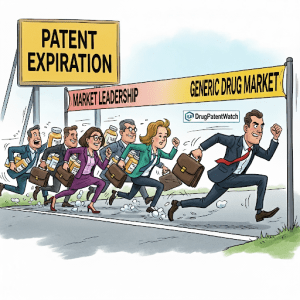

Welcome to the high-stakes world of generic pharmaceuticals. This isn’t just a story about lower-cost medicine; it’s a dynamic, multi-billion-dollar arena of strategic warfare, where fortunes are made and lost not just in the laboratory, but in the courtroom, the boardroom, and the regulatory corridors of power. At the heart of this relentless competition lies a recurring, predictable, and market-shattering phenomenon: the patent cliff.

Imagine a massive transfer of wealth, a seismic shift in market value that happens like clockwork. This is the patent cliff—the period when a blockbuster drug’s patent protection expires, opening the floodgates to generic competition. The numbers are staggering. The global generic drug market is a behemoth, projected to surge from a baseline of approximately $450-$500 billion in the mid-2020s to well over $700 billion by the early 2030s. This explosive growth is fueled by an impending wave of patent expirations set to release over $200 billion in branded drug sales into the competitive sphere between now and 2030.1

In the United States, the world’s largest pharmaceutical market, the impact is even more pronounced. Generic drugs account for more than 90% of all prescriptions filled, yet they represent only about 18% of the nation’s total prescription drug spending.1 This incredible efficiency has saved the U.S. healthcare system an estimated $3.1 trillion over the past decade alone.1 But this disparity—massive volume versus a small share of cost—reveals a fundamental market paradox. Value in the generic world is driven by volume, operational efficiency, and impeccable timing, not by premium pricing. It’s a landscape defined by intense commoditization and razor-thin margins.

So, in a market defined by such immense opportunity and such ferocious competition, how does a company move beyond simply participating to strategically dominating? How do you turn the ticking clock of a patent expiration into your company’s next great growth engine?

The answer lies in mastering the intricate dance of intellectual property, regulatory frameworks, and market intelligence. It requires a deep, nuanced understanding of the legal bedrock that governs this industry, the strategic levers that create competitive advantage, and the operational excellence needed to execute flawlessly. This report is your playbook. We will dissect the twin shields of patents and exclusivities, map the upcoming patent cliff, and demystify the landmark legislation that created the modern generic industry. We will dive deep into the high-stakes game of patent challenges, explore the intelligence tools that separate the winners from the losers, and provide a comprehensive blueprint for identifying, developing, and launching a successful generic drug.

This is more than an analysis; it is a strategic guide designed for the leaders and decision-makers tasked with navigating this complex environment. The core challenge for a generic manufacturer isn’t just making a copy of a drug; it’s winning a high-volume, low-margin race against time, competitors, and the formidable defenses of innovator companies. Let’s begin.

Section 1: The Twin Shields of Monopoly: Understanding Patents and Regulatory Exclusivities

To seize the opportunity presented by a patent expiration, you must first understand precisely what is expiring. The market monopoly of a brand-name drug is not protected by a single wall, but by a complex, overlapping system of defenses. These defenses fall into two distinct categories: patents, which are a form of intellectual property granted by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO), and regulatory exclusivities, which are marketing protections granted by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). They are not the same, they do not always run in parallel, and mastering their interplay is the first step toward building a winning generic strategy.

The Foundation of Innovation: A Deep Dive into Pharmaceutical Patents

At its core, the patent system is the engine of pharmaceutical innovation. Developing a new drug is an extraordinarily risky and capital-intensive endeavor. The journey from a promising molecule in a lab to an approved medicine on a pharmacy shelf can take 5 to 15 years and cost anywhere from $300 million to a staggering $4.5 billion. Given these high failure rates and immense upfront investment, patents provide the necessary incentive: a temporary, legally protected monopoly that allows the innovator company to recoup its R&D costs and generate a profit.6

Under the global Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS), all World Trade Organization (WTO) member nations, including the United States, grant a standard patent term of 20 years from the date the patent application was filed. However, a critical distinction exists between this statutory patent term and the effective patent life—the actual period a drug is on the market without generic competition. Because a substantial portion of the 20-year term, often 10 to 15 years, is consumed by preclinical research, clinical trials, and the rigorous FDA review process, the average effective market exclusivity from a drug’s launch is typically only 7 to 10 years.

This limited window of profitability is protected by a “patent thicket”—a portfolio of different types of patents that create multiple layers of defense. Understanding these layers is crucial for any potential generic challenger.

- Composition of Matter Patents: These are the crown jewels of pharmaceutical IP. A composition of matter patent protects the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) itself—the core molecule responsible for the drug’s therapeutic effect. This is the strongest and most valuable form of patent protection, as it is difficult to design around without creating an entirely new drug.

- Formulation Patents: These patents don’t cover the drug molecule itself, but rather the specific way it is delivered to the patient. This can include unique formulations like extended-release tablets, nanoparticle delivery systems, inhalers, or transdermal patches. These patents are designed to improve a drug’s efficacy, safety profile, or patient compliance.

- Method of Use Patents: These patents protect a novel therapeutic use for a drug. For example, a drug initially approved to treat heart disease might later be found effective against a certain type of cancer. The innovator can obtain a new patent covering this new method of use, even if the composition of matter patent on the drug itself has expired.6

- Process Patents (Methods of Manufacture): These patents cover innovative and non-obvious methods for manufacturing a drug. This could involve a unique purification technique, a novel catalyst, or a specific crystallization process that results in a purer or more stable product.

- Other Ancillary Patents: The patent thicket can be further fortified with patents on specific dosage regimens, crystalline forms of the API (polymorphs), metabolites (the substances the body breaks the drug down into), or even combinations of the drug with other active ingredients.

Beyond the Patent: The Critical Role of FDA-Granted Regulatory Exclusivities

While patents protect the invention, regulatory exclusivities protect the data and the market. Granted by the FDA upon a drug’s approval, these exclusivities are entirely separate from patents and serve as an independent barrier to generic competition. They were designed to promote a balance between rewarding innovation and encouraging the availability of lower-cost generics.8 A drug can have both patent protection and regulatory exclusivity, and they can run concurrently or at different times.

The key types of regulatory exclusivity in the United States include:

- New Chemical Entity (NCE) Exclusivity: This is a cornerstone of drug innovation. An NCE is a drug that contains an active moiety (the part of the molecule responsible for its therapeutic effect) that has never before been approved by the FDA. Upon approval, such a drug is granted a 5-year period of market exclusivity.6 During this time, the FDA cannot even accept an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) from a generic manufacturer for the first four years (or five years if the generic does not challenge a patent). This provides a guaranteed period of market protection, regardless of the drug’s patent status.

- Orphan Drug Exclusivity (ODE): To incentivize the development of treatments for rare diseases, the Orphan Drug Act of 1983 provides a powerful incentive. A drug granted “orphan” status—meaning it treats a condition affecting fewer than 200,000 people in the U.S.—receives 7 years of market exclusivity upon approval for that specific indication.6 This exclusivity prevents the FDA from approving another application for the same drug for the same orphan disease during that period.

- “New Clinical Investigation” Exclusivity: This 3-year exclusivity is granted for the approval of a drug that is not an NCE but for which the application contained reports of new, essential clinical investigations (other than bioavailability studies) conducted or sponsored by the applicant.8 This often applies to applications for a new dosage form, a new indication for an already-approved drug, or a change from prescription to over-the-counter (OTC) status.

- Pediatric Exclusivity (PED): This unique provision grants an additional 6 months of exclusivity to a drug sponsor who conducts pediatric studies in response to a written request from the FDA. Crucially, this 6-month period is added to the end of all other existing patent and exclusivity periods for that drug, providing a powerful incentive to study the safety and efficacy of medicines in children.6

- Biologics Exclusivity: Under the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA), new biologic drugs are granted a lengthy 12-year period of market exclusivity. This extended period reflects the significantly higher cost and complexity of developing biologic medicines compared to traditional small-molecule drugs.

