Executive Summary

In the highly contentious arena of pharmaceutical pricing and innovation, the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO), in collaboration with the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), has released its “Drug Patent and Exclusivity Study.” This report serves as a pivotal, data-driven intervention in a debate often characterized by conflicting narratives and statistical claims. Initiated at the request of Congress to provide an independent assessment of drug patenting trends, the study examines the intellectual property and regulatory landscapes of 25 New Drug Applications (NDAs) to measure the actual period of market exclusivity enjoyed by innovator companies before the entry of generic competition.

The study’s central conclusion is that a simple quantification of patents associated with a drug is an imprecise and potentially misleading metric for determining market exclusivity. The analysis found no clear correlation between the number of patents listed in the FDA’s Orange Book and the timing of generic market entry. For the products studied that faced generic competition, the average period of market exclusivity was 11.4 years—a figure substantially shorter than the statutory 20-year patent term and one that challenges narratives of indefinite monopolies. The report frames the practice of obtaining “follow-on” patents for improvements to existing drugs as a normal feature of the innovation lifecycle, common across all technology sectors, rather than an inherently abusive practice.

However, the USPTO’s findings exist within a complex and increasingly fractured regulatory environment. A significant tension arises when contrasting the study’s conclusions with the recent, aggressive enforcement actions undertaken by the Federal Trade Commission (FTC). While the USPTO study appears to validate certain industry patenting practices, the FTC has simultaneously launched a campaign against what it deems “improper” or “junk” patent listings in the Orange Book, viewing them as unfair methods of competition designed to illegally stifle generic entry. This divergence reflects the different statutory mandates of the agencies: the USPTO assesses patentability, while the FTC scrutinizes competitive conduct.

This report provides a comprehensive analysis of the USPTO’s study, placing its methodology and findings in the broader context of the “patent thicket” and “evergreening” debates. It deconstructs the intricate interplay between patent law, FDA regulatory exclusivities, and the foundational Hatch-Waxman Act. Furthermore, it critically examines the contrasting approaches of the USPTO and the FTC, exploring the profound implications of this regulatory dissonance for the pharmaceutical industry. The analysis concludes that stakeholders are entering an era of heightened scrutiny, where patent and litigation strategies must be calibrated not only to the standards of patent law but also to the evolving interpretations of antitrust and competition law. For both innovator and generic firms, navigating this landscape requires a sophisticated, risk-aware approach to intellectual property management, litigation, and regulatory compliance.

I. The USPTO’s Empirical Intervention: Deconstructing the Drug Patent and Exclusivity Study

The release of the USPTO’s Drug Patent and Exclusivity Study marks a significant, government-led effort to inject empirical data into the contentious discourse surrounding pharmaceutical patents, drug pricing, and market competition. The report does not purport to be a comprehensive economic analysis of the entire industry; rather, it presents itself as a foundational methodology for assessing the real-world duration of market exclusivity for a select group of drugs, directly addressing and often refuting the metrics used in prevailing critiques of the patent system.

A. Genesis and Mandate: The Tillis Request and the Call for Data-Driven Policy

The impetus for the USPTO’s study was a series of letters in January and April 2022 from Senator Thom Tillis (R-NC), the lead Republican of the Senate Intellectual Property Subcommittee.1 The Senator requested that the USPTO conduct an independent, fact-based analysis to assess the validity of claims and data being promulgated by what he termed “anti-patent activists”.1 These groups, most notably the Initiative for Medicines, Access & Knowledge (I-MAK), have published influential reports arguing that pharmaceutical companies systematically abuse the patent system to create “patent thickets” and engage in “evergreening” to extend drug monopolies for decades, thereby keeping prices artificially high.1

Senator Tillis’s request framed the study’s core mission: to serve as an empirical check on these narratives and to ensure that future policymaking is based on accurate and transparent data.2 Consequently, the study’s stated objective is not to offer broad policy recommendations but “to provide a baseline approach that researchers and policymakers can use in future analysis”.3 Its focus is narrowly tailored to examining the actual number of years from the approval of a New Drug Application (NDA) until the launch of the first generic competitor, thereby providing a real-world measure of market exclusivity.7 This origin story is crucial, as it positions the report less as a holistic market survey and more as a targeted methodological critique of existing, often-cited analyses.

B. Anatomy of the Study: A Deep Dive into Methodology, Drug Selection, and Data Sources

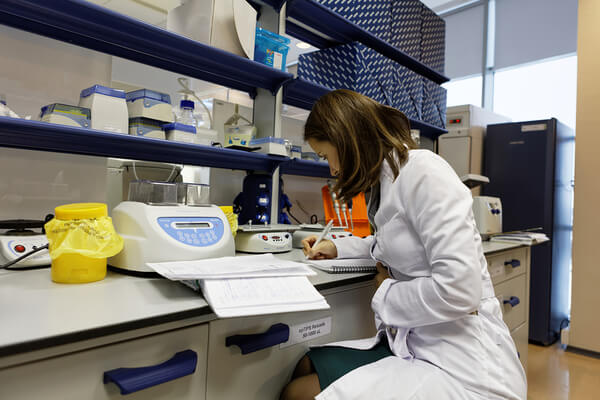

To fulfill its mandate, the USPTO, working in conjunction with the FDA, developed a specific and deliberate methodology for its analysis.2

The study’s sample consisted of 25 NDAs, which represented 13 distinct active ingredients or combinations thereof.2 The selection of these drugs was not random but was purposively designed to include products that were central to the ongoing policy debate. The criteria for inclusion were multifaceted, encompassing:

- Top-grossing products by revenue in 2017, such as apixaban (ELIQUIS), lenalidomide (REVLIMID), and pregabalin (LYRICA).2

- Most-prescribed branded products in 2017, including atorvastatin (LIPITOR), amlodipine besylate (NORVASC), and albuterol sulfate (VENTOLIN HFA).2

- Drugs that were the subject of reports cited in Senator Tillis’s letters, ensuring the study directly addressed the products at the center of the controversy.2

The timeframe for analysis was set between 2005 and 2018, aligning with the period covered by external databases like the University of California College of the Law, San Francisco (UC Law SF) Evergreen Drug Patent Database.5 For each selected NDA, the USPTO and FDA compiled a detailed timeline using official sources, including USPTO patent databases and archived editions of the FDA’s Orange Book.2 The data points collected for each product included all Orange Book-listed patents and FDA-granted exclusivities, NDA approval dates, and the actual launch date of the first generic competitor, if one had occurred by September 18, 2023.7

A critical aspect of the methodology was the USPTO’s independent calculation of patent expiration dates. Rather than relying on the dates submitted by the NDA holder to the FDA, the USPTO determined the projected expiration by accounting for any patent term adjustments (PTA), patent term extensions (PTE), and the effect of any terminal disclaimers.6

The study’s methodology also involved several deliberate scope limitations that are fundamental to interpreting its conclusions. First, it exclusively considered patents that were listed in the FDA’s Orange Book, arguing that “only patents listed in the Orange Book can affect the timing of FDA approval of a generic drug” under the Hatch-Waxman Act.8 Second, the study explicitly excluded pending and abandoned patent applications from its analysis. The report asserts that because these applications do not result in granted, enforceable patent rights, they “do not pose a barrier to competition” and their inclusion is not a “meaningful metric”.1 These two choices represent a direct methodological challenge to the work of critics who often count all patents—listed or unlisted, granted or pending—associated with a drug to arrive at much larger numbers.

