Section 1: The U.S. Para IV Challenge as the Strategic Epicenter

The strategic planning for generic drug entry into the United States market is fundamentally shaped by a unique and highly structured legal framework. This framework, while domestic in its application, creates a high-stakes environment where international legal, regulatory, and commercial factors become critical levers for success. Understanding the mechanics of the U.S. system is the essential first step to appreciating the profound impact of these global considerations.

1.1 The Hatch-Waxman Compromise

The Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984, commonly known as the Hatch-Waxman Act, represents a foundational compromise in U.S. pharmaceutical policy. It was designed to balance two competing societal interests: preserving the powerful financial incentives necessary for innovator companies to undertake the costly and high-risk process of developing new medicines, while simultaneously creating a streamlined pathway for lower-cost generic drugs to enter the market upon patent expiration.1 This legislation fundamentally altered the landscape for both brand and generic manufacturers, establishing the confrontational dynamics that define the modern pharmaceutical market.

1.2 The ANDA Pathway and Patent Certifications

Central to the Hatch-Waxman Act is the creation of the Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) pathway. This process allows a generic manufacturer to seek marketing approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) without having to conduct its own costly and time-consuming preclinical and clinical trials to prove safety and efficacy.2 Instead, the generic applicant can rely on the FDA’s previous finding that the innovator’s reference listed drug (RLD) is safe and effective, and need only demonstrate that its own product is bioequivalent—that is, it delivers the same amount of active ingredient into a patient’s bloodstream in the same amount of time.2

As part of the ANDA submission, the generic applicant must address each patent listed for the RLD in the FDA’s publication, Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations, colloquially known as the “Orange Book.” For each listed patent, the applicant must make one of four certifications 5:

- Paragraph I: That no patent information has been filed with the FDA.

- Paragraph II: That the patent has already expired.

- Paragraph III: A statement of the date on which the patent will expire, indicating the generic will not launch until that date.

- Paragraph IV: That the patent is invalid, unenforceable, or will not be infringed by the manufacture, use, or sale of the proposed generic drug product.1

1.3 The Paragraph IV Declaration: An Act of “Artificial Infringement”

A Paragraph IV certification is the most aggressive and strategically significant of the four options. It is a direct legal challenge to the innovator’s intellectual property rights.1 The FDA defines this certification as a statement that, in the generic applicant’s opinion, a listed patent is “invalid, unenforceable, or will not be infringed by the generic product”.1

This declaration is not merely a statement of opinion; under U.S. patent law, specifically 35 U.S.C. § 271(e)(2), the very act of filing an ANDA with a Paragraph IV certification is considered an “artificial act of patent infringement”.1 This legal construct is the linchpin of the Hatch-Waxman dispute resolution system. It creates the necessary legal standing for the brand-name company to sue the generic applicant for patent infringement

before the generic product has been launched and before any actual commercial harm has occurred. This enables patent disputes to be litigated and potentially resolved prior to generic market entry, providing a degree of predictability for all parties.2

1.4 The Litigation Gauntlet: Notice, Lawsuit, and the 30-Month Stay

The filing of a Paragraph IV certification initiates a highly choreographed legal process with strict, statutorily defined timelines.1

- Notification: Within 20 days of receiving confirmation from the FDA that its ANDA is substantially complete and accepted for review, the generic applicant must send a formal “notice letter” to the brand company and the patent holder. This letter must provide a detailed statement of the factual and legal basis for the generic’s assertion that the patent is invalid, unenforceable, or not infringed.1

- The 45-Day Window: Upon receiving the notice letter, the brand company has a critical 45-day window to initiate a patent infringement lawsuit against the generic applicant.1

- The 30-Month Stay: If the brand company files suit within this 45-day period, it triggers an automatic 30-month stay on the FDA’s ability to grant final approval to the generic’s ANDA.8 This stay provides the innovator with a significant period of guaranteed market exclusivity, free from generic competition, while the initial phases of the patent litigation unfold.

The strategic value of this 30-month stay is substantial, often protecting hundreds of millions of dollars in revenue for the brand company.1 However, its role as the ultimate gatekeeper of generic entry is often overstated. Research indicates that for many drugs, the 30-month stay period expires years before the generic actually launches. This suggests that other factors—such as the existence of numerous other patents creating a “patent thicket,” the complexities of manufacturing, or the negotiation of settlement agreements—are frequently more determinative of the final generic entry date.1

1.5 The Ultimate Prize: 180-Day First-Filer Exclusivity

To incentivize generic companies to undertake the significant risk and expense of challenging patents, the Hatch-Waxman Act provides a powerful reward: a 180-day period of marketing exclusivity for the first generic applicant to file a “substantially complete” ANDA containing a Paragraph IV certification.1

This exclusivity period is the primary economic driver behind the entire Paragraph IV ecosystem. During these six months, the FDA is barred from approving any subsequent ANDAs for the same drug. This effectively creates a market duopoly between the brand-name drug and the first generic challenger.1 The financial implications are immense. Instead of facing immediate and drastic price erosion of 80-90%, which typically occurs when multiple generics enter the market simultaneously, the first generic can price its product at a more modest discount—often only 15-25% below the brand price.1 For a blockbuster drug, this protected period of limited competition can translate into hundreds of millions of dollars in high-margin revenue, a reward that justifies the multi-million dollar cost of litigation.1

The race to be the “first filer” is therefore fiercely competitive. If multiple generic companies submit substantially complete ANDAs with Paragraph IV certifications on the same day, they share the 180-day exclusivity.14 Furthermore, a first filer can lose this valuable right through a number of “forfeiture” events, such as failing to market the drug within a certain timeframe after approval, withdrawing the application, or entering into certain types of anticompetitive agreements.16

The unique structure of the U.S. system—a codified, pre-market confrontation with defined timelines and an immense financial prize—is precisely what makes international factors so strategically important. Events occurring in foreign courtrooms, regulatory agencies, and manufacturing hubs are not merely parallel activities; they are potential tools that can be leveraged to gain a decisive advantage on the highly lucrative U.S. battlefield.

Section 2: The Global Patent Litigation Battlefield: Precedent, Pressure, and Persuasion

While a Paragraph IV challenge is adjudicated in a U.S. court, the underlying patent portfolio it targets is often global. Innovator companies typically seek parallel patent protection for their blockbuster drugs in all major international markets.18 This creates a global chessboard where legal battles fought in Europe, Canada, and elsewhere can profoundly influence the strategy, timing, and outcome of the central U.S. litigation. A sophisticated Paragraph IV strategy, therefore, requires a global perspective, leveraging international proceedings to create precedent, pressure, and persuasion.

