Introduction: From Legal Document to Revenue Blueprint

In the high-stakes world of pharmaceuticals, where the journey from a single molecule to a blockbuster drug is paved with billions of dollars in investment and fraught with risk, the humble patent document stands as the ultimate arbiter of value. With the global prescription drug market soaring past $1.5 trillion annually, the ability to accurately forecast a drug’s commercial potential is not just a competitive advantage; it is the essential lifeblood of strategic planning, R&D investment, and shareholder confidence. Yet, for many business professionals, the dense legalese and technical jargon of patent filings can seem like an impenetrable fortress. This report is designed to dismantle that fortress, brick by brick.

The Core Premise: Why Patents are the Bedrock of Pharmaceutical Value

At its heart, a pharmaceutical patent is far more than a simple legal right. It is the foundational asset, the very DNA of a drug’s commercial lifecycle.2 This government-granted monopoly, typically lasting 20 years from the application date, provides the crucial period of market exclusivity necessary for a company to recoup its staggering R&D expenditures and generate the profits that fuel future innovation.2 Without this protection, the economic model of the pharmaceutical industry would collapse.

For the strategist, the portfolio manager, or the investor, understanding how to decipher the information encoded within these documents is paramount. It is akin to possessing a map of the future—a blueprint revealing the contours of a drug’s projected revenue stream, the timing of its inevitable decline, and the competitive battlegrounds that will define its market share. The infamous “patent cliff,” a term that strikes fear into the hearts of executives, represents the moment this exclusivity ends. When a blockbuster drug loses patent protection, generic competition can flood the market, causing revenues to plummet by as much as 79% in a shockingly short period. Between now and 2030, analysts project that more than $200 billion in annual pharmaceutical revenue is at risk from these expiring patents, making the science of forecasting more critical than ever.5

Deeper Insights: The Strategic Weaponization of Intellectual Property

The role of the patent has undergone a profound evolution. The original intent of the patent system was to offer a “defensive shield”—a temporary, well-defined monopoly to protect and incentivize genuine innovation.4 In exchange for this protection, the inventor must publicly disclose the invention, adding to the collective knowledge of the field.5 This was the simple, elegant trade-off at the heart of the system.

However, the modern pharmaceutical landscape reveals a much more complex and aggressive reality. The patent system has been transformed from a defensive shield into an offensive strategic weapon, wielded with precision to control markets, obstruct competitors, and extend monopolies far beyond their originally intended lifespan. This is not to say that the defensive role has vanished, but it has been augmented by a sophisticated set of legal and commercial tactics that have fundamentally altered the nature of competition.

Consider the evidence: for many of the world’s top-selling drugs, the majority of patents are not filed before the drug is approved, but after. For its blockbuster drug Humira, AbbVie filed an astonishing 257 patent applications, with a full 90% of the 130 granted patents being issued after the drug was already on the market. These are not patents on the core invention—the Humira molecule itself was covered by a foundational “base” patent. Instead, they are secondary patents covering everything from manufacturing processes and formulations to specific methods of use and dosing regimens.

This strategy creates what is known as a “patent thicket”—a dense, overlapping, and interlocking web of intellectual property so formidable that it becomes economically and logistically prohibitive for a generic or biosimilar competitor to challenge.5 The goal is no longer just to protect the core innovation, but to create a legal minefield that delays, deters, and ultimately defeats would-be competitors. This strategic shift from protection to obstruction represents the “weaponization” of the patent system.

For the business professional, this transformation has profound implications. It means that estimating a drug’s sales potential can no longer be based on a simple check of a single patent’s expiration date. The actual period of market exclusivity—the true driver of revenue—is now a function of the strength, density, and defensibility of an entire, complex portfolio of patents. Patent analysis has evolved from a straightforward legal check into a sophisticated exercise in competitive wargaming and risk assessment. This report will provide the tools and frameworks necessary to navigate this new reality, turning patent data from a static legal fact into a dynamic source of competitive intelligence.

Section 1: The Anatomy of Exclusivity – A Primer for Strategists

To accurately forecast pharmaceutical sales, one must first master the language of monopoly. In the pharmaceutical universe, market exclusivity is not a monolithic concept. It is a dual-headed beast, born of two distinct but overlapping systems: patent protection and regulatory exclusivity. Confusing the two is a common and costly mistake. A drug’s core patent may expire, but its market could remain sealed off from competition for years due to a powerful regulatory exclusivity. Understanding this interplay is the first principle of sound forecasting.

Patents vs. Regulatory Exclusivity: Understanding Your Monopoly

The fundamental distinction lies in their origin and purpose. Patents are property rights granted by a national patent office, such as the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO). They protect the invention itself—be it a new molecule, a method of use, or a manufacturing process—from being made, used, or sold by others without permission.7 They are granted based on criteria of novelty, usefulness, and non-obviousness.

Regulatory exclusivity, in contrast, is granted by a regulatory body like the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) upon a drug’s approval. It is not a property right but an exclusive marketing right. Its purpose is to incentivize innovation in specific areas of public health need by guaranteeing a period of market protection, regardless of the patent status.4 This protection prevents the FDA from approving competing generic or biosimilar applications for a set period.

These two forms of protection can run concurrently, overlap, or exist independently. A drug can have patent protection without regulatory exclusivity, or vice versa. The effective period of monopoly is determined by whichever protection lasts longer. For a forecaster, the “Loss of Exclusivity” (LOE) date—the point at which the market opens to competition—is the single most critical variable in any valuation model. This date is not determined by the patent expiration alone but by the final expiration date of all relevant patents and exclusivities.

The U.S. market, being the largest and most complex, offers several key types of regulatory exclusivity that every strategist must know:

- New Chemical Entity (NCE) Exclusivity: Provides a 5-year period of market protection for drugs containing an active moiety that has never before been approved by the FDA. This is a powerful incentive for developing truly novel small-molecule drugs.4

- Orphan Drug Exclusivity (ODE): A cornerstone of rare disease drug development, ODE grants a 7-year period of market exclusivity for drugs that treat diseases affecting fewer than 200,000 people in the U.S..4

- Biologics Exclusivity (BPCIA): Under the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act, novel biologic drugs receive a robust 12 years of market exclusivity from the date of first licensure. This extended period reflects the complexity and cost of developing large-molecule therapies.4

- Pediatric Exclusivity: To encourage the study of drugs in children, the FDA can grant an additional 6 months of exclusivity, which is tacked onto any existing patents and other exclusivities. This can be incredibly valuable, potentially adding hundreds of millions of dollars in sales for a blockbuster drug.4

- 3-Year “Other” Exclusivity: This is granted for a “change” to a previously approved drug, such as a new indication, a new formulation, or a switch from prescription to over-the-counter status, provided that new clinical investigations were essential to the approval. This is a key tool in lifecycle management strategies.7

The following table provides a clear, at-a-glance comparison of these two critical forms of protection, essential for any strategic planning exercise.

| Attribute | Patent Protection | Regulatory Exclusivity |

| Basis for Grant | Novelty, utility, and non-obviousness of the invention itself. | Meeting specific statutory requirements upon drug approval (e.g., NCE, ODE status).4 |

| Granting Body | U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) or other national patent offices. | U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) or other national regulatory bodies. |

| Typical Duration | 20 years from the patent application filing date.4 | Varies: 5 years (NCE), 7 years (ODE), 12 years (Biologics), 3 years (New Clinical Studies).4 |

| Scope of Protection | Prevents others from making, using, or selling the patented invention. | Prevents the regulatory body from approving a generic or biosimilar application for the drug product. |

| Can be Extended? | Yes, through Patent Term Extension (PTE) to compensate for regulatory delays. | Yes, a 6-month pediatric extension can be added to existing exclusivities. |

The Patent Arsenal: Types of Pharmaceutical Patents

Just as a military commander has different weapons for different strategic objectives, a pharmaceutical company deploys a variety of patent types to construct its fortress of exclusivity. Understanding this arsenal is crucial to assessing the strength and durability of a drug’s market position. The patents can be thought of in a hierarchy, from the foundational “crown jewels” to the secondary layers that reinforce and extend the monopoly.

