Introduction: The Battlefield of Billions

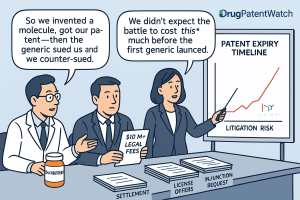

Patent litigation is not merely a legal hurdle; it is a multi-million-dollar crucible where market dominance is forged and fortunes are decided.1 For C-suite executives, general counsel, and intellectual property (IP) strategists, these disputes represent formidable strategic challenges that can divert critical resources, unsettle investors, and derail the entire lifecycle of a blockbuster drug. The central thesis of this report is that managing drug patent litigation is not about “pinching pennies; it’s about strategic capital allocation” and recognizing that “the ability to afford, manage, and strategically deploy litigation is as powerful an asset as the patent itself”.1

The financial stakes are astronomical. For innovator companies, patents represent billions of dollars in protected revenue, while for generic manufacturers, they signify the primary barriers to market entry.2 A single litigation outcome can preserve a blockbuster drug’s exclusivity for years or, conversely, open the floodgates to generic competition, which can lead to a rapid and substantial revenue erosion of 80-90%.2 This dynamic is set against the backdrop of staggering research and development (R&D) costs. The average capitalized cost to develop a new drug is estimated to be as high as $2.6 billion, a figure that accounts for the high rate of failure for drug candidates in clinical trials.1 In this context, the standard 20-year patent term is the essential period during which a company has the opportunity to recoup this massive, high-risk investment.

The entire system of pharmaceutical patent litigation in the United States is built upon a fundamental, government-mandated conflict: the need to incentivize innovation through strong patent protection versus the societal demand for affordable access to medicines through generic competition.5 This report will dissect how this tension is managed, navigated, and strategically exploited through the intricate legal and economic frameworks that govern this unique battlefield. It will provide a comprehensive guide to the rules of engagement, the anatomy of a lawsuit, the core legal arguments, the economic game theory of settlements, and the emerging trends that are shaping the future of this critical industry sector.

Part I: The Rules of Engagement: Foundational Legal Frameworks

The rules of engagement for pharmaceutical patent litigation are primarily defined by two landmark pieces of…source

The Hatch-Waxman Act: The Blueprint for Small-Molecule Drug Litigation

The Grand Bargain: Balancing Innovation and Access

The Hatch-Waxman Act represented a landmark compromise between the interests of innovator pharmaceutical manufacturers and their generic competitors.5 Enacted in 1984, it established the modern generic drug industry by creating a streamlined, abbreviated approval pathway for generic drugs. This allowed generic manufacturers to bring their products to market without repeating the costly and time-consuming clinical trials required for the original brand-name drug.5 In exchange for facilitating generic competition, the Act provided brand-name companies with several crucial benefits, most notably the ability to extend the term of a patent to compensate for time lost during the lengthy Food and Drug Administration (FDA) review process.7 The impact of this legislation was transformative. Before its passage, generic drugs were a rarity, accounting for only 19% of prescriptions in the U.S. Today, they represent more than 90% of all prescriptions filled, a testament to the Act’s success in fostering a competitive marketplace.5

The ANDA Pathway and the Paragraph IV Certification: The “Artificial” Act of Infringement

The cornerstone of the Hatch-Waxman framework is the Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA). This pathway allows a generic manufacturer to seek FDA approval by demonstrating that its product is bioequivalent to an already-approved brand-name drug, thereby relying on the innovator’s original findings of safety and efficacy.1 However, to file an ANDA before the brand’s patents expire, the generic applicant must make a certification for each patent listed by the innovator.

The most consequential of these is the Paragraph IV (PIV) certification. In making a PIV certification, the generic applicant asserts its belief that the innovator’s listed patent is invalid, unenforceable, or will not be infringed by the proposed generic product.1 This declaration is a unique legal construct; under U.S. law, the very act of filing an ANDA with a PIV certification is considered an “artificial” act of patent infringement.1 This legal fiction is the lynchpin of the entire system, as it is specifically designed to trigger a patent infringement lawsuit

before the generic drug is launched. This allows for the orderly resolution of patent disputes without the market disruption and complex damages calculations that would result from an “at-risk” launch, where a generic enters the market while the validity of the brand’s patents is still in question.14 The system is not a sign of failure when litigation occurs; litigation is the intended and primary mechanism for generic entry into the market. This reframes the entire strategic landscape, making litigation an anticipated and budgeted cost of doing business for both innovator and generic companies.

Pillars of the System: The Orange Book, the 30-Month Stay, and the 180-Day Exclusivity “Golden Ticket”

The Hatch-Waxman Act established three critical pillars that structure the litigation process:

- The Orange Book: Officially titled Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations, the Orange Book is an FDA publication that lists approved drugs along with the patents that brand-name companies assert cover their products.5 The FDA’s role in this process is purely ministerial; it lists the patents as submitted by the innovator without independently verifying their validity or scope.16 Despite this, the Orange Book serves as the official registry that defines the patents at issue in any subsequent ANDA litigation.

- The 30-Month Stay: When an innovator company files a patent infringement lawsuit within 45 days of receiving a PIV notice from a generic applicant, an automatic 30-month stay is triggered.9 During this period, the FDA is generally prohibited from granting final approval to the ANDA. This provision provides a critical “time-out” for the parties to litigate their patent dispute while the brand-name drug’s market exclusivity is preserved.2 It is a powerful tool for the brand company, offering a predictable window of protection from generic competition.

- The 180-Day Exclusivity: To incentivize generic companies to undertake the risk and expense of challenging patents, the Hatch-Waxman Act offers a powerful reward: a 180-day period of marketing exclusivity.1 This “golden ticket” is granted to the first generic applicant to file a substantially complete ANDA with a PIV certification. During this six-month period, the FDA cannot approve any other generic versions of the same drug. This limited competition phase is often the most profitable period in a generic product’s lifecycle, with prices typically only 15-25% below the brand price, and can be worth hundreds of millions of dollars for a blockbuster drug.2

The BPCIA: A Different Dance for Biologics and Biosimilars

Recognizing that complex, large-molecule biologic drugs could not be perfectly replicated in the same way as small-molecule chemical drugs, Congress enacted the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act of 2009 (BPCIA) as part of the Affordable Care Act.22 The BPCIA created an abbreviated approval pathway for “biosimilars”—products that are highly similar to, with no clinically meaningful differences from, an existing FDA-approved biologic (the “reference product”).

The aBLA and the “Patent Dance”

Under the BPCIA, a biosimilar developer files an Abbreviated Biologic License Application (aBLA).26 Instead of the straightforward PIV certification process, the BPCIA establishes a highly structured, multi-step process of information exchange known as the “patent dance”.1 This intricate series of communications requires the biosimilar applicant to provide its aBLA and manufacturing information to the reference product sponsor. The parties then exchange lists of patents they believe could be infringed and their positions on validity and infringement, with the goal of identifying and narrowing the patents that will be the subject of litigation.

Key Distinctions from Hatch-Waxman

The BPCIA framework contains several critical differences from the Hatch-Waxman Act, fundamentally altering the strategic dynamics of litigation:

- Data Exclusivity: Innovator biologics are granted a 12-year period of data exclusivity from the date of FDA approval, during which the FDA cannot approve a biosimilar application.22 This is significantly longer than the five years of exclusivity granted to new chemical entities under Hatch-Waxman.

- No Automatic Stay: Perhaps the most significant distinction is the absence of an automatic 30-month stay of regulatory approval.1 If a brand company wishes to prevent a biosimilar from launching after the 12-year exclusivity period ends, it cannot rely on an automatic stay. Instead, it must go to court and seek a preliminary injunction, a much higher legal bar to clear that requires demonstrating a likelihood of success on the merits, the prospect of irreparable harm, and that the balance of hardships and public interest favor an injunction. This absence of an automatic stay creates greater urgency for the brand company and shifts the strategic leverage in biosimilar disputes.

