Introduction: Beyond the Pill, Beyond the Price Tag

In modern healthcare, the hospital formulary stands as a critical gateway to market access. It is far more than a simple inventory list; it is a dynamic, strategic instrument meticulously designed to manage costs, ensure patient safety, and optimize clinical outcomes.1 For generic drug manufacturers, navigating this complex landscape has traditionally been a game of price. The lowest bidder often wins the volume. Yet, this paradigm is rapidly evolving. As healthcare systems grapple with unprecedented financial pressures, mounting regulatory complexity, and the persistent threat of drug shortages, the criteria for formulary acceptance have expanded dramatically. A low acquisition cost is no longer a guaranteed ticket to inclusion; it is merely the price of admission.

The true challenge—and the greatest opportunity—lies in crafting a value proposition that transcends the price tag. The formulary system has matured from a logistical tool developed in the 1950s to ensure a consistent supply of medications into a sophisticated process of medication use management. This system, governed by the powerful Pharmacy & Therapeutics (P&T) Committee, encompasses an ongoing, methodical evaluation of medications, the establishment of guidelines for optimal use, and the development of policies for everything from prescribing to administration.2 The overarching goal is to curate a list of the safest, most effective medications that achieve desired therapeutic goals at the most reasonable cost to the entire healthcare system.

The stakes for mastering this environment are astronomical. Generic drugs are the bedrock of the American healthcare system, accounting for a remarkable 90% of all prescriptions filled, yet they represent only about 17.5% of the nation’s total spending on prescription drugs.4 This incredible efficiency generated a record $408 billion in savings for the U.S. healthcare system in 2022 alone, contributing to a cumulative $2.9 trillion in savings over the past decade.4 For a generic manufacturer, securing a place on a major hospital system’s formulary is not just a sale; it is an entry point into a massive volume channel that can define a product’s success.

However, this success is contingent on a new level of strategic sophistication. The shift from a simple list to a comprehensive management system demands a parallel shift in the manufacturer’s approach. The value story can no longer be a one-dimensional narrative about being cheaper than the brand. It must be a multi-faceted argument demonstrating how the generic product aligns with the hospital’s system-wide goals of safety, operational efficiency, risk mitigation, and predictable, high-quality patient care. This report serves as a definitive playbook for the modern generic drug manufacturer. It deconstructs the formulary decision-making process, illuminates the explicit and implicit criteria used by P&T committees, and provides a clear, actionable framework for building a winning strategy. This is the guide to moving beyond price and positioning your generic drug not just as an alternative, but as an indispensable asset to the hospital.

Understanding the Battlefield: Types of Hospital Formularies and Their Strategic Implications

Before a strategy can be deployed, the terrain must be understood. Hospital formularies are not monolithic; they are designed with different structures, each with unique mechanisms for controlling costs and guiding clinical practice. For a generic manufacturer, recognizing the type of formulary a target institution employs is the first step in tailoring a compelling value proposition. The structure of the formulary dictates the P&T committee’s priorities, the competitive landscape, and the most effective levers to pull for gaining access. The four primary models are Open, Closed, Tiered, and the emerging Value-Based formulary.1

An Open Formulary is the most permissive model, providing coverage for nearly all available drug products.3 While some drug classes, such as those for cosmetic use or over-the-counter products, may be excluded, physicians are generally free to prescribe both formulary and non-formulary agents. This model offers the highest level of product access for patients and the greatest autonomy for prescribers, but it comes at a significant cost. For both the payer and the patient, open formularies are the most expensive option, offering the least control over utilization and spending.1 From a strategic standpoint, while entry onto an open formulary is less challenging, achieving significant market share requires traditional marketing and physician education efforts, as the system itself provides little incentive to choose one product over another.

At the opposite end of the spectrum is the Closed Formulary. This is the most restrictive and, for the payer, the most powerful cost-containment tool.2 In this model, non-formulary drugs are not reimbursed, and the P&T committee curates a limited list of approved agents, often granting sole-source status to one or two products within a therapeutic class in exchange for deep price concessions.3 While this model severely limits prescriber choice and patient access, it is not entirely inflexible. All closed formulary systems include a “formulary exception” policy, which allows physicians to request coverage for a non-formulary drug when it is deemed medically necessary, though this process can be administratively burdensome.3 For a generic manufacturer, the closed formulary represents a high-risk, high-reward scenario. The challenge is immense, as the competition is a zero-sum game for a single coveted spot. However, winning that spot guarantees significant, predictable volume.

The most common structure in the current landscape is the Tiered Formulary. This model seeks a balance between cost control and choice by categorizing drugs into different “tiers,” each with a corresponding level of patient cost-sharing (e.g., copayment or coinsurance).3 A typical design might include three to five tiers:

- Tier 1: Preferred Generics (lowest patient cost-sharing)

- Tier 2: Non-Preferred Generics / Preferred Brands (moderate cost-sharing)

- Tier 3: Non-Preferred Brands (higher cost-sharing)

- Tier 4/5: Specialty Drugs (highest cost-sharing, often a percentage coinsurance) 1

The mechanism is simple but effective: it uses financial incentives to steer patients and prescribers toward the most cost-effective options. For generic drugs, placement on Tier 1 is the primary objective. This structure institutionalizes the concept of therapeutic interchange, moving beyond simple brand-to-generic substitution. The competitive battle is not just against the original brand but against other generics and even other branded drugs within the same therapeutic class for that preferential tier placement.

Finally, the Value-Based Formulary represents the next evolution in formulary management. Rather than focusing solely on the upfront net cost of a medication, this model assesses a product’s value primarily through cost-effectiveness analysis.1 Drugs that demonstrate a high long-term value—by improving clinical outcomes, enhancing quality of life, or reducing the utilization of other expensive healthcare resources (like hospitalizations)—are assigned to lower patient cost-sharing tiers, even if their initial price is high. This sophisticated approach shifts the focus from short-term drug spend to long-term, total cost of care. While this model is more complex to implement, it presents a unique opportunity for a generic manufacturer that can provide pharmacoeconomic data demonstrating that its product leads to better patient adherence or fewer side effects compared to a competitor, thereby generating downstream savings for the health system.

The movement away from open formularies toward more restrictive tiered and closed models is a clear signal that hospitals are embracing active management of drug utilization. These systems are designed to guide, incentivize, and, in some cases, mandate prescriber choices. This fundamentally changes the competitive landscape. The battle is no longer a simple binary contest between a brand and its generic copy. It is a multi-dimensional competition where a generic must prove it is the superior interchangeable option within its entire therapeutic class. This requires a strategy built on comparative data that demonstrates not just equivalence to the brand, but superiority in value—whether clinical, economic, or operational—against all relevant alternatives.

| Formulary Structure | Core Mechanism | P&T Committee’s Primary Goal | Key Challenge for Generic | Winning Strategy for Generic |

| Open Formulary | Minimal restrictions on access. | Ensure broad availability of therapies. | Gaining market share in a crowded field with no systemic incentives. | Focus on physician education, brand recognition (if applicable), and demonstrating superior supplier services. |

| Closed Formulary | Exclusion of non-formulary products. | Maximize cost savings through aggressive price negotiations and limited choice. | Winning an exclusive or semi-exclusive contract against all competitors. | Offer the lowest net price combined with a robust Budget Impact Analysis (BIA) and a strong supply chain guarantee. |

| Tiered Formulary | Financial incentives (patient cost-sharing) to guide choice. | Steer utilization toward the most cost-effective options while maintaining choice. | Securing preferential Tier 1 placement against other generics and preferred brands. | Demonstrate clear cost-minimization and provide evidence of operational value (e.g., safety, packaging) to justify preferred status. |

| Value-Based Formulary | Cost-sharing based on long-term cost-effectiveness. | Optimize total cost of care and long-term patient outcomes. | Providing evidence of value beyond acquisition cost. | Develop pharmacoeconomic models showing improved adherence, reduced side effects, or other downstream cost offsets. |