- Base / Composition of Matter Patents: These are the most powerful and sought-after patents in the industry. They cover the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) itself—the core molecule or protein sequence that provides the therapeutic effect.2 A strong, broad composition of matter patent is the gold standard of protection, as it prevents any competitor from selling the same active ingredient for any purpose, at least until the patent expires.

- Secondary Patents: While the base patent protects the core invention, secondary patents are filed later in a drug’s lifecycle to protect incremental improvements and expand the scope of the monopoly. These are the primary tools of “evergreening” and “patent thicket” strategies.

- Method-of-Use Patents: These patents do not cover the drug itself, but rather a specific, novel way of using it.2 For example, if a drug initially approved for rheumatoid arthritis is later found to be effective for psoriasis, the company can file a new method-of-use patent covering the treatment of psoriasis. These are critical for “pipeline-in-a-product” strategies, where a single drug’s market is expanded over time.

- Formulation & Delivery Patents: These protect unique formulations of a drug or novel delivery mechanisms. This could include an extended-release version that allows for once-daily dosing instead of twice-daily, a new combination of ingredients, or a proprietary auto-injector device that makes administration easier for patients.2 These patents can be highly effective at blocking generics, which may struggle to design a non-infringing alternative.

- Process Patents: Instead of protecting the product, a process patent protects a specific, innovative method of manufacturing that product. If a company develops a more efficient or higher-purity method for synthesizing its API, a process patent can prevent competitors from using that same advantageous method.

- Combination Patents: These patents are used for drugs that combine two or more active ingredients into a single therapy, such as a fixed-dose combination pill for treating HIV or hypertension. They protect the specific synergistic combination, even if the individual components are off-patent.

The Crucial Metric: Statutory Term vs. Effective Patent Life

One of the most fundamental economic realities of the pharmaceutical industry is the stark difference between the statutory patent term and the effective patent life. The law grants a patent term of 20 years from the date of filing.4 To an outsider, this might sound like a generous two-decade monopoly. The reality is far different.

A substantial portion of this 20-year term—often 10 to 15 years—is consumed by the arduous and time-consuming process of drug development. This includes extensive preclinical research, multiple phases of human clinical trials, and a rigorous regulatory review by the FDA or other agencies.4 Consequently, by the time a drug finally reaches the market and begins generating revenue, a significant chunk of its patent life has already evaporated.

The effective patent life is the actual period during which a drug enjoys market exclusivity, from its launch date until the first generic or biosimilar competitor enters the market. On average, this period is only about 7 to 12 years.4 This erosion of the effective monopoly period is not a minor detail; it is the central economic challenge that drives the entire industry’s strategic behavior. It is the primary justification for high launch prices and the powerful incentive behind the aggressive lifecycle management strategies, like evergreening and patent thicketing, that are designed to claw back some of this lost time.

Deeper Insights: The Interplay of Patent Type and Forecasting Accuracy

A sophisticated sales forecast moves beyond simply identifying the final LOE date. It seeks to model the shape of the revenue curve over the drug’s entire lifecycle. Here, a nuanced understanding of the patent portfolio’s composition becomes a powerful, yet often underutilized, predictive tool. The mix of patent types within a portfolio is not random; it is a reflection of the company’s strategic intent and can provide strong clues about the drug’s future revenue trajectory.

Consider the data: one study found that drugs with more than 50% of their patent portfolio consisting of method-of-use patents demonstrated 18% higher peak sales. At first glance, this might seem counterintuitive, as method-of-use patents are generally considered weaker than composition of matter patents. But what does this correlation truly signify?

A drug protected primarily by a single, strong composition of matter patent has a powerful but finite monopoly. Its revenue curve is likely to follow a traditional bell shape: a ramp-up post-launch, a period of peak sales, and then a sharp decline at the patent cliff. The market is well-defined from the start.

In contrast, a portfolio rich in method-of-use patents tells a different story. It suggests a “pipeline-in-a-product” strategy. The company launched the drug for an initial indication and is now systematically investing in R&D to prove its efficacy in new patient populations, filing new method-of-use patents with each successful trial. Each new approved indication opens up a new market segment, effectively expanding the drug’s total addressable market over time.

This strategy results in a fundamentally different revenue curve. Instead of a single peak, the curve might have multiple, successive “humps” as each new indication comes online, or it might have a longer, flatter plateau at its peak as the market continuously expands. An analyst who recognizes this pattern can move beyond a generic bell curve and model a more nuanced, multi-stage revenue forecast. By analyzing the structure of the patent portfolio, they can better predict the structure of the revenue stream, leading to a more accurate and defensible valuation. The patent portfolio is not just a legal shield; it is a strategic narrative that, if read correctly, can reveal the plot of the drug’s commercial future.

Section 2: The Forecaster’s Trinity – Core Methodologies for Patent-Based Valuation

Once the landscape of exclusivity is understood, the next step is to translate that knowledge into a tangible financial figure. How much is a patented drug, or its underlying intellectual property, actually worth? To answer this, analysts turn to a trinity of core valuation methodologies: the Income Approach, the Market Approach, and the Cost Approach. While each has its strengths and weaknesses, the Income Approach, with its focus on future cash generation, reigns supreme in the pharmaceutical industry. Mastering all three, however, provides a robust toolkit for creating and cross-validating comprehensive sales forecasts.

The Income Approach: Discounting Future Cash Flows to Present Value

The Income Approach is the dominant and most theoretically sound method for valuing pharmaceutical assets because it directly links a patent’s value to the economic benefit it is expected to generate. The core tool of this approach is the Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) model, a multi-step process that projects a drug’s future revenues and costs and then discounts them back to a single, present-day value.

Step 1: Projecting Revenue Streams

The foundation of any DCF model is the “top line”—the projection of annual sales over the drug’s entire commercial life. This is not mere guesswork; it is a systematic, bottom-up build based on epidemiological and market data.13 The key inputs include:

- Target Population: Estimating the total number of patients with the specific disease or condition the drug treats (prevalence for chronic conditions, incidence for acute events).13

- Market Penetration: Forecasting the percentage of the target population that will actually be treated with the drug. This is influenced by factors like diagnostic rates, treatment rates, physician acceptance, and the drug’s competitive profile (e.g., efficacy, safety, convenience).13

- Pricing: Estimating the net price per unit after accounting for rebates and discounts.

- Compliance and Persistence: Factoring in real-world patient behavior, such as how consistently they take the medication as prescribed.

A simple base case might look like this: a drug is projected to be used by 200,000 patients, with a net price of $1,500 per patient per year, resulting in a base annual sales forecast of $300 million. This projection is then extended year by year over the drug’s expected life.

Step 2: Incorporating the Patent Cliff

No pharmaceutical sales forecast is complete without modeling the dramatic impact of the patent cliff. The DCF model must explicitly account for the loss of exclusivity (LOE) date, after which generic or biosimilar competition enters the market. This event triggers a sharp and immediate decline in both price and sales volume for the branded product.

