Introduction: The Biosimilar Promise and the Perilous US Market

The advent of biologic medicines represents one of the most significant advances in modern therapeutics, offering transformative treatments for complex and chronic conditions ranging from cancer and autoimmune diseases to diabetes and macular degeneration.1 These large, complex molecules, derived from living organisms, have revolutionized patient care but have come at a staggering cost. In the United States, biologics have become the single largest driver of pharmaceutical spending. Despite being used by less than 2% of the patient population, they accounted for a disproportionate 46% of all U.S. drug expenditures in 2021 2 and more than half of all prescription drug spending in recent years.3 This economic reality has placed immense strain on patients, payers, and the healthcare system as a whole, creating an urgent need for a competitive counterbalance.

That counterbalance was envisioned in the form of biosimilars—highly similar, lower-cost versions of originator biologics. The promise of biosimilars is twofold and profound: first, to introduce robust market competition that drives down the exorbitant prices of biologic therapies, and second, to expand patient access to these often life-saving treatments. The potential for savings is not theoretical; it is a demonstrated reality. In 2023 alone, generic and biosimilar medicines combined saved the U.S. healthcare system a record $445 billion, contributing to over $3 trillion in savings over the preceding decade.5 Specifically, biosimilars have generated $36 billion in savings since the first product launched in 2015, with their average sales price being roughly 50% lower than the reference product’s price at the time of launch.5

Yet, despite this clear and compelling promise, the U.S. market has presented a paradox. More than 15 years after Congress passed the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA) to create a pathway for their approval, the adoption of biosimilars in the United States has been uniquely challenging, lagging significantly behind more mature markets like the European Union.4 The path from FDA approval to widespread patient use is not a straightforward sprint but a perilous gauntlet, fraught with interconnected barriers that have systematically blunted the competitive impact of these products.

This report will dissect the formidable challenges that have defined the U.S. biosimilar experience. We will explore the intricate and costly regulatory framework that governs their approval, a landscape where “abbreviated” does not mean simple or inexpensive. We will navigate the legal minefield of the U.S. patent system, where originator manufacturers have perfected the use of “patent thickets” to delay competition for years. We will analyze the commercial battlefield, a territory dominated by powerful intermediaries like Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs) whose financial incentives are often fundamentally misaligned with the goal of promoting the lowest-cost therapies. Finally, we will examine the persistent psychological and educational hurdles that create hesitancy among the physicians who prescribe and the patients who use these critical medicines. By deconstructing each of these barriers and analyzing their complex interplay, we can begin to understand not only why the biosimilar promise has been slow to materialize in the U.S., but also what strategic, legislative, and commercial shifts are necessary to finally unlock its full potential.

The Blueprint for Competition: Deconstructing the BPCIA and the Regulatory Framework

The foundation of the U.S. biosimilar market is the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA) of 2009, landmark legislation enacted as part of the Affordable Care Act.1 Modeled conceptually after the Hatch-Waxman Act that created the generic drug market decades earlier, the BPCIA was designed to forge a regulatory pathway where none had existed, balancing the need for lower-cost competition with incentives for continued innovation.1 However, the scientific realities of biologics have made this pathway inherently more complex, costly, and contentious than its small-molecule counterpart, creating the first and most fundamental set of barriers to market entry.

A Tale of Two Follow-Ons: Why Biosimilars Are Not Generics

To comprehend the challenges facing the biosimilar market, one must first grasp the essential scientific distinction between a biosimilar and a generic drug. This difference is the seed from which nearly every other barrier—regulatory, commercial, and psychological—grows.

Generic drugs are follow-on versions of traditional, small-molecule pharmaceuticals that are chemically synthesized. Their active ingredients are relatively simple and can be replicated with precision, resulting in a product that is identical to the brand-name drug.13 The approval process for a generic, therefore, focuses on demonstrating “bioequivalence”—proving that the generic drug behaves identically to the brand-name drug in the human body.15

Biologics, and by extension biosimilars, inhabit a different scientific universe. They are large, intricate molecules, often proteins, that are not chemically synthesized but are “grown” in living systems such as yeast, bacteria, or animal cells.13 This manufacturing process is inherently variable; even with an identical genetic blueprint, minor, natural variations occur from batch to batch. This reality is so central to the field that it has given rise to the industry mantra: “the process is the product”.17 Because of this natural variability, it is impossible to create an exact, identical copy of a biologic. Instead, a biosimilar is engineered to be “highly similar” to an already FDA-approved biologic (the “reference product”), with no clinically meaningful differences in terms of safety, purity, and potency.1

This fundamental distinction—”identical” versus “highly similar”—has profound downstream consequences. First, it necessitates a far more complex, data-intensive, and expensive regulatory approval process to satisfy the FDA that the minor structural differences have no clinical impact. This high cost of entry is a powerful economic barrier. Second, it creates a psychological gap for clinicians and patients. Decades of experience have made stakeholders comfortable with the concept of identical generics, but the idea of a “similar” biologic, especially for treating a serious illness, can sow seeds of doubt and hesitancy. This requires extensive and ongoing education to overcome. Finally, this perceived gap provides a strategic opening for originator manufacturers to engage in marketing and messaging campaigns designed to amplify uncertainty and question the safety and efficacy of competing biosimilars, a tactic that would be untenable in the world of identical generics.

The FDA’s “Totality of the Evidence” Standard: A Rigorous—and Costly—Path to Approval

The BPCIA created an “abbreviated” licensure pathway for biosimilars, but this term is often misunderstood from a business and operational perspective.19 It is abbreviated only in the sense that a biosimilar manufacturer can leverage the FDA’s previous finding that the reference product is safe and effective, thereby avoiding the need to repeat the full slate of costly and time-consuming clinical trials that the originator conducted.18 It is by no means a simple or inexpensive process.

The FDA employs a “stepwise” approach to biosimilar approval, evaluating the “totality of the evidence” submitted by the manufacturer.18 This process is built upon a massive foundation of comparative analytical studies. Using a battery of state-of-the-art technologies, the developer must meticulously characterize the proposed biosimilar’s structure and function and compare it to the reference product, demonstrating that they are highly similar.17 This analytical comparison is the cornerstone of the approval process.

From there, the developer proceeds to the next steps to address any residual uncertainty. These may include:

- Animal Studies: To assess toxicology and pharmacology if deemed necessary.18

- Clinical Pharmacology Studies: To demonstrate that the biosimilar has similar pharmacokinetics (PK, how the drug moves through the body) and pharmacodynamics (PD, what the drug does to the body) as the reference product. This phase also includes an assessment of immunogenicity—the potential for the product to provoke an immune response.18

- Comparative Clinical Studies: In some cases, the FDA may require an additional clinical trial directly comparing the safety and efficacy of the biosimilar to the reference product in patients to confirm that there are no clinically meaningful differences.18

This rigorous, multi-stage process represents a monumental undertaking. The development of a single biosimilar typically costs between $100 million and $250 million and can take 7 to 8 years to complete.22 This stands in stark contrast to the development of a small-molecule generic drug, which usually costs just $1 million to $4 million.22

The immense cost and time commitment of the biosimilar approval pathway acts as a powerful economic barrier to entry. It naturally limits the pool of potential competitors for any given biologic to a small number of large, well-capitalized pharmaceutical companies with deep scientific and manufacturing expertise.22 Unlike the generic market, where dozens of competitors can emerge for a single drug, leading to rapid and deep price erosion, the biosimilar market is often an oligopoly. This structural difference, born from the scientific complexity of biologics and the resulting regulatory rigor, fundamentally tempers the competitive dynamics and the ultimate level of cost savings that can be achieved.

