Introduction: Beyond Bioequivalence – The New Frontier of Generic Drug Safety

Welcome to the paradoxical world of generic pharmaceuticals. On one hand, it’s an undeniable public health triumph. Generic drugs are the workhorses of modern medicine, accounting for a staggering 91% of all prescriptions filled in the United States, yet they represent only about 18.2% of the nation’s total spending on prescription drugs.1 The economic impact is monumental; over the past decade, the use of generic and biosimilar medicines has saved the U.S. healthcare system an estimated $3.1 trillion, with savings reaching $373 billion in 2021 alone.1 They are the bedrock of accessible healthcare, the engine of cost containment, and the reason millions of patients can afford life-saving treatments.

On the other hand, for the companies competing within this arena, it is a brutal, high-stakes gauntlet. The very forces that create immense societal value—intense competition, relentless price pressure, and stringent quality standards—are the same forces that threaten the industry’s long-term sustainability. As one industry expert starkly warned, “The sustainability of our industry remains fragile”. This fragility stems from a dramatic evolution in the market. The golden era of simply replicating blockbuster oral tablets is over. Today’s landscape is defined by complex biologics, labyrinthine global regulatory submissions, and perpetual, high-stakes patent litigation.

For decades, the core challenge for a generic manufacturer was clear: prove bioequivalence. The entire business model rested on demonstrating, through pharmacokinetic studies, that the generic product delivered the same amount of active ingredient to the bloodstream at the same rate as the innovator’s reference listed drug (RLD).6 Master this, and the market was yours to compete for. But the ground has shifted. While bioequivalence remains the non-negotiable entry ticket, the new frontier of competition and risk lies in a far more complex and nuanced domain: pharmacovigilance and proactive risk management.9

Regulators, payers, and patients are no longer satisfied with the simple promise of sameness at the point of approval. They demand continuous, lifecycle-long assurance of safety and effectiveness. This has elevated the role of the Risk Management Plan (RMP) from a bureaucratic, box-checking exercise into a central pillar of corporate strategy. A well-crafted RMP is no longer just a component of a regulatory dossier; it is a testament to a company’s commitment to patient safety, a shield against liability, and, increasingly, a powerful tool for market differentiation.

This report is designed for the strategic leaders in the generic pharmaceutical sector—the heads of regulatory affairs, the portfolio managers, the C-suite executives—who understand this shift. It is a guide not just for how to write a Risk Management Plan, but for why it matters more than ever. We will dissect the two dominant global frameworks: the European Medicines Agency’s (EMA) comprehensive RMP and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) targeted Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS). We will explore the unique challenges and expectations for generic drugs, contrasting them with their innovator counterparts. Most importantly, we will provide actionable strategies for transforming risk management from a costly compliance burden into a source of profound competitive advantage. In a market where price is a race to the bottom, a demonstrable commitment to quality and safety may be the last, best way to stand out.

The commoditization of generics, driven by the intense price pressure inherent in the market, creates a powerful systemic tension with the rising complexity and cost of regulatory compliance. This is particularly true in the realm of risk management. As regulatory expectations for post-market surveillance, impurity testing (like the recent nitrosamine crisis), and detailed risk planning escalate, so do the associated costs. Simultaneously, the entry of multiple competitors for a single product drives prices down dramatically. This squeeze between rising costs and falling prices means that only the most efficient and strategically adept companies can thrive. A company’s ability to develop and maintain a robust, compliant, and cost-effective risk management program is therefore not just a regulatory issue; it is a direct determinant of its long-term financial viability and its ability to contribute to a stable, reliable drug supply chain.

Decoding the Global Risk Management Duopoly: EMA’s RMP vs. FDA’s REMS

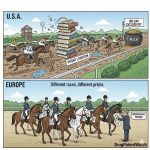

For any generic manufacturer with global ambitions, the world of risk management is dominated by two superpowers with distinctly different ideologies: the European Medicines Agency (EMA) and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). While both agencies share the ultimate goal of protecting public health, their approaches to formal risk management documentation—the RMP in Europe and the REMS in the United States—are built on fundamentally different philosophies. Understanding this divergence is the first step toward developing a coherent and efficient global regulatory strategy. It is not merely a matter of filling out different templates; it requires a dual-track mindset that can adapt to both a proactive, all-encompassing system and a reactive, highly targeted one.

The Foundational Philosophies: Proactive Lifecycle vs. Targeted Intervention

At its core, the difference between the EMA and FDA frameworks is one of scope and intent. The EMA’s approach, codified in its Good Pharmacovigilance Practices (GVP) Module V, views risk management as an integral and continuous part of a drug’s entire lifecycle.12 The

Risk Management Plan (RMP) is therefore a mandatory component for virtually all new marketing authorisation applications (MAAs), including generics.14 It is a living document designed to prospectively identify, characterize, and plan for the mitigation of risks from the moment of submission onward. The philosophy is holistic and universal: every drug has a risk profile that must be actively managed and documented throughout its time on the market.

The FDA, on the other hand, employs a more focused and interventional model. The agency’s primary risk management tool is the FDA-approved product labeling, which it considers sufficient for the vast majority of drugs.17 A formal

Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) is required only for a small subset of medications—those with serious safety concerns where the agency determines that labeling alone is not enough to ensure the drug’s benefits outweigh its risks.15 The REMS is not a comprehensive safety profile but a specific, action-oriented safety program designed to reinforce behaviors that support the safe use of that particular medication.19 It is a scalpel, not a blanket.

This philosophical divergence creates immediate and significant strategic complexity for global generic manufacturers. A company cannot simply develop a single, harmonized “global risk management package.” It must operate with a bifurcated strategy. For the European Union, the approach must be comprehensive, data-intensive, and rooted in scientific documentation and forward-looking pharmacovigilance planning. It is a predictable, albeit complex, part of every submission. For the United States, the strategy is different. For most generics, no formal REMS is required. However, if the reference brand drug does have a REMS, the generic company is thrust into a high-stakes process that is often less about scientific documentation and more about legal negotiation, operational logistics, and overcoming potential anti-competitive hurdles erected by the brand manufacturer.18 This bifurcation has profound implications for how a company allocates its resources, plans its submission timelines, and assesses the overall risk of its product portfolio.

Anatomy of an EMA Risk Management Plan (RMP)

The structure of the EU RMP is modular and comprehensive, designed to provide a complete picture of the risk management system for a given product. It is detailed in the EMA’s Guideline on Good Pharmacovigilance Practices (GVP) Module V and the associated RMP template.12 Think of it as a strategic blueprint for a drug’s safety lifecycle.

Part I: Product Overview & Part II: The Safety Specification

The RMP begins with a product overview, but its heart is the Safety Specification. This is the foundational section that summarizes what is known—and not known—about a drug’s safety profile. It is here that the Marketing Authorisation Holder (MAH) must systematically categorize all relevant safety concerns into three distinct buckets 15:

- Important Identified Risks: These are adverse events for which there is adequate scientific evidence of an association with the drug. They are risks that could impact the benefit-risk balance of the product or have public health implications.

