Introduction: Beyond the “Patent Death Squad” Hype

Let’s be honest. For more than a decade, the very mention of the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) has sent a chill down the spine of pharmaceutical patent owners. Since its creation, it has been saddled with a fearsome moniker, one that echoes in boardrooms and strategy sessions across the industry: the “patent death squad”.1 This label, famously coined by former Federal Circuit Chief Judge Randall Rader, conjures images of an indiscriminate tribunal, a place where valuable, hard-won intellectual property goes to die.4 The anxiety is understandable. The pharmaceutical business model—an economic engine built on the promise of market exclusivity to recoup billions in R&D investment—is uniquely vulnerable to patent invalidation.5

But is this narrative, now more than a decade old, still accurate? How safe is your drug patent, really, from a PTAB challenge? The truth, as is often the case, is far more nuanced, more complex, and frankly, more strategically interesting than the headlines suggest. The PTAB is not a simple guillotine; it is a highly specialized gauntlet. It is a battleground with its own unique rules of engagement, its own statistical realities, and its own procedural tripwires. For the unprepared, it can be fatal. But for the strategic, for those who understand its intricacies and can read the data behind the drama, it presents an opportunity to not only defend a portfolio but to forge it into a more resilient, more formidable competitive weapon.7

This report is designed for you—the seasoned executive, the in-house counsel, the R&D leader, the investor, the law firm partner. You are skeptical of hype and demand hard data. You need to translate complex legal frameworks into actionable business strategy and clear ROI. Over the next several sections, we will move beyond the “death squad” narrative to conduct a deep, strategic dissection of the PTAB. We will begin by understanding the arena itself—why Congress created the PTAB and how its authority was forged in the crucible of constitutional challenges. We will then master the weapons of choice, providing a detailed breakdown of its primary challenge mechanisms: Inter Partes Review (IPR) and Post-Grant Review (PGR).

Crucially, we will turn to the scorecard. We will analyze years of USPTO data to reveal what really happens to pharmaceutical and biologic patents at the PTAB, debunking myths and uncovering the trends that matter. From there, we will enter the war room, dissecting landmark case studies—from the epic siege of AbbVie’s Humira to the evolving battlegrounds of obviousness and written description—to extract priceless strategic lessons. Finally, we will equip you with a practical playbook, offering proactive and reactive strategies for both defending your IP fortress and, for those on the other side of the aisle, identifying and exploiting a competitor’s weakest link. We will conclude by looking over the horizon at the shifting legal and legislative landscape that will define the PTAB of tomorrow. Welcome to the gauntlet. Let’s begin.

Part I: Understanding the Arena – The Anatomy of the PTAB

To master the PTAB, you must first understand its DNA. It wasn’t born in a vacuum; it was forged by a specific set of problems and endowed with a clear, if controversial, mandate. Its structure, its power, and its very legitimacy have been tested and affirmed at the highest levels, cementing its role as a permanent and powerful fixture in the U.S. patent ecosystem.

The Genesis of the PTAB: A Congressional Cure for “Bad Patents”

Before 2012, the landscape for challenging an issued patent was, to put it mildly, treacherous. The primary venue was federal district court, a forum notorious for its staggering costs, protracted timelines, and the high burden of proof required to invalidate a patent.8 An issued patent carried a strong presumption of validity, and a challenger had to overcome this with “clear and convincing evidence”.1 For many companies, especially small and mid-sized enterprises facing infringement suits from Non-Practicing Entities (NPEs), or “patent trolls,” the sheer expense of litigation made challenging even a weak or “improperly granted” patent economically unfeasible.8 The existing administrative options, like

ex parte and inter partes reexamination, were widely seen as slow, inefficient, and lacking the procedural rigor of a true adversarial proceeding.4

This confluence of factors—prohibitive litigation costs, inefficient administrative reviews, and the strategic use of questionable patents—created a drag on innovation and a consensus that reform was desperately needed.5 Congress’s response was the Leahy-Smith America Invents Act (AIA), the most significant overhaul of U.S. patent law in over half a century.1 Signed into law in 2011, the AIA is most famous for shifting the U.S. from a “first-to-invent” to a “first-inventor-to-file” system.8 However, its most practically significant change was the creation of the Patent Trial and Appeal Board, which officially came into being on September 16, 2012, replacing the old Board of Patent Appeals and Interferences (BPAI).9

The AIA endowed the PTAB with a clear mandate: to improve patent quality and provide a faster, more efficient, and more affordable administrative alternative to district court for adjudicating patent validity.1 This represented a fundamental philosophical shift. The grant of a U.S. patent was no longer to be treated as a nearly final government act. Instead, the AIA created a powerful administrative body within the USPTO itself, staffed by experts, that could re-evaluate a patent’s validity without a presumption of validity and using a lower “preponderance of the evidence” standard.9 In essence, Congress decided that the USPTO, which grants patents, should also have a robust mechanism to correct its own mistakes.

Meet the Adjudicators: The Administrative Patent Judges (APJs)

A critical piece of the PTAB’s design, and a key reason for the deference it receives, is the nature of its decision-makers. Unlike a district court jury, which may struggle with the dense, technical subject matter of a pharmaceutical patent case, PTAB trials are adjudicated by a panel of three Administrative Patent Judges (APJs).13

These are not generalist judges. APJs are appointed by the Secretary of Commerce and are required by statute to possess deep expertise in both patent law and technology.17 Their résumés are formidable, often including experience in private practice at top IP law firms, as in-house counsel at major technology and pharmaceutical companies, or in government roles at the Department of Justice or the International Trade Commission.10 Many have advanced technical degrees and have served as USPTO patent examiners or judicial law clerks.17 This structure is designed to foster specialization, allowing judges to develop profound expertise in specific technical fields, such as biotechnology, organic chemistry, or computer architecture.9 The underlying premise of the AIA was that a tribunal of credentialed experts would be better equipped to make accurate and consistent decisions on the complex scientific questions inherent in patent validity challenges, thereby improving the overall quality and reliability of the patent system.5

The Constitutional Crucible: Forging the PTAB’s Authority

The PTAB’s creation was not without controversy. Almost immediately, its very existence was challenged on constitutional grounds. Critics argued that invalidating a patent—a form of private property—was a function reserved for Article III courts and that the PTAB’s administrative trials violated the Seventh Amendment right to a jury trial.1 This existential threat loomed over the PTAB for years, creating uncertainty for all stakeholders.

The first major test came in Oil States Energy Services, LLC v. Greene’s Energy Group. In a landmark 2018 decision, the Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of inter partes review.1 The Court reasoned that the grant of a patent is a matter of “public right,” not a private one. Because the government grants the patent franchise, Congress retains the authority to condition that grant on subsequent administrative review by the same agency.1 The

Oil States decision was the critical moment that transformed the PTAB from a controversial legislative experiment into a constitutionally validated and permanent institution.

However, the legal battles were not over. A new challenge emerged in United States v. Arthrex, Inc., this time focused on the appointment of the APJs themselves.1 The argument was that the APJs wielded such significant authority without sufficient oversight that they were “Principal Officers” under the Appointments Clause of the Constitution, meaning they had to be appointed by the President and confirmed by the Senate—a process that had not been followed.11 In 2021, the Supreme Court agreed that the APJs’ “unreviewable authority” was constitutionally problematic. But instead of dismantling the entire PTAB system, the Court performed a surgical fix: it severed the part of the patent statute that restricted the removal of APJs and held that the Director of the USPTO—a politically appointed officer—must have the discretion to review their final decisions.1

This progression from legislative creation to judicial validation has profound strategic implications. The era of questioning the PTAB’s fundamental legitimacy is over. Stakeholders can no longer hope for its dismantlement; they must build their long-term IP strategies around its permanent existence. Furthermore, the Arthrex decision, while preserving the PTAB, introduced a new and important mechanism: Director Review. This creates a new, albeit narrow, avenue of appeal and a new strategic pressure point for high-stakes cases, adding another layer of complexity to the PTAB gauntlet.

