The last five years have seen seismic shifts in how pharmaceutical patent disputes are fought – and the trends have major implications for strategy. Pharma executives must now navigate a patent landscape where generic small-molecule drugs (governed by the FDA’s Orange Book and Hatch-Waxman framework) follow a different playbook than biologics (protected by the Purple Book framework and the BPCIA). In broad strokes, generics dominate prescription volume but wield far less spending power (90% of US prescriptions vs only ~18% of drug spending), underscoring why brand owners fiercely defend their patent fortresses. Turning those data into market advantage means understanding the latest patent-challenge trends. Over the past half-decade, Orange Book patent challenges have cratered, while challenges to biologic patents via PTAB (IPRs and PGRs) are rising. This article drills into what the stats tell us – and how your company should adapt to win in this new game.

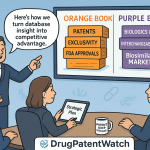

To set the stage, recall that the Orange Book is the FDA’s official register of patents and exclusivities on approved small-molecule drugs. It “provides a wealth of detailed information on small-molecule drugs, including comprehensive patent listings, patent use codes, and various regulatory exclusivities”. It is literally the cornerstone for generic drug approvals, guiding ANDA applicants on which patents to challenge or design around. By contrast, biologics (large molecule therapies) are listed in the FDA’s Purple Book, which currently focuses on product licensure and exclusivity rather than patent details. Biologics also use the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA) patent dance rather than automatic Orange Book linkage. In practice, this means brands and biosim innovators use a different set of patents (often manufacturing or formulation patents) and different legal tools.

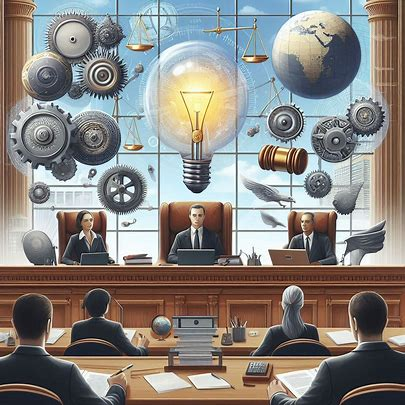

Yet, both categories intersect with the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) via IPR (Inter Partes Review) and PGR (Post-Grant Review) petitions. Over time, PTAB data (compiled by the USPTO and industry firms) reveal stark differences. For example, a recent USPTO analysis shows that only about 3% of all AIA (America Invents Act) petitions to date target Orange Book patents, whereas biologic patents account for roughly 2%. Orange Book petitions, which peaked at over 100 per year in 2015-2016, have fallen sharply – now under 2% of petitions, an 80% drop from FY2016 to today. Biologic patent petitions, on the other hand, dipped after 2017 but have recently climbed back (e.g. 8 petitions in FY2020 to 38 in FY2023). In short, generic (small-molecule) IPRs are off the boil, while biosimilar IPRs are heating up.

This article will unpack those trends: charting the decline of Orange Book PTAB litigation, the rise of biologic PTAB battles, and the “why” behind these shifts. Along the way, we’ll compare the two patent strategies side-by-side, use expert quotes and real-world examples (from AbbVie’s Humira to global regulatory models), and translate the data into actionable strategy tips. By the end, you’ll have clear takeaways on how to leverage patent data and litigation trends for competitive advantage – truly turning data into market domination. Let’s dive in.

The Orange Book Patent Landscape

For decades, the Orange Book has been a critical battleground in the generics-versus-brands wars. Every approved small-molecule drug (NDAs under 505(b)) has an Orange Book entry listing patents covering the active ingredient, formulations, and approved method-of-use claims. These listings not only reveal patent expiration dates but also gatekeep 180-day exclusivity for the first generic filer who challenges a patent (“Paragraph IV”). In fact, the Orange Book “serves as the cornerstone for navigating the generic drug approval pathway”. Brand owners carefully craft their Orange Book portfolios to block generics – but generic companies likewise scour it to plan their challenge strategies.

Over the past five years, the role of Orange Book patents in PTAB litigation has been diminishing. This partly reflects the success of older patents and the maturity of key drug markets: many blockbuster small-molecule drugs had their primary patents expire a while ago, so fewer new blockbuster Orange Book patents exist to challenge. The patent listing rules themselves exclude process and formulation patents in many cases, focusing only on certain claim types. Generics sometimes find more value in litigating in district courts under Hatch-Waxman (for favorable settlements or 180-day exclusivities) than pursuing PTAB.

