Part I: Anatomy of a Crisis – The Landscape of Generic Drug Shortages

Section 1: The Paradox of the Modern Generic Market

The Promise of Generics

The modern American healthcare system is built upon a foundational promise: the availability of safe, effective, and affordable generic drugs. Accounting for nearly 90% of all prescriptions filled in the United States, generic medicines are the bedrock of patient access and a powerful engine of cost containment.1 Over the past decade alone, their use has saved the U.S. healthcare system an estimated $3.1 trillion, with savings reaching $445 billion in 2023.4 This system was formally codified by the Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984, commonly known as the Hatch-Waxman Act, which created a streamlined pathway for generic drug approval.

At its core, a generic drug is a medication that is chemically identical to its brand-name counterpart. As defined by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), a generic must have the same active ingredient, strength, dosage form, and route of administration as the original brand-name drug.5 To gain approval, a generic manufacturer must submit an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA), a process that, critically, does not require the repetition of the expensive and time-consuming clinical trials that were necessary for the original drug’s approval.4 Instead, the generic manufacturer must prove through bioequivalence studies that its product performs in the body in approximately the same way as the brand-name drug.2 The FDA allows for only a slight, medically unimportant level of natural variability, consistent with the variation seen between different batches of the same brand-name product.5 Furthermore, all manufacturing, packaging, and testing facilities for generic drugs must adhere to the same stringent Current Good Manufacturing Practice (CGMP) regulations as those for brand-name drugs; in many cases, generics are produced in the very same plants.5

This abbreviated pathway, unburdened by the high costs of initial research, development, and marketing, is what allows multiple manufacturers to enter the market upon patent expiration, fostering competition that dramatically lowers prices for consumers and payers.1 The result is a market intended to deliver ubiquitous, low-cost alternatives for a vast array of medical conditions.

The Paradox of Scarcity

Despite the robust framework designed to ensure widespread availability, the generic drug market is now defined by a persistent and deepening crisis of scarcity. Hospitals, clinics, and pharmacies across the nation routinely find themselves unable to procure basic, life-sustaining generic medications. This is the central paradox of the modern generic market: a system engineered for affordable access has become a breeding ground for chronic unavailability. The very economic forces and purchasing mechanisms that have been celebrated for driving down prices have, in a cruel twist of incentives, created a market structure that is economically unsustainable for many producers and inherently fragile.9 The relentless pursuit of the lowest possible price has systematically stripped manufacturers of the profit margins necessary to invest in quality, modernize facilities, and build resilient supply chains. The result is a brittle system, prone to disruption and slow to recover, where the workhorses of modern medicine—from chemotherapy agents to anesthetics to simple saline solutions—are frequently and unpredictably out of reach. This report will dissect this paradox, analyzing the systemic failures that have transformed the promise of generic drugs into a persistent problem of scarcity.

Defining the Terminology

To navigate this complex landscape, a precise understanding of the terminology is essential. While often used interchangeably, several distinct categories of off-patent drugs exist:

- Generic Drug: As defined by the FDA, a generic drug is a medication created to be the same as an already marketed brand-name drug in dosage form, safety, strength, route of administration, quality, performance characteristics, and intended use. These drugs do not need to contain the same inactive ingredients as the brand-name product.5 They are typically marketed under a non-proprietary or “generic” name, which is often a shorthand version of the drug’s chemical name.7

- Branded Generic: This term refers to a generic drug that is marketed under a proprietary brand name, which is owned by the manufacturing company. A branded generic must be bioequivalent to the original brand product but is often developed by a generic company or the original manufacturer after the patent expires. This strategy is used to create brand recognition in a crowded generic market. For example, Aviane, Orsythia, and Vienva are all branded generics of the same oral contraceptive formulation.6

- Authorized Generic: An authorized generic is an exact copy of the brand-name drug, marketed under a private label but authorized by the original patent holder. It is produced under the brand company’s New Drug Application (NDA) and is identical to the branded product in every way, including its appearance (shape, color, markings) and its inactive ingredients. This is a key distinction from standard generics, which can differ in appearance and inactive components.6

- Biosimilar: While generics are copies of small-molecule chemical drugs, biosimilars are the equivalent for large, complex biological products (biologics). Due to the complexity of biologics, a biosimilar is not an exact copy but is “highly similar” to an already-approved biological product, with no clinically meaningful differences in terms of safety, purity, and potency.6

This report will primarily focus on traditional generic drugs, as they constitute the vast majority of shortages, but the underlying economic principles often apply across these categories.

Section 2: Quantifying the Shortage Epidemic

Data-Driven Overview

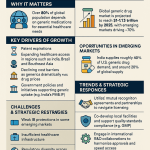

The problem of generic drug shortages is not anecdotal; it is a quantifiable and escalating public health crisis. Analysis of data from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) reveals that between 2018 and 2023, a total of 258 unique active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), or molecules, went into a national shortage. These 258 molecules are represented by 1,961 unique prescription drug products, identifiable by their National Drug Code (NDC) numbers.12

The data unequivocally shows that this crisis disproportionately affects the generic market. During that same 2018-2023 period, over twice as many generic drug shortages began (1,391) as brand drug shortages (600).12 This disparity is not merely a reflection of generics being more common; it is indicative of a systemic vulnerability within the generic market itself. An analysis by IQVIA as of June 2023 found that of the 132 molecules in active shortage, 84% were generics.14 This confirms that the market segment designed to be the most accessible is, in fact, the most prone to failure.

Worsening Trends: Frequency and Duration

The crisis is not static; it is worsening along two critical dimensions: frequency and duration. The number of active drug shortages has reached its highest point in a decade. The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP), which tracks shortages independently, reported a record high of 323 active drug shortages during the first quarter of 2024, surpassing the previous peak of 320 shortages in 2014.15 Data from the U.S. Pharmacopeia (USP) corroborates this trend, showing a steady climb from 82 shortages in December 2014 to 125 by December 2023.17

Even more alarming than the frequency is the dramatic increase in the duration of these shortages. According to USP analysis, the average drug shortage now lasts for an astonishing 1,202 days—more than three years. This is a significant increase from an average of about two years in 2020.9 The problem is not just that drugs are becoming unavailable; it is that they are staying unavailable for extended, clinically disruptive periods. As of the end of 2023, 27 ongoing shortages had persisted for more than five years, and six had been in shortage for over a decade.17 This chronicity transforms shortages from acute supply chain hiccups into a permanent feature of the healthcare landscape, profoundly impacting patient care planning and hospital operations. A Government Accountability Office (GAO) report confirms that while the number of

new shortages has generally decreased since the COVID-19 pandemic, the existing shortages are lasting longer, worsening the overall problem.18

Vulnerable Drug Categories

A granular analysis of the data reveals that certain categories of drugs are exceptionally vulnerable. The overwhelming majority of shortages involve older, low-cost, sterile injectable medications. These are the workhorse drugs of hospital care, used in operating rooms, intensive care units, and cancer clinics.

More than half (53%) of all new drug shortages are for generic sterile injectables.9 These products are inherently more complex and costly to manufacture than solid oral drugs, requiring specialized facilities and strict aseptic processing to ensure sterility.9 This manufacturing complexity, combined with extremely low prices, creates a perfect storm for market fragility. The average wholesale acquisition cost of sterile injectable medicines in shortage was found to be nearly 8.5 times lower than those not in shortage, highlighting the powerful link between low price and shortage risk.9 An IQVIA analysis found that 56% of molecules in shortage were priced at less than $1.00 per unit.14

The dosage form is also a strong predictor of shortage duration. Shortages of injectable products last significantly longer than those of other forms. HHS data shows a median shortage duration of 4.6 years for injectables, compared to just 1.6 years for oral products and 2.2 years for topical products.12 This extended duration for injectables reflects the difficulty and time required for new or existing manufacturers to ramp up production of these complex products when a primary supplier fails.

