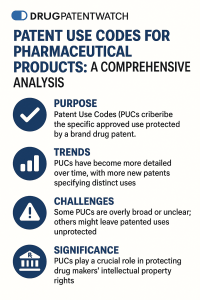

Introduction: More Than Just a Code, A Linchpin of Pharmaceutical Strategy

In the pharmaceutical industry few elements are as seemingly mundane yet strategically potent as the patent use code. To the uninitiated, it is a simple alphanumeric identifier, a piece of administrative data tucked away in the vast database of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations—better known as the Orange Book.1 But to those who navigate the complex interplay of drug development, patent law, and market competition, these codes are far more. They are the very language of market access, the legal tripwires in patent disputes, and the central battlefield where the multi-trillion-dollar tension between pharmaceutical innovation and affordable healthcare is fought daily.3

At their core, patent use codes are standardized descriptors that link a specific patent to an FDA-approved method of using a drug, such as treating a particular disease, following a specific dosing regimen, or targeting a defined patient population.1 Born from the landmark Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984, or the Hatch-Waxman Act, they were designed to bring clarity to a complex system, creating a pathway for generic drug manufacturers to enter the market without infringing on valid method-of-use patents. Yet, what was intended as a tool for clarity has evolved into a sophisticated instrument of strategy, wielded by both innovator (brand) and generic companies to shape market dynamics and control billions of dollars in revenue.

The stakes are immense. The strategic manipulation and litigation surrounding these codes are not abstract legal exercises; they have profound real-world consequences. It is estimated that the strategic misuse of the patent and use code system imposes an additional $3.5 billion per year in excess healthcare costs in the United States alone, a staggering figure that underscores the economic power embedded in these brief descriptions. How can such a small piece of data carry such weight? Because it governs the timing of generic competition, the single most powerful force in reducing prescription drug prices.

This report will dissect the world of patent use codes from the ground up, moving beyond simple definitions to provide a comprehensive analysis for the strategic decision-maker. We will begin by exploring the foundational legal framework of the Hatch-Waxman Act and the operational mechanics of the Orange Book, establishing the regulatory bedrock upon which this entire system is built. From there, we will enter the strategic battlefield, examining the innovator’s playbook of “evergreening” and the generic’s counter-gambit of “skinny labeling.” We will then turn to the courtroom, conducting a deep dive into the landmark legal precedents—from Caraco v. Novo Nordisk to the game-changing GSK v. Teva—that have defined and redefined the rules of engagement.

Recognizing that the pharmaceutical world is not monolithic, we will dedicate a significant portion of our analysis to the distinct and often more opaque landscape of biologics and biosimilars, contrasting the BPCIA’s “patent dance” with the Hatch-Waxman framework. Finally, we will look to the future, analyzing the current wave of regulatory reform, the unprecedented collaboration between the FDA, USPTO, and FTC, and the actionable intelligence that can be gleaned from this complex data. For the business leaders, legal counsel, and investors seeking to turn regulatory complexity into competitive advantage, understanding the power and nuance of the patent use code is no longer optional—it is essential for survival and success.

Part I: The Regulatory Bedrock – Understanding the System

To master the strategic application of patent use codes, one must first understand the architecture of the system in which they operate. This regulatory framework, a product of decades of legislative compromise and judicial interpretation, is built upon three pillars: the foundational Hatch-Waxman Act, the central role of the FDA’s Orange Book, and the specific mechanics of the use code itself.

The Hatch-Waxman Compromise: Birth of the Modern Generic Market

The world of pharmaceutical competition as we know it today was forged in 1984 with the passage of the Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act, universally known as the Hatch-Waxman Act.3 It was a grand legislative bargain, a carefully constructed compromise designed to resolve two diametrically opposed, yet equally valid, public policy interests: the need to incentivize the costly and risky process of new drug innovation, and the urgent demand for access to more affordable medicines.

Before 1984, the landscape was starkly different and heavily favored innovators. A generic company wishing to market a copy of an approved drug faced a monumental hurdle: it had to conduct its own expensive and time-consuming clinical trials to independently prove the drug’s safety and efficacy.5 This created a formidable barrier to entry, meaning that even long after a drug’s patent had expired, affordable generic alternatives were rare. The Hatch-Waxman Act dismantled this barrier with a revolutionary concept.

For generic manufacturers, the Act’s greatest gift was the creation of the Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) pathway.4 This streamlined process allowed a generic company to rely on the innovator’s original safety and efficacy data. Instead of repeating clinical trials, the generic applicant needed only to demonstrate that its product was “bioequivalent” to the innovator’s Reference Listed Drug (RLD)—meaning it acted in the same way in the human body.4 This single change dramatically lowered the cost and time required to bring a generic to market, effectively giving birth to the modern generic drug industry.

But this was only one side of the bargain. To secure the support of the innovator pharmaceutical industry, the Act offered significant new protections to compensate for the new competitive threat. First, it provided a mechanism for Patent Term Extension (PTE), allowing brand-name companies to restore a portion of the patent life that was lost during the lengthy FDA regulatory review process. Second, and just as importantly, it created new forms of non-patent market exclusivity. These regulatory exclusivities, which run independently of patents, provided guaranteed periods of market protection. The most significant of these are the five-year New Chemical Entity (NCE) exclusivity for drugs containing a new active ingredient, and the three-year exclusivity for new clinical investigations that support a change to a previously approved drug, such as a new indication or dosage form.5

Crucially, the Hatch-Waxman Act did not just create parallel benefits for each side; it inextricably linked the FDA approval process with the patent system.8 It established a formal framework for resolving patent disputes

before a generic drug could be launched, a system designed to provide a degree of predictability and order to the inevitable conflicts. This linkage is the very reason the Orange Book and patent use codes exist. The Act, in its attempt to foster competition, simultaneously created the very incentives that would lead to the sophisticated strategies of patent lifecycle management. With a clear and predictable pathway for generic entry now established, innovators were driven to develop new ways to defend their market share beyond the life of a single, primary patent. This made secondary patents—those covering new methods of use, formulations, or dosing regimens—more valuable than ever, setting the stage for the strategic gamesmanship that would come to define the industry.

Decoding the Orange Book: The Central Registry for Pharmaceutical Patents

If the Hatch-Waxman Act is the constitution of the pharmaceutical patent system, the Orange Book is its central public ledger. Officially titled Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations, this FDA-maintained publication is the linchpin that connects the worlds of drug approval and patent law.2 Its purpose is twofold: to inform healthcare professionals about which generic drugs are therapeutically equivalent to brand-name products, and to provide a transparent registry of the patents and exclusivities that protect those brand-name drugs.10 For the system to function as Congress intended, the accuracy and comprehensiveness of the Orange Book are paramount.

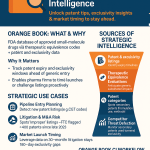

The database is a rich source of information, containing several key data files for each approved drug. These include:

- Drug Listings: Information on the drug itself, such as its active ingredient, dosage form, strength, and the application holder. It distinguishes between New Drug Applications (NDAs) for innovator products and ANDAs for generics.

- Therapeutic Equivalence (TE) Codes: These codes, such as the common “AB” rating, indicate whether a generic drug is considered therapeutically equivalent to its brand-name counterpart and can be automatically substituted by a pharmacist.4

- Patent Listings: This is the core of the Orange Book for patent litigation purposes. For each NDA, the innovator must list relevant patents, which are categorized as claiming the drug substance (the active ingredient), the drug product (the formulation or composition), or a method of using the drug.4

- Exclusivity Data: The Orange Book also tracks the expiration dates of any non-patent regulatory exclusivities the drug has been granted, such as NCE or pediatric exclusivity.4

Just as important as what is included is what is explicitly excluded. FDA regulations state that patents covering manufacturing processes, packaging, metabolites (the substances a drug breaks down into in the body), or intermediates (chemicals used in the manufacturing process) are not eligible for listing in the Orange Book.4 This distinction is a frequent source of dispute, as innovators may attempt to list patents that blur these lines to create additional hurdles for generic competitors.