2.1 The European Front: New Opportunities and Old Advantages

The European patent landscape is a complex but strategically vital theater of operations for any company planning a U.S. Paragraph IV challenge. Recent developments and long-standing jurisdictional peculiarities offer both opportunities and risks.

2.1.1 The Unified Patent Court (UPC): A Double-Edged Sword

The establishment of the Unified Patent Court in 2023 represents the most significant change to European patent litigation in a generation. The UPC provides a single, integrated jurisdiction for patent enforcement across numerous EU member states.20 This fundamentally alters the strategic calculus. For a generic challenger, the UPC offers a powerful new tool: a single, successful revocation action can invalidate a brand’s European patent across the entire bloc, creating immense pressure on the innovator’s global revenue streams and strengthening the generic’s hand in U.S. settlement negotiations.21

Conversely, the UPC presents a formidable risk. A single infringement action brought by the brand company could result in a pan-European injunction, crippling the generic’s ability to launch in key European markets and eliminating a crucial source of revenue that might otherwise fund the U.S. litigation.22 The stakes of European litigation have thus been elevated from a series of country-by-country skirmishes to a potential continent-wide, winner-take-all conflict with direct spillover effects on U.S. strategy.

2.1.2 Germany’s Bifurcated System: The “Injunction Gap”

Germany has long been a favored venue for patent litigation due to its unique “bifurcated” system, where patent infringement and patent validity are adjudicated in separate courts with different timelines.23 Infringement proceedings before the regional courts in Düsseldorf, Munich, or Mannheim are notoriously swift, often concluding in 9 to 15 months. In contrast, nullity (validity) actions before the Federal Patent Court are slower, typically taking 18 to 24 months or more.23

This temporal mismatch creates a strategic “injunction gap” that brand companies often exploit. They can secure an infringement injunction from a regional court before the Federal Patent Court has had a chance to rule on the patent’s validity.24 For a generic company, this means it could be enjoined from the German market based on a patent that is later found to be invalid. Anticipating and defending against this “injunction gap” is a key element of European strategy.

2.1.3 The UK as a Bellwether Jurisdiction

The Patents Court of England and Wales is widely respected for its deep technical expertise and the thorough, well-reasoned nature of its judgments.26 While a UK court decision is not binding on a U.S. court, it carries significant persuasive weight. A favorable decision from the UK on a complex issue like obviousness or claim construction can serve as a powerful signal to a U.S. judge, shaping the global narrative around a patent’s strength or weakness. Recent cases, such as the litigation surrounding rivaroxaban and RSV vaccines, demonstrate the UK courts’ rigorous approach to assessing obviousness and claim construction, providing valuable insights for parallel U.S. challenges.28

2.2 Divergent Standards in Other Key Jurisdictions

Beyond Europe, other countries offer unique legal environments that can be strategically advantageous for generic challengers.

2.2.1 Canada’s Heightened Disclosure and Utility Standard

Canadian patent law has historically imposed more stringent requirements for utility and disclosure than U.S. law. Doctrines such as the “promise of the patent” and a strict interpretation of disclosure requirements have created an environment where patents that are valid and enforceable in the U.S. can be vulnerable to challenge in Canada.30 This makes Canada an ideal jurisdiction for “testing the waters”—probing for weaknesses in a brand’s patent portfolio at a lower cost before committing to the more expensive U.S. litigation.

2.2.2 Case Study: Teva v. Pfizer (Viagra) in Canada

The strategic value of exploiting divergent legal standards is perfectly illustrated by the parallel litigation over Pfizer’s patent for Viagra (sildenafil). In the U.S., Teva challenged the patent, but a federal court ultimately upheld its validity.32

In Canada, however, the outcome was dramatically different. Teva argued that Pfizer’s patent failed to meet the disclosure requirements of the Canadian Patent Act. The patent claimed a massive class of compounds for treating erectile dysfunction, but only one compound, sildenafil, had actually been tested and proven effective. The patent disclosed the general class of compounds but deliberately obscured the fact that sildenafil was the true invention, burying it within a series of “cascading claims”.33

The Supreme Court of Canada agreed with Teva, delivering a unanimous judgment that invalidated the patent.35 The Court held that Pfizer had failed its side of the “patent bargain”—the

quid pro quo where an inventor receives a temporary monopoly in exchange for a full and enabling disclosure to the public.33 By intentionally withholding the identity of the specific compound that worked, Pfizer had “gamed the system” and rendered its disclosure insufficient, thus voiding its monopoly rights.33 This landmark case demonstrates how identical facts and a parallel patent can lead to opposite outcomes, highlighting the critical importance of understanding and leveraging international differences in substantive patent law.

2.3 Strategic Application of Foreign Proceedings in U.S. Litigation

The outcomes of these international legal battles are not merely academic. They can be actively and effectively deployed as tools within the U.S. Paragraph IV litigation.

- Persuasive Authority: Favorable foreign judgments, especially well-reasoned decisions from respected courts like those in the UK or the Supreme Court of Canada, can be submitted to U.S. district courts. While not binding, they can influence a judge’s analysis, particularly on nuanced issues of patent law that are shared across jurisdictions.

- Estoppel and Inconsistent Positions: A brand company’s arguments and representations made in foreign courts can be used against it in the U.S. For example, if a brand argues for a narrow interpretation of a patent claim in a German court to avoid invalidity, that argument can be used by the generic in a U.S. court to argue for a finding of non-infringement. Statements made during foreign patent prosecution can also be introduced as relevant evidence for claim construction in the U.S..18

- Discovery and Intelligence: Foreign litigation can serve as an invaluable source of discovery and competitive intelligence. It can reveal the brand’s core legal strategies, expert witness reports, and internal documents that might be more difficult to obtain under U.S. discovery rules, providing a preview of the arguments to be faced in the American case.

- Settlement Leverage: Perhaps most importantly, a string of legal victories abroad—or even a single, decisive loss in a key market like the UPC—can dramatically increase the pressure on a brand company to settle the U.S. litigation. A successful challenge to a key European patent threatens a major revenue stream and signals the vulnerability of the entire global patent portfolio, making a costly, high-risk U.S. trial less appealing for the innovator. The brand’s global patent portfolio, often presented as a “thicket” of impenetrable strength, can thus be turned into a source of global weakness when challenged strategically.36

2.4 Comparative Overview of Key Litigation Jurisdictions

To effectively deploy a global litigation strategy, legal counsel must have a clear understanding of the key procedural and substantive differences between the primary forums. The following table provides a high-level strategic comparison.