Table 1: Biosimilars vs. Generic Drugs: A Comparative Overview

| Feature | Generic Drugs | Biosimilar Drugs |

| Active Ingredient | Identical to reference product | “Highly similar” to reference product 15 |

| Size & Complexity | Small, simple molecules | Large, complex molecules (e.g., proteins) 13 |

| Manufacturing | Chemical synthesis | Produced in living cells (e.g., yeast, bacteria) 13 |

| Natural Variability | None; chemically identical | Inherent, minor variations between batches 15 |

| Approval Standard | Bioequivalence | Totality of the Evidence 15 |

| Development Cost | $1 million – $4 million 22 | $100 million – $250 million 22 |

| Substitution | Automatic pharmacy-level substitution | Requires prescription or “interchangeable” status 25 |

The Interchangeability Conundrum: A Shifting—and Contentious—Designation

A unique and historically significant feature of the U.S. biosimilar framework is the concept of “interchangeability.” An interchangeable biosimilar is one that has met additional regulatory requirements, allowing it to be substituted for the reference product at the pharmacy without the direct intervention of the prescribing physician, much like a generic drug.25 This substitution is still governed by a patchwork of individual state pharmacy laws, which often include requirements for patient notification or consent.27

Historically, achieving this coveted designation has been a major hurdle. In addition to proving biosimilarity, a manufacturer seeking an interchangeable designation was generally required to conduct an additional, expensive, and time-consuming “switching study”.20 These studies typically involved alternating patients between the reference product and the proposed interchangeable biosimilar multiple times to demonstrate that doing so posed no increased safety risk or diminished efficacy compared to continuous use of the reference product.25

This additional requirement created a de facto two-tiered system of biosimilars: “regular” biosimilars and the supposedly superior “interchangeable” ones. This distinction, while intended to provide an extra layer of confidence for pharmacy-level substitution, inadvertently fueled physician and patient hesitancy. The lack of an interchangeable designation was often misinterpreted as a sign of lower quality or safety, when in reality it may have simply meant the manufacturer chose not to incur the cost and time of a switching study.16 This perception barrier was so significant that some have referred to the interchangeability designation as a “poison pill” that has hindered broader biosimilar adoption.30

Recognizing this, the regulatory landscape is now undergoing a pivotal shift. In June 2024, the FDA issued draft guidance proposing to eliminate the general expectation for switching studies to demonstrate interchangeability.31 The agency stated that years of experience have shown the risk associated with switching to be insignificant, and that the determination can be made based on the same robust analytical and clinical data used to establish biosimilarity.31 This move, strongly supported by the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) as a pro-competitive measure, is a major step toward leveling the playing field and dismantling a key regulatory barrier.32

However, while the regulatory framework evolves, the commercial market has been moving even faster. The recent experience with adalimumab (Humira) biosimilars, which will be explored in detail later in this report, has raised profound questions about the practical relevance of the interchangeability designation in today’s market. In that case, biosimilar market share was dictated almost entirely by the formulary decisions of PBMs, not by interchangeability status.33 A PBM can effectively force a switch to a

non-interchangeable biosimilar simply by removing the originator and other competitors from its formulary. This suggests that in the pharmacy-benefit space, powerful commercial gatekeepers, not pharmacists, have become the true agents of substitution. This market reality is further complicated by ongoing legislative efforts like the Biosimilar Red Tape Elimination Act, which seeks to deem all approved biosimilars as interchangeable upon approval.30 Such a law could create a direct conflict with PBMs’ increasingly common strategy of creating exclusive formularies around a single, partnered biosimilar, setting the stage for future clashes between regulatory policy and commercial practice.

The Patent Gauntlet: Intellectual Property as a Primary Barrier

If the regulatory pathway is the first hurdle a biosimilar developer must clear, the intellectual property (IP) landscape is the second, and it is a far more treacherous and unpredictable gauntlet. In the United States, the patent system has been strategically leveraged by originator biologic manufacturers to construct formidable, multi-layered defenses that can delay competition for years beyond the expiration of a drug’s core patent. Navigating this legal minefield requires immense financial resources, sophisticated legal strategy, and an ironclad tolerance for risk.

The “Patent Dance”: A High-Stakes Legal Chess Match

At the heart of the BPCIA’s IP framework is a complex and highly structured process for exchanging patent information and resolving disputes prior to a biosimilar’s launch. Colloquially known as the “patent dance,” this process was intended to bring order and predictability to biosimilar patent litigation.4

The dance begins when a biosimilar applicant submits its abbreviated Biologics License Application (aBLA) to the FDA. Within 20 days of the FDA accepting the application, the applicant must provide a copy of the aBLA and detailed information about its manufacturing process to the reference product sponsor (RPS).37 This kicks off a rigid, multi-step sequence of information exchanges with strict deadlines:

- The RPS has 60 days to provide the applicant with a list of all patents it believes could be infringed.

- The applicant then has 60 days to respond with its own list of patents it believes are relevant and provide a detailed, claim-by-claim analysis explaining why the RPS’s patents are invalid, unenforceable, or not infringed.

- The RPS then has another 60 days to provide a rebuttal to the applicant’s arguments.39

Following this exchange, the parties are supposed to negotiate in good faith to agree on a final list of patents to be litigated in a “first wave” of litigation. If they cannot agree, a statutory mechanism dictates how many patents each side can put forward for this initial lawsuit.38

A landmark 2017 Supreme Court decision in Sandoz v. Amgen established that this intricate dance is entirely optional for the biosimilar applicant.37 An applicant can choose to forgo the process entirely. However, this is a strategic decision with significant consequences. Opting out of the dance means ceding control of the litigation process to the originator, who can then immediately file a declaratory judgment action for infringement on any and all patents it believes are relevant, without the limitations imposed by the dance’s negotiation phase.38

In practice, the patent dance has often devolved from its intended purpose as a streamlined dispute resolution mechanism into a war of attrition. The sheer volume of patents, the complexity of the arguments, and the tight deadlines create a high-pressure environment that tests the financial endurance and legal preparedness of the biosimilar challenger. For the originator, who has had years to meticulously build its patent portfolio and plan its litigation strategy, the dance is familiar territory. For the biosimilar developer, it represents a massive, front-loaded legal expense and a period of profound business uncertainty, acting as a powerful deterrent long before the product has any chance of generating revenue.