The following tables provide a comparative overview of these two foundational legal frameworks and the key regulatory exclusivities that shape the competitive landscape.

| Feature | Hatch-Waxman Act (Small Molecules) | Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA) | |

| Follow-on Product | Generic Drug (bioequivalent) | Biosimilar or Interchangeable Biologic (highly similar) | |

| Application Type | Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) | Abbreviated Biologic License Application (aBLA) | |

| Litigation Trigger | Filing an ANDA with a Paragraph IV certification, an “artificial” act of infringement. | Can arise from the “patent dance” or a notice of commercial marketing. | |

| Information Exchange | Generic provides a notice letter with the basis for its patent challenge. | A highly structured, multi-step “patent dance” to exchange patent lists and contentions. | |

| Automatic Stay of Approval | Yes. A lawsuit filed within 45 days triggers an automatic 30-month stay of FDA approval. | No. The innovator must seek a preliminary injunction from a court to block a launch. | |

| Innovator Exclusivity | 5 years for a New Chemical Entity (NCE); 3 years for new clinical investigations. | 12 years of data exclusivity from the date of the reference product’s approval. | |

| Follow-on Exclusivity | 180 days for the first successful Paragraph IV challenger. | 1 year for the first biosimilar deemed “interchangeable” with the reference product. | |

| Data Sources: 1 |

| Exclusivity Type | Description | Duration | Applicable To | |

| New Chemical Entity (NCE) | Granted to a drug containing an active ingredient never previously approved by the FDA. | 5 Years | Brand-name small-molecule drugs | |

| New Clinical Investigation | Granted for a new use or other significant change to a previously approved drug, supported by new clinical studies. | 3 Years | Brand-name small-molecule drugs | |

| Orphan Drug | Granted to a drug that treats a rare disease or condition (affecting <200,000 people in the U.S.). | 7 Years | Brand-name drugs and biologics | |

| Pediatric | Granted as an extension for conducting pediatric studies requested by the FDA. | 6 Months (added to existing patents/exclusivities) | Brand-name drugs and biologics | |

| GAIN (Antibiotics) | Granted for a “Qualified Infectious Disease Product” to incentivize antibiotic development. | 5 Years (added to other exclusivities) | Brand-name drugs and biologics | |

| 180-Day Generic | Granted to the first generic applicant to file a successful Paragraph IV patent challenge. | 180 Days | Generic drugs (ANDAs) | |

| Biologics Data Exclusivity | A period during which the FDA cannot approve a biosimilar application based on the innovator’s data. | 12 Years | Brand-name biologics | |

| Data Sources: 7 |

Part II: The Anatomy of a Lawsuit: A Step-by-Step Procedural Guide

Navigating a pharmaceutical patent lawsuit requires a deep understanding of its distinct phases, each presenting unique strategic opportunities and challenges. The process is a meticulously choreographed sequence of events, from pre-litigation intelligence gathering to the final appellate review.

Pre-Litigation: Setting the Board

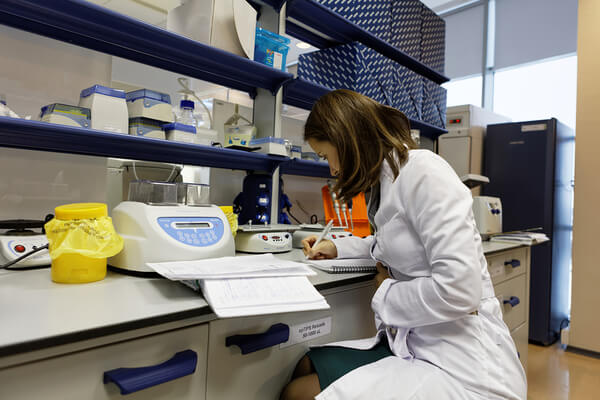

Successful litigation begins long before a complaint is filed. This preparatory phase is where the strategic foundation for the entire case is laid.

For Generics: Proactive Intelligence Gathering

For a generic or biosimilar company, the pre-litigation phase is an exercise in comprehensive due diligence and risk assessment.

- Freedom-to-Operate (FTO) Analysis: The FTO analysis is the indispensable first step for any potential challenger.29 It is a formal legal assessment conducted by patent attorneys to determine whether a proposed product or manufacturing process might infringe on any third-party patents in a specific market.29 This analysis should be initiated at the earliest possible stage of development to avoid investing significant resources in a product that cannot be legally marketed.30 A thorough FTO involves defining the scope of the analysis by both geography (e.g., U.S., Europe) and product attributes (e.g., formulation, dosage), identifying all relevant patents, and assessing the risk posed by each one.30 The cost of an FTO can range from $10,000 for a preliminary search to over $100,000 for a comprehensive global analysis.30

- Patent Landscape Analysis: While an FTO analysis is defensive, a patent landscape analysis is a broader, more offensive strategic tool.35 It involves mapping the patent activity within a specific technological or therapeutic area to identify trends, understand the strategies of key competitors, and uncover “whitespace”—areas with little patent activity that may represent opportunities for innovation.36 This analysis provides valuable competitive intelligence, revealing the R&D focus of rival firms and informing the generic company’s own portfolio decisions.36

- Using Competitive Intelligence Platforms: Specialized platforms like DrugPatentWatch have become essential tools for modern pre-litigation strategy.2 These services aggregate and analyze vast amounts of data, allowing companies to monitor patent expirations, track ongoing litigation outcomes, identify first-time generic entrants, and gain early insights into the R&D pipelines of competitors. This transforms raw data into actionable intelligence that can guide strategic decisions on which products to develop and which patents to challenge.

For Innovators: Building a Defensive Fortress

For the brand-name company, the pre-litigation phase is about constructing an IP fortress designed to deter or defeat challenges.

- The “Patent Thicket”: A core defensive strategy is the creation of a “patent thicket”—a dense, overlapping web of patents covering a single drug product.3 This goes far beyond patenting the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API). Innovators strategically file secondary patents on every conceivable aspect of the product, including different formulations, methods of use for various indications, manufacturing processes, crystalline forms (polymorphs), and delivery devices.47 The goal is to create a formidable barrier that significantly increases the cost, time, and complexity for a generic challenger, who must now navigate or invalidate dozens of patents instead of just one.3 The strategy employed by AbbVie to protect its blockbuster drug Humira, which involved over 100 patents, is the canonical example of this approach.3

- Drafting Litigation-Resilient Patents: The strength of the fortress depends on the quality of its walls. Proactive innovators invest in drafting patents designed to withstand the rigors of litigation. This involves a multi-layered claiming strategy, with broad independent claims to capture the core invention and a series of narrower, dependent claims that provide fallback positions if the broader claims are invalidated.1 The language used must be clear, precise, and internally consistent to avoid ambiguity during claim construction.1

The Trigger: The Paragraph IV Notice and the 45-Day Countdown

The formal litigation process is initiated when the generic applicant sends its PIV notice letter to the brand-name drug company and any patent holders.13 This notice must be sent within 20 days of the FDA acknowledging that the ANDA is sufficiently complete for review, and it must provide a detailed statement of the factual and legal bases for the generic’s assertion that the patent is invalid or not infringed.19

The receipt of this letter starts a critical 45-day clock.12 The innovator must decide within this compressed timeframe whether to file a patent infringement lawsuit. This tight deadline necessitates that both sides maintain a state of “perpetual litigation readiness,” with pre-vetted legal teams and organized documentation.15 If the innovator files suit within the 45-day window, the powerful 30-month stay of FDA approval is automatically triggered, and the chess match officially begins.12

The Discovery Phase: Uncovering the Evidence

Once a lawsuit is filed, the parties enter the discovery phase, which is the formal process of exchanging information and evidence.

