Introduction: The PTAB Paradox—Innovation’s Shield or Achilles’ Heel?

The modern pharmaceutical industry is built upon a foundational paradox: the pursuit of public health is fueled by a system of temporary, private monopoly. This system, enshrined in patent law, is the bedrock of a business model that requires staggering upfront investment to navigate the treacherous path from laboratory discovery to patient bedside.1 The cost of developing a single new drug now routinely exceeds $2 billion, a process that can span more than a decade.3 In exchange for this immense risk and the public disclosure of their innovations, pharmaceutical companies are granted a period of market exclusivity. This exclusivity is not merely a reward; it is the economic engine that allows companies to recoup their vast research and development (R&D) expenditures and, critically, to fund the next generation of life-saving medicines.2 Without this protection, the incentive to innovate would evaporate, leaving pipelines barren and unmet medical needs unanswered.

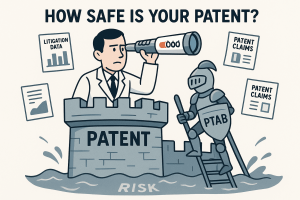

For decades, the primary threat to this delicate balance was the courtroom—a costly, slow, and often unpredictable forum for patent litigation. That all changed in 2011 with the passage of the Leahy-Smith America Invents Act (AIA). The AIA was a sweeping reform of U.S. patent law, and at its heart was the creation of a new administrative tribunal within the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO): the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB).5 The PTAB was born of noble intentions: to create a faster, cheaper, and more efficient mechanism for reviewing the validity of issued patents, thereby improving overall patent quality and weeding out improvidently granted claims.8 However, for the biopharmaceutical industry, this new body quickly became a source of profound anxiety. With its high rates of claim cancellation, the PTAB was soon branded by some critics as a “death squad for patents,” a powerful new weapon in the arsenal of generic and biosimilar challengers that threatened the very foundation of the pharmaceutical innovation model.1

This report will argue that navigating the risks and opportunities presented by the PTAB has transcended the confines of the legal department to become a core strategic imperative for C-suite leaders, portfolio managers, and investors across the pharmaceutical landscape. The question is no longer simply if a blockbuster drug’s patent portfolio will be challenged at the PTAB, but when, how, and with what consequences for the company’s bottom line. To survive and thrive in this new era, industry leaders must cultivate a deeply integrated understanding of the PTAB’s legal framework, the powerful economic forces that fuel its proceedings, and the evolving procedural doctrines that govern its outcomes. Success requires moving beyond a reactive, defensive posture to proactively leveraging this knowledge for competitive advantage—fortifying patent portfolios, stress-testing assets during due diligence, and making smarter R&D investment decisions. This is the new reality of patent strategy in the age of the PTAB.

Section 1: Understanding the Arena—What is the PTAB and Why Was It Created?

To effectively counter the threat posed by the PTAB, or to wield it as an offensive weapon, one must first understand the arena itself. The PTAB is not merely a smaller, faster version of a federal court; it is a fundamentally different kind of adjudicative body, with its own unique structure, rules, and strategic implications. Its creation represented a deliberate congressional effort to shift a significant portion of patent validity disputes from the judicial branch to an expert administrative agency.

1.1 From Courtroom to Boardroom: The Legislative Intent of the America Invents Act

The genesis of the PTAB lies in a growing consensus in the early 2000s that the U.S. patent litigation system was becoming excessively costly, slow, and inefficient.8 Congress identified a clear need for a centralized, lower-cost administrative system to adjudicate patent validity.8 The stated goals were twofold: to improve the overall quality and reliability of U.S. patents by providing a robust post-grant corrective mechanism, and to reduce the burden of unwarranted and expensive litigation.8 A particular target of the legislation was the perceived problem of “patent trolls”—non-practicing entities that acquire patents solely to assert them against operating companies and extract nuisance-value settlements.11 The PTAB was thus designed to be a more accessible forum where questionable patents could be challenged and invalidated more efficiently than in a full-blown district court case, which can take years and cost millions of dollars.9

1.2 The Anatomy of the PTAB: Structure, Judges, and Mandate

The AIA dissolved the USPTO’s previous appellate body, the Board of Patent Appeals and Interferences (BPAI), and reconstituted it as the PTAB.6 The PTAB is a tribunal within the USPTO, composed of statutory members (the USPTO Director, Deputy Director, and Commissioners) and a large corps of Administrative Patent Judges (APJs).5

A defining and critical feature of the PTAB is the composition of its judiciary. Unlike federal district court judges, who are generalists responsible for a wide array of legal matters, APJs are specialists. They are required to have both legal and technical training and are appointed by the Secretary of Commerce based on their extensive experience in patent law.12 Many APJs have backgrounds in private practice, as in-house counsel, or at other government agencies like the International Trade Commission, and often possess advanced degrees in science and technology.12 This deep technical expertise fundamentally alters the dynamic of a patent dispute. Arguments that might succeed in confusing a lay jury or a generalist judge are unlikely to persuade a panel of three APJs who are, in effect, expert peers of the inventors and attorneys before them. This reality demands a higher level of technical and legal rigor from both patent owners and challengers.

The authority of these judges has itself been a subject of legal evolution. In the landmark 2021 case United States v. Arthrex, Inc., the Supreme Court addressed a constitutional challenge to the appointment of APJs. The Court held that because APJs could issue final, binding decisions on behalf of the Executive Branch without review by a superior officer, their appointment was unconstitutional.6 The remedy was not to dismantle the PTAB, but to make its final written decisions subject to review by the Director of the USPTO, a presidentially appointed officer. This decision created the “Director Review” process, adding a new layer of strategic consideration and placing the PTAB’s adjudicative outcomes under the ultimate discretionary control of the agency’s political leadership.8

1.3 The Challenger’s Toolkit: A Deep Dive into IPR and PGR Proceedings

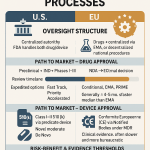

The AIA endowed the PTAB with the authority to conduct several new trial-like administrative proceedings. For the pharmaceutical industry, the two most significant are Inter Partes Review (IPR) and Post-Grant Review (PGR). Understanding the distinctions between these two proceedings is crucial for assessing risk and formulating strategy.

Inter Partes Review (IPR): The IPR is the workhorse of the PTAB and the most common vehicle for challenging drug patents.14 An IPR petition can be filed by any person who is not the patent owner, but only after a certain window of time has passed: for most patents, this is nine months after the patent’s grant or reissue.15 The grounds for an IPR challenge are narrowly circumscribed. A petitioner can only argue that a patent is invalid for lack of novelty (under 35 U.S.C. § 102) or for being obvious (under 35 U.S.C. § 103).16 Furthermore, the evidence that can be used to support these arguments is limited to prior art consisting of patents and printed publications.16 Other invalidity defenses, such as lack of written description or enablement, cannot be raised in an IPR.

Post-Grant Review (PGR): The PGR is a more powerful, but more time-limited, tool. A PGR petition must be filed within nine months of a patent’s grant or reissue.15 Unlike an IPR, a PGR allows a petitioner to challenge a patent on any ground of invalidity, including the broader grounds available under 35 U.S.C. § 112, such as lack of enablement, lack of written description, or indefiniteness.15 This makes PGR a particularly potent weapon against newly issued patents, especially those in complex fields like biologics where enablement and written description are often contentious issues.

A critical concept that applies to both proceedings is estoppel. If the PTAB issues a final written decision in an IPR or PGR, the petitioner is legally barred (or “estopped”) from later asserting in a district court or ITC proceeding that a claim is invalid on any ground that the petitioner “raised or reasonably could have raised” during the PTAB proceeding.15 This provision makes the decision to file a PTAB petition a high-stakes gambit. A loss at the PTAB can severely cripple a challenger’s ability to defend itself in a subsequent infringement lawsuit.

