengthy efficacy trial, Sandoz conducted comparative clinical pharmacology studies in healthy volunteers. These studies demonstrated equivalent pharmacokinetics (PK) and, crucially, equivalent pharmacodynamics (PD), showing that Zarxio produced the same increase in absolute neutrophil count as Neupogen. This robust PK/PD data, built upon the strong analytical foundation, was sufficient to convince the FDA that there were no clinically meaningful differences. This allowed Zarxio to be approved for all five of Neupogen’s indications through extrapolation, without needing separate clinical trials for each one.

Inflectra® – A Complex Monoclonal Antibody

In April 2016, the FDA approved Inflectra® (infliximab-dyyb), developed by Celltrion, as the first biosimilar monoclonal antibody (mAb) in the US. Its reference product is Janssen’s Remicade® (infliximab), a cornerstone therapy for a range of autoimmune diseases like rheumatoid arthritis and Crohn’s disease.

- The Molecule: Infliximab represents a significant leap in complexity compared to filgrastim. It is a large, glycosylated, chimeric monoclonal antibody with a molecular weight of approximately 149 kDa. It has multiple mechanisms of action, including binding to its target (TNF-α) and engaging the immune system through its Fc region. This complexity and its potential for immunogenicity demanded a more extensive evidence package.

- The Development Program: The analytical package for Inflectra was even more comprehensive than for Zarxio. The FDA’s review documents show that Celltrion compared dozens of lots of Inflectra against dozens of lots of Remicade (e.g., 26 lots of the biosimilar vs. 36 lots of the reference for some tests) to characterize variability and demonstrate similarity across a vast array of attributes. The analytical assessment demonstrated that Inflectra has an identical primary amino acid sequence and highly similar higher-order structure and functional activities. Minor differences were detected, for example in the levels of certain charge variants and protein dimers, but these were thoroughly characterized and ultimately deemed by regulators not to be clinically meaningful.

- The Clinical Confirmation: Due to the molecule’s complexity and the potential for immunogenicity in patients, the FDA required more than just PK/PD data. The clinical program included two large, randomized, controlled clinical trials in sensitive patient populations: one in rheumatoid arthritis (PLANETRA) and one in ankylosing spondylitis (PLANETAS). These studies demonstrated equivalent efficacy and comparable safety and immunogenicity profiles to Remicade. This robust clinical data, built upon the analytical foundation, resolved any residual uncertainty and allowed for the extrapolation of approval to Remicade’s other inflammatory indications.

These two case studies perfectly illustrate the “one-size-does-not-fit-all” nature of biosimilar development. The strategic planning for any new biosimilar program must begin with a rigorous “complexity assessment” of the target molecule. This assessment will directly inform the likely scope, cost, and timeline of the required development program, forming a critical input for the business case and investment decision.

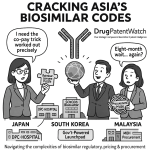

Cracking the Code: Using Patent Data and Services like DrugPatentWatch for Strategic Advantage

In the hyper-competitive biosimilar landscape, scientific excellence and regulatory acumen are necessary but not sufficient for success. The most successful companies are also master strategists, using every available tool to gain an edge. One of the most underutilized but powerful tools in the strategic arsenal is the patent literature. Often viewed simply as a legal minefield of intellectual property (IP) to be navigated, patents are, in fact, a rich and detailed roadmap into a competitor’s thinking, challenges, and solutions.

A biosimilar developer’s primary goal is to replicate the reference product. While the final composition of the marketed drug is public knowledge, the years of research, the failed experiments, and the specific problems that the originator had to solve to arrive at that final, stable, and effective formulation are proprietary secrets. Or are they?

Often, the originator’s formulation and process patents tell this very story. The “Background of the Invention” section of a patent frequently lays out the specific technical problem the inventors were trying to solve. The “Examples” section then provides a detailed, experiment-by-experiment account of how they solved it. Consider this hypothetical but realistic case study for a monoclonal antibody, “Stabilimab”:

- The Background: A formulation patent for Stabilimab begins by stating that high-concentration liquid formulations of this mAb are prone to aggregation and the formation of sub-visible particles, leading to unacceptable stability for subcutaneous injection. This is an immediate, invaluable piece of intelligence: the core challenge for this molecule is physical stability at high concentrations.