Scope and Strategy

Discovery in U.S. patent litigation is notoriously broad, allowing parties to request any non-privileged information that is relevant to the claims or defenses in the case.53 The primary tools of discovery include:

- Document Production: This involves the exchange of potentially millions of pages of documents, including internal emails, lab notebooks, R&D reports, marketing plans, and complete regulatory filings, such as the generic’s ANDA submission.1

- Depositions: Attorneys conduct oral examinations of key witnesses, including the patent’s inventors, company scientists, and business executives, under oath. The testimony is transcribed and can be used as evidence at trial.1

- Interrogatories and Requests for Admission: These are written tools used to obtain specific information and to force the opposing party to admit or deny certain facts, which helps to narrow the issues that must be proven at trial.53

The E-Discovery Challenge

In the modern era, the vast majority of discoverable information is electronically stored information (ESI). The sheer volume of ESI in a typical pharmaceutical case—spanning years of research, clinical trials, and regulatory correspondence—makes electronic discovery (e-discovery) a massive and costly undertaking.1 Managing this process effectively requires sophisticated software, often powered by artificial intelligence and predictive coding, to search, review, and produce relevant documents while protecting privileged information. The costs associated with e-discovery can run into the millions of dollars and represent a significant portion of the overall litigation budget.1

The Markman Hearing: The Battle for Meaning

Perhaps the most critical juncture in a patent lawsuit is the Markman hearing, or claim construction hearing.56 In this pivotal pre-trial proceeding, the judge—acting as a legal arbiter, not a fact-finder—determines the precise meaning and scope of disputed terms within the patent’s claims. This process is named after the Supreme Court case

Markman v. Westview Instruments, Inc., which established that claim construction is a question of law for the court to decide.60

The outcome of the Markman hearing is often case-dispositive. A broad interpretation of a claim term may make it easy for the patent holder to prove infringement, while a narrow interpretation may allow the generic product to fall outside the patent’s scope, leading to a judgment of non-infringement.56 Because the court’s claim construction ruling sets the legal boundaries for the rest of the case, the battle over the meaning of a few key words is frequently where the litigation is won or lost. In this analysis, courts give the most weight to “intrinsic evidence”—the patent’s claims, its written description (specification), and its prosecution history at the patent office. “Extrinsic evidence,” such as expert testimony or technical dictionaries, is considered secondary and cannot be used to contradict the meaning derived from the intrinsic record.59 The Supreme Court’s decision in

Teva Pharmaceuticals v. Sandoz further clarified that while the ultimate interpretation of a claim is a legal question reviewed afresh on appeal, any underlying factual determinations made by the district court judge during this process are given deference.60 This front-loads the most critical strategic battle of the litigation, meaning the largest investment of legal and expert resources is often focused on this single, pre-trial event.

Trial and Judgment: Presenting the Case

If the case is not resolved by settlement or summary judgment after the Markman hearing, it proceeds to trial. The vast majority of ANDA cases are bench trials, meaning they are decided by a judge rather than a jury.15 Trial strategy, therefore, focuses on educating the judge on complex technical issues through clear expert testimony and concise legal arguments.15 Expert witnesses in fields such as medicinal chemistry, pharmacology, and patent law are indispensable for explaining the science and legal standards to the court.1

The Final Word: The Role of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit

Regardless of the outcome at the district court, the losing party almost invariably appeals the decision. All patent appeals in the United States are heard exclusively by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit in Washington, D.C..56 Congress created the Federal Circuit in 1982 with the express purpose of promoting uniformity and consistency in patent law, eliminating the problem of different regional appellate courts issuing conflicting rulings on the same legal issues.65 As a result, the Federal Circuit is the ultimate arbiter of patent law in the U.S. (short of the Supreme Court), and its vast body of precedent governs how patent cases are litigated and decided in the district courts below.65

Part III: The Art of War: Core Legal Arguments and Defenses

Pharmaceutical patent litigation revolves around two central questions: does the generic product infringe a valid patent, and is the patent itself legally valid? The innovator bears the burden of proving infringement, while the generic challenger bears the burden of proving invalidity.

The Innovator’s Case: Proving Infringement

The patent holder’s primary objective is to demonstrate that the proposed generic product falls within the scope of at least one of its asserted patent claims. This is typically argued on two fronts.

Literal Infringement

Literal infringement is the most straightforward path to proving a case. The innovator must show that the accused generic product contains each and every element, or limitation, exactly as recited in a patent claim.69 This analysis is performed by comparing the features of the generic product to the claim language as interpreted by the court during the

Markman hearing.

The Doctrine of Equivalents: An Essential Second Line of Attack

If a generic product does not literally infringe a patent claim—perhaps because of a minor, trivial modification—the innovator can still prevail under the judicially created “doctrine of equivalents”.71 This doctrine is designed to prevent a competitor from stealing the benefit of an invention by making insubstantial changes that avoid the literal language of the claims.73 The classic test for equivalence, established in the Supreme Court case

Graver Tank & Mfg. Co. v. Linde Air Products Co., asks whether a component of the accused product performs substantially the same function, in substantially the same way, to achieve substantially the same result as the claimed element.72 This doctrine ensures that patent protection extends beyond the precise wording of the claims to cover true equivalents.

The Generic’s Counter-Offensive: Challenging Patent Validity

In addition to arguing non-infringement, the generic company’s primary strategy is to launch a counter-offensive aimed at invalidating the innovator’s patent(s). A patent granted by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) is presumed valid, but this presumption can be overcome with clear and convincing evidence.

Anticipation (Lack of Novelty – § 102)

Anticipation is the most direct validity challenge. It argues that the invention is not new. To prove anticipation, the challenger must show that every single element of the claimed invention was disclosed in a single prior art reference (such as a previously published patent, scientific article, or public presentation) that existed before the patent was filed.50

Obviousness (Lack of Inventive Step – § 103)

Obviousness is by far the most common, complex, and frequently successful ground for invalidating a drug patent.50 This argument does not require a single prior art reference to disclose the entire invention. Instead, it asserts that the differences between the claimed invention and the existing prior art are such that the invention as a whole would have been obvious at the time to a “Person Having Ordinary Skill in the Art” (PHOSITA).2

The legal standard for obviousness was significantly impacted by the 2007 Supreme Court decision in KSR International Co. v. Teleflex Inc. This ruling rejected a rigid requirement for an explicit “teaching, suggestion, or motivation” to combine prior art references. Instead, the Court adopted a more flexible and common-sense approach, making it easier to argue that an invention was “obvious to try”—for example, if there was a known problem in the field and a finite number of identified, predictable solutions available to researchers.75 To counter an obviousness challenge, innovators can present “secondary considerations” or objective evidence of non-obviousness, such as the invention’s unexpected and superior results, its commercial success, or evidence that others in the field tried and failed to achieve the same result.50

Enablement and Written Description (§ 112)

A patent is a bargain with the public: in exchange for a limited monopoly, the inventor must fully disclose the invention. The enablement and written description requirements of 35 U.S.C. § 112 enforce this bargain. A patent must describe the invention in sufficient detail to enable a PHOSITA to make and use it without “undue experimentation”.74 The 2023 Supreme Court decision in

Amgen Inc. v. Sanofi strongly affirmed a stringent standard for enablement, particularly for patents claiming a broad genus of antibodies. The Court held that merely providing a roadmap for discovering the claimed embodiments is not enough; the patent must enable the full scope of what it claims. Justice Gorsuch articulated the core principle: “the more you claim, the more you must enable”.1 This ruling has made it significantly more difficult to obtain and defend broad patent claims in the biopharmaceutical space.

The evolving legal standards for both obviousness and enablement have created a formidable challenge for innovator companies. The KSR decision weakened the patentability of many incremental innovations, such as new formulations or dosing regimens, by making them more susceptible to an “obvious to try” attack. Simultaneously, the Amgen decision raised the bar for defending broad, pioneering claims covering entire classes of compounds. This has created a strategic imperative for innovators to shift away from relying on a single, broad patent, which now represents a high-risk single point of failure. Instead, the modern strategy is a direct response to this heightened vulnerability: build a defensive “patent thicket” composed of numerous, narrower, and more easily defensible patents covering every aspect of a drug. This forces a challenger into a war of attrition, needing to overcome dozens of patents rather than a single one, thereby making the legal challenge economically prohibitive.3

Other Defenses

Other common defenses include arguing that the invention constitutes patent-ineligible subject matter under 35 U.S.C. § 101 (e.g., claiming a law of nature), that the patent fails to name the correct inventors, or that the patent is unenforceable due to “inequitable conduct”—a serious charge that the patentee intentionally misled or deceived the USPTO during the patent application process.50

Part IV: The Economic Game Theory: Settlements, Costs, and Antitrust Scrutiny

The decision to litigate or settle a pharmaceutical patent case is a complex calculation driven by economic game theory, asymmetric risk, and intense regulatory scrutiny. Understanding these financial drivers is essential to grasping the strategic motivations of both innovator and generic companies.