The following table provides a clear, at-a-glance comparison of these two critical proceedings, distilling complex procedural rules into a strategic framework for business leaders.

| Feature | Inter Partes Review (IPR) | Post-Grant Review (PGR) |

| Filing Window | Beginning 9 months after patent grant 15 | Within 9 months of patent grant 15 |

| Applicable Patents | All issued patents | Only patents filed under the first-inventor-to-file system (post-March 2013) 15 |

| Grounds for Challenge | Novelty (§ 102) and Obviousness (§ 103) based on patents and printed publications only 16 | Any ground of invalidity, including § 101 (eligibility), § 102, § 103, and § 112 (enablement, written description, indefiniteness) 15 |

| Burden of Proof | Unpatentability by a “preponderance of the evidence” 8 | Unpatentability by a “preponderance of the evidence” 8 |

| Estoppel Effect | Petitioner is estopped from raising grounds in other forums that were raised or reasonably could have been raised 15 | Petitioner is estopped from raising grounds in other forums that were raised or reasonably could have been raised 15 |

| Strategic Use Case | Challenging established patents, often in parallel with district court litigation. The primary tool for generic/biosimilar challengers. | An early, powerful strike against a competitor’s newly issued key patent, leveraging a wider range of invalidity arguments. |

The very design of the PTAB, staffed by technically sophisticated APJs, represents a paradigm shift in patent adjudication. Innovators can no longer rely on the inherent complexity of their technology to create a “fog of war” in front of a generalist judge or a lay jury. The PTAB is not just a different venue; it is a different type of battle. The risk profile shifts from persuading a non-expert to convincing a panel of highly qualified specialists. This environment necessitates a more rigorous, evidence-based, and scientifically nuanced approach to both patent prosecution and defense, as expert testimony and technical arguments will be subjected to a level of scrutiny rarely seen in a traditional courtroom setting.21

Section 2: The Economic Engine of Conflict—Why Drug Patents are Prime Targets

The high frequency of PTAB challenges against pharmaceutical patents is not a random phenomenon. It is the direct result of powerful and deeply entrenched economic forces, codified in legislation that simultaneously seeks to reward innovation and promote competition. The immense financial rewards for successfully invalidating a drug patent have transformed the PTAB from a simple legal venue into an integral component of the business model for generic and biosimilar companies, and even a tool for financial market speculation.

2.1 The Generic Gold Rush: The Hatch-Waxman Act’s Double-Edged Sword

The modern generic drug industry was born in 1984 with the passage of the Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act, commonly known as the Hatch-Waxman Act.2 This landmark legislation created an abbreviated pathway for generic drug approval, the Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA), which allows a generic manufacturer to rely on the brand-name drug’s safety and efficacy data, demonstrating only bioequivalence.22

To balance this pro-competition measure, the Act also created a powerful incentive for generics to challenge patents they believe are invalid or not infringed. A generic company can file its ANDA with a “Paragraph IV certification,” asserting that a patent listed in the FDA’s Orange Book is invalid, unenforceable, or will not be infringed by the generic product.3 This filing is a strategic masterstroke: it is considered an act of “artificial infringement” that allows patent litigation to begin before the generic product even launches.23

The true genius of the system, from the challenger’s perspective, is the prize for being the first to the courthouse. The first generic company to file a substantially complete ANDA with a Paragraph IV certification is rewarded with a 180-day period of marketing exclusivity upon approval.19 During this six-month period, the first-filer generic can often capture significant market share and earn substantial profits, as it typically faces competition only from the branded drug, not from other generics.22 This 180-day exclusivity has been described as the “holy grail” for generic companies, creating a powerful “race to challenge” patents for commercially successful products, even when the probability of success is low.19

2.2 The Next Wave: The BPCIA and the Dawn of the Biosimilar Era

What the Hatch-Waxman Act did for small-molecule generic drugs, the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA) of 2010 did for the next frontier of medicine: biologics.20 Biologics are large, complex molecules derived from living organisms, and they represent a rapidly growing share of the pharmaceutical market.26 The BPCIA created an abbreviated licensure pathway for “biosimilars”—products that are “highly similar” to an already-approved biologic (the “reference product”) with “no clinically meaningful differences” in terms of safety, purity, and potency.20

The BPCIA also established a unique, highly structured process for resolving patent disputes prior to a biosimilar launch, colloquially known as the “patent dance”.20 This process involves a series of timed information exchanges where the biosimilar applicant discloses its manufacturing process and the brand-name sponsor (or Reference Product Sponsor) identifies patents it believes would be infringed.20 The patent dance is designed to narrow the scope of potential litigation. However, it is a complex and strategic chess match where PTAB challenges play a crucial role. A biosimilar developer can use an IPR or PGR to proactively challenge the patents identified by the brand company, seeking to invalidate them in a faster, more favorable forum. A successful PTAB challenge can provide the biosimilar company with “freedom to operate,” clearing the path for market entry and providing significant leverage in any settlement negotiations.20

2.3 The Financial Imperative: Billions in Revenue at the “Patent Cliff”

The motivation for these challenges is rooted in simple, brutal economics. For blockbuster drugs, patent expiration is not a gentle slope but a sheer “patent cliff”.3 Upon generic or biosimilar entry, brand-name drug revenues can plummet by 80-90% almost overnight.3 The stakes are astronomical. Between 2025 and 2030, an estimated $236 billion in global pharmaceutical revenue is at risk due to patent expirations.3 The global biosimilar market alone was valued at $26.5 billion in 2024 and is projected to skyrocket to $185.1 billion by 2033, a clear indicator of the massive transfer of wealth that occurs when patent protection ends.26

This impending revenue loss creates an overwhelming financial imperative for challengers to do everything in their power to accelerate that date, even by a few months. Every day that a generic or biosimilar can enter the market earlier is a day of enormous potential profit. This dynamic ensures that any patent protecting a commercially successful drug will be scrutinized with extreme prejudice by a host of potential challengers looking for any weakness to exploit.

2.4 The Challenger’s Calculus: Favorable Economics and a Lower Burden of Proof

The creation of the PTAB dramatically altered the challenger’s risk-reward calculus. Before the AIA, challenging a patent meant engaging in protracted and astronomically expensive district court litigation. The PTAB offers a far more attractive alternative.8

First, it is significantly faster and cheaper. A PTAB trial is statutorily mandated to conclude within 12 months of institution, a stark contrast to the multi-year timeline of a typical district court case.16 The costs are also an order of magnitude lower, typically in the hundreds of thousands of dollars for a PTAB trial versus millions for district court litigation.17

Second, and most importantly, the legal standard for invalidating a patent is lower at the PTAB. In federal court, an issued patent enjoys a strong presumption of validity. To overcome this, a challenger must prove invalidity by “clear and convincing evidence”—a high legal bar.8 At the PTAB, there is no presumption of validity. The challenger must only prove a claim is unpatentable by a “preponderance of the evidence”.8 This standard essentially means showing that it is “more likely than not” (i.e., >50% probability) that the claim is invalid. This lower evidentiary threshold makes it demonstrably easier for a challenger to succeed at the PTAB than in court.9

The accessibility and challenger-friendly nature of the PTAB have led to consequences that Congress likely never anticipated. The forum has been used not just by generic and biosimilar competitors seeking to bring products to market, but also by financial actors with no intention of ever producing a drug. In a series of high-profile cases, hedge funds have filed IPR petitions against pharmaceutical companies while simultaneously “shorting” their stock—betting that the stock price will fall.11 The public filing of the IPR petition itself creates uncertainty and can drive down the company’s stock price, allowing the hedge fund to profit regardless of the IPR’s ultimate outcome.11 This practice reveals that the PTAB has evolved beyond its intended purpose as a check on patent quality. It has become a powerful tool in the financial markets, demonstrating that a patent holder’s risk assessment must now account not only for legitimate commercial competitors but also for purely financial predators—a threat that was far less pronounced in the era of expensive, high-stakes district court litigation.

Section 3: The Threat by the Numbers—A Statistical Analysis of PTAB Outcomes

While the “death squad” narrative is a powerful one, a nuanced understanding of the PTAB threat requires moving beyond anecdotes and examining the statistical reality of how pharmaceutical patents fare in this forum. The data reveals a complex picture: while the odds of a challenge being instituted are alarmingly high for pharma companies, the ultimate outcome is highly dependent on the type of patent being challenged. The numbers show that the PTAB is less of an indiscriminate killer of all drug patents and more of a highly effective sniper targeting specific vulnerabilities in a company’s intellectual property portfolio.