The data on this phenomenon is stark and consistent. Upon generic entry, prices for oral drugs can drop significantly, and for physician-administered drugs, the immediate price drop can be between 38% and 48%.1 The impact on revenue is even more severe. Within three years of facing generic competition, a branded drug’s revenue can decline by as much as 74%. The classic case study is Pfizer’s Lipitor, once the world’s best-selling drug. After its main U.S. patent expired in 2011, its annual revenue collapsed from approximately $13 billion to under $3 billion within just a few years, demonstrating the brutal reality of the patent cliff. The DCF model must reflect this sharp “step-down” in revenue in the years following the forecasted LOE date.

Step 3: Risk Adjustment and Discount Rates

A raw cash flow projection is an optimistic scenario. The reality of drug development is one of profound risk. A drug in Phase III clinical trials still faces a substantial probability of failure—often cited as around 40%—and the risk of unexpected regulatory delays can add years to the timeline, eroding the patent life. A credible DCF model must quantify these risks.

This is done in two primary ways. First, the cash flows themselves can be probability-adjusted. For example, the projected revenues for a drug in Phase III might be multiplied by a 60% probability of success. Second, and more commonly, the risk is captured in the discount rate.

The discount rate is a percentage used to calculate the present value of future cash flows. A higher discount rate reflects higher risk, resulting in a lower present value. In the pharmaceutical industry, discount rates for development-stage assets are typically high, often in the range of 8% to 12% or more, to account for the significant clinical and regulatory risks. The final output of the DCF model is the Net Present Value (NPV), which represents the value of all projected, risk-adjusted future cash flows in today’s dollars. For instance, a drug with a 12-year remaining patent life and a base case NPV of $2.1 billion might see its risk-adjusted NPV fall to $1.3 billion after factoring in the probabilities of clinical failure and regulatory delays.

The Market Approach: Valuation by Comparison

The Market Approach offers a different lens for valuation. Instead of building a forecast from the ground up, it determines a drug’s value by looking at what the market has paid for similar, or “comparable,” assets.1 This is a form of relative valuation, relying on real-world transactions to provide a benchmark.

The key sources for comparable data include:

- Precedent M&A Transactions: The acquisition price of a company with a similar lead asset.

- Licensing and Partnership Deals: The upfront payments, milestones, and royalty rates agreed upon in deals for comparable drugs.

- Public Company Comparables: The market capitalization of publicly traded companies with similar assets.

A prime example of the Market Approach in action was the valuation of Novartis’s CAR-T cell therapy, Kymriah. To estimate its value, analysts looked at two key competitors: Gilead’s Yescarta, which was acquired via a $12 billion deal for Kite Pharma, and Bristol Myers Squibb’s Breyanzi, which had a market valuation of around $9 billion. Analysts then made adjustments based on Kymriah’s differentiated clinical profile, such as its superior patient response rates, to arrive at a final valuation of approximately $14 billion.

The strength of the Market Approach lies in its connection to real-world market sentiment. However, its primary limitation is the difficulty of finding truly comparable assets. This is especially true for first-in-class therapies with novel mechanisms of action, where no direct precedent exists.

The Cost Approach: R&D as a Valuation Floor

The Cost Approach is the simplest and least frequently used of the three methodologies. It values a patent based on the cost that was incurred to create the underlying invention—essentially, the total R&D expenditure required to bring the drug to its current stage of development.1

Given that the average cost to develop a new drug was estimated to be $2.3 billion in 2023, this can provide a substantial baseline figure. A simple formula might take the total R&D cost, divide it by the remaining patent years, and apply an industry-average profit multiplier to arrive at a value.

However, the Cost Approach has a fundamental flaw: cost does not equal value. A company could spend billions developing a drug that ultimately fails to gain market acceptance, making its R&D cost a sunk cost with little relation to its future earning potential. Conversely, a highly successful drug could generate revenues that are orders of magnitude greater than its development cost. For this reason, the Cost Approach is rarely used as a primary valuation method. Its main utility is as a “sanity check” or a conservative valuation “floor,” providing a baseline against which the more optimistic projections of the Income and Market approaches can be compared.

Table 2: Comparison of Core Valuation Methodologies

Choosing the right valuation tool is critical for any forecasting task. The following table summarizes the key characteristics, use cases, and limitations of the three core methodologies, providing a quick-reference guide for the strategic analyst.

| Methodology | Primary Use Case | Key Inputs | Strengths | Weaknesses |

| Income Approach | Primary valuation for pipeline assets, M&A, licensing, and portfolio management. | Epidemiology, market penetration, pricing, patent life, clinical risk, discount rate.1 | Directly links value to future cash generation; highly detailed and flexible for scenario analysis. | Highly sensitive to assumptions; can be complex and time-consuming to build. |

| Market Approach | Cross-validating DCF models; valuing assets in active markets with many transactions. | Precedent M&A deals, licensing terms, public company market caps.1 | Grounded in real-world market prices and investor sentiment; relatively quick to apply. | Dependant on the availability of truly comparable assets; can be misleading for novel therapies. |

| Cost Approach | Sanity check for other methods; early-stage valuation when future cash flows are highly uncertain. | Historical R&D expenditures, development costs.1 | Simple to calculate; provides a conservative, tangible valuation floor. | Ignores market potential and profitability; cost does not equal value. |

Section 3: The Algorithmic Edge – Revolutionizing Forecasting with AI and Predictive Analytics

For decades, pharmaceutical sales forecasting was an art form heavily reliant on the intuition of seasoned experts and the limitations of traditional statistical models. The landscape is now undergoing a seismic shift, driven by the exponential power of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML). These technologies are transforming forecasting from a practice of educated guesswork into a data-driven science, capable of processing immense and disparate datasets to uncover predictive patterns that were previously invisible to the human eye.

The Old Guard: Limitations of Traditional Statistical Models

The traditional forecaster’s toolkit was dominated by time-series models like ARIMA (Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average), Holt-Winters, and various forms of exponential smoothing.16 These methods work by analyzing historical sales data to identify trends, seasonality, and patterns, and then extrapolating those patterns into the future.

While useful for mature products with stable sales histories, these models have a critical Achilles’ heel: they are fundamentally backward-looking. Their reliance on historical data makes them notoriously poor at predicting sales for new drug launches, where no history exists. They also struggle to account for dynamic, non-linear market events, such as the launch of a new competitor, a sudden shift in clinical practice, or the complex interplay of physician prescribing behavior and patient demographics.19 In the volatile and rapidly evolving pharmaceutical market, relying solely on these models is like trying to drive a car by looking only in the rearview mirror.

The New Frontier: Machine Learning and AI-Driven Forecasting

AI and machine learning represent a paradigm shift. Instead of being limited to a single stream of historical sales data, ML algorithms can ingest and analyze vast, unstructured datasets from a multitude of sources with unparalleled speed and accuracy.19 This creates a much richer and more holistic view of the market.

An AI-driven forecasting model can simultaneously process:

- Historical Sales Data: The traditional input, but now just one piece of the puzzle.

- Physician Prescribing Patterns: Data on which doctors are prescribing which drugs to which types of patients.

- Patient Demographics and EHRs: Anonymized data from electronic health records to understand disease progression and patient journeys.

- Clinical Trial Data: Information on a drug’s efficacy, safety, and trial design.

- Patent Data: The full text of patent filings, including claims and legal history.

- External Factors: Economic indicators, social media sentiment, and even weather patterns.

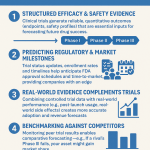

By analyzing these diverse inputs, ML models can identify complex, non-linear relationships and subtle correlations that would elude traditional methods. The results speak for themselves. Studies have shown that advanced ML models, such as Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks, consistently outperform traditional ARIMA models in forecasting pharmaceutical sales.16 One particularly powerful model, which combined Natural Language Processing (NLP) analysis of patent documents with clinical trial data, achieved an impressive 89% accuracy in predicting the first-year sales for 78 new molecular entities. This is the new frontier of forecasting.