The Economics of Settlement: Risk, Reward, and “Pay-for-Delay”

Asymmetric Risks

In Hatch-Waxman litigation, the financial risks are profoundly asymmetric. The brand-name innovator stands to lose a blockbuster revenue stream that can be worth billions of dollars annually. The generic challenger, in contrast, has not yet launched a product and therefore has no revenue to lose; its primary risk is the cost of the litigation itself, typically several million dollars.79 This imbalance creates a powerful dynamic where the brand is inherently risk-averse, while the generic is risk-seeking. For the generic, a multi-million dollar legal bill is a calculated investment for a chance to win access to a multi-billion dollar market. For the brand, even a small probability of losing in court represents an unacceptable financial catastrophe. This asymmetry creates a strong economic incentive for the brand to settle the litigation to eliminate the risk of an adverse court ruling.79

“Pay-for-Delay” / Reverse Payment Settlements

This economic dynamic gave rise to a controversial type of settlement known as a “pay-for-delay” or “reverse payment” agreement.79 In these arrangements, the brand-name company pays the generic challenger to settle the lawsuit and agree to delay the launch of its generic product until a specified future date.79 The payment is termed a “reverse” payment because, counterintuitively, it flows from the patent holder (the plaintiff) to the alleged infringer (the defendant).82

The FTC’s Scrutiny and FTC v. Actavis

The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) has long viewed these settlements as anticompetitive agreements to divide a monopoly profit, arguing that they harm consumers by keeping lower-cost generics off the market.83 The FTC estimates that such deals cost consumers and taxpayers $3.5 billion annually in higher drug costs.85 This issue culminated in the landmark 2013 Supreme Court decision,

FTC v. Actavis, Inc. The Court rejected the notion that such settlements were immune from antitrust law as long as the delay did not extend beyond the patent’s expiration date. Instead, it held that large and unjustified reverse payments could violate antitrust laws and must be evaluated under a “rule of reason” analysis, which weighs the pro-competitive benefits against the anticompetitive harms.83

Modern Settlements: The Shift from Cash to Complex “Possible Compensation”

The Actavis decision fundamentally changed the settlement landscape. While the underlying economic incentives to settle remain, explicit cash payments from brand to generic have become far less common due to the high risk of antitrust litigation.93 Instead, the value transfer has been driven underground, with settlements now featuring more complex and subtle forms of “possible compensation.” The FTC actively scrutinizes these arrangements, which can include valuable side deals, such as a brand’s promise not to launch its own “authorized generic” (a “no-AG” agreement), favorable co-promotion or licensing agreements, or agreements that impose restrictions on the quantity of the generic product that can be sold.90 This has not eliminated the practice of settling but has shifted the legal battleground from patent law to the intricate antitrust analysis of these non-cash value transfers.

The Financial Calculus: Weighing Litigation Costs Against Market Exclusivity

The decision to engage in a protracted legal battle is a rational economic calculation based on the immense value of market exclusivity.

Litigation Expenses

Pharmaceutical patent litigation is one of the most expensive forms of commercial litigation. For cases with more than $25 million at risk—a common scenario for a profitable drug—the median total cost through trial and appeal is approximately $4 million, with some estimates placing it even higher.1 These direct costs include legal fees from specialized law firms where top partners can charge over $1,200 per hour, fees for indispensable expert witnesses, and massive e-discovery expenses.1 The table below, based on industry survey data, provides a concrete look at these costs.

| Amount at Risk | Median Cost Through Discovery & Claim Construction (USD) | Median Total Cost Through Trial & Appeal (USD) | |

| $1 Million – $10 Million | $600,000 | $1,500,000 | |

| $10 Million – $25 Million | $1,225,000 | $2,700,000 | |

| More than $25 Million | $2,375,000 | $4,000,000 | |

| Data Source: 1 |

Value of Exclusivity

While these litigation costs are substantial, they are often dwarfed by the revenue at stake. A blockbuster drug can generate billions of dollars in sales annually during its period of market exclusivity.1 Extending that exclusivity, even for a short period, can be worth hundreds of millions of dollars.2 Therefore, spending several million dollars on litigation to protect a multi-billion dollar revenue stream is a sound and rational business decision for an innovator company.1

The “Patent Cliff”

The term “patent cliff” vividly describes the dramatic and precipitous decline in a drug’s revenue—often by 80-90%—that occurs upon patent expiration and the subsequent entry of multiple generic competitors.3 Upon generic entry, drug prices can fall significantly, with studies showing a median price decrease of 41% after four years 97, and some dropping by as much as 90% when multiple generics enter the market.2 The looming threat of the patent cliff is the single most powerful economic driver behind innovators’ aggressive litigation and settlement strategies aimed at delaying generic entry for as long as possible.40

Part V: The Global Arena and the Future Frontier

While the United States remains the largest and most lucrative pharmaceutical market, patent litigation is an increasingly global affair. Understanding the divergent legal systems in other key jurisdictions is critical for any company with international operations. Simultaneously, emerging technologies and evolving policy debates are reshaping the future of the litigation landscape.

A Comparative Look at International Litigation

The European Union and the Unified Patent Court (UPC)

Historically, patent enforcement in Europe was a fragmented and costly endeavor, requiring separate lawsuits in the national court of each country where a European patent was validated.99 This changed dramatically with the launch of the Unified Patent Court (UPC) in June 2023. The UPC is a revolutionary international court that provides a single venue for patent litigation with effect across all 17 participating EU member states.100

The UPC offers the promise of faster, more efficient, and pan-European enforcement of patent rights. A single ruling from the UPC can grant an injunction that is effective across a market of roughly 300 million people.102 However, this efficiency is a double-edged sword: a single revocation action at the UPC can invalidate a patent across all member states simultaneously, representing a high-risk, “all-or-nothing” proposition.100 The life sciences sector, though initially cautious, has become a significant user of the new court, and the UPC’s early decisions are rapidly shaping the future of European patent litigation.100

China’s Patent Linkage System

Recognizing the need to balance innovation and generic access, China implemented its own pharmaceutical patent linkage system in 2021.107 Analogous to the U.S. system, it includes a patent registration platform (similar to the Orange Book), a declaration system for generic applicants (similar to Paragraph IV certifications), a 45-day window for the patent holder to file a lawsuit, and a 9-month stay of regulatory approval for the generic drug.107 China’s specialized IP courts are known for their efficiency, often resolving cases within 12 months.107 However, significant procedural differences remain, most notably the lack of a U.S.-style discovery process, which places a greater burden on the parties to gather evidence independently.107

India’s Pro-Generic Framework

India’s pharmaceutical patent system stands in stark contrast to those of the U.S., EU, and China. Its legal framework is notable for the deliberate absence of a formal patent linkage system; the patent office and the drug regulatory authority operate entirely independently.116 Furthermore, Indian patent law sets a uniquely high bar for patenting so-called “secondary” or incremental inventions. Section 3(d) of the Indian Patents Act prohibits the patenting of a new form of a known substance unless it demonstrates a significant “enhancement of the known efficacy”.117 This provision was famously upheld by the Indian Supreme Court in the landmark case

Novartis AG v. Union of India, which denied a patent for the beta-crystalline form of the cancer drug imatinib mesylate (Glivec).117 This strict standard, combined with broad provisions for compulsory licensing, has cemented India’s role as the “pharmacy of the world” and a global powerhouse in generic drug manufacturing.116

The global pharmaceutical litigation landscape is undergoing a strategic bifurcation. The U.S. system, with its permissive patenting standards and procedural tools like the 30-month stay, continues to structurally encourage the creation and defense of patent thickets in lengthy, expensive litigation. In contrast, the new centralized and rapid systems in Europe (UPC) and China offer efficient, though high-risk, alternatives for resolving multi-jurisdictional disputes. This divergence creates new strategic considerations for global pharmaceutical companies, who may now choose to litigate a key patent first in a faster jurisdiction like the UPC to obtain a broad-reaching decision that can influence subsequent settlement negotiations or litigation in the slower U.S. system.

