Executive Summary

The landscape of generic pharmaceuticals in the United States is a battlefield sculpted by a single piece of landmark legislation: the Hatch-Waxman Act. For nearly four decades, this intricate framework has governed the delicate dance between brand-name innovation and generic competition. At the heart of this system lies the Paragraph IV certification—a bold declaration by a generic manufacturer that a brand’s patent is invalid, unenforceable, or will not be infringed. This act, in itself a form of “artificial” patent infringement, triggers a high-stakes legal and commercial confrontation that has come to define modern pharmaceutical strategy.

This report provides a comprehensive analysis of the landmark court decisions that have shaped this battlefield. We will journey from the legislative origins of the Hatch–Waxman Act to the modern complexities of multi-forum litigation, dissecting the pivotal precedents that every generic manufacturer must understand to survive and thrive. We will explore how the Paragraph IV challenge evolved from a novel legal pathway into the central pillar of generic business strategy, a transformation catalyzed by the watershed success in the Barr v. Lilly (Prozac) case, which proved that even the most formidable blockbuster drugs were vulnerable.

The analysis delves into the strategic fallout from the Supreme Court’s seismic shift on settlement agreements in FTC v. Actavis. This decision dismantled the old “scope of the patent” defense and subjected “pay-for-delay” deals to rigorous antitrust scrutiny, fundamentally altering the risk calculus of litigation and negotiation. We will examine how lower courts have since expanded the definition of a “payment” to include non-monetary concessions like “no-authorized-generic” agreements, demanding a new level of antitrust awareness in every settlement discussion.

Furthermore, this report charts the treacherous terrain of “skinny labeling,” a critical strategy for navigating the dense “patent thickets” that now protect most major drugs. While the Supreme Court’s decision in Caraco v. Novo Nordisk empowered generics to challenge inaccurate patent listings, the Federal Circuit’s more recent ruling in GSK v. Teva has created profound new risks. The finding of induced infringement based on marketing materials, even with a properly “carved-out” label, has transformed skinny labeling from a purely regulatory tactic into an enterprise-wide compliance imperative.

Finally, we will explore the modern strategic toolkit, including the use of Inter Partes Review (IPR) to create a “two-front war” against brand patents and the indispensable role of competitive intelligence platforms like DrugPatentWatch in architecting a data-driven portfolio strategy. The lessons are clear: success in the contemporary generic market is no longer a matter of mere manufacturing efficiency or speed. It requires a sophisticated, multi-disciplinary approach that seamlessly integrates legal acumen, regulatory savvy, and commercial strategy. This report serves as the definitive playbook for mastering that integration and turning legal precedent into market dominance.

Part I: The Hatch-Waxman Blueprint: Understanding the Rules of Engagement

1. The Genesis of Modern Generic Competition: The Hatch-Waxman Act

To truly grasp the strategic nuances of Paragraph IV litigation, one must first understand the world that existed before it. The pre-1984 pharmaceutical landscape was a fundamentally different, and for generic manufacturers, a largely inhospitable environment. The path to market was not just difficult; it was, in many ways, designed to be nearly impossible. At that time, generic drugs accounted for a mere 19% of all prescriptions filled in the United States, a stark contrast to the 90% they represent today.1 This was no accident. It was the direct result of a regulatory and legal framework that heavily favored incumbent brand-name manufacturers.

The primary obstacle was the drug approval process itself. Before the Hatch-Waxman Act, any company seeking to market a generic version of a drug had to submit a full New Drug Application (NDA) to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). This meant they were required to conduct their own, independent clinical trials to establish the safety and efficacy of their product, even though the active ingredient was identical to a drug that had already undergone years of rigorous testing. This requirement to replicate costly and time-consuming trials created a massive economic barrier, rendering the development of most generics financially unviable.3

Compounding this problem was a critical legal catch-22 rooted in patent law. The very act of conducting the research and development necessary to prepare an FDA submission—including the bioequivalence studies that would later become the cornerstone of the generic approval process—was considered an act of patent infringement.3 This meant a generic company could be sued and face significant damages long before it ever had a product to sell. Innovator firms could effectively block generic development from the very beginning, ensuring their monopoly extended well beyond the intended patent term.

Recognizing that this system was failing to balance innovation with public access to affordable medicine, Congress stepped in. The result was the Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984, a piece of legislation so transformative it is almost universally known by the names of its sponsors, Senator Orrin Hatch and Representative Henry Waxman.1 The Hatch-Waxman Act was a grand compromise, a carefully constructed piece of legislative architecture designed to serve the competing interests of both the brand and generic industries.3

For the generic industry, the benefits were revolutionary. The Act created the Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) pathway, a streamlined process that stands as the foundation of the modern generic market.1 Under the ANDA process, a generic manufacturer no longer needed to conduct its own safety and efficacy trials. Instead, it could rely on the clinical data of the innovator’s approved drug (the “reference listed drug” or RLD) by simply demonstrating that its product was bioequivalent—that is, it delivered the same amount of active ingredient to the bloodstream over the same period of time.8 This single change dramatically lowered the cost and time required to bring a generic to market. Simultaneously, the Act created a statutory “safe harbor” under 35 U.S.C. § 271(e)(1), which explicitly exempted activities “reasonably related to the development and submission of information under a Federal law which regulates the manufacture, use, or sale of drugs” from being considered patent infringement.1 This provision, broadly interpreted by the Supreme Court, eliminated the legal catch-22 and allowed generics to develop their products without fear of being sued before they could even file for approval.

For the brand-name industry, the compromise offered significant new protections to compensate for the accelerated generic competition. The Act established provisions for patent term extension, allowing innovators to recapture a portion of the patent life lost during the lengthy FDA regulatory review process.9 It also codified various periods of regulatory exclusivity, which are distinct from patent protection and are administered by the FDA. The most significant of these is the five-year New Chemical Entity (NCE) exclusivity, which prevents the FDA from even accepting a generic application for four years after the brand drug’s approval.8 These exclusivities run concurrently with patent protection and provide a guaranteed period of market monopoly, regardless of the underlying patent status.

Ultimately, the Hatch-Waxman Act did more than just create a new regulatory pathway; it fundamentally re-engineered the nature of pharmaceutical patent disputes. By creating what is known as an “artificial” act of infringement—the very act of filing a Paragraph IV certification—the legislation shifted the entire timeline of patent litigation.8 No longer would a brand company have to wait for a generic to launch and start causing commercial harm to file a lawsuit. Instead, the patent fight could be initiated, and often resolved, before the generic product ever reached a single patient. This transformation of patent litigation from a reactive, post-launch defense into a predictable, pre-launch strategic phase is the essential context for understanding every landmark decision that has followed. It created the structured battlefield upon which all modern generic strategies are planned and executed.

2. The Core Mechanics: The Orange Book, Patent Certifications, and the 30-Month Stay

The intricate machinery of the Hatch-Waxman Act operates through a set of core components that every generic strategist must master. These are the gears and levers of the system: the Orange Book, the four patent certifications, the notice letter process, and the automatic 30-month stay. Understanding how these elements interact is fundamental to navigating the path to market.

At the center of this universe is the FDA’s publication, “Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations,” known colloquially as the Orange Book.1 This unassuming government document is, in effect, the official map of the patent landscape for small-molecule drugs. When a brand company submits an NDA, it is required to list all patents that claim the drug substance (the active ingredient), the drug product (the formulation or composition), or an approved method of using the drug.8 The FDA publishes this information, creating a transparent, centralized repository that serves as the starting point for any generic challenge.

When a generic manufacturer files an ANDA, it must address every single patent listed in the Orange Book for the reference drug. It does this by making one of four possible certifications for each patent 8:

- Paragraph I Certification: A statement that no patent information has been filed with the FDA.

- Paragraph II Certification: A statement that the patent has already expired.

- Paragraph III Certification: A statement that the generic company will wait to market its product until the date the patent expires.