Impacted Therapeutic Areas

The shortages are not confined to a single corner of medicine; they cut across a wide range of critical therapeutic classes. At the beginning of 2024, analgesics/anesthetics (17%), anti-infectives (12%), and cardiovascular products (13%) comprised 42% of all ongoing shortages.19 Other heavily impacted areas include oncology, psychiatry, and gastroenterology.14

The current drug shortage lists maintained by organizations like ASHP and Drugs.com provide a stark, real-time picture of the crisis. As of mid-2024, the lists are replete with essential medicines:

- Oncology: Backbone chemotherapy drugs like cisplatin and carboplatin have been in severe, persistent shortage, threatening the care of hundreds of thousands of cancer patients.14

- Anesthesia and Pain Management: Anesthetics like lidocaine and bupivacaine, as well as analgesics like hydromorphone and fentanyl, are frequently unavailable, impacting surgical procedures and critical care.21

- Anti-Infectives: Basic antibiotics like amoxicillin and penicillin have experienced shortages, driven by unpredictable demand and manufacturing issues.14

- Cardiovascular Drugs: Emergency medications like epinephrine and foundational drugs like furosemide are often in short supply.21

- Basic Hospital Supplies: Even the most fundamental products, such as 0.9% Sodium Chloride (“saline”) and 5% Dextrose injection bags, are on the shortage list, demonstrating the depth of the supply chain’s fragility.22

Crucially, drugs deemed “essential” by the federal government are frequently affected. These essential medicines account for roughly one-third of all drug products that go into shortage. Furthermore, shortages of these critical products last much longer, with a median duration of 4.0 years, compared to 2.3 years for non-essential medicines.12 This indicates that the most medically necessary products are often the most insecure.

| Table 1: Trends in U.S. Drug Shortages (2018-2024) | |||||

| Metric | 2018-2023 (Cumulative) | 2023 (End of Year) | Q1 2024 | Key Trends & Insights | |

| New Shortages (Unique Molecules) | 258 12 | 34 (new in 2023) 17 | N/A | Consistent stream of new shortages entering the system. | |

| Total Products in Shortage | 1,961 (representing the 258 molecules) 12 | 125 (ongoing) 17 | 323 (ongoing, ASHP) 15 | The number of ongoing shortages remains at a decade-high level. | |

| Breakdown of New Shortages (Generic vs. Brand) | Generic: 1,391; Brand: 600 12 | Generic: 84% of active shortages 14 | N/A | Generics are overwhelmingly more likely to be in shortage. | |

| Average Shortage Duration | Median: 4.6 yrs (Injectable), 1.6 yrs (Oral) 12 | 1,202 days (over 3 years) 9 | N/A | Shortage durations have increased dramatically, almost by a full year since 2020. | |

| Breakdown by Dosage Form (New Shortages) | Injectable: 50% 12 | Injectable: 53%; Oral: 32% 17 | N/A | Sterile injectables are the most vulnerable product category. | |

| Impact on Essential Medicines | 29.4% of shortages; Median duration: 4.0 years 12 | N/A | N/A | The most critical medicines face longer and more frequent shortages. | |

| Sources: Data synthesized from HHS 12, USP 9, IQVIA 14, and ASHP.15 |

Part II: The Root Causes – A Market Engineered for Fragility

Section 3: The Economics of Unsustainability: A “Race to the Bottom”

The Central Economic Failure

The persistent scarcity of generic drugs is not a series of isolated, unfortunate events. It is the predictable and logical outcome of a market structure that has been engineered, both intentionally and unintentionally, for profound economic fragility. The root cause of the vast majority of generic drug shortages is an economic model that relentlessly prioritizes the lowest possible price above all other considerations, including manufacturing quality, supply chain resilience, and long-term market stability.10 This has created what is widely described as a “race to the bottom,” where intense competition drives prices for many essential medicines to levels that are economically unsustainable for the manufacturers who produce them.24

In a functional market for a commodity, price serves as a critical signal. When supply is tight or production costs rise, prices should increase, signaling to existing producers to ramp up manufacturing and to new producers that there is a profitable opportunity to enter the market. In the U.S. generic drug market, this signaling mechanism is fundamentally broken. Prices are driven so low that they often approach or even fall below the marginal cost of production, leaving manufacturers with razor-thin or negative profit margins.9 This is particularly true for the older, sterile injectable products that are most frequently in shortage. A 2023 USP analysis found that the average price of sterile injectable medicines in shortage was nearly 8.5 times lower than those not in shortage, while IQVIA reported that 56% of all molecules in shortage cost less than $1.00 per unit.9 When a company cannot make a profit on a product, or is actively losing money on every vial it sells, the economic incentive to continue production vanishes.

Price Erosion and Market Exit

The mechanism driving this unsustainability is severe and continuous price deflation, fueled by the market’s structure.10 While patients and payers benefit from lower prices in the short term, the long-term consequences are dire. Faced with shrinking or nonexistent profits, manufacturers are forced into a stark choice: either exit the market for a particular low-margin product entirely, or drastically cut costs to remain viable.10

Increasingly, manufacturers are choosing to exit. Product discontinuations have been rising sharply, increasing by 40% between 2022 and 2023 alone, from 100 to 140 products.9 This was the highest rate of discontinuations since 2019.17 The majority of these discontinued products were extremely low-priced; over half of the discontinued solid oral medications, for example, had a price tag of less than $4.26 Since 2010, there have been over 3,000 generic product discontinuations.10

When a manufacturer exits a market, the supply base for that drug shrinks. This market consolidation is a direct consequence of the economic pressure. As more firms drop out, the market is left with fewer and fewer suppliers, often becoming a duopoly or even a monopoly.3 A recent economic study found that more than 40% of all generics have only a single producer.3 This high level of concentration makes the entire supply chain exquisitely vulnerable. If one of the few remaining suppliers experiences any kind of disruption—a manufacturing line goes down, a batch fails a quality test, a facility is damaged in a natural disaster—there is insufficient redundant capacity in the market to make up for the shortfall, and a shortage becomes almost inevitable.13

Disincentives for Quality and Resilience

The alternative to market exit is to remain in the market by ruthlessly cutting costs, which directly undermines quality and resilience. The extreme focus on price as the sole determinant of purchasing decisions creates a powerful and perverse disincentive for manufacturers to make crucial investments in their operations. In a market with razor-thin margins, there is no financial return on investment for upgrading aging equipment, modernizing facilities, maintaining robust quality management systems, or building redundant manufacturing capacity.9 As one USP expert noted, “Quality comes at a price,” and the economics of the generic market leave no room to pay it.9

This lack of investment is not a theoretical risk; it has tangible consequences. It directly leads to a higher likelihood of manufacturing failures, quality control problems, and violations of the FDA’s Current Good Manufacturing Practice (CGMP) regulations.11 These quality issues are a primary trigger for production slowdowns or halts, as companies must address deficiencies identified during FDA inspections. When a facility with quality problems is one of only a handful of suppliers for a given drug, its production halt can immediately tip the entire market into a shortage.26

The market structure does not merely fail to reward reliability; it actively punishes it. Consider two hypothetical manufacturers of a generic injectable. Manufacturer A invests heavily in a state-of-the-art facility, redundant production lines, and an advanced quality control system. Its cost of production is $1.50 per vial. Manufacturer B operates an older facility with no redundancy and minimal investment beyond what is required to pass a basic inspection. Its cost of production is $1.00 per vial. In the U.S. generic market, where purchasing decisions are driven almost exclusively by price, Manufacturer B will win the supply contract every time. Manufacturer A, despite producing a more reliable supply, will be uncompetitive on price and will eventually be forced to either lower its quality standards or exit the market. This creates a vicious cycle where the least resilient, most fragile producers are systematically rewarded with market share, guaranteeing a future of chronic shortages.