Nevertheless, for strategy it’s crucial to note the steep decline in PTAB use. The USPTO reports that Orange Book-listed patent challenges have fallen from 7.5% of AIA petitions in FY2016 to under 2% today – an 80% drop. In absolute terms, that’s gone from over 100 PTAB petitions per year to only a few dozen. The vast majority of those few remaining Orange Book proceedings are IPRs (Inter Partes Reviews); PGRs (Post-Grant Reviews) against Orange Book patents are virtually nonexistent in recent years. In other words, the practice of using the PTAB to invalidate small-molecule patents has cooled off dramatically.

Why? One key reason is outcome experience: historically, Orange Book patents have had relatively good survival rates. When taken to final decision, many Orange Book challenges end with all claims upheld. For instance, one analysis noted that about 21% of PTAB challenges to Orange Book patents resulted in all claims deemed patentable – far higher than for biologics. In practice, this means generics may have concluded that PTAB isn’t the most efficient use of resources when success rates are lower than expected. Instead, they might negotiate settlements or seek statutory exclusivities via the 180-day window in district court.

At the same time, new laws have started to affect Orange Book listings. The 2020 Orange Book Transparency Act (now fully implemented) and FDA guidance have tried to prevent over-listing of frivolous patents. Recent FTC scrutiny also discourages improper Orange Book listings. These changes mean the Orange Book may now reflect fewer marginal patents. For business strategy, this implies generic R&D teams need to look beyond the Orange Book (e.g. at manufacturing or late-added patents) to fully map the IP landscape. Brand teams, conversely, must ensure their core Orange Book patents are bulletproof against any form of challenge.

From a business standpoint, the decline in Orange Book IPRs suggests companies should reevaluate how they use patent data. For example, generics may rely more on analytics and scouting to find niches (skinny labels, exclusive switching opportunities) rather than broad PTAB campaigns. Meanwhile, brand companies can view a lighter PTAB docket as a chance to tighten up patents and perhaps even divest weaker patents that no longer provide strategic value.

The Biologic Patent Ecosystem

Biologics have their own patent landscape. Unlike small molecules, biologics and biosimilars do not use the Orange Book. Instead, the FDA’s Purple Book provides information on approved biological products (reference products and biosimilars), including licensed exclusivities and whether a product is biosimilar or interchangeable. (As of 2023, a new requirement – the Biological Product Patent Transparency (BPPT) provision – requires originators to publish patent lists, which may eventually feed into Purple Book entries.) In practice, biologic patent strategies pivot around the BPCIA patent dance, which is a structured disclosure between a biosimilar applicant and the reference product sponsor, and often parallel litigation.

From a technical standpoint, biologic patents often claim complex matter such as engineered protein sequences, formulations, and especially manufacturing processes. These process patents (cell lines, purification methods, dosing devices) form a web of protection – often dubbed a “patent thicket”. In fact, one recent analysis describes biologic thickets as overlapping claims on formulation, manufacture and devices that can delay market entry by 2.5 to 16.5 years compared to Europe. AbbVie’s Humira® is the poster child: it assembled ~130 US patents around the drug. That fortress of patents kept Humira’s US biosimilar entry locked until 2023, seven years after its core patent expiry. (A legislative example: S.150, the Affordable Prescriptions for Patients Act, directly targets that tactic by capping patent assertions on a biologic at 20 per product.)

Biologic patents are now being challenged at the PTAB with increasing frequency. The first wave of biosimilars arrived in the mid-2010s (e.g. Zarxio in 2015), so we are only now seeing significant PTAB activity as more biosimilars seek to clear hurdles. According to USPTO data, biologic patents have accounted for about 2% of all AIA petitions to date. That’s a modest share, but unlike Orange Book filings it’s trending upward: from only 8 biologic petitions in FY2020 to 38 in FY2023. In percentage terms, biologics rose from ~0.5% of all petitions in 2020 to over 3% by 2023. This resurgence has even outpaced Orange Book challenges since FY2021.

