In the unforgiving landscape of pharmaceutical innovation, where a single molecule can beget a multi-billion-dollar franchise and an overlooked patent can trigger catastrophic litigation, the quality of your intelligence is not just a competitive advantage—it is a survival imperative. Within this ecosystem, intellectual property is the bedrock of value. Patents are far more than legal documents; they are the financial instruments that justify staggering research and development investments, the strategic assets that shield blockbuster drugs from competition, and the chess pieces that define market control for decades.1

Historically, accessing and analyzing this critical information was the exclusive domain of highly trained specialists armed with expensive, subscription-based databases. Then, in 2006, Google Patents emerged.3 Leveraging the same technology that powered Google Books, it offered a seemingly infinite library of global patent documents to anyone with an internet connection, all for the unbeatable price of free.3 It was a revolutionary act of democratization, and its appeal is undeniable. With a familiar, clean interface and a database boasting over 120 million publications from more than 100 patent offices, it presents a powerful illusion of comprehensiveness and simplicity.6

This is the Siren’s Call of Google Patents—an irresistible, frictionless solution that promises a world of information without cost or complexity. It beckons to researchers, inventors, and even business strategists, offering quick answers and a high-level overview of the global patent landscape.9 But for professionals in the pharmaceutical industry, heeding this call is a perilous act. To rely on this generalist tool for the specialized, high-stakes work of drug patent analysis is to navigate treacherous waters in a vessel built for a placid lake.

While Google Patents can be a useful starting point for academic research or a casual lookup, its inherent limitations in data integrity, technical search capabilities, and legal reliability transform it from a helpful resource into a significant strategic liability when used for mission-critical tasks. Relying on it for freedom-to-operate (FTO) assessments, patentability searches, or competitive intelligence is not just a shortcut; it is a gamble with your company’s future. This report will dismantle the allure of Google Patents, exposing the critical gaps between what it appears to offer and what the pharmaceutical industry truly needs. We will explore the unique complexities of drug patents, dissect the platform’s fundamental data and functional deficiencies, and quantify the immense business risks these flaws create. Ultimately, this analysis will demonstrate that in the world of pharmaceutical patents, the perceived savings of a “free” tool are an illusion, masking a catastrophic increase in financial and strategic risk.

Part I: The Grand Deception – Unpacking the Allure of Google Patents

To understand the risks of Google Patents, one must first appreciate its undeniable appeal. It did not become a go-to resource for millions by accident. It succeeded by brilliantly executing Google’s core mission: to organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful. By applying this philosophy to the historically opaque world of patents, Google created a tool that is powerful, intuitive, and, on the surface, incredibly comprehensive. This combination of scale, usability, and zero cost creates a compelling value proposition that can easily lull users into a false sense of security, making them believe they have a professional-grade tool at their fingertips when they are, in fact, holding a dangerously blunt instrument.

A Universe of Information at Your Fingertips

The primary allure of Google Patents is the sheer, breathtaking scale of its database. For any researcher, the ability to query a single search bar and receive results from across the globe is a paradigm shift from the siloed, national databases of the past. The platform boasts an astonishing volume of data, indexing over 120 million patent publications from more than 100 different patent offices.6 This includes all the major jurisdictions critical to the pharmaceutical industry: the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO), the European Patent Office (EPO), the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), and the national offices of China, Japan, Canada, Germany, and the United Kingdom, among many others.5 This provides an immediate, high-level overview of the global state of an art that was once the exclusive domain of highly trained specialists with expensive subscriptions.

But the platform’s reach extends beyond just patents. Recognizing that innovation is often published in scientific journals long before it appears in a patent application, Google has integrated a vast repository of non-patent literature (NPL). To make prior art searching easier, Google Patents includes copies of technical documents and books indexed in its sister services, Google Scholar and Google Books, as well as documents from the Prior Art Archive.6 This is a genuinely powerful feature. In many fields, particularly biotechnology and chemistry, a thorough prior art search is incomplete without a review of academic literature.

What makes this integration particularly seductive is that Google has gone a step further and machine-classified these NPL documents using the Cooperative Patent Classification (CPC) system—the same detailed taxonomy used to organize patents themselves.4 In theory, this allows a user to search a specific technological niche (e.g., a CPC code for monoclonal antibodies) and seamlessly retrieve both patent documents and relevant scientific papers. This creates a powerful veneer of comprehensiveness, suggesting that a single search on Google Patents can provide a complete view of the state of the art, covering both patented and unpatented knowledge.

An Interface Built for Humans, Not for Specialists

If the vastness of the data is the first part of the Siren’s Call, the second is its effortless usability. Google Patents was deliberately designed to feel familiar and intuitive, lowering the barrier to entry for users who are not trained patent search professionals.5 The interface is clean, minimalist, and operates on the same principles as a standard Google web search, a process with which billions of people are already comfortable.8 A user can simply type a few keywords—a drug name, a technology, an inventor—and immediately receive a list of relevant-looking documents, creating a frictionless and satisfying user experience.

This user-centric design is enhanced by a suite of genuinely useful features. The platform offers on-the-fly machine translation of foreign-language patents, allowing an English-speaking user to get the gist of a document from Japan or Germany without needing a professional translator.5 While not perfect, this feature provides a level of accessibility to foreign art that is unprecedented for a free tool.

The presentation of information is also clean and logical. A patent’s abstract, claims, and description are often laid out in an easy-to-read, side-by-side format, a significant improvement over the clunky PDF viewers of many official patent office websites. The sequence of legal events is provided systematically, and results can be easily saved to a user’s Google account or shared with colleagues via a simple link, facilitating collaboration.5 This entire experience is engineered to be fast and intuitive, delivering results in a fraction of a second.

However, this is precisely where the danger lies. The very strengths that make Google Patents so appealing to a general audience are its greatest weaknesses for a pharmaceutical specialist. The platform’s apparent comprehensiveness is a veneer that masks critical gaps, lags, and inaccuracies in the data. Its elegant simplicity is an illusion, abstracting away the necessary complexity of professional-grade searching and analysis. This fundamental mismatch between the tool’s design philosophy—mass access to “good enough” information—and the user’s high-stakes requirement for perfect, reliable, and legally precise data is the central flaw that makes relying on it for drug patent analysis a strategic blunder. A user can get an answer quickly, but in the world of pharma, an answer that is merely “close” or “mostly right” is functionally equivalent to one that is completely wrong.

Part II: The Pharmaceutical Patent Gauntlet – A World Apart

To fully grasp the inadequacy of a generalist tool like Google Patents, one must first understand that pharmaceutical patents are not just another category of intellectual property. They exist in a unique ecosystem defined by staggering financial stakes, immense complexity, and a deep, symbiotic relationship with government regulation. The process of searching for and analyzing these patents is not a simple document retrieval exercise; it is an act of strategic navigation through a multi-layered fortress designed to protect assets worth billions of dollars. The economics and structure of pharmaceutical IP are so distinct that they create a set of search and analysis requirements that a tool designed for mass-market accessibility simply cannot meet.

The Billion-Dollar Bet: R&D Costs and the Patent Cliff

The context for every decision in the pharmaceutical industry is the monumental cost and risk of drug development. The journey from a promising molecule in a lab to an approved drug on a pharmacy shelf is a decade-long odyssey fraught with failure. The most widely cited figure, from the Tufts Center for the Study of Drug Development, estimates the average capitalized cost to develop a new prescription drug and bring it to market at a staggering $2.6 billion.12 This figure accounts not only for direct spending but also for the cost of capital and, critically, the cost of the many failures along the way—only about 12% of drugs that enter clinical trials are ever approved by the FDA.