| Feature | United States | Germany/UPC | United Kingdom | Canada | |

| Key Forum(s) | Federal District Courts; Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) | Regional Courts (Düsseldorf, Munich, etc.); Unified Patent Court (UPC) | High Court (Patents Court) | Federal Court | |

| Bifurcation (Infringement/Validity) | No (typically tried together in District Court, or validity challenged at PTAB) | Yes (Infringement and Validity in separate courts with different timelines) | No (tried together) | No (tried together) | |

| Provisional Injunction | Available, but difficult to obtain (requires showing irreparable harm) | Readily available; “injunction gap” is a key strategic feature | Available (American Cyanamid factors apply) | Available, but a high bar to meet | |

| Typical Time to Trial (1st Instance) | 24-36 months | 9-15 months (Infringement); 18-24+ months (Validity) | 12-18 months | 24-36 months | |

| Discovery Rules | Extensive and costly (depositions, document production) | Very limited to non-existent | Managed and less extensive than U.S. | More limited than U.S. | |

| Use of Technical Judges | No (legally trained judges); PTAB has technically qualified judges | No (legally trained judges in infringement courts); Yes (in Federal Patent Court for validity) | Yes (specialist patent judges, often with technical backgrounds) | No (legally trained judges) | |

| Persuasive Authority in U.S. | N/A | Moderate | High | Moderate to High | |

| Data derived from: 20 |

This comparative view allows for strategic “forum shopping”.20 A legal team can quickly identify that Germany offers the fastest path to a potential injunction, making it an ideal venue to apply early commercial pressure. Simultaneously, they might determine that Canada’s unique disclosure doctrines make it the best place to test a novel invalidity theory that is less established in U.S. law. This transforms abstract legal differences into a set of actionable, sequenced litigation tactics designed for maximum impact on the primary U.S. case.

Section 3: Navigating Divergent Regulatory Exclusivities and Patent Linkage

Beyond the courtroom, the strategic planning for a Paragraph IV challenge is deeply influenced by the divergent regulatory frameworks of major international health authorities. The rules governing data exclusivity and the linkage between patent status and drug approval vary significantly between the United States and the European Union. Understanding and exploiting these differences is critical for optimizing the timing and global sequencing of a generic launch, which in turn directly impacts the financial modeling and strategic rationale for undertaking a high-risk Paragraph IV challenge.

3.1 A Tale of Two Systems: FDA vs. EMA Data and Market Exclusivity

Regulatory exclusivities are periods of market protection granted by health authorities upon a new drug’s approval. They are distinct from and operate in parallel with patent protection.

3.1.1 U.S. Exclusivity Framework

The FDA grants several key forms of non-patent exclusivity 2:

- New Chemical Entity (NCE) Exclusivity: A five-year period of data exclusivity for drugs containing an active moiety never before approved by the FDA. During this time, the FDA cannot accept an ANDA for review, unless it contains a Paragraph IV certification, in which case it can be submitted after four years.38

- New Clinical Investigation Exclusivity: A three-year period of market exclusivity for drugs that are not NCEs but for which the approval was based on new clinical investigations (other than bioavailability studies). This often applies to new formulations, new indications, or other significant changes to a previously approved drug.38

- Orphan Drug Exclusivity (ODE): A seven-year period of market exclusivity for drugs designated to treat a rare disease or condition affecting fewer than 200,000 people in the U.S..2

3.1.2 EU Exclusivity Framework: The “8+2+1” Formula

The European Medicines Agency (EMA) employs a different, more harmonized system for innovative medicines 38:

- Data Exclusivity: An eight-year period following the innovator’s marketing authorization. During this time, a generic company cannot reference the innovator’s preclinical and clinical trial data to support its own marketing authorization application.

- Market Exclusivity: An additional two-year period following the expiration of the data exclusivity. During this time, a generic product that has been approved cannot be placed on the market.

- “Plus One” Extension: The two-year market exclusivity period can be extended by an additional year if, during the first eight years of data exclusivity, the innovator obtains approval for one or more new therapeutic indications that bring significant clinical benefit compared with existing therapies.

This “8+2+1” formula provides a predictable and robust 10- to 11-year period of protection from generic competition for new medicines in the EU.38 This longer, fixed period of protection in Europe creates a more stable and predictable timeline for generic entry compared to the U.S., where the interplay between shorter regulatory exclusivities and a complex web of patents subject to Paragraph IV challenges introduces far more variability and uncertainty.

3.2 The Power of the Link: The U.S. Orange Book and its Global Counterparts

A critical distinction between the U.S. and European systems lies in the concept of “patent linkage”—the formal connection between a country’s patent system and its drug regulatory system.

3.2.1 The U.S. Orange Book and “Patent Linkage”

The U.S. system embodies a strong form of patent linkage, with the FDA’s Orange Book at its center.40 Innovator companies are required to list in the Orange Book any patents that they believe could reasonably be asserted against an unauthorized generic version of their drug.2 The FDA’s ability to approve a generic ANDA is then directly tied to the status of these listed patents, as demonstrated by the Paragraph IV certification process and the automatic 30-month stay.43

A crucial feature of this system is the FDA’s “ministerial” role in the listing process. The agency does not substantively review the patents for validity or relevance before listing them in the Orange Book; it largely accepts the innovator’s submissions at face value.43 This dynamic creates a structural incentive for brand companies to engage in “evergreening” and build “patent thickets” by listing numerous secondary patents, some of which may be weak or of questionable relevance, to create additional hurdles for generic competitors.36 The burden of “policing” the Orange Book and clearing away these potentially invalid patents falls squarely on the shoulders of generic challengers through the costly Paragraph IV litigation process.45

3.2.2 Canada’s Patent Register

Canada employs a system that is conceptually similar to that of the U.S. Health Canada maintains a Patent Register where innovators can list patents related to their drugs. A generic company seeking a Notice of Compliance (the Canadian equivalent of FDA approval) must address these listed patents, which can trigger litigation and a statutory stay on approval.31 However, the criteria for which patents are eligible for listing and the specific procedures for litigation differ from the U.S. system.

3.2.3 The EU’s Decoupled Approach

In stark contrast, the European Union largely lacks a formal, centralized system of patent linkage.43 The EMA’s process for granting a marketing authorization for a generic drug is a scientific and regulatory assessment that is handled separately and independently from patent enforcement. Patent disputes are litigated in the national courts of the member states (or now, the UPC), but the outcome of that litigation does not automatically block the EMA from approving a generic product.

3.3 Implications for Global Launch Sequencing and Strategy

These fundamental differences in regulatory frameworks have profound strategic implications for generic manufacturers, enabling a carefully sequenced global launch strategy.

3.3.1 The “European Launch First” Strategy

The combination of the EU’s predictable 10-year exclusivity period and its decoupled regulatory system allows for a “European Launch First” strategy. A generic company can often secure EMA approval and launch its product in key European markets as soon as the innovator’s data and market exclusivity periods expire, even while the complex and protracted U.S. Paragraph IV litigation and its associated 30-month stay are still ongoing.