Section 4: The Role of the Middlemen: GPO and Wholesaler Consolidation

Concentrated Buying Power

While the economic pressures on manufacturers are immense, they do not operate in a vacuum. A primary driver of the “race to the bottom” is the extraordinary concentration of purchasing power in the hands of a few powerful intermediary organizations, namely Group Purchasing Organizations (GPOs) and large drug wholesalers. The U.S. generic drug market is not a traditional competitive market with many diffuse buyers and sellers. Instead, it functions as an oligopsony—a market dominated by a small number of powerful buyers.3

This concentration is extreme. In the hospital sector, just three large GPOs—Vizient, Premier, and HealthTrust—control the purchasing for approximately 90% of all generic medicines acquired by hospitals and clinics.10 A similar dynamic exists in the retail pharmacy market, where three purchasing consortiums, which are combinations of major wholesalers (like AmerisourceBergen, Cardinal Health, and McKesson) and large retail pharmacy chains, collectively control about 90% of the market.10 This means that the more than 200 generic drug manufacturers in the U.S. are competing for the business of a mere handful of dominant buyers.10 This massive imbalance of power gives the buyers almost complete control over pricing and contract terms.

Contracting Practices and Price Pressure

GPOs were created with the stated goal of lowering healthcare costs by aggregating the purchasing volume of thousands of individual hospitals to negotiate better prices from suppliers.29 While they have been successful in driving down prices, their aggressive negotiation tactics and contracting practices are now widely cited as a primary cause of the unsustainable price deflation that fuels shortages.3

GPOs typically award contracts based on the lowest price offered, often in a “winner-take-all” or “dual-source” model that locks in a manufacturer for a specific period.31 This forces manufacturers into fierce price wars to win the contract, as losing it means being shut out from a massive portion of the market. This dynamic directly contributes to the price erosion that squeezes manufacturer margins to unsustainable levels. Furthermore, the business model of GPOs themselves can create perverse incentives. GPOs are typically funded by administrative fees paid by the manufacturers who win the contracts. These fees are often calculated as a percentage of the drug’s sales volume or price.30 This can create conflicts of interest where the GPO’s financial incentives are not aligned with ensuring a stable and resilient supply chain, but rather with maximizing fees, which can be influenced by drug price and volume dynamics.32

The public discourse on pharmaceutical markets often focuses on the consolidation of manufacturers (an oligopoly) as a cause of high prices for brand-name drugs.34 However, the data on the

generic market reveals the opposite structure: a consolidation of buyers (an oligopsony).3 In a seller’s oligopoly, a few powerful firms might tacitly collude to keep prices high. In a buyer’s oligopsony, a few powerful buyers have the leverage to force prices down to ruinously low levels for all sellers. This structural difference explains the central paradox of the generic market: it is simultaneously highly concentrated, yet characterized by extremely low prices, not high ones. The market power wielded by GPOs and their associated wholesalers is therefore a more direct and potent driver of the economic fragility leading to generic drug shortages than manufacturer consolidation. This reframes the problem from one of too few sellers to one of too few, and too powerful, buyers.

The FTC/HHS Inquiry

The role of these powerful middlemen has come under intense federal scrutiny, representing a major shift in the policy debate. In February 2024, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) jointly issued a formal Request for Information (RFI) to investigate how the practices of GPOs and drug wholesalers may be contributing to generic drug shortages.33 This inquiry signals that the federal government now views these intermediaries as a potential root cause of the crisis.

The RFI seeks public comment on a range of critical issues, including 33:

- The extent of market concentration among GPOs and wholesalers.

- Whether their contracting practices are anti-competitive and disincentivize new suppliers from entering the market.

- The impact of the prevailing GPO compensation model, which relies on fees and rebates from manufacturers.

- Whether the “safe harbor” provision of the federal Anti-Kickback Statute, which protects GPO administrative fees, is contributing to market distortions and shortages.

- The negative impact of these practices on smaller healthcare providers and rural hospitals, who have less leverage.

FTC Chair Lina M. Khan explicitly stated that the inquiry aims to “scrutinize the practices of opaque drug middlemen” as a driver of critical shortages.33 The response from the generic drug industry, represented by the Association for Accessible Medicines (AAM), has been to fully support the inquiry, calling on the FTC to investigate the “excessive consolidation of intermediary participants” and their “anti-competitive contract terms” which they argue are the root causes of shortages.36 This federal investigation, and the clear battle lines it has drawn between manufacturers and buyers, marks a pivotal moment in understanding and potentially reforming the broken generic drug market.

Section 5: The Perverse Incentives of Policy: Government Reimbursement and Regulation

The economic fragility of the generic drug market is not solely the result of private market dynamics; it is significantly exacerbated by a web of federal and state government policies. While often designed with laudable goals such as controlling government spending or supporting safety-net providers, these policies can have severe, unintended consequences for the stability of the generic supply chain. They often create a rigid pricing environment that prevents the market from responding to normal economic signals, thereby contributing directly to shortages.

Unintended Consequences of Reimbursement

Several key federal reimbursement policies, particularly within Medicare and Medicaid, create perverse incentives that punish manufacturers for attempting to maintain viable pricing for their products.

- Medicaid Inflation Rebates: The Medicaid Drug Rebate Program requires manufacturers to pay a rebate to states if they increase a drug’s price faster than the rate of inflation. While this policy is effective at controlling spending on high-priced brand drugs, it is fundamentally ill-suited for the low-cost, highly competitive generic market.24 A generic manufacturer’s price can fluctuate due to factors outside its control, such as the entry or exit of a competitor. More importantly, this policy can prevent a manufacturer from implementing a necessary, modest price increase to cover rising input costs (e.g., for raw materials or labor). This effectively traps them at an unsustainably low price point. If a manufacturer begins losing money on a product due to rising costs and is unable to raise the price without incurring a substantial penalty, its only rational choice is to discontinue the product.16 The problem is particularly acute for older generic drugs that were on the market before 2013, as their inflation penalty is calculated from an arbitrary baseline period in 2014, by which time their prices may have already been driven down to near-marginal cost.24

- Medicare Reimbursement: Medicare policies also contribute to this price inflexibility. For provider-administered drugs covered under Medicare Part B, there is a two-quarter lag in the application of the Average Sales Price (ASP) to the reimbursement rate.24 This means if a manufacturer raises its price in the first quarter of the year, providers will not receive the higher reimbursement rate from Medicare until the third quarter. In the interim, providers would lose money by administering that drug, creating a strong incentive for them to switch to a lower-priced competitor. This lag effectively punishes any manufacturer who attempts to raise prices first. For drugs administered in the hospital inpatient setting, the costs are often bundled into a single Diagnosis-Related Group (DRG) payment. This gives hospitals a powerful incentive to purchase the absolute lowest-cost generic available to maximize their margin on the bundled payment, reinforcing the GPO-driven “race to the bottom”.38

These policies, in concert, create a one-way ratchet on generic drug prices. They can fall easily due to competitive pressure, but they are extremely difficult to raise, even when economically justified. A functional market allows prices to rise in response to scarcity or increased costs, signaling a need for more supply. By creating an artificially rigid pricing environment, these federal reimbursement policies strip the market of its ability to adapt to changing economic conditions, directly contributing to the fragility of the supply chain and the inevitability of shortages.

The 340B Drug Pricing Program

The 340B Drug Pricing Program, which requires drug manufacturers to provide significant discounts on outpatient drugs to eligible safety-net hospitals and clinics, is another area of policy with potential unintended consequences.39 The program is a vital lifeline for these providers, allowing them to stretch scarce resources and provide more comprehensive services to underserved communities.40

However, the mandatory discounts required by the 340B program can further erode the already thin revenue streams for low-margin generic drugs.24 While the statutory discount is set at a certain percentage, it can become much larger if a drug’s price rises faster than inflation, creating what is known as a “penny price” where the drug must be sold for a nominal amount. For a manufacturer already struggling with profitability on a generic product, the additional financial burden of 340B discounts could be the tipping point that leads to a decision to exit the market.24

The impact of the 340B program on shortages is a subject of intense debate. Proponents argue it is essential for the survival of safety-net providers, and some studies have found no significant difference in generic prescribing patterns between 340B and non-340B clinicians, suggesting it does not create an incentive to favor higher-priced brand drugs.41 However, industry groups and some policy experts maintain that the program’s downward price pressure on generics is a contributing factor to market instability and shortages, particularly for drugs with a large share of sales in the 340B program.24 The inclusion of 340B limitations in recent legislative proposals to address shortages indicates that policymakers view it as part of the complex web of economic factors that must be addressed.37

Section 6: The Brittle Global Supply Chain

Beyond the economic and policy failures that define the U.S. market, a series of physical and logistical vulnerabilities in the global pharmaceutical supply chain make it brittle and prone to disruption. These vulnerabilities range from the geographic concentration of raw material production to the lack of buffer stock at the point of care.

