1. Executive Strategic Overview: The Fallacy of the Patent Cliff

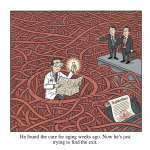

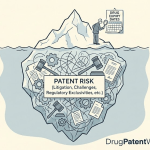

In the pharmaceutical industry, the “patent cliff” is often discussed with the hushed reverence usually reserved for natural disasters. It is viewed as a singularity event in the drug lifecycle: the moment a blockbuster product, potentially generating $10 million in revenue every single day, loses its protective shield and is devoured by a swarm of generic competitors.1 Analysts mark these dates in red on Gantt charts. Investment bankers build Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) models that flatline revenue the day after the expiry date passes. Multi-billion-dollar acquisition offers are predicated on the assumption that the date listed in a database is the date the monopoly ends.

This fixation is a dangerous, expensive hallucination.

In the modern biopharmaceutical landscape, relying on the printed expiry date of a primary patent to predict market entry is akin to navigating the North Atlantic by looking only at the tips of icebergs.1 It is a profound oversimplification of a system that has evolved into a labyrinth of legal, regulatory, and strategic mechanisms designed to render the calendar date irrelevant. The “expiry date” is merely the opening bid in a high-stakes negotiation between innovators, regulators, generic challengers, and the judiciary.

The numbers at stake are staggering. Between 2025 and 2030, the global pharmaceutical industry faces a wave of patent expirations that puts an estimated $200 billion to $400 billion in branded drug revenue at risk.1 Yet, the companies holding these assets are not passive victims of the calendar. They are active architects of “patent thickets,” creators of “regulatory fortresses,” and masters of “continuation practice”—strategies that can extend a franchise’s life by years. Conversely, the most successful generic launches—those that capture supranormal profits rather than commoditized scraps—are rarely the result of simply waiting for a patent to expire. They are the result of aggressive litigation strategies, precise regulatory maneuvering under the Hatch-Waxman Act, and the operational capacity to flood the market within hours of approval.

This report serves as a tactical manual for the generic strategist. It moves beyond the surface-level mechanics of Abbreviated New Drug Applications (ANDAs) to deconstruct the real-world operational realities of market entry. We analyze the anatomy of successful—and failed—generic launches, dissecting the precise legal arguments used to invalidate patents, the crushing economic impact of Authorized Generics (AGs), and the evolving battlefield of biosimilars where the “rebate wall” erected by Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs) has proven more formidable than the patent office itself.

We will examine the “at-risk” launch of Plavix, where a Canadian generic firm bet its entire existence on a patent challenge and lost hundreds of millions. We will scrutinize the “pay-for-delay” allegations surrounding Nexium, where settlements drew the ire of antitrust regulators. We will unpack the “skinny label” trap that cost Teva heavily in the Coreg litigation. And we will provide a blueprint for using intelligence tools like DrugPatentWatch to identify soft targets in the patent landscape, transforming raw litigation data into competitive alpha.

For the generic executive, the lesson is clear: The patent cliff is not a date. It is a campaign. And in this asymmetric war, the victor is not the firm with the lowest manufacturing cost, but the firm with the most sophisticated legal and commercial intelligence.

2. The Regulatory Engine: Maximizing Hatch-Waxman Incentives

The Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984, universally known as Hatch-Waxman, is the statutory bedrock of the modern generic industry. It was crafted to balance two competing public policy goals: providing meaningful market protection incentives to encourage the development of valuable new drugs, and ensuring the rapid availability of lower-priced generic versions once those protections expire.2 Understanding the nuance of this framework is the prerequisite for any market entry strategy.

2.1 The Paragraph IV Certification: The Declaration of War

To seek approval for a generic drug before the expiration of the brand’s patents, a generic applicant must file an ANDA containing a “Paragraph IV” certification. This is not a mere administrative checkbox; it is a legal declaration of war. A Paragraph IV certification asserts that a patent listed in the FDA’s “Orange Book” is, in the generic applicant’s opinion, invalid, unenforceable, or will not be infringed by the generic product.3

Filing this certification is defined by statute as an “artificial act of infringement.” It grants the brand company subject matter jurisdiction to sue the generic applicant in federal court before the generic has sold a single pill. If the brand sponsor files an infringement suit within 45 days of receiving notice of the certification, the FDA is automatically stayed from approving the generic ANDA for 30 months, or until the litigation is resolved.3

This 30-month stay is a critical strategic tool for the brand. It effectively buys two and a half years of guaranteed monopoly protection while the litigation plays out. For the generic challenger, it represents a period of intense cash burn—paying legal fees without any revenue to show for it.

2.2 The First-to-File (FTF) Grail: 180-Day Exclusivity

If the risks of Paragraph IV litigation are so high, why do generic firms undertake them? The answer lies in the 180-day exclusivity provision. The first applicant(s) to submit a substantially complete ANDA containing a Paragraph IV certification is eligible for a 180-day period during which no other generic applicant can obtain final approval.4

This six-month window is the economic engine of the generic industry. During this period, the market structure shifts from a monopoly (Brand only) to a duopoly (Brand + First Generic). This allows the first entrant to price their product significantly higher than they could in a fully competitive market.