C. Headline Findings: The Disconnect Between Patent Volume and Market Exclusivity

The most significant conclusion of the USPTO study is that raw patent counts are a poor proxy for the duration of a drug’s market exclusivity. The report states unequivocally that “simply quantifying raw numbers of patents and exclusivities is an imprecise way to measure the intellectual property landscape of a drug product”.5 This is because the scope and strategic importance of each patent can vary dramatically; a single, broad composition-of-matter patent may provide more robust protection than a dozen narrower patents on minor formulations.5

The data gathered from the 25 NDAs demonstrated no clear correlation between the number of Orange Book-listed patents and the actual timing of generic entry.1 For the products studied, the number of listed patents ranged from one to as many as 27, yet this variation did not predict the length of market protection.2

The report’s case studies vividly illustrate this disconnect. Several drugs with numerous patents saw generic competition well before all of those patents expired. For example, generic versions of LIPITOR and REVLIMID were launched following settlement agreements, while a generic for LYRICA CR entered after a court judgment of non-infringement.1 These instances show that litigation and business strategy, rather than the sheer number of patents, often dictate the timeline of competition. Conversely, the study also identified cases such as VENTOLIN HFA and AMBIEN where no generic competitor had launched even after the expiration of Orange Book-listed patents, suggesting that factors beyond patent protection—such as manufacturing complexity or market economics—can also influence generic entry.2

D. The Nuances of Exclusivity: Analyzing the 3-to-16-Year Reality vs. the 20-Year Patent Term Myth

By focusing on the tangible event of a first generic launch, the study provides a concrete measure of market exclusivity that directly counters the narrative that pharmaceutical companies routinely secure monopolies lasting 20 years or more.

For the 13 NDAs in the study that had faced generic competition, the actual period of market exclusivity—measured from the date of NDA approval to the date of the first generic launch—ranged widely, from a low of approximately 3 years to a high of 16.4 years.2

The average length of market exclusivity across these 13 products was just 11.4 years.1 This figure is a powerful counterpoint to claims of ever-extending monopolies and aligns with findings from other academic studies, which have reported similar averages of 11.3 to 13 years for new molecular entities.8 The fact that not one of the products studied, even those with dozens of patents, achieved market exclusivity for the full 20-year patent term is a central pillar of the report’s findings.1

The report further emphasizes that patent expiration dates themselves are not reliable predictors of generic launch dates.2 Generic entry can occur earlier through successful patent challenges or settlement agreements, or it can be delayed by other factors. This variability underscores the complexity of the pharmaceutical market, where exclusivity is shaped by a dynamic interplay of patent law, FDA regulations, litigation outcomes, and commercial decisions.3 The wide range of outcomes observed in the study suggests that while the narrative of systemic patent abuse leading to indefinite monopolies may be overstated on average, the market experience of individual drugs can vary dramatically. Therefore, any proposed policy solutions must account for this complexity rather than relying on a single, aggregated average.

E. Acknowledged Limitations and Avenues for Future Research

The USPTO is transparent about the study’s limitations, which are essential for properly contextualizing its findings. The report explicitly states that its small sample size of 25 NDAs “limits generalizations that can be drawn from the study” and that the data is insufficient to produce “generalized findings concerning all Orange Book listed patents and the timing of marketing of all generic drugs”.6

Furthermore, the study’s scope was intentionally narrow. It did not address the price of the drugs, the impact of generic entry on market share, or the presence of non-IP barriers to competition, such as manufacturing challenges or distribution contracts.6 This self-acknowledged narrow focus reinforces the understanding that the report is primarily a methodological intervention. Its main purpose is not to declare the patent system functionally perfect, but to argue that the specific metrics and methods used by some critics—particularly the practice of simple patent counting without regard to context or enforceability—are flawed and lead to inaccurate conclusions. The study thus serves as a call for more nuanced, data-driven research while providing a “baseline approach” for how such research might be conducted.7

II. The Central Debate: Re-evaluating “Evergreening” and “Patent Thickets”

The USPTO study’s findings land directly in the middle of a long-standing and deeply polarized debate over the legitimacy of certain pharmaceutical patenting strategies. The terms “evergreening” and “patent thickets” have become central to this conflict, representing either legitimate, pro-innovation lifecycle management or anticompetitive abuse, depending on the perspective. The USPTO report provides significant data that supports the former view, but a comprehensive analysis requires juxtaposing its conclusions with the extensive evidence and alternative interpretations presented by critics.

A. The Pro-Innovation Argument: Follow-on Patents as Legitimate Lifecycle Management

From the perspective of innovator companies and patent system proponents, the accumulation of multiple patents on a single drug product is a natural and beneficial outcome of ongoing research and development. The USPTO study lends credence to this view by framing the issuance of “follow-on patents” as a standard part of the “cycle of innovation,” wherein inventors build upon existing knowledge to create improvements.5 This practice, the report notes, is not unique to the pharmaceutical industry but is a common business practice in any sector involving complex technologies, from smartphones to software.1

These follow-on patents are not granted for trivial changes; they must meet the same statutory requirements for patentability—novelty, utility, and non-obviousness—as the original invention.6 They often cover genuine, clinically relevant improvements that can benefit patients, such as:

- New Dosage Forms: Developing a once-daily extended-release formulation, as was the case with LYRICA, can improve patient adherence and quality of life.6

- New Indications: Discovering that a drug is effective for treating a different disease, as with IMBRUVICA, expands its therapeutic value.6

- Improved Delivery Devices: Creating a more efficient or user-friendly inhaler, as with VENTOLIN, can enhance the drug’s safety and efficacy.6

A crucial point emphasized by the USPTO study and its supporters is that a follow-on patent does not extend the patent term of the original invention. Once the initial patent on a drug’s active ingredient expires, that core technology enters the public domain, and generic manufacturers are free to produce it.1 The new patent only protects the specific, novel improvement. This means a generic company can market a copy of the original version of the drug; it simply cannot copy the later, patented improvement.1 The case of LIPITOR, where a generic competitor launched while some of the drug’s later, follow-on patents were still in force, is frequently cited as empirical proof of this principle.1

B. The Anti-Competition Counterpoint: Case Studies in Strategic Obstruction

Critics of the pharmaceutical industry offer a starkly different interpretation. They define “evergreening” as a deliberate corporate strategy to artificially extend a drug’s monopoly by obtaining secondary patents on slight modifications that offer little to no additional therapeutic benefit.9 The goal, from this perspective, is not primarily patient benefit but economic advantage.9 Empirical analyses from this viewpoint suggest the practice is pervasive; one widely cited study by Professor Robin Feldman found that between 2005 and 2015, 78% of drugs associated with new patents were existing medicines, not new chemical entities.12