- Important Potential Risks: These are untoward occurrences where there is some basis for suspicion of an association with the drug, but the link has not been confirmed. These risks are significant enough that they warrant further investigation.

- Missing Information: This category captures gaps in knowledge about the drug’s safety in certain situations or patient populations that could be clinically significant. Common examples include use in pregnant or lactating women, patients with severe renal or hepatic impairment, or pediatric populations, if they were not adequately studied pre-approval.

This structured classification forces a disciplined and transparent approach to risk assessment, forming the basis for all subsequent planning.

Part III: The Pharmacovigilance (PV) Plan

Once the risks and knowledge gaps are specified, the Pharmacovigilance Plan outlines how the company will monitor these issues and continue to build the safety profile of the drug post-authorization.24 This plan is divided into two types of activities:

- Routine Pharmacovigilance: These are the standard, legally required activities for all medicines. They include the collection and assessment of spontaneous adverse event reports, signal detection and management, and the submission of Periodic Safety Update Reports (PSURs).24

- Additional Pharmacovigilance Activities: When routine monitoring is not sufficient to address a specific safety concern, regulators may require additional activities. These are often formal, structured studies known as Post-Authorisation Safety Studies (PASS), which can range from observational cohort studies using real-world data to patient registries designed to collect specific information over time.9

Part V: The Risk Minimisation Plan

The final core component is the Risk Minimisation Plan, which describes the interventions intended to prevent or reduce the occurrence and/or severity of adverse reactions.16 Like the PV plan, it consists of two levels:

- Routine Risk Minimisation Measures: These are the standard tools applicable to all medicines. The primary instruments are the legally mandated product information documents: the Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC) for healthcare professionals and the Patient Information Leaflet (PIL) for patients. Other routine measures include labeling, pack size, and the legal (prescription) status of the drug.15

- Additional Risk Minimisation Measures (aRMMs): For certain significant risks, routine measures may be deemed insufficient. In these cases, regulators can mandate aRMMs. These are targeted interventions designed to ensure the safe and effective use of the product. Examples are extensive and can include educational programs for doctors and patients, controlled access programs that restrict dispensing to certified pharmacies, or pregnancy prevention programs for teratogenic drugs.15

Anatomy of an FDA Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS)

The FDA’s REMS framework, authorized by the Food and Drug Administration Amendments Act (FDAAA) of 2007, is fundamentally different in structure and purpose. It is not a comprehensive safety dossier but a specific, enforceable safety program with clearly defined goals and elements designed to mitigate a particular serious risk associated with a drug.19

Core Components: Medication Guides and Communication Plans

Many REMS programs are built upon one or both of these foundational elements:

- Medication Guide: A patient-friendly leaflet, written in non-technical language, that is dispensed with the prescription. It provides crucial information about the drug’s serious risks and what patients need to know for its safe use.

- Communication Plan: A plan developed by the manufacturer to disseminate key safety information to healthcare providers. This can involve sending “Dear Healthcare Provider” letters, distributing materials through professional societies, or providing information through other channels to ensure prescribers are aware of the specific risks and the REMS requirements.15

The High Stakes of ETASU: Elements to Assure Safe Use

The most stringent and operationally complex components of a REMS are known as Elements to Assure Safe Use (ETASU). These are required when the risks are so severe that broader communications are not enough. ETASU impose specific restrictions on the prescribing, dispensing, or use of a drug. These can include one or more of the following 18:

- Healthcare Provider Certification: Prescribers may be required to have special training or experience and must formally enroll in the REMS program to be certified to prescribe the drug.

- Pharmacy Certification: Pharmacies, hospitals, or other healthcare settings may need to be specially certified to dispense the drug, ensuring they have the necessary systems in place to comply with the REMS.

- Dispensing Restrictions: The drug may only be dispensed to patients with evidence of safe-use conditions, such as a negative pregnancy test or required laboratory monitoring results.

- Patient Monitoring: Patients may be required to undergo specific monitoring and be enrolled in a registry to track their progress and any adverse events.

- Restricted Distribution: In the most extreme cases, the manufacturer implements a tightly controlled distribution system that limits which wholesalers and pharmacies can handle the drug.

A clear example of an ETASU in action is the REMS for Zyprexa Relprevv (olanzapine), an extended-release injectable antipsychotic. The drug carries a small but serious risk of post-injection delirium sedation syndrome. To mitigate this, the REMS requires that the drug only be administered in certified healthcare facilities that can observe the patient for at least three hours post-injection and are equipped to provide immediate medical care if an adverse event occurs. This ETASU fundamentally changes how and where the drug can be used, creating a significant operational infrastructure around it.

At a Glance: FDA REMS vs. EMA RMP for Generic Applicants

To crystallize these differences, the following table provides a direct comparison of the two systems from the specific perspective of a generic drug manufacturer, highlighting the key strategic considerations.

| Feature | EMA Risk Management Plan (RMP) | FDA Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) |

| Applicability | Required for all new Marketing Authorisation Applications (MAAs), including generics.14 | Required only for specific drugs with serious safety concerns where labeling alone is insufficient.15 |

| Core Philosophy | Proactive, lifecycle-based documentation of a drug’s entire safety profile.9 | Targeted, interventional safety program focused on mitigating specific, identified serious risks.17 |

| Key Components | 1. Safety Specification (Identified Risks, Potential Risks, Missing Info)2. Pharmacovigilance Plan (Routine & Additional)3. Risk Minimisation Plan (Routine & Additional).15 | 1. Medication Guide2. Communication Plan3. Elements to Assure Safe Use (ETASU).15 |

| Requirement for Generics | Must submit an RMP that is aligned with the safety concerns of the reference (innovator) product’s RMP. | If the brand drug has a REMS, the generic must also have a REMS with the same goals and comparable elements, often through a single, shared system.20 |

| Primary Challenge for Generics | Ensuring accurate and complete alignment with the innovator’s safety profile and scientifically justifying any generic-specific deviations.12 | Overcoming brand-led delays in (1) accessing drug samples for bioequivalence testing and (2) negotiating the required single, shared REMS system.18 |

| Lifecycle Management | A “living document” that must be updated throughout the product’s life as new safety information emerges or milestones are reached.14 | Can be modified or “sunsetted” (removed) by the FDA if assessment data shows the additional measures are no longer necessary to ensure benefits outweigh risks.20 |

The Innovator’s Shadow: Mastering RMP/REMS Requirements for Generic Drugs

For a generic drug manufacturer, the path to regulatory approval is not forged in isolation. It is, by definition, a journey taken in the shadow of the innovator product. The foundational principle of the abbreviated pathway is reliance on the safety and efficacy data already established by the brand-name drug. This principle extends directly and powerfully into the realm of risk management. A generic company’s primary responsibility is not to create a safety profile from scratch, but to demonstrate that its product faithfully mirrors the known safety profile of the reference drug. Mastering this alignment is the cornerstone of a successful generic RMP or REMS strategy.