The patent system is the fundamental mechanism that makes this high-risk investment possible. A patent grants a limited period of market exclusivity, typically 20 years from the filing date, allowing the innovator company to recoup its investment and, ideally, generate a profit to fund the next wave of research.2 The flip side of this value creation is the ever-present “patent cliff,” a term that describes the dramatic and often devastating loss of revenue when a blockbuster drug’s core patents expire and lower-cost generic versions flood the market. It is not uncommon for a drug to lose 80-90% of its market share within a year of generic entry.

These are not just abstract economic concepts; they are the forces that define the required level of rigor for patent analysis. When a single patent can be the sole barrier protecting billions of dollars in annual revenue, the cost of missing a critical piece of information is astronomical. For example, AbbVie’s blockbuster drug Humira has generated nearly $200 billion in revenue while under patent protection. Over the next five years alone, the pharmaceutical industry faces an estimated $200 billion in revenue at risk from expiring patents. In this environment, patent analysis is not an administrative task; it is a core business function responsible for safeguarding the company’s most valuable assets. The investment in premium, specialized tools is not a luxury; it is a rounding error compared to the value at stake.

The Anatomy of a Patent Fortress

A common misconception among non-specialists is that a drug is protected by “a patent.” In reality, a successful drug is shielded by a multi-layered “patent fortress,” a strategically constructed portfolio of different patent types designed to protect the asset from every conceivable angle and throughout its entire commercial lifecycle. This evolution from a “molecule-centric” to a “lifecycle-centric” IP strategy is one of the most significant developments in the industry. A valid search strategy must be able to identify and analyze all the different layers of this fortress, something a simple keyword search is guaranteed to miss.

The Crown Jewel: Composition of Matter Patents

The foundational layer of protection, often considered the “gold standard” or “crown jewel” of a drug’s IP portfolio, is the composition of matter patent. This type of patent, also known as an active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) or compound patent, covers the core chemical entity itself. Its power lies in its breadth; if the molecule is present in a product, the patent applies, regardless of how it was manufactured, what it is formulated with, or for which disease it is being used. For investors and competitors alike, the status and remaining term of the core composition of matter patent is the single most important piece of IP intelligence for a new drug.

Expanding the Moat: Formulation and Process Patents

Innovator companies rarely stop with the composition of matter patent. They strategically file for additional patents on new formulations that offer improvements, such as a sustained-release version that allows for once-daily dosing instead of multiple times a day. They also patent the specific processes used to manufacture the drug.17 These patents are critical components of a lifecycle management strategy, often called “evergreening,” designed to extend market exclusivity long after the original compound patent expires.19 For example, when Lilly’s patent on the blockbuster antidepressant Prozac was set to expire, the company developed and patented a new once-weekly, sustained-release formulation to protect its market share.

New Tricks for an Old Drug: Method-of-Use Patents

Another powerful layer of the fortress is the method-of-use patent. This type of patent does not cover the drug itself but rather its use to treat a specific disease or condition.1 This allows a company to find new value in an existing asset. For instance, a company might discover that a drug originally approved for epilepsy is also effective at treating migraines. By conducting new clinical trials and securing a method-of-use patent for this new indication, the company can gain a fresh period of market exclusivity specifically for the use of that drug in treating migraines, even if the original compound patent is nearing expiration.

The Thicket and the Fortress: Strategic Layering

The deliberate, systematic layering of these various patent types creates what is often referred to as a “patent thicket”—a dense, overlapping, and often intimidating network of intellectual property.17 This is not an accident; it is a core business strategy designed to create significant legal and financial hurdles for any potential generic competitor, who must now navigate and potentially challenge dozens of patents instead of just one.17 Understanding the full scope of a drug’s protection requires identifying and analyzing every patent in this thicket.

The Regulatory Overlay: FDA Linkage and Data Exclusivity

The complexity of the pharmaceutical patent gauntlet is amplified by its deep integration with the regulatory system. In the United States, a drug’s market protection is a hybrid of patent rights and regulatory exclusivities granted by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). A tool that only looks at patents provides an incomplete and dangerously misleading picture of a drug’s lifecycle and the true timeline for generic entry.

The Hatch-Waxman Act created a system where brand-name drug manufacturers list the patents they believe cover their approved drugs in an FDA publication known as the “Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations,” or the “Orange Book”.23 When a generic company wants to market a copy, it must certify against these listed patents. If it challenges a patent’s validity or infringement (a “Paragraph IV” certification), it triggers an automatic 30-month stay of FDA approval for the generic while the patent dispute is litigated in court. For biologics, a similar system exists with the “Purple Book”.

Furthermore, the FDA grants its own forms of market protection, completely independent of patents. A New Chemical Entity (NCE) can receive five years of “data exclusivity,” during which the FDA cannot approve a generic application that relies on the brand’s clinical trial data, regardless of the patent status.26 Other exclusivities exist for orphan drugs (treating rare diseases) and for conducting pediatric studies.

This creates a critical disconnect between a patent as a legal document and a patent as a strategic asset. Google Patents is fundamentally a document retrieval system, designed to find and display patent documents based on keywords and classifications.3 But in the pharmaceutical industry, a patent is not just a document; it is a strategic asset whose value is inextricably linked to a specific drug product, a regulatory timeline, clinical trial data, and a market revenue stream.1 The “value” of that patent can only be understood by connecting it to this external, non-patent data—Orange Book listings, FDA approval dates, sales figures, and litigation outcomes. Because Google Patents does not integrate this critical regulatory and commercial context, it can only ever show you the document, not the asset. It can find a patent

mentioning a drug, but it cannot tell you if that patent is the one listed in the Orange Book that is blocking generic entry, what its real-world market exclusivity impact is, or when a generic company is likely to challenge it. This is the fundamental disconnect that renders it unsuitable for any serious strategic analysis.

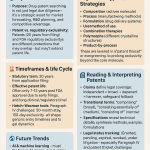

Part III: The Cracks in the Foundation – Google’s Critical Data Deficiencies

While the allure of Google Patents lies in its massive, seemingly comprehensive database, the integrity of that data is its Achilles’ heel. For the pharmaceutical industry, where decisions are measured in millions of dollars and decades of research, the quality, timeliness, and accuracy of information are non-negotiable. It is in these fundamental areas that Google Patents reveals its most critical flaws. A strategy built upon the data within Google Patents is a strategy built on shifting sands, vulnerable to the hidden risks of data lags, jurisdictional gaps, and legally unreliable information. These are not minor bugs or occasional errors; they are systemic deficiencies in the platform’s data pipeline that contaminate any analysis built upon them.

The Peril of Lag Time: When “Recent” Isn’t Recent Enough

In the fast-paced world of pharmaceutical R&D and IP strategy, access to the most current information is paramount. A generic company needs to know the instant a key patent expires to plan its launch. An innovator company needs to know about a competitor’s newly published patent application to get an early warning of a new threat, enabling a potential pivot in R&D strategy. In both scenarios, timeliness is everything.

This is where Google Patents falters significantly. Multiple independent analyses and user reports confirm that the database is not updated in real-time. There is often a considerable lag, ranging from several weeks to even a couple of months, between when a patent document is officially published by a patent office and when it becomes discoverable on Google Patents.5 For example, a new patent application published by the USPTO on a Thursday might not appear in Google’s index for weeks.

During that critical window, a researcher relying solely on Google Patents is operating with a significant blind spot, completely unaware of a potentially pivotal new piece of prior art or a competitive filing. This lag time is especially dangerous because it compounds the inherent 18-month publication delay built into the patent system itself. In the U.S. and many other jurisdictions, patent applications are kept confidential for the first 18 months after their earliest priority date.5 This already creates a period of uncertainty for companies assessing the patent landscape. The additional, unpredictable update delay from Google Patents extends this period of uncertainty even further, increasing the risk that a company will invest heavily in a project only to be blindsided by a prior art reference that was publicly available but not yet indexed by their search tool of choice. For a freedom-to-operate (FTO) search, where the goal is to ensure a new product does not infringe on any

active patents, this delay is unacceptable. It means any FTO clearance based on Google Patents data is outdated the moment it is completed.