- Paragraph IV (PIV) Certification: A bold assertion that the listed patent is invalid, unenforceable, or will not be infringed by the manufacture, use, or sale of the proposed generic drug.7

While the first three certifications are straightforward acknowledgments of the brand’s patent rights, the Paragraph IV certification is a direct challenge. It is the legal mechanism that signals a generic’s intent to enter the market before a patent expires, and it is the act that sets the entire litigation process in motion.

Once an ANDA containing a PIV certification is filed and the FDA acknowledges it as substantially complete for review, a strict timeline begins. The generic applicant has 20 days from that FDA acknowledgment to send a formal “notice letter” to both the brand NDA holder and the patent owner.7 This is no mere formality. The notice letter must contain a detailed statement of the factual and legal bases for the generic’s belief that the patent is invalid or not infringed. While these positions are not binding in the subsequent litigation, they must be made in good faith and be thoroughly vetted, as a failure to meet this standard can result in penalties, such as the awarding of attorney’s fees to the brand plaintiff.

Upon receiving this notice letter, the clock starts for the brand company. It has a 45-day window to file a patent infringement lawsuit against the generic applicant.8 This 45-day deadline is critical because of what it triggers: the 30-month stay of regulatory approval.

If the brand files suit within this 45-day period, the FDA is automatically prohibited from granting final approval to the generic’s ANDA for a period of 30 months from the date the notice letter was received, or until a district court rules in the generic’s favor, whichever comes first.7 This provision was designed to give the parties a reasonable amount of time to litigate their patent dispute in court before the generic product could enter the market.10 It provides the brand with a significant procedural protection, a period of continued market exclusivity to resolve the patent challenge without facing immediate commercial harm.7

However, a common misconception is that this 30-month stay is the primary factor dictating when a generic will ultimately launch. While it certainly defines the earliest possible launch date in a litigated scenario, empirical data reveals a more complex reality. One comprehensive study of 46 generic drugs found that there was a median gap of 3.2 years between the expiration of the 30-month stay and the actual launch of the generic product. Another analysis confirmed this, noting that nearly all stay periods expired several years before the generic launch date, suggesting they did not directly delay entry.

This gap exists because the 30-month stay is often just the beginning of the story. The initial litigation may take longer than 30 months to resolve, especially with appeals. More importantly, brand companies often employ strategies like building “patent thickets,” where they list additional patents on the drug after the initial ANDA has been filed. While these later-listed patents do not trigger a new 30-month stay, they still represent legal hurdles that must be cleared before a generic can safely launch. Other factors, such as complex manufacturing requirements, settlement agreements that stipulate a specific entry date, or the remaining life of other, unchallenged patents, play a far more significant role in determining the final launch timeline.

Therefore, for a generic strategist, the expiration of the 30-month stay should not be viewed as a green light to launch. Instead, it is a critical inflection point. It marks the moment when the calculus of risk changes dramatically. The generic can now choose to launch “at risk,” betting that it will ultimately prevail in the ongoing litigation. This option provides immense leverage in settlement negotiations, as the brand now faces the prospect of immediate and irreversible market share loss. The end of the stay transforms the dynamic from a purely legal dispute into a high-stakes commercial negotiation, but the decision to actually launch depends on a much broader strategic assessment of the entire patent portfolio, the strength of the legal case, and the company’s tolerance for risk.

3. The Ultimate Prize: The 180-Day Exclusivity Period

If the Paragraph IV certification is the sword a generic manufacturer wields to challenge a brand’s patent, then the 180-day market exclusivity period is the treasure it seeks to win. This powerful incentive, embedded within the Hatch-Waxman Act, is the primary economic engine driving patent challenges and is arguably the most valuable asset in the generic pharmaceutical industry.2

The concept is straightforward but its impact is profound. The law grants a six-month period of marketing exclusivity to the “first-to-file” (FTF) a “substantially complete” ANDA containing a Paragraph IV certification against at least one Orange Book-listed patent for a given drug.2 During this 180-day period, the FDA is barred from approving any

subsequent ANDAs for the same drug product.7 This effectively creates a duopoly in the market: the brand-name drug and the single, first-to-file generic.

The financial value of this temporary duopoly cannot be overstated. In a fully competitive market with multiple generic entrants, prices can plummet by 80-95% compared to the brand price as companies engage in a “race to the bottom”.7 However, during the 180-day exclusivity period, the FTF generic faces no other generic competition. This unique market position allows the FTF to price its product at only a modest discount to the brand—often just 15-25% lower—while still rapidly capturing a dominant share of the market.7 The result is a period of exceptionally high profit margins. For many blockbuster drugs, this six-month window can generate hundreds of millions of dollars in revenue. It is for this reason that industry analysts estimate that a generic company often makes 60% to 80% of its total profit on a given product during this exclusive period.

The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) estimates that pay-for-delay settlements, a strategic maneuver deeply intertwined with the value of the 180-day exclusivity, cost consumers $3.5 billion per year in the form of increased costs for prescription drugs.

This immense financial prize was intended by Congress to serve a clear public policy goal: to encourage generics to invest the significant time and resources required to litigate and invalidate weak or improperly listed patents, thereby bringing lower-cost medicines to the public sooner.2 For many years, it worked precisely as intended, spurring challenges to some of the most widely used medicines, including atorvastatin (Lipitor), omeprazole (Prilosec), and gabapentin (Neurontin).

However, the very value of the 180-day exclusivity also created incentives for strategic behavior that could, paradoxically, delay rather than accelerate competition. An early interpretation of the law granted the exclusivity to the FTF challenger regardless of whether they actually won the patent litigation or even launched their product. This created a critical loophole. A brand-name manufacturer, facing a patent challenge from an FTF generic, could simply “buy off” the challenger. In such a “pay-for-delay” settlement, the brand would pay the FTF generic to drop its patent challenge and agree to delay its market entry. Because the FTF generic still technically held the rights to the 180-day exclusivity, no other generic company could get its ANDA approved and enter the market until that first filer’s exclusivity was either triggered by a launch or forfeited.22

This practice, known as “exclusivity parking,” effectively allowed the brand and the first generic challenger to collude, using the very mechanism designed to foster competition as a shield to block it. A subsequent generic challenger could win its own patent litigation but would still be stuck in a queue, unable to launch until the “parked” exclusivity of the first filer was resolved. This gaming of the system directly undermined the core purpose of the Hatch-Waxman Act.

This strategic manipulation became so prevalent that it prompted a major legislative overhaul. The Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act of 2003 (MMA) amended the Hatch-Waxman Act to introduce a series of “forfeiture” provisions.6 These provisions outline specific events that would cause an FTF generic to lose its eligibility for the 180-day exclusivity, such as failing to market the drug within a certain timeframe after approval or entering into an anticompetitive settlement agreement. If a first filer forfeits its exclusivity, the prize is extinguished; it does not pass to the next generic in line.

The introduction of these forfeiture provisions has made the strategic landscape surrounding the 180-day exclusivity vastly more complex. For a generic manufacturer, simply being the first to file is no longer enough. Now, a company must not only navigate the patent litigation successfully but also carefully manage its commercial launch and settlement strategies to avoid triggering a forfeiture event. Understanding the intricate rules of earning, maintaining, and potentially forfeiting this prized asset is now just as critical as winning the underlying patent case.

Part II: Lessons from the Courthouse: Landmark Decisions and Their Strategic Fallout

The theoretical framework of the Hatch-Waxman Act provides the rules of the game, but it is in the courtroom where those rules are tested, interpreted, and ultimately given their strategic meaning. Over the past several decades, a series of landmark court decisions have profoundly shaped the Paragraph IV landscape, turning abstract statutory language into hard-and-fast lessons for generic manufacturers. These cases are not mere historical footnotes; they are the foundational pillars of modern generic strategy.