What kinds of petitions are these? Interestingly, biologic patent challenges disproportionately use PGRs. PGR is available only within one year of patent grant, and allows validity challenges on any ground (including written description) as opposed to IPR’s narrower prior art scope. The data show that biologics dominate the PGR docket: about 90% of all PGR petitions to date have been against biologic patents. Biologic inventions often hinge on intricate biotechnologies where written-description or enablement are key vulnerability points. By filing a PGR immediately after a patent issues, challengers can exploit these weaknesses early. In contrast, nearly all Orange Book challenges are IPRs; very few PGRs target older small-molecule patents. As one report notes, “[b]iologic patents have been the subject of about 90% of all PGR petitions filed”, making PGR an unusual focus of biologic strategy.

Outcomes for biologic patent PTABs also paint a distinct picture. Institution rates for biologics are roughly on par with Orange Book – around 60%. (USPTO data: ~61% biologic, ~62% Orange Book.) However, once a biologic IPR/PGR is instituted, patentees fare worse than in small molecules. On a patent level, only about 7% of biologic patent proceedings result in all claims surviving, compared to roughly 19% for Orange Book patents. In other words, biologic patents rarely emerge unscathed. On a claim-by-claim basis, a full 25% of challenged biologic claims (57% of instituted claims) have been found unpatentable, versus 17% of challenged Orange Book claims. In practice, that means if a biosimilar maker brings an IPR or PGR against a biologic patent and it’s instituted, there’s a strong chance much of that patent will be knocked out. This contrast suggests that biologic patents have structural vulnerabilities at the PTAB – perhaps due to their complexity – and must be defended differently.

From the executive suite perspective, the growing volume and high invalidation rate of biologic PTABs implies that brand owners in the biotech space cannot rely solely on filing new patents. They must invest in truly novel inventions or litigation strategies (see below). For biosimilar developers, it means that PTAB can be an effective pathway to clear dominant patents – one that may even outshine the conventional BPCIA litigation route in some cases. In sum, the dynamics suggest a “do-or-die” attitude: small-molecule players may be coasting, but biotech innovators and challengers must play fast and aggressive to secure market share.

Statistical Snapshot of Orange Book vs. Biologic PTAB Trends

Before we delve deeper, here is a quick bullet snapshot of recent stats to keep top-of-mind (sources: USPTO, Finnegan, DrugPatentWatch):

- Sharp fall in Orange Book challenges: Dropped from ~7.5% of petitions in FY2016 to <2% now (over 80% decline). Total Orange Book petitions yearly peaked ~2015-16, now in single digits per month.

- Biologics climbing: Peaked at 3.9% of petitions (FY2017) and after a dip have rebounded to ~3.1% by FY2023. In number terms, biologic petitions rose from 8 (FY2020) to 38 (FY2023).

- Trial types: Orange Book challenges are ~96% IPR (near-zero PGR). Biologics dominate PGRs (≈90% of all PGRs are biologic).

- Institution rate: Both sit around 60% (58–62%), slightly below the ~64% average for all patents.

- Survival vs invalidation: ~19% of Orange Book patents end up with all claims upheld, whereas only ~7% of biologic patents do. Claim-level: 17% of Orange Book claims invalidated vs 25% of biologic claims.

These figures highlight the strategic divergence: Orange Book patents mostly win at PTAB (many survive intact), while biologic patents often lose.

This juxtaposition suggests that patent strength plays out differently. In effect, you might say the Orange Book environment has been the better “safe harbor” – a brand can often count on some patents emerging unscathed. Biologics, by contrast, face a storm of scrutiny. For business leaders, that means risk assessments must differ: an ANDA filer might budget for a lower chance of full PTAB success (so negotiate settlements), whereas a biosimilar team might more eagerly bet on PTAB invalidating a key patent (since stats favor that).

Comparing Orange Book and Biologic Patent Strategies

The differences in Orange Book vs. biologic PTAB dynamics reflect deeper strategic contrasts:

- Patent Scope: Orange Book only lists patents that directly claim the drug, its formulation or approved use. It excludes many ancillary patents (process, metabolites, off-label uses). By contrast, biologic patent portfolios often include manufacturing and process patents – many of which would not appear in an Orange Book listing. In fact, biologic patent suites often bundle what Orange Book would exclude. As one analysis notes, biologic patents can span “a broader range of patents, frequently including patents directed to manufacturing processes”. The upshot is that biologic patents can be more numerous and layered (a thicket).

- Regulatory Framework: Generics use Hatch-Waxman/ANDA. Under this scheme, the Orange Book listing provides automatic “patent linkage” for generics, plus a 180-day exclusivity for first challengers. Biologics use the BPCIA (a negotiated patent list exchange). Only as of April 2023 did the US require originators to publish a more formal patent list for biologics (via BPPT law). Thus, generic companies have relied on Orange Book intel for decades, while biosim companies are still perfecting how to discover and challenge biologic patents.

