Deconstructing the Middleman: Beyond the Textbook Definition

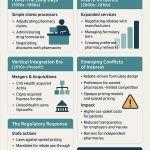

To truly grasp the PBM’s role, we must look past the simple definition of a “claims processor.” While their origins in the 1960s were indeed administrative—helping insurers manage the then-new concept of prescription drug coverage—their evolution has been nothing short of transformative. Today, PBMs are the central nervous system of the U.S. prescription drug market, strategic architects managing the pharmacy benefits for over 275 million Americans. They are not merely intermediaries; they are powerful gatekeepers.

Their client list is a who’s who of American healthcare payers: large self-insured employers, commercial health plans, labor unions, and massive government programs like Medicare Part D and managed Medicaid.1 For these clients, PBMs perform a suite of critical functions that go far beyond simple administration. They leverage their immense scale to negotiate drug prices directly with pharmaceutical manufacturers. They build and manage pharmacy networks, dictating the reimbursement rates paid to retail and mail-order pharmacies for dispensing medications. And, most critically, they design and manage drug formularies—the very lists that determine which medications are covered and accessible to patients.1

In theory, this consolidation of purchasing power is meant to drive down costs. By representing millions of patients, a PBM can demand significant discounts from drugmakers who are desperate for access to that patient base. However, as we will explore in exhaustive detail, the financial incentives embedded within this model have created a system rife with opacity, potential conflicts of interest, and outcomes that are now facing intense scrutiny from regulators, lawmakers, and the public alike.1 For investors, understanding the chasm between the PBM’s theoretical purpose and its practical, profit-driven reality is the first step toward making informed decisions in this space.

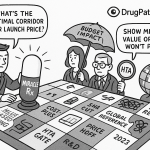

The Ecosystem of Influence: Mapping the Flow of Money and Services

Imagine the pharmaceutical supply chain not as a straight line, but as a complex web with the PBM sitting squarely at its center. Every other major player must, in some way, interact with and contract through the PBM, creating a system of mutual dependency that solidifies the PBM’s power. Let’s trace the critical connections and the flow of funds.

- Drug Manufacturers: This is perhaps the most contentious relationship. Manufacturers of brand-name drugs engage in high-stakes negotiations with PBMs. The prize? Favorable placement on the PBM’s formulary. To secure a spot on a “preferred” tier, which means lower out-of-pocket costs for patients and thus higher prescription volume, manufacturers pay substantial rebates and discounts to the PBM.1 This financial exchange is the lifeblood of the PBM business model.

- Payers (Health Plans & Employers): Payers are the PBM’s primary clients. They contract with PBMs to manage their prescription drug spending, hoping to contain the ever-rising costs of pharmaceuticals. In exchange for this service, payers provide PBMs with revenue through various mechanisms, which can include administrative fees, a share of the negotiated rebates, or through pricing models like “spread pricing,” which we will dissect shortly.1 The promise to the payer is that the PBM’s negotiating prowess will result in net savings that far exceed their fees.

- Pharmacies: To dispense medications to the millions of patients covered by a PBM’s clients, pharmacies—from large national chains to small independent drugstores—must join the PBM’s network. This gives the PBM the power to set the terms of reimbursement, including the amount the pharmacy is paid for the drug itself and any associated dispensing fee. This leverage has become a major source of friction, with independent pharmacies in particular arguing that PBM reimbursement rates are often below their own acquisition costs, squeezing their margins to the breaking point.

- Patients: While patients do not contract directly with PBMs, they feel their influence at the pharmacy counter every day. A PBM’s formulary design—specifically its use of tiered co-pays—directly shapes a patient’s out-of-pocket costs and can steer them toward or away from certain medications.5 Utilization management tools like prior authorization (requiring insurer approval before a drug is covered) and step therapy (requiring a patient to try and fail on a cheaper drug first) are also implemented by PBMs, directly impacting a patient’s access to the therapy their doctor prescribed.

This intricate network of dependencies is the source of the PBM’s immense power. It didn’t happen by accident. The system evolved from a simple administrative need into a strategic one. As drug spending became a larger and more volatile portion of healthcare costs, payers became more desperate for a partner who could control it. PBMs stepped into that role by aggregating the purchasing power of millions of beneficiaries. This aggregation created leverage. Manufacturers, needing access to those patients, had to negotiate with PBMs and pay rebates. Pharmacies, needing to serve those same patients, had to accept the PBM’s network terms. And payers, needing to control costs, became increasingly reliant on the PBM’s services. This dependency loop places the PBM at the center of the pharmaceutical universe, and it is this concentration of power that is the foundational concept for understanding every controversy and investment risk that follows.

Unpacking the Black Box: How PBMs Generate Billions

For investors, following the money is paramount. In the world of PBMs, this can be a daunting task, as their revenue streams are often intentionally complex and opaque. However, by breaking down their two primary business models and understanding the mechanics of the rebate system, we can begin to see how billions of dollars are generated and why the entire system is under such intense pressure to change.

The Great Divide: Spread Pricing vs. Pass-Through Models

At its core, the choice of a PBM pricing model is a decision between opacity and transparency. A plan sponsor—be it an employer or a health plan—must choose which model best aligns with its goals and its tolerance for risk. For investors, understanding these models is critical because the industry’s forced march toward transparency is a direct threat to the most lucrative, and most controversial, of these arrangements.

The Traditional (Spread) Pricing Model

The traditional model, often called “spread pricing,” is the PBM industry’s original sin in the eyes of its critics. The mechanics are deceptively simple: the PBM negotiates one price with the pharmacy that dispenses a drug and a second, higher price with the plan sponsor who pays for that drug. The difference between these two prices is the “spread,” which the PBM retains as its primary source of profit.7

For example, a PBM might reimburse a pharmacy $2.00 for a generic medication. It then turns around and bills the client’s health plan $2.50 for that same prescription. The $0.50 difference is the PBM’s spread, its revenue for that transaction. In this model, there are typically no per-claim administrative fees, and the PBM often promises the client more aggressive discounts and rebate guarantees.

Why would any client agree to this? The allure is in the aggressive upfront pricing. The PBM can offer what appear to be very attractive terms because it knows it will be generating revenue from the spread throughout the year. However, this is unequivocally the least transparent model. The client often has no visibility into what the PBM is actually paying the pharmacy, making it impossible to know the true size of the spread. This opacity has led to stunning examples of overpayment. State-sponsored investigations into their Medicaid programs have uncovered massive spreads, with PBMs overcharging Michigan by at least $64 million and Maryland by $72 million annually through this practice alone.

For an investor, a PBM or a health plan heavily reliant on a spread pricing model carries significant regulatory risk. As states and the federal government move to ban this practice, particularly in government programs, this revenue stream is in jeopardy.1

The Pass-Through (Transparent) Pricing Model

In response to growing criticism and market demand for clarity, the “pass-through” or “transparent” model has gained prominence. Here, the price that the PBM pays the pharmacy is passed through directly to the plan sponsor without any markup. The PBM’s revenue is derived from a flat, transparent, and pre-negotiated administrative fee for each claim processed.7

The primary benefit for the plan sponsor is clear: visibility. They can see the actual cost of the drug and the PBM’s administrative fee as two separate line items, allowing for much clearer financial analysis and auditing. This model gives the plan sponsor greater control and ensures that any additional discounts negotiated by the PBM are returned to the plan, not captured as spread.

However, this model is not without its trade-offs. The upfront network pharmacy discounts may be less aggressive than those offered in a traditional model. Furthermore, investors must be aware of the nuances. “Pass-through” pricing is often limited to retail pharmacy claims; many PBMs still use a spread model for their own, highly profitable mail-order and specialty pharmacy businesses. Additionally, while the per-claim fee is transparent, PBMs may layer in other fees, such as rebate administration fees or network audit fees, that can add complexity back into the equation.