Table 2: The BPCIA “Patent Dance” at a Glance

| Step | Action | Timeline |

| 1 | FDA accepts the biosimilar application (aBLA). | Day 0 |

| 2 | Biosimilar applicant provides aBLA and manufacturing info to the originator (RPS). | Within 20 days of FDA acceptance 39 |

| 3 | RPS provides a list of patents it believes could be infringed. | Within 60 days of receiving the aBLA 39 |

| 4 | Biosimilar applicant provides its detailed statement on non-infringement/invalidity. | Within 60 days of receiving the RPS patent list 39 |

| 5 | RPS provides its detailed rebuttal statement on infringement and validity. | Within 60 days of receiving the applicant’s statement 39 |

| 6 | Parties negotiate in good faith to agree on patents for first-wave litigation. | For 15 days after the RPS rebuttal 39 |

| 7 | If no agreement, parties exchange lists of patents to be litigated. | Following the 15-day negotiation period 38 |

| 8 | RPS files first-wave patent infringement lawsuit. | Within 30 days of the patent list exchange 38 |

Clearing the Thicket: How Originators Use Dense Patent Webs to Delay Competition

The most formidable IP barrier is not any single patent, but the strategic accumulation of dozens or even hundreds of overlapping patents around a single biologic product—a strategy known as creating a “patent thicket”.4 These thickets are not designed to protect a single core invention, but to create a dense and tangled legal web that is prohibitively expensive and risky for a biosimilar competitor to challenge.41 The patents in a thicket can cover not only the primary molecule but also secondary aspects like specific formulations, methods of manufacturing, purification processes, and every new clinical use (indication) for which the drug is approved.17

The case of AbbVie’s Humira (adalimumab) is the quintessential example of this strategy in action. In the United States, AbbVie constructed a patent thicket of over 165 granted patents and more than 100 pending applications.40 This formidable legal fortress successfully delayed the market entry of FDA-approved adalimumab biosimilars for five years longer than in Europe, where AbbVie held far fewer patents. The economic consequences of this delay were staggering, costing the U.S. healthcare system an estimated $19 billion or more.40 The scale of litigation is also vastly different; data shows that in the U.S., originator companies assert between 11 and 65 patents per product in biosimilar litigation, a number that far exceeds what is seen in countries like Canada and the United Kingdom.4

This phenomenon of hyper-aggressive patenting is a uniquely American problem, driven by deliberate policy choices. A historically permissive patent examination environment at the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) has made it relatively easy for companies to obtain numerous, often weak and overlapping, follow-on patents.40 This is coupled with a legal system where the cost of challenging even a single patent can run into the millions of dollars, and the BPCIA framework effectively forces a challenger to confront the entire thicket at once. This system creates powerful incentives for originators to pursue a strategy of “evergreening,” where they continuously file for new patents on minor modifications to extend their monopoly long after the foundational patent has expired.40 This contrasts sharply with the European Union, where stricter patentability standards, such as the “added matter” doctrine that prevents incremental claim expansion, make the construction of such dense thickets far more difficult.40 The patent thicket is therefore not merely a legal hurdle; it is a strategic weapon forged by the specific characteristics of the U.S. IP and regulatory system.

Strategic Sidesteps: “Skinny Labeling” and Litigation Settlements

Faced with the daunting prospect of fighting through a patent thicket, biosimilar developers have employed several strategic workarounds to mitigate risk and find a path to market. However, these strategies are often imperfect solutions to a deeply flawed system.

One such strategy is “skinny labeling.” This involves a biosimilar manufacturer seeking FDA approval for only a subset of the reference product’s approved indications, intentionally “carving out” any uses that are still protected by valid method-of-use patents.42 By launching with a label that does not include the patented indications, the biosimilar manufacturer can argue that it is not infringing those patents. This strategy has been used successfully for decades in the small-molecule generic world.42 However, its effectiveness is more limited for biosimilars. Because biosimilars are not automatically substituted at the pharmacy like generics, they must be actively marketed to physicians. This active promotion creates a risk that the originator will sue for “induced infringement,” arguing that the biosimilar company’s marketing activities are encouraging doctors to prescribe the product for the carved-out, patented uses.42

A far more common outcome in biosimilar patent litigation is a settlement. Faced with the astronomical cost and profound uncertainty of litigating dozens of patents to a final court decision, many biosimilar developers opt for a pragmatic business compromise. They agree to settle with the originator, accepting a licensed market entry date that is often several years after they might have launched “at risk” but years before the last patent in the thicket expires.39 These settlements provide business certainty, which is critical for planning a commercial launch, but they come at the cost of blunting the full and immediate impact of competition. This practice has also drawn increasing scrutiny from the FTC, which is concerned that some settlements may be anticompetitive “pay-for-delay” agreements in disguise, where the originator effectively pays the biosimilar challenger to stay off the market.3 These strategies—skinny labeling and settlements—are rational responses to an often irrational and hostile IP environment, but they represent compromises born of a system that makes a direct, head-on challenge prohibitively risky for all but the most well-funded and risk-tolerant companies.

Navigating the Landscape: The Critical Role of IP Intelligence

The sheer complexity of the patent gauntlet makes comprehensive, real-time intellectual property intelligence a non-negotiable, foundational element of any successful biosimilar development program. Before a single dollar is invested in clinical development, a biosimilar company must dedicate immense resources to conducting a meticulous “freedom-to-operate” (FTO) analysis.17 This involves systematically mapping the entire patent landscape for a target biologic, identifying every relevant patent and patent application, and meticulously analyzing each one to assess its validity and potential for infringement.4 The results of this analysis inform critical strategic decisions, such as whether to challenge certain patents in court, how to “design around” others by developing alternative formulations or manufacturing processes, or whether the IP risk is simply too high to proceed with the project at all. A flawed IP assessment can lead to a blocked launch, crippling financial damages, or the abandonment of a promising program after hundreds of millions of dollars have already been invested.17

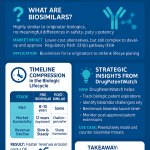

This is where specialized business intelligence services become indispensable. Platforms like DrugPatentWatch provide the critical data infrastructure required for these high-stakes strategic decisions. By aggregating and organizing comprehensive information on drug patents, patent expirations, ongoing litigation in both district courts and at the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB), and clinical trial activity, these services offer a centralized and up-to-date view of the competitive landscape.44 The ability to monitor biosimilar and 505(b)(2) activity, track patent challenges, and receive automated alerts on key events allows companies to proactively manage risk and refine their market-entry strategies.46 In the high-stakes world of biosimilars, IP data is not merely a legal concern; it is a core business asset. The capacity to accurately assess a patent thicket and anticipate an originator’s legal maneuvers can be the deciding factor between a successful launch and a catastrophic failure.

The Payer Wall: How Market Access Is Won and Lost

Surviving the regulatory and legal gauntlets is a monumental achievement for a biosimilar developer, but it only grants entry to the starting line of the commercial race. The ultimate success of a biosimilar is determined in the marketplace, a complex ecosystem where powerful commercial gatekeepers—namely Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs) and health insurers—wield immense influence. These entities, through their control over formularies and reimbursement, have erected a formidable “payer wall” that has proven to be the most significant and challenging barrier to biosimilar adoption in the United States.

The Power of the PBM: Gatekeepers of the US Drug Market

The U.S. prescription drug market is dominated by a small number of very large Pharmacy Benefit Managers. The top three PBMs—CVS Caremark (a subsidiary of CVS Health), Express Scripts (a subsidiary of Cigna), and Optum Rx (a subsidiary of UnitedHealth Group)—collectively control approximately 80% of all prescriptions dispensed in the country.47 PBMs act as intermediaries, managing prescription drug benefits on behalf of health insurance plans, large employers, and government programs. Their primary functions include creating and managing drug formularies (the list of covered drugs), negotiating rebates with pharmaceutical manufacturers, processing prescription claims, and operating mail-order and specialty pharmacies. This consolidated market power gives them enormous leverage to dictate which drugs are covered and how they are accessed by millions of Americans.

