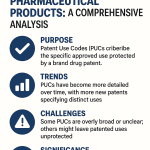

Introduction: The Patent as a Strategic Business Asset

Beyond Legal Protection: Framing the Patent as the Cornerstone of Pharmaceutical Commercial Viability

In the high-stakes, capital-intensive world of pharmaceutical research and development (R&D), a patent is far more than a mere legal document granting exclusionary rights. It is the fundamental pillar upon which the entire drug development ecosystem is constructed.1 For pharmaceutical companies, a robust patent portfolio is a core business asset and a critical financial instrument that dictates market exclusivity, de-risks investment, and ultimately enables the commercial viability of multi-billion-dollar R&D programs.1 The strategic significance is profound; patents are consistently recognized as the “backbone of medical innovation” and the “cornerstone of pharmaceutical innovation”.1 They function as tangible assets that provide the freedom to operate and are indispensable for recouping the substantial investments inherent in discovering, developing, and bringing a new therapy to market.2 In this landscape, patent management has transcended legal formality to become a “core business strategy essential for sustaining revenue streams and supporting continuous investment in innovation”.2

The economic model of the pharmaceutical sector is distinctive, seeking to balance the critical need for innovation incentives with the societal demand for public access to medicines.1 This model is predicated on the temporary market exclusivity that patents provide. Without this protection, the financial incentive to undertake high-risk, high-investment ventures would be severely diminished, potentially stifling the development of novel therapies.1 A strong patent portfolio acts as a magnet for investment, signaling a protected market opportunity that can yield a significant return on substantial capital.1 For investors, patents serve as a crucial “insurance policy,” offering a “clear path to profitability” in a notoriously uncertain industry.1 This direct causal link between strong patent protection and the willingness of investors to fund innovation is paramount. Consequently, patent strategy is not confined to the legal department; it is a fundamental element influencing decisions on which drug candidates to pursue, how to structure R&D investments, and how to finance development from the earliest stages.1

The Fundamental Bargain: Public Disclosure for Market Exclusivity

The global patent system operates on a foundational quid pro quo, or a fundamental bargain between the inventor and the public.2 In exchange for a temporary monopoly—the right to exclude others from making, using, selling, or importing the patented invention for a limited term—the inventor must provide a full, clear, and enabling public disclosure of the invention.6 This disclosure serves two vital public purposes. First, it enriches the collective store of technical knowledge, teaching the public how the invention works and allowing others to build upon it, thereby fostering further innovation.8 Second, upon the expiration of the patent term, the disclosure must be sufficient to enable a person skilled in the relevant technical field to practice the invention, ensuring it enters the public domain for the benefit of all.8 This bargain is central to the legitimacy of the patent system, and the entire process of drafting an effective patent application must be framed within the context of fulfilling this obligation. As will be explored, failure to provide an adequate disclosure that justifies the scope of the claimed monopoly is a primary and increasingly successful ground for patent invalidation.7

The very structure of this bargain creates a self-reinforcing cycle of escalating R&D costs and the strategic necessity for ever-stronger patent protection. The average capitalized cost to develop a new drug has reached an astonishing $2.23 billion in 2024, a figure that reflects not only direct spending but also the cost of the many failed candidates for every one that succeeds.3 This immense financial risk makes robust patent protection an absolute necessity to attract the venture capital and other forms of investment required to fund such endeavors.1 Investors, facing these odds, demand the security of an iron-clad patent portfolio before committing capital. Simultaneously, evolving legal standards, particularly in the United States following landmark Supreme Court decisions like

Amgen Inc. v. Sanofi, have significantly raised the bar for the level of disclosure required to secure and defend a patent.7 Courts now demand that patent applications provide extensive, detailed experimental data to support the full scope of the claims, especially for broad claims covering a genus of molecules or a functional class of therapies. To meet these heightened standards, companies must conduct more extensive and expensive preclinical research to generate the required supporting data

before filing a patent application. This front-loading of data generation further inflates the initial R&D costs, which in turn increases the financial risk and makes the need for strong, defensible patents even more acute. This cycle creates a high barrier to entry, favoring large, well-capitalized organizations that can afford to generate comprehensive data packages from the outset.

Section I: The Strategic Foundation of a Pharmaceutical Patent Portfolio

1.1 The Economic Realities: Quantifying R&D Costs and the Imperative for Recoupment

The strategic importance of pharmaceutical patents is inextricably linked to the extraordinary economic realities of drug development. The journey from laboratory discovery to patient bedside is one of the most expensive and high-risk commercial undertakings in any industry. In 2024, the average cost to develop a single new pharmaceutical asset reached $2.23 billion.3 This figure, derived from analysis of the top 20 global biopharma companies, accounts not only for the direct costs of successful programs but also capitalizes the immense expense of the high attrition rates, where promising candidates are terminated after hundreds of millions of dollars have been spent.11 Some estimates place the potential R&D cost for a new drug in a range from $314 million to as high as $4.46 billion, depending on the therapeutic area and modeling assumptions.14

These costs are reflected in the massive R&D budgets of major pharmaceutical companies. Merck & Co., for example, reported an R&D budget of $17.9 billion for 2024, even after a significant decrease from the prior year.15 This level of investment is not an anomaly but a requirement for survival and growth. Data from 2021 shows that R&D intensity—R&D spending as a percentage of sales—for large pharmaceutical companies has increased to 19.3%.14 Across the entire biopharmaceutical ecosystem, R&D expenditure vastly exceeds sales and marketing (S&M) costs, with one 2021 analysis finding that for every dollar spent on S&M, U.S. companies invested $5.7 in R&D.16 This data directly refutes the common public perception that marketing costs dominate pharmaceutical spending and underscores the industry’s deep reliance on continuous, high-cost innovation. The temporary market exclusivity granted by patents is the primary, if not sole, mechanism that makes it possible to recoup these “vast costs” and generate the profits necessary to fund the next wave of research.1

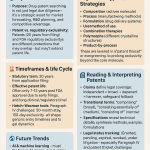

1.2 The 20-Year Term vs. Effective Market Life: Deconstructing the Timeline

A common misconception is that a pharmaceutical patent provides 20 years of market monopoly. While the statutory term for a U.S. patent is indeed 20 years from the earliest effective filing date, this figure creates a misleading impression of commercial exclusivity, often referred to as the “20-year illusion”.17 The patent clock begins ticking from the moment the application is filed, which typically occurs very early in the drug development process to secure intellectual property rights on a promising molecule.17 However, a substantial portion of this 20-year term—frequently 10 to 15 years—is consumed by the arduous and time-consuming phases of preclinical research, multi-stage clinical trials, and rigorous regulatory review by agencies like the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).17

The cumulative effect of this protracted timeline is that the “effective patent life”—the actual period during which a drug is sold on the market without direct generic competition—is significantly shorter, often closer to 7 to 10 years.17 This compressed “recoupment window” creates immense pressure on innovator companies to maximize revenue and creates the primary strategic driver for patent lifecycle management.17 To partially compensate for this erosion of the patent term, legal frameworks have been established. In the United States, the Hatch-Waxman Act provides for

Patent Term Extension (PTE), which can restore a portion of the patent term lost during the FDA’s regulatory review period.17 Additionally,

Patent Term Adjustment (PTA) can add days to a patent’s life to compensate for certain administrative delays by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) during the examination process.17 However, these extensions are capped and often do not fully restore the time lost, reinforcing the strategic importance of every day of market exclusivity.17

1.3 The Armory of Protection: A Deep Dive into Patent Types

An effective pharmaceutical patent strategy is rarely built upon a single patent. Instead, it involves the construction of a multi-layered “web of protection,” or what is often termed a “patent thicket,” utilizing a diverse array of patent types to create formidable and overlapping barriers to competition.2 Each type of patent protects a different facet of the innovation, and their strategic combination is essential for maximizing the duration and strength of market exclusivity.

