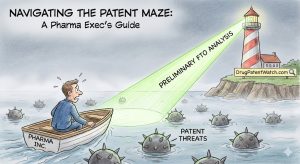

Introduction: FTO is Not a Checkbox, It’s Your Compass in the Billion-Dollar Maze

In the high-stakes world of pharmaceutical innovation, we operate in an environment of profound risk and monumental investment. The journey from a promising molecule in a lab to a life-changing therapy on the market is a decade-long marathon, fraught with scientific, regulatory, and financial hurdles. But there is one risk, often misunderstood and sometimes underestimated, that can render all other efforts meaningless: the risk of patent infringement.

The High-Stakes Reality of Pharma R&D

Let’s ground ourselves in the economic reality that defines our industry. The cost to develop a single new drug is not measured in millions, but billions. A widely cited estimate places the figure at a staggering $2.6 billion, a number that soberingly accounts for the high rate of attrition for candidates that fail along the way.1 This is not a quick venture; the entire process can take 10 to 15 years from initial discovery to regulatory approval.2

Imagine investing over a decade of your company’s brightest minds and billions of dollars in capital, only to discover at the finish line that you cannot legally sell your product. This is not a hypothetical nightmare; it is the existential threat that Freedom-to-Operate (FTO) analysis is designed to prevent. The pharmaceutical landscape is not an open field; it is a dense and treacherous “minefield of existing patents”.2 To proceed with commercialization without a clear understanding of this landscape is analogous to “building a skyscraper without checking if the land belongs to someone else”.4 The foundation of your entire commercial strategy could be built on property you don’t own.

Quantifying the Existential Risk of Infringement

This risk is not abstract. It is quantifiable, and the numbers are formidable. Patent litigation is not a remote possibility for a successful product; it is a near-certainty and a common feature of the competitive landscape.2 The direct costs alone are significant. While some analyses place the average cost of a patent lawsuit at $3 million to $4 million 4, others report it can exceed $10 million.7

But the true danger lies in the potential damages. In 2023, while the median patent damages award in the United States was $8.7 million, the highest awards have exceeded an astonishing $2 billion.2 Tellingly, the pharmaceutical industry accounted for 25% of all patent damages awarded that year, a testament to the immense value and contentious nature of our intellectual property.2 An injunction could halt your product launch indefinitely, turning billions in R&D investment into a catastrophic write-off.

The Strategic Reframe: From Legal Hurdle to Business Imperative

This is why we must reframe our entire perspective on FTO. It is not a perfunctory, check-the-box exercise to be handed off to the legal department at the last minute. It is a core strategic imperative that can determine the success or failure of a multi-billion-dollar drug program.4

The core question an FTO analysis seeks to answer is not the scientist’s query, “Can we create this invention?” It is the strategist’s far more critical question, “Can we bring this product to market legally and profitably?”.4 This distinction is fundamental. It shifts the corporate focus from pure technical feasibility to commercial viability within a competitive and litigious legal framework.

Viewed through this lens, FTO analysis becomes a powerful strategic tool. It is a “compass” that guides your innovation through the patent minefield, enabling proactive decision-making rather than reactive damage control.2 It is a high-yield “insurance policy” on your entire R&D investment, where the premium is a fraction of the potential loss.2

Introducing the Preliminary FTO: Your First Line of Defense

The good news is that you don’t need to commission a six-figure legal opinion for every idea that emerges from your labs. This guide is focused on a powerful, cost-effective first step: the preliminary FTO analysis. This is a scouting mission, an initial assessment that can and should be managed by a cross-functional internal team.

The goal of a preliminary FTO is not to generate a definitive legal opinion of non-infringement. Rather, its purpose is to perform a strategic triage: to scan the horizon, identify the most obvious and significant threats early, and allow your R&D and business strategy teams to adapt before significant capital is committed.9 It’s about spotting the icebergs while you still have time to steer the ship. By systematically integrating this preliminary analysis into your product development workflow, you can de-risk your pipeline, focus your resources, and ensure that when you do engage expensive outside counsel, their time is spent on the few critical threats that truly matter.

The Fundamental Misconception: Why Your Patent Doesn’t Grant You Freedom

Before we dive into the “how-to” of a preliminary FTO, we must dismantle the single most common and dangerous misunderstanding in the world of intellectual property. It is a misconception that is deeply intuitive, completely logical, and utterly wrong. It is the belief that obtaining a patent on your invention gives you the right to make, use, and sell it. As one legal expert aptly put it, this is “perhaps the single most misunderstood feature of patents”.10

The Core Principle: Negative vs. Positive Rights

The source of this confusion lies in the distinction between negative and positive rights. A patent is a negative right. It grants the owner the power to exclude others from making, using, selling, offering for sale, or importing the claimed invention.4 Think of it as a legal fence you can build around your technology to keep competitors out.

Crucially, a patent is not a positive right. It does not grant you, the owner, any affirmative right to practice your own invention. Your freedom to operate—your ability to actually bring your product to market—is a completely separate question, determined not by the patents you own, but by the patents owned by everyone else.

The Land Ownership Analogy

To make this concept crystal clear, let’s use a powerful analogy. Imagine you are an explorer who has discovered a new, unclaimed plot of land deep in a vast territory.

- Patentability is the process of staking your claim and getting a legal deed to that new plot of land. Once you have the deed (your patent), you have the right to stop anyone else from building on your specific plot.

- Freedom to Operate, on the other hand, is the process of surveying the entire route from the nearest road to your new plot. If the only way to access your land is by crossing a dozen other properties, each owned by someone else, your deed is of little practical use. You may own the destination, but you don’t have the right to get there. You are blocked.2

A Concrete Pharmaceutical Example

Let’s bring this back to our world. Imagine your R&D team develops a brilliant, novel extended-release formulation for Drug X, a well-known cancer drug. This new formulation is a genuine innovation—it improves patient compliance and reduces side effects. You conduct a patentability search, confirm it is new and non-obvious, and successfully obtain a patent on your new formulation. You now own the “deed” to that specific formulation.

However, a major competitor still holds a valid, in-force patent on the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) of Drug X itself—the core molecule. In this scenario, you cannot legally sell your patented formulation. Why? Because to make your product, you must necessarily use the competitor’s patented API. Doing so would be a direct act of infringement.2 Your patent is valuable—it stops the competitor from copying your specific extended-release technology—but your freedom to operate is completely blocked.

Clarifying the Terminology: FTO vs. Patentability vs. Validity Searches

This fundamental distinction is why it is strategically fatal to confuse the different types of IP searches. Using the wrong tool for the job can lead you to a false sense of security and, ultimately, a commercial disaster. The failure to differentiate between these searches is a common and costly pitfall.16 The following table provides a clear, at-a-glance reference to ensure your team is always asking the right question and conducting the right search.

Table 1: The Strategist’s IP Search Matrix

| Feature | FTO Search (Infringement/Clearance) | Patentability Search (Novelty) | Validity Search (Invalidity) |

| Core Question | “Can I make, use, or sell my product without infringing a third party’s active patent?” 4 | “Is my invention new and non-obvious? Can I get a patent?” 4 | “Is this competitor’s blocking patent actually enforceable, or can it be invalidated?” 4 |

| Scope of Search | In-force patents and published applications in specific, commercially relevant jurisdictions.4 | All publicly available “prior art” globally (patents, applications, journals, etc.), regardless of age or status.4 | A targeted search for “killer” prior art that predates the filing of the specific patent being challenged.4 |

| Key Documents | The legally binding claims of active patents.4 | The entire disclosure of any prior art reference.2 | Any document that qualifies as prior art before the target patent’s priority date.4 |

| Primary Focus | Assessing infringement risk against a specific, defined product or process.2 | Assessing novelty and non-obviousness of an inventive concept.2 | Finding prior art that invalidates an existing patent’s claims.4 |

This confusion between patentability and FTO is more than a legal nuance; it’s a strategic blind spot that can lead a company to invest hundreds of millions of dollars in developing a brilliant, patentable product that it can never legally sell. This underscores a critical organizational principle: R&D strategy and IP strategy must be inextricably linked from the moment of invention. An invention disclosure should not just trigger a patentability assessment. It must trigger two parallel and equally important workstreams: one asking “Can we protect it?” and the other asking “Can we sell it?”. One without the other is an incomplete and dangerous analysis.

