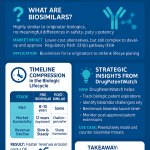

Executive Summary

The advent of biosimilars represents the most significant structural shift in the biopharmaceutical landscape since the Hatch-Waxman Act established the small-molecule generic drug market. More than a simple pricing challenge, the introduction of highly similar, lower-cost alternatives to blockbuster biologic drugs is acting as a powerful catalyst, fundamentally reshaping the strategies, priorities, and operational models of innovator research and development (R&D) pipelines. This report provides an exhaustive analysis of this transformation, examining how the scientific, regulatory, economic, and intellectual property dimensions of biosimilar competition are forcing a profound recalibration within originator biopharmaceutical companies.

The central thesis of this analysis is that biosimilars are not merely a late-stage, lifecycle management concern but a primary driver of strategic change that permeates the entire R&D continuum, from early-stage target selection to late-stage clinical development and manufacturing. The certainty of a finite, and often fiercely contested, period of market exclusivity for new biologics has elevated the importance of speed, efficiency, and true innovation to a strategic imperative.

This report begins by establishing the foundational science of biologics, biosimilars, and the emerging category of “bio-betters,” clarifying the critical distinctions that underpin the entire competitive dynamic. It then navigates the complex and divergent global regulatory frameworks of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA), highlighting how differences in exclusivity periods, interchangeability standards, and patent resolution processes create distinct strategic challenges for global R&D programs.

An in-depth economic analysis reveals the dual nature of the biosimilar impact: while generating substantial system-level healthcare savings, market access in the U.S. is often dictated by the complex interplay of rebates and formulary decisions managed by Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs). This dynamic can blunt the full competitive force of biosimilars and creates a “patient cost paradox,” where system savings do not consistently translate to lower out-of-pocket costs for patients.

The core of the report dissects the direct and indirect impacts on the innovator R&D pipeline. The analysis demonstrates that biosimilar pressure is creating an “innovation squeeze,” polarizing R&D strategy. On one end, it forces investment towards higher-risk, truly novel, first-in-class modalities where scientific differentiation is paramount. On the other, it incentivizes sophisticated, defensive R&D programs to develop patentable “bio-betters” that aim to transition the market to an improved product before the original faces biosimilar competition. The middle ground of incremental, “me-too” biologics is becoming increasingly untenable.

Finally, the report outlines the modern innovator’s playbook, detailing advanced lifecycle management strategies, the strategic use of patent thickets, and the rise of originator-led biosimilar divisions. Through detailed case studies of the Humira and Remicade markets, these strategies are illustrated in real-world contexts. The report concludes with forward-looking projections on the future of competition for cell and gene therapies and provides actionable strategic recommendations for R&D leaders, investors, and policymakers to navigate this evolving landscape successfully.

Section 1: The New Biopharmaceutical Paradigm: Biologics and Their High-Similarity Counterparts

The modern therapeutic landscape has been irrevocably altered by the rise of biologic medicines. These complex therapies have provided transformative treatments for diseases previously considered intractable. Their success, however, has given rise to a new class of competitors—biosimilars—and a new strategic evolution—bio-betters. Understanding the fundamental scientific and structural differences between these categories is essential to comprehending their impact on the biopharmaceutical R&D pipeline.

1.1 The Age of Biologics: Defining a Revolution in Medicine

Biological products, or biologics, represent a diverse and powerful class of medicines derived not from chemical synthesis but from living systems.1 These systems can include microorganisms, plant cells, or animal cells, which are genetically engineered to produce therapeutic substances.3 Unlike small-molecule drugs, which are typically composed of a defined number of atoms and have a well-characterized structure, biologics are large, complex molecules. Their composition can include sugars, proteins, nucleic acids, or intricate combinations thereof, and in some cases, they are living entities themselves, such as cells and tissues.2

The sheer scale and complexity of biologics are defining characteristics. For instance, a simple protein like insulin has a molecular weight of approximately 5,808 daltons, while a complex monoclonal antibody can exceed 150,000 daltons.5 This complexity means that their complete structure is often difficult, if not impossible, to fully characterize.2 Consequently, the manufacturing process for a biologic is inextricably linked to the final product itself—a principle widely known in the industry as “the product is the process”.6 These biotechnical processes, which involve cell culture and purification, are highly sensitive to minor variations in conditions. As a result, slight, acceptable differences between manufactured lots of the same biologic are normal and expected.1 Regulatory agencies like the FDA meticulously assess a manufacturer’s process and control strategy to manage this inherent within-product variability.1

This unique nature has enabled biologics to achieve a level of specificity that is often unattainable with small-molecule drugs. They can be designed to target specific molecules, cells, or pathways with remarkable precision, which minimizes off-target effects and reduces the risk of damaging healthy tissues.3 This has made them indispensable in precision medicine and for treating a wide array of complex, chronic, and often life-threatening conditions, including many forms of cancer, autoimmune disorders like rheumatoid arthritis and Crohn’s disease, and rare genetic diseases for which no other treatments were previously available.3

1.2 Deconstructing Biosimilarity: More Than a Generic, A Scientific Endeavor

The success and high cost of originator biologics created a strong incentive for the development of follow-on versions after their patents and exclusivity periods expired. However, due to the inherent complexity and manufacturing variability of biologics, creating an exact replica, as is done with small-molecule generic drugs, is scientifically impossible.5 This fundamental distinction gave rise to the concept of the biosimilar.

A biosimilar is a biological product that is “highly similar” to an already-approved biologic, known as the “reference product.” Crucially, a biosimilar must also have “no clinically meaningful differences” from its reference product in terms of safety, purity, and potency.1 The term “potency” encompasses the product’s safety and effectiveness.10 This “highly similar, not identical” standard is the cornerstone of biosimilar regulation and the primary reason why a biosimilar is not considered a “generic” of a biologic.5

To gain regulatory approval, a biosimilar developer cannot simply demonstrate that its product contains the same active ingredient. Instead, it must conduct a comprehensive “comparability exercise” designed to prove biosimilarity based on the “totality of the evidence”.6 This rigorous, stepwise process is designed to leverage the extensive safety and efficacy data already established for the reference product, thereby avoiding the ethical and financial burden of unnecessarily duplicating large-scale clinical trials.5 The process typically unfolds as follows:

- Extensive Analytical Characterization: This is the foundation of the biosimilarity assessment. The developer uses a battery of state-of-the-art analytical techniques to conduct a head-to-head comparison of the structural and functional attributes of its proposed biosimilar and the reference product. This includes assessing the primary amino acid sequence, higher-order structure and conformation, post-translational modifications, purity, and biological activity.1 A wide array of methods are employed, such as liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS), nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), and various cell-based assays.13

- Non-Clinical Studies: Animal studies are conducted to assess toxicity and other parameters to further support the demonstration of similarity.14

- Clinical Pharmacology Studies: Human pharmacokinetic (PK) and pharmacodynamic (PD) studies are performed to compare how the biosimilar and reference product are absorbed, distributed, metabolized, and excreted by the body (PK), and the physiological response they elicit (PD). An assessment of clinical immunogenicity—the potential for the product to provoke an unwanted immune response—is also a critical component.1

- Additional Clinical Studies: If any residual uncertainty remains after the preceding steps, regulatory agencies may require additional clinical studies, including comparative efficacy trials, to confirm that there are no clinically meaningful differences.1

This evidence-based pyramid, with its heavy reliance on foundational analytical data, allows regulators to be confident that the approved biosimilar can be used as safely and effectively as its reference product for its approved indications.12

The table below provides a clear, at-a-glance visualization of the fundamental differences between small molecules, biologics, and their respective follow-on products, underscoring the scale of complexity that defines the biologic and biosimilar landscape.

