Introduction: The High-Stakes Language of Pharmaceutical Patents

In the world of pharmaceuticals, language is power. But I’m not talking about marketing copy or clinical trial reports. I’m talking about the specialized vocabulary of intellectual property (IP)—a lexicon where terms like “exclusivity,” “Paragraph IV,” and “patent thicket” are not just legal jargon, but the very syntax of multi-billion-dollar business strategies. For any professional in this industry, fluency in this language is not an academic exercise; it is a fundamental prerequisite for competitive survival and market domination.

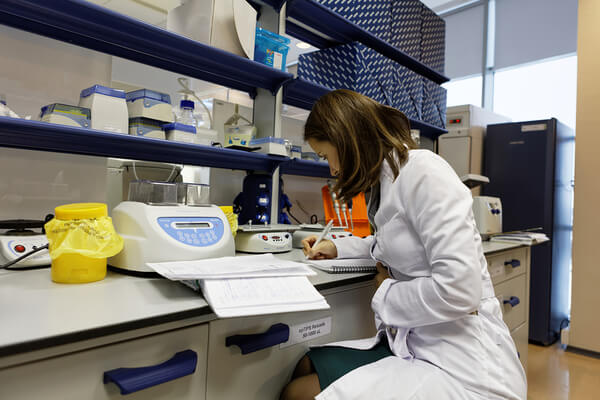

The pharmaceutical sector operates within a unique ecosystem, a delicate and often contentious balance of scientific innovation, stringent regulatory hurdles, and ironclad intellectual property law.1 At the heart of this ecosystem is the foundational “bargain” of the patent system: a government-granted, temporary monopoly is awarded to an inventor in exchange for the full public disclosure of their invention.3 This bargain is the engine that fuels the entire industry, providing the incentive to undertake the monumental task of drug development—a journey that frequently costs more than $2 billion and can span 10 to 15 years from discovery to market launch.4 Without the protection afforded by patents and their regulatory counterparts, the financial risks would be untenable, and the pipeline of new, life-saving medicines would slow to a trickle.3

However, navigating this landscape requires more than just a passing familiarity with the concepts. True strategic mastery demands a deep, nuanced understanding of two distinct but inextricably linked languages: the language of patent law, governed by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO), and the language of regulatory approval, administered by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). A brilliant patent on a groundbreaking molecule is commercially worthless without FDA approval to market it. Conversely, FDA approval without a robust IP shield is a fleeting victory, an open invitation for competitors to flood the market and erode profits overnight. The most successful companies are not just bilingual; they are masters of the intricate grammar that connects these two worlds, leveraging their interplay to build and defend commercial fortresses.

This guide is designed to provide that fluency. We will deconstruct 12 of the most essential terms in the pharmaceutical patent lexicon. But we will go beyond simple definitions. For each term, we will dissect its strategic implications, exploring how it is wielded as both a sword and a shield by innovator and generic companies alike. Our goal is to equip you, the business professional, with the sophisticated understanding needed to read the competitive battlefield, anticipate your rivals’ moves, and turn complex patent data into a decisive competitive advantage. Let’s begin.

Term 1: The Patent – More Than a Monopoly, It’s a Strategic Asset

Before we can delve into the intricate strategies of pharmaceutical warfare, we must first understand the primary weapon: the patent itself. It is the foundational legal instrument upon which the entire industry’s economic model is built. Yet, to view it merely as a 20-year monopoly is to miss the critical nuance that drives every strategic decision that follows. The true story of a pharmaceutical patent lies in the vast and often brutal disconnect between its theoretical lifespan and its actual commercial life.

What is a Pharmaceutical Patent?

At its most basic level, a patent is a form of intellectual property, a right granted by a government authority—in the United States, the USPTO—to an inventor.3 This right is not, as is commonly misunderstood, a right to

make or sell the invention. Rather, it is the right to exclude others from making, using, offering for sale, selling, or importing the patented invention for a limited period.3 This distinction is subtle but profound; a patent is fundamentally a defensive tool, a legal shield that creates a protected space in the market.

This protection is granted as part of a societal bargain. In exchange for this temporary period of market exclusivity, the inventor must provide a detailed and enabling public disclosure of the invention. This disclosure must be so complete that a person with ordinary skill in the relevant field could replicate the invention once the patent expires.3 This ensures that while the inventor profits for a time, society ultimately benefits from the addition of this new knowledge to the public domain, fostering follow-on innovation.

The 20-Year Term vs. Effective Patent Life: The Great Disconnect

The statutory term for a new U.S. patent is 20 years from the date on which the application was first filed.5 This 20-year standard is not arbitrary; it is a global mandate for all World Trade Organization (WTO) member nations under the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS). On paper, this seems like a generous period of protection. In the pharmaceutical reality, it is anything but.

The clock on that 20-year term starts ticking from the moment of filing, which typically occurs very early in the drug development process, often before a candidate has even entered human trials. What follows is a long and arduous journey through preclinical research, three phases of human clinical trials, and a rigorous regulatory review by the FDA. This entire process routinely consumes a massive portion of the patent term—often 10 to 15 years.5

The result is a stark and commercially critical disparity between the statutory patent term and the effective patent life. The effective patent life is the actual period during which a drug is on the market with patent protection, free from generic competition. Due to the “patent term erosion” caused by the lengthy R&D and approval timeline, this effective period is consistently and significantly shorter than the nominal 20 years, averaging only about 7 to 12 years.5

This fundamental economic pressure—the need to recoup a multi-billion-dollar investment in a compressed 7- to 12-year window—is the single most powerful force shaping the behavior of pharmaceutical companies. It is the primary driver behind the complex and often controversial lifecycle management strategies, such as evergreening and the creation of patent thickets, that we will explore later. These strategies are not conceived in a vacuum; they are a direct and rational business response to the immense financial pressure created by patent term erosion.

The Three Pillars of Patentability

To secure this valuable but time-limited asset, an invention must clear three fundamental hurdles set by patent law. These criteria ensure that patents are granted only for genuine advancements, not for trivial or already-known ideas.3

- Novelty: The invention must be new. This is an absolute requirement, meaning it cannot have been previously disclosed to the public in any form, anywhere in the world. This includes publications, presentations, public use, or even a sale.3

- Utility (Usefulness): The invention must have a specific, substantial, and credible utility. In the pharmaceutical context, this means it must have a practical purpose, such as treating a specific disease or condition.18

- Non-Obviousness: This is often the most difficult criterion to meet. The invention cannot be an obvious modification or combination of existing technologies (known as “prior art”) to a person having ordinary skill in the art (a “PHOSITA”). It must represent a genuine inventive leap.3

Mastering these three pillars is the first step in building a defensible patent portfolio. But as we’ve seen, securing the patent is only the beginning of the story. The real challenge lies in managing its limited lifespan in the face of immense economic pressures.

Term 2: Regulatory Exclusivity – The FDA’s Grant of Market Protection

While the patent provides one layer of protection, the pharmaceutical industry is unique in that it benefits from a second, entirely separate system of market protection: regulatory exclusivity. This is not a patent. It is not granted by the USPTO. It is a distinct grant of exclusive marketing rights awarded by the FDA itself, and it operates on a parallel track to the patent system. Understanding how to strategically layer these two forms of protection is a hallmark of sophisticated IP management.

Defining Exclusivity: The FDA’s Role

Regulatory exclusivity is a statutory provision that prevents the FDA from approving a competing generic drug application for a certain period of time following the approval of a new brand-name drug.11 Its purpose, much like the patent system, is to promote a balance between encouraging new drug innovation and facilitating generic drug competition.5

These exclusivity periods run concurrently with any existing patents but are independent of them. A crucial point for any strategist to remember is that exclusivity is not added to the patent life.11 A drug might have a patent that expires in 2035 and a five-year exclusivity that ends in 2030. In this case, the patent provides the longer period of protection. Conversely, a drug’s last patent might expire in 2028, but if it has an orphan drug exclusivity running until 2032, that exclusivity will block generics for an additional four years. A drug can have both forms of protection, only one, or neither.