Geographic Concentration of Manufacturing

A primary structural risk in the pharmaceutical supply chain is its heavy geographic concentration, particularly in the manufacturing of Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs)—the core chemical components that give a drug its therapeutic effect. The U.S. market is profoundly dependent on a small number of foreign countries for these critical inputs, especially for generic drugs.

Analysis of FDA Drug Master Files (DMFs) by the U.S. Pharmacopeia (USP) provides a stark picture of this dependency. As of 2021, India and China were the dominant sources of APIs for the U.S. market. India accounted for a staggering 48% of all active API DMFs, while China accounted for 13%.42 The United States itself accounted for only 10%.42 This reliance has grown over time; India’s share of new API filings has soared, while Europe’s has declined significantly.42 This extreme concentration means that the supply of thousands of essential medicines in the U.S. is vulnerable to a single point of failure in another part of the world. A natural disaster (like a hurricane or earthquake), a geopolitical conflict, a trade dispute leading to export restrictions, or a domestic policy change in India or China could instantly disrupt the flow of essential raw materials, triggering widespread shortages in the U.S..9 The COVID-19 pandemic laid bare these vulnerabilities when lockdowns in key manufacturing regions caused immediate supply chain shocks.44

| Table 2: Geographic Concentration of API Manufacturing for U.S. Market (2021) | |||

| Region/Country | Percentage of Active API Drug Master Files (DMFs) | Key Associated Risks | |

| India | 48% 42 | Geopolitical instability, quality control variability, vulnerability to natural disasters, potential for export restrictions. | |

| China | 13% 42 | Significant geopolitical tensions with the U.S., dependency on pricing policies, risk of supply weaponization, quality control concerns. | |

| United States | 10% 42 | Limited domestic capacity for many essential APIs, higher production costs making it uncompetitive for low-priced generics. | |

| Europe | 7% (new filings in 2021) 42 | Declining share of manufacturing, higher operating costs, reliance on external suppliers for raw materials. | |

| Rest of World | 32% (total active DMFs) | Diverse risks depending on the specific country, including political instability and logistical challenges. | |

| Source: Data synthesized from U.S. Pharmacopeia (USP) Medicine Supply Map.42 |

Manufacturing Quality and FDA Enforcement

The economic pressures detailed in Section 3 have a direct and damaging effect on the physical quality of the manufacturing base. The relentless drive for lower costs leads to chronic underinvestment in facilities and quality systems.9 This, in turn, results in a higher rate of manufacturing failures, product contamination, and violations of the FDA’s CGMP regulations.

When an FDA inspection uncovers significant quality or safety issues at a manufacturing plant, the agency can issue a Warning Letter or take other enforcement actions that force the facility to slow or completely halt production to remediate the problems.28 While essential for protecting public health, such an action can be the immediate trigger for a national drug shortage, especially if the affected facility is one of only a few—or the sole—supplier of a particular drug. A clear example of this was the severe and prolonged shortage of the generic chemotherapy drug cisplatin, which began after the FDA flagged critical safety and quality issues at a single plant in India that was responsible for supplying at least half of the entire U.S. market.26 This demonstrates how a single quality failure at a concentrated point in the supply chain can have catastrophic, nationwide consequences.

The “Just-in-Time” Trap

At the opposite end of the supply chain, a vulnerability exists at the point of care within U.S. hospitals. Over the past few decades, hospitals have widely adopted hyper-efficient “just-in-time” (JIT) inventory management models.46 This practice is designed to minimize the high costs associated with storing large quantities of medical supplies on-site. Instead of maintaining large stockpiles, hospitals rely on their distributors to deliver products frequently, often daily, keeping only a few days’ worth of inventory on hand.46

While this model is highly efficient and cost-effective during normal times, it creates extreme fragility in the face of supply chain disruptions. JIT inventory systems effectively eliminate any buffer stock within the hospital that could absorb a delay or interruption in supply.19 When a manufacturing problem occurs upstream, there is no cushion at the end of the chain. A delay of even a few days can mean that a hospital completely runs out of a critical medication, leading to an immediate stockout at the patient’s bedside.46 The COVID-19 pandemic starkly illustrated this weakness, as a surge in demand for certain products combined with upstream disruptions quickly overwhelmed the lean JIT system, leading to widespread shortages of PPE and essential drugs.46

The Launch Gap: Approved but Unavailable

Perhaps the most damning evidence of a fundamentally broken market is the growing phenomenon of the “launch gap”—the significant delay, or complete failure, of generic drugs to be marketed even after they have received full FDA approval. A company invests significant time and resources to navigate the complex ANDA process and prove to the FDA that its product is safe, effective, and bioequivalent.2 Yet, once approval is granted, the decision to actually launch the product is a purely commercial one.2

Stunning data from IQVIA reveals the scale of this problem. Between 2013 and early 2024, a remarkable 37% of all approved generics had not been launched in the U.S. market.48 The situation is even worse for drugs that are already in shortage. For drugs currently experiencing a shortage, 62% have at least one FDA-approved generic alternative available. However, of those, an astonishing 84% have at least one approved generic that has not been launched, and 21% have no approved generics launched at all.48 This represents a massive, untapped reservoir of potential supply that is being held back from the market. Injectables are again disproportionately affected, with 75% of drug shortages involving an unlaunched generic in injectable form.48

The existence of this launch gap is the ultimate symptom of the market’s economic failure. The only logical reason a for-profit company would choose not to launch a product that it has already spent millions of dollars to get approved is if its analysis shows that the projected revenue and profit from entering the market are zero or, more likely, negative. It is the final, irrefutable proof that the “race to the bottom” has created a market environment so toxic and unprofitable that it actively deters market entry, even when all scientific and regulatory hurdles have been cleared. This failure to launch is not just a business decision; it is a direct cause of prolonged and preventable shortages, leaving patients and hospitals without access to medicines that are, for all intents and purposes, ready to be made and sold.

Part III: The Human and Financial Toll of Unavailability

The systemic failures of the generic drug market are not abstract economic or logistical problems. They translate into tangible, severe, and often devastating consequences for patients, the healthcare professionals who care for them, and the financial stability of the hospitals where that care is delivered. The chronic unavailability of essential medicines inflicts a heavy toll measured in patient harm, increased costs, and professional burnout.

Section 7: The Impact on Patient Care and Safety

The Spectrum of Patient Harm

A drug shortage is never a minor inconvenience; it is a direct threat to patient health and, in some cases, to life itself. The consequences span a wide spectrum of harm, from delayed care to fatal medication errors. A comprehensive scoping review in the journal PLOS One found that drug shortages were predominantly reported to have adverse clinical, economic, and humanistic outcomes for patients.49

- Treatment Delays and Cancellations: When a critical drug is unavailable, the most immediate impact is the delay or outright cancellation of necessary medical care. Patients with cancer may have their chemotherapy courses postponed, potentially compromising the curability of their disease.50 Surgeries, including life-saving procedures like organ transplants and open-heart surgeries, may be cancelled if essential drugs like heparin or protamine are not available.50 This not only delays care but also creates immense psychological distress for patients and their families.