This strategy often culminates in the creation of a “patent thicket”—a dense, overlapping web of patents surrounding a single product.15 The strategic purpose of a thicket is not necessarily to win every potential infringement lawsuit, but to make the prospect of litigation so complex, protracted, and expensive that it deters generic and biosimilar companies from even attempting to enter the market.17 A generic manufacturer must successfully invalidate or prove non-infringement for

every patent asserted against it to launch its product, a daunting and costly proposition.15 The economic impact of this alleged strategy is immense, with critics estimating it costs the U.S. healthcare system billions of dollars annually in delayed access to more affordable medicines.17

Several high-profile drugs serve as archetypal case studies for this anti-competition argument.

| Drug (Innovator) | Primary Patent Subject & Expiration | Total Patents/Applications Cited by Critics | Key Secondary Patent Types | Use of Terminal Disclaimers | Actual/Projected Competitor Entry (U.S.) | Competitor Entry (EU) |

| Humira (AbbVie) | Active Ingredient (adalimumab); Expired 2016 | 136+ patents; 247+ applications 15 | Formulations (single & double concentration), indications, purity levels, methods of treatment 18 | Extensive; 436 cited in one analysis 24 | January 2023 | October 2018 |

| Enbrel (Amgen) | Active Ingredient (etanercept); Expired 2012 | 68+ patents 25 | Manufacturing processes, formulations, methods of use, administration devices 25 | Yes | Projected 2029 | 2016 |

| Revlimid (Celgene) | Active Ingredient (lenalidomide); Expired 2019 | 70+ patents 17 | Polymorphs, methods of use, risk evaluation and mitigation strategies (REMS) 2 | Yes; 18 cited in one analysis 26 | March 2022 (limited volume) | February 2022 |

| Keytruda (Merck) | Active Ingredient (pembrolizumab); Expires ~2028 | 129+ patents sought 17 | Subcutaneous injection method, combination therapies, new indications 17 | Yes | Projected ~2028 | N/A (Biosimilars in development) |

Table 3: Anatomy of a Patent Thicket – Comparative Case Studies. This table synthesizes data from multiple sources to illustrate the characteristics of patent portfolios for several blockbuster drugs often cited in the patent thicket debate.15

The case of AbbVie’s Humira is particularly illustrative. Despite its primary patent expiring in 2016, AbbVie constructed a formidable thicket of over 130 patents, 89% of which were filed after the drug was first approved by the FDA.23 This strategy successfully delayed the entry of biosimilar competitors in the U.S. until 2023, more than four years after they became available in Europe, where the patent landscape is less dense.23 Critics allege that many of these patents were duplicative and designed solely to create an insurmountable litigation barrier.15

C. Synthesizing the Evidence: A Methodological Divide

At first glance, the USPTO study’s conclusion that patent counts do not correlate with exclusivity seems to directly refute the patent thicket argument. However, a deeper analysis reveals that the two sides are not just disagreeing on the facts; they are fundamentally asking different questions and measuring different phenomena. The core of the conflict lies in the definition of competitive “harm.”

The USPTO study defines harm as an actual, measured extension of market exclusivity. Its methodology is designed to test the hypothesis that more patents lead to a longer monopoly period, and it finds this is not systematically true.1 From this perspective, if a drug with 27 patents ultimately has 12 years of exclusivity, the system has worked as intended.

Critics, however, define harm as the in terrorem effect of the thicket itself—the creation of a litigation minefield that deters or delays potential competitors from challenging the innovator in the first place.15 The harm is the chilling of competition and the immense legal costs imposed on challengers, which can delay generic entry even if the final exclusivity period does not exceed statutory limits. The USPTO study was not designed to measure this deterrent effect or the transaction costs of navigating a patent thicket.

This methodological divide explains how both sides can claim to be supported by evidence. The USPTO did not directly analyze the datasets of its critics but instead created its own, implicitly arguing that its “baseline approach” is the correct way to measure the IP landscape.7 This leaves the central policy question unresolved: is the process of building a dense patent portfolio, in and of itself, an anticompetitive act, regardless of the final market outcome?

| Claim/Metric | Critic’s Assertion (e.g., I-MAK) | USPTO Study Finding | Analytical Nuance / Methodological Difference |

| Correlation of Patent Count to Generic Entry | High patent counts (“thickets”) are a primary strategy to delay generic entry for decades. | No clear correlation found between the number of Orange Book patents and the timing of generic entry.1 | Critics count all patents/applications (listed and unlisted). The USPTO study counts only granted, Orange Book-listed patents, which it argues are the only ones legally relevant to the 30-month stay.1 |

| Average Market Exclusivity | Implied to be 20+ years through evergreening, with some drugs having 30+ years of patent protection. | Average actual market exclusivity for drugs with generic entry was 11.4 years; the maximum observed was 16.4 years.1 | The USPTO measures from NDA approval to first generic launch. Critics often measure the total potential patent life from the first patent filing to the last patent’s expiration, which is a different metric. |

| Role of Follow-on Patents (“Evergreening”) | A strategy of filing patents on trivial modifications to illegitimately extend a monopoly.9 | A normal part of the innovation cycle to protect legitimate improvements; does not extend the term of the original patent.1 | The dispute is over the “inventiveness” of the follow-on patents. The USPTO presumes validity if granted. Critics argue many are weak and serve only to create litigation hurdles. |

| Inclusion of Pending/Abandoned Applications | Often included in total patent counts to demonstrate the scale of a company’s patenting strategy.1 | Explicitly excluded, as they are not enforceable and thus not a “meaningful metric” for determining market exclusivity.1 | Critics argue the act of filing, even if later abandoned, creates uncertainty and can be part of a deterrent strategy. The USPTO focuses solely on enforceable legal rights. |

Table 1: USPTO Study Findings vs. Common Criticisms. This table juxtaposes the core claims of patent critics with the empirical findings of the USPTO study, highlighting the key methodological differences that drive their divergent conclusions.

D. The Strategic Role of Terminal Disclaimers

At the technical heart of the patent thicket debate lies the Terminal Disclaimer, a legal instrument that has become a focal point for both corporate strategy and policy reform.28 A terminal disclaimer is filed by a patent applicant to overcome a specific type of rejection from the USPTO known as “nonstatutory double patenting.” This rejection occurs when an applicant files for a patent on an invention that is not identical but is considered an obvious variation of an invention in an earlier, commonly-owned patent.30 By filing a terminal disclaimer, the applicant agrees to “disclaim” the terminal portion of the second patent’s term, ensuring that it expires on the same day as the earlier patent.28

Proponents and the USPTO study itself present this as a routine and pro-competitive mechanism that effectively prevents companies from improperly extending their patent monopoly on a single inventive concept.6 However, critics argue that terminal disclaimers are the very tool that enables the proliferation of patent thickets. The mechanism allows a company to obtain numerous patents on non-inventive variations of a drug. While these patents all expire simultaneously, each one is a legally distinct property right that a generic challenger must individually defeat in court.24 This dramatically increases the cost and complexity of litigation. The Humira patent portfolio, for instance, reportedly includes 436 patents linked by terminal disclaimers.24

The USPTO’s own policy arm has acknowledged the potential for this strategy to be used to deter competition. A proposed (and subsequently withdrawn) rulemaking from the agency sought to change the rules so that if a foundational patent in a terminally disclaimed family were invalidated, all patents tied to it would become unenforceable.2 This internal tension—where the USPTO’s research report presents a benign view of the practice while its policy arm has considered measures to curb it—reveals the deep complexity and contentiousness of the issue. It suggests that while the current system may prevent the extension of the

patent term, it may not prevent the strategic accumulation of patents as a litigation deterrent.