Part II: The Weapons of Choice – A Deep Dive into IPR and PGR

Navigating the PTAB requires mastering its two primary weapons of challenge: Inter Partes Review (IPR) and Post-Grant Review (PGR). While procedurally similar, they are strategically distinct tools, each with its own timing, scope, and consequences. Understanding which to use—or which you might face—is the first step in formulating any PTAB strategy.

Inter Partes Review (IPR): The Workhorse of Patent Challenges

IPR is, by a wide margin, the most common type of PTAB proceeding.16 It is the versatile workhorse available for the vast majority of a patent’s life.

The process follows a structured, trial-like timeline designed for speed and efficiency. It begins when a third party (the “petitioner”) files a detailed petition laying out its case for why specific patent claims are invalid.19 The patent owner then has an opportunity to file an optional Patent Owner Preliminary Response (POPR), arguing why the PTAB should not even institute a trial.20 Within six months of the petition filing, a panel of three APJs makes a critical decision: whether to institute the IPR. If instituted, the case proceeds through a phase of limited discovery (including depositions of expert witnesses), briefing, and an oral hearing before the panel.15 By statute, a Final Written Decision (FWD) must be issued within 12 months of institution, with a possible six-month extension for good cause.12

Two features of IPR are strategically paramount. First, the timing and grounds. An IPR petition cannot be filed until nine months after a patent is granted (or after a PGR proceeding has terminated).20 More importantly, the grounds for challenge are strictly limited to anticipation (under 35 U.S.C. §102) and obviousness (under 35 U.S.C. §103), and only on the basis of prior art consisting of patents or printed publications.4 You cannot use an IPR to challenge a patent’s eligibility, written description, or enablement. The standard for getting a trial instituted is a “reasonable likelihood” that the petitioner would prevail on at least one of the challenged claims.4

Second, the estoppel provisions are powerful and punitive. If an IPR proceeds to a Final Written Decision, the petitioner (and its real parties in interest) is barred from raising any invalidity ground in a future district court, ITC, or USPTO proceeding that it “raised or reasonably could have raised” during the IPR.12 This means a challenger gets one good shot at the PTAB; a loss can severely cripple its ability to defend itself in a subsequent infringement suit.

Post-Grant Review (PGR): The Broadsword for New Patents

If IPR is the workhorse, PGR is the broadsword—a far more powerful weapon, but one that can only be wielded within a very narrow window of opportunity. The procedure is similar to an IPR, with a petition, institution decision, and a trial phase designed to conclude within 12 to 18 months.24

The defining feature of PGR is its timing. A petition must be filed within the first nine months of a patent’s grant or reissue.24 This mechanism is only available for patents subject to the first-inventor-to-file provisions of the AIA, meaning those with an effective filing date on or after March 16, 2013.26

The strategic advantage of a PGR lies in its expanded grounds for attack. Unlike the narrowly focused IPR, a PGR petitioner can challenge a patent on nearly any statutory ground of invalidity.18 This includes not only anticipation and obviousness but also:

- Patentable Subject Matter (§101): Arguing the invention is an abstract idea or law of nature.

- Written Description (§112): Arguing the specification doesn’t show the inventor possessed the full scope of the claims.

- Enablement (§112): Arguing the specification doesn’t teach how to make and use the invention without undue experimentation.

- Indefiniteness (§112): Arguing the claims are unclear.

The only significant ground excluded is the “best mode” requirement.24 This makes PGR the only PTAB venue to challenge a patent on these fundamental patentability requirements, which are often the true vulnerabilities of broad pharmaceutical claims.

This expanded power comes with a higher bar. To institute a PGR, the petitioner must demonstrate that it is “more likely than not” that at least one of the challenged claims is unpatentable—a tougher standard than the IPR’s “reasonable likelihood” test.23 The estoppel effects are similarly broad, preventing a petitioner from later raising any ground they raised or reasonably could have raised in the PGR.25

Head-to-Head: A Strategic Comparison

The choice between IPR and PGR is not merely procedural; it dictates the entire strategic landscape of a patent challenge. The limited nine-month PGR window creates a critical “use it or lose it” dynamic for potential challengers. It forces an aggressive, front-loaded analysis of any newly issued competitor patent that could pose a threat. A robust competitive intelligence system, leveraging resources like DrugPatentWatch to monitor new patent grants, is no longer a luxury but a necessity for any company that may need to clear a path for its own products. If a challenger misses this nine-month window, the opportunity to raise a potentially fatal §112 challenge at the PTAB is lost forever.

Conversely, for a patent owner, the nine-month anniversary of a patent’s grant is a major strategic milestone. Surviving this period without a PGR challenge significantly de-risks the patent, shielding it from the PTAB’s most potent forms of attack and limiting future administrative challenges to the narrower confines of prior art-based IPRs.

The table below breaks down the key strategic differences:

| Feature | Inter Partes Review (IPR) | Post-Grant Review (PGR) |

| Filing Window | After 9 months from patent grant (or after PGR termination) 20 | Within 9 months of patent grant or reissue 24 |

| Eligible Patents | All patents, regardless of filing date 30 | Only patents filed under first-inventor-to-file (effective on/after March 16, 2013) 26 |

| Grounds for Challenge | Narrow: Anticipation (§102) and Obviousness (§103) based on patents and printed publications only 16 | Broad: Any ground of invalidity (§101, §102, §103, §112), except best mode 25 |

| Institution Standard | “Reasonable likelihood” of prevailing on at least one claim 12 | “More likely than not” that at least one claim is unpatentable 23 |

| Discovery | Limited, focused on expert testimony and cited evidence 12 | More expansive than IPR, but still more limited than district court 26 |

| Timeline | 12 months from institution to final decision (18 months with extension) 12 | 12 months from institution to final decision (18 months with extension) 24 |

| Cost (Fees + Legal) | Generally lower than PGR due to narrower scope. Fees start at $9,000 for petition.20 Total costs often in the hundreds of thousands.1 | Generally higher than IPR due to broader scope and more complex issues. Fees start at $12,000 for petition.26 |

| Estoppel Effect | Bars grounds that were “raised or reasonably could have been raised” in future USPTO/court proceedings 12 | Broader estoppel, covering any ground that “reasonably could have been raised” 25 |

| Strategic Application | The primary tool for challenging older patents based on newly discovered prior art. Often used in parallel with district court litigation. | The only PTAB tool for challenging fundamental patentability issues like written description, enablement, and subject matter eligibility. A “first strike” weapon against new, threatening patents. |

Part III: The Scorecard – What the Data Really Says About Pharma Patents at the PTAB

For any strategist, data is the ultimate currency. Anecdotes and narratives are compelling, but numbers tell the real story. To truly assess how safe a drug patent is, we must move beyond the “death squad” moniker and dissect the statistical record. When we do, a clear picture emerges: pharmaceutical and biologic patents behave very differently at the PTAB than their counterparts in the tech world. The threat is real, but it is specific, targeted, and, for the well-prepared, quantifiable.

Debunking the Myth: Overall Trends vs. Pharma-Specific Realities

The narrative of the PTAB as a patent graveyard is fueled by some eye-popping top-line statistics. Across all technologies, the rate at which the Board institutes trials has been climbing, rising from 56% in fiscal year 2020 to 68% in 2024.33 Once a trial is instituted, the odds for the patent owner look even grimmer. The rate at which

all challenged claims are found unpatentable in a final written decision has also increased, from a low of 55% in 2019 to around 70% in recent years.3 On a per-claim basis, the numbers are even starker, with nearly 80% of instituted claims being invalidated.33

These figures, however, are heavily skewed by the vast number of petitions filed against patents in the electrical and computer technology sectors, which accounted for 69% of all petitions in FY2024.36 The pharmaceutical and biotech sectors are a world apart. Challenges to patents listed in the FDA’s Orange Book and patents covering biologics represent a tiny fraction of the PTAB’s total docket—around 4% and 2%, respectively, in the cumulative data from 2012 to 2023.37

This is the first critical divergence. The second, and more profound, is the ultimate outcome. A pivotal analysis by Ropes & Gray directly compared invalidation rates for Orange Book-listed patents in both the PTAB and district courts. The findings were stunning and directly contradicted the “death squad” narrative for this specific sector.