- Forced Use of Suboptimal Alternatives: In the face of a shortage, clinicians are often forced to substitute the preferred, first-line therapy with a second- or third-line alternative. These alternatives may be less effective, have a less favorable side-effect profile, or be less studied for a particular condition.50 For example, during shortages of standard antibiotics, physicians report being forced to use broader-spectrum antibiotics, which can contribute to antimicrobial resistance, or less effective therapies that negatively impact patient outcomes.53

- Increased Medication Errors: The use of unfamiliar alternative drugs, or even different concentrations or vial sizes of the same drug, dramatically increases the risk of medication errors. Staff may be unaccustomed to the dosing, preparation, or administration of the substitute drug, leading to dangerous and sometimes fatal mistakes.49 A classic high-risk example is the shortage of the diuretic furosemide. A common alternative is bumetanide, which is 40 times more potent. A failure to correctly account for this dosing difference can easily lead to a massive overdose.50 The Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP) has documented numerous instances of patient harm and death directly attributable to errors made during drug shortages.50

- Adverse Events and Mortality: The use of less-safe alternatives can lead to an increase in adverse drug reactions and patient toxicities.49 More gravely, studies have now drawn direct statistical links between drug shortages and increased patient mortality. A landmark study on the 2011 shortage of norepinephrine, a critical vasopressor used to treat septic shock, found that the shortage was associated with a 3.7 percentage point increase in in-hospital mortality for affected patients.13 This translates to thousands of excess deaths attributable to the unavailability of a single, inexpensive generic drug. A scoping review found that of 16 studies examining mortality, 10 reported an increase during shortages.49

The Human Narrative

Beyond the statistics, the true toll of drug shortages is measured in human suffering. Patient advocacy groups like Angels for Change have collected powerful stories that illustrate the profound personal impact of this crisis.55 These are stories of:

- Pediatric cancer patients, like Brannon and Ryan, whose life-saving chemotherapy regimens were disrupted mid-treatment, leaving their families in a state of fear and uncertainty about whether they would get the care they needed to survive.55

- Patients with chronic conditions, like Graysen, a high school student with ADHD, who struggles to manage her studies because the constant shortages of her medication lead to erratic dosing. Her parents are forced into a monthly race, calling pharmacy after pharmacy to find a supply before it runs out.55

- Vulnerable patients, like Brooke, who relies on daily IV hydration for survival. When a hurricane caused a shortage of IV fluids, her infusion company rationed their supply, and as a new patient, she was at the bottom of the list, facing the prospect of going without the nourishment that kept her alive at home.55

These stories reveal the deep anxiety, frustration, and helplessness that shortages inflict on patients and their families, turning the process of receiving routine medical care into a constant struggle for survival.

Health Equity Implications

The burden of drug shortages is not distributed equally across the population. The crisis disproportionately harms patients in smaller, rural, or under-resourced communities, thereby exacerbating existing health disparities. Larger, well-resourced hospital systems often have more purchasing power, larger pharmacy staffs dedicated to shortage management, and greater ability to procure scarce drugs from alternative suppliers.20 They may also engage in “hoarding” or stockpiling when a shortage is anticipated, further limiting the supply available to others.56

Smaller and rural hospitals, with less leverage and fewer resources, are often the last in line to receive allocated products.20 This can lead to a dangerous and inequitable distribution of available drugs, where a medication may be in severe shortage at a small community hospital but in better supply at a large academic medical center in a nearby city.56 This can force patients, particularly those in rural areas, to travel long distances to receive treatment, which may be financially or logistically impossible for many, leading to further delays in care and worsening inequities in health outcomes.20

Section 8: The Hidden Costs to Hospitals

The impact of drug shortages extends beyond patient harm to inflict a significant and often-overlooked financial and operational burden on the hospitals and health systems that are on the front lines of the crisis. Managing the constant state of scarcity consumes enormous resources, drives up costs, and contributes to the burnout of an already strained healthcare workforce.

The Financial Burden

The financial costs to hospitals are substantial and multifaceted, encompassing both direct procurement expenses and indirect labor costs.

- Labor Costs: The single largest financial impact is the immense amount of staff time required to manage shortages. When a drug becomes unavailable, it triggers a cascade of labor-intensive activities. Pharmacy staff—pharmacists and technicians—must spend hours each day tracking inventory levels, investigating the cause and expected duration of the shortage, identifying potential therapeutic alternatives, communicating with multiple suppliers to source the drug, and updating hospital protocols and electronic health records (EHRs).54 This work diverts highly skilled clinical pharmacists from patient care activities to supply chain logistics. A 2024 report from the GPO Vizient quantified this hidden cost, estimating that U.S. hospitals now spend

$894 million annually on labor costs related to drug shortage management. This represents a staggering 150% increase from the $359 million spent in 2019.59 In terms of time, this translates to

20.2 million staff hours spent managing shortages in 2024, up from 8.6 million hours in 2019.59 - Procurement Costs: When a hospital’s primary, contracted supplier is unable to provide a drug due to a shortage, the hospital is forced to turn to alternative sources. This often means purchasing from secondary distributors, sometimes referred to as the “gray market.” These secondary suppliers operate outside the normal GPO-contracted system and can charge exorbitant prices for drugs that are in high demand. Surveys of hospital pharmacists consistently report markups of 300% to 500%, and sometimes as high as 3000%, for drugs on the shortage list.57 Vizient’s analysis found that, on average, sourcing essential medicines from these secondary distributors costs hospitals

214% more than purchasing from their primary, contracted distributors.59 This price gouging adds millions of dollars in unexpected drug acquisition costs to hospital budgets annually.57

| Table 3: Financial and Labor Impact of Drug Shortages on U.S. Hospitals | ||

| Metric | Value/Finding | Source/Year |

| Annual Labor Cost for Shortage Management | $894 Million (a 150% increase from 2019) | Vizient, 2024 59 |

| Annual Staff Hours Spent on Shortage Management | 20.2 Million Hours | Vizient, 2024 59 |

| Average Cost Markup from Secondary Distributors | 214% higher than primary distributors | Vizient, 2024 59 |

| Reported Price Markups from Alternative Suppliers | 300% to 500% (common) | Survey of Pharmacists, 2015 57 |

| Reported Disruptions to Patient Care | 41% of facilities report outpatient infusion disruptions | Vizient, 2024 59 |

| Additional FTEs Required to Manage Shortages | Average of 10 additional staff hours per week for system updates | Survey of Pharmacists, 2015 57 |

The Administrative and Emotional Burden on Staff

The impact on hospital staff goes beyond financial metrics. The relentless, “daily crisis” of managing drug shortages is a significant contributor to stress, fatigue, and burnout among healthcare professionals, particularly pharmacists.58 The constant need to react to new shortages, scramble for alternatives, and manage the clinical risks associated with substitutions places an immense cognitive and emotional load on a workforce that is already facing staffing challenges.54

Pharmacists find themselves in the difficult position of having to ration care, making ethically fraught decisions about which patients will receive a scarce medication and which will not.56 They must also manage the downstream effects of shortages, which can create new and dangerous challenges. For instance, the vacuum created by a shortage can give rise to counterfeit or substandard drugs entering the supply chain, placing the burden on pharmacists to distinguish fraudulent products from legitimate ones.60 This constant fire-fighting mode not only detracts from their primary clinical responsibilities but also erodes morale and job satisfaction, contributing to the broader crisis of burnout in the healthcare sector.

Part IV: Pathways to a Resilient Supply Chain

Analyzing the root causes and devastating consequences of generic drug shortages is a necessary but insufficient exercise. The persistence of this crisis demands a shift from diagnosis to action. A resilient and reliable supply chain will not emerge from the current market structure on its own; it must be actively built through a combination of bold legislative reforms, innovative private sector initiatives, and a fundamental realignment of market incentives. No single “silver bullet” exists. Instead, a multi-pronged strategy is required to address the complex, interconnected failures that underpin the problem.

