Introduction: The Collision of Two Worlds

In the world of pharmaceuticals, the patent is more than a legal document; it is the economic bedrock upon which the entire industry is built. The promise of a limited period of market exclusivity is the fundamental incentive that justifies the staggering investment—anywhere from $300 million to over $4.5 billion—and the decade-plus of painstaking research required to bring a single new medicine to patients . For decades, the rules of this high-stakes game were governed by a delicate, congressionally-mandated equilibrium known as the Hatch-Waxman Act, a framework designed to balance the need for innovator profits with the societal demand for affordable generic drugs .

Then, in 2011, everything changed. With the passage of the Leahy-Smith America Invents Act (AIA), Congress introduced a powerful new player onto the field: the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB). This administrative tribunal, housed within the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) itself, was created to be a faster, cheaper, and more efficient forum for challenging the validity of issued patents . It was a sweeping reform, but it was not designed with the unique ecosystem of pharmaceutical patents in mind. The PTAB was Congress’s answer to the “patent troll” problem plaguing the technology sector—a one-size-fits-all solution to weed out “poor-quality patents” and curb abusive litigation .

The result has been nothing short of a tectonic shift in the strategic landscape. The superimposition of the PTAB’s broad, industry-agnostic review process onto the highly specialized, carefully balanced world of Hatch-Waxman created a collision of two distinct legal philosophies. For innovator and generic companies alike, it established a parallel universe of patent challenges, a second front in the war for market share. This new reality has fundamentally altered the strategic calculus for every stakeholder. Innovators now face the prospect of defending their most valuable assets in two venues simultaneously, under different rules and different standards of proof, decrying the PTAB as an unfair “second bite at the apple” for challengers . Generic and biosimilar manufacturers, in turn, have embraced the PTAB as a powerful and essential tool—a “second look” to eliminate weak patents that they argue are used to improperly delay competition and keep drug prices high .

Understanding this foundational mismatch—this accidental collision of two worlds—is the first step toward mastering the modern game. The strategies that lead to success are no longer confined to the courtroom; they are forged in the intricate dance between the district court and the PTAB. This report is your guide to that dance. We will dissect the timing, risks, and strategies that define this new era, transforming complex legal procedure into a tangible competitive advantage. Whether you are defending a blockbuster drug or plotting its generic successor, the path to market now runs directly through this dual-track arena. Welcome to the new front line.

The 20-Year Illusion: Understanding Effective Patent Life and the Race Against Time

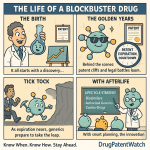

At first glance, the patent system offers a generous reward for innovation: a 20-year term of exclusivity, starting from the date a patent application is filed . This 20-year standard, enshrined in the global TRIPS agreement, appears to provide a long runway for a pharmaceutical company to recoup its investment and turn a profit . However, for anyone in the pharmaceutical industry, this figure is a well-known illusion.

The reality is that the “effective patent life”—the actual period a drug is on the market with monopoly protection—is drastically shorter . The moment the patent application is filed, often as soon as a promising molecule is identified, the 20-year clock starts ticking. But the drug is nowhere near the market. What follows is a grueling marathon of development and regulatory review—a journey that consumes, on average, 10 to 15 years of that precious patent term . This period is filled with extensive preclinical research to establish basic safety, followed by three arduous phases of clinical trials to prove safety and efficacy in humans, and finally, a rigorous review by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) .

The consequence of this front-loaded timeline is that by the time a drug finally launches, its statutory 20-year patent term may have already been half-spent. The average effective market exclusivity that an innovator company actually enjoys is closer to 7 to 10 years . This compressed timeframe creates immense economic pressure. It’s a frantic race against time to generate enough revenue to cover not only the billions spent on that successful drug but also the costs of the countless other candidates that failed along the way.

This temporal pressure is the central economic force driving the strategic behavior of both innovator and generic companies. For innovators, it fuels an aggressive approach to pharmaceutical lifecycle management. They cannot rely solely on the core patent covering the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API). To extend their brief window of profitability, they build defensive fortifications—what is often called a “patent thicket”—by filing a web of secondary patents . These patents cover every conceivable aspect of the drug beyond the molecule itself: new formulations (like an extended-release version), novel methods of use (treating a new disease), specific dosage regimens, or improved manufacturing processes . Each of these secondary patents has its own 20-year term, creating a layered defense designed to delay the inevitable “patent cliff,” that precipitous drop in revenue when generic competition finally arrives.

For generic companies, this same time pressure creates a clear strategic imperative. They see these secondary patents not as insurmountable barriers, but as targets of opportunity. While the core API patent is often scientifically robust and difficult to challenge, the secondary patents that make up the “thicket” are frequently viewed as weaker, more incremental innovations . This is where the PTAB enters the picture. With its lower burden of proof and technically expert judges, the PTAB provides the perfect forum for a generic challenger to systematically dismantle this patent thicket, clear a path to market, and accelerate the end of the innovator’s monopoly . The battle at the PTAB, therefore, is rarely about the foundational discovery of a new medicine. It is a war fought on the periphery, a high-stakes conflict over the secondary patents that determine by just how many years—and how many billions of dollars—an innovator can extend its market exclusivity.

The PTAB: Congress’s Answer to Patent Quality or a “Patent Death Squad”?

Born from the America Invents Act of 2011, the Patent Trial and Appeal Board was established as a new administrative body within the USPTO, replacing the old Board of Patent Appeals and Interferences . Its creation was heralded by proponents as a landmark reform designed to improve the quality of U.S. patents and provide a more efficient, cost-effective alternative to the slow and expensive process of litigating patent validity in federal district court .

The PTAB is staffed by a corps of over 100 Administrative Patent Judges (APJs), who are not generalist jurists but are required to have scientific or engineering backgrounds and significant experience in patent law . A three-judge panel of APJs presides over each case, bringing a level of technical expertise to the proceedings that is rarely found in a district court . This structure was intended to allow for a more sophisticated and accurate assessment of a patent’s technical merits when weighed against the prior art.

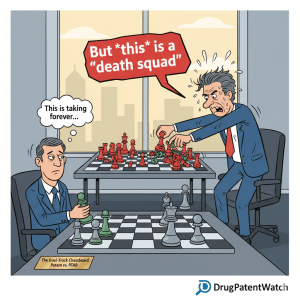

From its inception, however, the PTAB has been a lightning rod for controversy. Critics, particularly from patent-intensive industries like pharmaceuticals, quickly voiced concerns that the new tribunal was fundamentally biased against patent holders. The late Chief Judge of the Federal Circuit, Randall Rader, famously labeled the PTAB a “patent death squad,” a moniker that has stuck in the minds of many innovators . This critique stems from several key features of PTAB proceedings, most notably the lower standard of proof for invalidation and, historically, a broader standard for claim construction, which combine to make patents more vulnerable than they are in court . The statistics often cited to support this view are stark: across all technologies, once a patent challenge is instituted for trial at the PTAB, the invalidation rates for challenged claims have been alarmingly high, often exceeding 70% or 80% . This has created a perception that the PTAB is a forum where patents go to die, creating profound uncertainty for those who rely on patent protection to justify massive R&D investments .

The constitutionality of this powerful administrative body was inevitably challenged, leading to a series of landmark Supreme Court cases. In Oil States Energy Services v. Greene’s Energy Group (2018), the Court upheld the fundamental legitimacy of the PTAB, reasoning that the grant of a patent is a “public right” or “public franchise,” not a private property right that can only be revoked by an Article III court. Therefore, Congress was within its constitutional authority to create an administrative process to reconsider and cancel that grant . A few years later, in United States v. Arthrex, Inc. (2021), the Court addressed the structure of the PTAB itself. It found that the way APJs were appointed violated the Appointments Clause of the Constitution because their decisions were not subject to review by a presidentially appointed officer. To remedy this, the Court severed the problematic statutory provision, granting the Director of the USPTO the authority to review and overturn PTAB decisions, adding a new layer of executive oversight to the process .