Table 1: The Economics of Market Entry and Price Erosion

| Competitive Landscape | Number of Generic Entrants | Price Reduction (vs. Brand Price) | Market Dynamics |

| Exclusivity Phase | 1 (First-to-File) | 20% – 40% | The generic captures the majority of the market volume but maintains high margins. A period of “supranormal” profits. 5 |

| Early Competition | 2 Competitors | ~50% – 55% | Prices begin to crack. The duopoly breaks down. |

| Maturing Market | 3 – 5 Competitors | 60% – 70% | The “commoditization cliff” approaches. Margins compress rapidly. 6 |

| Hyper-Competition | 10+ Competitors | > 95% | The drug becomes a commodity. Profits depend entirely on manufacturing efficiency and volume. 5 |

The data is unequivocal: The value of being first is disproportionate. A study of generic sales indicates that extending the 180-day exclusivity period by even 30 days can result in a nearly 10% gain in sales for the first-to-file generic, translating to millions in additional revenue for blockbuster drugs.7

Consequently, the “race to the courthouse” defines the strategy. Because the first applicant is determined by the date of filing, multiple manufacturers often file on the very first possible day (the “NCE-1” date, which is four years after the brand’s approval for New Chemical Entities). If multiple firms file on this day, they share the exclusivity, diluting its value but still effectively locking out latecomers.8

2.3 Forfeiture: The Use-It-or-Lose-It Provisions

The exclusivity right is not absolute. To prevent generic firms from “parking” exclusivity—filing first and then cutting a deal with the brand to delay launch indefinitely—Congress introduced forfeiture provisions. A first applicant can forfeit their exclusivity if they fail to obtain tentative approval within 30 months, withdraw their application, or fail to market the drug within 75 days of final approval.9

This creates a high-pressure environment where the first filer must not only win the legal battle but also maintain impeccable regulatory standing. As we will see in the case of Ranbaxy and Lipitor, failure to maintain Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP) can jeopardize the most valuable asset a generic firm possesses.

3. Case Study: The Lipitor (Atorvastatin) Launch

The launch of generic Lipitor (atorvastatin) is the definitive case study for understanding the complex interplay between regulatory exclusivity, manufacturing compliance, and authorized generic defense strategies. At its peak, Lipitor was the best-selling drug in the world, generating nearly $8 billion annually in the U.S. alone.10 The generic launch was not just a product introduction; it was a macroeconomic event.

3.1 The Ranbaxy Bottleneck and the Application Integrity Policy

Ranbaxy Laboratories, an Indian generic manufacturer, secured the coveted first-to-file status for atorvastatin. This should have been a golden ticket, guaranteeing hundreds of millions in profit. However, Ranbaxy’s internal operations were in chaos.

The FDA uncovered systemic data integrity issues at Ranbaxy’s manufacturing facilities in Paonta Sahib and Dewas, India. The violations were egregious: falsified stability data, backdated test results, and non-sterile manufacturing conditions.11 In 2009, the FDA invoked its “Application Integrity Policy” (AIP) against Ranbaxy, effectively halting the review of any applications relying on data from these sites.12

This created a regulatory paradox. Under the Hatch-Waxman statute, the 180-day exclusivity belongs to the first filer. No other generic could launch until Ranbaxy’s 180-day clock had run. But Ranbaxy could not launch because its application was frozen by the FDA due to fraud. The entire generic market for the world’s biggest drug was paralyzed by one company’s compliance failures.

3.2 Teva’s Strategic Intervention

Recognizing the deadlock, Teva Pharmaceutical Industries—the world’s largest generic maker—executed a masterstroke of deal-making. Teva understood that while Ranbaxy could not manufacture the drug, it still held the rights to the exclusivity period.

Teva entered into a secret agreement with Ranbaxy. While the full financial terms were never disclosed, the arrangement effectively allowed Teva to launch a generic atorvastatin in November 2011. Teva likely manufactured the product or assisted Ranbaxy in securing a compliant supply chain, and in exchange, Teva paid Ranbaxy a portion of the profits during the exclusivity period.10

This case demonstrates a crucial insight for generic strategists: Regulatory assets (like exclusivity) are tradable commodities. Even a company with a crippled supply chain can monetize its first-to-file status if it can partner with a competent operator. Teva utilized its clean compliance record and market leverage to unlock the bottleneck, ensuring that the generic launch proceeded, albeit with a split profit pool.

3.3 The “Authorized Generic” Counter-Strike

Pfizer did not passively watch this maneuvering. It deployed an aggressive “Authorized Generic” (AG) strategy to defend its revenue. An AG is the brand company’s own drug, manufactured on the same lines as the brand, but packaged as a generic and sold at a lower price, often through a subsidiary or licensee.14

Pfizer licensed Watson Pharmaceuticals (now part of Teva) to launch an authorized generic of Lipitor simultaneously with the Ranbaxy/Teva launch.15 This move fundamentally altered the economics of the exclusivity period. Instead of a duopoly (Brand vs. First Generic), the market became a triopoly (Brand vs. First Generic vs. Brand’s Generic).