Jurisdictional Blind Spots: The Myth of “Global” Coverage

Google Patents’ claim of indexing documents from over 100 patent offices creates a powerful impression of comprehensive global coverage.6 However, the fine print reveals a more complex and concerning reality. Google itself explicitly states that it “cannot guarantee complete coverage” of all documents from these offices. This is not just a standard legal disclaimer; it reflects tangible gaps in the data that can have severe consequences for pharmaceutical companies operating in a global market.

The pharmaceutical market is intrinsically global, and a proper FTO analysis must be as well. A product may be off-patent in the United States but still protected in key European or Asian markets. A search that has blind spots in major markets is not a comprehensive search; it is a box-ticking exercise that creates a false sense of security. Reports from IP professionals indicate that important patent data from countries like China, Japan, and India—all critical markets and sources of innovation—may be missing or only partially indexed on the platform.

Furthermore, even when a foreign patent document is present, its utility may be limited. For many foreign patents, Google Patents provides only an abstract, not the full-text document that is essential for a proper legal analysis. While the platform’s machine translation feature is useful for getting the “gist” of a document, it is notoriously unreliable for the complex technical and legal terminology found in patent claims.31 A mistranslated term can completely alter the perceived scope of a patent claim, leading to a disastrously incorrect conclusion about infringement risk. Relying on such translations for anything more than a preliminary screening is a significant gamble.

Legal Status Roulette: Relying on Data Google Itself Disclaims

Perhaps the most dangerous deficiency of Google Patents is the unreliability of its legal and bibliographic data. For any patent analysis, a few questions are fundamental: Is this patent active, expired, or abandoned? Who is the current owner? Has it been challenged in court? A mistake on any of these points can invalidate an entire strategic plan.

Google Patents is demonstrably unreliable for answering these questions. The platform often has significant delays or outright inaccuracies in its legal status updates. A patent that has lapsed for non-payment of maintenance fees might still appear as “active,” while a patent that has been successfully challenged and invalidated might not reflect this change for months, if ever.29 Google itself makes no guarantees about the accuracy of this data and does not track real-time ownership changes or assignments.29 A case study highlighted a startup that invested in licensing a patent found on Google Patents, only to discover later through a professional service that the patent had already lapsed.

This problem is compounded by the inherent messiness of applicant and assignee data. A single large pharmaceutical company may file patents under dozens of different subsidiary names. Typos, abbreviations, and inconsistent naming conventions are rampant in the raw data filed at patent offices. Without sophisticated data cleaning and corporate tree mapping—a value-added service provided by professional databases—it is nearly impossible to get an accurate picture of a competitor’s true portfolio size or scope.34 A search for “Pfizer” might miss patents assigned to “Pfizer Inc.,” “Pfizer Products Inc.,” or acquired entities like “Wyeth” or “Pharmacia.”

The problem of inaccurate data extends even to supposedly curated sources like the FDA’s Orange Book. In recent years, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) has aggressively challenged hundreds of patents as being “improperly” or “inaccurately” listed by brand-name companies, arguing these “junk patent” listings serve only to block lower-cost generic competition.24 This is a level of nuance—distinguishing between a properly and improperly listed patent—that a generalist tool like Google Patents is completely unequipped to handle. It simply scrapes and displays the data, regardless of its underlying validity or strategic context.

This systemic data unreliability means that using Google Patents for critical legal status or ownership information is like playing roulette. A decision to launch a generic product based on a patent that appears “expired” on Google could lead to an infringement suit if the data is wrong. A decision to abandon an R&D project because of a “blocking” patent could be a costly mistake if that patent is actually owned by a different entity willing to license it, or if it is no longer in force.

This is not about a single bad data point; it is about systemic contamination. The flawed data from Google Patents flows downstream and pollutes every subsequent analysis and decision. An FTO search based on outdated legal status is flawed. A competitive landscape analysis based on incorrect assignee names is flawed. An R&D decision based on an incomplete prior art search is flawed. The initial “free” data ends up costing the organization dearly in the form of bad decisions, missed opportunities, and unforeseen risks.34 The true cost is not in the tool, but in the consequences of using it.

Table 1: The Data Integrity Deficit: How Flawed Data Derails Decisions

| Data Deficiency | Description | Impact on FTO Analysis | Impact on Competitive Intelligence | Impact on Patentability/Validity Search |

| Data Lag | Weeks-to-months delay in updates from official patent offices. | Misses recently published blocking patents, rendering the FTO outdated upon completion. | Provides an outdated view of competitor filings and strategic direction. | May miss the most relevant or “killer” prior art that has been recently published. |

| Incomplete Coverage | Gaps in global data, especially full-text for foreign patents and in key jurisdictions.30 | Creates dangerous blind spots in key global markets, leading to a false sense of clearance. | Fails to capture the full global IP strategy and footprint of competitors. | A supposedly “global” prior art search is not truly global, risking an invalid patent filing. |

| Inaccurate Legal Status | Outdated or incorrect data on whether a patent is active, expired, reassigned, or litigated. | May lead to launching based on an expired patent or abandoning a project due to a “zombie” patent. | Incorrectly assesses the strength, ownership, and enforceability of a competitor’s portfolio. | Wastes time analyzing irrelevant (expired) prior art or challenging the wrong patent owner. |

Part IV: A Blunted Instrument – The Critical Search Capabilities Pharma Needs (and Google Lacks)

Beyond the fundamental issues of data integrity, Google Patents is also functionally inadequate for the specific needs of pharmaceutical patent analysis. The language of drug innovation is often not expressed in words, but in the precise arrangement of atoms in a molecule or the specific sequence of amino acids in a protein. Drug patents are defined by their chemical structure or biological sequence, not just by keywords. A search tool that is functionally blind to these core modalities is like an art historian who cannot see images or a musicologist who cannot hear sound. It is missing the very essence of the subject matter, forcing users to rely on crude and ineffective workarounds that are bound to fail.

Searching by Sight: The Inability to Perform Chemical Structure Search

Arguably the single greatest technical failure of Google Patents for the pharmaceutical industry is its complete inability to perform chemical structure searches. For small-molecule drugs, which still represent a vast portion of the market, the invention is the molecule. The “crown jewel” composition of matter patent legally defines the invention not by its name, but by its two-dimensional or three-dimensional structure.1

Professional patent databases designed for chemists and pharmaceutical researchers, such as CAS SciFinder, Derwent Chemistry Research, Minesoft ChemX, and Questel’s Orbit Chemistry, have this capability at their core.37 These platforms allow a user to draw a chemical structure using a specialized editor and then search for patents containing:

- Exact Matches: Finding the precise molecule of interest.

- Substructure Matches: Finding any molecule that contains a specific core or fragment (a “scaffold”) that the user has drawn. This is essential for understanding a competitor’s broader chemical space and for identifying potential infringement by related compounds.

- Similarity Matches: Finding molecules that are not identical but have a similar overall structure, which can be critical for identifying compounds with potentially similar biological activity.

Google Patents offers none of this. A user is limited to text-based searching, meaning they can only search for a drug’s name (e.g., its brand name, generic name, or a formal IUPAC chemical name). This is a hopelessly inadequate proxy for a real structure search. Patent attorneys are often careful not to use a common drug name in a patent to avoid limiting its scope. A patent may describe a class of compounds using a generic “Markush” structure, which represents thousands or even millions of potential molecules with a single drawing, none of which are explicitly named. Without the ability to search by structure, a researcher using Google Patents is completely blind to this entire universe of relevant patents. It is a fatal flaw that makes the tool fundamentally unsuitable for any serious chemical patent work.

The Language of Life: The Absence of Biologic Sequence Searching

What structure searching is to small molecules, biologic sequence searching is to the rapidly growing field of biologics—monoclonal antibodies, cell and gene therapies, therapeutic proteins, and vaccines. For these complex products, the invention is often defined by a specific nucleotide sequence (for DNA or RNA) or an amino acid sequence (for a protein). According to one analysis, over 80% of biopharmaceutical patents are centered on these sequences.