4. The Shot Heard ‘Round the Industry: Barr v. Lilly (Prozac) and the Dawn of the Blockbuster Challenge

Before the turn of the millennium, the Paragraph IV pathway was still a largely unproven strategy. While theoretically powerful, the idea of a smaller generic company taking on a pharmaceutical giant over its flagship, multi-billion-dollar product seemed a daunting, if not reckless, proposition. That perception changed forever with one case: the challenge to Eli Lilly’s blockbuster antidepressant, Prozac® (fluoxetine). This case was the proof-of-concept that transformed the Paragraph IV challenge from a legal curiosity into a core, aggressive, and incredibly lucrative business model.

In 1996, Barr Laboratories, a generic manufacturer, identified Prozac as a prime target. The drug was a cultural phenomenon and a commercial juggernaut, but Barr’s analysis suggested its patent protection was vulnerable. Barr took the plunge, filing an ANDA with a Paragraph IV certification that asserted Lilly’s patents were either invalid or would not be infringed by its generic version. What followed was a grueling, five-year legal battle. The fight culminated in August 2000, when the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit handed Barr a stunning victory, vacating a lower court decision and invalidating one of Lilly’s key patents protecting the drug.

The commercial fallout was immediate and brutal for Lilly. When Barr launched its generic fluoxetine in August 2001, after the expiration of the main compound patent, the market erosion was unlike anything the industry had seen before. Within a mere two months, Barr’s generic had seized an astonishing 65% of the Prozac market share. By the time Barr’s 180-day exclusivity period ended, Prozac had lost 82% of its total prescriptions to the generic, retaining only a 16% share of the market it had once completely dominated.

For Barr, the victory was a financial windfall that validated its high-risk strategy. In the eleven months following its launch, sales of generic fluoxetine reached $367.5 million, accounting for nearly a third of the company’s total product sales. During its final quarter of 2001, with the full benefit of its generic monopoly, Barr’s gross profit margin nearly doubled, rocketing from 16.8% to 28.7%. The impact was felt on Wall Street as well; in the month the favorable court decision was announced, Barr’s stock price surged by over 35%.

Strategic Lesson 1: The P-IV Pathway is a Viable, High-Reward Strategy for Blockbuster Drugs.

The Prozac case did more than just make Barr Laboratories a lot of money; it sent a shockwave through the entire pharmaceutical industry. It provided a tangible, data-driven demonstration that the Paragraph IV pathway was not just a theoretical possibility but a potent and viable weapon. The lesson was clear and undeniable: no drug, no matter how large or profitable, was invincible.

Before this case, the calculus for challenging a blockbuster was fraught with uncertainty. The legal costs were immense, the litigation risk was high, and the potential return on investment was largely theoretical. Barr’s success provided the hard data that every generic executive needed. It proved that a successful challenge could result in a massive and rapid capture of market share, a dramatic and immediate increase in corporate profitability, and a significant boost to shareholder value.

This proof-of-concept directly catalyzed the explosion in Paragraph IV litigation that followed. The industry saw that the potential ROI was simply too high to ignore. The number of PIV cases filed annually began a steady climb, growing from 77 in 2005 to a staggering 402 by 2015. The Prozac decision single-handedly legitimized the high-risk, high-reward PIV business model, embedding it as a central strategy for growth and value creation within the generic pharmaceutical sector.

5. The Settlement Conundrum: Navigating Antitrust in a Post-Actavis World

While the Prozac case demonstrated the immense upside of litigating a Paragraph IV challenge to victory, the reality is that the vast majority of these cases never reach a final court decision. Like most complex commercial disputes, they end in settlement. For years, these settlements operated in a legal grey area, but a series of landmark cases, culminating in a Supreme Court decision, has dragged them into the harsh light of antitrust scrutiny, fundamentally reshaping how these deals are negotiated.

5.1 The Old Regime: The “Scope of the Patent” Test

In the early days of Paragraph IV litigation, the prevailing legal standard for evaluating settlements was highly deferential to the patent holder. The key case that defined this era was Valley Drug Co. v. Geneva Pharmaceuticals, Inc., a 2003 decision from the Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals. The case involved settlement agreements in which Abbott Laboratories paid generic challengers to delay the launch of a generic version of its drug, Hytrin.

The plaintiffs, a class of drug purchasers, argued that these “pay-for-delay” agreements were per se illegal market allocation schemes. The court, however, rejected this view. It established what became known as the “scope of the patent” test. The court’s reasoning was that a patent grants its owner a lawful right to exclude others from the market. Therefore, an agreement in which the patent holder pays a potential infringer to stay off the market is not inherently anticompetitive, as long as the period of exclusion agreed to in the settlement does not extend beyond the patent’s expiration date. In other words, if the brand could have potentially excluded the generic for the full term of the patent through successful litigation, then paying the generic to stay out for a shorter period was within the “scope of the patent” and generally immune from antitrust attack. Crucially, the court held that the mere fact that the patent was later found to be invalid did not retroactively make the settlement illegal.

Strategic Lesson 2: (Historical Context) Early settlements were viewed through the lens of patent rights, providing a wide berth for brands to pay for delay.

This legal framework created what might be called a “golden age” for pay-for-delay settlements. It gave brand companies enormous latitude to resolve patent challenges by sharing a portion of their monopoly profits with the first-to-file generic challenger. This was a win-win for the settling parties: the brand eliminated the risk of losing its patent and facing early competition, while the generic received a guaranteed, risk-free payment that was often more lucrative than what it could have earned by launching at risk. The only loser was the consumer, who was denied the benefits of earlier generic competition. This legal environment directly led to the rise of “exclusivity parking,” and the number of settlements involving a payment from the brand to the generic rose dramatically throughout the 2000s.

5.2 The Supreme Court Intervenes: FTC v. Actavis and the Rule of Reason

The “scope of the patent” test created a deep split among the circuit courts and drew the intense scrutiny of the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), which viewed these settlements as blatant anticompetitive agreements. The issue finally came to a head in 2013 with the landmark Supreme Court case, FTC v. Actavis, Inc..28

The case centered on a settlement agreement concerning the drug AndroGel. The brand manufacturer, Solvay, paid several generic manufacturers millions of dollars to drop their patent challenges and keep their generic versions off the market until 2015, years before the patent was set to expire.28 The FTC sued, arguing the deal was an illegal restraint of trade.

In a seismic decision, the Supreme Court rejected the “scope of the patent” test. The Court held that so-called “reverse payment” settlements are not immune from antitrust law simply because the agreed-upon delay falls within the patent’s term. Instead, these agreements must be evaluated under the traditional antitrust “rule of reason”.28

The Court’s logic was grounded in economic reality. A patent does not confer an absolute right to exclude; it confers a right to try to exclude, a right that is contingent on the patent’s validity and infringement. A patent challenge puts that right at risk. The Court reasoned that a large and “unjustified” payment from the patent holder to the challenger is a strong indicator that both parties are seeking to avoid that risk. The payment suggests that the patent holder has doubts about the strength of its patent and is willing to share its monopoly profits to avoid having it tested in court.28 In the Court’s view, such a payment can represent “the sharing of monopoly profits between a patentee and a would-be generic competitor” to the detriment of consumers.

Strategic Lesson 3: The nature of settlement negotiations has fundamentally changed. Any transfer of value from the brand to the generic is now a potential antitrust red flag.

The Actavis decision did not declare all reverse payments to be illegal per se. Instead, it shifted the entire legal framework from a patent-centric analysis to a competition-centric one. The critical question for any settlement is no longer, “Does the delay exceed the patent term?” It is now, “Is there a large and unjustified payment from the brand to the generic, the purpose of which is to keep the generic off the market?”