The Gatekeepers: Deconstructing the Pharmacy & Therapeutics (P&T) Committee

Anatomy of the P&T Committee: Who They Are and What They Do

At the heart of every formulary decision sits the Pharmacy & Therapeutics (P&T) Committee. This body is the formal organizational link between the pharmacy department and the medical staff, charged with overseeing all aspects of medication use within the institution.11 To successfully position a generic drug, one must first understand the mission, composition, and function of this critical group. The P&T committee is not merely a purchasing department; it is a clinical governance body whose primary mission is to establish and enforce policies that ensure the effective, safe, and cost-effective use of all medications.13 Its core objectives are threefold: to specify the drugs of choice and their alternatives based on rigorous evidence of safety and efficacy; to minimize therapeutic redundancies within the formulary; and to maximize the overall cost-effectiveness of pharmacotherapy for the institution.

The power of the P&T committee stems from its multidisciplinary composition. It is intentionally designed as a committee of peers, a coalition of experts representing the key stakeholders in the medication use process. The core of the committee is typically comprised of actively practicing physicians from various specialties, both primary care and sub-specialties, and experienced pharmacists, particularly those with expertise in drug information and clinical practice.3 However, a well-structured modern P&T committee extends far beyond this clinical core. It often includes senior nursing leaders, hospital administrators, quality assurance representatives, and, increasingly, specialists in health economics and outcomes research (HEOR) or pharmacoeconomics.14 Some forward-thinking institutions even include patient representatives or medical ethicists to provide a broader perspective on the impact of formulary decisions.14 This diverse makeup is its greatest strength, ensuring that decisions are viewed through multiple lenses—clinical efficacy, patient safety, operational feasibility, and financial impact.

The functions of the P&T committee are comprehensive. Its most visible role is to develop, manage, and continually update the hospital’s drug formulary. To keep the formulary current in the face of a continuous stream of new drug approvals, the committee meets regularly, often on a quarterly basis, to review new medications and therapeutic classes.3 This review is a methodical, evidence-based process. The committee evaluates a wide range of information, including peer-reviewed clinical trials, national treatment guidelines, comparative effectiveness reports, and post-marketing safety data from the FDA.3

Beyond simply adding or removing drugs from the list, the P&T committee designs and implements the policies that govern medication use. This includes developing crucial utilization management strategies such as:

- Prior Authorization: Requiring prescribers to obtain pre-approval for certain high-cost or high-risk medications.

- Step Therapy: Mandating that a proven, cost-effective first-line agent (often a generic) be tried before a newer, more expensive alternative is approved.

- Quantity Limits: Restricting the amount of a medication that can be dispensed at one time to ensure appropriate use and prevent waste.

The committee also develops clinical care plans, treatment guidelines, and critical pathways to standardize care and promote the adoption of best practices throughout the institution. In essence, the P&T committee acts as the central nervous system for medication management, making decisions that ripple through every department of the hospital.

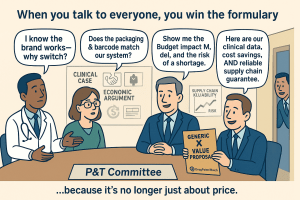

A critical strategic error is to view this committee as a single, monolithic entity. It is a coalition of individuals, each with a distinct professional background, a unique set of priorities, and different metrics for success. The infectious disease physician is primarily concerned with antimicrobial stewardship and clinical cure rates. The chief nursing officer is focused on medication administration safety and workflow efficiency. The hospital administrator is accountable for adhering to the pharmacy budget and managing financial risk. A formulary decision, therefore, is not a simple up-or-down vote on a drug’s merits; it is a complex negotiation among these internal, and sometimes competing, priorities. A generic drug that is clinically equivalent and economically attractive might still face resistance if its packaging is confusing for nurses or if its supply chain is perceived as unreliable by the pharmacy director.

This reality dictates the strategy for engagement. A winning formulary submission cannot be a one-size-fits-all document. It must be a modular, multi-faceted presentation that speaks directly to the specific concerns of each key stakeholder on the committee. It must provide the rigorous clinical data for the physicians, the detailed budget impact model for the administrator, and the comprehensive operational information—on packaging, labeling, and supply chain reliability—for the pharmacists and nurses. The goal is not just to persuade the committee as a whole, but to build a coalition of support within it by providing each member with the specific, tailored evidence they need to confidently advocate for the product among their peers.

The Human Element: Debunking Myths and Understanding Decision-Making Biases

While the P&T committee process is designed to be a rational, evidence-based endeavor, it is ultimately executed by human beings. To ignore the influence of professional culture, cognitive biases, and long-held beliefs is to misunderstand how decisions are truly made. A survey conducted by the Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP) revealed several pervasive “myths” that frequently surface during P&T committee deliberations, often swaying decisions despite a lack of supporting evidence. For a generic manufacturer, understanding these undercurrents is crucial for framing a persuasive argument that not only presents the facts but also navigates the complex human dynamics of the committee room.

One of the most common and influential myths is the notion that “the specialist knows best”. In the ISMP survey, 74% of respondents reported encountering comments from sub-specialists suggesting that it was presumptuous for a generalist committee to make formulary decisions about complex specialty drugs. These comments were reported to influence the final decision in a majority of cases. This belief stems from a deep-seated respect for specialized expertise, but it can lead to a deference that bypasses the committee’s critical evaluation process. The reality is that while specialists provide essential input, an interdisciplinary review by pharmacists, nurses, and general physicians is vital for identifying broader safety and operational issues that a specialist, focused solely on efficacy, might overlook.

Another powerful bias is rooted in “causal empiricism,” or the tendency to overvalue personal anecdotal experience. A staggering 75% of survey respondents had heard physicians argue for a drug’s inclusion based on their own favorable clinical experiences, often requesting a “trial period” for the medical staff to “evaluate” the drug themselves. In 70% of these instances, such anecdotal appeals affected the formulary decision. While personal experience is valuable, it is susceptible to confirmation bias and lacks the scientific rigor of randomized, blinded, controlled trials, which remain the gold standard for proving a medication’s true efficacy and safety.

The myth that “widespread use equals the drug of choice” also holds significant sway. The argument that a drug should be added to the formulary simply because it is popular, in high demand by patients, or used by competing hospitals was encountered by 72% of respondents. This line of reasoning conflates market success with clinical superiority. In reality, a drug’s popularity may be a greater testament to the manufacturer’s marketing budget and strategy than to its comparative benefits, especially given the history of rapidly accepted new drugs that were later found to be harmful.

Finally, the deeply ingrained belief that “the formulary interferes with clinical freedom” represents a significant cultural hurdle. This perception frames the formulary not as a tool for quality improvement and patient safety, but as an administrative constraint on a physician’s professional autonomy. The reality is that an effective formulary system is not designed to interfere with prescribing but to provide broad therapeutic guidance, developed by a group of peers and experts, that is generally superior to any single clinician’s personal, more limited formulary.

These myths are not simply logical fallacies to be dismissed with a barrage of data. They are expressions of deeply held professional values: the primacy of expertise, the trust in one’s own clinical judgment, and the fierce protection of professional autonomy. A generic manufacturer that fails to recognize this will find its data falling on deaf ears. A strategy that directly confronts and dismisses a physician’s personal experience as “statistically insignificant” is likely to be met with resistance, as it can be perceived as an attack on their professional identity.