While the “patent death squad” narrative is powerful, a deeper dive into the data reveals a more nuanced reality, especially within the pharmaceutical sector. The PTAB is not a monolithic destroyer of all drug patents. Its impact varies dramatically depending on the type of drug and the nature of the patent under review. For small-molecule drugs listed in the FDA’s Orange Book, the outcomes for patents that reach a final written decision are surprisingly balanced. According to a 2021 USPTO study, 50% of these patents had all challenged claims upheld, while 45% had all claims found unpatentable . This is hardly the work of a “death squad.”

The picture is entirely different for biologics. For biologic patents that reach a final written decision, a staggering 70% have all challenged claims invalidated, while only 21% survive the process intact . This dramatic divergence shows that a one-size-fits-all view of the PTAB is strategically flawed. The risk calculus for a company challenging a formulation patent on a blockbuster pill is fundamentally different from that of a company challenging a manufacturing process patent for a complex monoclonal antibody. The “death squad” may be very real for some, but it is a far more manageable risk for others. This data-driven distinction is critical for any company formulating a PTAB strategy.

Dueling Venues: A Strategic Comparison of PTAB and District Court

For any company embroiled in a pharmaceutical patent dispute, the central strategic question is no longer simply how to litigate, but where. The existence of the PTAB has created a dual-track system, forcing both innovators and challengers to weigh the distinct advantages and disadvantages of two very different forums: the administrative tribunal of the PTAB and the traditional setting of a U.S. district court. Making the right choice—or effectively managing a battle on both fronts—requires a deep understanding of the procedural chasms that separate these two worlds.

The Burden of Proof: Preponderance of Evidence vs. Clear and Convincing

The single most significant difference between the two venues, and the one that most heavily tilts the scales in favor of challengers at the PTAB, is the standard of proof required to invalidate a patent.

In a district court, an issued patent enjoys a powerful statutory presumption of validity . The USPTO has already examined the invention and deemed it worthy of a patent, and the court gives deference to that expert agency’s decision. To overcome this presumption, a challenger must prove that the patent is invalid by “clear and convincing evidence” . This is a high legal bar, demanding a firm belief or conviction in the truth of the facts asserted. It requires more than just showing that invalidity is more likely than not.

The PTAB operates under a completely different framework. Before the PTAB, there is no presumption of validity . The proceeding is seen as a “second look” by the same expert agency that granted the patent in the first place . Consequently, the challenger’s burden is much lower: they need only prove unpatentability by a “preponderance of the evidence” . This standard simply means showing that it is more likely than not (i.e., greater than a 50% chance) that the patent claims are invalid.

This procedural distinction creates a powerful strategic arbitrage opportunity for challengers. It allows them to take an invalidity argument that might be strong but not quite strong enough to meet the “clear and convincing” standard and test-drive it in a more favorable forum. A successful outcome at the PTAB can be a devastating blow to the patent owner. Even though a PTAB decision is not binding on the district court until all appeals are exhausted, a finding of unpatentability creates immense pressure to settle the litigation on unfavorable terms. The patent owner, now facing the very real prospect of their patent being permanently canceled, can no longer rely on the strong presumption of validity in court. The risk profile of the entire dispute is fundamentally altered. The mere filing of a credible IPR petition forces the innovator to recalibrate their litigation strategy, factoring in a significantly higher probability of losing their patent than would exist in the district court alone.

Claim Construction: The Chasm Between “Broadest Reasonable Interpretation” and the Phillips Standard

Another critical point of divergence has historically been the standard used to interpret the meaning and scope of patent claims. For years, this difference created a significant advantage for IPR petitioners.

District courts are bound by the standard set forth in the landmark case Phillips v. AWH Corp., which requires claims to be given their “ordinary and customary meaning” as understood by a person of ordinary skill in the art at the time of the invention . This is a relatively narrow standard that often favors the patent owner.

Until 2018, the PTAB employed a much different standard known as the “Broadest Reasonable Interpretation” (BRI) . Under BRI, claim terms were interpreted as broadly as their language would reasonably allow, in light of the patent’s specification . This challenger-friendly standard made it easier to argue that the broad claims covered prior art, thus rendering them invalid. This discrepancy was a major source of friction, as it could lead to the bizarre outcome of a patent claim being held valid under the Phillips standard in court but invalid under the BRI standard at the PTAB.

In 2018, in a move widely seen as a victory for patent owners, the USPTO amended its rules to adopt the Phillips standard for claim construction in IPR proceedings, aligning the PTAB with the district courts . While this harmonization was a significant procedural change, it did not eliminate the PTAB’s strategic advantage for challengers. The true value for a petitioner lies not just in the standard itself, but in the timing and expertise with which it is applied.

An IPR forces an early, expert-driven determination of claim scope. The APJs, with their technical backgrounds, provide a reading on claim construction much earlier in the process than a district court judge, who typically addresses the issue during a dedicated Markman hearing that can occur more than a year into the litigation . Filing an IPR thus serves as a form of strategic discovery on claim construction. It forces the patent owner to commit to their interpretations early and provides the challenger with an expert-level preview of how key terms are likely to be construed. This intelligence is invaluable for shaping the strategy in the parallel, higher-stakes district court battle. Even under the same Phillips standard, a panel of PhD-level scientists may arrive at a different interpretation of a complex technical term than a generalist judge, potentially opening a door for the challenger’s invalidity case.

Speed, Cost, and Expertise: Why Challengers Often Prefer the PTAB

Beyond the legal standards, the fundamental logistics of the two forums make the PTAB an attractive venue for those seeking to challenge a patent.

Speed: IPR proceedings are designed for rapid resolution. By statute, the PTAB must decide whether to institute a trial within six months of the petition filing, and it must issue a final written decision within one year of institution (though a six-month extension for good cause is possible) . This means a final decision on validity can be reached in as little as 18 months. Hatch-Waxman litigation, by contrast, is a much longer affair. The process is built around a 30-month stay on FDA approval, and it is common for cases to take that long or longer to reach a final judgment in the district court .

Cost: The speed and streamlined nature of IPRs translate into significant cost savings. While not inexpensive, a typical IPR from filing through a final decision will cost in the range of $300,000 to $600,000 in legal fees, plus USPTO fees . A full-blown Hatch-Waxman litigation, with its extensive discovery, multiple expert witnesses, and lengthy trial, routinely costs several million dollars . For a generic company looking to invalidate multiple patents in a thicket, the PTAB offers a far more economical path to clearing the way for market entry.

Expertise: As previously mentioned, the technical acumen of the APJs is a defining feature of the PTAB . For a challenger with a complex obviousness argument based on multiple, dense scientific publications, presenting that case to a panel of former scientists and engineers can be far more effective than trying to educate a lay judge and jury. This technical expertise is a powerful draw for petitioners who believe the science is on their side.

These profound differences are summarized in the table below, which provides an at-a-glance dashboard for comparing the strategic landscape of the two venues.