The Golden Rule: Alignment with the Reference Product

The single most important rule for a generic drug’s Risk Management Plan is alignment. Regulatory agencies, particularly the EMA, mandate that the safety concerns outlined in a generic’s RMP must be consistent with those of the originator’s product.25 This means the lists of Important Identified Risks, Important Potential Risks, and Missing Information should be, for all intents and purposes, identical.

This is not a matter of guesswork. Generic applicants are expected to conduct thorough due diligence to identify the reference product’s established safety profile. The primary sources for this critical information include 12:

- The Innovator’s Approved RMP: The EMA publishes RMPs for all centrally authorised products, providing a direct source for the safety specifications.

- Public Assessment Reports: European Public Assessment Reports (EPARs) and Australian Public Assessment Reports (AusPARs) often contain summaries of the key safety concerns.

- CMDh Website: For products approved through mutual recognition or decentralized procedures, the Coordination Group for Mutual Recognition and Decentralised Procedures – Human (CMDh) may publish a list of safety concerns for a given active substance.

In the United States, the principle of alignment is just as critical, particularly for drugs with a REMS. The law requires that any generic version of a drug with a REMS must also have a REMS with the same goals and comparable requirements.20 This often culminates in the need for a “single, shared system REMS,” where both the brand and generic manufacturers collaborate on one unified program to avoid burdening the healthcare system with multiple, slightly different sets of rules for the same molecule.21

When to Deviate: Justifying Generic-Specific Safety Concerns

While alignment is the golden rule, it is not an absolute one. Regulators recognize that a generic product, despite being bioequivalent, is not identical to the brand in every conceivable way. There are allowable differences in manufacturing processes, excipients, and sometimes even delivery devices. It is in these differences that new, generic-specific risks can arise. Therefore, a generic manufacturer has a responsibility to not only align with the innovator’s profile but also to rigorously assess its own product for any unique safety concerns and, if found, to justify their inclusion in the RMP.12

This places the burden of proof squarely on the generic applicant. It is not enough to simply copy the innovator’s safety list. The company must perform its own internal risk assessment to actively confirm that no new risks have been introduced by its specific formulation or manufacturing process. If new risks are identified, they must be characterized, added to the safety specification, and addressed with appropriate pharmacovigilance and risk minimization plans. This transforms the task from one of passive imitation to one of active scientific validation.

Common sources of generic-specific risks that may warrant deviation from the innovator’s RMP include:

- Different Excipients: The use of a different inactive ingredient could introduce a risk not present in the brand, such as a known allergen or an excipient with a physiological effect in certain patient populations.32

- Manufacturing Impurities: A different chemical synthesis route for the Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) can result in different impurity profiles. These new impurities must be assessed for potential toxicity and, if significant, may need to be listed as a potential risk.32

- Device or Formulation Differences: A generic injectable product might use a different autoinjector device than the brand. If this difference could lead to user confusion or dosing errors, “medication error” may need to be added as a potential risk. Similarly, a new, higher concentration of an injectable solution could increase the risk of overdose if not handled correctly.

- Different Patient Populations or Indications: In some cases, a generic may be approved for a narrower set of indications than the brand. This could create a risk of foreseeable off-label use in populations where safety has not been established, which may need to be addressed in the RMP.

The “Abbreviated” RMP: Leveraging the Generic Pathway in the EU

The EMA recognizes that for many straightforward generic products, requiring a full, multi-hundred-page RMP that largely duplicates the innovator’s document is an unnecessary burden. The regulatory framework therefore allows for a risk-proportionate approach.

For a standard generic application (under Article 10(1)) where the reference medicinal product has a well-established safety profile, a published RMP, and no additional risk minimization measures (aRMMs), the generic applicant can often submit a streamlined RMP.12 Specifically, several modules of the Safety Specification (Part II), which are based on the innovator’s extensive clinical trial data, may be omitted or significantly reduced. These typically include :

- Module SI: Epidemiology of the Indication

- Module SII: Non-clinical Safety Specification

- Module SIII: Clinical Trial Exposure

- Module SIV: Populations Not Studied in Clinical Trials

In these cases, the generic RMP focuses primarily on confirming alignment of the safety concerns with the reference product and detailing the routine pharmacovigilance and risk minimization plans that will be in place. However, this abbreviated option vanishes the moment additional measures are involved. If the originator product has aRMMs in place—such as an educational program or a controlled access system—the generic applicant is required to submit a full RMP, including a detailed Part V describing how it will implement comparable risk minimization activities.16

Navigating the REMS Minefield: A Strategic Guide for Generic Challengers

If the European RMP system is a complex but largely navigable waterway, the American REMS system, for certain high-risk drugs, can be a minefield. While the FDA’s intent with REMS is solely to ensure patient safety, the structure of the regulations, particularly those involving Elements to Assure Safe Use (ETASU), has created loopholes that some brand-name manufacturers have been accused of exploiting to delay and obstruct generic competition. A 2014 study sponsored by the Generic Pharmaceutical Association (now the Association for Affordable Medicines) estimated that this misuse costs the U.S. healthcare system billions annually.

For a generic company, understanding and preparing for these strategic roadblocks is not just good practice; it is essential for survival. The decision to pursue a generic version of a drug with a REMS with ETASU must be viewed as a high-risk financial investment, requiring a strategy that integrates regulatory, legal, and business development functions from day one.

The Two-Front War: Sample Access and Shared Systems

The anti-competitive misuse of REMS typically unfolds on two main fronts, creating a formidable barrier to entry for generic challengers.18

The Sample Blockade

To gain approval, a generic manufacturer must conduct bioequivalence (BE) studies, which requires obtaining a sufficient quantity of the brand-name reference drug for testing. For most drugs, this is a simple matter of purchasing the product through normal wholesale channels. However, for drugs with a REMS that includes a restricted distribution ETASU, this straightforward path is blocked.

The restricted distribution system is designed to ensure the drug is only supplied to certified and authorized entities (doctors, pharmacies) to prevent misuse. A generic company seeking samples for BE testing is not such an entity. Brand manufacturers have seized on this, refusing to sell samples directly to generic competitors, often citing safety concerns and potential liability if an adverse event were to occur during the BE study. This tactic, known as the “sample blockade,” can effectively halt a generic development program in its tracks. The FDA, while sympathetic to the generic industry’s plight, historically lacked the explicit authority to compel a brand company to sell its product, even after issuing a letter confirming that providing samples for BE testing would not violate the REMS. Generic manufacturers have reported delays of years just to negotiate a supply agreement, if one is reached at all.

