Artificial Intelligence (AI) is no longer a futuristic buzzword confined to academic papers; it is a powerful, active engine of discovery, rewriting the fundamental economics of research and development. We are rapidly moving from a high-cost, high-failure model of serendipitous discovery to a faster, more predictive, data-driven paradigm. The numbers are staggering: AI is projected to generate up to $410 billion in annual value for the pharmaceutical sector by 2025 and could be responsible for the discovery of 30% of new drugs in the same timeframe.1

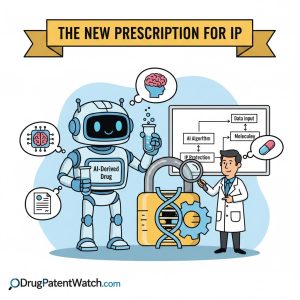

But this revolution extends far beyond the laboratory. The rise of AI doesn’t just accelerate R&D; it fundamentally reshapes the strategic calculus of intellectual property, the very bedrock upon which the industry’s business model is built. For decades, the composition of matter patent—the “gold standard” protecting the molecule itself—has been the undisputed king of the IP chessboard. It was the primary mechanism for recouping the billions of dollars and decade-plus of work required to bring a new therapy to market. Now, this cornerstone of pharmaceutical IP faces new, formidable challenges in the AI era. Simultaneously, the method-of-use patent, often seen as a secondary tool for lifecycle management, is poised to become a primary strategic asset, perfectly suited to the unique strengths of AI-driven discovery.

This report is not another breathless overview of AI’s potential. It is a strategic guide for the decision-makers on the front lines: the IP strategists, R&D leaders, business development teams, and investors who must navigate this new and treacherous landscape. We will dissect the critical legal and commercial questions that arise when a machine plays a central role in the inventive process. We will move from foundational patent principles to the specific impact of AI on the discovery pipeline, then delve into the thorny legal hurdles of inventorship and non-obviousness. Finally, we will synthesize this analysis into a practical framework for choosing the right patent for your AI-derived asset and offer a forward-looking perspective on the future of pharmaceutical IP. For those who are skeptical of hype and demand actionable, data-driven insights, this is your new prescription for turning AI-driven innovation into defensible, high-value intellectual property.

The Twin Pillars of Pharmaceutical IP: A Primer on Compound and Method-of-Use Patents

Before we can appreciate the seismic shifts AI is causing, we must first solidify our understanding of the traditional landscape. A pharmaceutical patent portfolio is not a monolithic entity; it is a carefully constructed fortress with different types of patents serving as its walls, moats, and keeps. At the core of this defensive structure are two pillars: the composition of matter patent and the method-of-use patent. Understanding their distinct roles, strengths, and limitations is the essential foundation for navigating the complexities of the AI era.

The Gold Standard: Unpacking the Power of the Composition of Matter Patent

The composition of matter patent, also known as a compound or product patent, is the undisputed cornerstone of pharmaceutical IP.2 It is the broadest and most powerful form of protection available, covering the new chemical entity (NCE) or new molecular entity (NME) itself—the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) that forms the core of the medicine.3

This patent claims the specific chemical structure of the drug molecule. Its power lies in its breadth and simplicity. If a competitor’s product contains the patented molecule, it infringes the patent. Period. It does not matter how the molecule was manufactured, what inactive ingredients it is formulated with, or for which disease it is being used.4 This “iron-clad” protection provides a nearly absolute barrier to entry for generic competitors for the life of the patent.6

To secure this powerful asset, an invention must meet the core patentability requirements:

- Novelty: The molecule must be new and not previously disclosed in any public forum.7

- Non-Obviousness (Inventive Step): The invention must not be an obvious modification of a known compound to a “person having ordinary skill in the art” (PHOSITA). This is often the most subjective and heavily litigated requirement.3

- Utility: The invention must have a specific, substantial, and credible use, which for a drug means a demonstrated therapeutic effect.3

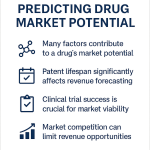

The strategic value of the compound patent cannot be overstated. It is the primary legal and economic tool that allows a company to recoup the vast costs associated with drug development—an investment now estimated at a staggering $2.6 billion per approved drug.8 By granting a temporary monopoly, typically for 20 years from the patent’s filing date, it provides the period of market exclusivity necessary to generate a return on this high-risk investment.2 This exclusivity is the very engine of the pharmaceutical business model, incentivizing the continuous research that leads to life-saving medications.11

The Lifecycle Extender: The Strategic Value of the Method-of-Use Patent

If the compound patent is the foundation of the IP fortress, the method-of-use patent is the series of strategic fortifications built to extend its defensive perimeter over time. A method-of-use (or simply “use”) patent does not protect the drug itself but rather protects a new way of using a known compound.2 This is the legal foundation for one of the most valuable strategies in the pharmaceutical playbook: drug repurposing.3

Imagine a company has a drug that is approved and patented for treating hypertension. Years later, researchers discover that this same drug is also highly effective at treating a completely different condition, such as alopecia. The company can then file for a method-of-use patent on “a method of treating alopecia by administering compound X.”

The scope of this protection is inherently narrower than that of a compound patent. It only prevents competitors from marketing the drug for the specific patented use (in this case, alopecia).5 A generic manufacturer could still, in theory, sell the drug for its original, off-patent use (hypertension). However, its strategic value is immense. It serves as a critical tool for “evergreening,” or lifecycle management, allowing companies to extend market exclusivity for a valuable asset well beyond the expiration of its original compound patent.11 The data bears this out: a remarkable 72% of patents for top-selling drugs are filed

after initial FDA approval, with method-of-use patents constituting a substantial 41% of these post-approval filings.13 This demonstrates a clear strategic shift in the industry from focusing solely on the initial discovery to continuously innovating and protecting a drug throughout its commercial life.

A Tale of Two Scopes: Comparing Breadth, Strength, and Enforcement

The strategic choice between—or combination of—these two patent types hinges on their fundamental differences in scope, strength, and ease of enforcement.

- Breadth of Protection: A compound patent protects the “what”—the physical entity of the molecule itself. A method-of-use patent protects the “how”—the specific application or process of using that molecule to achieve a therapeutic result.5 The former is broad and absolute; the latter is targeted and conditional.