The more sophisticated approach is to frame the evidence in a way that respects these values while gently guiding the conclusion. For example, when countering causal empiricism, the message should not be, “Your experience is wrong.” Instead, it should be, “Your excellent results with the brand-name drug are exactly what the evidence would predict, as it is a highly effective therapy. Our generic has been rigorously proven to be identical at the molecular and biological level. The data from these large-scale clinical trials serve to confirm that the positive outcomes you’ve seen in your own patients can be reliably and consistently replicated across the entire patient population of this hospital, all while allowing the institution to be a better steward of its resources.” This reframes the data not as a contradiction of personal experience, but as a validation and an empowerment tool. It positions the generic drug as a vehicle that enables the physician to apply their expert judgment more broadly and cost-effectively, aligning the manufacturer’s goals with the clinician’s sense of professional pride and purpose.

The Keys to the Kingdom: Mastering the Three Pillars of Formulary Acceptance

Securing a coveted spot on a hospital formulary is not a matter of chance; it is the result of a meticulously constructed argument built upon three foundational pillars: an irrefutable clinical case, a compelling economic argument, and a differentiated operational value proposition. For a generic drug, where the active molecule is, by definition, not novel, mastery of these three domains is paramount. The P&T committee must be convinced not only that the generic is a perfect substitute for the brand but also that its adoption is a financially sound and operationally seamless decision for the institution. Excelling in just one or two of these areas is insufficient; a winning strategy requires a comprehensive and integrated presentation that addresses every potential question and concern from the committee’s diverse membership.

Pillar 1: The Clinical Case – Proving Sameness and Safety

The absolute, non-negotiable foundation of any generic drug’s formulary submission is the clinical case. Before any discussion of cost savings or supply chain efficiencies can begin, the P&T committee must be unequivocally convinced that the generic product is a safe and effective substitute for its brand-name counterpart. This requires more than simply stating regulatory approval; it demands a proactive effort to address the nuanced clinical concerns and anxieties that often accompany a switch from a known entity to a new one.

The FDA Standard: Bioequivalence and Therapeutic Equivalence

The starting point for the clinical case is the rigorous standard set by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). A generic drug can only be approved via an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) if it is proven to be the same as the brand-name medicine in several key aspects: dosage form, strength, route of administration, quality, performance characteristics, and intended use. The manufacturer must also demonstrate that its facilities meet the same strict standards of Current Good Manufacturing Practices (cGMP) as the brand manufacturer.21

The scientific cornerstone of this approval is the concept of bioequivalence. Manufacturers must conduct studies, typically in a small cohort of healthy volunteers, to demonstrate that their generic version releases its active ingredient into the bloodstream at virtually the same speed and in virtually the same amounts as the original drug. The statistical criteria for this are precise: the 90% confidence interval for the ratio of the generic’s key pharmacokinetic measures—specifically, the area under the curve (AUC, representing total drug exposure) and the maximum concentration (Cmax, representing the rate of absorption)—to the brand’s measures must fall entirely within the limits of 80% to 125%.

This 80-125% range is a frequent source of misunderstanding and a key point for a generic manufacturer to clarify in its formulary submission. It does not mean that the generic drug’s potency can vary by up to 25%. Rather, it is a statistical boundary used to ensure a very high degree of similarity. In practice, the actual measured difference in absorption between generic and brand-name drugs in these studies is remarkably small, with one analysis of FDA data showing an average difference of approximately 3.5%. This level of variation is comparable to what is observed between different batches of the same brand-name drug. A generic drug that meets these stringent bioequivalence standards is considered by the FDA to be therapeutically equivalent, meaning it can be expected to have the same clinical effect and safety profile when administered to patients under the conditions specified in the labeling.

Addressing the “Switch” Anxiety: Overcoming Clinical Inertia and the Nocebo Effect

While FDA approval provides the scientific foundation, it does not automatically quell the clinical anxieties of a P&T committee. Clinicians are inherently risk-averse; their guiding principle is “first, do no harm.” The brand-name drug is a known quantity, a therapy with which they have years of experience. The generic, however similar, represents a change, and any change introduces a perceived risk. This “clinical inertia” is a powerful force that the generic manufacturer must actively work to overcome.

This anxiety is often magnified by several factors. First is the issue of inactive ingredients, or excipients. While the active ingredient in a generic must be identical to the brand, the excipients—the fillers, binders, and dyes that make up the bulk of the pill—can differ.21 Although these ingredients must be proven to be safe and have no effect on the drug’s function, clinicians may harbor concerns about the potential for allergic reactions or different tolerability profiles in sensitive patients.

Second, the physical appearance of the generic drug often must, by trademark law, differ from the brand in color, shape, or size. This change can be a significant source of confusion and anxiety for patients, particularly the elderly or those on multiple medications. This confusion can lead to decreased medication adherence or, in some cases, a “nocebo effect,” where a patient’s negative expectation about the new medication leads to the perception of adverse effects or reduced efficacy, even when none biologically exist.

These concerns are most acute for drugs with a narrow therapeutic index (NTI), such as certain antiepileptics, anticoagulants, or thyroid medications. For these drugs, small variations in blood concentration can have significant clinical consequences, leading to either toxicity or loss of efficacy. P&T committees are justifiably cautious when considering generic substitution for NTI drugs, and several studies have documented instances of poorer clinical outcomes or increased adverse events following a switch, particularly in epilepsy treatment.

The burden of proof, therefore, lies squarely with the generic manufacturer to eliminate every shred of clinical doubt. The clinical section of the formulary dossier must go far beyond a simple declaration of bioequivalence. It must be a comprehensive package designed to de-risk the decision for the committee. A best-in-class clinical submission should include:

- A Reaffirmation of the Molecule’s Value: Begin by summarizing the pivotal clinical trials for the original brand-name drug. This reinforces the established efficacy and safety of the active ingredient itself, setting a positive tone.

- A Transparent Breakdown of Bioequivalence Data: Present the bioequivalence study results clearly, but do not stop at the 80-125% range. Proactively include the data on the average measured difference (e.g., 3.5%) to provide crucial context and counter potential misconceptions about wide variability.

- A Proactive Excipient Profile: Provide a complete list of all inactive ingredients used in the formulation. For each excipient, include a statement on its safety profile and its common use in other widely prescribed, FDA-approved medications. This preempts questions and demonstrates transparency.

- Real-World Evidence (RWE): If the generic product is already marketed in other countries, any available post-marketing surveillance data or real-world evidence of its safety and effectiveness is invaluable. This data transforms the clinical argument from “our drug is theoretically the same” to “our drug has been proven to perform the same in thousands of real-world patients.”

By taking these extra steps, the manufacturer moves from simply meeting the regulatory standard to actively building clinical confidence. The goal is to make the P&T committee feel that choosing the generic is not just a financially prudent decision, but a clinically indistinguishable one.

Pillar 2: The Economic Argument – From Cost-Minimization to Budget Impact

Once the clinical case for equivalence has been firmly established, the focus of the P&T committee shifts to the economic implications of a formulary addition. For a generic drug, this is its home turf—the domain where its primary value proposition resides. However, simply stating a lower price is not enough. A sophisticated economic argument requires a formal, structured analysis that quantifies the financial benefits for the institution in a clear, defensible, and transparent manner. This involves understanding the principles of pharmacoeconomics and, most importantly, mastering the art of the Budget Impact Analysis (BIA).