- The Examples: The patent then details several formulation experiments. Example 1 uses sucrose as a stabilizer. Example 2 uses arginine. Both show some improvement but still fail to meet the stability target. Example 3, however, uses a synergistic combination of sucrose and arginine, and the data presented shows a dramatic reduction in aggregation and particle formation.

- The Claims: The patent’s claims then protect this specific combination of excipients.

For a biosimilar developer, this patent is a goldmine. It tells them:

- The Critical Quality Attributes: The most critical attributes to control for this molecule are those related to aggregation and particle formation. This directly informs their CQA risk assessment and tells them where to focus their most sensitive analytical methods.

- The Originator’s Solution: The key to the originator’s success was the specific combination of sucrose and arginine.

- The Strategic Path Forward: The biosimilar developer now has a clear strategic choice. They can either attempt to challenge the validity of this patent or, more likely, they must develop a stable, high-concentration formulation that avoids the patented combination. This immediately directs their formulation development team to investigate alternative, non-infringing stabilizers like trehalose, proline, or other excipient combinations.

This process transforms the developer from a reactive copier into a proactive, informed strategist. However, manually sifting through dense patent landscapes for dozens of potential targets is a monumental task. This is where specialized competitive intelligence services like DrugPatentWatch become indispensable. These platforms provide integrated, searchable databases of drug patents, patent expiration dates, ongoing litigation, regulatory exclusivities, and detailed patent family information.

By leveraging a service like DrugPatentWatch, a company can:

- Conduct Efficient Freedom-to-Operate (FTO) Analysis: Quickly identify the entire patent estate surrounding a target biologic, including not just the core composition of matter patent but also the “patent thicket” of secondary patents on formulations, manufacturing methods, and uses.

- Monitor Competitor Activity: Track the patenting strategies of both the originator and other biosimilar competitors to anticipate their moves and identify emerging threats or opportunities.

- Accelerate Technical Development: Systematically mine the patent literature for the kind of technical intelligence described in the Stabilimab case study, using a competitor’s own R&D history to de-risk and accelerate their own development program.

In the world of biosimilars, where speed to market and cost of development are paramount, the ability to turn a competitor’s intellectual property into your own strategic roadmap is not just an advantage; it is a necessity.

Part 7: The Horizon: The Future of Biosimilar Regulation and Development

The regulatory landscape for biosimilars is not static. It is a dynamic and rapidly evolving field, shaped by accumulating scientific experience, technological advancements, and shifting market realities. For stakeholders planning for the future, it is crucial to understand the key trends that are redefining the path to market, from the evolving concept of interchangeability in the US to the global push for regulatory harmonization and the disruptive potential of new technologies.

The Interchangeability Question: Evolving Standards and Market Impact

A unique feature of the US biosimilar pathway is the designation of “interchangeability.” An interchangeable product is a biosimilar that has met additional statutory requirements, allowing it to be substituted for the reference product at the pharmacy level without the direct intervention of the prescribing physician, much like a generic drug (subject to state pharmacy laws).35

Historically, the primary additional requirement to achieve this designation was a switching study. This was a clinical trial designed to demonstrate that the risk in terms of safety or diminished efficacy of alternating or switching between the biosimilar and the reference product is not greater than the risk of using the reference product without such a switch.40 These studies were complex, costly, and time-consuming, creating a high bar for developers and a significant incentive—a period of market exclusivity for the first interchangeable biosimilar to be approved.

However, the ground has shifted dramatically. In a landmark move in June 2024, the FDA issued new draft guidance that signals a fundamental change in its thinking. Based on a decade of experience with biosimilars and the agency’s own research—which found no difference in safety outcomes between patients who switched and those who did not—the FDA has proposed that switching studies will generally no longer be needed to demonstrate interchangeability.38 The agency’s position is that today’s advanced analytical tools are more precise and sensitive at evaluating product structure and function than clinical switching studies.

This is a seismic shift with profound market implications.

- Lowering the Barrier: By removing the most burdensome requirement, the FDA is dramatically lowering the cost and time needed to achieve an interchangeability designation. This makes the designation far more accessible to a greater number of developers.

- Blurring the Lines: The original intent of the interchangeability designation was to build confidence among pharmacists and patients. However, it inadvertently created a perception of a “two-tier” system, where interchangeable products were seen as superior to “mere” biosimilars—a perception the FDA itself has stated is not scientifically supported.38 By making the designation easier to obtain and even proposing to remove the term “interchangeable” from product labeling, the FDA appears to be actively working to blur this distinction.