The distinction between these two protection systems is not merely a legal technicality; it creates a complex, overlapping timeline of barriers that a generic manufacturer must meticulously map. A drug’s primary composition of matter patent could expire, seemingly opening the door for generic entry, only for that door to be held shut by a remaining period of NCE or pediatric exclusivity. For orphan drugs, the situation is often reversed; the 7-year ODE may expire, but the drug could still be protected for many more years by its underlying patents. Therefore, the strategic planning for a generic launch is dictated by a simple but critical rule: the first legal opportunity for market entry is determined by whichever barrier—the last-to-expire relevant patent or the last-to-expire applicable exclusivity—falls last. A successful strategy requires navigating this dual-track system to identify the true, and often elusive, date of entry.

The Art of Lifecycle Management: Understanding “Evergreening”

Innovator companies do not passively wait for their patents to expire. They engage in a sophisticated set of strategies known as “evergreening” or “product lifecycle management” to extend their drug’s monopoly for as long as possible. This is not an illegal practice but rather a strategic utilization of the patent and regulatory systems to build new layers of protection around a successful product.

Common evergreening tactics directly leverage the patent types discussed earlier. After securing the core composition of matter patent, a company will continue to research its own drug, seeking to patent:

- New Formulations: Developing a new version, such as a once-daily extended-release tablet to replace an older twice-daily version.

- New Delivery Methods: Creating an inhalable or injectable form of a drug that was previously an oral pill.

- New Indications: Discovering and patenting new therapeutic uses for the drug.

- New Combinations: Combining the drug with another active ingredient into a single pill.

Each of these innovations can be granted a new patent, often with a 20-year term. While these secondary patents are typically not as strong as the original composition of matter patent, they create a formidable “patent thicket” that a generic company must navigate or challenge in court. It is this thicket of secondary patents that forms the primary battlefield of modern generic drug litigation.

Table 1: Pharmaceutical Market Protections Compared

| Protection Type | Granting Body | Standard Duration | Purpose | Strategic Implication for Generics |

| Composition of Matter Patent | USPTO | 20 years from filing | Protect the core active molecule (API) | The primary patent that must expire or be invalidated. The strongest barrier to entry. |

| Formulation/Method of Use Patent | USPTO | 20 years from filing | Protect new delivery methods, indications, etc. | Forms the “patent thicket.” These are the patents most commonly challenged via Paragraph IV litigation. |

| New Chemical Entity (NCE) Exclusivity | FDA | 5 years from approval | Incentivize development of novel drugs | An absolute bar to ANDA submission/approval that can extend market protection beyond patent expiry. |

| Orphan Drug Exclusivity (ODE) | FDA | 7 years from approval | Incentivize development for rare diseases | Protects a specific orphan indication. A generic may be able to launch for a non-orphan indication if patents permit. |

| New Clinical Investigation Exclusivity | FDA | 3 years from approval | Incentivize improvements to existing drugs | A shorter but important barrier for new formulations or indications of older drugs. |

| Pediatric Exclusivity (PED) | FDA | 6 months (add-on) | Incentivize pediatric studies | Tacked onto the end of all other patents/exclusivities, often creating a final 6-month delay to generic entry. |

| Biologics Exclusivity (BPCIA) | FDA | 12 years from approval | Incentivize development of complex biologics | A significantly longer exclusivity period that creates a much higher barrier for biosimilar competitors. |

Section 2: Anatomy of the Patent Cliff: From Revenue Erosion to Market Opportunity

The term “patent cliff” has become a fixture in the pharmaceutical industry lexicon, evoking images of a sudden and perilous drop-off. For the innovator company that developed a blockbuster drug, it represents a moment of profound financial reckoning. But for the prepared generic manufacturer, it represents something else entirely: a predictable, recurring, and multi-billion-dollar market opportunity.

Defining the “Patent Cliff”

The patent cliff refers to the sharp, often precipitous decline in revenue and profitability that a pharmaceutical company experiences when one or more of its leading, high-revenue products loses market exclusivity and faces generic competition.2 For a “blockbuster” drug—one with annual sales exceeding $1 billion—the financial impact can be devastating.

Once the protective shields of patents and exclusivities fall, the market dynamics transform almost overnight. Generic manufacturers, who can produce bioequivalent versions of the drug at a fraction of the cost, enter the market aggressively. Healthcare providers, insurers, and patients, driven by powerful cost-saving incentives, rapidly switch to the more affordable alternatives.

The speed and depth of this revenue erosion are dramatic. It is not uncommon for a blockbuster drug to lose up to 80% of its revenue within the first year of facing generic or biosimilar competition. Generic alternatives typically enter the market at a price that is approximately 30% of the original branded price. As more generic competitors enter, a fierce price war ensues, often driving the cost down to as little as 10-20% of the original price. This phenomenon is not a hypothetical risk; it is a recurring cycle that has reshaped the fortunes of major pharmaceutical companies for decades and is poised to do so again on an unprecedented scale.

The Approaching Wave: Blockbuster Drugs Facing Imminent Expiration

The pharmaceutical industry is currently bracing for one of the most significant patent cliffs in its history. Between now and 2030, a cohort of the world’s best-selling drugs are set to lose their market exclusivity, putting an estimated $200 billion to $230 billion in annual revenue at risk.2 This is not a distant threat; it is an imminent and massive redistribution of market value that is creating a gold rush for generic and biosimilar developers.

The list of drugs approaching this cliff reads like a who’s who of modern medicine:

- Keytruda (pembrolizumab): Merck’s revolutionary cancer immunotherapy, a titan of the industry that generated over $29 billion in sales in 2024, faces its key patent expiration in 2028.3 The sheer scale of Keytruda’s sales—accounting for 40% of Merck’s pharmaceutical revenue in 2023—underscores the magnitude of this single event.

- Eliquis (apixaban): This blockbuster anticoagulant, co-marketed by Bristol Myers Squibb and Pfizer, is a critical treatment for preventing strokes and blood clots. With over $13 billion in 2024 sales for BMS alone, its loss of exclusivity in 2026 represents a massive challenge for the company.

- Opdivo (nivolumab): Another foundational immunotherapy from Bristol Myers Squibb, Opdivo is set to lose exclusivity in 2028, compounding the company’s revenue challenges.2

- Stelara (ustekinumab): Johnson & Johnson’s blockbuster treatment for immune-mediated diseases like psoriasis and Crohn’s disease is another major product facing the cliff.

- Humira (adalimumab): While its main U.S. patents began expiring in 2023, AbbVie’s immunology juggernaut, which recorded over $21 billion in sales in 2022, serves as a recent and powerful example of the cliff’s impact, with biosimilar competition now actively eroding its market dominance.2

- Entresto (sacubitril/valsartan): Novartis’s leading heart failure drug, with $7.8 billion in sales, faces loss of exclusivity in July 2025, marking one of the first major dominoes to fall in this new wave.

This is not a singular event but a recurring industry cycle. The predictability of patent expirations creates a ticking clock that governs the strategic planning of every major pharmaceutical company. For innovators, the cliff is a constant motivator to refresh their pipelines and seek new sources of growth. For generic manufacturers, it provides a clear roadmap of future opportunities, allowing them to begin R&D and strategic planning years in advance. The competition for the generic versions of Keytruda and Eliquis is not something that will begin in 2026 or 2028; it is happening right now in the labs and legal departments of generic companies around the world. The strategic game is about being perfectly positioned to launch on “Day 1” the moment exclusivity is lost.

