The Patent Cliff and Beyond: A Definitive Guide to Generic and Biosimilar Market Entry

Executive Summary

The transition from a branded drug monopoly to a competitive market represents one of the most significant and predictable value transfers in the global economy. This report provides a definitive analysis of the timeline, market dynamics, and strategic imperatives surrounding generic and biosimilar entry following a brand-name drug’s loss of patent protection. The analysis moves beyond a simple examination of the “patent cliff” to dissect the intricate, multi-layered ecosystem governed by a complex interplay of patent law, regulatory pathways, powerful economic pressures, and sophisticated corporate strategy.

The modern framework for pharmaceutical competition in the United States was intentionally designed as an adversarial system, a “grand bargain” codified in the Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984. This legislation created a streamlined pathway for generic approval while offering innovators new forms of protection, establishing a permanent state of strategic warfare between incumbents and challengers. The result has been a resounding success in cost containment, with generic and biosimilar medicines saving the U.S. healthcare system an estimated $3.1 trillion over the past decade and over $445 billion in 2023 alone.1

However, the landscape of competition is evolving. The straightforward patent cliffs of the past, epitomized by small-molecule blockbusters, are giving way to more complex, protracted battles. Innovator companies have developed a formidable defensive arsenal, including the construction of dense “patent thickets,” the strategic use of “pay-for-delay” settlements, and the manipulation of market access through authorized generics and “product hopping.”

Simultaneously, the rise of biologics has introduced a new frontier of competition. Biosimilars, due to their inherent scientific complexity and higher development costs, face a much steeper path to market than traditional generics. Their entry results in slower price erosion and market uptake, a dynamic further complicated by the opaque and powerful role of Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs). The financial incentives of PBMs, often tied to high list prices and substantial rebates, can create “rebate walls” that effectively block market access for lower-cost biosimilars, undermining the very competition the system was designed to foster.

This report dissects these forces through a detailed examination of the legal foundations, economic outcomes, and strategic maneuvers that define this high-stakes environment. By analyzing landmark case studies—including the archetypal patent cliff of Lipitor, the nuanced market dynamics of the specialty drug Gleevec, and the modern market access warfare surrounding Humira—this analysis provides a comprehensive playbook for understanding and navigating the future of pharmaceutical competition. As the industry faces an unprecedented “super-cliff” with over $200 billion in innovator revenue at risk by 2030, the strategic insights contained herein are more critical than ever for decision-makers across the life sciences ecosystem.3

Section 1: The Grand Bargain: Deconstructing the Framework of Pharmaceutical Competition

The entire dynamic of generic and biosimilar entry is built upon a foundational legal and regulatory framework meticulously engineered to balance two opposing, yet essential, public policy goals: incentivizing the costly and risky process of new drug innovation and ensuring broad, affordable access to medicines once that initial incentive period has passed. This framework is not a passive set of rules but an active, intentionally adversarial system that uses economic incentives to pit innovator and generic manufacturers against each other. Understanding this architecture is the first step in predicting market events.

1.1 The Symbiotic Relationship: How Patent Protection Fuels Innovation

The cornerstone of pharmaceutical innovation is the patent system. A patent, granted by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO), confers upon an inventor the exclusive right to make, use, and sell an invention for a limited period.6 For a new drug, this protection typically comes from a “composition-of-matter” patent, which covers the new molecular entity itself.7 By statute, the term of a new patent is 20 years from the date the application was filed.7

This 20-year period of market exclusivity is the fundamental economic engine of the pharmaceutical industry. It provides the necessary incentive for companies to undertake the enormous financial risk of drug development, a process that can take over a decade and cost billions of dollars. The potential for monopoly profits during the patent term allows a company to recoup its substantial research and development (R&D) investments and fund the search for future therapies.7

However, a critical distinction must be made between the statutory patent term and the “effective patent life.” The 20-year clock on a patent begins ticking from the filing date, which often occurs early in the R&D process, long before the drug is approved for sale by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Because a significant portion of the patent’s life is consumed by preclinical studies, clinical trials, and regulatory review, the actual period of market exclusivity an innovator enjoys post-approval is often much shorter, typically in the range of 7 to 10 years.7 This compressed timeline for recouping investment is a primary driver behind the aggressive strategies innovators employ to protect and extend their market exclusivity for as long as possible.

1.2 Distinguishing Protections: Patents vs. FDA-Granted Regulatory Exclusivities

While patents are the primary form of intellectual property protection, they are not the only mechanism for market exclusivity. The FDA can grant separate, distinct periods of regulatory exclusivity upon a drug’s approval. These exclusivities are granted by statute and operate independently of a drug’s patent status; they function as a regulatory barrier, preventing the FDA from approving a competing generic application for a set period, even if no patents are in force.8

Understanding the interplay between these two forms of protection is crucial for accurately forecasting generic entry. Patents can be issued or expire at any time, regardless of a drug’s approval status, and they can be challenged in court. Regulatory exclusivities, however, attach only upon FDA approval and provide a fixed, unchallengeable period of market protection.9

The main types of FDA-granted regulatory exclusivity include:

- New Chemical Entity (NCE) Exclusivity: This is a five-year period of exclusivity granted upon the approval of a drug containing an active ingredient never before approved by the FDA. This exclusivity prevents a generic manufacturer from even submitting an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) for the first four years (or five years if the ANDA does not contain a patent challenge).8

- New Clinical Investigation Exclusivity: A three-year period of exclusivity is granted for the approval of a new application or supplement that contains new clinical investigations (other than bioavailability studies) essential to the approval. This is often granted for new indications, new dosage forms, or other significant changes to a previously approved drug.8

- Orphan Drug Exclusivity (ODE): To incentivize the development of drugs for rare diseases (affecting fewer than 200,000 people in the U.S.), the Orphan Drug Act provides a seven-year period of market exclusivity for a designated orphan drug.8

- Pediatric Exclusivity (PED): This is a powerful incentive to encourage drug testing in children. If a manufacturer conducts pediatric studies in response to a written request from the FDA, an additional six months of exclusivity is added to all existing patents and regulatory exclusivities for that active ingredient.8 For a blockbuster drug, this six-month extension can be worth billions of dollars.

- Generating Antibiotic Incentives Now (GAIN) Exclusivity: This provides an additional five years of exclusivity, added to certain other exclusivities, for qualifying infectious disease products.9

These layers of protection can run concurrently or sequentially with patents, creating a complex and overlapping timeline that must be carefully deconstructed to determine the true date of potential generic competition.

1.3 The Hatch-Waxman Act: Architecture of the Modern Generic Market

Prior to 1984, the U.S. generic drug market was largely nonexistent. Generic manufacturers were shackled by a regulatory framework that required them to conduct their own duplicative, costly, and ethically questionable clinical trials to prove safety and efficacy, even though the innovator had already done so.1 This created an insurmountable barrier to entry.

The Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984, commonly known as the Hatch-Waxman Act, fundamentally reshaped this landscape through what is often described as a “grand bargain”.1 It was a masterfully crafted piece of legislation that created a symbiotic, albeit adversarial, relationship between innovator and generic firms by giving each side something it desperately needed.