Table 1: Strategic Comparison of IPR and District Court Litigation for Pharmaceutical Patents

| Feature | Inter Partes Review (IPR) at the PTAB | Hatch-Waxman Litigation in District Court | Strategic Implication for Challenger | Strategic Implication for Patent Owner |

| Key Forum | Administrative Tribunal (USPTO) | Judicial (Article III Federal Court) | Offers a specialized, technical-focused alternative. | Must defend valuable assets outside the traditional court system. |

| Decision-Makers | Panel of 3 Administrative Patent Judges (APJs) with technical backgrounds | Single District Judge (generalist), potentially a jury | Favorable for complex scientific arguments. | Risks decision by specialists who may be less deferential to the patent grant. |

| Standard for Invalidation | Preponderance of the Evidence (no presumption of validity) | Clear and Convincing Evidence (patent presumed valid) | Significantly lower burden of proof, increasing chances of success. | Faces a higher risk of invalidation due to the lower evidentiary standard. |

| Claim Construction Standard | Phillips Standard (“ordinary meaning”) since 2018 | Phillips Standard (“ordinary meaning”) | Can get an early, expert-driven read on claim scope to inform court strategy. | Harmonization removes the disadvantage of the former BRI standard. |

| Timeline to Final Decision | ~18 months from petition filing | ~30 months or more | Faster resolution provides quicker certainty and potential market entry. | Compressed timeline puts immense pressure on the defense. |

| Typical All-in Cost | $300,000 – $600,000+ | $2,000,000 – $5,000,000+ | Far more cost-effective, enabling challenges against multiple patents. | Defending an IPR is an additional, significant litigation cost. |

| Scope of Discovery | Very limited; focused on cross-examination of declarants | Broad, governed by Federal Rules of Civil Procedure | Avoids costly and burdensome e-discovery and depositions. | Limited ability to probe the challenger’s case and internal documents. |

| Available Invalidity Arguments | Limited to novelty (§ 102) and obviousness (§ 103) based on patents and printed publications only | All invalidity grounds (e.g., § 101 eligibility, § 112 enablement/written description, prior public use/on-sale) | Must focus arguments on prior art documents. | Can’t be challenged on non-documentary grounds like prior sale or lack of enablement. |

| Estoppel Consequences | Petitioner is estopped from raising grounds in court that were “raised or reasonably could have been raised” in the IPR | Standard litigation preclusion rules apply. | High stakes; a loss can prevent re-litigating key arguments. However, loopholes for product art exist . | A victory provides a powerful shield (estoppel) against future attacks by the same challenger in court. |

The Generic’s Gauntlet: Interplay Between Hatch-Waxman and IPR

The Hatch-Waxman Act created a highly structured and predictable pathway for generic drug approval and patent litigation. The introduction of IPRs threw a wrench into this carefully calibrated machine, creating a new set of strategic complexities and high-stakes decisions for generic manufacturers. Navigating this dual-track system requires a sophisticated understanding of how the timelines, incentives, and statutory bars of each regime interact.

The Paragraph IV Challenge: The Traditional Path to Market

For decades, the primary weapon for a generic company seeking to enter the market before a patent’s expiration has been the Paragraph IV certification. Under the Hatch-Waxman framework, when a generic company files an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) with the FDA, it must address the innovator’s patents listed in the Orange Book . A Paragraph IV certification is a bold declaration that the generic believes the listed patent is invalid, unenforceable, or will not be infringed by its product .

This filing is considered an “artificial” act of infringement, giving the patent owner a 45-day window to file a lawsuit . If a suit is filed, it triggers an automatic 30-month stay on the FDA’s approval of the generic drug, providing a dedicated period for the courts to resolve the patent dispute .

To incentivize these challenges to potentially weak patents, Congress included a powerful reward: the first generic company to file a substantially complete ANDA with a Paragraph IV certification is granted 180 days of market exclusivity . During this six-month period, the FDA cannot approve any other generic versions of the drug. This “first-filer” exclusivity can be extraordinarily lucrative, creating a mini-monopoly for the winning generic and serving as the primary driver for early patent challenges.

The introduction of the PTAB complicates this calculus. The 180-day prize is inextricably linked to the traditional Hatch-Waxman litigation pathway. This creates a fascinating game-theoretic dilemma. A first-filer might possess a “silver bullet” prior art reference that seems perfect for a quick and decisive victory in an IPR. However, pursuing that path carries a significant risk. If they successfully invalidate the patent at the PTAB, they might inadvertently clear the path for all generic competitors to enter the market simultaneously, thereby destroying the value of their hard-won 180-day exclusivity . A second- or third-to-file generic, on the other hand, has the opposite incentive. They have no exclusivity to protect, so they are highly motivated to use the faster, cheaper IPR process to break the patent and launch their product at the same time as the first-filer. This tension means the decision to file an IPR is not merely a legal assessment of a patent’s weakness, but a complex business strategy decision that weighs the probability of success against the potential impact on a multi-million dollar market exclusivity period.

The One-Year Bar: A Critical Deadline That Shapes All Strategy

Perhaps the most consequential intersection between the two legal frameworks is the statutory time bar codified in 35 U.S.C. § 315(b). This provision states that an IPR petition may not be instituted if it is filed more than one year after the date on which the petitioner (or a real party in interest or privy) is served with a complaint alleging infringement of the patent .

This one-year clock creates a crucible of pressure for any generic defendant. It forces an early, often irreversible, strategic commitment. A company cannot afford to wait and see how the district court case unfolds; it must decide whether to pursue a dual-track strategy and commit the necessary resources within the first 12 months of being sued, or forfeit the powerful PTAB option forever.

The challenge is that this critical decision must often be made with incomplete information. In the first year of a Hatch-Waxman case, discovery is in its nascent stages. The patent owner may not have even served its final infringement contentions, meaning the generic defendant might not know with certainty which specific patent claims will ultimately be asserted against them . Despite this ambiguity, the defendant must conduct a thorough prior art search, identify the most promising invalidity grounds, retain a technical expert, and draft a highly detailed, technically dense petition that can run up to 14,000 words—all while simultaneously managing the initial phases of the district court litigation .

This statutory deadline effectively front-loads the entire cost and strategic burden of the validity challenge onto the petitioner. It demands a “dual-track sprint” from the moment the complaint is served. Companies that lack the resources, expertise, or foresight to immediately mobilize for both a district court defense and a potential PTAB offense are placed at a severe and often insurmountable disadvantage.

The Fintiv Factors: Navigating the Specter of Discretionary Denial

Even for a petitioner who meticulously meets the one-year deadline and presents a compelling case for invalidity, there is another major hurdle: the PTAB’s discretionary authority to deny institution. Under the framework established in the precedential case Apple Inc. v. Fintiv, Inc., the Board can decline to institute an IPR if a parallel district court proceeding is too far advanced, making the administrative trial an inefficient use of resources .

The PTAB weighs a series of factors, known as the Fintiv factors, to make this determination:

- Whether the district court has granted a stay or is likely to.

- The proximity of the court’s trial date to the PTAB’s statutory deadline for a final written decision.

- The level of investment in the parallel proceeding by the court and the parties.

- The degree of overlap between the issues raised in the IPR petition and the parallel litigation.

- Whether the petitioner and the district court defendant are the same party.

- Other circumstances, including the merits of the petition .

This framework has transformed the patent owner’s initial choice of litigation venue into a potent strategic weapon. By filing their Hatch-Waxman lawsuit in a so-called “rocket docket”—a federal district known for its aggressive scheduling and fast time to trial, such as the Western District of Texas or the Eastern District of Virginia—an innovator can strategically manipulate the Fintiv factors in their favor.

Consider this common scenario: an innovator sues a generic company in a district that routinely sets trial dates within 24 months. The generic company, needing time to prepare its case, files its IPR petition nine months later. By the time the PTAB is ready to make its institution decision (which can be up to six months after the petition is filed), the district court trial may be only nine or ten months away. At this point, the innovator can persuasively argue to the PTAB that instituting an IPR would be duplicative and inefficient. The court, they will argue, has already invested significant resources, and its trial will likely conclude before the PTAB can issue its final written decision .

This dynamic means the filing of the initial complaint is no longer just a procedural necessity; it is a preemptive strike against the PTAB. Challengers must now analyze the median time-to-trial statistics of various federal districts as a core component of their pre-filing risk assessment. A patent that appears highly vulnerable to an IPR challenge may be effectively shielded from that challenge if the innovator can secure the right judicial venue first. Under the current USPTO leadership, there has been a renewed emphasis on discretionary denials, including a new bifurcated process where these issues are briefed and decided before the merits, making this strategic consideration more critical than ever .