Pharmacoeconomics for Generics: The Primacy of Cost-Minimization Analysis (CMA)

Pharmacoeconomics is the branch of health economics that identifies, measures, and compares the costs and consequences of pharmaceutical products and services. It is a core component of the broader field of Health Economics and Outcomes Research (HEOR), which has become indispensable for demonstrating value in an increasingly cost-constrained healthcare environment. There are several types of pharmacoeconomic analyses, including cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA), cost-utility analysis (CUA), and cost-benefit analysis (CBA), each designed to compare interventions with different outcomes.

However, for a generic drug that has successfully proven its therapeutic equivalence to the brand-name originator, the most appropriate and powerful form of analysis is Cost-Minimization Analysis (CMA). The logic of CMA is straightforward: when two or more interventions have been demonstrated to produce equivalent clinical outcomes, the decision of which to use can be based solely on a comparison of their costs.3 The intervention with the lowest total cost is the preferred option. This is the fundamental economic principle that underpins the entire generic drug market. The successful clinical case from Pillar 1 is the prerequisite that allows the manufacturer to frame the entire economic discussion as a CMA, simplifying the decision for the P&T committee by isolating the variable of cost.

The Budget Impact Analysis (BIA): Your Most Powerful Financial Tool

While CMA provides the theoretical framework, the Budget Impact Analysis (BIA) is the practical tool that translates this framework into a concrete financial forecast for the hospital. A BIA is not the same as a cost-effectiveness analysis; it does not measure value in terms of health outcomes per dollar spent. Instead, its purpose is purely financial: to estimate the consequences of adopting a new health intervention on the healthcare budget, given resource and budget constraints.28 It answers the hospital administrator’s most pressing question: “If we add this drug to our formulary, what will be the net effect on our bottom line over the next one to five years?”.

A well-constructed BIA is a mandatory component of a modern formulary submission and is required by many health technology assessment (HTA) agencies and payers worldwide. According to guidelines from organizations like the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR), a credible BIA must include several key elements:

- Model Structure: A clear and transparent model, often built in spreadsheet software, that calculates costs with and without the new drug in the treatment mix.

- Population Size: An estimate of the number of patients within the hospital’s population who are currently being treated for the relevant condition and would be eligible for the new generic.

- Time Horizon: A defined period for the analysis, typically reflecting the hospital’s budget cycle (e.g., 1, 3, or 5 years).

- Treatment Mix: The current market share of the brand-name drug and other relevant comparators, and a realistic, evidence-based projection of the market share the new generic is expected to capture over the time horizon.

- Treatment Costs: The acquisition costs of the generic, the brand, and any other relevant drugs.

- Disease-Related Cost Offsets: Any changes in other healthcare costs that may result from the introduction of the new drug.

For a generic manufacturer, a basic BIA is relatively simple: it models the displacement of the higher-priced brand with the lower-priced generic and calculates the direct drug cost savings. However, a truly exceptional BIA—one that captures the attention of the P&T committee and differentiates the product from its competitors—goes a step further. It demonstrates a deep understanding of the hospital’s total cost of care by incorporating relevant downstream cost offsets.

A hospital’s budget is affected by more than just the acquisition price of a drug. It is also impacted by labor costs, diagnostic testing, and waste. A sophisticated BIA will build in modules to account for these factors. For example:

- Does the brand-name drug require frequent and costly laboratory monitoring that the generic does not? This saving should be quantified in the BIA.

- Is the brand-name drug supplied in a multi-dose vial that leads to waste, while the generic is available in more efficient unit-dose packaging? The cost of that waste should be calculated and presented as a saving.

- Does the generic come in a ready-to-administer formulation that saves valuable nursing or pharmacy technician time compared to a brand that requires complex reconstitution? This labor saving, translated into dollars based on average hospital wages, is a powerful addition to the value proposition.

By incorporating these cost offsets, the generic manufacturer transforms its BIA from a simple price comparison into a comprehensive operational value analysis. It sends a clear message to the P&T committee: “We understand your business. We have thought beyond the pill and have considered the total impact of our product on your institution’s resources.” This provides the hospital administrator and pharmacy director on the committee with a much more robust and defensible justification for making the switch. It elevates the economic argument from a simple claim of being “cheaper” to a proven case of being “more efficient” for the entire system.

Pillar 3: The Operational Value Proposition – Differentiating Beyond the Molecule

In the hyper-competitive generic drug market, it is inevitable that a P&T committee will find itself evaluating multiple generic versions of the same brand-name drug, all with equivalent clinical data and similarly aggressive pricing. In this scenario, when the first two pillars—the clinical case and the economic argument—result in a tie, the decision will hinge on the third pillar: the operational value proposition. These are the “tie-breaker” factors, the tangible and intangible attributes of the product and its manufacturer that impact the hospital’s day-to-day operations, safety protocols, and risk management. As one set of guidelines notes, when two medications produce similar effectiveness and safety, “business elements like cost, supplier services, ease of delivery or other unique properties of the agents are considered”. For the savvy generic manufacturer, this is where true, sustainable differentiation can be built.

Supply Chain Reliability: The New Quality Metric

Perhaps the most significant and rapidly emerging differentiator in hospital pharmacy is supply chain reliability. In recent years, drug shortages have escalated from a sporadic nuisance to a chronic and critical public health crisis. For hospitals, shortages are a nightmare, compromising patient care, forcing the use of less effective or more expensive therapeutic alternatives, and consuming an enormous amount of pharmacy and clinical staff time to manage.31 The financial impact is staggering; one survey estimated that shortages increase pharmaceutical acquisition costs in the U.S. by over $99 million annually, not including the immense labor costs involved in managing them.

The root cause of this crisis is often not a lack of raw materials, but a fundamental market failure. The relentless pressure from purchasers to secure the absolute lowest price has created a powerful disincentive for manufacturers to make necessary investments in robust quality management systems and redundant supply chains.33 The leading cause of drug shortages is, in fact, low levels of quality management maturity in manufacturing facilities. The market has historically rewarded the lowest price, inadvertently penalizing the investments in quality that prevent shortages.

This creates a profound strategic opportunity. A generic manufacturer can choose to break this cycle by making supply chain reliability a core part of its value proposition. Instead of just selling a pill, it can sell certainty. This requires a tangible investment in quality: dual-sourcing of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), maintaining higher-than-average safety stock levels, investing in state-of-the-art manufacturing facilities with impeccable regulatory track records, and developing a transparent system for communicating supply status to customers.

This investment is then translated into a powerful message for the P&T committee, particularly for the pharmacy director who lives with the daily pain of managing shortages. The proposition becomes: “Our price is competitive, but our true value lies in our guaranteed reliability. We can provide you with our manufacturing quality audit scores, our supply chain redundancy map, and we are willing to include a service-level guarantee in our contract. Choosing our product de-risks your pharmacy from the immense clinical and financial costs of a potential shortage.” This argument directly addresses a major, often unquantified, risk for the hospital. It reframes the purchasing decision from a simple cost calculation to a strategic risk management choice, turning a systemic market weakness into a unique and highly valuable competitive advantage.

Manufacturer Reputation and Value-Added Services

In a commoditized market, reputation matters. P&T committees are more likely to trust a manufacturer with a long track record of quality, reliability, and responsive customer service. Studies have shown that larger, more established manufacturers are more likely to provide high-quality, comprehensive formulary dossiers in response to requests, signaling a higher level of professionalism and commitment.

Beyond a solid reputation, manufacturers can differentiate themselves by offering value-added services that support the hospital’s goals. While more common for specialty or branded drugs, these services can be adapted for the generic space. They might include:

- Educational Materials: Providing clear, concise educational materials for clinicians and nurses on the generic product, including its specific packaging and administration instructions, to ensure a smooth transition from the brand.