Deconstructing the “Rebate Wall”: How High-Rebate Originators Block Low-Cost Biosimilars

One of the most effective and controversial strategies used to block biosimilar competition is the “rebate wall,” also known as a “rebate trap”.49 This practice turns conventional price competition on its head. Here is how it works: an originator biologic manufacturer, whose product has a high list price, offers a PBM a substantial rebate in exchange for giving the originator’s drug exclusive or preferred status on the PBM’s formulary.49 This rebate is often tied to the PBM achieving certain market share targets for the originator’s product.

This arrangement creates a powerful financial disincentive for the PBM to cover a new, lower-list-price biosimilar. If the PBM adds the biosimilar to its formulary and patients begin to switch to it, the market share for the originator drug will fall. This could cause the PBM to miss its contractual market share target, jeopardizing the entire, lucrative stream of rebate dollars it receives from the high-volume originator.49 In many cases, the total value of the rebates from the high-priced originator is greater than the potential savings from adopting the lower-priced biosimilar, making it financially rational for the PBM to effectively block the competitor.

This system has perverse and harmful consequences for patients. A patient’s out-of-pocket cost-sharing, such as co-pays and co-insurance, is typically calculated based on the drug’s high list price, not the lower net price that the PBM and insurer pay after the secret rebate is factored in.23 As a result, a patient can be forced by their formulary to use the “preferred” originator biologic and end up paying a higher out-of-pocket cost than they would for a non-preferred biosimilar.

The rebate wall is a systemic, anti-competitive structure that is fundamentally biased against low-list-price products. It rewards the product that provides the largest financial return to the intermediary, not the product that offers the best value to the healthcare system or the lowest cost to the patient. This dynamic was the single most important factor behind the stunningly slow initial uptake of adalimumab (Humira) biosimilars, proving that even a dramatic price discount is not sufficient to overcome a misaligned incentive structure. The practice has become so problematic that it has drawn the intense scrutiny of federal regulators, including the FTC, which is investigating rebate walls as a potential unfair method of competition.30

The New Playbook: Vertical Integration and the Rise of Private-Label Biosimilars

Faced with the impenetrable rebate wall, the biosimilar market has recently undergone a seismic shift, with PBMs themselves entering the game. This has led to the rise of “private-label” or “white-label” biosimilars, a game-changing trend where a PBM partners with a biosimilar manufacturer to market the product under the PBM’s own brand.48

The adalimumab market provides the most dramatic case study of this new playbook. For over a year after launch, adalimumab biosimilars, some with list prices 85% lower than Humira, languished with a collective market share of just 2%.8 The originator’s rebate wall held firm. Then, in early 2024, the dynamic shifted abruptly. CVS Caremark announced it was removing the originator, Humira, from its major commercial formularies and would instead cover biosimilars, primarily a version of Sandoz’s Hyrimoz that was private-labeled for CVS’s own subsidiary, Cordavis.8 The other major PBMs quickly followed suit with their own private-label partnerships. This single strategic move by the PBMs accomplished what deep price discounts could not: it shattered the originator’s formulary blockade. Within months, the market share for adalimumab biosimilars surged from 2% to 22%.8

This development, while effective in breaking the originator’s monopoly, has solved one barrier only by creating another, potentially more formidable one. The rise of private-labeling suggests a new paradigm where market access is no longer primarily about negotiating with payers, but about securing an exclusive partnership with one of the three dominant, vertically integrated PBMs. This raises serious long-term concerns about the sustainability of a competitive biosimilar market. If only a select few PBM-partnered biosimilars can achieve commercial viability, it could crush non-partnered manufacturers, stifle price competition among different biosimilars, and ultimately lead to a new type of market oligopoly controlled by a handful of healthcare giants.48 This new PBM-controlled wall may prove even more difficult to scale for future biosimilar entrants.

The “Buy-and-Bill” Quagmire: Misaligned Incentives in Medicare Part B

The commercial barriers to biosimilar adoption are different, but no less significant, for drugs administered by physicians in a clinic or hospital setting, which are typically covered under the medical benefit (like Medicare Part B) rather than the pharmacy benefit. For these drugs, the primary reimbursement mechanism is the “buy-and-bill” model.2 Under this model, the physician or hospital purchases the drug, administers it to the patient, and then submits a claim to the insurer for reimbursement.

Under Medicare Part B, the reimbursement for these drugs is set at the drug’s Average Sales Price (ASP) plus a percentage-based add-on payment, which is typically 6% of the ASP.53 This formula creates a direct and perverse financial disincentive for providers to use lower-cost biosimilars. Because the add-on payment is a percentage of the price, the absolute dollar amount of the add-on is higher for a more expensive drug. For example, a 6% add-on for a $1,000 originator biologic yields a $60 payment to the provider, while a 6% add-on for a $700 biosimilar yields only a $42 payment.2 This system can put a provider’s financial interests in direct conflict with the healthcare system’s goal of using the most cost-effective therapy.

Policymakers have recognized this flaw. The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) of 2022 included a provision that temporarily attempts to re-align these incentives. For a five-year period, the add-on payment for qualifying biosimilars was increased to ASP plus 8% of the reference product’s ASP.53 This boosts the reimbursement for prescribing the biosimilar, making it a more financially attractive option for providers. The buy-and-bill model and the policy adjustments designed to fix it are a clear illustration of how seemingly technical details in reimbursement policy can directly shape clinical practice and either hinder or encourage the adoption of cost-saving biosimilars.

The Human Factor: Overcoming Physician and Patient Hesitancy

Beyond the formidable legal, regulatory, and commercial barriers, a final set of challenges resides in the hearts and minds of the ultimate end-users: the physicians who prescribe biosimilars and the patients who take them. These psychological, educational, and perceptual hurdles are often less tangible than a patent or a PBM contract, but they are no less critical to overcome for widespread biosimilar adoption. Trust, confidence, and clear communication are the currency of this domain.

Building Physician Confidence: From Clinical Data to Real-World Evidence

Despite years of safe and effective use in Europe and a growing track record in the U.S., a confidence gap persists among many American physicians. Surveys consistently show that physician confidence is one of the biggest barriers to biosimilar adoption, with one survey finding that 74% of physicians cite it as a top concern.54 Their apprehension often centers on several key areas:

- Safety and Efficacy: Lingering doubts about whether a “similar” product can truly deliver the same clinical outcomes as the originator it was modeled after.55

- Immunogenicity: Concerns that minor differences in the biosimilar molecule could provoke an unwanted immune response in patients.10

- Extrapolated Indications: Skepticism about using a biosimilar for an indication that was approved based on data “extrapolated” from studies in a different patient population, even though this is a scientifically validated and accepted regulatory practice.55

- Switching: A particular reluctance to switch a patient who is stable and doing well on an originator biologic to a biosimilar, for fear of disrupting their clinical stability.10

The FDA’s declaration of “no clinically meaningful differences” is a necessary starting point, but for many clinicians, it is not sufficient on its own to earn their complete trust. The very nature of biosimilars being “similar” rather than “identical” creates a higher perceived burden of proof in the clinical community. To bridge this confidence gap, physicians have made their needs clear. In surveys, 68% state that robust provider education on product efficacy and safety is a “must-have,” and 50% demand real-world evidence of successful switching between the originator and the biosimilar.54

This demonstrates that trust in biosimilars must be earned over time, not simply assumed upon regulatory approval. It requires a multi-pronged effort. Manufacturers must be transparent with their clinical trial data. The medical community must continue to generate and publish post-marketing, real-world evidence, such as the landmark NOR-SWITCH study, which provided critical data supporting the safety of switching patients from an originator to a biosimilar.58 And this body of evidence must be actively disseminated through educational initiatives led by trusted medical societies and key opinion leaders to institutionalize confidence in clinical practice.

