Executive Summary

The generic drug market stands as a cornerstone of modern healthcare systems, delivering immense value through increased patient access and substantial cost savings. In the United States alone, generic medicines account for nearly nine out of every ten prescriptions filled yet constitute just over a quarter of total drug expenditures, saving the healthcare system hundreds of billions of dollars annually. Globally, this multi-hundred-billion-dollar market is poised for continued growth, fueled by a historic wave of patent expirations for blockbuster drugs. However, this report argues that the foundational economic model of the generic drug industry is fundamentally broken, caught in a paradox where its greatest strength—the ability to drive down prices through intense competition—has become its greatest vulnerability.

The market is plagued by a series of interconnected challenges that threaten its long-term stability and, by extension, the reliability of the medicine supply. An unrelenting “race to the bottom” on pricing, driven by powerful consolidated buyers like Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs) and Group Purchasing Organizations (GPOs), has compressed manufacturer margins to unsustainable levels. This economic pressure has forced thousands of products off the market, disincentivized investment in quality and resilience, and pushed manufacturing to a few hyper-concentrated overseas locations, primarily India and China. The result is a fragile, brittle global supply chain, acutely vulnerable to geopolitical shocks, quality failures, and trade disruptions. This fragility manifests in the most damaging way possible: a persistent and worsening crisis of drug shortages that directly harms patients and imposes massive secondary costs on the healthcare system.

This report provides a comprehensive analysis of these systemic frailties. It dissects the economic pressures, maps the vulnerabilities of the global supply chain, examines the distorting influence of market intermediaries, and assesses the complex regulatory landscape. The central finding is that the market has systematically failed to price in the value of reliability. The relentless pursuit of the lowest possible unit cost has come at the expense of supply chain security, creating a system that is efficient at producing low prices but dangerously inefficient at ensuring consistent supply.

To address this fundamental market failure, this report proposes an integrated strategic framework aimed at fostering a more stable, resilient, and affordable generic drug ecosystem. The recommendations are organized around three core pillars: policy and market reform, supply chain fortification, and technological innovation. Key strategies include reforming PBM and GPO practices to enhance transparency and align incentives, implementing policies that economically reward manufacturing resilience, pursuing a targeted strategy of supply chain diversification through onshoring and “friend-shoring,” enhancing the role of the Strategic National Stockpile, and accelerating the adoption of advanced manufacturing and artificial intelligence. Ultimately, a sustainable solution requires a portfolio of policies that realign incentives across the entire value chain, moving from a myopic focus on price to a more holistic valuation that includes the critical importance of a reliable and secure supply of essential medicines.

I. The Paradox of the Modern Generic Drug Market: Indispensable yet Unsustainable

The global generic drug market operates on a fundamental contradiction. It is simultaneously one of the most successful public health interventions of the past half-century, serving as the bedrock of affordable medicine access for billions, and a deeply flawed economic system teetering on the brink of unsustainability. This introductory section frames this central paradox, establishing the immense value generics provide while introducing the systemic vulnerabilities that have rendered the market economically fragile and prone to failure. The core tension arises from a system that has been optimized for a single variable—lowest unit price—at the expense of all others, including quality, reliability, and supply chain resilience.

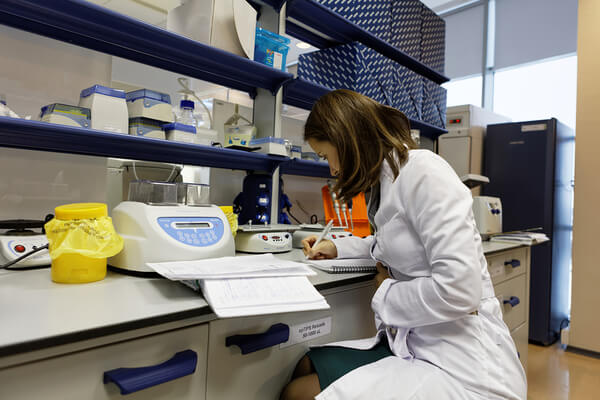

The Economic Bedrock of Modern Healthcare: Quantifying the Value and Savings

Generic medicines are not a peripheral segment of the pharmaceutical industry; they are its high-volume, low-cost foundation. In the United States, their role is dominant. In 2023, 89% of all prescriptions dispensed were filled with a generic drug, yet these medications accounted for only 26% of the nation’s total drug costs.1 This powerful dynamic of high utilization and low cost generates staggering savings. In a single recent year, the use of affordable generic medicines saved the U.S. healthcare system an estimated $216 billion.2 Over the past decade, the cumulative savings from generic and biosimilar medicines have been estimated at an astonishing $3.1 trillion, with savings of $445 billion in 2023 alone.3

This value proposition—providing bioequivalent, safe, and effective alternatives to brand-name drugs at a fraction of the cost—is replicated globally.3 In Europe, generic medicines represent approximately 70% of the treatment volume but only 19% of the total market value in monetary terms. This efficiency saved European payers an estimated €100 billion in 2014, a figure that has only grown since.5 The market’s immense scale is projected to expand further, from a global valuation of roughly $500 billion in the mid-2020s to well over $700 billion by the early 2030s.3 This growth is largely propelled by the increasing prevalence of chronic diseases requiring long-term medication and, most significantly, by the cyclical expiration of patents on blockbuster brand-name drugs.3 These figures establish generics as the fundamental mechanism for managing national health expenditures and ensuring broad patient access to essential treatments, making them indispensable to the financial sustainability of modern healthcare systems.1

The Central Tension: How Cost-Containment Imperatives Undermine Market Stability

Despite their indispensable role, the generic drug industry is in a state of crisis. The very forces that create its immense societal value—intense competition and the relentless downward pressure on prices—are the same forces that threaten its long-term viability.8 The market is caught in a destructive “downward spiral”: as demand for affordable generics rises, more manufacturers enter the market, and an expedited U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval process accelerates their ability to keep up. However, this surge in supply often outstrips demand, causing prices to collapse. This downward pricing pressure is exacerbated by the immense leverage of consolidated drug buyers. As prices and profitability decline, many manufacturers are forced to exit markets for specific drugs, leading to a contraction in supply. This, in turn, creates shortages and a situation where demand once again exceeds supply, restarting the cycle.9

This is not a theoretical model; it is the lived reality of the market. The economic unsustainability of producing many low-cost generics has led an estimated 3,000 products to be withdrawn from the market over the last decade simply because they were no longer profitable to manufacture.10 The market has been so thoroughly optimized for the lowest possible price that it has systematically devalued and financially punished other critical attributes, such as supply chain resilience, investment in modern manufacturing, and geographic diversification.8 The result is a brittle ecosystem where the pursuit of extreme affordability has paradoxically led to widespread unavailability. The foundational flaw of the market is a fundamental mispricing of value. The current system values a generic drug almost exclusively by its unit price, ignoring the immense, yet unquantified, costs imposed on the entire healthcare system when that drug is absent due to a shortage. These secondary costs—including higher labor expenses for hospitals to manage shortages, the need to use more expensive therapeutic alternatives, and, most critically, negative patient outcomes like treatment delays and medication errors—are not factored into the procurement price of a generic pill.8 A drug that costs $0.10 per unit but is frequently unavailable is, in reality, infinitely more expensive to the system than a drug that costs $0.15 but is backed by a secure and resilient supply chain. The failure to recognize and reward the “value of reliability” is the central market failure that subsequent sections of this report will explore and seek to address.