Section 9: Reforming the Market: Legislative and Policy Solutions

Federal Legislative Efforts

Recognizing the systemic nature of the crisis, the U.S. Congress has begun to develop bipartisan legislative proposals aimed at reshaping the fundamental economic dynamics of the generic drug market. The most significant of these is the Drug Shortage Prevention and Mitigation Act, a discussion draft unveiled by the leaders of the Senate Finance Committee.15 This act represents a crucial first step toward correcting the market’s core failures by creating incentives that value reliability, not just the lowest price. Key proposals within the draft include:

- Medicare Drug Shortage Prevention and Mitigation Program: This is the cornerstone of the proposed legislation. It would establish a new, voluntary program within Medicare to reward responsible purchasing practices. Under this program, hospitals, GPOs, and wholesalers who opt-in would receive quarterly incentive payments for entering into contracts with generic manufacturers that include terms designed to promote stability. These terms would include long-term purchasing commitments (e.g., three years), guaranteed purchase volumes, and stable, predictable pricing.26 This program is a direct attempt to counter the “race to the bottom” by creating a powerful, demand-side pull for reliability. It seeks to create a viable market segment where manufacturers can receive a fair, sustainable price in exchange for guaranteeing a stable supply.

- Medicaid Rebate Reform: The draft legislation directly targets the perverse incentives created by federal reimbursement policies. It proposes to suspend or adjust the mandatory Medicaid inflation rebates for certain low-cost or shortage-prone generic drugs.16 This reform is designed to relieve the policy-driven price inflexibility that currently traps manufacturers at unsustainable price points and prevents them from making necessary price adjustments to cover rising costs. By allowing for more rational pricing, this provision aims to reduce the number of policy-driven market exits that lead to shortages.

- 340B Program Limitations: The draft also addresses the potential impact of the 340B Drug Pricing Program. It includes a provision that would require participants in the new Medicare incentive program to forgo using 340B discounts for the specific generic drugs identified as vulnerable to shortage.37 This represents a targeted approach to mitigate the program’s downward price pressure on the most fragile segments of the generic market, without dismantling the entire 340B program.

Enhancing Transparency and FDA Authority

Alongside market reforms, other policy levers aim to improve transparency and strengthen the FDA’s ability to prevent and mitigate shortages. A key proposal advocated by ASHP and other stakeholders is to require the public reporting of the FDA’s Quality Management Maturity (QMM) ratings for manufacturing facilities.38 QMM is a program designed to assess and rate the maturity and robustness of a manufacturer’s quality systems. Making these ratings public would, for the first time, allow purchasers like hospitals and GPOs to factor a manufacturer’s demonstrated commitment to quality and reliability into their purchasing decisions, creating a market-based reward for quality.38

These proposals build on authorities granted to the FDA under the 2020 Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act. The CARES Act enhanced the FDA’s ability to require manufacturers to notify the agency of potential supply interruptions and to develop and maintain formal risk management plans to proactively identify and mitigate potential disruptions.62

Criticism and Limitations

While these legislative efforts are promising, they are not without criticism and limitations. Expert analyses from institutions like the Brookings Institution caution that many proposed solutions are fragmented and may fail if they do not address the entire system of misaligned incentives.27 A primary criticism is that transparency initiatives, such as public QMM ratings, are likely to be ineffective on their own. If purchasers, particularly GPOs and hospitals, are not financially incentivized to pay a premium for reliability, they will continue to choose the lowest-priced option, regardless of its quality rating. Transparency without a corresponding change in purchasing incentives is unlikely to alter market behavior.27

Furthermore, a significant governance failure at the federal level threatens to undermine any new legislative solution. A 2024 report from the Government Accountability Office (GAO) found that the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) lacks a formal, coordinated, department-wide mechanism to oversee and strategize its response to drug shortages.18 This means that the actions of one HHS agency (like CMS, which sets reimbursement rates) can inadvertently undermine the shortage mitigation efforts of another (like the FDA). Shockingly, the GAO also reported that the one senior coordinator position that did exist to oversee supply chain resilience was set to be eliminated in 2025 due to expiring funding.18 This lack of a centralized, empowered, and funded coordinating body represents a critical weakness in the federal government’s ability to tackle this multifaceted crisis effectively.

Section 10: Private Sector and Provider-Led Innovations

While top-down legislative reform is essential, some of the most promising solutions are emerging from the bottom up, as private sector and non-profit actors grow frustrated with the status quo and develop innovative models to disrupt the broken market.

Disrupting the Market from Within

- Non-Profit Manufacturing (Civica Rx): Perhaps the most significant private sector innovation has been the creation of Civica Rx in 2018. Founded by a consortium of major U.S. health systems, Civica is a non-profit generic drug company with a mission to stabilize the supply of essential medicines.65 Its model directly confronts the core economic failures of the traditional market. Instead of engaging in the “race to the bottom,” Civica offers manufacturers stable, predictable, long-term contracts with guaranteed purchase volumes. In exchange for this market certainty, manufacturers commit to supplying drugs at a fair and transparent price.3 This changes the fundamental incentive structure, allowing manufacturers to invest in quality and capacity without fear of being undercut by a lower-priced competitor. Civica is now taking the next step by building its own manufacturing facilities, further securing the supply chain for its member hospitals.65

- Public-Private Partnerships (Angels for Change): Another novel approach comes from patient-led non-profits like Angels for Change. This organization uses a targeted, proactive model to prevent shortages of critical pediatric medicines. Using predictive analytics to identify drugs at high risk of shortage, Angels for Change provides grants to flexible 503B outsourcing facilities to fund proactive manufacturing runs of these vulnerable drugs before a shortage occurs.66 This creates a ready buffer supply that can be deployed immediately when the commercial market fails. A 90-day pilot program demonstrated the model’s success, providing over 140,000 essential medicine treatments to pediatric hospitals during a critical shortage.66

Hospital and Distributor Strategies

In the absence of systemic solutions, individual hospitals and distributors are also implementing their own mitigation strategies. Many health systems are moving away from a pure “just-in-time” inventory model for their most critical drugs, opting instead for a “just-in-case” approach that involves building strategic stockpiles to buffer against supply disruptions.46 They are also actively diversifying their supplier base, seeking to contract with multiple manufacturers for a single drug to avoid reliance on a sole source.67 Healthcare distributors are leveraging their logistical expertise and data analytics to monitor for demand spikes, anticipate potential shortages, and implement allocation programs to ensure equitable distribution of scarce products.68

Onshoring and Domestic Manufacturing

In the wake of the pandemic, there has been a strong political push to “onshore” pharmaceutical manufacturing, bringing it back to the United States to reduce reliance on foreign suppliers.69 This has led to some significant investments, such as AstraZeneca’s plan to build a major new manufacturing facility in Virginia.69 However, while onshoring can help mitigate geopolitical risks, it is not a panacea for the generic drug shortage problem. As policy experts have pointed out, onshoring alone does not solve the underlying economic problem.27 A domestic manufacturing plant that is subject to the same ruinous price pressures from GPOs and inflexible reimbursement policies is just as likely to become unprofitable and cease production as a foreign one. Without fixing the core market incentives, simply changing the location of the factory will not guarantee a resilient supply.

Section 11: A Comparative Perspective: Lessons from Abroad

To fully understand the unique failures of the U.S. system, it is crucial to place them in an international context. The United States, Canada, and major European nations all rely on a similar globalized manufacturing base for APIs and finished drugs. However, their experiences with drug shortages are markedly different, which strongly suggests that the root of the U.S. crisis lies not just in global manufacturing, but in its unique domestic policy and market architecture.