“Traditional thinking is that patents are far more likely to be killed at the PTAB than in district court. But the analysis found 23 percent of patentability decisions from the PTAB involving Orange Book patents have resulted in all the challenged claims being found invalid. In district court, all challenged claims were invalidated 24 percent of the time.” 39

This remarkable parity suggests that for Orange Book patents, the PTAB is not an outlier but rather a different, faster, and cheaper path to a similar destination. The perceived pro-challenger bias, at least in this high-stakes sector, appears to be more myth than reality.

Institution Rates: Getting Past the Gatekeeper

The first hurdle in any PTAB challenge is the institution decision. Here again, the data reveals a distinct pattern for pharmaceutical patents. While overall institution rates have trended upward, the rate for Orange Book patents has historically been lower and more stable, hovering around 62-64% cumulatively.37 Biologic patents have faced an even tougher path to institution, with a cumulative rate closer to 55%.40

However, a more recent trend adds a layer of complexity. While the volume of bio/pharma petitions remains low (just 6% of the total in FY2024), the petitions that are filed are being instituted at a surprisingly high rate—73% for the bio/pharma sector in FY2024.41 This seemingly contradictory data points to a “quality over quantity” phenomenon. The economics of the Hatch-Waxman Act and the high cost of a PTAB proceeding mean that challengers—typically well-funded generic and biosimilar companies—are not filing frivolous or speculative petitions.5 They are launching highly targeted, well-researched assaults against what their analysis has identified as the weakest and most commercially significant patents in a brand’s portfolio. Therefore, while fewer in number, the petitions that a pharmaceutical patent owner receives are likely to be formidable and have a high probability of meeting the institution threshold. For a patent owner, any PTAB petition must be treated as a serious, well-vetted threat, not a mere nuisance filing.

Invalidation Rates: Surviving the Trial

Once a trial is instituted, the fate of a pharmaceutical patent depends heavily on what, precisely, it claims. The overall statistics can be misleading. For instance, post-institution, biologic patents have fared poorly, with one study finding that 70% of Final Written Decisions resulted in all challenged claims being found unpatentable, compared to a 45% rate for Orange Book patents.40

The most granular and strategically valuable data comes from breaking down outcomes by patent type. The Ropes & Gray analysis provides a clear hierarchy of vulnerability 39:

- Compound Patents: These are the crown jewels, covering the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) itself. They are exceptionally resilient. The study found not a single instance of a compound patent for an Orange Book-listed drug being completely invalidated at the PTAB.

- Formulation Patents: These patents, which cover how a drug is prepared and delivered, are more vulnerable. The PTAB fully invalidated all challenged claims in 15% of these cases.

- Method-of-Use Patents: These are the most susceptible to challenge. Covering the use of a drug to treat a specific condition, these patents saw all challenged claims invalidated in 27% of PTAB final decisions.

This data provides a clear risk profile. A patent on a novel molecular entity is relatively safe. The true battleground is the “patent thicket”—the web of secondary patents covering formulations and new uses that are critical for extending a drug’s lifecycle. It is here that challengers focus their attacks, and where patent owners face the greatest risk.

Finally, it’s crucial to remember that a large percentage of instituted cases never reach a final decision at all. They are terminated through settlement.34 The PTAB process often serves as a powerful catalyst for negotiation, forcing both sides to realistically assess the strengths and weaknesses of the patent and leading to a business resolution rather than a legal one.

The following table synthesizes the available data to provide a snapshot of PTAB outcomes, highlighting the key differences between the pharmaceutical sector and the broader patent landscape.

| Metric | Orange Book Patents (Cumulative) | Biologic Patents (Cumulative) | All Technologies (FY24) |

| Petitions as % of Total | ~4% 37 | ~2% 38 | 100% |

| Institution Rate (by Petition) | 62% 37 | 55% 40 | 68% 33 |

| % of FWDs: All Claims Invalidated | 45% 40 | 70% 40 | ~68% 3 |

| % of FWDs: All Claims Survived | 50% 40 | 21% 40 | ~16% 41 |

| % of Cases Settled | Lower than average (~17-28%) 40 | Lower than average (~28-29%) 40 | ~32% 41 |

Note: Data is compiled from various USPTO reports and analyses covering different time periods. Cumulative data generally spans from 2012 to 2021/2023, while “All Technologies” data reflects the most recent FY2024 report for current trends. The settlement rate is for all terminated proceedings, not just post-institution.

Part IV: War Stories – Landmark Case Studies and the Lessons They Teach

Data provides the map, but case studies provide the landmarks. To truly understand the strategic terrain of the PTAB, we must examine the battles that have been fought—the victories, the defeats, and the critical missteps that decided them. These war stories offer priceless, hard-won lessons in both offense and defense.

The Siege of Humira: Anatomy of a “Patent Thicket” Defense

Perhaps no case better illustrates the strategic complexity of modern pharmaceutical patent defense than the multi-front war over AbbVie’s blockbuster drug, Humira (adalimumab). Facing the 2016 expiration of its core compound patent, AbbVie executed a masterful—and controversial—strategy: it constructed a dense “patent thicket” of more than 100 secondary patents covering everything from formulations and manufacturing methods to specific treatment regimens.7 This IP fortress was designed to make a biosimilar challenge not just a single legal battle, but a protracted and prohibitively expensive war of attrition. The PTAB became a key battleground in this war.

- Coherus’s Successful Obviousness Attack: Biosimilar developer Coherus Biosciences launched a targeted strike against several of AbbVie’s method-of-use patents, including the ‘135, ‘680, and ‘987 patents, which covered a 40mg biweekly subcutaneous dosing regimen for rheumatoid arthritis.45 Coherus argued that this regimen would have been obvious to a skilled artisan by combining the teachings of two prior art references:

Kempeni, which disclosed biweekly intravenous administration of Humira, and van de Putte, which disclosed subcutaneous administration.46 The PTAB agreed, finding that a skilled person would have been motivated to combine the references to achieve a more convenient and cost-effective subcutaneous regimen with a reasonable expectation of success.46 - AbbVie’s Critical Misstep: In its defense, AbbVie argued for the non-obviousness of the dosing regimen based on the tremendous commercial success of Humira. This is a standard and often powerful argument. However, the PTAB rejected it for a devastating reason. Coherus pointed out that in other IPR proceedings defending its formulation patents, AbbVie had argued that Humira’s commercial success was driven by its unique, stable, self-administrable liquid formulation—not the dosing regimen.46 This fatal inconsistency shredded AbbVie’s credibility. The PTAB concluded it was unclear whether the drug’s success was due to the claimed dosing regimen or the formulation, and thus the evidence of commercial success was not persuasive.46 The lesson is brutal and clear: a portfolio defense requires a coherent, consistent narrative. Arguments made to save one patent can be used against you to kill another.

- Sandoz’s Unsuccessful Attack: Not all challengers were successful. When Sandoz challenged other Humira patents (the ‘216 and ‘100 patents), the PTAB denied institution.47 AbbVie’s victory here was not based on the substantive merits of obviousness but on sharp procedural and evidentiary defense. Sandoz’s case relied heavily on the Humira package insert as a piece of prior art. AbbVie successfully argued that Sandoz had failed to provide sufficient evidence that the package insert was actually publicly accessible before the patent’s priority date.48 The Board found that language in an FDA approval letter stating Humira “will be marketed” suggested the product was not yet available to the public at that time.48 Without this key piece of prior art, Sandoz’s obviousness argument collapsed before the trial even began.