Perhaps the most critical—and controversial—aspect of the Orange Book is the FDA’s role in its maintenance. The agency has long maintained that its role in listing patents is purely “ministerial”.8 This means the FDA does not substantively review the patents submitted by an NDA holder to verify their accuracy or relevance to the approved drug. It simply publishes the information that the company provides, as long as the submission forms are filled out correctly. The FDA’s position is that it lacks the legal authority, resources, and patent law expertise to act as an arbiter of patent scope.

This “ministerial” stance creates a structural vulnerability in the system. It effectively outsources the gatekeeping of patent listings to the very entity that has the strongest financial incentive to list as many patents as possible, whether appropriate or not. The commercial benefit of listing a patent—namely, the ability to trigger an automatic 30-month stay of generic approval upon filing a lawsuit—is immense, while the historical downside for an improper listing has been minimal.15 This systemic bias places the burden of policing the Orange Book squarely on generic challengers, who must resort to costly litigation or the formal dispute process established by the Orange Book Transparency Act of 2020 to correct inaccuracies.2 The recent and aggressive wave of challenges by the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) against what it deems “improperly listed” patents is a direct response to this long-standing vulnerability, signaling that other government bodies are now stepping in to fill the regulatory vacuum left by the FDA’s hands-off approach.15

Anatomy of a Patent Use Code: Structure, Submission, and Best Practices

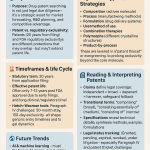

Within the Orange Book’s patent listings, the use code is the specific mechanism for describing method-of-use patents. It is the narrative link between a patent’s legal claims and a drug’s real-world application. Understanding its structure and the rules governing its creation is fundamental to grasping its strategic importance.

A typical patent use code is a short, descriptive statement that contains three core elements :

- Identifier: A unique alphanumeric code assigned by the FDA, always beginning with a “U-” prefix followed by a number (e.g., U-1234).

- Indication: The core description of the disease or condition the patented method is used to treat (e.g., “treatment of moderate-to-severe rheumatoid arthritis”).

- Limitations: Further qualifiers that narrow the scope of the use, such as specific patient populations (“in adults failing DMARD therapy”), dosing parameters (“administering 100mg daily”), or requirements for use in combination with other therapies.

The process for getting a use code into the Orange Book is highly formalized. When an innovator company submits a New Drug Application (NDA), or after a new patent is issued for an already-approved drug, it must submit all relevant patent information to the FDA on a specific form—Form 3542 or 3542a.7 This submission must be made within 30 days of the drug’s approval or the patent’s issuance to be considered “timely filed,” a status that has important implications for litigation against pending generic applications.7

On this form, the NDA holder provides the patent number, its expiration date, and, for method-of-use patents, the proposed text of the use code. Federal regulations, specifically 21 CFR §314.53, lay out strict requirements for this description. The regulation mandates that the use code must describe “only the specific approved method of use claimed by the patent” and requires the company to “identify with specificity the section(s) and subsection(s) of the approved labeling” that correspond to that patented use.19 This requirement to pinpoint the exact language in the drug’s label is intended to prevent companies from drafting overly broad or ambiguous codes that don’t align with what the patent actually protects.

Best Practices for Drafting Effective and Defensible Use Codes

The drafting of a patent use code is not a simple administrative task; it is a high-stakes legal and strategic exercise. For the innovator, the objective is to craft a description that accurately reflects the patent claims and provides the broadest possible protection against generic carve-outs without being so overreaching that it becomes vulnerable to a legal challenge. For the generic company, scrutinizing that language for any sliver of imprecision is the key to unlocking a potential early market entry pathway.

The history of litigation has established several best practices and critical considerations for this process. First and foremost is the meticulous alignment of three documents: the patent claims, the FDA-approved drug label, and the use code itself. The Supreme Court’s decision in Caraco, which affirmed that use codes are legally significant “patent information” central to the FDA’s regulatory process, solidified the need for this precision. Any disconnect between these three elements can be exploited by a challenger.

Second, drafters must be wary of using what litigators call “patent profanity”—words that unnecessarily limit the scope of the description. Terms like “essential,” “necessary,” “must,” or “only” can be used by an opposing party to argue for a narrower interpretation than intended, potentially creating a loophole for a generic to design around.

Third, the regulatory landscape has shifted decisively toward specificity. The FDA’s 2021 guidance, issued as a direct response to years of litigation over ambiguity, now explicitly requires use codes to mirror the exact language of the drug’s label and prohibits the use of vague “mechanism of action” claims (e.g., “inhibits the JAK-STAT pathway”) in place of a specific, approved clinical use. This evolution reveals a clear trend: the FDA, prodded by the courts and other agencies, is slowly moving away from its historically deferential stance and is now more actively enforcing the original intent of the Hatch-Waxman Act. This regulatory tightening was not a proactive measure but a reaction forced by years of industry’s strategic use of ambiguity, the resulting costly litigation, and sustained criticism from government watchdogs like the Government Accountability Office (GAO).8 Innovators who fail to adapt to this new era of required precision do so at their own peril, as a poorly drafted use code is no longer just a procedural filing but a potential invitation for a successful generic challenge.

Part II: The Strategic Battlefield – Use Codes in Action

With the regulatory framework established, we now turn to the dynamic application of these rules. The patent use code system is not a static library of information but an active battlefield where innovator and generic companies deploy sophisticated strategies to gain commercial advantage. This section explores the offensive playbook of innovators, the defensive counter-moves of generics, and the resulting high-stakes litigation that defines the competitive landscape.

The Innovator’s Playbook: Strategic Use and Abuse of Patent Use Codes

For innovator pharmaceutical companies, the period of market exclusivity is the lifeblood of their business model, allowing them to recoup the billions of dollars invested in research and development. Consequently, a core business strategy is “lifecycle management,” which involves legally and strategically extending a drug’s monopoly for as long as possible. The patent use code has become a primary tool in this endeavor, with certain tactics pushing the boundaries of the Hatch-Waxman framework in a practice critics label “evergreening” or the creation of “patent thickets”.23

The Proliferation of Use Codes: A Quantitative Look

One of the most telling indicators of this strategic shift is not just the content of use codes, but their sheer number. A recent, revealing analysis by STAT News quantified this trend, exposing a dramatic escalation in the deployment of use codes as a competitive tactic.

This exponential growth, particularly in the number of codes per drug, points to a deliberate strategy. It is no longer about listing a single patent for a single new use; it is about creating a dense web of overlapping claims to deter competition. The analysis highlighted several egregious examples that illustrate the scale of this practice:

- Cycloset, a treatment for type 2 diabetes, was associated with an astonishing 116 different use codes filed 122 times across just 12 patents.

- Imbruvica, a cancer therapy, had 41 active patents but was linked to 407 use codes in the Orange Book.

This proliferation is a strategic choice. Adding a range of similar use codes is substantially cheaper and easier than prosecuting entirely new patents, yet it can achieve a similar goal: making it more difficult and costly for a generic rival to navigate the patent landscape and successfully litigate a challenge. The explosion in the number of use codes per drug is a powerful proxy for a company’s aggressive lifecycle management strategy. It signals a shift from relying on the strength of a few core patents to a strategy of deterrence through complexity. For a generic competitor or an investor, a high use code count is a clear red flag, indicating a higher probability of protracted and expensive litigation. A 2023 study in JAMA confirmed this correlation, finding that drugs with three or more use codes faced 78% more litigation than those with only one or two, delaying generic market entry by an average of 4.2 years.