The impact of this strategy is quantifiable and devastating for the first filer. According to FTC data:

“The presence of an AG reduces the first-filer’s revenue by 40% to 52% during the 180-day period. Price Erosion: Wholesale prices drop by an additional 7% to 14% when an AG is present.”

By launching an AG, Pfizer retained approximately 70% of the profit from the AG sales.15 This effectively allowed Pfizer to compete with itself, capturing the price-sensitive customers who would otherwise have defected to the Teva/Ranbaxy product. For generic strategists, the lesson is clear: Exclusivity is not a monopoly. Revenue models must account for the high probability of an AG launch, which acts as a “tax” on the first filer’s returns.

3.4 The Marketing Blitz

Pfizer also defied convention by continuing to market branded Lipitor aggressively even after the generic launch. It negotiated contracts with PBMs and health plans to keep branded Lipitor on formulary at a subsidized copay, effectively neutralizing the price advantage of the generic for many insured patients.15 They spent $150 million on TV ads in 2011, a time when most companies would have cut marketing spend to zero.15 This “scorched earth” defense forced the generic competitors to fight for every prescription, further eroding the value of the exclusivity period.

4. Case Study: The “At-Risk” Launch of Plavix

If Lipitor represents a negotiated launch, the launch of generic Plavix (clopidogrel) by Apotex represents the high-stakes gamble of an “at-risk” launch. It serves as a cautionary tale of what happens when legal confidence outstrips legal reality.

4.1 The Calculation of Risk

Plavix, a blood thinner marketed by Sanofi and Bristol-Myers Squibb (BMS), was generating $3.3 billion annually.17 Apotex, a Canadian generic giant, challenged the validity of the key patent (the ‘265 patent), arguing that it was invalid because it was anticipated by a prior patent.

Litigation dragged on. A proposed settlement, which would have seen BMS pay Apotex $40 million to delay launch, was rejected by regulators.18 Frustrated and confident in their legal position, Apotex leadership made the decision to launch “at risk” in August 2006.

“At risk” means launching after the FDA’s 30-month stay has expired but before the district court has issued a final verdict on patent validity. If the generic company wins the suit later, they keep the profits. If they lose, they are liable for damages—typically the lost profits of the brand, which are far higher than the generic’s revenue.

4.2 The Flood and the Fall

Apotex moved with blinding speed. They flooded the distribution channel, selling $884 million worth of generic clopidogrel in just three weeks.17 They knew that once the product was in the pharmacies, it would be difficult to recall.

However, the gamble failed spectacularly. The U.S. District Court upheld the validity of Sanofi’s patent. Apotex was ordered to cease sales immediately. But the damage to the market price was done, and the legal reckoning was severe.

Sanofi and BMS sought damages not based on Apotex’s profits, but on their own lost sales and price erosion. The court awarded $442 million in damages to Sanofi and BMS.17

4.3 The Boardroom Implications

While Apotex CEO Barry Sherman framed the move as a crusade for affordable medicine—stating they launched because “Apotex always strives to make quality, affordable generic medicines accessible” 17—the financial reality was a disaster. The $442 million payment represented half of Apotex’s net sales during the period, wiping out the profit margin and then some.

This case serves as a stark warning to investors and boards. An at-risk launch can destroy a company’s balance sheet if the underlying patent analysis is flawed. It also highlights the “triple damages” risk in patent litigation, where willful infringement can lead to punitive financial penalties.

5. Authorized Generics: The Brand’s Defensive Moat

The use of Authorized Generics (AGs) has evolved from a tactical surprise to a standard operating procedure for lifecycle management. Data from the FTC indicates that AGs are frequently used as bargaining chips in patent settlements.20

5.1 The Strategic Rationale

Why would a brand company launch a generic version of its own drug? Superficially, it appears to cannibalize sales. However, the economic logic is sound:

- Market Segmentation: The brand can continue to sell the high-priced branded product to “loyalist” patients and doctors who refuse to switch, while simultaneously capturing the price-sensitive “generic” segment with the AG.21

- Deterrence: By committing to launch an AG, the brand signals to future generic challengers that the potential pot of gold at the end of the litigation rainbow is smaller. This lowers the expected value (EV) of a patent challenge, theoretically deterring future P-IV filings.22

- Revenue Retention: The brand typically retains 90-95% of the revenue from the AG if they sell it through a subsidiary (like Pfizer’s Greenstone) or 50-70% if they license it to a third party (like Watson).15 This is far better than the 0% revenue they would get from a competitor’s generic.

5.2 Viagra (Sildenafil) and the White Pill

When Pfizer faced the expiration of Viagra’s patents, it utilized a dual strategy of settlement and AG launch. Pfizer settled with Teva, allowing Teva to launch a generic in December 2017, years before the 2020 patent expiration.23

However, Pfizer simultaneously launched its own AG through its subsidiary Greenstone. This “white pill” was chemically identical to the famous “blue pill” but sold at a 50% discount.23 By doing so, Pfizer kept a foot in both markets. The AG diluted Teva’s exclusivity value, demonstrating how brands use AGs to maintain market control well past the optical “loss of exclusivity”.25

For the generic challenger, the AG is a “profit killer.” Generic firms must factor in a 40-52% revenue reduction during exclusivity if an AG is anticipated.16 This changes the calculus of litigation. If the cost of litigation is $5 million and the expected profit is halved by an AG, the ROI of the challenge may no longer meet the generic firm’s internal hurdle rate.