Market Size and Growth Trajectory: A Global and U.S. Perspective

On the surface, the market’s growth projections appear robust, masking the underlying economic fragility. The U.S. generic drugs market, the largest single market globally, is expected to grow from approximately $95.87 billion in 2024 to $131.80 billion by 2033, representing a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 3.60%.7 Another market analysis projects a higher starting point of $138.18 billion in 2024, growing to $188.82 billion by 2033 at a CAGR of 3.53%.4

Globally, the picture is similar. The market is projected to expand from $515.07 billion in 2025 to around $775.61 billion by 2033, with a CAGR of 5.25%.4 This growth is not speculative; it is underpinned by one of the largest “patent cliffs” in pharmaceutical history. Between 2025 and 2030, branded drugs generating an estimated $217 billion to $236 billion in annual sales are set to lose their market exclusivity, opening up massive new opportunities for generic competitors.3

However, this top-line growth is deceptive. It is driven by the continuous cycle of new market entry opportunities created by patent expiries, but the profitability of each opportunity is increasingly compressed. The intense price erosion that follows generic entry means that the window for recouping the significant investment in development, regulatory approval, and manufacturing is perilously short. This transforms the market from a stable manufacturing industry into a high-stakes “gauntlet” where speed to market is paramount and long-term profitability is elusive for all but the most efficient, high-volume producers.8

II. The Unrelenting Economic Gauntlet: Price Erosion, Buyer Consolidation, and Vanishing Margins

The economic environment of the generic drug market is defined by a relentless and systematic erosion of price and profitability. This “race to the bottom” is not a market anomaly but the direct result of its structural design: a multi-competitor model on the supply side clashing with a highly consolidated and powerful buyer base on the demand side. This section provides a granular analysis of these economic forces, demonstrating how they create a brutal competitive landscape that destabilizes the supply base and makes the production of many essential medicines economically unsustainable.

The Anatomy of Price Erosion: From First Generic Entry to Market Saturation

The moment a brand-name drug’s patent expires and the first generic competitor enters the market, a predictable and precipitous price decline begins. This process of commoditization is swift and severe, leaving a very narrow window for manufacturers to achieve profitability. The data on this price erosion is stark and consistent:

- First Generic Entry: A single generic competitor typically slashes the price by 30% to 39% compared to the pre-entry brand price.8

- Second and Third Entry: With just two competitors in the market, the average manufacturer price falls by 54%. With three, it plummets further.13

- Market Saturation: Once six or more generic competitors are on the market, the price collapses by a staggering 95% for most drugs.13 With ten or more competitors, margins become razor-thin or non-existent, and only the most efficient, high-volume manufacturers can sustain profitability.8

In Europe, a similar dynamic is observed, with prices falling by an average of approximately 60% after a brand drug loses exclusivity.5 This rapid commoditization creates a high-stakes environment where the timing of market entry is critical. In the U.S., the Hatch-Waxman Act provides a 180-day period of market exclusivity to the first company that successfully challenges a brand’s patent and files an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA). This exclusivity period is a crucial, but fleeting, opportunity for profitability that provides the primary economic incentive for generic manufacturers to undertake costly and risky patent litigation.14 After this 180-day window, the market quickly becomes saturated as other approved generics launch, and the price war begins in earnest, driving margins toward zero.

The Power of the Buyers: How GPOs and PBMs Dictate Market Dynamics

The rapid price erosion is not solely the result of competition among manufacturers; it is aggressively accelerated by the highly consolidated structure of the buyer side of the U.S. market. A small number of powerful intermediary organizations wield immense purchasing power, giving them the leverage to demand steep discounts and effectively set market prices.

- Group Purchasing Organizations (GPOs): GPOs serve as purchasing agents for hospitals, nursing homes, and other healthcare providers. By aggregating the purchasing volume of their thousands of members, they negotiate contracts for a vast array of medical products, with a primary focus on generic drugs for inpatient use.15 GPOs are a key force in driving down prices in the hospital setting, and their contracting practices are currently under investigation by the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) for their potential role in contributing to drug shortages.16

- Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs): PBMs manage prescription drug benefits on behalf of health insurers, large employers, and government programs, covering over 289 million Americans.17 They create formularies (lists of covered drugs), negotiate rebates with brand manufacturers, and set reimbursement rates for pharmacies. Their influence on the retail prescription market is immense.

Together, these intermediaries represent a formidable concentration of buyer power. A 2018 analysis found that just three large buying groups—one GPO and two PBM-affiliated purchasing groups—controlled between 72% and 81% of all generic drug purchases in the United States.8 This consolidation transforms generic manufacturers into “price-takers” rather than “price-setters”.1 To gain access to the vast markets controlled by these gatekeepers, manufacturers have little choice but to accept the razor-thin margins dictated by them. This dynamic is a primary structural driver of the “race to the bottom” on price.

The “Race to the Bottom”: Market Withdrawals, Unlaunched Products, and the Threat to Supply

The inevitable outcome of this intense price competition and buyer consolidation is an economic model that is fundamentally broken for many essential medicines. The pressure to produce at the lowest possible cost has rendered a significant portion of the generic drug portfolio unprofitable, leading to market instability and threatening the reliability of the drug supply.

The evidence of this market failure is clear:

- Unlaunched Products: Approximately 30% of generic drugs that receive FDA approval are never launched. By the time they are approved, the market has often become so saturated and prices have fallen so low that there is no longer a viable business case for entering.10

- Manufacturing at a Loss: Many firms report that they are actively losing money on certain products in their portfolios but continue to manufacture and distribute them in the interest of maintaining patient access and fulfilling contractual obligations.10 This is an inherently unsustainable practice.

- Market Withdrawals: The most direct consequence of this unprofitability is market withdrawal. An estimated 3,000 generic drug products have been withdrawn from the market over the past decade because they were no longer economically viable to produce.10

This creates a profound public health paradox: the system’s success in achieving the lowest possible price directly undermines the economic foundation required for a stable and resilient supply base. When profitability vanishes, so does the incentive for manufacturers to produce the drug, invest in quality systems, or maintain redundant manufacturing capacity. This leads inexorably to a market with fewer and fewer suppliers for a given drug, increasing the risk that a single quality failure or disruption at one of the remaining facilities will result in a nationwide shortage.8

The structure of the generic market closely resembles the economic model of perfect competition, where numerous sellers of a homogenous product lead to prices being driven down to the marginal cost of production, with long-run profits approaching zero.8 While this model is theoretically efficient for simple commodities, its application to pharmaceuticals has produced a dangerous, imperfect outcome. Pharmaceuticals are not simple commodities; their consistent availability is a matter of public health, and their manufacturing requires significant upfront investment and adherence to stringent quality standards.2 The “efficiency” of driving prices to marginal cost has systematically stripped out the financial buffer necessary for manufacturers to invest in the very things that create resilience: redundant capacity, modern equipment, robust quality management systems, and geographically diversified supply chains. These investments are costly and run directly counter to the market’s singular imperative to produce at the lowest possible price.18 The market is therefore “efficient” at producing low prices but dangerously “inefficient” at producing a resilient supply. Any meaningful solution must address this fundamental market failure by creating mechanisms that value and reward reliability, not just low cost.