Strategic Responses of Innovator Companies

Brand-name pharmaceutical companies are not passive victims of the patent cliff; they are active combatants employing a range of defensive strategies to mitigate the inevitable revenue loss. Understanding these responses is critical for any generic challenger, as they shape the competitive landscape.

- Pipeline Replenishment through R&D: The most fundamental strategy is to invent the next generation of blockbuster drugs to replace the revenue from expiring ones. Companies like AstraZeneca are aggressively investing in their R&D pipeline, with over 90 late-stage studies underway, to build a portfolio that can withstand the loss of exclusivity for key products like Farxiga.

- Mergers & Acquisitions (M&A): When in-house R&D is not fast enough, large pharma firms turn to M&A. They acquire smaller biotech companies with promising drugs in their pipelines to buy new revenue streams and offset losses from expiring patents.2

- Product Lifecycle Management: As discussed previously, innovators use “evergreening” tactics, such as developing new formulations or seeking new indications, to create new patents and exclusivities. Merck, for example, is pursuing a subcutaneous formulation of Keytruda, which, if successful, could help soften the impact of the 2028 patent cliff by converting patients to a new, patent-protected version.

- Legal and Regulatory Delays: Innovator companies often use litigation as a tool to delay generic entry. By suing a generic challenger for patent infringement, they can trigger an automatic 30-month stay on FDA approval, buying valuable extra time on the market.3 BMS and Pfizer have engaged in strong legal efforts to stall generic versions of Eliquis.

- Cost-Cutting and Restructuring: In some cases, when the pipeline is not robust enough to offset the impending losses, companies resort to significant cost-cutting measures. Bristol Myers Squibb, facing cliffs for both Eliquis and Opdivo, has announced plans for approximately 2,200 layoffs as part of a plan to save up to $1.5 billion by 2025.

These defensive maneuvers create a complex and dynamic battlefield. A generic company must not only master the science of replication but also anticipate and counter the strategic and legal chess moves of a well-funded and highly motivated innovator opponent.

Table 2: The Approaching Patent Cliff – Key Blockbuster Expirations (2025-2030)

| Drug Name (Brand) | Originator Company | Primary Indication | 2024 Global Sales (Approx.) | Key Patent Expiration Year |

| Entresto | Novartis | Heart Failure | $7.8 Billion | 2025 |

| Farxiga | AstraZeneca | Type 2 Diabetes / Heart Failure | $7.7 Billion | 2025 |

| Xolair | Novartis / Genentech | Asthma / Urticaria | N/A | 2025 |

| Yervoy | Bristol Myers Squibb | Melanoma (Cancer) | $2.5 Billion | 2025 |

| Eliquis | Bristol Myers Squibb / Pfizer | Anticoagulant | >$13 Billion (BMS) | 2026 |

| Januvia / Janumet | Merck & Co. | Type 2 Diabetes | N/A | 2026 |

| Prevnar | Pfizer | Pneumococcal Vaccine | N/A | 2026 |

| Ibrance | Pfizer | Breast Cancer | N/A | 2027 |

| Xtandi | Pfizer / Astellas | Prostate Cancer | N/A | 2027 |

| Keytruda | Merck & Co. | Multiple Cancers (Immunotherapy) | >$29 Billion 15 | 2028 |

| Opdivo | Bristol Myers Squibb | Multiple Cancers (Immunotherapy) | N/A | 2028 |

| Gardasil / Gardasil 9 | Merck & Co. | HPV Vaccine | N/A | 2028 |

| Stelara | Johnson & Johnson | Psoriasis / Crohn’s Disease | N/A | 2029 (est.) |

| Cosentyx | Novartis | Psoriasis / Arthritis | N/A | 2029 |

Section 3: The Legal Bedrock: How the Hatch-Waxman Act Forged the Modern Generic Industry

To operate successfully in the generic drug market, one cannot simply be a scientist or a businessperson; one must also be a student of legal history. The entire modern landscape of generic competition in the United States was sculpted by a single, landmark piece of legislation: the Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984, universally known as the Hatch-Waxman Act.4 This act was a masterclass in legislative compromise, creating a new world of opportunity for generic manufacturers while simultaneously offering new protections to innovator companies.

A Landmark Compromise: The Genesis and Goals of Hatch-Waxman

Before 1984, the generic drug industry was a shadow of its current self. Generic manufacturers faced a nearly insurmountable barrier: to get a drug approved, they had to submit a full New Drug Application (NDA), complete with their own expensive and time-consuming clinical trials to independently prove the drug’s safety and effectiveness. This duplicative process was a massive deterrent, and as a result, generic drugs were rare, accounting for a mere 19% of all prescriptions filled.

The Hatch-Waxman Act, named for its sponsors Senator Orrin Hatch and Representative Henry Waxman, was designed to break this logjam. It established a grand bargain, a carefully balanced framework intended to achieve two seemingly contradictory goals:

- Promote Generic Competition: To make medications more affordable and accessible to the public by creating a streamlined approval pathway for generic drugs.

- Preserve Innovation Incentives: To ensure that brand-name companies still had sufficient incentive to undertake the risky and costly process of developing new medicines.

The act was transformative. By creating a viable and predictable path to market for generics, it unleashed a wave of competition that has fundamentally altered the economics of healthcare. Today, thanks to the framework established by Hatch-Waxman, generic drugs account for over 90% of prescriptions in the U.S., saving the healthcare system billions of dollars annually.4

The Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA): Streamlining the Path to Market

The cornerstone of the Hatch-Waxman Act is the Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) pathway, codified under Section 505(j) of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act.4 This was the legislative key that unlocked the generic industry.

The genius of the ANDA process is that it allows a generic manufacturer to rely on the FDA’s previous finding that the innovator’s drug is safe and effective. Instead of re-running massive clinical trials, the ANDA applicant’s primary scientific burden is to demonstrate bioequivalence.4 This means proving, through scientific studies, that their generic product performs in the same manner as the brand-name drug, known as the

Reference Listed Drug (RLD).21

Specifically, an ANDA submission must contain data showing that the generic drug is identical to the RLD in:

- Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API)

- Dosage Form (e.g., tablet, capsule)

- Strength

- Route of Administration (e.g., oral, injectable)

- Conditions of Use and Labeling

By eliminating the need for duplicative clinical trials, the ANDA process dramatically reduces the time and cost of bringing a generic drug to market.21 However, it’s crucial to understand that “abbreviated” does not mean simple. The ANDA review process is still a rigorous scientific and regulatory evaluation by the FDA that can take, on average, around 30 months to complete.21

Key Provisions and Their Strategic Impact

Beyond the ANDA pathway itself, Hatch-Waxman introduced several other critical provisions that define the strategic landscape for both brand and generic companies.

- Patent Term Extension: In a key concession to innovator companies, the act allows them to apply for an extension of their patent term to compensate for time lost during the lengthy clinical trial and FDA review process. This can restore up to five years of patent life, giving brands a longer period of market exclusivity to recoup their investment.6

- “Safe Harbor” Provision: This is a vital protection for generic manufacturers. The act created a “safe harbor” that exempts the development work and testing necessary for an ANDA submission from claims of patent infringement. Without this provision, a generic company could be sued for infringement the moment it began to develop its product, effectively making it impossible to prepare an ANDA before the brand’s patents expired.

- Patent Certifications: Hatch-Waxman created a formal mechanism for addressing the innovator’s patents. When submitting an ANDA, the generic applicant must make a certification for each patent listed in the FDA’s Orange Book for the RLD. This certification is a formal declaration of the generic company’s intentions regarding the brand’s patents and is the legal trigger for potential litigation.24

It is this last provision—the patent certification—that transforms the ANDA process from a purely scientific exercise into a strategic legal maneuver. The Hatch-Waxman Act did not just create a regulatory pathway; it created a structured, predictable, and highly litigious system of conflict. The act’s true brilliance lies in how it channels commercial competition into a formal legal process. For many of the most lucrative drug products, filing an ANDA is not a simple regulatory step; it is the first shot fired in a legal war. This makes legal strategy as important as scientific development. A successful generic company cannot be merely a good manufacturer; it must also be a sophisticated legal operator, capable of assessing the strength of an innovator’s patent portfolio and willing to fund and win high-stakes patent litigation. This reality elevates the role of legal counsel from a support function to a core component of the business development and strategy team.