| Parameter | Small-Molecule Drug | Generic Drug | Biological Drug | Biosimilar Drug | |

| Synthesis | Chemical synthesis | Copy of original chemical formula | Gene insertion into a cell clone | Development derived from original biological molecule | |

| Molecular Size | 100–1,000 Da | 100–1,000 Da | 10,000–300,000 Da | 10,000–300,000 Da | |

| Glycosylation | None | None | Often present and complex | Must be highly similar to reference | |

| Molecular Structure | Simple, well-defined | Identical to original | Complex, heterogeneous | Highly similar to reference | |

| Immunogenicity | Low | Low | Medium to high | Must be comparable to reference | |

| Development Time | 7–10 years | 1–3 years | 10–15 years | 6–9 years | |

| Development Cost | >$2B (novel) | Low | >$2B (novel) | $100M–$300M | |

| Data synthesized from sources: 8 |

1.3 The Rise of the “Bio-better”: Innovating on an Innovation

The competitive pressure introduced by biosimilars has spurred a new avenue of innovation for originator companies, leading to the development of “bio-betters.” It is important to note that “bio-better” is a marketplace term, not a formal regulatory designation recognized by agencies like the FDA.20 A bio-better, also known as a biosuperior, is a new molecular entity that is based on an existing, successful biologic but has been deliberately engineered to improve upon its properties.20

Unlike a biosimilar, which aims for high similarity, a bio-better is intentionally different. The goal is to create a demonstrably superior product by enhancing specific attributes.23 These improvements can take many forms, including:

- Enhanced Efficacy: Altering the molecule to increase its binding affinity or therapeutic effect.24

- Improved Safety Profile: Modifying the structure to reduce toxicity or immunogenicity.21

- Greater Convenience: Improving pharmacokinetics to allow for less frequent dosing (e.g., extending the drug’s half-life), or developing a more convenient route of administration (e.g., a subcutaneous injection to replace an intravenous infusion).20

These modifications are achieved through advanced protein engineering techniques, such as altering the amino acid sequence, modifying glycosylation patterns, creating fusion proteins that combine the biologic with a carrier protein to extend its half-life, or attaching polymers like polyethylene glycol (PEGylation).3

Because a bio-better is a new, deliberately altered molecule and not a “highly similar” copy, it cannot utilize an abbreviated approval pathway. It must undergo the full, rigorous Biologics License Application (BLA) process required for any novel drug, including a full complement of preclinical and clinical trials to establish its own safety and efficacy profile.20 While this represents a significant R&D investment, it carries a crucial strategic advantage: a successful bio-better is considered a new invention and is eligible for its own patents, granting the developer a fresh period of market exclusivity.24 This ability to create a new, patent-protected product from an existing platform makes the development of bio-betters a powerful lifecycle management strategy and a direct R&D response to the threat of biosimilar competition.

Section 2: The Regulatory Gauntlet: Global Pathways Shaping Market Entry

The pathway from a laboratory concept to a marketed biologic or biosimilar is governed by a complex web of regulations that vary significantly across major global markets. The frameworks established by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) are the most influential, and their differences in philosophy and procedure create distinct strategic landscapes for drug developers. These regulatory divergences are not merely administrative hurdles; they directly shape R&D planning, investment decisions, and the timelines for market entry.

2.1 Pioneering the Path: The EMA’s Centralized Framework and the Concept of Interchangeability

The European Union has been at the forefront of biosimilar regulation. The EMA established the first comprehensive legal and scientific framework for biosimilars in 2005, pioneering a pathway that has since shaped global development.13 This proactive approach led to the approval of the world’s first biosimilar, Omnitrope (somatropin), in 2006.12 As a result, the EU has approved the highest number of biosimilars worldwide and has amassed over a decade of extensive clinical experience regarding their use and safety.12

A key feature of the EMA’s system is its centralized approval procedure. For nearly all biologics and biosimilars, which are produced using biotechnology, a single marketing authorization application is submitted to the EMA. A positive scientific opinion from the EMA’s relevant committees, such as the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP), leads to a marketing authorization granted by the European Commission that is valid across all EU member states.9 This streamlined process provides a predictable and efficient route to a vast, unified market.

The EMA’s regulatory framework for reference biologics provides for an “8+2+1” year period of protection. An originator biologic is granted eight years of data exclusivity, during which a biosimilar manufacturer cannot reference the originator’s data in an application. This is followed by two years of market exclusivity, meaning a biosimilar cannot be launched until at least ten years after the reference product’s initial authorization.5 An additional year of market exclusivity can be granted if the originator develops a significant new indication during the first eight years.

On the critical issue of interchangeability, the EMA and the Heads of Medicines Agencies (HMA) have adopted a clear scientific stance. They have emphasized that any biosimilar approved in the EU is considered scientifically interchangeable with its reference product, or with another biosimilar of the same reference product.5 This means a physician can prescribe a biosimilar in place of the reference product (or vice versa) with the same expectation of safety and efficacy. However, the practical implementation of this principle, specifically the authority for pharmacists to perform automatic substitution at the pharmacy level without consulting the prescriber, is not governed by the EMA. Instead, this decision is delegated to the national authorities of individual member states, resulting in a varied landscape of substitution policies across Europe.9

2.2 The BPCIA and the U.S. Market: Navigating the Abbreviated Pathway, Exclusivity, and the “Patent Dance”

The United States established its regulatory pathway for biosimilars significantly later than Europe. The Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA) was signed into law in 2010 as part of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act.10 Modeled loosely on the Hatch-Waxman Act for small-molecule generics, the BPCIA was designed to balance two competing goals: creating an abbreviated pathway to facilitate the market entry of lower-cost biosimilars and preserving strong incentives for originator companies to continue investing in the high-risk, high-cost R&D of novel biologics.10

The BPCIA amended the Public Health Service Act to create an abbreviated Biologics License Application (aBLA) pathway, codified under section 351(k).10 This pathway allows a biosimilar applicant to rely in part on the FDA’s previous finding of safety and efficacy for the reference product, provided they can demonstrate biosimilarity through the “totality of the evidence” approach.14

Several key provisions of the BPCIA create a unique and complex regulatory and legal environment in the U.S.:

- Data Exclusivity: The BPCIA grants innovator biologics a 12-year period of data exclusivity from the date of first licensure.6 This is one of the longest exclusivity periods in the world and a significant point of difference from the EU’s system. During this time, the FDA cannot approve a 351(k) application for a biosimilar. This extended protection provides a substantial, guaranteed period for innovators to recoup their R&D investments.

- Interchangeability: Unlike the EMA’s approach, the BPCIA created a distinct and higher regulatory standard for a product to be designated as “interchangeable.” To achieve this status, a biosimilar applicant must not only demonstrate biosimilarity but also provide additional data, typically from a switching study, to prove that the product can be alternated with the reference product without any increased risk or diminished efficacy.1 An interchangeable designation is highly coveted because it permits automatic substitution at the pharmacy level, much like a generic drug, subject to individual state pharmacy laws.1 However, the high evidence bar and the confusion this two-tiered system (biosimilar vs. interchangeable) can create among physicians and patients have been cited as potential barriers to uptake.6

- The “Patent Dance”: The BPCIA established a highly structured, pre-litigation process for identifying and resolving patent disputes, colloquially known as the “patent dance”.29 This complex series of timed information exchanges begins after a biosimilar developer’s aBLA is accepted for review by the FDA. The process requires the biosimilar applicant to provide its application and manufacturing process information to the reference product sponsor (RPS). This is followed by both parties exchanging lists of patents they believe could be infringed, along with detailed legal arguments regarding infringement, validity, and enforceability. The process is designed to narrow the scope of potential litigation to a specific list of patents that can be contested before the biosimilar is launched.29 This formal, legally intensive process makes patent strategy and litigation an integral and early part of the biosimilar development and launch process in the U.S.

2.3 A Comparative Analysis: Key Differences in FDA vs. EMA Approaches and the Implications for Global Development

For a biopharmaceutical company aiming to market a product globally, the differences between the FDA and EMA frameworks are not academic—they have profound strategic implications for R&D. A single, unified global development program is often impossible; instead, companies must navigate a bifurcated path tailored to the unique demands of each regulatory superpower.