- The Endgame: The Thicket Wins the War: Despite losing some individual PTAB battles, AbbVie’s overall strategy was a resounding success. The sheer number of patents, the cost of challenging each one (an IPR can cost upwards of $700,000), and the uncertainty of success on every front created insurmountable economic pressure on biosimilar developers.43 Ultimately, numerous challengers, including Amgen, Sandoz, and Coherus, settled with AbbVie, agreeing to delay their U.S. market entry until 2023—years after the core patent expired.44 The Humira saga demonstrates that PTAB challenges are often battles within a larger war. The goal of a patent thicket is not necessarily to win every single engagement, but to make the overall war so costly and time-consuming that a negotiated peace (settlement) becomes the challenger’s most rational economic choice.

The Obviousness Battleground: The Evolving “Lead Compound” Analysis

For patents claiming new chemical compounds, the primary line of defense against an obviousness challenge has long been the “lead compound” analysis.50 This framework requires a challenger to do more than just point to similar compounds in the prior art. They must convincingly explain why a person of ordinary skill in the art (POSA) would have selected a

specific prior art compound as a “lead” for further development and then been motivated to make the specific modifications necessary to arrive at the claimed invention, all with a “reasonable expectation of success”.50

For years, the PTAB has applied this framework rigorously, often to the benefit of patent owners. In several cases, the Board has denied institution because a petitioner simply pointed to a large list of disclosed compounds in a reference without explaining why a POSA would have chosen one particular compound out of hundreds to start with.51 A recent, high-profile example is

Mylan Pharms., Inc. v. Novo Nordisk A/S, an IPR challenge against patents covering semaglutide, the active ingredient in Ozempic® and Wegovy®.50 While the PTAB agreed with Mylan on the selection of a lead compound (liraglutide), it ultimately denied institution, finding that Mylan had failed to adequately explain why a POSA would have been motivated to make three separate and distinct modifications to that lead compound with a reasonable expectation of success.50

However, a dangerous new trend is emerging. In some recent cases, the PTAB has shown a willingness to deviate from a strict lead compound analysis, particularly when the starting material is a natural or obvious choice, like a fundamental nucleoside for building RNA oligonucleotides.50 This flexibility suggests that the once-formidable shield of the lead compound analysis may be developing cracks, exposing a new vulnerability for chemical compound claims that patent owners and challengers alike must monitor closely.

The Written Description Tightrope: Functional Claiming Under Fire

One of the most potent grounds for invalidating a broad pharmaceutical patent is the written description requirement of 35 U.S.C. §112. The statute requires that the patent specification clearly demonstrate that the inventor was in “possession” of the full scope of the claimed invention at the time of filing.52 For claims that define a component by its function (e.g., “an antibody that binds to antigen X”) rather than its structure, this requirement is particularly difficult to meet. The courts and the PTAB now demand that the specification provide either a representative number of species that perform the function or identify common structural features that allow a POSA to recognize the members of the claimed genus.52

The seminal case in this area is Juno Therapeutics, Inc. v. Kite Pharma, Inc..54 Juno’s foundational patent on CAR-T cell therapy claimed a chimeric antigen receptor comprising three parts, one of which was a “binding element” defined functionally by what it binds to (e.g., CD19). The Federal Circuit invalidated the patent for lack of written description. It found that the specification disclosed only two examples of such binding elements and provided no structural details or common features that would allow a POSA to identify other binding elements that would work.55 Juno argued that the true invention was the CAR “backbone,” not the binding element, but the court flatly rejected this, stating that

all claimed elements must be adequately described.55

This stringent approach was reinforced by the Supreme Court’s decision in Amgen v. Sanofi, which focused on the related requirement of enablement.58 The Court’s holding was simple and powerful: “The more one claims, the more one must enable”.58 The PTAB is now aggressively applying the logic of both

Juno and Amgen in PGR proceedings to invalidate broad, functionally-defined genus claims in the life sciences for failing both the written description and enablement requirements.58 For patent prosecutors, the lesson is clear: over-relying on functional claiming without providing substantial structural support and a wealth of working examples is a recipe for a §112 disaster.

Part V: The Art of War – A Playbook for PTAB Strategy

Understanding the PTAB’s history, mechanics, and key precedents is foundational. Now, we translate that knowledge into action. This is the art of war—a strategic playbook for both the patent owner defending their fortress and the challenger seeking to breach its walls.

For the Patent Owner: Fortifying Your IP Fortress

A successful defense against a PTAB challenge does not begin when the petition is served. It begins years earlier, during patent prosecution, and continues through a vigilant, multi-layered strategy.

Proactive Defense: Building a PTAB-Resistant Portfolio

The most effective defense is a proactive one. Building a portfolio that anticipates and withstands future challenges is the ultimate goal.

- Prosecution as Pre-Litigation: Every action taken before the USPTO during prosecution is building the record for a future litigation or PTAB trial. The best defense starts here. Conduct exhaustive, professional prior art searches before filing to understand the landscape and draft claims that are defensible from the outset.59 Meticulously document R&D to support claims of unexpected results or to overcome obviousness rejections.7 Maintain a clean and consistent prosecution history (the “file wrapper”). Every argument made to the examiner, every amendment, every declaration can and will be used by a future challenger to find weaknesses or inconsistencies.7

- Weaving a Strategic Thicket: As the Humira case demonstrated, a single patent, no matter how strong, is a single point of failure. A strategic “patent thicket” is a multi-layered defense designed to create numerous, independent, and overlapping hurdles for any challenger.7 This goes far beyond the core composition of matter patent on the API. A robust portfolio should systematically protect:

- Formulations: New delivery systems, excipient combinations, or extended-release versions.7

- Methods of Use: Novel therapeutic applications for the drug, even for different diseases.7

- Manufacturing Processes: Unique and proprietary methods of synthesis and production.7

- Polymorphs and Enantiomers: Different crystalline structures or stereoisomers of the API that may offer advantages.7

Each additional patent is another potential lawsuit, another PTAB petition, and another significant cost that a challenger must bear, transforming legal protection into a powerful economic deterrent.7 - Drafting Claims with §112 in Mind: The lessons from Juno and Amgen must be taken to heart. Over-reliance on broad, functional claiming is a significant vulnerability, especially for patents eligible for PGR. Draft a spectrum of claims, from broad independent claims to narrower dependent claims.59 For any claimed genus, the specification must provide substantial support, including numerous working examples, data demonstrating efficacy, and descriptions of common structural features where possible. This builds a record to show “possession” of the invention and enables a skilled person to practice it without undue experimentation, directly inoculating the patent against §112 attacks.

Reactive Defense: Winning the PTAB Fight

When a petition lands, the clock starts ticking. A swift, decisive, and strategically sound reactive defense is critical.

- The Patent Owner Preliminary Response (POPR): This optional filing is arguably the most important document a patent owner will file in a PTAB proceeding. It is the one and only chance to convince the Board not to institute the trial at all. A successful POPR saves immense time and money. The strategy should be surgical, focusing on the petitioner’s most glaring weaknesses.21 This could mean attacking the motivation to combine references, challenging the assertion of a “reasonable expectation of success,” or, as AbbVie successfully did against Sandoz, proving that a key reference does not even qualify as prior art.48 A strong POPR can end the fight before it truly begins.