- Patient-Facing Resources: Supplying patient information leaflets that proactively explain why their medication may look different, helping to mitigate confusion and improve adherence.

- Compliance and Safety Support: Offering support for hospital compliance initiatives, such as providing data for medication use evaluations (MUEs) or offering products that align with specific safety protocols.

Packaging, Labeling, and Safety

The physical attributes of the drug product itself can be a powerful source of operational value. P&T committees, and particularly their pharmacist members, are acutely aware of the role that packaging and labeling play in medication safety. A generic manufacturer that invests in superior packaging can create a distinct advantage.

Key areas of focus include:

- Unit-Dose Packaging: Providing medications in ready-to-administer unit-dose packaging is a major benefit for hospitals. It reduces the need for time-consuming and error-prone manual repackaging by the pharmacy staff, improves inventory control, and enhances patient safety at the bedside.

- Clear, Differentiated Labeling: Using “tall man” lettering and other visual cues to distinguish its product from look-alike, sound-alike (LASA) drugs is a critical safety feature that pharmacists value highly.

- Barcoding: Ensuring that all packaging levels, from the unit dose to the shipping case, have clear, scannable barcodes that are compatible with the hospital’s electronic health record (EHR) and automated dispensing cabinets is essential for modern pharmacy operations.

- Hazardous Drug Handling: For applicable drugs, providing packaging and labeling that is fully compliant with USP standards for handling hazardous drugs is a major compliance and safety benefit for the hospital.

These operational factors may seem minor compared to clinical efficacy or price, but in the context of a busy hospital, they have a significant cumulative impact on efficiency, safety, and cost. When a P&T committee is faced with two clinically and economically equivalent generics, the one that is easier to store, safer to dispense, and more reliable to procure will almost always win. By focusing on this third pillar, a generic manufacturer can build a moat around its product that is difficult for price-focused competitors to cross.

The Strategic Playbook: Crafting and Delivering a Winning Submission

Understanding the theoretical pillars of formulary acceptance is one thing; translating that understanding into a tangible, persuasive submission is another. This is where strategy meets execution. A winning submission is not just a collection of data; it is a carefully crafted narrative, delivered through the right channels at the right time. It requires mastering the official language of formulary review—the AMCP Dossier—while also leveraging modern communication tools like Pre-Approval Information Exchange (PIE) and harnessing the power of competitive intelligence to anticipate and neutralize threats. This is the tactical playbook for turning a well-reasoned value proposition into a formulary victory.

Mastering the Message: The AMCP Dossier as Your Narrative Guide

The cornerstone of any formal formulary submission is the dossier. In the United States, the universally recognized “gold standard” for the format and content of this document is the AMCP Format for Formulary Submissions, developed and maintained by the Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy.38 The AMCP Format provides a standardized structure for manufacturers to present clinical and economic evidence to healthcare decision-makers (HCDMs) in a comprehensive and consistent manner. Its purpose is to improve the timeliness, quality, and relevance of the information provided to P&T committees, thereby streamlining their review process and enabling more robust, evidence-based decisions. For a generic manufacturer, adhering to this format is not optional; it is a baseline expectation. However, true mastery lies in adapting the format to tell a compelling story specifically tailored to a generic product.

Deconstructing the AMCP Format for a Generic Drug

The AMCP Format is a comprehensive blueprint, typically organized into six main sections: an Executive Summary, Product and Disease Information, Clinical Evidence, Economic Value and Modeling, Additional Supporting Evidence, and Appendices.39 While the format is designed to accommodate novel branded drugs, its structure is perfectly suited for a generic submission, provided the content is framed correctly.

The Executive Summary is the most critical section. It is the manufacturer’s one chance to make a first impression and communicate the product’s entire value proposition in a concise, powerful narrative. For a generic, this summary must immediately establish therapeutic equivalence and then pivot quickly to the compelling economic and operational benefits.

The Product and Disease Information section should reaffirm the clinical context. It should briefly describe the disease state and the established role of the reference listed drug (RLD), thereby framing the generic as the logical, cost-effective continuation of a proven standard of care.

The Clinical Evidence section is where the generic must proactively address any potential “switch” anxiety. It should not merely state that the product is bioequivalent. A best-in-class generic dossier will present the clinical evidence comparatively. It will summarize the pivotal trials of the brand-name drug to reinforce the molecule’s efficacy and then present the generic’s bioequivalence data as definitive proof of sameness. As discussed previously, this section must also include a transparent profile of all excipients and any available real-world evidence to build maximum clinical confidence.

The Economic Value and Modeling Report is the heart of the generic’s argument. This section must contain a robust, transparent, and customizable Budget Impact Analysis (BIA). As outlined in Pillar 2, this BIA should go beyond simple acquisition cost savings to include quantifiable downstream cost offsets related to labor, waste, or ancillary services. The model itself should be provided in an unlocked, interactive format (e.g., an Excel spreadsheet) to allow the hospital’s own analysts to input their specific data and validate the projected savings—a key requirement of the AMCP Format that builds significant credibility.

The Generic Dossier: A Tactical Checklist

To translate these principles into an actionable plan, manufacturers should use a tactical checklist to guide the development of their dossier. This ensures that the standard requirements of the AMCP Format are not just met, but optimized for the specific narrative of a generic drug.

| Dossier Section (AMCP Format) | Standard Requirement | Generic-Specific Best Practice |

| 1.0 Executive Summary | Summarize the product’s clinical and economic value. | Lead with a clear statement of therapeutic equivalence and FDA approval. Immediately pivot to the top-line budget impact, quantifying projected annual savings for a model hospital. Conclude by highlighting key operational differentiators (e.g., supply guarantee, superior packaging). |

| 2.0 Product/Disease Info | Describe the product and its place in therapy. | Frame the generic as the cost-effective evolution of the established standard of care set by the brand. Emphasize continuity of care. |

| 3.0 Clinical Evidence | Provide summaries and tables of all relevant clinical studies. | Do not just state bioequivalence. Present a side-by-side comparison of the brand’s pivotal trial results with the generic’s bioequivalence data. Proactively include a detailed list of all excipients and their safety profiles. Include any available post-market real-world evidence (RWE). |

| 4.0 Economic Value & Modeling | Provide a transparent, interactive Budget Impact Model (BIM) and/or Cost-Effectiveness Analysis (CEA). | The BIA is paramount. Ensure it is a Cost-Minimization Analysis (CMA) framework. Build in customizable modules for downstream cost offsets (e.g., nursing time savings from ready-to-administer packaging, reduced lab monitoring costs). Provide the model in an unlocked format. |

| 5.0 Additional Supporting Evidence | Include clinical practice guidelines, HTA reviews, etc. | Highlight guidelines that recommend the active ingredient as a first-line therapy. Include a detailed “Operational Value” subsection here, with data on supply chain reliability (e.g., service level history, manufacturing redundancy), packaging benefits, and safety features (e.g., barcoding, LASA-safe labeling). |

| 6.0 Appendices | Include full reprints of cited studies, product labeling, etc. | Include a letter guaranteeing supply chain transparency and a commitment to proactive communication in the event of any potential disruptions. Provide a certificate of analysis for a recent batch to demonstrate quality. |

The Power of Proximity: Leveraging Pre-Approval Information Exchange (PIE)

In the past, the formulary review process began only after a drug received FDA approval. This created a significant lag between approval and patient access as P&T committees scrambled to gather and evaluate the necessary information. The regulatory landscape has now evolved to allow for Pre-Approval Information Exchange (PIE), a compliant pathway for manufacturers to proactively share clinical and economic information with payers before a product is approved. For a generic manufacturer, PIE is a powerful strategic tool that can dramatically shorten formulary decision timelines and shape the competitive landscape before the product even launches.