3.1 Decoding the Data: Institution Rates in the Bio/Pharma Sector

The first hurdle for any PTAB challenge is the institution decision. The PTAB reviews the petition and the patent owner’s preliminary response to determine if there is a “reasonable likelihood that the petitioner would prevail with respect to at least one of the claims challenged”.16 If this standard is met, the trial is instituted.

This is where the data for the biopharmaceutical sector is most stark. According to USPTO statistics, petitions challenging bio/pharma patents consistently have among the highest institution rates of any technology sector.14 In Fiscal Year 2022, the institution rate for bio/pharma petitions was a staggering 77%, significantly higher than the 68% for the dominant electrical/computer sector and the 66% for mechanical/business method patents.14 More recent data from FY24 shows a similar trend, with bio/pharma petitions being instituted 73% of the time, again the highest rate among major technology areas.28

This single statistic is a crucial indicator of the threat level. It means that for a pharmaceutical patent owner, once an IPR petition is filed against one of its patents, there is a roughly three-in-four chance that it will proceed to a full trial on the merits. This high probability of institution is a powerful source of leverage for challengers and a primary driver of pre-decision settlements.

3.2 The “Death Squad” Narrative: A Critical Look at Invalidation Rates

The perception of the PTAB as a patent graveyard is fueled by its high overall invalidation rates. Across all technologies, the rate at which PTAB final written decisions find all challenged claims unpatentable has been steadily increasing, rising from 55% in 2019 to 70% in 2024.29 On a per-claim basis, the numbers are even more daunting: in 2024, nearly 78% of all claims that went to a final decision were found invalid.29

However, these top-line numbers mask a more complex and critical reality for the pharmaceutical industry. When the analysis is narrowed to focus specifically on patents listed in the FDA’s Orange Book—the patents most directly protecting approved drug products—the picture changes dramatically. A comprehensive 2018 study found that the rate of complete invalidation (where all challenged claims are lost) for Orange Book patents at the PTAB was 23%.30 Strikingly, this was almost identical to the complete invalidation rate of 24% for the same types of patents in district court litigation over the same period.30

The data becomes even more granular when broken down by patent type:

- Compound Patents: These patents, which cover the core active pharmaceutical ingredient (API), are the crown jewels of any portfolio. They are also exceptionally resilient. The study found no instances of a compound patent for an Orange Book drug being completely invalidated at the PTAB.30

- Formulation Patents: These patents, which cover how a drug is prepared and delivered, are more vulnerable. They were completely invalidated 15% of the time at the PTAB.30

- Method of Treatment Patents: These patents, covering the use of a drug for a specific disease, are the most susceptible to challenge. They were completely invalidated 27% of the time at the PTAB.30

This data leads to a crucial strategic conclusion. The high institution rate for bio/pharma petitions is not driven by challenges to foundational compound patents. Instead, it is fueled by petitions targeting the weaker secondary patents that make up a drug’s “patent thicket.” The PTAB is not, by and large, destroying the patents on core molecular innovations. Rather, it is functioning as a highly effective filter for weeding out less inventive follow-on patents related to formulations and new uses. Its primary impact is the accelerated erosion of the lifecycle management strategies that companies use to extend a drug’s market exclusivity. The core invention is likely safe; the long tail of that exclusivity is at high risk.

3.3 Beyond Invalidation: The Pervasive Impact of Strategic Settlements

Perhaps the most overlooked statistic in PTAB outcomes is the high rate of settlements. A significant percentage of proceedings are terminated after institution but before the PTAB can issue a final written decision because the parties have reached a settlement.14 In FY24, for example, 32% of all terminated petitions ended in settlement, a figure comparable to the 38% that went to a final written decision.28

This highlights a key strategic reality of the PTAB. For a patent owner, the combination of a high institution rate and the inherent uncertainty of a trial creates immense pressure to settle. For a challenger, securing a settlement that allows for market entry on a date prior to patent expiration can be a massive commercial victory, achieved without the risk and expense of seeing the litigation through to the very end.22 The mere institution of an IPR is often enough to bring the patent owner to the negotiating table. Therefore, viewing PTAB outcomes as a simple binary of “win” or “loss” is misleading. For many, the most common and strategically important outcome is a negotiated peace.

The following table synthesizes recent data to provide a nuanced, data-driven view of the PTAB risk landscape, moving beyond the simplistic “death squad” narrative to highlight the specific vulnerabilities and outcomes relevant to pharmaceutical companies.

| Metric | Bio/Pharma | Electrical/Computer | All Technologies (Average) |

| Petitions Filed (FY24 % of Total) | 6% 28 | 69% 28 | 100% |

| Institution Rate (per petition, FY24) | 73% 28 | 69% 28 | 68% 29 |

| Final Decisions w/ All Claims Unpatentable (%) | 23% (Orange Book) 30 | ~70% (Overall) 29 | ~70% (Overall) 29 |

| Final Decisions w/ At Least One Claim Surviving (%) | 77% (Orange Book) 30 | ~30% (Overall) 29 | ~30% (Overall) 29 |

| Proceedings Terminated via Settlement (FY24 %) | 32% 28 | 32% 28 | 32% 28 |

Note: Invalidation and survival rates for Bio/Pharma are based on a 2018 study of Orange Book patents, as this provides the most relevant data for approved drugs. Overall rates reflect more recent data across all technologies.

Section 4: The Shifting Rules of Engagement—Pivotal Legal Precedents and Doctrines

The PTAB does not operate in a vacuum. Its power, procedures, and strategic landscape are continuously shaped by decisions from the U.S. Supreme Court and by the evolving internal policies of the USPTO itself. For pharmaceutical leaders, understanding these shifting rules of engagement is just as important as understanding the underlying science of their patents. Recent years have seen a dramatic evolution in the doctrines governing when the PTAB can and will exercise its discretion to deny a petition, transforming the strategic calculus for both patent owners and challengers.

4.1 The Supreme Court Weighs In: Landmark Cases Defining the PTAB’s Power

Since the PTAB’s inception, its very existence and authority have been tested at the nation’s highest court. A series of landmark decisions has cemented the PTAB’s legal foundation while also defining the boundaries of its power.

- Oil States Energy Services, LLC v. Greene’s Energy Group, LLC (2018): This was the most fundamental challenge to the PTAB’s legitimacy. The petitioner argued that revoking a patent is a function reserved for Article III federal courts and that an administrative agency could not constitutionally perform this role. The Supreme Court disagreed, upholding the IPR process.6 It reasoned that the grant of a patent is a “public right” or a “public franchise,” not a private property right in the traditional sense. Therefore, Congress had the constitutional power to authorize an administrative body to reconsider and cancel that grant.8 This decision firmly established the PTAB’s constitutional authority to invalidate patents.

- SAS Institute Inc. v. Iancu (2018): This case addressed a key procedural issue. The PTAB had a practice of “partial institution,” where it would agree to institute a trial on only a subset of the claims challenged in a petition. The Supreme Court struck down this practice, holding that the AIA’s language requires the PTAB to address every claim a petitioner challenges if it decides to institute a trial at all.8 This “all-or-nothing” approach increased the stakes for both sides, forcing the PTAB to confront the full scope of a challenge once the institution threshold is met.

- Cuozzo Speed Technologies, LLC v. Lee (2016) and Thryv, Inc. v. Click-To-Call Technologies, LP (2020): These two cases significantly bolstered the PTAB’s gatekeeping power. In Cuozzo, the Court held that the PTAB’s decision on whether to institute a trial is “final and nonappealable,” insulating this critical function from judicial review.8

Thryv expanded on this, ruling that the bar on appeals also covers the PTAB’s determination of whether a petition was filed within the statutory one-year time limit.8 Together, these decisions mean that once the PTAB decides to start a trial, that decision is largely immune from challenge in the courts, making the institution decision a moment of maximum leverage.

“When we developed these proceedings, we never thought people would use them this way, in an effort to move stock or as an investment vehicle.”