6. Complex Generics: The Barrier of Manufacturing

As the market for simple, small-molecule oral solids becomes commoditized and crowded, the “smart money” in generics has moved toward complex products—injectables, inhalers, and long-acting formulations. These products have higher barriers to entry, resulting in fewer competitors and slower price erosion.

6.1 Copaxone (Glatiramer Acetate): The Science of “Sameness”

Teva’s Copaxone, a treatment for Multiple Sclerosis, is a complex mixture of polypeptides. Unlike a simple molecule like atorvastatin, which has a distinct chemical structure, glatiramer acetate is a random polymer. Teva defended its franchise not just with patents, but by arguing that generics could not prove “sameness” to the brand due to the drug’s inherent complexity.26

This forced generic competitors like Sandoz (Novartis) and Momenta Pharmaceuticals to invest heavily in advanced analytical characterization. When they finally launched Glatopa, it was a significant technical achievement. However, the market dynamics were complicated by Teva’s “product hop.”

Teva successfully shifted a large portion of patients from the original 20mg daily injection to a new 40mg 3x/week injection before the generics could gain a foothold.27 By the time Mylan launched its generic version of the 40mg product, the market had fragmented. The Copaxone case illustrates that technical feasibility is only half the battle; commercial timing relative to the brand’s lifecycle management (product hopping) is critical.27

6.2 Advair (Wixela Inhub): The Device Challenge

Mylan’s launch of Wixela Inhub, a generic to GSK’s Advair, highlights the difficulty of device-drug combinations. For asthma inhalers, the FDA requires that the generic device be user-friendly and functionally equivalent to the brand device. Mylan invested $700 million over nearly a decade to bring Wixela to market.28

Upon launch, Mylan priced Wixela at a 70% discount to the brand and, crucially, 67% below GSK’s own authorized generic.29 This aggressive pricing allowed Wixela to capture 24% of the market within just three weeks.29

This success validates the ROI of high-barrier complex generics: while the development cost is high ($700M) and the timeline is long, the ability to undercut even the authorized generic can drive rapid volume adoption in a market with few competitors.

7. The Section viii Strategy: Skinny Labeling

When a brand drug has multiple indications protected by different patents, generic firms can use a “Section viii” statement to seek approval for only the unpatented indications. This is known as a “carve-out” or “skinny labeling”.30

7.1 The Coreg (Carvedilol) Trap

The case of GSK v. Teva regarding the heart drug Coreg is a critical precedent that has sent shockwaves through the industry. Coreg was approved for three indications: hypertension, left ventricular dysfunction (LVD), and congestive heart failure (CHF). The patent for CHF was still valid, while the others had expired.

Teva launched a generic carvedilol with a label that “carved out” the patented CHF indication, marketing it only for hypertension and LVD.30 This is a standard Section viii strategy.

However, GSK sued for “induced infringement.” They argued that Teva’s press releases—which described the drug as an “AB-rated equivalent” to Coreg—along with marketing materials, encouraged doctors to prescribe the generic for the patented CHF indication. GSK argued that Teva knew doctors would use it for CHF and encouraged it implicitly by claiming equivalence.

The court agreed with GSK, reinstating a $235 million verdict against Teva.30 The court effectively weaponized the industry-standard term “AB-rated,” ruling that claiming full equivalence when one indication is carved out can be evidence of inducement.

Strategic Implication: The “skinny label” is a fragile shield. Generic commercial teams must exercise extreme discipline. A single press release claiming “equivalence” without qualification can nullify the legal protection of the carve-out, turning a safe harbor into a multimillion-dollar liability.32 Marketing teams must be trained to specifically state which indications are approved, rather than relying on broad “equivalence” claims.

8. Biosimilars: The New Frontier and the PBM Wall

Biosimilars represent the next wave of loss-of-exclusivity opportunities, but they behave differently than small-molecule generics. The launch of biosimilars for Humira (adalimumab) in 2023 provides the most current data on this divergence.

8.1 The Humira 2023 Launch Wave

Humira, with over $200 billion in lifetime sales, faced competition from Amgen (Amjevita), Sandoz (Hyrimoz), and others in 2023.33 Unlike the rapid price collapse seen with Lipitor, Humira’s erosion was slow and controlled.

Why the difference?

- Interchangeability: Unlike generics, biosimilars are not automatically substituted at the pharmacy unless designated “interchangeable” by the FDA. Boehringer Ingelheim’s Cyltezo was the first to achieve this designation, but it didn’t guarantee market dominance.33 The lack of automatic substitution means sales reps must still call on doctors to drive switches, increasing the cost of sales.

- The Rebate Wall: Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs) often prefer the high-list-price / high-rebate brand drug over the low-cost biosimilar. PBMs negotiate rebates from the manufacturer (e.g., 50% off the list price) and often retain a portion of that rebate as profit. A cheaper biosimilar with no rebate generates less revenue for the PBM.34

8.2 The Dual-Pricing Strategy

To combat this perverse incentive structure, companies like Amgen and Sandoz launched two versions of their biosimilars:

- Branded/High-WAC Version: A product with a high Wholesale Acquisition Cost (e.g., 5% discount to Humira) designed to offer high rebates to PBMs, securing formulary access.