The Petitioner’s Playbook: Offensive Strategies for Challenging Drug Patents at the PTAB

For a generic or biosimilar manufacturer, the PTAB is more than just an alternative venue; it is an offensive weapon. When wielded with precision and strategic foresight, an IPR can dismantle a patent thicket, accelerate market entry, and create immense leverage in settlement negotiations. Success, however, is not guaranteed. It requires a sophisticated approach to timing, meticulous preparation, and a deep understanding of what persuades the technically-minded judges of the PTAB.

Timing the Attack: When to File an IPR for Maximum Impact

The decision of when to file an IPR petition is one of the most critical strategic choices a challenger will make. The one-year statutory bar sets the outer limit, but within that window, a spectrum of tactical options exists, each with its own risks and rewards.

Filing Early (Pre-Litigation or Immediately After Suit): Launching an IPR before a Hatch-Waxman suit is even filed, or immediately after the complaint is served, can be a powerful preemptive strike. This strategy puts the patent owner on the back foot, forcing them to defend their patent’s validity before they have had the benefit of discovery to understand the challenger’s product . The patent owner may have to take claim construction positions in their preliminary response at the PTAB without fully knowing how those positions will impact their infringement case in court . A swift filing also maximizes the chances of obtaining a stay of the district court litigation, as the judge will see that the PTAB proceeding is well underway and likely to resolve key validity issues, thus simplifying the court’s task .

Filing Later (Near the One-Year Deadline): Conversely, waiting until later in the one-year window allows the challenger to leverage the initial stages of district court discovery to their advantage. They can use interrogatories and document requests to force the patent owner to identify the specific claims they intend to assert and to articulate their infringement theories . This intelligence can be used to craft a more focused and potent IPR petition, targeting only the claims that truly matter in the litigation. This approach reduces the risk of wasting resources challenging claims that the patent owner never intended to enforce.

The most sophisticated approach, however, is often not a single, all-encompassing attack but a “staggered assault.” Imagine a blockbuster drug protected by a dozen patents—a mix of composition, formulation, and method-of-use claims. A challenger’s due diligence, perhaps aided by competitive intelligence from a platform like DrugPatentWatch, might reveal that the formulation patents are particularly vulnerable to invalidation based on prior art publications, making them ideal IPR candidates. The method-of-use patents, on the other hand, might be weaker against arguments of prior public use, which cannot be raised in an IPR .

In this scenario, the challenger could file IPRs against only the vulnerable formulation patents within the first six months of being sued. This creates a focused, high-probability attack that forces the patent owner to fight on two fronts. A win at the PTAB on these key patents can dramatically de-risk the overall litigation and provide enormous settlement leverage, even if the other patents remain in play. This surgical approach transforms the IPR from a blunt instrument into a precision tool, used to methodically remove the weakest pillars of the innovator’s patent fortress.

Crafting the “Linchpin” Petition: Best Practices for Success

The IPR petition is, without exaggeration, the single most important document in the entire proceeding. It is the “linchpin” upon which the challenger’s entire case rests . If the petition fails to persuade the PTAB that there is a “reasonable likelihood” of prevailing, the Board will deny institution, and that decision is final and non-appealable . The challenger gets one shot, and it must be a masterpiece of technical and legal persuasion.

A winning petition is far more than a simple notice pleading. It must be a self-contained, comprehensive case for invalidity, leaving no stone unturned and no argument to inference . Key best practices include:

- Address Every Claim Limitation: The petition must meticulously map each and every limitation of the challenged claims to the disclosures in the prior art references. It is a fatal error to assume the judges will fill in the gaps or rely on the general knowledge of a person skilled in the art (POSA) to supply a missing element .

- Articulate a Compelling Motivation to Combine: For obviousness challenges, which are the most common ground for IPRs, simply showing that all claim elements exist in the prior art is not enough. The petition must tell a persuasive story about why a skilled artisan would have been motivated to combine those specific references to arrive at the claimed invention, and why they would have had a reasonable expectation of success in doing so . Conclusory statements like “it would have been an obvious design choice” are routinely rejected by the Board .

- Leverage a Credible Expert: The petition must be accompanied by a detailed declaration from a qualified technical expert . This declaration should not merely parrot the attorney’s arguments. Instead, it should provide the underlying technical reasoning, context, and explanation that brings the prior art to life. The most effective declarations are rich with illustrative charts, diagrams, and analogies that help the APJs, as fellow technical experts, grasp the core of the invalidity argument .

- Deconstruct the Invention Narrative: At its core, a patent tells a story of invention: “There was a long-felt but unsolved problem, and I discovered a surprising, non-obvious solution.” A successful IPR petition must systematically deconstruct this narrative. It must build a compelling counter-narrative, showing that the “problem” was well-known, the potential “solutions” were readily available in the prior art, and that combining them was not an act of inventive genius but a matter of routine, predictable experimentation .

Ultimately, drafting a successful petition requires an intimate collaboration between legal counsel and technical experts. The goal is to create a document that is not just a legal brief but a rigorous technical paper designed to persuade an audience of highly skeptical peer reviewers—the APJs—that the challenged patent claims do not represent a genuine invention and should never have been granted.

The Innovator’s Defense: Strategies for Protecting Patents at the PTAB

For an innovator pharmaceutical company, the filing of an IPR petition against a key patent is a direct assault on a revenue-generating asset. Mounting a successful defense requires a multi-layered strategy that begins long before a petition is ever filed and continues through every phase of the PTAB proceeding. It is a battle fought with procedural tactics, deep technical evidence, and strategic foresight.

The Preliminary Response: The First and Best Chance to Avoid Institution

Once an IPR petition is filed, the patent owner’s first opportunity to fight back is the Patent Owner’s Preliminary Response (POPR). This optional brief, filed within three months of the petition, is the patent owner’s one and only chance to persuade the PTAB not to institute the trial in the first place . A successful POPR can end the threat quickly and efficiently, avoiding the cost and risk of a full trial.

The strategic approach to the POPR is a subject of intense debate. One school of thought advocates for focusing primarily on procedural arguments and grounds for discretionary denial. This includes arguing that:

- The petition is time-barred under 35 U.S.C. § 315(b) .

- The PTAB should exercise its discretion to deny under the Fintiv factors due to an advanced parallel district court litigation .

- The petition should be denied under 35 U.S.C. § 325(d) because the same or substantially the same prior art and arguments were already considered by the USPTO during the original examination .

This approach has the advantage of not revealing the patent owner’s full hand on the technical merits of the case. A detailed rebuttal of the petitioner’s invalidity arguments in the POPR could serve as a roadmap for the petitioner, helping them prepare their expert for deposition and craft a more effective reply brief if the trial is instituted .

However, a purely procedural POPR can be a missed opportunity. Recent data suggests that submitting a rebuttal expert declaration with the POPR can be an effective strategy. One analysis found that the institution rate was significantly lower in cases where the patent owner filed pre-institution expert testimony compared to cases where they did not . This indicates that a targeted, powerful rebuttal on the merits—a “silver bullet” argument that exposes a fatal flaw in the petitioner’s technical case—can be enough to convince the Board to deny institution.

The decision, therefore, is a high-stakes gamble. It requires a cold-eyed assessment of the relative strengths of one’s procedural and substantive defenses. If a knockout punch on the merits exists, it may be worth throwing it in the POPR. If the defense is more nuanced and likely to be a war of attrition, it may be wiser to save the heavy artillery for the post-institution Patent Owner Response and focus the POPR on derailing the proceeding before it can even begin.

Prosecuting for Resilience: Drafting Claims to Withstand Future PTAB Scrutiny

By far the most effective defense against an IPR begins years, or even a decade, before the petition is filed: during the original patent prosecution. In the post-AIA world, it is no longer sufficient for a patent prosecutor to simply secure an allowance from a USPTO examiner. The new imperative is to draft and prosecute a “PTAB-resilient” patent—one that is forged with the expectation that it will one day face a rigorous, adversarial challenge where its validity is not presumed.