- Strength and Enforcement: Proving infringement of a compound patent is relatively straightforward. A simple chemical analysis can determine if the patented molecule is present in a competitor’s product. Enforcement of method-of-use patents is far more complex. It often hinges on the legal doctrine of “induced infringement,” where the brand company must prove that a generic competitor’s marketing and product labeling actively encourages doctors to prescribe the drug for the patented (and not just the off-patent) use. This has led to intricate legal battles over “skinny labels” or “carve-outs,” where generic companies attempt to omit the patented indication from their product information.16 However, recent legal developments, such as the Federal Circuit’s decision in

GSK v. Teva (often referred to as Coreg II), have strengthened the hand of brand-name companies, making it riskier for generics to use label carve-outs and thereby increasing the value and enforceability of method-of-use patents.16

This strategic layering of different patent types—compound, method-of-use, formulation, manufacturing process—is what gives rise to the modern “patent thicket.” This dense and overlapping network of IP rights is not designed to protect a single invention but to create a formidable, multi-layered barrier to entry that makes it legally and financially challenging for competitors to launch a generic version.3

The industry’s evolution towards this lifecycle-centric IP model is not merely a clever legal tactic; it is a direct economic response to the immense and ever-present pressure of patent term erosion. The statutory 20-year patent term is a fixed and unforgiving clock that starts ticking from the moment of filing, often very early in the discovery process.9 The grueling R&D and regulatory approval gauntlet consumes a massive portion of this term—often 10 to 15 years—leaving a company with a frighteningly short window of just 7 to 10 years of effective market exclusivity to recoup its multi-billion-dollar investment.8 This creates a “profitability gap” that threatens the viability of the entire innovation model. In response, companies were forced to innovate their IP strategies to survive. This economic imperative drove the rise of secondary patents, particularly method-of-use patents filed after initial approval, to claw back value and extend the commercial life of a drug.13 The patent thicket, therefore, is not just an aggressive legal strategy; it is an evolutionary adaptation to a harsh economic environment defined by the ever-looming patent cliff.

The New Engine of Discovery: How AI is Rewriting the Rules of Pharmaceutical R&D

The traditional drug discovery process has long been characterized as a funnel: slow, expensive, and fraught with failure. For every 10,000 compounds screened, only a handful make it to clinical trials, and only one ultimately receives approval. This process can take over a decade and cost billions. AI is not just optimizing this funnel; it is fundamentally reshaping it into a powerful, predictive engine. By processing and finding patterns in biological and chemical data at a scale and speed that is simply beyond human capacity, AI is transforming every stage of the R&D pipeline, setting the stage for a new era of intellectual property challenges and opportunities.

From Target to Candidate: AI’s Impact Across the Discovery Pipeline

AI’s influence is not confined to a single step but is being woven into the entire fabric of drug discovery and development.

- Target Identification and Validation: The journey begins with identifying a biological target—a protein or gene implicated in a disease. Traditionally, this has been a painstaking process. AI now supercharges it by analyzing vast, disparate datasets, including genomics, proteomics, scientific literature, and clinical trial data, to identify and validate novel drug targets with unprecedented speed.18 Systems like DeepMind’s AlphaFold, which can accurately predict the 3D structure of proteins, have been a game-changer, allowing scientists to understand a target’s architecture and begin designing drugs to bind to it almost immediately.22

- De Novo Drug Design: For decades, “discovery” meant screening massive libraries of existing chemical compounds in the hope of finding a “hit.” Generative AI flips this paradigm on its head. Instead of searching, it creates. These models can design entirely new, or de novo, molecules from scratch, optimized for specific properties like high potency, low toxicity, and ease of synthesis.22 This represents a monumental shift in the inventive process, moving from discovery to design and vastly expanding the universe of potential medicines.

- Efficacy and Toxicity Prediction: One of the primary reasons for the industry’s staggering 90% clinical trial failure rate is that drugs that look promising in the lab turn out to be either ineffective or toxic in humans.18 AI is tackling this problem head-on. By training on historical data, machine learning models can predict a drug candidate’s safety and efficacy profile

in silico (on a computer) before a single dollar is spent on costly and time-consuming laboratory experiments or clinical trials.18 This “fail fast, fail cheap” approach allows researchers to prioritize the most promising candidates and de-risk the entire development pipeline. - Drug Repurposing: AI’s ability to see connections that humans miss is perhaps nowhere more valuable than in drug repurposing. By analyzing complex networks of biological, chemical, and clinical data, AI algorithms can identify surprising new therapeutic uses for existing drugs, many of which may be off-patent.14 This capability is a direct and powerful engine for the creation of new method-of-use patents, unlocking hidden value in established medicines.

Case Studies in Acceleration: Highlighting Successes from AI-Native Biotechs

This is not a distant future; the proof of AI’s impact is already entering the clinic. A new breed of “AI-native” biotech companies is demonstrating the transformative power of these technologies.

- Insilico Medicine: Perhaps the most prominent poster child for the AI revolution, Insilico Medicine used its end-to-end AI platform to take a novel drug for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), a deadly lung disease, from initial target discovery to the start of Phase II clinical trials. This achievement, which involved both an AI-discovered novel target and an AI-designed novel molecule (INS018_055), was accomplished in a fraction of the time and cost of traditional methods, marking a true landmark for the industry.22

- Exscientia: This UK-based company was the first to have an AI-designed molecule enter human clinical trials, demonstrating early on that AI could move from theoretical design to real-world application.1

- Relay Therapeutics and Recursion: These companies, among others, have also advanced AI-discovered assets into clinical trials. Relay’s RLY-2608 for breast cancer and Recursion’s REC-994 for cerebral cavernous malformation are further evidence that AI is not just a research tool but a viable engine for producing clinical-stage candidates.39

The economic implications are profound. By automating and optimizing key stages of R&D, AI has the potential to reduce drug discovery costs by up to 40% and slash development timelines from over five years to as little as 12-18 months.1

Blockquote:

According to a Morgan Stanley analysis, even “modest improvements in early-stage drug development success rates enabled by the use of artificial intelligence and machine learning” could result in an additional 50 novel therapies over a 10-year period, representing a more than $50 billion opportunity.22

This acceleration creates a fundamental paradox that lies at the heart of our discussion on patent strategy. While generative AI dramatically increases the supply of novel molecules, it simultaneously threatens their patentability by potentially rendering them “obvious” in the eyes of the law. Generative models can create millions of novel, drug-like compounds, vastly expanding the chemical space available for exploration and seemingly paving the way for a boom in compound patent filings.25 However, the legal standard of non-obviousness is judged from the perspective of a Person Having Ordinary Skill in The Art (PHOSITA).41 As AI tools become ubiquitous in the industry, the capabilities of this hypothetical expert will be assumed to include the proficient use of these very tools, creating what we can call an “AI-augmented PHOSITA”.42 If a standard, widely available AI model can generate a specific molecule with a relatively simple prompt—for example, “design a novel kinase inhibitor with these properties”—a patent examiner or a court could deem that molecule “obvious to try” and therefore unpatentable.42 This creates an inherent conflict: the very technology that makes it easy to

create a new molecule also makes it harder to patent that same molecule. The strategic value of a de novo AI-generated compound patent is therefore not as straightforward as it appears and will depend heavily on a company’s ability to demonstrate human ingenuity that goes far beyond the standard output of the AI.

The Crucible of Patentability: Navigating the Legal Gauntlet for AI-Derived Drugs

The integration of AI into the inventive process has thrown a wrench into the centuries-old machinery of patent law. The core requirements for patentability—inventorship, non-obviousness, and adequate disclosure—were all conceived in an era of purely human ingenuity. Now, patent offices, courts, and companies are grappling with how to apply these principles when a key contributor to the “eureka moment” is an algorithm. For any company seeking to protect its AI-derived assets, understanding and proactively addressing these legal challenges is not just a matter of compliance; it is a prerequisite for survival.

The Inventorship Dilemma: Who is the Inventor When AI is the Co-Pilot?

The most fundamental question AI poses to the patent system is also the most existential: who, or what, is the inventor?

The Legal Bedrock: Thaler v. Vidal

For several years, this question was the subject of a global legal campaign led by Dr. Stephen Thaler, who filed patent applications worldwide listing his AI system, DABUS, as the sole inventor. This effort culminated in the United States with the landmark 2022 Federal Circuit decision in Thaler v. Vidal. The court’s ruling was unequivocal: under the plain language of the U.S. Patent Act, which refers to inventors as “individuals,” an inventor must be a “natural person.” An AI system, therefore, cannot be named as an inventor on a U.S. patent.35 This decision, which the Supreme Court declined to review, settled the issue in the U.S. and aligned with the positions of the European Patent Office (EPO) and the UK Intellectual Property Office, establishing a clear, human-centric requirement for inventorship.44

The USPTO’s Response: The 2024 Guidance

While Thaler closed the door on AI as an inventor, it left open a much more practical and pressing question: are inventions patentable when they are created with the assistance of AI? In February 2024, the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) provided much-needed clarity by issuing its “Inventorship Guidance for AI-Assisted Inventions.” The guidance affirmed that AI-assisted inventions are patentable, but only if one or more natural persons have made a “significant contribution” to the invention.35 This shifted the focus from the AI’s role to the nature and quality of the human involvement.

Applying the Pannu Factors: A Practical Guide for R&D Teams

To determine what constitutes a “significant contribution,” the USPTO directed its examiners to use the long-standing legal test from the case Pannu v. Iolab Corp.. While traditionally used to determine joint inventorship among humans, these factors now provide the framework for assessing the human-AI partnership. To be named an inventor, a person must meet all three Pannu factors:

- Contribute in some significant manner to the conception or reduction to practice of the invention.

- Make a contribution that is not insignificant in quality, when measured against the dimension of the full invention.

- Do more than merely explain well-known concepts or the current state of the art to the other inventors. 35

For R&D and legal teams, this abstract legal test must be translated into concrete actions. Based on the USPTO’s guidance and its accompanying examples, we can delineate what is likely to be considered a sufficient versus an insufficient human contribution in a drug discovery context:

- Sufficient Contributions (Likely to Confer Inventorship):

- Designing a specialized AI model or significantly modifying an existing one to solve a specific biological problem.

- Curating a novel or proprietary dataset to train the AI, thereby guiding its output in a unique way.

- Constructing a highly specific and detailed prompt for the AI that constrains the search space and guides it toward a particular solution, rather than just asking a general question.

- Critically analyzing the AI’s output, identifying the most promising candidates from a large set of options, and iteratively refining the AI’s suggestions based on human scientific judgment.

- Performing wet-lab experiments that validate the AI’s prediction and, crucially, reveal unexpected properties or confirm a function that was not predictable (simultaneous conception and reduction to practice). 35

- Insufficient Contributions (Unlikely to Confer Inventorship):

- Merely presenting a general problem to an off-the-shelf AI tool (e.g., “find a drug for Alzheimer’s”).

- Simply owning or overseeing the AI system used in the discovery process.

- Recognizing and reducing to practice (i.e., synthesizing) a molecule proposed by an AI, where the molecule’s properties and utility would be apparent and expected by a skilled chemist. 49

This new legal standard has a profound operational consequence: the documentation imperative. Internal record-keeping is no longer just a matter of good scientific practice; it is now a critical legal requirement. Detailed, contemporaneous logs of the entire inventive process—including the specific prompts given to the AI, the rationale for selecting certain training data, the decision-making process for prioritizing AI outputs, and the results of all validation experiments—are essential pieces of evidence needed to defend a patent’s validity against an inventorship challenge.35

The Evolving Standard of Obviousness: Is Anything Non-Obvious to an AI?

Beyond inventorship, the most significant challenge AI poses is to the doctrine of non-obviousness. A patent cannot be granted if the invention would have been “obvious” to a Person Having Ordinary Skill in The Art (PHOSITA) at the time the invention was made. But what happens when the “ordinary skill” of that person includes access to powerful AI?