3.3.2 Funding the U.S. War Chest

This ability to launch first in Europe is not just a commercial opportunity; it is a critical strategic financing mechanism. The revenue generated from sales in major European markets like Germany, the UK, and France can provide the essential cash flow needed to fund the expensive U.S. legal battle, which can easily cost $5-10 million or more per case.1 In effect, the more predictable and less litigious European market can serve as the “bank” to finance the high-risk, high-reward U.S. litigation campaign.

3.3.3 Market Signaling and Commercial Readiness

A successful launch in Europe also serves as a powerful market signal. It demonstrates to the brand company, investors, and U.S. market stakeholders (such as pharmacy benefit managers and large purchasers) that the generic manufacturer has a validated manufacturing process, a secure supply chain, and the commercial capability to compete effectively. This enhances the generic’s credibility as a threat and can increase pressure on the brand company to settle the U.S. litigation.

3.4 Comparative Overview of Regulatory Frameworks

The strategic importance of these differences is best understood through a direct comparison of the key regulatory features in the U.S. and EU.

| Feature | United States (FDA) | European Union (EMA) | |

| NCE Data Exclusivity | 5 years (ANDA can be filed at 4 years with P-IV) | 8 years (no application can be filed) | |

| Market Exclusivity | 3 years (for new clinical studies) | 2 years (following data exclusivity) | |

| Potential Exclusivity Extension | N/A | +1 year (for new, beneficial indication) | |

| Total NCE Protection | 5 years (variable with patents) | 10-11 years (fixed) | |

| Orphan Drug Exclusivity | 7 years | 10 years | |

| Pediatric Exclusivity Extension | +6 months (added to existing patents/exclusivity) | +2 years (for orphan drugs); +6 months to SPC (for others) | |

| Patent Linkage System | Yes (via Orange Book) | No (decoupled system) | |

| Impact on Generic Filing | Blocked by NCE exclusivity (4-5 years) | Blocked by data exclusivity (8 years) | |

| Impact on Generic Launch | Blocked by patents (via 30-month stay and litigation) | Not blocked by regulatory agency due to patents | |

| Data derived from: 2 |

This comparative framework provides a clear, actionable roadmap for global strategic planning. A business development executive can use this to map out a multi-year launch plan, recognizing that for a new drug, a European launch can be confidently projected for approximately 10 years post-innovator approval. The revenue from that predictable launch can then be factored into the financial models used to justify the investment in the far more uncertain and contentious U.S. Paragraph IV challenge. This transforms two disparate regional market opportunities into a single, integrated global strategy.

Section 4: The Geopolitics of the Pill: Supply Chain and Manufacturing as a Strategic Lever

A legal victory in a Paragraph IV case is rendered meaningless if the generic company cannot reliably manufacture and supply its product to the U.S. market during the critical 180-day exclusivity window. The highly globalized and concentrated nature of the pharmaceutical supply chain introduces a significant layer of operational, regulatory, and geopolitical risk that must be managed as a co-equal pillar of any Paragraph IV strategy. Failure to do so can lead to catastrophic delays, forfeiting the very prize the litigation was meant to secure.

4.1 The API/KSM Choke Point: The India-China Nexus

The modern generic drug supply chain is characterized by an extreme geographic concentration of manufacturing, creating critical vulnerabilities.53

4.1.1 Geographic Concentration of Manufacturing

The United States is heavily dependent on foreign sources for the essential components of its medicines. This is particularly true for generic drugs, which account for approximately 90% of prescriptions filled in the U.S..53 The supply chain begins with Key Starting Materials (KSMs), the basic chemical building blocks, which are synthesized into the Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API), the biologically active component of the drug. The API is then shipped to a different facility to be formulated into the Finished Dosage Form (FDF), such as a tablet or capsule.54

Analysis of the global supply chain reveals a stark concentration:

- India is the single largest supplier of generic APIs to the U.S. market, producing an estimated 35% of the total volume.53

- China is the world’s largest producer of APIs overall and is the dominant global source for many KSMs.54 Critically, India’s massive API industry is itself heavily reliant on China, sourcing an estimated 70-80% of its KSMs and intermediate chemicals from Chinese manufacturers.54

4.1.2 Inherent Vulnerabilities

This India-China nexus creates a series of “choke points” in the supply chain that pose a significant risk to any generic launch plan.54 A disruption in one of these concentrated hubs can have a cascading global effect. Such disruptions can arise from numerous sources:

- Geopolitical Tensions: Trade disputes or political conflicts between the U.S., China, and India could lead to export restrictions or tariffs.

- Public Health Crises: As seen during the COVID-19 pandemic, factory shutdowns in one country can halt the production of critical ingredients needed worldwide.56

- National Industrial Policy: A country might implement an export ban on a critical medicine or API to protect its domestic supply during a shortage.54

- Natural Disasters or Industrial Accidents: A localized event at a major manufacturing cluster can disrupt the global supply of multiple products.53

The opacity of the supply chain, particularly at the KSM level, represents a hidden, systemic risk. A generic company may have a secure contract with a reputable API supplier in India, but that Indian supplier’s own dependence on a single KSM source in China introduces a second-order vulnerability that is difficult to monitor and mitigate.54

4.2 From Factory to Formulary: Regulatory and Logistical Hurdles

Navigating the global supply chain involves more than just managing geopolitical risk; it requires clearing significant regulatory and logistical hurdles.

4.2.1 FDA Oversight of Foreign Facilities

Any foreign facility that manufactures API or FDF for the U.S. market must be registered with the FDA and is subject to the agency’s quality and inspection standards, known as Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP).56 A negative inspection finding can result in an FDA Warning Letter or an Import Alert, which can block all products from that facility from entering the U.S..59 For a generic company relying on that facility for its launch supply, such an action would be devastating, effectively halting the launch regardless of the patent litigation outcome.

4.2.2 The Cost of Compliance and Tariffs

Maintaining facilities to FDA standards is a costly endeavor for foreign manufacturers, with the Indian industry alone spending nearly $1 billion annually on compliance.60 Furthermore, the potential imposition of U.S. tariffs on imported pharmaceuticals or APIs could dramatically alter the financial viability of a generic launch. Generic drugs, especially those with multiple competitors, operate on wafer-thin margins, and a significant tariff could erase any potential profit, forcing manufacturers to abandon the U.S. market.53

4.3 Supply Chain Resilience as a Competitive Advantage

Given these risks, building a resilient and validated supply chain is not an operational afterthought but a core component of competitive strategy.

4.3.1 Risk Mitigation Strategies

Sophisticated generic companies employ a range of methodologies to de-risk their supply chains 54:

- Dual Sourcing: The most critical strategy is to qualify at least two independent suppliers for the same API, preferably in different geographic regions. This provides redundancy and allows for a seamless switch if one supplier is compromised.54

- Upstream Due Diligence: Conducting due diligence not only on the direct API supplier but also on their KSM sources to understand and mitigate second-order risks.