The Negotiation Quagmire

The second front in this war is the legal requirement for a single, shared system REMS. To avoid confusion and undue burden on the healthcare system, the law mandates that when a generic enters the market for a REMS drug, both the brand and generic companies should operate under a single, unified program for any ETASU components.21

While logical in principle, this requirement has become another tool for delay. Brand companies can engage in indefinitely prolonged negotiations over the terms of this shared system. They can raise a host of complex issues—from the design of the IT portal and adverse event reporting protocols to cost-sharing formulas, decision-making authority, and intellectual property rights—to justify the protracted timeline. Each day of delay is another day of monopoly profits for the brand and another day that patients are denied access to a more affordable alternative.

The systemic nature of this problem is underscored by the fact that it is not a rare occurrence. As of 2009, only a quarter of REMS programs included the more complex ETASU. By the late 2010s, that figure had jumped to over 50%, making these competitive hurdles a far more common feature of the generic landscape. This reality has transformed the REMS regulation from a pure safety measure into a form of para-intellectual property, capable of extending a drug’s market exclusivity well beyond the life of its patents. A generic portfolio manager must now assess a REMS with ETASU as a risk factor as significant as a complex patent estate, budgeting for litigation and building timelines that assume a period of determined non-cooperation from the brand.

Counter-Maneuvers and Regulatory Levers

Faced with these significant challenges, the generic industry and lawmakers have developed counter-strategies and new regulatory tools to level the playing field. A generic company facing a REMS blockade is no longer without recourse.

The most significant development was the passage of the Creating and Restoring Equal Access to Equivalent Samples (CREATES) Act in 2019. This legislation provides a specific legal pathway for generic and biosimilar developers who have been denied access to samples. A developer can now bring a civil action in federal court to obtain the necessary samples. The law also includes provisions to facilitate the development of a single, shared REMS system, allowing the FDA to step in when negotiations stall.

Beyond the CREATES Act, the FDA itself has provided guidance to streamline the process. The agency has published draft guidances on the “Development of a Shared System REMS” and “Waivers of the Single, Shared System REMS Requirement”. While the FDA considers a waiver—allowing the generic to develop its own separate but comparable REMS—to be an “option of last resort,” the guidance clarifies the circumstances under which it will be granted. A waiver may be issued if the burden of creating a shared system outweighs the benefits, or if a key aspect of the brand’s REMS is protected by a patent or trade secret and the brand refuses to grant a license.18

For generic companies, the strategic playbook is now clearer:

- Document Everything: Meticulously document all attempts to purchase samples and negotiate a shared system. This paper trail is crucial for any future legal action under the CREATES Act or a waiver request to the FDA.

- Engage the FDA Early: Proactively communicate with the FDA about the development plan and any anticipated difficulties in obtaining samples or negotiating the shared REMS.

- Leverage the CREATES Act: Be prepared to initiate legal action swiftly if the brand company refuses to sell samples in a timely manner and on commercially reasonable terms.

- Evaluate the Waiver Pathway: In cases of intractable negotiations, assess the feasibility of petitioning the FDA for a waiver of the single, shared system requirement, presenting a strong case that the brand’s obstructionism makes a shared system an unreasonable burden.

Building a Bulletproof Generic RMP: A Step-by-Step Implementation Guide

Developing a robust and compliant Risk Management Plan is a systematic process that transforms raw data and regulatory requirements into a coherent strategic document. It is not a task for a single individual or department but a cross-functional endeavor that requires collaboration from the earliest stages of product development. This guide breaks down the process into three logical phases: foundational assessment, core drafting, and lifecycle management.

Phase 1: Foundational Risk Assessment and Intelligence Gathering

Before a single word of the RMP is written, a solid foundation of information and analysis must be laid. This preparatory phase is critical for ensuring the final document is comprehensive, accurate, and strategically sound.26

Assembling the Cross-Functional Team

The first step is to convene the right team. An effective RMP cannot be developed in a regulatory silo. It requires a multidisciplinary group of experts who can provide input from various perspectives. The core team should include representatives from:

- Regulatory Affairs: To lead the process, ensure compliance with global guidelines, and manage the submission.

- Pharmacovigilance: To provide expertise on safety data collection, signal detection, and post-market surveillance requirements.

- Clinical/Medical Affairs: To interpret the clinical significance of identified risks and contribute to the safety specification.

- Chemistry, Manufacturing, and Controls (CMC): To identify potential risks arising from the specific manufacturing process, API synthesis route, excipients, and packaging.

- Legal and Intellectual Property: Particularly crucial for REMS products in the U.S., to navigate shared system negotiations and potential litigation.

Scoping the Reference Product’s Safety Profile

The cornerstone of the generic RMP is a deep understanding of the innovator product’s safety profile. The team must conduct a comprehensive intelligence-gathering exercise to collate all available information on the reference drug’s known and potential risks. This involves a systematic review of 12:

- Regulatory Documents: Sourcing the latest approved RMP for the reference product from the EMA’s website or other regulatory agency portals.

- Public Assessment Reports: Analyzing EPARs, AusPARs, and FDA review documents for summaries of safety concerns identified during the original approval process.

- Published Lists: Checking for official lists of safety concerns for the active substance on platforms like the CMDh website.

- Scientific Literature: Conducting a thorough literature search for any new safety signals or studies published since the last update of the innovator’s RMP.

Internal Risk Assessment of the Generic Product

Simultaneously, the team must turn its focus inward and conduct a rigorous risk assessment of its own product. This is the critical step to identify any potential risks that are unique to the generic version. This process should leverage established risk management tools, such as Failure Mode and Effects Analysis (FMEA) or Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points (HACCP), to systematically evaluate every stage of the product’s lifecycle.37 Key areas of focus include 32:

- API Sourcing and Synthesis: Are there any new or different impurities generated by the chosen synthesis route? What are the controls and specifications for these impurities?

- Excipients: Have any excipients been used that are different from the brand? What is their known safety profile? Is there a potential for interaction with the API?

- Manufacturing Process: Are there any steps in the manufacturing process (e.g., granulation, compression, sterilization) that could introduce risks such as microbial contamination, cross-contamination, or degradation of the product?

- Container Closure System and Device: Is the packaging or delivery device different from the brand? Could these differences lead to stability issues, leachables, or medication errors?

Phase 2: Drafting the Core RMP Document

With a comprehensive foundation of data and analysis, the team can begin drafting the RMP document itself, adhering closely to the official regulatory templates, such as the one provided by the EMA for the EU.

Crafting the Safety Specification (Part II)

This is where the intelligence gathered in Phase 1 is synthesized into the formal Safety Specification. The key is to achieve a balance between alignment and transparency.

- Alignment: The list of Important Identified Risks, Potential Risks, and Missing Information must, as a starting point, mirror that of the reference product. This demonstrates to regulators that the applicant has done their due diligence.