The industry-wide shift toward offering more transparent models is not born of altruism. It is a direct, defensive maneuver in response to intense regulatory and client pressure. The largest PBMs, including CVS and Cigna, have recently launched their own branded “transparent” pricing options.10 For investors, this signals a recognition that the old way of doing business is no longer tenable. The key question now is whether these new models are truly transparent or simply a more sophisticated form of financial engineering.

| Feature | Traditional (Spread) Pricing | Pass-Through (Transparent) Pricing |

| Primary Revenue Source | The “spread” between what the PBM bills the client and pays the pharmacy.7 | Flat, per-claim administrative fee.7 |

| Transparency Level | Opaque. Client has little to no visibility into the actual drug cost or PBM’s margin. | Transparent. Client sees drug cost and administrative fee as separate line items. |

| Key Incentive | Maximize the price differential (the spread) on each transaction. | Process claims efficiently and demonstrate value through other services. |

| Typical Client Profile | Historically common, especially with larger PBMs. May appeal to clients focused on lowest guaranteed price, willing to trade transparency for it. | Clients prioritizing transparency, cost predictability, and control over their pharmacy benefit. |

| Regulatory Risk | High. Spread pricing is a primary target of state and federal reform efforts, with many states moving to ban it, especially in Medicaid.9 | Low. This model aligns with the direction of proposed regulations that favor transparency and flat-fee compensation. |

The Rebate Labyrinth: The Engine of the Gross-to-Net Bubble

If spread pricing is the PBM’s most controversial practice, the rebate system is its most powerful and misunderstood engine. It is the primary driver of what the industry has termed the “gross-to-net bubble”—a phenomenon that distorts the entire pharmaceutical market and has profound implications for manufacturers, payers, and patients.

Defining the Gross-to-Net Bubble

The gross-to-net bubble describes the enormous and ever-widening gap between a brand-name drug’s official list price—often the Wholesale Acquisition Cost, or WAC—and the actual net price that the manufacturer receives after paying all rebates, discounts, and fees to the PBMs and other entities in the supply chain.14

The scale of this bubble is breathtaking. Analysis has consistently shown that, on average, brand-name drugs are sold for roughly half of their list price. The total value of these gross-to-net reductions for brand-name drugs was estimated to be a staggering $175 billion in 2019, a figure that had doubled in the preceding six years. This means that for every dollar of list price revenue reported in the headlines, manufacturers may only be seeing fifty cents in actual net revenue.

This chasm between list and net price is the central battleground of the drug pricing debate. It allows PBMs and insurers to claim they are securing massive “discounts” while list prices continue to climb. It allows manufacturers to blame PBMs for demanding ever-larger rebates. And it leaves patients, whose cost-sharing is often tied to the inflated list price, caught in the middle, paying more even as the net price of their medication may be falling.

The Perverse Incentive: Why High List Prices Can Be More Profitable

Herein lies the core distortion of the modern pharmaceutical market. Because rebates are typically negotiated as a percentage of a drug’s list price, a PBM can have a direct financial incentive to favor a drug with a high list price and a large rebate over a competing drug with a lower list price and a smaller rebate, even if the latter has a lower net cost.1

Let’s illustrate with a simplified example. Imagine two competing drugs:

- Drug A: List Price $600, Rebate 50% ($300). Net Cost to Payer: $300.

- Drug B: List Price $400, Rebate 20% ($80). Net Cost to Payer: $320.

In this scenario, Drug A has the lower net cost and would seem to be the better value. But now, let’s consider a third option:

- Drug C: List Price $1,000, Rebate 65% ($650). Net Cost to Payer: $350.

If the PBM retains a portion of the rebate, say 20%, its revenue from each option would be:

- Drug A: 20% of $300 rebate = $60

- Drug B: 20% of $80 rebate = $16

- Drug C: 20% of $650 rebate = $130

Suddenly, the PBM has a powerful incentive to place Drug C, the one with the highest list price and the largest rebate, in the most favorable position on its formulary, despite it having the highest net cost to the payer. This perverse incentive is not theoretical; it is a fundamental driver of formulary design and contributes directly to the inflation of list prices across the industry.

The most poignant example of this dynamic is insulin. For years, the list prices of blockbuster insulins like Humalog skyrocketed. Yet, during that same period, the net price manufacturers received actually declined. An analysis of Eli Lilly’s Humalog showed that between 2015 and 2019, its list price rose 27%, while its net price fell by 10%. The difference was absorbed by ever-growing rebates and discounts, which for a single patient could total more than $5,000 per year. Patients with high-deductible plans or coinsurance, however, were exposed to that soaring list price, leading to the affordability crisis that has dominated headlines.

The Mechanics of Rebate Negotiation

Rebates are not arbitrary. They are the result of intense, behind-the-scenes negotiations between manufacturers and PBMs, and they are directly tied to two key factors: formulary placement and drug utilization. A manufacturer offers a rebate as a direct payment to the PBM in exchange for placing its drug on a preferred formulary tier. This preferred status means a lower co-pay for the patient, which in turn drives prescriber behavior and increases the volume of prescriptions filled—the drug’s utilization.

The size of the rebate is highly dependent on market competition. In a therapeutic class with many competing brand-name drugs (e.g., anti-inflammatory agents), manufacturers must offer very large rebates to win preferred status. A 2016 analysis of Medicare Part D found that in classes with brand competition, the average rebate was 39% of the gross drug cost. Conversely, in “protected classes” where Medicare rules mandate that most drugs must be covered (e.g., antidepressants, antipsychotics), there is less competition and thus less leverage for the PBM. In these classes, the average rebate was only 14%. It is also important for investors to remember that generic drugs, which make up the vast majority of prescriptions, typically do not offer rebates, as their low price is their primary value proposition.

The Power of Aggregation: PBM-Owned GPOs

Just when you think the financial engineering can’t get any more complex, we arrive at the PBM-owned Group Purchasing Organization (GPO). This is a critical, yet often overlooked, piece of the puzzle that allows the largest PBMs to further consolidate their power and obscure their revenue streams.

The “Big 3” PBMs have each established their own affiliated GPOs:

- Ascent Health Solutions (owned by Cigna, parent of Express Scripts)

- Emisar Pharma Services (owned by UnitedHealth Group, parent of Optum Rx)

- Zinc Health Services (owned by CVS Health, parent of Caremark)

Ostensibly, the function of these GPOs is to handle the rebate negotiations with manufacturers. By aggregating the purchasing volume of the PBM and all its clients, the GPO can present a united front to drugmakers, extracting the maximum possible rebate.

However, the GPO structure also serves another crucial purpose. Even in a “pass-through” rebate model, where the PBM contractually agrees to pass 100% of the negotiated rebate back to the plan sponsor, the GPO can introduce another layer of fees. The manufacturer pays the rebate to the GPO, which then retains a portion as an “administrative and participation fee” before passing the remainder to the PBM, which in turn passes it to the client. Because the GPO is a legally separate (though wholly owned) entity, the PBM can claim it is passing through 100% of the rebate it receives from the GPO, while a significant portion of the original rebate from the manufacturer has already been siphoned off.

This structure is a brilliant piece of financial architecture. It allows the vertically integrated parent company to capture a portion of the rebate stream while maintaining the appearance of transparency in its PBM contracts. For investors, the existence of these GPOs is a massive red flag. It indicates that even as PBMs roll out new “transparent” pricing models to preempt regulation, the underlying incentive to maximize the gross-to-net bubble remains firmly in place. Until regulators look through the corporate veil and scrutinize the flow of funds between the manufacturer, the GPO, and the PBM, a significant portion of the rebate dollars will likely remain hidden from view. The GPO is the final, and perhaps most opaque, layer of the PBM’s black box.

The Architects of Access: How Formularies Dictate Market Winners and Losers

If rebates are the fuel of the PBM engine, then the formulary is its steering wheel. A drug’s placement on this meticulously crafted list of covered medications is the single most important determinant of its market success after FDA approval. For investors in pharmaceutical and biotech companies, understanding the art and science of formulary design is not just an academic exercise; it is a prerequisite for assessing a drug’s commercial viability. A blockbuster drug that is relegated to a non-preferred tier or excluded from a formulary altogether can fail to meet sales expectations, with devastating consequences for a company’s stock price.

Building the Formulary: The Role of P&T Committees

On the surface, the process of building a drug formulary is a rational, evidence-based endeavor. A PBM convenes a Pharmacy & Therapeutics (P&T) Committee, a panel of independent physicians, pharmacists, and other healthcare experts.6 This committee’s stated mission is to review the clinical merits of new and existing drugs, evaluating them based on safety, efficacy, and the latest clinical guidelines and FDA-approved information. They are tasked with ensuring that the formulary provides patients with access to a range of effective treatments for various diseases.