Section 4: The Strategic Heart of Generic Competition: Mastering the Paragraph IV Challenge

While the Hatch-Waxman Act created the framework for generic competition, it was a specific, high-risk provision within that framework that truly ignited the industry and became the engine of early generic entry: the Paragraph IV certification. This is the strategic heart of the generic drug business, a pathway that rewards courage, legal acumen, and precise timing with an enormous commercial prize. Mastering the Paragraph IV challenge is the key to moving from a follower to a market leader.

The Four Patent Certifications: A Strategic Crossroads

When a generic company files an ANDA, it must address every patent that the innovator company has listed in the Orange Book for the reference drug. It does this by making one of four possible certifications for each patent 24:

- Paragraph I Certification: A statement that no patent information has been filed with the FDA for the reference drug.

- Paragraph II Certification: A statement that the patent has already expired.

- Paragraph III Certification: A statement that the generic company will wait to launch its product until the date the patent expires. This is the non-confrontational, “wait-and-see” approach.

- Paragraph IV (PIV) Certification: A bold and aggressive declaration that the patent listed in the Orange Book is invalid, unenforceable, or will not be infringed by the generic product.

Filing a Paragraph IV certification is a direct challenge to the innovator’s intellectual property. It is an act of legal defiance that says, “We believe your patent is either weak or irrelevant to our product, and we are not going to wait for it to expire.” This is the high-risk, high-reward pathway that defines the most competitive segments of the generic market.

The Mechanics of a Paragraph IV Filing

Initiating a Paragraph IV challenge sets in motion a highly structured and time-sensitive legal process:

- The Notice Letter: Within 20 days of the FDA officially accepting its ANDA for review, the generic applicant must send a formal “Paragraph IV notice letter” to both the brand-name drug sponsor and the owner of the patent being challenged. This letter must provide a detailed statement of the factual and legal basis for the generic company’s opinion that the patent is invalid, unenforceable, or not infringed.

- The 45-Day Window: Upon receiving the notice letter, the brand company and patent holder have a critical 45-day window to respond. Their primary response is to file a patent infringement lawsuit against the generic applicant in federal court.24

- The 30-Month Stay: If the brand company files suit within this 45-day period, it triggers one of the most powerful provisions in the Hatch-Waxman Act: an automatic 30-month stay of FDA approval for the ANDA.17 This means the FDA is generally prohibited from granting final approval to the generic application for up to 30 months, or until the patent litigation is resolved in the generic’s favor, whichever comes first. This provision gives the brand company a significant, guaranteed period of continued market exclusivity to defend its patent in court.

The Ultimate Prize: 180-Day Marketing Exclusivity

So why would a generic company willingly invite a costly lawsuit and a potential 30-month delay? The answer lies in the ultimate prize that Hatch-Waxman offers to successful challengers: 180-day marketing exclusivity.24

This provision is the powerful incentive designed to encourage generic companies to challenge potentially weak or invalid patents, thereby clearing the way for earlier competition and greater public access to affordable medicines. The law states that the first generic applicant to submit a “substantially complete” ANDA containing a Paragraph IV certification is eligible for a 180-day period of marketing exclusivity.9

The value of this exclusivity cannot be overstated. During this six-month period, the FDA is barred from approving any subsequent generic applications for the same drug. This effectively creates a temporary duopoly in the market, consisting only of the high-priced brand-name drug and the single, first-to-file generic. This allows the first generic to:

- Price at a Premium: Instead of facing an immediate price collapse from multiple competitors, the first generic can price its product at a modest discount to the brand, capturing enormous market share while maintaining high profit margins.

- Establish Market Dominance: By being the sole generic option for six months, the company can build strong relationships with pharmacies, distributors, and payers, solidifying its market position before other generics arrive.

- Recoup Litigation Costs: The significant profits earned during this period are often more than enough to cover the substantial legal fees incurred in challenging the patent.

This “first-to-file” incentive transforms the generic drug launch from a purely manufacturing-based race into an information and timing race. The winner is not necessarily the company with the best manufacturing process, but the one who can prepare a flawless, “substantially complete” application and file it with the FDA first. This creates a “winner-take-all” (or “winner-take-most”) dynamic for the first six months of the generic market, where the financial difference between being the first filer and the second can be hundreds of millions of dollars. This reality places an enormous premium on pre-filing intelligence, rapid and efficient R&D, and, most importantly, impeccable regulatory affairs expertise to ensure the ANDA dossier is perfect on the first attempt. The critical path for a successful Paragraph IV launch is a sprint to the FDA’s doorstep.

Section 5: The Intelligence Engine: Leveraging the Orange Book and Platforms like DrugPatentWatch

In the high-stakes, information-driven race of generic drug development, data is not just a resource; it is the lifeblood of strategy. The ability to gather, analyze, and act upon precise intelligence regarding patents, exclusivities, and competitive activity is what separates the market leaders from the laggards. This intelligence engine is powered by two key components: the FDA’s official registry, the Orange Book, and the sophisticated, value-added platforms that build upon its foundation.

The “Orange Book”: The Official Registry of Patents and Exclusivities

The official starting point for all generic drug intelligence is the FDA’s publication, Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations, universally known by its distinctive cover color as the Orange Book.4 This is the definitive public resource, the bible for generic manufacturers, containing the critical data needed to plan a development program and navigate the regulatory pathway.

The Orange Book serves several crucial functions:

- Lists All FDA-Approved Drugs: It provides a comprehensive list of all prescription and over-the-counter drug products approved by the FDA on the basis of safety and effectiveness.

- Identifies Reference Listed Drugs (RLDs): For any generic development program, the Orange Book identifies the specific RLD that the generic must reference and prove bioequivalence to in its ANDA submission.22

- Provides Patent Information: This is its most critical function for strategic planning. The Orange Book lists the patents that the brand-name sponsor claims cover its drug. By statute, this includes patents on the drug substance (API), the drug product (formulation or composition), and methods of using the drug. It’s important to note what is not included: process patents, packaging patents, and patents on metabolites or intermediates are not listed in the Orange Book. This list is the basis for the patent certifications a generic company must make in its ANDA.24

- Details Regulatory Exclusivities: The Orange Book is the official source for all FDA-granted marketing exclusivities, such as NCE, ODE, and Pediatric exclusivity, along with their expiration dates.

- Assigns Therapeutic Equivalence (TE) Codes: It provides TE codes that allow pharmacists and healthcare providers to determine whether a generic drug is therapeutically equivalent to the brand and can be substituted.

The modern Orange Book is an electronic, searchable database, allowing users to quickly find patent and exclusivity expiration dates for a given product. These dates provide the foundational timeline for any generic launch strategy, offering a rough estimate of when the market may open to competition.

Beyond the Basics: The Role of Specialized Business Intelligence

While the Orange Book is essential, it provides raw, static data. It tells you what patents are listed and when they expire, but it doesn’t tell you the whole story. It doesn’t tell you who else is targeting the same drug, the status of ongoing litigation, or the broader international patent landscape. To translate raw data into actionable strategic intelligence, companies turn to specialized business intelligence platforms.

Platforms like DrugPatentWatch are designed specifically for this purpose. They aggregate data from the Orange Book and enrich it with numerous other critical data sources to provide a holistic, dynamic view of the competitive landscape.3 These platforms are not just data repositories; they are powerful analytical tools that enable companies to:

- Conduct Comprehensive Patent Landscape Analysis: Go beyond the U.S. patents listed in the Orange Book to map the entire international patent ecosystem for a drug or technology. This helps identify global competitors, potential threats, and “white spaces”—areas with little patent protection that could be ripe for new R&D.