- Justification: Any deviations—risks added, reclassified, or removed based on the internal risk assessment—must be clearly flagged and robustly justified with scientific rationale and supporting data. For example: “Important Potential Risk X (allergic reaction to excipient Y) has been added to the safety specification. While not listed in the RMP for the reference product, our formulation utilizes excipient Y, which is not present in the reference product. Published literature indicates a known, though rare, risk of hypersensitivity to this excipient.”

Designing the Pharmacovigilance Plan (Part III)

For most generics, the PV plan will consist of routine activities. The RMP should clearly state that the company has a compliant pharmacovigilance system in place for collecting and reporting adverse events, performing signal detection, and submitting PSURs as required.24

If the internal risk assessment identified a specific potential risk (e.g., medication error due to a new device), the PV plan may need to include additional activities. This could involve targeted follow-up questionnaires for any reported medication errors or, in more significant cases, a proposal for a patient registry to proactively monitor the use of the new device in a real-world setting.

Defining the Risk Minimisation Measures (Part V)

For the vast majority of generic drugs, this section will be straightforward. It will state that routine risk minimization measures (SmPC, PIL, labeling) are considered sufficient to manage the product’s risks.

However, if the innovator product is subject to aRMMs, this section becomes critical. The generic manufacturer must describe its plan to implement comparable measures. This involves :

- Obtaining Innovator Materials: Sourcing the innovator’s educational materials, prescriber checklists, or patient alert cards.

- Adapting for the Generic: Re-creating these materials for the generic product, ensuring the core safety messages remain identical. The materials should be branded for the generic company but consistent in content and purpose with the innovator’s.

- Describing the Distribution Plan: Outlining how these materials will be disseminated to healthcare professionals and patients.

Phase 3: Submission, Review, and Lifecycle Management

The final phase involves the practicalities of submitting the RMP and, crucially, maintaining it over time.

- Submission: The RMP is submitted as part of the electronic Common Technical Document (eCTD) dossier, typically in Module 1.8.2. It’s best practice to also include a “track changes” version in Microsoft Word format to help regulators easily identify updates from previous versions.

- Review Process: During the agency’s review, assessors may send questions or request clarifications and modifications to the RMP. The company must respond to these in a timely and scientific manner.

- Lifecycle Management: This is perhaps the most important, and often overlooked, aspect. The RMP is not a static document that is filed and forgotten. It is a living document that must be actively maintained and updated throughout the product’s entire time on the market.9 An updated RMP must be submitted whenever:

- A significant new safety risk is identified.

- The risk-benefit balance of the product changes.

- A major milestone in the pharmacovigilance plan is reached (e.g., the completion of a PASS).

- The regulatory agency requests an update.

Failure to maintain the RMP is a serious compliance failure. Companies must have robust internal processes for monitoring new safety information and triggering an RMP update when necessary.

The Power of Post-Market Intelligence: Leveraging Data for Continuous Safety

The abbreviated nature of the generic drug approval process means that manufacturers are exempt from conducting the large, expensive pre-market clinical trials required of innovators. However, this exemption does not extend to post-market responsibilities. Once a generic drug is on the market, its manufacturer bears the full weight of pharmacovigilance obligations, identical to those of any brand-name company.39 This mandate for continuous safety monitoring is not just a regulatory requirement; in an increasingly data-rich world, it presents a strategic opportunity for forward-thinking generic companies to build a competitive advantage based on safety and quality.

The Pharmacovigilance Mandate for Generic Manufacturers

Every generic Marketing Authorisation Holder (MAH) is legally required to operate a robust pharmacovigilance system. This system must be capable of 10:

- Collecting Adverse Events: Systematically gathering reports of suspected adverse drug reactions (ADRs) from all sources, including patients, healthcare professionals, and scientific literature.

- Evaluating and Reporting: Assessing the validity, seriousness, and expectedness of these reports and submitting Individual Case Safety Reports (ICSRs) to regulatory authorities within strict timelines.

- Signal Detection: Continuously monitoring the accumulated safety data to identify any new or changing safety issues (signals) that may suggest a causal relationship with the drug.

- Benefit-Risk Assessment: Periodically evaluating the drug’s overall benefit-risk profile in light of all new safety information, a process formalized in the Periodic Benefit-Risk Evaluation Report (PBRER) or PSUR.

This is a significant operational undertaking. However, for generic manufacturers, it is compounded by a unique challenge: misattribution. When multiple generic versions of the same active ingredient are on the market, an adverse event report may simply name the active substance (e.g., “atorvastatin”) without specifying the manufacturer. This makes it incredibly difficult to trace an ADR back to a specific product, complicating the signal detection process for any individual company.

The Rise of Real-World Evidence (RWE) in Generic Safety Surveillance

To overcome the limitations of traditional, passive pharmacovigilance and the challenge of misattribution, leading companies are turning to a powerful new tool: Real-World Evidence (RWE). RWE is clinical evidence regarding the usage and potential benefits or risks of a medical product derived from the analysis of Real-World Data (RWD).43 RWD is health information collected outside the context of conventional clinical trials, from sources such as 43:

- Electronic Health Records (EHRs)

- Medical claims and billing data

- Product and disease registries

- Data from wearable devices and mobile health apps

Regulatory agencies like the FDA and EMA are increasingly embracing the use of RWE to support regulatory decision-making across the entire product lifecycle, from initial approval to post-market monitoring.43 For generic companies, which by their nature lack proprietary clinical trial data, RWE offers a transformative opportunity.

By investing in the capability to analyze large RWD sources, a generic manufacturer can proactively monitor the safety of its products in a way that goes far beyond traditional spontaneous reporting. RWE can be leveraged to 45:

- Conduct Active Safety Surveillance: Instead of waiting for reports to come in, companies can actively query large healthcare databases to monitor for safety signals in vast, diverse patient populations that were never included in the innovator’s original trials.

- Perform Comparative Safety Studies: RWE can be used to compare the safety profiles of a company’s generic product against the brand-name drug or against other generic versions, providing concrete data to support its quality and safety.

- Fulfill Post-Authorisation Study Requirements: If a regulator imposes a PASS as a condition of approval, RWE studies are often the most efficient and effective way to meet that requirement.

This represents a fundamental strategic shift. For decades, generic companies have been “followers” in the realm of safety information, relying entirely on the data generated by the innovator. By building RWE capabilities, a generic company can become a “leader” in product stewardship. It can generate its own unique, proprietary data on its product’s performance in the real world. This data serves a dual purpose. Defensively, it provides a powerful tool to investigate and refute any spurious claims about quality or safety issues. Offensively, it allows the company to differentiate itself in a crowded, commoditized market. A generic firm that can go to payers and large healthcare systems with robust RWE demonstrating the safety and effectiveness of its product is providing value that extends far beyond a low price. It is positioning itself as a data-driven partner in the healthcare ecosystem, building a brand based on trust and quality in a market where those attributes are paramount.