However, this clinical review is only one side of the equation. The PBM’s final formulary is a hybrid document, a marriage of clinical judgment and hard-nosed financial negotiation. The P&T committee may determine that three different drugs in a class are clinically equivalent. It is then up to the PBM’s business negotiators to determine which of those three manufacturers is willing to offer the largest rebate in exchange for being designated the “preferred” agent. This introduces the central tension at the heart of every formulary decision: the constant balancing act between what is clinically optimal and what is financially advantageous for the PBM and its client.

The Tiers of Control: A System of Financial Incentives

The primary tool that PBMs use to translate their rebate negotiations into tangible market share for a preferred drug is the formulary tiering system. This structure is a powerful instrument of behavioral economics, designed to guide the choices of both patients and prescribers through a series of carefully calibrated financial incentives and disincentives.5 While the exact number of tiers and their names can vary, a typical structure looks like this :

- Tier 1: Preferred Generics. This is the lowest-cost tier, with the smallest patient co-payment. It is almost exclusively populated by generic drugs, which are the most cost-effective options available.

- Tier 2: Preferred Brands. This tier is for brand-name drugs that the PBM wants to encourage. Patients will pay a higher co-payment than for generics, but a lower one than for non-preferred brands. This is where you will find the blockbuster drugs whose manufacturers have paid a hefty rebate to secure this coveted status.

- Tier 3: Non-Preferred Brands. Here lie the brand-name drugs that are still covered by the plan but are actively discouraged. The patient co-payment is significantly higher, often creating a substantial financial barrier. These are typically the competitors to the drugs in Tier 2, or drugs from manufacturers who were unwilling to offer a competitive rebate.

- Specialty Tier. This is a separate and distinct tier reserved for very high-cost drugs used to treat complex or chronic conditions like cancer, rheumatoid arthritis, or multiple sclerosis. Instead of a flat co-payment, patients on this tier are often required to pay a percentage of the drug’s cost, known as coinsurance. Given the astronomical list prices of these drugs, even a 20-30% coinsurance can amount to thousands of dollars per month for the patient.

- Non-Formulary (Excluded). This is the ultimate penalty box. A drug placed on the exclusion list is not covered by the insurance plan at all. If a patient wants that specific medication, they must pay 100% of its cost out-of-pocket.

This tiered structure effectively allows the PBM to create a “path of least resistance” for prescribers and patients, guiding them toward the drugs that are most profitable for the PBM’s business model.

From Patent to Placement: Using Data to Predict Formulary Success

For a pharmaceutical company, the journey from patent filing to a favorable formulary placement is a long and arduous one, and its intellectual property (IP) portfolio is one of its most critical assets in this fight. A strong and well-managed patent portfolio is the foundation of a drug’s negotiating leverage with a PBM.22

The most valuable patent is typically the “composition of matter” patent, which covers the active drug molecule itself. This provides the longest and strongest period of market exclusivity. However, manufacturers strategically build a “patent thicket” around their products, filing additional patents for new formulations (e.g., an extended-release version), new methods of use (i.e., treating a different disease), and manufacturing processes. This web of patents can make it more difficult and costly for generic or biosimilar competitors to enter the market, even after the primary patent expires, thus prolonging the brand’s revenue stream and its ability to pay rebates.

This is where sophisticated data analysis becomes a powerful strategic tool for both payers and investors. The ability to accurately forecast when a blockbuster brand will lose its exclusivity and face low-cost competition is paramount. A payer armed with this knowledge can refuse to pay exorbitant prices or large rebates for a drug in the final years of its patent life, knowing that a cheap alternative is on the horizon.

This is precisely the value proposition of specialized intelligence services like DrugPatentWatch. By providing a comprehensive, integrated database of drug patents, patent litigation, clinical trial data, and biosimilar development pipelines, DrugPatentWatch empowers stakeholders to look over the horizon.22 An investor can use this data to assess the durability of a pharmaceutical company’s revenue streams, identifying which products are protected by a robust patent fortress and which are vulnerable to an impending patent cliff. A PBM or health plan can use this same intelligence to inform its formulary strategy, preparing to shift utilization to generics or biosimilars the moment they become available, thereby maximizing cost savings. In an industry defined by information asymmetry, access to timely and accurate patent data can provide a decisive competitive edge.

The Consequences of Exclusion and Non-Equivalent Switches

The power wielded by PBMs through their formulary decisions is not just financial; it has profound real-world consequences for patient health. When a PBM decides to exclude a drug from its formulary, it can erect a nearly insurmountable barrier to access for the patients who may need that specific therapy.

The rationale for these exclusions is always cost savings. Case studies have demonstrated the immense financial impact of shifting utilization to formulary-preferred drugs. One analysis of a health plan found that by increasing the use of its recommended drugs, it could realize potential cost savings of over $5 million in a single year across several therapeutic categories, including antidepressants and proton pump inhibitors. This illustrates the powerful financial incentive for PBMs to be aggressive with their formulary management.

However, this aggression can come at a clinical cost. Research has shown that PBM-mandated formulary exclusions can have a staggering impact, with one study estimating that specific exclusions could adversely affect up to 1 million patients with atrial fibrillation and 900,000 with migraines. The problem is often compounded when the PBM mandates a switch to a “preferred” alternative that is not therapeutically equivalent to the excluded drug. A 2022 study found that almost half of all exclusions mandated by Express Scripts, the nation’s second-largest PBM at the time, were for non-equivalent switches. For a patient who is stable on a particular medication, a forced switch to a different, albeit chemically related, drug can lead to new side effects, a loss of efficacy, or treatment discontinuation altogether, ultimately resulting in poorer health outcomes and potentially higher downstream medical costs.

This dynamic reveals the sharpest edge of the PBM power debate. While their actions are framed in the language of cost-effectiveness and value, the consequences can be deeply personal and clinically significant for patients. For investors, this represents a reputational and regulatory risk. The more stories that emerge of patients being harmed by restrictive formulary decisions, the greater the public and political pressure will be to rein in the PBMs’ authority to make these unilateral coverage determinations.

An Oligopoly in Action: The Dominance of the “Big 3”

The modern PBM market is not a landscape of robust competition. It is an oligopoly, a market structure dominated by a small number of large, powerful firms. This concentration of power has been building for years through a wave of mergers and acquisitions, and it has created a formidable barrier to entry for smaller players and given the dominant firms immense leverage over every other stakeholder in the pharmaceutical ecosystem. For investors, understanding the scale of this dominance and the strategic implications of the PBMs’ vertically integrated structures is essential for assessing the stability and risks of the entire healthcare sector.

Sizing the Behemoths: Market Share and Concentration

The numbers speak for themselves. For 2024, a staggering 80% of all prescription claims in the United States were processed by just three companies 18:

- Express Scripts (owned by The Cigna Group): 30% market share

- CVS Caremark (owned by CVS Health): 27% market share

- Optum Rx (owned by UnitedHealth Group): 23% market share

The remaining 20% of the market is fragmented among a handful of smaller PBMs, like Humana and MedImpact, and cash-paying customers. This level of concentration, which has been steadily increasing, gives the “Big 3” near-total control over the market. It leaves drug manufacturers, pharmacies, and even large health plans with very few alternatives if they want to participate in the U.S. healthcare system.

The dynamics within this oligopoly are also telling. The 2024 market share figures represent a significant shake-up, with Express Scripts leapfrogging the long-time leader, CVS Caremark. This shift was not the result of a gradual competitive process; it was largely driven by a single, massive contract win. In January 2024, Express Scripts took over the management of pharmacy benefits for approximately 20 million members of Centene, a contract previously held by CVS Caremark.18 This single event caused Express Scripts’ claims volume to surge by 40% and CVS Caremark’s to fall by over 18%. This highlights the high-stakes, winner-take-all nature of the PBM business, where the gain or loss of a single major client can dramatically alter the competitive landscape.

The Vertically Integrated Fortress

The market share figures alone do not fully capture the power of the “Big 3.” Their true strategic advantage lies in their position within vast, vertically integrated healthcare conglomerates. These PBMs are not standalone entities; they are the lucrative pharmacy service arms of corporations that also own 2:

- One of the nation’s largest health insurers: Cigna (Express Scripts), CVS Health (Aetna), and UnitedHealth Group (UnitedHealthcare).