Common “Evergreening” Tactics Involving Use Codes

The increase in the quantity of use codes is driven by several specific tactics designed to maximize their defensive power:

- Drafting Overly Broad or Ambiguous Codes: This is the classic tactic. By using vague language that does not precisely map to the patent claims or the drug label, an innovator can create uncertainty for a generic company attempting to design a “skinny label” carve-out. If the boundaries of the patented use are unclear, it becomes nearly impossible for a generic to prove to the FDA that its proposed label does not overlap, often forcing them into litigation.22

- “Umbrella” Codes: This involves crafting a single, broad use code that appears to cover multiple distinct indications or patient populations. Even if the underlying patent only strongly supports one of these uses, the broad code can create a barrier to entry for all of them, forcing a generic to challenge the validity of the code’s scope in court.

- “Product Hopping” and Secondary Patents: A cornerstone of evergreening is the filing of new patents for minor modifications to a drug as its primary patent nears expiration. These can include patents on a new extended-release formulation, a different dosage strength, or a new combination product. Each of these new patents is then listed in the Orange Book with its own set of use codes, effectively resetting the patent clock and creating new hurdles for generics.25

- Late Listing and Strategic Revisions: The timing of a use code’s appearance can be a strategic weapon. Innovators have been known to revise existing use codes or list new ones during the course of active litigation with a generic challenger. This can force the generic to amend its ANDA filing and can introduce new complexities and delays into the legal proceedings. Data shows that between 2015 and 2022, a significant 37% of all Orange Book patent listings were revised after their initial submission, often to expand the scope of the use code during a dispute.

These tactics, taken together, transform the use code system from a source of clarity into a minefield for generic competitors, demonstrating how a regulatory tool can be repurposed into a powerful instrument for extending a commercial monopoly.

The Generic’s Gambit: “Skinny Labeling” and the Section VIII Carve-Out

Faced with the innovator’s formidable playbook, the primary strategic response for a generic manufacturer is the “skinny label.” This mechanism, formally known as a “Section viii statement,” is the main pathway provided by the Hatch-Waxman Act for a generic to enter the market for a drug’s non-patented uses while a method-of-use patent for other indications is still in force.3 It is a powerful tool for promoting timely competition, but its success is entirely contingent on the clarity of the innovator’s patent use codes.

The process works as follows: when a generic company files its ANDA, instead of challenging a method-of-use patent with a Paragraph IV certification, it can submit a Section viii statement. This statement is a declaration to the FDA that the generic company is not seeking approval for the specific method of use that is protected by the patent.3 To accompany this statement, the generic applicant submits a proposed product label from which all information related to the patented use—the indications, dosing instructions, and clinical data—has been “carved out.” The resulting label is “skinnier” than the brand-name drug’s label.26

The FDA’s role is to compare the proposed skinny label with the innovator’s patent use code listed in the Orange Book. If the agency determines that the carve-out is successful—meaning the language on the skinny label does not overlap with the description in the use code—and that the removal of the information does not compromise the drug’s safety or efficacy for the remaining indications, it can approve the generic for marketing.6

The importance of this pathway cannot be overstated. Data from 2015 to 2019 shows that approximately half of all new generic drugs that were launched for products with multiple indications and existing use patents entered the market via a skinny label.28 This demonstrates that the Section viii carve-out is not a niche exception but a mainstream strategy that is critical for introducing competition for some of the most widely used medicines.

However, the viability of this strategy is a double-edged sword. It hinges entirely on the precision of the use code drafted by the innovator. This creates a fascinating strategic paradox: a brand company that drafts a clear, narrow, and accurate use code to robustly protect its intellectual property is, in fact, providing a perfect and unambiguous roadmap for a generic competitor to follow to launch an early, non-infringing product. Conversely, an innovator that drafts a vague and overbroad use code in an attempt to block all generic entry creates a legal vulnerability. While this may deter some generics, it also invites a legal challenge under the precedent set by Caraco v. Novo Nordisk, where a court could force the innovator to correct the code. This interdependency places the innovator’s drafting choice at the center of the strategic cat-and-mouse game, where the language of the use code directly dictates the timeline and level of risk for its first generic competitor.

When Strategies Collide: Paragraph IV Challenges and Hatch-Waxman Litigation

When a skinny label is not a viable option—either because the innovator’s patents cover all approved uses of a drug or because the use codes are too ambiguous to navigate—a generic manufacturer must take a more confrontational approach. This involves a direct challenge to the innovator’s patents through a “Paragraph IV certification”.3 This filing is the formal trigger for the high-stakes litigation framework established by the Hatch-Waxman Act.

A Paragraph IV certification is a statement within a generic’s ANDA asserting that a patent listed in the Orange Book for the brand-name drug is either invalid, unenforceable, or will not be infringed by the generic product. The Hatch-Waxman Act ingeniously defines the mere act of filing a Paragraph IV certification as an “artificial act of infringement.” This legal fiction allows the innovator to sue the generic for patent infringement immediately, long before the generic product ever reaches the market, setting the stage for pre-launch patent resolution.

The process is governed by strict timelines. After the FDA accepts its ANDA, the generic company must send a notice letter to the innovator and patent holder, detailing the basis for its Paragraph IV certification. The innovator then has a critical 45-day window to respond by filing a patent infringement lawsuit.3

If a lawsuit is filed within this 45-day period, it triggers one of the most powerful tools in the innovator’s arsenal: the automatic 30-month stay of FDA approval.3 This provision prevents the FDA from granting final approval to the generic’s ANDA for up to 30 months, or until the patent dispute is resolved in court, whichever comes first. This stay provides a guaranteed, lengthy period for the innovator to litigate its patent rights without facing immediate generic competition.

This 30-month stay has evolved from a procedural safeguard into a primary strategic weapon. The mere act of listing a patent in the Orange Book, combined with the willingness to file a lawsuit, can secure a two-and-a-half-year delay in competition. This creates a powerful incentive for innovators to list any patent that is even tangentially related to the drug, as the commercial reward of the stay is immediate and substantial. The FTC has repeatedly raised concerns that this mechanism is being abused, with companies listing patents improperly simply to trigger the stay and block competition.15 The agency’s recent enforcement actions are a direct attempt to curb this practice by increasing the risk and potential penalties for such “improper listings.”

To counterbalance this powerful tool and encourage generics to undertake the risk and expense of patent litigation, the Hatch-Waxman Act includes a significant incentive. The first generic company to file a substantially complete ANDA with a Paragraph IV certification is eligible for a 180-day period of marketing exclusivity.7 During this six-month period, the FDA cannot approve any other generic versions of the same drug. This temporary duopoly with the brand-name drug is often the most profitable period for a generic product, making the “first-to-file” status a highly coveted prize that fuels the race to challenge patents. This entire framework—the Paragraph IV challenge, the 30-month stay, and the 180-day exclusivity—creates a structured but intensely competitive and litigious environment where the interpretation of patents and their corresponding use codes is fought over with billions of dollars on the line.

Part III: The Gavel Falls – Landmark Legal Precedents

The strategic battlefield of patent use codes is not governed solely by regulations; its contours have been dramatically shaped by pivotal court decisions. The judiciary, from federal district courts to the Supreme Court, has been called upon to interpret the often-ambiguous language of the Hatch-Waxman Act and to balance the competing interests it represents. Two cases, in particular, stand as pillars of modern use code jurisprudence: Caraco v. Novo Nordisk, which empowered generics to fight back against overreach, and GSK v. Teva, which created a new and formidable risk for those employing the skinny label strategy.

Opening the Door: Caraco v. Novo Nordisk and the Right to Challenge

The 2012 Supreme Court decision in Caraco Pharmaceutical Laboratories, Ltd. v. Novo Nordisk A/S was a watershed moment that fundamentally shifted the balance of power in use code disputes.6 Before this ruling, generic companies were often stymied by innovator-drafted use codes that were intentionally broad or inaccurate. A brand company could list a use code that swept in unpatented uses, effectively blocking a generic’s ability to pursue a skinny label, and the generic had little recourse to correct the listing. The

Caraco decision provided that recourse.