From Data to Dominance: Integrating Patent Intelligence into Your Risk Strategy

In the hyper-competitive generic drug market, the most successful companies are those that master the art of proactive risk management. This doesn’t begin when the RMP is being drafted; it begins at the very first stage of the development pipeline: portfolio selection. The decision of which products to pursue is the single most critical risk management decision a generic company makes. A strategic misstep here can lead to millions in wasted R&D expenditure and years of fruitless regulatory battles. Integrating sophisticated patent and regulatory intelligence into this early-stage assessment is therefore not a luxury, but a necessity for survival and success.

Using Competitive Intelligence to De-Risk Portfolio Selection

The modern generic development landscape is littered with regulatory and legal traps that can delay or derail a product launch. Many of these traps are predictable if you know where to look. This is where competitive intelligence platforms like DrugPatentWatch become indispensable strategic tools.49 By providing a comprehensive, integrated view of the patent, litigation, and regulatory landscape for any given drug, these platforms allow a company to identify and quantify risks

before committing significant resources.

Screening for REMS-Related Risks

As discussed, a REMS with ETASU is one of the most significant barriers to generic entry in the U.S. market. A portfolio selection process that fails to account for this risk is fundamentally flawed. Using a platform like DrugPatentWatch, a business development team can quickly identify which branded drugs on their target list have a REMS. But the analysis shouldn’t stop there. By cross-referencing this information with the platform’s extensive litigation database, the team can dig deeper. Has the brand manufacturer been sued by other generic companies for refusing to sell samples? Do they have a history of engaging in protracted negotiations over shared REMS systems? Are there patents specifically covering the REMS process itself, which could be used to block a generic version? The answers to these questions allow the company to assign a “REMS risk score” to the product candidate. A high-risk score doesn’t necessarily mean the product is a “no-go,” but it does mean the business case must be adjusted to account for a higher budget for legal fees and a longer, more uncertain timeline to market entry.

Anticipating Formulation and Excipient Challenges

Beyond REMS, patent intelligence can reveal critical scientific and technical risks. The formulation of a drug product is often just as heavily patented as the active molecule itself. A thorough analysis of a brand’s patent estate on DrugPatentWatch can reveal patents covering specific excipient combinations, manufacturing processes, or complex delivery systems (e.g., extended-release technologies, transdermal patches).49

This information is a crucial early warning signal. A dense “patent thicket” around a product’s formulation suggests two things. First, the legal path to a non-infringing generic will be complex and costly. Second, and perhaps more importantly, it signals that the product is likely scientifically challenging to replicate. Innovator companies don’t spend millions patenting trivial formulation details. They patent the specific, hard-won solutions to problems of stability, solubility, or bioavailability. The presence of these patents is a strong indicator that developing a bioequivalent generic will be a high-risk R&D endeavor with a greater chance of failure.

By integrating this patent and regulatory intelligence directly into the portfolio assessment process, a generic company can fundamentally change its approach to risk. Instead of reacting to legal and regulatory problems after R&D is already underway, it can anticipate them. This allows the company to quantify and price-in these risks when building its financial models. The result is a more accurate and realistic Return on Investment (ROI) calculation for each product candidate. This data-driven approach prevents the company from squandering precious R&D resources on products that are destined to become mired in predictable, brand-manufactured delays or insurmountable technical hurdles. It shifts the role of the regulatory and legal teams from a downstream compliance function to an upstream strategic advisor, ensuring that capital is allocated to the products with the highest probability of both regulatory and commercial success.

Conclusion: The Future of Generic Risk Management is Proactive, Data-Driven, and Global

The landscape for generic pharmaceuticals has irrevocably changed. The straightforward path of replicating simple molecules and competing solely on price is narrowing, giving way to a far more complex and challenging environment. Success in this new era demands a paradigm shift in how companies approach risk. No longer a siloed compliance function, risk management must become the strategic core of the entire generic enterprise, influencing decisions from the earliest stages of portfolio selection to the final phases of post-market surveillance.

The journey we have charted through the intricacies of EMA’s RMPs and the FDA’s REMS reveals a clear truth: navigating the global regulatory environment requires a sophisticated, dual-track strategy. It demands a deep understanding of the proactive, lifecycle-based philosophy of the EU and the targeted, interventional approach of the US. For generic manufacturers, this is not an academic distinction; it has profound, real-world implications for resource allocation, submission timelines, and the very viability of a global launch.

The central principle of alignment with the innovator’s safety profile—the “innovator’s shadow”—remains the golden rule. Yet, we have seen that this is not a passive act of imitation. It is an active, scientific process of validation, requiring a generic company to rigorously assess its own product and be prepared to robustly justify any and all deviations. This responsibility for product stewardship is absolute.

Furthermore, the weaponization of safety regulations like REMS as anti-competitive tools has transformed parts of the regulatory process into a strategic battleground. Generic companies must enter this arena prepared, armed with a deep understanding of the legal and regulatory counter-maneuvers available to them, and with business models that account for the high costs and extended timelines of such conflicts.

Looking ahead, several trends will continue to shape this landscape. The push for global harmonization, driven by bodies like the ICH, will hopefully streamline some requirements, but regional differences will persist for the foreseeable future.9 New areas of risk, such as the environmental impact of pharmaceuticals, are moving from the periphery to the center of regulatory focus, adding new layers of complexity and cost, particularly for generics that were previously exempt. Above all, the relentless pressure on global supply chain integrity, quality, and transparency will only intensify.

The ultimate conclusion is a call to action. The generic companies that will thrive in the coming decade are those that move beyond a reactive, compliance-first mindset. The winners will be those who embrace a proactive, data-driven, and globally-minded approach to risk management. They will leverage competitive intelligence to make smarter portfolio decisions, build RWE capabilities to differentiate their products on quality and safety, and integrate risk assessment into every facet of their operations. By doing so, they will not only ensure compliance and protect patients; they will build more resilient, more profitable, and more sustainable businesses capable of succeeding in the demanding generic gambit.

Key Takeaways

- Risk Management as a Strategic Imperative: In the highly competitive and price-pressured generic drug market, mastering risk management has evolved from a simple compliance task into a critical source of competitive advantage and a determinant of long-term business sustainability.

- Divergent Global Frameworks Require a Dual Strategy: The EMA’s proactive, lifecycle-based RMP system and the FDA’s targeted, interventional REMS system are philosophically different. Generic companies must develop a dual-track global strategy to navigate both, allocating resources for comprehensive scientific documentation in the EU and for potential high-stakes legal and operational challenges in the US.