| Feature | United States | European Union (UPC) | China | India | |

| Central Litigation Forum | Federal District Courts, with appeals to the Federal Circuit. | Unified Patent Court (UPC) for participating states. | Specialized IP Courts (e.g., Beijing, Shanghai) and the Supreme People’s Court. | High Courts (with new specialized IP Divisions). | |

| Patent Linkage System | Yes (Hatch-Waxman Act). | No formal linkage; regulatory and patent systems are separate. | Yes (implemented in 2021). | No. Patent and drug approval systems are separate. | |

| Pre-Launch Injunction/Stay | Automatic 30-month stay for small molecules; preliminary injunction required for biologics. | Preliminary injunctions available, but no automatic stay. | 9-month stay of generic approval upon timely lawsuit. | No automatic stay; preliminary injunctions may be sought in court. | |

| Data Exclusivity | 5 years (small molecules); 12 years (biologics). | 8 + 2 + 1 years. | Under consideration; currently no formal system. | No formal data exclusivity. | |

| Standard for Secondary Patents | Relatively permissive (non-obviousness standard). | Stricter “inventive step” standard. | Stricter than U.S. | Very strict; requires “enhancement of known efficacy” (Section 3(d)). | |

| Litigation Speed | Slow (24-36 months to trial is common). | Fast (target of ~12 months to first instance decision). | Fast (~12 months is common). | Variable, but new IP Divisions aim to accelerate. | |

| Key Strategic Consideration | Navigating patent thickets and high litigation costs. | High-risk, high-reward central enforcement or revocation. | Navigating a fast-paced system with limited discovery. | Overcoming a high bar for patentability and lack of linkage. | |

| Data Sources: 48 |

Emerging Trends Shaping the Future of Litigation

The strategic landscape of pharmaceutical patent litigation is not static. It is continuously being reshaped by scientific advancement, technological innovation, and evolving public policy.

The New Frontier: Patenting and Litigating Cell and Gene Therapies (CGTs)

Cell and gene therapies (CGTs), such as CAR-T cell therapies, represent a revolutionary new paradigm in medicine, but they also present profound and novel challenges for the patent system.77 Unlike traditional chemical drugs, these therapies involve living biological materials and highly complex, patient-specific manufacturing processes.126 This raises difficult legal questions regarding:

- Patent Eligibility: Determining whether modified human cells or isolated genes are patentable subject matter or unpatentable products of nature.125

- Enablement: Adequately describing these complex and variable therapies in a patent application to enable a skilled person to reproduce them without undue experimentation is a significant hurdle.77

- The “Safe Harbor” Exemption: The scope of the statutory “safe harbor” (35 U.S.C. § 271(e)(1)), which protects certain research activities from infringement liability, is being actively litigated in the context of CGT research tools and manufacturing components.125

- Competition: The sheer complexity and high cost of CGTs create formidable intellectual property and manufacturing barriers that could significantly hinder the development of future biosimilar-like competitors, raising new questions about long-term access and affordability.124

The Rise of AI: Predicting Outcomes and Managing Costs

Artificial intelligence (AI) is rapidly emerging as a transformative tool in patent litigation, moving from a futuristic concept to a practical strategic asset.132

- Outcome Prediction and Cost Management: Sophisticated AI platforms can now analyze vast datasets of past court decisions, judge-specific ruling patterns, and patent prosecution histories to provide predictive analytics on the likelihood of success in a given case.136 AI-powered tools are also being used to more accurately forecast and manage the substantial costs of litigation.138

- Strategic Analysis: AI is dramatically enhancing the efficiency and power of legal research and analysis. AI tools can conduct comprehensive prior art searches in minutes that would take humans weeks, automate the review of millions of documents in e-discovery, and identify subtle patterns in complex litigation data, freeing up legal teams to focus on high-level strategy.136

- Inventorship Challenges: The increasing use of AI in the drug discovery process itself is creating novel legal challenges. Current U.S. patent law requires an inventor to be a human being, as affirmed in the Federal Circuit case Thaler v. Vidal. As AI’s role in conceiving of new molecules and therapies grows, complex questions will arise regarding who, if anyone, can be legally named as an inventor, potentially threatening the patentability of AI-driven discoveries.142

The Evolving Policy Landscape

Finally, the entire field of pharmaceutical patent law operates under the shadow of intense public and political scrutiny over high drug prices. Lawmakers and federal agencies, including the USPTO and FDA, are actively exploring and implementing policy changes aimed at curbing perceived abuses of the patent system, such as the creation of “patent thickets” and the practice of “evergreening” (obtaining secondary patents to extend a drug’s monopoly).4 This ongoing policy debate will continue to shape the legal and regulatory environment, potentially altering the strategic calculus for both innovator and generic companies in the years to come.

Conclusion: Litigation as a Strategic Imperative

Navigating the complex world of pharmaceutical patent litigation demands a paradigm shift in thinking. It is not a reactive legal exercise to be managed in isolation by the legal department, but a proactive, C-suite-level strategic function that is central to a company’s survival and success.1 The evidence and analysis presented in this report demonstrate that achieving a favorable outcome requires the seamless integration of sophisticated legal expertise, deep scientific understanding, rigorous economic modeling, and cutting-edge competitive intelligence.2

The modern playbook for innovators involves meticulously constructing robust, multi-layered patent portfolios—or “thickets”—designed to withstand the inevitable challenges that are an intended feature of the legal framework. For generic and biosimilar manufacturers, success hinges on conducting rigorous pre-litigation intelligence, including Freedom-to-Operate and patent landscape analyses, to identify vulnerabilities and chart the most efficient path to market. For both sides, the litigation process itself is a strategic chess match, where procedural milestones like the Markman hearing often prove more decisive than the final trial, and where sophisticated economic calculations about risk and reward drive complex settlement negotiations under the watchful eye of antitrust regulators.

The landscape is in a constant state of flux. The rise of revolutionary technologies like cell and gene therapies and artificial intelligence is introducing novel legal questions that will be litigated for years to come. Simultaneously, the establishment of powerful and efficient international forums, most notably the Unified Patent Court in Europe, is reshaping global litigation strategy. All of this unfolds against a backdrop of persistent policy pressure to balance the need for innovation with the demand for affordable medicines. In this high-stakes, dynamic environment, the ability to anticipate these changes and master the intricate art of patent litigation is no longer just a legal capability; it is an indispensable component of business strategy and a powerful source of durable competitive advantage.

Works cited

- Managing Drug Patent Litigation Costs: A Strategic Playbook for the …, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/managing-drug-patent-litigation-costs/

- 5 Ways to Predict Patent Litigation Outcomes – DrugPatentWatch …, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/5-ways-to-predict-patent-litigation-outcomes/

- Patent Defense Isn’t a Legal Problem. It’s a Strategy Problem. Patent Defense Tactics That Every Pharma Company Needs – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/patent-defense-isnt-a-legal-problem-its-a-strategy-problem-patent-defense-tactics-that-every-pharma-company-needs/

- Patents and Drug Pricing: Why Weakening Patent Protection Is Not in the Public’s Best Interest – American Bar Association, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.americanbar.org/groups/intellectual_property_law/resources/landslide/2025-spring/drug-pricing-weakening-patent-protection-not-best-interest/

- 40th Anniversary of the Generic Drug Approval Pathway | FDA, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/cder-conversations/40th-anniversary-generic-drug-approval-pathway

- What is Hatch-Waxman? – PhRMA, accessed August 7, 2025, https://phrma.org/resources/what-is-hatch-waxman

- Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act – Wikipedia, accessed August 7, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Drug_Price_Competition_and_Patent_Term_Restoration_Act

- Leveling the Playing Field—The Role of Venture Capital in Hatch–Waxman Act Patent Litigation, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.bartonesq.com/pdf/PDFArtic.pdf

- Hatch-Waxman Act – Practical Law, accessed August 7, 2025, https://uk.practicallaw.thomsonreuters.com/Glossary/PracticalLaw/I2e45aeaf642211e38578f7ccc38dcbee

- How Patent Litigation Influences Drug Approvals and Market Entry | PatentPC, accessed August 7, 2025, https://patentpc.com/blog/how-patent-litigation-influences-drug-approvals-and-market-entry