This requires a fundamental shift in the philosophy of patent drafting. The drafter’s audience is not just the examiner, but a future panel of APJs and the petitioner’s expert witness, who will scrutinize every word of the specification and every argument made during prosecution. Key strategies for building this resilience include:

- Building a Rich Specification: The patent’s written description is the foundation of its defense. It should be drafted to provide a deep and varied disclosure, including multiple working examples, data supporting unexpected results, and alternative embodiments . This creates a deep well of support for the claims and provides fallback positions if broader claims are challenged.

- Acting as Your Own Lexicographer: Ambiguity in claim language is a petitioner’s best friend. To control the narrative during a future dispute, the specification should include a clear glossary of key terms, explicitly defining them in a way that supports a favorable claim construction . This preempts arguments that a term should be given a broader, more vulnerable interpretation.

- Creating a Cascade of Claims: The claim set should be structured like a fortress with multiple layers of defense. It should include broad independent claims to capture the full scope of the invention, but also a robust set of narrower dependent claims . These dependent claims serve as critical fallback positions; even if the broadest claims are invalidated in an IPR, a narrower dependent claim covering the commercial embodiment of the drug can be enough to preserve market exclusivity.

- Embedding Evidence of Non-Obviousness: The specification should be used to tell the story of the invention in a way that highlights its non-obviousness. This includes describing the state of the art at the time, the failures of others who tried to solve the problem, and any objective evidence of non-obviousness (also known as secondary considerations), such as commercial success, long-felt but unmet need, or unexpected results . By embedding this evidence directly into the patent’s disclosure, the patent owner creates a powerful record that can be used to rebut an obviousness challenge years later.

Ultimately, patent prosecution and litigation strategy can no longer be viewed as separate, sequential disciplines. They must be fully integrated. The upfront investment in drafting a “gold-plated” patent application—one with extensive data, precise definitions, and a strategically layered claim set—is a fraction of the cost of defending a poorly drafted patent in a multi-million dollar IPR. This requires a paradigm shift in how pharmaceutical companies approach, budget for, and execute their patent prosecution strategies.

The Aftermath: The Powerful and Complex Effects of IPR Estoppel

An IPR proceeding does not end with the PTAB’s final written decision. Its consequences ripple outward, profoundly impacting any parallel or subsequent district court litigation through the powerful and complex doctrine of estoppel. For patent owners, estoppel is the “grand bargain” of the AIA—the shield they receive in exchange for enduring the risks of an IPR. For petitioners, it represents a high-stakes limitation on their ability to fight on. Understanding the evolving contours of IPR estoppel is critical to appreciating the long-term strategic implications of a PTAB challenge.

“Raised or Reasonably Could Have Raised”: Defining the Scope of Estoppel

The statutory basis for IPR estoppel is found in 35 U.S.C. § 315(e)(2). It dictates that after the PTAB issues a final written decision, the petitioner is barred (or “estopped”) from asserting in a district court that a claim is invalid “on any ground that the petitioner raised or reasonably could have raised” during the IPR .

Initially, the application of this rule was complicated by the PTAB’s practice of instituting trial on only some of the claims or grounds presented in a petition. However, the Supreme Court’s 2018 decision in SAS Institute, Inc. v. Iancu clarified the landscape by holding that the PTAB must issue a final written decision addressing every claim the petitioner challenges . This decision broadened the potential scope of estoppel, as a final written decision now covers the entirety of the petitioner’s challenge.

The central battleground has since shifted to the meaning of the phrase “reasonably could have raised.” This is not a simple question. Does it mean any prior art reference that existed anywhere in the world at the time the petition was filed? The Federal Circuit has provided crucial guidance, holding that the standard is what “a skilled searcher conducting a diligent search reasonably could have been expected to discover” .

This standard has created a new “case within a case” in district court litigation. To invoke estoppel, a patent owner can no longer simply point to the existence of a prior art reference. They must now present evidence—potentially including testimony from search experts—that the petitioner should have found that reference during a reasonably diligent search before filing their IPR . This forces both sides to meticulously document their prior art search methodologies. For a petitioner, a comprehensive and well-documented search is now a defensive necessity, not only to build a strong petition but also to define and limit the universe of prior art they could be estopped from using later. For a patent owner, conducting their own exhaustive search to uncover art the petitioner missed has become a key offensive tactic to broaden the scope of estoppel and block the challenger’s arguments in court.

Strategic Loopholes: How System and Product Art Complicate Estoppel

A recent and dramatic evolution in estoppel law has created what many see as a significant loophole for patent challengers. The Federal Circuit has repeatedly narrowed the scope of estoppel by focusing on the limited types of invalidity arguments that can be brought in an IPR.

By statute, an IPR challenge is restricted to grounds of anticipation (§ 102) and obviousness (§ 103) based “only on the basis of prior art consisting of patents or printed publications” . A challenger cannot, for example, argue in an IPR that a patent is invalid because the invention was previously in public use, on sale, or that the patent’s specification fails to meet the enablement and written description requirements of § 112.

Seizing on this limitation, the Federal Circuit, in cases like IOENGINE, LLC v. Ingenico Inc., has held that IPR estoppel does not apply to invalidity grounds that could not have been raised in the IPR . This means a petitioner who loses an IPR is free to challenge the very same patent claims in district court based on prior public use or on-sale activity.

More startlingly, the court has held that this loophole extends even when the physical product or system used to support the “public use” argument in court is the exact same one described in the printed publication that failed in the IPR . Consider this powerful strategic scenario:

- A generic challenger discovers a user manual (a printed publication) for a prior art medical device that it believes invalidates a key formulation patent. It also obtains the physical device itself.

- The challenger files an IPR, arguing the patent is obvious over the user manual. The PTAB disagrees and issues a final written decision upholding the patent’s validity.

- In the parallel district court litigation, the challenger is now estopped from using the user manual to argue obviousness. However, they are not estopped from arguing that the patent is invalid because the physical device was in public use before the patent was filed .

- The challenger can then introduce the very same user manual, not as the basis for an obviousness argument, but as evidence to explain how the physical device works and what it taught to the public.

This allows the challenger to effectively re-litigate the core of their failed IPR argument under a different statutory heading. It creates a “two bites at the apple” scenario that fundamentally de-risks the IPR process for petitioners. A loss at the PTAB is no longer a fatal blow to their validity case. This development incentivizes a bifurcated attack: use the PTAB for all publication-based challenges, and hold all product- and system-based art in reserve for a second wave of attack in district court. For patent owners, this means an IPR victory may be a hollow one, offering no true finality and forcing them to fight the same substantive battle all over again in a more expensive forum.

By the Numbers: A Data-Driven Look at PTAB Outcomes in Pharma

While legal doctrine and strategy are crucial, the most effective business decisions are grounded in data. The USPTO provides a wealth of statistics on PTAB proceedings, allowing for a quantitative analysis of the risks and probabilities associated with challenging pharmaceutical patents . A close examination of this data reveals striking differences in outcomes between traditional small-molecule drugs and modern biologics, offering critical insights for portfolio managers and litigation strategists.

Small Molecules vs. Biologics: Analyzing the Disparate Outcomes for Orange Book and Purple Book Patents

The data on petitions challenging patents listed in the FDA’s Orange Book (which covers small-molecule drugs) and patents covering biologics (often associated with the FDA’s Purple Book) tells a tale of two very different battlefields .

Cumulatively since the PTAB’s inception, the overall institution rates for petitions against these two types of patents have been remarkably similar. According to a 2024 USPTO report, the institution rate for petitions challenging Orange Book patents was 62%, while for biologic patents it was 61% . This suggests that petitioners in both spaces are equally adept at presenting a plausible case for invalidity that meets the “reasonable likelihood” threshold.