- The ANDA Pathway: The centerpiece of the Act was the creation of the Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) pathway. This provision was the legislative key that unlocked the generic market. It allowed a generic manufacturer to gain FDA approval by relying on the innovator’s previously established safety and efficacy data.1 Instead of repeating clinical trials, the generic firm only needed to demonstrate two things: pharmaceutical equivalence (same active ingredient, dosage, etc.) and bioequivalence (that the drug is absorbed and acts in the body in the same way as the brand-name product).1 This dramatically slashed the time and cost of generic development, making competition economically viable.

- Patent Term Restoration (PTE): In exchange for this new competitive threat, the Act provided innovators with a mechanism to restore a portion of the patent life that was lost during the lengthy FDA review process.1 This addressed the innovator’s legitimate concern about the erosion of their effective patent life and ensured they retained a fair period of monopoly to recoup their R&D investment.

- The “Safe Harbor” Provision: A critical, and often underappreciated, component of the bargain is the “safe harbor” provision. This provision grants generic companies a limited exemption from patent infringement for activities “reasonably related to the development and submission of information” to the FDA.1 In practical terms, this means a generic company can legally begin developing its product and conducting bioequivalence studies

before the innovator’s patents expire. Without this protection, such activities would constitute patent infringement, and generic development could only begin after the last patent lapsed. This would create a significant delay between patent expiry and the actual market entry of a generic, effectively granting the innovator a de facto patent extension. The safe harbor ensures that generics can be ready for launch on the very day the patents expire.1 - The Orange Book and Patent Certifications: To operationalize this new system, the Act established the FDA’s publication, “Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations,” colloquially known as the “Orange Book”.7 The Orange Book serves as the central registry and official “battlefield map” for patent litigation. Innovator companies are required to list the patents that they believe cover their drug product or its approved methods of use.1 When a generic company files an ANDA, it must review this list and make a certification for each patent. The most consequential of these is the “Paragraph IV” (P-IV) certification, in which the generic firm asserts that the brand’s patent is invalid, unenforceable, or will not be infringed by the generic product.1 This act of defiance is the legal trigger that initiates the patent litigation process and sets the entire competitive dynamic in motion.

1.4 The Challenger’s Prize: Understanding the 180-Day Exclusivity Incentive

The Hatch-Waxman Act did not merely create a pathway for competition; it actively incentivized it. The system’s designers recognized that challenging a multi-billion-dollar corporation’s patents is a risky and expensive endeavor. To reward this risk, the Act created a powerful prize: a 180-day period of marketing exclusivity for the first generic applicant to file an ANDA containing a P-IV certification.1

This 180-day period is a crucial strategic element. It is not exclusivity against the brand-name drug, which remains on the market. Rather, it is exclusivity against all other generic applicants for the same drug.8 For six months, the first-to-file generic enjoys a lucrative duopoly with the brand. During this period, it can price its product at a significant discount to the brand—enough to capture substantial market share—but still far above the deeply discounted price that will prevail once multiple generic competitors enter the market and trigger a price war.2

This incentive structure is the engine of the entire system. It effectively deputizes generic companies to act as private attorneys general, or “sheriffs,” who are financially motivated to scrutinize and challenge potentially weak or invalid patents that stand in the way of competition.14 The resulting patent litigation is therefore not a flaw in the system but a core, intended feature. The Act was designed to be an adversarial framework, using the profit motive of generic companies to police the patent system and ensure that innovator monopolies do not extend beyond their legitimate term. The structured conflict it creates is the very mechanism by which the “grand bargain” is enforced.

| Table 1: Comparison of Market Protections for Brand-Name Drugs |

| Type of Protection |

| Composition-of-Matter Patent |

| Secondary Patents |

| New Chemical Entity (NCE) Exclusivity |

| 3-Year “Other” Exclusivity |

| Orphan Drug Exclusivity (ODE) |

| Pediatric Exclusivity (PED) |

Section 2: The Economic Shockwave: Price Erosion and Market Share Dynamics

The expiration of a blockbuster drug’s market exclusivity is not a minor event; it is a seismic shockwave that reorders the market, erases billions of dollars in revenue for the innovator, and generates massive savings for the healthcare system. The dynamics of this transition, particularly the speed and depth of price decline and market share loss, are predictable yet profound. However, a critical divergence has emerged between the classic, precipitous “patent cliff” of small-molecule drugs and the slower, more gradual “patent slope” of modern biologics.

2.1 Anatomy of the Patent Cliff: Quantifying the Financial Impact

The term “patent cliff” aptly describes the sharp, often vertical, drop in revenue that an innovator company experiences when its flagship product loses exclusivity.5 This is not a gradual erosion but an existential threat to a product’s revenue stream. For blockbuster drugs—those with annual sales exceeding $1 billion—the financial consequences are staggering. It is common for an originator drug to lose 80% to 90% of its market share and revenue within the first year of facing multi-source generic competition.5

The scale of this value transfer is immense. The pharmaceutical industry has long faced these waves of patent expirations, with one of the most famous cliffs occurring between 2011 and 2016, when iconic drugs like Lipitor and Singulair went off-patent.4 The industry is now bracing for a “super-cliff” projected between 2026 and 2030, where blockbuster drugs such as Keytruda, Opdivo, and Eliquis are set to lose protection. This event is estimated to put approximately $180 billion to $200 billion in annual pharmaceutical revenue at risk, creating intense pressure on innovator companies to replenish their pipelines, often through aggressive merger and acquisition (M&A) activity.3

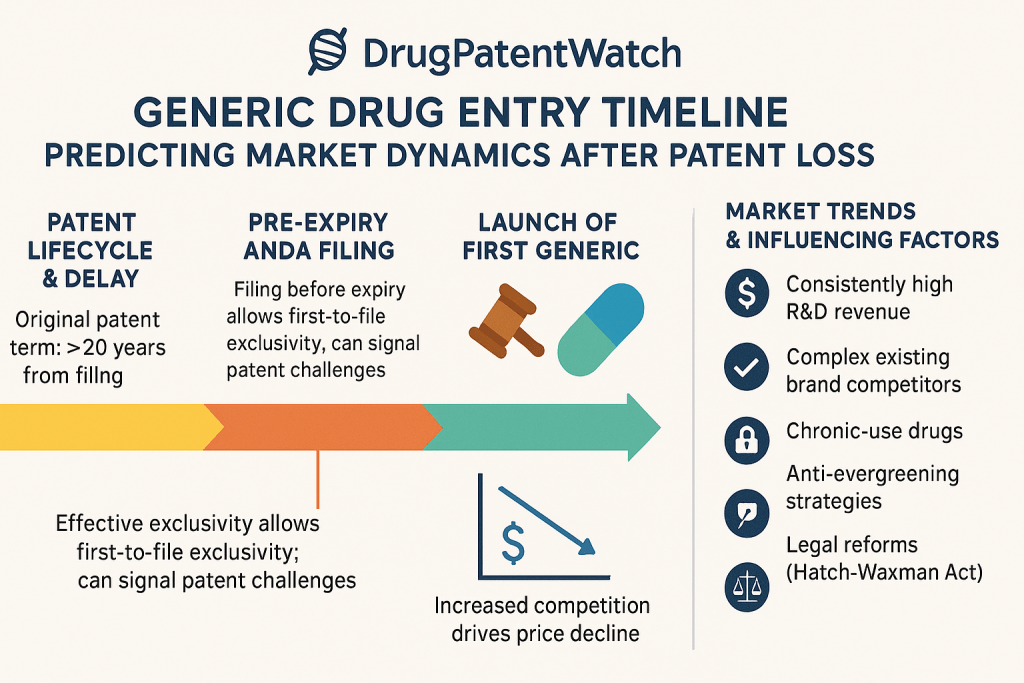

2.2 The Generic Price Erosion Curve: A Predictable Cascade

The primary driver of the patent cliff is the rapid and severe price erosion that follows generic entry. The relationship between the number of generic competitors in the market and the resulting price decline is one of the most consistent and well-documented phenomena in the pharmaceutical industry.16