The table below summarizes the key differences between the two regulatory pathways, highlighting the critical factors that influence global R&D strategy.

| Regulatory Aspect | FDA (United States) | EMA (European Union) | |

| Governing Legislation | Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA) of 2009 | Directive 2001/83/EC, established framework in 2005 | |

| Pathway Created | Abbreviated BLA (aBLA) under 351(k) | Centralised Procedure for “Similar Biological Medicinal Products” | |

| Years of Experience | First biosimilar approved 2015 | First biosimilar approved 2006 | |

| Data Exclusivity | 12 years for reference biologic | 8 years for reference biologic | |

| Market Exclusivity | Contained within 12-year data exclusivity | 10 years total (+1 year for new indication) | |

| Interchangeability | Separate, higher standard requiring additional switching studies for automatic pharmacy substitution | Scientific principle; all approved biosimilars are considered interchangeable for prescribing. Pharmacy substitution is a national decision. | |

| Patent Resolution | Formal, pre-litigation “Patent Dance” | No equivalent formal process; patent disputes handled through national courts | |

| Reference Product Sourcing | U.S.-licensed product required. Use of non-U.S. product requires extensive “bridging studies.” | E.U.-authorized product preferred, but non-E.U. product may be acceptable with justification. | |

| Data synthesized from sources: 5 |

The strategic implications of these differences are significant. The FDA’s longer 12-year exclusivity period provides a more substantial and predictable runway for innovators to earn a return on their R&D investment, which may influence decisions on whether to pursue very high-cost, high-risk projects. Conversely, the highly litigious nature of the U.S. system, institutionalized through the “patent dance,” means that legal and patent strategy must be deeply integrated into R&D planning from the earliest stages.

Perhaps the most direct impact on the execution of R&D programs is the FDA’s stringent requirement for reference product sourcing. A company developing a biosimilar for the global market often uses an EU-sourced reference product for its clinical trials. To gain approval in the U.S., that company must then conduct costly and time-consuming “bridging studies”.9 These are typically three-way comparative studies: the proposed biosimilar versus the U.S.-licensed reference product, the proposed biosimilar versus the EU-approved reference product, and a direct comparison of the U.S. and EU reference products to each other.9 This requirement adds a significant layer of complexity, cost, and time to global development programs, forcing companies to run parallel or sequential studies that would be unnecessary in a harmonized regulatory environment.

Section 3: The Economic Shockwave: How Biosimilar Competition is Remodeling the Market

The introduction of biosimilars was predicated on a simple economic principle: competition drives down prices. While this has proven true at a systemic level, the actual market dynamics are far from simple. The flow of savings is mediated by powerful intermediaries, particularly Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs) in the U.S., creating a complex landscape where system-wide benefits do not always align with the financial realities for individual patients. This economic structure has profound implications for the competitive pressure felt by innovator companies and, consequently, for the urgency and direction of their R&D pipelines.

3.1 Quantifying the Impact: Realized and Projected Healthcare Savings

The economic impact of biosimilars on healthcare spending is substantial and growing. By providing lower-cost alternatives to some of the most expensive medicines, biosimilars introduce direct price competition that benefits payers and the healthcare system as a whole. Projections consistently point to massive savings. One analysis estimated that biosimilars would reduce direct spending on biologics in the U.S. by $54 billion between 2017 and 2026.31 Other forecasts are even more optimistic, suggesting potential savings of approximately $100 billion between 2020 and 2024, and over $133 billion by 2025.8

These savings are driven primarily by price reductions. Biosimilars typically enter the market at a list price 15% to 35% lower than their reference product.27 However, in highly competitive situations, such as the market for adalimumab (Humira), some biosimilars have launched with discounts as steep as 85% off the originator’s list price.36 This competition not only offers a lower-cost alternative but also forces the originator manufacturer to lower its own net price through rebates and discounts to maintain market share.37

The real-world impact is already evident. In Europe, where the biosimilar market is more mature, biosimilar competition has led to significant budget relief, amounting to an estimated €56 billion in cumulative savings.38 In the U.S., health systems that have actively implemented biosimilar substitution programs have reported substantial savings. For example, one health system forecasted annual savings of approximately $500,000 from switching patients from originator infliximab to its biosimilar.39 A network of community oncology practices saved an estimated $47 million in a six-month period through biosimilar substitution.35 These figures demonstrate that where biosimilars are adopted, the potential for cost containment is immense.

3.2 The PBM-Payer Nexus: How Rebates, Formularies, and Market Access Dictate Uptake

In the U.S. healthcare system, the theoretical benefits of price competition do not always translate directly into market share for the lowest-priced product. The uptake of biosimilars is heavily influenced by the decisions of payers (insurance companies) and the PBMs that manage prescription drug benefits on their behalf.36 These entities act as powerful gatekeepers, controlling which drugs are included on their formularies (lists of covered drugs) and at what level of patient cost-sharing.35

A central feature of this system is the “rebate wall,” a market dynamic that can perversely incentivize the use of higher-priced originator biologics over lower-priced biosimilars.36 The mechanism works as follows: an originator manufacturer with a high list price for its biologic can offer a substantial, confidential rebate to a PBM in exchange for preferred placement on its formulary. The PBM’s revenue and profits can be tied to the size of this rebate. A biosimilar may enter the market with a much lower list price, but if it cannot offer a rebate that is more financially attractive to the PBM than the originator’s, the PBM may choose to keep the originator biologic in the preferred position, effectively blocking the biosimilar from gaining market access.36

The adalimumab (Humira) market provides a stark case study of this phenomenon. Despite the launch of multiple biosimilars in 2023 with deep discounts, Humira retained over 97% of the market volume through the first year.42 This was largely because PBMs and payers continued to prefer the high-rebate originator product, leaving little incentive for physicians or patients to switch.36

This dynamic is beginning to evolve as PBMs themselves devise new strategies. The recent co-promotion agreement between Sandoz (a biosimilar manufacturer) and Cordavis (a subsidiary of CVS Caremark, a major PBM) for the biosimilar Hyrimoz represents a potential paradigm shift. In this model, the PBM’s financial interests are directly aligned with the success of a specific biosimilar, leading Caremark to place Hyrimoz on its major formularies and “remove” Humira.42 This strategy resulted in a dramatic and immediate increase in Hyrimoz’s market share, demonstrating that PBM formulary control is the single most powerful lever for biosimilar uptake in the U.S. market.42

3.3 The Patient Cost Paradox: Examining the Disconnect Between System Savings and Out-of-Pocket Expenses

One of the most concerning aspects of the current biosimilar market is the disconnect between the massive savings generated for the healthcare system and the costs experienced by individual patients. Multiple studies have now confirmed that the availability of biosimilars has not consistently led to lower out-of-pocket (OOP) costs for patients, a phenomenon that can be termed the “patient cost paradox”.43

A large cohort study published in JAMA Health Forum analyzed claims for seven biologics and found that, overall, annual patient OOP spending did not decrease after the start of biosimilar competition.45 In fact, for several of the drugs studied, patient costs were either higher or showed no significant change.44 The study also found that while the average OOP cost per claim was slightly lower for biosimilars compared to originators ($707 vs. $911), patients using a biosimilar were paradoxically

more likely to have some OOP cost than those using the reference product.44

There are several reasons for this paradox:

- Complex Insurance Design: Patient cost-sharing is determined by the specifics of their insurance plan, including deductibles, copayments, and coinsurance. For drugs covered under the medical benefit (like many infused biologics), a patient’s cost may be a percentage of the amount reimbursed by the insurer, which can be much higher than the drug’s acquisition cost.45 Because of this complexity, system-level price reductions do not automatically translate to lower patient copays.

- Formulary Tiering: PBMs and payers may place biosimilars on non-preferred formulary tiers that carry higher patient cost-sharing as a way to steer patients towards the originator biologic for which they receive a large rebate.41 This practice directly undermines the affordability promise of biosimilars for patients.