The Preliminary FTO Playbook: A Phased Approach to De-Risking Innovation

Now that we’ve established the strategic “why,” let’s turn to the tactical “how.” This section provides a practical, step-by-step framework for your internal team to conduct a preliminary FTO analysis. Remember, the objective here is not to produce a formal legal opinion that can be used in court. The goal is to perform a cost-effective, strategic triage—to identify the most significant risks early in the development lifecycle, enabling you to make smarter decisions about resource allocation and R&D direction.9

Phase 1: Scoping the Mission – Defining Your Battlefield

The quality and efficiency of any FTO analysis are determined long before the first patent is ever read. This initial scoping phase is the most critical, as it sets the boundaries and defines the objectives of the entire project.2 A poorly scoped analysis will, at best, be inefficient and costly; at worst, it will provide a false sense of security by missing critical risks.

Deconstruct Your Product/Process

A robust FTO begins with a deep, granular understanding of exactly what you are clearing for market entry.18 You cannot search effectively if you don’t know what you’re looking for. Your technical and R&D teams must collaborate to break the product down into its fundamental components and features.2

- For a Small Molecule Drug: This deconstruction must be exhaustive. It includes the precise chemical structure, including any relevant salts, polymorphs, enantiomers, or prodrugs; the complete formulation, detailing all excipients, carriers, and the delivery mechanism (e.g., extended-release matrix); every critical step of the manufacturing process, including reagents and intermediates; and every intended therapeutic use, including the specific disease, patient population, and dosage regimen.2

- For a Biologic: The complexity increases. The analysis must cover the specific amino acid or nucleotide sequences of the antibody or protein; the host cells and expression systems used for production; the purification and manufacturing processes; the final formulation with stabilizers; the delivery device (e.g., auto-injector); and all methods of treatment.4

Memorialize the Subject

Because products and processes evolve significantly during the long development cycle, it is absolutely critical to create a formal, dated “Technology Document” or “Product Definition” that captures the precise state of the invention at the time of the analysis.2 An FTO analysis conducted on a preclinical formulation may be partially or completely irrelevant by the time the product enters Phase III with a new delivery system. This document serves as a clear historical record, ensuring that everyone understands exactly what was—and was not—cleared at each stage of development.18

Define Jurisdictional Scope

Patent rights are strictly territorial; a patent granted in the United States provides no protection in Europe, and vice versa.4 Therefore, an FTO analysis is strategically meaningless without clear geographic boundaries. You must limit your search to the specific countries where you intend to

manufacture, use, sell, or offer for sale the product.2 A pragmatic approach is to start with your key revenue-driving markets, which for most pharmaceutical companies will include the United States, key European countries (often searched via the European Patent Office), Japan, and increasingly, China.

Define Temporal Scope

The general rule for an FTO search is to focus on unexpired patents. Since a standard patent term is 20 years from the filing date, a common practice is to search for patents and applications filed in the last 20 to 22 years.4

However, this is one of the most dangerous corners to cut in our industry. There is a critical pharmaceutical caveat. Regulatory delays in getting a drug approved often erode a significant portion of the patent term. To compensate for this, many jurisdictions offer mechanisms to extend the life of a pharmaceutical patent. In the United States, this is called a Patent Term Extension (PTE), and in Europe, it’s a Supplementary Protection Certificate (SPC). These can add up to five years of market exclusivity beyond the standard 20-year term.4 Therefore, for any pharmaceutical FTO, the search must be extended to look back at least

25 years from the present date to avoid missing a still-enforceable patent that could block your launch.

Phase 2: Assembling the Intelligence – The Art of the Search

With a clearly defined scope, the next phase is to conduct the search itself. This requires a combination of the right tools and a sophisticated, multi-pronged search strategy. It is a delicate balance between casting a net wide enough to catch all relevant patents and narrow enough to avoid a “data dump” of thousands of irrelevant hits that will paralyze the analysis.18

The Searcher’s Toolkit: Choosing Your Weapons

A variety of databases are available, each with its own strengths and weaknesses.

- Public Databases (Free): Government-run databases like the USPTO’s Patent Public Search, the European Patent Office’s Espacenet, and the World Intellectual Property Organization’s PATENTSCOPE are indispensable for initial, broad-stroke investigations and for accessing file histories and legal status information.2 They provide comprehensive coverage and are a cost-effective starting point.

- Commercial Databases (Subscription): For any serious pharmaceutical FTO, relying solely on free databases is insufficient and borders on professional negligence. Professional-grade platforms are “non-negotiable” for a robust analysis.2 These services offer more powerful search algorithms, cleaner data, and advanced analytical tools that can dramatically improve efficiency and accuracy.

- Specialized Pharmaceutical Databases: This is where true strategic value is unlocked. Platforms like DrugPatentWatch are designed specifically for the life sciences industry. They go far beyond providing simple patent data by creating an integrated intelligence ecosystem. They link patents directly to crucial FDA regulatory data, such as Orange Book listings and marketing exclusivities. They track patent litigation in real-time at the district courts and the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB). They connect patents to clinical trial information for drugs in development and even provide data on API suppliers.20 This rich, multi-dimensional context is what transforms a technical patent search into a strategic FTO analysis.

Designing an Effective Search Strategy

A comprehensive search strategy layers several different techniques to ensure all potential threats are identified.

- Fundamental Techniques: The building blocks of any search include:

- Keyword Searching: Using a comprehensive list of technical terms, synonyms, and brand names combined with Boolean operators (AND, OR, NOT) and proximity operators (e.g., NEAR/5 to find two terms within five words of each other).33

- Patent Classification Searching: Using codes from systems like the Cooperative Patent Classification (CPC) or International Patent Classification (IPC) to find patents in a specific technological area, regardless of the keywords they use.4 This is a powerful way to overcome the limitations of keyword searching.

- Citation Searching: Once a highly relevant patent is found, analyzing its “backward citations” (the prior art it cited) and its “forward citations” (the newer patents that have cited it) can quickly uncover an entire family of related and important patents.36

- Pharma-Specific Techniques (Non-Negotiable): For new chemical entities (NCEs) and biologics, keyword searching alone is dangerously “inadequate”.4 The search

must include specialized techniques:

- Chemical Structure Searching: This involves searching for the exact chemical structure, related substructures, or the broad generic “Markush” structures that are common in pharmaceutical patents. This requires specialized databases and expertise.4

- Biosequence Searching: For biologics, the search must include a search of the specific DNA, RNA, or amino acid sequences using databases and algorithms designed for this purpose.4

- Pragmatic Starting Points: A full, comprehensive FTO search can be expensive. For a preliminary analysis, it is often wise to start with more focused, cost-effective approaches:

- Competitor-Specific Searches: Limit your initial search to the patent portfolios of your top 3-5 direct competitors. These are often the most likely source of blocking patents.24

- Feature-Specific Searches: If your product has multiple components, focus the initial search only on the most novel or commercially critical feature. This can quickly identify major roadblocks without the cost of clearing every single component.37

Phase 3: Triage and Analysis – Separating Signal from Noise

The search phase will likely yield a list of dozens, or even hundreds, of potentially relevant patents.20 The analysis phase is about efficiently and systematically reviewing this list to separate the genuine threats from the irrelevant noise.