- Shifting Competitive Dynamics: The “first interchangeable” exclusivity may become less of a strategic prize if multiple competitors can achieve the designation in rapid succession. Instead of being a key differentiator, interchangeability may become “table stakes”—a minimum requirement for any biosimilar that will be dispensed through retail pharmacies.

Companies currently developing biosimilars for the US market must urgently re-evaluate their strategies in light of this new paradigm. The decision of whether to pursue interchangeability, once a major strategic and financial crossroads, has been fundamentally altered.

The Drive for Global Harmonization: A Path to Streamlined Development?

One of the most significant sources of cost and inefficiency in biosimilar development is the patchwork of divergent regulatory requirements across the globe. A company wishing to market a biosimilar in the US, Europe, Japan, and Canada may have to contend with different rules regarding:

- Reference Product Sourcing: The need for costly and complex bridging studies to link data generated with reference products from different regions.

- Animal Studies: The requirement in some countries for comparative animal toxicology studies, which are now widely considered by the FDA, EMA, and WHO to be scientifically unnecessary and add little value.45

- Clinical Data in Local Populations: The demand from some regulators for clinical trial data generated specifically within their local ethnic populations.

These duplicative and often scientifically questionable requirements add hundreds of millions of dollars to global development costs and can delay patient access to affordable medicines by years.32 Consequently, there is a strong and growing push from industry, patient advocates, and scientific bodies for the

global harmonization of biosimilar regulations.86

The ultimate vision is a system where a single, global development program, using a single, globally accepted reference product standard, could generate a data package suitable for submission in all major markets. While full harmonization remains a long-term goal, significant progress is being made on a number of fronts:

- There is a growing global consensus that dedicated animal toxicology studies are generally not needed.

- Major agencies like the EMA and Health Canada have shown flexibility in accepting data generated with non-local reference products, provided a strong scientific bridge is established.

- The WHO continues to publish guidelines that provide a scientific foundation for regulatory convergence among its member states.

However, significant barriers remain. National regulatory agencies are sovereign bodies, often reluctant to cede their authority or fully accept the decisions of others. Differing healthcare systems and policy priorities also contribute to the divergence.

For developers, the path forward is twofold. In the short term, they must be expert navigators of the current complex and fragmented global landscape. In the long term, they can be architects of a more rational system. By participating in scientific forums, contributing to the global evidence base, and supporting the advocacy efforts of industry associations, companies can help shape a future where redundant studies are eliminated, development is streamlined, and the benefits of biosimilar competition can be realized more quickly and efficiently for patients everywhere.

Looking Ahead: The Role of AI, New Analytical Tech, and the End of Confirmatory Efficacy Trials?

The trajectory of biosimilar regulation is clear: a continuous and accelerating shift in the evidentiary burden away from costly clinical trials and toward the foundational analytical assessment.32 This trend is powered by relentless technological advancement, and the future of biosimilar development will be defined by the tools that make this shift possible.

- New Analytical Technologies: The evolution of analytical science did not stop with the techniques described in this report. New and more sensitive methods for characterizing protein structure and function are constantly emerging. These will allow for an even deeper and more precise comparison between biosimilars and their reference products, further increasing the confidence that can be derived from the analytical package.

- Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning: The sheer volume and complexity of data generated during an analytical similarity assessment are staggering. A single mass spectrometry run can produce gigabytes of data. AI and machine learning algorithms are perfectly suited to analyze these vast, multi-dimensional datasets. They can identify subtle patterns of similarity or difference that are invisible to the human eye, predict which process parameters are most likely to impact critical quality attributes, and help optimize manufacturing processes to more precisely match a target profile. The biosimilar company of the future will likely be as much a data science company as a biotechnology company.

- The End of Confirmatory Efficacy Trials? This technological progress leads to a provocative but logical question: are we approaching a future where, for most biosimilars, the confirmatory clinical efficacy trial becomes obsolete?. Industry groups and many regulatory scientists argue that we are already there for many products. Their argument is compelling: if state-of-the-art analytics demonstrate that a biosimilar is structurally and functionally indistinguishable from its reference product, and a clinical pharmacology study confirms that it has identical PK and PD profiles, what residual uncertainty is a large, expensive, and relatively insensitive clinical efficacy trial meant to resolve?.32

The EMA is already formally exploring this path with its “tailored clinical approach”. The FDA has waived the need for efficacy trials for simpler biologics like filgrastim and insulin where a sensitive PD marker exists. The logical next step is to extend this principle to more complex molecules as our analytical confidence grows.