Addressing the “Nocebo Effect” and Patient Concerns About Switching

Patients often share the same apprehensions as their physicians, but their concerns are amplified by a powerful psychological phenomenon known as the “nocebo effect.” The nocebo effect is the inverse of the more familiar placebo effect; it occurs when a patient’s negative expectations about a treatment lead to the perception of negative side effects or reduced efficacy, even if the treatment itself is effective.47 If a patient is told they are being switched to a “cheaper copy” of their medication, they may be primed to attribute any subsequent adverse feeling or symptom to the new drug, eroding their confidence and potentially impacting the treatment’s real-world effectiveness.

Survey data reveals the depth of this patient apprehension. A large majority of patients—85% in one survey—expressed concern that a biosimilar would not treat their disease as well as their current biologic, and 83% were worried that switching might cause more adverse effects.57 Consequently, most patients (85%) indicated they would not want to switch if their current therapy is working well.57 This highlights that non-medical switching—a switch made for cost or formulary reasons rather than clinical ones—is a major source of anxiety for patients who have often struggled for years to find a treatment that stabilizes their chronic condition.

The nocebo effect is a potent barrier that cannot be overcome by clinical data or policy mandates alone. It underscores the absolute importance of the patient-physician relationship and the power of communication. The way a switch to a biosimilar is framed can dramatically influence the patient’s experience and the ultimate clinical outcome. A conversation that frames the switch as a forced, cost-cutting measure by an anonymous insurer is likely to trigger a negative response. In contrast, a conversation that frames it as a positive and safe step toward using a therapy that is just as effective while contributing to a more sustainable and accessible healthcare system can foster patient buy-in and confidence. This reality highlights the urgent need for educational tools and resources that empower both patients and providers to engage in these sensitive but crucial conversations constructively.

The Critical Role of Education and Advocacy

Overcoming the human-factor barriers to biosimilar adoption is not the sole responsibility of any single stakeholder; it requires a concerted and collaborative effort to build a supportive, pro-biosimilar ecosystem. This involves a multi-pronged educational campaign targeting every key group in the healthcare landscape: physicians, pharmacists, payers, policymakers, and, of course, patients.60

Health systems can play a pivotal role in driving this change from within. A compelling case study comes from the Yale New Haven Health System (YNHHS). Faced with the need to manage the introduction of biosimilars, YNHHS implemented a comprehensive, four-pronged educational program led by its Oncology Chief Medical Officer. The program involved targeted presentations to the oncology subcommittee and the system-wide Pharmacy & Therapeutics (P&T) Committee, educational sessions during Oncology Grand Rounds, and numerous one-on-one discussions with key stakeholders.62 This extensive educational effort was highly successful, leading YNHHS to formally designate approved biosimilars as therapeutically equivalent to their reference products. This policy change allows formulary decisions to be based on financial and operational factors, facilitating earlier contract discussions with manufacturers and streamlining biosimilar integration.62 The key lesson: extensive, targeted education is the facilitator of institutional adoption.

Beyond the walls of individual health systems, advocacy organizations are crucial force multipliers. Groups like the Biosimilars Council, a division of the Association for Accessible Medicines, focus on educating policymakers and healthcare professionals, providing resources like the comprehensive Biosimilars Handbook and a toolkit of fact sheets and infographics.60 At the same time, patient-focused advocacy groups like AiArthritis and coalitions like the Alliance for Safe Biologic Medicines (ASBM) play the vital role of translating complex scientific and regulatory information into accessible materials for patients.16 They develop patient guides, host educational webinars with clinical experts, and advocate for patient-centric policies, ensuring that the patient voice is a central part of the conversation around access and switching. The success of biosimilars ultimately depends on this collaborative network—with manufacturers providing the data, medical societies validating it, health systems institutionalizing it, and advocacy groups disseminating it—to build a foundation of trust and understanding across the entire healthcare community.

Market Reality Part I: The First Wave – Lessons from Zarxio’s Launch

To fully appreciate the evolution of the U.S. biosimilar market, it is essential to examine its beginnings. The launch of the very first FDA-approved biosimilar, Zarxio (filgrastim-sndz), served as a critical test case, revealing the initial dynamics of a nascent market and foreshadowing the more complex challenges that lay ahead.

Zarxio, a biosimilar to Amgen’s Neupogen (filgrastim), was approved by the FDA in March 2015 and launched in the U.S. in September of that year.9 Filgrastim is a granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF), a supportive care biologic used to stimulate the production of white blood cells in cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy to reduce the risk of infection.64 As the pioneer, Zarxio’s manufacturer, Sandoz, faced the monumental task of not only launching a new product but also educating an entire market about the novel concept of a biosimilar.

The launch strategy and subsequent market performance offered several key lessons:

- Conservative Pricing: Contrary to some analyst expectations of deep discounts, Sandoz launched Zarxio with a relatively modest wholesale acquisition cost (WAC) that was 15% lower than Neupogen’s.9 This suggested that first-to-market biosimilars might opt for a more conservative pricing strategy to recoup development costs, rather than engaging in an immediate price war.

- Slow but Steady Uptake: Market adoption was not immediate but was slow and steady. Zarxio gradually eroded the market share of the originator, Neupogen, as healthcare providers became more comfortable with the product. By the end of 2016, roughly 15 months after launch, Zarxio had captured a respectable 15% of the short-acting G-CSF market.9

- The Importance of Promotion: Recognizing the need to overcome physician skepticism, Sandoz invested significantly in marketing and education. The company’s promotional spend in 2016 was split between traditional journal advertising and electronic promotions (46%) and detailing by sales representatives who engaged directly with healthcare providers (54%).9 This underscored the reality that, unlike generics, biosimilars required active promotion to build brand recognition and clinical confidence.

- The Influence of Incentives: Zarxio’s launch provided the first real-world glimpse into how the unique incentive structures of the U.S. healthcare system would impact biosimilar use. In the oncology space, where filgrastim is primarily used, the “buy-and-bill” reimbursement model was prevalent. As discussed previously, this model provided little to no financial incentive for physicians to prescribe the lower-cost biosimilar over the higher-cost originator, which undoubtedly acted as a brake on more rapid adoption.9

- The Power of Payers: From the outset, it was clear that gaining favorable formulary status with payers and integrated delivery networks (IDNs) was a critical driver of access and uptake. Early wins, such as Cigna moving Zarxio from “Not Covered” to a preferred tier, were essential for market penetration.9

Zarxio’s launch was a proving ground for the U.S. biosimilar market. It was a qualified success that set the stage for future entrants, demonstrating that FDA approval was merely the first step on a long road to commercial viability. The experience highlighted that market success required a significant and sustained investment in education to overcome physician inertia and a sophisticated strategy to navigate the complex web of payer and provider incentives. It was a crucial first chapter that provided a valuable, if sometimes difficult, education for the entire industry.