A freedom-to-operate analysis for a new therapeutic antibody, for example, absolutely requires a search for any existing patents that claim antibodies with identical or highly similar Complementarity-Determining Regions (CDRs)—the parts of the antibody that bind to the target. This is done using specialized algorithms like BLAST (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool) that compare a query sequence against a massive database of patented sequences.

Once again, Google Patents completely lacks this essential capability. There is no way to input an amino acid or nucleotide sequence and search for patents claiming similar sequences. This renders the tool entirely useless for FTO, patentability, or competitive intelligence work in the biologics space, which is arguably the most dynamic and valuable sector of the pharmaceutical industry today. Specialized platforms, and even some free public databases like WIPO’s PATENTSCOPE, offer dedicated sequence search tools precisely because the industry recognizes it as a non-negotiable requirement.30 Google’s omission of this feature underscores its fundamental disconnect from the needs of modern life sciences IP analysis.

The Limits of Language: Weak Boolean/Proximity and Semantic Mismatch

Even within its native domain of text searching, Google Patents is a blunted instrument compared to professional-grade tools. While it supports basic Boolean operators like AND, OR, and NOT, its implementation lacks the power and precision required for serious patent analysis.8

Professional patent searchers rely heavily on sophisticated proximity operators to establish context and reduce noise. For example, a searcher might want to find patents where the term “osimertinib” appears within five words of the term “resistance” (e.g., osimertinib NEAR/5 resistance). This ensures that the results are highly relevant, discussing resistance to that specific drug, rather than just documents that happen to mention both words hundreds of paragraphs apart. Google’s support for these advanced operators is limited and can be inconsistent, often returning a flood of irrelevant results (“noise”) that buries the few relevant documents (“signal”). This forces the analyst to waste countless hours sifting through junk or, worse, to give up and miss the key document entirely.

Furthermore, the core search algorithm, built on the same principles as web search, can interpret queries in unexpected ways, reducing trust in the completeness of the results. It is designed for semantic relevance, which is great for finding a recipe for lasagna, but potentially disastrous for legal analysis, where the precise, literal meaning of the words in a claim is what matters.

This reality exposes a crucial truth: the limitations of a tool fundamentally constrain the types of questions you are able to ask. A pharmaceutical IP strategist needs to ask highly specific, technical questions: “Does anyone have a patent on a molecule with this specific pyrimidine core and a halogen at position 5?” or “Is there a patent claiming an antibody with these three specific CDR sequences?” These are questions of structure and sequence, not keywords.

By forcing all queries through a text-based interface, Google Patents compels its users to ask the wrong, dangerously oversimplified questions. Instead of asking the right question (“Who has a patent that my drug’s structure might infringe?”), the user is forced to ask the wrong one (“Who has a patent that mentions my drug’s name?”). This is a fundamental flaw in the intelligence-gathering process. When you cannot ask the right question, you can never be confident you have the right answer.

Part V: The Specialist’s Advantage – Integrating Data for True Intelligence

The shortcomings of Google Patents are not just about missing features; they highlight a fundamental difference in philosophy. Google Patents is a search engine—a powerful library that gives you access to individual documents. Professional pharmaceutical IP platforms, in contrast, are intelligence systems. Their true value lies not just in superior search functions, but in their ability to connect disparate, critical datasets—patent, regulatory, litigation, and clinical—into a single, cohesive platform. This integration transforms raw data into actionable business intelligence, allowing users to move beyond simple document retrieval to genuine strategic analysis.

Beyond the Document: Connecting Patents to Products and Regulations

As established, a drug’s market exclusivity is a complex interplay of patents and regulatory protections. A patent’s strategic value is meaningless without this context. This is where specialized platforms like DrugPatentWatch provide an insurmountable advantage. They are built on the principle of data integration.30

These platforms don’t just contain patent data; they meticulously link it to the corresponding drug products and their regulatory status. A user can search for a drug like Keytruda and instantly see not just a list of patents that mention it, but the specific patents that Merck has listed in the FDA’s Purple Book as covering the product.25 They can see the expiration dates of those patents alongside the expiration dates of any regulatory exclusivities, such as orphan drug or pediatric exclusivity.28 They can see which generic or biosimilar companies have filed Abbreviated New Drug Applications (ANDAs) or Biologics License Applications (BLAs) and have challenged those patents.26

This integration is the key to moving from “document retrieval” to “strategic analysis.” It allows a business leader or IP strategist to answer the questions that actually matter:

- Which specific patents are actually blocking generic entry for this drug?

- What is the true Loss of Exclusivity (LOE) date, considering the full picture of both patents and regulatory data?

- Which competitors have already filed challenges, and what is the status of that litigation?

- Are there opportunities for a 505(b)(2) application, which leverages existing FDA data for a new formulation or indication?

Google Patents, by its very design as a document-centric search engine, cannot answer any of these questions. It shows you the patent document in isolation, divorced from the commercial and regulatory reality that gives it meaning.

From Text to Action: Analysis, Visualization, and Collaboration Tools

Finding the relevant patents is only the first step. The real work lies in analyzing them to extract insights. Professional platforms are equipped with a suite of analytical and visualization tools designed to make this process efficient and insightful, whereas Google Patents provides a raw list of results and leaves the rest to the user.

These tools include:

- Landscape Visualization: Instead of a text list, these platforms can generate interactive charts and graphs that map out the patent landscape for a specific technology area. This can instantly reveal which companies are most active, what technological approaches are most common, and, most importantly, where the “white space” is—untapped areas with little patent activity that could represent R&D opportunities.32

- Automated Alerts and Monitoring: Professionals cannot afford to be reactive. They need to know about critical events as they happen. Specialized platforms offer customizable alerts that will notify a user automatically when a competitor files a new patent application in their field, when the legal status of a key patent changes, or when new litigation is initiated.32 This transforms competitive monitoring from a manual, periodic chore into an automated, real-time process.

- Citation Analysis Tools: Understanding how patents are connected through citations is key to identifying foundational inventions and tracking the flow of innovation. Professional tools provide robust citation analysis features that go far beyond the simple lists in Google Patents, helping to assess a patent’s influence and impact.

- Collaborative Workspaces: Patent analysis is rarely a solo endeavor. It involves collaboration between IP attorneys, R&D scientists, and business development teams. Professional platforms provide shared workspaces where teams can save, annotate, and discuss search results, ensuring that everyone is working from the same set of information and insights are not lost in scattered email chains and spreadsheets.

Without these integrated tools, users of Google Patents are forced to export their results and attempt to perform these analyses manually in programs like Excel—a process that is not only incredibly inefficient and time-consuming but also highly prone to error and impossible to scale.

The Human Element: Curation, Expertise, and Support

Finally, a critical advantage of professional platforms is the “human-in-the-loop” model that underpins their services. The world’s patent data is notoriously messy. A purely automated system like Google’s inevitably ingests and reproduces these errors.

Paid services invest heavily in data curation. This involves teams of subject matter experts who manually review and clean the data. They standardize inconsistent assignee names and build out corporate trees so that a search for a parent company reliably retrieves the patents of all its subsidiaries.34 For chemical and biological patents, they perform expert indexing, manually extracting structures and sequences from patent text and drawings to make them searchable—a task that AI still struggles to perform with perfect accuracy.39 This human curation is what transforms messy, unreliable raw data into the high-quality, trustworthy information needed for high-stakes decisions.

Furthermore, these services come with expert customer support. When a user has a complex search question or needs help interpreting a result, there is a team of specialists available to assist. Google Patents, like most free Google products, offers no such support, leaving users to fend for themselves.