The case centered on Novo Nordisk’s diabetes drug, Prandin (repaglinide), which was approved for three uses. Novo Nordisk held a patent that covered only one of those uses: using the drug in combination with metformin. Initially, its use code accurately reflected this. However, after Caraco filed an ANDA and proposed a skinny label for the two unpatented uses, Novo Nordisk submitted a revised, much broader use code to the FDA, stating the patent covered “a method for improving glycemic control in adults with type 2 diabetes”—language that encompassed all three approved uses. This new, overbroad code now overlapped with Caraco’s proposed label, and the FDA, in its ministerial capacity, refused to approve the skinny label.

Caraco was trapped. It sued, arguing that the Hatch-Waxman Act’s counterclaim provision—which allows a generic to assert that a patent is invalid or not infringed—should also allow it to challenge the accuracy of the use code itself. The case made its way to the Supreme Court, which sided unanimously with Caraco.

The Court’s holding was clear and powerful. It ruled that a generic manufacturer, when sued for patent infringement, can file a counterclaim to “force correction of a use code that inaccurately describes the brand’s patent as covering a particular method of using the drug”. The justices recognized that use codes are not mere suggestions but are “pivotal” to the functioning of the skinny label pathway. An inaccurate code, the Court reasoned, “throws a wrench into the FDA’s ability to approve generic drugs as the statute contemplates”. By affirming that use codes are a form of “patent information” subject to the statute’s counterclaim provision, the Supreme Court handed generic companies a vital tool to police the Orange Book and combat one of the most effective tactics of innovator overreach.

While a landmark victory, the Caraco decision inadvertently set the stage for the next phase of strategic evolution. By making overtly broad use codes legally vulnerable, it pushed innovator companies toward more subtle and sophisticated strategies. The focus shifted from defending a single, overbroad code to creating a complex web of numerous, more narrowly defined codes and, most importantly, to a new legal theory of attack: induced infringement. This evolution in innovator strategy would ultimately lead to the next defining legal conflict in the skinny label saga.

The Chilling Effect: A Deep Dive into GSK v. Teva and Induced Infringement

If Caraco opened a door for generics, the Federal Circuit’s decision in GlaxoSmithKline LLC v. Teva Pharmaceuticals USA, Inc. threatened to slam it shut. The 2021 ruling, which upheld a staggering $235 million jury verdict against Teva, sent shockwaves through the industry by dramatically increasing the perceived risk of the skinny label strategy.13 The case revolved around the legal doctrine of “induced infringement,” which holds a party liable if they actively encourage another party (in this case, doctors) to infringe a patent.

The dispute concerned the heart medication carvedilol, marketed by GSK as Coreg®. GSK held a patent on a method of using carvedilol to decrease mortality from congestive heart failure (CHF). Teva sought to market a generic version and used a skinny label, carving out the CHF indication from its label while seeking approval for other uses, such as hypertension and left ventricular dysfunction (LVD) following a heart attack. On its face, Teva appeared to have complied with the requirements of a Section viii carve-out.

However, GSK’s legal strategy was brilliant and devastating. At trial, GSK argued that Teva was still inducing infringement through a combination of factors. First, they presented evidence that LVD is a form of CHF, meaning that a doctor prescribing Teva’s generic for the “approved” LVD indication would inherently be treating CHF, the patented use. Second, and more broadly, GSK pointed to Teva’s marketing materials, press releases, and product catalogs, which referred to its product as the “generic Coreg®” and highlighted its “AB-rated” status, signifying it was therapeutically equivalent to the brand.13 GSK argued that this totality of communication encouraged doctors to view Teva’s product as fully substitutable for Coreg® for all its uses, including the patented CHF indication.

A jury agreed, and a divided panel of the Federal Circuit ultimately affirmed the verdict. The majority opinion held that substantial evidence supported the jury’s finding of inducement. The court looked beyond the literal text of the carve-out on the label to the “totality of the circumstances,” concluding that Teva’s actions, taken as a whole, demonstrated an intent to encourage the infringing use.13

The decision created what has been widely described as a “chilling effect” on the generic industry. It suggested that even a perfectly executed skinny label, approved by the FDA, could not shield a generic company from a massive infringement verdict. Routine marketing activities, such as promoting a product as a “generic equivalent,” could now be used as evidence of a culpable intent to induce infringement. This ruling weaponized the FDA’s own therapeutic equivalence rating system against generics. The “AB” rating, which is a regulatory necessity for automatic pharmacy substitution and commercial viability, was twisted into evidence of Teva’s intent to infringe. This created a perilous “catch-22”: a generic needs the AB rating to compete, but advertising that very rating could expose it to hundreds of millions of dollars in liability. The uncertainty and immense financial risk introduced by this precedent have led to a demonstrable decline in the use of the skinny label pathway, a direct consequence of this game-changing judicial interpretation.

Navigating the Aftermath: The Evolving Risk Calculus for Skinny Labels

In the years following the GSK v. Teva decision, the risk calculus for generic manufacturers considering a skinny label strategy has been fundamentally altered. The once-reliable pathway for early market entry is now viewed as a legal minefield, forcing companies to weigh the potential profits of a launch against the catastrophic risk of an induced infringement verdict.

The most immediate and quantifiable impact has been a sharp decline in the use of skinny labels. A 2025 study published in the Journal of Managed Care & Specialty Pharmacy tracked first generic entrants from 2021 to 2023. It found a clear downward trend in the percentage of susceptible drugs launching with a skinny label: the figure dropped from 56% in 2021, the year of the Federal Circuit’s final decision, to 43% in 2022, and then plummeted to just 20% in 2023.28 This data provides compelling evidence of the “chilling effect,” suggesting that many generic companies are now opting to wait for all patents to expire rather than risk a

GSK v. Teva-style lawsuit.

Subsequent court cases have reinforced the precedent, solidifying the need for extreme caution. In Amarin Pharma, Inc. v. Hikma Pharmaceuticals USA Inc., the Federal Circuit again reversed a district court’s dismissal of an inducement claim against a skinny-labeled generic.39 The court reiterated that the analysis must consider the “totality” of the generic’s communications, including press releases and website content. It found that Amarin had plausibly alleged that Hikma’s marketing of its product as a “generic version of Vascepa,” combined with other statements, could encourage doctors to prescribe it for the carved-out patented use.

The legal and strategic advice flowing from these cases is now clear. Generic manufacturers must scrutinize every word on their labels and in their marketing materials. Legal counsel now advises that any language, even safety warnings or descriptions of clinical trials required by the FDA, could be used as evidence of inducement if there is any overlap with a patented method.42 The debate among patent attorneys continues, with some arguing that the legal framework remains stable and these cases are fact-specific 39, while others see a fundamental disruption that threatens the viability of the Section viii pathway.

Ultimately, the legal uncertainty created by GSK v. Teva has shifted the economic balance of power back toward the innovator. The potential for a nine-figure damages award now looms over every skinny label launch. For many generic companies, particularly smaller ones, this level of risk is simply untenable. This has the practical effect of granting innovators a de facto patent term extension, not through new innovation or legislation, but through a judicial precedent that has profoundly altered the industry’s assessment of risk.

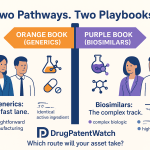

Part IV: The Biologics Exception – A Different Set of Rules

While the Hatch-Waxman Act and the Orange Book govern the world of traditional, small-molecule drugs, a separate and distinct universe of rules applies to the larger, more complex category of biologics. These medicines, derived from living organisms, and their follow-on versions, known as biosimilars, are regulated under the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA) of 2009. This framework introduces a different set of procedures, a different publication (the Purple Book), and a unique set of strategic challenges, most notably the phenomenon of “patent thickets.”