- The largest specialty pharmacies in the country: These pharmacies dispense the most expensive and profitable drugs on the market.

- Retail and mail-order pharmacy operations: CVS owns the largest retail pharmacy chain in the country.

- Physician groups and clinical care providers: CVS’s acquisition of Oak Street Health and UnitedHealth’s massive Optum Health division are prime examples of this expansion into direct patient care.

This integration creates a powerful, self-reinforcing ecosystem. The health insurer can direct its members to use its own PBM. The PBM can then design formularies that steer patients to fill their prescriptions, especially high-cost specialty drugs, at its own affiliated specialty or mail-order pharmacy. The company captures revenue at every step of this process: the insurance premium, the PBM’s administrative fee or spread, and the pharmacy’s dispensing margin.

This structure provides a formidable competitive moat, but it is also the primary focus of antitrust regulators. The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) is investigating whether this vertical integration enables anticompetitive behavior, such as using patient data from the insurance side to steer them to the pharmacy side, ultimately harming independent competitors and increasing costs.30 The very fortress that protects the “Big 3’s” profits is also their greatest regulatory vulnerability.

A Financial Deep Dive for Investors

To put the scale of these operations into perspective, let’s look at the publicly reported financial results for the segments that house these PBMs. While the accounting can be complex, with significant inter-company revenue, these figures give investors a clear sense of the sheer size and economic importance of these units to their parent corporations.

- CVS Health (Health Services Segment): This segment, which is dominated by the CVS Caremark PBM, is a financial juggernaut. In 2023, it generated a massive $186.8 billion in revenue, processing 2.3 billion prescriptions. This single segment now accounts for more than half of CVS Health’s total corporate revenue.

- The Cigna Group (Evernorth Segment): Evernorth, the health services division that includes Express Scripts, is the primary growth engine for Cigna. In 2023, its revenue grew 9% to $153.5 billion. This growth was fueled by strong performance in its specialty pharmacy and the onboarding of major new clients like Centene.

- UnitedHealth Group (Optum Rx Segment): The PBM arm of the sprawling Optum empire is similarly massive. For 2025, UnitedHealth Group projects that Optum Rx will generate approximately $151 billion in revenue and between $6.0 and $6.1 billion in operating earnings.32

These are not small business units; they are Fortune 50-sized enterprises operating within even larger parent companies. However, investors must look beyond the top-line revenue and search for signs of stress. In its SEC filings, for example, CVS Health has explicitly acknowledged that growing “marketplace dynamics and regulatory changes” are pressuring its ability to retain rebates and use spread pricing. This is a direct admission from the company that its core, historical profit drivers are under threat. For an investor, tracking these disclosures and the outcomes of major contract negotiations is crucial for understanding the future earnings potential of these healthcare giants.

| PBM | Parent Company | 2024 Market Share | 2023 PBM-Segment Revenue |

| Express Scripts | The Cigna Group | 30% | $153.5 billion (Evernorth) |

| CVS Caremark | CVS Health | 27% | $186.8 billion (Health Services) |

| Optum Rx | UnitedHealth Group | 23% | $133.2 billion (2024 proj. ~$151B) |

| Total “Big 3” | 80% | ~$473.5 billion |

The Regulatory Gauntlet: A Rising Tide of Scrutiny

For decades, PBMs operated in the relative shadows of the healthcare industry, their complex business practices poorly understood by the public and largely ignored by regulators. That era is definitively over. The PBM industry is now facing an unprecedented wave of scrutiny from all corners, representing what is arguably the most significant existential threat to its business model in its history. For investors, the regulatory and legislative landscape is no longer a background consideration; it is a primary driver of risk and a potential catalyst for a fundamental reordering of the entire pharmaceutical market.

The FTC Unleashes: Key Findings from the PBM Investigations

The sharpest spear in the regulatory assault is being wielded by the Federal Trade Commission (FTC). In 2022, the agency launched a sweeping investigation into the business practices of the six largest PBMs, using its authority to demand a vast trove of internal data and documents.2 The interim reports released from this ongoing investigation have sent shockwaves through the industry, providing concrete evidence for many of the long-standing criticisms leveled against PBMs.

The FTC’s key allegations, detailed in its interim staff reports from July 2024 and January 2025, paint a damning picture of a market distorted by anticompetitive tactics:

- Massive Markups on Specialty Generics: The FTC’s analysis found that the “Big 3” PBMs systematically marked up the prices of dozens of crucial specialty generic drugs—including treatments for cancer and HIV—by hundreds or even thousands of percent when dispensed at their own affiliated pharmacies. These markups allowed the PBMs and their pharmacies to generate more than $7.3 billion in revenue in excess of the drugs’ estimated acquisition costs between 2017 and 2022.34

- Discriminatory Reimbursement and Patient Steering: The investigation revealed that PBMs consistently reimbursed their own affiliated pharmacies at significantly higher rates than they paid to unaffiliated, independent pharmacies for the exact same drugs.34 This practice, combined with formulary and network designs that create financial incentives or outright requirements for patients to use PBM-owned pharmacies, effectively steers the most profitable prescriptions away from independent competitors and into the PBM’s vertically integrated system.30

- Forcing Unfavorable Contracts: The FTC asserts that the immense market power of the “Big 3” leaves independent pharmacies with little choice but to accept take-it-or-leave-it contracts with onerous and unfavorable terms. Refusing to sign means losing access to the vast majority of insured patients in their area, a decision that would be a death sentence for most small businesses.

The FTC has signaled that its investigation is far from over and has announced its intention to sue the “Big 3” PBMs for their unfair negotiating tactics. For investors in the parent companies—CVS, Cigna, and UnitedHealth Group—this represents a significant and unquantifiable legal risk, with the potential for massive fines, forced divestitures, and court-ordered changes to their core business practices.

| Allegation | FTC Finding/Evidence | Implication for Investors |

| Inflated Specialty Generic Pricing | The “Big 3” PBMs marked up prices by hundreds or thousands of percent at their own pharmacies, generating over $7.3 billion in excess revenue on specialty generics from 2017-2022. | This profit center is now under direct threat. Regulatory action could force PBMs to price drugs based on acquisition cost plus a reasonable fee, wiping out billions in high-margin revenue. |

| Patient Steering | PBMs use formulary/network design and exclusivity provisions to steer patients, especially those on high-profit specialty drugs, to their own affiliated pharmacies.30 | This is a core tenet of the vertical integration strategy. A ban on patient steering would undermine the synergy between the PBM and pharmacy segments, potentially reducing the value of the integrated model. |

| Discriminatory Reimbursement | PBMs were found to reimburse their own pharmacies at significantly higher rates than unaffiliated pharmacies for the same drugs.34 | This practice is a primary driver of independent pharmacy closures. Mandating fair and equal reimbursement rates would level the playing field but would also compress the margins of PBM-owned pharmacies. |

| Unfair Contract Terms | PBMs leverage their market power to force smaller pharmacies into take-it-or-leave-it contracts with unfavorable terms, such as retroactive fees and opaque pricing metrics. | Legislation and legal action could standardize PBM-pharmacy contracts, increasing predictability for pharmacies but reducing the PBMs’ ability to extract profits through complex and opaque contract terms. |

The Bipartisan Onslaught: PBM Reform in Congress and the States

The FTC’s investigation is running parallel to a rare and powerful wave of bipartisan legislative action aimed at reining in PBMs. The issue has united Democrats and Republicans who see PBM practices as a key driver of high drug costs and a threat to small businesses in their districts.

At the Federal Level:

Congress is actively considering multiple pieces of legislation, such as the PBM Reform Act, that target the industry’s core business practices. The central tenets of these federal reform efforts include:

- Banning Spread Pricing: A primary goal is to prohibit the use of spread pricing, at least within government programs like Medicaid and Medicare, forcing a move to a more transparent reimbursement system.