This distinction highlights the fundamental difference between a search tool and an intelligence solution. It is the difference between a library and an intelligence agency. A library gives you access to an immense collection of books (documents), but it is up to you to find them, read them, synthesize their contents, and figure out how they connect on your own. An intelligence agency provides you with a synthesized briefing (intelligence) that has already been curated, analyzed, and contextualized, telling you what’s important, why it matters, and what might happen next. For pharmaceutical companies navigating the patent gauntlet, simply “searching” is not enough. They require “intelligence” to compete, and that is what specialized platforms are built to deliver.

Table 2: Feature Face-Off: Google Patents vs. Professional Pharmaceutical IP Platforms

| Feature / Capability | Google Patents | Professional Platforms (e.g., DrugPatentWatch) |

| Data Update Frequency | Lag of weeks to months; not real-time 5 | Daily updates from primary sources; near real-time |

| Legal Status Accuracy | Disclaimed, often inaccurate or outdated 5 | Curated and verified, with integrated litigation data 30 |

| Guaranteed Jurisdictional Coverage | “Cannot guarantee complete coverage” ; gaps in full-text | Defined, guaranteed coverage for key global jurisdictions |

| Chemical Structure Search | None; text-based only | Yes; exact, substructure, and similarity search |

| Biologic Sequence Search | None | Yes; integrated BLAST and other sequence search tools 30 |

| Advanced Proximity/Boolean Operators | Limited and inconsistent implementation | Robust support for NEAR, ADJ, and complex nested queries |

| Integrated Regulatory Data (FDA) | None | Yes; deep integration with Orange Book, Purple Book, exclusivities, and ANDA filings 1 |

| Integrated Litigation Data (PTAB/Court) | Limited, via a link-out to a third party | Yes; fully integrated litigation records and outcomes 1 |

| Automated Alerts & Monitoring | None | Yes; customizable alerts for new patents, litigation, and status changes |

| Expert Curation & Support | None; fully automated | Yes; human data curation, expert indexing, and dedicated customer support 34 |

Part VI: The Business Risk Multiplier – Quantifying the Cost of Getting It Wrong

The deficiencies of Google Patents are not merely academic points of comparison. They translate directly into tangible, high-impact business risks. In the pharmaceutical industry, the consequences of a flawed patent analysis are not measured in wasted time, but in millions of dollars in litigation costs, billions in lost market opportunity, and derailed R&D programs. The decision to use a “free” tool can become catastrophically expensive when its inherent flaws lead to a compromised freedom-to-operate analysis, a missed competitive threat, or an avoidable legal battle. The perceived cost saving is an illusion that masks a dramatic multiplication of real-world business risk.

The Flawed Freedom-to-Operate (FTO) Analysis: A Recipe for Disaster

Of all the tasks an IP professional performs, the freedom-to-operate (FTO) analysis is arguably the most critical for commercialization. An FTO is not a search for what is patentable; it is a search to determine if a planned commercial product will infringe on any active, in-force patents held by others.49 It is the strategic lifeline that prevents a company from investing hundreds of millions of dollars to develop a drug only to be blocked from launching it by a competitor’s patent. The decision to proceed without a clear understanding of the patent landscape is, as one expert put it, analogous to “building a skyscraper without checking if the land belongs to someone else”.

Using Google Patents for an FTO analysis is a recipe for disaster. The combination of its critical flaws makes it wholly unsuitable for this high-stakes task:

- Data Lags: A database that is weeks or months out of date means you could conduct your entire FTO search and completely miss a recently published and highly relevant blocking patent that was filed 18 months ago.

- Inaccurate Legal Status: An FTO is only concerned with in-force patents. Relying on Google’s outdated legal status data means you might waste time analyzing an expired “zombie” patent or, far worse, incorrectly conclude a valid, in-force patent has lapsed and give a false “all clear” for launch.31

- Functional Blindness: The lack of chemical structure and biologic sequence search capabilities means you will, by definition, fail to find the most relevant patents for your drug. The core of your invention—its structure or sequence—is unsearchable on the platform.

An FTO opinion from a law firm based on such incomplete and unreliable data is functionally worthless. Worse, it creates a dangerous false sense of security, encouraging a company to proceed with a product launch that leads directly into a minefield of infringement lawsuits.35

Case Studies in Conflict: When Patent Disputes Delay or Derail

The real-world consequences of patent disputes in the pharmaceutical industry are stark and severe. These are not theoretical risks; they are battles that play out in courtrooms and boardrooms, with billions of dollars on the line.

- Gilead vs. Merck (Sovaldi): In one of the largest patent infringement verdicts in U.S. history, a federal jury ordered Gilead Sciences to pay $2.54 billion in royalties to Merck for infringing on patents related to the development of its blockbuster hepatitis C drugs, Sovaldi and Harvoni. The case revolved around the core chemical compound, sofosbuvir. The sheer size of the verdict underscores the immense value locked within a single composition of matter patent and the catastrophic financial consequences of being found to infringe.

- Janssen vs. Apotex (Invega Sustenna): The litigation surrounding Janssen’s long-acting injectable antipsychotic, Invega Sustenna, highlights the nuances that define modern patent battles. The dispute did not just involve the compound itself, but complex claims related to the specific dosage regimen—an essential element of the patent that a generic company, Apotex, was accused of inducing physicians to infringe. The case went through multiple rounds of appeals, demonstrating the legal complexity of method-of-use and dosage patents. Parsing these intricate claims requires a level of detail and analysis far beyond what a generalist search tool can support.

- Delayed Generic Entry: The most common consequence of patent disputes is the delay of lower-cost generic drugs, a strategy that costs consumers and healthcare systems billions of dollars annually.22 Brand-name companies strategically build “patent thickets” and use litigation, including the 30-month stay, to extend their monopolies for as long as possible.22 Generic companies, in turn, must decide whether to launch “at risk” while litigation is pending, facing massive potential damages if they lose.57 Navigating this complex timeline of patent expirations, litigation, and potential settlements requires precise, reliable, and integrated data that connects patents to their regulatory and legal context.

These cases demonstrate that the details that decide billion-dollar outcomes—a specific crystalline form of a molecule, a precise dosage regimen, a particular amino acid sequence—are exactly the kinds of details that Google Patents is ill-equipped to find, analyze, or place in the proper strategic context.

The Financial Fallout: The Staggering Cost of Litigation

Even if a company ultimately wins a patent dispute, the cost of the fight itself can be crippling. The financial risk of relying on flawed patent intelligence is not just the potential for a massive damages award, but also the certainty of exorbitant legal fees.

According to a comprehensive survey by the American Intellectual Property Law Association (AIPLA), the cost of patent litigation is immense. For a pharmaceutical patent infringement case where more than $25 million is at stake—a common scenario for a successful drug—the financial commitment is staggering :

- Median cost through the end of discovery: $3.0 million

- Median total cost through trial and appeal: $5.5 million

Even for cases with smaller amounts at risk, the costs are substantial, typically running from several hundred thousand to over two million dollars.12 These figures represent direct, out-of-pocket expenses for legal fees, expert witnesses, and court costs. They do not even begin to account for the massive indirect costs, such as the diversion of time and attention from key executives and scientists, the disruption to business operations, and the negative impact on stock price and investor confidence.

The cost of a single, avoidable lawsuit dwarfs the annual subscription cost of a premium, professional patent intelligence platform by orders of magnitude. This stark financial reality exposes the folly of the “free tool” mindset. It is a textbook example of being “penny wise and pound foolish.”

This dynamic creates a “risk inversion.” The user believes they are mitigating cost by choosing a free tool. In reality, they are trading a small, known, and fixed cost—the subscription fee for a professional platform—for a massive, unknown, and potentially catastrophic risk—the consequences of a bad decision based on flawed data. A proper risk management perspective would always choose the fixed, manageable cost of reliable intelligence over the unquantifiable, potentially company-ending risk of avoidable litigation. The perceived cost saving of using Google Patents is an illusion that masks a dramatic and unacceptable increase in overall business and financial risk.