The price erosion follows a predictable, stepwise cascade:

- First Generic Entrant: The entry of a single generic competitor, often operating under the 180-day exclusivity period, typically results in an initial price that is 39% lower than the brand price.11

- Second Competitor: With the entry of a second generic, competition intensifies, and the average price drops to approximately 54% below the original brand price.11

- Multiple Competitors (3-5): As more players enter the market, price becomes the primary basis for competition. With three to five competitors, prices typically fall by 70% to 80% relative to the pre-generic entry price.20

- Hyper-Competition (6+): Once six or more generic manufacturers are competing, the market dynamics shift to that of a commodity. Prices can plummet by more than 95% compared to the brand, leaving only razor-thin profit margins for the most efficient, high-volume producers.22

This process has accelerated over time. Data suggests that nearly all of the significant price reduction now occurs within the first eight to twelve months after the first generic launch, a much faster decline than was seen in the early 2000s.24

| Table 2: Small-Molecule Generic Price Erosion vs. Number of Competitors | |

| Number of Generic Competitors | |

| 1 | |

| 2 | |

| 3 | |

| 4 | |

| 6+ | |

| Source: Synthesized from FDA, ASPE, and DrugPatentWatch data.11 |

2.3 The Biosimilar Trajectory: A Slower, More Complex Path to Savings

In stark contrast to the sharp cliff of small-molecule generics, the market entry of biosimilars—the “generic” versions of complex biologic drugs—results in a much slower and shallower price decline. This “patent slope” is a direct consequence of the higher scientific, regulatory, and financial barriers to entry for biosimilars.

Initial launch prices for biosimilars are far more modest. Instead of the immediate 39% drop seen with a first generic, biosimilars typically launch with a price discount of only 15% to 35% compared to the reference biologic.3 While some biosimilars have launched with steeper discounts, particularly in highly competitive classes like adalimumab (Humira), the overall trend is one of less aggressive initial pricing.27

Even as more biosimilar competitors enter the market, the price erosion remains less severe. A recent market report found that after five years of competition, the presence of biosimilars led to an average drug cost reduction of 53%.27 While substantial, this is a far cry from the 95%+ reductions seen in mature generic markets. The pace of adoption also varies significantly by therapeutic area. For example, oncology biosimilars have seen relatively rapid uptake, capturing an average of 81% market share after five years. In contrast, immunology biosimilars have struggled, achieving only a 26% market share in the same timeframe, often due to the market access barriers discussed in Section 4.27

2.4 Market Share Realignment: How Quickly Do Originators Lose Dominance?

The efficiency of market conversion from brand to generic is a key determinant of the patent cliff’s steepness. In the U.S., this conversion is incredibly rapid for small-molecule drugs.

- Generics: Driven by state-level pharmacy substitution laws and payer incentives like tiered formularies, generic drugs capture the majority of the market almost immediately. Within 12 months of entry, generics typically command about 75% of the market share by volume. After three years, this figure often exceeds 90%.26 For blockbuster drugs, the brand’s average unit share can fall below 20% within the first year.17

- Biosimilars: The story is markedly different for biologics. Lacking widespread automatic substitution at the pharmacy level and facing significant market access hurdles, biosimilar uptake is much slower. Twelve months after market entry, biosimilars capture, at most, 40% of the market share. The average market share after three years is only 52%, with significant variability—some products achieve over 80% while others languish below 15%.26

This fundamental difference in market dynamics has profound strategic implications. The business case for developing a generic is built on the assumption of rapid, deep market penetration and high-volume sales at low margins. The business case for a biosimilar is far more complex, predicated on capturing a smaller slice of the market at a higher price point over a longer period. The higher costs and greater uncertainty of the biosimilar pathway are a direct result of the scientific complexity of biologics and the unique structure of the U.S. reimbursement system. This creates a feedback loop: high barriers to entry lead to fewer competitors, which in turn leads to slower price erosion and market uptake, making the investment case for subsequent biosimilars even more challenging.

Section 3: The Corporate Chess Match: Innovator Defense and Challenger Offense

The period leading up to and following patent expiration is not a passive event but an active, high-stakes strategic conflict. Innovator companies deploy a sophisticated and evolving arsenal of legal and commercial tactics to defend their blockbuster revenue streams, while generic and biosimilar challengers employ aggressive strategies to break through these defenses. This corporate chess match is defined by a constant cycle of action and reaction, with strategies adapting in response to legal precedents, regulatory changes, and competitor moves.

3.1 The Innovator’s Fortress: Building “Patent Thickets” to Delay Competition

One of the most powerful and controversial defensive strategies is the creation of a “patent thicket.” This is not merely the act of obtaining patents but the strategic construction of a dense, overlapping web of intellectual property rights around a single product.28 The objective is not necessarily to win a court case on the merits of any single patent but to create a litigation landscape so complex, costly, and time-consuming to navigate that would-be competitors are deterred from even attempting to enter the market.6

This strategy relies heavily on “secondary” patents filed later in a drug’s lifecycle. While the initial “composition-of-matter” patent protects the core active ingredient, secondary patents can cover a vast array of minor modifications, such as:

- New formulations (e.g., extended-release versions)

- Different methods of administration (e.g., an injectable pen)

- New manufacturing processes

- New methods of use or indications 10

The archetypal example of this strategy is AbbVie’s defense of Humira (adalimumab). AbbVie constructed a legal fortress around its blockbuster drug by filing over 247 patent applications and securing at least 132 granted patents in the U.S..29 Remarkably, approximately 90% of these patent filings were made

after Humira was already approved and on the market.31 This impenetrable wall of patents achieved its strategic goal, delaying the launch of biosimilars in the U.S. until 2023, nearly five years after they had entered the European market. This delay, driven by the patent thicket, is estimated to have cost the U.S. healthcare system billions of dollars in lost savings.32

3.2 Beyond the Thicket: Authorized Generics, Product Hopping, and Lifecycle Management

Innovators employ a range of other tactics to manage their product lifecycles and blunt the impact of generic entry.