- Leveraging Procedural Arguments: Don’t neglect the procedural aspects of the petition. Scrutinize it for compliance with all PTAB rules. Are all real parties in interest correctly identified? Was the petition filed within the one-year statutory bar if there was prior litigation? As established in Thryv, Inc. v. Click-to-Call Technologies, the Board’s decision on the time bar is non-appealable, making it a critical, front-end issue to raise in the POPR.62

- Mastering Secondary Considerations: If the challenge is based on obviousness, building a powerful case around secondary considerations is essential. These objective indicia of non-obviousness can be extremely persuasive to the Board. The key is to present compelling evidence of:

- Commercial Success: Demonstrate strong sales and market share, but crucially, provide a clear nexus linking that success directly to the features of the claimed invention. This was AbbVie’s fatal error in the Coherus IPR.15

- Long-Felt, Unmet Need: Show that the invention solved a problem that had vexed the industry for years.

- Unexpected Results: Provide data showing the invention achieved results that were surprising and superior to what the prior art would have predicted.

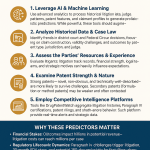

For the Challenger: Finding and Exploiting the Weakest Link

For generic and biosimilar companies, the PTAB is a powerful tool for clearing the path to market entry. A successful challenge, however, requires a disciplined and economically rational approach.

The Economics of the Challenge

- Strategic Target Selection: Challengers do not attack patent thickets indiscriminately. The process begins with sophisticated competitive intelligence. Using comprehensive databases and analytics tools, such as those provided by DrugPatentWatch, challengers meticulously dissect a competitor’s portfolio to identify patents that are both commercially critical (i.e., blocking market entry) and legally vulnerable.7 The data is clear: market value is the single most important predictor of a patent challenge. Drugs with higher sales are far more likely to be targeted.63 The most vulnerable patents are typically not the core compound patents, but the secondary method-of-use and formulation patents that form the outer layers of the thicket.39

- The High Probability of a Favorable Outcome: While winning a Final Written Decision is not guaranteed, the overall economics favor the challenger. When factoring in the high number of cases that end in favorable settlements for the generic company, the overall “success rate” for Paragraph IV challengers climbs to a staggering 76%.65 This makes filing a well-researched PTAB petition an economically rational, high-upside strategic move.

The Rise of the Non-Traditional Challenger: The Kyle Bass Saga

The AIA’s provision that any person who is not the patent owner can file an IPR opened the door to a new breed of challenger: the activist investor. The most famous (or infamous) example is hedge fund manager Kyle Bass and his Coalition for Affordable Drugs (CFAD).66

- The “Short-and-Distort” Strategy: Bass’s strategy was novel and controversial. He would publicly short the stock of a pharmaceutical company, betting its price would fall. Then, he would file an IPR petition against one of the company’s key drug patents, publicizing the challenge to create uncertainty and downward pressure on the stock price, thereby profiting from his short position.2 His stated motivation was altruistic—to invalidate “BS patents” and lower drug prices—but the financial motive was undeniable.67

- The PTAB’s Response and the Outcome: The pharmaceutical industry was outraged, filing motions to have Bass sanctioned for abusing the IPR process. The PTAB, however, refused.67 In a key decision, the Board stated that “[p]rofit is at the heart of nearly every patent and nearly every inter partes review” and that the statute places no restrictions on a petitioner’s motives.68 Despite this procedural victory, Bass’s campaign yielded mixed results. CFAD’s petitions had a higher-than-average institution rate and invalidation rate for the cases that reached a final decision.69 However, the strategy did not appear to be the financial windfall many feared. The market quickly adapted, and later IPR filings did not produce the same dramatic stock drops as the initial ones.70 The campaign did not spawn a wave of copycat challengers, and it ultimately faded. The saga serves as a fascinating case study on the outer limits of PTAB strategy and a cautionary tale about the complexities of leveraging the patent system for purely financial plays.

Part VI: The Shifting Landscape – The Future of PTAB and Its Impact on Pharma

The PTAB is not a static institution. It is a dynamic legal battleground constantly being reshaped by decisions from the Supreme Court, new legislation from Congress, and evolving internal procedures at the USPTO. Staying ahead of these shifts is critical for any long-term IP strategy.

The Supreme Court’s Shadow: Reshaping PTAB Procedure

In recent years, the Supreme Court has taken a keen interest in the PTAB, issuing a series of decisions that have profoundly altered its day-to-day practice.

- SAS Institute Inc. v. Iancu (2018): This decision was a game-changer for the institution phase. Prior to SAS, the PTAB frequently practiced “partial institution,” where it would agree to review some of the claims challenged in a petition but not others.72 The Supreme Court put an end to this practice, holding that the statute requires an “all or nothing” approach. If the Board institutes an IPR, it

must address the patentability of every single claim challenged in the petition.4 This forced petitioners to be more disciplined, as they could no longer pad a strong petition with weaker challenges. It also provided more certainty for both parties about the scope of the trial from the outset. - Thryv, Inc. v. Click-to-Call Technologies, LP (2020): This decision had an even more dramatic impact on the pre-institution phase. The AIA includes a one-year time bar (35 U.S.C. §315(b)), which states that an IPR petition cannot be instituted if it is filed more than one year after the petitioner was served with a complaint for patent infringement.73 The question in

Thryv was whether the PTAB’s decision that a petition was not time-barred could be appealed to the Federal Circuit. The Supreme Court’s answer was a resounding no. It held that the statute’s provision making the institution decision “final and nonappealable” applies to all aspects of that decision, including the threshold determination on timeliness.62

The strategic implications of these decisions are immense. Together, they have transformed the pre-institution phase into a high-stakes, all-or-nothing event with extremely limited judicial recourse. Thryv, in particular, means that a patent owner’s only opportunity to defeat a petition on timeliness is in their Patent Owner Preliminary Response. If the PTAB disagrees and institutes the trial, that threshold decision cannot be challenged on appeal. This dramatically raises the stakes of the POPR and places immense pressure on patent owners to make their case perfectly the first time, while granting the PTAB significant, unreviewable power.

The Winds of Change from Congress: The PREVAIL Act

The debate over the PTAB’s role and power has also reached Capitol Hill. A significant, bipartisan legislative effort known as the PREVAIL Act seeks to enact the most substantial pro-patent-owner reforms since the AIA’s passage.78 If passed, it would fundamentally alter the risk calculus for both challengers and patentees. Key provisions include 78:

- Harmonizing Standards with District Court: The Act would raise the burden of proof at the PTAB from “preponderance of the evidence” to the higher “clear and convincing evidence” standard used in federal courts. It would also codify the use of the same claim construction standard (“plain and ordinary meaning”).78

- Implementing a Standing Requirement: The Act would require an IPR petitioner to have been sued or threatened with a lawsuit, effectively ending challenges from entities like activist investors or unrelated third parties.79

- Forcing a Choice of Forum: A party would have to choose between challenging a patent’s validity at the PTAB or in district court, but not both. This would eliminate the “second bite at the apple” that challengers currently enjoy.78

- Strengthening Estoppel: The Act would apply estoppel at the time a petition is filed, rather than after a final decision, to prevent serial petitions and harassing challenges against the same patent.78

Proponents argue these reforms are necessary to restore balance to the patent system, protect innovators from costly and duplicative litigation, and curb the invalidation of legitimate patents.78 Opponents, however, raise concerns that the Act will make it too difficult and expensive to challenge weak patents, particularly in the pharmaceutical space, which could stifle generic and biosimilar competition and contribute to higher drug prices.79 The fate of the PREVAIL Act remains uncertain, but its progress through Congress signals a powerful push to recalibrate the PTAB’s role in the patent ecosystem.

The Director’s Discretion: A New Wildcard

A final, evolving factor shaping the PTAB landscape is the increasing use of Director discretion to deny institution of otherwise meritorious petitions. This practice gained prominence under the Fintiv framework, where the Board considers factors related to a parallel district court litigation—such as the scheduled trial date and the degree of overlap in issues—to decide whether instituting an IPR would be an inefficient use of resources.3

More recently, a new and potentially powerful concept has emerged: denying institution based on the patent owner’s “settled expectations”.83 The idea is that if a patent has been issued for many years without being challenged, the owner has a reasonable, settled expectation in its validity. A late-in-life IPR petition can disrupt these expectations. The USPTO Director has begun to use this rationale to deny petitions against older patents, effectively creating a de facto statute of limitations for challenges that extends beyond the statutory one-year bar.84 This is a developing area of PTAB jurisprudence, but it introduces a new layer of uncertainty for challengers and a potent new defensive argument for owners of long-standing patents.