Unlocking Predictive Indicators from Patent Data

One of the most exciting applications of AI in this domain is its ability to unlock the predictive power hidden within the patent data itself. Using techniques like NLP, AI can “read” and interpret patent filings at a massive scale, extracting quantitative signals that correlate strongly with future commercial success. This moves patent analysis from a qualitative legal assessment to a quantitative input for forecasting models.

Key predictive indicators that can be extracted from patent data include:

- Patent Family Size & International Filings: A patent “family” consists of a set of patents filed in various countries to protect a single invention. The size and geographic breadth of a patent family is a strong proxy for the company’s perceived value of the asset and its global commercial ambitions. A company simply does not spend the immense resources required to file and maintain patents in dozens of countries for a minor product. Research has quantified this relationship, showing a strong positive correlation between patent family size and future sales (a correlation coefficient, or r, of 0.71) and between the number of international filings and sales (r=0.63).

- Claim Language & Breadth: The “claims” section of a patent is the legally operative part that defines the boundaries of the invention. NLP algorithms can analyze the text of these claims to gauge their breadth and scope. Broader claims generally offer stronger protection. More importantly, AI can identify specific linguistic patterns within the patent text that correlate with commercial outcomes. One study found that analyzing the language patterns in patent specifications could explain 67% of the variance in eventual sales volumes (an R-squared value of 0.67), improving forecast accuracy by 32% compared to models that did not use this data.

- Filing Timing: The timing of patent filings relative to a drug’s FDA approval is another critical signal. While foundational patents are filed early, a significant number of secondary patents for top-selling drugs—72%, according to one analysis—are filed after the drug is already on the market. This post-approval patenting activity is a clear indicator of an aggressive lifecycle management strategy and correlates with longer periods of market exclusivity, directly impacting the revenue forecast.

Deeper Insights: The Emergence of “Predictive Due Diligence”

The convergence of AI, diverse data streams, and sophisticated modeling is giving rise to a powerful new capability in the world of pharmaceutical mergers and acquisitions: Predictive Due Diligence. This represents a fundamental evolution from the traditional due diligence process.

Historically, M&A due diligence has been a reactive and backward-looking exercise. The acquirer’s team would meticulously review the target company’s existing assets—its patent portfolio, its clinical trial results, its financial statements—to verify their status and identify any red flags.24 The central question was, “What does the target company

have?”

AI-powered models are changing the question to, “What will the target company’s assets become?” As we’ve seen, machine learning models can now predict the future outcomes of clinical trials and the likelihood of regulatory approval with a high degree of accuracy. One landmark study achieved an Area Under the Curve (AUC)—a measure of a model’s predictive power—of 0.78 for predicting the transition from Phase 2 to approval and 0.81 for the transition from Phase 3 to approval. These models incorporate dozens of features, including drug characteristics, trial design, and the sponsor’s track record, to generate a probability of success for each pipeline asset.26

Now, imagine combining this capability with the patent-based sales forecasting models discussed earlier. An acquirer can now build a comprehensive, multi-layered forecast that models not just the potential revenue of a drug if it gets approved, but the probability-weighted expected revenue of the target’s entire pipeline. They can run simulations that account for the likelihood of clinical failure, the strength of the patent portfolio, and the competitive landscape.

This transforms due diligence from a simple validation exercise into a proactive, predictive strategic analysis. An acquirer can now identify hidden risks that may not be reflected in the target’s own valuation, such as a high probability of trial failure for a key asset. They can spot undervalued assets that have a higher-than-appreciated chance of success. This fundamentally changes the power dynamic in M&A negotiations, allowing acquirers to make more informed, data-driven decisions and to price deals with a level of confidence that was previously unattainable. This is the future of strategic assessment in the pharmaceutical industry.

Section 4: Defending the Fortress – Patent Thickets, Evergreening, and Lifecycle Management

In an ideal world, a pharmaceutical company would launch a new drug with two decades of market exclusivity ahead of it. In the real world, as we’ve established, the effective patent life is often brutally short—sometimes less than a decade.4 This stark economic reality creates a powerful strategic imperative: to defend and extend the period of monopoly for as long as legally possible. This is the domain of lifecycle management, a sophisticated and often controversial set of strategies designed to maximize the return on investment from a successful drug. The two most prominent and debated tactics in this arsenal are “evergreening” and the creation of “patent thickets.”

The Strategic Imperative: Why Lifecycle Management is Not Optional

The immense pressure to engage in lifecycle management stems directly from the “innovation gap” and the patent cliff. Developing a new blockbuster drug is a long, expensive, and uncertain process. When a company’s major revenue-generating drug goes off-patent, the resulting sales collapse can create a massive hole in its finances that its current R&D pipeline may not be ready to fill. To bridge this gap and maintain revenue streams, companies are financially compelled to find ways to extend the commercial life of their existing, proven assets.5 This is not merely a matter of maximizing profit; for many companies, it is a matter of corporate survival, funding the next wave of innovation, and satisfying shareholder expectations.

Defining the Tactics: Evergreening and Patent Thickets

While often used interchangeably, evergreening and patent thickets are distinct but related strategies aimed at the same goal: delaying generic competition.

- Evergreening: This is the broad strategy of obtaining new, later-expiring patents on minor modifications or improvements to an existing drug.5 The goal is to create a continuous chain of patent protection that extends well beyond the expiration of the original composition of matter patent. Common evergreening tactics include 4:

- New Formulations: Developing an extended-release version, a different salt form, or a new delivery system (like a transdermal patch).

- New Dosages: Patenting a new strength or dosing regimen.

- New Indications: Securing method-of-use patents for treating new diseases.

- Enantiomers: Patenting a single, purified isomer of a drug that was previously sold as a mixture.

- Product Hopping: Just before a patent expires, the company might pull the old version of the drug from the market and heavily promote a newly patented, slightly modified version, forcing patients and doctors to switch.

- Patent Thickets: This is a specific and highly effective form of evergreening. It involves filing a dense, overlapping, and interlocking web of dozens or even hundreds of patents around a single product.5 The objective is not necessarily that each individual patent is unassailable, but that the sheer volume and complexity of the “thicket” creates an insurmountable barrier for a potential generic competitor.10 To launch their product, the generic company would have to challenge and invalidate

every single patent in the thicket—a process that is astronomically expensive, time-consuming, and fraught with legal risk. The brand-name company, in contrast, only needs to win on one patent to block competition. This asymmetry makes challenging a well-constructed patent thicket a daunting, and often losing, proposition.

Case Study in Focus: AbbVie’s Humira – The Masterclass in Exclusivity Extension

There is no better illustration of these strategies in action than AbbVie’s handling of its mega-blockbuster drug, Humira (adalimumab). The Humira case is studied in business schools and legal circles as a masterclass in aggressive and highly successful lifecycle management.

Humira, a biologic drug used to treat a range of autoimmune diseases, was first approved by the FDA in 2002. Its primary composition of matter patent was set to expire in the U.S. in 2016. By traditional forecasting logic, this should have been the date of its patent cliff. However, AbbVie executed a brilliant and relentless patenting strategy to defend its prized asset.