- Rigorous Audits: Performing regular, in-person quality audits of all manufacturing facilities in the supply chain, beyond simply relying on regulatory inspection reports.61

- Inventory Management: Strategically maintaining buffer or safety stocks of API to protect against short-term supply interruptions.54

4.3.2 Integrating Supply Chain into Litigation Planning

The timeline for securing the supply chain must be fully integrated with the legal and regulatory timelines. The 180-day exclusivity clock is unforgiving; it begins upon the first commercial marketing of the drug.7 If a generic company wins its patent case but its API source has not been fully approved by the FDA, it cannot launch.

A change in the API supplier for an approved drug is considered a major manufacturing change by the FDA and typically requires the submission of a “Prior Approval Supplement” (PAS).62 The review and approval of a PAS can take several months. If a generic company’s primary API source fails an FDA inspection just before launch and it must switch to its backup supplier, the resulting PAS filing and review period could consume a significant portion, or even all, of the invaluable 180-day exclusivity period. Therefore, the validation and approval of both primary and secondary API sources must be completed in parallel with the litigation, ensuring that the company is ready to launch the moment a favorable legal outcome is secured.

Section 5: The Financial Calculus: International Pricing, Reimbursement, and Market Viability

The decision to initiate a multi-million dollar Paragraph IV challenge is, at its core, a financial one, based on a rigorous assessment of risks and potential rewards. This financial calculus is overwhelmingly dictated by international pricing disparities and the looming threat of U.S. pricing reforms that seek to align American drug costs with global benchmarks. The entire economic model of the Paragraph IV ecosystem is predicated on the U.S.’s unique position as a global pricing outlier.

5.1 Quantifying the Prize: The U.S. Market in a Global Context

The fundamental economic driver that makes the high cost and risk of U.S. Paragraph IV litigation a rational business strategy is the extraordinary price premium that pharmaceutical products command in the United States compared to other developed nations.63

5.1.1 The U.S. Price Premium

Data from government and academic analyses consistently demonstrate this stark disparity. A 2024 report from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), using 2022 data, found that:

- Across all drugs (brand and generic), U.S. prices were 278% of the prices in 33 other Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries. In other words, for every dollar spent on a drug in a comparison country, $2.78 was spent in the U.S..65

- For brand-name originator drugs, the gap was even more dramatic. U.S. gross prices were 422% of those in comparison countries.65 Even after adjusting for estimated U.S. rebates, brand prices remained over 300% of international prices.65

- Conversely, for unbranded generic drugs, U.S. prices were lower, at just 67% of the prices in comparison countries, reflecting a highly competitive domestic generic market.65

5.1.2 The Economic Rationale for U.S. Focus

This massive premium on brand-name drugs creates the enormous potential revenue pool that generic challengers are targeting. The financial stakes in Paragraph IV litigation are a direct reflection of this pricing environment, with cases averaging $4.3 billion in value for brand firms and over $200 million for generic firms.67 The potential profits to be made by capturing even a fraction of the U.S. market during the 180-day exclusivity period dwarf the returns available in the price-controlled markets of Europe, Canada, or Japan, where governments aggressively negotiate or regulate drug prices.63 This U.S.-centric profit opportunity is the foundational assumption of the entire Paragraph IV business model.

5.2 The Specter of International Reference Pricing (IRP)

The single greatest external threat to the financial viability of the Paragraph IV challenge model is the potential implementation of International Reference Pricing (IRP) in the United States.

5.2.1 Defining IRP

IRP is a policy tool used by many countries to control drug costs. It involves a government setting or negotiating the price of a drug in its own country by benchmarking it against the prices paid for the same drug in a “basket” of foreign countries.69

5.2.2 U.S. IRP Proposals

In recent years, numerous legislative and administrative proposals in the U.S. have sought to introduce some form of IRP, typically for drugs covered by Medicare.71 These proposals would tie U.S. reimbursement rates to the much lower prices found in the basket of OECD countries, effectively importing foreign price controls into the U.S. market.

5.2.3 Potential Impact on Para IV Viability

The implementation of IRP would represent a systemic shock to the generic industry’s financial model. The revenue a generic company earns during its 180-day exclusivity period is a direct function of the brand’s price (e.g., a 15-25% discount from the brand price). If IRP were to forcibly reduce the brand’s U.S. price by 50-70% to align with an international average, the generic’s potential revenue would be slashed by a corresponding amount.

This would crush the return on investment (ROI) calculation for a Paragraph IV challenge. The cost of litigation—legal fees, expert witnesses, internal resources—would remain largely fixed, while the potential reward would shrink dramatically. A challenge that appears highly profitable today, with a $10 million legal investment targeting a potential $200 million revenue opportunity, could become a clear financial loss if that revenue opportunity is reduced to $60 million. This would force generic companies to abandon challenges against all but the absolute largest blockbuster drugs, leaving weaker patents on many mid-sized but clinically important drugs unchallenged and allowing brand monopolies to persist.

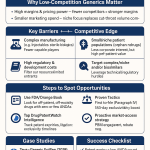

5.3 Building a Global Financial Model for Para IV Target Selection

Given these dynamics, a sophisticated, forward-looking financial model is essential for selecting and prioritizing Paragraph IV targets. This model must go beyond simple U.S. sales data and incorporate a range of international variables.

5.3.1 Key Inputs

A comprehensive financial model should include:

- Revenue Projections: This requires an analysis of the target drug’s current and projected U.S. market size, historical sales data, and detailed modeling of price erosion curves. Data shows that prices typically decline by about 20% with three generic competitors and by 70-80% with ten or more, making the protected 180-day duopoly period exceptionally valuable.13

- Cost Projections: This includes not only the direct legal expenses of litigation but also the costs of API sourcing, formulation development, bioequivalence studies, and regulatory submission fees.73

- Risk Assessment: The model must incorporate probabilities for various outcomes. This includes the probability of winning the litigation (based on an assessment of patent validity and infringement arguments), the potential damages if the company launches “at risk” and loses an appeal, and the probability of supply chain disruptions.74 Historical data suggests a high success rate for first-to-file challengers, but this must be assessed on a case-by-case basis.1

- International Pricing Scenarios: Crucially, the model must include scenario analysis that stress-tests the project’s viability under different potential IRP implementations. This involves modeling the impact of a 30%, 50%, or 70% reduction in the U.S. brand price on the generic’s projected revenue and overall ROI. A drug that is a prime target under the current pricing regime may be a poor investment in a plausible future post-IRP world.

By integrating these global financial and policy variables, a generic company can make a far more robust and strategically sound decision about which patent challenges to pursue, allocating its capital to the opportunities with the best risk-adjusted return.