Market Reality Part II: The Tsunami – Unpacking the Adalimumab (Humira) Market

If the launch of Zarxio was the first ripple in the U.S. biosimilar pond, the 2023 arrival of competitors to AbbVie’s Humira (adalimumab) was a tsunami. The battle for the adalimumab market has been the most complex, competitive, and revealing episode in the history of U.S. biosimilars, fundamentally reshaping the industry’s understanding of the barriers to success.

The launch of adalimumab biosimilars was unprecedented in several key respects, making it a unique and powerful case study:

- Unprecedented Market Size: Humira was not just a blockbuster; it was a mega-blockbuster. In 2022, the year before its first U.S. biosimilar competitor launched, Humira generated $21 billion in net revenue for AbbVie.67 The sheer scale of the prize attracted nearly every major biosimilar manufacturer.

- Unmatched Level of Competition: The market was flooded with competitors in a remarkably short period. Within six months of the first launch in January 2023, there were eight different adalimumab biosimilars available in the U.S., with more on the way.67 This level of head-to-head competition was previously unseen in any biosimilar category.

- A New Playing Field: Crucially, adalimumab was the first major biologic of its size to be managed primarily under the pharmacy benefit rather than the medical benefit.67 This meant that PBMs, not physicians’ offices, were the primary purchasers and gatekeepers, bringing their unique and often opaque business practices to the forefront of the battle.

The Great Stall: Why Deep Discounts Weren’t Enough

Armed with the knowledge that price competition was key, biosimilar manufacturers entered the adalimumab market with aggressive pricing strategies. Several companies, including the makers of Hadlima, Yusimry, and Simlandi, launched with wholesale acquisition costs (WACs) that were a staggering 85% to 86% lower than Humira’s list price.8 Other manufacturers offered dual-pricing models, with both a high-WAC, high-rebate version and a low-WAC, low-rebate version to appeal to different payer preferences.8 The market was awash with lower-cost options, including several that had secured the coveted “interchangeable” designation from the FDA.33

Yet, for the entirety of 2023, the market barely moved. Despite the flood of low-cost alternatives, biosimilar uptake was shockingly anemic, with all competitors combined capturing a mere 2% of the total adalimumab market by the end of the year.33 The interchangeable designation, once thought to be a key differentiator, proved to be a non-factor in driving initial adoption.33

The culprit behind this great stall was the PBM rebate wall, operating at maximum efficiency. The major PBMs, locked into lucrative rebate contracts with AbbVie, largely kept the high-priced originator, Humira, as the preferred agent on their formularies. This effectively blocked patient access to the new, low-list-price biosimilars, regardless of their price or interchangeability status.8 The experience was a stark and costly lesson for the industry: in a PBM-controlled market, a lower price is meaningless if the product cannot get past the formulary gatekeeper.

The Turning Point: The PBM Private-Label Strategy

In early 2024, the market dynamic shifted dramatically. The PBMs, having demonstrated their power to stall the market, executed a new strategy to capture a larger share of the value for themselves. In a watershed moment, CVS Caremark announced it was removing Humira from its major commercial formularies. In its place, it would exclusively cover certain biosimilars—most notably, a private-label version of Sandoz’s Hyrimoz, branded for CVS’s own drug sourcing subsidiary, Cordavis.8 The other major PBMs soon followed with similar private-label arrangements.

The impact was immediate and profound. The PBMs’ move single-handedly shattered AbbVie’s rebate wall and forced a massive shift in prescribing. The collective market share for adalimumab biosimilars surged from 2% to 22% in a matter of months, with the vast majority of that share flowing to the PBMs’ chosen private-label partners.8

The adalimumab saga represents a watershed moment for the U.S. biosimilar market. It is a real-world, high-stakes demonstration of the true hierarchy of market access barriers. It proved conclusively that for drugs on the pharmacy benefit, PBM formulary control is the ultimate barrier, one that trumps price, interchangeability, and the number of competitors. The failure of the initial, price-driven launch strategy and the subsequent success driven by PBM self-interest has fundamentally rewritten the strategic playbook for all future pharmacy-benefit biosimilars. It sends a clear and chilling signal to manufacturers: market access is no longer just about offering a good price and negotiating with payers; it may now be about securing an exclusive partnership with a PBM, a much higher and more difficult bar to clear.

Table 3: The US Adalimumab (Humira) Biosimilar Landscape (as of mid-2024)

| Biosimilar Name (Brand) | Manufacturer | Approval Date | Launch Date | Interchangeability Status | Key Pricing Strategy |

| Amjevita (adalimumab-atto) | Amgen | Sep 2016 | Jan 2023 | No | Dual Pricing (High/Low WAC) 70 |

| Cyltezo (adalimumab-adbm) | Boehringer Ingelheim | Aug 2017 | Jul 2023 | Yes (Interchangeable) 68 | Dual Pricing (High/Low WAC) |

| Hyrimoz (adalimumab-adaz) | Sandoz | Oct 2018 | Jul 2023 | No | Dual Pricing; PBM Private Label 8 |

| Hadlima (adalimumab-bwwd) | Organon/Samsung Bioepis | Jul 2019 | Jul 2023 | No | Low WAC (~86% discount) 8 |

| Abrilada (adalimumab-afzb) | Pfizer | Nov 2019 | Nov 2023 | Yes (Interchangeable) 68 | Dual Pricing (High/Low WAC) |

| Hulio (adalimumab-fkjp) | Biocon/Viatris | Jul 2020 | Jul 2023 | No | Dual Pricing (High/Low WAC) 68 |

| Yusimry (adalimumab-aqvh) | Coherus BioSciences | Dec 2021 | Jul 2023 | No | Low WAC (~85% discount) 8 |

| Idacio (adalimumab-aacf) | Fresenius Kabi | Dec 2022 | Jul 2023 | No | Dual Pricing (High/Low WAC) 68 |

| Yuflyma (adalimumab-aaty) | Celltrion | May 2023 | Jul 2023 | No | High Concentration Formulation 68 |

| Simlandi (adalimumab-ryvk) | Alvotech/Teva | Feb 2024 | Mar 2024 | Yes (Interchangeable) 68 | Low WAC (~85% discount) |

The Economic Impact: Quantifying Savings and Patient Costs

The ultimate rationale for a biosimilar market is economic: to reduce the immense financial burden of biologic medicines on the healthcare system and on patients. An analysis of the economic impact reveals a tale of two outcomes. At a macro level, biosimilars are successfully generating billions of dollars in system-wide savings. However, due to the complexities of U.S. drug pricing and reimbursement, these savings do not always trickle down to the individual patients who use the medications, creating a frustrating and politically charged paradox.