- The Thicket: Over the course of two decades, AbbVie built an unprecedented patent thicket around Humira. It filed for over 257 patents, of which more than 130 were granted by the USPTO.5 Critically, 90% of these patents were filed

after Humira was already on the market, covering every conceivable aspect of the product: dozens of manufacturing and process patents, new formulations (including a high-concentration, citrate-free version that was less painful to inject), and multiple method-of-use patents for new indications.5 - The Result: This impenetrable thicket successfully delayed the entry of any biosimilar competitors in the lucrative U.S. market until 2023—a full seven years after the primary patent expired. This extension allowed AbbVie to generate well over $100 billion in additional U.S. sales, making Humira the best-selling drug in history.5

While Humira is the most prominent example, this is an industry-wide practice. Celgene’s Revlimid, a cancer treatment, is protected by a thicket of 96 patents, potentially extending its monopoly to 40 years. Amgen’s Enbrel has used a similar strategy to protect its market until at least 2029. These cases demonstrate that for many of today’s top drugs, the primary patent expiration date is merely a historical footnote.

The Impact on Forecasting: Modeling the “Thicket Effect”

For the sales forecaster, the existence of patent thickets renders a simple, single-patent analysis dangerously naive. Relying on the expiration date of the composition of matter patent alone will lead to a grossly inaccurate forecast, predicting a patent cliff years before it will actually occur.

Instead, analysts must adopt a more sophisticated, qualitative approach to model the “thicket effect.” This involves:

- Portfolio Assessment: Conducting a thorough analysis of the target drug’s entire patent portfolio, not just the base patent. This can be done using databases like the FDA’s Orange Book and the USPTO’s public search tools, or more efficiently through commercial platforms like DrugPatentWatch.

- Strength and Density Analysis: Evaluating the number of patents, their types (process and formulation patents are often key to a thicket), their filing dates, and their geographic coverage.

- Litigation History Review: Assessing the company’s track record in defending its patents. Is it known for being highly litigious and settling on favorable terms?

- Jurisdictional Analysis: Understanding the legal environment in key markets. As will be discussed in the next section, a patent thicket that is formidable in the U.S. may be far less effective in Europe or India.

Based on this qualitative assessment, the analyst must then make a judgment call, creating a risk-adjusted LOE forecast. This might involve modeling several scenarios: a “best case” for the brand company where the thicket holds up for its maximum duration, a “worst case” where a key patent is invalidated early, and a “most likely” case based on legal precedent and competitive dynamics. This qualitative overlay is an essential correction to the quantitative DCF model.

Deeper Insights: The Ethical Tightrope and the Inevitability of Scrutiny

While these lifecycle management strategies are often legally permissible, particularly in the United States, they walk a precarious ethical tightrope and inevitably attract intense public, political, and regulatory scrutiny. This scrutiny has become a material risk factor that must be incorporated into any long-term forecast.

Critics, including patient advocates, healthcare providers, and lawmakers, frequently label these practices as “patent abuse,” “gaming the system,” and exploiting “legal loopholes”.12 The core argument is that these strategies prioritize extending a profitable monopoly over the public health goal of ensuring patient access to affordable medicines.29 When a company secures a new patent for a minor formulation change that offers little to no additional therapeutic benefit, it is seen as undermining the very purpose of the patent system, which is to reward genuine innovation.30

This ethical and political blowback is not just a matter of public relations; it translates into tangible business risks. Regulatory bodies and courts are increasingly taking action. The U.S. Federal Trade Commission (FTC) has actively challenged “pay-for-delay” settlements, where brand-name companies pay generic manufacturers to delay market entry, as violations of antitrust law. There is ongoing legislative pressure in the U.S. Congress to reform patent law to make it more difficult to obtain the types of secondary patents that form the basis of many thickets.28

Therefore, a company like AbbVie, whose revenue has been overwhelmingly dependent on the strength of the Humira patent thicket, faces a significant, non-clinical risk: the risk of legal or regulatory intervention that could dismantle that thicket faster than a purely patent-based analysis would predict. A sophisticated forecaster must recognize this. The valuation of a drug protected by a dense thicket cannot be based on patent law alone. It must also incorporate a scenario analysis that models the potential impact of a successful antitrust challenge, a change in patent law, or a shift in judicial interpretation. This elevates the forecast beyond the realm of science and law and into the complex world of political and regulatory risk analysis—a crucial, third-order consideration for any credible long-term valuation.

“In an industry where regulatory decisions can make or break a product’s commercial success, pharmaceutical companies that systematically analyze competitors’ regulatory strategies gain a significant advantage. Our research shows that companies with mature competitive intelligence functions are 62% more likely to achieve first-pass regulatory approvals compared to those with limited competitive monitoring capabilities.”

– McKinsey & Company Pharmaceutical Practice, 2024 Industry Report on Competitive Intelligence.

Section 5: Global Chess – How Jurisdictional Differences Shape Patent Strategy

A critical error in patent-based sales forecasting is to view the world through a single legal lens. The global pharmaceutical market is not a monolith; it is a complex chessboard of varying national laws, regulatory practices, and judicial philosophies. A patent strategy that is a guaranteed checkmate in the United States may be an illegal move in India and a questionable gambit in Europe. Therefore, a credible global sales forecast cannot be a simple extrapolation of a U.S. model. It must be a carefully constructed mosaic, built from a deep understanding of the unique patent landscape in each major jurisdiction.

Why a Global Forecast Requires a Local Lens

The viability and effectiveness of lifecycle management strategies like evergreening and patent thickets are not universal. They are profoundly shaped by the specific rules of each country’s patent office and court system. What constitutes a patentable “invention,” how patent challenges are adjudicated, and the balance struck between innovator rights and public health can differ dramatically from one region to another. This means that the “thicket effect” discussed in the previous section has a different magnitude in different markets, leading to different Loss of Exclusivity (LOE) dates and, consequently, different revenue forecasts for the same drug in different parts of the world.

The United States: A Fertile Ground for Patent Thickets

The U.S. has long been considered the most favorable environment for innovator pharmaceutical companies to build and defend extensive patent portfolios. Several features of the American legal and regulatory system contribute to this reality:

- The Hatch-Waxman Act: This landmark 1984 law, designed to balance innovator incentives with generic competition, created a “patent linkage” system that has been masterfully exploited to delay generic entry. When a generic company files an application challenging a brand’s patents (a “Paragraph IV certification”), the brand company can trigger an automatic 30-month stay on the generic’s FDA approval simply by filing a patent infringement lawsuit.3 This provides a powerful incentive to list numerous secondary patents in the FDA’s Orange Book, as each one can be used to trigger this delay.

- The BPCIA for Biologics: The Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act, which governs biosimilars, is even more favorable to innovators. It places no statutory limit on the number of patents a brand company can assert in litigation against a biosimilar challenger, creating the perfect conditions for building massive patent thickets for large-molecule drugs.

- Permissive Patent Examination: The USPTO has historically been criticized for being relatively permissive in granting patents on incremental innovations, such as new formulations or methods of use, which might not meet the stricter “inventive step” requirements in other jurisdictions.

- High Cost of Litigation: The sheer cost and complexity of patent litigation in U.S. federal courts acts as a major deterrent. Facing a thicket of dozens of patents, a generic challenger must be prepared to spend tens of millions of dollars with no guarantee of success, making settlement an often more attractive economic option.

The European Union: A More Restricted Environment

In stark contrast, the European Union presents a much more challenging terrain for building and maintaining dense patent thickets. The legal framework in Europe contains structural barriers that limit the effectiveness of many U.S.-style strategies.

- Stricter Patentability Standards: The European Patent Office (EPO) applies a more rigorous standard for “inventive step” and “novelty”. It is generally more difficult to obtain patents on minor, incremental modifications that do not demonstrate a clear and non-obvious technical advantage over the prior art.

- The “Added Matter” Doctrine: This is perhaps the most critical difference. Article 123(2) of the European Patent Convention (EPC) strictly prohibits amending a patent application to include subject matter that was not “directly and unambiguously derivable” from the application as it was originally filed. This doctrine effectively prevents the U.S. practice of incrementally broadening claims through a series of “continuation” applications, which is a key technique for building a sprawling patent family from a single initial invention.