- Lack of Patient Awareness and Confidence: Surveys show that many patients are unfamiliar with biosimilars and express significant concern about “non-medical switching”—being forced by their insurer to switch from a stable, effective originator biologic to a biosimilar for purely financial reasons.47 A 2019 survey found that 85% of patients did not want to switch if their current biologic was working, and 83% were concerned that switching could cause more adverse effects.47 When the financial benefit to the patient is minimal or non-existent, this reluctance is magnified.

This failure to pass savings on to patients not only limits affordability and access but also dampens a key driver of biosimilar adoption. Without a clear cost advantage for the end user, both patients and physicians may be hesitant to move away from a trusted and effective reference product, further slowing uptake and muting the competitive pressure on innovators.

The structure of the U.S. pharmaceutical market, particularly the role of PBMs and the rebate system, creates an “economic shield” for innovator biologics. This system effectively blunts the full competitive force that low-cost biosimilars were intended to exert. The logic unfolds as follows: the primary purpose of the BPCIA was to introduce price competition to reduce healthcare costs.10 In a purely price-driven market, this economic pressure would compel innovator companies to rapidly advance their R&D pipelines to generate new, patent-protected revenue streams to offset the sharp decline in sales of their off-patent biologics. However, the rebate system disrupts this direct link. An innovator facing biosimilar competition can offer a large rebate on its originator product directly to a PBM. In exchange, the PBM can maintain the originator’s preferred status on its formulary, effectively limiting the market access of a lower-list-price biosimilar.36 This allows the innovator’s revenue from the originator drug to decline much more gradually than it would in a truly competitive market. The feared “patent cliff” becomes a more manageable “patent slope.” Because this immediate financial threat is less severe, the corresponding pressure on the R&D organization to take radical, high-risk actions is diminished. The innovator is afforded more time and resources to pursue more conservative R&D strategies, such as developing bio-betters or focusing on indication expansion for existing products, rather than being forced to abandon entire franchises and make massive bets on unproven, first-in-class science. In this way, the rebate system indirectly subsidizes the longevity of existing products and lessens the urgency for disruptive R&D pipeline transformation.

Section 4: The Core Analysis: Direct and Indirect Impacts on the Innovator R&D Pipeline

The emergence of a viable biosimilar market is not merely a commercial or legal challenge for innovator companies; it is a strategic inflection point that forces a fundamental re-evaluation of the entire research and development enterprise. The finite and increasingly predictable endpoint of a biologic’s profitable lifecycle instills a new sense of urgency and discipline that permeates every stage of the R&D pipeline, from initial target selection to the adoption of cutting-edge development technologies.

4.1 The Recalibration of Risk: How the “Patent Cliff” Influences Early-Stage Target Selection and Investment

The most profound impact of biosimilars is felt at the very beginning of the R&D process: the strategic decision of where to invest billions of dollars in development capital. The “patent cliff”—the point at which a blockbuster drug loses exclusivity and faces a sharp decline in revenue—is no longer a distant event to be managed by a lifecycle team. It is now a critical variable embedded in the Net Present Value (NPV) and risk-assessment models for every potential R&D project.49 This has led to a significant recalibration of risk and reward in early-stage portfolio management.

A primary consequence is a strategic shift towards true novelty. The business case for developing “me-too” biologics—drugs that offer only incremental improvements over existing therapies in a crowded class—is rapidly eroding. The prospect of launching a new, expensive biologic into a therapeutic area where the standard of care is about to be commoditized by biosimilars makes it nearly impossible to recoup the enormous development costs, which can exceed $2.6 billion for a novel biologic.8 This reality is forcing R&D organizations to deprioritize such projects and instead focus their resources on first-in-class molecules with novel mechanisms of action. The scientific and clinical differentiation must be significant enough to justify premium pricing and create a strong competitive moat that is not easily replicated.50

Simultaneously, this new risk calculus has increased the attractiveness of developing drugs for niche indications and rare diseases. While the potential market size for an orphan drug is smaller, the likelihood of facing biosimilar competition is also lower. The smaller patient population and specialized manufacturing may make the investment case for a biosimilar developer unattractive, creating a “biosimilar void”.38 This means the innovator company may enjoy a period of

de facto market exclusivity that extends well beyond the statutory 12-year period, significantly improving the long-term return on investment and making these projects more appealing to both internal decision-makers and external investors.

Overall, the bar for greenlighting a new biologic development program has been raised. The heightened competitive landscape means that a project must demonstrate not only promising science but also a clear path to market, a robust and defensible intellectual property strategy, and a compelling value proposition that can withstand future price pressures.17

4.2 Accelerate or Perish: The Imperative to Shorten Development Timelines and Reduce Costs

With a finite period of market exclusivity, maximizing the time a product is on patent before biosimilar entry becomes a primary strategic goal. This has placed immense pressure on R&D organizations to accelerate development timelines and increase operational efficiency. A typical biosimilar takes six to nine years and costs $100 million to $300 million to develop.17 For a novel biologic, the timeline is over a decade.8 Any reduction in this timeline translates directly into additional months or years of peak sales revenue.

According to a detailed analysis by McKinsey, leading companies are pursuing a multi-pronged approach to accelerate their R&D processes, with the goal of cutting timelines from transfection to Investigational New Drug (IND) application by 30% to 50%.17 Key strategies include:

- Process Optimization: This involves redesigning the development workflow to run steps in parallel rather than sequentially. For example, downstream purification process development can begin before upstream cell culture optimization is fully complete. Companies are also eliminating non-critical steps, such as certain intermediate scale-up stages, and adopting standardized platform approaches for elements like formulation to avoid reinventing the wheel for each new molecule.17

- Strategic Outsourcing: Innovator companies are increasingly partnering with Contract Development and Manufacturing Organizations (CDMOs) and Contract Research Organizations (CROs) to manage specific activities or entire development programs. This allows the innovator to focus internal resources on its core scientific competencies while leveraging the specialized expertise, technology, and capacity of its partners. This can reduce timelines, spread costs, and provide flexibility to manage fluctuating workloads.17

- Proactive Regulatory Engagement: Companies are working more closely with regulatory agencies to streamline clinical development. This includes seeking waivers for large and costly Phase III trials when a robust body of analytical, PK, and PD data can sufficiently demonstrate a product’s profile. This trend, if it continues to expand, could dramatically reduce both the cost and time required for development.17

4.3 The Shifting Focus of Innovation: Prioritizing Complex Modalities and Manufacturing Technology

The threat of biosimilar replication is pushing innovator R&D pipelines toward therapeutic platforms and manufacturing technologies that are inherently more difficult to copy. This represents a strategic move to raise the scientific and technical barriers to entry for potential competitors.

There is a clear trend of increasing R&D investment in next-generation biologics, such as antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs), bispecific antibodies, and cell and gene therapies.38 These modalities are significantly more complex to design, develop, and manufacture than traditional monoclonal antibodies, making the task of demonstrating “high similarity” for a would-be biosimilar developer far more challenging. This strategic shift is reflected in broad industry investment patterns, where biologics R&D spending is growing at three times the rate of small-molecule R&D.18 In 2023, biologics accounted for approximately 40% of total pharmaceutical sales, a share that is projected to continue growing.7

This trend is accompanied by a renewed strategic focus on manufacturing technology as a source of competitive advantage. Because “the process is the product,” owning proprietary, highly optimized cell lines, novel purification techniques, or advanced formulation technologies can be a powerful differentiator. These process innovations can be protected by their own patents, adding layers to a product’s IP shield.54 Furthermore, a highly sophisticated and unique manufacturing process makes it more difficult for a competitor to reverse-engineer the product and achieve the degree of analytical similarity required for regulatory approval, thus delaying or even deterring biosimilar development.56

4.4 The Digital Transformation of Biologic R&D: Leveraging AI, In Silico Modeling, and Advanced Analytics as a Competitive Necessity

The intense pressures for speed, efficiency, and innovation are accelerating the adoption of digital technologies across the biologic R&D landscape. These tools are no longer considered optional efficiency aids but are becoming core strategic capabilities necessary for competition.

- Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML): AI algorithms are being deployed to accelerate drug discovery by analyzing vast “omics” datasets and clinical literature to identify novel therapeutic targets.57 In development, ML models can predict formulation stability and other outcomes, analyze complex analytical data to generate a “similarity score” between a biosimilar and its reference product, and de-risk the development process by identifying potential issues earlier.15

- In Silico Modeling and Digital Twins: The use of computer simulations to model biological processes and experiments is becoming more common. “Digital twins” can be used to simulate and optimize manufacturing process parameters, such as cell culture media selection or fermentation conditions, significantly reducing the time and expense of physical, trial-and-error experimentation in the lab.17

- Advanced Process Control: Frameworks like Quality-by-Design (QbD) and Process Analytical Technology (PAT) are being implemented to build quality and consistency into the manufacturing process from the very beginning.15 By using real-time sensors and data analytics to monitor critical process parameters, manufacturers can ensure that the final product consistently meets its quality attributes. This is vital for innovators seeking to create a robust, defensible process and equally critical for biosimilar developers striving to precisely match the characteristics of a reference product.15

The emergence of biosimilars is creating an “innovation squeeze” that is fundamentally polarizing R&D strategy within innovator companies. The traditional middle ground of developing incrementally improved, “me-too” biologics in large, established therapeutic classes is becoming the most strategically perilous territory. The business model for such a product relies on capturing a portion of a massive market and enjoying a long period of patent protection to recoup development costs. Biosimilars effectively dismantle this model. Once the original reference product for a class (e.g., an anti-TNF biologic) faces multi-source biosimilar competition, the price structure for the entire therapeutic class is likely to collapse.34 Launching a new, high-priced, patent-protected “me-too” biologic into a market on the verge of commoditization is a losing long-term proposition; the window of profitability is simply too narrow to justify the investment.

This pressure forces a strategic bifurcation in the R&D pipeline. The first path is to “go high”—to pursue truly disruptive, first-in-class science. This involves targeting novel biological pathways or developing highly complex new modalities like cell and gene therapies.38 The scientific risk is substantially higher, but a successful outcome creates an entirely new market and a new reference product, resetting the 12-year exclusivity clock with no immediate competitors. The second path is a sophisticated, “defensively-offensive” strategy: to develop a “bio-better”.20 This approach involves taking an existing successful biologic that is nearing patent expiry and creating a new, demonstrably superior, and separately patentable version. This is a lower-risk scientific endeavor as the biological target and basic molecular structure are already well understood. The strategic goal is to proactively switch the market to this superior product

before biosimilars for the original version can launch, effectively rendering the reference product obsolete and moving the competitive goalposts. The “innovation squeeze” thus makes the comfortable middle ground of incrementalism untenable, forcing R&D leaders to choose between high-risk, paradigm-shifting “moonshots” and sophisticated, market-defending “fortification” through the development of bio-betters.

Section 5: The Innovator’s Playbook: Strategic Responses to a Competitive Future

In the face of inevitable biosimilar competition, innovator biopharmaceutical companies are no longer passive participants waiting for patent cliffs. They have developed a sophisticated and multi-faceted playbook of strategic responses that integrate R&D, intellectual property law, and commercial operations. These strategies are designed to maximize the value of their innovations, delay the entry of competitors, and shape the competitive landscape to their advantage.

5.1 Lifecycle Management in the Biosimilar Era: Beyond Simple “Evergreening”

Lifecycle Management (LCM) has evolved from a late-stage marketing tactic into a long-range, proactive strategy that is initiated years, or even a decade, before a biologic is expected to lose exclusivity.6 The goal is to build a fortress of clinical and legal protection around a valuable asset. Simple strategies of the past, such as minor tweaks to a formulation, are no longer sufficient to deter motivated biosimilar competitors. Modern LCM is a comprehensive portfolio of integrated tactics.6

One of the most powerful LCM strategies is the creation of a “patent thicket.” This involves filing a dense web of secondary patents that go far beyond the core composition of matter patent for the biologic molecule itself. These patents can cover a wide range of inventions, including specific formulations, manufacturing processes, purification techniques, methods of use for specific indications, and drug delivery devices.32 The purpose of a patent thicket is to create a complex and costly legal minefield for a biosimilar challenger. Even if the core patent expires, the biosimilar developer may still have to litigate dozens of secondary patents, a process that can delay their market entry by years and add millions to their development costs.32

Other key LCM strategies that directly involve the R&D pipeline include:

- Strategic Indication Expansion: R&D resources are allocated to test an existing biologic in new diseases, particularly in orphan or rare disease populations. A successful new indication not only adds a new revenue stream but can also, in some jurisdictions, provide additional periods of marketing exclusivity.50

- Development of New Delivery Systems and Formulations: This is a cornerstone of modern LCM. R&D efforts are focused on creating new, patent-protected versions of a drug that offer a clear clinical benefit to patients and physicians. This could involve developing a subcutaneous formulation of a drug that was previously only available as an intravenous infusion, or creating an auto-injector device with improved ergonomics. These innovations are not just defensive; they create tangible value that can help retain market share even after biosimilars for the original formulation become available.3

The table below outlines the primary LCM strategies employed by innovators, detailing the specific tactics and, most importantly, their direct impact on the R&D pipeline.

| Strategy Category | Specific Tactic | Description | Example(s) | Impact on R&D Pipeline | |

| Defensive IP | Patent Thicket Creation | Filing numerous secondary patents on manufacturing, formulation, and methods of use to create legal barriers for biosimilar entry. | AbbVie’s >100 patents on Humira | Requires R&D to continuously innovate and document novel aspects of manufacturing and formulation to support new patent applications. | |

| Offensive R&D | Strategic Indication Expansion | Conducting clinical trials to gain approval for the biologic in new therapeutic areas, especially orphan diseases. | Avastin’s approval in ovarian cancer | Initiates new Phase II/III clinical trial programs within the pipeline for the existing asset. | |

| Offensive R&D | New Formulation / Delivery Device | Developing a new version with improved patient convenience, such as a subcutaneous formulation or an on-body injector. | Neulasta Onpro (pegfilgrastim on-body injector) | Requires significant formulation development, device engineering, and new clinical/human factors studies. | |

| Offensive R&D | Development of a “Bio-better” | Engineering a new, molecularly distinct version of the biologic with superior clinical properties (e.g., longer half-life). | Kadcyla (based on Herceptin) | Necessitates a full, de novo BLA development program, from preclinical through Phase III, for a new molecular entity. | |

| Corporate Strategy | Entering the Biosimilar Market | Establishing an internal division or acquiring a company to develop and market biosimilars of competitors’ products. | Amgen’s biosimilar portfolio (e.g., Amjevita) | Creates a separate R&D pipeline focused on reverse-engineering and demonstrating similarity, requiring different skill sets and resource allocation. | |

| Data synthesized from sources: 6 |

5.2 The Strategic Pivot to Bio-betters: Creating Defensible, Differentiated Value

The development of bio-betters represents the most proactive and R&D-intensive response to the biosimilar threat. As discussed in Section 1, this strategy involves creating a new, improved, and independently patentable version of an existing biologic.20 The strategic objective of a bio-better program is not merely to defend an existing franchise but to render the original product obsolete by the innovator’s own hand before biosimilars can erode its market share.

This “preemptive obsolescence” is a calculated gambit. The innovator invests in a full BLA development program for the bio-better, aiming to launch it several years before the original product’s loss of exclusivity. The commercial and medical affairs teams then work to switch the entire patient and prescriber base to the new, clinically superior product. By the time biosimilars for the original biologic launch, they find themselves competing against a reference product that the market already considers outdated. Payers may have already moved the bio-better to a preferred formulary position due to its superior clinical profile, making it difficult for a biosimilar of the “old” product to gain traction.25 This strategy transforms a defensive necessity into an offensive market-shaping maneuver, and it places the R&D organization at the center of corporate strategy.