— Bernard Knight, former general counsel for the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, as quoted in Bloomberg.11

This observation from one of the architects of the post-grant system underscores the unintended consequences that have emerged. The PTAB’s efficiency and accessibility, while designed to curb litigation abuse, inadvertently created new avenues for financially motivated challenges that were not part of the original legislative vision, prompting the USPTO to seek ways to manage its own creation.

4.2 The Discretionary Denial Pendulum: Navigating the Fintiv Doctrine

The most dynamic and strategically significant area of PTAB practice in recent years has been the doctrine of discretionary denial. While the PTAB may institute a trial if the petition meets the statutory threshold, it is not required to do so. The statute gives the Board discretion to deny a petition for other reasons.31 This discretion has become a major battleground, particularly in cases involving parallel litigation.

In 2020, the PTAB designated its decision in Apple Inc. v. Fintiv, Inc. as precedential. The Fintiv decision articulated a six-factor test for determining whether to deny an IPR petition when a parallel case involving the same patent is pending in district court.31 The factors include the proximity of the court’s trial date to the PTAB’s deadline for a final decision, the degree of investment by the court and the parties in the parallel case, and the overlap in issues between the two proceedings.31

The application of Fintiv has been a “pendulum swing” 32:

- Broad Application (2020-2022): Initially, the PTAB applied the Fintiv factors broadly, leading to a significant number of discretionary denials, much to the consternation of petitioners. This created a strategic incentive for patent owners to try to “race to trial” in district court to create a compelling argument for a Fintiv denial at the PTAB.32

- The Vidal Memo (2022-2025): In response to criticism that Fintiv was being applied too aggressively, then-USPTO Director Kathi Vidal issued a memorandum that significantly curtailed its use. The memo established what was effectively a “safe harbor”: the PTAB would not deny institution under Fintiv if the petitioner stipulated that it would not pursue the same invalidity arguments in court (a Sotera stipulation) or if the petition presented a “compelling” merits case.31

- Rescission and Return to Discretion (2025-Present): In early 2025, the USPTO rescinded the Vidal memorandum, signaling a dramatic return to broader PTAB discretion.31 The announcement directed parties to once again rely on the original

Fintiv precedent, making the Sotera stipulation relevant but no longer a dispositive get-out-of-jail-free card.31

This reversal has profound strategic implications. The timing of an IPR filing relative to district court litigation is now more critical than ever. Petitioners must file as early as possible to minimize the risk of a Fintiv denial, while patent owners have a renewed incentive to expedite their court cases to build a strong case for PTAB denial.31

4.3 The New Frontier: “Settled Expectations” and Its Chilling Effect

More recently, a new and potentially more potent form of non-merits-based discretionary denial has emerged directly from the USPTO Director’s office: the doctrine of “settled expectations”.33 In a pair of 2025 decisions,

iRhythm and Dabico, the Acting Director denied institution of IPRs against patents that had been in force for many years (eight years in one case).33 The reasoning was that the patent owner and the public had developed a “settled expectation” of the patent’s validity over time, and that challenging it so late in its life was not an appropriate use of USPTO resources, regardless of the merits of the challenge.33

This emerging doctrine has particularly chilling implications for the pharmaceutical industry. The Director’s office has indicated that the listing of a patent in the FDA’s Orange Book provides strong public notice of the patent’s existence and relevance.33 This suggests that the “settled expectations” clock may start ticking for a drug patent as soon as it is listed in the Orange Book. This creates a powerful incentive for generic and biosimilar challengers to file PTAB petitions

much earlier in their development cycle than they have traditionally done, possibly years before they are ready to file their ANDA or BLA with the FDA. Failure to do so could risk having their later challenge denied simply because too much time has passed.

The evolution of these discretionary denial doctrines, from the merit-adjacent analysis of Fintiv to the entirely non-merit-based concept of “settled expectations,” reveals a significant policy shift within the USPTO. Faced with persistent criticism that the PTAB system had swung too far in favor of challengers, the agency’s leadership is actively using its inherent statutory discretion over institution as a powerful lever to rebalance the system. This procedural maneuvering, which does not require an act of Congress, adds a new layer of strategic complexity for all parties. Litigants must now anticipate not only their opponent’s legal arguments but also the prevailing policy winds blowing from the USPTO Director’s office.

Section 5: The Innovator’s Defensive Playbook—Fortifying Your Patent Portfolio

In an environment where high-value patents are under constant threat of challenge in a formidable administrative forum, a passive approach to intellectual property management is a recipe for disaster. For pharmaceutical innovators, patent defense is no longer a reactive exercise that begins when a lawsuit is filed; it is a proactive, continuous strategic function that must be woven into the fabric of the organization, from early-stage R&D to late-stage lifecycle management. The goal is to build a patent fortress so robust and resilient that it deters potential challengers or, failing that, can withstand the rigorous scrutiny of the PTAB.

5.1 The Art and Science of the “Patent Thicket”

A core defensive strategy in the modern pharmaceutical landscape is the deliberate construction of a “patent thicket.” This involves securing not just one foundational patent on a new drug, but a dense, multi-layered, and often overlapping web of numerous patents covering every conceivable aspect of the product.3 The strategic principle is clear: while a single patent might be a vulnerable target, a fortress with many walls is far more difficult and costly to breach.3

The construction of a patent thicket involves systematically filing for various types of secondary patents throughout a drug’s lifecycle. These include:

- Formulation Patents: Protecting the specific “recipe” of the final drug product, such as an extended-release formulation that improves patient compliance or a specific combination of inactive ingredients that enhances stability.4

- Method of Use Patents: Covering the use of the drug to treat a new disease or a specific patient subpopulation. This is the legal foundation of drug repurposing and can open up entirely new markets.4

- Manufacturing Process Patents: Protecting novel and proprietary methods used to synthesize the drug, which can be particularly important for complex biologics.4

- Polymorph and Enantiomer Patents: Protecting specific crystalline structures (polymorphs) or single mirror-image molecules (enantiomers) of the active ingredient that may offer improved therapeutic properties.4

- Delivery Device Patents: For drugs administered via a specific device, like an inhaler or an auto-injector, patents on the device itself create a separate and significant hurdle for competitors.4

The strategic value of a thicket lies not in the unassailable strength of any single secondary patent, but in its cumulative deterrent effect. A generic or biosimilar challenger must analyze and find a path around or through dozens, or in some cases hundreds, of patents. Each additional patent represents another potential lawsuit, another PTAB challenge, and another source of cost, complexity, and delay, making it economically prohibitive for many to even attempt a challenge.3

5.2 Proactive Prosecution: Inoculating Patents Against Future Challenges

The strongest defense begins long before a challenge is ever filed—during the patent prosecution process at the USPTO. A forward-thinking prosecution strategy anticipates future PTAB challenges and builds a record designed to withstand them.

One key tactic involves thoroughly addressing the prior art cited by the patent examiner during prosecution. By submitting arguments and evidence to distinguish the invention from this prior art, the patent owner builds a strong record that the USPTO has already considered these issues. This can be used later to argue for discretionary denial of a PTAB petition under 35 U.S.C. § 325(d), which allows the Board to reject a petition that raises the same or substantially the same arguments or art that were previously presented to the Office.35

Another powerful strategy is the use of continuation applications. While one patent application is pending, the applicant can file a “continuation” to pursue claims of a different scope or focus.19 This allows a company to build a family of related patents around a core invention. This creates multiple, distinct assets that a challenger must address, increasing the complexity and cost of any invalidity campaign and providing the patent owner with a variety of claim types to assert in litigation.

5.3 Defending an IPR: Procedural Tactics and the Power of Expert Testimony

Once an IPR petition is filed, the patent owner faces a series of critical strategic decisions. The first is whether to file a Patent Owner Preliminary Response (POPR). This optional filing is the patent owner’s only chance to rebut the petitioner’s arguments before the institution decision is made.16 It is a high-stakes document, as a poorly crafted POPR can lock the patent owner into a weak position, while a persuasive one can sometimes convince the PTAB to deny institution outright.