- Supplementary Protection Certificates (SPCs): Instead of relying on a patchwork of secondary patents for term extension, the EU uses a more streamlined sui generis right called an SPC. This provides a single, predictable extension of up to five years for a specific approved product to compensate for regulatory delays, offering clarity and reducing the incentive for thicket-building.

The practical consequence of these differences is profound. It is the primary reason why biosimilar versions of Humira launched in Europe in 2018, a full five years before they reached the U.S. market. For a global forecaster, this means the LOE date for Europe will almost always be earlier than the LOE date for the U.S. for a drug protected by a significant patent thicket.

Key Asian Markets: India and China

The major Asian markets present their own unique and evolving landscapes.

- India: The Anti-Evergreening Bastion: India has deliberately charted a course that prioritizes public health and its domestic generic drug industry. The key to its approach is Section 3(d) of the Indian Patents Act. This provision, unique in global patent law, explicitly states that new forms of a known substance are not patentable unless they demonstrate a significant enhancement in “known efficacy.” The Indian Supreme Court has interpreted “efficacy” to mean “therapeutic efficacy,” setting an extremely high bar for secondary patents. A new formulation that is merely more convenient or stable is unlikely to be patented. This provision makes India one ofthe most difficult jurisdictions in the world for evergreening and has been instrumental in ensuring early access to affordable generic medicines for its population.

- China: The Evolving Powerhouse: China’s intellectual property landscape has undergone a dramatic transformation. Once viewed as a haven for infringement, it has rapidly built a robust patent enforcement regime with specialized IP courts that are gaining a reputation for efficiency. In a significant move, China recently implemented a U.S.-style patent linkage system (in 2021) and a patent term extension (PTE) system.4 This adoption of Western-style legal mechanisms provides the necessary infrastructure for more sophisticated lifecycle management strategies. While dense thickets are not yet as common as in the U.S., the legal framework is now in place, creating the potential for them to emerge as a major factor in the Chinese market in the coming years.

Deeper Insights: Jurisdictional Arbitrage as a Competitive Strategy

The profound differences in global patent law do not just create challenges for forecasters; they create strategic opportunities for both brand and generic companies. This gives rise to a sophisticated game of jurisdictional arbitrage, where companies strategically leverage the strengths and weaknesses of different legal systems to gain a global competitive advantage.

A generic or biosimilar manufacturer, for instance, can use a favorable ruling in a jurisdiction with strict patentability standards as a powerful weapon. If the EPO or an Indian court invalidates a key secondary patent, that decision, while not legally binding elsewhere, becomes a highly persuasive piece of evidence. It can be brandished in litigation and settlement negotiations in other countries, including the U.S., to argue that the patent is weak and likely to be invalidated there as well. This can significantly increase the pressure on the brand company to settle on terms that are more favorable to the generic challenger.

Furthermore, a generic company can choose to launch its product “at risk” (i.e., before all patent litigation is resolved) in a jurisdiction where it perceives the brand’s patents to be weakest or where the court system is fastest. This allows it to gain a first-mover advantage, establish a market presence, and begin generating revenue that can be used to fund the more arduous and expensive legal battle in the United States.

Conversely, a brand-name company can use the formidable strength of its U.S. patent thicket as a global deterrent. The sheer cost and risk of challenging the thicket in the U.S. can make potential competitors hesitant to even launch in other, less protected markets, for fear of provoking a massive and financially draining lawsuit from a deep-pocketed opponent.

This interconnectedness means that a global sales forecast cannot be treated as a simple sum of independent regional forecasts. The system is dynamic. A legal event in one jurisdiction—a patent invalidation in Germany, a compulsory license in India—can have a direct and immediate ripple effect on the probability of generic entry, the likely timeline, and the potential for settlement in every other jurisdiction. Advanced forecasting models must therefore attempt to capture this complex interplay, modeling not just individual market dynamics but also the cross-jurisdictional contagion of legal and commercial events.

Section 6: The Intelligence Engine – Essential Tools and Data Sources

Accurate forecasting is impossible without accurate and comprehensive data. In the world of pharmaceutical patents, analysts have access to a wealth of information, ranging from free, publicly available government databases to sophisticated commercial intelligence platforms that aggregate and analyze data to provide a competitive edge. Knowing where to look and how to use these tools effectively is a fundamental skill for any strategist in this space.

The Public Domain: Foundational Patent Databases

The cornerstone of any patent analysis is the data provided by government regulatory and patent-granting bodies. These public resources are the definitive sources of information and are essential for any due diligence or forecasting exercise.

The FDA’s Orange Book

The “Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations,” universally known as the Orange Book, is the bible for U.S. pharmaceutical patent information. Published by the FDA, it is the authoritative database that officially links approved drug products to the patents that their manufacturers claim cover them, as well as any applicable regulatory exclusivities.3

- How to Use It: The Orange Book can be searched online via the FDA’s website by a drug’s trade name, active ingredient, applicant company, or application number.

- What It Contains: It provides a treasure trove of critical data for forecasters, including: patent numbers and their expiration dates, the type of patent (e.g., drug substance vs. drug product), and specific “patent use codes” that describe the particular method of use a patent covers. It also lists all regulatory exclusivities and their expiration dates.

- Limitations: It’s crucial to remember what the Orange Book does not contain. It does not list patents covering manufacturing processes, unapproved uses (off-label indications), or metabolites. Therefore, relying on it exclusively will provide an incomplete picture of a drug’s full patent protection.

The USPTO Database

While the Orange Book links drugs to patents, the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) database is the definitive source for the patent documents themselves.3 This is where an analyst goes to read the full text of a patent and understand the precise scope of its protection.

- How to Use It: The USPTO’s Patent Public Search tool is a powerful, web-based application that allows for both basic and advanced searching.3 A basic search can quickly find a patent by its number, inventor, or assignee (the company that owns it).

- What It Contains: The advanced search function allows for highly granular queries of the full patent text. An analyst can search specifically within the “claims” section (.clm.) to understand the legal boundaries of the invention, or review the entire “prosecution history” (the back-and-forth between the applicant and the patent examiner) to identify potential weaknesses in the patent. This deep dive is essential for assessing the strength of a patent thicket.

WIPO PATENTSCOPE & Espacenet

In today’s global market, a U.S.-only analysis is insufficient. WIPO’s PATENTSCOPE and the European Patent Office’s Espacenet are the primary gateways to international patent information.36

- How to Use Them: These databases allow users to search for patents filed across dozens of national and regional patent offices. A key feature is their ability to identify “patent families”—all the different national patents that relate to a single invention.3

- What They Contain: For a forecaster, these tools are indispensable for assessing a company’s global patent strategy. By mapping out where a company has chosen to file for protection, an analyst can infer its global commercial priorities. The presence of a large, geographically diverse patent family is a strong indicator of a high-value asset, a predictive signal that can be fed directly into forecasting models. WIPO’s Pat-INFORMED initiative is another valuable resource, providing a straightforward way to check the patent status of essential medicines in specific countries, which is particularly useful for procurement agencies.

The Commercial Edge: Leveraging Specialized Intelligence Platforms

While public databases provide the raw data, they can be cumbersome to search and require significant expertise to connect the dots between different sources. This is where commercial intelligence platforms provide a significant competitive edge. These platforms invest heavily in aggregating, cleaning, standardizing, and linking data from dozens of global sources—patent offices, regulatory agencies, clinical trial registries, company filings, and more—into a single, user-friendly interface.39

These platforms transform raw data into actionable intelligence, saving analysts countless hours of manual work and enabling a much deeper level of analysis. They provide tools for landscape mapping, competitor tracking, and identifying trends that would be nearly impossible to spot using public sources alone.