- Product/Composition of Matter Patents: Widely regarded as the “crown jewels” or “gold standard” of pharmaceutical IP, these patents cover the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) itself—the new chemical entity.4 A composition of matter is defined as an instrument formed by the intermixture of two or more ingredients, possessing properties that belong to none of the ingredients in their separate state.24 This type of patent is the strongest and most fundamental form of protection because it covers the core molecule regardless of how it is formulated, manufactured, or used.25

- Formulation Patents: These patents protect the specific composition of a drug product, including the unique combination of the API with various inactive ingredients (excipients), carriers, or delivery systems.2 A novel formulation might, for example, create a time-release version of a drug, improve its stability, or enhance its bioavailability.4 As was the case with Adderall, a novel formulation of long-known amphetamine salts was eligible for patent protection, demonstrating how this patent type can extend the lifecycle of an aging but popular product.25

- Use Patents (Method of Use/Treatment): Also known as “method of use” patents, these protect a specific therapeutic application of a known product.4 This is particularly valuable for drug repurposing, where a company discovers that an existing medication is effective for treating a different disease from its original indication.4 These patents encourage further research into existing compounds, optimizing their therapeutic potential and contributing to improved healthcare outcomes.

- Process Patents: Rather than protecting the final product, a process patent protects the specific, innovative method of manufacturing a pharmaceutical.1 An innovative manufacturing process might increase the efficiency of production, improve the purity of the final compound, or enable the synthesis of a complex molecule that was previously difficult to produce.1

- Combination Patents: These patents protect therapeutic products that combine two or more active ingredients to create a new therapy.4 Such patents are particularly important in treating complex diseases like HIV/AIDS or cancer, where multi-faceted interventions that rely on synergistic effects are often required.4

| Table 1: Comparative Overview of Pharmaceutical Patent Types | |||

| Patent Type | What It Protects | Strategic Value | Key Drafting Consideration |

| Composition of Matter | The active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) molecule itself. | The “gold standard” of protection; broadest scope and most difficult for competitors to design around. | Precise definition of the chemical structure, often using Markush claims to cover a family of related compounds. |

| Formulation | The specific combination of the API with excipients, carriers, or a novel delivery system (e.g., extended-release). | Extends product lifecycle, improves patient compliance, and can create a new market for an existing drug. | Detailed description of all components and their ratios, supported by data showing an unexpected advantage (e.g., improved stability, bioavailability). |

| Use (Method of Treatment) | A new therapeutic use for a known drug (i.e., treating a new disease). | Enables drug repurposing, opening new revenue streams from existing assets with lower development risk. | Clearly linking the administration of the compound to the treatment of a specific disease, supported by efficacy data. |

| Process | The specific, innovative method of manufacturing the API or drug product. | Can provide a competitive advantage through higher efficiency, purity, or lower cost; protects manufacturing know-how. | Detailed, step-by-step description of the manufacturing process, highlighting the novel steps that lead to an improved outcome. |

| Combination | A therapeutic product containing two or more distinct active ingredients. | Protects synergistic therapies for complex diseases; creates a new product with its own exclusivity period. | Defining the specific combination of APIs and providing data to demonstrate a synergistic or additive therapeutic effect. |

1.4 Beyond Patents: Integrating Regulatory Exclusivities into Lifecycle Management

A comprehensive market protection strategy cannot rely on patents alone. It must strategically integrate a second, complementary pillar of protection: regulatory exclusivities granted by the FDA.7 Unlike patents, which are granted by the USPTO and protect inventions, regulatory exclusivity is a congressionally mandated monopoly granted by the FDA upon drug approval that prevents the agency from approving competing generic applications for a set period, regardless of patent status.8 These two forms of protection may or may not run concurrently and can cover different aspects of the drug product.27 A savvy lifecycle management plan leverages both to maximize the period of market exclusivity. Key FDA-granted exclusivities include:

- New Chemical Entity (NCE) Exclusivity: Provides five years of market protection for a drug containing an active moiety not previously approved by the FDA.8

- Orphan Drug Exclusivity (ODE): Grants seven years of market exclusivity for a drug designated to treat a rare disease or condition affecting fewer than 200,000 people in the U.S..8

- Pediatric Exclusivity (PED): A powerful incentive that adds an additional six months of market exclusivity to all existing patents and regulatory exclusivities for a given active moiety if the sponsor conducts requested pediatric studies.17

- Biologics Exclusivity: Under the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA), innovative biologic drugs are granted 12 years of data exclusivity, preventing the FDA from approving a biosimilar during that time.18

- 180-Day Generic Exclusivity: A provision of the Hatch-Waxman Act that grants 180 days of market exclusivity to the first generic applicant to successfully challenge an innovator’s patent, incentivizing litigation that can clear the way for generic competition.17

Section II: The Pillars of Patentability: Meeting the Substantive Legal Standards

To transform a scientific discovery into a legally enforceable patent, the invention must satisfy several rigorous statutory requirements. These pillars of patentability—novelty, non-obviousness, utility, and adequate disclosure—serve as the gatekeepers of the patent system, ensuring that only genuine and substantive innovations are granted the powerful right of market exclusivity.

2.1 Novelty (35 U.S.C. § 102): Defining and Defending “Newness”

The first and most fundamental requirement is novelty. An invention is considered novel if it has not been previously known, used, or publicly disclosed in any form before the patent application’s filing date.23 This body of existing public knowledge is referred to as “prior art.” For a claim to be invalidated for lack of novelty (or “anticipation”), every single element of the claimed invention must be disclosed within a single prior art reference.8

In the pharmaceutical context, establishing novelty can be particularly challenging for incremental innovations. A prime example is the patenting of polymorphs—different crystalline forms of the same active pharmaceutical ingredient.29 While a new polymorph can offer significant clinical advantages, such as improved stability, solubility, or bioavailability, a patent examiner may argue that the new form was inherently disclosed by a prior art process for making the original compound.29 To overcome such a rejection, the patent application must provide robust data demonstrating that the newly discovered polymorph possesses distinct and unexpected physical and chemical properties that differentiate it from anything previously disclosed or inherently produced.29

2.2 Non-Obviousness (35 U.S.C. § 103): Overcoming the “Obvious to Try” Hurdle

Beyond being merely new, an invention must also be non-obvious. This requirement, which is consistently one of the most common and difficult grounds for rejection to overcome, ensures that patents are not granted for trivial or predictable advancements.2 The standard is whether the differences between the invention and the prior art are such that the invention as a whole would have been obvious at the time the invention was made to a Person Having Ordinary Skill in the Art (PHOSITA).2

In pharmaceuticals, an examiner might argue that it would have been “obvious to try” a particular modification to a known compound or formulation with a reasonable expectation of success. A key strategy to rebut an obviousness rejection is to present objective evidence of non-obviousness, often referred to as “secondary considerations”.29 This evidence can include:

- Unexpected Results: Demonstrating that the invention achieved a result that was surprising or superior to what a PHOSITA would have predicted. For example, data showing a new formulation has a 10-fold increase in bioavailability when the prior art would have suggested only a minor improvement would be strong evidence of non-obviousness.29

- Commercial Success: Evidence that the product has achieved significant success in the market can suggest it fulfilled a need that was not being met by obvious solutions.

- Long-Felt but Unsolved Need: Showing that others in the field were trying and failing to solve the problem that the invention addresses.