Table 1: The Economics of Generic Entry – Price Reduction vs. Number of Competitors

| Number of Generic Competitors | Approximate Price Reduction vs. Brand Price | Strategic Implication for Manufacturers |

| 1 | 39% | Brief window of profitability during 180-day exclusivity; high stakes for first-to-file status. |

| 2 | 54% | Exclusivity ends; intense price competition begins immediately. |

| 3 | 60-70% | Market approaches saturation; profitability becomes highly dependent on manufacturing scale and efficiency. |

| 6+ | 85-95% | Margins become razor-thin or non-existent; market is fully commoditized. |

| 10+ | >95% | Profitability is unsustainable for many; risk of market withdrawals increases significantly. |

Data compiled from sources 8, and.8

III. The Global Supply Chain’s Fragile Foundation: Geopolitical Risks and the Drug Shortage Crisis

The extreme economic pressures detailed in the previous section have had a profound and predictable effect on the physical structure of the pharmaceutical supply chain. The relentless global search for the lowest possible manufacturing cost has led to a system that is not merely globalized, but dangerously hyper-concentrated and brittle. This section will map the geography of this fragility, detailing the critical U.S. dependency on a small number of foreign countries for essential medicine production and linking this structural vulnerability directly to the escalating public health crisis of drug shortages.

Geographic Concentration: Mapping the U.S. Dependency on China and India for APIs and KSMs

The manufacturing of generic drugs for the U.S. market is overwhelmingly concentrated in a few overseas locations. This geographic consolidation is not an accident but the logical endpoint of decades of cost-driven offshoring.20 The result is a critical dependency that poses significant risks to U.S. public health and national security.

- Dominance of India and China: Over 80% of the Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs)—the core therapeutic components of a drug—used in medicines consumed in the U.S. are sourced from China and India.21

- India as the Finished Product Hub: India has earned the title “pharmacy of the world” and is the single largest supplier of finished generic drugs to the United States. It supplies nearly 47% of U.S. generic prescriptions, with annual exports valued at over $10.5 billion.2

- China as the Upstream Foundation: The dependency is multi-layered and even more precarious than it appears. While India is the primary source of finished products, it, in turn, sources 70% to 80% of its own APIs from China.8 China’s dominance is most acute further upstream in the production of Key Starting Materials (KSMs), raw materials, and chemical intermediates. It is estimated that China controls 80% to 90% of the global supply for essential inputs used in critical medicines like antibiotics.24

This structure is not a diversified global network; it is a sequential dependency. The U.S. depends on India for finished drugs, and India depends on China for the ingredients to make those drugs. This creates multiple single points of failure where a disruption in one country, or even at a single large manufacturing facility, can have cascading and severe consequences for the entire U.S. medicine supply.8 The 2023 shutdown of a single plant in India, which was responsible for 50% of the U.S. supply of the critical chemotherapy drug cisplatin, caused immediate and widespread nationwide shortages, perfectly illustrating the system’s inherent brittleness.8

From Trade Wars to Export Bans: Assessing Geopolitical Vulnerabilities

The hyper-concentration of the supply chain in a few nations transforms what was once a purely logistical and economic consideration into a significant geopolitical vulnerability. The reliable supply of essential medicines to the American public is now subject to the political and economic stability of other countries, as well as the state of international relations.25

The threat of tariffs is a prime example. The proposed 25% U.S. tariff on all Indian imports, while currently exempting pharmaceuticals, sent a shockwave through the industry and highlighted how quickly trade policy can threaten the viability of the low-margin generic business model.2 An even more direct threat is the risk of export bans. During times of crisis, such as a pandemic or a national emergency, it is common for governments to restrict the export of critical goods to protect their domestic populations. Several countries, including India and France, have recently banned or threatened to ban the export of drugs in short supply.25 This creates a scenario where a drug may be successfully manufactured but cannot leave its country of origin, effectively severing the supply chain regardless of production capacity. The reliance on potential geopolitical rivals for the foundational components of the U.S. medicine supply represents a critical national security risk that can no longer be ignored.20

The Drug Shortage Epidemic: Root Causes, Patient Impact, and Economic Costs

Drug shortages are the ultimate and most damaging manifestation of the market’s interconnected economic and structural failures. They are not random, unavoidable events but the predictable and worsening outcome of a system that has prioritized the lowest possible cost over supply chain resilience.

The scale of the crisis is alarming. In 2023, the U.S. experienced an average of 301 ongoing drug shortages per quarter, the highest level in a decade.8 The root causes are directly linked to the vulnerabilities previously discussed:

- Manufacturing and Quality Failures: Over 60% of drug shortages are attributed to manufacturing or quality problems.8 These failures are often the result of underinvestment in aging facilities and inadequate quality management systems—a direct consequence of the economic pressure to cut costs to unsustainable levels.18

- Supply Chain Disruptions: The geographic concentration of manufacturing means that a single event—a natural disaster, a regulatory shutdown of a plant, or a geopolitical disruption—can wipe out a significant portion of the global supply for a given drug. Generic sterile injectable drugs, which are complex to manufacture and often produced in a small number of specialized facilities, are particularly vulnerable and account for a disproportionate share of active shortages.18

The impact of these shortages on the healthcare system and patients is severe and multifaceted. For patients, shortages lead to delayed or canceled treatments, the use of less effective or higher-risk alternative therapies, and medication errors as healthcare providers are forced to work with unfamiliar products. In the most tragic cases, shortages have been linked to increased patient mortality.8 For hospitals, managing shortages is a massive and costly operational burden, consuming an estimated $216 million annually in labor costs alone as pharmacists and technicians scramble to find alternative supplies. When forced to purchase from the “grey market,” hospitals can face markups of 300-500% over the normal price, further straining already tight budgets.8

Table 2: Key Vulnerabilities in the U.S. Pharmaceutical Supply Chain

| Vulnerability Category | Description of Vulnerability | Primary Risk(s) |

| Upstream Sourcing (KSMs & Raw Materials) | Hyper-concentration of Key Starting Materials (KSMs), solvents, and reagents in a single country, primarily China. | Geopolitical conflict, export bans, localized industrial accidents, environmental shutdowns. |

| API Manufacturing | Over-reliance on a limited number of foreign countries (China, India) for the majority of Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs). | Cascading supply disruption (e.g., China disruption impacts Indian FDF production), quality control failures, trade disputes. |

| Finished Dosage Form (FDF) Manufacturing | Heavy dependence on India for finished generic drugs, especially for oral solids and sterile injectables. Lack of redundant domestic sterile injectable capacity. | Single-point-of-failure shortages due to plant shutdowns, natural disasters, or quality failures. Inability to surge domestic production in a crisis. |

| Logistics & Distribution | “Just-in-time” inventory models with minimal buffer stock across the supply chain, from manufacturers to hospitals. | Inability to absorb sudden demand spikes or short-term supply interruptions, leading to immediate stockouts. |

Data compiled from sources 8, and.8

IV. Navigating the Intermediary Maze: The Influence of PBMs and GPOs on Pricing and Access

The economic pressures and supply chain vulnerabilities of the generic drug market are not solely the result of abstract market forces. They are actively shaped and amplified by the powerful intermediaries that sit between manufacturers and end-users: Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs) and Group Purchasing Organizations (GPOs). While their stated purpose is to contain costs for their clients, their complex and often opaque business models create market distortions, misaligned incentives, and conflicts of interest that contribute directly to the fragility of the generic drug ecosystem. This section will dissect the roles and practices of these intermediaries, analyzing how they influence pricing, control access, and extract value from the supply chain.

The Role of Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs): Rebates, Formularies, and Spread Pricing

PBMs are a dominant force in the U.S. healthcare system, managing the prescription drug benefits for health plans and employers that cover more than 289 million Americans.17 Their core functions include negotiating with drug manufacturers, creating formularies that determine which drugs are covered, and processing pharmacy claims.28 However, the mechanisms through which they generate revenue have become a source of significant controversy.