- Authorized Generics (AGs): An authorized generic is the exact same brand-name drug, simply marketed without the brand name, either by the innovator company itself or a partner.15 Launching an AG on the first day of generic competition is a powerful strategic move. It allows the innovator to compete directly with the first-to-file generic during its 180-day exclusivity period. Because the AG can significantly erode the first-filer’s sales and profits, it can be used as a bargaining chip in settlement negotiations.34

- Product Hopping: This strategy involves making minor, often non-innovative, changes to a drug as its patent expiration nears and then shifting the market to the new, patent-protected version. For example, a company might switch from a twice-daily tablet to a once-daily capsule and heavily promote the new version to doctors and patients. By the time the generic version of the original tablet launches, a significant portion of the market has already “hopped” to the new product, leaving the generic competitor with a much smaller market to capture.6 AbbVie’s successful effort to transition many patients from Humira to its newer, patent-protected immunology drug, Skyrizi, just as Humira biosimilars were launching, is a prominent modern example of this tactic.36

- Other Delay Tactics: Innovators have also been known to employ other strategies to create friction in the generic approval process. These include filing “citizen petitions” with the FDA, which raise questions about the safety or bioequivalence of a potential generic, often forcing the agency to delay approval while it investigates the claims. While the FDA approves very few of these petitions, the review process itself can cause delays.30 Another tactic involves using restricted distribution programs to prevent generic companies from obtaining the samples of the brand-name drug they legally need to conduct their bioequivalence studies.30

3.3 The Antitrust Tightrope: “Pay-for-Delay” Settlements and the FTC v. Actavis Legacy

Perhaps the most scrutinized defensive tactic is the “pay-for-delay” or “reverse payment” settlement. This occurs when, in the course of patent litigation, the brand-name manufacturer (the plaintiff) pays the generic challenger (the defendant) to settle the case, drop its patent challenge, and agree to delay its market entry for a specified period.35

These agreements are highly controversial because they can be a “win-win” for the two companies at the expense of consumers. The innovator preserves its monopoly profits for longer, and the generic company receives a share of those profits without having to compete. The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) has estimated that these deals cost American consumers $3.5 billion per year and, on average, delay generic entry by nearly 17 months compared to settlements that do not involve a payment.35

The legal landscape for these agreements was transformed by the landmark 2013 Supreme Court decision in FTC v. Actavis, Inc..38 The Court rejected the notion that these settlements were immune from antitrust law as long as the delayed entry was within the patent’s original term. It ruled that such agreements, particularly those involving a “large and unjustified” payment, could be subject to antitrust scrutiny under the “rule of reason”.38

The Actavis decision did not make all such settlements illegal, but it opened the door for the FTC and private parties to challenge them. This has led to an evolution in settlement tactics. While large, explicit cash payments have become less common, the practice has shifted to more subtle and complex forms of value transfer that are harder for regulators to detect and challenge. These can include a brand company’s promise not to launch an authorized generic (a “No-AG” commitment), which can be worth hundreds of millions of dollars to the first-filing generic, or other valuable side deals related to manufacturing or co-promotion.30 This adaptive behavior demonstrates a clear pattern: when one legal or strategic avenue is closed by a court ruling, the industry engineers new, more legally ambiguous pathways to achieve the same strategic objective, requiring constant vigilance from antitrust enforcers.

3.4 The Challenger’s Gambit: The Strategic Importance of the P-IV Filing and At-Risk Launches

For generic and biosimilar companies, the primary offensive weapon is the Paragraph IV certification. Filing a P-IV is a declaration of war—a direct challenge to the innovator’s intellectual property that initiates the litigation process and starts the clock on the potential for 180-day exclusivity.1 The timing and execution of this filing are among the most critical strategic decisions a generic firm makes.

An even more aggressive, high-stakes strategy is the “at-risk launch.” This occurs when a generic company decides to launch its product even though the patent litigation with the brand company is not yet fully resolved (for example, after winning at the district court level but while an appeal is still pending). This is a massive gamble. If the generic company ultimately loses the patent case on appeal, it could be liable for enormous damages, potentially bankrupting the company. However, if the patents are ultimately found to be invalid or not infringed, the company can reap huge profits by being on the market months or even years ahead of its competitors. This strategy is reserved for companies with a high tolerance for risk and a strong belief in the merits of their legal case.

Section 4: The Market Access Maze: PBMs, Payers, and the Politics of Adoption

Overcoming patent barriers and securing FDA approval is only the first half of the battle for generic and, especially, biosimilar manufacturers. The second, and often more decisive, conflict is fought in the opaque and complex world of U.S. drug reimbursement. Here, powerful intermediaries known as Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs) act as gatekeepers, and their financial incentives can create counterintuitive barriers that prevent the adoption of lower-cost medicines, effectively nullifying the benefits of competition.

4.1 The Power of the PBM: Gatekeepers of the U.S. Drug Market

PBMs are third-party companies that manage prescription drug benefits on behalf of health insurers, large employers, and other payers. They sit at the center of the pharmaceutical distribution chain, wielding immense influence over which drugs patients can access and how much the healthcare system pays for them.40

Their core functions include:

- Negotiating Rebates: PBMs leverage the purchasing power of their millions of enrollees to negotiate substantial discounts, known as rebates, from drug manufacturers.

- Creating Formularies: Based on these negotiations, PBMs create formularies, which are tiered lists of covered prescription drugs. A drug’s placement on a preferred tier (with a lower patient co-pay) is a primary driver of its market share.

- Contracting with Pharmacies: PBMs establish networks of pharmacies and determine how much those pharmacies are reimbursed for dispensing medications.40

The U.S. PBM market is highly concentrated. Just three dominant PBMs—CVS Caremark (owned by CVS Health), Express Scripts (owned by Cigna), and Optum Rx (owned by UnitedHealth Group)—control approximately 80% of the market.41 This concentration gives them enormous leverage in negotiations with both drug manufacturers and pharmacies.

4.2 The “Rebate Wall”: How Financial Incentives Can Block Lower-Cost Biosimilars

While PBMs were initially created to control drug costs, their business model has evolved in a way that can create perverse incentives, particularly when it comes to biosimilars. The central issue is the “rebate wall,” also known as a “rebate trap”.42

This exclusionary contracting practice works as follows: An incumbent manufacturer of a blockbuster biologic with high market share offers the PBM a very large rebate, which is typically calculated as a percentage of the drug’s high list price. This rebate is often contingent on the PBM granting the originator drug preferred, exclusive, or near-exclusive status on its formulary, meaning it must meet certain market share targets.42

When a lower-cost biosimilar enters the market, the PBM faces a difficult choice. The biosimilar may have a lower net price (the price after all discounts), but switching to it could cause the PBM to lose the massive rebate on the originator product. Because the originator has such a large volume of sales, the total dollar value of the rebate on the originator can be greater than the total savings generated by switching a smaller number of patients to the biosimilar. The PBM is thus financially incentivized to maintain the market share of the high-list-price, high-rebate originator drug, effectively building a “wall” that blocks the lower-cost competitor.42

This dynamic is rooted in a fundamental misalignment of incentives. PBM revenue is often derived from a share of the rebates they negotiate or from administrative fees that are tied to the drug’s list price.40 A system that rewards high list prices and large rebates can be more profitable for the PBM than one that promotes the lowest net cost. This creates a classic principal-agent problem, where the PBM’s (the agent’s) financial interests are not perfectly aligned with those of its clients (the principals: health plans and employers) or the patients they serve.