- Monitor Competitors in Real-Time: The most crucial advantage is the ability to track competitive activity. These platforms monitor and provide alerts on new ANDA filings, specifically identifying Paragraph IV challenges as they occur. This allows a company to know immediately how many competitors are targeting a product and who has secured the coveted “first-to-file” position.25

- Track Patent Litigation: They provide detailed information on patent litigation filed in response to Paragraph IV challenges, including case status, key arguments, and outcomes. This intelligence is vital for assessing the likelihood of a patent being invalidated and the potential timing of generic entry.3

- Integrate Multiple Data Streams: A key value proposition is the integration of disparate data sets. A platform like DrugPatentWatch connects patent data with FDA approvals, clinical trial information, API supplier databases, and drug pricing data, creating a single, comprehensive source of truth.32

This integrated intelligence supports a wide range of strategic decisions across the organization. Business development teams can use it to identify the most promising and least crowded market entry opportunities. Portfolio managers can more accurately forecast generic competition and budget accordingly. Even wholesalers and distributors can use this data to prevent being overstocked on a branded drug right before its patent expires and its value plummets.3

Effective use of these intelligence platforms allows a generic company to shift from a reactive to a proactive and predictive strategic posture. The strategic process is transformed. Instead of just asking, “When does the patent expire?”, a strategist armed with this level of data can now ask more sophisticated questions: “Given that three competitors have already filed a Paragraph IV challenge against the formulation patent, and litigation is ongoing, what is the probability of a successful challenge? Should we invest in this crowded market, or should we pivot to another drug where we see no P-IV filings yet, suggesting a less competitive ‘first-to-file’ opportunity?”

This data-driven approach is the key to maximizing return on investment. Advanced business intelligence is a force multiplier, enabling companies to allocate their finite R&D and legal resources to the opportunities with the highest probability of success, avoiding costly battles in overly saturated markets and identifying overlooked, low-competition niches. In the modern generic landscape, this is not a luxury; it is a prerequisite for survival and success.

Section 6: A Blueprint for Opportunity: Identifying and Vetting High-Potential Generic Targets

The generic drug market is littered with opportunities, but not all are created equal. Chasing the wrong target can lead to wasted R&D investment, costly legal defeats, and a launch into a hyper-competitive market with non-existent profit margins. A disciplined, data-driven approach to identifying and vetting potential targets is the foundation of a successful generic portfolio strategy. This process involves a rigorous blend of quantitative financial analysis and qualitative assessment of technical and competitive barriers.

Quantitative Analysis: Sizing the Market and Forecasting Revenue

The first step in evaluating any potential generic target is to understand the size of the prize. This begins with a thorough analysis of the brand-name drug’s historical and current sales data to establish the total addressable market.

The overall market context is incredibly favorable. The global generic drug market is on a powerful growth trajectory, projected to expand from its current base of around $450-$500 billion to over $700 billion by the early 2030s, representing a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 5-8%. In the U.S., the market is forecast to reach approximately $231 billion by 2034. This growth is underpinned by powerful and predictable tailwinds, including the massive upcoming patent cliff—which will put over $200 billion in branded sales up for grabs—and the relentless global pressure for healthcare cost containment.

When evaluating a specific drug, analysts will look at metrics such as:

- Peak Annual Sales: What was the highest revenue the brand achieved?

- Current Sales Trajectory: Are sales still growing, or have they plateaued or started to decline?

- Prescription Volume: How many prescriptions are filled annually? This is a key indicator of the potential volume for a generic.

- Patient Population: What is the size of the patient population being treated, and what are the demographic trends (e.g., an aging population for a chronic disease)?

The Price Erosion Curve: Predicting Profitability

Sizing the brand market is only the first part of the equation. A common and costly mistake is to assume that a generic will capture a share of the brand’s revenue. The reality is that a generic captures a share of the brand’s volume at a dramatically lower price. Therefore, the most critical part of the financial analysis is to accurately model the price erosion curve.

Profitability depends not on the brand’s price, but on the stabilized generic price after competition sets in. This erosion is directly and predictably correlated with the number of competitors in the market.

- The First Entrant Advantage: The first generic to market, especially one with 180-day exclusivity, experiences the slowest price erosion and captures the most value.24

- The Competitive Collapse: With the entry of a second and third competitor, prices begin to fall rapidly. An FDA analysis found that with two generic manufacturers, the price drops to about 52% of the brand’s price.

- Commoditization: Once four or more generic manufacturers are in the market, substantial price reductions are achieved. In markets with 10 or more competitors, the price can plummet by 80-90%, reaching commodity levels where only the most efficient manufacturers can remain profitable.

A robust financial model must forecast the likely number of competitors at launch and over the first few years to project a realistic price and, consequently, a realistic revenue and profit forecast.

Qualitative Analysis: Beyond the Numbers

A positive financial forecast is necessary, but not sufficient. The next step is to assess the qualitative barriers that will determine the actual level of competition. The most lucrative opportunities often lie at the intersection of high market value and high technical or legal barriers, as these barriers naturally limit the number of players who can enter the field.

Assessing Formulation and Manufacturing Complexity

Not all generic drugs are simple pills. A growing and increasingly profitable segment of the market consists of complex generics. These are products that are difficult to develop and manufacture, such as:

- Long-acting injectables

- Metered-dose inhalers

- Transdermal patches

- Ophthalmic emulsions

- Liposomal drug delivery systems

These products present significant scientific and technical challenges. Replicating them requires specialized expertise, sophisticated manufacturing facilities, and advanced analytical capabilities to demonstrate equivalence.37 For example, a generic manufacturer must master not only the sameness of active and inactive ingredients (Q1/Q2 assessment) but also the complex physical and structural characteristics (Q3 assessment) that determine the drug’s performance.

These high barriers to entry act as a natural deterrent to competition. While the R&D investment is greater, the reward is a more defensible market position. A company that can successfully develop a generic version of a complex drug is likely to face only a handful of competitors, or perhaps none at all for a period, leading to much slower price erosion and sustained profitability. This creates lucrative, low-competition niches for companies that build a core competency in a specific complex technology.

Analyzing the Competitive and Legal Landscape

The final layer of vetting involves a deep dive into the competitive and legal environment using intelligence tools like those previously discussed. The key questions to answer are:

- How many competitors are already in the race? A search of public databases and intelligence platforms can reveal how many ANDAs have already been filed for the target drug.

- Has the 180-day exclusivity been claimed? Identifying if a “first-to-file” applicant with a Paragraph IV certification already exists is critical. If so, any subsequent filer knows they will have to wait an additional six months to enter the market.

- How strong is the patent thicket? A thorough analysis of the brand’s patent portfolio is required. Are the secondary patents strong and well-drafted, or are they vulnerable to an invalidity challenge? What is the litigation history of the innovator company? Are they known to be aggressive litigants or are they more likely to settle?

By combining these quantitative and qualitative analyses, a company can build a sophisticated opportunity assessment model. The ideal target is not necessarily the biggest blockbuster, but rather a product in the “sweet spot”: one with substantial brand sales but also with significant formulation complexity or a challenging patent landscape that will deter the majority of competitors. This strategic selection process is the first and most important step in building a profitable and sustainable generic drug portfolio.

Section 7: The Development Gauntlet: Navigating Formulation, Bioequivalence, and the ANDA Process

Once a high-potential target has been identified, the race to market begins in earnest. The generic drug development process, while “abbreviated,” is a technical and regulatory gauntlet. It is a journey that demands precision in the laboratory, rigor in clinical testing, and perfection in the final regulatory submission. Success hinges on flawlessly executing three critical phases: formulation, bioequivalence testing, and the assembly and submission of the ANDA dossier.