The Golden Rule: Focus on the Claims

This is the single most important principle of FTO analysis and cannot be overstated. A patent’s power—its legal boundary—is defined exclusively by its claims, which are the numbered paragraphs at the end of the document. Infringement is determined by comparing your product to these claims, not to the descriptive text or drawings in the patent’s specification.4 An analyst who gets bogged down in the specification without focusing on the claims is wasting time and will likely arrive at the wrong conclusion.

A Primer on Claim Interpretation

While a formal legal interpretation of claim scope requires a patent attorney, your internal team can perform a powerful first-pass analysis by understanding two key elements:

- Anatomy of a Claim: A claim typically has three parts: the preamble (which introduces the invention, e.g., “A pharmaceutical composition…”), the transitional phrase, and the body (which lists the essential elements of the invention).40

- The Power of a Single Word: The choice of transitional phrase has a profound and legally defined impact on the scope of the claim.

- “Comprising”: This is the most common and broadest term. It is “open-ended,” meaning that if your product contains all the elements listed in the claim, it infringes, even if it also contains additional, unlisted elements. For example, a product containing elements A, B, and C would infringe a claim for “A composition comprising A and B”.4

- “Consisting of”: This is the most restrictive term. It is “closed-ended,” meaning the invention must have exactly the elements listed, and nothing more. In the example above, a product with A, B, and C would not infringe a claim for “A composition consisting of A and B”.40

Confirming the Threat: Patent Status and Enforceability

A patent is only a risk if it is “valid and enforceable”.4 A key step in the analysis is to verify the current legal status of each potentially problematic patent. Is it a pending application or a granted patent? Are the required maintenance fees being paid, or has it been allowed to lapse? Has it officially expired, been abandoned by the applicant, or been invalidated in a court or PTAB proceeding?.2 This information is crucial for determining if a patent poses a real, current threat. A word of caution: do not rely solely on the legal status filters in patent databases. This information can sometimes lag behind real-world events, and in some jurisdictions, an “abandoned” patent can be revived under certain circumstances.16

The Triage Process: Risk Stratification

The ultimate goal of a preliminary FTO is to sort a large volume of search results into manageable, prioritized categories.2 This triage process allows you to focus your resources—and your legal budget—on the patents that pose the most significant threat. The following framework provides a simple, actionable method for your internal team to categorize risks without making a final legal determination of infringement.

Table 2: A Practical Risk Stratification Framework

| Risk Tier | Definition | Immediate Action Required |

| High Risk | The claims appear to clearly and directly read on a core feature of your product. The patent is in-force in a key commercial jurisdiction. | Escalate immediately to patent counsel for a formal non-infringement and/or invalidity opinion. Inform R&D and halt any work that could exacerbate potential damages. |

| Medium Risk | Infringement is possible but ambiguous. It may depend on the interpretation of specific claim terms, or the patent is a pending application with claims that could be amended and granted to cover your product. | Flag for continuous monitoring of the patent’s status and claim amendments. Engage technical experts to analyze potential “design-around” options. May require targeted consultation with counsel on specific claim construction issues. |

| Low Risk | The claims are clearly not infringed (e.g., they require an essential element your product lacks). The patent is expired, abandoned (and beyond the revival period), or only in-force in an irrelevant jurisdiction. | Document the reason for clearance and archive for future reference. No immediate action needed, but the patent may still be useful for understanding the technology landscape. |

This entire preliminary FTO process is fundamentally a risk management funnel, not a legal opinion generator. Its primary function is to efficiently filter a large universe of potential patent threats down to a small, manageable number of high-risk candidates that truly require the focused attention and expense of external patent counsel. By adopting this phased approach, you make the entire FTO process more scalable and cost-effective, ensuring that your most valuable and expensive resource—specialized outside counsel—is deployed only on the most critical threats.

The Pharmaceutical Patent Thicket: A Field Guide for Executives

To effectively navigate the FTO landscape in our industry, you must understand the sophisticated and aggressive IP strategy that defines modern pharmaceutical competition. We are no longer dealing with single patents protecting single inventions. We are confronting the “patent thicket”—a dense, overlapping, and intentionally complex web of patents strategically constructed around a single blockbuster product.6 The goal is simple: to deter competition and extend market exclusivity for as long as possible, often far beyond the life of the original core patent. It is not uncommon for a single drug to be covered by more than 100 individual patents.45

The Building Blocks of the Thicket: A Taxonomy of Pharma Patent Claims

This patent fortress is built layer by layer, using different types of patent claims to protect the asset from every conceivable angle. Understanding these building blocks is essential for deconstructing a competitor’s strategy and for building a robust defensive portfolio for your own products.

Table 3: Common Pharmaceutical Patent Claim Types & Their Strategic Value

| Patent Claim Type | Description | Strategic Purpose | Example Sources |

| Composition of Matter (API) | Claims the new chemical entity (the active drug molecule) itself. | The “crown jewel” or “gold standard.” Provides the broadest and strongest protection against any generic version making, using, or selling the molecule. | 33 |

| Formulation / Composition | Claims the specific combination of the API with other ingredients (excipients, carriers, etc.) to create the final dosage form (e.g., a tablet, cream, or injectable solution). | A key lifecycle extension tool. Protects improvements like better stability, enhanced bioavailability, or improved patient experience, creating a new barrier after the API patent expires. | 42 |

| Method of Use / Treatment | Claims a specific method of using the drug, such as treating a new disease (a “second medical use”) or a specific, defined patient population. | Opens up new, patent-protected markets for an existing drug. Can block generics from being prescribed for that specific, patented use, even if the drug itself is off-patent. | 42 |

| Dosage Regimen | A specific type of use claim that covers a particular dosing amount and schedule (e.g., “administering 10mg of Compound X once daily for the treatment of hypertension”). | Can protect a newly discovered, more effective, or safer way to administer the drug, creating a barrier even if the API and formulation are off-patent. | 41 |

| Process / Method of Manufacture | Claims the specific, novel process used to synthesize or manufacture the drug. | Can prevent competitors from using a more efficient, cheaper, or purer manufacturing method, creating a significant cost or quality barrier to entry. | 43 |

| Polymorph / Crystalline Form | Claims a specific solid-state form (crystal structure) of the API. Different polymorphs of the same molecule can have different properties like stability and solubility. | A powerful “evergreening” tool. A new, more stable crystal form can often be patented long after the original API patent, potentially extending a product’s life by years. | 47 |

The Strategy of “Evergreening”

The strategic deployment of these secondary patent types is often referred to as “evergreening.” This is the practice of obtaining new patents on incremental improvements to an existing drug—such as a new formulation, a new method of use, or a new polymorph—with the explicit goal of prolonging market exclusivity.1 This is not a peripheral activity; it is a central pillar of product lifecycle management (PLM) in the pharmaceutical industry, designed to manage the financial impact of the “patent cliff” when the core API patent expires.1

Case Study in Focus: The Humira® Patent Fortress

There is no better illustration of a successful and aggressive patent thicket strategy than AbbVie’s blockbuster immunology drug, Humira®.54

- The Data: To protect its multi-billion-dollar asset, AbbVie constructed a formidable patent fortress. The company amassed a portfolio of at least 136 patents for Humira in the United States.54 A peer-reviewed study that analyzed this portfolio came to a stunning conclusion: approximately 80% of these patents were “duplicative” or non-patentably distinct from each other, linked together by a procedural mechanism called a terminal disclaimer.54

- The Commercial Impact: This dense thicket was wielded as a powerful strategic weapon. It allowed AbbVie to delay the entry of competing biosimilars in the lucrative U.S. market by at least five years compared to their launch in Europe.56 Ultimately, every biosimilar manufacturer that wanted to enter the U.S. market had to negotiate a settlement with AbbVie. These settlements allowed them to launch in 2023—a full

11 years before the last of AbbVie’s patents were set to expire.54 - The Strategic Takeaway: The Humira case provides a crucial lesson for any executive conducting an FTO analysis. The goal of a patent thicket is not necessarily to win every potential infringement lawsuit on the merits of each individual patent. Instead, the strategy is to create such a dense, complex, and overlapping web of patents that the sheer cost, time, and uncertainty of litigating through the entire thicket becomes a greater and more daunting barrier to entry than the strength of any single patent within it.55