- Failure of Others: Relatedly, evidence that others attempted similar approaches and failed can indicate that the successful path was not obvious.

Experimental data is indispensable in these arguments, as it provides the concrete evidence needed to demonstrate that the invention is more than just a predictable combination of known elements.29

2.3 Utility (35 U.S.C. § 101): Demonstrating Specific, Substantial, and Credible Usefulness

The utility requirement mandates that an invention must be useful for a practical purpose; it cannot be a mere scientific curiosity or a theoretical concept.23 In the context of pharmaceuticals, the USPTO applies a three-pronged test, requiring the asserted utility to be “specific, substantial, and credible”.8

- Specific Utility: The use must be specific to the subject matter claimed, not a general utility applicable to a broad class of chemicals. For example, claiming a compound is useful for “treating disease” is insufficient; the application must specify which disease.

- Substantial Utility: The use must have a defined, real-world benefit to the public. A compound useful only as an object of further research (e.g., a research intermediate) may lack substantial utility.

- Credible Utility: It must be believable to a PHOSITA, based on the disclosure and other available evidence, that the invention will work for its intended purpose. For a new therapeutic, this typically requires in vitro data or results from established animal models demonstrating pharmacological activity.8

2.4 The Disclosure Mandate (35 U.S.C. § 112): Satisfying Written Description and Enablement

The disclosure requirement of 35 U.S.C. § 112 is the heart of the patent bargain and has become a primary battleground in modern pharmaceutical patent litigation.7 The specification must satisfy two distinct but related requirements to justify the scope of the claims 13:

- Written Description: The patent application must contain a description of the invention that reasonably conveys to a PHOSITA that the inventor was in “possession” of the full scope of the claimed subject matter as of the filing date.7 This requirement prevents applicants from using broad, functional language to claim inventions they have not yet fully conceived. It ensures that the patent only covers what the inventor actually invented.

- Enablement: The specification must teach a PHOSITA how to make and use the full scope of the claimed invention without requiring “undue experimentation”.7 The amount of detail required depends on the predictability of the technology; in highly unpredictable fields like biotechnology and chemistry, a more robust disclosure with more working examples is necessary.33

The strategic approach to drafting a patent application is often inverted from what a layperson might expect. A common but flawed method is to first write a detailed description of the scientific work and then attempt to draft claims based on that description. The expert-level, strategic approach is the reverse. The process should begin with the claims. The claims are the legally operative part of the patent; they are the “metes and bounds” that define the scope of the monopoly and what is legally enforceable.34 The primary legal function of the specification, which includes the detailed description and examples, is to provide clear and unambiguous support for every term and limitation recited in those claims.37

By drafting the broadest commercially valuable claims first, followed by a series of progressively narrower dependent claims, the patent attorney creates a precise blueprint for the specification. This “claims-first” methodology forces a disciplined approach, ensuring that the specification is purpose-built to satisfy the legal requirements of 35 U.S.C. § 112 for the desired scope of protection. It ensures that every term used in the claims has a clear antecedent basis in the description, that every component is described in sufficient detail, and that enough examples are provided to demonstrate both possession (written description) and the ability to practice the invention (enablement) across the full claim scope.35 This method proactively minimizes the risk of a disconnect between the claims and the specification—a fatal flaw that can lead to rejections during prosecution or, even worse, a finding of invalidity during litigation where courts meticulously scrutinize the specification to interpret the meaning and scope of the claims.39

Section III: The Art of the Specification: Building the Foundation for Defensible Claims

The specification is the technical and legal heart of the patent application. It must fulfill the patent bargain by teaching the public about the invention while simultaneously providing the rock-solid foundation needed to support the legal claims. A poorly drafted specification can render even the most brilliant invention unpatentable or unenforceable.

3.1 Drafting the Detailed Description: From Broad Concepts to Specific Embodiments

The detailed description section of the specification must function as a comprehensive “instruction manual” for the invention.41 It must explain the invention with such excruciating detail that it would bore a knowledgeable reader, leaving no room for ambiguity.41 The legal standard requires the description to be “full, clear, concise, and exact” enough to enable a PHOSITA to make and use the invention without undue experimentation.32

Best practice dictates a structured approach to drafting this section. It should begin with a broad overview of the invention, its purpose, and the problem it solves, highlighting its key features and advantages over the prior art.38 Following this overview, the description should break the invention down into its constituent components and embodiments.38 For a pharmaceutical invention, this means describing the API, the excipients, the manufacturing process, and the method of administration in meticulous detail. Crucially, the detailed description must provide a clear “antecedent basis” for every single term used in the claims.37 If a claim recites “a pharmaceutically acceptable carrier,” the detailed description must have previously introduced and defined what constitutes such a carrier, providing specific examples.

3.2 The Role of Data: Strategically Employing Working and Prophetic Examples

In the unpredictable arts of chemistry and pharmaceuticals, data is not merely supportive; it is essential. The specification must provide sufficient experimental data through examples to demonstrate that the invention is useful and to satisfy the enablement and written description requirements, particularly for broad claims.33 There are two types of examples used for this purpose:

- Working Examples: These are based on actual experiments that have been performed and results that have been achieved.42 They provide the strongest possible support for the claims because they represent a reduction to practice of the invention. For a new drug, a working example might detail the synthesis of the compound, the preparation of a specific formulation, and the results of an

in vitro assay showing its biological activity. - Prophetic Examples: These are “paper examples” that describe experiments that have not yet been conducted but are based on scientifically sound predictions or extrapolations from existing data.33 Prophetic examples are a perfectly acceptable and strategically vital tool for broadening the scope of an application beyond what has been physically tested.33 For instance, after providing a working example for one formulation, an applicant might include prophetic examples for several alternative formulations to support a broader claim to a class of formulations. There is a critical rule for drafting these: prophetic examples

must be written in the present or future tense (e.g., “the compound is added…” or “the mixture will be heated…”).43 Describing a prophetic example in the past tense implies that the work was actually performed. If discovered, this can be grounds for a finding of inequitable conduct before the USPTO, rendering the entire patent unenforceable.43

3.3 Describing the Invention: Best Practices for Chemical Structures, Formulations, and Methods of Use

The level of detail required in the specification varies depending on the nature of the claimed invention.

- Chemical Structures: For a new chemical entity (a “composition of matter” claim), the structure must be described unambiguously. This typically involves providing the chemical name, a drawn structural formula, and supporting analytical data (e.g., NMR, mass spectrometry, elemental analysis) that confirms the structure. To claim a broader family or genus of related compounds, the application must define a core chemical scaffold and then specify the range of possible variable substituents, often using the Markush format.25

- Formulations: When claiming a new formulation, the description must detail not only the active ingredient but also all other components (excipients, solvents, carriers) and their relative amounts or concentration ranges.25 It is crucial to link the specific formulation to an unexpected or improved property, such as enhanced stability, increased solubility, improved bioavailability, or reduced side effects. The description should include data from comparative examples against prior art formulations to substantiate these advantages.47

- Methods of Use: For a method of treatment claim, the specification must credibly link the administration of the drug to the treatment, prevention, or diagnosis of a specific disease or condition.8 This requires more than a mere assertion. The description must provide a sound scientific rationale and supporting evidence, which can include data from

in vitro assays, cell culture studies, or established animal models, demonstrating that the drug has the claimed biological effect.48

3.4 Avoiding “Patent Profanity”: Language that Inadvertently Narrows Scope

During patent litigation, every word in the specification is subject to intense scrutiny. Certain words and phrases, often termed “patent profanity,” can be used by an opposing party to argue for a narrow interpretation of the claims, thereby allowing them to escape infringement.40 Drafters must be vigilant in avoiding language that unnecessarily limits the invention.