Billions in System-Wide Savings: The Macro View

From a high-level perspective, the biosimilar market is working as intended to lower costs. The introduction of competition has had a demonstrable effect on drug spending. According to the Association for Accessible Medicines, biosimilars have saved the U.S. healthcare system a total of $36 billion since their introduction in 2015, with savings accelerating in recent years to reach $12.4 billion in 2023 alone.5

This impact is achieved through two primary mechanisms. First, biosimilars enter the market at a significantly lower price. On average, the sales price of a biosimilar is about 50% less than the reference biologic’s price was at the time of the biosimilar launch.6 Second, the mere presence of a biosimilar competitor forces the originator manufacturer to lower its own price to maintain market share. Data shows that competition from biosimilars has reduced the average sales price of their corresponding reference biologics by an average of 25%.6 This competitive pressure benefits the entire system, as both the originator and the biosimilar become more affordable. Looking forward, the potential for savings remains vast. One analysis by RAND Corporation projected that biosimilars would reduce direct spending on biologic drugs by $54 billion over the ten-year period from 2017 to 2026.28

The Patient Paradox: Why System Savings Don’t Always Trickle Down

While the macro-level savings are significant and growing, there is a critical and frustrating disconnect when it comes to patient-level costs. The billions of dollars in savings generated for the healthcare system do not consistently translate into lower out-of-pocket (OOP) expenses for the patients who rely on these therapies.23

The root of this paradox lies in the opaque and convoluted system of drug pricing and rebates, particularly for drugs covered under the pharmacy benefit. As previously discussed, PBMs often negotiate large, secret rebates from originator manufacturers in exchange for preferred formulary placement. A patient’s cost-sharing obligation—their co-pay or co-insurance—is frequently calculated based on the drug’s high, pre-rebate list price, not the much lower net price that their insurer actually pays.50

This creates a perverse situation where a patient can be on their health plan’s “preferred” originator biologic and be forced to pay a high co-pay based on a list price of thousands of dollars, even while a biosimilar with a list price 85% lower is available but not covered by their plan. The average co-pay for a brand-name drug in the U.S. is $56.12, which is nearly nine times higher than the average co-pay for a generic drug ($6.16).6 This disconnect between system-level savings and patient-level costs is not just a market inefficiency; it is a source of profound patient frustration and a major political liability for the pharmaceutical industry and its intermediaries. It fuels public anger over high drug prices and drives calls for more aggressive government regulation. This structure, which allows intermediaries to capture the vast majority of savings rather than passing them on to the end-users, fundamentally undermines the social contract of a market-based healthcare system.

Impact on Medicare: A Brighter Spot

The economic picture is considerably clearer and more positive for physician-administered biologics covered under Medicare Part B. In this segment of the market, the reimbursement structure is more transparent, and savings from biosimilar competition flow more directly to the Medicare program and its beneficiaries.

An analysis by the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) found that for eight major biologics with biosimilar competition, the Medicare Part B program and its beneficiaries saw substantial savings.53 Between 2018 and 2023, biosimilar competition reduced Medicare Part B spending by an estimated $12.9 billion. During the same period, beneficiary out-of-pocket costs were reduced by $3.2 billion.53 The impact has been accelerating; in 2023 alone, biosimilars reduced program spending by $4.4 billion and beneficiary OOP costs by $1.1 billion.53 For a Medicare beneficiary using one of these biologics in 2023, the availability of biosimilars resulted in an average annual savings of nearly $2,000 in potential out-of-pocket costs.53

The stark contrast between the direct, tangible savings seen in the Medicare Part B medical benefit and the murky, disconnected savings on the pharmacy benefit highlights a crucial point: reimbursement structure is destiny. The Part B model, while flawed in its own ways (e.g., the buy-and-bill incentive structure), is based on a more transparent pricing metric (the Average Sales Price), and the economic benefits of lower-priced alternatives are more readily passed on to the program and the patient. This tale of two benefits strongly suggests that policies promoting greater price transparency and directly linking patient cost-sharing to the net, post-rebate price of drugs could unlock significant and much-needed savings for patients on the pharmacy side of the equation.

The Future of US Biosimilars: Policy, Patents, and Pipelines

The U.S. biosimilar market is at a critical inflection point. The first decade has been a learning experience, defined by a slow start and the emergence of formidable barriers. The next decade will be defined by how stakeholders—manufacturers, payers, and policymakers—respond to these lessons. The future landscape will be shaped by the next wave of blockbuster patent expiries, a growing push for legislative and regulatory reform, and a more aggressive stance from federal antitrust enforcers.

On the Horizon: Keytruda, Dupixent, and the Next Wave of Blockbuster Patent Expiries

The next front in the biosimilar wars is already taking shape. The industry is closely watching the pipelines for biosimilar versions of some of the world’s top-selling biologics, whose patent protections are set to expire in the coming years. Among the most significant are:

- Pembrolizumab (Keytruda): This foundational cancer immunotherapy from Merck, with annual sales approaching $30 billion, is expected to face biosimilar competition starting in 2028. At least seven developers, including major players like Samsung Bioepis, Sandoz, and Amgen, are already in the race, with some candidates in late-stage clinical trials.7

- Dupilumab (Dupixent) and Risankizumab (Skyrizi): These immunology blockbusters from Sanofi/Regeneron and AbbVie, respectively, are high-priority targets for biosimilar development, with patent expiries expected in the early 2030s.7

- Other Key Targets: Biosimilars are also in development for other major biologics like Stelara (ustekinumab), Prolia/Xgeva (denosumab), Entyvio (vedolizumab), and Opdivo (nivolumab), representing billions of dollars in potential market disruption.31

The strategic lessons learned from the adalimumab launch will cast a long shadow over these future battles. Originator companies will undoubtedly continue to employ sophisticated strategies, including building dense patent thickets and leveraging rebate walls, to defend their market share. In turn, biosimilar manufacturers will need to plan their commercial strategies with the PBM private-label playbook in mind, recognizing that a partnership with a major payer may be a prerequisite for success. The fight for Keytruda’s market share will serve as a crucial litmus test, revealing whether the barriers identified in this report have been mitigated by policy changes or have become even more entrenched.

Legislative Levers: Can Policy Clear the Path?

There is a growing consensus in Washington, D.C., that the U.S. biosimilar market, left to its own devices, has failed to produce a sufficiently competitive environment. This has led to a wave of bipartisan legislative proposals aimed at systematically dismantling the specific barriers that have been perfected by incumbent manufacturers and intermediaries. Key proposals include:

- The Biosimilar Red Tape Elimination Act: Reintroduced in June 2025 by Senator Mike Lee, this bill targets the regulatory and perception barrier of interchangeability. It proposes to amend the BPCIA to deem all FDA-approved biosimilars as interchangeable upon approval, eliminating the need for separate designations and potentially costly switching studies.30

- Patent Thicket Legislation (e.g., the ETHIC Act): Several bills have been proposed to directly attack the patent thicket barrier. These proposals generally seek to cap the number of patents an originator can assert against a biosimilar challenger in litigation, forcing them to focus on their strongest and most innovative patents rather than overwhelming competitors with sheer volume.3

- The Skinny Labels, Big Savings Act: This legislation aims to strengthen the “skinny label” strategy by providing a clear statutory safe harbor for biosimilar and generic manufacturers who carve out patented indications from their labels. This would protect them from induced infringement lawsuits and make it a more viable and less risky patent avoidance strategy.3

The proliferation of these targeted bills indicates a significant policy shift. It reflects a recognition that the market’s failures are not accidental but are the result of specific, exploitable loopholes in the current legal and regulatory framework. The trend is clearly moving away from a belief in pure market forces and toward a strategy of targeted policy intervention designed to rebalance the competitive scales.

The Watchdog’s Role: How the FTC is Tackling Anticompetitive Practices

Alongside legislative efforts, federal antitrust enforcers are taking a more aggressive posture. The Federal Trade Commission (FTC), in collaboration with the Department of Justice (DOJ) and the FDA, has made promoting competition in pharmaceutical markets a top priority.43

“Competition between reference biologics and biosimilars is just as important as competition between brand and generic small molecule drugs. Biosimilars, which are as safe and effective as their reference biologics, hold the promise of reducing price, and therefore increasing access to these treatments.”