This streamlined future would be transformative. A typical biosimilar clinical efficacy trial can account for more than half of the total development cost, which can range from $100 million to $300 million.32 Eliminating this requirement would dramatically lower the cost of entry, spurring competition for a wider range of biologic medicines and accelerating patient access to more affordable treatments. This is not about lowering standards; it is about raising them—relying on the most sensitive and scientifically rigorous tools available to ensure the quality, safety, and efficacy of these vital medicines. The companies that will thrive in this future are those that embrace this technological and regulatory evolution, building their core competencies not just in running clinical trials, but in mastering the science of similarity itself.

Key Takeaways

- Analytical Similarity is the Foundation: The entire biosimilar approval paradigm rests on the “totality-of-the-evidence” pyramid, with a comprehensive analytical similarity assessment forming the broad, essential base. A strong analytical package reduces residual uncertainty, thereby minimizing the need for extensive and costly clinical trials.

- CQAs and the Tiered Approach are Strategic: Identifying Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs) and justifying their classification within the FDA’s tiered framework (or the EMA’s holistic approach) is a key strategic activity. It allows for the efficient allocation of resources, focusing the most rigorous statistical methods (like equivalence testing) on the attributes that pose the highest clinical risk.

- Global Development Requires Navigating Nuance: While the FDA and EMA share core principles, their specific definitions, requirements for reference product sourcing (bridging studies), and stances on interchangeability differ significantly. A successful global strategy requires a deep understanding of these nuances and a development plan designed to satisfy multiple regulatory bodies.

- Manufacturing and Analytical Prowess are Competitive Advantages: The ability to develop a robust, consistent, and scalable manufacturing process is critical. Success is determined not just in the clinic, but in the process development lab. Investing in state-of-the-art analytical technologies is a strategic imperative, as these tools provide the high-quality data needed to build a convincing case for similarity and gain regulatory confidence.

- Patent Intelligence is a Strategic Tool: Services like DrugPatentWatch transform patent databases from legal hurdles into sources of competitive intelligence. Analyzing an originator’s patents can reveal their key development challenges and formulation solutions, providing a roadmap that informs the biosimilar developer’s own CQA assessment and strategy.

- The Future is Streamlined and Data-Driven: The regulatory landscape is rapidly evolving towards greater reliance on analytical data and less on confirmatory clinical trials. Trends like the FDA’s revised stance on interchangeability and the global push for harmonization will lower development barriers. Future success will belong to companies that embrace new technologies like AI and build their core competencies around advanced analytics and data science.

Conclusion

The regulatory pathway for biosimilars represents one of the most significant shifts in pharmaceutical development and oversight in a generation. It moves away from the traditional, clinically-focused paradigm toward a new model founded on deep analytical science and the principle of similarity. Successfully navigating this complex landscape requires more than just technical execution; it demands a sophisticated, integrated strategy that blends cutting-edge science, astute regulatory navigation, and sharp competitive intelligence.

The analytical similarity assessment is the undisputed centerpiece of this strategy. It is not a perfunctory quality control exercise but the foundational evidence upon which the entire value proposition of a biosimilar—safe, effective, and more affordable—is built. From identifying and tiering Critical Quality Attributes to deploying state-of-the-art characterization techniques and applying rigorous statistical analyses, every step is an opportunity to build confidence, mitigate risk, and accelerate the path to market.

As the global biosimilar market continues its exponential growth, driven by the dual engines of patent expiries and the urgent need for healthcare cost containment, the challenges and opportunities will only intensify. Developers will face a complex maze of global regulations, formidable manufacturing hurdles, and fierce competition. Yet, the path forward is becoming clearer. A future defined by greater regulatory harmonization, enabled by ever-more powerful analytical technologies, and streamlined by a science-based reduction in clinical data requirements is on the horizon. The companies that will thrive in this new era are those that understand that in the world of biosimilars, proving similarity is the ultimate measure of success.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)