Conclusion & Key Takeaways

The journey through the PTAB gauntlet is complex, fraught with risk, and governed by a constantly evolving set of rules. The “patent death squad” narrative, while a powerful and enduring soundbite, fails to capture the nuanced reality of this critical institution, especially within the pharmaceutical industry. The data and case law paint a far more intricate picture—one where strategy, preparation, and a deep understanding of the specific vulnerabilities of different patent types are paramount.

The PTAB is not an indiscriminate killer of pharmaceutical patents. It is a specialized forum where weak secondary patents—particularly those covering methods of use and formulations—are efficiently tested and often invalidated. The crown jewels of a pharmaceutical portfolio, the core compound patents, remain remarkably resilient. The true danger lies not in a single, fatal blow, but in a war of attrition against a well-constructed patent thicket, where the PTAB serves as one of several key battlegrounds.

Navigating this landscape requires a holistic approach that seamlessly integrates legal, R&D, and business strategy. The best defense is forged years before a challenge ever arises, through meticulous patent prosecution, the strategic weaving of a multi-layered patent portfolio, and the careful drafting of claims that can withstand the intense scrutiny of §112. When a challenge does arrive, victory often hinges on a surgically precise preliminary response, a mastery of procedural tactics, and a consistent, credible narrative.

The PTAB is here to stay. Its constitutional legitimacy is settled, and its role as a faster, cheaper alternative to district court is firmly entrenched. However, its procedures and power are in a constant state of flux, shaped by the Supreme Court, Congress, and the USPTO Director. For the pharmaceutical and biotech leaders tasked with protecting their most valuable assets, success demands more than just legal expertise. It demands vigilance, strategic foresight, and the ability to see the PTAB not as a threat to be feared, but as a gauntlet to be mastered.

Key Takeaways

- Pharma Patents Are Different: The “patent death squad” narrative does not hold up for pharmaceutical patents. Invalidation rates for Orange Book-listed patents at the PTAB are statistically similar to those in district court. The risk is not uniform; it is highly concentrated in secondary patents (formulations, methods of use), while core compound patents remain extremely robust.

- Proactive Defense is Paramount: The most effective way to survive a PTAB challenge is to build a PTAB-resistant patent portfolio from the start. This involves exhaustive prior art searching, strategic claim drafting to avoid §112 vulnerabilities, and building a multi-layered “patent thicket” to raise the cost and complexity for any potential challenger.

- The Preliminary Response is Your Best Weapon: The Patent Owner Preliminary Response (POPR) is the single most critical defensive filing. It is the only opportunity to prevent trial institution. A successful POPR focuses on a petitioner’s weakest points, including procedural flaws like timeliness and the public availability of prior art.

- Strategy is a Narrative: A successful portfolio defense requires a consistent narrative. As seen in the Humira case, arguments made to defend one patent (e.g., success is due to the formulation) can be used by a challenger to invalidate another (e.g., a dosing regimen patent).

- The Landscape is Constantly Shifting: The rules of engagement at the PTAB are not static. Landmark Supreme Court decisions (SAS, Thryv), potential legislation (the PREVAIL Act), and evolving USPTO policies (Director Discretion, “settled expectations”) continually reshape the strategic calculus. Constant monitoring is essential.

FAQ Section

1. What is the single most important action a patent owner can take to defend against a PTAB petition?

The single most important action is to file a meticulously crafted and persuasive Patent Owner Preliminary Response (POPR). This is the patent owner’s only opportunity to prevent the PTAB from instituting a trial. A successful POPR can terminate the proceeding before the costly and time-consuming trial phase even begins. The most effective POPRs often focus on fatal procedural or evidentiary flaws in the petition—such as demonstrating that a key prior art reference was not publicly available before the priority date (as in Sandoz v. AbbVie) or that the petition is time-barred—rather than trying to win the entire substantive argument on the merits at this early stage.

2. For a generic/biosimilar company, what characteristics make a patent an ideal target for an IPR or PGR?

An ideal target patent has a combination of high commercial value and identifiable legal vulnerability. Commercially, the patent must be a significant barrier to market entry for a high-revenue drug. Legally, the most vulnerable patents are typically not the core compound patents but secondary patents, especially method-of-use patents, which have the highest invalidation rates at the PTAB. An ideal target for a PGR would be a newly issued patent (within the 9-month window) with broad, functionally-defined claims that appear vulnerable to a written description or enablement challenge under §112, grounds not available in an IPR.

3. How has the Supreme Court’s SAS Institute decision changed how petitioners should draft their IPR petitions?

The SAS Institute decision, which eliminated “partial institution,” forces petitioners to be more disciplined and strategic in drafting their petitions. Before SAS, petitioners might include a mix of very strong and marginally weaker invalidity grounds, hoping the Board would institute on the strong ones. Now, because the Board must institute on all challenged claims or none, including weaker arguments can dilute the overall strength of the petition and risk a complete denial of institution. The best practice now is to focus the petition exclusively on the strongest, most compelling grounds for invalidity to maximize the chances of getting past the institution gatekeeper.

4. If the PREVAIL Act passes, how will it change the strategic decision of whether to challenge a patent in the PTAB versus district court?

The PREVAIL Act would fundamentally change this decision by forcing a challenger to choose a single forum. Currently, many challengers use the PTAB and district court in parallel, leveraging the PTAB’s speed and lower burden of proof. If the Act passes, a challenger would have to make a critical strategic choice. For a clear-cut case of invalidity based on a “smoking gun” prior art document, the PTAB might still be attractive due to its speed and technical expertise. However, for more complex cases, or cases where the challenger also has strong non-infringement arguments (which cannot be heard at the PTAB), they might opt for district court, despite the higher cost and “clear and convincing” evidence standard, to resolve all issues in a single venue. The Act would make the choice of forum a binding, high-stakes strategic decision at the very outset of a dispute.

5. Given the high institution rate for filed bio/pharma petitions, is it ever a good strategy for a patent owner to not file a Preliminary Response?

While technically optional, forgoing a POPR in a high-stakes pharmaceutical case is an extremely risky and rarely advisable strategy. The high institution rate for filed bio/pharma petitions (73% in FY24) indicates that these petitions are well-researched and taken very seriously by the Board. The POPR is the only chance to prevent institution. By not filing one, the patent owner concedes the petitioner’s narrative and forces the Board to make its decision based solely on the challenger’s arguments. The only conceivable scenario for not filing might be a resource-constrained situation where the patent owner believes its case is overwhelmingly strong on the merits and would rather save its arguments and resources for the full trial. However, this is a significant gamble that cedes a critical opportunity to terminate the proceeding early.