- Unbranded/Low-WAC Version: An identical product with a deep discount (e.g., 55% to 80% off) for cash payers, community health centers, and value-based plans.33

Sandoz reported that this strategy, combined with a partnership with CVS Health’s Cordavis private label, allowed Hyrimoz to capture 81% of the biosimilar market share.35 This confirms that biosimilar commercialization is a B2B contracting game with payers, not a B2C marketing game with physicians. The “customer” is the PBM, and the “product” is the rebate structure.

9. Supply Chain: The Silent Killer of Launch Success

A legal victory in the courtroom is useless if the product cannot be shipped. Supply chain resilience is the unglamorous backbone of launch readiness. The industry is littered with examples of firms that won the patent war but lost the logistics peace.

9.1 The Intas/Cisplatin Failure

In 2023, Intas Pharmaceuticals, a major supplier of the cancer drug cisplatin, was forced to shut down its Ahmedabad facility following an FDA inspection. The findings were straight out of a thriller: inspectors found plastic bags filled with torn and shredded documents, some doused in acid to destroy evidence of data manipulation.36

This single point of failure at one plant in India triggered a nationwide shortage of a critical chemotherapy drug in the United States. It highlights the extreme fragility of the generic supply chain, where razor-thin margins have led to massive consolidation and a lack of redundancy.36

9.2 Operational Readiness Checklist

Successful launches, like Teva’s generic Viagra, are supported by massive inventory builds and “wraparound services”.24 Best practices for “Day 1” readiness include:

- Inventory Depth: Building 3-6 months of stock prior to the anticipated launch date. This requires capital commitment “at risk” before approval is final.37

- Dual Sourcing: Avoiding reliance on a single API supplier. While dual qualification increases upfront regulatory costs, it is an insurance policy against the kind of catastrophic failure seen at Intas.38

- System Integration: Ensuring commercial inventory systems (ERP) are validated and ready to process thousands of orders the moment FDA approval drops. Logistics partners like UPS Healthcare often run “war room” simulations to prepare for the surge.39

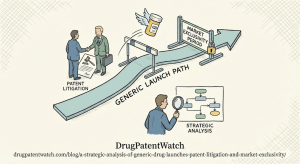

10. Strategic Intelligence: Utilizing Patent Data

In this high-velocity environment, static data is a liability. Platforms like DrugPatentWatch have become essential for competitive intelligence (CI). They allow firms to move beyond looking at patent expiration dates—which are often misleading due to Patent Term Extensions (PTE), Pediatric Exclusivity (PED), and other adjustments—and instead track the events that trigger market entry.1

10.1 The Intelligence Workflow

A robust CI strategy involves monitoring three distinct signal types:

- Paragraph IV Filings: Identifying when a competitor has fired the “starting gun” on litigation. This is often the first public signal that a drug is under attack.40

- Litigation Outcomes: Watching for settlements that might set a “date certain” for entry earlier than the patent expiry. Many settlements are confidential, but court dockets often reveal the dismissal of cases, signaling a deal has been reached.41

- Citizen Petitions: Monitoring brand attempts to delay generic approval through regulatory filings. Brands often file “sham” petitions raising safety concerns about generics just days before approval is expected. Tracking these can predict delays.26

By integrating this data, companies can build “early warning systems” to identify in-licensing opportunities (e.g., “This drug has 4 patent challenges, price erosion will be high”) or prepare defensive AG strategies.40

11. The Pay-for-Delay Controversy: Nexium

The settlement of patent litigation can sometimes cross the line into antitrust violations. The In re Nexium litigation explored whether AstraZeneca paid Ranbaxy and Teva to delay the launch of generic esomeprazole (Nexium), a “purple pill” for heartburn.42

These agreements, termed “reverse payments” or “pay-for-delay,” involve the brand company paying the generic company to not enter the market. The Supreme Court’s Actavis decision ruled that such payments can be anticompetitive.

In the Nexium case, the plaintiffs alleged that AstraZeneca paid Ranbaxy $1 billion to delay its launch. While the jury ultimately found for the manufacturers (deciding that while a “large and unjustified payment” existed, it wasn’t the sole cause of the delay due to Ranbaxy’s manufacturing issues), the case highlights the immense legal risk of settlements.43

The Strategic Lesson: Settlement is a valid exit ramp from litigation, but it must be structured carefully. Agreements that involve cash payments from brand to generic are radioactive to regulators. Modern settlements often involve “licensing dates” without cash transfers, or payments for “services” (like raw material supply) that must be rigorously benchmarked to fair market value to avoid looking like a bribe.41

12. Emerging Trends: 2025 and Beyond

12.1 The Rise of the “Complex Generic”

As the “patent cliff” for simple solids stabilizes, the market is shifting toward injectables and biologics. Sandoz’s success with Hyrimoz and Glatopa signals that the future belongs to firms that can master both the biology and the manufacturing.35 The era of the “virtual generic company” that outsources everything is fading; vertical integration is becoming a competitive advantage in quality control.