If the trial is instituted, the role of expert witnesses becomes paramount. Because the PTAB is a technically expert tribunal, the credibility and clarity of expert testimony can make or break a case.

“A well-constructed patent portfolio is like a chess game. Each patent is a piece on the board, strategically placed to defend your product and block competitors’ moves.”

— Dr. Jane Smith, patent attorney.36

Perfecting this testimony requires avoiding several common pitfalls 21:

- Conclusory and Unsupported Testimony: PTAB rules are clear that expert testimony that does not disclose the underlying facts or data on which it is based is entitled to “little or no weight”.21 An expert cannot simply repeat the arguments in a legal brief; they must provide detailed technical reasoning and cite corroborating evidence from the scientific literature or other sources.

- Improper Incorporation by Reference: Parties cannot use an expert declaration to circumvent the PTAB’s strict word count limits by incorporating arguments by reference. The core arguments must be in the brief itself, with the expert declaration providing support and elaboration.21

- Lacking Status as a Person of Ordinary Skill in the Art (POSITA): The expert witness must be qualified as a person of ordinary skill in the specific technical field of the patent. If an expert is deemed to lack this qualification, their testimony on key issues like obviousness may be disregarded entirely.21

The existence of the PTAB has created a fascinating feedback loop. The Board’s demonstrated effectiveness at invalidating weaker secondary patents—the very building blocks of a patent thicket—paradoxically encourages innovators to file more of them. The logic is one of attrition: if the probability of any single secondary patent surviving a challenge is lower, then the rational defensive strategy is to create a much larger portfolio of them. This increases the sheer number of targets a challenger must overcome, raising their overall cost and risk to a potentially prohibitive level. The Humira case, where AbbVie’s massive thicket ultimately forced most challengers into settlements despite some individual IPR losses, is a testament to this strategy’s effectiveness.17 Thus, the PTAB, a body intended to improve patent quality, may be inadvertently promoting a defensive strategy based on patent quantity.

Section 6: The Challenger’s Gambit—Strategies for Invalidating Drug Patents

While innovators build fortresses, challengers sharpen their siege weapons. For generic and biosimilar companies, the PTAB represents the single most powerful tool for dismantling a brand-name drug’s patent protection and accelerating market entry. A successful offensive strategy requires a combination of regulatory savvy, legal precision, and a deep understanding of the target’s vulnerabilities.

6.1 The Opening Salvo: The Paragraph IV Certification Pathway

For a generic challenger targeting a small-molecule drug, the campaign almost always begins with the regulatory filing of an ANDA containing a Paragraph IV certification.3 As discussed previously, this certification asserts that the patents listed in the Orange Book for the reference drug are invalid, unenforceable, or will not be infringed.19 This act serves as the formal notice of the challenge and is the trigger for the 45-day window in which the brand company can sue, thereby initiating a 30-month stay on FDA approval while the litigation proceeds.19 Filing this certification is the first critical step on the path to securing the lucrative 180-day first-filer exclusivity.19

6.2 Leveraging the PTAB: A Faster, Cheaper, and More Favorable Forum

The PTAB is the challenger’s preferred battlefield for several compelling reasons. The combination of its lower cost, faster timeline, technically expert adjudicators, and, most importantly, lower “preponderance of the evidence” burden of proof makes it a far more attractive forum for an invalidity challenge than a district court.17

A common and highly effective strategy is to file a PTAB petition in parallel with the district court litigation that is triggered by the Paragraph IV certification.3 This creates a two-front war for the patent owner. The threat of a relatively quick and high-probability loss at the PTAB can exert immense pressure on the patent owner, often forcing them to agree to a more favorable settlement in the district court case than they otherwise would have.27 The PTAB proceeding becomes a powerful lever to influence the outcome of the entire dispute.

6.3 Identifying the Weakest Links: Targeting the Thicket’s Outer Defenses

A savvy challenger rarely mounts a frontal assault on the strongest part of the fortress—the core composition of matter patent. These patents are notoriously difficult to invalidate.30 Instead, the strategy is to probe for weaknesses in the outer defenses of the patent thicket.19 Challengers meticulously analyze the portfolio to identify the most vulnerable secondary patents, which are often those covering formulations, dosing regimens, or methods of use.19 These patents are typically filed later in a drug’s life and are often based on more incremental innovations, making them more susceptible to obviousness challenges, especially under the flexible “obvious to try” standard established by the Supreme Court in

KSR v. Teleflex.17 By successfully invalidating a few key secondary patents, a challenger can begin to punch holes in the thicket, creating a clearer path to market.

6.4 Using Competitive Intelligence to Sharpen the Attack

Modern patent challenges are not conducted in the dark; they are data-driven campaigns. The effective use of competitive intelligence is critical for identifying targets and formulating a winning strategy. This is where specialized patent intelligence platforms play an indispensable role.

A service like DrugPatentWatch provides challengers with the essential tools to execute a sophisticated offensive campaign.37 Such platforms offer a comprehensive, integrated database of pharmaceutical patents, litigation history, regulatory exclusivities, and clinical trial data.36 A challenger can use these tools to:

- Map the entire patent portfolio: Identify every patent associated with a target drug, including late-listed patents that might be weaker or filed to extend exclusivity.3

- Analyze prosecution histories: Scrutinize the “file wrapper” of each patent to find arguments or amendments made by the patent owner during prosecution that could be used against them in an IPR. For example, contradictory statements made to secure different patents can be powerful evidence, as seen in the Humira case.17

- Monitor competitor activity: Track new patent filings, litigation outcomes, and PTAB proceedings across the industry to identify trends and successful challenge strategies.20

- Identify the most promising targets: By combining all of this data, a challenger can prioritize which patents in a thicket are the most vulnerable to an IPR challenge, focusing its resources where they are most likely to succeed.3

Beyond its function as a legal venue, the PTAB also serves as a powerful mechanism for driving information asymmetry in a patent dispute. The IPR process compels the patent owner to lay out their defensive strategy in detail, first in the POPR and then in the full Patent Owner Response, complete with expert declarations.8 This provides the challenger with an early, on-the-record preview of the patent owner’s arguments, evidence, and expert witnesses. A sophisticated challenger can use this compelled disclosure as a form of accelerated discovery, probing for weaknesses, locking the patent owner into specific positions, and using the information to gain a significant strategic advantage in the slower, more extensive discovery process of the parallel district court litigation or in settlement negotiations.

Section 7: Lessons from the Battlefield—High-Profile Case Studies

The strategic principles of PTAB warfare are best understood through the lens of real-world conflicts. Several high-profile challenges involving blockbuster drugs have provided invaluable lessons for both innovators and challengers, illustrating the PTAB’s power, its limitations, and its profound impact on the pharmaceutical industry.

7.1 The Thicket and the Ax: AbbVie’s Humira and the Limits of IPR

Humira (adalimumab) stands as the best-selling drug in history and the quintessential example of the patent thicket strategy in action.17 To protect its multi-billion dollar franchise long after its original compound patent expired in 2016, AbbVie constructed an astonishingly dense thicket of over 240 patents, the vast majority of which were filed after Humira was already on the market.17 This formidable barrier was designed to make a biosimilar challenge a war of a thousand cuts.

Biosimilar developers, notably Coherus Biosciences and Amgen, turned to the PTAB’s IPR process as their primary weapon to chop away at this thicket. They used IPRs as a cost-effective and precise tool to target and invalidate individual secondary patents one by one.17 In one significant victory, the PTAB invalidated all claims of an AbbVie patent covering a specific dosing regimen for Humira, finding it obvious in light of prior art.17

Key Learnings: The Humira saga demonstrates that while IPRs are the ideal weapon for attacking a patent thicket, they have their limits. Challengers can win individual battles at the PTAB, but the sheer cost and complexity of challenging hundreds of patents can make winning the overall war impossible. Ultimately, the overwhelming size of AbbVie’s portfolio achieved its strategic objective. Nearly every major biosimilar competitor, despite some IPR successes, was forced to the negotiating table and agreed to a settlement that delayed their U.S. market entry until 2023.17 The lesson is that a massive, brute-force thicket can succeed as a business strategy even in the face of some legal losses.