However, the story changes dramatically once a trial is instituted. The post-institution outcomes reveal a stark divergence:

- For Orange Book patents, the fight is much closer to a fair one. Of all instituted claims, only 33% are ultimately found unpatentable in a final written decision . When looking at the outcome on a per-patent basis for cases that reach a final decision, the results are nearly a coin flip, with patent owners winning outright about as often as they lose .

- For biologic patents, the outlook for the patent owner is far grimmer. Of all instituted claims, a staggering 59% are found unpatentable . For biologic patents that receive a final written decision, they are more than three times as likely to have all challenged claims invalidated than to have all claims survive (70% vs. 21%) .

This statistical chasm suggests that the nature of innovation and patenting in the world of biologics is fundamentally different and, in many ways, more vulnerable to a PTAB challenge. Small-molecule innovation often centers on the discovery of a novel active pharmaceutical ingredient (API). The core “composition of matter” patents protecting these molecules are scientifically robust and notoriously difficult to invalidate in any forum . The PTAB challenges in this space, therefore, tend to focus on the weaker secondary patents in the “thicket”—formulations, methods of use, etc.—which have more variable outcomes.

Biologic innovation, in contrast, is often as much about the process as the product. Patents for biologics frequently cover complex manufacturing methods, cell culture conditions, purification techniques, and diagnostic assays . While these are legitimate and valuable inventions, they can be more susceptible to obviousness challenges that combine various known techniques from the prior art. Furthermore, biologics are often protected by much denser patent thickets, with one study finding a median of 14 patents per biologic compared to just 3 for a small-molecule drug . This simply creates more targets for a biosimilar challenger to attack.

These trends have not gone unnoticed. The number of IPR petitions filed against Orange Book patents has steadily declined since its peak in 2015, while the number of petitions targeting biologic patents has been on the rise . The market is adapting to the data. The risk/reward calculus for a biosimilar challenger is now clear: while getting an IPR instituted may be a challenge, the probability of a decisive victory after institution is significantly higher than for their small-molecule counterparts. This reality justifies a more aggressive and well-funded IPR strategy in the biosimilar space.

The following table summarizes the key performance indicators for PTAB challenges in the pharmaceutical sector, providing the quantitative foundation for these strategic insights.

Table 2: PTAB Outcomes for Pharmaceutical Patents (Cumulative Data, FY2013 – Q2 FY2024)

| Metric | Orange Book (Small Molecule) Patents | Biologic Patents | All Technologies (for comparison) |

| Total Petitions Filed | 771 | 393 | >18,000 |

| Institution Rate (by petition) | 62% | 61% | ~68% |

| Post-Institution Outcomes (as % of instituted petitions) | |||

| All Claims Upheld in FWD | 33% | 11% | ~19% |

| Mixed Decision in FWD | 5% | 5% | ~17% |

| All Claims Invalidated in FWD | 33% | 40% | ~60-70% |

| Overall Outcomes (as % of total petitions) | |||

| Institution Denied | 41% | 39% | ~32% |

| Settled (Pre- or Post-Institution) | 24% | 20% | ~32% |

| All Claims Upheld in FWD | 15% | 6% | Varies |

| All Claims Invalidated in FWD | 15% | 22% | Varies |

| Invalidation Rate of Instituted Claims | 33% | 59% | ~70-80% |

| *Source: Data compiled and synthesized from USPTO PTAB Statistics reports * |

Lessons from the Battlefield: Influential Case Studies

To truly grasp the strategic nuances of the PTAB, we must move beyond statistics and doctrines to examine how these forces play out in the real world. A few high-profile cases have served as crucibles, testing the limits of the IPR system and establishing precedents that continue to shape the landscape for all pharmaceutical and biotech companies.

The Kyle Bass Campaign: A Hedge Fund’s Assault on “Bad” Drug Patents

In 2015, the pharmaceutical industry was confronted with a novel and deeply unsettling threat. Kyle Bass, a prominent hedge fund manager known for successfully betting against the subprime mortgage market, turned his attention to drug patents . Through a newly formed entity called the “Coalition for Affordable Drugs,” Bass launched a volley of 35 IPR petitions targeting patents on blockbuster drugs from companies like Celgene, Shire, and Biogen .

His strategy was not that of a traditional generic competitor seeking to launch a product. Instead, it was a form of financial arbitrage. Bass’s firm would take a short position on a pharmaceutical company’s stock, betting that its value would fall. Then, they would file an IPR petition challenging one of the company’s key patents and publicize the filing. The mere news of a patent challenge, particularly in the feared “death squad” of the PTAB, was often enough to send a company’s stock price tumbling, allowing Bass to profit from his short position . Bass framed his campaign in populist terms, claiming he was targeting “BS patents” and working to lower drug prices for consumers .

The targeted pharmaceutical companies were outraged, crying foul and labeling Bass a “reverse patent troll” who was abusing the IPR process for financial manipulation . Celgene filed a motion for sanctions with the PTAB, arguing that the IPR system was intended as an alternative to litigation for parties with a commercial interest, not as a tool for hedge funds to play the stock market .

The PTAB’s response was a landmark moment for the IPR system. In a decisive ruling, the Board denied the motion for sanctions, stating unequivocally that “Profit is at the heart of nearly every patent and nearly every inter partes review” . The Board found nothing in the AIA statute that limited the filing of IPRs to competitors or parties with a direct commercial stake. Congress, the PTAB reasoned, had intentionally created a system open to “any person who is not the owner of the patent” to file a challenge in order to improve overall patent quality .

The Kyle Bass saga was a stress test that revealed a fundamental design feature of the IPR system: its complete lack of a standing requirement. Unlike in district court, where a party must have suffered a concrete injury to sue, the doors to the PTAB are open to all . While Bass’s campaign ultimately had mixed results—achieving a 57% institution rate but a much lower success rate in final decisions—it established a powerful and disruptive proof-of-concept . It demonstrated that the PTAB could be weaponized by actors entirely outside the pharmaceutical industry, creating a new and unpredictable risk vector for any publicly traded life sciences company. Your patent portfolio is now vulnerable not just to your competitors, but to the full force of the financial markets.

Amgen v. Sanofi: A Landmark Enablement Decision with Lasting Impact

While the Kyle Bass campaign tested the procedural boundaries of the PTAB, the Supreme Court’s 2023 decision in Amgen v. Sanofi fundamentally reshaped the substantive law of patent validity, with profound implications for all future patent challenges, including those at the PTAB .

The case centered on Amgen’s patents for its cholesterol-lowering drug, Repatha®. The patents did not claim the antibody by its specific amino acid sequence. Instead, they used functional language to claim the entire genus of antibodies that perform two functions: (1) binding to a specific sweet spot on the PCSK9 protein, and (2) blocking PCSK9 from destroying LDL receptors . Amgen’s specification disclosed the structures of 26 antibodies that performed this function, but the claims were broad enough to potentially cover millions of other undisclosed antibodies that could also do the same job . Sanofi, which developed a competing drug, Praluent®, challenged the patents as invalid, arguing that the specification did not “enable” a person skilled in the art to make and use the full scope of the claimed invention without undue experimentation, as required by 35 U.S.C. § 112 .

In a unanimous decision, the Supreme Court sided with Sanofi, invalidating Amgen’s claims . Justice Gorsuch, writing for the Court, articulated a clear principle: “the more one claims, the more one must enable” . The Court found that Amgen’s specification, which provided a few examples and a general “roadmap” for finding more, was insufficient to justify a monopoly over a vast and potentially limitless class of antibodies. It was, the Court concluded, little more than a “hunting license” or a “research assignment,” forcing other scientists to engage in the same “painstaking experimentation” that Amgen’s own scientists had to perform .

Although Amgen v. Sanofi was a district court case, its impact on PTAB proceedings has been immediate and significant. The decision has armed petitioners with a powerful new weapon, particularly in the biologics space where broad, functionally-defined genus claims are common.