This shift created significant legal uncertainty, as the Supreme Court deliberately left it to the lower courts to structure the specific application of the rule of reason analysis. This forces both brand and generic companies to approach settlement negotiations with extreme caution. Any transfer of value from the brand to the generic must be meticulously documented and justified by legitimate, pro-competitive reasons, such as compensation for saved litigation costs or payments for other services at fair market value. The days of the simple, large cash payment in exchange for market delay were over. An FTC report issued after the decision showed a substantial decrease in potential pay-for-delay deals, indicating the ruling’s immediate chilling effect. For generic companies, this meant that the easy payday of a large, risk-free cash settlement was largely a thing of the past. The new strategic focus in settlements had to shift towards negotiating favorable, early entry dates or other pro-competitive terms that could withstand antitrust scrutiny.

5.3 What is a “Payment”? King Drug Co. and No-Authorized-Generic Agreements

In the wake of Actavis, which focused on direct monetary payments, a new question arose: what else constitutes a “payment”? Brand and generic companies began to structure settlements around non-monetary forms of consideration, hoping to sidestep antitrust scrutiny. The most common and valuable of these was the “no-authorized-generic” (no-AG) agreement. This issue was squarely addressed by the Third Circuit Court of Appeals in its 2015 decision in King Drug Co. of Florence, Inc. v. SmithKline Beecham Corp..36

The case involved a settlement over GSK’s drug Lamictal®. As part of the deal, GSK promised the first-filer, Teva, that it would not launch its own “authorized generic” during Teva’s 180-day exclusivity period. An authorized generic is a generic version of the drug produced by the brand company itself, which can be launched to compete with the first-filer generic. The presence of an AG can be devastating to a first-filer’s profits, with one FTC report finding that it can reduce the FTF’s revenues during the exclusivity period by an average of 50%.

The Third Circuit held that a no-AG agreement is indeed a form of payment that is subject to antitrust scrutiny under the Actavis framework. The court’s reasoning was purely economic. It recognized that a promise not to launch an AG is an enormous “transfer of considerable value” from the brand to the generic. By agreeing not to compete, the brand effectively hands over a significant portion of the market and protects the generic’s high-margin duopoly profits. The court concluded that this valuable concession could serve the same anticompetitive purpose as a direct cash payment: inducing the generic to abandon its patent challenge and delay its entry.

Strategic Lesson 4: “Payment” is defined broadly. Any settlement term that transfers significant, otherwise-unexplained value to the generic challenger will be viewed with suspicion.

The King Drug decision was crucial because it closed a major loophole companies were attempting to exploit post-Actavis. It sent a clear signal that courts would look at the economic substance of a settlement, not just its form. The key takeaway is that the form of consideration—whether it’s cash, a no-AG promise, a favorable supply agreement, or a valuable side deal—is irrelevant. What matters is the economic reality: does the settlement involve a significant transfer of value from the brand to the generic that is not otherwise justified and that serves to delay competition?

This precedent has profound implications for generic strategists. Every single term in a settlement negotiation must now be viewed through an antitrust lens. The value of each concession must be assessed. Can it be justified on legitimate, pro-competitive grounds? Or could a court construe it as a disguised payment for delay? This requires a much more sophisticated and integrated approach to settlement, involving not just legal counsel but also economic experts who can analyze and defend the value of each component of the deal. The era of creative, non-monetary reverse payments as a safe harbor from antitrust law was officially over.

6. The Skinny Label Tightrope: Induced Infringement from Caraco to GSK v. Teva

As brand-name drugs have become protected by increasingly dense “patent thickets”—not just a single patent on the active ingredient, but dozens of later-filed patents on specific methods of use, formulations, or dosage strengths—the “skinny label” has emerged as one of the most critical tools for generic manufacturers. This strategy allows a generic to enter the market for unpatented uses of a drug while “carving out” the indications that are still protected by patents. However, a series of landmark cases has defined and, more recently, complicated this pathway, creating a high-wire act for generics balancing market opportunity against the significant risk of induced infringement liability.

6.1 Securing the Pathway: Caraco v. Novo Nordisk and Use Code Correction

The viability of the skinny label strategy hinges on the accuracy of the information in the FDA’s Orange Book. Specifically, it relies on the “use codes” that brand companies submit to describe the scope of their method-of-use patents. A brand has a clear incentive to describe its patent’s coverage as broadly as possible to deter generic entry. This very issue was at the heart of the 2012 Supreme Court case, Caraco Pharmaceutical Laboratories, Ltd. v. Novo Nordisk A/S.40

Novo Nordisk marketed the diabetes drug Prandin (repaglinide), which was approved by the FDA for three distinct uses. However, Novo’s patent only covered one of those uses: the combination therapy of repaglinide with metformin. Despite this, Novo submitted a use code to the FDA that was overly broad, implying that its patent covered all three approved uses of the drug. This inaccurate use code effectively blocked Caraco from using a “section viii statement” (the formal name for a skinny label submission) to market its generic for the two unpatented indications.41

Caraco challenged this in court, arguing that it should be able to force Novo to correct the misleading use code. The Supreme Court unanimously agreed. The Court held that the counterclaim provision in the Hatch-Waxman Act, 21 U.S.C. § 355(j)(5)(C)(ii)(I), explicitly allows a generic manufacturer to seek an order compelling a brand company to “correct” inaccurate “patent information” submitted to the FDA. The Court found that an overbroad use code was precisely the type of inaccurate information the statute was designed to address.

Strategic Lesson 5: The skinny label pathway is a powerful tool, and generics have a legal mechanism to defend it against brand overreach in the Orange Book.

The Caraco decision was a vital victory for the generic industry. It affirmed and secured the skinny label pathway as a potent strategic option for navigating the ever-growing complexity of pharmaceutical patent portfolios.40 Without a mechanism to challenge and correct inaccurate use codes, the skinny label provision would be toothless, allowing brands to effectively block generic entry for unpatented uses through simple administrative gamesmanship.

This ruling provided generics with the legal firepower needed to ensure the Orange Book remains an accurate reflection of a patent’s true scope. It solidified skinny labeling as a key strategy for launching generics of drugs with multiple indications that have been approved over time—a common lifecycle management tactic for brand companies. The importance of this pathway is underscored by research showing that from 2015 to 2019, approximately half of all new generic drugs for products with multiple indications entered the market using a skinny label, often avoiding years of remaining patent protection. Caraco ensures that this critical path to competition remains open.

6.2 The Game Changer: GSK v. Teva and the New Era of Induced Infringement Risk

For years after Caraco, the conventional wisdom was that as long as a generic manufacturer properly carved out a patented indication from its official FDA-approved label, it was safe from claims of induced infringement. The 2021 Federal Circuit decision in GlaxoSmithKline LLC v. Teva Pharmaceuticals USA, Inc. shattered that assumption and fundamentally altered the risk calculus for every generic company considering a skinny label launch.47

The case involved Teva’s generic version of GSK’s cardiovascular drug, Coreg® (carvedilol). GSK held a method-of-use patent for treating congestive heart failure (CHF). Teva launched its generic with a skinny label that carved out the CHF indication. Nevertheless, GSK sued Teva for induced infringement, arguing that Teva had encouraged doctors to prescribe the generic for the patented CHF use.

GSK’s case was not built on Teva’s label alone. Instead, it presented evidence of Teva’s marketing activities and public statements. This included press releases announcing the approval of its generic and promotional materials that described Teva’s product as an “AB-rated equivalent” to Coreg. GSK argued that by marketing its product as a full substitute for Coreg, Teva was implicitly encouraging doctors to use it for all of Coreg’s indications, including the patented one for CHF.

A jury agreed with GSK and awarded a staggering $235 million in damages. After a series of appeals, the Federal Circuit ultimately reinstated the verdict.40 The court’s majority ruled that a finding of induced infringement can be based on the “totality of the circumstances.” Even with a skinny label, a generic company could be found liable if its marketing, advertising, and other communications, taken as a whole, demonstrated an intent to encourage the infringing use. The Supreme Court later declined to hear Teva’s appeal, leaving the Federal Circuit’s controversial decision as the prevailing law.