- The AI-Augmented PHOSITA: As AI tools for target identification, molecule generation, and data analysis become standard and ubiquitous in the pharmaceutical industry, the baseline for what is considered “ordinary skill” is inevitably being raised.42 The hypothetical PHOSITA of tomorrow is an AI-augmented one. This means that an invention’s patentability will be judged not against what a human scientist could do alone, but against what a human scientist equipped with standard AI tools could predictably achieve. A molecule that could be generated with relative ease by a common AI model might be deemed “obvious to try” and thus unpatentable.36

- The Threat of AI-Generated Prior Art: A related danger is the potential for the vast number of theoretical molecules designed by AI systems to be considered “prior art,” even if they have never been synthesized. If an AI generates and publicly discloses millions of molecular permutations, it could create a minefield of prior art that makes it incredibly difficult for a later inventor who actually synthesizes and tests a similar molecule to prove that their invention is novel and non-obvious.43

- The Strategic Defense: Unexpected Results: The most powerful defense against an obviousness challenge has always been the demonstration of “unexpected results.” This argument becomes even more critical in the AI era. The key is to prove that the AI-derived invention exhibits surprising properties or works in a way that would not have been predicted by a skilled person, even one using AI. This is particularly potent for method-of-use patents. For example, in the case In re Cyclobenzaprine, the Federal Circuit upheld a patent for a new use of a known drug because an AI model’s prediction of its mechanism of action diverged from established scientific understanding, making the discovery unpredictable and non-obvious.36 The inventive step was not just finding the new use, but uncovering a surprising biological link that the AI made visible.14

Novelty and Enablement: Piercing the “Black Box”

Finally, any patent application must satisfy the disclosure requirements of 35 U.S.C. § 112, which mandates that the patent provides a written description of the invention in sufficient detail to enable a skilled person to make and use it without undue experimentation.14

- The “Black Box” Problem: This presents a unique challenge for certain types of AI, particularly deep learning neural networks, whose internal decision-making processes can be opaque or a “black box.” It may be difficult, if not impossible, to explain precisely how the AI arrived at its proposed solution.41 If the inventive step is claimed to be within the AI’s process, but that process cannot be adequately described, the patent could fail the enablement requirement.

- A Practical Strategy: The most effective way to navigate this is to shift the focus of the disclosure from the AI’s internal workings to the reproducible elements of the process. The patent application should meticulously describe:

- The Inputs: The specific problem being solved, the curated datasets used for training or analysis, and the precise prompts used to guide the AI.

- The Outputs: The final chemical structure, its measured properties, and its demonstrated utility.

- The Validation: The human-led experimental process used to synthesize, test, and confirm the AI’s output.

The goal is to enable a skilled person to replicate the result, even if they cannot replicate the AI’s exact “thought process.” By providing a robust, data-backed description of the validated invention, applicants can satisfy the disclosure requirements without needing to fully demystify the AI’s black box.41

The current legal framework, as shaped by the USPTO’s guidance, creates a powerful and perhaps unintended incentive. It pushes companies to develop and utilize specialized, proprietary AI systems rather than relying solely on generic, off-the-shelf models. The logic is clear: the guidance states that designing, building, or training an AI for a specific problem to elicit a particular solution is a strong indicator of a “significant contribution” to inventorship.35 Conversely, using a general-purpose tool provides a much weaker claim. Furthermore, an output from a widely available, standard AI model is far more vulnerable to an obviousness challenge from the perspective of the AI-augmented PHOSITA.42 Therefore, to build the most defensible patent, a company is better positioned if it can argue that its invention resulted from a unique, human-guided AI tool that is itself not part of the “ordinary skill in the art.” This strategy creates a competitive moat not just around the resulting drug, but around the discovery

platform itself, encouraging innovation in the AI models and strengthening the case for protecting the platform as a valuable trade secret while patenting its output.

The Strategic Chessboard: Choosing the Right Patent for Your AI-Discovered Asset

With a clear understanding of the patent types and the new legal hurdles, we can now move from theory to practice. The central question for any IP strategist in this new era is: Which type of patent provides the most robust, defensible, and valuable protection for our AI-driven discovery? The answer is not one-size-fits-all. It depends entirely on the nature of the discovery itself—whether AI has generated a brand-new molecule from scratch or uncovered a hidden use for an old one. This is the strategic chessboard where the choice between a compound patent and a method-of-use patent will determine the long-term value of your asset.

Protecting the Crown Jewel: When a Compound Patent is the Right Move

A composition of matter patent remains the most powerful form of protection, and it should be the primary goal when the circumstances are right.

- The Ideal Scenario: This strategy is best suited for a truly novel molecule generated through a de novo design process, where the human-AI collaboration was deep and iterative, and where significant human ingenuity can be clearly demonstrated. This is not for a molecule that an off-the-shelf AI spits out after a single prompt. It is for a candidate that results from a sophisticated, multi-step process of human-guided refinement.

- Strengths: If granted, it offers the broadest possible protection, blocking all uses of the molecule and providing a clear path to market exclusivity.

- Key Actions to Ensure Patentability:

- Meticulously Document Inventorship: The burden of proof is on you. You must create an evidentiary record that demonstrates significant human contribution at every critical stage. This includes the design of the AI prompt, the selection and curation of training data, and, most importantly, the iterative refinement and validation of the AI’s output. Show how human scientific judgment guided the process, selected from among many AI suggestions, and modified the final candidate to improve its properties.41

- Build a Strong Non-Obviousness Case: This is the highest hurdle. The patent application must preemptively address the “AI-augmented PHOSITA” by demonstrating that the final molecule has unexpected properties or solves a problem in a way that would not have been predictable, even with standard AI tools. The narrative should focus on what made the human-AI collaboration inventive, not just the final structure.

- Provide Robust Enablement: The “black box” cannot be an excuse for a lack of data. The application must be supported by robust experimental evidence, including the successful wet-lab synthesis of the molecule and data from biological assays that prove it can be made and has the claimed therapeutic utility.14

Unlocking Hidden Value: Why Method-of-Use Patents are the Ace in the Hole for AI

While the compound patent for a de novo molecule faces a steep uphill battle on non-obviousness, the method-of-use patent for an AI-repurposed drug is in a much stronger position. In many ways, this is the intellectual property type that is most naturally aligned with AI’s core strengths.