A critical consequence of this system is its impact on patient out-of-pocket costs. Patient cost-sharing, such as co-insurance, is frequently calculated based on the drug’s inflated list price, not the lower, post-rebate net price that the insurer pays.42 As a result, patients can end up paying more for a “preferred” originator drug on their formulary than they would for a non-preferred, lower-list-price biosimilar.

4.3 Formulary Wars: The Strategic Use of Tiering, Step Therapy, and Preferred Status

PBMs use the drug formulary as their primary tool to direct market share toward their financially preferred products. This is accomplished through several strategic mechanisms:

- Tiering: Formularies are typically divided into tiers, with each tier having a different level of patient cost-sharing. By placing the high-rebate originator biologic on a lower co-pay tier and the competing biosimilar on a higher tier, PBMs can create a strong financial disincentive for patients to use the biosimilar.

- Step Therapy: This strategy requires a patient to first try and “fail” on the preferred originator drug before the plan will cover the biosimilar.44 This creates a significant administrative hurdle that preserves the originator’s market share, particularly for patients already stable on the therapy.

- Exclusion: In an increasingly common tactic, PBMs may exclude lower-cost biosimilars from their formularies altogether, offering patients no coverage for the competitor product and leaving the high-rebate originator as the only option.43

The case of Humira biosimilars provides a stark illustration of these forces at work. Despite multiple biosimilars launching in the U.S. in 2023 with list price discounts of up to 85%, they gained less than 3% of the market in their first year. The primary reason was that PBMs largely maintained Humira’s preferred formulary status in exchange for even larger rebates from AbbVie, effectively neutralizing the biosimilars’ price advantage.45

4.4 Beyond Economics: Overcoming Physician and Patient Hesitancy

While PBM-driven financial incentives are the dominant barrier to biosimilar adoption, non-economic factors also play a role. Unlike small-molecule generics, which are considered identical copies, biosimilars are only “highly similar” to their reference products. This distinction can lead to hesitancy among some physicians and patients.11

Concerns, though largely unsupported by extensive clinical data, may exist regarding the safety and efficacy of switching a patient from a stable regimen on an originator biologic to a biosimilar.42 Furthermore, the “nocebo effect”—where a patient’s negative expectations about a treatment can lead to perceived negative outcomes—can also be a factor, particularly if the switch is not communicated effectively.46 Overcoming these perceptions requires targeted education and awareness initiatives led by trusted medical authorities to build confidence in the clinical value and equivalence of biosimilars.

Section 5: The Next Frontier: Navigating the Complexity of Modern Generics and Biosimilars

As pharmaceutical innovation advances, the nature of drugs losing patent protection is changing. The market is moving away from simple, easily replicated small-molecule pills toward increasingly complex products. For these modern medicines, the primary barrier to competition is often not the innovator’s patent portfolio but the sheer scientific, manufacturing, and regulatory difficulty of creating a generic or biosimilar equivalent. This “complexity cliff” can create a de facto period of extended market exclusivity long after the last patent has expired, challenging the traditional model of post-patent competition.

5.1 Defining “Complex Generics”: The Scientific and Manufacturing Hurdles

The FDA defines complex generics as products that have one or more of the following features that can make them more difficult to develop and demonstrate bioequivalence for:

- Complex active ingredients (e.g., peptides, complex mixtures)

- Complex formulations (e.g., liposomes, nanoparticles)

- Complex routes of delivery (e.g., locally acting drugs like nasal sprays or inhalers)

- Complex drug-device combination products (e.g., auto-injectors, metered-dose inhalers) 47

Developing a generic version of these products presents formidable challenges. Standard bioequivalence testing, which relies on measuring the concentration of the drug in the bloodstream over time (pharmacokinetics, or PK), is often insufficient. For a locally acting inhaler, for example, the amount of drug in the blood may not correlate with its effect in the lungs. Proving equivalence may require complex clinical endpoint studies, which are far more expensive, time-consuming, and carry a higher risk of failure than simple PK studies.2 These scientific and financial hurdles act as a major economic deterrent, meaning many complex drugs face limited or no generic competition, even after patent expiry.2 Recognizing this market failure, the FDA, through the Generic Drug User Fee Amendments (GDUFA) program, has prioritized research and the development of Product-Specific Guidances (PSGs) to help streamline the approval pathway for these critical medicines.47

5.2 The Biologics Challenge: Why Biosimilars Are Not Generics

The distinction between generics and biosimilars is fundamental and rooted in science. A generic drug is an identical chemical copy of a small-molecule drug, synthesized through predictable chemical reactions. A biologic, in contrast, is a large, complex molecule (such as a protein or monoclonal antibody) produced in a living system, like yeast or mammalian cells.51 Because living systems have inherent variability, it is scientifically impossible to create an identical copy of a biologic. The resulting product is therefore designated a “biosimilar”—meaning it is “highly similar” to the reference product, with no clinically meaningful differences in terms of safety, purity, and potency.25

This scientific difference has massive downstream consequences for development.

- Cost: Developing a simple generic typically costs between $2 million and $10 million.26 Developing a biosimilar is an order of magnitude more expensive, costing between $100 million and $300 million.26

- Timeline: A generic can often be developed and approved in 2 to 3 years. A biosimilar program takes much longer, typically 7 to 9 years.26

This substantially higher barrier to entry is a primary reason why competition in the biologics space is less robust than in the small-molecule market. The high upfront investment and risk mean that fewer companies can afford to enter the race, naturally limiting the number of competitors and the intensity of price competition.

5.3 The Interchangeability Hurdle: A Key Differentiator in Market Uptake

A key regulatory and commercial distinction that further separates the generic and biosimilar markets is the concept of “interchangeability.” In most U.S. states, when a physician prescribes a brand-name small-molecule drug, a pharmacist can automatically substitute a generic version without consulting the prescriber. This automatic substitution is a primary driver of the rapid market share conversion seen with generics.

For biosimilars, this is not the default. A biosimilar is approved based on a demonstration of biosimilarity. To be deemed “interchangeable,” a biosimilar manufacturer must conduct additional studies, including switching studies in patients, to prove that the biosimilar can be substituted for the reference product back and forth without any increased risk or diminished efficacy.42

Achieving this higher regulatory designation is a significant additional cost and barrier for biosimilar developers. However, it is a powerful commercial advantage. An interchangeable biosimilar can be automatically substituted at the pharmacy level (subject to state laws), which can dramatically accelerate its market uptake.52 The lack of an interchangeability designation for most biosimilars means that each prescription must be explicitly written for that specific biosimilar by the physician, a significant factor contributing to their slower market penetration compared to generics.42 As the industry matures, the pursuit of interchangeability is becoming a key strategic differentiator for biosimilar manufacturers.

| Table 3: Small-Molecule Generics vs. Biosimilars: A Comparative Analysis | |

| Characteristic | |

| Active Ingredient | |

| Development Cost | |

| Development Timeline | |

| Regulatory Pathway | |

| Key Requirement | |

| Automatic Substitution? | |

| Typical Price Discount | |

| Source: Synthesized from multiple sources.25 |

Section 6: Case Studies in Market Transformation

The theoretical frameworks of patent law, economic erosion, and market access strategy come to life in the real-world histories of blockbuster drugs facing their patent cliffs. By examining three landmark cases—Lipitor, Gleevec, and Humira—it is possible to trace the evolution of pharmaceutical competition. These case studies illustrate how the interplay of innovator defense, challenger offense, and market structure creates unique outcomes that provide powerful strategic lessons for the future.