Key Types of Regulatory Exclusivity

The duration and power of exclusivity vary depending on the type, each designed to incentivize a specific kind of innovation:

- New Chemical Entity (NCE) Exclusivity: This is one of the most significant forms of exclusivity. It provides 5 years of market protection for drugs that contain an active moiety (the core, biologically active part of a molecule) that has never before been approved by the FDA.5 During this period, the FDA cannot even accept an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) from a generic competitor for the first four years (this is shortened from five to four years if the generic files a Paragraph IV patent challenge, which we will discuss later). This is a powerful reward for developing truly novel medicines.

- Orphan Drug Exclusivity (ODE): To encourage the development of treatments for rare diseases, the Orphan Drug Act provides 7 years of exclusivity for drugs that are approved to treat a condition affecting fewer than 200,000 people in the United States.5 This longer period of protection helps companies justify investing in R&D for smaller patient populations that might otherwise be commercially unviable.

- New Clinical Investigation Exclusivity: Also known as “3-year exclusivity,” this is granted for drugs that required new clinical investigations (other than bioavailability studies) to get approved. This often applies to new indications for an already-approved drug, new dosage forms, or a switch from prescription to over-the-counter (OTC) status.11 It provides

3 years of protection against the approval of a generic that relies on the new data. - Pediatric Exclusivity (PED): This is perhaps the most unique and strategically potent form of exclusivity. It provides an additional 6 months of market protection as a reward for a company that conducts pediatric studies on its drug in response to a formal Written Request from the FDA.5 What makes PED so powerful is that it acts as a universal multiplier; this 6-month extension is tacked onto the end of

all other existing patents and exclusivities for that drug’s active moiety.11 If a blockbuster drug has five remaining patents and an NCE exclusivity period, a single pediatric study can extend all of them by six months. This can translate into billions of dollars in additional revenue, making the investment in pediatric research a remarkably high-return strategic decision, even if the pediatric market itself is small.

To crystallize the distinction between these two parallel systems of protection, the following table provides a direct comparison:

| Feature | Patent Protection (USPTO) | Regulatory Exclusivity (FDA) |

| Issuing Authority | U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) | U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) |

| Scope of Protection | Protects the invention itself (e.g., the molecule, a method of use, a formulation) | Protects the marketing rights for an approved product/indication, preventing FDA approval of competitors |

| Standard Duration | 20 years from the patent application filing date | Varies by type: 5 years (NCE), 7 years (ODE), 3 years (New Clinical Investigation), 6 months (Pediatric) |

| Triggering Event | Granted at any time upon meeting the legal criteria for patentability (novelty, utility, non-obviousness) | Granted only upon FDA approval of a drug product if statutory requirements are met |

| Primary Purpose | To incentivize R&D and public disclosure of inventions by granting a temporary monopoly | To promote a balance between new drug innovation and timely generic drug competition |

Understanding this dual-track system is essential. A comprehensive IP strategy doesn’t just focus on filing strong patents; it actively seeks to secure and layer these valuable, FDA-granted exclusivities to create a multi-faceted defense that maximizes the period of market protection.

Term 3: Composition of Matter Patent – The Crown Jewel of Pharma IP

Within the diverse world of patent types, one stands supreme in the pharmaceutical industry: the composition of matter patent. Often referred to as the “crown jewel” of a drug’s IP portfolio, this patent covers the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) itself. It is the most fundamental, powerful, and commercially valuable form of protection a pharmaceutical innovator can obtain, forming the bedrock upon which an entire drug franchise is built.

Defining the “Crown Jewel”

A composition of matter patent grants exclusionary rights over a novel chemical compound or molecule.3 In the context of pharmaceuticals, this is the patent on the actual drug substance—the molecule that exerts the therapeutic effect.

Its immense value stems from the breadth of its protection. A composition of matter patent prevents any competitor from making, using, or selling that specific molecule for any purpose during the patent’s term.3 It doesn’t matter if the competitor develops a new way to manufacture it, a different formulation to deliver it, or discovers a completely new disease it can treat. If they are using the patented molecule, they are infringing the patent. This provides a nearly impenetrable shield around the core innovation.

Strategic Importance

The strategic significance of the composition of matter patent cannot be overstated. It is the foundational layer of a drug’s “web of protection”.

- Primary Defense: It serves as the primary and most robust defense against generic competition during a drug’s peak revenue-generating years. The expiration date of this single patent is often the event that defines the “patent cliff”—the precipitous drop in sales that occurs when the first generics enter the market.

- Enabler of Lifecycle Management: The security provided by the composition of matter patent is what makes the entire strategy of lifecycle management possible. The period of market monopoly it grants generates the revenue and provides the time necessary for companies to conduct further research and development.7 This follow-on R&D is specifically aimed at creating incremental improvements—such as a new extended-release formulation or the discovery of a new therapeutic indication—that can themselves be patented.3 These subsequent patents, which we will discuss later, are the building blocks of an “evergreening” strategy. Without the initial, broad protection of the composition of matter patent, the investment required for this incremental innovation would be far too risky, as competitors could simply launch a generic version of the original API, rendering any improvements moot.

In essence, all other types of pharmaceutical patents—formulation patents, method-of-use patents, polymorph patents—are secondary layers of defense, strategically constructed around the central fortress of the composition of matter patent. Their purpose is to extend the franchise’s life and defend its market share long after this crown jewel has expired.

Term 4: The Orange Book – The Official Map of the Patent Battlefield

If the Hatch-Waxman Act is the rulebook for pharmaceutical patent warfare, then the FDA’s Orange Book is the official map of the battlefield. It is not merely a passive list of approved drugs; it is a dynamic and indispensable strategic document that dictates the terms of engagement for every patent dispute between brand and generic companies. For any strategist, reading and interpreting this document is a critical skill.

What is the Orange Book?

The formal title is Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations, but it is universally known as the Orange Book.11 It is a public database, updated daily and published annually by the FDA, that serves as the central repository for information on approved drugs, their associated patents, and any regulatory exclusivities they hold.11

Its creation under the Hatch-Waxman Act was a pivotal moment, as it established the formal “patent linkage” system—the mechanism that inextricably connects the FDA’s drug approval process with the USPTO’s patent system.1 The Orange Book is the physical manifestation of that link. It provides a transparent registry that allows generic companies to see exactly which patents they must confront to bring a competing product to market.

The Strategic Role of Patent Listing

The power of the Orange Book lies in the act of patent listing. When a brand-name company receives approval for a New Drug Application (NDA), it is required by law to submit information to the FDA on any patent that “claims the drug (drug substance or drug product) or a method of using the drug” for which a claim of patent infringement could reasonably be asserted.20

Listing a patent is not a mere administrative formality; it is a profoundly strategic act. Once a patent is listed in the Orange Book, any generic company wishing to file an ANDA for that drug is legally obligated to address that specific patent in its application.13 This is the tripwire that initiates the entire patent challenge process. By listing a patent, a brand company forces the hand of its potential competitors, ensuring that any attempt at generic entry will first have to pass through the gauntlet of patent litigation.

The “Ministerial” Role of the FDA and the Rise of “Improper Listing” Disputes

A critical feature—and a structural vulnerability—of the Orange Book system is that the FDA’s role in this process is purely “ministerial”.24 The agency does not substantively review the patents submitted by brand companies to verify their accuracy or relevance. It essentially takes the company at its word and lists the patent information provided. This has created a powerful incentive for brand companies to list as many patents as possible, sometimes leading to the controversial practice of “improper listing.”

This strategy involves listing patents that may not strictly meet the statutory requirements, such as patents that cover only a drug delivery device (like an inhaler) rather than the drug substance or product itself. The goal is to create additional legal hurdles to delay generic competition.