The most direct impact is in Post-Grant Review (PGR) proceedings. Unlike IPRs, which are limited to prior art challenges, PGRs (which must be filed within nine months of a patent’s grant) can be based on any ground of invalidity, including § 112 enablement . The Amgen decision provides powerful Supreme Court precedent that biosimilar challengers can now wield in PGRs to attack broad biologic patents at their very foundation. This makes the first nine months of a new biologic patent’s life a period of acute vulnerability.

Even in IPRs, where enablement cannot be a formal ground for invalidity, the Amgen decision can exert a subtle influence on claim construction. APJs, aware of the high bar for enablement set by the Supreme Court, may be more reluctant to adopt broad interpretations of functional claim language if the underlying specification appears thin. The decision forces innovators across all technologies to rethink their drafting strategy, compelling them to provide a much more robust and representative set of examples to justify the breadth of the protection they seek.

The Strategic Edge: Leveraging Competitive Intelligence

In the complex, high-stakes chessboard of modern pharmaceutical patent disputes, information is power. The ability to anticipate a competitor’s move, identify a patent’s hidden weakness, or foresee a shift in the legal landscape can be the difference between a multi-billion dollar market victory and a catastrophic loss of exclusivity. In this environment, a reactive, purely legal approach is no longer sufficient. Winning requires a proactive, data-driven competitive intelligence operation.

How Platforms Like DrugPatentWatch Inform PTAB and Litigation Strategy

The sheer volume and complexity of data involved in pharmaceutical IP—from global patent filings and prosecution histories to ongoing litigation and regulatory updates—is overwhelming. This is where specialized competitive intelligence platforms become indispensable tools. Services like DrugPatentWatch are designed to aggregate this disparate information into a single, actionable dashboard, providing the raw data necessary for sophisticated strategic planning .

These platforms offer a suite of tools that are directly relevant to crafting a winning PTAB and litigation strategy:

- Global Patent and Exclusivity Tracking: At the most basic level, these services provide comprehensive, up-to-date information on the patent and regulatory exclusivity status for drugs in over 130 countries . This allows a company to monitor the entire competitive landscape, not just its own portfolio.

- Litigation and PTAB Monitoring: Crucially, platforms like DrugPatentWatch track ongoing legal challenges, including Hatch-Waxman lawsuits and IPR petitions . This serves as an early warning system. An innovator can see which competitors are filing ANDAs or IPRs against drugs in the same therapeutic class, signaling potential future challenges to their own products. A generic company can monitor all litigation involving a target patent, which is essential for assessing Fintiv risk and strategically timing its own IPR filing .

- Forecasting Generic and Biosimilar Entry: By integrating patent expiry dates, litigation outcomes, and regulatory data, these platforms can forecast likely dates for generic and biosimilar market entry . This intelligence is vital for both sides—innovators use it for revenue forecasting and lifecycle management, while generics use it to inform their launch preparations and portfolio decisions.

However, the true strategic value of these platforms lies not just in data aggregation, but in enabling a predictive and analytical approach. As one user of DrugPatentWatch noted, a key benefit is the ability to “study failed patent challenges to develop a better strategy” . Imagine a generic company preparing to challenge a patent on an extended-release formulation. Before spending hundreds of thousands of dollars on an IPR, they can use a platform to analyze every prior PTAB decision involving similar formulation patents. They can see which prior art references were persuasive to the Board, which expert arguments succeeded, and which legal theories failed. This allows them to learn from the successes and failures of others, dramatically increasing the probability of success for their own petition.

In the PTAB era, patent strategy is no longer a siloed, reactive legal function. It is a continuous, data-driven intelligence operation that must be integrated across a company’s legal, business development, and R&D departments . Platforms like DrugPatentWatch provide the essential raw material for this operation, empowering strategists to move beyond decisions based on legal doctrine alone and toward a more sophisticated model based on statistical probabilities, competitor behavior, and dynamic market intelligence.

The Road Ahead: The Evolving PTAB Landscape and Its Future Impact

The PTAB is not a static institution. Its procedures, precedents, and even its core philosophy are in a constant state of evolution, shaped by new legislation, court decisions, and, increasingly, the policy priorities of the current USPTO leadership. For pharmaceutical companies whose product lifecycles span decades, understanding these trends and anticipating future shifts is essential for long-term strategic planning.

The Director’s Growing Influence: Director Review and Discretionary Denials

One of the most significant recent developments is the rising influence of the USPTO Director over PTAB proceedings. The Supreme Court’s Arthrex decision, by establishing the Director’s authority to review and overturn PTAB decisions, created a new and powerful mechanism of oversight . This has made the PTAB a more political body, with its approach to key issues often reflecting the policy leanings of the administration in power.

This is most evident in the fluctuating application of discretionary denials. Under the leadership of Director Andrei Iancu during the Trump administration, the PTAB took a more aggressive stance on using its discretion to deny IPRs, most notably through the Fintiv framework . The subsequent Director under the Biden administration, Kathi Vidal, initially signaled a retreat from this practice. More recently, however, under Acting Director Coke Morgan Stewart, the USPTO has not only revived but formalized and expanded the use of discretionary denials .

A new “bifurcated” process has been implemented, where discretionary denial issues are briefed and decided by the Director’s office before a panel of APJs even considers the technical merits of the petition . This front-loads the procedural fight and gives the Director’s office a powerful gatekeeping function.

Furthermore, a new and somewhat amorphous concept of “settled expectations” has emerged as a basis for denial . The idea is that the PTAB may decline to institute review of a patent that has been issued and in force for many years, particularly if the petitioner could have challenged it earlier. This doctrine appears to be coalescing around a rough six-year mark from issuance, creating a potential safe harbor for older patents .

This trend introduces a significant new layer of political and policy risk into the strategic equation. The “rules of the game” at the PTAB are no longer just a matter of statute and case law; they are subject to the shifting winds of administrative policy. A patent challenged in 2025 may face a very different discretionary denial landscape than one challenged in 2029 after a change in administration. This unpredictability may, over the long term, diminish the appeal of the PTAB as a primary challenge venue and push some disputes back toward the more procedurally stable—though slower and more expensive—federal courts. Long-term patent portfolio strategy must now account not only for legal and market risk, but for political risk as well.

Conclusion: Mastering the Dual-Track Chessboard

The emergence of the Patent Trial and Appeal Board has irrevocably transformed the landscape of pharmaceutical patent enforcement. The once linear and predictable path of Hatch-Waxman litigation has been replaced by a complex, multi-dimensional chessboard, where innovators and challengers must simultaneously wage battles on two distinct fronts. Mastery of this new environment requires more than just legal expertise; it demands a holistic, data-driven, and relentlessly proactive strategic mindset.

For innovator companies, the mission is one of fortification and foresight. The best defense is no longer a single, strong patent, but a thoughtfully constructed portfolio, prosecuted from day one with the expectation of an adversarial challenge. It means building patent thickets not just for volume, but for strategic depth, with a cascade of claims of varying scope. It means embedding the story of non-obviousness into the very fabric of the patent’s specification. And when a challenge arrives, it means wielding procedural tools like venue selection and discretionary denial arguments as potent strategic weapons to neutralize the PTAB threat before it can fully materialize.

For generic and biosimilar manufacturers, the PTAB offers an unprecedented offensive capability, but one that must be deployed with surgical precision. The decision to file an IPR is a complex calculus of timing, risk, and reward, weighing the PTAB’s favorable standards against the potential loss of 180-day exclusivity and the peril of estoppel. Success hinges on crafting a “linchpin” petition that is both a legal brief and a technical dissertation, and on strategically navigating the interplay between the PTAB’s rapid timeline and the slower, more deliberate pace of the district court.