Examples of patent profanity include absolute terms like “must,” “necessary,” “essential,” “always,” “never,” and “only”.40 Describing a particular feature as “critical” or “the key” to the invention can lead a court to interpret that feature as a mandatory element of all claims, even if it is not explicitly recited in them. Instead of stating “the invention is…,” which can be limiting, it is far better to use phrases like “in one embodiment, the composition comprises…” or “in some implementations, the method can include…”.35 This language preserves flexibility and makes it clear that the described examples are merely illustrative and not exhaustive, thereby supporting the broadest reasonable interpretation of the claims.

Section IV: Mastering the Claim: Forging the Legal Boundaries of the Monopoly

The claims are the most critical part of the patent application. As stated by the esteemed patent jurist Judge Giles S. Rich, “the name of the game is the claim”.49 They are the legally operative sentences that define the precise boundaries of the inventor’s exclusive rights.36 The specification teaches what the invention is, but the claims define what the patent owner

owns. Every word in a claim is a potential point of litigation, and their construction is often the outcome-determinative issue in patent disputes.50 Therefore, drafting claims is an exercise in strategic precision, balancing the desire for broad protection against the need for validity in the face of prior art and disclosure requirements.

4.1 Anatomy of a Claim: Preamble, Transitional Phrase, and Body

A patent claim is typically structured into three distinct parts, each with a specific function 8:

- The Preamble: This introductory phrase sets the general class and context for the invention. Examples in the pharmaceutical context include: “A pharmaceutical composition…”, “A compound of formula I…”, or “A method for treating cancer…”.8 While often seen as a simple introduction, the preamble can, in certain circumstances, be interpreted as a limitation on the scope of the claim.39

- The Transitional Phrase: This is a critical term or phrase that links the preamble to the body of the claim and defines the scope of the elements that follow. The choice of this phrase is one of the most important strategic decisions in claim drafting.8

- The Body: This section positively recites the essential elements, components, or steps that constitute the invention. It is the detailed list of what the invention is.

4.2 The Power of a Single Word: Strategic Use of “Comprising” vs. “Consisting Of”

The choice of transitional phrase can dramatically alter the scope of a claim.8 The two most common phrases in pharmaceutical patenting have very different legal meanings:

- “Comprising” (Open-ended): This is the most frequently used and strategically preferred transitional phrase in U.S. patent practice.8 It is interpreted as “including, but not limited to.” A claim reciting a composition “comprising A, B, and C” would be infringed by a product that contains A, B, and C, even if it also contains additional, unrecited elements like D and E.21 This open-ended language provides the broadest possible scope of protection and makes it more difficult for competitors to design around the patent by simply adding another component.

- “Consisting of” (Closed-ended): This is the most restrictive transitional phrase.8 It is interpreted to mean that the invention includes

only the elements explicitly listed in the body of the claim and nothing more.39 A claim to a composition “consisting of A, B, and C” would

not be infringed by a product containing A, B, C, and D. While this severely narrows the claim’s scope, it can be a valuable strategic tool to overcome a rejection based on prior art that discloses a more complex mixture. By using “consisting of,” the applicant can carve out a novel and patentable invention from a broader, known composition.

4.3 Claiming Strategies: From Narrow “Species” to Broad “Genus” Claims

A well-drafted patent application does not contain a single claim, but rather a strategic hierarchy of claims with varying scopes. This approach provides multiple fallback positions that are crucial during prosecution and litigation.8

- Genus Claims: These are broad claims that cover an entire family of related compounds, formulations, or methods. The goal of a genus claim is to protect not just a single discovered molecule but all related, functionally equivalent molecules, thereby preventing competitors from making minor, trivial modifications to circumvent the patent.8 These claims offer the greatest market protection but also face the highest level of scrutiny for meeting the written description and enablement requirements of § 112.

- Species Claims: These are the most specific type of claims, directed to a single, precisely defined chemical compound, a specific formulation with exact component ratios, or a highly detailed method.8 Because they are narrow, species claims are often easier to get allowed by a patent office and are more difficult to invalidate. However, they are also easier for competitors to design around.

A robust application will include one or more broad genus claims followed by a series of narrower sub-genus and species claims. This creates a defensive depth; if the broad genus claim is later invalidated by a court, the narrower, more specific species claims may survive and still provide valuable protection.

4.4 Advanced Technique: Drafting and Supporting Markush Claims

In chemistry and pharmaceuticals, the most common format for a genus claim is the Markush claim.4 Named after the inventor in a 1925 patent case, a Markush claim is a unique linguistic tool that allows a drafter to define a genus of chemical compounds by reciting a list of alternatively usable members.45

The typical format involves a core chemical structure (a scaffold) with one or more variable positions designated by placeholders like R1, R2, etc. The claim then defines the possible substituents for each variable position using the characteristic phrase “wherein R1 is selected from the group consisting of A, B, and C”.45 This allows the applicant to claim a vast number of potential compounds within a single claim.

To be valid under USPTO rules, the members of a Markush group must share two key characteristics: (1) a “single structural similarity” (i.e., they belong to a recognized physical or chemical class) and (2) a “common use” (i.e., they are functionally equivalent in the context of the invention).53 The specification must provide adequate disclosure to support the inclusion of all members in the group, demonstrating to a PHOSITA that the inventor possessed and enabled the full scope of the claimed genus.46

4.5 Layering the Defense: Interplay Between Independent and Dependent Claims

Claims are also categorized as either independent or dependent, and their interplay is a fundamental aspect of claim strategy.

- Independent Claim: An independent claim stands on its own and does not refer back to any other claim. It typically defines the broadest scope of the invention sought by the applicant. An application can have multiple independent claims directed to different aspects of the invention (e.g., an independent claim for the compound, another for the formulation, and a third for the method of use).

- Dependent Claim: A dependent claim always refers back to and incorporates all the limitations of a preceding claim (either an independent claim or another dependent claim) and adds at least one further, narrowing limitation.55 For example:

- (Independent) A pharmaceutical composition comprising compound X and a carrier.

- (Dependent) The composition of claim 1, wherein the carrier is a cyclodextrin.

- (Dependent) The composition of claim 2, wherein the composition is formulated as an oral tablet.

Drafting a cascading series of dependent claims is a crucial defensive strategy. Each dependent claim represents a narrower, pre-defined fallback position. If the broader independent claim is found to be invalid over the prior art during prosecution or litigation, the narrower dependent claims, which include additional limitations not found in the prior art, may still be valid and enforceable.55

Section V: Global Filing and Prosecution Strategy

In the globalized pharmaceutical market, an effective patent strategy must extend beyond national borders. Securing robust intellectual property rights in key commercial jurisdictions requires a forward-looking approach that leverages international treaties and navigates the nuanced differences between major patent offices.

5.1 The First Step: Provisional Applications as a Strategic Placeholder

For many innovators, particularly in the fast-moving U.S. market, the patenting journey begins with a provisional patent application. This is not a formal patent application that gets examined, but rather a strategic tool that establishes an early priority date for the invention.2 In the “first-inventor-to-file” system that governs the U.S. and most of the world, securing the earliest possible filing date is paramount to prevent a competitor from patenting the same or a similar invention first.2

A provisional application is less formal and less expensive to file than a full non-provisional application. It provides the applicant with a 12-month window to continue research, gather more data, secure funding, and assess the commercial potential of the invention before committing to the significant expense of filing a full application.2 As long as the non-provisional application is filed within that 12-month period and claims priority to the provisional, it is treated as if it were filed on the provisional’s earlier date.