A central issue is the system of manufacturer rebates. PBMs negotiate substantial rebates from brand-name drug manufacturers in exchange for favorable placement on their formularies. A critical flaw in this model is that these rebates are often calculated as a percentage of a drug’s list price. This creates a perverse incentive for PBMs to favor higher-priced brand drugs over more cost-effective alternatives, including generics and biosimilars, because a percentage of a higher price yields a larger rebate.29 This dynamic can lead to situations where PBMs actively block access to new, lower-cost generics to protect the lucrative rebate streams associated with an existing brand-name drug.10

While generic manufacturers rarely, if ever, negotiate rebates, PBMs have another mechanism for profiting from them: “spread pricing.” This practice involves the PBM charging a health plan a higher price for a generic drug than the amount it reimburses the pharmacy that dispensed it. The PBM then pockets the difference, or “spread”.28 This practice is particularly prevalent in the generic market and is enabled by a lack of transparency; the payment schedules between the PBM and the pharmacy are typically kept confidential from the health plan. The three largest PBMs reportedly generated an estimated $1.4 billion from spread pricing on just 51 generic specialty drugs over approximately five years.28 This business model fundamentally misaligns incentives, as PBM profitability is not always tied to securing the lowest net cost for the healthcare system but can be linked to maximizing rebate revenue and spread, which can obscure the true cost of medications and disadvantage lower-cost generic alternatives.

The Function of Group Purchasing Organizations (GPOs): Aggregated Demand and Contractual Pressures

In the inpatient and hospital setting, GPOs play a role analogous to PBMs. They act as purchasing agents for thousands of healthcare providers, aggregating their collective demand to negotiate discounts from manufacturers, with a primary focus on generic drugs.15 Nearly every U.S. hospital utilizes a GPO to achieve savings and supply chain efficiencies.30

Like PBMs, GPOs represent a massive concentration of buyer power that exerts intense downward price pressure on manufacturers, contributing to the “race to the bottom” that erodes profitability.8 While their goal is to save money for their hospital members, the relentless focus on securing the lowest possible price can inadvertently contribute to the economic unsustainability that leads to drug shortages. This creates a vicious cycle where the pursuit of short-term savings by hospitals, facilitated by GPOs, ultimately results in the long-term instability and unavailability of the very products those hospitals need to treat patients. The growing concern that GPO contracting practices may be part of the drug shortage problem has prompted a formal Request for Information (RFI) from the FTC and HHS to investigate their market impact.16 GPO contracts often include “failure to supply” clauses intended to penalize manufacturers who cannot meet their obligations. However, these clauses are often ineffective in practice, especially when a drug is in shortage and no alternative source is available, and their strength has reportedly been eroded in recent years.18

Controversies and Calls for Reform: Addressing Transparency and Conflicts of Interest

A central criticism leveled against both PBMs and GPOs is the profound lack of transparency in their operations.18 The details of their financial arrangements—including the true size of rebates, the methodology for calculating administrative fees, and the profits generated from spread pricing—are often shrouded in confidentiality. This opacity makes it nearly impossible for payers, employers, and policymakers to understand the true flow of money within the drug supply chain and to verify whether these intermediaries are delivering real value or simply extracting profits.

This lack of transparency also allows for potential conflicts of interest to flourish, particularly in the case of the large, vertically integrated PBMs that now own their own specialty, mail-order, and retail pharmacies.28 This structure creates an incentive for PBMs to steer patients towards their affiliated pharmacies, potentially at a higher cost to the health plan and to the detriment of independent pharmacies.

In response, policymakers at both the federal and state levels are considering a range of reforms aimed at increasing transparency and realigning incentives. Key proposals include:

- Banning Spread Pricing: To ensure that payers are not overpaying PBMs for generic drugs.

- Requiring Greater Transparency: Mandating the disclosure of rebates and fees to allow for a clearer understanding of pharmaceutical spending.

- Delinking Rebates from List Prices: Restricting the practice of basing rebates on a drug’s list price and instead moving to a flat, fee-for-service model that reflects the fair market value of the services PBMs provide.28

These reform efforts aim to shed light on the “black box” operations of market intermediaries. The underlying logic is that while these entities play a role in cost containment, their business models have also evolved to become significant cost extractors. Analysis of the generic drug value chain shows that the supply chain—including wholesalers, PBMs, and pharmacies—captures a staggering 64% of all revenue, while the manufacturer who develops, tests, and produces the drug retains only a fraction.1 This massive value transfer away from producers further squeezes their already thin margins, reinforcing the economic pressures that lead to underinvestment and market withdrawals. Therefore, reforming the practices of these intermediaries is not an ancillary issue; it is central to addressing the root causes of the generic market’s instability.

V. The Regulatory Tightrope: Balancing Expedited Approval with Evolving Quality Standards

The regulatory framework governing generic drugs is a critical determinant of the market’s structure and function. In the United States, this framework is designed to achieve two primary goals: to expedite the availability of low-cost alternatives to brand-name drugs and to ensure that these alternatives meet the same high standards of quality, safety, and efficacy. This section examines this regulatory balancing act, highlighting how the streamlined approval process both enables the market and creates inherent challenges through significant user fees, complex scientific requirements, and a persistent lack of global harmonization.

The ANDA Pathway: A Streamlined Process with Inherent Hurdles

The cornerstone of the U.S. generic drug market is the Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) pathway, a regulatory process established by the landmark Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984, commonly known as the Hatch-Waxman Act.31 The pathway is termed “abbreviated” because it allows a generic drug applicant to rely on the FDA’s previous findings of safety and effectiveness for the original, brand-name drug (referred to as the Reference Listed Drug, or RLD). This relieves the generic manufacturer of the need to conduct costly and duplicative preclinical and clinical trials, which are the most expensive and time-consuming aspects of new drug development.31

Instead of full clinical trials, the scientific pillar of an ANDA is the demonstration of bioequivalence (BE). The applicant must scientifically prove that their generic product performs in the same manner as the innovator drug. This is typically achieved through pharmacokinetic studies in a small group of healthy volunteers, which measure the rate and extent to which the active ingredient is absorbed into the bloodstream. To be approved, the generic version must deliver the same amount of active ingredient into a patient’s bloodstream in the same amount of time as the RLD, with key metrics falling within a statistically defined range of 80% to 125% of the brand-name product.31

While the ANDA pathway successfully created the modern, competitive generic market, the process is not without significant hurdles. Proving bioequivalence, particularly for more complex products like topical creams, inhalers, or long-acting injectables, can be a formidable scientific and financial challenge. For these complex generics, simple blood-level studies may be insufficient, and the FDA may require more extensive testing, including full clinical endpoint studies that are akin to the efficacy trials required for new drugs. This can add millions of dollars and years of development time to a project, acting as a significant barrier to entry and limiting competition for these higher-value products.8

The GDUFA Effect: The Dual Impact of User Fees on Speed and Market Entry

In 2012, Congress enacted the Generic Drug User Fee Amendments (GDUFA) to address a growing backlog of unreviewed ANDAs and to provide the FDA with the resources needed to ensure a more predictable and efficient review process.8 Under GDUFA, the generic drug industry pays user fees to the FDA, which are used to hire additional reviewers and upgrade information technology systems.