- Delinking PBM Compensation from List Price: This is perhaps the most revolutionary proposal. It would prohibit PBMs from being compensated based on a percentage of a drug’s list price or the rebate they negotiate. Instead, they would be paid a flat, “bona fide service fee” for their administrative work.1 This would sever the perverse incentive to favor high-list-price drugs. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) has estimated that delinking could save taxpayers over $1 billion over ten years.9

- Mandating Transparency: The bills would require PBMs to provide regular, detailed reports to employers and health plans on drug spending, the rebates they receive, and the rationale behind their formulary decisions.

At the State Level:

The real momentum for reform has been at the state level, with 2025 being dubbed “the year of PBM reform”. Frustrated by federal inaction, states have been aggressively passing their own laws to regulate the industry. Since 2023, at least 35 states have enacted one or more PBM reform bills. The approaches vary, but they often include similar themes:

- Iowa passed a sweeping law that mandates pass-through pricing, requires that 100% of rebates be passed through to health plans, and bans PBMs from steering patients to their own mail-order pharmacies.

- Colorado enacted legislation that bans PBM reimbursement practices tied to drug prices and requires that pharmacies be reimbursed at a rate at or above the National Average Drug Acquisition Cost (NADAC) plus a reasonable professional dispensing fee.

- Indiana passed a comprehensive bill that establishes fair pharmacy network requirements, imposes new reporting requirements on PBMs, and sets a reimbursement floor to ensure pharmacies are paid fairly.

This patchwork of state laws creates a complex and challenging operating environment for the national PBMs. For investors, this two-pronged assault—from the FTC and federal lawmakers on one side, and from a growing chorus of state legislatures on the other—represents a fundamental risk to the PBM business model. The industry is now engaged in a massive lobbying and public relations effort to fend off these reforms , while simultaneously launching new “transparent” business models in an attempt to prove that a market-based solution is preferable to a government-mandated one. The outcome of this battle will determine the profitability and structure of the PBM industry for the next decade.

Case Studies: Where Theory Meets Market Reality

The concepts of rebate incentives, formulary power, and market concentration can seem abstract. To truly understand their impact, we must examine how they play out in the real world. The following case studies provide a granular look at how the PBM power nexus affects drug competition, healthcare costs, and the viability of small businesses. These are not isolated incidents; they are tangible manifestations of the systemic forces that investors must understand to navigate this sector.

The Humira Biosimilar Test: A Failure of Competition?

For years, the healthcare industry eagerly awaited the arrival of biosimilar competitors to AbbVie’s Humira, the best-selling drug in the world and a behemoth that accounted for $4.7 billion in Medicare spending alone in 2021. The launch of the first Humira biosimilars in 2023 was supposed to be a landmark event, a definitive test of whether biosimilar competition could finally break the back of high biologic drug costs.

The result, so far, has been a profound disappointment for advocates of a free-market solution. An analysis of Medicare Part D formularies for 2024 revealed a startling reality: while the original brand-name Humira enjoyed nearly universal coverage, appearing on 99% of plans, only about half of all plans covered any biosimilar alternative.

The reason for this lackluster adoption lies squarely in the PBM-driven rebate system. The analysis uncovered a crucial, counterintuitive fact: higher-priced versions of biosimilars received better formulary coverage than their identical, lower-list-price counterparts. For example, Sandoz launched two versions of its biosimilar, Hyrimoz: a high-list-price version with a large potential rebate, and an unbranded, low-list-price version with a small rebate. The high-priced version was covered by more than double the number of Medicare plans (26.8% vs. 13.0%). This is a smoking gun, a clear indication that PBM formulary decisions were being driven by the size of the rebate they could extract, not by the lowest net cost for the healthcare system.

The influence of a single PBM’s decision can be immense. In April 2024, CVS Caremark made the bold move to remove brand-name Humira from its main commercial formulary, designating a biosimilar as the preferred option. This single action caused a dramatic spike in patients switching to the biosimilar. However, the data also reveals a troubling counter-trend: a significant “switch-back” rate. Roughly 13% of patients who were moved to a biosimilar ended up switching back to the original Humira, with nearly 40% of those switch-backs occurring within the first 30 days. This suggests potential issues with patient acceptance, clinical management, or perhaps simply the sheer market power and familiarity of the original brand.

For investors, the Humira case study is a critical lesson. The mere existence of a cheaper alternative does not guarantee its success. A budget impact model showed that rapid conversion to Humira biosimilars could save a health plan with one million members nearly $29 million over three years. Yet, the PBM-controlled formulary system, with its addiction to high rebates, has so far blunted this potential, proving that in the modern pharmaceutical market, access is not granted by the FDA, but purchased from the PBM.

The Zytiga Generic Saga: Billions Lost to Delay

The story of Janssen’s prostate cancer drug, Zytiga (abiraterone), is a powerful illustration of how pharmaceutical company patent strategies and PBM formulary control can conspire to delay cost savings for years, at a tremendous cost to the healthcare system.

Zytiga’s primary patent was originally set to expire in late 2016. However, through a series of patent extension strategies and litigation—a practice often referred to as “evergreening” or building a “patent thicket”—the manufacturer was able to fend off generic competition until late 2020.

The financial impact of this four-year delay was staggering. Investigators estimated that it allowed Janssen to generate an additional $2.05 billion in sales for Zytiga that would have otherwise been lost to low-cost generics. The moment generics finally entered the market, the brand’s dominance collapsed. Zytiga’s market share plummeted to just 14%, and the total monthly net sales for the abiraterone molecule fell by a breathtaking 85%.

This case also exposed the friction that can arise between PBMs and their own clients. Blue Shield of California (BSC), a major insurer, publicly expressed its frustration when its PBM, CVS Caremark, was reluctant to cover a newly available, cheaper generic version of Zytiga on its formulary. This dispute was a key catalyst that pushed BSC to announce it was moving away from CVS Caremark and building its own, more transparent pharmacy care model with a consortium of other partners.

The Zytiga saga provides two crucial takeaways for investors. First, it quantifies the immense value of patent life extension strategies for manufacturers and the corresponding cost to the system. Second, it demonstrates that even large, sophisticated payers are growing tired of a PBM system that appears to prioritize its own rebate-driven revenue over the client’s goal of achieving the lowest possible net cost. The BSC defection is a canary in the coal mine, signaling a potential future where large payers may choose to “unbundle” PBM services or partner with smaller, more transparent players, posing a direct threat to the integrated model of the “Big 3.”

The Independent Pharmacy Squeeze: Testimony from the Trenches

The battle over PBM practices is not just a high-level corporate dispute; it has devastating consequences for small businesses across America. The testimony of independent pharmacy owners before Congress provides a raw, ground-level view of the impact of the PBMs’ immense market power.

During a hearing of the House Oversight Committee, Kevin Duane, an independent pharmacist from Florida, explained in stark terms how PBM practices had impacted his business and his patients. He testified that he was no longer able to serve military families covered by Tricare because the program’s PBM, Express Scripts, effectively forces those beneficiaries to use either a PBM-owned mail-order pharmacy or specific pharmacies located on military bases. This practice, known as patient steering, cuts local pharmacies out of the equation, harming their business and reducing access for patients who may prefer their local, independent pharmacist.

This is not an isolated anecdote. The committee’s investigation concluded that the “Big 3” PBMs systematically use their integrated structure to engage in anticompetitive behavior. They are accused of reimbursing independent pharmacies at rates that are often below the pharmacy’s own cost to acquire the drug, while simultaneously overcharging the payer and pocketing the spread. They then use their control over networks and formularies to steer the most profitable prescriptions to the pharmacies they themselves own.30

The situation has become so contentious that the House Oversight Committee took the extraordinary step of accusing the top executives of the “Big 3” PBMs of providing false testimony to Congress when they claimed under oath that their companies do not engage in patient steering. In Arkansas, the frustration boiled over into a first-in-the-nation law that would have prohibited PBMs from owning pharmacies in the state, a law that was temporarily blocked by a federal judge after a lawsuit from CVS and Express Scripts.

For investors, this intense conflict represents a significant headline and reputational risk for the PBMs’ parent companies. The narrative of a multi-billion-dollar corporation squeezing small, local businesses is politically toxic and fuels the bipartisan drive for reform. Any legislation that mandates fair reimbursement or bans patient steering would directly impact the profitability of the PBMs’ integrated pharmacy operations.