The Canadian Model: A Proactive Approach

A direct comparison with Canada is particularly revealing. A 2024 study published in JAMA found that for drugs with the same reported supply chain issue, Canada was 40% less likely to experience a meaningful national drug shortage than the United States.70 This striking difference points to several key divergences in policy and regulatory approach:

- Proactive Regulation: While both countries mandate that manufacturers report potential supply issues, their regulatory postures differ. The FDA’s approach is often described as more reactive, responding to notifications from manufacturers. In contrast, Health Canada is seen as more proactive, actively monitoring supplies, directly collecting public reports of shortages, and working collaboratively with a wide range of stakeholders—including provincial health systems, manufacturers, and distributors—to prevent and mitigate shortages.71

- Policy Levers: During the pandemic, Canada implemented a range of policies to bolster its supply chain, including competitive government bidding for essential medicines, expanded use of importation from trusted foreign regulators, and improved public reporting on supply status.71

- Stakeholder Cooperation: There appears to be a higher degree of cooperation and coordination among regulatory agencies, public payers, and health systems in Canada, allowing for a more unified response to potential disruptions.72

The U.S. vs. Germany/EU: A Problem of Duration

A comparison with Europe reveals a different dimension of the U.S. system’s failure: its inability to recover from disruptions. A 2024 study comparing shortages in the U.S. and Germany from 2016 to 2023 found that while Germany may have had a higher number of individual shortage incidents, U.S. shortages lasted, on average, 2.5 times longer (a mean duration of 23.5 months in the U.S. versus 9.2 months in Germany).74 For example, a shortage of epinephrine lasted over eight years in the U.S. but only five months in Germany.74

This vast difference in duration suggests that the U.S. market is far more rigid and slower to self-correct once a shortage occurs. This is likely due to a combination of factors, including the price inflexibility created by U.S. reimbursement policies and a greater reluctance to use regulatory flexibilities like importation. For two-thirds of the generic sterile injectable drugs in shortage in the U.S., an approved version of the same drug was available from a manufacturer in another well-regulated market like the UK, Germany, or Canada.75 Yet, the U.S. has been slow to leverage this potential source of supply, as seen in the nine-month delay before the FDA imported a European version of penicillin during a critical shortage in 2023.75

The international comparisons deliver a clear verdict. The U.S., Canada, and Europe all operate within the same globalized manufacturing ecosystem. The fact that the U.S. experiences more frequent shortages than Canada and dramatically longer-lasting shortages than Germany points to a decisive conclusion: the primary drivers of the persistence and severity of the U.S. crisis are domestic. The problem lies in the unique architecture of the U.S. purchasing system, the perverse incentives of its reimbursement policies, and its reactive regulatory culture. Other countries have successfully built more resilient systems on top of the very same global manufacturing base. This insight is critical, as it refutes the simplistic argument that the only solution is to onshore all manufacturing and instead points toward the urgent need for domestic market and policy reform.

Section 12: Conclusion and Strategic Recommendations

Synthesizing the Argument

The chronic shortage of generic drugs in United States hospitals is not an unfortunate accident or an unsolvable problem of globalized supply chains. It is the predictable, logical, and inevitable consequence of a market system that has been optimized for a single variable—the lowest possible price—at the direct and catastrophic expense of manufacturing quality, supply chain reliability, and, ultimately, patient access to essential medicines.

This report has demonstrated that the crisis is driven by a complex and interconnected web of systemic failures. An economic “race to the bottom,” fueled by the concentrated power of a few large purchasing organizations, has rendered the production of many low-cost generics unprofitable. This has systematically stripped manufacturers of the incentive to invest in quality and resilience, leading to market exits and a brittle manufacturing base prone to failure. This fragile market is further destabilized by a patchwork of federal reimbursement policies that create perverse incentives and prevent the market from sending normal price signals in response to scarcity. The result is a broken system where even drugs that have cleared all regulatory hurdles often fail to launch because the market is simply too unprofitable to enter. The devastating consequences are borne by patients, who face treatment delays and dangerous medication errors, and by hospitals, which incur hundreds of millions of dollars in hidden costs and see their staff pushed to the point of burnout.

A Multi-Pronged Path Forward

Solving this persistent problem requires a fundamental shift in perspective—from viewing generics as a simple commodity to be procured at the lowest possible cost, to recognizing them as an essential public good whose reliability is a critical component of national health security. There is no single silver bullet. A durable solution requires an integrated, multi-pronged strategy aimed at re-aligning market incentives to reward and value resilience. The following strategic recommendations represent a pathway to a more stable and secure supply chain:

- Reward Reliability Through Payment Reform: The most critical step is to correct the core market failure by creating a payment differential for reliability. Congress should move swiftly to pass and fund legislation modeled on the Drug Shortage Prevention and Mitigation Act. Establishing a Medicare program that provides direct financial incentives to hospitals and GPOs for engaging in responsible purchasing practices (e.g., long-term, guaranteed-volume contracts with reliable manufacturers) would create the demand-side pull needed to make resilience profitable.

- Reform Intermediary Market Power: The immense and unchecked power of a few GPOs and wholesalers is a primary driver of unsustainable price pressure. The FTC and HHS should be encouraged to complete their joint inquiry and use their full regulatory and antitrust authority to reform contracting practices that are found to be anti-competitive. This should include a thorough review and potential revision of the Anti-Kickback Statute’s safe harbor for GPO administrative fees, which may be distorting the market.

- Fix Perverse Government Policies: Congress and HHS must address the unintended consequences of federal reimbursement policies. This includes targeted reforms to the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program’s inflation penalty for vulnerable generic drugs and modifications to Medicare’s reimbursement rules (such as the ASP lag and DRG bundling) to allow for rational, predictable pricing that can support sustainable manufacturing.

- Foster and Scale Public-Private Innovation: The federal government should actively support and reduce regulatory barriers for innovative, non-profit models that have proven effective at disrupting the broken market. Initiatives like Civica Rx and Angels for Change serve as invaluable real-world laboratories for building a more resilient supply chain. Federal support could help these models scale to cover a wider range of vulnerable medicines.

- Build Strategic Redundancy, Not Just Onshoring: A secure supply chain requires a nuanced approach to manufacturing. Rather than a sole focus on costly and potentially insufficient domestic manufacturing, policy should prioritize strategic redundancy. This includes a combination of diversifying foreign sources to trusted allies (“friend-shoring” and “near-shoring”), incentivizing the maintenance of multiple active manufacturing sites for critical drugs, and building a robust system of buffer inventories, including both private sector stockpiles and an expanded Strategic National Stockpile.

- Establish Coordinated Federal Governance: A fragmented federal response cannot solve a systemic problem. Heeding the recommendation of the GAO, HHS must establish and fund a permanent, empowered coordinating body to orchestrate a national strategy to combat drug shortages. This office must have the authority to ensure that the policies of all relevant federal agencies are aligned and working in concert, rather than at cross-purposes, to promote supply chain resilience.

The path to ending chronic drug shortages will be complex and will require sustained commitment from all stakeholders—policymakers, manufacturers, purchasers, and providers. However, the human and financial costs of inaction are far too high to accept the status quo. By implementing these integrated strategies, it is possible to re-engineer the generic drug market from one that rewards fragility to one that values and ensures the reliable supply of medicines that are fundamental to the health of the nation.

Works cited

- Drug Competition Series – Analysis of New Generic Markets Effect of Market Entry on Generic Drug Prices – HHS ASPE, accessed July 30, 2025, https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/510e964dc7b7f00763a7f8a1dbc5ae7b/aspe-ib-generic-drugs-competition.pdf

- The Generic Drug Approval Process – FDA, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/cder-conversations/generic-drug-approval-process

- Industrial Policy To Reduce Prescription Generic Drug Shortages …, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.americanprogress.org/article/industrial-policy-to-reduce-prescription-generic-drug-shortages/

- The Global Generic Drug Market: Trends, Opportunities, and Challenges – DrugPatentWatch, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-global-generic-drug-market-trends-opportunities-and-challenges/

- Facts About Generic Drugs – FDA, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/media/83670/download

- Generic vs Brand Drugs: Your FAQs Answered, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.drugs.com/article/generic_drugs.html

- 7 FAQs About Generic Drugs | Pfizer, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.pfizer.com/news/articles/7_faqs_about_generic_drugs

- A Review of First-Time Generic Drug Approvals – U.S. Pharmacist, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.uspharmacist.com/article/a-review-of-firsttime-generic-drug-approvals