Section 6: An Integrated Strategic Framework for International Para IV Planning

Success in the modern Paragraph IV landscape requires moving beyond a siloed, U.S.-centric legal approach. It demands the adoption of an integrated strategic framework that treats the challenge as a global, multi-domain campaign. The legal, regulatory, supply chain, and commercial functions must be orchestrated in concert, with intelligence gathered from around the world, all focused on the single objective of successfully launching in the U.S. and maximizing the value of the 180-day exclusivity period.

6.1 Developing a Multi-Jurisdictional Intelligence Program

The foundation of an integrated strategy is a robust intelligence-gathering and analysis capability. Generic companies should establish a dedicated function responsible for systematically monitoring and synthesizing information from key international arenas. The scope of this program should include:

- Global Patent Litigation: Actively tracking patent opposition, revocation, and infringement proceedings involving target drugs and their corresponding patents in key jurisdictions, including the UPC, Germany, the UK, and Canada. This provides early warnings of a patent’s vulnerabilities and insight into the brand’s defense strategies.

- International Regulatory Affairs: Monitoring regulatory filings, marketing authorizations, and data exclusivity expirations with the EMA and other major health authorities. This is essential for planning the “European Launch First” strategy and sequencing global market entry.

- Supply Chain and Geopolitical Risk: Continuously assessing the stability of the API and KSM supply chain, including monitoring geopolitical tensions, trade policy shifts, and the regulatory compliance status of key manufacturing facilities in India, China, and other sourcing hubs.

- U.S. Policy and Pricing Reform: Closely tracking the legislative progress and political viability of IRP proposals and other drug pricing reforms in the U.S. Congress and executive branch. This intelligence is critical for updating the financial models that underpin target selection.

6.2 Coordinating a Global Cross-Functional Team

Intelligence is only valuable if it is shared and acted upon. A successful global strategy requires breaking down the traditional organizational silos between departments. A cross-functional team, comprising senior leaders from Legal, Regulatory Affairs, Supply Chain/Manufacturing, and Commercial/Business Development, should be established for each major Paragraph IV project.

This team’s mandate is to ensure the synchronization of all strategic pillars. The legal team’s litigation timeline must be tightly integrated with the supply chain team’s schedule for sourcing, validating, and securing FDA approval for API suppliers. Simultaneously, the regulatory team’s international filing strategy must be aligned to ensure that potential revenue from ex-U.S. launches is available to support the U.S. legal effort. This coordinated approach ensures that all components of the campaign are moving in lockstep toward the launch date.

6.3 A Decision-Making Matrix for Para IV Target Selection

To translate complex global analysis into a clear, defensible business decision, leadership teams can employ a practical tool such as a weighted scoring matrix. This matrix provides a structured framework for evaluating and prioritizing potential Paragraph IV targets by forcing a holistic assessment of all critical international variables, preventing the common pitfall of focusing too narrowly on U.S. market size alone.

The matrix assigns scores to various factors, weighted according to the company’s strategic priorities and risk tolerance. This allows for a more sophisticated, risk-adjusted comparison of potential drug targets. For example, a blockbuster drug with $2 billion in U.S. sales might initially seem like an ideal target. However, the matrix might reveal that its core patents have been strongly upheld in rigorous German court proceedings, its sole API supplier is located in a geopolitically unstable region, and its therapeutic class is a prime target for IRP. Its overall weighted score might therefore be quite low.

In contrast, a drug with $800 million in sales might receive a much higher score because its European patents have shown vulnerability in opposition proceedings, it has multiple qualified API sources in stable countries, and it belongs to a therapeutic class less likely to be impacted by initial IRP implementation. The matrix thus provides a data-driven rationale for pursuing the more probable success over the higher-risk, larger prize, enabling a more strategic allocation of the company’s finite litigation and development resources.

Table 3: International Risk Assessment Matrix for Para IV Candidates

| Drug Target | U.S. Annual Sales (USD) | U.S. Patent Strength Score (1-5) | EU/UPC Patent Vulnerability (1-5) | Canadian Legal Vulnerability (1-5) | API Sourcing Risk (1-5) | IRP Financial Impact Risk (1-5) | Overall Weighted Score |

| Drug X | 2.5 Billion | 2 (Strong) | 1 (Low) | 2 (Low) | 5 (High – Single source, unstable region) | 5 (High – Prime IRP target) | 2.8 |

| Drug Y | 850 Million | 4 (Weak) | 4 (High) | 5 (High – Disclosure issues) | 2 (Low – Dual source, stable regions) | 2 (Low – Niche therapeutic area) | 3.7 |

| Drug Z | 1.2 Billion | 3 (Moderate) | 3 (Moderate) | 3 (Moderate) | 3 (Moderate – Single source, stable region) | 4 (High) | 3.2 |

| Note: Scoring is illustrative. Scores are from 1 (Low Risk/Vulnerability for Generic) to 5 (High Risk/Vulnerability for Generic), except for U.S. Patent Strength where 1 is Weak and 5 is Strong. The Overall Weighted Score would be calculated based on company-specific weightings for each risk factor. |

Conclusion

The landscape of Paragraph IV patent challenges has evolved far beyond a purely domestic legal dispute. It is now a global chessboard where success demands a sophisticated, multi-faceted strategy that integrates legal intelligence, regulatory planning, supply chain resilience, and financial modeling from across the world. The immense financial reward of the 180-day exclusivity period in the U.S. market will continue to drive these high-stakes confrontations. However, the companies that will prevail in the coming decade will be those that master the international dimensions of this contest—leveraging foreign court victories to pressure U.S. opponents, using European revenues to fund American litigation, de-risking global supply chains to ensure a timely launch, and astutely navigating the profound threat of international reference pricing. In this complex environment, a holistic, globally-informed strategy is no longer just an advantage; it is a prerequisite for survival and success.