- The Ideal Scenario: This strategy is perfect for discoveries made through AI-powered drug repurposing, where an AI platform sifts through massive biological and clinical datasets to identify a new therapeutic use for a known, often off-patent, drug.

- Strengths: AI excels at finding non-obvious patterns and hidden correlations in complex data. This aligns perfectly with the legal requirements for a strong method-of-use patent, where the inventive step is the discovery of a new, unexpected biological link. The non-obviousness argument is often far more compelling here than for a de novo compound. Why would a skilled person have thought to test an old hypertension drug for alopecia? Because the AI found a previously unknown link in the data that no human had spotted.

- Key Actions to Ensure Patentability:

- Focus the Narrative on the Unexpected Link: The invention is not the drug; it’s the discovery of the new biological pathway or mechanism of action. The patent application’s narrative must emphasize the surprising and unpredictable nature of this connection, which the AI uncovered and human scientists subsequently validated through experimentation.36

- Demonstrate Inventorship: Human contribution is still essential but can be more straightforward to prove. It involves framing the specific biological question for the AI, interpreting the significance of the AI’s findings, designing the crucial experiments to confirm the new use, and analyzing the results.

- Highlight Commercial Value: This is a highly cost-effective R&D strategy that can breathe new life into old, well-characterized assets with known safety profiles. It creates immense value with substantially lower risk and a much shorter path to the clinic, making it an incredibly attractive proposition for investors.14

Building the Fortress: Integrating Both Patent Types into a Resilient “Patent Thicket”

The most sophisticated and resilient IP strategy does not treat this as an either/or choice. Instead, it uses both patent types to construct a multi-layered “patent thicket” that is supercharged by AI.

- The Hybrid Strategy: A company can pursue an initial compound patent for a new AI-derived molecule. Then, over the following years, it can use its AI platform to continuously mine new data and uncover additional therapeutic indications for that same molecule. Each new, validated discovery can become the basis for a new method-of-use patent.

- A Layered Defense for Lifecycle Management: This creates a powerful, layered defense. Even after the foundational compound patent expires 20 years from its filing date, the company could still hold multiple method-of-use patents that protect the most lucrative markets for that drug for years to come. This transforms the patent thicket from a static defense into a dynamic, evolving strategy, where AI continuously feeds the pipeline of lifecycle-extending IP.

To crystallize these strategic considerations, the following table provides a direct comparison for IP decision-makers.

| Strategic Factor | Compound Patent (for De Novo AI Molecules) | Method-of-Use Patent (for AI-Repurposed Drugs) |

| Subject of Protection | The novel chemical entity (API) itself. | A new therapeutic use for a known chemical entity. |

| Primary AI Application | Generative AI for de novo molecule design. | Predictive AI for analyzing datasets to find new drug-target interactions. |

| Key Inventorship Challenge | Proving “significant human contribution” in guiding, refining, and validating the AI’s creative output. | Demonstrating human contribution in framing the problem, interpreting AI’s findings, and designing validation experiments. |

| Key Non-Obviousness Challenge | Demonstrating ingenuity beyond the predictable output of a standard AI (overcoming the “AI-augmented PHOSITA”). | Leveraging the AI’s discovery of a surprising and unexpected biological link or mechanism of action. |

| Strength of Protection | Very broad; blocks all uses of the molecule. | Narrower; blocks only the specific patented use. |

| Enforcement Complexity | Low; infringement is proven by presence of the molecule. | High; often requires proving induced infringement based on competitor’s labeling and marketing. |

| Strategic Value | Secures foundational market exclusivity for a new drug; high-risk, high-reward. | Extends market lifecycle of an asset; lower-risk, highly cost-effective way to generate new revenue streams. |

| Real-World Example Vector | Insilico Medicine’s INS018_055 (novel AI-designed molecule for IPF). | BenevolentAI’s identification of baricitinib (an existing arthritis drug) for treating COVID-19. |

The Future Frontier: Predictive Patentability and the Next Generation of IP Strategy

The impact of AI on pharmaceutical IP is not a static event but an ongoing evolution. As AI tools become more powerful and integrated into every facet of R&D, they will inevitably begin to reshape the very practice of intellectual property law and strategy. The next frontier is not just about using AI to create inventions, but about using AI to predict their legal and commercial viability from day one. This shift promises to transform IP from a reactive, defensive function into a proactive, predictive engine of corporate strategy.

Beyond Human Intuition: The Rise of AI-Powered Patent Analytics

For decades, assessing the patentability of a new drug candidate has been a largely manual, qualitative process, relying on the experience and intuition of patent attorneys. This assessment typically happens late in the preclinical stage, after millions of dollars have already been invested. AI is poised to turn this model on its head.

- The Concept of Predictive Patentability: The new paradigm involves leveraging machine learning and natural language processing to analyze the entire universe of existing patents, scientific literature, and clinical trial data. By training on this massive corpus, AI systems can generate a “patentability score” for a new compound at the earliest stages of discovery.42 This score can quantify the probability of overcoming novelty and non-obviousness challenges, identifying potential prior art that a human search might miss.

- The Strategic Impact: This transforms IP from a late-stage legal hurdle into an early-stage, quantitative input for financial modeling and portfolio management. A “go/no-go” decision on a research program can now be informed by a data-driven prediction of its IP strength. This allows companies to de-risk their R&D pipeline in an unprecedented way, avoiding catastrophic misallocations of capital on compounds that are doomed to fail not in the clinic, but in the patent office.42

The Role of Strategic Tools: Leveraging Platforms like DrugPatentWatch

This new era of predictive IP strategy is impossible without access to high-quality, structured, and interconnected data. This is where strategic intelligence platforms become indispensable.

- Fueling Competitive Intelligence: Platforms like DrugPatentWatch are essential for this new approach. They provide the critical, curated data needed to train predictive patentability models. More importantly, they empower human experts to conduct sophisticated prior art searches, analyze the patent portfolios of competitors to identify strategic gaps, and track patent expirations to anticipate market shifts.53

- Connecting the Dots for a Holistic View: The value of these tools extends beyond a simple patent database. They serve as strategic intelligence hubs that connect patent data with crucial related information, such as FDA Orange Book listings, regulatory exclusivities, ongoing litigation records, and clinical trial information.4 This provides the holistic, multi-dimensional view required to make informed decisions in a complex, AI-driven landscape. A company can see not just a competitor’s patent, but the entire strategic ecosystem surrounding that asset.