Strategic Lesson 6: A skinny label alone is not a shield. Induced infringement risk now extends to all marketing, promotional materials, and public statements.

The GSK v. Teva decision represents one of the most significant shifts in Hatch-Waxman litigation in the last decade. It transforms the skinny label strategy from a discrete regulatory filing into a comprehensive, enterprise-wide compliance challenge. The pre-GSK paradigm was relatively simple: get the label right, and you are protected. The post-GSK reality is far more perilous. The decision blurs the lines between a company’s legal, regulatory, and commercial functions. The regulatory team can execute a perfect skinny label carve-out, only to have the commercial team’s standard marketing slogan—”AB-rated equivalent”—become the basis for hundreds of millions of dollars in liability.

The implications are profound and far-reaching. Legal and regulatory review must now extend to every press release, sales aid, product catalog, and investor communication to ensure that no language could be construed as encouraging or promoting a patented use. This dramatically increases the cost and complexity of compliance for skinny label products.

This heightened risk may have a significant chilling effect on the use of the skinny label pathway, particularly for smaller generic companies that cannot absorb the potential liability or the costs of such extensive litigation. Faced with the prospect of a massive damages award based on ambiguous marketing language, some companies may choose to forgo challenging certain drugs altogether, waiting for all method-of-use patents to expire. Evidence of this chilling effect may already be emerging; one recent study found that the rate of skinny label generic approvals dropped precipitously from 56% of susceptible drugs in 2021 (the year of the final Federal Circuit ruling) to just 20% in 2023. This trend, if it continues, could lead to significant delays in generic competition for some of the most widely used and profitable drugs, ultimately costing patients and the healthcare system billions.

7. Attacking the Patent’s Foundation: Precedents in Invalidity and Infringement

Beyond the high-profile battles over settlements and skinny labels, the daily trench warfare of Paragraph IV litigation is fought over the fundamental tenets of patent law: validity and infringement. Landmark decisions in these areas have provided generic manufacturers with powerful weapons and critical strategic lessons. These cases demonstrate that victory can often be found not by challenging the science of a drug, but by meticulously dissecting the legal and procedural history of the patent itself.

7.1 Obviousness-Type Double Patenting: Pfizer v. Teva (Celebrex)

One of the most potent, albeit highly technical, arguments for patent invalidity is “obviousness-type double patenting” (ODP). This judicially created doctrine is designed to prevent a patent owner from getting an improper time-wise extension of their monopoly by obtaining a second patent on an invention that is merely an obvious variation of an invention claimed in a first patent.51 The 2008 Federal Circuit decision in

Pfizer, Inc. v. Teva Pharmaceuticals USA, Inc., concerning the blockbuster pain medication Celebrex®, serves as a masterclass in how to successfully deploy this strategy.56

In the litigation, Teva argued that one of Pfizer’s key patents for Celebrex (the ‘068 patent) was invalid for ODP over an earlier Pfizer patent (the ‘165 patent). Pfizer countered that it was protected by the “safe harbor” provision of 35 U.S.C. § 121. This safe harbor is designed to protect patent applicants from ODP rejections when the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) forces them to split a single application into multiple “divisional” applications due to a “restriction requirement”.

However, Teva’s deep dive into the prosecution history revealed a critical procedural misstep by Pfizer. The later ‘068 patent did not originate from a divisional application; it came from a “continuation-in-part” (CIP) application. A CIP, by definition, contains new subject matter not present in the parent application. The Federal Circuit seized on this distinction. In a unanimous opinion, the court drew a bright line, holding that the § 121 safe harbor applies only to divisional applications, not to CIPs. Because Pfizer had added new matter and filed its application as a CIP, it had forfeited the safe harbor protection. Without that protection, the court found the ‘068 patent to be an obvious variant of the earlier ‘165 patent and thus invalid for ODP.58 The ruling was a major victory for Teva, invalidating a key patent and advancing the potential generic entry date by approximately one year.

Strategic Lesson 7: Meticulous analysis of a patent’s prosecution history can uncover fatal flaws, like ODP, that are unrelated to the scientific merits of the invention.

The Celebrex case is a powerful reminder that the procedural path a patent takes through the USPTO can be as important as the invention it claims. It demonstrates that a brand’s strategic decisions during patent prosecution—years before any litigation is contemplated—can create significant vulnerabilities for a generic challenger to exploit. A brand’s choice to add new data to an application and file it as a CIP, rather than sticking to the original disclosure in a divisional, can have devastating consequences down the line by stripping the resulting patent of crucial legal protections.

The lesson for generic manufacturers is to make a forensic examination of a target patent’s family tree and prosecution history a standard part of due diligence. Is a key patent that blocks market entry a continuation-in-part? Does it claim an invention that is an obvious modification of claims in an earlier-expiring parent patent? If so, it may be highly vulnerable to an ODP challenge, providing a direct path to invalidity that sidesteps complex scientific debates about the drug itself. This makes a deep understanding of patent prosecution procedure not just a task for patent attorneys, but a critical source of competitive intelligence for business strategists.

7.2 Defining Infringement in an Artificial World: Sunovion v. Teva

The act of infringement in a Hatch-Waxman case is “artificial”—it is the submission of the ANDA, not the actual sale of a product. This unique feature raises a fundamental question: what, exactly, is the product being accused of infringement? Is it the product described in the ANDA, or is it the product the generic company claims it will actually manufacture and sell? The Federal Circuit provided a clear and decisive answer to this question in its 2013 ruling in Sunovion Pharmaceuticals, Inc. v. Teva Pharmaceuticals USA, Inc..61

The case involved a generic version of the sleep aid Lunesta®. Sunovion’s patent claimed a form of the drug that was “essentially free” of a certain isomer, which the court construed to mean containing less than 0.25% of that isomer. The generic applicant, Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories, had submitted an ANDA with a product specification that allowed for up to 0.6% of the isomer, clearly overlapping with Sunovion’s patent claims.61 To circumvent this problem during litigation, Reddy’s submitted a declaration to the district court—but critically, not to the FDA as an amendment to its ANDA—vowing that it would only market a product that contained more than 0.3% of the isomer, thus keeping it outside the patent’s scope. The district court accepted this pledge and granted summary judgment of non-infringement.

The Federal Circuit emphatically reversed this decision. The court held that the infringement analysis in a Paragraph IV case is dictated by the product for which the ANDA seeks FDA approval, not by a hypothetical product described in a courtroom promise. The operative question is, “What is the scope of the approval the generic is asking the FDA to grant?”.61 Since Reddy’s ANDA specification described a product that could meet the patent’s claim limitations, the court found infringement as a matter of law. It dismissed Reddy’s courtroom declaration as an “unconventional and unenforceable ‘guarantee'” that could not override the plain language of its regulatory filing.61

Strategic Lesson 8: The ANDA specification is the battlefield. A generic cannot “talk its way out of infringement” in court if its FDA filing describes an infringing product.

The Sunovion decision provides essential clarity on the boundaries of the “artificial” infringement standard. It establishes that the ANDA is the definitive and controlling document in the infringement analysis. A generic company’s internal manufacturing controls, quality specifications, or even sworn declarations to a court are legally irrelevant if its official filing with the FDA seeks permission to market a product that, as described, would infringe.

The strategic takeaway for generic manufacturers is unequivocal: non-infringement must be designed into the product and meticulously documented in the ANDA from the very beginning. The time to engineer a way around a patent is during formulation and product development, not during litigation. Any ambiguity or overbreadth in the ANDA specification will be construed against the generic filer. This precedent underscores the importance of a close, collaborative relationship between a company’s R&D, regulatory affairs, and legal teams. The ANDA is not just a regulatory document; it is the central piece of evidence in the inevitable patent lawsuit, and it must be drafted with the rigors of litigation firmly in mind.