- Litigation Pathways: For small molecules, defendants often prefer federal courts, given the 180-day exclusivity carrot. PTAB IPRs are used too, but some infringers skip it if they can get an ANDA filed earlier. Biologics have no 180-day carrot; every biosim case involves a patent dance, followed by parallel litigation. Increasingly, biosim challengers file IPRs/PGRs either alongside BPCIA suits or as standalone challenges. Because biosim litigation is costly and lengthy, any edge at PTAB (favorable invalidity) can be a game-changer.

- Outcomes: In general, Orange Book patents have fared better at PTAB than the average patent – higher institution rates historically, and higher full-survival rates. Biologic patents have tended to fare worse after institution. For example, in outcomes since 2012, ~25% of biologic patent IPRs found all claims unpatentable (vs ~18% of Orange Book), and only ~9% of biologic IPRs found all claims patentable (vs ~21% of Orange Book). These trends suggest that, claim-for-claim, biologic patent challenges yield more invalidations (at least so far).

- Strategic Responses: Brands with Orange Book portfolios may find it cost-effective to drop or limit defending certain patents at the PTAB if they expect failure. Indeed, many Orange Book petitions simply end in denials of institution (41% of OB petitions are denied). Biotech brands might instead pour resources into shoring up their portfolios (e.g. by adding new patents) or diversifying defenses (rely on multiple suits). On the generics/biosim side, each group appears to allocate differently: small-molecule generics might “pick their battles,” while biosim developers throw more weight at PGR to sweep away weak patents early.

Throughout the last five years, firms have taken note of these differences. Analytics firms like DrugPatentWatch emphasize that patent data should drive strategy. For instance, one guide explains that the Orange Book and Purple Book “stand as indispensable resources for conducting thorough drug patent and exclusivity research”. In practice, this means tying real-world patent outcomes into forecasting: if historical PTAB data show biologic patents tend to crumble, a biosim developer might be more aggressive in PTAB filings; conversely, a brand owner might be more cautious before wasting money on defending every patent.

Business Strategy Implications

What do these shifting dynamics mean for pharma executives and strategists? In short: adapt or get left behind. Here are several key takeaways to inform strategic planning:

- Leverage Advanced Data Tools: Rich data sources (like DrugPatentWatch) can help companies translate raw patent filings into strategy. For example, combining Orange Book data, PTAB outcomes, and pipeline info lets an executive anticipate when generics/biosimilars will hit and how fierce the patent fight will be. As one industry resource notes, using both the Orange and Purple Books effectively “enables generic and biosimilar developers to anticipate opportunities to carve out patented uses or avoid infringement.” In practice, this means your teams should not only monitor FDA patent lists but also PTAB trial trends (who’s winning, what claim types are knocked out). Machine learning and analytic dashboards (some provided by services like DrugPatentWatch) can spot weak patents quickly, letting you “cut to the chase” in litigation.

- Reassess R&D and Patent Policies: Companies should evaluate where to invest in patents. For small molecules, filing a large number of process or formulation patents that aren’t Orange Book-eligible might be wasted if generics will never face them via Hatch-Waxman. The old tactic of “file everything” is less attractive if PTAB is unlikely or if regulators delist excess patents. Instead, focus on core inventive claims. For biologics, the bar is high – firms may need to pursue genuinely new platforms or techniques to stay ahead, rather than stacking on every incremental tweak as a new patent. With proposals like S.150 looming (capping patents per biologic at 20), having dozens of overlapping patents may soon yield diminishing returns. In short, quality over quantity: executives should demand strategic portfolio reviews and kill redundant patents, so that the remaining patents are robust.

- Adapt Litigation Tactics: The courts (and PTAB) are part of strategy. Brands should weigh when to settle generics suits versus pressing IPRs. Generics may choose to launch “carve-out” or “skinny” products that respect narrower patents (using Orange Book use codes). A “rhetorical” analogy: treat patents like fortresses on the market. If a wall is collapsing (high PTAB invalidation rate), maybe retreat and fight inside (negotiate), but if it’s holding, send the cavalry (litigate). For biosimilars, the data favor rushing to PTAB: one study found that launching patent challenges during Phase 3 (pre-approval) can slash market-entry delay by ~4.8x compared to waiting for post-approval fights. This strategy – akin to “breaking and entering” the patent fort before the full defenses are up – has paid off. (Indeed, winning early in the EU model hasn’t hurt innovation; as Dr. Sarfaraz Niazi put it, “The European model proves earlier challenges don’t compromise innovation – they create smarter IP ecosystems.”.)