6.1 Case Study 1: Lipitor (Atorvastatin) – The Archetypal Patent Cliff and Pfizer’s Unprecedented Defense

- Context: In the early 2010s, Pfizer’s Lipitor (atorvastatin) was the world’s best-selling drug, a cholesterol-lowering medication that generated peak annual sales of $12.9 billion in 2006.18 Its U.S. patent expiration on November 30, 2011, was the most anticipated patent cliff in history, representing an existential threat to Pfizer’s revenue.19

- Innovator Strategy: Rather than passively accepting its fate, Pfizer launched an aggressive and unprecedented defensive campaign it dubbed the “180-Day War,” designed to retain as much market share as possible during the initial six-month exclusivity period of the first generic filers, Ranbaxy and Pfizer’s own authorized generic partner, Watson.53 The strategy was multifaceted:

- Payer Negotiations: Pfizer negotiated deep rebates with major PBMs and health insurers to make branded Lipitor’s net cost to them less than the competing generic for the first six months.53

- Direct-to-Patient Engagement: The company launched the “Lipitor for You” program, offering patients a co-pay card that reduced their out-of-pocket cost for the brand to just $4 per month, effectively neutralizing the financial incentive to switch.53

- Authorized Generic (AG): By partnering with Watson to launch an AG, Pfizer ensured it would capture a significant portion (an estimated 70%) of the revenue from generic sales during the exclusivity period, directly competing with Ranbaxy.53

- Continued Promotion: In a move that defied industry convention for off-patent drugs, Pfizer continued to invest heavily in direct-to-consumer advertising and physician detailing for Lipitor throughout 2011, spending over $150 million on TV ads alone.53

- Outcome: Pfizer’s strategy was a remarkable short-term success. While the company still suffered a significant financial blow—global Lipitor sales fell 42% in the first quarter post-expiry—it managed to retain an unexpectedly high 30% of the U.S. market share at the end of the 180-day period.53 Ranbaxy, the first generic challenger, still captured over 50% of the generic market and earned an estimated $600 million.53 The Lipitor case became the textbook example of how a well-resourced and strategically agile innovator could actively manage its own patent cliff, blunting the initial impact and maximizing revenue in the final months of exclusivity.

6.2 Case Study 2: Gleevec (Imatinib) – Slower Erosion and Market Dynamics in Specialty Oncology

- Context: Novartis’s Gleevec (imatinib) was a paradigm-shifting therapy for chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), transforming a fatal cancer into a manageable chronic condition. As a life-saving specialty drug, it commanded a high price, which escalated from $26,400 per year at its 2001 launch to over $120,000 per year by the time its patent expired.54 Through patent term extensions and the defense of secondary patents, Novartis successfully delayed generic entry in the U.S. from its original 2013 date until February 2016.54

- Slower Erosion: The market dynamics for Gleevec defied the classic patent cliff model. Price erosion was exceptionally slow. The first generic entrant, Sun Pharma, launched at a modest 30% discount during its 180-day exclusivity period.54 Nearly two years after generic entry, the average price for imatinib had fallen by only 10%, a stark contrast to the 80%+ declines typical for small-molecule drugs.55

- Key Factors for Slow Erosion:

- Specialty Drug Dynamics: In a life-or-death therapeutic area like oncology, both physicians and patients exhibit strong brand loyalty and are often reluctant to switch from a therapy that is working. Data showed that 24% of imatinib prescription claims were for “dispense as written,” indicating a specific preference for the brand.55

- Limited Competition: The initial duopoly between branded Gleevec and Sun Pharma’s generic created limited price pressure.

- Lifecycle Management (“Product Hopping”): Well before Gleevec’s patent expiry, Novartis began heavily marketing its next-generation, patent-protected CML drug, Tasigna (nilotinib), successfully shifting a portion of the market to the newer product and protecting its oncology franchise revenue.54

- Outcome: The Gleevec case demonstrates that the patent cliff is not a universal law. In specialty therapeutic areas with high unmet need, strong brand loyalty, and effective lifecycle management, innovators can significantly slow the pace of market share and price erosion. It took over two years for payers to realize substantial cost savings from generic imatinib, highlighting the unique market dynamics that can insulate high-value specialty drugs from immediate, severe competition.56

6.3 Case Study 3: Humira (Adalimumab) – A Modern Masterclass in Patent Thickets, Rebate Walls, and Market Access Warfare

- Context: AbbVie’s Humira (adalimumab), an injectable biologic for autoimmune conditions, succeeded Lipitor as the world’s best-selling drug, with peak annual sales exceeding $20 billion.36 Its primary patent expired in 2016, and biosimilars entered the European market in 2018. However, U.S. entry was delayed until 2023, a direct result of AbbVie’s multi-pronged defensive strategy.

- Innovator Strategy (A Synthesis of Modern Tactics): AbbVie’s defense of Humira represents the culmination of every advanced strategy developed over the past two decades.

- The Ultimate Patent Thicket: AbbVie created an unparalleled legal fortress of over 130 granted U.S. patents on Humira, covering every conceivable aspect of the drug, its formulation, and its use. This forced every potential biosimilar competitor into costly litigation and ultimately into settlement agreements that dictated a staggered U.S. launch schedule beginning in January 2023.31

- The Impermeable Rebate Wall: This was the decisive battleground. Upon the launch of the first biosimilars in 2023, AbbVie leveraged Humira’s dominant market share to offer massive rebates to PBMs. This made it more profitable for the PBMs to maintain Humira’s preferred status on their formularies than to switch to the biosimilars, even though the biosimilars launched at list price discounts of up to 85%.45

- Strategic Product Hopping: In parallel, AbbVie executed a successful product hop, investing heavily in marketing its newer, patent-protected immunology drugs, Skyrizi and Rinvoq. This strategy successfully transitioned a significant number of patients away from Humira, cannibalizing its own sales to protect its long-term franchise dominance from the impending biosimilar wave.36

- Outcome: The result in the first year of U.S. competition was a near-total failure of biosimilar adoption. Despite the availability of ten different biosimilars by the end of 2023, they collectively captured less than 3% of the total adalimumab market share.45 AbbVie’s net revenue for Humira fell by 35%, not because it lost market share, but because it had to pay billions more in rebates to PBMs to maintain its formulary position.45 The Humira case is a stark and powerful lesson for the modern era: for complex biologics, overcoming the patent thicket is merely the price of admission. The decisive battle is won or lost in the market access maze controlled by PBMs, where rebate walls can prove to be a more formidable barrier than any patent.

| Table 4: Comparative Analysis of Landmark Patent Cliff Case Studies |

| Drug (Brand/Generic) |

| Therapeutic Area |

| Peak Annual Sales |

| Primary Innovator Defense |

| Key Barrier to Competition |

| Price Erosion at ~1 Year |

| Key Takeaway |

Conclusion

The journey of a generic or biosimilar drug from development to market is a complex and multifaceted process, governed by an intricate web of legal statutes, regulatory hurdles, economic forces, and strategic corporate warfare. The landscape of pharmaceutical competition has evolved significantly from the era of the straightforward “patent cliff.” While the foundational principles of the Hatch-Waxman Act’s “grand bargain” remain intact, the strategies employed by both innovator and challenger companies have grown infinitely more sophisticated.