Industry Insight:

This issue came to a head in the landmark case of Teva v. Amneal. Teva had listed patents in the Orange Book for its ProAir HFA inhaler that claimed only the device components (e.g., a dose counter) and did not claim the active ingredient, albuterol sulfate. Amneal, a generic challenger, filed a counterclaim demanding that these patents be “delisted” from the Orange Book. In a pivotal 2024 decision, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit sided with Amneal, establishing a new, stricter standard: to be properly listed in the Orange Book, a patent must claim at least the active ingredient of the approved drug.28

This ruling represents a significant shift in the information warfare surrounding the Orange Book. It has transformed the act of “delisting” into a powerful offensive weapon for generic companies. Instead of merely trying to navigate the minefield of listed patents (by arguing non-infringement or invalidity), generics can now seek to dismantle the minefield itself by arguing that certain patents should never have been listed in the first place. This has opened a new front in Hatch-Waxman litigation, with significant antitrust implications for brand companies that are seen to be abusing the listing process to stifle competition.32 The Orange Book is no longer a static map; it is a dynamic battlefield where the very legitimacy of its features is now a point of active and high-stakes contention.

Term 5: The Hatch-Waxman Act – The Rulebook for Small-Molecule Warfare

To truly grasp the dynamics of pharmaceutical competition in the United States, one must understand the Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984, universally known as the Hatch-Waxman Act. This piece of legislation is more than just a law; it is the foundational “grand bargain” that architected the modern generic drug industry and established the intricate rules of engagement for the high-stakes conflict between innovator and generic companies over small-molecule drugs.

The “Grand Bargain” of 1984

Prior to 1984, the system was broken. Generic drugs faced an insurmountable barrier to entry, as they were required to conduct their own expensive and time-consuming clinical trials to prove safety and efficacy, even for drugs that had been on the market for years.2 At the same time, innovator companies were losing significant portions of their patent life to the lengthy FDA approval process, diminishing their incentive to invest in risky R&D.

The Hatch-Waxman Act was a masterful legislative compromise designed to solve both problems simultaneously.13 It created a symbiotic system that provided significant benefits to both sides, fundamentally reshaping the industry.

Key Provisions for Generic Companies

The Act handed the nascent generic industry two revolutionary tools that paved the way for its explosive growth:

- Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA): This was the game-changer. The Act created a streamlined approval pathway that allowed generic manufacturers to bypass the need for their own full-scale clinical trials. Instead, they only had to demonstrate that their product was “bioequivalent” to the innovator’s drug—meaning it is absorbed into the body at a similar rate and extent.13 By allowing generics to rely on the brand’s original safety and efficacy data, the ANDA process dramatically reduced the time and cost of bringing a generic to market.

- “Bolar” Provision / Safe Harbor: The Act codified a critical “safe harbor” (35 U.S.C. § 271(e)(1)) that explicitly permits generic companies to use a patented drug for activities “reasonably related to the development and submission of information” to the FDA before the patent expires.13 This provision, which overturned a court decision in

Roche Products, Inc. v. Bolar Pharmaceutical Co., is essential. It allows generics to conduct their bioequivalence studies and prepare their ANDA filings while the brand’s patent is still in force, ensuring they are ready to launch on day one of patent expiry.

Key Provisions for Brand-Name Companies

To balance the new advantages given to generics, the Act provided two crucial incentives for innovator companies:

- Patent Term Extension (PTE): This provision allows brand companies to apply to have the term of one patent on their drug extended to compensate for a portion of the time lost during the FDA’s regulatory review process. The extension can be for up to five years, though the total remaining patent life post-approval cannot exceed 14 years.13 This helps ensure innovators have a commercially viable period of market exclusivity to recoup their R&D investments.

- Regulatory Exclusivities: The Act also formalized the system of FDA-granted market exclusivities, such as the five-year NCE exclusivity and the three-year new clinical investigation exclusivity, which we discussed in Term 2.13

What makes the Hatch-Waxman Act so brilliant—and so complex—is that it is not just a set of parallel benefits. It is a deliberately designed system for instigating and managing conflict. By creating the ANDA pathway and forcing generic applicants to make a certification against every patent listed in the Orange Book, the Act ensures that a confrontation between the brand and generic will occur before the generic product ever reaches the market. The “artificial act of infringement” and the subsequent 30-month stay are not bugs in the system; they are the system—a carefully constructed legal arena for resolving patent disputes in a controlled, pre-commercialization environment. Understanding this intentional design is the key to grasping the strategic mindset required to win in the world of small-molecule pharmaceuticals.

Term 6: Paragraph IV Certification – The Formal Challenge to Patent Dominance

Within the intricate machinery of the Hatch-Waxman Act, the Paragraph IV certification is the ignition switch. It is the formal legal declaration by which a generic company throws down the gauntlet, challenging the validity or applicability of a brand-name drug’s patents. This single filing sets in motion the entire high-stakes litigation process, making it one of the most critical and consequential terms in the pharmaceutical IP lexicon.

The Four Certifications: A Declaration of Intent

When a generic company files an ANDA, it must address every patent listed in the Orange Book for the reference brand-name drug. It does this by making one of four possible certifications for each patent 13:

- Paragraph I Certification: A statement that no patent information for the reference drug has been filed in the Orange Book.

- Paragraph II Certification: A statement that the patent has already expired.

- Paragraph III Certification: A statement that the generic company will wait to launch its product until the date the patent expires.

- Paragraph IV (PIV) Certification: A bold declaration that the listed patent is invalid, unenforceable, or will not be infringed by the manufacture, use, or sale of the proposed generic drug.20

While the first three certifications are relatively straightforward and non-confrontational, the Paragraph IV certification is an explicitly aggressive move. It is a direct challenge to the innovator’s intellectual property rights.

The Paragraph IV Gamble: High Risk, High Reward

Filing a PIV certification is a calculated gamble with enormous potential upside and significant risk.36 As we’ve established, the Hatch-Waxman Act defines the submission of an ANDA containing a PIV certification as a technical, “artificial act of patent infringement”.13 This clever legal construction gives the brand-name patent holder an immediate right to sue the generic applicant for patent infringement, even though the generic product is not yet on the market.

The risk for the generic company is a costly and lengthy legal battle. Litigation costs for these cases can easily run into the millions of dollars per patent.38 If the generic company loses, its ANDA cannot be approved until the patent expires.

The reward, however, is immense. If the generic company is the first to file a PIV certification and ultimately prevails in the ensuing litigation (or secures a favorable settlement), it is granted a highly lucrative 180-day period of market exclusivity, which we will explore in detail as our next term.11

The 30-Month Stay: A Powerful Defensive Tool

The PIV certification process is structured to give the brand company a powerful defensive advantage right at the outset. After the generic company files its ANDA, it must send a “notice letter” to the brand company and patent holder, detailing the basis for its PIV certification. From the moment they receive this notice, the brand has a 45-day window to file a patent infringement lawsuit.25

If a suit is filed within this 45-day period, it automatically triggers a 30-month stay on the FDA’s ability to grant final approval to the generic’s ANDA.1 This stay provides the brand company with a guaranteed two-and-a-half-year period to litigate the patent dispute in court, all while its product remains free from generic competition.25

This automatic stay is one of the most powerful pro-innovator provisions in the entire Act. In standard patent litigation, a plaintiff seeking to block a competitor’s launch must petition the court for a preliminary injunction, a difficult legal hurdle that requires proving, among other things, a likelihood of success on the merits and the prospect of irreparable harm. Under Hatch-Waxman, the brand company gets the same market-blocking effect automatically, without having to meet any of these burdensome legal standards. The 30-month stay functions as a de facto preliminary injunction, granted by statute. This procedural advantage shifts the initial leverage in any dispute heavily in favor of the brand company and is a critical factor influencing the dynamics of settlement negotiations. Even a weak patent, if listed in the Orange Book and asserted in a timely lawsuit, can guarantee an additional 30 months of monopoly profits.

Term 7: 180-Day Exclusivity – The Lucrative Prize for the First Generic Challenger

If the Paragraph IV certification is the gamble, the 180-day exclusivity is the jackpot. This powerful incentive, granted to the first generic company to successfully challenge a brand’s patents, is the primary economic engine driving the entire Hatch-Waxman litigation system. It is the prize that makes the high cost and risk of a PIV challenge a worthwhile business proposition, shaping the competitive dynamics of nearly every major generic drug launch.