GDUFA has been successful in improving the efficiency and predictability of the review process, which is a significant benefit for manufacturers planning their product launches. However, this progress has come at a substantial cost. The user fees are significant, non-refundable, and largely due upfront. For Fiscal Year 2025, the major fees include:

- ANDA Filing Fee: $321,920

- Drug Master File (DMF) Fee: $95,084

- Annual Program Fee (Large Company): $1,891,664

- Annual Facility Fees: Ranging from $41,580 to $246,952 depending on the facility type.8

This fee structure represents a double-edged sword. While it funds a more efficient regulatory apparatus, the high upfront costs act as a significant financial barrier to entry. This is particularly true for smaller companies or those targeting niche products with more modest revenue potential. The decision to pursue a generic candidate is no longer just a scientific and legal one; it has become a major capital allocation decision requiring a six- or seven-figure upfront investment before any revenue is generated.8 This financial hurdle forces companies to be highly selective, prioritizing only products with a high probability of success and a sufficient market size to justify the investment. This can leave smaller patient populations underserved and contributes to market consolidation, as only larger, well-capitalized firms can afford to absorb the costs and risks of a broad development portfolio.

Global Harmonization Challenges and the Burden of Divergent Standards

For generic drug manufacturers operating on a global scale, the lack of true regulatory harmonization among major markets like the United States, Europe, and Japan presents a major operational and financial challenge. While regulatory agencies like the FDA and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) share the same overarching goal of ensuring safe and effective medicines, their specific data requirements, review processes, and timelines can differ significantly.8

While studies have shown a high degree of concordance in the final approval decisions between the FDA and EMA, the timing of those approvals can differ by several years.8 Furthermore, differences in the technical requirements for bioequivalence studies—such as testing in fasting versus fed states or the statistical analysis of highly variable drugs—can necessitate separate studies for each jurisdiction. A primary obstacle to harmonization is the common requirement that bioequivalence studies must use a reference product that is sourced from the local market (e.g., an ANDA submitted to the FDA must use a U.S.-sourced RLD). This single rule often forces manufacturers to conduct duplicative, expensive, and time-consuming clinical studies to get the same product approved in different regions.8

This lack of harmonization prevents companies from leveraging a single global development program efficiently. It adds unnecessary cost, complexity, and delay to the process of bringing affordable medicines to patients. In smaller markets, the high cost of conducting a separate, localized approval process can be prohibitive, effectively denying patients in those countries access to lower-cost generic alternatives. While initiatives like the International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) continue to work towards common standards, the path to true global harmonization remains long and challenging. The regulatory framework, while designed to foster competition, inadvertently contributes to market consolidation. The combination of high fixed costs from GDUFA, the variable costs of navigating non-harmonized global regulations, and the severe price erosion post-launch creates an environment where only large-scale players with deep capital reserves can effectively compete. This favors industry consolidation, which can paradoxically lead to less competition for certain drugs and exacerbate the risk of shortages.

VI. A Strategic Framework for Stability and Affordability: Policy, Technology, and Market Reforms

Addressing the multifaceted challenges confronting the generic drug market requires a comprehensive and integrated strategic framework. A piecemeal approach focused on a single issue will inevitably fail, as the problems of economic unsustainability, supply chain fragility, and market distortion are deeply interconnected. A sustainable solution demands a portfolio of policies that realign incentives across the entire value chain, moving the system from a myopic focus on unit price to a more holistic valuation that includes reliability, quality, and supply chain security. This section outlines such a framework, organized around three synergistic pillars: policy and reimbursement reform, supply chain fortification, and the harnessing of technological innovation.

Policy and Reimbursement Reform

The root cause of the market’s fragility is economic. Therefore, policy and reimbursement reforms that address the flawed financial incentives are the most critical starting point for building a more stable system.

Lessons from European Models: Reference Pricing, Tendering, and Substitution Policies

While the U.S. market is largely market-based, European healthcare systems employ a range of more interventionist policies to control drug costs and promote generic use. Although these models have their own challenges, they offer valuable lessons.

- Reference Pricing: Many European countries use reference pricing systems, where public or private insurers set a maximum reimbursement level (a “reference price”) for a group of therapeutically similar drugs. This encourages patients and providers to choose the lower-cost options within that group.35

- Tendering: In some countries, like Germany and Denmark, health insurers use a competitive bidding or “tendering” process to procure generic drugs in bulk. Manufacturers submit bids, and the insurer awards a contract to the one offering the best price, often on a “winner-takes-all” basis for a specific region or time period.35

- Mandatory Substitution: In contrast to the U.S., where substitution is often voluntary, it is mandatory in many European countries for pharmacists to dispense a generic version of a prescribed brand-name drug unless the physician explicitly forbids it. This policy lever dramatically increases generic utilization rates.35

While these policies are effective at driving down prices and increasing volume, they can also create hyper-competitive markets with “unsustainable” price pressure, as seen in Germany, where generic prices have fallen even as consumer prices have risen.38 A direct importation of these models may not be suitable for the U.S. context. However, they demonstrate that alternative market designs are possible and that policy levers can be used to shape market outcomes. The key is to adapt these ideas to foster healthy competition without completely destroying the economic incentives for manufacturers to remain in the market. For instance, moving away from “winner-takes-all” tenders to “multi-winner” models could help maintain a more diverse and resilient supplier base.

Re-evaluating the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA): Mitigating Unintended Consequences for Generic Competition

The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) of 2022 represents the most significant reform to U.S. drug pricing in decades. Its central provision allows Medicare to directly negotiate prices for a selection of high-spending drugs that lack generic or biosimilar competition.39 While the goal of lowering drug costs for Medicare and its beneficiaries is laudable, the mechanism of the IRA poses a significant and potentially existential threat to the generic drug industry.

The core problem is one of timing and incentives. The IRA targets the very blockbuster drugs that are the most attractive and lucrative opportunities for generic manufacturers.13 By allowing the government to negotiate a “maximum fair price” (MFP) for a brand-name drug

before its patents expire and generic competition can naturally begin, the IRA dramatically lowers the price anchor against which generics must compete. This severely erodes the potential revenue and return on investment for a generic manufacturer, weakening the financial incentive to undertake the costly and risky process of development and patent litigation needed to bring a generic to market.13

Furthermore, the law’s “pill penalty” subjects small-molecule drugs (traditional pills and capsules) to price negotiation just seven years after their initial FDA approval, compared to eleven years for biologics. This discrepancy may shift pharmaceutical R&D investment away from the development of new small-molecule drugs, which would, in turn, shrink the pipeline of future generic opportunities.14

Conversely, some analyses suggest the IRA could be a “boon” for the industry by creating a powerful new incentive for brand manufacturers to allow or even encourage earlier generic entry. By permitting a generic or biosimilar to launch, a brand manufacturer can escape the government’s price negotiation process and the associated price controls.43

The long-term impact of the IRA remains uncertain and highly contested. However, there is a clear risk that by substituting government price-setting for market-based competition, the IRA could unintentionally undermine the very generic competition that has been the most effective tool for lowering drug prices for the past four decades. Policymakers should closely monitor the effects of the IRA on generic market entry and be prepared to make legislative adjustments—such as modifying the negotiation timelines or creating stronger safe harbors for generic entry—to ensure a balance between achieving near-term savings for Medicare and preserving the long-term health of a competitive generic market.