This reality demands an evolution in how we approach FTO. A preliminary analysis that only looks at one or two “most relevant” patents is providing a dangerously incomplete picture of the true business risk. The analysis must incorporate a strategic assessment of a competitor’s entire patent portfolio to understand their “thicket strategy.” The key question is not just “Do we infringe this specific patent claim?” but “What is the overall strength and density of the competitor’s fortress, and do we have the financial and legal resources to breach it?” This elevates the FTO from a simple technical analysis to a crucial competitive intelligence function, where integrated databases like DrugPatentWatch, which track litigation history and entire company portfolios, become indispensable tools.32

When Red Flags Appear: Strategic Responses to Blocking Patents

Your preliminary FTO analysis has done its job: it has identified one or more high-risk patents that could block your path to market. This is not a dead end. It is a strategic inflection point that, if handled correctly, can still lead to a successful outcome. The key is to understand the menu of strategic options available to navigate these obstacles.14

Option 1: Design Around the Patent

This is often the most elegant and value-creating solution. A “design-around” involves proactively modifying your product, formulation, or manufacturing process to explicitly avoid the specific limitations of the competitor’s patent claims.10 This is precisely why conducting FTO analysis early in the R&D cycle is so critical. The results can directly inform and guide your scientists to innovate in the “white space”—the technological territory not covered by existing patents.4

In a pharmaceutical context, a design-around could take many forms. It might involve synthesizing a different but still therapeutically effective molecule that falls outside the scope of a competitor’s broad Markush claim. It could mean developing a novel extended-release formulation that uses different excipients than those claimed in a blocking patent. It might involve discovering and patenting a new polymorph of the API with a distinct X-ray diffraction pattern, or engineering a new, non-infringing manufacturing process to produce the drug.1 A successful design-around not only clears your path to market but can also result in new, valuable intellectual property for your own company.

Option 2: License or Acquire the Patent

If a design-around is not scientifically or commercially feasible, the most direct path forward is often to approach the patent holder to negotiate a deal. This could be a license, which is a contractual agreement granting you permission to use the patented technology in exchange for payments, or an outright acquisition of the patent.2

This path comes with significant strategic considerations. It almost always involves ongoing costs, which can include a combination of upfront payments, milestone payments tied to development progress, and/or royalties on future sales. It can also result in a loss of strategic autonomy, as the license agreement may contain restrictions on fields of use or territories.25 The timing of these negotiations is critical. Approaching a potential licensor before you have heavily invested in your clinical program often provides more leverage and can result in a more favorable deal.15

Option 3: Challenge the Patent’s Validity

This is an aggressive but potentially powerful strategy. Just because a patent has been granted does not mean it is valid and enforceable. If your analysis, with the help of counsel, suggests that the blocking patent is weak and should not have been granted in the first place (for example, because it is not truly novel or is obvious over the prior art), you can take action to have it invalidated.14

In the United States, there are two primary venues for launching such an attack:

- District Court Litigation: You can file a “declaratory judgment” action in a federal district court, asking a judge to declare the competitor’s patent invalid.

- USPTO’s Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB): You can file a post-grant proceeding at the patent office itself. The most common of these is an Inter Partes Review (IPR), which is often a faster, more streamlined, and less expensive way to challenge a patent’s validity based on prior art patents and printed publications.4

Option 4: At-Risk Launch or Strategic Delay

Finally, there are two options at the extreme ends of the risk spectrum.

- At-Risk Launch: This is a high-stakes gamble, most common in the generic drug industry. A company launches its product despite the known presence of a blocking patent, essentially betting that the patent will ultimately be found invalid or not infringed if and when they are sued. The potential upside is gaining first-mover advantage in the generic market; the potential downside is facing massive damages, including the possibility of treble damages for willful infringement.

- Strategic Delay: This is the most conservative option. It involves simply waiting for the blocking patent to expire before launching your product.14 This completely avoids litigation risk but cedes the entire market to the patent holder for the remaining life of their patent. This is typically only a viable strategy if the blocking patent is very near the end of its term.

The choice among these options is not a legal decision alone; it is a complex business decision. To aid in this process, the following table provides a high-level comparison of the trade-offs involved.

Table 4: Strategic Responses to Blocking Patents – A Comparative Analysis

| Strategic Option | Typical Cost | Time to Market | Level of Risk | Degree of Strategic Control |

| Design Around | Moderate (R&D Investment) | Delayed | Low (if successful) | High |

| License/Acquire | High (Upfront Fees/Royalties) | Fast | Low | Low (Dependent on licensor’s terms) |

| Challenge Validity | Very High (Legal Fees) | Delayed (pending outcome) | Very High (Uncertain legal outcome) | High (if successful) |

| Strategic Delay | Low (direct cost), High (opportunity cost) | Very Delayed | Very Low | None (Cedes market to competitor) |

Ultimately, the discovery of a blocking patent is not an end point but the beginning of a multi-faceted strategic conversation. The optimal response depends entirely on your company’s specific circumstances. A small, research-focused biotech with strong scientific capabilities might favor a “design around” strategy to preserve its core independence and create new IP. A large, well-capitalized pharmaceutical company with a gap in its pipeline might prefer to license or acquire a technology to accelerate its time to market. A generic manufacturer’s entire business model is predicated on challenging validity and launching “at-risk.” The preliminary FTO report should not recommend a single “correct” path. Instead, its role is to present these options as a decision tree, framing the choice in business terms that align with your company’s unique risk tolerance, financial resources, and overall corporate strategy.

Cautionary Tales and Strategic Triumphs: FTO in the Real World

The principles of Freedom-to-Operate can seem abstract. To bring them to life, let’s examine how these strategic battles have played out in the real world. These high-profile case studies—encompassing catastrophic failures, strategic masterstrokes, and landmark legal decisions—offer powerful, actionable lessons for any executive navigating the pharmaceutical IP landscape.

The PCSK9 Antibody Wars (Amgen vs. Sanofi): The Perils of Overly Broad Claims

The race to develop PCSK9 inhibitors for high cholesterol was one of the most intense therapeutic battles of the last decade, culminating in a Supreme Court decision that reshaped FTO analysis for biologics.

- The Narrative: Amgen and Sanofi were in a head-to-head race. Amgen was first to secure patents, but it did so with an ambitious claiming strategy. Instead of claiming only the specific antibodies they had created, they claimed an entire genus of antibodies defined by their function: any antibody that would bind to a specific site on the PCSK9 protein and block its activity. Their patent disclosed the specific amino acid sequences for only 26 examples but claimed a potential “universe” of millions.59 Sanofi developed its own antibody, Praluent®, which performed the same function and thus fell squarely within the broad scope of Amgen’s claims.61

- The Legal Battle: Amgen sued for infringement. After years of litigation that bounced between the district court and the Federal Circuit, the case reached the U.S. Supreme Court. In a unanimous decision, the Court invalidated Amgen’s claims. The ruling centered on the “enablement” requirement of patent law: a patent must teach a person skilled in the art how to make and use the full scope of the claimed invention without “undue experimentation.” The Court found that Amgen had not provided a reliable “roadmap” for a scientist to create the vast number of antibodies it claimed. The patent offered little more than a “research assignment” to find more functional antibodies.59

- The FTO Lesson: This case is a landmark for FTO in the biologics space. For the company performing an FTO, it provides a powerful playbook for challenging overly broad, functionally-defined patents on enablement grounds. The Amgen v. Sanofi decision has fundamentally recalibrated the risk assessment for such patents, making them more vulnerable to validity challenges.4 However, it is critical to remember that FTO is jurisdiction-specific. In a starkly different outcome, the Supreme Court of Japan upheld Amgen’s patent, found that Sanofi’s Praluent did infringe, and issued an injunction prohibiting its sale in Japan.62 This highlights the absolute necessity of conducting separate, expert FTO analyses for each key commercial market.