Works cited

- The Patent Trial and Appeal Board and Inter Partes Review – Congress.gov, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/R48016

- What They Are Saying: Close Patent Loopholes That Threaten Innovation for Patients, accessed August 16, 2025, https://phrma.org/blog/what-they-are-saying-close-patent-loopholes-that-threaten-innovation-for-patients

- Patent Invalidation Trends: PTAB Impact & Global Developments – TT Consultants, accessed August 16, 2025, https://ttconsultants.com/the-global-shift-in-patent-invalidation-ptab-upc-emerging-trends/

- Inter partes review – Wikipedia, accessed August 16, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Inter_partes_review

- POST-GRANT ADJUDICATION OF DRUG PATENTS: AGENCY AND/OR COURT? – Berkeley Technology Law Journal, accessed August 16, 2025, https://btlj.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/0003-37-1-Rai.pdf

- The Role of Patents and Regulatory Exclusivities in Drug Pricing …, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/R46679

- Patent Defense Isn’t a Legal Problem. It’s a Strategy Problem. Patent Defense Tactics That Every Pharma Company Needs – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/patent-defense-isnt-a-legal-problem-its-a-strategy-problem-patent-defense-tactics-that-every-pharma-company-needs/

- The Case for the Patent Trial and Appeal Board That Congress Envisioned, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.americanbar.org/groups/intellectual_property_law/resources/landslide/2025-spring/case-patent-trial-appeal-board-congress-envisioned/

- Understanding the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) – A Comprehensive Overview, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/understanding-the-patent-trial-and-appeal-board-ptab-a-comprehensive-overview/

- About PTAB | USPTO, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.uspto.gov/patents/ptab/about-ptab

- Patent Trial and Appeal Board – Wikipedia, accessed August 16, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Patent_Trial_and_Appeal_Board

- Inter Partes Review (IPR) – Publications – Morgan Lewis, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.morganlewis.com/pubs/2021/04/inter-partes-review-ipr-2020

- Overview | Post Grant Proceedings | Armstrong Teasdale LLP, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.armstrongteasdale.com/post-grant-proceedings/

- The PTAB Case – DebateUS, accessed August 16, 2025, https://debateus.org/the-ptab-case/

- Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) | BakerHostetler, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.bakerlaw.com/services/intellectual-property/patent-trial-and-appeal-board-ptab/

- Post-Grant Proceedings | Perkins Coie, accessed August 16, 2025, https://perkinscoie.com/services/post-grant-proceedings

- Patent Trial and Appeal Board – USPTO, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.uspto.gov/about-us/organizational-offices/patent-trial-and-appeal-board

- Challenging Patents through Post-Grant Proceedings – Fish & Richardson, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.fr.com/insights/ip-law-essentials/challenging-patents-through-post-grant-proceedings-what-are-your-options/

- What is an inter partes review (IPR)? | Winston & Strawn Law Glossary, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.winston.com/en/legal-glossary/inter-partes-review

- Inter Partes Review (IPR) – Maier & Maier – Patent Attorneys, accessed August 16, 2025, https://maierandmaier.com/practice-areas/post-grant-practice/inter-partes-review-ipr/

- Patent Basics: Practice Tips for Achieving Success in Inter Partes Reviews, accessed August 16, 2025, https://ipwatchdog.com/2023/10/25/patent-basics-practice-tips-achieving-success-inter-partes-reviews/id=168632/

- To Do List: Filing an IPR | Finnegan | Leading IP+ Law Firm, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.finnegan.com/en/at-the-ptab-blog/to-do-list-filing-an-ipr.html

- Inter Partes Disputes – USPTO, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.uspto.gov/patents/laws/america-invents-act-aia/inter-partes-disputes

- What is Post-Grant Review? | Winston & Strawn Legal Glossary …, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.winston.com/en/legal-glossary/post-grant-review

- To Do List: Filing a PGR | Finnegan | Leading IP+ Law Firm, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.finnegan.com/en/at-the-ptab-blog/to-do-list-filing-a-pgr-2.html

- Post-Grant Review – Maier & Maier – Patent Attorneys, accessed August 16, 2025, https://maierandmaier.com/practice-areas/post-grant-practice/post-grant-review/

- Five Things You Should Know About Post-Grant Review, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.hunton.com/media/legal/2030_Five_Things_You_Should_Know_About_PostGrant_Review.pdf

- BSKB Post Grant Proceedings, accessed August 16, 2025, https://postgrantproceedings.com/patent_modification/post-grant-review/

- Post-Grant Review | Post-Grant Patent Proceedings – Marshall, Gerstein & Borun LLP, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.marshallip.com/post-grant-patent-proceedings/post-grant-review/

- Major Differences between IPR, PGR, and CBM – USPTO, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.uspto.gov/sites/default/files/ip/boards/bpai/aia_trial_comparison_chart.pptx

- What is Inter Partes Review, Post Grant Review and Covered Business Method Review?, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.greyb.com/blog/pgr-ipr-cbm/

- Strategies for Patent Invalidation through PGR and IPR – TT Consultants, accessed August 16, 2025, https://ttconsultants.com/post-grant-review-pgr-and-inter-partes-review-ipr-strategies-for-patent-invalidation/

- The PTAB’s 70% All-Claims Invalidation Rate Continues to Be a Source of Concern, accessed August 16, 2025, https://ipwatchdog.com/2025/01/12/ptab-70-claims-invalidation-rate-continues-source-concern/id=184956/

- PTAB Trial Statistics – FY20 End of Year Outcome Roundup IPR, PGR, CBM – USPTO, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.uspto.gov/sites/default/files/documents/ptab_aia_fy2020_roundup.pdf

- Recent Statistics Show PTAB Invalidation Rates Continue to Climb – IPWatchdog.com, accessed August 16, 2025, https://ipwatchdog.com/2024/06/25/recent-statistics-show-ptab-invalidation-rates-continue-climb/id=178226/

- PTAB AIA FY2024 Roundup: Key Insights and Statistics, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.ptablitigationblog.com/ptab-aia-fy2024-roundup-key-insights-and-statistics/

- Hatch-Waxman 2023 Year in Review – Fish & Richardson, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.fr.com/insights/thought-leadership/articles/hatch-waxman-2023-year-in-review-2/

- PTAB AIA FY 2019 Roundup appendix – USPTO, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.uspto.gov/sites/default/files/documents/ptab_aia_fy2019_roundup_appendix.pdf

- Drug Patent Challenges At PTAB By The Numbers – Mayer Brown, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.mayerbrown.com/-/media/files/news/2018/06/drug-patent-challenges-at-ptab-by-the-numbers/files/drug-patent-challenges-at-ptab-by-the-numbers/fileattachment/drug-patent-challenges-at-ptab-by-the-numbers.pdf

- PTAB statistics show interesting trends for Orange Book and biologic patents in AIA proceedings | Mintz, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.mintz.com/insights-center/viewpoints/2231/2021-08-24-ptab-statistics-show-interesting-trends-orange-book-and

- Trial Statistics Trends at the PTAB: 2024 Edition, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.ptablaw.com/2025/01/06/trial-statistics-trends-at-the-ptab-2024-edition/

- DRUG PATENTS, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.venable.com/-/media/files/publications/2017/06/initial-data-shows-that-ptab-is-not-a-death-squad.pdf?rev=0ba5c7a1b51245308ebc2f47b97e2cbf&hash=84994AD0AEEF6778D76E86D146203111

- The Patent Portfolio as a Strategic Asset: A Comprehensive Guide to …, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/leveraging-a-drug-patent-portfolio-for-success/

- AbbVie’s Enforcement of its ‘Patent Thicket’ For Humira Under the BPCIA Does Not Provide Cognizable Basis for an Antitrust Violation | Mintz, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.mintz.com/insights-center/viewpoints/2231/2020-06-18-abbvies-enforcement-its-patent-thicket-humira-under

- Coherus wins Humira patent ruling, chipping away at AbbVie’s defenses | BioPharma Dive, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.biopharmadive.com/news/coherus-humira-patent-abbvie-ipr-biosimilar/442950/

- Humira Patents Invalidated in Inter Partes Reviews | Morgan Lewis …, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.jdsupra.com/legalnews/humira-patents-invalidated-in-inter-14241/

- PTAB Denies Institution Of IPR On Two Humira Patents | Insights …, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.goodwinlaw.com/en/insights/blogs/2018/02/ptab-denies-institution-of-ipr-on-two-humira-paten

- Sandoz’s Challenge to Two of AbbVie’s Humira® Patents Denied by PTAB, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.biosimilarsip.com/2018/02/26/sandozs-challenge-two-abbvies-humira-patents-denied-ptab/