III. The Regulatory Gauntlet: Interplay of Patent Law and FDA Exclusivity

The duration of a drug’s market monopoly in the United States is not determined by a single law or agency but by a complex and often overlapping system of protections administered by both the USPTO and the FDA. Understanding the distinct roles of patents and FDA-granted regulatory exclusivities, and how they interact under the landmark Hatch-Waxman Act, is essential to deciphering the true landscape of pharmaceutical competition.

A. Pillars of Protection: A Detailed Examination of Patents vs. FDA-Granted Exclusivities

While often conflated in public discourse, patents and FDA exclusivities are fundamentally different forms of protection that serve distinct purposes and operate concurrently.32

A patent is a property right issued by the USPTO to an inventor. It grants the owner the right to exclude others from making, using, selling, or importing the claimed invention for a limited period, which is generally 20 years from the patent application’s earliest effective filing date.32 Patents protect the

invention itself, which can be a new chemical entity, a formulation, a method of manufacturing, or a new method of using a drug.

FDA regulatory exclusivity, in contrast, is a statutory marketing right granted by the FDA upon the approval of a drug. It prevents the FDA from approving certain types of competing drug applications (primarily generic applications) for a defined period.32 This protection is tied to the

drug product and its regulatory approval, not the underlying invention.

The U.S. system provides for several key types of FDA exclusivity, each designed to incentivize specific types of research and development.

| Exclusivity Type | Statutory Basis | Duration | Triggering Event & Purpose | Effect on Generic/Biosimilar Entry |

| New Chemical Entity (NCE) | Hatch-Waxman Act | 5 years | Granted upon approval of a drug containing an active moiety never before approved by the FDA. Incentivizes development of novel drugs.32 | Bars FDA from accepting a generic application (ANDA) for 4 years (if patent is challenged) or 5 years (if no patent challenge). |

| Orphan Drug (ODE) | Orphan Drug Act | 7 years | Granted to a drug designated and approved to treat a rare disease or condition (affecting <200,000 people in the U.S.).32 | Bars FDA from approving any other application for the same drug for the same orphan indication. |

| New Clinical Investigation | Hatch-Waxman Act | 3 years | Granted for an application or supplement that contains new clinical studies (other than bioavailability) essential for approval (e.g., new dosage form, new indication).32 | Bars FDA from approving a generic application that relies on the new clinical data for 3 years. |

| Pediatric Exclusivity (PED) | Best Pharmaceuticals for Children Act | 6 months | Granted as an add-on to existing patents and exclusivities when the sponsor conducts pediatric studies requested by the FDA.32 | Extends all existing patent and exclusivity periods for the drug by 6 months. |

| 180-Day Generic Exclusivity | Hatch-Waxman Act | 180 days | Awarded to the first generic applicant to file a substantially complete ANDA with a Paragraph IV certification challenging a listed patent.32 | The first-to-file generic has the exclusive right to market its product for 180 days before other generics can be approved. |

Table 2: Compendium of U.S. Pharmaceutical Exclusivities. This table provides a summary of the major types of patent and FDA-granted exclusivities, their legal basis, duration, and effect on market competition.32

B. The Hatch-Waxman Framework: Balancing Innovation Incentives with Generic Competition

The modern architecture of the U.S. pharmaceutical market was established by the Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984, universally known as the Hatch-Waxman Act.34 This landmark legislation created a grand compromise designed to balance two competing goals: preserving the incentives for innovator companies to develop new medicines and streamlining the process for affordable generic drugs to enter the market.35

For the generic industry, Hatch-Waxman was transformative. It created the Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) pathway, which allows generic manufacturers to gain FDA approval by demonstrating that their product is bioequivalent to the innovator’s drug. This relieves them of the need to conduct their own costly and time-consuming clinical trials to prove safety and efficacy, as they can rely on the FDA’s prior findings for the brand-name product.35 The Act also established a crucial “safe harbor,” permitting generic companies to conduct development work necessary for an ANDA submission without being liable for patent infringement during the research phase.35

For innovator companies, the Act provided two key benefits to compensate for the new generic pathway. First, it created the system of FDA regulatory exclusivities (such as the 5-year NCE exclusivity) to provide a guaranteed period of market protection.37 Second, it established the mechanism for Patent Term Extension (PTE), allowing companies to apply to have the term of a patent restored for a portion of the time that was lost due to lengthy FDA regulatory review.3

C. The Orange Book: From a Simple Listing to a Strategic Battleground

At the heart of the Hatch-Waxman framework is the FDA’s publication, “Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations,” commonly known as the Orange Book.35 As part of an NDA, an innovator company is required to submit to the FDA a list of patents that it believes claim the drug or a method of using the drug, which the FDA then publishes in the Orange Book.38

This listing process is far from a simple administrative task; it is the trigger for the Act’s most powerful and contentious litigation mechanism. When a generic company files an ANDA, it must make a certification for each patent listed in the Orange Book for the reference drug. A “Paragraph IV” certification states that the generic company believes the listed patent is invalid, unenforceable, or will not be infringed by its product.40

Filing a Paragraph IV certification is considered a technical act of patent infringement, allowing the innovator company to sue the generic applicant immediately. If the innovator files suit within 45 days of receiving notice of the Paragraph IV filing, it triggers an automatic 30-month stay of the FDA’s ability to grant final approval to the generic drug.42 This stay provides time for the courts to resolve the patent dispute. Critically, the stay is granted automatically upon the filing of the lawsuit, regardless of the underlying merits or strength of the patent in question.39 This feature has transformed the Orange Book from a mere informational resource into a primary tool of competitive strategy. The incentive to list any plausibly relevant patent is immense, as the reward is a potential 30-month delay of competition, creating the very friction that has drawn intense scrutiny from the FTC.

D. The Role of Post-Grant Challenges: An Analysis of PTAB and IPR Statistics

Beyond district court litigation, the America Invents Act (AIA) of 2011 created an alternative venue for challenging the validity of issued patents: the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) at the USPTO.45 The primary mechanism for these challenges is the Inter Partes Review (IPR), a trial-like proceeding designed to be faster and less expensive than federal court litigation. An analysis of PTAB statistics reveals unique trends for the biopharmaceutical sector.