- Mastering Paragraph IV Certification – Number Analytics, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.numberanalytics.com/blog/mastering-paragraph-iv-certification

- Paragraph IV Explained – ParagraphFour.com, accessed August 7, 2025, https://paragraphfour.com/paragraph-iv-explained/

- What Every Pharma Executive Needs to Know About Paragraph IV Challenges, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/what-every-pharma-executive-needs-to-know-about-paragraph-iv-challenges/

- Drug Pricing and the Law: Pharmaceutical Patent Disputes – Congress.gov, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/IF11214

- ANDA Litigation: Strategies and Tactics for Pharmaceutical Patent …, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/anda-litigation-strategies-and-tactics-for-pharmaceutical-patent-litigators/

- Patents and Exclusivities for Generic Drug Products | FDA, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/cder-conversations/patents-and-exclusivities-generic-drug-products

- Distinguishing Patent Protection from Patient Safety – A Role for the FDA | Mintz, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.mintz.com/insights-center/viewpoints/2231/2023-08-21-distinguishing-patent-protection-patient-safety-role-fda

- The timing of 30‐month stay expirations and generic entry: A cohort …, accessed August 7, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8504843/

- Intricacies of the 30-Month Stay in Pharmaceutical Patent Cases | Articles – Finnegan, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.finnegan.com/en/insights/articles/intricacies-of-the-30-month-stay-in-pharmaceutical-patent-cases.html

- Hatch-Waxman 201 – Fish & Richardson, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.fr.com/insights/thought-leadership/blogs/hatch-waxman-201-3/

- Hatch-Waxman Litigation 101: The Orange Book and the Paragraph IV Notice Letter, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.dlapiper.com/en/insights/publications/2020/06/ipt-news-q2-2020/hatch-waxman-litigation-101

- Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.dpc.senate.gov/healthreformbill/healthbill70.pdf

- Commemorating the 15th Anniversary of the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/cder-conversations/commemorating-15th-anniversary-biologics-price-competition-and-innovation-act

- An unofficial legislative history of the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act of 2009 – PubMed, accessed August 7, 2025, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24479247/

- Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act of 2009 – Wikipedia, accessed August 7, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Biologics_Price_Competition_and_Innovation_Act_of_2009

- Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act: Striking a Delicate Balance Between Innovation and Accessibility – University of Minnesota, accessed August 7, 2025, https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1074&context=mjlst

- Patents and Exclusivity | FDA, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/media/92548/download

- How to manage FTO for Pharmaceutical Industry?, accessed August 7, 2025, https://blog.logicapt.com/fto-in-pharmaceutical-industry/

- IP: Writing a Freedom to Operate Analysis – InterSECT Job Simulations, accessed August 7, 2025, https://intersectjobsims.com/library/fto-analysis/

- Conducting a Biopharmaceutical Freedom-to-Operate (FTO …, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/conducting-a-biopharmaceutical-freedom-to-operate-fto-analysis-key-considerations-for-generic-drug-stability-testing/

- Freedom to Operate Definition, Importance & Next Steps – Dilworth IP, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.dilworthip.com/resources/news/freedom-to-operate/

- How to Conduct a Drug Patent FTO Search: A Strategic and Tactical …, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/how-to-conduct-a-drug-patent-fto-search/

- FTO Analysis Impacts Stability Testing for Generic Drug Manufacturers Seeking Market Entry, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.geneonline.com/fto-analysis-impacts-stability-testing-for-generic-drug-manufacturers-seeking-market-entry/

- How to Conduct a Freedom to Operate Analysis – PatentPC, accessed August 7, 2025, https://patentpc.com/blog/how-to-conduct-a-freedom-to-operate-analysis

- Patent landscape analysis—Contributing to the identification of …, accessed August 7, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10034625/

- Conducting a Patent Landscape Analysis for Drugs – ChemIntel360, accessed August 7, 2025, https://chemintel360.com/conducting-a-patent-landscape-analysis-for-drugs/

- Patent Landscape Analysis: A Vital Strategy for Innovative Companies – Dilworth IP, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.dilworthip.com/resources/news/patent-landscape-analysis/

- Pharmaceutical patent landscaping: A novel approach to understand patents from the drug discovery perspective | bioRxiv, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2023.02.10.527980v3.full-text

- Publications: Patent Landscape Reports – WIPO, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.wipo.int/publications/en/series/index.jsp?id=137

- Annual Pharmaceutical Sales Estimates Using Patents: A Comprehensive Analysis – DrugPatentWatch – Transform Data into Market Domination, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/annual-pharmaceutical-sales-estimates-using-patents-a-comprehensive-analysis/

- Patent research as a tool for competitive intelligence in brand protection – RWS, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.rws.com/blog/patent-research-as-a-tool/

- Strategic Imperatives: Leveraging Patent Pending Data for …, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/leveraging-patent-pending-data-for-pharmaceuticals/

- Patent Intelligence – IQVIA, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.iqvia.com/solutions/commercialization/commercial-analytics-and-consulting/brand-strategy-and-management/patent-intelligence

- DrugPatentWatch | Software Reviews & Alternatives – Crozdesk, accessed August 7, 2025, https://crozdesk.com/software/drugpatentwatch

- Drug Patent Watch – GreyB, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.greyb.com/services/patent-search/drug-patent-watch/

- Initiatives to Increase Communication Between the USPTO and the FDA Concerning Pharmaceutical Patent Applications – Dechert LLP, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.dechert.com/knowledge/onpoint/2023/2/left-hand–meet-right-hand—-should-there-be-more-communication.html

- Optimizing Your Drug Patent Strategy: A Comprehensive Guide for Pharmaceutical Companies – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/optimizing-your-drug-patent-strategy-a-comprehensive-guide-for-pharmaceutical-companies/

- The Global Patent Thicket: A Comparative Analysis of Pharmaceutical Monopoly Strategies in the U.S., Europe, and Emerging Markets – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/how-do-patent-thickets-vary-across-different-countries/

- Patent Litigation in the Pharmaceutical Industry: Key Considerations, accessed August 7, 2025, https://patentpc.com/blog/patent-litigation-in-the-pharmaceutical-industry-key-considerations

- Handling Drug Patent Invalidity Claims – DrugPatentWatch – Transform Data into Market Domination, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/handling-drug-patent-invalidity-claims/

- Orange Book Patent Listing and Patent Certifications: Key Provisions in FDA’s Proposed Regulations Implementing the Medicare Modernization Act of 2003 | Insights | Ropes & Gray LLP, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.ropesgray.com/en/insights/alerts/2015/02/orange-book-patent-listing-and-patent-certifications-key-provisions-in-fdas-proposed-regulations

- Our guide to understanding ANDA litigation. – IntrepidX, accessed August 7, 2025, https://intrepidx.com/our-guide-to-understanding-anda-litigation/

- How to Conduct a Successful Patent Litigation Discovery Process …, accessed August 7, 2025, https://patentpc.com/blog/how-to-conduct-a-successful-patent-litigation-discovery-process

- Patent Litigation Defense 101: What to Know When You’ve Been Sued for Infringement, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.venable.com/insights/publications/2025/05/patent-litigation-defense-101-what-to-know-when

- A practical guide to patent trial discovery, accessed August 7, 2025, http://euro.ecom.cmu.edu/program/law/08-732/Courts/DiscoveryGuide.pdf

- Patent litigation 101 | Legal Blog, accessed August 7, 2025, https://legal.thomsonreuters.com/blog/patent-litigation-101/

- What is E-Discovery? | TransPerfect Legal, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.transperfectlegal.com/blog/what-e-discovery-0

- Pharmaceutical & Life Sciences eDiscovery Solutions | Lighthouse, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.lighthouseglobal.com/ediscovery-for-pharma-biotech

- collection of twenty years of Markman Orders – IP Mall – University of New Hampshire, accessed August 7, 2025, https://ipmall.law.unh.edu/content/markman-orders-collection-collection-twenty-years-markman-orders

- Markman Hearing – Determining the Meaning of Patent Claims, accessed August 7, 2025, https://sierraiplaw.com/markman-hearing/