Incentivizing Resilience: Proposals for a Manufacturer Resiliency Assessment Program (MRAP) and Hospital Resilient Supply Program (HRSP)

Perhaps the most innovative and promising policy proposals aim to correct the market’s fundamental failure to value reliability. Recognizing that the market does not reward manufacturers for investing in resilient practices, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) has put forth concepts for two interconnected programs:

- Manufacturer Resiliency Assessment Program (MRAP): This program would establish a system for rating pharmaceutical manufacturers on their supply chain resilience. The ratings would be based on an objective assessment of practices such as quality management maturity, manufacturing redundancy (e.g., having multiple production sites), and the diversity of their API and KSM sourcing.18 This initiative aligns closely with the FDA’s ongoing work to develop a Quality Management Maturity (QMM) rating system for manufacturing sites.44

- Hospital Resilient Supply Program (HRSP): This program would create a direct economic incentive for resilience by linking Medicare payments to hospitals to their purchasing practices. Under HRSP, hospitals would be rewarded—through incentive payments or protected from penalties—for purchasing essential medicines from manufacturers with high resilience scores under the MRAP. The program would also incentivize hospitals to adopt their own resilience practices, such as maintaining buffer stocks and negotiating contracts that include effective failure-to-supply clauses.18

Together, these programs represent a paradigm shift. They move beyond simply punishing bad actors and instead create a positive, market-based incentive for good behavior. By making resilience a tangible and compensated attribute, MRAP and HRSP would create a business case for manufacturers to invest in quality and supply chain security. This is a crucial step toward moving the generic market from a pure price-based model to a more sophisticated value-based model where the reliability of supply is recognized and rewarded.

Strengthening the Supply Chain

Policy reforms must be paired with concrete strategies to re-engineer the physical supply chain, reducing its fragility and building in the redundancy needed to withstand disruptions.

Strategic Onshoring and Diversification: A Realistic Approach Beyond Full Reshoring

In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic and rising geopolitical tensions, there have been strong calls to “onshore” or “re-shore” all pharmaceutical manufacturing to the United States to eliminate foreign dependencies.8 While well-intentioned, a full reshoring of the low-margin generic drug industry is economically unviable and logistically impractical. The high capital costs of building new GMP-compliant facilities in the U.S., coupled with higher labor and environmental compliance costs, would make domestic production uncompetitive without massive and permanent government subsidies.8

A more realistic and strategic approach involves a combination of targeted onshoring, near-shoring, and “friend-shoring.”

- Targeted Onshoring: The government, in partnership with industry, should identify a list of the most critical and vulnerable medicines—such as essential sterile injectables for acute care—and use a combination of tax incentives, grants, and long-term purchasing guarantees to support the establishment or expansion of domestic manufacturing capacity for this limited set of products.20

- Diversification and “Friend-Shoring”: For the broader portfolio of generics, the goal should be diversification rather than complete repatriation. This involves working with geopolitical allies and partners in different regions (e.g., Europe, North America, Southeast Asia) to create a more distributed and redundant global manufacturing network. This approach reduces over-reliance on any single country, thereby mitigating the risk of a single point of failure without abandoning the efficiencies of a global supply chain.45

Enhancing the Strategic National Stockpile (SNS) for Generic Medicines

The Strategic National Stockpile (SNS) is the U.S. government’s federal inventory of medical countermeasures, designed to be deployed during public health emergencies.48 Historically, its focus has been on threats like bioterrorism (e.g., anthrax, smallpox) and pandemics.50 However, the SNS could and should play a more significant role in mitigating shortages of essential generic drugs.

This would require a strategic evolution of the SNS’s mission and funding to include the maintenance of a rotating buffer stock of critical, shortage-prone generic medicines. This would not replace the need for a resilient commercial supply chain but would act as a crucial public backstop to mitigate the immediate impact of private market failures. An enhanced SNS could provide the healthcare system with a crucial bridge of supply during a sudden shortage, buying time for manufacturers to resolve production issues and ramp up supply. However, the SNS currently faces its own challenges, including outdated guidance, undefined agency roles, and inventory gaps due to budget constraints, all of which would need to be addressed to expand its mission effectively.50

Public-Private Partnerships to De-risk Domestic Manufacturing Investments

Rebuilding domestic manufacturing capacity for even a targeted list of essential medicines requires massive capital investment that the private sector is unlikely to undertake on its own, given the low-margin nature of generics. Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs) are a critical tool for bridging this gap between public health needs and private market incentives.52

Through PPPs, government agencies such as the Department of Defense (DoD), the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), and HHS can offer long-term, guaranteed-volume purchasing contracts to companies willing to invest in domestic manufacturing facilities.20 These contracts would de-risk the investment for private manufacturers by ensuring a predictable stream of revenue, making the construction of a new U.S.-based facility economically viable. This model effectively allows the government to create a market for resilience, using its purchasing power to guarantee demand for domestically produced essential medicines. The FDA and other agencies are already successfully using PPPs to advance innovative manufacturing technologies, providing a proven model that can be expanded to bolster the domestic production base.53

Harnessing Technological Innovation

Technological innovation offers a powerful set of tools to address some of the core challenges of the generic drug market. By reducing the cost and risk of development and improving the quality and efficiency of manufacturing, new technologies can help mitigate the economic pressures on the industry and make domestic production more competitive.

Advanced Manufacturing: The Potential of Continuous Manufacturing and 3D Printing

Advanced Manufacturing Technologies (AMTs) have the potential to transform the decades-old, batch-based production model of the pharmaceutical industry.

- Continuous Manufacturing: This approach integrates all production steps—from raw material input to finished product output—into a single, seamless, and uninterrupted flow. Compared to traditional batch processing, continuous manufacturing offers numerous advantages, including a smaller physical footprint, faster production times, greater flexibility to respond to demand fluctuations, and, most importantly, improved quality control through real-time monitoring and adjustment of the process.54 The FDA has actively encouraged its adoption as a way to improve product quality and prevent shortages.

- 3D Printing (Additive Manufacturing): This technology offers a revolutionary approach to pharmaceutical production, enabling the creation of patient-specific, personalized medicines. 3D printing allows for the precise manufacturing of tablets with customized dosages, unique shapes for easier swallowing, and complex multi-drug combinations or release profiles that are impossible to achieve with conventional methods.55 In the context of supply chain resilience, 3D printing could enable on-demand, decentralized manufacturing in hospitals or pharmacies, reducing reliance on long, complex supply chains for certain products.

While the adoption of these technologies in the low-margin generic sector has been slow due to high upfront capital costs, they offer a clear path toward making domestic manufacturing more efficient, flexible, and cost-competitive, directly addressing some of the root causes of drug shortages.

Artificial Intelligence (AI): Transforming Generic Drug Development, Quality Control, and Portfolio Management

Artificial intelligence and machine learning are poised to revolutionize every aspect of the pharmaceutical industry, and the generic sector is no exception.59 AI offers a powerful toolkit to enhance efficiency, reduce costs, and mitigate risks across the generic drug lifecycle.

- Accelerated Development: AI algorithms can analyze vast datasets to optimize API synthesis pathways, predict drug-excipient compatibility to speed up formulation development, and model pharmacokinetic data to streamline bioequivalence testing. This can significantly reduce the time, cost, and failure rate of generic drug development.62

- Enhanced Manufacturing and Quality Control: In manufacturing, AI can be used for predictive maintenance of equipment to prevent costly breakdowns. AI-powered sensor and imaging systems can monitor production in real-time to detect deviations from quality standards, reducing batch failures and ensuring greater product consistency.62

- Strategic Portfolio Management: AI can analyze market data, patent landscapes, and regulatory trends to help companies make more informed and strategic decisions about which generic products to pursue, optimizing their R&D investments.

By reducing the high costs and risks associated with development and manufacturing, AI can help to counteract some of the severe economic pressures facing the industry, making the production of a wider range of generics more economically viable.