The Ultimate Incentive

The Hatch-Waxman Act rewards the “first applicant”—the first company to submit a substantially complete ANDA containing a Paragraph IV certification—with a 180-day period of marketing exclusivity.11

During this six-month period, the FDA is prohibited from approving any subsequent ANDAs for the same drug from other generic competitors. This creates a unique and highly profitable market structure. For 180 days, the market consists only of the high-priced brand-name drug and the single, first-to-file generic. This effective duopoly allows the first generic to capture a massive portion of the market share without facing the immediate, severe price erosion that occurs when multiple generics enter simultaneously.

The Financial Windfall

The 180-day exclusivity period represents the golden age of a generic drug’s lifecycle. With only the brand as a competitor, the first generic can price its product at a modest discount—often only 15% to 25% below the brand price—and still rapidly gain market share due to automatic substitution laws and payer formularies.36 The financial returns can be staggering. For a blockbuster drug with billions in annual sales, this six-month window can generate hundreds of millions of dollars in revenue for the generic challenger. One study estimated the average value of a 180-day exclusivity period at $60 million , while another analysis showed a potential return on investment exceeding 1,000% for a successful challenge against a major brand.

This profitability is fleeting. As soon as the 180-day period ends, the floodgates open. The FDA can then approve all other pending ANDAs, and the entry of multiple generic competitors leads to intense price competition, often driving the price down by 80% to 90% or more from the original brand price.6 This dynamic makes securing that first-filer status a paramount strategic objective.

The Race to Be First

The immense value of the 180-day exclusivity creates a fierce “race to file” among generic manufacturers. Companies invest heavily in competitive intelligence, using sophisticated data platforms like DrugPatentWatch to meticulously track Orange Book patent listings, monitor patent litigation, and forecast expiration dates.47 The goal is to identify the ideal drug candidates and time their ANDA submission perfectly to be the first to file a Paragraph IV challenge, thereby securing their claim to this lucrative prize.

However, brand companies have developed a powerful counter-strategy to dilute the value of this prize: the “authorized generic.” An authorized generic is the brand’s own drug, marketed under a generic label. Because it is covered by the original NDA, it does not require a separate ANDA approval from the FDA. This means the brand company can legally launch its own authorized generic at any time, including during the first-filer’s 180-day exclusivity period. This move shatters the duopoly, introducing a third competitor and forcing the first-filer to share the market. The presence of an authorized generic can slash the first-filer’s exclusivity revenues by 50% or more.44 The mere

threat of launching an authorized generic serves as a powerful bargaining chip for brand companies in settlement negotiations, fundamentally altering the risk-reward calculation for any generic company contemplating a Paragraph IV challenge.

Term 8: The BPCIA – The Distinct Legal Universe for Biologics

For decades, the Hatch-Waxman Act was the undisputed law of the land for pharmaceutical patent disputes. However, as medical science evolved, a new class of drugs emerged that simply did not fit into the Hatch-Waxman framework: biologics. These large, complex molecules, derived from living organisms, required a completely new and distinct legal universe to govern their competition. That universe is defined by the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA).

Why Biologics Needed Their Own Law

The fundamental difference between small-molecule drugs and biologics lies in their size and complexity.

- Small-Molecule Drugs: These are relatively simple chemical compounds, typically synthesized in a lab. Their structures are well-defined and can be replicated with perfect fidelity. The concept of “bioequivalence” under Hatch-Waxman works because a generic company can prove its chemically identical copy behaves the same way in the body.50

- Biologics: These are vast, intricate molecules—such as monoclonal antibodies or therapeutic proteins—produced by living cell cultures. They can be thousands of times larger than small molecules, with complex three-dimensional structures. Because they are made in living systems, there is inherent variability from batch to batch. It is scientifically impossible to create an exact, identical copy of a biologic.50

This scientific reality made the Hatch-Waxman model obsolete for this new class of drugs. A new law was needed to create a pathway for follow-on versions of biologics, which came to be known as “biosimilars.”

The Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA) of 2010

Passed as part of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, the BPCIA created the first-ever abbreviated licensure pathway for biosimilars in the United States.2 Like its predecessor, the BPCIA is a carefully constructed balance of competing interests. It provides a route for biosimilar competition, but in exchange, it grants innovator biologics a very generous

12-year period of regulatory data exclusivity from the date of their first FDA licensure.5 This is significantly longer than the five years of NCE exclusivity granted to small-molecule drugs, a reflection of the higher cost and complexity of biologic development.

Key Differences from Hatch-Waxman

The BPCIA established a legal and regulatory world with its own unique rules that are starkly different from the Hatch-Waxman system:

- Higher Bar for Approval: A biosimilar applicant cannot simply prove bioequivalence. They must demonstrate through a comprehensive “totality of the evidence” approach that their product is “highly similar” to the reference biologic and has “no clinically meaningful differences” in terms of safety, purity, and potency.50 This is a much more rigorous, time-consuming, and expensive standard, often requiring some level of clinical testing.

- No “Orange Book”: The BPCIA did not create a centralized public listing of patents for biologics. There is no “Purple Book” equivalent of the Orange Book for patent information. Instead, the BPCIA established a complex, private process for exchanging patent information directly between the biosimilar applicant and the reference product sponsor, a highly choreographed series of steps known as the “patent dance”.2

For business professionals, it is critical to recognize that these are two separate playbooks. The strategies, timelines, and legal mechanisms that govern small-molecule generic competition have little bearing on the world of biologics and biosimilars. The following table highlights the core strategic differences between these two foundational legal frameworks.

| Feature | Hatch-Waxman Act (Small Molecules) | BPCIA (Biologics) |

| Drug Type | Small-molecule chemical drugs | Large-molecule biologics |

| Follow-On Product | Generic Drug | Biosimilar / Interchangeable Biosimilar |

| Approval Standard | Bioequivalent | “Highly Similar” with “No Clinically Meaningful Differences” |

| Patent Listing | Publicly listed in the FDA’s Orange Book | No central patent list; private exchange between parties |

| Dispute Resolution | Paragraph IV Litigation (triggers 30-month stay) | “Patent Dance” (structured information exchange and litigation waves) |

| Innovator Exclusivity | 5 years for New Chemical Entities (NCE) | 12 years from first licensure |

Term 9: Biosimilar & Interchangeable – Navigating the Nuances of Biologic Competition

Under the BPCIA, not all follow-on biologics are created equal. The Act established a unique, two-tiered system that distinguishes between a “biosimilar” and a more stringently regulated “interchangeable biosimilar.” This distinction has had profound commercial and strategic implications for the biosimilar market, creating a complex landscape for manufacturers, payers, and providers. However, a recent and dramatic shift in FDA policy is poised to dismantle this two-tiered structure and fundamentally reshape the future of biologic competition.

Defining “Biosimilar”

As established, a biosimilar is a biological product that has been shown to be “highly similar” to an existing, FDA-approved innovator biologic (the “reference product”).50 The approval process requires extensive analytical, animal, and often clinical data to demonstrate that there are “no clinically meaningful differences” between the biosimilar and the reference product in terms of safety, purity, and potency.50

While a physician can prescribe an approved biosimilar with the same confidence as the reference product, it has a key commercial limitation: a biosimilar cannot be automatically substituted at the pharmacy counter. If a doctor writes a prescription for the reference biologic, the pharmacist cannot dispense the biosimilar without first getting explicit permission from the prescriber.60

The Higher Bar: “Interchangeable”

An “interchangeable” product is a biosimilar that has met an even higher statutory standard. To earn this designation, the manufacturer must provide additional data demonstrating that the product can be expected to produce the same clinical result as the reference product in any given patient.50 Furthermore, for products administered more than once, the manufacturer must show that the risk of alternating or switching between the reference product and the interchangeable biosimilar is no greater than the risk of staying on the reference product alone.

The commercial significance of the interchangeable designation is enormous. Subject to state pharmacy laws, an interchangeable biosimilar can be automatically substituted for the reference product by a pharmacist without the intervention of the prescribing physician—just like a generic small-molecule drug.60 This removes a major friction point in market adoption and provides a significant competitive advantage.