The Story of Lipitor®: A Masterclass in Proactive Lifecycle Management

Pfizer’s Lipitor®, one of the best-selling drugs in history, provides a masterclass not just in marketing, but in proactive IP and commercial strategy to manage the dreaded “patent cliff.”

- The Narrative: Lipitor generated over $125 billion in revenue for Pfizer over 14 years, but the company faced a massive revenue decline when its core U.S. patent expired in 2011.63

- The Strategy: Pfizer’s response was a brilliant, multi-layered campaign that began years before the patent expired.

- Pre-Expiry: They engaged in aggressive direct-to-consumer marketing to build immense brand loyalty, used competitive pricing strategies, and pursued legal actions to delay the entry of generics.63

- Post-Expiry: The fight didn’t end when the patent did. Pfizer continued to market the branded drug, offered significant rebates to pharmacy benefit managers, launched its own “authorized generic” to capture a portion of the generic market, and even explored switching Lipitor to over-the-counter status.63

- The FTO Lesson: This case demonstrates that FTO is not a one-time, pre-launch event. It is a continuous intelligence-gathering process that must inform the entire product lifecycle. By constantly monitoring the patent landscape, the regulatory environment, and the competitive field, a company can anticipate threats and proactively deploy a full suite of commercial and legal strategies to defend its market position long after the core IP has expired. The Lipitor case also provides a fascinating sidebar on the broader challenges of brand protection, including a massive recall of counterfeit tablets that had infiltrated the legitimate U.S. supply chain, underscoring the need for vigilance beyond just patent infringement.64

The Gilead/Merck Sovaldi® Dispute: The $2.5 Billion Due Diligence Failure

This case serves as a stark and costly cautionary tale about the critical role of FTO in mergers, acquisitions, and in-licensing deals.

- The Narrative: In a stunning 2016 verdict, a federal jury ordered Gilead Sciences to pay Merck & Co. $2.54 billion in damages—one of the largest patent infringement awards in history. The reason: Gilead’s blockbuster hepatitis C drug, Sovaldi®, was found to infringe a patent that Merck had obtained when it acquired a smaller biotech company, Idenix Pharmaceuticals, in 2014.65

- The Core Issue: The dispute hinged on the scientific origin of sofosbuvir, the active molecule in Sovaldi. Gilead had acquired the drug through its $11 billion purchase of Pharmasset in 2011. However, Merck successfully argued that Pharmasset’s scientists had built upon foundational, patented work from Idenix related to a specific class of nucleoside analogs for treating viruses.65

- The FTO Lesson: This is a brutal illustration of the consequences of an incomplete FTO analysis during M&A due diligence. A superficial FTO that only looks at the target company’s own patent portfolio is not enough. The analysis must be a deep, forensic investigation into the intellectual property provenance of the asset. Acquirers and licensees must uncover and assess not just the target’s patents, but also any potential liabilities or dependencies on third-party IP that could emerge later. A $2.54 billion verdict can instantly turn a brilliant, strategic acquisition into a corporate disaster.

These real-world cases reveal that major FTO failures are rarely simple oversights. They are complex failures of strategic judgment: overestimating the legal strength of one’s own broad claims (Amgen), underestimating the hidden IP history of an acquired asset (Gilead), or failing to view FTO as a continuous, lifecycle-long process (the inverse of Pfizer’s Lipitor success). A preliminary FTO must therefore be a dynamic, strategic process. It must ask sophisticated questions that go beyond simple infringement: How will recent legal precedents like Amgen v. Sanofi affect the enforceability of this competitor’s patent? What is the complete IP lineage of this in-licensing candidate? What is our long-term plan to defend this asset’s market share, even after the patents begin to expire?

The Business Case for FTO: Calculating ROI and Communicating Risk

You understand the strategic importance of FTO. You have a playbook for conducting a preliminary analysis. The final, critical step is to effectively champion the value of FTO within your organization. This section provides the tools to move the conversation from the “how” to the “why,” focusing on justifying the investment and communicating the results to non-legal stakeholders like the C-suite, the board of directors, and investors.

A Pragmatic Framework for FTO ROI

Trying to calculate a traditional, positive ROI for a risk mitigation activity can be challenging. The most powerful way to frame the financial value of FTO is not by the revenue it generates, but by the catastrophic losses it prevents. This is the “Cost of Inaction” model.

We can articulate this with a simple but powerful conceptual equation:

ROI=(Cost of FTO Analysis)(Avoided Litigation Costs+Avoided Damages+Avoided Lost Revenue from Injunction+Preserved Value of M&A/Financing Deal)

Now, let’s plug in the realistic numbers we’ve gathered. A comprehensive FTO analysis for a biopharmaceutical asset might cost anywhere from $50,000 for an early-stage target to over $500,000 for a complex, late-stage drug candidate.2 This is your denominator—the investment.

For the numerator—the potential loss—the numbers are orders of magnitude larger. You are avoiding $3 million to $10 million in average litigation costs.6 You are avoiding a median damages award of $8.7 million, with a worst-case scenario exceeding $2 billion.2 Most importantly, you are protecting the entire sunk R&D cost of the asset, which averages $2.6 billion.1

The result is an ROI that is demonstrably massive. The FTO analysis is a rounding error compared to the existential risk it mitigates. It is not a legal expense; it is a high-yield insurance policy on your entire R&D investment.2

A company can develop a novel, patentable improvement to an existing technology but still infringe a broader, underlying patent that covers the core technology. For example, one could invent and patent a new, more efficient formulation for a known drug. However, if another company holds an unexpired patent on the drug itself, the new formulation cannot be commercialized without a license.

2

FTO as a Gateway to Capital and Growth: The Investor and M&A Perspective

In the capital-intensive world of biotech and pharma, FTO is not just an internal risk management tool; it is a critical external-facing asset. Investors, partners, and acquirers are fundamentally risk-averse. They will not deploy significant capital into a company or an asset without clear assurances that it has a viable path to market.11

A clean FTO analysis is often a non-negotiable condition for closing an investment round or an acquisition deal.14 It is a mandatory and complex part of any serious M&A due diligence process.11 Presenting a proactive, well-documented FTO file to a potential partner or investor demonstrates competent management and significantly de-risks the transaction in their eyes.

Furthermore, there is a powerful legal benefit that resonates strongly with boards and investors: the “willful infringement” shield. In U.S. patent law, if a company is found to have willfully infringed a patent (i.e., they knew about the patent and infringed anyway), a court has the discretion to award enhanced damages, up to three times the actual damages. A formal, well-reasoned FTO opinion from a qualified patent attorney is the single most powerful piece of evidence to defend against such an allegation. It demonstrates that the company acted in good faith, sought competent legal advice, and believed it was not infringing, making a finding of willfulness much less likely.2

The Art of Translation: Communicating Patent Risk to the C-Suite and Board

The output of a preliminary FTO analysis for an executive audience should not be a dense, 50-page legal memorandum. To be effective, the findings must be translated into the language of business.70

Here are three actionable frameworks for this translation:

- Use the Risk Stratification Framework: Present the findings visually using the High, Medium, and Low-Risk categories. This provides a clear, immediate, and intuitive snapshot of the threat landscape without getting bogged down in legal jargon.

- Present Strategic Options as a Decision Tree: Frame the response to a high-risk patent not as a legal problem, but as a business decision. Use the comparative analysis table (Design Around vs. License vs. Challenge vs. Wait) to clearly lay out the potential paths forward, with the associated costs, timelines, and risks for each.

- Integrate into Enterprise Risk Management (ERM): Boards and audit committees are fluent in the language of ERM. Position patent and IP risk alongside other familiar categories like financial risk, operational risk, and market risk.72 This contextualizes the threat in a framework that senior leadership already uses for strategic decision-making and governance.