12.2 Policy Headwinds: The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA)

The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) introduces government price negotiations for top-spending drugs. This creates a new variable in the generic equation. If the government negotiates the brand price down significantly before a generic launches, the “spread” available for the generic challenger shrinks.

This could paradoxically reduce generic competition. If the potential margin is compressed by government price controls, fewer generic firms may be willing to fund the expensive Paragraph IV litigation required to break the patents.44 The ROI of a challenge drops if the prize at the end is a price-controlled market.

13. Conclusion

The landscape of generic drug launches is a testament to the complexity of modern healthcare economics. It is a sector where success requires the synthesis of high science, aggressive litigation, regulatory maneuvering, and supply chain precision.

The case studies of Lipitor, Plavix, and Humira demonstrate that there is no single template for success. Teva succeeded with Lipitor by being an opportunistic dealmaker. Apotex failed with Plavix by being reckless with risk. Sandoz succeeded with Humira by understanding the Byzantine incentives of PBMs.

For the strategist, the key takeaways are:

- Exclusivity is King, but Fragile: Protect it with compliance (Ranbaxy warning) and expect it to be diluted by Authorized Generics.

- Litigation is Revenue: View legal departments as profit centers. A successful P-IV challenge is worth more than most R&D projects.

- The Label is the Limit: “Skinny labeling” requires strict commercial discipline to avoid inducement liability.

- Supply Chain is Survival: Redundancy is not waste; it is insurance against market exit.

- Data is Power: Use tools like DrugPatentWatch to see the battlefield before the shooting starts.

14. Key Takeaways

- The 180-Day Multiplier: Securing 180-day exclusivity is the single most important value driver. Extending it by just one month can increase revenue by nearly 10%.7

- The AG Tax: Always model a 40-50% revenue reduction during exclusivity due to the likely launch of an Authorized Generic.16

- The Compliance Cliff: Manufacturing quality is a strategic asset. Ranbaxy’s failure proves that a dirty plant can cost billions in lost exclusivity rights.

- The PBM Gatekeepers: In biosimilars, clinical equivalence is irrelevant without a rebate strategy. Dual-pricing (High WAC/Low WAC) is the new standard for market access.

- The Skinny Label Trap: Marketing materials must be meticulously reviewed to ensure they do not imply efficacy for carved-out indications, or risk massive inducement damages.30

15. FAQ: Expert Insights on Generic Launches

Q1: How does the “Forfeiture” of 180-day exclusivity actually happen in practice?

A1: Forfeiture is a statutory mechanism to prevent “parking.” It occurs if the first-to-file applicant fails to obtain tentative approval within 30 months of filing, withdraws their application, or fails to market the drug within 75 days of final approval. It ensures that a generic firm cannot file a challenge and then sit on the rights to block other competitors.9

Q2: Why would a brand company launch an Authorized Generic if it cannibalizes their own sales?

A2: It is a defensive “scorched earth” strategy. While it cannibalizes brand sales, it allows the brand to capture the generic customer segment that would otherwise go entirely to the competitor. It also destroys the profit margins of the challenging generic, discouraging future patent challenges against the brand’s other portfolio products. It’s about retaining some revenue rather than none.21

Q3: Can a generic launch “at risk” even if the brand has a valid patent?

A3: Yes, technically. “At risk” means launching after the 30-month stay expires but before a district court has issued a final verdict on patent validity. If the generic eventually wins the case, they keep the profits. If they lose (like Apotex with Plavix), they owe massive damages, often calculated as the brand’s lost profits (which are much higher than generic revenue) or even triple damages for willful infringement.17

Q4: How do PBMs impact the uptake of new generics and biosimilars?

A4: PBMs act as gatekeepers. They often block cheaper generics/biosimilars in favor of expensive brands because PBMs are paid a percentage of the “rebate” from the brand manufacturer. A cheaper drug with no rebate generates less revenue for the PBM. This “rebate wall” forces generics to adopt complex pricing strategies, such as offering high-list-price versions to pay rebates to PBMs.34

Q5: What is the specific value of using a tool like DrugPatentWatch for generic strategy?

A5: DrugPatentWatch allows firms to identify “soft targets”—patents that have a history of successful challenges or weak claims. It also tracks the “NCE-1” date (the first date a generic can file), which is critical for joining the race for 180-day exclusivity. It transforms public data into a tactical timeline for litigation and R&D investment, acting as an early warning system for market opportunities.1

Works cited

- The Iceberg Illusion: Why Tracking Drug Expiry Dates Is the Least Important Part of Patent Risk – DrugPatentWatch, accessed December 29, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-iceberg-illusion-why-tracking-drug-expiry-dates-is-the-least-important-part-of-patent-risk/

- Small Business Assistance | 180-Day Generic Drug Exclusivity – FDA, accessed December 29, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/cder-small-business-industry-assistance-sbia/small-business-assistance-180-day-generic-drug-exclusivity

- Patent Certifications and Suitability Petitions – FDA, accessed December 29, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/abbreviated-new-drug-application-anda/patent-certifications-and-suitability-petitions

- The Hatch-Waxman 180-Day Exclusivity Incentive Accelerates Patient Access to First Generics, accessed December 29, 2025, https://accessiblemeds.org/resources/fact-sheets/the-hatch-waxman-180-day-exclusivity-incentive-accelerates-patient-access-to-first-generics/