The Strategic Chasm and The 2024 FDA Guidance Shift

Historically, the primary hurdle to achieving interchangeability was the FDA’s expectation that manufacturers conduct dedicated and expensive “switching studies,” where patients are deliberately alternated between the reference product and the biosimilar to generate the necessary data.59 This requirement created a significant cost and time barrier, resulting in a two-tiered market where only a handful of biosimilars achieved the coveted interchangeable status.

This entire paradigm is now being upended. In a landmark move in June 2024, the FDA issued new draft guidance that signals a fundamental reversal of its policy. Citing a decade of accumulated scientific evidence and real-world experience showing that the risk of switching is insignificant, the agency announced that dedicated switching studies will generally no longer be necessary to demonstrate interchangeability.62

This policy shift is a tectonic event for the biologics industry. By removing the primary barrier to achieving interchangeability, the FDA is effectively collapsing the two-tiered system. The logical outcome is a future of “biosimilar parity,” where seeking and obtaining an interchangeable designation becomes the standard, not the exception. As the designation becomes ubiquitous, it will cease to be a competitive differentiator. The basis of competition in the biosimilar market will then shift almost entirely to price, payer access, and supply chain reliability—mirroring the dynamics of the mature small-molecule generic market. This change will dramatically accelerate price erosion for innovator biologics and intensify competition among biosimilar manufacturers, ultimately benefiting patients and the healthcare system through lower costs and increased access.

Term 10: The “Patent Dance” – The Choreographed Dispute for Biologics

Because the BPCIA did not create a public repository of patents like the Orange Book, it had to invent a new mechanism for resolving patent disputes before a biosimilar could launch. The result is one of the most complex and uniquely named processes in all of intellectual property law: the “patent dance.” This highly structured, multi-step exchange of information is the formal procedure through which a biosimilar applicant and a reference product sponsor identify and tee up patents for litigation.

The Steps of the Dance

The patent dance is a carefully choreographed sequence of disclosures and responses, each with a specific deadline, designed to narrow the scope of potential patent disputes.58 While the full process is intricate, the key steps are as follows:

- The Opening Move (Day 0): Within 20 days of the FDA accepting its application for review, the biosimilar applicant kicks off the dance by providing the reference product sponsor (RPS) with a confidential copy of its entire application and detailed information about its manufacturing process.58 This gives the innovator a deep look into the competitor’s product.

- The Innovator’s List (Day 60): Within 60 days of receiving this information, the RPS must provide the applicant with a list of all patents it believes could reasonably be asserted against the biosimilar.

- The Challenger’s Rebuttal (Day 120): The biosimilar applicant then has 60 days to respond with its own detailed, claim-by-claim analysis, explaining why it believes each patent on the innovator’s list is invalid, unenforceable, or not infringed. The applicant can also provide its own list of patents it believes are relevant.

- The Innovator’s Sur-Rebuttal (Day 180): The RPS then has 60 days to provide a detailed rebuttal to the applicant’s non-infringement and invalidity arguments.

- Negotiating the First Lawsuit (Days 195-250): Following this exchange, the two parties have 15 days to negotiate in good faith to agree on a final list of patents that will be the subject of the first wave of patent litigation. If they cannot agree, the BPCIA provides a specific formula for determining which patents are litigated first.58 The RPS must then file the lawsuit within 30 days.

Any patents identified during the dance but not litigated in this first wave can potentially be litigated in a second wave after the biosimilar manufacturer provides its 180-day notice of commercial marketing.

To Dance or Not to Dance? A Critical Strategic Choice

A pivotal Supreme Court decision in Amgen v. Sandoz clarified a key aspect of this process: the patent dance is not mandatory.66 A biosimilar applicant can choose to opt out of the information exchange entirely.

This decision transforms the dance from a rigid legal requirement into a critical strategic choice.

- Why Dance? Participating in the dance allows the biosimilar applicant to have some control over the scope of the initial litigation. It provides a structured process to narrow the dispute down to the most critical patents and can lead to a more predictable and manageable legal battle.

- Why Sit It Out? An applicant might choose to forgo the dance to protect the confidentiality of its manufacturing processes for as long as possible or to employ a more disruptive legal strategy. However, this choice comes with consequences. If an applicant opts out, it loses control of the process; the RPS can immediately file a patent infringement suit on any patent it chooses. The applicant may also forfeit certain statutory limits on the damages it could face if it is later found to infringe.

Ultimately, the patent dance is best understood not as a legal formality, but as a high-stakes negotiation that takes place under the shadow of impending litigation. Each step is a strategic maneuver designed to signal strength, manage information, and shape the battlefield for the inevitable legal conflict. The decision of whether to participate, and how to engage at each stage, is a complex business calculation aimed at securing the most favorable position for either litigation or an eventual settlement.

Term 11: Evergreening – The Art and Science of Extending Exclusivity

As the expiration date of a blockbuster drug’s core composition of matter patent looms—an event known as the “patent cliff”—innovator companies face the prospect of a catastrophic revenue decline, often 80% or more within the first year of generic entry. In response, the industry has developed a sophisticated set of strategies designed to extend a drug’s period of market exclusivity. This practice is known as “evergreening.” It is one of the most controversial and fiercely debated topics in the pharmaceutical world, sitting at the tense intersection of legitimate innovation and alleged anti-competitive market manipulation.

Defining Evergreening

Evergreening refers to any legal, business, or technological strategy employed by a brand-name drug manufacturer to obtain new patents or other forms of exclusivity on a drug with the effect of extending its monopoly protection beyond the original patent’s expiration date.3 It is a core component of a broader strategy known as “lifecycle management,” which aims to maximize the commercial value of a drug throughout its entire time on the market.

Common Evergreening Tactics

Innovator companies have developed a diverse playbook of evergreening tactics, many of which involve patenting incremental improvements to an existing drug:

- New Formulations: This is a classic technique. A company might take a drug that requires dosing three times a day and develop a new, patented extended-release formulation that only needs to be taken once daily. This can improve patient compliance and may be considered a patentable invention. Examples include AstraZeneca’s Seroquel XR and Bristol-Myers Squibb’s Glucophage XR.3

- New Methods of Use / Indications: A company may discover that a drug approved for one disease is also effective against another. By conducting new clinical trials and securing a patent on this new method of use, it can gain a new period of exclusivity. A famous example is bupropion, which was first patented and marketed as the antidepressant Wellbutrin, and later patented and marketed for smoking cessation as Zyban.3

- Polymorphs and Chiral Switches: These are more technical strategies. A “polymorph” is a different crystalline structure of the same active ingredient, which might have improved properties like better solubility.3 A “chiral switch” involves taking a drug that was a mixture of two mirror-image molecules (enantiomers) and developing a new, patented product containing only the single, more active enantiomer. The blockbuster acid reflux drug Nexium (esomeprazole) is a famous chiral switch of the older drug Prilosec (omeprazole).

- “Product Hopping”: This is a particularly aggressive tactic where a company actively transitions the market from an older product to a newer, patent-protected version just before the original’s patent expires. This can be a “hard switch,” where the old product is pulled from the market entirely, or a “soft switch,” which involves a massive marketing push for the new version while ceasing promotion of the old one.5 The goal is to destroy the market for the impending generic of the old product by ensuring there are no prescriptions for it to be substituted against.

The Controversy: Innovation vs. Manipulation

The debate over evergreening is fierce and polarized.

- The Innovator Argument: Brand companies and their advocates argue that these strategies represent genuine, valuable, incremental innovation. They contend that a new formulation that improves patient adherence or a new indication that treats a previously unmet need is a real medical advance that deserves patent protection. As one industry executive put it, “anything you do to a molecule, as small as it could be, if it results in a clear medical advantage for patients, then it should be protected”. From this perspective, evergreening is simply the natural process of continuing to innovate on a successful platform.75

- The Critic Argument: Critics, including generic manufacturers, patient advocates, and regulators, argue that many of these modifications are trivial and offer little to no therapeutic benefit. They contend that the primary purpose of evergreening is not to help patients but to exploit loopholes in the patent system to block affordable generic competition, costing the healthcare system billions annually.74 Data often cited by critics suggests that as many as 78% of new patents are for modifications to existing drugs rather than for entirely new medicines.