7.2 A Matter of Obviousness: The Invalidation of Teva’s Copaxone Patents

Teva’s blockbuster multiple sclerosis drug, Copaxone (glatiramer acetate), provides a classic case study of a successful obviousness challenge against a lifecycle management patent.17 After its original patent on a 20mg daily injection was set to expire, Teva developed and patented a new 40mg version administered only three times per week. Teva argued this was a non-obvious invention that offered significant patient benefits.

Generic challengers, including Sandoz and Mylan, disagreed and challenged the new patents in court and at the PTAB. They argued that exploring less frequent dosing regimens to improve patient adherence and reduce side effects was a well-known and predictable path for clinicians. The courts and the PTAB ultimately agreed, invalidating the patents on the grounds of obviousness.17 The new dosing regimen was deemed to fall under the “obvious to try” standard, where there are a limited number of predictable solutions to a known problem, and a skilled artisan would have had a reasonable expectation of success in pursuing one of them.17

Key Learnings: The Copaxone case underscores the vulnerability of incremental innovations at the PTAB and in the courts. Commercial success, while a “secondary consideration” in the obviousness analysis, cannot save a patent that is based on a predictable advancement.17 It also highlights the importance of a combined legal and commercial strategy. While Teva lost the patent battle, it successfully executed a “product hop” by converting a majority of patients to the new 40mg version before generics for the 20mg version could launch, thereby mitigating a significant portion of the financial damage from the legal defeat.17

7.3 A Second Bite at the Apple: The Novartis v. Noven (Exelon) Case

Perhaps no case more starkly illustrates the unique threat posed by the PTAB than the challenge to patents covering the Exelon dementia patch. The validity of these patents, which covered a pharmaceutical composition of rivastigmine, had been challenged in the U.S. District Court for the District of Delaware. After a full trial, the district court found the patents were not invalid for obviousness. That decision was then affirmed on appeal by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit, the nation’s top patent court.18

Despite this resounding victory in the federal court system, a challenger filed an IPR petition at the PTAB against the very same patents, using much of the same prior art. In a stunning decision, the PTAB reached the opposite conclusion, finding the patent claims invalid for obviousness. The Federal Circuit, in a subsequent appeal, affirmed the PTAB’s decision.18 The court explained that this seemingly contradictory outcome was legally permissible for one simple reason: the burden of proof is different. In district court, the challenger had to prove invalidity by “clear and convincing evidence.” At the PTAB, the challenger only had to prove unpatentability by a “preponderance of the evidence.” The PTAB was not bound by the prior court decisions and was free to reach a different conclusion under the lower standard.40

Key Learnings: The Exelon case is a chilling lesson for patent owners. It demonstrates that a victory in district court, even one affirmed on appeal, provides no sanctuary from a PTAB challenge. The PTAB offers challengers a “second bite at the apple” in a more favorable forum with a lower burden of proof. This lack of deference to prior judicial rulings means that a patent’s validity can be re-litigated and potentially lost, creating a state of perpetual uncertainty for patent holders.

Viewed together, these case studies reveal that PTAB risk is not uniform across all types of pharmaceutical patents. The outcomes are heavily influenced by the nature of the underlying innovation. Truly novel compositions of matter remain highly resilient. Incremental improvements, such as new formulations and dosing regimens that form the backbone of many lifecycle management strategies, are acutely vulnerable to obviousness challenges. This forces pharmaceutical companies to confront a difficult strategic question: is the substantial investment in incremental R&D worth it if the resulting patents are so easily invalidated by the PTAB?

Section 8: The Boardroom Impact—Integrating PTAB Risk into Business Strategy

The creation of the PTAB has sent shockwaves far beyond the courtroom and the offices of patent attorneys. Its influence now permeates the highest levels of corporate decision-making in the pharmaceutical industry, fundamentally altering how companies manage R&D, evaluate acquisition targets, and attract investment. PTAB risk has evolved into a fully-fledged financial and strategic diligence category, standing alongside clinical trial risk and regulatory risk as a critical variable in the calculus of value creation.

8.1 R&D and Portfolio Management in the Shadow of the PTAB

The heightened risk that the PTAB poses to secondary, lifecycle management patents has direct implications for R&D and portfolio management strategy. The traditional model of extending a drug’s franchise through a series of incremental improvements is now under siege.23 Company leaders must now engage in a more sophisticated risk-benefit analysis. The potential for a few extra years of market exclusivity gained from a new formulation patent must be weighed against the high probability that this patent will be challenged and potentially invalidated in an IPR.10

This new reality demands a more dynamic and rigorous approach to patent portfolio management.23 It is no longer sufficient to simply accumulate patents. Companies must continuously assess their portfolios from the perspective of a potential PTAB challenger, identifying the weakest links and making strategic decisions about which assets are worth defending and which should be allowed to lapse to conserve resources.36 This involves:

- Regular PTAB Vulnerability Audits: Proactively “war-gaming” potential IPR challenges against key patents to understand their strengths and weaknesses.

- Strategic Pruning: Divesting or abandoning low-value or high-risk patents that are unlikely to survive a PTAB challenge and are a drain on maintenance fees.23

- Aligning R&D with Patent Strength: Prioritizing R&D projects that are likely to lead to more resilient, less obvious patents, rather than purely incremental improvements that are prime targets for IPRs.27

8.2 M&A Due Diligence: Quantifying PTAB Risk in Valuations

In the world of pharmaceutical mergers and acquisitions, intellectual property is often the single most valuable asset being acquired.42 Consequently, IP due diligence is one of the most critical phases of any transaction.44 In the post-AIA era, this due diligence must include a rigorous and quantitative assessment of the target’s PTAB risk.25

An acquiring company can no longer take a target’s patent portfolio at face value. The valuation of the deal depends directly on the strength, scope, and enforceability of the patents protecting the target’s revenue-generating products.44 A portfolio that relies heavily on secondary patents, particularly method-of-use or formulation patents that have not yet been tested in litigation, represents a significant and quantifiable liability.44 Acquirers must now routinely:

- Conduct Pre-Acquisition IPR Searches: Determine if any of the target’s key patents are already facing, or have previously faced, PTAB challenges.

- Assess the “Thicket” Quality: Analyze the diversity and strength of the target’s patent thicket. Is it a robust web of interlocking patents or a collection of weak, easily invalidated claims?

- Model PTAB Invalidation Scenarios: Build financial models that account for the potential loss of market exclusivity on an accelerated timeline due to a successful PTAB challenge. A miscalculation of a key patent’s effective life can have a catastrophic impact on a deal’s economic rationale.44

The potential for a PTAB challenge can directly influence deal terms, including the purchase price, the use of milestone payments, and the allocation of liability for future litigation.

8.3 Investor Perspectives: How PTAB Uncertainty Affects Venture Capital and Market Valuations

The uncertainty created by the PTAB also affects the flow of capital into the industry, particularly at the early stages. For a venture capital-backed biotech startup, its entire valuation may rest on a small number of foundational patents.47 Venture capital investors, who are tasked with evaluating high-risk, high-reward opportunities, must now add PTAB vulnerability to their long list of diligence items.48

Investors are increasingly sophisticated in their evaluation of IP strength. They look at metrics like the remaining patent life and conduct freedom-to-operate analyses to ensure a startup can commercialize its product without infringing other patents.48 The knowledge that a competitor could launch a relatively inexpensive and rapid PTAB challenge against a startup’s core patents can have a chilling effect on investment, or at the very least, lead to lower valuations and more investor-friendly terms.50 This forces early-stage companies to invest more heavily in creating an exceptionally robust and well-prosecuted initial patent filing that is designed from day one to withstand future scrutiny.

The impact is also felt in the public markets. As the hedge fund strategy of shorting a stock and then filing an IPR has shown, the mere existence of a PTAB challenge can create significant volatility in a company’s stock price.11 This means that public market investors and analysts must now have a view on a company’s PTAB exposure. PTAB risk is no longer a niche legal issue; it is a tangible, financial variable that is actively being priced into the market, requiring a new level of collaboration and understanding between legal experts and financial teams.