- U.S. drug shortages reach decade-high and last longer – USP, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.usp.org/news/us-drug-shortages-reach-decade-high-and-last-longer

- Causes … – Association for Accessible Medicines Drug Shortages, accessed July 30, 2025, https://accessiblemeds.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/AAM_White_Paper_on_Drug_Shortages-06-22-2023.pdf

- Drug Shortages in the United States: Are Some Prices Too Low? – PMC, accessed July 30, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7099531/

- Analysis of Drug Shortages, 2018-2023 – HHS ASPE, accessed July 30, 2025, https://aspe.hhs.gov/reports/drug-shortages-2018-2023

- Analysis of Drug Shortages, 2018-2023 – HHS ASPE – HHS.gov, accessed July 30, 2025, https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/efa332939da2064fa2c132bb8e842bb5/Drug%20Shortages_Data%20Brief_Final_2025.01.10.pdf

- Drug Shortages in the U.S. 2023 – – NCOIL, accessed July 30, 2025, https://ncoil.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/IQVIA-Institute-Drug-Shortages-in-the-US-13-11-23_jp.pdf

- Drug shortages | AHA – American Hospital Association, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.aha.org/topics/drug-shortages

- Addressing generic drug shortages: Contributing factors and public policy recommendations – AmerisourceBergen, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.amerisourcebergen.com/-/media/assets/amerisourcebergen/pdf/address-generic-drug-shortages-whitepaper.pdf

- The US drug shortage crisis, in 5 charts – Advisory Board, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.advisory.com/daily-briefing/2024/06/13/drug-shortages

- Drug Shortages: HHS Should Implement a Mechanism to Coordinate Its Activities – GAO, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-25-107110

- Policy Considerations to Prevent Drug Shortages and Mitigate Supply Chain Vulnerabilities in the United States. – HHS ASPE, accessed July 30, 2025, https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/3a9df8acf50e7fda2e443f025d51d038/HHS-White-Paper-Preventing-Shortages-Supply-Chain-Vulnerabilities.pdf

- Crisis of Cancer Drug Shortages: Understanding the Causes and Proposing Sustainable Solutions | JCO Oncology Practice – ASCO Publications, accessed July 30, 2025, https://ascopubs.org/doi/10.1200/OP-25-00381

- 2024 United States drug shortages – Wikipedia, accessed July 30, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2024_United_States_drug_shortages

- Drug Shortages List – ASHP, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.ashp.org/drug-shortages/current-shortages/drug-shortages-list?page=CurrentShortages

- Current Drug Shortages List – Drugs.com, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.drugs.com/drug-shortages/

- Cheaper is not always better: Drug shortages in the United States and a value-based solution to alleviate them, accessed July 30, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11217858/

- The Dynamics of Drug Shortages – OHE – Office of Health Economics, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.ohe.org/publications/the-dynamics-of-drug-shortages/

- Drug shortages are lasting longer, driven by economic pressures: US Pharmacopeia report, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.fiercepharma.com/manufacturing/drug-shortages-are-lasting-longer-driven-economic-pressures-us-pharmacopeia-says

- Drug shortages: A guide to policy solutions | Brookings, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/drug-shortages-a-guide-to-policy-solutions/

- What Do FDA Warning Letters Tell Us? – Greenberg Traurig, LLP, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.gtlaw.com/-/media/files/insights/published-articles/021416_fda.pdf

- The Influence of Pharmacy Benefit Managers on GPO Relevance in Drug Pricing and Contracting | Simbo AI – Blogs, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.simbo.ai/blog/the-influence-of-pharmacy-benefit-managers-on-gpo-relevance-in-drug-pricing-and-contracting-991966/

- At a Glance: Key Differences Between Healthcare Group Purchasing Organizations (GPOs) & Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs), accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.supplychainassociation.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/HSCA-GPO-and-PBM-Comparison.pdf

- Understanding the Effects of Drug Shortages on Hospital Purchasing – QuicksortRx, accessed July 30, 2025, https://quicksortrx.com/blog/understanding-the-effects-of-drug-shortages-on-hospital-purchasing

- The Mechanisms of Group Purchasing Organizations and Their Contribution to Drug Price Inflation in the Pharmaceutical Supply Chain | Simbo AI – Blogs, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.simbo.ai/blog/the-mechanisms-of-group-purchasing-organizations-and-their-contribution-to-drug-price-inflation-in-the-pharmaceutical-supply-chain-3047744/

- FTC, HHS Seek Public Comment on Generic Drug Shortages and …, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/news/press-releases/2024/02/ftc-hhs-seek-public-comment-generic-drug-shortages-competition-amongst-powerful-middlemen

- More trouble: Drug industry consolidation – PNHP, accessed July 30, 2025, https://pnhp.org/news/more-trouble-drug-industry-consolidation/

- FTC, HHS Extend Public Comment Period on Generic Drug Shortages and Competition Request for Information, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/news/press-releases/2024/03/ftc-hhs-extend-public-comment-period-generic-drug-shortages-competition-request-information

- AAM Submits Comments to HHS and FTC on the Impact of GPOs and Wholesalers on Access to Generic Medicines, accessed July 30, 2025, https://accessiblemeds.org/resources/press-releases/aam-response-to-ftc-hhs-rfi-on-drug-shortages/

- What’s Behind Drug Shortages and What to do About It – Third Way, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.thirdway.org/report/whats-behind-drug-shortages-and-what-to-do-about-it

- OVERVIEW SHORT-TERM RECOMMENDATIONS POLICY SOLUTIONS TO ADDRESS THE DRUG SHORTAGE CRISIS – ASHP, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.ashp.org/-/media/assets/advocacy-issues/docs/2023/ASHP-Drug-Shortage-Recommendations.pdf

- 340B Drug Pricing Program – HRSA, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.hrsa.gov/opa

- The 340B Drug pricing program – American Hospital Association, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.aha.org/system/files/media/file/2024/03/The-340B-Drug-Pricing-Program.pdf

- Comparison of Generic Prescribing Patterns Among 340B-Eligible and Non-340B Prescribers in the Medicare Part D Program – PMC – PubMed Central, accessed July 30, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10199350/

- Geographic concentration of pharmaceutical manufacturing: USP …, accessed July 30, 2025, https://qualitymatters.usp.org/geographic-concentration-pharmaceutical-manufacturing

- Domestic pharma industry may face setback if US imposes tariffs, accessed July 30, 2025, https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/business/india-business/domestic-pharma-industry-may-face-setback-if-us-imposes-tariffs/articleshow/123002989.cms

- Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient [API] Market Size, Share, 2032, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.fortunebusinessinsights.com/active-pharmaceutical-ingredient-api-market-102656

- About Warning and Close-Out Letters – Warning Letters – FDA, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/inspections-compliance-enforcement-and-criminal-investigations/warning-letters/about-warning-and-close-out-letters

- The New Supply Chain Quandary: Just-in-Case Needs vs Just-in …, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.concordancehealthcare.com/blog/the-new-supply-chain-quandary-just-in-case-needs-vs-just-in-time-delivery

- Gaps in the Global Medical Supply Chain – NCBI, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK525655/

- Trends in Drug Shortages and ANDA Approvals in the U.S. – IQVIA, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.iqvia.com/insights/the-iqvia-institute/reports-and-publications/reports/trends-in-drug-shortages-and-anda-approvals-in-the-us

- The impacts of medication shortages on patient outcomes: A …, accessed July 30, 2025, https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0215837

- Empty Shelves, Full of Frustration: Consequences of Drug Shortages and the Need for Action – PMC, accessed July 30, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3847976/

- Coalition Working to End Drug Shortages, Together – Vizient Inc., accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.vizientinc.com/insights/all/2022/coalition-working-to-end-drug-shortages-together

- The Recurring Problem of Drug Shortages—How Do We Overcome It? – PMC, accessed July 30, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8432384/

- Factors Involved in U.S. Generic Drug Shortages – U.S. Pharmacist, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.uspharmacist.com/article/factors-involved-in-us-generic-drug-shortages