Beyond the Orange Book: The BPCIA, the Purple Book, and Biosimilars

The BPCIA was enacted as part of the Affordable Care Act to create an abbreviated approval pathway for biosimilars, analogous to the ANDA pathway for generics.45 However, due to the inherent complexity of biologics—which are large, intricate molecules produced in living cells and are impossible to replicate identically—the scientific and regulatory standards are much higher. A biosimilar must be shown to be “highly similar” to the reference product with “no clinically meaningful differences” in safety, purity, and potency.47

This scientific complexity is mirrored by a more complex and less transparent patent resolution system. The FDA’s counterpart to the Orange Book for biologics is the “Purple Book”. While it serves a similar function of listing licensed biological products, its utility as a patent resource is severely limited compared to its small-molecule cousin.46

The most critical difference is the lack of a proactive patent listing requirement. Under Hatch-Waxman, an innovator must list relevant patents in the Orange Book upon their drug’s approval. Under the BPCIA, there is no such mandate. An innovator is only required to provide patent information for listing in the Purple Book after a biosimilar developer has already filed for approval and has initiated a complex information exchange process known as the “patent dance”.50

This creates a profound informational asymmetry that heavily favors the innovator. A prospective biosimilar manufacturer must invest hundreds of millions of dollars and years of development work largely “in the dark,” with no clear, centralized public registry of the patents it will eventually have to confront. The consequences of this design are stark: as of early 2024, a comprehensive study found that only about 2% of the brand-name biologic listings in the Purple Book contained any patent information at all. This systemic lack of transparency forces biosimilar developers to make high-stakes investment decisions under conditions of extreme uncertainty, acting as a significant structural deterrent to competition before the legal process even begins.

The “Patent Dance”: A Comparative Analysis with Hatch-Waxman Litigation

At the heart of the BPCIA’s patent dispute framework is the “patent dance,” a unique, multi-step, and highly choreographed process for identifying and litigating patents.45 It is a private negotiation and information exchange that stands in stark contrast to the public, trigger-based system of Paragraph IV litigation under Hatch-Waxman.

The dance begins after a biosimilar applicant files its application with the FDA. The applicant may then choose to provide its confidential application and manufacturing information to the reference product sponsor. This kicks off a series of timed exchanges over several months, where the innovator provides a list of patents it believes could be infringed, the biosimilar applicant responds with its arguments on invalidity and non-infringement, and the innovator replies in turn. The process is designed to narrow the field of disputed patents before any litigation is filed.52

A landmark 2017 Supreme Court case, Sandoz v. Amgen, clarified a crucial aspect of this process: the patent dance is entirely optional for the biosimilar applicant.53 A biosimilar company can choose to forgo the dance altogether, which can accelerate the timeline to litigation but also exposes it to a potentially broader and more unpredictable lawsuit from the innovator.

The differences between this system and the Hatch-Waxman framework are fundamental and have massive strategic implications. The following table provides a direct comparison of the key elements of each pathway.

| Feature | Hatch-Waxman Act (Small Molecules) | Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA) |

| Patent Identification Mechanism | Public, proactive listing in the FDA’s Orange Book. Innovator must list patents upon drug approval. 56 | Private, reactive exchange via the optional “patent dance.” Patents are identified only after a biosimilar application is filed. 56 |

| Types of Patents Litigated | Primarily drug substance (active ingredient), drug product (formulation), and method-of-use patents. Process patents are generally not listed. 56 | All types of patents, with a major focus on the numerous process and manufacturing patents that are critical for biologics. |

| Trigger for Litigation | Filing of an ANDA with a Paragraph IV certification, which is an “artificial act of infringement.” 56 | Either the conclusion of the patent dance negotiations or the biosimilar’s 180-day notice of commercial marketing. 53 |

| Automatic FDA Stay | Yes. A timely lawsuit triggers an automatic 30-month stay of the generic’s approval. 56 | No. There is no automatic stay of the biosimilar’s approval. 56 |

| Innovator Exclusivity | 5 years for a New Chemical Entity (NCE); 3 years for new clinical investigations. | 12 years of data and market exclusivity for a new reference biologic. 46 |

| Follow-on Exclusivity | Yes. 180 days of market exclusivity for the first generic applicant to successfully file a Paragraph IV challenge. | No exclusivity for the first biosimilar. A period of exclusivity is available only for the first biosimilar that is deemed “interchangeable.” |

At first glance, the absence of an automatic 30-month stay in the BPCIA might seem to favor biosimilars and promote faster competition. However, this view is misleading. The reality is that the primary barrier to biosimilar entry is not a short regulatory stay but the overwhelming challenge posed by “patent thickets.”

Patent Thickets: The Unique Challenge for Biosimilar Market Entry

The term “patent thicket” refers to a dense, overlapping web of patents covering a single product, a strategy employed to deter competitors through sheer complexity and litigation cost.23 While this tactic exists for small-molecule drugs, it has become the defining feature of the biologics landscape.

The nature of biologics makes them particularly susceptible to this strategy. Because the manufacturing process is so integral to the final product, innovators can file dozens, or even hundreds, of secondary patents covering every conceivable aspect of production: the cell lines used, the nutrient media, the purification methods, the formulation, and the delivery device.60 Many of these patents are filed long after the product is first approved, creating an ever-growing legal minefield for any potential biosimilar competitor.

The scale of this problem is staggering. In U.S. biosimilar litigation, brand companies have asserted anywhere from 11 to 65 patents for a single product. The canonical example is AbbVie’s Humira (adalimumab), the best-selling drug in history. AbbVie constructed a thicket of over 100 patents around Humira, which allowed it to use litigation and settlement agreements to delay the launch of any biosimilar competitors in the U.S. for years after its primary patent expired, costing the healthcare system billions in potential savings.60

This strategy is effective because it exploits the weaknesses of both the USPTO and the BPCIA framework. The USPTO has been criticized for being too permissive in granting follow-on patents for minor inventions. The BPCIA, with its lack of a transparent, upfront patent registry and its complex “dance,” forces a biosimilar developer to confront this entire thicket at once. The cost of litigating dozens of patents can run into the tens of millions of dollars, creating an economic barrier that is often more formidable than any single patent’s legal strength.59 In this environment, the innovator’s success in delaying competition comes not from the merit of any one invention, but from the collective weight and prohibitive cost of challenging the entire portfolio.

Part V: The Path Forward – Reform, Harmonization, and Future Trends

The strategic gamesmanship surrounding patent use codes and the broader pharmaceutical patent system has not gone unnoticed. Growing public and political pressure over high drug prices has catalyzed a new era of scrutiny, leading to unprecedented collaboration among federal agencies and a wave of proposals for regulatory and legislative reform. This section examines these efforts to recalibrate the balance of the Hatch-Waxman and BPCIA frameworks, as well as how the U.S. system compares to international approaches.

A New Era of Scrutiny: The FTC, FDA, and USPTO Join Forces

For decades, the three federal agencies at the heart of the pharmaceutical patent ecosystem—the FDA, the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO), and the Federal Trade Commission (FTC)—operated largely in their own silos. This departmentalism created regulatory gaps that were skillfully exploited by industry players. However, a “whole of government” approach, spurred by President Biden’s 2021 Executive Order on Promoting Competition, has begun to change this dynamic.63

This executive order explicitly directed the agencies to work together to ensure the patent system does not unjustifiably delay generic and biosimilar competition. This has led to a series of collaborative initiatives aimed at closing loopholes and increasing transparency:

- Joint FDA-USPTO Initiatives: The two agencies have launched programs to cross-train their staff, with patent examiners receiving training on FDA resources for prior art searches and FDA reviewers learning more about the patenting process. More substantively, they are working to ensure greater consistency in the statements companies make across their patent applications and their FDA submissions, and are jointly re-evaluating policies around use codes, skinny labels, and patent term extensions.63

- Aggressive FTC Enforcement: The most dramatic shift has come from the FTC, which has moved from a position of occasional commentary to active enforcement. In September 2023, the agency issued a formal policy statement warning that it would scrutinize improper Orange Book listings as potential unfair methods of competition under the FTC Act. It quickly followed through on this threat. In November 2023, the FTC formally challenged more than 100 patents listed in the Orange Book for asthma inhalers, epinephrine autoinjectors like the EpiPen, and other drug products, asserting they were improperly listed.15

This inter-agency collaboration marks a fundamental shift in regulatory philosophy. The FTC’s actions, in particular, represent a direct challenge to the FDA’s long-held “ministerial” role regarding the Orange Book. By using its antitrust authority to police the content of the patent listings, the FTC is effectively stepping into a regulatory vacuum that critics argue has allowed anti-competitive behavior to flourish for years. This coordinated approach, where the USPTO reconsiders patent quality, the FDA tightens its listing guidance, and the FTC enforces against anti-competitive listings, represents the most significant effort to reform the system from within in a generation.