- Mastering Markman Hearings in Patent Infringement – Number Analytics, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.numberanalytics.com/blog/mastering-markman-hearings-patent-infringement

- The Impact of Teva Pharmaceuticals v. Sandoz on Patent Claim Construction in the District Courts | Federal Judicial Center, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.fjc.gov/publications/impact-teva-pharmaceuticals-v.-sandoz-patent-claim-construction-district-courts

- 11 Famous Supreme Court Patent Cases that Changed US Patent Law – GreyB, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.greyb.com/blog/famous-supreme-court-patent-cases/

- Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit | USAGov, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.usa.gov/agencies/court-of-appeals-for-the-federal-circuit

- What is the “Federal Circuit?” – MoloLamken LLP, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.mololamken.com/knowledge-what-is-the-federal-circuit

- Landmark Legislation: Federal Circuit | Federal Judicial Center, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.fjc.gov/history/legislation/landmark-legislation-federal-circuit

- About the Court – U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.cafc.uscourts.gov/home/the-court/about-the-court/

- US Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit – Latham & Watkins LLP, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.lw.com/en/weve-got-washington-covered/court-of-appeals-federal-circuit

- The Evolution of Patent Claims in Drug Lifecycle Management – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-evolution-of-patent-claims-in-drug-lifecycle-management/

- Mastering IP Litigation in Pharmaceuticals – Number Analytics, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.numberanalytics.com/blog/mastering-ip-litigation-pharmaceuticals

- Recent Pharmaceutical, Chemical, and Biotech Case Law on …, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.finnegan.com/en/insights/events/recent-pharmaceutical-chemical-and-biotech-case-law-on-infringement-under-the-doctrine-of-equivalents-02182025.html

- Doctrine of equivalents – Wikipedia, accessed August 7, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Doctrine_of_equivalents

- doctrine of equivalents | Wex | US Law | LII / Legal Information Institute, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/doctrine_of_equivalents

- 2186-Relationship to the Doctrine of Equivalents – USPTO, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.uspto.gov/web/offices/pac/mpep/s2186.html

- “OBVIOUS TO TRY”: A PROPER PATENTABILITY STANDARD IN THE PHARMACEUTICAL ARTS? – Jones Day, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.jonesday.com/-/media/files/publications/2008/04/obvious-to-try-a-proper-patentability-standard-in/files/obvious-to-try-andrew-trask/fileattachment/ssrnid1119686.pdf

- Formulation Patents and Dermatology and Obviousness – PMC, accessed August 7, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3857063/

- What Makes a Good Cell and Gene Therapy Application? | MoFo Life Sciences, accessed August 7, 2025, https://lifesciences.mofo.com/topics/what-makes-a-good-cell-and-gene-therapy-application-

- Hatch-Waxman Act/ANDA Litigation | Saul Ewing LLP, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.saul.com/capabilities/service/hatch-waxman-actanda-litigation

- Why Brand Pharmaceutical Companies Choose to Pay Generics in Settling Patent Disputes: A Systematic Evaluation of Asymmetric Risks – Scholarly Commons, accessed August 7, 2025, https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1156&context=njtip

- Paying for Delay: Pharmaceutical Patent Settlement as a Regulatory Design Problem – Scholarship Archive, accessed August 7, 2025, https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1010&context=contract_economic_organization

- Settled: Patent characteristics and litigation outcomes in the pharmaceutical industry, accessed August 7, 2025, https://pure.johnshopkins.edu/en/publications/settled-patent-characteristics-and-litigation-outcomes-in-the-pha

- Economic Analyses of Patent Settlement Agreements – USF Scholarship Repository, accessed August 7, 2025, https://repository.usfca.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1116&context=usflawreview

- Pay-For-Delay Settlements in the Wake of Actavis – University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository, accessed August 7, 2025, https://repository.law.umich.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1196&context=mttlr

- Pharmaceutical Patent Litigation Settlements: Implications for Competition and Innovation, accessed August 7, 2025, https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub/574/

- Drug Policy 101: Pay-for-Delay – Kaiser Permanente Institute for Health Policy, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.kpihp.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/pay_for_delay_drug_policy_101_paper_v6.pdf

- Pay for Delay | Federal Trade Commission, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/topics/competition-enforcement/pay-delay

- The Treatment of Pay-For-Delay Cases in the EU and the US – Stanford Law School, accessed August 7, 2025, https://law.stanford.edu/transatlantic-technology-law-forum/projects/the-treatment-of-pay-for-delay-cases-in-the-eu-and-the-us/

- An Investigation of when the Antitrust Agencies are likely to challenge a Pay-for-Delay Settlement under ACTAVIS – DigitalCommons@UM Carey Law, accessed August 7, 2025, https://digitalcommons.law.umaryland.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1341&context=jbtl

- Supreme Court Holds that “Pay-To-Delay” Deals Can Violate Antitrust Laws, accessed August 7, 2025, https://pomlaw.com/monitor-issues/supreme-court-holds-that-pay-to-delay-deals-can-violate-antitrust-laws

- Navigating Pharmaceutical Patent Settlements and Reverse Payments: Key Takeaways from the FTC’s Latest MMA Reports | Wilson Sonsini, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.wsgr.com/en/insights/navigating-pharmaceutical-patent-settlements-and-reverse-payments-key-takeaways-from-the-ftcs-latest-mma-reports.html

- A Decade of FTC v. Actavis: The Reverse Payment Framework Is Older, But Are Courts Wiser in Applying It? – American Bar Association, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.americanbar.org/groups/antitrust_law/resources/journal/86-2/decade-of-ftc-v-actavis/

- Reverse Payments After FTC v. Actavis: Supreme Court Unsettles Hatch-Waxman Patent Settlements – Wiley Rein LLP, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.wiley.law/media/publication/65_Reverse_Payments_After_FTC_v_Actavis_Supreme_Court_Unsettles_Hatch-Waxman_Patent_Settlements.pdf

- Reverse Payments: From Cash to Quantity Restrictions and Other …, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.ftc.gov/enforcement/competition-matters/2025/01/reverse-payments-cash-quantity-restrictions-other-possibilities

- FTC Staff Issues FY 2017 Report on Branded Drug Firms’ Patent Settlements with Generic Competitors, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/news/press-releases/2020/12/ftc-staff-issues-fy-2017-report-branded-drug-firms-patent-settlements-generic-competitors

- $52.6 Billion: Extra Cost to Consumers of Add-On Drug Patents – UCLA Anderson Review, accessed August 7, 2025, https://anderson-review.ucla.edu/52-6-billion-extra-cost-to-consumers-of-add-on-drug-patents/

- Patent cliff and strategic switch: exploring strategic design possibilities in the pharmaceutical industry – PMC, accessed August 7, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4899342/

- The impact of patent expiry on drug prices: insights from the Dutch market – PubMed Central, accessed August 7, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7717864/

- The Impact of Patent Expiry on Drug Prices: A Systematic Literature Review – PMC, accessed August 7, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6132437/

- Pharmaceutical patenting in the European Union: reform or riddance – PMC, accessed August 7, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8592279/

- UPC patent infringement: recent updates for the life sciences sector, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.taylorwessing.com/en/synapse/2025/two-years-of-upc-patent-litigation/upc-patent-infringement

- Unitary Patent & Unified Patent Court | epo.org, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.epo.org/en/applying/european/unitary

- The Unified Patent Court: assessing the impact on European life sciences patent litigation, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.europeanpharmaceuticalreview.com/article/188386/the-unified-patent-court-assessing-the-impact-on-european-life-sciences-patent-litigation/

- Two years of the UPC: why the patent court is growing in influence – Pinsent Masons, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.pinsentmasons.com/out-law/analysis/two-years-patent-court-growing-influence

- Key Takeaways from the UPC Litigation Forum and Pharma & Biotech Patent Litigation Europe Summit 2025 | Herbert Smith Freehills Kramer | Global law firm, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.hsfkramer.com/notes/ip/2025-02/key-takeaways-from-the-upc-litigation-forum-and-pharma-biotech-patent-litigation-europe-summit-2025

- Unified Patent Court Resource Center – McDermott Will & Emery, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.mwe.com/resource/unified-patent-court-resource-center/