Table 3: The Cost of Conflict: Median U.S. Patent Litigation Costs

| Amount at Risk | Median Cost Through Discovery (USD) | Median Total Cost Through End of Trial & Appeal (USD) | |

| Less than $1 Million | $250,000 | $500,000 | |

| $1 – $10 Million | $600,000 | $1,500,000 | |

| $10 – $25 Million | $1,225,000 | $2,700,000 | |

| More than $25 Million | $2,375,000 | $4,000,000 – $5,500,000+ | |

| Source: Adapted from AIPLA Report of the Economic Survey data and other industry analyses.12 |

Part VII: The “Why” – Deconstructing Google’s Motives and Model

To complete our analysis, we must ask a crucial question: why does Google Patents have these significant limitations? It is not because Google’s engineers are incompetent or because the company lacks resources. The deficiencies in Google Patents are not accidental; they are the logical and predictable outcome of a tool built by a data and advertising company for its own purposes. The platform’s design philosophy, its data acquisition model, and Google’s public stance on intellectual property are all fundamentally misaligned with the high-stakes, high-precision needs of the pharmaceutical industry. A pharmaceutical company using Google Patents is, in effect, using a tool built by its philosophical and strategic opponent.

A Tool for Data Science, Not Legal Diligence

One of the primary, though less visible, purposes of Google’s massive patent dataset is to serve as a training ground for its core business: artificial intelligence and data science. Google makes its patent data, including bibliographic information, full text, and even machine-generated “embedding vectors,” available for large-scale statistical analysis via its BigQuery cloud platform.61

This reveals a key motive. The global patent corpus is one of the largest, most structured, and most technically dense collections of human knowledge ever assembled. It is an invaluable resource for training machine learning models for tasks like text classification, natural language processing, and semantic analysis—all of which are central to Google’s primary business of search and AI.61 Google’s own patent portfolio is heavily weighted toward these areas, with thousands of patents on data processing, machine learning algorithms, and targeted advertising.67

The requirements for building a dataset to train an AI model are very different from the requirements for a database used for legal due diligence. For AI training, massive scale is paramount, and a certain level of “noise” or inaccuracy in the data is often acceptable and can even make the model more robust. The goal is to identify broad patterns and statistical relationships—what data scientists call “patent landscaping”. For legal diligence, however, perfect accuracy, timeliness, and the legal status of a single document are what matter. This difference in purpose explains many of Google Patents’ flaws. The platform is optimized for large-scale data analysis, not for the meticulous, high-stakes legal analysis required by the pharmaceutical industry.

A History of Hostility: Google’s Stance on the Patent System

Beyond its technical motivations, it is crucial to understand that Google is not a neutral party in the world of intellectual property. The company has a long and public history of advocating for a weaker U.S. patent system, a position that often puts it at odds with IP-centric industries like pharmaceuticals.72

Google’s core business model, built on open-source software like Android and the free flow of information via its search engine, benefits from a patent system where it is more difficult for innovators, particularly smaller ones, to obtain and enforce strong patents that could block its platforms.73 The company has been a vocal critic of so-called “patent trolls” (Non-Practicing Entities) and has lobbied Congress extensively for reforms that make it easier and cheaper to challenge the validity of issued patents.72 Google was a key supporter of the America Invents Act (AIA) of 2011, which created the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB), an administrative body within the USPTO where patents can be challenged with a lower burden of proof and without the protections of a federal court.

Google’s own patent strategy has historically been defensive. Its acquisition of the massive Motorola Mobility patent portfolio for over $12 billion was not primarily to monetize those inventions, but to create a defensive shield to protect its Android ecosystem from lawsuits by competitors like Apple and Microsoft.

This philosophical and strategic context is vital. Google is not incentivized to build a patent platform that caters to the needs of strong patent holders like pharmaceutical companies. Its interests align more with creating a tool that emphasizes broad access to prior art and facilitates challenges to patent validity. This explains the focus on including NPL and the lack of features that would help a patent owner manage and enforce their portfolio.

This creates a fundamental, irreconcilable misalignment of business models. The pharmaceutical business model depends on creating a small number of highly valuable, strongly protected patents and defending them for a limited time to recoup massive R&D investments.2 Pharma companies need tools that prioritize precision, legal reliability, and data that proves the validity and enforceability of their assets. They need a digital vault.

Google’s business model, in contrast, is based on aggregating data at a massive scale and using it for AI and advertising.66 Its IP strategy is largely defensive and its political stance favors a weaker patent system. It has built a public library. The deficiencies in Google Patents are, therefore, not bugs; they are features of a system designed with a completely different set of goals and philosophies regarding intellectual property.

Part VIII: Conclusion – From Reactive Searching to Proactive Intelligence

The appeal of Google Patents is a powerful illusion. It offers a world of patent information through a familiar, user-friendly interface at no cost, creating a compelling “Siren’s Call” for businesses and researchers alike. However, for professionals in the high-stakes pharmaceutical industry, this allure is a dangerous trap. Our exhaustive analysis demonstrates that relying on this generalist tool for the specialized, mission-critical work of drug patent analysis is not a viable cost-saving measure but a significant strategic liability.

The platform’s foundation is cracked. Its data suffers from critical integrity failures, including significant update lags that leave users blind to recent threats, jurisdictional gaps that undermine the premise of a “global” search, and rampant inaccuracies in the legal status and ownership data that form the basis of any sound analysis. These are not minor inconveniences; they are systemic flaws that contaminate every decision made using the platform.

Functionally, Google Patents is a blunted instrument. It is fundamentally blind to the primary languages of pharmaceutical innovation: chemical structures and biologic sequences. Its inability to perform these essential searches renders it useless for a vast and growing portion of the industry. Even its text-based search is a poor substitute for the precision and power of professional-grade tools, leaving users to drown in a sea of irrelevant noise.

These deficiencies multiply business risk. Using Google Patents for a freedom-to-operate analysis is a recipe for disaster, creating a false sense of security that can lead a company to launch a billion-dollar product directly into a minefield of infringement litigation. The cost of a single, avoidable lawsuit—potentially millions of dollars in legal fees alone—dwarfs the cost of a professional intelligence platform, exposing the “free tool” mindset as a classic case of being penny wise and pound foolish.

Ultimately, the shortcomings of Google Patents are a direct result of a fundamental misalignment between its purpose and the needs of the pharmaceutical industry. It is a tool built by a data and advertising company, for its own data science and policy goals, not a solution built by IP experts for pharmaceutical professionals. Pharma needs a scalpel; Google has built a bulldozer. Pharma needs a secure vault for its most valuable assets; Google has built a public library.

The path forward for pharmaceutical business leaders, IP strategists, and R&D teams is clear. The mindset must shift from reactive “searching” to proactive “intelligence.” This requires moving beyond the illusion of free tools and making a strategic investment in a professional, specialized intelligence platform. Services like DrugPatentWatch are not mere search engines; they are integrated systems designed to connect patent data with the critical regulatory, litigation, and commercial context that gives it meaning. They provide the curated, reliable data and the advanced analytical tools necessary to transform information into a true competitive advantage.

In an industry where a single data point can be worth billions and a single mistake can be catastrophic, relying on a tool that disclaims the accuracy of its own data is not a strategy. It is a gamble you cannot afford to lose.

Key Takeaways

- Fundamental Mismatch: Google Patents is designed for mass access and data science, a philosophy that is fundamentally misaligned with the pharmaceutical industry’s need for precision, timeliness, and legal reliability.

- Critical Data Deficiencies: The platform suffers from severe data integrity issues, including significant update lags, incomplete global coverage, and inaccurate legal status information, making it unsuitable for high-stakes decisions.

- Functional Blindness: The complete lack of chemical structure and biologic sequence search capabilities renders Google Patents functionally useless for analyzing the core inventions of most modern small-molecule and biologic drugs.