5.2 Navigating the World: The Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) and National Phase Entry

To seek patent protection in multiple countries, the most efficient initial step is to file an international application under the Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT).9 Administered by the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), the PCT is an international treaty with over 155 contracting states.59 It is crucial to understand that the PCT system does not grant an “international patent”—no such thing exists.60 Instead, it provides a unified and streamlined

filing procedure.61

By filing a single PCT application in one language at one receiving office, an applicant effectively files in all 158 member countries simultaneously.58 The PCT process consists of two main phases:

- The International Phase: During this phase, which typically lasts up to 30 or 31 months from the priority date, the application is subjected to an international search by an International Searching Authority (ISA), which identifies relevant prior art and provides a written opinion on the potential patentability of the invention.57 This provides valuable feedback early in the process.

- The National Phase: Before the end of the international phase, the applicant must “enter the national phase” in each individual country or region where they wish to obtain a patent.57 This involves paying national fees, submitting translations, and meeting local formal requirements. The application is then examined by each national patent office according to its own laws.59

The primary strategic advantage of the PCT is that it delays the substantial costs associated with filing numerous separate national applications, giving the applicant more time to assess the invention’s value and decide where to seek protection.60

5.3 Comparative Analysis: Key Differences in Patentability Standards (U.S., Europe, Japan)

While the core patentability principles of novelty, inventive step/non-obviousness, and utility/industrial applicability are harmonized to some extent, significant jurisdictional differences remain that can dictate the success or failure of a global patent strategy. A claim that is allowable in one jurisdiction may be rejected in another.

- Patentable Subject Matter: This is an area of major divergence.

- Methods of Treatment: The U.S. allows direct claims to methods of treating humans (e.g., “A method of treating Alzheimer’s disease, comprising administering compound X to a patient in need thereof”).62 In contrast, the European Patent Convention (EPC) explicitly prohibits patenting methods for treatment of the human body by therapy.48 To circumvent this, the European Patent Office (EPO) allows “purpose-limited product claims,” such as “Compound X for use in a method of treating Alzheimer’s disease”.62 While linguistically different, this format achieves a similar protective effect. Japan is more aligned with the U.S. and allows product patents for new medical uses.64

- Diagnostic Methods: Following the Supreme Court’s decision in Mayo v. Prometheus, obtaining patents on diagnostic methods in the U.S. has become exceedingly difficult, as they are often deemed to be unpatentable laws of nature.65 Both Europe and Japan have a more permissive stance, allowing patents on diagnostic methods, particularly those performed

in vitro on samples taken from the body.63 - Products of Nature: The U.S. Supreme Court’s Myriad decision held that isolated natural DNA is an unpatentable product of nature, creating a higher bar for patenting naturally derived compounds than in Europe or Japan, where isolated natural products are generally considered patentable.66

- Inventive Step / Non-Obviousness: The EPO employs a highly structured “problem-solution approach” to assess inventive step, which involves identifying the closest prior art, determining the technical problem solved by the invention, and then considering whether the claimed solution would have been obvious.56 The U.S. approach to non-obviousness is more flexible and holistic, based on the factors laid out in

Graham v. John Deere and the framework from KSR v. Teleflex.29 - Disclosure Requirements: The EPO is notoriously strict regarding its “added matter” doctrine under Article 123(2) EPC. An applicant cannot amend an application after filing to include subject matter that is not directly and unambiguously derivable from the application as filed.67 This places an immense premium on drafting a comprehensive and detailed initial application for European prosecution. The U.S. has a more lenient standard for amending claims based on the overall disclosure.

| Table 2: Jurisdictional Comparison of Patentability Requirements (U.S. vs. Europe vs. Japan) | |||

| Criterion | United States (USPTO) | Europe (EPO) | Japan (JPO) |

| Methods of Treatment | Patentable as direct method claims. | Not patentable. Protection is achieved via “purpose-limited product claims” (e.g., “Compound for use in…”). | Patentable as “medical use” inventions, which are treated as product claims. |

| Diagnostic Methods | Very difficult to patent post-Mayo; often rejected as unpatentable laws of nature. | Patentable if technical and not practiced directly on the human body (e.g., in vitro tests). | Generally patentable and considered industrially applicable. |

| Isolated Natural Products | Difficult to patent post-Myriad; must be “markedly different” from what exists in nature. | Generally patentable if isolated from their natural environment. | Generally patentable if isolated by man from nature. |

| Inventive Step / Non-Obviousness Standard | Flexible, holistic analysis based on Graham factors and KSR framework. | Highly structured “problem-solution approach.” | Similar to Europe, focuses on whether a PHOSITA could easily arrive at the invention based on prior art. |

| Disclosure Requirements | Requires written description and enablement; amendments must be supported by the original disclosure. | Very strict “added matter” doctrine; amendments must be directly and unambiguously derivable from the application as filed. | Strict requirement for enablement; working examples are highly important to support the claimed effect. |

5.4 Prosecution as Negotiation: Responding to Office Actions and Overcoming Common Rejections

Securing a patent is not a passive process; it is an active, iterative negotiation with a patent examiner, known as prosecution. After filing, an examiner will review the application and issue an “Office Action” detailing any rejections based on the patentability standards.30 The most frequent grounds for rejection are lack of novelty (§ 102) and, especially, obviousness (§ 103).29

Successfully navigating prosecution requires a multi-faceted strategy:

- Argumentation: The applicant’s attorney can submit written arguments explaining why the examiner’s interpretation of the prior art is incorrect or why the claimed invention is, in fact, novel and non-obvious.29

- Claim Amendments: Often, the most effective path to allowance is to amend the claims to narrow their scope, adding limitations that distinguish the invention from the prior art cited by the examiner.29 This is where a well-drafted application with a hierarchy of dependent claims becomes invaluable, as these provide pre-written fallback positions.

- Submission of Evidence: To overcome an obviousness rejection, the applicant can submit a declaration or affidavit with new evidence, such as data from comparative tests showing unexpected results or evidence of commercial success.29

- Examiner Interviews: A direct conversation with the examiner can often be the most efficient way to resolve misunderstandings, clarify the invention’s key features, and collaboratively identify a path to allowable subject matter.29

Section VI: Defending the Fortress: Post-Grant Strategy and Competitive Intelligence

Obtaining a granted patent is not the end of the journey; it is the beginning of the next phase of strategic management. A patent’s value is only realized if it can be successfully defended against challenges and leveraged to maintain market exclusivity. This requires constant vigilance, pre-launch diligence, and a deep understanding of the post-grant landscape.

6.1 Pre-Launch Diligence: The Critical Role of Freedom-to-Operate (FTO) Analysis

Before investing hundreds of millions of dollars in late-stage clinical trials and commercial launch activities, a pharmaceutical company must conduct a thorough Freedom-to-Operate (FTO) analysis. An FTO is a core strategic imperative that seeks to determine whether a planned commercial product or process is likely to infringe the valid and enforceable patent rights of a third party in a specific country.34

An FTO analysis is fundamentally a risk-mitigation tool. It involves a meticulous search and analysis of the patent landscape to identify potentially blocking patents.34 Conducting this analysis early in the development cycle is critical, as it affords the company time to pursue strategic options if a risk is identified, such as:

- Designing around the blocking patent by modifying the product or process.

- Negotiating a license with the patent holder.

- Challenging the validity of the blocking patent.

- Abandoning the project before incurring further significant costs.