- First Generic Launch has Significant First-Mover Advantage Over Later Generic Drug Entrants – DrugPatentWatch – Transform Data into Market Domination, accessed December 29, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/first-generic-launch-has-significant-first-mover-advantage-over-later-generic-drug-entrants/

- Drug Competition Series – Analysis of New Generic Markets Effect of Market Entry on Generic Drug Prices – https: // aspe . hhs . gov., accessed December 29, 2025, https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/510e964dc7b7f00763a7f8a1dbc5ae7b/aspe-ib-generic-drugs-competition.pdf

- Estimating the Value of Adding 30 Days to the 180-Day Market Exclusivity of the First-to-File Generic Drug Manufacturer – PubMed, accessed December 29, 2025, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/41004022/

- Guidance for Industry 180-Day Exclusivity When Multiple ANDAs Are Submitted on the Same Day – FDA, accessed December 29, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/files/drugs/published/180-Day-Exclusivity-When-Multiple-ANDAs-Are-Submitted-on-the-Same-Day.pdf

- 180-Day Generic Drug Exclusivity – Forfeiture – UC Berkeley Law, accessed December 29, 2025, https://www.law.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/180-Day-Generic-Drug-Exclusivity-%E2%80%93-Forfeiture.pdf

- RANBAXY ANNOUNCES LAUNCH OF ATORVASTATIN, GENERIC LIPITOR(R), IN THE U.S. – Press Releases – Media – Daiichi Sankyo, accessed December 29, 2025, https://www.daiichisankyo.com/media/press_release/detail/index_3727.html

- U.S. Files Consent Decree for Permanent Injunction Against Pharmaceutical Ranbaxy Laboratories | United States Department of Justice, accessed December 29, 2025, https://www.justice.gov/archives/opa/pr/us-files-consent-decree-permanent-injunction-against-pharmaceutical-ranbaxy-laboratories

- 1 August 1, 2014 Division of Dockets Management Food and Drug Administration Department of Health and Human Services 5630 Fisher – Consumer Federation of California, accessed December 29, 2025, https://consumercal.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/140801-CFC-response-to-Citizen-Petition-FDA-2014-P-0594.pdf

- Teva Announces Tentative Approval of Generic Lipitor, accessed December 29, 2025, https://ir.tevapharm.com/news-and-events/press-releases/press-release-details/2011/Teva-Announces-Tentative-Approval-of-Generic-Lipitor/default.aspx

- Authorized Generics In The US: Prevalence, Characteristics, And Timing, 2010–19, accessed December 29, 2025, https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/10.1377/hlthaff.2022.01677

- Pfizer’s 180-Day War for Lipitor – PM360, accessed December 29, 2025, https://pm360online.com/pfizers-180-day-war-for-lipitor/

- The First-Mover’s Gambit: A Strategic Guide to Maximizing the 180-Day Generic Exclusivity Advantage – DrugPatentWatch, accessed December 29, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-first-movers-gambit-a-strategic-guide-to-maximizing-the-180-day-generic-exclusivity-advantage/

- Apotex clopidogrel at-risk launch costs US$442 million – Generics and Biosimilars Initiative, accessed December 29, 2025, https://www.gabionline.net/generics/news/Apotex-clopidogrel-at-risk-launch-costs-US-442-million

- Plavix fzzranchise in jeopardy – PMC – NIH, accessed December 29, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7096798/

- Sanofi and Bristol-Myers Squibb Collect Damages in Plavix Patent Litigation with Apotex, accessed December 29, 2025, https://news.bms.com/news/details/2012/Sanofi-and-Bristol-Myers-Squibb-Collect-Damages-in-Plavix-Patent-Litigation-with-Apotex/default.aspx

- FTC Report Examines How Authorized Generics Affect the Pharmaceutical Market, accessed December 29, 2025, https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/news/press-releases/2011/08/ftc-report-examines-how-authorized-generics-affect-pharmaceutical-market

- Authorized Generics: Mastering a Controversial Strategy for Pharmaceutical Patent Lifecycle Management – DrugPatentWatch – Transform Data into Market Domination, accessed December 29, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/authorized-generics-mastering-a-controversial-strategy-for-pharmaceutical-patent-lifecycle-management/

- Strategic behavior and entry deterrence by branded drug firms: the case of authorized generic drugs – PubMed, accessed December 29, 2025, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39316276/

- Is generic Viagra available in the U.S.? – Drugs.com, accessed December 29, 2025, https://www.drugs.com/medical-answers/generic-viagra-available-2933640/

- Teva Announces Exclusive Launch of Generic Viagra® Tablets in the United States, accessed December 29, 2025, https://www.tevausa.com/news-and-media/press-releases/teva-announces-exclusive-launch-of-generic-viagra-tablets-in-the-united-states/

- Viagra’s Generic Cliff: Why It Wasn’t a Free-for-All – Drug Patent Watch, accessed December 29, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/viagra-a-complicated-case-study-of-generic-drug-market-entry-in-the-united-states/