Finally, remember that transparency builds trust. Proactive and clear disclosure of patent risks in SEC filings and investor communications is not a sign of weakness. It is a sign of competent, forward-looking management. It builds credibility, controls the narrative, and prevents the kind of market-shaking surprises that can destroy shareholder value.70 The ultimate function of a preliminary FTO analysis within a corporate structure is to

translate complex, ambiguous legal risk into quantifiable, actionable business intelligence. This act of translation is what empowers senior leaders to make sound strategic decisions that protect and grow the company.

Conclusion: From Defense to Offense – Making FTO Your Strategic Advantage

We began this guide by challenging the conventional view of Freedom-to-Operate analysis as a purely defensive, cost-centric legal hurdle. We have deconstructed its core principles, provided a practical playbook for its execution, and explored its strategic implications through real-world case studies. The journey leads to an undeniable conclusion: preliminary FTO analysis, when integrated deeply into a company’s strategic fabric, transcends its defensive origins. It becomes a powerful offensive weapon for creating and sustaining a competitive advantage.

Let’s revisit the strategic benefits that this proactive approach unlocks:

- It de-risks the multi-billion-dollar R&D investments that are the lifeblood of our industry, protecting them from being nullified by a competitor’s intellectual property.

- It guides R&D efforts away from crowded, litigious, and high-risk technological areas. More importantly, it illuminates the “white space”—areas of low patent density that are ripe for breakthrough innovation and the creation of a dominant, defensible IP position.4

- It informs business development and M&A strategy by identifying potential in-licensing targets, uncovering hidden risks in acquisition candidates, and strengthening your negotiating position in partnership discussions.68

- It builds crucial confidence with the investors, partners, and public markets that fuel your company’s growth, demonstrating a sophisticated and proactive approach to risk management.14

The final message is a clear call to action for the leaders and strategists in this industry. Do not treat FTO as an isolated event. Instead, embed a culture of proactive, continuous, and iterative FTO analysis into the very fabric of your organization. It must begin at the earliest stages of research, when you have the maximum flexibility to adapt and innovate, and it must continue as a living process throughout the entire product lifecycle.5 By doing so, you will transform FTO from a shield you occasionally raise into a sword you constantly wield, carving a clear and profitable path to market for the innovations that will define the future of medicine.

Key Takeaways

- Your Patent is Not a Pass to Market: Owning a patent gives you the right to stop others; it does not give you the right to sell your product. Freedom-to-Operate is the separate, critical analysis that determines if you can commercialize without infringing on someone else’s patent rights.

- FTO is a High-ROI Investment, Not a Cost: The modest cost of a preliminary FTO analysis is dwarfed by the multi-million-dollar litigation expenses and potentially multi-billion-dollar damages it helps you avoid. It is an essential insurance policy on your R&D investment.

- Start Early, Iterate Often: Conduct preliminary FTOs at the earliest stages of R&D when you have maximum flexibility to “design around” problems. Revisit and update the analysis at key development milestones, as both your product and the patent landscape will evolve.

- Think Like a Strategist, Not Just a Scientist: Deconstruct your product into all its potentially patentable elements (API, formulation, method of use, manufacturing process, etc.) and analyze the competitive “patent thicket,” not just a single, isolated patent.

- Translate Legal Risk into Business Language: Use clear, actionable frameworks like risk stratification (High/Medium/Low), comparative analysis of strategic options, and ROI calculations to communicate FTO findings to the C-suite and investors in a way that drives decisive, informed action.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. Q: We have a “composition of matter” patent on our new molecule, which is considered the strongest type of protection. Why do we still need to worry so much about an FTO analysis?

A: This is an excellent question that goes to the heart of a common misconception. While a composition of matter patent on your Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) is indeed the “gold standard” of protection, it only protects that specific molecule. It does not give you a clear path to market. You still face significant FTO risks from several angles:

- Broader Genus Patents: A competitor may have an older, broader “genus” or “Markush” patent that claims a whole class of related chemical structures, and your specific molecule might fall within that claimed class.

- Formulation and Delivery Patents: The final drug product is more than just the API. It includes excipients, delivery systems (e.g., nanoparticles, extended-release matrices), and other formulation technologies. These components are often covered by third-party patents that you could infringe simply by formulating your drug for delivery to patients.42

- Method of Use Patents: Your intended therapeutic indication could be blocked. A competitor may have a patent on the method of treating a specific disease with any compound that works through a certain biological mechanism, and your drug may fall under that method patent.50

- Manufacturing Process Patents: Even the way you synthesize your patented molecule could infringe on someone else’s patented process.

In short, your strong patent is your shield; FTO analysis is your map through the minefield of everyone else’s shields.14

2. Q: Our product is still in early preclinical development and the final formulation and manufacturing process are likely to change. Isn’t it too early and a waste of money to conduct an FTO now?

A: On the contrary, the early preclinical stage is the most cost-effective and strategically important time to conduct a preliminary FTO analysis.5 The key is to understand the goal at this stage. You are not trying to get a final clearance for a product that doesn’t exist yet. Instead, you are using FTO as a strategic R&D guidance tool. An early FTO allows you to:

- Identify Major Roadblocks: You can identify any fundamental patents (e.g., on the core molecule or target mechanism) that would be “showstoppers” before you invest millions in preclinical and clinical development.

- Enable “Design-Arounds”: This is the critical advantage of an early search. When your formulation and manufacturing processes are still flexible, your scientists have the maximum freedom to innovate around any blocking patents that are discovered. Waiting until Phase III, when these aspects are locked in, makes designing around exponentially more difficult and expensive.10

- Map the “White Space”: An early landscape analysis can reveal which areas of the technology are less crowded with patents, guiding your R&D team towards more defensible and valuable innovation pathways.4

Think of it as looking at a map before you start a long journey, rather than waiting until you’re halfway there to see if the road ahead is closed.

3. Q: Our internal preliminary FTO flagged a competitor’s patent as “medium risk.” What are the immediate, cost-effective next steps our team should take before we engage a law firm for a full, expensive opinion?

A: A “medium risk” finding is a crucial output of a preliminary FTO, and managing it effectively is key to controlling costs. Before escalating to outside counsel, your internal team can take several valuable steps:

- Deepen the Technical Analysis: Engage your R&D scientists. Can they definitively confirm whether a specific, ambiguous claim element is present or absent in your product? Their technical expertise can often resolve ambiguities that a non-scientist might struggle with.

- Initiate a “Design-Around” Brainstorm: Task your technical team with exploring the feasibility of modifying the product to clearly avoid the problematic claim. What would it take? What would be the impact on efficacy, cost, and timeline? Having these options on the table is invaluable.

- Monitor the Patent’s Status: If the medium-risk patent is a pending application, set up an alert system (many databases, including those from DrugPatentWatch, offer this) to track its prosecution.2 You need to know immediately if the claims are amended in a way that increases or decreases the risk to your product.

- Conduct a Targeted Validity Search: While a full invalidity opinion is expensive, your team can conduct a preliminary search for “knockout” prior art that might obviously invalidate the competitor’s patent. Finding a clear piece of prior art that was missed by the examiner can dramatically change your risk assessment and negotiating leverage.

These steps transform you from being a passive recipient of a legal problem into an active manager of a business risk, ensuring that when you do talk to your lawyers, the conversation is focused, efficient, and strategic.

4. Q: How has the Supreme Court’s decision in Amgen v. Sanofi changed the way we should approach FTO analysis for our biologic pipeline? Does it create more risk or more opportunity?