- Alignment is Active, Not Passive: The core requirement for a generic RMP/REMS is alignment with the innovator’s safety profile. However, this is not a “copy-paste” exercise. It requires a rigorous internal risk assessment of the generic product’s specific formulation, impurities, and manufacturing process to actively confirm sameness and scientifically justify any necessary deviations.

- Anticipate and Counter Anti-Competitive REMS Tactics: Brand manufacturers can use REMS with ETASU to block generic entry by denying access to samples and prolonging shared-system negotiations. Generic firms must build strategies that anticipate these delays, budget for potential litigation under the CREATES Act, and understand the FDA’s waiver process.

- Integrate Intelligence into Portfolio Selection: The most effective risk management begins before R&D. By using competitive intelligence platforms like DrugPatentWatch, companies can screen for REMS-related risks and complex formulation patents at the portfolio selection stage, creating more accurate ROI models and avoiding high-risk projects.

- Leverage Real-World Evidence (RWE) for Differentiation: Generic companies lack proprietary clinical trial data. Investing in RWE capabilities allows them to proactively monitor their products’ safety in the real world, defend their quality, and differentiate themselves to payers and providers on a basis other than price, transforming them from followers to leaders in product stewardship.

- The RMP is a Living Document: A Risk Management Plan is not a one-time submission. It must be continuously updated throughout the product’s lifecycle in response to new safety information, regulatory requests, or pharmacovigilance milestones. Failure to do so is a significant compliance risk.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. Is an RMP always required for a generic drug in the EU?

Not always, but it is the default expectation for all new Marketing Authorisation Applications. For simple, low-risk generic products where the innovator’s reference drug has a well-established safety profile and no additional risk minimization measures (aRMMs), a streamlined or “abbreviated” RMP may be acceptable. This often involves omitting sections based on the innovator’s clinical trial data. However, if the innovator product has any aRMMs (e.g., an educational program, a patient alert card), the generic applicant must submit a full RMP and detail how it will implement comparable measures.12

2. What is the most significant difference in risk management for a generic versus an innovator drug?

The most significant difference is the starting point. An innovator company develops its RMP based on its own extensive pre-clinical and clinical trial data, identifying risks and uncertainties from scratch. A generic company’s primary responsibility is to align its RMP with the already established safety profile of the innovator’s reference product. The generic’s main task is to demonstrate that its product introduces no new risks due to differences in formulation or manufacturing, whereas the innovator’s task is to characterize the risks of the molecule for the first time.

3. Can a brand company patent its REMS program to block generics?

Yes, this is a recognized strategy. Brand companies have been observed obtaining patents not just on the drug itself, but on specific methods or systems required to execute a REMS with ETASU. This can create an additional intellectual property barrier for a generic company trying to create a comparable or shared REMS system. This is one of the situations where the FDA may consider granting a waiver of the single, shared system requirement, if the brand refuses to license the patented aspect on reasonable terms. This tactic highlights the need for generic companies to conduct thorough patent analyses that go beyond the active ingredient.

4. How can a smaller generic company with limited resources effectively manage post-market surveillance?

Effective post-market surveillance is scalable. While smaller companies may not have the resources for large-scale RWE studies, they must have a fully compliant core pharmacovigilance system for collecting, assessing, and reporting adverse events. Key strategies for resource-limited firms include:

- Partnering with a PV Service Provider: Outsourcing ICSR processing and literature screening to a specialized vendor can be more cost-effective than building an in-house team.

- Focusing on Signal Detection: Using validated statistical methods to analyze their own safety database for potential signals.

- Leveraging Public Data: Proactively monitoring public data sources, such as the FDA’s FAERS database or EudraVigilance, for signals related to their active ingredient.

- Collaboration: Participating in industry forums and safety-sharing consortia to pool knowledge and resources.

5. What is the role of Real-World Evidence (RWE) in a generic’s RMP submission, as opposed to post-market surveillance?

While RWE’s primary role is in post-market surveillance, it can play a valuable part in the RMP itself, particularly for an updated RMP. If a generic has been marketed in other regions before seeking approval in the EU or US, RWD from that real-world use can be included in the RMP submission. This data can provide powerful evidence to support the product’s safety profile, characterize its use in diverse populations not studied by the innovator, and demonstrate the effectiveness of any risk minimization measures that were implemented. This proactive use of RWE can strengthen the submission and demonstrate a company’s commitment to ongoing safety evaluation.45

References

- Report: 2022 U.S. Generic and Biosimilar Medicines Savings Report, accessed July 31, 2025, https://accessiblemeds.org/resources/reports/2022-savings-report/

- Office of Generic Drugs 2022 Annual Report – FDA, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/generic-drugs/office-generic-drugs-2022-annual-report

- Drug Competition Series – Analysis of New Generic Markets Effect of Market Entry on Generic Drug Prices – HHS ASPE, accessed July 31, 2025, https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/510e964dc7b7f00763a7f8a1dbc5ae7b/aspe-ib-generic-drugs-competition.pdf

- The Global Generic Drug Market: Trends, Opportunities, and Challenges – DrugPatentWatch, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-global-generic-drug-market-trends-opportunities-and-challenges/

- Top 10 Challenges in Generic Drug Development …, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/top-10-challenges-in-generic-drug-development/

- Comparing Generic and Innovator Drugs: A Review of 12 Years of Bioequivalence Data from the United States Food and Drug Administration – NATAP, accessed July 31, 2025, https://natap.org/2016/HIV/AnnPharmacother2009-Davit1583-97.pdf

- Common deficiencies in generic drug product development – the University of Bath’s research portal, accessed July 31, 2025, https://researchportal.bath.ac.uk/en/publications/common-deficiencies-in-generic-drug-product-development

- Comparing generic and innovator drugs: a review of 12 years of bioequivalence data from the United States Food and Drug Administration – PubMed, accessed July 31, 2025, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19776300/

- Risk Management Plans (RMPs): Comprehensive Pharmacovigilance Guide – CCRPS, accessed July 31, 2025, https://ccrps.org/clinical-research-blog/risk-management-plans-rmps-comprehensive-pharmacovigilance-guide

- Overview: Pharmacovigilance and Risk Management – Journal For Clinical Studies, accessed July 31, 2025, https://journalforclinicalstudies.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/Overview_Pharmacovigilance-and-Risk-Management.pdf

- Industrial Policy To Reduce Prescription Generic Drug Shortages, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.americanprogress.org/article/industrial-policy-to-reduce-prescription-generic-drug-shortages/

- Guidance on the format of the risk management plan (RMP) in the EU – European Medicines Agency, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/regulatory-procedural-guideline/guidance-format-risk-management-plan-rmp-eu-integrated-format-rev-201_en.pdf

- Guideline on good pharmacovigilance practices (GVP) Module V – Risk management systems (Rev 2) – European Medicines Agency, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/guideline-good-pharmacovigilance-practices-module-v-risk-management-systems-rev-2_en.pdf