The Great Unsettled Question: Will AI Erode the Economic Basis for Patents?

This brings us to a provocative and fundamental long-term question. The entire patent system is built on a grand bargain, a quid pro quo between society and the innovator. Society grants a temporary monopoly in exchange for the innovator undertaking the high cost, long timeline, and immense risk of developing a new invention.2

- The AI Disruption to the Bargain: But what happens when AI dramatically lowers that cost, shortens that timeline, and reduces that risk? If AI can discover and design a new drug in 18 months for a fraction of the traditional cost, does the societal justification for granting a 20-year market monopoly begin to weaken?.57 This is not a question for today’s patent applications, but it is a storm gathering on the horizon of IP policy.

- A Glimpse of the Future: We are likely to see intense future legislative and policy debates around the core tenets of the patent system in response to AI. This could include discussions about shorter patent terms for AI-derived drugs, higher standards for non-obviousness, or even the exploration of alternative incentive models, such as government-funded prize funds or tax incentives, to encourage innovation in areas where AI makes traditional patenting difficult.58

The future of pharmaceutical IP can be seen as a race between two powerful, opposing AI forces. On one side, we have “Generative AI,” which is focused on creating a torrent of new inventions—novel molecules and new uses. On the other side, we have an emerging “Predictive AI,” which is focused on analyzing the patentability of those very inventions by scouring the global IP landscape. A company that relies solely on generative AI is creating assets that may be highly vulnerable to invalidation by a competitor using predictive AI to unearth obscure prior art or construct a devastating obviousness argument. The winning strategy of the next decade will not be just using AI to invent faster. It will be to use a second, analytical layer of AI to “pressure-test” those inventions against the entire universe of public knowledge before committing significant resources. This creates a virtuous cycle where predictive patentability AI guides the generative R&D AI, steering it away from crowded, “AI-obvious” chemical spaces and toward territories that are truly inventive, legally defensible, and ultimately, more valuable. This is the next frontier of IP strategy.

Key Takeaways

The integration of Artificial Intelligence into drug discovery is not an incremental change but a fundamental paradigm shift that demands a complete re-evaluation of intellectual property strategy. The traditional playbook is no longer sufficient. For business leaders, IP counsel, and investors aiming to capitalize on this transformation, the following strategic imperatives are paramount:

- Embrace the Pivot to Method-of-Use Patents: While the allure of patenting a novel AI-generated molecule is strong, the legal hurdles—particularly proving non-obviousness in the face of an “AI-augmented” skilled person—are formidable and growing. The most immediate, defensible, and cost-effective strategic advantage lies in leveraging AI for drug repurposing. AI’s ability to uncover surprising, non-obvious biological links for existing drugs is perfectly aligned with the requirements for a strong method-of-use patent, creating a powerful engine for lifecycle management and new revenue generation.

- Documentation is Your First Line of Defense: In the post-Thaler world, proving “significant human contribution” is non-negotiable. R&D records must be treated as legal evidence. Meticulous, contemporaneous documentation of the entire human-AI interaction—from prompt engineering and data curation to the iterative refinement and experimental validation of AI outputs—is the essential foundation for defending the validity of any AI-assisted patent.

- Invest in Specialized, Proprietary AI: Relying on generic, off-the-shelf AI tools weakens your claim to both inventorship and non-obviousness. Developing or significantly tailoring specialized AI systems for specific biological problems creates a stronger argument that the human contribution was significant and that the resulting discovery was not a predictable output of a standard tool. This builds a competitive moat around both the drug and the discovery platform itself.

- Integrate IP Strategy at the Dawn of R&D: The era of treating patentability as a late-stage checkpoint is over. The rise of AI-powered predictive patentability analytics allows IP assessment to become a quantitative, data-driven input at the very beginning of the R&D process. Use these tools to de-risk your pipeline, guide research toward more defensible chemical spaces, and make smarter capital allocation decisions.

- Build a Multi-Layered “AI-Fed” Patent Thicket: The most resilient IP fortress will not rely on a single patent type. A successful strategy will pursue a foundational compound patent for truly inventive de novo molecules while simultaneously using AI to continuously discover new indications for those molecules, feeding a pipeline of valuable method-of-use patents. This dynamic, layered approach creates a durable competitive advantage that can extend market exclusivity long after the initial patent has expired.

Navigating this new frontier requires a blend of scientific innovation, legal acumen, and strategic foresight. The companies that thrive will be those that see AI not just as a tool for discovery, but as a catalyst for reimagining the very nature of intellectual property as a core driver of business value.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. Can our company get a patent if our AI platform discovered a new drug molecule entirely on its own, with no human input beyond starting the program?

Based on current U.S. law and USPTO guidance, the answer is no. The Thaler v. Vidal case firmly established that an inventor must be a “natural person” (a human). The USPTO’s 2024 guidance clarifies that for an AI-assisted invention to be patentable, a human must have made a “significant contribution” to the invention. If the AI operates autonomously to conceive of and design the molecule, and humans only recognize its output, it fails the inventorship test, and a valid U.S. patent cannot be obtained for that molecule.

2. How can we prove our AI-designed molecule is “non-obvious” if a competitor can argue their AI could have found it too?

This is the central challenge. The legal standard is evolving to consider an “AI-augmented” Person Having Ordinary Skill in The Art (PHOSITA). To prove non-obviousness, you must demonstrate human ingenuity that goes beyond the predictable output of a standard AI. Key strategies include: 1) Showing the invention resulted from a highly specialized, proprietary AI model that is not a standard tool in the field; 2) Documenting a complex, iterative process of human-AI collaboration where human scientific judgment guided the AI in non-obvious ways; and 3) Providing strong evidence of “unexpected results”—that the final molecule has surprising and beneficial properties that would not have been predicted even by AI.