Conclusion: From Risk Mitigation to Strategic Advantage

The Patent Trial and Appeal Board has fundamentally and irrevocably altered the landscape of pharmaceutical intellectual property. Born from a desire to improve patent quality and streamline litigation, it has evolved into a powerful, complex, and often paradoxical institution. It serves as both a necessary check on the patent system, effectively weeding out weaker, incremental patents, and a source of profound uncertainty for the innovators whose business models depend on the stability and predictability of their patent rights. The PTAB is at once innovation’s shield and its Achilles’ heel.

The journey through its creation, its economic drivers, its statistical outcomes, and its evolving legal doctrines reveals a clear and urgent message for leaders in the pharmaceutical industry: in the age of the PTAB, a passive, reactive approach to patent law is a guarantee of diminished value and strategic failure. The threats are too numerous and the stakes too high. The companies that will thrive in this new environment are those that internalize this reality and integrate a deep, proactive understanding of the PTAB into every facet of their business.

The future of the PTAB itself remains dynamic. Legislative reforms, such as the proposed PREVAIL Act, continue to be debated in Congress. Such legislation aims to rebalance the system by harmonizing PTAB standards with those of the district courts, for instance, by raising the burden of proof to “clear and convincing evidence” and strengthening estoppel provisions.9 Simultaneously, the USPTO’s own leadership will continue to use its discretionary authority to modulate the PTAB’s impact through administrative doctrines, creating a constantly shifting set of procedural rules that demand vigilance.

Ultimately, the challenge of the PTAB is also an opportunity. The intense scrutiny it applies forces companies to be more rigorous in their R&D and more disciplined in their patent prosecution. It demands a higher standard of innovation. The companies that embrace this challenge—that build resilient patent fortresses, that conduct ruthless due diligence, that align their legal and business strategies, and that view patent management not as a cost center but as a core driver of competitive advantage—will not only survive the PTAB gauntlet but will emerge stronger, more efficient, and better positioned to lead the next generation of medical innovation.

Key Takeaways

- The Threat is Real, but Specific: The PTAB poses a significant threat, with bio/pharma patents facing some of the highest institution rates of any technology sector. However, the primary risk is to weaker secondary patents (e.g., formulations, methods of use), not the core compound patents that form the foundation of a drug’s value.

- Timing is Everything: PTAB strategy is now dominated by procedural timing and maneuvering. Challengers are incentivized to file petitions early to avoid new “settled expectations” denials, while patent owners can use the progress of parallel district court litigation to trigger a Fintiv discretionary denial.

- Defense is a War of Attrition: The most effective defensive strategy against the PTAB is often the construction of a large “patent thicket.” While any single secondary patent may be vulnerable, a dense portfolio of overlapping patents can make a comprehensive challenge economically unviable for competitors, frequently forcing them into settlements that preserve a portion of the brand’s market exclusivity.

- PTAB Risk is Now a Financial Metric: PTAB risk has moved from the legal department to the boardroom and the trading floor. It is a core component of business and financial diligence. M&A valuations, deal terms, and venture capital investments are now directly impacted by a patent portfolio’s perceived vulnerability to IPR challenges.

- Proactivity is Non-Negotiable: A passive approach to patent management is no longer viable. Survival in the PTAB era requires proactive and continuous portfolio management, including using competitive intelligence tools like DrugPatentWatch to monitor threats, stress-testing key assets for vulnerabilities, and strengthening patents during prosecution to anticipate future challenges.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. What is the single biggest mistake a drug company can make regarding the PTAB?

The single biggest mistake is being reactive instead of proactive. Many companies treat PTAB risk as a purely legal problem that begins only when a petition is filed. This is a critical error. By the time a petition arrives, it is often too late to fix underlying weaknesses in a patent. The most successful companies anticipate challenges years in advance. They fail to stress-test their patent portfolios for vulnerabilities, identify the most likely grounds for attack, and develop a comprehensive defense strategy long before a challenger ever appears. Proactive defense involves strengthening patents during prosecution, strategically building a patent thicket, and continuously monitoring the competitive landscape for potential threats.

2. Is it still worth filing for secondary patents (e.g., new formulations) if they are so vulnerable at the PTAB?

Yes, absolutely, but it must be done as part of a broader, more sophisticated strategy. While it is true that any single secondary patent is more vulnerable to an obviousness challenge at the PTAB than a core compound patent, their value lies in their collective strength. Filing for multiple, layered secondary patents on formulations, methods of use, and manufacturing processes creates a “patent thicket.” This strategy works not by making any one patent invincible, but by making the overall cost and complexity of challenging the entire portfolio prohibitively expensive for a competitor. Each patent is another hurdle, another potential lawsuit, and another IPR that must be filed and won. This cumulative effect is a powerful deterrent and frequently forces challengers into settlements that allow for an earlier generic entry but still preserve significant value for the innovator.

3. If my patent survives a PTAB challenge, am I safe from future challenges?

No, you are not entirely safe. If your patent survives a final written decision, the legal doctrine of estoppel prevents the specific petitioner who brought the challenge from re-litigating the same issues in district court or filing another PTAB petition on grounds they raised or reasonably could have raised.15 This provides significant protection against that one party. However, estoppel does not apply to

other potential challengers. A different generic or biosimilar company is completely free to file its own, new PTAB petition against the same patent, potentially using different prior art or arguments. There is no true “quiet title” for a patent owner in the current system, meaning a valuable patent can face multiple, serial challenges from different parties throughout its life.

4. How has the recent focus on “discretionary denials” like Fintiv changed the game?

The rise of discretionary denials has shifted the strategic focus from being solely about the patent’s merits to being heavily about procedural timing and the interplay between the PTAB and district court litigation. Under the Fintiv doctrine, the PTAB can refuse to hear a case if a parallel district court case is too far advanced.31 This has created a “race to trial” where patent owners try to speed up their court case to create a

Fintiv off-ramp, while challengers must file their PTAB petitions as early as possible to avoid it. More recent doctrines like “settled expectations” add another layer, penalizing challengers for waiting too long to file a petition against a long-standing patent.33 The result is that strategic procedural maneuvering has become just as important as the substantive arguments about a patent’s validity.

5. As a business leader, what is the most important PTAB-related question I should ask my Chief IP Counsel?

The most important question a business leader can ask is: “Have we conducted a full vulnerability assessment of our key products’ patent portfolios from the perspective of a potential PTAB challenger, and what is our plan to mitigate the top three risks we’ve identified?” This question cuts to the heart of a proactive strategy. It moves the conversation beyond simply counting the number of patents and forces the legal team to think like the adversary. A strong answer should include an analysis of the key secondary patents, an evaluation of the best prior art that could be used against them, a frank assessment of their likelihood of surviving an IPR, and a concrete, actionable plan to either strengthen those patents, build a more robust thicket around them, or prepare a defense for the inevitable challenge.

Works cited

- Pharmaceutical Patent Regulation in the United States – The Actuary …, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.theactuarymagazine.org/pharmaceutical-patent-regulation-in-the-united-states/

- How Drug Life-Cycle Management Patent Strategies May Impact Formulary Management, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.ajmc.com/view/a636-article

- Patent Defense Isn’t a Legal Problem. It’s a Strategy Problem. Patent …, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/patent-defense-isnt-a-legal-problem-its-a-strategy-problem-patent-defense-tactics-that-every-pharma-company-needs/

- The Pharmaceutical Patent Playbook: Forging Competitive …, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/developing-a-comprehensive-drug-patent-strategy/

- About PTAB | USPTO, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.uspto.gov/patents/ptab/about-ptab

- Patent Trial and Appeal Board – Wikipedia, accessed August 16, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Patent_Trial_and_Appeal_Board

- Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) | Practical Law – Thomson Reuters, accessed August 16, 2025, https://uk.practicallaw.thomsonreuters.com/0-508-3165?transitionType=Default&contextData=(sc.Default)

- Understanding the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) – A …, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/understanding-the-patent-trial-and-appeal-board-ptab-a-comprehensive-overview/

- Bipartisan Push for Patent Law Reform | Crowell & Moring LLP, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.crowell.com/en/insights/client-alerts/bipartisan-push-for-patent-law-reform