Filing and Institution Trends: IPR petitions challenging bio/pharma patents represent a relatively small portion of the PTAB’s overall docket, consistently accounting for only 6-7% of total filings in recent fiscal years.46 The electrical and computer technology sectors dominate filings, making up 69% of the total in FY2024.46 However, despite this low volume, bio/pharma petitions have the highest rate of being instituted for trial. In FY2024, the institution rate for bio/pharma petitions was 73%, significantly higher than the 68% average across all technologies.47 This suggests that the patent challenges being brought in the bio/pharma space are often well-founded and successfully demonstrate a “reasonable likelihood” that at least one challenged claim is unpatentable.

Outcomes and Settlements: The outcomes for bio/pharma patents at the PTAB present a more complex picture. While the institution rate is high, historical data suggests that once a trial is instituted, claims in bio/pharma patents have a higher survival rate compared to claims in other technology areas.48 This seeming paradox—high institution rates followed by relatively strong performance in trial—indicates that while many challenges have initial merit, the core claims of instituted patents are often robust enough to withstand the full trial process. This dynamic reinforces the value of a layered patent portfolio; IPRs may successfully weed out weaker secondary patents, but they do not necessarily invalidate the entire protective structure.

Furthermore, a substantial number of IPR proceedings do not reach a final written decision on the merits. In FY2024, 32% of all concluded IPRs ended in a settlement between the parties.46 This highlights the significant role of the PTAB as a catalyst for business negotiations, where the threat of patent invalidation can drive parties to agree on a generic entry date or other licensing terms, resolving disputes outside of a final legal verdict.

IV. A Tale of Two Agencies: Contrasting the USPTO’s Findings with the FTC’s Enforcement Crusade

While the USPTO and FDA have embarked on a path of enhanced collaboration to improve patent quality, a third federal agency, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), has taken a markedly different and more aggressive approach to pharmaceutical patents. The resulting landscape is one of significant regulatory tension, where the USPTO’s data-driven study, which largely validates existing patenting practices, coexists with an FTC enforcement crusade that treats some of those same practices as presumptively anticompetitive. This divergence stems not from a disagreement over facts, but from the agencies’ fundamentally different statutory mandates and the distinct legal questions they are tasked with answering.

A. The Collaborative Front: USPTO-FDA Initiatives to Bolster Patent Quality

In the wake of President Biden’s 2021 Executive Order on “Promoting Competition in the American Economy,” the USPTO and FDA have formalized a series of collaboration initiatives.49 The stated goals are to ensure the patent system incentivizes meaningful innovation while not being used to “unjustifiably delay” the entry of affordable generic and biosimilar drugs.33

These initiatives are primarily focused on improving the inputs and processes of patent examination to enhance the “robustness and reliability” of issued patents.38 Key activities include:

- Information Sharing and Training: The USPTO is providing its patent examiners with training on how to use publicly available FDA resources (such as drug labels and approval documents) in their prior art searches, and the FDA is receiving resources to better understand the patenting process.49

- Consistency of Statements: A major focus is on preventing applicants from making inconsistent representations to the two agencies. The agencies are exploring mechanisms to help patent examiners identify situations where an applicant might describe an innovation as a minor change to the FDA to secure swift approval, while simultaneously arguing to the USPTO that it is a non-obvious, groundbreaking invention to secure a patent.33 The Federal Circuit case of

Belcher Pharma v. Hospira, which involved exactly this scenario, has served as a catalyst for this effort.53 - Public Engagement: The agencies have held joint public listening sessions and issued requests for comments to gather broader stakeholder input on areas for further collaboration.38

This collaborative approach represents a systemic, long-term strategy to improve patent quality at the source, operating on the principle that better-examined, more robust patents will lead to a more balanced and efficient market.

B. The FTC’s War on “Junk Patents”: Policy Statements, Warning Letters, and Amicus Briefs

In sharp contrast to the USPTO’s process-oriented approach, the FTC has launched a direct, enforcement-led campaign targeting what it labels “improper” or “junk” patent listings in the Orange Book. In a major policy shift in September 2023, the FTC issued a formal statement asserting that improperly listing patents in the Orange Book can constitute an “unfair method of competition” in violation of Section 5 of the FTC Act.39

The FTC’s primary argument is that companies are strategically listing patents that do not meet the narrow statutory criteria—claiming the drug substance, a drug formulation, or a method of using the drug—in order to trigger the automatic 30-month stay and block generic competition.39 The agency has specifically targeted patents covering drug delivery devices, such as asthma inhalers and diabetes autoinjectors, arguing that these patents claim the device, not the drug itself, and are therefore ineligible for Orange Book listing.55

This policy statement was not merely theoretical. The FTC has followed through with concrete enforcement actions:

- Warning Letters: The FTC has sent letters to numerous pharmaceutical companies, including AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, and Novo Nordisk, challenging over 400 patent listings for blockbuster drugs like Ozempic, Victoza, and various asthma medications.42 The agency simultaneously notified the FDA of these disputes, triggering a regulatory process that requires the patent holder to either delist the patent or certify under penalty of perjury that the listing is proper.57 In response to this pressure, several companies have voluntarily delisted challenged patents.57

- Amicus Briefs: The FTC has actively intervened in private patent litigation by filing amicus (“friend of the court”) briefs. In cases such as Teva v. Amneal and Mylan v. Sanofi, the FTC has argued that improper listings cause significant harm to competition and consumers by illegitimately delaying access to lower-cost generic alternatives.43

C. Reconciling Divergent Views: Different Mandates, Different Questions

The federal government is effectively pursuing two parallel and potentially conflicting policy paths. The USPTO-FDA collaboration represents a “quality-focused” path aimed at improving the inputs to the patent system over the long term. The FTC’s actions represent an “enforcement-focused” path that targets the strategic use of the system’s outputs—the issued and listed patents—as anticompetitive conduct in the short term.

These divergent approaches can be reconciled by understanding that the agencies are operating under different legal mandates and are asking fundamentally different questions.

- The USPTO asks a patent law question: “Does the claimed invention meet the statutory requirements for patentability under Title 35 of the U.S. Code (e.g., novelty, non-obviousness)?” Its study reflects this perspective by analyzing the characteristics of granted patents. From this viewpoint, a validly issued patent on a new inhaler device is a legitimate “follow-on innovation”.6

- The FTC asks an antitrust law question: “Is the act of listing that device patent in the Orange Book an unfair method of competition under the FTC Act, because its purpose and effect is to improperly trigger a 30-month stay and block generic entry?”.39 From this perspective, the patent’s validity is secondary to the competitive harm caused by its strategic listing.

Therefore, a patent can be perfectly valid from the USPTO’s perspective but still be deemed “improperly listed” from the FTC’s perspective. This creates a complex compliance challenge for pharmaceutical companies, which must now navigate the requirements of both patent law and the FTC’s evolving interpretation of competition law.

D. Implications of FTC Actions for Brand and Generic Listing Strategies

The FTC’s aggressive posture introduces a new dimension of legal and financial risk for innovator companies. The decision of which patents to list in the Orange Book is no longer a routine regulatory filing but a strategic choice that could trigger an FTC investigation or provide ammunition for private antitrust lawsuits. This new reality is forcing a shift toward what might be called “strategic compliance,” where every patenting and listing decision must be stress-tested not only for its validity under patent law but also for its potential interpretation by competition enforcers.