Strategic Implications and the Future of Pharma Investing

The tectonic plates of the pharmaceutical industry are shifting. The opaque, rebate-driven system that has defined drug pricing for the past two decades is under immense pressure from regulators, lawmakers, and payers. For investors, this period of turmoil creates both significant risks and compelling opportunities. The old playbook of simply analyzing a drug’s clinical data and patent life is no longer sufficient. A new, more sophisticated framework is required, one that places a company’s market access strategy and its ability to navigate the PBM gauntlet at the very center of the investment thesis.

An Investor’s Framework: Identifying Red Flags and Green Lights

Synthesizing the complex dynamics we’ve discussed, we can build a practical framework to help investors evaluate companies operating within this evolving ecosystem.

Red Flags for Pharmaceutical & Biotech Companies:

- Heavy Rebate Dependency: A company whose portfolio is dominated by “me-too” drugs in highly competitive therapeutic classes is likely paying massive rebates to secure formulary access. Its revenue is highly vulnerable to any reform that “delinks” PBM compensation from list prices, as this would erode the PBM’s incentive to prefer their high-rebate products.

- Impending Patent Cliff without a Plan: A company with a blockbuster drug nearing the end of its patent life, without a strong pipeline of next-generation products or a clear lifecycle management strategy, is a significant risk. The Zytiga case shows how quickly market share can evaporate once generics arrive.

- Weak Health-Economic Data: In an increasingly cost-conscious world, a new drug with marginal clinical benefits over existing, cheaper therapies will struggle to gain favorable formulary placement. A launch that misses expectations due to poor market access is a major red flag.

Green Lights for Pharmaceutical & Biotech Companies:

- True Innovation: Companies developing first-in-class or best-in-class therapies that address a significant unmet medical need will always have the upper hand in negotiations. PBMs cannot afford to exclude a drug that offers a unique, life-saving benefit, giving the manufacturer significant pricing power.

- Strategic Pricing Models: A manufacturer that launches a new drug with a lower list price, forgoing the high-rebate game, may appeal directly to payers and employers seeking to bypass the gross-to-net bubble. This is a risky but potentially rewarding strategy in the new environment.

- Robust Biosimilar/Generic Pipelines: Companies with a strong capability to develop and launch high-quality, low-cost generics and biosimilars are well-positioned to benefit from the pressure on brand-name prices. Their success, however, still hinges on navigating the formulary complexities highlighted by the Humira case.

Red Flags for PBMs and their Parent Companies:

- High Exposure to Regulatory Risk: A PBM that derives a significant portion of its profit from spread pricing in Medicaid or from opaque rebate arrangements is directly in the crosshairs of federal and state reformers.

- Public Client Disputes: A major client, like Blue Shield of California, publicly breaking with a PBM is a sign of deep dissatisfaction and could signal the beginning of a trend toward disintermediation.

- Inability to Demonstrate Value: In a world demanding transparency, a PBM that cannot provide its clients with clear, auditable data demonstrating that its services are leading to a lower total cost of care will face high rates of client churn.

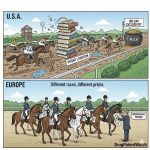

The Future of Drug Pricing: Projecting the Next Decade

The intense, multifaceted pressure on the current PBM model is not a passing storm; it is climate change. The industry will be forced to adapt, and we can project several key trends that will define the next decade of drug pricing:

First, the market is likely to bifurcate. The traditional high-list-price, high-rebate model will not disappear overnight, especially for highly competitive drug classes where manufacturers will continue to use rebates as a weapon to gain market share. However, a parallel channel, based on transparent, net-price or acquisition-cost-plus models, will grow significantly.7 Large employers and health plans, empowered by new transparency laws, will increasingly demand these arrangements, forcing PBMs to compete on the basis of their true administrative efficiency and clinical management skills, not on their ability to manipulate the gross-to-net bubble.

Second, this shift will have a profound impact on pharmaceutical R&D. The economic viability of developing “me-too” drugs with marginal clinical improvements will diminish, as they will lack the leverage to command the high rebates needed for formulary access. This may force manufacturers to refocus their pipelines on two areas: truly innovative, first-in-class drugs that can justify a high price based on value, and biologics and complex specialty drugs, where the high cost of development and manufacturing creates a natural barrier to entry and preserves pricing power for longer.

Finally, drug launch strategies must evolve. For decades, the focus was on convincing physicians of a drug’s clinical benefits. Now, the primary audience is often the P&T committee and the PBM’s financial negotiators. A successful launch will require not just robust clinical trial data, but also compelling pharmacoeconomic evidence that demonstrates the drug’s value and cost-effectiveness compared to the existing standard of care.44 Companies will need to integrate their clinical, commercial, and market access teams far earlier in the development process to ensure they are generating the right evidence to win the formulary battle.

The C-Suite and Investor Call Perspective

The battle for control of the drug pricing narrative is being fought in the court of public opinion and on quarterly investor calls. The language used by executives from PBMs and pharmaceutical companies is carefully chosen and reveals their strategic positioning.

PBM executives, like David Joyner of CVS Health, consistently frame their companies as agents of the client, champions of cost reduction. They emphasize the massive scale of their negotiating power and claim to pass through the vast majority of rebates—with figures like “>98%” being frequently cited.46 They argue that they are a “proven, unequivocal mechanism to negotiate down the price of drugs”.

Pharmaceutical executives and their trade groups paint a very different picture. They argue that PBMs’ misaligned incentives force them to favor higher-priced medicines to maximize their own profits. Pharma CFOs, like Joseph Wolk of Johnson & Johnson, provide the data to back this up, pointing out that the discounts and rebates PBMs demand have exploded, now accounting for as much as 60% of a drug’s list price, up from just 25% a few years ago, squeezing manufacturer margins.

Critics, like Joe Shields of the small PBM trade group Transparency-Rx, dismiss the “Big 3’s” recent embrace of transparency as mere “posturing,” arguing that their business models remain fundamentally “opaque and secretive”.

For you, the investor, the key is to listen for what is not being said and to demand quantifiable metrics. When a PBM executive talks about the percentage of rebates passed through, the critical follow-up question is: what is the total dollar amount of fees retained, including those captured by your affiliated GPO? When a company promises “competitive discounts,” a CFO needs to see the hard numbers: what is the net cost per member per month (PMPM), how does it benchmark against the industry, and can you provide verifiable data that your cost-containment programs are actually working?

The era of accepting vague assurances is over. The future of pharmaceutical investing will belong to those who can cut through the noise, demand transparency, and understand that the path to a drug’s success runs directly through the complex, powerful, and rapidly changing world of the Pharmacy Benefit Manager.

Key Takeaways

- PBMs are Central Power Brokers: Pharmacy Benefit Managers have evolved from simple claims processors to the central gatekeepers of the U.S. prescription drug market, controlling access and pricing for over 275 million Americans through their management of formularies and negotiation of rebates.

- Opaque Business Models Drive Profit: PBMs primarily generate revenue through two models: “spread pricing” (profiting from the difference between what they charge clients and pay pharmacies) and a complex rebate system. Both models have been criticized for their lack of transparency and for creating perverse incentives.

- The “Gross-to-Net Bubble” is a Core Problem: The rebate system, where discounts are tied to a drug’s list price, has created a massive gap between inflated list prices and lower net prices. This incentivizes PBMs to favor high-list-price, high-rebate drugs, often at the expense of lower-cost alternatives, and can increase out-of-pocket costs for patients.

- Formulary is Destiny: A drug’s placement on a PBM’s formulary is a primary determinant of its commercial success. This placement is a function of both clinical evaluation and, critically, the financial rebates offered by the manufacturer. Understanding a drug’s patent life, using tools like DrugPatentWatch, is crucial for predicting its future formulary leverage.

- Market Dominated by a Vertically Integrated Oligopoly: The “Big 3” PBMs (Express Scripts, CVS Caremark, Optum Rx) control 80% of the market. Their vertical integration with major health insurers and their own pharmacies creates a powerful competitive moat but is also the primary target of antitrust scrutiny.

- Unprecedented Regulatory and Legislative Headwinds: The PBM industry is facing a perfect storm of pressure from the FTC, which is investigating anticompetitive practices, and a bipartisan push in Congress and state legislatures to mandate transparency, ban spread pricing, and “delink” PBM compensation from drug prices.