A: The Amgen v. Sanofi decision is a game-changer for biologics FTO, and it creates both opportunity and risk. The case significantly strengthened the “enablement” requirement for broad, functionally-defined patent claims—claims that cover a whole class of antibodies based on what they do rather than what they are.59

- The Opportunity: For companies developing biosimilars or new biologics, this decision provides a powerful new weapon to challenge the broad genus patents held by innovator companies. If you are blocked by a patent that claims a vast “universe” of antibodies but only discloses a few specific examples, you now have a much stronger argument that the patent is invalid for lack of enablement. Your FTO analysis should now include a specific assessment of the blocking patent’s vulnerability on these grounds.

- The Risk: For innovator companies, the risk is that your own broad patent claims may be more vulnerable than you previously thought. The decision makes it harder to secure and defend patents that attempt to lock up an entire therapeutic target with a single filing. It places a higher burden on innovators to fully describe and enable a representative number of species within the genus they are trying to claim. Your own FTO—when assessing the strength of your portfolio to deter competitors—must now look more critically at your own patents through the lens of this heightened enablement standard.

5. Q: We are in the due diligence phase of in-licensing a promising clinical-stage asset from a university. What are the top three FTO-related red flags we should be looking for that are often missed in academic spin-outs?

A: In-licensing from academia is a fantastic source of innovation, but it comes with unique IP risks. A thorough FTO due diligence process is essential.2 Here are three common red flags:

- Incomplete Inventorship: In a collaborative academic environment, it’s easy for a contributing scientist (from the same lab, a different department, or even another university) to be left off a patent application. If an unnamed inventor made a conceptual contribution to any of the patent’s claims, the patent could be declared invalid. Your due diligence must include interviewing all involved scientists to reconstruct the invention’s history and confirm inventorship is correct.

- “Myopic” Patent Filing: Universities often have limited budgets for patent prosecution. They may have filed a strong patent in the U.S. but neglected to file in key international markets like Europe or Japan. This creates a situation where the asset has significant FTO gaps, and competitors could be free to launch in major markets outside the U.S. You must verify the full geographic scope of the patent portfolio.

- Ignoring Third-Party Rights and “Reach-Through” Claims: Academic research is often funded by government grants or uses proprietary research tools (e.g., cell lines, reagents) acquired from third parties under Material Transfer Agreements (MTAs). These agreements can contain “reach-through” provisions that give the government or the third-party tool provider rights to the resulting inventions, or a claim on future royalties. Your FTO analysis must include a review of all grant funding agreements and MTAs to ensure the university has clear, unencumbered title to the IP they are licensing to you.

Works cited

- How Drug Life-Cycle Management Patent Strategies May Impact Formulary Management, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.ajmc.com/view/a636-article

- Conducting a Biopharmaceutical Freedom-to-Operate (FTO) Analysis: Strategies for Efficient and Robust Results – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/conducting-a-biopharmaceutical-freedom-to-operate-fto-analysis-strategies-for-efficient-and-robust-results/

- Patent cliff and strategic switch: exploring strategic design possibilities in the pharmaceutical industry – PMC, accessed August 16, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4899342/

- How to Conduct a Drug Patent FTO Search: A Strategic and Tactical Guide to Pharmaceutical Freedom to Operate (FTO) Analysis – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/how-to-conduct-a-drug-patent-fto-search/

- When Is a “Freedom to Operate” Opinion Cost-Effective? | Articles – Finnegan, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.finnegan.com/en/insights/articles/when-is-a-freedom-to-operate-opinion-cost-effective.html

- 5 Ways to Predict Patent Litigation Outcomes – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/5-ways-to-predict-patent-litigation-outcomes/

- Pharmaceutical Companies Can Cut Patent Litigation Costs by 50%, Drug Patent Watch Reports – GeneOnline News, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.geneonline.com/pharmaceutical-companies-can-cut-patent-litigation-costs-by-50-drug-patent-watch-reports/

- Freedom to Operate: How to Safely Launch Products – UpCounsel, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.upcounsel.com/freedom-to-operate

- Patent blog: Convince investors with your Freedom to Operate (FTO) Analysis | RVO.nl, accessed August 16, 2025, https://english.rvo.nl/blogs/convince-investors-your-freedom-operate

- Patentability vs. Freedom-to-Operate – Buckley King, accessed August 16, 2025, https://buckleyking.com/patentability-vs-freedom-to-operate/

- Patent Freedom-to-Operate – What is it and When is it Needed? | Masuda Funai, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.masudafunai.com/articles/patent-freedom-to-operate-what-is-it-and-when-is-it-needed

- Tool 5 Freedom to Operate – WIPO, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.wipo.int/documents/d/tisc/docs-en-tisc-toolkit-freedom-to-operate-description.pdf

- Patent Searches and Opinions: Patentability vs. Freedom to Operate – Heer Law, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.heerlaw.com/patent-search-patentability-freedom-to-operate

- Freedom to Operate – Fish & Richardson, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.fr.com/insights/ip-law-essentials/freedom-to-operate/

- Managing 3rd Party IP and Freedom to Operate in Drug Development | JD Supra, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.jdsupra.com/legalnews/managing-3rd-party-ip-and-freedom-to-9360436/

- Avoiding 5 Pitfalls in Freedom to Operate Analyses – TT Consultants, accessed August 16, 2025, https://ttconsultants.com/introduction-to-5-common-pitfalls-in-freedom-to-operate-analyses/

- 5 Frequent Pitfalls of Freedom To Operate Analyses – Ensemble IP, accessed August 16, 2025, https://ensembleip.com/5-frequent-pitfalls-of-freedom-to-operate-analyses/

- Freedom to Operate Analysis Three Strategies to Efficiently Achieve Robust Results, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.bakerbotts.com/thought-leadership/publications/2023/march/freedom-to-operate-analysis-three-strategies-to-efficiently-achieve-robust-results

- (PDF) TECHNOLOGY TRANSFER MANAGEMENT IN PHARMACEUTICAL INDUSTRY THROUGH FREEDOM TO OPERATE (FTO) UTILIZATION – ResearchGate, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/353429673_TECHNOLOGY_TRANSFER_MANAGEMENT_IN_PHARMACEUTICAL_INDUSTRY_THROUGH_FREEDOM_TO_OPERATE_FTO_UTILIZATION

- Freedom to Operate FTO Search on Pharmaceutical Formulations, accessed August 16, 2025, https://sagaciousresearch.com/blog/freedom-to-operate-fto-search-pharmaceutical-formulations/

- Biopharmaceutical FTO Analysis: APIs and Formulations Scrutinized to Minimize Patent Infringement Risk. – GeneOnline News, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.geneonline.com/biopharmaceutical-fto-analysis-apis-and-formulations-scrutinized-to-minimize-patent-infringement-risk/

- Freedom-to-Operate (FTO) Analysis – Puchberger & Partner Patentanwälte, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.puchberger.at/en/services/freedom-to-operate-fto-analysis/

- Three Keys Strategies To Effective FTO Management | ClearstoneIP, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.clearstoneip.com/news-articles/three-keys-to-effective-freedom-to-operate-management

- What is Freedom to Operate (FTO) in relation to patents and IP? | US – Murgitroyd, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.murgitroyd.com/us/insights/patents/what-is-freedom-to-operate-fto-in-relation-to-patents-and-ip

- Le gisement de l’innovation – WIPO, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.wipo.int/web/wipo-magazine/articles/ip-and-business-launching-a-new-product-freedom-to-operate-34956

- Considerations for combined Patentability and Freedom to Operate (FTO) Searches, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.tprinternational.com/combined-patentability-and-freedom-to-operate-fto-search/

- Drug Patent Watch: USPTO and EPO Databases Key for Pharmaceutical Patent Searches, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.geneonline.com/drug-patent-watch-uspto-and-epo-databases-key-for-pharmaceutical-patent-searches/

- Pharmaceutical Professionals Use USPTO and EPO in Drug Patent Searches. – GeneOnline, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.geneonline.com/pharmaceutical-professionals-use-uspto-and-epo-in-drug-patent-searches/