This heightened risk may lead innovator companies to adopt more conservative listing strategies, potentially refraining from listing patents on ancillary technologies like delivery devices, even if they have a good-faith belief that such patents are listable. The battleground for this issue is clearly centered on blockbuster drug-device combination products, such as GLP-1 agonists for diabetes and weight loss and complex asthma inhalers.57 The legal ambiguity surrounding whether a patent on a device that is essential for delivering a drug “claims the drug” makes this a prime area for the FTC to establish new legal precedent. A victory for the FTC in this domain would dramatically reshape the intellectual property landscape for a significant and highly profitable segment of the pharmaceutical market.

For generic and biosimilar manufacturers, the FTC’s actions provide a powerful new ally. They can now petition the FTC to investigate and challenge what they believe are improper listings, adding another tool to their arsenal alongside traditional patent litigation in district court and IPR proceedings at the PTAB.

V. Strategic Imperatives and Future Outlook

The complex interplay of the USPTO’s empirical findings, the FTC’s enforcement actions, and the ongoing legislative debates creates a dynamic and uncertain environment for all stakeholders in the pharmaceutical industry. Navigating this landscape requires a forward-looking approach that integrates legal, regulatory, and commercial strategies. The future of pharmaceutical competition will likely be shaped less by sweeping changes to substantive patent law and more by procedural reforms and the evolving application of antitrust principles to patenting conduct.

A. For Innovator Companies: Rethinking Patent Portfolio Strategy

For innovator companies, the era of prioritizing patent quantity over quality is drawing to a close. The traditional strategy of building a dense “thicket” with numerous, potentially weak or duplicative patents now carries significant risk. Such a portfolio not only invites costly IPR challenges but also attracts the scrutiny of the FTC and provides a clear target for legislative reform efforts aimed at curbing patent abuse.58

The modern imperative is to build a multi-layered portfolio of high-quality, defensible patents. This requires a proactive and integrated approach where patent strategy is not an afterthought handled by the legal department in isolation, but a core component of the R&D and commercialization process from its earliest stages.60 A robust portfolio should be built around a strong foundational patent on the active pharmaceutical ingredient, supplemented by a strategic and defensible series of patents on genuinely innovative and clinically meaningful improvements, such as novel formulations that improve bioavailability, new methods of use that address unmet medical needs, or advanced delivery systems that enhance patient safety and compliance.62

In this environment, competitive and patent intelligence becomes paramount. Innovator companies must continuously monitor the landscape to understand competitor R&D pipelines, identify technological white space for future innovation, and anticipate potential patent challenges. Leveraging sophisticated patent intelligence platforms and services can transform patent data from a static legal record into a dynamic tool for proactive business strategy, informing decisions on everything from R&D investment to lifecycle management and litigation defense.62

B. For Generic and Biosimilar Manufacturers: Leveraging Regulatory Nuances for Market Entry

For generic and biosimilar manufacturers, the path to market entry is a high-stakes endeavor that demands a sophisticated, multi-pronged strategy. The potential rewards are substantial; the first generic entrant often captures a dominant market share and benefits from a period of higher pricing before full commoditization sets in.68 The 180-day market exclusivity granted to the first generic applicant to successfully challenge a patent remains a powerful incentive that drives early and aggressive litigation.32

Successfully navigating the innovator’s patent estate requires leveraging all available tools. This includes:

- Paragraph IV Litigation: Filing an ANDA with a Paragraph IV certification to challenge patents in federal district court remains the primary pathway to market.41

- Inter Partes Review (IPR): Utilizing the PTAB to challenge the validity of questionable patents offers a faster, more focused, and often more successful venue for invalidating weak claims, especially given the high institution rate for bio/pharma patents.47

- FTC Engagement: The FTC’s new enforcement posture provides a novel avenue for challenging anticompetitive behavior. Generic firms can now report what they believe to be improper Orange Book listings to the FTC, potentially triggering an agency investigation that can add significant pressure on the brand manufacturer.42

The decision of which products to pursue and when to launch is a complex calculation of risk and reward, involving deep analysis of the innovator’s patent portfolio, the likely costs of litigation, manufacturing hurdles, and the competitive landscape of other potential generic entrants.69

C. Policy Horizons: The Future of Patent Reform

The current tensions in the regulatory landscape are likely to spur legislative and administrative reforms. While fundamental changes to the core principles of patentability are unlikely, policy efforts will probably focus on the procedural aspects of patenting and litigation that are perceived as being “gamed.”

The most prominent area for reform is the use of terminal disclaimers to build patent thickets. The USPTO’s previously contemplated rule change, which would have rendered a family of terminally disclaimed patents unenforceable if a core patent was invalidated, is a concept that could be revived in Congress.2 Bipartisan legislative proposals like the Eliminating Thickets to Improve Competition (ETHIC) Act aim to address this issue directly by limiting a patent holder to asserting only one patent from a terminally disclaimed family in litigation against a single challenger.42 Such procedural reforms represent a path of lower political resistance than rewriting substantive patent law and could significantly alter the strategic calculus of building and litigating large patent portfolios.

Another area of focus will be inter-agency coordination. The friction between the USPTO’s findings and the FTC’s actions highlights a need for a more coherent “whole-of-government” approach.38 Future policy could involve formalizing data sharing protocols or even granting the FDA a more substantive role in reviewing the relevance of patents submitted for Orange Book listing, a task it currently performs only in a ministerial capacity.71

D. Concluding Analysis: The Enduring Tension

The pharmaceutical patent system is built upon an enduring and necessary tension: the need to provide powerful incentives for the costly and high-risk endeavor of discovering new medicines, and the parallel need to ensure that the public has affordable access to those medicines once a reasonable period of exclusivity has passed.33

The USPTO’s Drug Patent and Exclusivity Study provides valuable empirical data suggesting that, at least in terms of actual market outcomes for the drugs it examined, the system may be functioning closer to its intended balance than the most severe critiques suggest. The average 11.4-year exclusivity period is far from the perpetual monopoly sometimes portrayed in public debate.

However, the study’s narrow scope does not capture the full picture. The aggressive patenting strategies employed by some companies, detailed in case studies of drugs like Humira and Enbrel, combined with the FTC’s forceful response, demonstrate that the rules of the system are being tested at their limits. The debate is no longer just about the validity of individual patents, but about whether the strategic accumulation and assertion of those patents can, in itself, constitute anticompetitive conduct.

Ultimately, the future landscape of pharmaceutical competition will not be defined by a single study or court decision. It will be shaped by an ongoing, dynamic recalibration of patent law, competition law, and regulatory policy. The challenge for policymakers, regulators, and the industry alike will be to fine-tune the system’s procedural rules to curb strategic gamesmanship without undermining the core incentives that drive the next generation of breakthrough therapies.