Payers and HCDMs are increasingly conducting formulary reviews well in advance of a product’s launch, and they expect early engagement from manufacturers. A 2022 survey of HCDMs found that the most crucial benefit of PIE was the timely access it provided to economic and clinical information, which is essential for preparing accurate budget impact analyses. The availability of pre-approval information was found to shorten formulary decision-making time for nearly half of the respondents. Crucially, HCDMs rated information on a product’s anticipated price and its place in therapy as the most impactful content for accelerating their review process.

For a generic manufacturer, the strategic implication is clear. PIE is not just about sharing data early; it is about setting and anchoring the P&T committee’s expectations for the post-patent-expiry market. The brand-name manufacturer will undoubtedly be executing its own lifecycle management strategy, perhaps attempting to switch the market to a new, more expensive formulation or casting doubt on the viability of generic competition. PIE allows the generic manufacturer to launch a pre-emptive strategic strike.

Months before the patent expires, the generic company can use a secure, compliant platform like FormularyDecisions to deliver a PIE dossier to key hospital systems.44 The message can be direct and powerful: “We want to inform you that the primary patent for Drug X will expire on. We have an ANDA under review at the FDA and anticipate launching our generic equivalent on Day 1 of patent expiry. We are providing our draft Budget Impact Analysis at this time, which projects an annual saving of Y% for an institution of your size. We hope this information is useful for your upcoming budget planning.”

This simple act accomplishes several critical objectives. First, it plants the seed of significant, forthcoming savings in the minds of the hospital’s financial planners, making them less receptive to the brand’s potentially costly “product hop” strategy. Second, it demonstrates a high level of transparency and professionalism, establishing the generic manufacturer as a proactive and reliable partner. Finally, it gives the P&T committee a significant head start on their review, allowing them to make a formulary decision much more quickly after the generic’s official launch, accelerating access and the realization of cost savings.

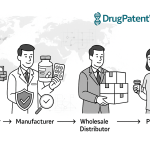

The Intelligence Edge: Using DrugPatentWatch for Competitive Dominance

The generic drug launch is a race against time, and the starting pistol is the expiration of the brand’s patent. However, a drug’s period of market exclusivity is rarely defined by a single, simple date. It is protected by a complex and overlapping web of composition of matter patents, formulation patents, method-of-use patents, and various regulatory exclusivities.47 For a generic manufacturer, navigating this “patent thicket” is the most critical and foundational step in developing a successful launch strategy. This is where patent intelligence becomes an indispensable competitive weapon.

Competitive intelligence platforms like DrugPatentWatch are designed to cut through this complexity. They provide comprehensive, curated databases of drug patents, track the real-time status of patent litigation, and offer predictive analytics on market entry opportunities. This transforms patent analysis from a reactive, data-lookup task into a proactive, strategic forecasting function. Proactive monitoring of patent expirations and competitor pipelines is consistently cited as a key strategy for success in the generic market.

Using a tool like DrugPatentWatch allows a manufacturer to move beyond the basics. The initial step is, of course, to identify the expiration date of the core composition of matter patent for a target drug. But the deeper strategic value lies in analyzing the entire intellectual property landscape. A sophisticated analysis will map out all secondary patents and their expiration dates, providing a clear picture of the brand’s defensive strategy. For example, if DrugPatentWatch reveals that a brand owner has filed three new patents on an extended-release formulation and another on a new pediatric indication in the years leading up to the primary patent’s expiration, this is a clear signal of their lifecycle management plan. They are building a patent thicket and likely planning a “product hop” to the new formulation to protect their franchise.

This intelligence is not merely interesting; it is profoundly actionable. Armed with this knowledge, the generic manufacturer can:

- Refine its R&D Strategy: Focus development efforts on a formulation that circumvents the brand’s new patents, creating a clear path to market.

- Strengthen its Legal Position: Prepare for potential patent litigation by understanding the specific claims of the brand’s secondary patents and developing non-infringement or invalidity arguments well in advance.

- Enhance its Formulary Submission: Tailor the economic argument in the AMCP dossier to directly address the brand’s anticipated moves. The BIA can model the significant cost savings of sticking with the original, proven generic versus switching to the brand’s new, marginally differentiated, and more expensive version.

- Inform its PIE Communications: Proactively warn P&T committees about the brand’s likely product hop strategy, framing it as a tactic designed to preserve revenue at the hospital’s expense.

In this high-stakes chess match, patent intelligence provides a view of the entire board. It allows the generic manufacturer to anticipate the innovator’s moves, plan a multi-step counter-strategy, and ultimately position its product not just as a copy, but as the smarter, more valuable choice for the healthcare system.

Navigating the Broader Ecosystem: The Invisible Hands of GPOs and Payers

The P&T committee does not operate in a vacuum. Its decisions are profoundly influenced by powerful external forces that shape the hospital’s purchasing environment and financial incentives. Two of the most significant of these are Group Purchasing Organizations (GPOs), which dominate the hospital supply chain, and Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs), whose control over outpatient formularies creates ripple effects that are felt within the hospital’s walls. A truly comprehensive generic drug strategy must account for the influence of these “invisible hands” and develop tactics to navigate their complex and often contradictory demands.

The GPO Gauntlet: Friend or Foe?

Group Purchasing Organizations are one of the most powerful and controversial entities in the healthcare supply chain. At their core, GPOs are intermediaries that aggregate the purchasing volume of their member hospitals—and an estimated 98% of U.S. hospitals belong to at least one—to negotiate discounts with manufacturers and suppliers.50 By leveraging this collective bargaining power, GPOs claim to generate significant savings for hospitals, with estimates ranging from 10% to 18% on contracted products.52 For a generic manufacturer, securing a contract with a major GPO like Vizient, Premier, or HealthTrust can provide access to a massive and immediate volume channel.

However, the GPO business model is fraught with potential conflicts of interest that can create significant barriers to market entry, particularly for smaller or newer generic manufacturers. The central controversy lies in their funding mechanism. GPOs derive the majority of their revenue not from the hospitals they serve, but from “administrative fees” paid by the very manufacturers with whom they negotiate.51 These fees, which are legally protected by a safe harbor provision under the federal anti-kickback statute, are typically calculated as a percentage of sales through the GPO contract. This creates a perverse incentive where the GPO’s revenue increases with the price and volume of the products sold, a dynamic that may not always align with the hospital’s goal of minimizing costs.

This business model drives a set of contracting practices that can stifle competition and create a fragile supply chain. To guarantee volume for manufacturers and thus secure higher administrative fees, GPOs often employ:

- Sole-Source Contracts: Awarding an exclusive contract to a single manufacturer for a particular product, effectively locking out all competitors for the duration of the contract.

- Bundling: Offering discounts that are contingent on a hospital purchasing a suite of products from a GPO’s portfolio, making it difficult for a manufacturer with a single product to compete, even if its product is superior or cheaper.

- Loyalty Rebates: Penalizing hospitals by retracting rebates if they fail to purchase a high percentage (often 90% or more) of their needs for a product category through the GPO contract.