Table 1: Landmark Paragraph IV Decisions at a Glance

The legal precedents established over the last two decades have created a complex but navigable terrain for generic manufacturers. Each landmark case has contributed a vital piece to the strategic puzzle, offering clear lessons on everything from blockbuster challenges and settlement negotiations to skinny labeling and patent validity. The following table synthesizes these pivotal decisions, linking each legal holding to its direct, actionable lesson for business and legal strategists in the generic pharmaceutical industry. This serves as a quick-reference guide to the foundational case law that shapes the modern competitive landscape.

| Case Name | Key Drug/Topic | Central Legal Issue | Court’s Holding | Strategic Lesson for Generic Manufacturers |

| Barr v. Lilly (2000) | Prozac (fluoxetine) | First major P-IV challenge | Confirmed the viability and immense financial reward of challenging blockbuster patents. | Validated the high-risk, high-reward P-IV business model, proving no drug is too big to challenge. |

| FTC v. Actavis (2013) | AndroGel (testosterone) | Pay-for-Delay Settlements | “Reverse payment” settlements are not immune from antitrust law and must be judged by the “rule of reason.” | Scrutinize all settlement terms for potential antitrust risk. Justify any value transfer on pro-competitive grounds, not just market delay. |

| King Drug v. SmithKline (2015) | Lamictal (lamotrigine) | Non-Cash Reverse Payments | A “no-authorized-generic” agreement constitutes a form of payment subject to Actavis scrutiny. | “Payment” is defined by economic substance, not form. Any valuable concession can trigger antitrust review. |

| Caraco v. Novo Nordisk (2012) | Prandin (repaglinide) | Skinny Labeling | Generics can use a statutory counterclaim to force brands to correct inaccurate Orange Book “use codes.” | Defend the viability of the skinny label pathway by actively challenging overly broad or inaccurate use codes. |

| GSK v. Teva (2021) | Coreg (carvedilol) | Induced Infringement | A skinny label is not an absolute shield; the “totality of circumstances,” including marketing, can prove intent to induce infringement. | Induced infringement risk extends beyond the label. All commercial communications must be audited by legal to avoid implying patented uses. |

| Pfizer v. Teva (2008) | Celebrex (celecoxib) | Obviousness-Type Double Patenting | The § 121 “safe harbor” against ODP does not apply to continuation-in-part (CIP) applications. | Scrutinize patent prosecution histories. A brand’s procedural choices (e.g., filing a CIP vs. a divisional) can create fatal invalidity vulnerabilities. |

| Sunovion v. Teva (2013) | Lunesta (eszopiclone) | Defining Infringement | The infringement analysis is based on what the ANDA seeks to market, not what the generic promises a court it will market. | The ANDA is the definitive document. Non-infringement must be built into the product and reflected in the ANDA specification from the start. |

Part III: The Modern Battlefield: Evolving Strategies and Future Trends

The foundational precedents of the past two decades have set the stage, but the Paragraph IV battlefield is anything but static. The strategies employed by both brand and generic manufacturers are constantly evolving in response to new legislation, shifting judicial philosophies, and emerging technologies. Success in this modern era requires an understanding of these new fronts, from leveraging parallel administrative challenges at the Patent Office to countering the increasingly sophisticated defensive fortresses built by brand companies.

8. Beyond the District Court: The Impact of Inter Partes Review (IPR)

The passage of the America Invents Act (AIA) in 2011 introduced a new and powerful weapon into the arsenal of patent challengers: the Inter Partes Review (IPR). An IPR is a trial proceeding conducted before the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB), an administrative body within the USPTO, to reconsider the validity of an issued patent.63 For generic manufacturers, the advent of IPRs has created the opportunity to wage a “two-front war” against a brand’s patents, fighting simultaneously in federal district court and at the PTAB.

The strategic appeal of the IPR process lies in its significant procedural advantages for the challenger compared to district court litigation. First, the burden of proof is lower. To invalidate a patent in district court, a challenger must prove invalidity by “clear and convincing evidence.” At the PTAB, the standard is the less stringent “preponderance of the evidence”.65 Second, the PTAB applies a broader standard for claim construction (historically, the “broadest reasonable interpretation”), which can make patent claims more susceptible to being invalidated by prior art.65

These challenger-friendly standards have led to high rates of patent invalidation in IPR proceedings. Early on, it was not uncommon for the PTAB to invalidate challenged claims in 70% or more of the cases it heard, earning it the moniker of a patent “death squad” among some patent holders. While these rates have moderated somewhat, the PTAB remains a very favorable forum for invalidity challenges.

This has fundamentally altered the strategic calculus of Hatch-Waxman litigation. A generic company can now file an IPR petition against a key Orange Book-listed patent in parallel with its district court case. The threat of a faster, cheaper, and more likely successful invalidity ruling at the PTAB places immense pressure on the brand-name manufacturer. This added leverage can be a powerful tool in forcing a more favorable and earlier settlement. In some cases, a district court may even agree to stay its own proceedings pending the outcome of the IPR, though this is less common in the Hatch-Waxman context due to the ticking clock of the 30-month stay.63

However, the IPR pathway is not without its own risks and complexities. The PTAB has the discretion to deny institution of an IPR petition. Under a set of guiding principles known as the Fintiv factors, the Board may decline to hear a case if the parallel district court litigation is at an advanced stage, finding that it would be an inefficient use of resources. This creates a race against time for generic filers. Furthermore, the strategy carries a significant downside risk due to the doctrine of “estoppel.” If an IPR is instituted and the generic company loses—that is, the PTAB upholds the validity of the patent claims—the generic is then legally barred (estopped) from raising any invalidity arguments in the district court that it “raised or reasonably could have raised” during the IPR. This means a failed IPR can effectively eliminate a generic’s primary defense in the parallel litigation.

Thus, the decision to file an IPR is a high-stakes strategic choice. It is not a silver bullet but a powerful tactical weapon to be deployed with care. It offers the potential for a swift and decisive victory but carries the risk of permanently forfeiting key invalidity arguments. The most sophisticated generic strategies now involve a careful weighing of these factors, considering the specific patents at issue, the assigned judge and timeline in the district court case, and the company’s overall risk tolerance before deciding whether to open a second front at the PTAB.

9. Countering the Fortress: Responding to Patent Thickets and Other Brand Defenses

As generic manufacturers have become more adept at challenging individual patents, brand-name companies have responded by building ever-more-complex defensive fortifications around their products. The single-patent defense has been largely replaced by the “patent thicket,” a strategy designed not necessarily to win on the merits of any single patent, but to win through attrition by making litigation prohibitively expensive and time-consuming for any would-be challenger.24

A patent thicket is a dense web of numerous, often overlapping, patents covering a single drug. While the primary patent on a drug’s active ingredient provides the initial period of exclusivity, the thicket is composed of dozens or even hundreds of secondary patents. These patents, often filed years after the drug’s initial FDA approval, do not claim new therapeutic compounds but rather incremental modifications: new formulations, specific dosage strengths, methods of manufacturing, or new methods of using the drug for different indications.69 For the top-selling drugs in the U.S., a staggering 66% of all patent applications are filed

after the drug has already been approved by the FDA.

The canonical example of this strategy is AbbVie’s blockbuster drug, Humira. AbbVie amassed a portfolio of over 250 patent applications for Humira, which allowed it to delay biosimilar competition in the U.S. until 2023, more than two decades after the drug was first launched. Each of these patents represents another legal hurdle a challenger must overcome. Litigating against such a portfolio is a monumental undertaking, requiring millions of dollars in legal fees and years of court battles to “clear the way” for a generic launch.69

Beyond patent thickets, brands employ other defensive tactics. “Product hopping” involves making a minor, often trivial, change to a drug (e.g., switching from a tablet to a capsule or changing the dosage) and then heavily promoting the new, patent-protected version to switch patients before the patent on the original version expires. Another common tactic is the launch of an “authorized generic” (AG). As discussed previously, an AG is a generic version of the drug marketed by the brand company itself, which can be launched to compete directly with the first-to-file generic, thereby diluting the value of the 180-day exclusivity period and reducing the incentive for generics to challenge patents in the first place.68

Strategic Lesson 9: Product selection and litigation budgeting must account for the reality of patent thickets. A successful challenge requires a multi-faceted strategy that combines litigation, IPRs, and skinny labeling.