- UPC litigation in life sciences: seven early takeaways for the pharma, biotech and medical devices sectors – Taylor Wessing, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.taylorwessing.com/en/synapse/2025/two-years-of-upc-patent-litigation/upc-litigation-in-life-sciences

- The Double-Edged Sword: Opportunities and Challenges in China’s …, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-double-edged-sword-opportunities-and-challenges-in-chinas-patent-litigation-system/

- Patent Linkage Litigation in China: A Two-Year Review | Global IP & Technology Law Blog, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.iptechblog.com/2023/08/patent-linkage-litigation-in-china-a-two-year-review/

- China’s Pharmaceutical Patent Linkage System – Mayer Brown, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.mayerbrown.com/-/media/files/perspectives-events/events/2022/05/chinas-pharmaceutical-patent-linkage-system.pdf%3Frev=e1dac49500454c12972137bf92fa1d1e

- China Launches Patent Linkage System to Resolve Drug Patent Disputes Before Market Entry – MedPath, accessed August 7, 2025, https://trial.medpath.com/news/3eeceac27c3831af/china-launches-patent-linkage-system-to-resolve-drug-patent-disputes-before-market-entry

- Patent linkage: Balancing patent protection and generic entry – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/patent-linkage-resolving-infringement/

- What China’s new patent linkage and patent term extension systems mean for foreign pharma – Hogan Lovells, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.hoganlovells.com/en/publications/what-chinas-new-patent-linkage-and-pte-systems-mean-for-foreign-pharma

- China’s New Patent Linkage System: A Guide for Foreign Chinese Patent Holders, accessed August 7, 2025, https://ipwatchdog.com/2021/07/22/chinas-new-patent-linkage-system-a-guide-for-foreign-chinese-patent-holders/id=135673/

- FAQs on China’s Patent Linkage System -LIU SHEN & ASSOCIATES, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.liu-shen.com/Content-3101.html

- Patent Litigation 2025 – China | Global Practice Guides – Chambers and Partners, accessed August 7, 2025, https://practiceguides.chambers.com/practice-guides/patent-litigation-2025/china/trends-and-developments

- Linking Patents to Pills: Unravelling the Patent Linkage Framework …, accessed August 7, 2025, https://corporate.cyrilamarchandblogs.com/2024/02/linking-patents-to-pills-unravelling-the-patent-linkage-framework-for-pharmaceutical-products-in-india/

- Pharmaceutical Patenting in India | candcip, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.candcip.com/pharmaceutical-patenting-in-india

- Indian Pharmaceutical Patent Law and the Effects of Novartis Ag v. Union of India – Washington University Open Scholarship, accessed August 7, 2025, https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1500&context=law_globalstudies

- The new patent regime: Implications for patients in India – PMC, accessed August 7, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2900001/

- Patent Litigation in India After the 2024 Amendments: A Step Towards Global IP Standards?, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.copperpodip.com/post/patent-litigation-in-india-after-the-2024-amendments-a-step-towards-global-ip-standards

- Process patent litigation in pharma sector – An overview – Lakshmikumaran & Sridharan, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.lakshmisri.com/insights/articles/process-patent-litigation-in-pharma-sector-an-overview/

- A “Calibrated Approach”: Pharmaceutical FDI and the Evolution of Indian Patent Law – USITC’s, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.usitc.gov/publications/332/journals/pharm_fdi_indian_patent_law.pdf

- PATENT LITIGATION AND PHARMACEUTICAL INDUSTRY: A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS BETWEEN EU AND US PRACTICES – Radhika Uppal – ijalr, accessed August 7, 2025, https://ijalr.in/volume-5-issue-4/patent-litigation-and-pharmaceutical-industry-a-comparative-analysis-between-eu-and-us-practices-radhika-uppal/

- Introducing biosimilar competition for cell and gene therapy products – PMC, accessed August 7, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11247524/

- Patent vs. Trade Secret Considerations for Cell and Gene Therapies …, accessed August 7, 2025, https://lifesciences.mofo.com/topics/patent-vs-trade-secret-considerations-for-cell-and-gene-therapies

- Biopharmaceuticals: Patenting Challenges in Cell Therapy – PatentPC, accessed August 7, 2025, https://patentpc.com/blog/patenting-challenges-in-cell-therapy

- CAR T Cells As A Patentable Therapeutic – Rollins Scholarship Onlin, accessed August 7, 2025, https://scholarship.rollins.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1097&context=honors

- Mini review: Advances and challenges in CAR-T cell therapy: from early chimeric antigen receptors to future frontiers in oncology, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/hematology/articles/10.3389/frhem.2023.1217775/full

- CRISPR, Patents, and the Public Health – PMC, accessed August 7, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5733839/

- Mitigating Patent Risk in Gene Therapy Development – MoFo Life Sciences, accessed August 7, 2025, https://lifesciences.mofo.com/topics/mitigating-patent-risk-in-gene-therapy-development

- Introducing biosimilar competition for cell and gene therapy products – Oxford Academic, accessed August 7, 2025, https://academic.oup.com/jlb/article/11/2/lsae015/7713607

- An AI Start Up That Revolutionizes Patent Litigation – Law, disrupted podcast, accessed August 7, 2025, https://law-disrupted.fm/ai-patent-litigation/

- Research – Center for AI and Patent Analysis – Carnegie Mellon University, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.cmu.edu/epp/patents/research/index.html

- Implications of AI in Patent Litigation – PatentPC, accessed August 7, 2025, https://patentpc.com/blog/implications-of-ai-in-patent-litigation

- Will AI take over? : r/patentlaw – Reddit, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.reddit.com/r/patentlaw/comments/1ah9jnl/will_ai_take_over/

- The Double-Edged Sword of AI in Patent Drafting and Prosecution – The National Law Review, accessed August 7, 2025, https://natlawreview.com/article/double-edged-sword-ai-patent-drafting-and-prosecution

- The Double-Edged Sword of AI in Patent Drafting and Prosecution | AI Law and Policy, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.ailawandpolicy.com/2024/10/the-double-edged-sword-of-ai-in-patent-drafting-and-prosecution/

- Clarivate Launches AI-Powered Tool to Simplify IP Budgets and Forecasts, accessed August 7, 2025, https://clarivate.com/news/clarivate-launches-ai-powered-tool-to-simplify-ip-budgets-and-forecasts/

- Strategic Competitive Insights from AI Patent Analytics – LexisNexis IP, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.lexisnexisip.com/ai-patent-analytics/

- The Future of AI in the Pharmaceutical Industry | Articles | Finnegan | Leading IP+ Law Firm, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.finnegan.com/en/insights/articles/the-future-of-ai-in-the-pharmaceutical-industry.html

- Challenges of the Intellectual Property System in Pharmaceutical Innovations Resulting from Artificial Intelligence – KnE Publishing, accessed August 7, 2025, https://publish.kne-publishing.com/index.php/JPC/article/download/16191/15122/

- Artificial Intelligence and Patent Law | Congress.gov, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/LSB11251

- Artificial Intelligence in Drug Development: Patent Considerations – IPWatchdog.com, accessed August 7, 2025, https://ipwatchdog.com/2023/09/25/artificial-intelligence-drug-development-patent-considerations/id=167125/

- Emerging Legal Terrain: IP Risks from AI’s Role in Drug Discovery – Fenwick, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.fenwick.com/insights/publications/emerging-legal-terrain-ip-risks-from-ais-role-in-drug-discovery

- USPTO – FDA Collaboration Initiatives, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.uspto.gov/initiatives/fda-collaboration

- USPTO and FDA Continue to Focus on Patent Quality in the Pharmaceutical Industry | Insights & Resources | Goodwin, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.goodwinlaw.com/en/insights/blogs/2022/11/uspto-and-fda-continue-to-focus-on-patent-quality-in-the-pharmaceutical-industry

- The Price of Drug Innovation: Middlemen, Global Free-Riding… – IPWatchdog.com, accessed August 7, 2025, https://ipwatchdog.com/2025/07/29/price-drug-innovation-middlemen-global-free-riding/id=190710/

- The Role of Patents and Regulatory Exclusivities in Drug Pricing | Congress.gov, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/R46679