These practices have been heavily criticized for raising barriers to entry, concentrating the market in the hands of a few large manufacturers, and contributing directly to the drug shortage crisis by driving prices so low that it becomes unprofitable for multiple manufacturers to remain in the market.50

This creates a complex, two-tiered market that a generic manufacturer must learn to navigate. The first tier is the high-volume, low-margin “commodity” market governed by the GPO contract. Winning here is a game of scale and aggressive pricing. The second tier is the lower-volume but potentially higher-value market that exists outside the GPO contract, where hospitals purchase directly to mitigate shortage risks or access innovative products. A successful generic company must develop a dual strategy. It can compete for the GPO contract on a high-volume, easily substitutable product where price is the only factor. Simultaneously, for a more critical product, such as a sterile injectable that is frequently on the national shortage list, it can bypass the GPO and negotiate directly with hospitals. The value proposition for this direct sale would not be the lowest price, but the highest reliability, backed by a contractual supply guarantee. This blended approach allows a manufacturer to build a balanced portfolio, capturing commodity volume through the GPO while building strategic, high-value relationships with hospitals directly.

The PBM Shadow: How Outpatient Trends Influence Inpatient Decisions

While GPOs are the dominant force on the inpatient side, Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs) control the outpatient prescription drug landscape. PBMs are hired by health insurance plans to manage their pharmacy benefits, and they do so by creating formularies, negotiating rebates with manufacturers, and contracting with retail pharmacies. Although their decisions apply to the prescriptions a patient fills after leaving the hospital, their influence extends back into the inpatient setting through a crucial and often overlooked factor: continuity of care.

A hospital P&T committee is not only concerned with the cost and efficacy of a drug used within its walls; it must also consider the patient’s transition back to the community. A seamless discharge process is a key quality metric for hospitals, as medication-related problems are a leading cause of costly and preventable hospital readmissions. A major source of friction in this process occurs when a patient is stabilized on a particular medication in the hospital, only to find that their outpatient insurance plan—managed by a P&T committee—does not cover that specific drug, or places it on a high-cost, non-preferred tier. This forces the hospital pharmacist and discharging physician to scramble to find a covered alternative, delaying the discharge and creating potential for confusion and error.

This “PBM shadow” creates a strategic opportunity for the forward-thinking generic manufacturer. A company’s hospital access strategy cannot be completely isolated from its managed care strategy. A generic drug that has already secured broad, preferential formulary access with the major national PBMs has a powerful and unique selling point to bring to the hospital P&T committee.

The value proposition can be framed directly around solving the hospital’s continuity of care problem. The message becomes: “By adding our generic to your inpatient formulary, you are not only realizing significant drug cost savings, but you are also streamlining the discharge process for the majority of your patients. Our product is already on the preferred generic tier for the three largest national payers, covering over 80% of your commercially insured patient population. This means fewer calls from your discharge pharmacists to physicians, less confusion for patients, and a lower risk of post-discharge medication non-adherence. We are not just a lower-cost alternative; we are the path of least resistance for a safe and efficient patient discharge.”

This approach brilliantly leverages a success in one market channel (managed care) to create a distinct competitive advantage in another (hospital). It demonstrates a holistic understanding of the patient journey and positions the generic manufacturer as a true partner in the hospital’s broader quality and efficiency goals. It is a sophisticated strategy that moves far beyond the simple calculus of price per pill.

The Final Mile: Driving Adoption and Sustaining Success Post-Acceptance

Gaining a spot on the hospital formulary is a landmark achievement, but it is the start, not the end, of the journey. A formulary listing without corresponding utilization is a hollow victory. The final, crucial phase of a successful generic launch involves actively driving adoption and sustaining momentum within the institution. This “final mile” requires a targeted education and communication strategy to win the hearts and minds of the frontline clinicians who will ultimately prescribe and administer the drug. It also requires learning from the successes and failures of others, using real-world case studies to understand the dynamics that separate a market leader from a formulary footnote.

Winning Hearts and Minds: Education and Communication for Stakeholders

Once a generic is on the formulary, the manufacturer’s focus must pivot from the P&T committee to the individual prescribers, pharmacists, and nurses. This is essential for overcoming the clinical inertia, brand loyalty, and patient anxiety that can suppress the uptake of a new generic, even a preferred one.25 The communication strategy must be tailored to the specific needs and concerns of each stakeholder group.

For physicians, the message must be clinical and data-driven. While they were represented on the P&T committee, the broader medical staff needs to be reached. Communication should reinforce the drug’s therapeutic equivalence, backed by a concise summary of the bioequivalence data. It is also critical to address any specific concerns relevant to their specialty. For example, for a cardiovascular drug, providing data on its performance in relevant patient subgroups can build confidence. The goal is to make the act of prescribing the generic feel like a seamless continuation of their established clinical practice.

For pharmacists and nurses, the focus should be on economics and logistics. This audience needs to understand the practicalities of the new product. Communication should highlight the operational benefits: the ease of use of unit-dose packaging, the clarity of the barcoding and labeling, and the manufacturer’s commitment to a reliable supply. Providing in-service training or clear, visual “conversion charts” that map the brand’s NDC number to the new generic’s NDC can greatly simplify the transition in the pharmacy and at automated dispensing cabinets.

For patients, communication must be simple, reassuring, and delivered through their most trusted source: their healthcare provider. The single most critical factor in a patient’s acceptance of a generic drug is a confident endorsement from their physician or pharmacist. Therefore, the manufacturer’s primary role is to equip clinicians with the tools and talking points to have these conversations effectively. This includes providing patient education leaflets that proactively address the most common source of anxiety: the change in the pill’s physical appearance. By explaining upfront that the medicine is identical but may look different due to trademark laws, providers can prevent the confusion and mistrust that often leads to non-adherence.25

Case Studies in Success: From Formulary Acceptance to Market Leadership

Examining real-world examples provides invaluable lessons in the complex dynamics of generic drug adoption. These case studies illustrate how formulary decisions can have far-reaching effects and why a nuanced, context-specific strategy is essential.

Case Study 1: The Gifu Municipal Hospital Effect – The Power of Institutional Influence

A study of the Gifu Municipal Hospital in Japan provides a compelling example of how a single institution’s formulary decisions can create a powerful ripple effect throughout a local healthcare ecosystem.56 When the hospital made a concerted effort to increase its adoption of generic drugs for its inpatients, the impact was not confined to its own pharmacy. The study found that in the year following the hospital’s initiative, the dispensation rate of generic drugs by surrounding community pharmacies for the hospital’s discharged patients rose by a remarkable 9.4 percentage points. Furthermore, the share of drug spending dedicated to generics at these pharmacies increased by 10.6 percentage points.

This “Gifu Effect” demonstrates that a hospital can act as a powerful influencer. By introducing patients to generic medications in the controlled and trusted inpatient setting, the hospital effectively educated and acclimated them to these products. Upon discharge, these patients were more likely to accept and continue using generics from their community pharmacies, driving down overall medical costs for the entire region. The strategic lesson for a generic manufacturer is clear: winning formulary access at a major, respected teaching hospital can serve as a beachhead, creating a halo effect that accelerates adoption across the entire local market.

Case Study 2: The VA System vs. Medicare – The Impact of Formulary Design

A comparison of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) healthcare system with the Medicare Part D program starkly illustrates the profound impact of formulary design on generic utilization. The VA system operates a highly centralized, national formulary that is predominantly closed and aggressively promotes the use of generics and therapeutic interchange. In contrast, Medicare Part D is a decentralized system of private plans, each with its own tiered formulary, where brand-name drug rebates can create incentives that sometimes favor brands over lower-cost generics.