- POST-GRANT ADJUDICATION OF DRUG PATENTS: AGENCY AND/OR COURT? – Berkeley Technology Law Journal, accessed August 16, 2025, https://btlj.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/0003-37-1-Rai.pdf

- What They Are Saying: Close Patent Loopholes That Threaten …, accessed August 16, 2025, https://phrma.org/blog/what-they-are-saying-close-patent-loopholes-that-threaten-innovation-for-patients

- Patent Trial and Appeal Board – USPTO, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.uspto.gov/about-us/organizational-offices/patent-trial-and-appeal-board

- PTAB Post-Grant Review: IPR, PGR, and CBM | Finnegan | Leading IP+ Law Firm, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.finnegan.com/en/work/practices/patent-invalidation-proceedings/ptab-post-grant-review-ipr-pgr-and-cbm.html

- PTAB Trial Statistics FY22 End of Year Outcome Roundup … – USPTO, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.uspto.gov/sites/default/files/documents/ptab__aia_fy2022_roundup.pdf

- Major Differences between IPR, PGR, and CBM – USPTO, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.uspto.gov/sites/default/files/ip/boards/bpai/aia_trial_comparison_chart.pptx

- Post-Grant Proceedings | Perkins Coie, accessed August 16, 2025, https://perkinscoie.com/services/post-grant-proceedings

- The Challenger’s Gambit: A Strategic Guide to Identifying and …, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/identifying-and-invalidating-weak-drug-patents-in-the-united-states/

- Pharma Lessons from the PTAB: Litigation and Prosecution, accessed August 16, 2025, https://ipo.org/index.php/pharma-lessons-ptab-litigation-prosecution/

- Key Strategies for Successfully Challenging a Drug Patent …, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/key-strategies-for-successfully-challenging-a-drug-patent/

- Biosimilar Patent Dance: Leveraging PTAB Challenges for Strategic …, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/biosimilar-patent-dance-leveraging-ptab-challenges-for-strategic-advantage/

- Perfecting Expert Testimony at PTAB – McGuireWoods, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.mcguirewoods.com/client-resources/alerts/2025/3/perfecting-expert-testimony-at-ptab/

- Pharmaceutical Patent Challenges: Company Strategies and Litigation Outcomes, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.1162/AJHE_a_00066

- The Patent Portfolio as a Strategic Asset: A Comprehensive Guide to …, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/leveraging-a-drug-patent-portfolio-for-success/

- Big Pharma Versus Inter Partes Review: Why the Pharmaceutical Industry Should Seek Logical Hatch-Waxman Reform over Inter – UIC Law Open Access Repository, accessed August 16, 2025, https://repository.law.uic.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2724&context=lawreview

- The Role of Patents and Regulatory Exclusivities in Drug Pricing …, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/R46679

- Exploring Biosimilars as a Drug Patent Strategy: Navigating the Complexities of Biologic Innovation and Market Access – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/exploring-biosimilars-as-a-drug-patent-strategy-navigating-the-complexities-of-biologic-innovation-and-market-access/

- The Impact of Inter Partes Review on Biopharmaceutical Patents – PatentPC, accessed August 16, 2025, https://patentpc.com/blog/inter-partes-review-on-biopharmaceutical-patents

- Trial Statistics Trends at the PTAB: 2024 Edition, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.ptablaw.com/2025/01/06/trial-statistics-trends-at-the-ptab-2024-edition/

- The PTAB’s 70% All-Claims Invalidation Rate Continues to Be a …, accessed August 16, 2025, https://ipwatchdog.com/2025/01/12/ptab-70-claims-invalidation-rate-continues-source-concern/id=184956/

- Drug Patent Challenges At PTAB By The Numbers – Mayer Brown, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.mayerbrown.com/-/media/files/news/2018/06/drug-patent-challenges-at-ptab-by-the-numbers/files/drug-patent-challenges-at-ptab-by-the-numbers/fileattachment/drug-patent-challenges-at-ptab-by-the-numbers.pdf

- New Guidance Regarding Fintiv Discretionary Denial at the PTAB …, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.hklaw.com/en/insights/publications/2025/03/new-guidance-regarding-fintiv-discretionary-denial-at-the-ptab

- The Fintiv Pendulum Swings Again: More Discretionary Denials Coming Soon | Patently-O, accessed August 16, 2025, https://patentlyo.com/patent/2025/03/pendulum-discretionary-denials.html

- USPTO Acting Director Denies IPR Institution Based on “Settled …, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.jonesday.com/en/insights/2025/06/uspto-director-denies-ipr-institution-based-on-settled-expectations

- Patent protection strategies – PMC, accessed August 16, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3146086/

- Discretionary Denial under § 325(d): Strategic Implications of the PTAB’s Advanced Bionic Framework | Sterne Kessler, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.sternekessler.com/news-insights/insights/discretionary-denial-under-ss-325d-strategic-implications-ptabs-advanced/

- Best Practices for Drug Patent Portfolio Management …, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/best-practices-for-drug-patent-portfolio-management/

- Drug Patent Watch Launches Service Offering Real-Time Patent …, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.geneonline.com/drug-patent-watch-launches-service-offering-real-time-patent-monitoring-for-pharmaceutical-companies/

- DrugPatentWatch Report: Pharmaceutical Companies Use Patent …, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.geneonline.com/drugpatentwatch-report-pharmaceutical-companies-use-patent-strategies-to-protect-revenue-and-defend-against-generic-competition/

- Policy Brief: How the Supreme Court Patent Case Could Raise Drug Prices – I-MAK, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.i-mak.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Policy-Brief_SCOTUS-Patent-Case_-FINAL-TO-PDF.pdf

- The PTAB Can Offer A Second Chance At Obviousness—Even After The Federal Circuit Affirms The Non-Obviousness of the Patent Claims – K&L Gates, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.klgates.com/The-PTAB-Can-Offer-A-Second-Chance-At-ObviousnessEven-After-The-Federal-Circuit-Affirms-The-Non-Obviousness-of-the-Patent-Claims-06-06-2017

- Pharmaceutical Portfolio Management: A Complete Primer – Planview, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.planview.com/resources/articles/pharmaceutical-portfolio-management-a-complete-primer/

- The Role of Patents in Biopharmaceutical Mergers and Acquisitions | PatentPC, accessed August 16, 2025, https://patentpc.com/blog/patents-in-biopharmaceutical-mergers-and-acquisitions

- IP in Pharma and Biotech M&A: What Makes It So Complex | PatentPC, accessed August 16, 2025, https://patentpc.com/blog/ip-in-pharma-and-biotech-ma-what-makes-it-so-complex

- A Comprehensive Guide to Pharmaceutical Patent Due Diligence in …, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/ma-patent-due-diligence-comprehensive-guide/

- IP Due Diligence in M&A | Protecting Your Investments, accessed August 16, 2025, https://ttconsultants.com/due-diligence-in-mergers-acquisitions-ensuring-smart-ip-investments/

- M&A in Pharma: Balancing Growth and Risk, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.pharmaceuticalcommerce.com/view/m-a-in-pharma-balancing-growth-and-risk

- Patent Financing for Biotech Companies: A Path to Market Leadership – PatentPC, accessed August 16, 2025, https://patentpc.com/blog/patent-financing-biotech-companies-market-leadership

- Biotech Venture Capital: Investment Dynamics & Strategies, accessed August 16, 2025, https://growthequityinterviewguide.com/venture-capital/sector-focused-venture-capital/biotech-venture-capital

- What is the Role of Venture Capital in Drug Discovery and …, accessed August 16, 2025, https://globalforum.diaglobal.org/issue/may-2023/what-is-the-role-of-venture-capital-in-drug-discovery-and-development/

- The PTAB Case – DebateUS, accessed August 16, 2025, https://debateus.org/the-ptab-case/

- Will New PTAB Rules Impact IPRs Filed By Kyle Bass Hedge Fund? – Foley & Lardner LLP, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.foley.com/insights/publications/2015/08/will-new-ptab-rules-impact-iprs-filed-by-kyle-bass/