The analysis reveals several critical conclusions for stakeholders navigating this environment:

- Competition is a Deliberately Engineered Conflict: The U.S. system is not designed for peaceful coexistence but for structured, predictable conflict. The P-IV patent challenge and the 180-day exclusivity incentive were created to deputize generic firms as agents of competition, using their profit motive to police the boundaries of patent monopolies. Understanding that litigation and strategic maneuvering are intended features, not bugs, is essential to forecasting market events.

- The Economic Models for Generics and Biosimilars are Fundamentally Divergent: The sharp, predictable price erosion and rapid market share conversion characteristic of small-molecule generics do not apply to biosimilars. Higher development costs, greater scientific complexity, the lack of automatic substitution, and formidable market access barriers create a “patent slope” rather than a cliff for biologics. This results in a slower, more uncertain path to savings and requires fundamentally different commercialization strategies.

- Innovator Defenses Have Evolved from Legal to Commercial Battlegrounds: While legal strategies like building “patent thickets” remain a primary line of defense, the most effective modern tactics are commercial and market-access-oriented. The Humira case study definitively proves that even after a patent fortress is breached, an innovator can use its market power to construct “rebate walls” with PBMs that effectively neutralize the price advantage of competitors. This shifts the decisive battle from the courtroom to the formulary committee.

- A “Complexity Cliff” is Emerging as a New Barrier: For an increasing number of modern drugs, particularly complex generics and biologics, the primary barrier to competition is no longer legal but scientific and financial. The immense cost and technical difficulty of replicating these products create a de facto monopoly that can persist long after patent expiration, representing a systemic challenge to the traditional model of generic competition.

Looking ahead, as the pharmaceutical industry faces a historic wave of patent expirations for some of the most complex and expensive drugs ever developed, these dynamics will only intensify. Policymakers, payers, and manufacturers must grapple with a system where the intended balance between innovation and access is increasingly strained by misaligned incentives and sophisticated new barriers to competition. For any organization operating within this ecosystem, a deep, nuanced understanding of these interlocking forces is not merely an academic exercise—it is a prerequisite for strategic survival and success.

Works cited

- The Grand Bargain: How the Hatch-Waxman Act Forged the Modern …, accessed October 3, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/development-of-the-generic-drug-industry-in-the-us-after-the-hatch-waxman-act-of-1984/

- The Generic Gold Rush: A Strategic Playbook for Turning Patent Cliffs into Market Dominance – DrugPatentWatch, accessed October 3, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-generic-gold-rush-a-strategic-playbook-for-turning-patent-cliffs-into-market-dominance/

- Biosimilar patent cliff looms—expirations will change market – Cytiva, accessed October 3, 2025, https://www.cytivalifesciences.com/en/us/insights/biosimilar-patent-expire

- Next Patent Cliff May Further Spur M&A Activity – The National Law Review, accessed October 3, 2025, https://natlawreview.com/article/will-next-patent-cliff-further-spur-ma-activity-and-what-does-mean-companies-right

- The Patent Cliff’s Shadow: Impact on Branded Competitor Drug Sales – DrugPatentWatch, accessed October 3, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-effect-of-patent-expiration-on-sales-of-branded-competitor-drugs-in-a-therapeutic-class/

- Patent Problems Create Higher Drug Prices. Time to Fix the System – R Street Institute, accessed October 3, 2025, https://www.rstreet.org/commentary/patent-problems-create-higher-drug-prices-time-to-fix-the-system/

- How Drug Life-Cycle Management Patent Strategies May Impact …, accessed October 3, 2025, https://www.ajmc.com/view/a636-article

- Patents and Exclusivity | FDA, accessed October 3, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/media/92548/download

- Frequently Asked Questions on Patents and Exclusivity – FDA, accessed October 3, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/development-approval-process-drugs/frequently-asked-questions-patents-and-exclusivity

- The Patent Playbook Your Lawyers Won’t Write: Patent strategy …, accessed October 3, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-patent-playbook-your-lawyers-wont-write-patent-strategy-development-framework-for-pharmaceutical-companies/

- Generic Drug Entry Timeline: Predicting Market Dynamics After Patent Loss, accessed October 3, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/generic-drug-entry-timeline-predicting-market-dynamics-after-patent-loss/

- Understanding the Lifecycle of Generic Drugs: From Patent Cliffs to Pharmacy Shelves, accessed October 3, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/understanding-the-lifecycle-of-generic-drugs-from-development-to-market-impact/

- The Hatch-Waxman Act: encouraging innovation and generic drug competition – PubMed, accessed October 3, 2025, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20615183/

- What to Expect from Drug Patent Litigation – DrugPatentWatch, accessed October 3, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/what-to-expect-from-drug-patent-litigation/

- The Hatch-Waxman Act: A Primer – EveryCRSReport.com, accessed October 3, 2025, https://www.everycrsreport.com/reports/R44643.html

- Estimating the Effect of Entry on Generic Drug Prices Using Hatch-Waxman Exclusivity – Federal Trade Commission, accessed October 3, 2025, https://www.ftc.gov/sites/default/files/documents/reports/estimating-effect-entry-generic-drug-prices-using-hatch-waxman-exclusivity/wp317.pdf

- Full article: Continuing trends in U.S. brand-name and generic drug competition, accessed October 3, 2025, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13696998.2021.1952795

- Managing the challenges of pharmaceutical patent expiry: a case study of Lipitor, accessed October 3, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/309540780_Managing_the_challenges_of_pharmaceutical_patent_expiry_a_case_study_of_Lipitor

- Drug Patent Expirations and the “Patent Cliff” – U.S. Pharmacist, accessed October 3, 2025, https://www.uspharmacist.com/article/drug-patent-expirations-and-the-patent-cliff

- Drug Competition Series – Analysis of New Generic Markets Effect of Market Entry on Generic Drug Prices – https: // aspe . hhs . gov., accessed October 3, 2025, https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/510e964dc7b7f00763a7f8a1dbc5ae7b/aspe-ib-generic-drugs-competition.pdf

- How to Use Drug Price Data for Generic Entry Portfolio Management and Prioritization, accessed October 3, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/how-to-use-drug-price-data-for-generic-entry-pricing/

- New Evidence Linking Greater Generic Competition and Lower Generic Drug Prices – FDA, accessed October 3, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/media/133509/download