Current and Proposed Reforms: From Guidance Documents to Legislative Safe Harbors

The renewed focus on curbing patent system abuse has translated into a range of specific reforms, both enacted and proposed, aimed directly at the strategic tactics discussed throughout this report.

On the regulatory front, the FDA’s 2021 Guidance on patent submission was a significant step. By mandating that use codes must align with the exact language of the approved label and banning vague “mechanism of action” claims, the agency took direct aim at the ambiguity that had fueled so much litigation. Early data indicating a 22% reduction in use code-related litigation since its implementation suggests this move toward greater specificity is having a tangible impact.

More sweeping changes are being contemplated on the legislative front. The FDA’s Fiscal Year 2025 budget request included several ambitious legislative proposals designed to bolster generic and biosimilar competition :

- A “Skinny Labeling” Safe Harbor: This is perhaps the most significant proposal. It would amend U.S. patent law to create a statutory safe harbor, protecting a generic or biosimilar applicant from infringement liability when it uses an FDA-approved label that carves out a patented use. This is a direct legislative response to the “chilling effect” of the GSK v. Teva decision and is intended to restore the viability of the Section viii pathway.

- Amending 3-Year Exclusivity: A proposal to tighten the requirements for the valuable three-year marketing exclusivity, limiting it to situations where an applicant is actively seeking it and where the clinical data supporting it is substantial and new.

- Curbing 180-Day Exclusivity “Parking”: A proposal to amend the forfeiture provisions for 180-day exclusivity to prevent the first-to-file generic from “parking” its exclusivity—that is, settling with the brand company and agreeing not to launch, thereby blocking all other generics from entering the market.

These proposals, particularly the skinny label safe harbor, have sparked intense debate. Bills like the “Skinny Labels, Big Savings Act” have been introduced in Congress with bipartisan support, with proponents arguing they are essential to restore the balance intended by Hatch-Waxman. However, they face opposition from innovator companies and some legal experts who contend that the legislation is an overreaction—a “solution in search of a problem”—and that the Federal Circuit’s decisions in GSK v. Teva and Amarin v. Hikma were correctly decided, fact-specific cases that do not undermine the entire skinny label framework.39 This debate represents a classic dialogue between the judicial and legislative branches, with Congress considering whether to legislatively override a court’s interpretation of its statute to restore what it sees as the law’s original purpose.

Global Perspectives: How International Systems Compare and Influence the U.S.

Examining how other developed nations handle the linkage between drug approval and patent status provides valuable context and highlights the unique, litigation-heavy nature of the U.S. system. While most countries seek to balance innovation and access, their mechanisms differ significantly.

- European Union: The EU does not have a centralized, Orange Book-style system of patent linkage. Instead of standardized use codes, information about a drug’s uses is contained in its Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC). While this allows for flexibility, patent disputes are generally handled separately from the regulatory approval process and are litigated on a country-by-country basis. This decentralized approach avoids the automatic, high-stakes triggers of the U.S. system but can lead to a fragmented and less predictable legal landscape.

- Canada: Health Canada maintains a Patent Register that is conceptually similar to the Orange Book. However, the criteria for which patents can be listed are different, and the litigation process that follows a generic’s challenge has its own unique procedures and timelines.

- India: India has taken one of the most aggressive stances against evergreening. Its patent law contains a unique provision, Section 3(d), which explicitly states that a new form of a known substance is not patentable unless it demonstrates a significant enhancement in therapeutic efficacy.25 This law was famously used to deny a secondary patent to Novartis for its cancer drug Gleevec and serves as a powerful legislative tool to prevent the patenting of minor, non-innovative modifications. This approach tackles the problem at the source—patent grant—rather than through post-grant litigation.

These comparisons reveal that the high volume of use code-related litigation in the United States is not an inevitable feature of pharmaceutical regulation. It is a direct consequence of the specific policy choices embedded in the Hatch-Waxman Act: a formal, rigid “patent linkage” system that ties FDA approval directly to patent status, combined with a “ministerial” listing process and a legal framework that makes litigation the primary mechanism for resolving disputes. Other systems have chosen different paths, either by decoupling patents and drug approval to a greater degree or by implementing stricter standards for patentability to prevent disputes from arising in the first place.

Part VI: Actionable Intelligence – Turning Data into Decisions

For business leaders, legal teams, and investors in the pharmaceutical space, the complex web of regulations and litigation surrounding patent use codes is not merely an academic subject. It is a rich source of actionable intelligence. The ability to decode this data, understand its strategic implications, and integrate it into commercial and financial decision-making provides a powerful competitive advantage. This final section translates the preceding analysis into a practical framework for leveraging patent data to conduct due diligence, assess risk, and gain a strategic edge.

The Investor’s Lens: Due diligence and Risk Assessment Using Patent Data

In pharmaceutical investing, traditional financial metrics and clinical trial data tell only part of the story. The true long-term value of a company’s assets is often dictated by the strength, breadth, and durability of its intellectual property portfolio. Patent use codes and the associated Orange Book data are critical inputs for any rigorous due diligence process.11

Key Due Diligence Questions for Innovator and Generic Companies

A sophisticated investor must ask a series of targeted questions when evaluating a company’s patent position:

When Analyzing an Innovator Company:

- Portfolio Strength: How robust is the core patent protection? Is there a strong composition of matter patent, or is the company overly reliant on weaker, secondary method-of-use patents? 62

- Lifecycle Management Strategy: What is the density of the patent estate? How many use codes are listed per drug? A high number can signal an aggressive (and potentially costly) “patent thicket” defense strategy.

- Use Code Quality: How are the use codes drafted? Are they precise and narrowly tailored to the label and patent claims, or are they broad and ambiguous, inviting legal challenges?

- Litigation History: Does the company have a track record of aggressively litigating its patents? Are they known to settle early or fight through appeals? This provides insight into their strategic posture and potential legal expenditures.

- Regulatory Scrutiny: Have any of the company’s listed patents been challenged by the FTC or through the FDA’s dispute resolution process? This is a significant red flag indicating potential vulnerability.

When Analyzing a Generic Company:

- Target Selection: How does the company select its targets? Are they pursuing drugs with clear, simple patent landscapes, or are they taking on complex “thicket” challenges?

- Skinny Label Viability: For a key product in their pipeline, how clear are the innovator’s use codes? Is a low-risk skinny label strategy feasible, or will they be forced into a costly Paragraph IV challenge? 72

- Litigation Prowess: What is the company’s track record in Hatch-Waxman litigation? Have they successfully invalidated patents or won non-infringement arguments in the past?

Financial Modeling of Patent Expiration and Generic Entry

The “patent cliff”—the sharp decline in revenue an innovator drug experiences upon loss of exclusivity—is one of the most significant and predictable events in the pharmaceutical industry. Accurate financial modeling of this event is crucial for valuation, and patent use code data is a key input.

A simple model might just look at the expiration date of the last-listed patent. A sophisticated model, however, goes much deeper:

- Modeling Revenue Erosion: Upon the first generic entry, brand revenues decline precipitously. Models must account for this rapid erosion. With a single generic competitor, prices can drop by 39%; with two, 54%; and with six or more, prices can plummet by over 95%. Brand unit share can fall to as low as 16% within the first year of competition.