The Art of Replication: Formulation and De-formulation

The development journey begins not with invention, but with meticulous replication. The first task for the R&D team is a process known as de-formulation, which involves reverse-engineering the brand-name Reference Listed Drug (RLD).42 Since the innovator’s proprietary manufacturing processes and full formulation details are trade secrets, the generic scientist must work like a detective, using advanced analytical techniques to dissect the RLD and identify its every component.

The goal is to understand the drug’s Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs)—the physical, chemical, biological, and microbiological properties that must be controlled to ensure the desired product quality. This includes identifying not only the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) but also all the inactive ingredients, or excipients, that give the drug its form, stability, and release characteristics.

Based on this analysis, the team then develops its own formulation. For many types of products, particularly parenteral (injectable), ophthalmic (eye), and otic (ear) drugs, the regulatory standard is stringent: the generic formulation must be Q1/Q2 the same as the RLD.

- Q1 (Qualitatively the same): The generic must contain the exact same inactive ingredients as the brand.

- Q2 (Quantitatively the same): Each of those inactive ingredients must be present in the same concentration as in the brand, typically within a very narrow range (e.g., 95-105%).

Achieving Q1/Q2 sameness is a significant technical challenge that forms the foundation of proving that the generic product is a true pharmaceutical equivalent to the brand.

The Scientific Cornerstone: Proving Bioequivalence (BE)

This is the scientific heart of the ANDA and the most critical, pass/fail hurdle in the development process. The generic manufacturer must scientifically demonstrate that its product is bioequivalent to the RLD. In simple terms, this means the generic drug works in the body in the same way and to the same extent as the brand-name drug.21

For most systemically-acting oral drugs, bioequivalence is established through a clinical study, typically involving 24 to 36 healthy volunteers. In the study, volunteers are given either the generic drug or the brand-name drug, and blood samples are taken at regular intervals to measure the concentration of the drug in their bloodstream over time.

The key pharmacokinetic (PK) parameters measured are:

- AUC (Area Under the Curve): This represents the total exposure of the body to the drug.

- Cmax (Maximum Concentration): This represents the peak concentration the drug reaches in the bloodstream.

To be deemed bioequivalent by the FDA, the statistical analysis of the study data must show that the 90% confidence interval of the geometric mean ratio (Test/Reference) for both AUC and Cmax falls entirely within the acceptance range of 80.00% to 125.00%. This is a strict statistical standard that ensures the generic and brand products are, for all practical purposes, interchangeable.

While it is a scientific requirement, the BE study is also a major source of project risk and timeline uncertainty. A well-designed formulation can still fail a BE study due to unforeseen biological variability in how the drug is absorbed. Such a failure is a major setback, costing not only the significant expense of the study itself but, more importantly, causing delays of months or even years. In the race to be the first generic to market, a BE failure can be the difference between a blockbuster launch and a missed opportunity. To mitigate this risk, companies are increasingly investing in advanced formulation science and predictive modeling, using technologies like Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) to optimize formulations and predict BE outcomes before committing to the expensive and time-critical human study.42

Assembling and Submitting the ANDA Dossier

The final phase of development is the meticulous assembly and submission of the ANDA dossier to the FDA. This is a comprehensive document that tells the entire story of the generic product’s development and provides all the evidence needed to support its approval. The submission is made electronically through the FDA’s Electronic Submissions Gateway.21

The ANDA dossier is a massive and highly structured submission, containing key sections on:

- Drug Formulation and Composition: Detailed information on all active and inactive ingredients.

- Manufacturing Process and Controls: A complete description of how the drug is manufactured, packaged, and tested to ensure consistency and quality.

- Bioequivalence Data: The full clinical study report and statistical analysis from the pivotal BE study.

- Stability Data: Reports from stability testing to demonstrate that the drug maintains its quality and purity over its proposed shelf life.

- Labeling: The proposed labeling for the generic drug, which must be identical to the RLD’s labeling (with certain permissible differences).

- Patent Certifications: The required certifications for all patents listed in the Orange Book for the RLD.

Upon receipt, the FDA conducts a multi-phase review. This includes a scientific evaluation of the formulation and BE data, a detailed review of the manufacturing processes and facility inspections to ensure compliance with Current Good Manufacturing Practices (cGMP), and a review of the labeling. As noted, this entire process typically takes around 30 months, although the FDA may expedite the review for “priority” generics, such as those for drugs in shortage or first generics that offer new competition.21 A complete, well-documented, and flawlessly assembled application is crucial to avoiding delays and ensuring the fastest possible path to approval.

Section 8: The Supply Chain Imperative: Best Practices for API Sourcing and Manufacturing Scale-Up

A successful generic drug launch is not just about winning in the lab or the courtroom; it’s about winning in the factory and the global logistics network. The supply chain is the backbone of any pharmaceutical operation, and for generics—where success is defined by cost-efficiency, quality, and reliability—it is a critical strategic pillar. In an increasingly volatile world, a resilient and well-managed supply chain has evolved from an operational necessity into a powerful competitive advantage.

The Heart of the Matter: Strategic Sourcing of Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs)

The Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) is the therapeutic core of any drug. The decision of where and how to source this critical raw material is one of the most important a generic company will make, with profound implications for cost, quality, and supply security.

Best practices for strategic API sourcing include:

- Rigorous Supplier Qualification: The foundation of a secure supply chain is a reliable partner. Potential suppliers must be thoroughly vetted for their adherence to quality standards, including current Good Manufacturing Practices (cGMP) and ISO certifications. This involves demanding full traceability documentation, such as Certificates of Analysis (CoA) for each batch, and conducting on-site audits of their manufacturing facilities.

- Geographic Diversification: The COVID-19 pandemic laid bare the significant risks of over-reliance on a single geographic region for critical materials. With approximately 70-80% of India’s API requirements met by imports from China, the entire global supply chain is vulnerable to disruptions from a single point of failure.46 A best practice is to diversify the supplier base geographically, establishing relationships with qualified manufacturers in different regions, such as India, China, and Europe, to mitigate risks from geopolitical tensions, natural disasters, or trade disputes.45

- Building Long-Term Partnerships: Moving beyond a purely transactional relationship to a strategic partnership with key suppliers is essential. Building long-term relationships fosters trust, promotes stability, and can lead to preferential treatment, better pricing, and collaborative innovation. Open and clear communication channels are vital for discussing requirements, timelines, and proactively addressing potential challenges.

- Dual Sourcing: For critical products, relying on a single supplier, even a highly qualified one, is a significant risk. A dual-sourcing strategy, where a company qualifies and maintains active relationships with at least two independent API suppliers, is a key tactic for ensuring business continuity.

From Lab Bench to Commercial Scale: The Manufacturing Scale-Up Process

Once the formulation is finalized and the API source is secured, the next major operational hurdle is manufacturing scale-up. This is the complex process of transitioning from producing small batches in a laboratory setting to manufacturing the drug at full commercial scale, potentially involving millions of tablets or capsules per batch.49

This process is governed by the FDA’s Scale-Up and Post-Approval Changes (SUPAC) guidance, which provides a framework for managing changes to manufacturing without negatively impacting the product’s quality or performance. The key stages include:

- Laboratory Scale: Initial development occurs on a small scale, allowing for process optimization without the high cost and risk of large-scale production.

- Pilot Scale: This is a crucial intermediary stage. The process is scaled up to a level that is fully representative of the final commercial process. For solid oral dosage forms, this is generally defined as at least one-tenth of the full production scale, or 100,000 units (tablets/capsules), whichever is larger. This stage is used to fine-tune the process, identify potential issues, and produce the pivotal batches for stability testing and, most importantly, the bioequivalence study.

- Commercial Scale: The final stage involves scaling the process to its full production volume.