- IN THE COURT OF CHANCERY OF THE STATE OF DELAWARE ABBVIE INC. and ABBVIE BIOTECHNOLOGY LTD, Plaintiffs, v. COHERUS BIOSCIENCES, – Big Molecule Watch -, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.bigmoleculewatch.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2023/06/DE_CHA_STW_2023_0617_SG_d179206145e1437_PUBLIC_Verified_Complaint_for_Breach_of_Contract.pdf

- PTAB Year in Review – The PTAB Continues to Shape Application of the Lead-Compound Analysis in Chemical Obviousness Cases | Sterne Kessler, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.sternekessler.com/news-insights/insights/ptab-year-in-review-the-ptab-continues-to-shape-application-of-the-lead-compound-analysis-in-chemical-obviousness-cases/

- Latest Developments in Pharmaceutical IP Law: Obviousness Before the Patent Trial and Appeal Board | Articles | Finnegan, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.finnegan.com/en/insights/articles/latest-developments-in-pharmaceutical-ip-law-obviousness-before.html

- Describing Written Description: the Implications ofAriad, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.venable.com/-/media/files/publications/2010/06/theimplicationsofariad.pdf

- The Federal Circuit’s Recent Written Description Ruling in Allergan v. MSN Labs: Implications for Pharmaceutical Patent Drafting and Litigation, accessed August 16, 2025, https://patentlyo.com/patent/2024/08/description-implications-pharmaceutical.html

- Case Studies and Trends at the PTAB Involving 35 U.S.C. § 112 | Sterne Kessler, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.sternekessler.com/news-insights/insights/case-studies-and-trends-ptab-involving-35-usc-ss-112/

- Juno v. Kite: Written Description and Claiming Antibodies and …, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.proskauer.com/blog/juno-v-kite-written-description-and-claiming-antibodies-and-chimeric-antigen-receptorslessons-for-patent-prosecutors

- In Juno v. Kite the Federal Circuit Strikes Down Patent Directed Towards Pioneering Innovation in CAR T-Cell Therapy, accessed August 16, 2025, https://irlaw.umkc.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1221&context=faculty_works

- At California Central District Court Juno Therapeutics, Inc. et al v. Kite Pharma, Inc. – Multi-party Patent Infringement, accessed August 16, 2025, https://pharmaceuticalintelligence.com/2019/03/11/at-california-central-district-court-juno-therapeutics-inc-et-al-v-kite-pharma-inc-multi-party-patent-infringement/

- The PTAB Axes Skin Treatment Patent Under Amgen – MoFo Life Sciences, accessed August 16, 2025, https://lifesciences.mofo.com/topics/the-ptab-axes-skin-treatment-patent-under-amgen

- Effective Drug Patent Prosecution Strategies: Securing Your Pharmaceutical Innovations, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/effective-drug-patent-prosecution-strategies-securing-your-pharmaceutical-innovations/

- Patent protection strategies – PMC, accessed August 16, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3146086/

- Post-Grant Practice | Quinn Emanuel Urquhart & Sullivan, LLP, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.quinnemanuel.com/practice-areas/post-grant-practice/

- Thryv v. Click-to-Call Technologies: Time-Bar Determination by PTAB is Not Appealable, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.taftlaw.com/news-events/law-bulletins/thryv-v-click-to-call-technologies-time-bar-determination-by-ptab-is-not-appealable/

- Key Predictors and Strategic Implications of Early Patent Challenges for FDA-Approved Drugs – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/study-reveals-key-predictors-of-early-patent-challenges-for-fda-approved-drugs/

- Predicting patent challenges for small-molecule drugs: A cross-sectional study – PMC, accessed August 16, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11867330/

- You Don’t Need to Win the Patent — You Need to Win the Market: What No One Tells You About Winning Drug Patent Challenges – DrugPatentWatch – Transform Data into Market Domination, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/you-dont-need-to-win-the-patent-you-need-to-win-the-market-what-no-one-tells-you-about-winning-drug-patent-challenges/

- PHARMACEUTICAL – Williams & Connolly LLP, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.wc.com/portalresource/lookup/poid/Z1tOl9NPluKPtDNIqLMRVPMQiLsSwOZDmG3!/document.name=/Westlaw%20Journal%20Pharmaceutical_February%202017_Reverse%20Patent%20Trolling%20Nontraditional%20Participants%20in%20the%20Inter%20Partes%20Review%20Process_A.Perlman;%20K.Kayali.pdf

- Who is Kyle Bass and Why is He Filing so Many IPR Petitions? – Juristat Blog, accessed August 16, 2025, https://blog.juristat.com/who-is-kyle-bass-and-why-is-he-filing-so-many-ipr-petitions

- USPTO Permits Hedge Fund Patent Challenges – Wolters Kluwer, accessed August 16, 2025, https://legalblogs.wolterskluwer.com/patent-blog/uspto-permits-hedge-fund-patent-challenges/

- Kyle Bass’ First IPR Win At The PTAB – Mintz, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.mintz.com/insights-center/viewpoints/2016-10-28-kyle-bass-first-ipr-win-ptab

- Hedge Fund Drug Patent Challenges In Doubt After Bass’ Test – Sterne Kessler, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.sternekessler.com/news-insights/news/hedge-fund-drug-patent-challenges-doubt-after-bass-test/

- Hedge Fund Drug Patent Challenges In Doubt After Bass’ Test …, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.sternekessler.com/news-insights/news/hedge-fund-drug-patent-challenges-doubt-after-bass-test

- 16-969 SAS Institute Inc. v. IANCU (04/24/2018) – Supreme Court, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/17pdf/16-969_f2qg.pdf

- Thryv, Inc. v. Click-To-Call Technologies, LP | Supreme Court Bulletin – Law.Cornell.Edu, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.law.cornell.edu/supct/cert/18-916

- Thryv, Inc. v. Click-To-Call Technologies, LP – Wikipedia, accessed August 16, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thryv,_Inc._v._Click-To-Call_Technologies,_LP

- Thryv, Inc. v. Click-To-Call Technologies, LP – SCOTUSblog, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.scotusblog.com/cases/case-files/thryv-inc-v-click-to-call-technologies-lp/

- Thryv, Inc. v. Click-To-Call Technologies, LP | Oyez, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.oyez.org/cases/2019/18-916

- Thryv, Inc. v. Click-To-Call Technologies, Inc., 140 S. Ct. 1367 (2020) | Sterne Kessler, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.sternekessler.com/news-insights/insights/thryv-inc-v-click-call-technologies-inc-140-s-ct-1367-2020/

- PREVAIL Act Fact Sheet, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.coons.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/prevail_act_fact_sheet1.pdf

- PREVAIL Act Advances to the Senate: Potential Implications for Patent Challenges, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.jenner.com/en/news-insights/publications/prevail-act-advances-to-the-senate-potential-implications-for-patent-challenges

- Bipartisan Push for Patent Law Reform | Crowell & Moring LLP, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.crowell.com/en/insights/client-alerts/bipartisan-push-for-patent-law-reform

- Takeaways From the Proposed PREVAIL Act, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.fbm.com/publications/takeaways-from-the-proposed-prevail-act/

- Navigating the PTAB’s New Discretionary Denial Landscape – Fenwick, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.fenwick.com/insights/publications/navigating-the-ptabs-new-discretionary-denial-landscape-strategic-shifts-for-patent-challenges

- USPTO Acting Director Denies IPR Institution Based on “Settled Expectations” – Jones Day, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.jonesday.com/en/insights/2025/06/uspto-director-denies-ipr-institution-based-on-settled-expectations

- Settled Expectations: When is a Patent Safe from Challenge at the PTAB? – IPWatchdog.com, accessed August 16, 2025, https://ipwatchdog.com/2025/08/04/settled-expectations-when-is-a-patent-safe-from-challenge-at-the-ptab/id=190883/