- Quantifying Litigation Delays: The strategic use of patents and use codes is designed to delay this cliff. Financial models must incorporate a probability-weighted analysis of potential delays. For example, the finding that drugs with multiple use codes delay generic entry by an average of 4.2 years can be used as a baseline assumption.

- Assessing Skinny Label Scenarios: For drugs with multiple indications, models should create different scenarios. What is the revenue impact if a generic can launch early with a skinny label for a smaller indication? This requires analyzing the specificity of each use code to estimate the probability of a successful carve-out.

- Valuing the 180-Day Exclusivity: For a generic company, the 180-day exclusivity period for a first-to-file challenger is a major source of value. During this period of limited competition, prices are only modestly discounted, leading to substantial profits that must be factored into any valuation of the company’s pipeline.34

By moving beyond simple patent expiration dates to a granular, use-code-level analysis, investors can build a more accurate “patent erosion timeline.” Each method-of-use patent becomes a potential barrier with a specific probability of success and a corresponding delay factor. The aggregate of these probabilities provides a much more nuanced and realistic forecast of a drug’s true loss of exclusivity (LOE) date, leading to more accurate company valuations and better-informed investment decisions.

Competitive Intelligence: Leveraging Tools Like DrugPatentWatch for Strategic Advantage

In an industry where a single patent decision can be worth billions of dollars, access to timely, accurate, and well-structured patent intelligence is not a luxury—it is a core strategic necessity. While primary source data is available from the FDA and USPTO, its volume and complexity make it difficult to analyze efficiently. This is where commercial intelligence platforms like DrugPatentWatch become indispensable tools.77

These platforms aggregate, curate, and structure data from a multitude of disparate sources—including the Orange and Purple Books, international patent offices, court dockets, and clinical trial registries—into a single, searchable, and analyzable database. For strategic decision-makers, the value of such a tool lies in its ability to provide comprehensive insights and a critical temporal advantage.

- For Generic and Biosimilar Companies: A platform like DrugPatentWatch is essential for portfolio management and opportunity identification. Users can quickly screen for drugs approaching patent expiry, analyze the complexity of their patent estates, and identify potential vulnerabilities in use codes that might allow for a skinny label strategy. It provides crucial data on litigation history, prior Paragraph IV challenges, and potential API suppliers, streamlining the entire process of selecting and developing new generic candidates.77

- For Innovator Companies: These tools are vital for competitive intelligence. Innovators can monitor the activities of generic challengers, assess their litigation track records, and stay ahead of potential threats to their key products. They can also benchmark their own patenting strategies against those of their peers and track the R&D paths of competitors by monitoring their patent filings.

- For Investors and Analysts: For the investment community, these platforms are a cornerstone of due diligence. They provide the data needed to conduct the deep-dive analysis described above, enabling users to forecast drug pipelines, assess levels of generic competition, and de-risk investments by uncovering hidden patent liabilities.62

The true competitive advantage offered by platforms like DrugPatentWatch is speed. By providing real-time monitoring and customized alerts for critical events—such as a new patent listing, a Paragraph IV filing, or the initiation of a lawsuit—they enable companies to shift from a reactive to a proactive strategic posture.79 In a world governed by strict 45-day windows and first-to-file incentives, this ability to receive and act on intelligence in hours rather than weeks can be the difference between leading a market and being left behind.

Conclusion: The Future of Pharmaceutical Competition and the Centrality of Use Codes

The patent use code, born from a legislative compromise four decades ago, has evolved far beyond its intended role as a simple descriptor. It has become a central element in the complex, high-stakes chess match of pharmaceutical competition. This analysis has traced its journey from a tool of regulatory clarity to a weapon of strategic delay, a key that can unlock early generic market entry, and a focal point of landmark litigation and sweeping regulatory reform.

As we look to the future, it is clear that the importance of the use code will only intensify. The core tension it was designed to manage—balancing the need for innovation with the demand for affordability—remains the defining challenge of the healthcare industry. The strategic manipulation of the use code system by innovator companies has proven to be a powerful tool for lifecycle management, but it has come at a significant cost to the healthcare system and has now drawn the focused attention of regulators. The ongoing “whole of government” response, with the FTC, FDA, and USPTO acting in concert, signals a new era of enforcement and a determined effort to restore the original balance of the Hatch-Waxman Act.

The legal landscape remains volatile. The precedent set by GSK v. Teva has cast a long shadow over the skinny label pathway, creating a chilling effect that has demonstrably reduced its use. The legislative proposals for a “safe harbor” represent a potential course correction, but their passage is far from certain, leaving the industry in a state of strategic uncertainty. Simultaneously, the world of biologics continues to operate under a different and less transparent set of rules, where the challenge of patent thickets presents a formidable barrier to biosimilar competition that has yet to be effectively addressed.

For all players in this ecosystem, the path forward requires a more sophisticated and integrated approach than ever before. Success will no longer be defined solely by scientific discovery in the lab, but by the masterful orchestration of regulatory, legal, and commercial strategy. Innovators must adapt to a world of heightened scrutiny, where imprecise or overly aggressive patent listing strategies carry greater risk. Generic and biosimilar manufacturers must navigate a legal landscape fraught with new perils while seeking out the opportunities that remain. And investors must learn to read the tea leaves of the Orange Book and court dockets with ever-greater nuance to accurately price risk and identify value.

At the very center of this complex, dynamic, and ever-evolving landscape lies the humble patent use code. It will continue to be the language in which battles over market exclusivity are fought, the data point that determines the timing of competition, and the regulatory linchpin upon which billions of dollars in pharmaceutical revenue and healthcare savings depend. Mastering its complexities is no longer just a legal specialty; it is a strategic imperative for anyone seeking to compete and win in the pharmaceutical industry of tomorrow.

Key Takeaways

- Centrality of Use Codes: Patent use codes are not administrative footnotes but are the core mechanism governing generic competition for patented methods of use, directly impacting market entry timelines and billions in healthcare spending.

- Strategic Weaponization: The system has been strategically leveraged by innovator companies through tactics like drafting ambiguous codes and proliferating numerous codes per drug (“patent thickets”) to delay generic competition, a practice known as “evergreening.”

- “Skinny Labeling” as a Counter-Strategy: The “Section viii carve-out,” or skinny labeling, is the primary tool for generics to market a drug for non-patented uses before all patents expire, but its viability is highly dependent on the clarity of the innovator’s use codes.

- Landmark Litigation Has Reshaped the Field: The Supreme Court’s Caraco v. Novo Nordisk decision empowered generics to challenge inaccurate use codes, while the Federal Circuit’s GSK v. Teva ruling created a “chilling effect” on skinny labeling by expanding the risk of “induced infringement” liability.

- Biologics Operate Under a Different, Less Transparent System: The BPCIA and the FDA’s Purple Book lack the proactive, transparent patent listing requirements of Hatch-Waxman, creating significant uncertainty for biosimilar developers who must contend with massive patent thickets.

- A New Era of Regulatory Scrutiny: Unprecedented collaboration between the FDA, USPTO, and FTC, combined with new FDA guidance and proposed legislation (like a “skinny label safe harbor”), signals a major push to curb anti-competitive abuses of the patent system.

- Data as a Strategic Asset: For investors, generics, and innovators, a deep analysis of patent use codes, litigation history, and regulatory data using tools like DrugPatentWatch is critical for due diligence, risk assessment, and gaining a competitive advantage.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. What is the practical difference between a “drug substance,” “drug product,” and “method-of-use” patent in the Orange Book?

These three categories define what aspect of the drug is protected. A drug substance patent covers the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) itself—the core chemical molecule. This is typically the strongest form of protection. A drug product patent covers the formulation or composition, such as an extended-release tablet, a specific combination of ingredients, or a particular dosage form. A method-of-use patent does not cover the drug itself but rather a specific, approved way of using it to treat a particular disease or condition. It is this last category that is described by patent use codes and is central to skinny label litigation.