- Top 10 Challenges in Generic Drug Development – DrugPatentWatch, accessed October 3, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/top-10-challenges-in-generic-drug-development/

- Price Declines after Branded Medicines Lose Exclusivity in the US – IQVIA, accessed October 3, 2025, https://www.iqvia.com/-/media/iqvia/pdfs/institute-reports/price-declines-after-branded-medicines-lose-exclusivity-in-the-us.pdf

- The Paradox of Progress: Does Biosimilar Competition Truly Reduce Patient Out-of-Pocket Costs for Biologic Drugs? – DrugPatentWatch, accessed October 3, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/biosimilar-competition-does-not-reduce-patient-out-of-pocket-costs-for-biologic-drugs/

- Competition in the US Therapeutic Biologics Market – https: // aspe . hhs . gov., accessed October 3, 2025, https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/3a05af053eeeaa4c7c95457dcafefa68/ASPE-Competition-in-the-Biologics-Market.pdf

- Biosimilars Drive Cost Savings and Achieve 53% Market Share Across Treatment Areas, accessed October 3, 2025, https://www.centerforbiosimilars.com/view/biosimilars-drive-cost-savings-and-achieve-53-market-share-across-treatment-areas

- In the Thick(et) of It: Addressing Biologic Patent Thickets Using the Sham Exception to Noerr-Pennington, accessed October 3, 2025, https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/iplj/vol33/iss3/5/

- Unveiling the Secrets Behind Big Pharma’s Patent Thickets – DrugPatentWatch, accessed October 3, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/unveiling-the-secrets-behind-big-pharmas-patent-thickets/

- Strategies That Delay Market Entry of Generic Drugs – Commonwealth Fund, accessed October 3, 2025, https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/journal-article/2017/sep/strategies-delay-market-entry-generic-drugs

- In the case of brand name drugs versus generics, patents can be bad medicine, WVU law professor says, accessed October 3, 2025, https://wvutoday.wvu.edu/stories/2022/12/19/in-the-case-of-brand-name-drugs-vs-generics-patents-can-be-bad-medicine-wvu-law-professor-says

- Humira – I-MAK, accessed October 3, 2025, https://www.i-mak.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/i-mak.humira.report.3.final-REVISED-2021-09-22.pdf

- White Paper Part 2: Failure to Launch: Barriers to Biosimilar Market …, accessed October 3, 2025, https://accessiblemeds.org/resources/reports/white-paper-part-2-failure-launch-barriers-biosimilar-market-adoption

- Antitrust and Authorized Generics – Stanford Law Review, accessed October 3, 2025, https://review.law.stanford.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2020/03/Peelish-72-Stan.-L.-Rev.-791.pdf

- Pay-for-Delay: How Drug Company Pay-Offs Cost Consumers Billions, accessed October 3, 2025, https://www.ftc.gov/sites/default/files/documents/reports/pay-delay-how-drug-company-pay-offs-cost-consumers-billions-federal-trade-commission-staff-study/100112payfordelayrpt.pdf

- Biosimilars and the Challenge of “Product Hopping” – RazorMetrics™, accessed October 3, 2025, https://razormetrics.com/2024/11/14/biosimilars-and-the-challenge-of-product-hopping/

- Pay for Delay | Federal Trade Commission, accessed October 3, 2025, https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/topics/competition-enforcement/pay-delay

- FTC: ‘Pay for Delay’ Hinders Competition in the Pharmaceuticals Market, accessed October 3, 2025, https://www.purduegloballawschool.edu/blog/news/ftc-pay-for-delay-pharmaceuticals-market

- Reverse Payments: From Cash to Quantity Restrictions and Other Possibilities, accessed October 3, 2025, https://www.ftc.gov/enforcement/competition-matters/2025/01/reverse-payments-cash-quantity-restrictions-other-possibilities

- What Pharmacy Benefit Managers Do, and How They Contribute to Drug Spending, accessed October 3, 2025, https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/explainer/2025/mar/what-pharmacy-benefit-managers-do-how-they-contribute-drug-spending

- Breaking Down Biosimilar Barriers: Payer and PBM Policies, accessed October 3, 2025, https://www.centerforbiosimilars.com/view/breaking-down-biosimilar-barriers-payer-and-pbm-policies

- Realizing the Benefits of Biosimilars: Overcoming Rebate Walls …, accessed October 3, 2025, https://healthpolicy.duke.edu/sites/default/files/2022-03/Biosimilars%20-%20Overcoming%20Rebate%20Walls.pdf

- PBMs, not patents, are blocking access to lower-cost medicines | PhRMA, accessed October 3, 2025, https://phrma.org/blog/pbms-not-patents-are-blocking-access-to-lower-cost-medicines

- The Biosimilar Reimbursement Revolution: Navigating Disruption and Seizing Competitive Advantage – DrugPatentWatch, accessed October 3, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-impact-of-biosimilars-on-biologic-drug-reimbursement-models/

- Sustaining competition for biosimilars on the pharmacy benefit: Use …, accessed October 3, 2025, https://www.jmcp.org/doi/10.18553/jmcp.2024.30.6.600

- White Paper Offers Tips for Sustaining Biosimilar Progress, Avoiding a Market Void, accessed October 3, 2025, https://www.centerforbiosimilars.com/view/white-paper-offers-tips-for-sustaining-biosimilar-progress-avoiding-a-market-void

- Complex Generics News – FDA, accessed October 3, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/generic-drugs/complex-generics-news

- Research and Education Needs for Complex Generics – PMC, accessed October 3, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8732887/

- 2025 GDUFA Public Workshop | Challenges and Opportunities for Complex Generic Products – FDA, accessed October 3, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/media/188024/download

- FDA Drug Competition Action Plan, accessed October 3, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/guidance-compliance-regulatory-information/fda-drug-competition-action-plan

- Full article: Evolving global regulatory landscape for approval of biosimilars: current challenges and opportunities for convergence, accessed October 3, 2025, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/14712598.2025.2507832?src=

- U.S. Biosimilar Market Entry Challenges and Facilitating Factors …, accessed October 3, 2025, https://aspe.hhs.gov/reports/biosimilar-market

- Pfizer’s 180-Day War for Lipitor | PM360, accessed October 3, 2025, https://www.pm360online.com/pfizers-180-day-war-for-lipitor/

- Oncology drug pricing – the case of generic imatinib, accessed October 3, 2025, https://gabionline.net/generics/research/Oncology-drug-pricing-the-case-of-generic-imatinib

- Study finds generic options offer limited savings for expensive drugs – VUMC News, accessed October 3, 2025, https://news.vumc.org/2018/05/09/study-finds-generic-options-offer-limited-savings-for-expensive-drugs/

- Realized and Projected Cost-Savings from the Introduction of Generic Imatinib Through Formulary Management in Patients with Chronic Myelogenous Leukemia – PMC, accessed October 3, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6996618/

- Is the Availability of Biosimilar Adalimumab Associated with Budget Savings? A Difference-in-Difference Analysis of 14 Countries – PMC, accessed October 3, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10789825/