The rise of these sophisticated defensive strategies means that a Paragraph IV challenge is rarely a straightforward, one-on-one duel over a single patent. It is a war of attrition against an entire portfolio. This reality must be integrated into the very first stage of a generic company’s strategy: product selection.

The due diligence process for a potential generic target can no longer focus solely on the strength of the core composition-of-matter patent. It must involve a comprehensive mapping of the entire patent thicket. How many secondary patents are there? What do they cover? How strong are they? This analysis is crucial for accurately forecasting the cost, timeline, and probability of success for a potential challenge. A drug with a single, strong patent nearing expiration may be a more attractive target than a drug with a weaker core patent but a thicket of 50 secondary patents.

Successfully navigating a patent thicket requires a multi-pronged offensive strategy. The generic challenger must dissect the portfolio and attack each patent with the most appropriate tool. The weakest patents—often those covering formulations or methods of use—may be ideal candidates for an IPR at the PTAB, where the odds of invalidation are higher. Patented methods of use for specific indications can be addressed through a skinny label strategy, carving them out to allow for an earlier launch for unpatented uses. The remaining, stronger patents can then be litigated in district court. This integrated approach allows a generic to efficiently manage its resources and attack the brand’s fortress from multiple angles simultaneously. The financial model for any Paragraph IV challenge must now reflect this more complex and costly reality.

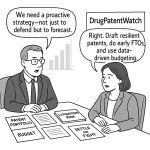

10. The Data-Driven Approach: Leveraging Competitive Intelligence for Strategic Advantage

In the complex, high-stakes environment of modern Paragraph IV litigation, intuition and experience are no longer enough. The sheer volume of variables—patent expiration dates, regulatory exclusivities, litigation histories, settlement trends, the presence of patent thickets, and the potential for IPRs—demands a rigorous, data-driven approach to strategic decision-making. In the contemporary generic market, competitive advantage is increasingly achieved through the superior collection, analysis, and application of competitive intelligence.26

The decision to initiate a Paragraph IV challenge is, at its core, a multi-million-dollar investment decision. The average cost of litigating a patent case can be around $5 million, and the stakes are enormous. A successful challenge can lead to hundreds of millions in revenue, while a loss can result in a total write-off of the investment, plus the potential for damages if a launch was made “at risk.” Making this decision requires a sophisticated risk-reward analysis based on a multitude of data points.

Data analysis is critical for the very first step: identifying the right generic targets. As one study has shown, the market value of the brand drug is the single most important predictor of whether a patent challenge will occur. Drugs in the top decile of market value are challenged 90% of the time, whereas those in the bottom deciles are challenged only about 24% of the time. This data allows a company to make strategic choices: should it compete in the crowded, high-value space against numerous other challengers, or should it focus on smaller, underserved niche markets where it may be the sole challenger and face less competition?

This is where specialized competitive intelligence platforms like DrugPatentWatch become indispensable. These platforms are designed to aggregate and synthesize the vast and disparate streams of data relevant to pharmaceutical patent litigation. They consolidate information from the FDA’s Orange Book, USPTO patent databases, federal court dockets, clinical trial registries, and corporate financial reports into a single, searchable, and analyzable database.74

Using such a tool, a generic strategist can efficiently:

- Monitor the patent landscape: Track new patent listings, expirations, and extensions for key drugs.

- Anticipate litigation: Identify which drugs are likely to be challenged based on their market size and patent profile.

- Track competitor activity: See which other generic companies have filed Paragraph IV certifications for a given drug, which is critical for assessing the value of being a first-filer versus a subsequent filer.

- Inform portfolio management: Make data-driven decisions about which products to add to the development pipeline, balancing the potential rewards against the likely costs and risks of litigation.26

Strategic Lesson 10: In the modern era, competitive advantage in the generic space is achieved through superior data and analytics, not just legal acumen or manufacturing efficiency.

Winning in the generic market today is less about being a fast follower and more about being a smart predictor. The companies that will thrive are those that can most accurately forecast litigation outcomes, model the financial impact of various launch scenarios, and identify the most vulnerable patents within a brand’s portfolio. Manually gathering and analyzing the data required to do this is an inefficient and error-prone process.

Platforms like DrugPatentWatch provide the essential infrastructure for this modern, data-centric approach. They provide the raw data and the analytical tools necessary to conduct thorough due diligence and build sophisticated predictive models. This enables a company to move beyond opportunistic, one-off challenges and toward the creation of a deliberately architected portfolio designed for sustainable, profitable growth. In a world defined by the complex legal precedents and evolving strategies discussed throughout this report, a data-driven approach is no longer a luxury; it is the fundamental key to survival and success.

Part IV: Conclusion and Future Outlook

11. Synthesizing the Lessons: A Modern Playbook for P-IV Success

The journey through the landmark decisions of Hatch-Waxman litigation reveals a clear and compelling narrative: the landscape for generic manufacturers has evolved from a straightforward regulatory pathway into a multi-dimensional strategic chess match. The simple act of filing a Paragraph IV certification now initiates a complex cascade of legal, regulatory, and commercial considerations that demand a sophisticated, integrated approach. The lessons learned from the seminal cases of the past two decades form the basis of a modern playbook for success. Victory is no longer the domain of the fastest or the cheapest, but of the most strategically astute.

This modern playbook can be synthesized into five core pillars:

- Strategic Target Selection: The battle is often won before it is fought. The decision of which drug to challenge is the most critical strategic choice a generic company makes. As the data shows, not all targets are created equal. A data-driven approach, leveraging competitive intelligence tools to analyze market size, the density of the patent thicket, and the litigation history of the brand, is essential. The goal is to pick battles that are not just winnable, but worth winning.

- Meticulous Due Diligence: The devil is in the details of the patent’s history. As the Pfizer v. Teva (Celebrex) case demonstrated, a fatal flaw can be found in the procedural choices a brand made during patent prosecution years earlier. A forensic analysis of the entire patent family, its prosecution history, and its relationship to other patents is non-negotiable. This deep dive uncovers vulnerabilities like obviousness-type double patenting and provides the ammunition for a successful invalidity challenge.

- Integrated Legal-Commercial Strategy: The era of siloed departments is over. The lesson from GSK v. Teva is stark: a perfect skinny label can be undone by a single careless press release. Legal and regulatory teams must be deeply embedded with commercial, marketing, and communications teams to ensure that all public-facing materials are rigorously vetted for induced infringement risk. The message must be consistent and disciplined across the entire organization, from the ANDA filing to the sales representative’s pitch.

- Antitrust-Aware Negotiations: The shadow of FTC v. Actavis looms over every settlement discussion. The “easy money” of a simple pay-for-delay settlement is gone. Every term of a settlement agreement, especially any transfer of value from the brand to the generic, must be justifiable on pro-competitive grounds. This requires a nuanced understanding of antitrust law and the ability to structure creative deals—focused on early entry dates and other legitimate considerations—that can withstand FTC scrutiny.

- Multi-Forum Litigation Tactics: The modern battlefield is not confined to the district court. The advent of Inter Partes Review at the PTAB has provided a powerful, parallel venue for challenging patent validity. An intelligent litigation strategy now involves a coordinated, multi-forum approach, using the threat of a faster, more successful IPR to apply pressure and gain leverage in the district court litigation and in settlement negotiations.