Beyond risk mitigation, an FTO analysis is an invaluable competitive intelligence exercise, providing deep insights into the R&D activities and patent strategies of rivals.70 Furthermore, obtaining a formal, written FTO opinion from qualified patent counsel can serve as a crucial defense against allegations of “willful infringement” in potential litigation, which can lead to a tripling of monetary damages.70

6.2 Navigating Post-Grant Challenges: Strategic Considerations for IPR and PGR

The America Invents Act of 2011 (AIA) fundamentally reshaped the U.S. patent landscape by creating administrative trial proceedings at the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB). These proceedings, Inter Partes Review (IPR) and Post-Grant Review (PGR), offer a faster and less expensive alternative to district court litigation for challenging the validity of an issued patent.72 For generic and biosimilar manufacturers, they are a powerful tool for clearing a path to market. For innovator companies, they represent a significant and constant threat to their most valuable assets.

| Table 3: Post-Grant Challenge Mechanisms: IPR vs. PGR | ||

| Feature | Inter Partes Review (IPR) | Post-Grant Review (PGR) |

| Timing for Filing | Can be filed 9 months after patent grant or after a PGR concludes. | Must be filed within 9 months of patent grant. |

| Available Grounds for Challenge | Narrow: Only novelty (§ 102) and obviousness (§ 103) based on prior art patents and printed publications. | Broad: Any ground for invalidity, including § 101 (subject matter eligibility), § 112 (written description, enablement, indefiniteness), as well as § 102 and § 103. |

| Standard for Institution | “Reasonable likelihood” that the petitioner will prevail on at least one challenged claim. | “More likely than not” that at least one challenged claim is unpatentable. |

| Strategic Considerations for Pharma | The primary tool for challenging patents after the 9-month PGR window has closed. Used extensively by generic companies to challenge patents listed in the Orange Book. | A critical, time-limited opportunity to challenge a patent on the broadest possible grounds. Particularly powerful against broad biologic claims that may be vulnerable to § 112 enablement challenges post-Amgen. |

For patent holders, a successful defense strategy requires a deep understanding of PTAB procedures, including the stringent rules for submitting evidence and the limited opportunities to amend claims.75 For challengers, a meticulously prepared petition that clearly and concisely lays out the grounds for invalidity, supported by expert declarations, is essential for convincing the PTAB to institute a trial.75

6.3 The Patent Thicket: An Offensive and Defensive Strategy for Market Dominance

A “patent thicket” is a strategic, dense web of numerous, often overlapping patents covering various aspects of a single drug product.3 This strategy goes far beyond protecting the core API. It involves systematically filing and obtaining secondary patents on formulations, manufacturing processes, methods of use, dosage forms, and even delivery devices.77 The objective is to create such a complex, costly, and formidable litigation landscape that would-be generic or biosimilar competitors are deterred from entering the market, thereby extending the drug’s effective monopoly for years beyond the expiration of the original composition of matter patent.3

Case Study – Humira (AbbVie): The quintessential example of a successful patent thicket strategy is AbbVie’s protection of its blockbuster drug, Humira. AbbVie built a fortress of over 247 patent applications, resulting in more than 132 granted patents in the U.S. alone.77 While the primary patent on the adalimumab molecule expired in 2016, this dense thicket of secondary patents successfully delayed the launch of biosimilar competitors in the U.S. until 2023.67 This extended monopoly allowed Humira to generate staggering revenues, reportedly as high as $47.5 million per day, and is estimated to have cost the U.S. healthcare system tens of billions of dollars in higher drug prices compared to Europe, where the patent thicket was far less dense and biosimilars entered much earlier.67 The Humira case study is a powerful illustration of how a sophisticated, multi-layered patenting strategy can translate directly into enduring market dominance and immense financial returns.

6.4 The End Game: The Hatch-Waxman Act and the Inevitable Patent Cliff

The final phase of a drug’s patented life is governed by the complex interplay of the Hatch-Waxman Act.17 This landmark legislation created the modern abbreviated pathway for generic drug approval. It allows a generic manufacturer to file an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) that relies on the innovator’s safety and efficacy data, proving only that its product is bioequivalent.85

As part of the ANDA filing, the generic company must make a certification regarding the innovator’s patents listed in the FDA’s Orange Book. A “Paragraph IV certification” asserts that the innovator’s patent is invalid, unenforceable, or will not be infringed by the generic product.84 This filing is an act of patent infringement and typically triggers a lawsuit from the patent holder. To incentivize these challenges, which can invalidate weak patents and accelerate generic entry, the Act grants a

180-day period of market exclusivity to the first generic applicant to file a successful Paragraph IV certification.17

This framework orchestrates the end-game of a drug’s lifecycle, leading to what is known as the “patent cliff.” Upon the expiration of the last patent or the resolution of litigation and the entry of the first generic competitor, the innovator’s revenues for that product can plummet by as much as 80-90% almost immediately as lower-priced generics capture the market.3 Understanding and preparing for this inevitable cliff through lifecycle management and the development of new products is a central component of long-term pharmaceutical business strategy.

Conclusion: Integrating Science, Law, and Commerce for Enduring Market Power

The process of drafting and defending a pharmaceutical patent is a sophisticated exercise in translating scientific discovery into durable market power. It is an endeavor where legal precision, scientific rigor, and commercial foresight must converge. An effective patent application is not merely a record of an invention; it is a strategic asset meticulously crafted to secure investment, withstand adversarial challenges, and maximize commercial returns in a fiercely competitive global market.

The analysis reveals several core principles that are imperative for success. First is the adoption of a claims-first drafting approach, where the desired legal scope of protection dictates the content of the specification, not the other way around. This ensures that the application is purpose-built to support its most critical components. Second is the unwavering commitment to a data-rich specification. In an era of heightened judicial scrutiny of disclosure requirements, particularly following the Amgen v. Sanofi decision, the ability to support broad claims with comprehensive working and prophetic examples is non-negotiable. Third is the strategic layering of multiple patent types—from composition of matter to formulation and method of use—to construct a formidable “patent thicket” that is difficult for competitors to penetrate. Finally, a successful strategy must be proactive and global, integrating early filing tactics, navigating key jurisdictional differences, and preparing for post-grant challenges from the moment of invention.

Looking ahead, the landscape of pharmaceutical IP continues to evolve. The advent of artificial intelligence in drug discovery promises to accelerate innovation but will also introduce new challenges in defining inventorship and patentability.9 Concurrently, there is growing political and judicial pressure in the United States and elsewhere to curb perceived abuses of the patent system, such as aggressive “evergreening” and the construction of patent thickets that unduly delay generic competition.77 This underscores the persistent and fundamental tension at the heart of the patent system: the need to provide powerful incentives to reward the immense risk and cost of innovation, balanced against the pressing societal imperative to ensure broad and affordable access to life-saving medicines.2 For the innovators of tomorrow, navigating this complex and dynamic environment will require not only groundbreaking science but also an ever-more sophisticated and integrated approach to intellectual property strategy. The innovator’s fortress must be built with foresight, precision, and an unyielding focus on the ultimate goal: turning science into enduring market power for the benefit of both the company and the patients it serves.