2. Why is the FDA’s role in listing patents described as “ministerial,” and what are the consequences of this?

The FDA’s role is “ministerial” because the agency does not substantively review the patents submitted by innovator companies for accuracy or relevance before listing them in the Orange Book.8 The FDA asserts it lacks the resources and patent law expertise to do so. The primary consequence is that the system relies on the innovator’s self-certification, creating an incentive to list patents that may be weak or improperly scoped. This shifts the burden of policing the Orange Book to generic competitors and government bodies like the FTC, who must use costly and time-consuming dispute processes or litigation to remove improperly listed patents.

3. How did the GSK v. Teva decision make it riskier for generic companies to use a “skinny label”?

The GSK v. Teva decision established that a generic company could be found liable for inducing patent infringement even if it correctly “carved out” the patented use from its label. The court ruled that the “totality of the circumstances”—including marketing materials, press releases, and even the FDA-required “AB” therapeutic equivalence rating—could be used as evidence that the generic company intended for doctors to prescribe the drug for the patented (carved-out) use.13 This created a “chilling effect” by making it unclear how a generic company could market its product as an equivalent to the brand for approved uses without risking a multi-million dollar infringement verdict.

4. Why are “patent thickets” a bigger problem for biosimilars than for small-molecule generics?

Patent thickets are a greater challenge for biosimilars for three main reasons. First, biologics are far more complex than small-molecule drugs, offering many more aspects to patent (e.g., cell lines, manufacturing processes, formulations), leading to a much larger number of patents per product. Second, the BPCIA framework lacks a transparent, upfront patent registry like the Orange Book, meaning biosimilar developers often don’t know the full extent of the patent thicket until after they have already invested heavily in development. Third, process patents, which are a major component of biologic thickets, are not listed in the Orange Book but are a central feature of BPCIA litigation, adding another layer of complexity and cost.

5. What is the proposed “skinny label safe harbor,” and why is it controversial?

The proposed “skinny label safe harbor” is a legislative fix, included in the FDA’s FY 2025 budget proposals and various bills, that would amend U.S. patent law to state that an FDA-approved skinny label cannot, in and of itself, be used as evidence of induced infringement. It is a direct response to the GSK v. Teva decision, aiming to restore the viability of the skinny label pathway for generics. It is controversial because proponents argue it is necessary to correct a judicial misinterpretation that has disrupted the balance of the Hatch-Waxman Act. Opponents, primarily innovator companies and their allies, argue the legislation is an unnecessary overreach, contending that the GSK v. Teva decision was a fact-specific ruling and that the current legal framework for induced infringement is sound and should not be changed.39

References

- www.drugpatentwatch.com, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/patent-use-codes-for-pharmaceutical-products-a-comprehensive-analysis/#:~:text=Under%20this%20framework%2C%20brand%2Dname,or%20patient%20populations%5B1%5D.

- Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations | Orange Book – FDA, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-approvals-and-databases/approved-drug-products-therapeutic-equivalence-evaluations-orange-book

- Patent Use Codes for Pharmaceutical Products: A Comprehensive …, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/patent-use-codes-for-pharmaceutical-products-a-comprehensive-analysis/

- Orange Book 101 | The FDA’s Official Register of Drugs, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.fr.com/insights/ip-law-essentials/orange-book-101/

- Hatch-Waxman 101 – Fish & Richardson, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.fr.com/insights/thought-leadership/blogs/hatch-waxman-101-3/

- The U.S. Supreme Court “Cracks the Code,” Allowing Generic Drug Manufacturers Increased Access to the Market Through Skinny Labeling – Finnegan, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.finnegan.com/en/insights/articles/the-u-s-supreme-court-cracks-the-code-allowing-generic-drug.html

- Patents and Exclusivity | FDA, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/media/92548/download

- GAO-23-105477, GENERIC DRUGS: Stakeholders Views on Improving FDA’s Information on Patents, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-23-105477.pdf

- Hatch-Waxman Letters – FDA, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/abbreviated-new-drug-application-anda/hatch-waxman-letters

- Electronic Orange Book – FDA, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/fda-drug-info-rounds-video/electronic-orange-book

- Patent Listing in FDA’s Orange Book – Congress.gov, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/IF12644

- Orange Book Data Files – FDA, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-approvals-and-databases/orange-book-data-files

- GlaxoSmithKline LLC v. Teva Pharmaceuticals USA, Inc. – Food and …, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.fdli.org/2021/06/glaxosmithkline-llc-v-teva-pharmaceuticals-usa-inc/

- The Listing of Patent Information in the Orange Book – FDA, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/media/155200/download

- FTC Challenges 100+ Patents, Bringing Attention to Orange Book Patent Listing Requirements | Troutman Pepper Locke – JD Supra, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.jdsupra.com/legalnews/ftc-challenges-100-patents-bringing-2058814/

- FTC Challenges More Than 100 Patents as Improperly Listed in the FDA’s Orange Book, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/news/press-releases/2023/11/ftc-challenges-more-100-patents-improperly-listed-fdas-orange-book

- RAI Explainer: Generic Drugs, Property Rights, and the Orange Book | Perspectives on Innovation | CSIS, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.csis.org/blogs/perspectives-innovation/rai-explainer-generic-drugs-property-rights-and-orange-book

- Everything You Wanted to Know About the Orange Book But Were Too Afraid To Ask, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.thefdalawblog.com/2022/07/everything-you-wanted-to-know-about-the-orange-book-but-were-too-afraid-to-ask/

- 21 CFR 314.53 — Submission of patent information. – eCFR, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-21/chapter-I/subchapter-D/part-314/subpart-B/section-314.53

- 21 CFR § 314.53 – Submission of patent information. – Law.Cornell.Edu, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.law.cornell.edu/cfr/text/21/314.53

- Practical Considerations and Strategies in Drafting U.S. Patent Applications – Finnegan, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.finnegan.com/en/insights/articles/practical-considerations-and-strategies-in-drafting-u-s-patent.html

- DOSE OF REALITY: BRAND NAME DRUG MAKERS INCREASINGLY UTILIZING ‘USE CODES’ TO GAME PATENT SYSTEM AND BLOCK COMPETITION – CSRxP.org, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.csrxp.org/dose-of-reality-brand-name-drug-makers-increasingly-utilizing-use-codes-to-game-patent-system-and-block-competition/

- The Role of Patents and Regulatory Exclusivities in Drug Pricing …, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/R46679

- Strategic Patenting by Pharmaceutical Companies – Should …, accessed July 31, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7592140/

- Does Drug Patent Evergreening Prevent Generic Entry …, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/does-drug-patent-evergreening-prevent-generic-entry/

- The Patent Use Code Conundrum – Fish & Richardson, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.fr.com/insights/thought-leadership/articles/the-patent-use-code-conundrum/

- ‘Evergreening’ Stunts Competition, Costs Consumers… | Arnold …, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.arnoldventures.org/stories/evergreening-stunts-competition-costs-consumers-and-taxpayers

- Frequency of first generic drugs approved through “skinny labeling,” 2021 to 2023, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.jmcp.org/doi/10.18553/jmcp.2025.31.4.343

- Frequency of first generic drugs approved through “skinny labeling,” 2021 to 2023 – PMC, accessed July 31, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11953849/

- SKINNY LABELS: CHANGING SCENARIO OF INDUCED INFRINGEMENT AND PUBLIC POLICY, accessed July 31, 2025, https://digitalcommons.law.scu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1699&context=chtlj

- ANDA Section VIII Label Carve-Outs Explained – Pharmaceutical Law Group, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.pharmalawgrp.com/blog/1/anda-section-viii-label-carve-outs-explained/

- Hatch-Waxman 201 – Fish & Richardson, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.fr.com/insights/thought-leadership/blogs/hatch-waxman-201-3/