This global debate was famously crystallized in the landmark case of Novartis v. Union of India. India’s patent law contains a unique provision, Section 3(d), which explicitly states that a new form of a known substance is not patentable unless it demonstrates a significant “enhancement of the known efficacy”. When Novartis sought a patent in India for a new crystalline form (a polymorph) of its blockbuster cancer drug Gleevec, the Indian Supreme Court ultimately rejected the application in 2013. The court ruled that while the new form had better bioavailability, Novartis had failed to prove it resulted in an enhanced therapeutic efficacy for the patient.79

The Novartis case highlights the emerging legal and ethical litmus test for evergreening strategies worldwide: the “patient benefit” test. Increasingly, courts, regulators, and even payers are scrutinizing secondary patents and asking a simple question: does this modification provide a meaningful, demonstrable benefit to the patient? A strategy that cannot convincingly answer “yes” to this question is vulnerable to legal challenge, regulatory pushback, and commercial failure.

Term 12: Patent Thicket – Building an Impenetrable IP Fortress

If evergreening is the art of extending a product’s life through a series of individual patents, the “patent thicket” is the strategy of creating a defensive fortress so dense, so complex, and so overlapping that it becomes economically and legally impenetrable to competitors. This is an advanced and highly controversial tactic, particularly prevalent in the world of biologics, where the goal shifts from simply protecting an invention to creating a legal and financial barrier so formidable that it deters challenges altogether.

Defining the Thicket

A patent thicket is a dense web of numerous, often overlapping, patents covering a single product.3 This strategy goes far beyond securing the core composition of matter patent and a few key secondary patents. Instead, it involves filing for and obtaining dozens, or even hundreds, of patents covering every conceivable aspect of the drug: every minor variation in its formulation, every step of its manufacturing process, every potential method of use, every component of its delivery device, and more.82

The strategic brilliance—and the source of the controversy—of the patent thicket lies not in the strength of any single patent within it. Many of the patents in a thicket may be individually weak or narrow. Its power comes from sheer volume. The strategy weaponizes the cost and complexity of the legal system itself. A potential biosimilar competitor doesn’t just have to invalidate one or two key patents; they face the daunting and financially ruinous prospect of having to litigate and invalidate dozens or hundreds of them to clear a path to market.84 The cost of such litigation can run into the tens or hundreds of millions of dollars, creating an economic barrier that can be more effective than any single patent’s legal claims.

Case Study: AbbVie’s Humira – The Archetypal Thicket

The poster child for the patent thicket strategy is AbbVie’s blockbuster biologic drug, Humira. For what was essentially a single product, AbbVie constructed an IP fortress of staggering proportions, filing over 247 patent applications in the U.S. alone, which resulted in more than 130 granted patents.86

The commercial impact of this strategy was profound. While biosimilar versions of Humira launched in Europe in 2018, where AbbVie held far fewer patents, the U.S. patent thicket successfully delayed any biosimilar competition until 2023. This five-year delay is estimated to have cost the U.S. healthcare system over $19 billion.83

AbbVie’s strategy inevitably drew antitrust lawsuits, with plaintiffs arguing that the creation of the thicket itself was an illegal, anti-competitive act designed to unlawfully maintain a monopoly. However, in a landmark 2022 decision, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit dismissed these claims.87 The court reasoned that the patent laws place no limit on the number of patents an inventor can obtain for their inventions. It concluded that as long as the patents were obtained legitimately through the USPTO and not through fraud, the act of accumulating them—even in large numbers—is not an antitrust violation. The court stated that sifting through “weak” or “irrelevant” patents is the job of the courts hearing the patent infringement cases, not a basis for a separate antitrust lawsuit.

Antitrust Implications and Regulatory Scrutiny

Despite the setback for plaintiffs in the Humira case, patent thickets remain under intense scrutiny. Regulators like the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and members of Congress view the practice as a significant abuse of the patent system that harms competition and keeps drug prices artificially high for consumers.90

The legal and legislative debate is far from settled. The core question remains: at what point does a legitimate and aggressive patenting strategy cross the line into unlawful monopolization? While the Humira decision has made it more difficult to challenge a thicket on antitrust grounds alone, the immense economic and political pressure to address high drug prices ensures that this will remain a central battleground in the ongoing war between pharmaceutical innovation and affordable access to medicine.

Conclusion: Translating Knowledge into Competitive Supremacy

We have journeyed through the complex and high-stakes lexicon of pharmaceutical patents, deconstructing 12 essential terms that define the industry’s competitive landscape. As we have seen, these are not isolated concepts. They are deeply interconnected components of a strategic game played out at the intersection of science, law, and commerce.

The journey begins with the foundational Patent, whose effective life is eroded by the long road to approval, creating the economic pressure for all that follows. This is layered with Regulatory Exclusivity, a parallel track of protection granted by the FDA. The most powerful of these patents is the Composition of Matter patent, the crown jewel that enables the entire lifecycle management playbook.

The rules of engagement for small-molecule drugs are dictated by the Hatch-Waxman Act, which uses the Orange Book as its central battlefield map. Generic companies launch their assault with a Paragraph IV Certification, a formal challenge that triggers a high-stakes legal battle. The prize for the first successful challenger is the lucrative 180-Day Exclusivity.

For biologics, a separate universe exists, governed by the BPCIA. Here, competition comes from Biosimilars and Interchangeable products, and patent disputes are resolved through the intricate “Patent Dance.”

Finally, we see how innovator companies play an advanced game, employing strategies like Evergreening to incrementally extend a drug’s life and building formidable Patent Thickets to create nearly impenetrable legal fortresses that deter competition through sheer economic force.

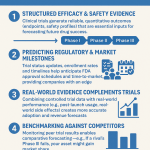

Mastery of this intricate web is impossible without access to timely, accurate, and comprehensive data. In this fast-moving environment, knowledge that is six months out of date is not just obsolete; it is a liability. This is where sophisticated competitive intelligence platforms like DrugPatentWatch become indispensable strategic assets.

Such platforms provide the critical, real-time data necessary to transform the knowledge in this guide into a tangible competitive edge. They allow you to:

- Track Patent Expirations and Exclusivity Dates: Identify the precise moment a drug becomes vulnerable to a Paragraph IV challenge or biosimilar entry.47

- Monitor Litigation and Settlements: Analyze the outcomes of ongoing patent disputes to assess the strength of a competitor’s portfolio and predict market entry dates for generics.47

- Dissect Competitor Portfolios: Scrutinize the patent filings of your rivals to anticipate their evergreening strategies and identify the formation of patent thickets before they become impenetrable.48

- Forecast Market Dynamics: Use comprehensive data on drug pipelines, clinical trials, and regulatory statuses to manage supply chains, set budgets, and make informed portfolio management decisions.47

In short, understanding the 12 terms in this report provides the “what” and the “why” of pharmaceutical IP strategy. A powerful data platform provides the “who,” “when,” and “how”—the actionable intelligence that allows you to outmaneuver your competition and secure your position in this demanding market. The language of patents is indeed the language of power, and with the right knowledge and the right tools, you will be equipped to speak it fluently.

Key Takeaways

- Dual Systems of Protection: Pharmaceutical market protection relies on two independent but concurrent systems: patents from the USPTO and regulatory exclusivities from the FDA. A successful strategy requires mastering and layering both.

- Effective Life vs. Statutory Term: The 20-year statutory patent term is misleading. The 7- to 12-year effective market life after FDA approval creates immense economic pressure that drives all advanced lifecycle management strategies.

- Hatch-Waxman and BPCIA Are Different Worlds: The legal and regulatory frameworks for small molecules (Hatch-Waxman) and biologics (BPCIA) are fundamentally different. Strategies from one cannot be applied to the other.

- Conflict by Design: The Hatch-Waxman Act’s Paragraph IV/30-month stay mechanism is an intentional system designed to force and manage patent disputes before a generic launches, making litigation a predictable part of the business cycle.

- The Power of the First Filer: The 180-day exclusivity for the first generic challenger is the single most powerful economic incentive in the small-molecule space, driving a “race to file” and shaping all competitive behavior around patent expiry.