Works cited

- Optimizing Your Drug Patent Strategy: A Comprehensive Guide for …, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/optimizing-your-drug-patent-strategy-a-comprehensive-guide-for-pharmaceutical-companies/

- Filing Strategies for Maximizing Pharma Patents: A Comprehensive Guide for Business Professionals – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/filing-strategies-for-maximizing-pharma-patents/

- Patent Defense Isn’t a Legal Problem. It’s a Strategy Problem. Patent Defense Tactics That Every Pharma Company Needs – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/patent-defense-isnt-a-legal-problem-its-a-strategy-problem-patent-defense-tactics-that-every-pharma-company-needs/

- What are the types of pharmaceutical patents? – Patsnap Synapse, accessed August 5, 2025, https://synapse.patsnap.com/blog/what-are-the-types-of-pharmaceutical-patents

- Patent protection strategies – PMC, accessed August 5, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3146086/

- The Role of Patents in the Pharmaceutical Sector – Minesoft, accessed August 5, 2025, https://minesoft.com/the-role-of-patents-in-the-pharmaceutical-sector/

- Securing Innovation: A Comprehensive Guide to Drafting and Prosecuting Patent Applications for Biologic Drugs – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/drafting-drug-patent-applications-for-biologic-drugs/

- Drafting Detailed Drug Patent Claims: The Art and Science of …, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/drafting-detailed-drug-patent-claims-the-art-and-science-of-pharmaceutical-ip-protection/

- How to Draft Strong Patent Claims for Drug Inventions | PatentPC, accessed August 5, 2025, https://patentpc.com/blog/how-to-draft-strong-patent-claims-drug-inventions

- Patent protection as a key driver for pharmaceutical innovation | IFPMA, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.ifpma.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/i2023_5.-Patent-Protection-as-a-Key-Driver-for-Pharmaceutical-Innovation.pdf

- Drug development cost pharma $2.2B per asset in 2024 as GLP-1s drive financial return, accessed August 5, 2025, https://tentelemed.com/drug-development-cost-pharma-2-2b-per-asset-in-2024-as-glp-1s-drive-financial-return/

- Measuring the return from pharmaceutical innovation 2024 | Deloitte …, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.deloitte.com/us/en/Industries/life-sciences-health-care/articles/measuring-return-from-pharmaceutical-innovation.html

- Describing Written Description: the Implications ofAriad, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.venable.com/-/media/files/publications/2010/06/theimplicationsofariad.pdf

- Costs of Drug Development and Research and Development Intensity in the US, 2000-2018, accessed August 5, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11214120/

- Top 10 pharma R&D budgets in 2024 – Fierce Biotech, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.fiercebiotech.com/special-reports/top-10-pharma-rd-budgets-2024

- Research and development (R&D) investment by the biopharmaceutical industry: A global ecosystem update – ISPOR, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.ispor.org/docs/default-source/intl2024/j-j-access-policy-research—ispor-2024—pharma-r-d-ecosystem-investment137860-pdf.pdf?sfvrsn=d28181d4_0

- When Do Drug Patents Expire: Understanding the Lifecycle of …, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/when-do-drug-patents-expire/

- Drug Patent Life: The Complete Guide to Pharmaceutical Patent Duration and Market Exclusivity – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/how-long-do-drug-patents-last/

- When does a drug patent expire? – Patsnap Synapse, accessed August 5, 2025, https://synapse.patsnap.com/article/when-does-a-drug-patent-expire

- How Drug Life-Cycle Management Patent Strategies May Impact Formulary Management, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.ajmc.com/view/a636-article

- The Evolution of Patent Claims in Drug Lifecycle Management – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-evolution-of-patent-claims-in-drug-lifecycle-management/

- Patents, Innovation, and Competition in Pharmaceuticals: The Hatch …, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/jep.20241423

- Composition of Matter Patents – (Intro to Pharmacology) – Vocab, Definition, Explanations, accessed August 5, 2025, https://library.fiveable.me/key-terms/introduction-to-pharmacology/composition-of-matter-patents

- Composition of matter – Wikipedia, accessed August 5, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Composition_of_matter

- Types of Pharmaceutical Patents – O’Brien Patents, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.obrienpatents.com/types-pharmaceutical-patents/

- A Quick Guide to Pharmaceutical Patents and Their Types – PatSeer, accessed August 5, 2025, https://patseer.com/a-quick-guide-to-pharmaceutical-patents-and-their-types/

- Frequently Asked Questions on Patents and Exclusivity – FDA, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/development-approval-process-drugs/frequently-asked-questions-patents-and-exclusivity

- Patent essentials | USPTO, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.uspto.gov/patents/basics/essentials

- Common Reasons for Drug Patent Rejections and Solutions …, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/common-reasons-for-drug-patent-rejections-and-solutions/

- Mastering First-Time Patent Rejections: Your In-Depth Guide – TT Consultants, accessed August 5, 2025, https://ttconsultants.com/how-to-handle-your-first-patent-rejection/

- Written Description – The Invention Must be Fully Described – Sierra IP Law, PC, accessed August 5, 2025, https://sierraiplaw.com/written-description/

- 2164-The Enablement Requirement – USPTO, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.uspto.gov/web/offices/pac/mpep/s2164.html

- Use of prophetic examples in patent specifications – Spruson & Ferguson, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.spruson.com/use-of-prophetic-examples-in-patent-specifications/

- IP: Writing a Freedom to Operate Analysis – InterSECT Job Simulations, accessed August 5, 2025, https://intersectjobsims.com/library/fto-analysis/

- WIPO Patent Drafting Manual_Second Edition, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.wipo.int/edocs/pubdocs/en/wipo-pub-867-23-en-wipo-patent-drafting-manual.pdf

- Pharmaceutical Patents: an overview, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.alacrita.com/blog/pharmaceutical-patents-an-overview

- Learn how to draft a patent application – USPTO, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.uspto.gov/sites/default/files/documents/P2AP_PartIV_Learnhowtodraftapatentapplication_Final_0.pdf

- How to Write a Detailed Description in a Patent Application – PatentPC, accessed August 5, 2025, https://patentpc.com/blog/how-to-write-a-detailed-description-in-a-patent-application

- Patent Claim Construction, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.venable.com/-/media/files/publications/2013/06/patent-claim-construction.pdf?rev=fab9341f2cd74e398a289dcb43d80686&hash=3B5EC0A0DF9096DEBA198B969DB1E165

- Practical Considerations and Strategies in Drafting U.S. Patent Applications – Finnegan, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.finnegan.com/en/insights/articles/practical-considerations-and-strategies-in-drafting-u-s-patent.html

- Patent Drafting Basics: Instruction Manual Detail is What You Seek – IPWatchdog.com, accessed August 5, 2025, https://ipwatchdog.com/2018/10/20/patent-drafting-basics-instruction-manual-detail/id=102519/

- Working vs Prophetic Examples in Patents – BlueIron IP, accessed August 5, 2025, https://blueironip.com/ufaqs/what-is-the-difference-between-working-examples-and-prophetic-examples-in-patent-applications/

- MPEP 2164.02: Working and Prophetic Examples, November 2024 (BitLaw), accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.bitlaw.com/source/mpep/2164-02.html

- Prophetic Patents – UC Davis Law Review, accessed August 5, 2025, https://lawreview.law.ucdavis.edu/sites/g/files/dgvnsk15026/files/media/documents/53-2_Freilich.pdf

- What is the format for Markush claims? – Patsnap Synapse, accessed August 5, 2025, https://synapse.patsnap.com/article/what-is-the-format-for-markush-claims

- Understanding Markush Structure in Patents – Collier Legal, accessed August 5, 2025, https://collierlegaloh.com/understanding-markush-structure-in-patents/

- Strategies for Protecting Formulation Patents in Pharmaceuticals – PatentPC, accessed August 5, 2025, https://patentpc.com/blog/strategies-protecting-formulation-patents-in-pharmaceuticals

- 13 The Patentability and Scope of Protection of Pharmaceutical Inventions Claiming Second Medical Use – the Japanese and Euro, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.iip.or.jp/e/summary/pdf/detail2007/e19_13.pdf

- Quotes on Patent Lawyers – Compiled by Homer Blair – IP Mall – University of New Hampshire, accessed August 5, 2025, https://ipmall.law.unh.edu/content/quotes-patent-lawyers-compiled-homer-blair