- The Illusion of Cost Savings: Using a “free” tool creates a “risk inversion,” where a small, fixed cost (a professional subscription) is traded for a massive, unquantifiable risk of multi-million-dollar litigation and derailed product launches.

- The Need for Integrated Intelligence: Professional platforms like DrugPatentWatch provide value not just through better data, but by integrating patent information with the essential regulatory (FDA), litigation, and clinical context needed to perform true strategic analysis.

- Strategic Imperative: Investing in a professional-grade pharmaceutical intelligence platform is not an operational expense; it is a critical investment in risk mitigation and competitive advantage.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. Isn’t Google Patents “good enough” for a preliminary or “quick and dirty” search?

While it can be tempting to use Google Patents for a quick initial look, doing so creates significant risk. A preliminary search that misses a key patent due to data lags or functional blindness can set an entire R&D project on the wrong path from day one. Furthermore, the “illusion of simplicity” can create a false sense of confidence, leading teams to underestimate the complexity of the patent landscape. A flawed preliminary search is often worse than no search at all, as it provides a misleading foundation for subsequent, more critical work.

2. If Google’s data comes from the same patent offices, why is it less reliable than a paid service?

The issue is not the ultimate source, but the process of acquiring, cleaning, and integrating the data. Google relies on a largely automated, mass-scale ingestion process that is prone to lags and reproduces the errors and inconsistencies of the source data.5 Professional services invest heavily in “human-in-the-loop” curation. This involves subject matter experts who clean and standardize messy data (like assignee names), manually index non-textual information (like chemical structures), and integrate the patent data with other critical datasets (like FDA regulatory information and litigation records). This curation process is what transforms raw, unreliable data into trustworthy, actionable intelligence.34

3. My company has a tight budget. How can I justify the high cost of a professional patent intelligence platform?

The justification lies in reframing the decision from an expense to a form of insurance against catastrophic risk. As this report details, the median cost to defend a high-stakes pharmaceutical patent lawsuit can exceed $5.5 million. The cost of a derailed drug program can run into the hundreds of millions. Compared to these potential losses, the annual subscription fee for a professional platform is a rounding error. It is a fixed, predictable investment in risk mitigation. Relying on a free, unreliable tool to save a few thousand dollars is a classic example of being “penny wise and pound foolish,” as it exposes the company to immense and avoidable financial and strategic risks.

4. Can’t I just supplement Google Patents with searches on the USPTO or Espacenet websites to fill the gaps?

While official patent office websites like the USPTO’s and EPO’s Espacenet are the sources of record, using them to manually supplement a Google Patents search is incredibly inefficient and still leaves critical gaps. This approach creates a fragmented, disconnected workflow where information has to be manually transferred and cross-referenced, a process that is both time-consuming and highly prone to error. More importantly, these sites still lack the crucial integration with regulatory, litigation, and clinical trial data that professional platforms provide. You might be able to verify a single patent’s legal status, but you still won’t see how it connects to a specific drug’s market exclusivity or its litigation history without a dedicated intelligence platform.

5. With the rise of AI, won’t Google’s search capabilities automatically improve to include things like structure searching soon?

While Google is a leader in AI, solving the problem of perfect chemical structure and biologic sequence recognition from patent documents is incredibly complex. Even if Google were to implement a “good enough” AI-based solution, it would likely still lack the precision and reliability required for legal due diligence. More fundamentally, as this report argues, the problem isn’t just about search features. It’s about the entire data ecosystem. Google’s core business model is not aligned with making the massive, ongoing investment in data curation and integration with specialized pharmaceutical datasets (like FDA regulatory data) that is necessary to build a truly professional-grade intelligence platform for this industry. They are more likely to continue using the patent corpus as a training set for their broader AI ambitions rather than building a bespoke solution for the unique needs of pharma.

References

- A Business Professional’s Guide to Drug Patent Searching – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-basics-of-drug-patent-searching/

- The Role of Patents in the Pharmaceutical Sector – Minesoft, accessed August 3, 2025, https://minesoft.com/the-role-of-patents-in-the-pharmaceutical-sector/

- What is Google Patents Search Guide – GHB Intellect, accessed August 3, 2025, https://ghbintellect.com/what-is-google-patents-search-guide/

- Google Patents – Wikipedia, accessed August 3, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Google_Patents

- Google Patents: Why It’s a Risky Tool for Finding Drug Patents – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/google-patents-why-its-a-risky-tool-for-finding-drug-patents/

- Patent Research and Analysis Google Patents – Intellectual Property …, accessed August 3, 2025, https://ipo.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/2019-10-Patent-Searching-Google-Patents.pdf

- Coverage – Google Help, accessed August 3, 2025, https://support.google.com/faqs/answer/7049585?hl=en

- Google Patents Search – A Definitive Guide by GreyB, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.greyb.com/blog/google-patents-search-guide/

- How to Use Google Patents for Effective Patent Searches, accessed August 3, 2025, https://patentpc.com/blog/how-to-use-google-patents-for-effective-patent-searches

- Google Patent Search – An Overview, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.kaufholdpatentgroup.com/google-patent-search/

- “Usability testing of Google Patents and Patent Public Search with undergraduate engineering students” by Graham Sherriff and Molly Rogers – Clemson OPEN, accessed August 3, 2025, https://open.clemson.edu/jptrca/vol33/iss1/1/

- How Much Does a Drug Patent Cost? A Comprehensive Guide to Pharmaceutical Patent Expenses – DrugPatentWatch – Transform Data into Market Domination, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/how-much-does-a-drug-patent-cost-a-comprehensive-guide-to-pharmaceutical-patent-expenses/

- IP Explained: Why patents are so critical to biopharmaceutical innovation – PhRMA, accessed August 3, 2025, https://phrma.org/blog/ip-explained-why-patents-are-so-critical-to-biopharmaceutical-innovation

- Strategic Patenting by Pharmaceutical Companies – Should Competition Law Intervene? – PMC, accessed August 3, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7592140/

- Want to Lower Drug Prices? Reform the U.S. Patent System | Kaiser Permanente, accessed August 3, 2025, https://about.kaiserpermanente.org/news/want-to-lower-drug-prices-reform-the-us-patent-system

- Patent protection strategies – PMC, accessed August 3, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3146086/

- Optimizing Your Drug Patent Strategy: A Comprehensive Guide for Pharmaceutical Companies – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/optimizing-your-drug-patent-strategy-a-comprehensive-guide-for-pharmaceutical-companies/

- The Role of Patents and Regulatory Exclusivities in Drug Pricing | Congress.gov, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/R46679

- How Patent Law Affects the Pharmaceutical Industry Under U.S. Health Laws – PatentPC, accessed August 3, 2025, https://patentpc.com/blog/how-patent-law-affects-the-pharmaceutical-industry-under-u-s-health-laws

- Pharmaceutical Patent Challenges: Company Strategies and Litigation Outcomes, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.1162/AJHE_a_00066

- STAT quotes Sherkow on pharmaceutical patents – College of Law, accessed August 3, 2025, https://law.illinois.edu/stat-quotes-sherkow-on-pharmaceutical-patents/

- Strategies That Delay Market Entry of Generic Drugs – Commonwealth Fund, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/journal-article/2017/sep/strategies-delay-market-entry-generic-drugs

- Generic Drug Entry Prior to Patent Expiration: An FTC Study, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.ftc.gov/sites/default/files/documents/reports/generic-drug-entry-prior-patent-expiration-ftc-study/genericdrugstudy_0.pdf

- FTC Challenges More Than 100 Patents as Improperly Listed in the FDA’s Orange Book, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/news/press-releases/2023/11/ftc-challenges-more-100-patents-improperly-listed-fdas-orange-book

- Patent Lists – FDA Purple Book, accessed August 3, 2025, https://purplebooksearch.fda.gov/patent-list