- Espacenet – patent search | epo.org, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.epo.org/en/searching-for-patents/technical/espacenet

- Patents – World Health Organization (WHO), accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.who.int/observatories/global-observatory-on-health-research-and-development/resources/databases/databases-on-processes-for-r-d/patents

- PATENTSCOPE – WIPO, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.wipo.int/en/web/patentscope

- DrugPatentWatch | Software Reviews & Alternatives – Crozdesk, accessed August 16, 2025, https://crozdesk.com/software/drugpatentwatch

- A Business Professional’s Guide to Drug Patent Searching – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-basics-of-drug-patent-searching/

- Transforming Expired and Abandoned Patents into a Strategic Pharma Asset – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/abandoned-and-expired-patents-in-pharma-manufacturing/

- DrugPatentWatch’s rapid research capabilities have elevated our …, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/

- How to Conduct a Freedom to Operate (FTO) Search? – SciTech Patent Art Services, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.patent-art.com/how-to-conduct-a-freedom-to-operate-fto-search/

- FTO analysis and patent due diligence in Canada – Smart & Biggar, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.smartbiggar.ca/insights/publication/what-is-a-freedom-to-operate-analysis-

- FTO Search: A Cog in the Wheel of Patent Strategy – Sagacious IP, accessed August 16, 2025, https://sagaciousresearch.com/blog/fto-search-a-cog-in-the-wheel-of-patent-strategy/

- IP: Writing a Freedom to Operate Analysis – InterSECT Job Simulations, accessed August 16, 2025, https://intersectjobsims.com/library/fto-analysis/

- PATENT CLAIM FORMAT AND TYPES OF CLAIMS – WIPO, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.wipo.int/edocs/mdocs/aspac/en/wipo_ip_phl_16/wipo_ip_phl_16_t5.pdf

- Drafting Detailed Drug Patent Claims: The Art and Science of Pharmaceutical IP Protection, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/drafting-detailed-drug-patent-claims-the-art-and-science-of-pharmaceutical-ip-protection/

- The value of method of use patent claims in protecting your therapeutic assets, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-value-of-method-of-use-patent-claims-in-protecting-your-therapeutic-assets/

- Optimizing Your Drug Patent Strategy: A Comprehensive Guide for Pharmaceutical Companies – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/optimizing-your-drug-patent-strategy-a-comprehensive-guide-for-pharmaceutical-companies/

- STAT quotes Sherkow on pharmaceutical patents – College of Law, accessed August 16, 2025, https://law.illinois.edu/stat-quotes-sherkow-on-pharmaceutical-patents/

- Pharmaceutical Patent Regulation in the United States – The Actuary Magazine, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.theactuarymagazine.org/pharmaceutical-patent-regulation-in-the-united-states/

- Types of Pharmaceutical Patents, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.obrienpatents.com/types-pharmaceutical-patents/

- Using Solid Form Patents to Protect Pharmaceutical Products — Part I – Barash Law, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.ebarashlaw.com/insights/part1

- What are the types of pharmaceutical patents? – Patsnap Synapse, accessed August 16, 2025, https://synapse.patsnap.com/blog/what-are-the-types-of-pharmaceutical-patents

- Formulation Patents and Dermatology and Obviousness – PMC, accessed August 16, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3857063/

- What is the difference between a composition claim and a method of use claim?, accessed August 16, 2025, https://wysebridge.com/what-is-the-difference-between-a-composition-claim-and-a-method-of-use-claim

- Do Patent Claims to Methods of Treatment Cover In Vivo Transformations? – Mintz, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.mintz.com/insights-center/viewpoints/2231/2024-04-29-do-patent-claims-methods-treatment-cover-vivo

- Patenting Life Sciences Technologies | Pearce IP, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.pearceip.law/2024/06/26/patenting-life-sciences-technologies/

- How to manage FTO for Pharmaceutical Industry?, accessed August 16, 2025, https://blog.logicapt.com/fto-in-pharmaceutical-industry/

- Patent Settlements Are Necessary To Help Combat Patent Thickets, accessed August 16, 2025, https://accessiblemeds.org/resources/blog/patent-settlements-are-necessary-to-help-combat-patent-thickets/

- Biological patent thickets and delayed access to biosimilars, an American problem | Journal of Law and the Biosciences | Oxford Academic, accessed August 16, 2025, https://academic.oup.com/jlb/article/9/2/lsac022/6680093

- Combating Pharmaceutical Patent Thickets In The Trump Administration – Health Affairs, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.healthaffairs.org/content/forefront/combating-pharmaceutical-patent-thickets-trump-administration

- Freedom to Operate Opinions: What Are They, and Why Are They Important? | Intellectual Property Law Client Alert – Dickinson Wright, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.dickinson-wright.com/news-alerts/arndt-freedom-to-operate-opinions

- Statistics | USPTO, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.uspto.gov/patents/ptab/statistics

- Amgen Inc. v. Sanofi – Food and Drug Law Institute (FDLI), accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.fdli.org/2024/05/amgen-inc-v-sanofi/

- 21-757 Amgen Inc. v. Sanofi (05/18/23) – Supreme Court, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/22pdf/21-757_k5g1.pdf

- Amgen Inc. v. Sanofi, No. 17-1480 (Fed. Cir. 2017) – Justia Law, accessed August 16, 2025, https://law.justia.com/cases/federal/appellate-courts/cafc/17-1480/17-1480-2017-10-05.html

- Amgen Comments On the Supreme Court of Japan Ruling On PCSK9 Patent Infringement Litigation, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.amgen.com/newsroom/company-statements/amgen-comments-on-the-supreme-court-of-japan-ruling-on-pcsk9-patent-infringement-litigation

- Managing the challenges of pharmaceutical patent expiry: a case study of Lipitor, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/309540780_Managing_the_challenges_of_pharmaceutical_patent_expiry_a_case_study_of_Lipitor

- Case Study: Lipitor® US Recall | Pfizer, accessed August 16, 2025, https://cdn.pfizer.com/pfizercom/products/LipitorUSRecall.pdf

- Merck wins patent case against Gilead | C&EN Global Enterprise – ACS Publications, accessed August 16, 2025, https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/cen-09501-buscon001

- 5 Role of intellectual property in biotechnology commercialization – WIPO, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.wipo.int/web-publications/a-primer-on-technology-transfer-in-the-field-of-biotechnology/en/5-role-of-intellectual-property-in-biotechnology-commercialization.html

- Top 5 IP Considerations for Medical Device Startups – Why Cognition IP?, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.cognitionip.com/top-5-ip-considerations-for-medical-device-startups/

- Freedom to Operate (FTO) Search – SciTech Patent Art Services, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.patent-art.com/ip-search-analysis/freedom-to-operate-search/

- IP in Pharma and Biotech M&A: What Makes It So Complex | PatentPC, accessed August 16, 2025, https://patentpc.com/blog/ip-in-pharma-and-biotech-ma-what-makes-it-so-complex

- Understanding the Role of Patent Risks in SEC Risk Factor Disclosures, accessed August 16, 2025, https://patentpc.com/blog/understanding-the-role-of-patent-risks-in-sec-risk-factor-disclosures

- Patent Risk Assessment Strategies for Private Equity Investors, accessed August 16, 2025, https://patentpc.com/blog/patent-risk-assessment-strategies-for-private-equity-investors

- ERM for Owners of Intellectual Property (IP) – University of Minnesota’s Carlson School of Management, accessed August 16, 2025, https://carlsonschool.umn.edu/sites/carlsonschool.umn.edu/files/2018-10/IP%20Chapter%2012-30.pdf

- Ultimate Pharma & Biotech Partnering and Out-licensing Dealmaking Guide, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.biopharmavantage.com/guide-out-licensing-pharma-biotech

- What is Freedom To Operate? – Why Cognition IP?, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.cognitionip.com/what-is-freedom-to-operate-and-why-does-it-matter-to-med-device-startups/