- Mastering Patent Claim Construction: A Patent Special Master’s Perspective – Digital Commons @ Touro Law Center, accessed August 5, 2025, https://digitalcommons.tourolaw.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2544&context=lawreview

- Markush Madness: Watson Avoids Infringement by Adding an Element to a Formulation, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.klgates.com/Markush-Madness-Watson-Avoids-Infringement-by-Adding-an-Element-to-a-Formulation-04-04-2017

- Navigating Markush Claims in Patent Ethics – Number Analytics, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.numberanalytics.com/blog/ultimate-guide-markush-claims-patent-ethics

- 2117-Markush Claims – USPTO, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.uspto.gov/web/offices/pac/mpep/s2117.html

- What is a Markush Group in Patent Claims? – BlueIron IP, accessed August 5, 2025, https://blueironip.com/ufaqs/what-is-a-markush-group-in-patent-claims/

- WO2001045636A1 – Pharmaceutical kit – Google Patents, accessed August 5, 2025, https://patents.google.com/patent/WO2001045636A1/en

- 10 Key Differences Between U.S. and European Patent Systems – PatentPC, accessed August 5, 2025, https://patentpc.com/blog/10-key-differences-between-u-s-and-european-patent-systems

- File an international patent application through the Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT), accessed August 5, 2025, https://ised-isde.canada.ca/site/canadian-intellectual-property-office/en/patents/patent-application-and-examination/file-international-patent-application-through-patent-cooperation-treaty-pct-patent-cooperation

- PCT – The International Patent System – WIPO, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.wipo.int/en/web/pct-system

- Protecting your Inventions Abroad: Frequently Asked Questions About the Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) – WIPO, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.wipo.int/en/web/pct-system/faqs/faqs

- International (PCT) Patent Applications – The Basics – Mewburn Ellis, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.mewburn.com/law-practice-library/international-pct-patent-applications-the-basics

- Patent Cooperation Treaty – Wikipedia, accessed August 5, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Patent_Cooperation_Treaty

- Patenting medical treatments in the US and Europe – a guide for …, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.managingip.com/article/2dw7os2qp6q4s8x5ghssg/patents/patenting-medical-treatments-in-the-us-and-europe-a-guide-for-practitioners

- The State of Patentable Subject Matter Internationally – Sterne Kessler, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.sternekessler.com/news-insights/insights/state-patentable-subject-matter-internationally/

- The Patent and Non-Patent Incentives for Research and Development of New Uses of Known Pharmaceuticals in Japan, accessed August 5, 2025, https://digitalcommons.law.uw.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1262&context=wjlta

- Biotech Patent Protection: US vs Europe vs Asia Key Differences – Patsnap Synapse, accessed August 5, 2025, https://synapse.patsnap.com/article/biotech-patent-protection-us-vs-europe-vs-asia-key-differences

- The Benefits of Japanese Patent Law System Over those of the US …, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.jpaa.or.jp/discoveripjapan/pdf/Plenary_Session.pdf

- The Global Patent Thicket: A Comparative Analysis of Pharmaceutical Monopoly Strategies in the U.S., Europe, and Emerging Markets – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/how-do-patent-thickets-vary-across-different-countries/

- 706-Rejection of Claims – USPTO, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.uspto.gov/web/offices/pac/mpep/s706.html

- When Is a “Freedom to Operate” Opinion Cost-Effective? | Articles – Finnegan, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.finnegan.com/en/insights/articles/when-is-a-freedom-to-operate-opinion-cost-effective.html

- How to Conduct a Drug Patent FTO Search: A Strategic and Tactical …, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/how-to-conduct-a-drug-patent-fto-search/

- How to Conduct a Freedom-to-Operate Analysis for a Drug Repurposing Project, accessed August 5, 2025, https://drugrepocentral.scienceopen.com/hosted-document?doi=10.58647/DRUGREPO.24.1.0011

- Post-Grant Proceedings – Patent Docs, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.patentdocs.org/post-grant-proceedings/

- The Rise of Post-Grant Proceedings – PMC, accessed August 5, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5238482/

- “Post-Grant Adjudication of Drug Patents: Agency and/or Court?” by Arti k. Rai, Saurabh Vishnubhakat et al. – Duke Law Scholarship Repository, accessed August 5, 2025, https://scholarship.law.duke.edu/faculty_scholarship/4239/

- Mastering Post-Grant Review in Patent Litigation – Number Analytics, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.numberanalytics.com/blog/mastering-post-grant-review-patent-litigation

- Strategies for Patent Invalidation through PGR and IPR, accessed August 5, 2025, https://ttconsultants.com/post-grant-review-pgr-and-inter-partes-review-ipr-strategies-for-patent-invalidation/

- The Dark Reality of Drug Patent Thickets: Innovation or Exploitation …, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-dark-reality-of-drug-patent-thickets-innovation-or-exploitation/

- Drug Pricing and Pharmaceutical Patenting Practices – EveryCRSReport.com, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.everycrsreport.com/reports/R46221.html

- In the case of brand name drugs versus generics, patents can be bad medicine, WVU law professor says, accessed August 5, 2025, https://wvutoday.wvu.edu/stories/2022/12/19/in-the-case-of-brand-name-drugs-vs-generics-patents-can-be-bad-medicine-wvu-law-professor-says

- FACT SHEET: BIG PHARMA’S PATENT ABUSE COSTS AMERICAN PATIENTS, TAXPAYERS AND THE U.S. HEALTH CARE SYSTEM BILLIONS OF DOLLARS – CSRxP.org, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.csrxp.org/fact-sheet-big-pharmas-patent-abuse-costs-american-patients-taxpayers-and-the-u-s-health-care-system-billions-of-dollars-2/

- The Hatch-Waxman Act: A Quarter Century Later – UM Carey Law, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www2.law.umaryland.edu/marshall/crsreports/crsdocuments/R41114_03132013.pdf

- Abuse of the Hatch-Waxman Act: Mylan’s Ability to Monopolize Reflects Weaknesses – BrooklynWorks, accessed August 5, 2025, https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1241&context=bjcfcl

- 40 Years of Hatch-Waxman: What is the Hatch-Waxman Act? | PhRMA, accessed August 5, 2025, https://phrma.org/blog/40-years-of-hatch-waxman-what-is-the-hatch-waxman-act

- Small Business Assistance | 180-Day Generic Drug Exclusivity | FDA, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/cder-small-business-industry-assistance-sbia/small-business-assistance-180-day-generic-drug-exclusivity

- Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act – Wikipedia, accessed August 5, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Drug_Price_Competition_and_Patent_Term_Restoration_Act

- The Hatch-Waxman Act: A Primer – EveryCRSReport.com, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.everycrsreport.com/reports/R44643.html

- Earning Exclusivity: Generic Drug Incentives and the Hatch-‐Waxman Act1 C. Scott – Stanford Law School, accessed August 5, 2025, https://law.stanford.edu/index.php?webauth-document=publication/259458/doc/slspublic/ssrn-id1736822.pdf

- Insights | Patent Prosecution | Marshall, Gerstein & Borun LLP, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.marshallip.com/patent-prosecution/insights/

- Does Pharma Need Patents? – The Yale Law Journal, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.yalelawjournal.org/feature/does-pharma-need-patents

- NEW DAWN FOR LIFE SCIENCES IP STRATEGY, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.dechert.com/content/dam/dechert%20files/people/bios/h/katherine-a–helm/IAM-Special-Report-New-Dawn-for-Life-Sciences-IP-Strategy.pdf

- STAT quotes Sherkow on pharmaceutical patents – College of Law, accessed August 5, 2025, https://law.illinois.edu/stat-quotes-sherkow-on-pharmaceutical-patents/