Works cited

- The Economic Underpinnings of Patent Law – Chicago Unbound, accessed August 3, 2025, https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1508&context=law_and_economics

- Debunking Patent Disinformation: Insights from the USPTO’s Drug Patent and Exclusivity Study – Council for Innovation Promotion (C4IP), accessed August 3, 2025, https://c4ip.org/debunking-patent-disinformation-insights-from-the-usptos-drug-patent-and-exclusivity-study/

- USPTO Publishes Drug Patent and Exclusivity Study Report – The National Law Review, accessed August 3, 2025, https://natlawreview.com/article/uspto-publishes-drug-patent-and-exclusivity-study-report

- USPTO Publishes Drug Patent and Exclusivity Study Report | Foley & Lardner LLP, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.foley.com/insights/publications/2024/06/uspto-publishes-drug-patent-exclusivity-study-report/

- Debunked: USPTO Findings Should End False Pharma Patent Narratives – IPWatchdog.com, accessed August 3, 2025, https://ipwatchdog.com/2024/10/28/debunked-uspto-findings-end-false-pharma-patent-narratives/id=182568/

- Biden Administration report debunks myths around patent “evergreening” and “thickets”, accessed August 3, 2025, https://phrma.org/blog/biden-administration-report-debunks-myths-around-patents

- Drug patent and exclusivity study – USPTO, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.uspto.gov/sites/default/files/documents/USPTO_Drug_Patent_and_Exclusivity_Study_Report.pdf

- Drug Patent and Exclusivity Study available – USPTO, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.uspto.gov/initiatives/fda-collaboration/drug-patent-and-exclusivity-study-available

- Overview of the USPTO Drug Exclusivity Report, accessed August 3, 2025, https://c4ip.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/Overview-of-the-USPTO-Drug-Exclusivity-Report-September-2024.pdf

- Drug patents: the evergreening problem – PMC, accessed August 3, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3680578/

- Pharmaceutical Patents and Evergreening (VIII) – The Cambridge Handbook of Investment-Driven Intellectual Property, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/cambridge-handbook-of-investmentdriven-intellectual-property/pharmaceutical-patents-and-evergreening/9A97A3E6D258E9A47DCF88E5EA495F44

- Evergreening of patents: an elixir of life for pharmaceutical companies, accessed August 3, 2025, https://patentlawyermagazine.com/evergreening-of-patents-an-elixir-of-life-for-pharmaceutical-companies/

- Does Drug Patent Evergreening Prevent Generic Entry …, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/does-drug-patent-evergreening-prevent-generic-entry/

- About the Evergreen Drug Patent Database – UC Law Sites, accessed August 3, 2025, https://sites.uclawsf.edu/evergreensearch/about/

- May your drug price be evergreen | Journal of Law and the Biosciences – Oxford Academic, accessed August 3, 2025, https://academic.oup.com/jlb/article/5/3/590/5232981

- Patent Settlements Are Necessary To Help Combat Patent Thickets, accessed August 3, 2025, https://accessiblemeds.org/resources/blog/patent-settlements-are-necessary-to-help-combat-patent-thickets/

- In the Thick(et) of It: Addressing Biologic Patent Thickets Using the Sham Exception to Noerr-Pennington, accessed August 3, 2025, https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/iplj/vol33/iss3/5/

- The Dark Reality of Drug Patent Thickets: Innovation or Exploitation …, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-dark-reality-of-drug-patent-thickets-innovation-or-exploitation/

- Biological patent thickets and delayed access to biosimilars, an American problem – PMC, accessed August 3, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9439849/

- Patent Thickets: Law and Economics in Action – Oxford Royale, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.oxford-royale.com/articles/patent-thickets-law-economics-action

- SECOND OPINION: BIG PHARMA ONCE AGAIN TRIES TO DEFEND THE PATENT ABUSE STATUS QUO – CSRxP.org, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.csrxp.org/second-opinion-big-pharma-once-again-tries-to-defend-the-patent-abuse-status-quo/

- Patent Abuses Keep Prescription Drugs Unaffordable | Issue Brief | Healthcare, accessed August 3, 2025, https://americafirstpolicy.com/issues/patent-abuses-keep-prescription-drugs-unaffordable

- Patent thickets are pricing Americans out of medicine – FREOPP, accessed August 3, 2025, https://freopp.org/oppblog/patent-thickets-are-pricing-americans-out-of-medicine/

- Humira – I-MAK, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.i-mak.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/i-mak.humira.report.3.final-REVISED-2020-10-06.pdf

- Opinion: Lessons From Humira on How to Tackle Unjust Extensions of Drug Monopolies With Policy – BioSpace, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.biospace.com/policy/opinion-lessons-from-humira-on-how-to-tackle-unjust-extensions-of-drug-monopolies-with-policy

- A three-decade monopoly: how Amgen built a patent thicket around …, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.biopharmadive.com/news/amgen-enbrel-patent-thicket-monopoly-biosimilar/609042/

- Lessons From Humira on How to Tackle Unjust Extensions of Drug …, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.biospace.com/policy/opinion-lessons-from-humira-on-how-to-tackle-unjust-extensions-of-drug-monopolies-with-policy/

- Chamber Says USPTO Drug Patent Report Exposes ‘Activist’ Data as ‘Fake Facts’, accessed August 3, 2025, https://ipwatchdog.com/2024/07/01/chamber-says-uspto-drug-patent-report-exposes-activist-data-fake-facts/id=178486/

- 1490-Disclaimers – USPTO, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.uspto.gov/web/offices/pac/mpep/s1490.html

- www.uspto.gov, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.uspto.gov/web/offices/pac/mpep/s1490.html#:~:text=A%20terminal%20disclaimer%20is%20a,(filed%20in%20an%20application).

- 804-Definition of Double Patenting – USPTO, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.uspto.gov/web/offices/pac/mpep/s804.html

- What is a terminal disclaimer and how does it affect patent rights? – BlueIron IP, accessed August 3, 2025, https://blueironip.com/ufaqs/what-is-a-terminal-disclaimer-and-how-does-it-affect-patent-rights/

- Patents and Exclusivity | FDA, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/media/92548/download

- Patents and Drug Pricing: Why Weakening Patent Protection Is Not in the Public’s Best Interest – American Bar Association, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.americanbar.org/groups/intellectual_property_law/resources/landslide/2025-spring/drug-pricing-weakening-patent-protection-not-best-interest/

- cdn.aglty.io, accessed August 3, 2025, https://cdn.aglty.io/phrma/global/blog/import/pdfs/Fact-Sheet_What-is-Hatch-Waxman_June-2018.pdf

- 40th Anniversary of the Generic Drug Approval Pathway | FDA, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/cder-conversations/40th-anniversary-generic-drug-approval-pathway

- What is Hatch-Waxman? – PhRMA, accessed August 3, 2025, https://phrma.org/resources/what-is-hatch-waxman

- Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act – Wikipedia, accessed August 3, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Drug_Price_Competition_and_Patent_Term_Restoration_Act

- Joint USPTO-FDA Collaboration Initiatives; Notice of Public Listening Session and Request for Comments – Federal Register, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2022/11/07/2022-24107/joint-uspto-fda-collaboration-initiatives-notice-of-public-listening-session-and-request-for