5.3 If You Can’t Beat Them: The Rise of Innovator-Led Biosimilar Divisions

A growing number of major innovator biopharmaceutical companies have adopted a seemingly paradoxical strategy: they have established their own divisions to develop and market biosimilars that compete with the products of other innovators.60 This “if you can’t beat them, join them” approach serves as a powerful strategic hedge. It allows these companies to participate in the growing biosimilar market, leveraging their core competencies to capture revenue from off-patent biologics that they would otherwise lose out on entirely.

Amgen is a prime example of this dual strategy in action. While maintaining a robust pipeline of novel, first-in-class biologics, the company has also built one of the industry’s leading biosimilar businesses, with products like Amjevita (adalimumab biosimilar) and Wezlana (ustekinumab biosimilar).62 Amgen’s leadership has explicitly stated that their world-class expertise in manufacturing complex proteins is a key competitive advantage that they can deploy in the biosimilar space to ensure quality, reliability, and safety.51 Amgen’s CEO, Bob Bradway, has noted that patent expirations are a fact of life that spur innovation, and that the company’s biosimilar business is a way to capitalize on this cycle.51 The company projects its biosimilar sales to reach $4 billion by the end of the decade.62

This strategy, however, creates complex internal challenges for R&D portfolio management. It requires the organization to maintain two parallel and culturally distinct R&D pipelines: one focused on high-risk, breakthrough innovation, and another focused on the meticulous, process-driven work of reverse-engineering a competitor’s product and demonstrating similarity. Decisions on resource allocation, capital investment, and strategic priorities become significantly more complex when a company is simultaneously trying to innovate and imitate.

5.4 Case Studies in Competition: Lessons from the Humira and Remicade Battlegrounds

The theoretical strategies of competition become clearer when examined through the lens of real-world market battles. The experiences of two of the earliest and largest biologics to face biosimilar competition—Remicade (infliximab) and Humira (adalimumab)—offer crucial lessons.

Remicade (infliximab): The Challenge of Physician and Patient Confidence

Remicade was one of the first major monoclonal antibodies to face biosimilar competition in the U.S., with the launch of Inflectra in 2016.64 The Remicade case highlights the significant “soft” barriers to biosimilar uptake, even when strong clinical data exists. Numerous studies, including the pivotal NOR-SWITCH trial, demonstrated that switching from Remicade to an infliximab biosimilar was safe and did not lead to a loss of efficacy.39 Despite this, uptake was initially slow. Real-world data from some health systems showed high rates of patients discontinuing the biosimilar or switching back to the originator Remicade.66 This resistance was often not driven by clinical failure but by physician and patient hesitancy, concerns about non-medical switching, and perceived differences in patient support programs.66 This experience underscored that winning in the biosimilar market requires not just regulatory approval and a lower price, but also a concerted effort to build trust and confidence among prescribers and patients.

Humira (adalimumab): The Power of Patents and Payers

The battle for the Humira market in the U.S. is a masterclass in the power of intellectual property and payer dynamics. AbbVie, the manufacturer of Humira, successfully used a massive patent thicket of over 100 patents to delay the entry of U.S. biosimilars for years after the core patent expired, until 2023.42 When the market finally opened, it was flooded with nearly a dozen approved biosimilars.

Initially, their market penetration was minimal. As detailed in Section 3, this was primarily due to the “rebate wall,” where PBMs favored the high-rebate originator Humira on their formularies.36 Biosimilar manufacturers attempted to counter this with a dual-pricing strategy, launching both a high-list-price/high-rebate version and a low-list-price/low-rebate unbranded version to appeal to different parts of the market.42 However, the real breakthrough in market share came from the PBM co-promotion model pioneered by Caremark’s Cordavis and Sandoz’s Hyrimoz.42 By aligning the PBM’s financial interests with a specific biosimilar, this strategy was able to overcome the rebate wall and drive significant volume away from the originator. The Humira case demonstrates that in the modern U.S. market, biosimilar success is less a function of price alone and more a function of a sophisticated strategy that navigates both the patent courts and the opaque world of PBM contracting.

Section 6: The Future of Biologic Innovation: Projections, Challenges, and Strategic Recommendations

The biopharmaceutical industry is at a pivotal juncture. The initial waves of biosimilar competition have established a new market reality, and the coming decade will see this dynamic intensify as more than 55 blockbuster biologics, with collective peak sales exceeding $270 billion, are set to lose exclusivity by 2032.17 This impending “patent cliff” will continue to exert immense pressure on innovator R&D pipelines. Looking ahead, the industry must grapple with the application of the biosimilar paradigm to even more complex therapies, identify areas where competition may not materialize, and adopt clear strategies to foster sustainable innovation.

6.1 The Next Wave: Anticipating Competition for Cell and Gene Therapies

The next frontier for biosimilar-style competition will involve the most complex and personalized medicines developed to date: cell and gene therapies. The first of these advanced therapies are projected to face loss of exclusivity by the end of the decade, opening a new and challenging chapter in the biosimilar story.38

The hurdles to developing a “follow-on” version of a cell or gene therapy are orders of magnitude greater than for a monoclonal antibody. The “product is the process” principle is amplified to its extreme. For an autologous CAR-T cell therapy, for example, the manufacturing process involves extracting a patient’s own cells, genetically engineering them with a viral vector, expanding them, and re-infusing them into the same patient. Demonstrating that a competitor’s process—using a different viral vector, different cell culture media, and different expansion protocols—results in a product that is “highly similar” with “no clinically meaningful differences” will be a monumental scientific and regulatory challenge.

This complexity raises fundamental questions that will shape the future of R&D in this space:

- How will regulatory agencies like the FDA and EMA adapt their frameworks to assess similarity for living medicines?

- What will the “totality of the evidence” look like when the starting material is a variable human patient?

- Can the concept of interchangeability even apply to highly personalized therapies?

Innovator companies currently developing these next-generation therapies are likely to enjoy a very long period of de facto exclusivity, as the technical barriers to creating a follow-on product are immense. However, the long-term R&D strategy must anticipate that these barriers will eventually be overcome, necessitating a continued focus on next-generation platforms and process innovation as a key source of differentiation and defense.

6.2 The “Biosimilar Void”: Identifying Therapeutic Areas at Risk of Stagnation

While competition is intensifying for major blockbuster biologics, it is becoming clear that not all biologics will attract biosimilar development. This phenomenon is creating a “biosimilar void”—pockets of the market where competition may never materialize, leaving originator products with an extended, uncontested monopoly.38

Several factors contribute to the creation of a biosimilar void:

- Small Market Potential: The high cost of biosimilar development ($100 million to $300 million) requires a significant market opportunity to ensure a return on investment. Biologics for orphan diseases or with relatively low peak sales may not meet this threshold.17

- High Manufacturing Complexity: As innovators move towards more complex modalities, the technical difficulty and cost of replication may become prohibitive for all but the most sophisticated biosimilar developers.52

- Strong Patent Thickets: A formidable and dense web of secondary patents can make the prospect of litigation too costly and risky for a biosimilar developer to challenge.32

This dynamic has a paradoxical effect on innovator R&D strategy. The existence of the biosimilar void makes developing novel biologics for these niche areas more attractive. An R&D program targeting a rare disease with a complex biologic may promise a much longer period of uncontested revenue generation, improving its risk-adjusted NPV compared to a project in a highly competitive, blockbuster therapeutic area. This could strategically steer R&D investment away from areas of broad public health concern and towards more profitable, less competitive niche markets.