Throughout this process, it is absolutely critical to ensure that the drug product manufactured at commercial scale is equivalent to the pilot-scale batch that was used in the successful BE study. Any significant changes in the manufacturing process, equipment, or site post-approval must be carefully documented and reported to the FDA, and may require additional testing to validate the change.49

Managing Supply Chain Risks in a Volatile World

The generic drug supply chain operates under what can be described as an “affordability paradox.” The intense price competition that makes generics affordable also creates extreme pressure on manufacturers to cut costs. This can lead to underinvestment in robust infrastructure and supply chain redundancy, creating a system that is efficient but fragile.

In today’s geopolitical landscape, this fragility is a major strategic liability. Supply chain management is no longer a back-office function focused solely on cost optimization; it has become a core pillar of corporate strategy and national security. The widespread drug shortages seen in recent years are a direct consequence of these vulnerabilities.43

Effective risk management strategies are therefore essential:

- Enhanced Visibility and Monitoring: Implementing advanced technologies to gain real-time visibility into the entire supply chain, from raw material sourcing to final distribution. This allows for the early detection of potential disruptions.

- Rigorous Vendor Risk Assessment: Going beyond quality audits to include assessments of a vendor’s financial health, cybersecurity posture, and operational resilience. High-risk vendors should be reviewed annually.

- Strategic Planning and Redundancy: In addition to diversifying suppliers, companies should develop detailed contingency plans for various disruption scenarios (e.g., a natural disaster at a key supplier site, the imposition of new trade tariffs). This may include maintaining strategic reserves of critical APIs or finished products.

Companies that invest in supply chain resilience—even if it means accepting slightly higher costs through dual-sourcing or onshoring some manufacturing—can market themselves as more reliable suppliers. In a post-pandemic world, large purchasers like hospital systems and government health agencies are increasingly prioritizing supply security over the absolute lowest price. A robust, transparent, and resilient supply chain is rapidly becoming a key commercial differentiator, transforming an operational function into a powerful competitive advantage.

Section 9: Go-to-Market Playbook: Advanced Pricing, Marketing, and Market Access Strategies

Securing FDA approval for a generic drug is a monumental achievement, but it is only the halfway point. The ultimate success of a launch is determined in the commercial arena. Winning in the marketplace requires a sophisticated and integrated go-to-market strategy that encompasses intelligent pricing, targeted multi-stakeholder marketing, and a clear plan for securing market access. This is where scientific achievement is translated into commercial success.

The Science of Pricing: Beyond Cost-Plus

Pricing a generic drug is a delicate balancing act. Price too high, and you lose the fundamental generic advantage. Price too low, and you leave value on the table and may even signal poor quality. The strategy must move beyond a simple cost-plus calculation to reflect the complex dynamics of the market, competition, and regulatory environment. Advanced pricing models include:

- Market-Based Pricing: The most common approach, where the price is set by closely monitoring and reacting to the prices of competitors already in the market. This is a reactive strategy but essential for staying competitive.

- Volume-Based Pricing: This strategy involves offering discounts for large-volume purchases, a key tactic for winning contracts with major distributors, pharmacy chains, and hospital purchasing organizations. It leverages economies of scale to secure market share.

- Reference Pricing: In many international markets and increasingly influential in the U.S. through payer strategies, reference pricing sets a standard reimbursement level for a group of interchangeable drugs (e.g., all generic versions of atorvastatin). This forces manufacturers to compete on price to be at or below the reference price to ensure patient access and reimbursement.

- Tiered Pricing Models: A more dynamic approach where the maximum allowable price is linked to the number of competitors in the market. For instance, a model might allow the first generic entrant a higher price, with mandated price reductions as a second, third, and fourth competitor enter. This model seeks to balance the incentive for early market entry with the goal of long-term cost reduction.

- Value-Based Pricing: Traditionally the domain of innovative branded drugs, the principles of value-based pricing—linking price to a product’s effectiveness and benefits—are becoming relevant for complex generics or biosimilars. A generic that offers a significant advantage, such as an improved delivery device or a formulation with fewer side effects, may be able to command a price premium based on that added value.54

A Multi-Stakeholder Marketing Approach

Marketing a generic drug is fundamentally different from marketing a brand. The goal is not to create patient demand from scratch, but to convince a chain of professional stakeholders that your product is the most logical, reliable, and cost-effective choice to substitute for the brand. A successful launch requires a coordinated campaign targeting the three key gatekeepers of the healthcare system: payers, prescribers, and pharmacists.56

- Targeting Payers (Insurers and PBMs): This is arguably the most critical audience. Payers hold the purse strings and determine a drug’s formulary status, which dictates the patient’s out-of-pocket cost. The marketing message to payers is purely economic: highlight the significant cost savings your generic offers compared to the brand and other generics. Early engagement, often months before the anticipated launch, is crucial to negotiate favorable formulary placement on a low copay tier.57

- Targeting Prescribers (Physicians): While physicians are highly motivated by cost savings for their patients, their primary concern is clinical confidence. The marketing message to prescribers must emphasize quality and trust. This involves providing clear data on bioequivalence, highlighting the manufacturer’s reputation for quality, and ensuring a reliable supply to prevent disruptions that could affect their patients’ care.

- Targeting Pharmacists and Pharmacy Chains: Pharmacists are on the front lines of generic substitution. They need to be confident in the product’s quality and, just as importantly, its availability. A robust and reliable supply chain is a key selling point for major pharmacy chains like CVS or Walgreens. Offering competitive pricing, volume discounts, and co-marketing support can help secure shelf space and make your product the preferred generic for dispensing.

In the modern era, these targeted campaigns are increasingly executed through efficient digital marketing tactics. SEO-optimized content, targeted advertising on professional networks, and educational webinars can amplify reach to these key stakeholder groups far more cost-effectively than traditional sales forces.

Securing Market Access: The Final Hurdle

Market access is the culmination of the pricing and marketing strategy. It is the process of ensuring that once a drug is approved, it is actually available and affordable for patients. The primary lever for market access is securing a favorable position on payer formularies.

A drug placed on a “Tier 1” or “preferred generic” tier will have the lowest possible patient copayment. This creates a powerful incentive structure that flows through the entire system. A low copay encourages patients to accept the generic, which in turn encourages physicians to prescribe it and pharmacists to dispense it. Conversely, being placed on a higher tier can be a significant barrier to uptake, even if the generic’s wholesale price is low.

This is why a successful launch strategy cannot focus on a single stakeholder. It must create a “value triangle” where the incentives for payers (cost savings), prescribers (clinical confidence and patient affordability), and pharmacists (profitability and supply reliability) are all aligned. A low price alone is not enough. If the product isn’t on the formulary, if doctors don’t trust it, or if the supply is unreliable, the launch will fail. Winning requires a holistic strategy that solves the problems of all three key stakeholders simultaneously.

Section 10: The Next Frontier: Seizing Opportunities in the Complex World of Biosimilars

As the wave of patent expirations for traditional small-molecule drugs continues, a new and even more lucrative frontier is opening up: biologics. These complex, high-cost therapies for diseases like cancer and autoimmune disorders represent a massive market. However, creating follow-on versions of these drugs is a fundamentally different and more challenging endeavor. These products are not “generics”; they are biosimilars, and they operate under a unique set of scientific, regulatory, and commercial rules.

Generics vs. Biosimilars: A Fundamental Distinction

The most critical concept to grasp is that a biosimilar is not a generic. The difference lies in the nature of the molecules themselves.59

- Generic Drugs are copies of small-molecule drugs. These are relatively simple chemical compounds (like aspirin or atorvastatin) that are synthesized through predictable chemical reactions. As a result, a generic manufacturer can create a copy that is identical in its active ingredient to the original brand-name drug.59

- Biosimilars are copies of biologic drugs. Biologics are large, complex molecules—often proteins like monoclonal antibodies—that are produced in living systems such as yeast, bacteria, or animal cells.60 Because they are made in living organisms, there is inherent, natural variability from batch to batch. It is scientifically impossible to create an exact, identical copy of a complex biologic. Therefore, a follow-on product can only be proven to be

“highly similar” to the original, with no clinically meaningful differences in safety, purity, and potency. This is a biosimilar.61

This fundamental distinction has profound implications for every aspect of development, regulation, and commercialization.