- Monitor and Shape Regulation: US regulators are keenly focused on these dynamics now. Rules on Orange/Purple Book listings, 180-day exclusivity eligibility, and biosim trial design (the so-called “patent dance”) can all shift advantage. For example, the recent push to increase transparency in Purple Book patent listings may narrow uncertainty for biosim companies. Executives should engage in advocacy (like supporting policies that accelerate biosim entry if they’re on that side) or guard against unfavorable rules (if they represent originators). Keep an eye on international trends too: the US is looking at EU and Japan models, where biosim patent challenges are allowed during clinical trials. Being proactive on policy – rather than reactive – is part of good strategy.

- Case Study – Humira (Lessons Learned): AbbVie’s Humira saga is a cautionary and instructive tale. By aggressively patenting everything from dosage forms to devices, AbbVie erected a 130-patent thicket around Humira. This kept the brand unchallenged in the US until 2023, years beyond original expectations. But it also drew legislative fire and delayed the brand’s own momentum (as resources went into patent wars). When biosimilars finally launched, AbbVie had spent billions and seen Congressional responses. The lesson: a patent war can buy time, but it also invites countermeasures and delays ROI. Today, with changes like the 2023 180-day provisions and possible patent caps, future blockbuster biologics likely won’t see a repeat of the Humira playbook. Executives should learn from AbbVie: build a robust, but not endless, defense. Ensure your patent castles have strong foundations, not just sprawl.

- Generics/Biosim Strategy – Seizing the Moment: On the attacking side, generic and biosim makers should align R&D and legal teams. Using analytics, identify the patents most likely vulnerable (e.g. those that were granted right before filing or with narrow claims). Then plan petition filings in lockstep with development milestones. As the data show, winning at PTAB can dramatically shorten entry. For instance, in one analysis, biosimilars that invalidated key patents saw their market penetration skyrocket (84% of the market within 12 months). That’s the kind of payoff “data into domination” can deliver. Conversely, even if a patent fight looks tough, use the time to secure other pathways (like launching “authorized biosimilars” or seeking alternative indications).

Global Harmonization and Future Outlook

Looking forward, these trends are only the beginning of a changing global patent tapestry. The US is gradually moving toward approaches that align more with Europe and Japan, encouraging earlier challenges and collaborative regulatory review. Congress is considering bills to impose patent assertion limits (as mentioned) and require better patent listing disclosure. Biotech manufacturing advances (continuous processing, single-use systems, AI cell-line development) are also quietly circumventing traditional patent thickets by taking biologic production in new directions.

In practical terms: imagine the life sciences patent landscape as a shifting chessboard. A few years ago, the Orange Book pawns were strong and plentiful; now many have been traded off. Meanwhile, the biologic pieces are on the rise but under intense attack. The key to market domination is to play this chessboard skillfully – anticipating the next moves of regulators and competitors. One way to frame it: patent strategy is not just legal work, it’s business intelligence. As one data-driven source puts it, mastering the Orange and Purple Books, and integrating them with PTAB data, “can significantly enhance… strategic decision-making”.

It’s worth repeating the quote from Dr. Niazi to leave an image in mind:

This underscores that opening the gates early (with data and legal tools) need not kill innovation; instead, it forces companies to have smarter patents and smarter products. Pharma leaders should take this to heart: use the last five years of data as a guide, but prepare for even faster change ahead.

Key Takeaways

- Orange Book patent challenges have plunged since 2016 (80% drop). Generics see fewer IPR opportunities, likely due to strong brand patents and alternative strategies.

- Biologic PTAB cases are rising. The share of PTAB petitions against biologics has grown, reflecting the expanding biosim pipeline. Executives should expect more IPR/PGR for biotech in coming years.

- Institutions rates ~60% for both Orange Book and biologics (slightly below the norm). But biologics fare worse post-institution: a larger portion of biologic claims are invalidated.

- Biologic patents are often challenged via PGR (written-description ground), whereas Orange Book patents are nearly all IPRs. Strategy: file early against biologic patents, with broader grounds.