- First Generic Version of MS Drug Copaxone Approved | AJMC, accessed December 29, 2025, https://www.ajmc.com/view/first-generic-version-of-ms-drug-copaxone-approved

- FDA has given Mylan’s Copaxone generic the green light – Pharmaceutical Technology, accessed December 29, 2025, https://www.pharmaceutical-technology.com/comment/commentfda-gave-mylans-copaxone-generic-the-green-light-5943165/

- Mylan Announces FDA Approval of Wixela™ Inhub™ (fluticasone propionate and salmeterol inhalation powder, USP), First Generic of ADVAIR DISKUS® (fluticasone propionate and salmeterol inhalation powder) | Mylan N.V. – Mylan Investor Relations, accessed December 29, 2025, https://investor.mylan.com/news-releases/news-release-details/mylan-announces-fda-approval-wixelatm-inhubtm-fluticasone

- Mylan’s Advair generic pressures GSK with strong launch – BioPharma Dive, accessed December 29, 2025, https://www.biopharmadive.com/news/mylan-advair-generic-gsk-strong-launch/550093/

- The Erosion of the Safe Harbor: How “Skinny Labels” Became a Multi-Billion Dollar Liability Minefield – DrugPatentWatch, accessed December 29, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-erosion-of-the-safe-harbor-how-skinny-labels-became-a-multi-billion-dollar-liability-minefield/

- Hatch-Waxman Overview | Axinn, Veltrop & Harkrider LLP, accessed December 29, 2025, https://www.axinn.com/en/insights/publications/hatch-waxman-overview

- SCOTUS won’t hear Teva v. GSK: Where does that leave us on FDA labeling carve-outs?, accessed December 29, 2025, https://www.hoganlovells.com/en/publications/scotus-wont-hear-teva-v-gsk-where-does-that-leave-us-on-fda-labeling-carve-outs

- Biosimilar Competition Erodes Humira’s Market Share; Amjevita Leads the Pack – AJMC, accessed December 29, 2025, https://www.ajmc.com/view/biosimilar-competition-erodes-humira-s-market-share-amjevita-leads-the-pack

- The Biosimilar Reimbursement Revolution: Navigating Disruption and Seizing Competitive Advantage – DrugPatentWatch – Transform Data into Market Domination, accessed December 29, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-impact-of-biosimilars-on-biologic-drug-reimbursement-models/

- Sandoz Raises Forecast After Humira Biosimilar Boosts Sales – Patsnap Synapse, accessed December 29, 2025, https://synapse.patsnap.com/article/sandoz-raises-forecast-after-humira-biosimilar-boosts-sales

- Not a One-Off: Real Stories Behind the World’s Most Damaging Healthcare Supply Chain Failures | THRIVE Project, accessed December 29, 2025, https://thrivabilitymatters.org/healthcare-supply-chain-failures-real-stories/

- Launching in 2025? 7 Key Considerations for Supply Chain Readiness – ABC PLAN, accessed December 29, 2025, https://abc-plan.com/2023/11/25/launching-in-2025-7-key-considerations-for-supply-chain-readiness/

- Policy Considerations to Prevent Drug Shortages and Mitigate Supply Chain Vulnerabilities in the United States, accessed December 29, 2025, https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/3a9df8acf50e7fda2e443f025d51d038/HHS-White-Paper-Preventing-Shortages-Supply-Chain-Vulnerabilities.pdf

- Lupin Pharmaceuticals Case Study – UPS Healthcare™ – Serbia, accessed December 29, 2025, https://www.ups.com/rs/en/healthcare/learning-center/case-studies/lupin-pharmaceuticals

- Using DrugPatentWatch to Support Out-Licensing and Partnering Decisions, accessed December 29, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/using-drugpatentwatch-to-support-out-licensing-and-partnering-decisions/

- What to Expect from Drug Patent Litigation – DrugPatentWatch, accessed December 29, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/what-to-expect-from-drug-patent-litigation/

- Jury Finds Nexium Pay-for-delay Agreement was Not Anticompetitive | Practical Law, accessed December 29, 2025, https://content.next.westlaw.com/practical-law/document/I231be8ce7f0611e498db8b09b4f043e0/Jury-Finds-Nexium-Pay-for-delay-Agreement-was-Not-Anticompetitive?viewType=FullText&transitionType=Default&contextData=(sc.Default)

- Antitrust Alert: Jury Finds for Drug Manufacturers in First Post-Actavis “Reverse Payment” Trial | Insights | Jones Day, accessed December 29, 2025, https://www.jonesday.com/en/insights/2014/12/antitrust-alert–jury-finds-for-drug-manufacturers-in-first-post-actavis-reverse-payment-trial

- How the IRA is impacting the generic drug market | PhRMA, accessed December 29, 2025, https://phrma.org/blog/how-the-ira-is-impacting-the-generic-drug-market

- Understanding the Impact of Authorized Generics on Drug Pricing: A Strategic Imperative for Market Domination – DrugPatentWatch, accessed December 29, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/understanding-the-impact-of-authorized-generics-on-drug-pricing-the-entacapone-case-study/

- Adalimumab Biosimilar Tracking, accessed December 29, 2025, https://biosimilarscouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/04022024_IQVIA-Humira-Tracking-Executive-Summary.pdf