The table below provides a forward-looking snapshot of major biologics facing loss of exclusivity, illustrating the scale of the impending competitive wave and its strategic implications.

| Year of LOE | Reference Product | Originator Company | Key Therapeutic Area | Approx. 2024 Global Sales (USD Billions) | Known Biosimilars in Development | Strategic Implications for R&D | |

| 2025 | Perjeta (pertuzumab) | Roche/Genentech | Oncology (Breast Cancer) | $4.3 | Multiple | High pressure on Roche’s oncology pipeline to deliver next-generation therapies to offset revenue loss. | |

| 2025 | Benlysta (belimumab) | GSK | Immunology (Lupus) | $2.156 | Several | Increased focus on developing follow-on products or bio-betters for lupus to maintain franchise. | |

| 2026 | Kadcyla (ado-trastuzumab emtansine) | Roche/Genentech | Oncology (ADC) | $2.31 | Fewer (high complexity) | Highlights the strategic value of developing complex modalities (ADCs) that are harder to replicate, creating a higher barrier to biosimilar entry. | |

| 2028 | Keytruda (pembrolizumab) | Merck | Oncology (Immuno-Oncology) | >$25 | Numerous | Represents a massive impending patent cliff, driving intense R&D investment at Merck and competitors to develop the next generation of I-O therapies. | |

| 2028 | Opdivo (nivolumab) | Bristol Myers Squibb | Oncology (Immuno-Oncology) | >$9 | Numerous | Similar to Keytruda, forces a major strategic imperative to diversify the R&D pipeline beyond the current generation of checkpoint inhibitors. | |

| 2029 | Stelara (ustekinumab) | Johnson & Johnson | Immunology (Psoriasis, IBD) | >$10 | Numerous | A major test case for biosimilar uptake in immunology post-Humira, influencing future investment in this crowded therapeutic area. | |

| Data synthesized from sources: 6 |

6.3 Strategic Recommendations for R&D Leaders, Investors, and Policymakers

Navigating the complex and evolving biopharmaceutical landscape requires distinct and proactive strategies from all key stakeholders. The following recommendations are designed to help R&D leaders, investors, and policymakers foster a sustainable ecosystem that balances competition with innovation.

For R&D Leaders:

- Integrate Competitive Modeling into Early-Stage Decisions: The threat of biosimilar competition should be a core variable, not an afterthought, in all early-stage portfolio decisions. R&D leaders must demand robust models that project the timing and intensity of future competition to accurately assess the long-term value of a potential project.

- Invest in Platform Technologies as a Moat: Prioritize investment in proprietary manufacturing platforms, advanced formulation technologies, and novel delivery systems. These capabilities not only improve products but also create defensible intellectual property that raises the barrier to entry for competitors.

- Embrace a Bifurcated R&D Strategy: Recognize that the “innovation squeeze” is real. Formally structure the R&D portfolio to pursue both high-risk, first-in-class “moonshots” and strategic, lower-risk “bio-better” programs. The middle ground of incrementalism should be actively de-prioritized.

- Champion Digital Transformation: Aggressively adopt AI, in silico modeling, and advanced analytics as core R&D competencies. These are no longer just efficiency tools but are essential for accelerating timelines, reducing costs, and de-risking development in a hyper-competitive environment.

For Investors:

- Scrutinize Lifecycle and IP Strategy: When evaluating an innovator company, look beyond the clinical data of its lead asset. A deep analysis of the company’s LCM strategy, the strength and breadth of its patent estate, and its plans for a potential bio-better follow-on is critical to understanding its long-term durability.

- Assess Manufacturing and Technological Sophistication: A company’s capabilities in process development and manufacturing are a key indicator of its ability to defend its biologic franchises. Companies with unique and highly optimized processes have a significant competitive advantage.

- Discount the Value of “Me-Too” Assets: Be highly skeptical of the long-term value of “me-too” biologics in crowded therapeutic areas that are approaching major patent cliffs. The window of profitability for such assets is likely to be much shorter than historical benchmarks.

For Policymakers:

- Address the Patient Cost Paradox: The promise of biosimilars is incomplete if savings do not reach patients. Policymakers should investigate and implement reforms to insurance benefit design, such as caps on out-of-pocket costs for biologics or shared savings models, to ensure that competition improves affordability for the patients who need these medicines most.

- Promote Transparent, Value-Based Competition: Re-evaluate the impact of the opaque PBM rebate system on biosimilar uptake. Consider policies that encourage formulary placement based on the lowest net cost to the health system and patients, rather than the size of the rebate paid to intermediaries.

- Foster Global Regulatory Harmonization: Continue to work towards greater alignment of regulatory requirements between the FDA, EMA, and other major global agencies. Reducing the need for duplicative clinical studies, such as bridging studies, would lower development costs, accelerate the availability of new medicines, and improve patient access on a global scale.69

Works cited

- Comparing FDA and EMA Decisions for Market Authorization of Generic Drug Applications covering 2017–2020, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/media/156611/download

- Biological Product Definitions | FDA, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/files/drugs/published/Biological-Product-Definitions.pdf

- What Are “Biologics” Questions and Answers | FDA, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/about-fda/center-biologics-evaluation-and-research-cber/what-are-biologics-questions-and-answers

- What Are Biologics and How Are They Used in the Pharmaceutical Industry? – Oakwood Labs, accessed July 30, 2025, https://oakwoodlabs.com/what-are-biologics-and-how-are-they-used-in-the-pharmaceutical-industry/

- Biosimilars: Key regulatory considerations and similarity assessment tools – PMC, accessed July 30, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5698755/

- Biosimilar medicines: Overview | European Medicines Agency (EMA), accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/human-regulatory-overview/biosimilar-medicines-overview

- The Transformative Impact of Biosimilars on Biologic Drug Life Cycle …, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-impact-of-biosimilars-on-biologic-drug-life-cycle-management/

- Biologics vs. Small Molecule Drugs: Market Share and Growth Trends (Latest Data), accessed July 30, 2025, https://patentpc.com/blog/biologics-vs-small-molecule-drugs-market-share-and-growth-trends-latest-data

- What Are Biosimilars and How Do They Expand Treatment Options for Patients? – Pfizer, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.pfizer.com/news/articles/what_are_biosimilars_and_how_do_they_expand_treatment_options_for_patients

- An Overview of Biosimilar Regulatory Approvals by the EMA and …, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-biosimilar-landscape-an-overview-of-regulatory-approvals-by-the-ema-and-fda/

- Biologics Price Competition & Innovation Act (BPCIA): Litigation Considerations – Kilpatrick Townsend, accessed July 30, 2025, https://ktslaw.com/-/media/2022/Biologics-Price-Competition-And-Innovation-Act-BPCIA-Litigation-Considerations-w0344767.pdf

- Biological and biosimilar medicinal products – FAMHP, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.famhp.be/en/human_use/medicines/medicines/MA_procedures/types/Biosimilars

- Biosimilars in the EU – Information guide for healthcare professionals | EMA, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/leaflet/biosimilars-eu-information-guide-healthcare-professionals_en.pdf

- (PDF) Ten years of biosimilars in Europe: development and evolution of the regulatory pathways – ResearchGate, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/317052130_Ten_years_of_biosimilars_in_Europe_development_and_evolution_of_the_regulatory_pathways

- Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.dpc.senate.gov/healthreformbill/healthbill70.pdf

- Innovative Formulation Strategies for Biosimilars: Trends Focused on Buffer-Free Systems, Safety, Regulatory Alignment, and Intellectual Property Challenges – PMC – PubMed Central, accessed July 30, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12196224/

- Biosimilar Approval in Europe with Registration Pathways – Neuroquantology, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.neuroquantology.com/media/article_pdfs/121-129_faBPcvb.pdf

- Three imperatives for R&D in biosimilars – McKinsey, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/mckinsey/industries/life%20sciences/our%20insights/three%20imperatives%20for%20r%20and%20d%20in%20biosimilars/three-imperatives-for-r-and-d-in-biosimilars.pdf

- From Small Molecules to Biologics, New Modalities in Drug …, accessed July 30, 2025, https://chemaxon.com/blog/small-molecules-vs-biologics

- Will Biologics Surpass Small Molecules In The Pharmaceutical Race? – BiopharmaTrend, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.biopharmatrend.com/post/67-will-small-molecules-sustain-pharmaceutical-race-with-biologics/

- Biosimilar basics part 4: How are biobetters and biosimilars different? – Prime Therapeutics, accessed July 30, 2025, https://primetherapeutics.com/w/biosimilar-basics-part-4-how-are-biobetters-and-biosimilars-different

- www.bioagilytix.com, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.bioagilytix.com/blog/difference-between-biobetters-and-biosimilars/#:~:text=As%20the%20name%20suggests%2C%20biobetters,efficacy%2C%20and%20even%20reduce%20toxicity.