- Patent strengths differ: historically, Orange Book patents have had higher survival (21% of OB cases keep all claims vs 9% for biologics). Biotech patents tend to have more weakness at PTAB.

- Business implication: Brand teams should audit and fortify their core patents (quality > quantity). Generic and biosim teams should use patent analytics to focus on the weak points.

- Regulatory change matters: Stay alert to new rules (e.g. Purple Book disclosures, exclusivity tweaks). Legislative proposals (like capping biologic patents per product) could soon alter the game.

- Global insights: Consider successful foreign models (EU allows early challenges). As Dr. Niazi observes, early contestation can improve the IP ecosystem, benefiting both innovators and the public.

By converting these insights into action – e.g. refining R&D priorities, targeting the right legal challenges, and continuously mining patent data – pharma executives can turn intellectual property data into actual market advantage.

FAQs

- Q: Why have PTAB petitions for Orange Book patents declined so sharply?

A: The Orange Book IPR boom of 2015-16 hit an exhaustion point. Many big-blockbuster small-molecule patents have expired or been successfully litigated. Brands now list fewer patents of marginal value, partly due to stricter listing rules. Also, generics may find 180-day exclusivity or settlements more appealing than PTAB given the historical survival rates of Orange Book patents. - Q: How do biologic patent challenges differ from small-molecule cases?

A: Biologic cases often involve different patent types (like manufacturing methods) and utilize different PTAB tools. Notably, the majority of PGR petitions have targeted biologic patents, reflecting complex written-description issues. Biosim challengers tend to file IPR/PGR early (even pre-approval) to shorten delays. Outcomes also differ: biologic patents face higher invalidation rates at PTAB, so the risk/reward profile is distinct. - Q: What strategic advantage does Orange Book data give generics?

A: The Orange Book gives a roadmap of a brand’s core patents and exclusivities. By analyzing it, a generic maker can plan when to file ANDAs and challenge patents. Patent use codes in the Orange Book allow “skinny labels” to avoid certain patented uses. Coupled with PTAB trends (which are publicly available), generics can predict which patents are likely weak or strong. Essentially, Orange Book data helps time market entry and shape labeling strategy. - Q: How should brand companies adapt to these patent trends?

A: Brands should reassess patent strategy: invest in high-value patents (especially those covering manufacturing/unique processes for biologics) and deprioritize weak ones. Given the high PTAB invalidation rate for biologics, originators should be ready with contingency plans (such as developing next-generation formulations or focusing on clinical innovation). For small molecules, continuing to monitor Orange Book listings and delist frivolous patents will keep the landscape clean. In all cases, integration of data analytics into R&D and legal strategy is key. - Q: What role do regulatory changes and policy play in these trends?

A: Big roles. New laws like the Biologic Patent Transparency Act (making patent lists public) and proposals like the Affordable Prescriptions Act (capping biologic patents) are reshaping the playing field. Also, regulatory acceptance of biosimilars in the US is growing (with a record 18 approvals in 2024), which incentivizes more patent challenges. Global rules – such as allowing patent challenges during clinical trials (as in the EU) – may soon influence US policy. Pharma execs should track these changes closely, since they can open or close tactical options for patent defense and challenge.

Sources:

- Finnegan, Henderson, Farabow, Garrett & Dunner, LLP – Trends in PTAB Trials Involving Drug and Biologic Patents (At the PTAB Blog, June 26, 2024).

- DrugPatentWatch – Insights into Shifting Dynamics: Orange Book and Biologic PTAB Trends (Aug 7, 2023).

- Mintz – PTAB Statistics Show Interesting Trends for Orange Book and Biologic Patents in AIA Proceedings (Aug 24, 2021).

- JDSupra (Foley & Lardner) – Trends in Orange Book and Biologic PTAB Trials (June 19, 2023).

- DrugPatentWatch – Revolutionizing the Fight Against Biologic Drug Patent Thickets (May 19, 2025).

- Fish & Richardson (FR) – Biologics and Biosimilars Landscape 2024: IP, Policy, and Market Developments (2024).

- DrugPatentWatch – Drug Patent Research: Expert Tips for Using the FDA Orange and Purple Books (Feb 16, 2023).

- Assoc. for Accessible Medicines – 2023 U.S. Generic & Biosimilar Medicines Savings Report (Generics/Biosimilars Council, 2024).