Table 3: Comparative Analysis of Generic Drug Policies: U.S. vs. Key European Markets

| Policy Lever | United States | Germany | United Kingdom | France/Spain |

| Price Controls | None; prices are market-based and set by manufacturers, heavily influenced by PBM/GPO negotiations. | Indirect controls via reference pricing and mandatory rebates. Tenders effectively set prices for large segments. | None; market-driven approach. Intense competition among manufacturers and pharmacies sets low prices. | Direct controls; new generics face mandatory price cuts relative to the originator. Reference Price Systems (RPS) cap reimbursement. |

| Reimbursement Model | PBM-negotiated rates for retail; GPO-negotiated contracts for hospitals. Complex rebate and spread pricing system. | Reference pricing system (Festbeträge) groups similar drugs for a single reimbursement cap. Sickness funds run tenders. | NHS sets a reimbursement price (Drug Tariff) for pharmacies, which is typically higher than the acquisition cost, incentivizing dispensing of low-cost generics. | Comprehensive Reference Price System (RPS) sets maximum reimbursement. Prices are negotiated with national health authorities. |

| Generic Substitution | Permissive; pharmacists can substitute in most states, but physicians can prevent it. Universally voluntary. | Pharmacist substitution is encouraged and widely practiced. Tendering contracts can make substitution for a specific brand mandatory. | Mandatory generic prescribing (by INN) is common practice. Pharmacist substitution is standard. | Substitution is encouraged but historically has faced lower uptake rates compared to Germany/UK. |

| Tendering/Bulk Purchasing | Not used in the retail pharmacy setting. GPOs conduct a form of competitive bidding for hospital contracts. | Dominant model for retail generics. Sickness funds award large, often exclusive, contracts to the lowest bidders. | Not a primary mechanism; price is driven by competition at the pharmacy and wholesaler level. | Used in some regions and hospital settings but not as dominant as in Germany. |

Data compiled from sources 35, and.36

VII. Conclusion: Reimagining a Resilient Generic Medicines Ecosystem

The generic drug market has reached a critical inflection point. For decades, it has operated as a remarkably successful engine of cost containment, delivering trillions of dollars in savings and making essential medicines accessible to the vast majority of patients. Yet, this report has demonstrated that the very architecture of this success is built upon a fragile and unsustainable foundation. The relentless, single-minded pursuit of the lowest possible unit price has created a brittle global supply chain, eroded the economic viability of manufacturing essential medicines, and left the public dangerously vulnerable to a persistent and growing crisis of drug shortages. The current path is untenable; incremental adjustments will not suffice to fix a system whose core incentives are fundamentally misaligned with the long-term goals of public health.

A fundamental shift in perspective is required—from viewing generic medicines as a low-cost commodity to recognizing the generic drug industry as a piece of critical national infrastructure. Like the power grid or the water supply, a reliable and resilient source of essential medicines is not a luxury but a prerequisite for a functioning society and a secure nation. This reimagining necessitates a new “social contract” for generic medicines, one that moves beyond a simplistic focus on price to embrace a more sophisticated understanding of value. In this new paradigm, affordability must be balanced with stability, and the value of a secure and reliable supply chain must be explicitly recognized and economically rewarded.

Achieving this vision requires an integrated and synergistic portfolio of reforms. Policy and reimbursement models must be redesigned to reward manufacturers for investing in quality and resilience, not just for offering the lowest price. This includes reforming the opaque practices of intermediaries like PBMs and GPOs to ensure their incentives are aligned with systemic stability, and carefully recalibrating new legislation like the Inflation Reduction Act to prevent the unintentional destruction of the competitive generic market.

Simultaneously, the physical supply chain must be fortified. This does not mean a retreat from globalization but a strategic pivot from hyper-concentration to intelligent diversification. Through a combination of targeted onshoring of the most critical medicines, “friend-shoring” with trusted allies, and enhancing the role of the Strategic National Stockpile, the U.S. can build a more redundant and shock-resistant supply network. Public-private partnerships will be essential to de-risk the massive investments required for this transformation.

Finally, the power of technological innovation must be harnessed. Advanced manufacturing and artificial intelligence offer the potential to make domestic production more competitive, enhance quality control, and reduce the costs and risks of drug development, thereby counteracting some of the severe economic pressures that plague the industry.

None of these strategies will succeed in isolation. A resilient generic medicines ecosystem can only be built through a coordinated effort that realigns incentives across the entire value chain. It requires a shared commitment from all stakeholders—manufacturers, payers, providers, intermediaries, and policymakers—to move beyond the short-term allure of the cheapest pill and invest in the long-term security of our nation’s health. The cost of inaction, measured in treatment delays, patient harm, and systemic instability, is far too high to ignore. The time to rebuild the foundation of our essential medicines supply is now.

Works cited

- The Generic Drug Supply Chain | Association for Accessible …, accessed August 3, 2025, https://accessiblemeds.org/resources/blog/generic-drug-supply-chain/

- Trump tariffs to push up US drug prices, won’t change India’s pharma growth playbook: Pharmexcil, accessed August 3, 2025, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/small-biz/trade/exports/insights/trump-tariffs-to-push-up-us-drug-prices-wont-change-indias-pharma-growth-playbook-pharmexcil/articleshow/123041531.cms

- The Global Generic Drug Market: Trends, Opportunities, and …, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-global-generic-drug-market-trends-opportunities-and-challenges/

- Generic Drugs Market Size to Hit USD 775.61 Billion by 2033 – BioSpace, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.biospace.com/press-releases/generic-drugs-market-size-to-hit-usd-775-61-billion-by-2033

- Beneath the Surface: Unravelling the True Value of Generic … – IQVIA, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.iqvia.com/-/media/iqvia/pdfs/library/white-papers/iqvia-true-value-of-generic-medicines-04-24-forweb.pdf

- The Role of Generic Medicines in Sustaining Healthcare … – IQVIA, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.iqvia.com/-/media/iqvia/pdfs/institute-reports/the-role-of-generic-medicines-in-sustaining-healthcare-systems.pdf

- United States Generic Drugs Market Analysis Report – GlobeNewswire, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.globenewswire.com/news-release/2025/05/16/3082896/28124/en/United-States-Generic-Drugs-Market-Analysis-Report-2025-2033-Patent-Expiry-of-Blockbuster-Drugs-Generics-and-Innovator-Drugs-Price-Differential-Dispensing-Incentives-Reimbursement-.html

- Top 10 Challenges in Generic Drug Development …, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/top-10-challenges-in-generic-drug-development/

- Generics 2030: Three strategies to curb the downward spiral, accessed August 3, 2025, https://kpmg.com/us/en/articles/2023/generics-2030-curb-downward-spiral.html

- The Generic Industry Faces External Challenges – Lachman …, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.lachmanconsultants.com/2024/02/the-generic-industry-faces-external-challenges/

- The Impact of Generic Substitution on Health and Economic …, accessed August 3, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4519629/

- Potential Clinical and Economic Impact of Switching Branded …, accessed August 3, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5417581/

- Potential Impact of the IRA on the Generic Drug Market – Lumanity, accessed August 3, 2025, https://lumanity.com/perspectives/potential-impact-of-the-ira-on-the-generic-drug-market/

- How the IRA is impacting the generic drug market | PhRMA, accessed August 3, 2025, https://phrma.org/blog/how-the-ira-is-impacting-the-generic-drug-market

- At a Glance: Key Differences Between Healthcare Group Purchasing …, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.supplychainassociation.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/HSCA-GPO-and-PBM-Comparison.pdf