Works cited

- What Every Pharma Executive Needs to Know About Paragraph IV Challenges, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/what-every-pharma-executive-needs-to-know-about-paragraph-iv-challenges/

- Hatch-Waxman 101 – Fish & Richardson, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.fr.com/insights/thought-leadership/blogs/hatch-waxman-101-3/

- Patents and Drug Pricing: Why Weakening Patent Protection Is Not in the Public’s Best Interest – American Bar Association, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.americanbar.org/groups/intellectual_property_law/resources/landslide/2025-spring/drug-pricing-weakening-patent-protection-not-best-interest/

- Hatch-Waxman Act — The Basics – Proskauer, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.proskauer.com/events/download-pdf/142

- The Hatch-Waxman Act: A Primer – EveryCRSReport.com, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.everycrsreport.com/reports/R44643.html

- The Regulatory Pathway for Generic Drugs: A Strategic Guide to Market Entry and Competitive Advantage – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-regulatory-pathway-for-generic-drugs-explained/

- Small Business Assistance | 180-Day Generic Drug Exclusivity – FDA, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/cder-small-business-industry-assistance-sbia/small-business-assistance-180-day-generic-drug-exclusivity

- Patent Certifications and Suitability Petitions | FDA, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/abbreviated-new-drug-application-anda/patent-certifications-and-suitability-petitions

- Small Business Assistance: New 180-Day Generic Drug Exclusivity Regulations | FDA, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/cder-small-business-industry-assistance-sbia/small-business-assistance-new-180-day-generic-drug-exclusivity-regulations

- Paragraph IV Explained – ParagraphFour.com, accessed August 6, 2025, https://paragraphfour.com/paragraph-iv-explained/

- An International Guide to Patent Case Management for Judges – WIPO, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.wipo.int/patent-judicial-guide/en/full-guide/united-states/10.13.2

- Generic Drug Entry Prior to Patent Expiration: An FTC Study, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.ftc.gov/sites/default/files/documents/reports/generic-drug-entry-prior-patent-expiration-ftc-study/genericdrugstudy_0.pdf

- How to Use Drug Price Data for Generic Entry Portfolio Management and Prioritization, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/how-to-use-drug-price-data-for-generic-entry-pricing/

- Predicting patent challenges for small-molecule drugs: A cross-sectional study – PMC, accessed August 6, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11867330/

- IPI Regulatory & Marketplace – Strategies Adopted by Branded Drug Manufacturers against Para IV Filers, accessed August 6, 2025, https://international-pharma.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Strategies-adopted-by-branded-drug.pdf

- FDA Clarifies How It Handles 180-Day Exclusivity – BioPharm International, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.biopharminternational.com/view/fda-clarifies-how-it-handles-180-day-exclusivity

- 180-Day Generic Drug Exclusivity – Forfeiture – UC Berkeley Law, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.law.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/180-Day-Generic-Drug-Exclusivity-%E2%80%93-Forfeiture.pdf

- Effect of foreign patent proceedings on U.S. patent litigation – Kirton McConkie, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.kirtonmcconkie.com/publication-299

- PATENT LITIGATION REVIEW 2024 – Leason Ellis LLP, accessed August 6, 2025, https://leasonellis.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/Specialist-chapter-Leason-Ellis-and-Axinn-Peter-Sloane.pdf

- The Judicial Geography of Patent Litigation in Germany: Implications for the Institutionalization of the European Unified Patent Court – MDPI, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.mdpi.com/2076-0760/12/5/311

- Client Alert: The Impact of Coming Changes in European Union Patent Litigation on U.S. Patent Owners’ Enforcement Strategies – Vorys, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.vorys.com/publication-i-Client-Alert-i-The-Impact-of-Coming-Changes-in-European-Union-Patent-Litigation-on-U-S-Patent-Owners-Enforcement-Strategies

- The Impact of the European Unified Patent Court on Filing Strategies – Ropes & Gray LLP, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.ropesgray.com/en/insights/alerts/2016/04/the-impact-of-the-european-unified-patent-court-on-filing-strategies

- Legal 500 Country Comparative Guides 2024, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.legal500.com/guides/chapter/germany-patent-litigation/?export-pdf

- Patent litigation in Germany – an overview – Mewburn Ellis, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.mewburn.com/news-insights/patent-litigation-in-germany-an-overview

- Life Sciences & Pharma IP Litigation 2025 – Germany | Global …, accessed August 6, 2025, https://practiceguides.chambers.com/practice-guides/life-sciences-pharma-ip-litigation-2025/germany/trends-and-developments

- Pregabalin – The Ruling of the UK Supreme Court – Kluwer Patent Blog, accessed August 6, 2025, https://patentblog.kluweriplaw.com/2018/11/14/pregabalin-the-ruling-of-the-uk-supreme-court/

- Understanding IP Law:Four Key Biotech Case Studies March 2025 – PAIL® Solicitors, accessed August 6, 2025, https://pailsolicitors.co.uk/media-solicitors/understanding-ip-law-four-key-biotech-case-studies-march-2025

- Review of Patent Cases in the English Courts in 2024 – Bristows LLP, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.bristows.com/app/uploads/2025/04/Review-of-Patent-Cases-in-the-English-Courts-2024.pdf

- Patent Litigation 2025 – UK – Global Practice Guides – Chambers and Partners, accessed August 6, 2025, https://practiceguides.chambers.com/practice-guides/patent-litigation-2025/uk/trends-and-developments

- Useful in the United States, But Not in Canada: Divergent … – Finnegan, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.finnegan.com/en/insights/articles/useful-in-the-united-states-but-not-in-canada-divergent.html

- Biosimilars patent litigation in Canada and Japan: a comparative strategic overview and EU and US update – GaBIJ, accessed August 6, 2025, https://gabi-journal.net/biosimilars-patent-litigation-in-canada-and-japan-a-comparative-strategic-overview-and-eu-and-us-update.html

- Hidden Agendas? Teva v Pfizer – TheCourt.ca – York University, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.yorku.ca/osgoode/thecourt/2012/02/13/hidden-agendas-teva-v-pfizer/

- Teva Canada Ltd. V. Pfizer Canada Inc., 2012 SCC 60 … – UNCTAD, accessed August 6, 2025, https://unctad.org/ippcaselaw/sites/default/files/ippcaselaw/2020-12/Teva%20Canada%20Ltd.%20v%20Pfizer%20Supreme%20Court%20of%20Cananda%202012.pdf

- Teva v Pfizer: How Viagra Allowed the SCC to Stiffen Patent Disclosure Requirements – TheCourt.ca – York University, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.yorku.ca/osgoode/thecourt/2014/01/07/teva-v-pfizer-how-viagra-allowed-the-scc-to-stiffen-patent-disclosure-requirements/

- Teva Canada Ltd. v. Pfizer Canada Inc. – SCC Cases, accessed August 6, 2025, https://decisions.scc-csc.ca/scc-csc/scc-csc/en/item/12679/index.do

- Patent Defense Isn’t a Legal Problem. It’s a Strategy Problem. Patent Defense Tactics That Every Pharma Company Needs – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/patent-defense-isnt-a-legal-problem-its-a-strategy-problem-patent-defense-tactics-that-every-pharma-company-needs/

- The Dark Reality of Drug Patent Thickets: Innovation or Exploitation …, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-dark-reality-of-drug-patent-thickets-innovation-or-exploitation/

- Optimizing Drug Market Exclusivity in the US and EU Markets – ISPOR, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.ispor.org/docs/default-source/intl2024/ispor2024dahlberghrp27poster137326-pdf.pdf?sfvrsn=2a1e7bbb_0