3. Is it better to patent our AI-discovered drug or keep our AI discovery platform a trade secret?

This is not an either/or choice; the strongest strategy is to do both. You should pursue patents on the outputs of your AI—the novel molecules (compound patents) and new uses (method-of-use patents). Simultaneously, you should protect the AI platform itself—the algorithms, proprietary datasets, and unique training methodologies—as a trade secret. This dual approach creates multiple layers of protection. The patents protect your commercial products, while the trade secret protects the “secret sauce” of your discovery engine, preventing competitors from easily replicating your R&D process.

4. Our team used an off-the-shelf AI tool to identify a new use for an old drug. Who are the inventors?

The inventors are the human researchers who made a “significant contribution” to the discovery. The developers of the off-the-shelf AI tool are almost certainly not inventors. According to USPTO guidance, inventorship would likely belong to the team members who: 1) Framed the specific biological question and constructed the detailed prompt for the AI; 2) Interpreted the AI’s output to identify the promising new indication from the noise; and 3) Designed, conducted, and analyzed the crucial experiments that validated the new use. Merely operating the software is not enough; the key is the intellectual contribution to the conception and validation of the new therapeutic method.

5. With AI making drug discovery so much faster and cheaper, are we likely to see shorter patent terms in the future?

This is a significant long-term policy question. The 20-year patent term is a cornerstone of the industry’s economic model, justified by the high cost, risk, and time of traditional R&D. As AI begins to dramatically reduce all three of these factors, it fundamentally challenges that justification. While there are no immediate legislative proposals to shorten patent terms for AI-derived drugs, it is highly likely that this will become a major topic of debate among policymakers, academics, and industry stakeholders over the next decade. Companies should be aware that the foundational “quid pro quo” of the patent system may be re-evaluated as AI’s impact becomes more widespread.

Works cited

- AI in Pharma and Biotech: Market Trends 2025 and Beyond, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.coherentsolutions.com/insights/artificial-intelligence-in-pharmaceuticals-and-biotechnology-current-trends-and-innovations

- What are the types of pharmaceutical patents? – Patsnap Synapse, accessed August 16, 2025, https://synapse.patsnap.com/blog/what-are-the-types-of-pharmaceutical-patents

- The Pharmaceutical Patent Playbook: Forging Competitive …, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/developing-a-comprehensive-drug-patent-strategy/

- A Business Professional’s Guide to Drug Patent Searching – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-basics-of-drug-patent-searching/

- What Is the Difference Between Composition and Method-of-Use Claims?, accessed August 16, 2025, https://synapse.patsnap.com/article/what-is-the-difference-between-composition-and-method-of-use-claims

- Types of Pharmaceutical Patents, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.obrienpatents.com/types-pharmaceutical-patents/

- Patent essentials | USPTO, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.uspto.gov/patents/basics/essentials

- How Drug Life-Cycle Management Patent Strategies May Impact Formulary Management, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.ajmc.com/view/a636-article

- Drug Patent Life: The Complete Guide to Pharmaceutical Patent …, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/how-long-do-drug-patents-last/

- How Long Does a Patent Last for Drugs? A Comprehensive Guide to Pharmaceutical Patent Duration – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/how-long-does-a-patent-last-for-drugs/

- Optimizing Your Drug Patent Strategy: A Comprehensive Guide for …, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/optimizing-your-drug-patent-strategy-a-comprehensive-guide-for-pharmaceutical-companies/

- Method of Use Patents – (Intro to Pharmacology) – Vocab, Definition, Explanations | Fiveable, accessed August 16, 2025, https://library.fiveable.me/key-terms/introduction-to-pharmacology/method-of-use-patents

- The value of method of use patent claims in protecting your therapeutic assets, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-value-of-method-of-use-patent-claims-in-protecting-your-therapeutic-assets/

- Patenting Repurposed Drugs – Patent Docs, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.patentdocs.org/2018/09/patenting-repurposed-drugs.html

- What is the difference between a composition claim and a method of use claim?, accessed August 16, 2025, https://wysebridge.com/what-is-the-difference-between-a-composition-claim-and-a-method-of-use-claim

- Method-of-Treatment Patents Increasing Value Risk – Outsourced Pharma, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.outsourcedpharma.com/doc/method-of-treatment-patents-increasing-value-risk-0001

- Pharmaceutical Patenting – D Young & Co, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.dyoung.com/en/knowledgebank/articles/pharmaceuticalpatenting0213

- The Role of AI in Drug Discovery: Accelerating the Pipeline | MRL …, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.mrlcg.com/resources/blog/the-role-of-ai-in-drug-discovery–accelerating-the-pipeline/

- AI-driven target identification and validation – AXXAM, accessed August 16, 2025, https://axxam.com/innovative-biology/target-identification-and-validation/

- AI approaches for the discovery and validation of drug targets – Cambridge University Press, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/cambridge-prisms-precision-medicine/article/ai-approaches-for-the-discovery-and-validation-of-drug-targets/24D84C83146B0348362A9A0EA8A9CF8C

- Therapeutic Target Identification & Validation with AI | Ardigen, accessed August 16, 2025, https://ardigen.com/target-identification/

- How Artificial Intelligence is Revolutionizing Drug Discovery – Petrie …, accessed August 16, 2025, https://petrieflom.law.harvard.edu/2023/03/20/how-artificial-intelligence-is-revolutionizing-drug-discovery/

- How artificial intelligence can power clinical development – McKinsey, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/life-sciences/our-insights/how-artificial-intelligence-can-power-clinical-development

- How AI is quietly changing drug manufacturability – Drug Target Review, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.drugtargetreview.com/article/181304/how-ai-is-quietly-changing-drug-manufacturability/

- Using generative AI, researchers design compounds that can kill drug-resistant bacteria, accessed August 16, 2025, https://news.mit.edu/2025/using-generative-ai-researchers-design-compounds-kill-drug-resistant-bacteria-0814

- survey of generative AI for de novo drug design: new frontiers in molecule and protein … – Oxford Academic, accessed August 16, 2025, https://academic.oup.com/bib/article/25/4/bbae338/7713723

- Deep generative molecular design reshapes drug discovery – PMC, accessed August 16, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9797947/