- FTC and GPOs – BGR Group, accessed August 3, 2025, https://bgrdc.com/2024-02-20-administrative-action-ftc-and-gpos/

- Value of PBMs | PCMA, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.pcmanet.org/value-of-pbms/

- Policy Considerations to Prevent Drug Shortages and Mitigate …, accessed August 3, 2025, https://aspe.hhs.gov/reports/preventing-shortages-supply-chain-vulnerabilities

- Policy Considerations to Prevent Drug Shortages and … – HHS ASPE, accessed August 3, 2025, https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/3a9df8acf50e7fda2e443f025d51d038/HHS-White-Paper-Preventing-Shortages-Supply-Chain-Vulnerabilities.pdf

- Tariff Wars Reveal Pharma Manufacturing Gaps | SYNER-G, accessed August 3, 2025, https://synergbiopharma.com/manufacturing-gaps-us-pharmaceutical-industry-exposed-by-tariff-wars/

- olin.washu.edu, accessed August 3, 2025, https://olin.washu.edu/_assets/docs/research/APIIC-EconomicImpactReport.pdf

- Domestic pharma industry may face setback if US imposes tariffs …, accessed August 3, 2025, https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/business/india-business/domestic-pharma-industry-may-face-setback-if-us-imposes-tariffs/articleshow/123002989.cms

- Pharma downplays 25% tariff impact: US healthcare could feel the …, accessed August 3, 2025, https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/business/india-business/pharma-downplays-25-tariff-impact-us-healthcare-could-feel-the-blow-instead-of-india-what-sector-experts-say/articleshow/123015633.cms

- US drug supply chain exposure to China | Brookings, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/us-drug-supply-chain-exposure-to-china/

- Effects of Geopolitical Strain on Global Pharmaceutical Supply Chain Design and Drug Shortages – arXiv, accessed August 3, 2025, https://arxiv.org/html/2308.07434v2

- From the Pandemic to geopolitical tensions: how risks in the …, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.som.polimi.it/en/from-the-pandemic-to-geopolitical-tensions-how-risks-in-the-pharmaceutical-supply-chain-are-evolving/

- Effects of Geopolitical Strain on Global Pharmaceutical Supply Chain Design and Drug Shortages – arXiv, accessed August 3, 2025, https://arxiv.org/html/2308.07434v3

- PBM Regulations on Drug Spending | Commonwealth Fund, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/explainer/2025/mar/what-pharmacy-benefit-managers-do-how-they-contribute-drug-spending

- Explainer: Pharmacy Benefit Managers and Their Role in Drug …, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.commonwealthfund.org/sites/default/files/2019-04/Explainer_PBMs_1.pdf

- Group Purchasing Organizations (GPOs) Work to Maintain Access to …, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.supplychainassociation.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/gpo_drug_shortage_paper.pdf

- Abbreviated New Drug Application – Wikipedia, accessed August 3, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abbreviated_New_Drug_Application

- Abbreviated New Drug Applications (ANDA) Explained: A Quick-Guide – The FDA Group, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.thefdagroup.com/blog/abbreviated-new-drug-applications-anda

- What is ANDA? – UPM Pharmaceuticals, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.upm-inc.com/what-is-anda

- A Comparative Overview of Generic Drug Regulation in US, Europe …, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.ijdra.com/index.php/journal/article/download/747/396

- A comparison of European and US generic drug markets – GaBIJ, accessed August 3, 2025, https://gabi-journal.net/a-comparison-of-european-and-us-generic-drug-markets.html

- Comparing Generic Drug Markets in Europe and the United States …, accessed August 3, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5594322/

- A Comparative Analysis of Generic Drug Regulations and Pricing Differences in the United States and Other Regions, accessed August 3, 2025, https://jsaer.com/download/vol-6-iss-11-2019/JSAER2019-6-11-315-319.pdf

- Generic Drug Market Entry in Europe: Why a Tailored Approach Is …, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/generic-drug-market-entry-in-europe-why-a-tailored-approach-is-best/

- Medicare Drug Price Negotiations: All You Need to Know …, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/explainer/2025/may/medicare-drug-price-negotiations-all-you-need-know

- Explaining the Prescription Drug Provisions in the Inflation … – KFF, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/explaining-the-prescription-drug-provisions-in-the-inflation-reduction-act/

- The IRA Hurts Generic and Biosimilar Medication Competition …, accessed August 3, 2025, https://accessiblemeds.org/resources/blog/ira-hurts-generic-biosimilar-medication-competition/

- ICYMI: Biden’s Drug Price Controls Kill Innovation and Drive-Up …, accessed August 3, 2025, https://budget.house.gov/press-release/icymi-bidens-drug-price-controls-kill-innovation-and-drive-up-long-term-costs

- The Inflation Reduction Act: A boon for the generic and biosimilar …, accessed August 3, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9828046/

- OPQ White Paper for Quality management Maturity – FDA, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/media/157432/download

- Building a Resilient and Secure Pharmaceutical Supply Chain: The …, accessed August 3, 2025, https://healthpolicy.duke.edu/publications/building-resilient-and-secure-pharmaceutical-supply-chain-role-geographic

- Identifying and addressing vulnerabilities in the upstream medicines …, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.usp.org/supply-chain/build-resilience-and-reduce-drug-shortages

- Regulatory Relief to Promote Domestic Production of Critical …, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/05/regulatory-relief-to-promote-domestic-production-of-critical-medicines/

- Strategic National Stockpile | SNS | HHS/ASPR, accessed August 3, 2025, https://aspr.hhs.gov/SNS/Pages/default.aspx

- The Strategic National Stockpile: Overview and Issues for Congress …, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/R47400

- GAO-24-106260, PUBLIC HEALTH PREPAREDNESS: HHS Should …, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-24-106260.pdf

- Public Health Preparedness: HHS Should Address Strategic … – GAO, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-23-106210

- Scientific Public Private Partnerships and Consortia | FDA, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/science-and-research-drugs/scientific-public-private-partnerships-and-consortia

- Public-Private Partnerships | FDA, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/emergency-preparedness-and-response/innovative-technologies/public-private-partnerships

- Innovations in Generic Drug Manufacturing and Formulation …, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/innovations-in-generic-drug-manufacturing-and-formulation-transforming-products-and-reducing-costs/

- The Future of Medicine: How 3D Printing Is Transforming … – MDPI, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.mdpi.com/1999-4923/17/3/390

- A Review of 3D Printing Technology in Pharmaceutics: Technology …, accessed August 3, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9962448/

- (PDF) A Review of 3D printing methods for pharmaceutical …, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/388831209_A_Review_of_3D_printing_methods_for_pharmaceutical_manufacturing_Technologies_and_applications

- 3D printing of pharmaceuticals for disease treatment – Frontiers, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/medical-technology/articles/10.3389/fmedt.2022.1040052/full

- Artificial Intelligence: On a mission to Make Clinical Drug … – Pfizer, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.pfizer.com/news/articles/artificial_intelligence_on_a_mission_to_make_clinical_drug_development_faster_and_smarter

- Artificial Intelligence for Drug Development | FDA, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/about-fda/center-drug-evaluation-and-research-cder/artificial-intelligence-drug-development

- Generative AI in the pharmaceutical industry | McKinsey, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/life-sciences/our-insights/generative-ai-in-the-pharmaceutical-industry-moving-from-hype-to-reality

- Harnessing Artificial Intelligence in Generic Formulation …, accessed August 3, 2025, https://healthinformaticsjournal.al-makkipublisher.com/index.php/hij/article/download/45/49/536