- The End of the Two-Tier Biosimilar Market: The FDA’s 2024 guidance eliminating the need for switching studies will likely make “interchangeability” the standard for biosimilars, collapsing the two-tiered system and accelerating price competition.

- Evergreening’s Litmus Test: The central debate over evergreening strategies increasingly hinges on a “patient benefit” test. Modifications that lack a clear, demonstrable therapeutic advantage are vulnerable to legal, regulatory, and commercial challenges.

- Patent Thickets Weaponize Cost: The strategic power of a patent thicket is not necessarily in the legal strength of its individual patents, but in its ability to make the cost of litigation so prohibitively high that it deters competition on economic grounds alone.

- Data is the Ultimate Weapon: Navigating this complex landscape is impossible without continuous, real-time competitive intelligence. Platforms that track patents, litigation, and regulatory milestones are essential tools for turning this knowledge into actionable strategy.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. Can a pharmaceutical patent be extended more than once?

This is a nuanced question. A single patent can generally only receive one Patent Term Extension (PTE) under the Hatch-Waxman Act for regulatory delay. The law explicitly states that “in no event shall more than one patent be extended…for the same regulatory review period for any product”. However, a company can achieve a similar outcome of extending market exclusivity for a product through multiple avenues. For instance, the same patent that received a PTE could also benefit from a 6-month Pediatric Exclusivity extension. More commonly, companies file for and obtain new, separate patents on modifications to the original drug (e.g., a new formulation, a new method of use). Each of these secondary patents has its own 20-year term, effectively extending the product’s overall patent protection, which is the core principle of evergreening. So, while one patent gets one PTE, a single drug product can be protected by a succession of different patents over time.

2. What happens if a patent is delisted from the Orange Book after a Paragraph IV challenge is filed? Does the 30-month stay get affected?

If a court orders a patent to be delisted from the Orange Book, as in the Teva v. Amneal case, it has significant consequences for a generic filer. Once a patent is delisted, an ANDA applicant is no longer required to maintain a certification to it. If the delisting happens before a 30-month stay has been triggered by that patent, then no stay can be triggered. The more complex question is what happens if a stay is already in effect. While the regulations are complex, the logical consequence of a court-ordered delisting based on a finding that the patent was improperly listed is that the legal basis for the 30-month stay associated with that patent would be eliminated. The delisting effectively confirms the patent should not have been a barrier to the ANDA in the first place, and therefore the stay, which is a direct consequence of challenging that listed patent, should be nullified or vacated. This is a powerful new tool for generics to not only clear a path to market but also potentially shorten or eliminate the 30-month waiting period.

3. How do Patent Term Extensions (PTE) and regulatory exclusivities like NCE exclusivity interact? Can a drug benefit from both at the same time?

Yes, a drug can absolutely benefit from both simultaneously, and understanding their interaction is key to IP strategy. They are independent protections that run concurrently and shield against different threats.11 A Patent Term Extension (PTE) extends the life of a specific patent, protecting the drug from anyone infringing that patent’s claims. New Chemical Entity (NCE) exclusivity, on the other hand, is a direct instruction to the FDA, preventing the agency from approving a competing generic application for five years, regardless of the patent status. For example, a new drug might launch with 10 years remaining on its core patent and 5 years of NCE exclusivity. For the first 5 years, it is protected by both: no one can infringe the patent, AND the FDA won’t approve a generic. For the next 5 years (after NCE exclusivity expires), it is protected only by the patent. A PTE could then extend that patent’s life even further.

4. Is ‘product hopping’ a viable strategy for biologic drugs, and how does it differ from small-molecule product hopping?

Yes, product hopping is a viable, and frequently used, strategy for biologics, but it is a fundamentally different game than for small molecules. For small-molecule drugs, a “hop” can be a relatively minor change (e.g., tablet to capsule) and is often a defensive, last-minute tactic to disrupt automatic pharmacy substitution of an incoming generic. For biologics, the scientific and manufacturing complexity is immense. A “hop” to a new formulation or delivery device is a major, multi-year R&D endeavor costing hundreds of millions of dollars. Therefore, biologic product hopping is less of a defensive tweak and more of a long-term, offensive strategy to launch a “next-generation” product that is positioned as clinically superior. The goal is the same—to migrate the market away from the original product before biosimilars arrive—but the investment, timeline, and need to demonstrate genuine clinical improvement are far greater.

5. With the rise of “patent thickets,” is it still economically viable for generic and biosimilar companies to challenge patents?

Yes, but it has become a game of strategic selection and calculated risk. While a patent thicket like Humira’s can seem impenetrable, it is not economically feasible for most companies to challenge every patent on every drug. Instead, the viability of a challenge depends on several factors. First, the size of the prize: blockbuster drugs with billions in annual sales can justify litigation costs that smaller drugs cannot. Second, the quality of the patents: challengers use services like DrugPatentWatch to analyze patent portfolios and target the weakest links, often secondary patents on formulations or methods of use, which are easier to invalidate than core composition of matter patents. Third, the high success rate of settlements: while generics have roughly a 50/50 chance at trial, one study found a 76% “success rate” when settlements (which guarantee an entry date and eliminate risk) are included. The rise of patent thickets has made the upfront due diligence more critical than ever, but for the right product with the right vulnerabilities, the potential ROI remains a powerful incentive.

References

- Patent linkage: Balancing patent protection and generic entry – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 9, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/patent-linkage-resolving-infringement/

- An International Guide to Patent Case Management for Judges – WIPO, accessed August 9, 2025, https://www.wipo.int/patent-judicial-guide/en/full-guide/united-states/10.13.2

- Filing Strategies for Maximizing Pharma Patents: A Comprehensive …, accessed August 9, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/filing-strategies-for-maximizing-pharma-patents/

- Patent Defense Isn’t a Legal Problem. It’s a Strategy Problem. Patent Defense Tactics That Every Pharma Company Needs – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 9, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/patent-defense-isnt-a-legal-problem-its-a-strategy-problem-patent-defense-tactics-that-every-pharma-company-needs/

- Drug Patent Life: The Complete Guide to Pharmaceutical Patent …, accessed August 9, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/how-long-do-drug-patents-last/

- Evolving Pharmaceutical Strategies in a Post-Blockbuster World: Navigating Innovation, Access, and Market Dynamics – Drug Patent Watch, accessed August 9, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/evolving-pharmaceutical-strategies-in-a-post-blockbuster-world/

- IP Principles: Supporting the Search for Breakthroughs – Pfizer, accessed August 9, 2025, https://www.pfizer.com/about/responsibility/intellectual-property

- Intellectual Property | PhRMA, accessed August 9, 2025, https://phrma.org/policy-issues/intellectual-property

- The Complete Guide to Patenting Prescription and OTC Drug Inventions – PatentPC, accessed August 9, 2025, https://patentpc.com/blog/complete-guide-patenting-prescription-otc-drug-inventions

- Optimizing Your Drug Patent Strategy: A Comprehensive Guide for Pharmaceutical Companies – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 9, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/optimizing-your-drug-patent-strategy-a-comprehensive-guide-for-pharmaceutical-companies/

- Patents and Exclusivity | FDA, accessed August 9, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/media/92548/download

- Patent litigation 101 | Legal Blog, accessed August 9, 2025, https://legal.thomsonreuters.com/blog/patent-litigation-101/

- The Hatch-Waxman Act: A Primer – EveryCRSReport.com, accessed August 9, 2025, https://www.everycrsreport.com/reports/R44643.html

- Intellectual Property – EFPIA, accessed August 9, 2025, https://www.efpia.eu/about-medicines/development-of-medicines/intellectual-property/

- Cracking the Code: A Strategic Guide to Reverse Engineering Drugs Using Patent Intelligence – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 9, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/using-drug-patent-information-to-synthesize-drugs/

- Drug Patents: Essential Guide to Pharmaceutical Patent Protection, accessed August 9, 2025, https://www.upcounsel.com/how-long-does-a-drug-patent-last

- Determinants of Market Exclusivity for Prescription Drugs in the United States – Commonwealth Fund, accessed August 9, 2025, https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/journal-article/2017/sep/determinants-market-exclusivity-prescription-drugs-united