- Accelerating drug discovery with TamGen: A generative AI approach to target-aware molecule generation – Microsoft Research, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/research/blog/accelerating-drug-discovery-with-tamgen-a-generative-ai-approach-to-target-aware-molecule-generation/

- Predictive Analytics for Drug Efficacy: Revolutionizing R&D, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.amii.ca/use-cases/biotech-predictive-analytics-drug-efficacy

- Recent advances in AI-based toxicity prediction for drug discovery – Frontiers, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/chemistry/articles/10.3389/fchem.2025.1632046/full

- Artificial Intelligence-Driven Drug Toxicity Prediction: Advances, Challenges, and Future Directions – MDPI, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.mdpi.com/2305-6304/13/7/525

- Artificial Intelligence for Drug Toxicity and Safety – PMC – PubMed Central, accessed August 16, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6710127/

- Harnessing Artificial Intelligence for Drug Repurposing – Consult QD – Cleveland Clinic, accessed August 16, 2025, https://consultqd.clevelandclinic.org/harnessing-artificial-intelligence-for-drug-repurposing

- Top 6 Companies Using AI In Drug Discovery And Development – The Medical Futurist, accessed August 16, 2025, https://medicalfuturist.com/top-companies-using-a-i-in-drug-discovery-and-development/

- Navigating the USPTO’s AI inventorship guidance in AI-driven drug …, accessed August 16, 2025, https://academic.oup.com/jlb/article/12/2/lsaf014/8221411

- AI Meets Drug Discovery – But Who Gets the Patent …, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/ai-meets-drug-discovery-but-who-gets-the-patent/

- Navigating the USPTO’s AI inventorship guidance in AI-driven drug …, accessed August 16, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12317375/

- Patentability Risks Posed by AI in Drug Discovery | Insights – Ropes & Gray LLP, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.ropesgray.com/en/insights/alerts/2024/10/patentability-risks-posed-by-ai-in-drug-discovery

- 12 AI drug discovery companies you should know about in 2025, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.labiotech.eu/best-biotech/ai-drug-discovery-companies/

- The Future of AI in the Pharmaceutical Industry | Articles | Finnegan …, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.finnegan.com/en/insights/articles/the-future-of-ai-in-the-pharmaceutical-industry.html

- Navigating the Future: Ensuring Patentability for AI-Assisted …, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.finnegan.com/en/insights/articles/navigating-the-future-ensuring-patentability-for-ai-assisted-innovations-in-the-pharmaceutical-and-chemical-space.html

- How AI and Machine Learning are Forging the Next Frontier of …, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/how-ai-and-machine-learning-are-forging-the-next-frontier-of-pharmaceutical-ip-strategy/

- Top 5 Potential Implications of AI-Generated Prior Art on Patent Law | Sterne Kessler, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.sternekessler.com/news-insights/insights/top-5-potential-implications-of-ai-generated-prior-art-on-patent-law/

- Can AI Be An Inventor? The US, UK, EPO and German Approach | Mayer Brown – JD Supra, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.jdsupra.com/legalnews/can-ai-be-an-inventor-the-us-uk-epo-and-1004614/

- Key Inventorship Considerations in AI-assisted Drug Development | JD Supra, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.jdsupra.com/legalnews/key-inventorship-considerations-in-ai-6047492/

- Who Gets the Patent When AI Is the Inventor? – Goodwin, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.goodwinlaw.com/en/insights/publications/2023/09/insights-technology-aiml-who-gets-the-patent-when-ai

- Emerging Legal Terrain: IP Risks from AI’s Role in Drug Discovery – Fenwick, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.fenwick.com/insights/publications/emerging-legal-terrain-ip-risks-from-ais-role-in-drug-discovery

- How AI Inventorship Is Evolving In The UK, EU And US – Law360 – Mayer Brown, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.mayerbrown.com/-/media/files/perspectives-events/publications/2024/02/how-ai-inventorship-is-evolving-in-the-uk-eu-and-us–law360.pdf%3Frev=-1

- Inventorship Guidance for AI-Assisted Inventions – Federal Register, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2024/02/13/2024-02623/inventorship-guidance-for-ai-assisted-inventions

- Can AI Inventions Be Patented? The USPTO Speaks. | Insights …, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.ropesgray.com/en/insights/alerts/2024/02/can-ai-inventions-be-patented-the-uspto-speaks

- USPTO issues inventorship guidance and examples for AI-assisted inventions, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.uspto.gov/subscription-center/2024/uspto-issues-inventorship-guidance-and-examples-ai-assisted-inventions

- Unpacking AI-Assisted Drug Discovery Patents – Fenwick, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.fenwick.com/insights/publications/unpacking-ai-assisted-drug-discovery-patents

- Patenting Drugs Developed with Artificial Intelligence: Navigating …, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/patenting-drugs-developed-with-artificial-intelligence-navigating-the-legal-landscape/

- Navigating Inventorship in the Era of AI-Assisted Drug Discovery | MoFo Life Sciences, accessed August 16, 2025, https://lifesciences.mofo.com/topics/250304-navigating-inventorship

- Generative AI, drug discovery, and US patent law | DLA Piper, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.dlapiper.com/en-om/insights/publications/synthesis/2024/generative-ai-drug-discovery-and-us-patent-law

- Drug Patent Watch: Expertise in Patent Searching Helps Clients Mitigate Infringement Risks, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.geneonline.com/drug-patent-watch-expertise-in-patent-searching-helps-clients-mitigate-infringement-risks/

- Pharmaceutical patents and data exclusivity in an age of AI-driven drug discovery and development | Medicines Law & Policy, accessed August 16, 2025, https://medicineslawandpolicy.org/2025/04/pharmaceutical-patents-and-data-exclusivity-in-an-age-of-ai-driven-drug-discovery-and-development/

- REFORMING U.S. PATENT LAW TO ENABLE ACCESS TO ESSENTIAL MEDICINES IN THE ERA OF ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE – Scholarly Commons, accessed August 16, 2025, https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1339&context=njtip

- Inventing the Right Drug: Artificial Intelligence May Just be the Cure for an Antiquated Patent System, accessed August 16, 2025, https://digitalcommons.law.uga.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1500&context=jipl