A Spotlight on DrugPatentWatch

Among the specialized platforms in this space, DrugPatentWatch is a prime example of a tool designed specifically to meet the needs of the pharmaceutical forecaster and strategist. Its services directly align with the core tasks discussed throughout this report, making it a powerful engine for turning patent data into competitive advantage.

The platform provides a fully integrated, web-based database covering a wide spectrum of business intelligence for both small-molecule and biologic drugs. Its key value lies in connecting disparate pieces of information to create a holistic picture.11 For a given drug, an analyst can quickly access:

- Comprehensive Patent Data: Both U.S. and international patent information, including expiration dates, litigation status, and links to patent documents. This includes a valuable database of expired patents for historical analysis.

- Regulatory Status: Detailed information on a drug’s FDA approval status and exclusivities.

- Competitive Landscape: Information on generic and API suppliers, first-time generic entrants, and drugs currently in development, allowing for robust competitor analysis.41

- Forecasting and Portfolio Management Tools: The platform is explicitly designed to help users anticipate patent expirations, identify market entry opportunities, manage R&D portfolios, and forecast future budget requirements.11 With dedicated dashboards for biologics and small molecules, and features like daily email alerts, it enables proactive monitoring of the competitive environment.

In essence, a platform like DrugPatentWatch acts as an intelligence aggregator and amplifier. It takes the foundational data from public sources like the Orange Book and the USPTO and enriches it with international data, competitive context, and analytical tools, helping to translate the complex world of patents into clear, actionable business insights.

Table 3: Key Pharmaceutical Patent Databases at a Glance

An analyst’s workflow often requires querying multiple databases to build a complete intelligence picture. This table serves as a quick-reference guide, outlining which database is best suited for answering specific strategic questions.

| Database | Primary Function | Key Information Provided | Strategic Use in Forecasting |

| FDA Orange Book | Official U.S. linkage between approved drugs, patents, and exclusivities. | U.S. patent numbers, expiration dates, patent use codes, all regulatory exclusivity data.3 | The definitive first stop for determining the baseline U.S. LOE date for a small-molecule drug. |

| USPTO Public Search | Definitive source for full-text U.S. patent documents and legal history. | Full patent text, legal claims, prosecution history, patent assignments (ownership). | Essential for deep-dive analysis of patent strength, assessing the density of a thicket, and identifying legal vulnerabilities. |

| WIPO PATENTSCOPE / EPO Espacenet | Gateways to international patent filings and global patent families.37 | International patent applications (PCT), national filings in multiple countries, patent family data.3 | Crucial for assessing global patent strategy, identifying international LOE dates, and using family size as a predictive sales indicator. |

| Commercial Platforms (e.g., DrugPatentWatch) | Integrated business intelligence and analytics for the global pharma market. | Aggregated patent, regulatory, clinical trial, and supplier data; analytical tools; alerts.11 | Accelerates analysis, provides competitive context, and turns raw data into actionable intelligence for portfolio management and forecasting. |

Section 7: Navigating the Fog – Challenges, Limitations, and the Future of Forecasting

While the tools and methodologies for patent-based sales forecasting have become incredibly sophisticated, it is crucial to approach the task with a healthy dose of humility. The pharmaceutical market is a complex, dynamic system, and the future is inherently uncertain. No model, no matter how advanced, can predict events with perfect accuracy. Understanding the inherent challenges and limitations of forecasting is just as important as mastering the techniques themselves. At the same time, the relentless pace of technological advancement points toward an exciting future where the fog of uncertainty may begin to lift.

The Inherent Uncertainty: Why All Forecasts are Wrong (But Some are Useful)

The famous aphorism from statistician George Box holds particularly true in pharmaceutical forecasting. The path from patent to profit is littered with unpredictable events that can render even the most carefully constructed forecast obsolete overnight.

- Pervasive Forecasting Inaccuracy: The industry’s track record is a testament to this challenge. One analysis of 50 U.S. prescription drugs revealed staggering disparities between forecasted and actual sales in the first five years after launch. A mere 12% of forecasts were accurate within a 25% margin. A substantial 32% of drugs were overestimated by more than double their actual sales, while another 28% were underestimated by the same margin. This level of inaccuracy highlights the immense difficulty of the task.

- Key Challenges and Limitations:

- Unpredictable Clinical Outcomes: The single greatest source of uncertainty is the clinical trial process. A promising drug can fail unexpectedly in Phase III due to unforeseen safety issues or a lack of efficacy, instantly wiping out its projected value.

- Regulatory Whims: Regulatory agencies can shift their standards, delay decisions, or issue unexpected Complete Response Letters, throwing off timelines and development plans.

- Data Quality and Gaps: AI models are only as good as the data they are trained on. Fragmented, incomplete, or inaccurate data from sources like EHRs can lead to flawed predictions.19

- The “Black Box” Problem: Some advanced AI models can be opaque, making it difficult for analysts to understand why the model made a particular prediction. This lack of interpretability can be a major barrier to adoption in a highly regulated and risk-averse industry.

- Market Dynamics: The competitive landscape can change in an instant with the launch of a rival product, a shift in the standard of care, or new pricing pressures from payers.

The Future Trajectory: AI, Big Data, and Quantum Computing

Despite these challenges, the future of forecasting is bright, driven by the continued convergence of AI, big data, and emerging computational technologies. The field is moving towards ever more integrated and predictive models.

- Deeper Data Integration: The next generation of forecasting models will seamlessly integrate an even wider array of data types. This includes Real-World Evidence (RWE) from insurance claims and patient registries, genomic and proteomic data to enable precision medicine forecasts, social media sentiment analysis to gauge patient and physician attitudes, and real-time supply chain logistics to model demand more accurately.22

- The Rise of Generative AI: Generative AI is poised to have a transformative impact, with McKinsey estimating it could unlock between $60 billion and $110 billion in annual value for the industry. Its applications go far beyond forecasting. GenAI can accelerate the very beginning of the R&D process by designing novel molecules from scratch. For the forecaster and strategist, it can act as a powerful analytical assistant, capable of instantly summarizing thousands of pages of clinical trial data, earnings call transcripts, or competitive intelligence reports, dramatically speeding up the research process.22

- The Quantum Leap: On the distant horizon, quantum computing holds the potential for a true revolution. The sheer complexity of mapping a global patent landscape with thousands of interconnected patents is a task that pushes the limits of classical computers. Quantum computers, with their ability to perform calculations at an exponentially faster rate, could one day process these vast landscapes almost instantaneously, enabling near real-time portfolio valuation and scenario analysis on a scale that is unimaginable today.

Deeper Insights: The Human-AI Symbiosis

With the rise of these powerful technologies, it is tempting to imagine a future where human analysts are rendered obsolete, replaced by all-knowing algorithms. This vision, however, misses the most crucial point. The future of elite pharmaceutical forecasting is not about AI replacing humans; it is about the creation of a powerful human-AI symbiosis.

AI models are masters of scale and correlation. They can sift through petabytes of data and identify patterns that no human ever could.1 An AI can tell you

that a large, geographically diverse patent family is strongly correlated with high future sales. But it struggles to understand why. It lacks context, causal reasoning, and strategic intuition.

This is where the human analyst remains indispensable. A skilled analyst, armed with the knowledge and frameworks presented in this report, understands the “why” behind the correlation. They know that the large patent family is not the cause of the high sales, but rather that both are the result of a single underlying factor: the company has identified a high-value asset and is executing a well-funded, aggressive global commercialization and lifecycle management strategy.