- primetherapeutics.com, accessed July 30, 2025, https://primetherapeutics.com/w/biosimilar-basics-part-4-how-are-biobetters-and-biosimilars-different#:~:text=Biobetters%20are%20new%20molecular%20entities,%2C%20efficacy%2C%20or%20manufacturing%20attributes.

- Biobetter Definition – BioPharmaSpec, accessed July 30, 2025, https://biopharmaspec.com/glossary/definition/biobetter/

- Biobetters, Supergenerics Hold Many Advantages for Pharma …, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/biobetters-supergenerics-hold-many-advantages-pharma-companies/

- What is Biobetter or Biosuperior? – DDReg, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.ddregpharma.com/what-is-biobetter-or-biosuperior

- Building better biobetters: From fundamentals to industrial application – PubMed, accessed July 30, 2025, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34461236/

- Three specialty drug trends to prepare for: Biosimilars, gene and cell therapies, cancer drugs – Evernorth Health Services, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.evernorth.com/articles/specialty-drug-pipeline-biosimilars-and-more

- “The Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act 10–A Stocktaking” by Yaniv Heled – Texas A&M Law Scholarship, accessed July 30, 2025, https://scholarship.law.tamu.edu/journal-of-property-law/vol7/iss1/3/

- Biosimilar Patent Dance: Leveraging PTAB Challenges for Strategic Advantage, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/biosimilar-patent-dance-leveraging-ptab-challenges-for-strategic-advantage/

- Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act of 2009 – Wikipedia, accessed July 30, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Biologics_Price_Competition_and_Innovation_Act_of_2009

- Biosimilar Cost Savings in the United States: Initial Experience and …, accessed July 30, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6075809/

- What role do IP rights play in biologics and biosimilars? – Patsnap Synapse, accessed July 30, 2025, https://synapse.patsnap.com/article/what-role-do-ip-rights-play-in-biologics-and-biosimilars

- Biosimilar Approvals Streamlined With Advanced Statistics Amidst Differing Regulatory Requirements, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.centerforbiosimilars.com/view/biosimilar-approvals-streamlined-with-advanced-statistics-amidst-differing-regulatory-requirements

- The Economics of Biosimilars – Number Analytics, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.numberanalytics.com/blog/economics-biosimilars-cost-savings-market-dynamics

- Decoding the biosimilar paradox: Policy reforms, increased transparency and patient education – Medical Economics, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.medicaleconomics.com/view/decoding-the-biosimilar-paradox-policy-reforms-increased-transparency-and-patient-education

- Sustaining competition for biosimilars on the pharmacy benefit: Use …, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.jmcp.org/doi/10.18553/jmcp.2024.30.6.600

- Biosimilar Uptake Has Been Slow but This is Changing – Managed Healthcare Executive, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.managedhealthcareexecutive.com/view/biosimilar-uptake-has-been-slow-but-this-is-changing

- Biosimilar medicines: the intersection of access, affordability, and innovation, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.europeanpharmaceuticalreview.com/article/245839/biosimilar-medicines-the-intersection-of-access-affordability-and-innovation/

- Process and Clinical Outcomes of a Biosimilar Adoption Program with Infliximab-Dyyb, accessed July 30, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10390955/

- PBMs Support Patient Access to Biosimilars and Reference Biologics | PCMA, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.pcmanet.org/pbms-support-patient-access-to-biosimilars-and-reference-biologics/

- Report Highlights Biosimilars Savings, but High Out-of-Pocket Costs for Patients, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.ajmc.com/view/report-highlights-biosimilars-savings-but-high-out-of-pocket-costs-for-patients

- Biosimilar and Innovator Co-Promotions: The Changing Tide of …, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.iqvia.com/locations/united-states/blogs/2024/09/biosimilar-and-innovator-co-promotions

- Biosimilars May Save Money. But Have They Lowered Out-of-Pockets?, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.managedhealthcareexecutive.com/view/so-far-biosimilars-have-lowered-out-of-pockets-study-finds

- Study: Biosimilar Competition Did Not Consistently Lower Costs for Patients, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.pharmacytimes.com/view/study-biosimilar-competition-did-not-consistently-lower-costs-for-patients

- Patient Out-of-Pocket Costs for Biologic Drugs After Biosimilar …, accessed July 30, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10980968/

- Biosimilar Competition May Fail to Lower Out-of-Pocket Costs for Patients, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.hmpgloballearningnetwork.com/site/frmc/news/biosimilar-competition-may-fail-lower-out-pocket-costs-patients

- Provider and Patient Knowledge Gaps on Biosimilars: Insights From …, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.ajmc.com/view/biosimilarssuppl-insightssurveys

- The Patient Perspective on Biosimilars – Alliance for Health Policy, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.allhealthpolicy.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/hydeslides-AHP-biosimilarsbriefing-2282019-final.pdf

- IRA: How Pharma Executives Are Responding – AlphaSense, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.alpha-sense.com/blog/trends/inflation-reduction-act-executive-response/

- Roche Strategies to Tackle Biosimilar Issue – Cases and Tools in …, accessed July 30, 2025, https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/bio16610w18/chapter/roche-strategies-to-tackle-biosimilar-issue-2/

- At Amgen, It’s “Innovate or Die” Says Amgen CEO Bob Bradway in Interview with Morgan Stanley, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.amgen.com/stories/2023/01/innovate-or-die-says-bob-bradway-in-interview-with-morgan-stanley

- Assessing the Biosimilar Void in the U.S. – IQVIA, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.iqvia.com/insights/the-iqvia-institute/reports-and-publications/reports/assessing-the-biosimilar-void-in-the-us

- 7 CEOs Say It’s About The “Bios” Biotechs Biopharmaceuticals and Biosimilars – Outsourced Pharma, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.outsourcedpharma.com/doc/ceos-say-it-s-about-the-bios-biotechs-biopharmaceuticals-and-biosimilars-0001

- Exploring Biosimilars as a Drug Patent Strategy: Navigating the …, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/exploring-biosimilars-as-a-drug-patent-strategy-navigating-the-complexities-of-biologic-innovation-and-market-access/

- Exploring Biosimilars as a Drug Patent Strategy – DrugPatentWatch, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/exploring-biosimilars-as-a-drug-patent-strategy/

- Life Cycle Management Strategy | SAI MedPartners, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.sai-med.com/life-cycle-management/

- What role does AI play in biosimilar drug development? – Patsnap Synapse, accessed July 30, 2025, https://synapse.patsnap.com/article/what-role-does-ai-play-in-biosimilar-drug-development

- Pharmaceutical Product Lifecycle Management | ISPE, accessed July 30, 2025, https://ispe.org/topics/lifecycle-management

- Quality Assurance in R&D for Biosimilars – Precision For Medicine, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.precisionformedicine.com/blog/quality-assurance-in-rd-for-biosimilars/

- The biosimilar pathway in the USA: An analysis of the innovator …, accessed July 30, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9307033/

- BIOBETTERS…. What’s in Your Vocabulary? – Anton Health, accessed July 30, 2025, https://antonhealth.com/biobetters-whats-in-your-vocabulary/

- With patent losses on the horizon, Amgen refocuses its business strategy – PharmaVoice, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.pharmavoice.com/news/amgen-patent-loss-business-strategy-otezla-enbrel-biosimilars/741572/

- Amgen CEO Bob Bradway’s 2024 Letter to Shareholders, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.amgen.com/stories/2025/04/2024-letter-to-shareholders

- Litigation Spotlight: The Infliximab (Remicade®) Litigation – Biosimilars Law Bulletin, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.biosimilarsip.com/2017/04/19/litigation-spotlight-infliximab-remicade-litigation/

- A randomised, double-blind, phase III study comparing SB2, an infliximab biosimilar, to the infliximab reference product Remicade in patients with moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis despite methotrexate therapy | Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, accessed July 30, 2025, https://ard.bmj.com/content/76/1/58