- Generic Drug Entry Timeline: Predicting Market Dynamics After Patent Loss, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/generic-drug-entry-timeline-predicting-market-dynamics-after-patent-loss/

- Raising the Barriers to Access to Medicines in the Developing World – The Relentless Push for Data Exclusivity – PubMed Central, accessed August 3, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5347964/

- Pharmaceutical Patents: an overview, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.alacrita.com/blog/pharmaceutical-patents-an-overview

- Google Patent Search vs. USPTO: Which One Should You Use? – Emanus LLC, accessed August 3, 2025, https://emanus.com/google-patent-search-vs-uspto-guide/

- The Hidden Pitfalls of Searching Drug Patents on Google Patents …, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-hidden-pitfalls-of-searching-drug-patents-on-google-patents/

- Limitations of Google Patents Advanced Search for Invalidation: What IP Professionals Need to Know – DEV Community, accessed August 3, 2025, https://dev.to/patentscanai/limitations-of-google-patents-advanced-search-for-invalidation-what-ip-professionals-need-to-know-3ep2

- Using Google Patents to Find Drug Patents? Here’s 15 Reasons Why You Shouldn’t, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/using-google-patents-to-find-drug-patents-heres-15-reasons-why-you-shouldnt/

- US6421675B1 – Search engine – Google Patents, accessed August 3, 2025, https://patents.google.com/patent/US6421675B1/en

- 5 Consequences of Patent Data Errors: The Applicant Name Field, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.lexisnexisip.com/resources/5-consequences-of-patent-data-errors-the-applicant-name-field/

- Data and Decisions: The Risks in Relying on Inaccurate Patent Data – LexisNexis IP, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.lexisnexisip.com/resources/data-and-decisions-the-risks-in-relying-on-inaccurate-patent-data/

- FTC Expands Patent Listing Challenges, Targeting More Than 300 Junk Listings for Diabetes, Weight Loss, Asthma and COPD Drugs, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/news/press-releases/2024/04/ftc-expands-patent-listing-challenges-targeting-more-300-junk-listings-diabetes-weight-loss-asthma

- Chemical Structure Search – Effectual Services, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.effectualservices.com/patent-services/patent-searches/chemical-structure-search/

- CAS SciFinder – Chemical Compound Database, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.cas.org/solutions/cas-scifinder-discovery-platform/cas-scifinder

- Derwent Chemistry Research – Clarivate, accessed August 3, 2025, https://clarivate.com/intellectual-property/patent-intelligence/derwent-chemistry-research/

- Pharmaceutical Patents | ChemX – Minesoft, accessed August 3, 2025, https://minesoft.com/solutions/rd-strategy/minesoft-chem-x/

- Molecule Search Database – Orbit Chemistry – Questel, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.questel.com/patent/ip-intelligence-software/chemistry/

- Conducting a Biopharmaceutical Freedom-to-Operate (FTO) Analysis: Strategies for Efficient and Robust Results – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/conducting-a-biopharmaceutical-freedom-to-operate-fto-analysis-strategies-for-efficient-and-robust-results/

- Search Sequence Listings – WIPO Patentscope, accessed August 3, 2025, https://patentscope.wipo.int/search/en/sequences.jsf

- Our search for a reliable patent intelligence solution ended with …, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/

- www.geneonline.com, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.geneonline.com/pharma-companies-use-patent-landscaping-and-extensions-to-protect-drug-revenue-streams/#:~:text=The%20analysis%20indicates%20that%20patent,market%20exclusivity%2C%20impacting%20revenue%20streams.

- Strategic Imperatives: Leveraging Patent Pending Data for Competitive Advantage in the Pharmaceutical Industry – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/leveraging-patent-pending-data-for-pharmaceuticals/

- The secret to IP success: AI-driven patent search and analysis | Dennemeyer.com, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.dennemeyer.com/ip-blog/news/the-secret-to-ip-success-ai-driven-patent-search-and-analysis/

- Why Successful Research Begins with Better Patent Searching (Part 2), accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.gqlifesciences.com/why-successful-research-begins-with-better-patent-searching-part-2/

- Freedom to Operate (FTO) | Definitive Healthcare, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.definitivehc.com/resources/glossary/freedom-to-operate

- Freedom to Operate FTO Search on Pharmaceutical Formulations – Sagacious Research, accessed August 3, 2025, https://sagaciousresearch.com/blog/freedom-to-operate-fto-search-pharmaceutical-formulations/

- How to Conduct a Drug Patent FTO Search: A Strategic and Tactical Guide to Pharmaceutical Freedom to Operate (FTO) Analysis – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/how-to-conduct-a-drug-patent-fto-search/

- Freedom to Operate: How to Safely Launch Products – UpCounsel, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.upcounsel.com/freedom-to-operate

- Gilead to pay Merck $2.54B in largest-ever patent infringement case – MedCity News, accessed August 3, 2025, https://medcitynews.com/2016/12/gilead-merck-2-54b-patent-infringement-case/

- Pharma Patent Case Round-Up | Lenczner Slaght, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.litigate.com/pharma-patent-case-round-up/pdf

- $52.6 Billion: Extra Cost to Consumers of Add-On Drug Patents – UCLA Anderson Review, accessed August 3, 2025, https://anderson-review.ucla.edu/52-6-billion-extra-cost-to-consumers-of-add-on-drug-patents/

- Strategies that delay or prevent the timely availability of affordable generic drugs in the United States, accessed August 3, 2025, https://ashpublications.org/blood/article/127/11/1398/34989/Strategies-that-delay-or-prevent-the-timely

- Delayed Generic Competition – Cornerstone Research, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.cornerstone.com/insights/cases/delayed-generic-competition/

- NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES NO FREE LAUNCH: AT-RISK ENTRY BY GENERIC DRUG FIRMS Keith M. Drake Robert He Thomas McGuire Alice K. N, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w29131/w29131.pdf

- Managing Drug Patent Litigation Costs – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/managing-drug-patent-litigation-costs/

- The Private Costs of Patent Litigation | Scholarly Commons at Boston University School of Law, accessed August 3, 2025, https://scholarship.law.bu.edu/context/faculty_scholarship/article/2389/viewcontent/The_Private_Costs_of_Patent_Litigation_pub.pdf

- Expanding your patent set with ML and BigQuery | Google Cloud Blog, accessed August 3, 2025, https://cloud.google.com/blog/products/data-analytics/expanding-your-patent-set-with-ml-and-bigquery

- Google Patents Research Data – Marketplace, accessed August 3, 2025, https://console.cloud.google.com/marketplace/product/google_patents_public_datasets/google-patents-research-data

- Google Patents Public Datasets: connecting public, paid, and private patent data, accessed August 3, 2025, https://cloud.google.com/blog/topics/public-datasets/google-patents-public-datasets-connecting-public-paid-and-private-patent-data

- Patent analysis using the Google Patents Public Datasets on BigQuery – GitHub, accessed August 3, 2025, https://github.com/google/patents-public-data

- Programmatic Patent Searches Using Google’s BigQuery & Public Patent Data, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.aipla.org/list/innovate-articles/programmatic-patent-searches-using-google-s-bigquery-public-patent-data

- US11907860B2 – Targeted data acquisition for model training – Google Patents, accessed August 3, 2025, https://patents.google.com/patent/US11907860/en

- Google’s First Semantic Search Invention was Patented in 1999, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.seobythesea.com/2014/09/google-first-semantic-search-invention-patented-1999/

- Google U.S. Patents, Patent Applications and Patent Search – Justia Patents Search, accessed August 3, 2025, https://patents.justia.com/company/google

- US10565620B1 – Audience matching system for serving advertisements to displays – Google Patents, accessed August 3, 2025, https://patents.google.com/patent/US10565620B1/en

- US20190378171A1 – Targeted advertisement system – Google Patents, accessed August 3, 2025, https://patents.google.com/patent/US20190378171A1/en