The human analyst understands the nuances that are difficult, if not impossible, to quantify and feed into an algorithm. They can assess the political and reputational risk of a controversial patent thicket. They can factor in the known biases of a particular patent examiner or the litigation history of a specific federal judge. They can interpret the strategic intent behind a competitor’s M&A move, a subtle shift in their marketing message, or a key opinion leader’s comments at a medical conference.

In this symbiotic relationship, the AI does the heavy lifting of data processing and pattern recognition, providing the “what.” The human analyst provides the critical layer of strategic context, qualitative judgment, and ethical oversight, answering the all-important question: “so what?” The ultimate competitive advantage in the future will not belong to the company with the most powerful AI model, but to the company with the most skilled team of analysts who can wield these incredible tools to their fullest potential. This human-AI collaborative intelligence is the true and lasting future of the field.

Conclusion: The Patent as a Strategic Compass

The journey through the world of patent-based pharmaceutical sales forecasting reveals a landscape of remarkable complexity and dynamism. We have seen how the patent has evolved from a simple legal shield into a sophisticated strategic weapon, and how the art of forecasting has transformed from a practice of historical extrapolation into a science of predictive, AI-driven modeling.

The central themes of this report underscore a new reality for business professionals in the pharmaceutical and biotech sectors. First, the concept of market exclusivity is a multifaceted construct, built upon the intricate interplay of different patent types and a complex web of regulatory protections. A naive focus on a single patent’s expiration date is a recipe for strategic failure. Second, the valuation of these assets requires a multi-pronged approach, where the robust, cash-flow-based Income Approach is validated and informed by the real-world benchmarks of the Market Approach.

Third, and most critically, the advent of artificial intelligence has irrevocably changed the game. AI-powered models, capable of integrating vast and varied datasets, have unlocked a new level of predictive accuracy. They can extract meaningful signals from the very language of patent claims and the global patterns of their filing, turning legal documents into quantitative inputs for revenue forecasts. This has given rise to a new era of “predictive due to diligence,” fundamentally altering how companies assess risk and opportunity in M&A and licensing.

Finally, we have seen that this entire process is played out on a global chessboard, where the rules change from one jurisdiction to the next. The aggressive lifecycle management strategies that are commonplace in the United States are structurally constrained in Europe and legally prohibited in India. This necessitates a nuanced, multi-jurisdictional perspective that recognizes the strategic game of arbitrage played by both brand and generic competitors.

In this high-stakes, high-risk environment, where billions of dollars in revenue hang in the balance, the ability to navigate the complexities of the global patent system is not just a valuable skill—it is the most reliable compass a company can possess. By mastering the principles and techniques outlined in this report, strategists can learn to read the patent landscape not as a static map of the past, but as a dynamic, predictive guide to the future, charting a clear course toward sustained commercial success.

Key Takeaways

- Effective Patent Life is the Key Metric: The true window of revenue-generating monopoly is the effective patent life (typically 7-12 years post-launch), not the 20-year statutory term. The erosion of this period by R&D and regulatory review is the primary driver of aggressive lifecycle management.

- Portfolio Composition Predicts Revenue Shape: The mix of patent types in a portfolio is a powerful predictive indicator. A portfolio dominated by method-of-use patents suggests a “pipeline-in-a-product” strategy and a different, more prolonged revenue curve than one anchored by a single composition of matter patent.

- AI is a Forecasting Game-Changer: AI- and ML-driven models that integrate patent data, clinical trial results, and market information significantly outperform traditional statistical methods, with some models achieving up to 89% accuracy in predicting first-year sales.

- Patent Thickets Redefine Exclusivity: For many blockbuster drugs, the Loss of Exclusivity (LOE) date is determined not by the primary patent but by the strength and density of a “patent thicket.” Forecasting requires a qualitative assessment of this entire portfolio, not a simple date check.

- Jurisdiction Dictates Strategy: Patent law is not globally uniform. The legal environments in the U.S., Europe, and India are fundamentally different, dictating which lifecycle management strategies are viable. A global forecast must be built on a jurisdiction-specific analysis.

- Aggressive Tactics Carry Reputational Risk: While often legal, strategies like evergreening and patent thickets attract significant political and regulatory scrutiny. This “headline risk” is a material factor that must be incorporated into long-term forecasts and company valuations.

- The Future is Human-AI Symbiosis: The ultimate competitive advantage will not come from AI alone, but from skilled human analysts who can leverage AI’s computational power while providing the essential layers of strategic context, causal reasoning, and ethical oversight.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. How can a small biotech with a limited budget effectively analyze the patent thicket of a large pharma competitor?

For a smaller company, tackling a large pharma’s patent thicket head-on in court is often financially impossible. However, they can employ a more strategic, “guerilla” approach. First, they should leverage free and low-cost databases (USPTO, Espacenet) to map the thicket and identify the patents with the earliest expiration dates or seemingly weakest claims. Second, they can focus their analysis on jurisdictions with stricter patentability standards, like Europe or India. A successful challenge or invalidation of a key patent at the EPO can provide significant leverage in global settlement negotiations. Third, they can use commercial intelligence platforms like DrugPatentWatch on a subscription basis to efficiently track the litigation status and prosecution history of the patents, looking for vulnerabilities without incurring massive legal fees. The goal is not to fight every battle, but to find the weakest link in the chain and apply focused pressure.

2. What is the “generic paradox,” and how does the entry of a generic competitor sometimes lead to a price increase for the branded drug?

The “generic paradox” is a counterintuitive market phenomenon where the list price of a brand-name drug actually increases after the first one or two generic competitors enter the market. This occurs because the market bifurcates. The new generics capture the most price-sensitive segment of the market (e.g., large health plans and PBMs that mandate generic substitution). The brand-name manufacturer is left with a smaller, but more price-insensitive, “brand loyal” customer base, which may include patients who are hesitant to switch or physicians who continue to prescribe the brand out of habit. To maximize revenue from this remaining loyal segment, the brand manufacturer may strategically raise the list price, knowing these customers are less likely to switch based on price alone. This strategy is only viable in the short term, as the brand’s market share will continue to erode as more generics enter and competition intensifies.

3. How is the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) in the US expected to change the calculus of patent-based sales forecasting?

The IRA introduces government price negotiation for certain high-spend drugs covered by Medicare, fundamentally altering the financial landscape. For forecasting, this has two major impacts. First, for drugs selected for negotiation, the IRA will lower the “peak” revenue a drug can achieve during its exclusive life. This means the “patent cliff” may become less steep, as the price from which the drug falls will already be lower. Second, it could potentially weaken the incentive for generic and biosimilar manufacturers to challenge patents. The profitability of launching a generic is based on the price difference between the brand and the generic. If the IRA has already forced the brand’s price down, the potential profit margin for a generic is squeezed, which may make the high cost of patent litigation less economically viable. Forecasters will need to model these new dynamics, including the probability of a drug being selected for negotiation and the likely extent of the price reduction.

4. Beyond sales forecasting, how can patent analysis inform R&D and clinical trial design?

Patent analysis is a powerful tool for R&D strategy. By conducting a “freedom to operate” (FTO) analysis early in the development process, a company can identify potential patent roadblocks from competitors and design its research program to “invent around” them, avoiding costly infringement down the line. Furthermore, analyzing the patent landscape of a particular therapeutic area can reveal “white space”—areas of unmet need with limited competitive activity, guiding R&D investment toward more promising targets.35 For clinical trial design, monitoring competitors’ patents and their trial results (via registries like ClinicalTrials.gov) can provide valuable intelligence. For example, if a competitor’s trial for a similar drug failed due to a specific safety signal, a company can proactively design its own trial to monitor for and mitigate that specific risk.

5. What are the key differences in patenting and forecasting for small-molecule drugs versus large-molecule biologics?