- Real-World Consequences are Evident: Case studies like the slow adoption of Humira biosimilars and the multi-billion-dollar cost of delaying Zytiga generics demonstrate how PBM formulary and rebate strategies can stifle competition and keep costs high.

- The Investment Thesis is Shifting: Investors can no longer evaluate pharmaceutical companies on clinical data and patent life alone. A third, crucial pillar is market access strategy: a company’s ability to navigate the PBM landscape, justify its pricing, and secure favorable formulary placement will be paramount to its future success.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. If PBMs are supposed to lower drug costs, why are they being blamed for high prices?

This is the central paradox of the PBM industry. While they do use their scale to negotiate significant discounts off a drug’s list price, their business models create incentives that can undermine overall cost savings. The primary issue is that their revenue is often tied to a drug’s list price. In a rebate model, a higher list price can mean a larger dollar-value rebate, making a more expensive drug more profitable for the PBM to prefer on its formulary. In a spread pricing model, the opacity allows them to retain a larger portion of the transaction value. Critics argue these practices contribute to the inflation of list prices and prevent the full value of negotiated discounts from reaching payers and patients.1

2. What is the single biggest regulatory threat to the current PBM business model?

The single biggest threat is the concept of “delinking” PBM compensation from the list price of a drug. Currently, PBM revenue from rebates is a percentage of the list price. Proposed reforms would change this to a flat, transparent, “bona fide service fee” for administrative services rendered.1 This would completely sever the financial incentive for a PBM to favor a high-list-price drug over a lower-cost alternative. It would fundamentally alter the economics of formulary management and could pop the “gross-to-net bubble,” forcing a market-wide re-evaluation of drug pricing based on net cost and value, rather than on the size of the rebate.

3. As an investor in a biotech company with a new drug, what is more important: FDA approval or securing PBM formulary access?

While FDA approval is the non-negotiable first step, in today’s market, securing broad and favorable PBM formulary access is arguably just as critical for commercial success. A drug can be a clinical miracle, but if it is excluded from the formularies of the “Big 3” PBMs, it will be inaccessible to the majority of the insured population, and its sales will fail to meet expectations. A successful launch strategy requires planning for PBM negotiations years in advance, generating not just clinical data but also compelling health-economic evidence to prove the drug’s value and justify its cost in a competitive market.

4. How does the vertical integration of a PBM with a health insurer and a pharmacy benefit an investor in that parent company?

Vertical integration creates a powerful, self-reinforcing system that allows the parent company to capture value at multiple points. The health insurer provides a steady stream of members to the PBM. The PBM can then design formularies and networks that steer those members to use the company’s own specialty and mail-order pharmacies, which are typically high-margin businesses. This creates a “sticky” ecosystem that is difficult for competitors to penetrate and allows for greater control over the healthcare dollar. For an investor, this integrated model offers the potential for diversified revenue streams and a strong competitive moat. However, it is also the primary target of antitrust regulators, making it a significant source of risk.2

5. If PBMs pass through over 95% of rebates as they claim, why is there still a problem?

This claim, while potentially true on a technical level for some contracts, can be misleading. First, it doesn’t account for the profits generated through other means, like spread pricing or fees for other services. Second, and more critically, it often overlooks the role of PBM-owned Group Purchasing Organizations (GPOs). A manufacturer may pay a large rebate to the GPO, which then retains a significant “administrative fee” before passing the remainder to the PBM. The PBM can then pass through 98% of what it received from the GPO, but a large portion of the original rebate has already been captured by another entity within the same parent company.8 Finally, even if the full rebate is passed to the health plan, it doesn’t solve the problem that the system still incentivized the choice of a high-list-price drug, and the patient’s out-of-pocket cost is often based on that inflated list price, not the post-rebate net price.

References

- PBM Regulations on Drug Spending | Commonwealth Fund, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/explainer/2025/mar/what-pharmacy-benefit-managers-do-how-they-contribute-drug-spending

- White Paper: The Role of PBMs in the US Healthcare System …, accessed July 30, 2025, https://advisory.avalerehealth.com/insights/white-paper-the-role-of-pbms-in-the-us-healthcare-system

- What Is the Role of a Pharmacy Benefits Manager (PBM)? | Capital Rx, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.cap-rx.com/insights/what-is-the-role-of-a-pharmacy-benefits-manager-pbm

- 5 Things to Know About Rebates | Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Kansas, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.bcbsks.com/employers/resources/5-things-know-about-rebates

- www.patientadvocate.org, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.patientadvocate.org/explore-our-resources/understanding-health-insurance/understanding-drug-tiers/#:~:text=Under%20a%20healthcare%20plan%2C%20the,pay%20before%20receiving%20the%20drug.

- Exploring Drug Tiers and Formulary Exceptions – Patient Advocate Foundation, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.patientadvocate.org/wp-content/uploads/PAF-Empowerment-Pathways-Exploring-Drug-Tiers-and-Exceptions.pdf

- 5 Questions to Evaluate Your Current Pricing Model | RxBenefits, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.rxbenefits.com/blogs/5-questions-to-evaluate-current-pricing-model/

- PBM Pricing Models: Pass Thru vs. Traditional, accessed July 30, 2025, https://innovativerxstrategies.com/pbm-pricing-models-pass-thru-vs-traditional/

- Spread Pricing 101 – The National Community Pharmacists Association | NCPA, accessed July 30, 2025, https://ncpa.org/spread-pricing-101

- Cigna’s 2023 Revenue Grew 8% to $195.3 Billion, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.managedhealthcareexecutive.com/view/cigna-s-2023-revenue-grew-8-to-195-3-billion

- CVS’s Health Services Revenue Grew to $186.8 Billion, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.managedhealthcareexecutive.com/view/cvs-s-health-services-revenue-grew-to-186-8-billion

- Ross, Colleagues Introduce Bipartisan PBM Reform Package | Press Releases, accessed July 30, 2025, https://ross.house.gov/2025/7/ross-colleagues-introduce-bipartisan-pbm-reform-package

- The year of PBM reform: Pharmacy policy progress across the states …, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.pharmacist.com/Blogs/Voices-of-APhA/Article/the-year-of-pbm-reform-pharmacy-policy-progress-across-the-states-in-2025

- Pharmaceutical Rebates: Their Impact and Value Explained – incentX, accessed July 30, 2025, https://incentx.com/blog/pharmaceutical-rebates/

- Five Top Drugmakers Reveal List vs. Net Price … – Drug Channels, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.drugchannels.net/2020/08/five-top-drugmakers-reveal-list-vs-net.html

- www.xevant.com, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.xevant.com/blog/pbm-rebates-explained/#:~:text=When%20PBMs%20secure%20rebates%2C%20the,revenue%20to%20fund%20their%20operations.

- Prescription Drug Rebates and Part D Drug Costs Analysis – AHIP, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.ahip.org/resources/prescription-drug-rebates-and-part-d-drug-costs-analysis

- The Top Pharmacy Benefit Managers of 2024 … – Drug Channels, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.drugchannels.net/2025/03/the-top-pharmacy-benefit-managers-of.html

- Managing the Pharmacy Benefit: The Formulary System – PMC, accessed July 30, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10391211/

- Drug Formulary Explained: Benefits, Types, and How They Work – Truveris, accessed July 30, 2025, https://truveris.com/drug-formulary/

- Drug Tier List: Understanding Prescription Drug Coverage – MetLife, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.metlife.com/stories/benefits/drug-tier-list/

- The Hard Truth About Patent Strategy in a Formulary World – DrugPatentWatch, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/formulary-management-and-lcm-patent-strategies-a-complex-interaction/

- How Drug Life-Cycle Management Patent Strategies May Impact …, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.ajmc.com/view/a636-article

- DrugPatentWatch Report: Five Key Considerations Essential for Drug Patent Strategy, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.geneonline.com/drugpatentwatch-report-five-key-considerations-essential-for-drug-patent-strategy/

- How drug life-cycle management patent strategies may impact formulary management – PubMed, accessed July 30, 2025, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28719222/

- Exploring Biosimilars as a Drug Patent Strategy: Navigating the …, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/exploring-biosimilars-as-a-drug-patent-strategy-navigating-the-complexities-of-biologic-innovation-and-market-access/