Mastering these five pillars is the price of admission to the top tier of the generic pharmaceutical industry. The companies that successfully integrate these principles into their corporate DNA will be the ones who can consistently navigate the complexities of the Hatch-Waxman landscape to deliver value to patients, payers, and shareholders alike.

12. The Road Ahead: Emerging Trends and the Future of Generic Competition

The strategic landscape of generic competition is in a perpetual state of flux, shaped by continuous legislative tinkering, new judicial interpretations, and technological advancement. Looking ahead, several key trends are poised to redefine the rules of engagement and present both new challenges and new opportunities for generic manufacturers.

First, the legislative and regulatory scrutiny of brand-name tactics to delay competition is intensifying. The public and political outcry over high drug prices has put practices like patent thicketing and pay-for-delay settlements squarely in the crosshairs of policymakers. We can anticipate continued efforts in Congress to pass legislation aimed at curbing these strategies. Proposed bills, such as the BLOCKING Act, seek to reform the 180-day exclusivity rules to prevent “parking,” while other proposals aim to limit the number of patents a brand can assert in litigation or increase the burden of proof for obtaining secondary patents.69 Generic manufacturers must remain actively engaged in this policy debate, as the outcomes could significantly alter the strategic value of various litigation tactics.

Second, the lessons learned from the two-decade-long battle over small-molecule drugs are now being applied and adapted to the next great frontier of generic competition: biosimilars. The Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA) created a new, and in many ways more complex, pathway for the approval of generic versions of large-molecule biologic drugs.78 Landmark cases like

Amgen v. Sandoz have begun to clarify the procedural intricacies of the BPCIA’s “patent dance.” As more blockbuster biologics lose exclusivity, the litigation in this space will accelerate, and the strategic precedents set in Hatch-Waxman litigation will serve as the crucial starting point for this new legal arena.

Finally, the role of technology and data analytics in shaping strategy will only continue to grow. The use of artificial intelligence and machine learning to analyze vast datasets of patent filings, litigation outcomes, and judicial behavior is moving from the experimental to the essential. The ability to predict with greater accuracy the likelihood of a patent being invalidated, the probable outcome of a case before a specific judge, or the optimal timing for a settlement will become a key differentiator. Companies that invest in these advanced analytical capabilities will be able to make smarter, faster, and more profitable decisions.

The fundamental tension at the heart of the Hatch-Waxman Act—the need to balance the encouragement of innovation with the demand for affordable access—is eternal. The legal and strategic battles that flow from this tension will continue to evolve, becoming ever more complex and sophisticated. The generic manufacturers who will thrive in the decades to come will be those who are not just efficient manufacturers, but agile, informed, and data-savvy strategists who have mastered the lessons of the past to win the battles of the future.

Key Takeaways

- The Hatch-Waxman Act Transformed the Industry: The Act created the modern generic industry by establishing the ANDA pathway and the Paragraph IV challenge, turning patent litigation into a proactive, pre-launch business strategy rather than a reactive defense.

- The Prozac Case Was the Watershed Moment: Barr Laboratories’ successful challenge to Prozac provided the proof-of-concept that challenging even the biggest blockbuster drugs was a viable and immensely profitable strategy, catalyzing the growth of Paragraph IV litigation.

- Settlements Are Under Intense Antitrust Scrutiny: The Supreme Court’s decision in FTC v. Actavis fundamentally changed settlement negotiations. “Pay-for-delay” deals are now judged under a “rule of reason,” and any transfer of value from a brand to a generic—including non-monetary concessions like “no-AG” agreements—is a potential antitrust violation.

- Skinny Labeling is a Powerful but Risky Strategy: While Caraco v. Novo Nordisk secured the right for generics to challenge inaccurate “use codes,” the GSK v. Teva decision created significant new risk. A skinny label is no longer a complete shield against induced infringement claims, which can now be based on the “totality” of a company’s marketing and communications.

- Patent Validity is a Key Battleground: Technical arguments like Obviousness-Type Double Patenting, as seen in the Pfizer v. Teva (Celebrex) case, can be powerful tools for invalidating patents. A deep analysis of a patent’s prosecution history is critical.

- The ANDA is the Definitive Document for Infringement: As established in Sunovion v. Teva, the infringement analysis in a Paragraph IV case is based on the product described in the ANDA filing, not on subsequent promises made in court. Non-infringement must be designed into the product and reflected in the regulatory submission.

- Modern Litigation is a Multi-Front War: The advent of Inter Partes Review (IPR) at the PTAB allows generics to challenge patent validity in a more favorable, parallel forum, creating significant leverage in district court litigation and settlement talks.

- Data-Driven Strategy is Non-Negotiable: The complexity of patent thickets and the high stakes of litigation demand a sophisticated, data-driven approach. Leveraging competitive intelligence platforms like DrugPatentWatch to inform product selection, risk assessment, and litigation strategy is essential for success.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. After GSK v. Teva, is the skinny label strategy still viable for generic manufacturers?

Yes, the skinny label strategy remains a viable and essential tool, but it now carries significantly more risk and requires a much higher degree of diligence. The key takeaway from GSK v. Teva is that the label itself is no longer the sole determinant in an induced infringement analysis. Courts will now look at the “totality of the circumstances,” including press releases, marketing materials, product catalogs, and even internal communications. To mitigate this risk, generic companies must implement a rigorous, enterprise-wide compliance strategy. Legal and regulatory teams must proactively review and approve all commercial communications to ensure no language could be interpreted as encouraging or promoting a patented, off-label use. The focus should be on precise language that clearly limits any equivalence claims (e.g., “AB-rated for the approved indications on this label”) rather than broad statements that a product is a generic “equivalent” to the brand.

2. How has the Supreme Court’s Actavis decision changed the way generic and brand companies approach settlement negotiations?

The Actavis decision fundamentally shifted settlement negotiations from a patent-centric to a competition-centric framework. Before Actavis, the primary consideration was whether the settlement’s delay of generic entry fell within the “scope of the patent’s” remaining term. Now, the central question is whether there has been a “large and unjustified” transfer of value from the brand to the generic that serves to delay competition. This has made both sides far more cautious. Overt cash-for-delay payments are now rare. Instead, negotiations focus on the generic’s entry date and other pro-competitive terms. Any value transferred to the generic, including non-monetary concessions like a “no-authorized-generic” promise, must be carefully justified, for example, as representing avoided litigation costs or fair-market value for services rendered. This has made settlements more complex to structure and requires a thorough antitrust analysis of every term.

3. What is the strategic value of filing an Inter Partes Review (IPR) in parallel with a Paragraph IV litigation, and what are the main risks?

The primary strategic value of filing a parallel IPR is leverage. The PTAB offers a faster, less expensive forum with a lower burden of proof for invalidating a patent compared to district court. A successful IPR can either end the litigation outright or put immense pressure on the brand company to settle on favorable terms. However, the risks are substantial. First, the PTAB can exercise its discretion to deny institution of the IPR, particularly if the district court case is already well underway. Second, and more critically, is the risk of estoppel. If the PTAB institutes the IPR but ultimately upholds the patent’s validity, the generic company is legally barred from raising any invalidity arguments in the district court that it raised or could have reasonably raised in the IPR. This can be a fatal blow to the generic’s case, making the decision to file an IPR a high-stakes gamble that must be carefully weighed.

4. How should a generic company’s product selection strategy adapt to the prevalence of “patent thickets”?

The rise of patent thickets necessitates a shift from a purely patent-focused to a portfolio-focused due diligence process. A generic company can no longer assess a target based solely on the expiration date and strength of the primary compound patent. The strategy must now involve:

- Mapping the Thicket: A comprehensive analysis of all secondary patents—formulation, method-of-use, manufacturing, etc.—to understand the full scope of the legal challenge.

- Cost-Benefit Analysis of the Portfolio: Budgeting for litigation must account for the possibility of challenging multiple patents across multiple forums (district court and PTAB). The projected cost of clearing the entire thicket must be weighed against the potential market reward.