- FTC Issues Policy Statement on Brand Pharmaceutical Manufacturers’ Improper Listing of Patents in the Food and Drug Administration’s ‘Orange Book’, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/news/press-releases/2023/09/ftc-issues-policy-statement-brand-pharmaceutical-manufacturers-improper-listing-patents-food-drug

- Full article: Continuing trends in U.S. brand-name and generic drug competition, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13696998.2021.1952795

- NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES NO FREE LAUNCH: AT-RISK ENTRY BY GENERIC DRUG FIRMS Keith M. Drake Robert He Thomas McGuire Alice K. N, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w29131/w29131.pdf

- Second FTC and DOJ Listening Session Focuses on Formulary and Benefit Practices and Regulatory Abuse in the Pharmaceutical Industry | Troutman Pepper Locke – JD Supra, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.jdsupra.com/legalnews/second-ftc-and-doj-listening-session-5077145/

- FTC Files Amicus Brief Outlining Anticompetitive Harm Caused by Improper Orange Book Listings, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/news/press-releases/2023/11/ftc-files-amicus-brief-outlining-anticompetitive-harm-caused-improper-orange-book-listings

- Hatch-Waxman Act – Practical Law, accessed August 3, 2025, https://uk.practicallaw.thomsonreuters.com/Glossary/PracticalLaw/I2e45aeaf642211e38578f7ccc38dcbee

- Statistics | USPTO, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.uspto.gov/patents/ptab/statistics

- PTAB AIA FY2024 Roundup: Key Insights and Statistics, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.ptablitigationblog.com/ptab-aia-fy2024-roundup-key-insights-and-statistics/

- Trial Statistics Trends at the PTAB: 2024 Edition, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.ptablaw.com/2025/01/06/trial-statistics-trends-at-the-ptab-2024-edition/

- IPR and biopharma patents: what the statistics show – Akin Gump, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.akingump.com/a/web/39881/aoi5X/ipr-and-biopharma-patents_-what-the-statistics-show_gf.pdf

- USPTO-FDA Joint Engagements, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.uspto.gov/initiatives/uspto-fda-collaboration/engagements

- USPTO – FDA Collaboration Initiatives, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.uspto.gov/initiatives/fda-collaboration

- USPTO-FDA Collaboration: Progress Towards Patently True Interagency Coordination – Food and Drug Law Institute (FDLI), accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.fdli.org/2023/10/uspto-fda-collaboration-progress-towards-patently-true-interagency-coordination/

- FDA and USPTO Announce Public Listening Session to Promote Greater Access to Medicines – Duane Morris, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.duanemorris.com/alerts/fda_uspto_announce_public_listening_session_promote_greater_access_medicines_1222.html

- Initiatives to Increase Communication Between the USPTO and the FDA Concerning Pharmaceutical Patent Applications – Dechert LLP, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.dechert.com/knowledge/onpoint/2023/2/left-hand–meet-right-hand—-should-there-be-more-communication.html

- Federal Trade Commission Statement Concerning Brand Drug …, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.ftc.gov/legal-library/browse/federal-trade-commission-statement-concerning-brand-drug-manufacturers-improper-listing-patents

- The FTC Challenges Companies’ Allegedly Improper Orange Book Patent Listings | Insights | Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom LLP, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.skadden.com/insights/publications/2024/06/quarterly-insights/the-ftc-challenges-companies

- Recent Decisions and FTC Challenges Dictate Caution When Listing Patents in the Orange Book – Fish & Richardson, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.fr.com/insights/thought-leadership/blogs/recent-decisions-and-ftc-challenges-dictate-caution-when-listing-patents-in-the-orange-book/

- FTC Expands Patent Listing Challenges, Targeting More Than 300 Junk Listings for Diabetes, Weight Loss, Asthma and COPD Drugs, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/news/press-releases/2024/04/ftc-expands-patent-listing-challenges-targeting-more-300-junk-listings-diabetes-weight-loss-asthma

- Welch introduces bipartisan legislation to streamline drug patent litigation | Vermont Business Magazine, accessed August 3, 2025, https://vermontbiz.com/news/2025/july/16/welch-introduces-bipartisan-legislation-streamline-drug-patent-litigation

- Welch, Braun, and Klobuchar Introduce Bipartisan Legislation to Streamline Drug Patent Litigation, Lower Cost of Prescription Drugs, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.welch.senate.gov/welch-braun-and-klobuchar-introduce-bipartisan-legislation-to-streamline-drug-patent-litigation-lower-cost-of-prescription-drugs/

- The Patent Playbook Your Lawyers Won’t Write: Patent strategy development framework for pharmaceutical companies – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-patent-playbook-your-lawyers-wont-write-patent-strategy-development-framework-for-pharmaceutical-companies/

- Patent Defense Isn’t a Legal Problem. It’s a Strategy Problem. Patent Defense Tactics That Every Pharma Company Needs – Drug Patent Watch, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/patent-defense-isnt-a-legal-problem-its-a-strategy-problem-patent-defense-tactics-that-every-pharma-company-needs/

- Optimizing Your Drug Patent Strategy: A Comprehensive Guide for …, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/optimizing-your-drug-patent-strategy-a-comprehensive-guide-for-pharmaceutical-companies/

- How Patent Law Affects the Pharmaceutical Industry Under U.S. Health Laws – PatentPC, accessed August 3, 2025, https://patentpc.com/blog/how-patent-law-affects-the-pharmaceutical-industry-under-u-s-health-laws

- DrugPatentWatch | Software Reviews & Alternatives – Crozdesk, accessed August 3, 2025, https://crozdesk.com/software/drugpatentwatch

- Drug Patent Watch, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/

- Patenting Drugs Developed with Artificial Intelligence: Navigating the Legal Landscape, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/patenting-drugs-developed-with-artificial-intelligence-navigating-the-legal-landscape/

- Leveraging Patent Data to Inform R&D Strategy: A Guide for In-House Counsel | PatentPC, accessed August 3, 2025, https://patentpc.com/blog/leveraging-patent-data-to-inform-rd-strategy-a-guide-for-in-house-counsel

- First Generic Launch has Significant First-Mover Advantage Over Later Generic Drug Entrants – DrugPatentWatch – Transform Data into Market Domination, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/first-generic-launch-has-significant-first-mover-advantage-over-later-generic-drug-entrants/

- Top 10 Challenges in Generic Drug Development – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/top-10-challenges-in-generic-drug-development/

- Generic Drug Entry Timeline: Predicting Market Dynamics After Patent Loss, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/generic-drug-entry-timeline-predicting-market-dynamics-after-patent-loss/

- Towards FDA–USPTO Cooperation – Scholarship @ GEORGETOWN LAW, accessed August 3, 2025, https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3662&context=facpub

- FDA REEXAMINATION: INCREASED COMMUNICATION BETWEEN THE FDA AND USPTO TO IMPROVE PATENT QUALITY | Published in Houston Law Review, accessed August 3, 2025, https://houstonlawreview.org/article/66217-fda-reexamination-increased-communication-between-the-fda-and-uspto-to-improve-patent-quality

- The Role of Patents and Regulatory Exclusivities in Drug Pricing | Congress.gov, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/R46679