- A Comparison of Drug Formularies and the Potential for Cost-Savings – PMC, accessed July 30, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4106615/

- Modeling the Effects of Formulary Exclusions: How Many Patients Could Be Affected by a Specific Exclusion?, accessed July 30, 2025, https://jheor.org/article/94544-modeling-the-effects-of-formulary-exclusions-how-many-patients-could-be-affected-by-a-specific-exclusion

- Top PBMs by 2024 market share – Becker’s Hospital Review | Healthcare News & Analysis, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.beckershospitalreview.com/pharmacy/top-pbms-by-2024-market-share/

- Federal Trade Commission Asserts Significant Anticompetitive Harms in Interim Staff Report on the Pharmacy Benefit Manager Industry | Covington & Burling LLP, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.cov.com/en/news-and-insights/insights/2024/07/federal-trade-commission-asserts-significant-anticompetitive-harms-in-interim-staff-report-on-the-pharmacy-benefit-manager-industry

- Comer: Pharmacy Benefit Managers Must be Held Accountable for …, accessed July 30, 2025, https://oversight.house.gov/release/comer-pharmacy-benefit-managers-must-be-held-accountable-for-role-in-rising-drug-prices%EF%BF%BC/

- UnitedHealth Group Re-Establishes Full Year Outlook and Reports …, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.unitedhealthgroup.com/content/dam/UHG/PDF/investors/2025/unh-reestablishes-full-year-outlook-and-reports-second-quarter-2025-results.pdf

- UnitedHealth Group Re-Establishes Full Year Outlook and Reports Second Quarter 2025 Results – Business Wire, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20250729602583/en/UnitedHealth-Group-Re-Establishes-Full-Year-Outlook-and-Reports-Second-Quarter-2025-Results

- New FTC Report Finds PBMs Increased Prices for Specialty Cancer, HIV Generic Drugs to Generate Billions in Revenue – Pharmacy Times, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.pharmacytimes.com/view/new-ftc-report-finds-pbms-increased-prices-for-specialty-cancer-hiv-generic-drugs-to-generate-billions-in-revenue

- FTC Releases Second Interim Staff Report on Prescription Drug …, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/news/press-releases/2025/01/ftc-releases-second-interim-staff-report-prescription-drug-middlemen

- House Oversight Committee Accuses Pharmacy Benefit Managers of Fraud, Requests Corrections to Congressional Record – Duane Morris, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.duanemorris.com/alerts/house_oversight_committee_accuses_pharmacy_benefit_managers_fraud_requests_corrections_0824.html

- The PBM industry’s desperate attempt to stop reform – PhRMA, accessed July 30, 2025, https://phrma.org/blog/the-pbm-industrys-desperate-attempt-to-stop-reform

- Formulary Coverage of Brand-Name Adalimumab and Biosimilars …, accessed July 30, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11157442/

- Biosimilar use is on the rise – but 1 in 8 patients return to Humira …, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.truveta.com/blog/research/research-insights/biosimilar-use-humira/

- Budget impact analysis of including biosimilar adalimumab on formulary: A United States payer perspective – PMC, accessed July 30, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11522441/

- Study: Janssen’s Delay of Generics for Zytiga Achieved $2.05 Billion …, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.managedhealthcareexecutive.com/view/study-janssen-s-delay-of-generics-for-zytiga-achieved-2-05-billion-in-additional-sales

- Will Blue Shield’s New Pharma Model Disrupt the PBM Market? | AHA, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.aha.org/aha-center-health-innovation-market-scan/2023-08-29-will-blue-shields-new-pharma-model-disrupt-pbm-market

- Federal judge blocks Arkansas law barring pharmacy benefit managers from owning pharmacies in state, accessed July 30, 2025, https://apnews.com/article/arkansas-pbms-pharmacies-lawsuit-bfb96d7a25667c192205507c3ce8d01a

- Drug launch success | Deloitte Insights, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.deloitte.com/us/en/insights/industry/health-care/key-factors-for-successful-drug-launch.html

- Factors for Ensuring a Successful Launch and Market Access for Specialty Drugs and Novel Cell or Gene Therapies – Association of Clinical Research Professionals – ACRP, accessed July 30, 2025, https://acrpnet.org/2023/04/18/factors-for-ensuring-a-successful-launch-and-market-access-for-specialty-drugs-and-novel-cell-or-gene-therapies

- CEOs defend their PBMs. Don’t believe it, says a critic, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.managedhealthcareexecutive.com/view/ceos-defend-their-pbms-don-t-believe-it-says-a-critic

- Big Pharma Highlights How PBMs Secure Significant Savings on …, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.pcmanet.org/pcma-blog/big-pharma-highlights-how-pbms-secure-significant-savings-on-prescription-drugs/08/12/2024/

- Proving PBM ROI to Your CFO: A Guide for HR Leaders – SmithRx, accessed July 30, 2025, https://smithrx.com/blog/proving-pbm-roi-to-your-cfo-a-guide-for-hr-leaders

- How Pharmacy Benefit Managers Are Harming Patients—and What …, accessed July 30, 2025, https://tcf.org/content/commentary/how-pharmacy-benefit-managers-are-harming-patients-and-what-policymakers-can-do-about-it/

- Understanding the Medicaid Prescription Drug Rebate Program – KFF, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/understanding-the-medicaid-prescription-drug-rebate-program/

- Trends of Prescription Drug Manufacturer Rebates in Commercial Health Insurance Plans, 2015-2019 – PMC, accessed July 30, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9077484/

- IDOI Acting Director Testifies at Illinois General Assembly Hearing on Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs), accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.illinois.gov/news/press-release.30242.html

- Managing the Pharmacy Benefit: The Formulary System | Journal of …, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.jmcp.org/doi/10.18553/jmcp.2020.26.4.341a

- PBM Regulations to Watch: Spring 2025 – Optum Business, accessed July 30, 2025, https://business.optum.com/en/insights/pharmacy-legislative-rules-spring-2025.html

- How CBO Estimated the Budgetary Impact of Key Prescription Drug Provisions in the 2022 Reconciliation Act | Congressional Budget Office, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.cbo.gov/publication/58850

- CivicaScript Launches Initial Generic Drug, Plans Several More in Coming Years – Navitus, accessed July 30, 2025, https://navitus.com/news/civicascript-launches-initial-generic-drug-plans-several-more-in-coming-years/

- Navigating pharma loss of exclusivity | EY – US, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.ey.com/en_us/insights/life-sciences/navigating-pharma-loss-of-exclusivity

- CVS HEALTH REPORTS FOURTH QUARTER AND FULL-YEAR 2023 RESULTS, accessed July 30, 2025, https://investors.cvshealth.com/investors/newsroom/press-release-details/2024/CVS-HEALTH-REPORTS-FOURTH-QUARTER-AND-FULL-YEAR-2023-RESULTS/default.aspx

- CVS Health Corporation’s Annual Report (Form 10-K) for the Fiscal Year Ended December 31, 2024 – Webull, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.webull.com/news/12300231250835456

- Exhibit 99.1 CVS HEALTH REPORTS FOURTH QUARTER AND FULL-YEAR 2023 RESULTS WOONSOCKET, RHODE ISLAND, February 7, 2024, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.cvshealth.com/content/dam/enterprise/cvs-enterprise/pdfs/2024/Q4-2023-Earnings%20Release-Final.pdf

- ci-20211231 – SEC.gov, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/1739940/000173994022000007/ci-20211231.htm

- Cigna Delivers Strong 2018 Results as it Completes Express Scripts Transaction; Company Positioned for Significant Growth, accessed July 30, 2025, https://newsroom.thecignagroup.com/cigna-delivers-strong-2018-results-as-it-completes-express-scripts-transaction-company-positioned-for-significant-growth

- Financial & Earnings Reports – UnitedHealth Group, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.unitedhealthgroup.com/investors/financial-reports.html

- Market Analysis: The Impact of Biosimilars on the Generic Drug Industry in Europe, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/market-analysis-the-impact-of-biosimilars-on-the-generic-drug-industry-in-europe/

- Case Study Level 2: Regulatory Scientific Concepts Biosimilars in Patient Care – FDA, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/media/154919/download

- Negotiation Strategies for Antiretroviral Drug Purchasers in the United States – PMC, accessed July 30, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4945239/