The BPCIA: A Unique Regulatory Pathway

Recognizing the unique nature of biologics, the U.S. Congress passed the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA) in 2009. This law created a new, abbreviated approval pathway for biosimilars, codified under section 351(k) of the Public Health Service Act.65

This pathway is far more demanding than the ANDA process for generics. Instead of simply proving bioequivalence with a small PK study, a biosimilar applicant must demonstrate biosimilarity through a comprehensive “totality of the evidence” approach.65 This involves a step-wise process:

- Extensive Analytical Characterization: This is the foundation of a biosimilar application. The applicant must use a battery of sophisticated analytical techniques to compare the structural and functional characteristics of their proposed biosimilar to the reference biologic, demonstrating that they are highly similar.63

- Animal Studies: Non-clinical studies in animals may be required to provide data on toxicology and pharmacology.

- Clinical Pharmacology Studies: Human studies are required to compare the pharmacokinetics (PK) and, if appropriate, pharmacodynamics (PD) of the biosimilar and the reference product.

- Additional Clinical Studies: The FDA may require a comparative clinical immunogenicity assessment and, in some cases, additional clinical studies to address any residual uncertainty about the safety and effectiveness of the biosimilar.67

This process is significantly more complex, time-consuming, and expensive than generic development. Developing a biosimilar can take 7 to 8 years and cost between $100 million and $250 million, compared to $1-$4 million for a typical generic.63

Market Entry Challenges and Opportunities

The high barriers to entry for biosimilars create a market with unique challenges and opportunities. The competitive landscape is vastly different from the small-molecule generic space.

- Manufacturing Complexity: The expertise required to reliably manufacture large, complex proteins in living cell cultures is a massive barrier. Only companies with deep experience in biologics manufacturing can realistically compete.

- The “Patent Dance”: The BPCIA created a complex, multi-step process for resolving patent disputes between the biosimilar applicant and the reference product sponsor, known colloquially as the “patent dance.” Navigating this intricate legal framework is a significant challenge.

- Lack of Automatic Substitution (Interchangeability): This is a crucial market difference. A pharmacist cannot automatically substitute a biosimilar for a prescribed biologic in the way they can with a generic. Automatic substitution is only permitted if a biosimilar has achieved a separate and higher regulatory standard of “interchangeability.” To achieve this, the manufacturer must conduct additional studies, often including a “switching study,” to prove that alternating between the reference product and the biosimilar poses no additional risk or diminished efficacy compared to staying on the reference product alone.65

- Physician and Patient Acceptance: Because there is no automatic substitution for most biosimilars, gaining market share requires convincing physicians to actively prescribe the biosimilar. This requires a significant marketing and educational effort to build trust and confidence in the product’s safety and efficacy.64

Despite these formidable hurdles, the opportunity is immense. Biologics account for a disproportionately large share of prescription drug spending—in 2015, they were 38% of U.S. spending despite being used by only 1-2% of the population. The introduction of biosimilars is projected to save the U.S. healthcare system tens of billions of dollars over the next decade, with some estimates projecting savings of $54 billion from 2017 to 2026. As more biosimilars enter the market, they are increasing patient access to these life-changing therapies.68

The biosimilar market represents a strategic convergence of the generic and branded pharma business models. To succeed, a company needs the cost-conscious manufacturing efficiency and regulatory savvy of a top-tier generic player, combined with the clinical development capabilities and sophisticated physician marketing apparatus of a branded pharmaceutical company. This creates a new competitive arena where pure manufacturing prowess is not enough. The companies best positioned to win are either large, well-capitalized generic firms willing to invest heavily in these new capabilities, or established branded pharma companies that are entering the biosimilar space as a new, synergistic business line.

Table 3: Generics vs. Biosimilars: A Comparative Analysis

| Attribute | Small-Molecule Generics | Biosimilars |

| Molecule Type | Small, simple chemical structures | Large, complex proteins/biologics |

| Manufacturing Process | Chemical synthesis (predictable, replicable) | Produced in living cells (inherently variable) |

| Regulatory Standard | Identical (pharmaceutically equivalent) | Highly Similar (no clinically meaningful differences) |

| Approval Pathway | ANDA (Abbreviated New Drug Application) | 351(k) BLA (Biologics License Application) |

| Key Scientific Proof | Bioequivalence (BE) study | Totality of the Evidence (Analytical, Animal, Clinical) |

| Development Cost | $1 – $4 Million | $100 – $250 Million 63 |

| Development Timeline | ~2 – 4 years | ~7 – 8 years |

| Interchangeability | Automatic substitution at the pharmacy | Requires separate “interchangeable” designation and additional studies |

| Market Barriers | Lower; primarily patent litigation | Very high; manufacturing complexity, high cost, legal hurdles |

Section 11: Expanding Horizons: A Strategic Look at International Generic Markets

While the United States is the largest and most lucrative pharmaceutical market, a truly successful generic strategy must be global in scope. However, expanding internationally requires a deep understanding that each major market operates under its own unique “regulatory and economic fingerprint.” A strategy that excels in the litigation-driven U.S. market may be entirely ineffective in the price-controlled environments of Europe or Japan. Success requires a portfolio of tailored, region-specific strategies.

Navigating the European Union: A Harmonized but Fragmented Market

The European Union represents a massive and sophisticated market for generic and biosimilar medicines. The regulatory framework is largely harmonized under the oversight of the European Medicines Agency (EMA), which works in a network with the national regulatory authorities of the member states.

- Regulatory Pathways: Like the U.S., the EU offers several pathways for drug approval. The centralized procedure allows a company to submit a single application to the EMA to obtain a marketing authorization that is valid in all EU member states. This is compulsory for most innovative medicines, including biologics. For generics, companies can also use decentralized or national procedures to gain approval in multiple or single countries. The scientific requirement for generic and biosimilar approval is fundamentally similar to the U.S.: demonstrating equivalence or biosimilarity to the originator product, which is known as the “reference medicinal product”.

- The Fragmentation Challenge: The primary challenge in Europe is that while drug approval can be centralized, pricing and reimbursement decisions are not. Each of the 27 member states has its own national health system and makes its own decisions about how much it will pay for a drug and whether it will be reimbursed. This creates a complex and fragmented patchwork of market access hurdles. A generic company must engage in separate negotiations with the national authorities in Germany, France, Italy, Spain, and so on, each with its own pricing rules and health technology assessment (HTA) bodies.

- Market Pressures: The European generic market is facing significant economic pressures. A combination of stringent pricing policies, new regulatory requirements, and supply chain consolidation is reducing the economic viability of many older, critical generic medicines. In some cases, this has led to suppliers withdrawing products from the market, creating a risk of drug shortages.

The Japanese Paradox: High Demand Meets Strict Cost Control

Japan is the world’s third-largest pharmaceutical market, a mature, high-income nation with structurally guaranteed demand driven by one of the most rapidly aging populations on Earth. However, this demographic tailwind is met by a powerful headwind: an ironclad government commitment to controlling healthcare expenditure.

- Aggressive Generic Promotion: For over 15 years, the Japanese government has pursued a single-minded policy goal: increasing the use of generic drugs. It has been stunningly successful, using a multi-pronged approach that includes financial incentives for doctors and pharmacists, changing prescription formats to make generic dispensing the default, and even imposing an extra charge on patients who specifically request a brand-name drug when a generic is available. As a result, the generic volume-based usage rate is approaching 90%.