- Risk management plans | European Medicines Agency (EMA), accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/human-regulatory-overview/marketing-authorisation/pharmacovigilance-marketing-authorisation/risk-management/risk-management-plans

- EMA & FDA: What Are the Similarities & Differences in Risk Management Procedures?, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.biomapas.com/ema-and-fda-risk-management/

- Risk management plan | Medicines Evaluation Board – CBG-Meb, accessed July 31, 2025, https://english.cbg-meb.nl/topics/mah-risk-management-plan

- FDA’s Role in Managing Medication Risks, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/risk-evaluation-and-mitigation-strategies-rems/fdas-role-managing-medication-risks

- FDA Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS): Description and Effect on Generic Drug Development | Congress.gov, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/R44810

- Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies | REMS | FDA, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/risk-evaluation-and-mitigation-strategies-rems

- Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) about REMS – FDA, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/risk-evaluation-and-mitigation-strategies-rems/frequently-asked-questions-faqs-about-rems

- From Our Perspective | A Two-Part Series: Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS) Program | FDA, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/our-perspective/our-perspective-two-part-series-risk-evaluation-and-mitigation-strategies-rems-program

- FDA Releases Two Draft Guidances on REMS – Big Molecule Watch, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.bigmoleculewatch.com/2018/06/01/fda-releases-two-draft-guidances-on-rems/

- Risk management plans in the EU: Managing safety concerns – Medical Writing, accessed July 31, 2025, https://journal.emwa.org/eu-regulations/risk-management-plans-in-the-eu-managing-safety-concerns/article/6001/risk-management-plans-in-the-eu.pdf

- Risk Management Plans: reassessment of safety concerns based on Good Pharmacovigilance Practices Module V (Revision 2)—a company experience – PMC, accessed July 31, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9069847/

- A shot at demystifying the risk management plan for medical writers, accessed July 31, 2025, https://journal.emwa.org/risk-management/a-shot-at-demystifying-the-risk-management-plan-for-medical-writers/article/1461/2047480615z2e000000000288.pdf

- How to Develop a Risk Management Plan for Generic Drugs …, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/how-to-develop-a-risk-management-plan-for-generic-drugs/

- Submitting risk management plans for medicines and biologicals …, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.tga.gov.au/resources/guidance/submitting-risk-management-plans-medicines-and-biologicals

- New 2023 FDA Guidance on REMS: What’s New? – MMS Holdings, accessed July 31, 2025, https://mmsholdings.com/perspectives/new-2023-fda-guidance-on-rems-whats-new/

- Back to Basics – The Risk Management Plan (RMP) | European …, accessed July 31, 2025, https://eureg.ie/back-to-basics-the-risk-management-plan-rmp/

- REMS Abuse Impeding Patient Access to Generic Drugs – Myths and Facts, accessed July 31, 2025, https://accessiblemeds.org/resources/blog/rems-abuse-impeding-patient-access-generic-drugs-myths-and-facts/

- RMP requirements, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.tga.gov.au/sites/default/files/presentation-rmp-requirements-when-and-why-rmp-required.pdf

- The Safety Evaluation and Surveillance of Generic Drugs – FDA, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/media/163517/download

- Comparative Risk Assessment of Formulation Changes in Generic Drug Products: A Pharmacology/Toxicology Perspective – Oxford Academic, accessed July 31, 2025, https://academic.oup.com/toxsci/article/146/1/2/1661770

- Best Practices to Reduce Impurities in Generics – ProPharma, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.propharmagroup.com/thought-leadership/best-practices-to-reduce-impurities-in-generics

- Medication Risk Management – PMC – PubMed Central, accessed July 31, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7643709/

- The Role of Risk Assessment in Generic Drug Development – DrugPatentWatch, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-role-of-risk-assessment-in-generic-drug-development/

- Risk Management for Avoidance of Drug Shortages | Pharmaceutical Engineering, accessed July 31, 2025, https://ispe.org/pharmaceutical-engineering/september-october-2023/risk-management-avoidance-drug-shortages

- Quality Risk Management in Pharmaceutical Manufacturing Operations: Case Study for Sterile Product Filling and Final Product Handling Stage – MDPI, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/14/15/9618

- Risk Management in Pharmacovigilance | Freyr Solutions, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.freyrsolutions.com/medicinal-products/risk-management-pharmacovigilance

- Ensuring the Safety of FDA-Approved Generic Drugs, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/cder-conversations/ensuring-safety-fda-approved-generic-drugs

- Pharmacovigilance obligations of the pharmaceutical companies in India – PMC, accessed July 31, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3038525/

- Best Practices for FDA Staff in the Postmarketing Safety Surveillance of Human Drug and Biological Products, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/media/130216/download

- Real-World Evidence | FDA, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/science-research/science-and-research-special-topics/real-world-evidence

- Collection and Use of Real-World Data Continues to Grow Around the World | Pfizer, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.pfizer.com/news/articles/collection_and_use_of_real_world_data_continues_to_grow_around_the_world

- The Role of Real-World Evidence (RWE) in Drug Development: ProRelix Research Insights, accessed July 31, 2025, https://prorelixresearch.com/the-role-of-real-world-evidence-rwe-in-drug-development-prorelix-research-insights/

- Integrating Real-World Evidence in the Regulatory Decision-Making Process: A Systematic Analysis of Experiences in the US, EU, and China Using a Logic Model – PMC – PubMed Central, accessed July 31, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8200400/

- The Role of Pharmacovigilance in Real-World Evidence (RWE) Generation, accessed July 31, 2025, https://propharmaresearch.com/en/resources/diffusion/role-pharmacovigilance-real-world-evidence-rwe-generation

- The use of real-world data in drug development – PhRMA, accessed July 31, 2025, https://phrma.org/blog/the-use-of-real-world-data-in-drug-development

- DrugPatentWatch | Software Reviews & Alternatives – Crozdesk, accessed July 31, 2025, https://crozdesk.com/software/drugpatentwatch

- Drug Patent Watch – GreyB, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.greyb.com/services/patent-search/drug-patent-watch/

- DrugPatentWatch not only saved us valuable time in tracking patent …, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/

- Patents on Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies for Prescription Drugs and Generic Competition – PMC, accessed July 31, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10884947/

- ich harmonised tripartite guideline – pharmacovigilance planning e2e, accessed July 31, 2025, https://database.ich.org/sites/default/files/E2E_Guideline.pdf

- Stringent Environmental Risk Assessments for Generic Drugs – Blue Frog Scientific, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.bluefrogscientific.com/chemical-regulatory-news-and-views/stringent-environmental-risk-assessments-generic-drugs

- Submitting risk management plans guidance document: Preparing and submitting an RMP – Canada.ca, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/drugs-health-products/reports-publications/medeffect-canada/guidance-submission-risk-management-plans-policy-overview/preparing-submitting.html