- Pharmaceutical Patent Regulation in the United States – The Actuary …, accessed August 9, 2025, https://www.theactuarymagazine.org/pharmaceutical-patent-regulation-in-the-united-states/

- Intellectual property rights: An overview and implications in pharmaceutical industry – PMC, accessed August 9, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3217699/

- Drug Pricing and the Law: Pharmaceutical Patent Disputes – Congress.gov, accessed August 9, 2025, https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/IF11214

- Hatch-Waxman 101 – Fish & Richardson, accessed August 9, 2025, https://www.fr.com/insights/thought-leadership/blogs/hatch-waxman-101-3/

- Patent Litigation in the Pharmaceutical Industry: Key Considerations, accessed August 9, 2025, https://patentpc.com/blog/patent-litigation-in-the-pharmaceutical-industry-key-considerations

- Hatch Waxman Litigation 101 | DLA Piper, accessed August 9, 2025, https://www.dlapiper.com/insights/publications/2020/06/ipt-news-q2-2020/hatch-waxman-litigation-101/

- Patent Use Codes for Pharmaceutical Products: A Comprehensive …, accessed August 9, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/patent-use-codes-for-pharmaceutical-products-a-comprehensive-analysis/

- Hatch-Waxman Litigation 101: The Orange Book and the Paragraph IV Notice Letter, accessed August 9, 2025, https://www.dlapiper.com/insights/publications/2020/06/ipt-news-q2-2020/hatch-waxman-litigation-101

- Hatch-Waxman 201 – Fish & Richardson, accessed August 9, 2025, https://www.fr.com/insights/thought-leadership/blogs/hatch-waxman-201-3/

- Patent Listing in FDA’s Orange Book – Congress.gov, accessed August 9, 2025, https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/IF12644

- Landmark Ruling Reshapes Pharmaceutical Patent Litigation – Today’s General Counsel, accessed August 9, 2025, https://todaysgeneralcounsel.com/landmark-ruling-reshapes-pharmaceutical-patent-litigation/

- Teva Branded Pharm. Products R&D, Inc. v. Amneal Pharms. of NY, LLC – Robins Kaplan, accessed August 9, 2025, https://www.robinskaplan.com/newsroom/insights/teva-branded-pharm-v-amneal-pharms

- Teva v. Amneal: Reshaping Generic Drug Rights | News – Haynes Boone, accessed August 9, 2025, https://www.haynesboone.com/news/publications/teva-v-amneal-reshaping-generic-drug-rights

- Teva v. Amneal Ruling Interprets Orange Book Listing Statute, Affirms Delisting of Device Patents – Cooley, accessed August 9, 2025, https://www.cooley.com/news/insight/2025/2025-01-02-teva-v-amneal-ruling-interprets-orange-book-listing-statute-affirms-delisting-of-device-patents

- Federal Circuit Affirms Device Patent Delisting in Teva v. Amneal – American Bar Association, accessed August 9, 2025, https://www.americanbar.org/groups/antitrust_law/resources/newsletters/federal-circuit-affirms-teva-amneal/

- FTC Statement on Appellate Court Decision Ordering Delisting of Teva Inhaler Patents, accessed August 9, 2025, https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/news/press-releases/2024/12/ftc-statement-appellate-court-decision-ordering-delisting-teva-inhaler-patents

- What is Hatch-Waxman Act? – DDReg Pharma, accessed August 9, 2025, https://www.ddregpharma.com/what-is-hatch-waxman-act

- Patent Terminology – Legal Advantage, accessed August 9, 2025, https://legaladvantage.net/knowledge-center/patent-terminology/

- What Every Pharma Executive Needs to Know About Paragraph IV Challenges, accessed August 9, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/what-every-pharma-executive-needs-to-know-about-paragraph-iv-challenges/

- Navigating the Complexities of Paragraph IV – Number Analytics, accessed August 9, 2025, https://www.numberanalytics.com/blog/navigating-paragraph-iv-complexities

- Patent Litigation Statistics: An Overview of Recent Trends – PatentPC, accessed August 9, 2025, https://patentpc.com/blog/patent-litigation-statistics-an-overview-of-recent-trends

- Generic Pharmaceutical Patent and FDA Law: Navigating the Complex Landscape, accessed August 9, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/generic-pharmaceutical-patent-and-fda-law/

- ‘Pay to Delay’ Settlements in Patent Litigation | NBER, accessed August 9, 2025, https://www.nber.org/digest/jul16/pay-delay-settlements-patent-litigation

- Hatch-Waxman Act | Practical Law – Westlaw, accessed August 9, 2025, https://content.next.westlaw.com/practical-law/document/I2e45aeaf642211e38578f7ccc38dcbee/Hatch-Waxman-Act?viewType=FullText&transitionType=Default&contextData=(sc.Default)

- Patent Certifications and Suitability Petitions – FDA, accessed August 9, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/abbreviated-new-drug-application-anda/patent-certifications-and-suitability-petitions

- Paragraph IV Explained – ParagraphFour.com, accessed August 9, 2025, https://paragraphfour.com/paragraph-iv-explained/

- Should We Settle? Considerations For Generic Companies Before Settling Hatch-Waxman Litigation – Cantor Colburn, accessed August 9, 2025, https://www.cantorcolburn.com/media/news/40_201110_Sept%202011%20Shoudl%20We%20Settle%20-%20Hatch-Waxman%20Litigation.pdf

- “Authorized Generics” Windfall to consumers or new strategy to harm competition?, accessed August 9, 2025, https://www.ehcca.com/presentations/fdasymposium2/balto_t5.ppt

- Drug Competition Series – Analysis of New Generic Markets Effect of Market Entry on Generic Drug Prices – HHS ASPE, accessed August 9, 2025, https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/510e964dc7b7f00763a7f8a1dbc5ae7b/aspe-ib-generic-drugs-competition.pdf

- DrugPatentWatch | Software Reviews & Alternatives – Crozdesk, accessed August 9, 2025, https://crozdesk.com/software/drugpatentwatch

- DrugPatentWatch is a time-saving powerhouse, accessed August 9, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/

- Key Strategies for Successfully Challenging a Drug Patent – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 9, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/key-strategies-for-successfully-challenging-a-drug-patent/

- Biosimilars and Interchangeable Biosimilars – FDA, accessed August 9, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/media/154992/download

- BPCIA: Beyond the Hatch-Waxman Act – Pharmaceutical Law Group, accessed August 9, 2025, https://www.pharmalawgrp.com/bpcia/

- Biologics and Biosimilars: Background and Key Issues – Congress.gov, accessed August 9, 2025, https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/R44620

- “SHALL”WE DANCE?INTERPRETING THE BPCIA’S PATENT PROVISIONS – Berkeley Technology Law Journal, accessed August 9, 2025, https://btlj.org/data/articles2016/vol31/31_ar/0659_0686_Tanaka_WEB.pdf

- What is the BPCIA? | Winston & Strawn Law Glossary | Winston …, accessed August 9, 2025, https://www.winston.com/en/legal-glossary/bpcia

- Commemorating the 15th Anniversary of the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act, accessed August 9, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/cder-conversations/commemorating-15th-anniversary-biologics-price-competition-and-innovation-act

- Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act – mdi Consultants, accessed August 9, 2025, https://mdiconsultants.com/biologics-price-competition-innovation-act/

- Unofficial Legislative History of the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act 2009, An, accessed August 9, 2025, https://scholarship.law.missouri.edu/facpubs/557/

- Pharmaceutical Patent Litigation and the Emerging Biosimilars: A …, accessed August 9, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5394541/

- Biosimilar Interchangeability: FDA Designation, Marketing Exclusivity, Guidance, and Future Trends – IPD Analytics, accessed August 9, 2025, https://www.ipdanalytics.com/post/biosimilar-interchangeability-fda-designation-marketing-exclusivity-guidance-and-future-trends

- 9 Things to Know About Biosimilars and Interchangeable Biosimilars – FDA, accessed August 9, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/things-know-about/9-things-know-about-biosimilars-and-interchangeable-biosimilars