For both sides, the path forward is clear: strategy can no longer be siloed. Patent prosecution, litigation, regulatory affairs, and business development must be deeply integrated. The war for market share will be won by those who can see the entire board, who understand the intricate connections between a claim’s wording and its vulnerability at the PTAB, between a lawsuit’s venue and the odds of discretionary denial, and between a PTAB victory and the powerful, lasting consequences of estoppel. The collision of these two worlds has created a more complex and challenging environment, but for those who can master its rules, it has also created new and powerful opportunities to achieve a decisive competitive advantage.

Key Takeaways

- The PTAB and Hatch-Waxman Are a Mismatch: The PTAB was created to solve the tech industry’s “patent troll” problem, not to reform pharmaceutical patent law. This fundamental mismatch creates inherent friction and strategic complexity, as two systems with different goals and philosophies are forced to interact.

- Effective Patent Life Drives the Conflict: The 7-10 years of actual market exclusivity an innovator receives is the key economic driver. It forces innovators to build “patent thickets” to extend revenue streams, and it incentivizes generics to use the PTAB to dismantle those thickets and accelerate market entry.

- The PTAB is Not a Monolithic “Death Squad”: While overall invalidation rates are high, the data for pharmaceuticals is highly nuanced. Orange Book (small molecule) patents have a roughly 50/50 chance of surviving a final PTAB decision, while biologic patents are invalidated at a much higher rate (70%). Strategy must be tailored to these different risk profiles.

- Procedural Differences Create Strategic Arbitrage: The PTAB’s lower burden of proof (“preponderance of the evidence”) and expert judges make it a favorable forum for challengers to test invalidity arguments and gain immense leverage in parallel district court litigation.

- Timing is Everything: The one-year bar to file an IPR after being sued, combined with the risk of a Fintiv discretionary denial based on the court’s trial schedule, forces challengers to make critical, front-loaded strategic decisions about whether and when to open a second front at the PTAB.

- Estoppel Has Powerful (But Leaky) Consequences: Losing an IPR can bar a challenger from re-litigating invalidity arguments in court. However, recent court decisions have created a significant loophole, allowing challengers to use prior art based on physical products or systems in court, even if a challenge based on publications describing those systems failed at the PTAB.

- Competitive Intelligence is Non-Negotiable: In this dual-track environment, success depends on a proactive, data-driven strategy. Platforms like DrugPatentWatch are essential tools for monitoring the competitive landscape, analyzing past PTAB outcomes, and making informed decisions about litigation and IPR strategy.

- The PTAB Landscape is Constantly Evolving: The growing influence of the USPTO Director means that PTAB procedures, particularly around discretionary denials, are subject to policy shifts. Long-term strategy must now account for this political and administrative uncertainty.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. As a generic manufacturer and the first to file a Paragraph IV certification, should I file an IPR on a patent I believe is weak? What are the risks?

This is a classic strategic dilemma. Filing an IPR offers the advantage of a lower burden of proof and a faster decision from technically expert judges, potentially invalidating the patent and clearing your path to market. However, the risks are substantial. First, by winning in a public forum like the PTAB, you may invalidate the patent for everyone, potentially destroying the value of your 180-day first-filer exclusivity by allowing other generics to launch alongside you. Second, if you lose the IPR, you will be subject to estoppel, preventing you from raising the same invalidity arguments in your district court case. The strategic decision often comes down to a risk assessment: if your invalidity case is overwhelmingly strong and you believe you can win quickly at the PTAB, it might be worth the risk. If your case is more nuanced, or if the 180-day exclusivity is particularly valuable, it is often more prudent to keep the fight within the traditional Hatch-Waxman litigation framework to protect your exclusivity period.

2. As an innovator, my blockbuster drug is protected by a patent that has been in force for over 10 years. Does the age of my patent offer any protection against a new IPR challenge?

Yes, increasingly, it might. Under recent guidance from the USPTO, the concept of a patent owner’s “settled expectations” has emerged as a factor in discretionary denial decisions . The argument is that after a patent has been issued for a significant period, has been licensed, and has formed the basis for substantial investment, the patent owner has a reasonable expectation of its validity. The PTAB may be reluctant to disrupt these settled expectations with a new challenge, particularly if the petitioner could have brought the challenge years earlier. While there is no hard-and-fast rule, this doctrine appears to be gaining traction for patents that are more than six to eight years old. Therefore, the age of your patent, combined with evidence of industry reliance and investment, can be a powerful argument in a preliminary response seeking discretionary denial.

3. What is the single most important thing I can do during patent prosecution to make my company’s patents more resilient to future PTAB challenges?

The single most important thing is to draft the patent specification with the explicit assumption that it will be litigated at the PTAB. This means going beyond what is merely necessary to get the patent allowed by an examiner. Specifically, you should create a rich and detailed disclosure that includes a robust set of working examples, data supporting any claims of unexpected results, and clear, unambiguous definitions for all critical claim terms . Furthermore, draft a deep cascade of dependent claims of varying scope. These narrower claims serve as crucial fallback positions. Even if a broad independent claim is invalidated by the PTAB, a dependent claim that specifically covers your commercial product can be enough to survive the challenge and preserve your market exclusivity. This “prosecution for litigation” mindset is the best long-term defense.

4. My company lost an IPR based on a combination of two scientific articles. Can I still argue in district court that the patent is invalid based on a prior art device that is described in those same two articles?

Under the current interpretation of IPR estoppel by the Federal Circuit, the answer is likely yes. This is a critical strategic loophole . IPR estoppel only applies to grounds that “were raised or reasonably could have been raised” during the IPR. Since IPRs are limited to grounds based on patents and printed publications, an invalidity ground based on a prior public use or on-sale activity involving a physical device could not have been raised. Therefore, you would be estopped from using the two scientific articles as the basis for an obviousness argument in court. However, you would not be estopped from arguing that the physical device itself renders the patent invalid due to prior public use. You could then use the same two articles as evidence to explain to the court what the device is and how it works. This allows you to effectively re-litigate the same core technical argument under a different statutory heading.

5. We are a biosimilar developer. The statistics show that biologic patents are invalidated at a much higher rate than small-molecule patents after PTAB institution. Why is this, and how should it affect our strategy?

The disparity in outcomes is significant and likely stems from the different nature of the patents themselves . Small-molecule drugs are often protected by a core composition-of-matter patent on the API, which is very difficult to invalidate. Biologics, being large and complex molecules, are often protected by a wider array of patents covering manufacturing processes, cell lines, purification methods, and formulations. These “process” type patents are often more susceptible to obviousness challenges at the PTAB, where technically expert judges can readily assess whether a combination of known techniques would have been obvious to a skilled artisan. This statistical reality should make you more aggressive in your use of the PTAB. While the overall institution rate for biologic patents is similar to small-molecule patents, your probability of a decisive win if trial is instituted is substantially higher. This justifies a greater upfront investment in preparing high-quality IPR petitions as a primary part of your market entry strategy.

References

- EY. (n.d.). Navigating pharma loss of exclusivity. Retrieved from https://www.ey.com/en_us/insights/life-sciences/navigating-pharma-loss-of-exclusivity

- Torrey Pines Law. (n.d.). Pharmaceutical Lifecycle Management. Retrieved from https://torreypineslaw.com/pharmaceutical-lifecycle-management.html

- DrugPatentWatch. (n.d.). How Long Do Drug Patents Last? Retrieved from https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/how-long-do-drug-patents-last/

- Rathore, S.S. (2011). The new drug discovery research: The past, the present, and the future. Indian Journal of Pharmacology, 43(3), 236-240.

- DrugPatentWatch. (n.d.). Optimizing Your Drug Patent Strategy: A Comprehensive Guide for Pharmaceutical Companies. Retrieved from https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/optimizing-your-drug-patent-strategy-a-comprehensive-guide-for-pharmaceutical-companies/

- AJMC. (2016). The Role of Patents and Exclusivities in Drug Pricing. Retrieved from https://www.ajmc.com/view/a636-article

- U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. (n.d.). Manual of Patent Examining Procedure.