- Full article: Continuing trends in U.S. brand-name and generic drug competition, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13696998.2021.1952795

- Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations | Orange Book – FDA, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-approvals-and-databases/approved-drug-products-therapeutic-equivalence-evaluations-orange-book

- Patent Listing in FDA’s Orange Book – Congress.gov, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/IF12644

- Orange Book Preface – FDA, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/development-approval-process-drugs/orange-book-preface

- Patent Use Codes for Pharmaceutical Products: A Comprehensive …, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/patent-use-codes-for-pharmaceutical-products-a-comprehensive-analysis/

- The Role of Patents and Regulatory Exclusivities in Drug Pricing | Congress.gov, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/R46679

- When Do Generics Challenge Drug Patents? – Center for Public Health Law Research, accessed August 6, 2025, https://phlr.temple.edu/publications/when-do-generics-challenge-drug-patents

- A Comparative Case for Shifting US Generic Drug Policies to Increase Availability and Lower, accessed August 6, 2025, https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1903&context=njilb

- Brand-name drug costs expected to rise under CETA – PMC, accessed August 6, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5235936/

- Food and Drug Administration vs European Medicines Agency: Review times and clinical evidence on novel drugs at the time of approval – PMC, accessed August 6, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6983504/

- FDA vs. EMA: Navigating Divergent Regulatory Expectations for Cell and Gene Therapies. What Biopharma Companies Need to Know | Cromos Pharma, accessed August 6, 2025, https://cromospharma.com/fda-vs-ema-navigating-divergent-regulatory-expectations-for-cell-and-gene-therapies-what-biopharma-companies-need-to-know/

- EMA/FDA analysis shows high degree of alignment in marketing application decisions between EU and US, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/news/ema-fda-analysis-shows-high-degree-alignment-marketing-application-decisions-between-eu-and-us

- Comparing FDA and EMA Decisions for Market Authorization of Generic Drug Applications covering 2017–2020, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/media/156611/download

- A Comparison of EMA and FDA Decisions for New Drug Marketing Applications 2014–2016: Concordance, Discordance, and Why, accessed August 6, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6977394/

- Over half of the active pharmaceutical ingredients (API) for …, accessed August 6, 2025, https://qualitymatters.usp.org/over-half-active-pharmaceutical-ingredients-api-prescription-medicines-us-come-india-and-european

- Sourcing Key Starting Materials (KSMs) for Pharmaceutical Active …, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/sourcing-the-key-starting-materials-ksms-for-pharmaceutical-active-pharmaceutical-ingredients-apis/

- Pricing & Reimbursement – Ropes & Gray LLP, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.ropesgray.com/-/media/files/articles/2022/08/drug-pricing-reimbursement-for-market-access-2022-chapter-gli-8-29-22/drug-pricing-reimbursement-for-market-access-2022-chapter-gli-8-29-22.pdf?rev=e34f0b0774b340948d8a201603b192bc&hash=BD6BC028D69FED7D31BB544D64A6EFA5

- US drug supply chain exposure to China – Brookings Institution, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/us-drug-supply-chain-exposure-to-china/

- Where drug ingredients are made – POLITICO, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.politico.com/newsletters/prescription-pulse/2025/04/18/where-drug-ingredients-are-made-00296991

- SECTION 3: GROWING U.S. RELIANCE ON CHINA’S BIOTECH AND PHARMACEUTICAL PRODUCTS, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.uscc.gov/sites/default/files/2019-11/Chapter%203%20Section%203%20-%20Growing%20U.S.%20Reliance%20on%20China%E2%80%99s%20Biotech%20and%20Pharmaceutical%20Products.pdf

- Apotex v. USA, Award, 25 Aug 2014 – Jus Mundi, accessed August 6, 2025, https://jusmundi.com/en/document/decision/en-apotex-holdings-inc-and-apotex-inc-v-united-states-of-america-iii-award-monday-25th-august-2014

- Domestic pharma industry may face setback if US imposes tariffs, accessed August 6, 2025, https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/business/india-business/domestic-pharma-industry-may-face-setback-if-us-imposes-tariffs/articleshow/123002989.cms

- APIC QUICK GUIDE FOR API SOURCING, accessed August 6, 2025, https://apic.cefic.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/APIC_Quick_GuideforAPISourcing_200809final.pdf

- Change in API Supplier: Drug Product Quality Tips – FDA, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/media/168954/download

- Funding the Global Benefits to Biopharmaceutical Innovation | Trump White House Archives, accessed August 6, 2025, https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Funding-the-Global-Benefits-to-Biopharmaceutical-Innovation.pdf

- The International Price Index’s Impact on Revenue in the Pharmaceutical Industry – LAW eCommons, accessed August 6, 2025, https://lawecommons.luc.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1491&context=annals

- International Prescription Drug Price Comparisons … – HHS ASPE, accessed August 6, 2025, https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/277371265a705c356c968977e87446ae/international-price-comparisons.pdf

- Decoding Drug Pricing Models: A Strategic Guide to Market Domination – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/decoding-drug-pricing-models-a-strategic-guide-to-market-domination/

- The Distribution of Surplus in the US Pharmaceutical Industry: Evidence from Paragraph iv Patent-Litigation Decisions, accessed August 6, 2025, https://jonwms.web.unc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/10989/2021/06/ParIVSettlements_JLE.pdf

- The Economics of Generic Drug Pricing Strategies: A Comprehensive Analysis – DrugPatentWatch – Transform Data into Market Domination, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-economics-of-generic-drug-pricing-strategies-a-comprehensive-analysis/

- International reference pricing for prescription drugs – Brookings Institution, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/international-reference-pricing-for-prescription-drugs/

- Examining Two Approaches to U.S. Drug Pricing: International Prices and Therapeutic Equivalency, accessed August 6, 2025, https://bipartisanpolicy.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Examining-Two-Approaches-to-U.S.-Drug-Pricing-1.pdf

- International reference pricing of pharmaceuticals in the United States: Implications for potentially curative treatments – PMC, accessed August 6, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10373031/

- International Reference Pricing: A Lazy, Misguided, Bi-Partisan Plan To Lower US Drug Prices | Health Affairs Forefront, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/forefront.20201130.594055/

- How to Identify Profitable Generic Drug Opportunities Using Patent Expiration Data, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/how-to-identify-profitable-generic-drug-opportunities-using-patent-expiration-data/

- Navigating the Complexities of Paragraph IV – Number Analytics, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.numberanalytics.com/blog/navigating-paragraph-iv-complexities

- NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES NO FREE LAUNCH: AT-RISK ENTRY BY GENERIC DRUG FIRMS Keith M. Drake Robert He Thomas McGuire Alice K. N, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w29131/w29131.pdf