The results are dramatic. One study of beneficiaries with diabetes found that the use of “multisource” brand-name drugs (brands for which an identical generic is available) was substantially higher in Medicare Part D compared to the VA system. The study estimated that Medicare could save $1.4 billion annually for patients with diabetes alone if its prescribing patterns mirrored those of the VA. Another analysis estimated that the potential savings from applying therapeutic interchange to just eight medication classes across the U.S. could exceed $20 billion annually. This case study highlights that the structure of the formulary system itself is a primary driver of generic uptake. For a manufacturer, it underscores the importance of understanding the specific system they are targeting. A strategy for a tightly controlled, closed system like the VA must focus on aggressive pricing and securing the sole-source contract, while a strategy for the complex Medicare Part D market requires navigating the intricate dynamics of PBM rebates and tier placement.

Case Study 3: The Antiepileptic Drug (AED) Challenge – A Cautionary Tale

The experience with generic substitution for antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) serves as a critical cautionary tale. AEDs are a class of drugs with a narrow therapeutic index, where even minor fluctuations in blood concentration can lead to a loss of seizure control or toxicity. While AEDs meet the same FDA bioequivalence standards as other drugs, numerous retrospective studies and case reports have documented instances of increased seizure frequency, breakthrough seizures, and new adverse events in patients who were stable on a brand-name drug and were switched to a generic version.

This has led to significant clinical concern and patient anxiety, resulting in high rates of patients switching back from the generic to the brand. Critically, some economic analyses have found that despite the lower acquisition cost of the generic AEDs, the total healthcare costs for patients who were switched actually increased. These increased costs were driven by more physician visits, emergency room trips, and hospitalizations needed to manage the loss of seizure control. This case study demonstrates that a myopic focus on drug acquisition cost can be counterproductive if it leads to negative clinical outcomes and higher downstream medical spending.

The strategic lesson is one of nuance and caution. For NTI drugs or other clinically sensitive therapeutic areas, a “winner-take-all” strategy aimed at completely replacing the brand may be inappropriate and could backfire. A more prudent approach might be to position the generic as the preferred, cost-effective option for newly initiated patients, while allowing patients who are stable and well-controlled on the brand to remain on their current therapy. This demonstrates a sophisticated understanding of clinical risk and a commitment to patient safety that can build long-term trust with the P&T committee and medical staff.

These cases, taken together, reveal that generic utilization is not a simple function of price. It is a complex interplay of institutional influence, system design, and clinical context. The most successful generic drug manufacturers will be those who can diagnose these contextual factors and tailor their value proposition accordingly, demonstrating a strategic flexibility that goes far beyond the molecule itself.

“When you have physicians and nurses and pharmacists rotating within the system, there’s less confusion if it’s standardized. We should be able to take care of patients the same way whether they’re at main campus or a regional hospital.” — Mandy Leonard, PharmD, BCPS, Director of Drug Use Policy and Formulary Management, Cleveland Clinic.

This insight underscores the powerful drive within large health systems for standardization. A generic drug that can position itself as a reliable, safe, and cost-effective standard of care is not just selling a product; it is providing a solution to one of the system’s most fundamental operational challenges.

Conclusion: The New Generic Value Proposition

The journey to securing and sustaining a place on the modern hospital formulary has transformed. The old paradigm, where generic success was a simple function of being the cheapest alternative upon patent expiration, is obsolete. Today’s healthcare landscape—defined by integrated health systems, value-based care models, and an intense focus on total cost and quality—demands a far more sophisticated and multi-dimensional approach. The new generic value proposition is not a single data point; it is a comprehensive, evidence-based narrative that speaks to the intertwined priorities of clinical efficacy, financial stewardship, and operational excellence.

Success in this new era requires a fundamental shift in mindset. Generic manufacturers must see themselves not as mere producers of commoditized molecules, but as strategic partners to the hospital. This means moving beyond the ANDA and the price list to build a case founded on the three pillars of formulary acceptance. The clinical case must be ironclad, proactively addressing the anxieties around switching by providing transparent, comprehensive data that builds unwavering confidence in the product’s therapeutic equivalence. The economic argument must be sharp and relevant, evolving from a simple cost-minimization claim to a sophisticated Budget Impact Analysis that quantifies not only direct drug savings but also the valuable downstream cost offsets that resonate with hospital administrators.

Most critically, in a market crowded with clinically and economically similar competitors, the operational value proposition has become the ultimate differentiator. In an age of persistent and costly drug shortages, a demonstrable and guaranteed reliable supply chain is no longer a “value-add”; it is a core component of quality and a powerful risk mitigation tool for the hospital. Combined with investments in safety-enhancing packaging and responsive customer service, operational excellence offers a path to building a durable competitive advantage that is insulated from pure price erosion.

Executing this strategy requires a new set of tools and tactics. It demands mastery of the AMCP Dossier as a narrative framework, the strategic use of Pre-Approval Information Exchange (PIE) to shape the market before launch, and the deep integration of patent intelligence from platforms like DrugPatentWatch to anticipate competitive threats and inform every aspect of the launch plan. It also requires an astute understanding of the broader ecosystem, navigating the complex incentives of GPOs and leveraging outpatient PBM coverage to solve the hospital’s challenges with continuity of care.

The path forward is clear. The generic manufacturers who thrive will be those who understand that the formulary is not a list to be conquered, but a system to be understood. They will be the ones who replace a singular focus on price with a holistic commitment to value, proving to the gatekeepers of the hospital that their product is not just the cheaper choice, but the smarter one.

Key Takeaways

- The Modern Formulary is a Management System: Treat the hospital formulary not as a static list, but as a dynamic system for managing medication use, cost, and safety. Your value proposition must align with the system’s goals, not just offer a low price.

- The P&T Committee is a Multi-Stakeholder Coalition: A winning submission must address the distinct priorities of each member of the P&T committee—the clinical concerns of physicians, the operational needs of pharmacists, and the budgetary constraints of administrators.

- Master the Three Pillars of Acceptance: A successful formulary case is built on three equally important pillars: an irrefutable clinical case proving therapeutic equivalence and safety, a compelling economic argument quantified by a sophisticated Budget Impact Analysis, and a differentiated operational value proposition highlighting reliability and safety.

- Supply Chain Reliability is the New Differentiator: In an era of chronic drug shortages, a guaranteed and reliable supply chain has become a critical quality metric. Manufacturers who can sell “certainty” can create a powerful competitive advantage that transcends price.

- Leverage Intelligence and Proactive Communication: Use patent intelligence platforms like DrugPatentWatch to inform your entire competitive strategy. Employ Pre-Approval Information Exchange (PIE) to engage with P&T committees early, shape their expectations, and shorten decision timelines post-launch.

- Think Beyond the Hospital Walls: Understand the influence of external players. Navigate the complex contracting environment of Group Purchasing Organizations (GPOs) and leverage your product’s coverage status with outpatient Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs) to create value around continuity of care.

- Adoption is as Important as Acceptance: Getting on the formulary is only the first step. A targeted post-acceptance education and communication plan for physicians, pharmacists, and nurses is essential to drive utilization and realize the product’s market potential.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. How important is a Budget Impact Analysis (BIA) for a generic drug submission, and how can it be made more effective?

A Budget Impact Analysis (BIA) is not just important; it is arguably the single most critical financial tool in a generic drug’s formulary submission. While the clinical case establishes equivalence, the BIA quantifies the primary reason for the switch: cost savings. To make it more effective, a generic manufacturer should go beyond a simple acquisition cost comparison. A best-in-class BIA should be presented within a Cost-Minimization Analysis (CMA) framework and include customizable modules for downstream cost offsets. This could include savings from reduced nursing time due to ready-to-administer packaging, lower laboratory monitoring requirements compared to the brand, or decreased waste from more efficient vial sizes. Providing the BIA as an unlocked, interactive model that allows the hospital to input its own data greatly enhances its credibility and impact.

2. With multiple generics of the same drug available, how can our company’s product stand out if pricing is similar?