— Tara Koslov, FTC Chief of Staff, at the FDA/FTC Workshop on a Competitive Marketplace for Biosimilars 75

The FTC’s focus has expanded beyond traditional “pay-for-delay” patent settlements to scrutinize a wider range of anticompetitive behaviors. The agency’s enforcement targets now include the use of patent thickets, “product hopping” (where an originator makes minor changes to a product to thwart substitution), and, most significantly, the exclusionary contracting practices of PBMs.30 The FTC has publicly supported the FDA’s move to eliminate switching studies for interchangeability, calling it a pro-competitive step that will reduce barriers to entry.32 Furthermore, the agency has taken direct action, filing lawsuits against the largest PBMs challenging their rebate practices as a violation of antitrust law.30

This represents a major pivot in antitrust enforcement. For years, the primary focus was on the interactions between originator and follow-on manufacturers. The FTC’s recent actions and public statements make it clear that the agency now views PBMs and their opaque rebate and formulary practices as a primary source of anticompetitive harm in the drug supply chain. This heightened regulatory pressure on PBMs, combined with the ongoing legislative push for reform, may be the most powerful force for change in the U.S. biosimilar market over the next five years.

Table 4: Key Legislative and Regulatory Proposals to Address Biosimilar Barriers

| Proposal/Action | Key Provision | Primary Barrier Addressed |

| Biosimilar Red Tape Elimination Act | Deems all approved biosimilars as interchangeable by default. 30 | Regulatory & Perceptual (eliminates two-tiered system). |

| Patent Thicket Legislation (ETHIC Act) | Limits the number of patents an originator can assert in litigation. 3 | Legal (dismantles patent thickets as a delay tactic). |

| Skinny Labels, Big Savings Act | Provides a statutory safe harbor for carving out patented indications. 3 | Legal (strengthens a key patent avoidance strategy). |

| FDA Interchangeability Guidance Update | Eliminates the general requirement for switching studies for interchangeability. 31 | Regulatory (lowers cost and time to achieve designation). |

| FTC PBM Enforcement Actions | Lawsuits and investigations into PBM rebate and formulary practices. 30 | Commercial (targets rebate walls and anti-competitive contracting). |

Conclusion: Charting a Course for a Sustainable Biosimilar Future

The journey of a biosimilar in the United States is an arduous one. The path from development to patient is a multi-stage gauntlet where a manufacturer must first survive a scientifically rigorous and financially draining regulatory approval process, then navigate a legal minefield of patents deliberately constructed to delay and deter, then scale a commercial wall erected by powerful intermediaries with misaligned financial incentives, and finally, win the trust and confidence of the physicians and patients who are the ultimate arbiters of its success. These barriers are not isolated; they are deeply interconnected, creating a system that has, for more than a decade, protected incumbent biologics and blunted the full competitive force of lower-cost alternatives.

The battlefield, however, is dynamic. The nature of these barriers is constantly evolving. The regulatory hurdle of interchangeability, once a major point of contention, appears to be shrinking as the FDA modernizes its requirements. In its place, the commercial barrier of PBM control has grown more powerful and explicit, evolving from opaque rebate walls to the more direct strategy of private-label partnerships. This demonstrates that as one barrier is lowered, the market adapts, and new challenges emerge.

Charting a course for a sustainable and truly competitive biosimilar future requires a clear-eyed understanding of this landscape and a concerted effort from all stakeholders. For biosimilar manufacturers, success demands not only scientific excellence and deep financial pockets but also sophisticated IP and legal strategies and a willingness to engage in novel, and sometimes risky, commercial partnerships. For payers and PBMs, the industry is at a crossroads. They face a choice between continuing to maximize short-term revenue through rebate-driven formularies and embracing a long-term vision of system sustainability, all while facing intensifying pressure from regulators, employers, and the public to increase transparency and pass savings on to consumers. And for policymakers and regulators, the path forward requires continued, targeted action to dismantle the artificial barriers that distort competition. This includes reforming the patent system to discourage the abuse of thickets, ensuring that reimbursement models align provider incentives with system-wide value, and holding all actors in the supply chain accountable for practices that prioritize profits over patient access and affordability.

The promise of biosimilars—a more affordable and accessible future for biologic medicine—remains as compelling today as it was when the BPCIA was signed into law. Realizing that promise in the United States will require a sustained commitment to clearing the path, ensuring that the forces of competition can finally work for the benefit of the healthcare system and, most importantly, for the millions of patients it serves.

Key Takeaways

- The US Biosimilar Market is Uniquely Challenging: Despite significant potential for cost savings ($36 billion since 2015), the U.S. market has seen slower biosimilar adoption compared to Europe due to a complex web of interconnected barriers.

- Regulatory and Legal Hurdles are Formidable: The FDA’s rigorous “totality of the evidence” approval standard is costly ($100M-$250M per product), and the U.S. patent system allows originators to build dense “patent thickets” that delay competition for years, a problem exemplified by the Humira case.

- PBMs are the Ultimate Gatekeepers: For drugs on the pharmacy benefit, PBMs have become the most significant barrier. “Rebate walls” from high-priced originators block low-cost biosimilars. The recent shift to PBM-owned “private-label” biosimilars has broken originator monopolies but created a new, potentially more powerful PBM-controlled barrier to entry.

- Incentives are Often Misaligned: In the “buy-and-bill” medical benefit market (Medicare Part B), reimbursement formulas have historically provided a financial disincentive for physicians to use lower-cost biosimilars. Similarly, the PBM rebate system incentivizes payers to prefer high-list-price drugs, often at the patient’s expense.

- Physician and Patient Confidence is Crucial but Lags: Overcoming hesitancy requires more than just FDA approval. Physicians demand robust education and real-world evidence of safety and efficacy, while patients are concerned about non-medical switching and the “nocebo effect.” Building trust is a critical, ongoing effort.

- The Landscape is Shifting Due to Policy and Enforcement: There is a growing trend toward policy intervention to fix the market’s failures. Legislative proposals are targeting patent thickets and interchangeability rules, while the FTC is aggressively investigating PBMs and other anticompetitive practices, signaling a potential rebalancing of the competitive landscape.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. Why are biosimilars so much harder to bring to market in the U.S. than generic drugs?

Biosimilars are fundamentally different from generics. They are large, complex molecules grown in living cells, making them “highly similar” but not identical to their reference products. This requires a much more extensive and costly FDA approval process ($100-$250 million) to prove safety and efficacy, compared to the simple bioequivalence studies for identical, small-molecule generics ($1-$4 million). Furthermore, biologics are often protected by dense “patent thickets” that are far more difficult and expensive to challenge in court than the patents on typical small-molecule drugs.

2. What is a “rebate wall” and how does it block biosimilars?

A “rebate wall” is a commercial barrier where an originator biologic manufacturer offers a large rebate to a Pharmacy Benefit Manager (PBM) in exchange for exclusive or preferred placement on its drug formulary. This makes it financially unattractive for the PBM to cover a new, lower-cost biosimilar, because doing so could cause them to lose the lucrative rebate stream from the high-volume originator drug. This system can effectively block patient access to more affordable options, even when they are available.

3. I thought interchangeability was the key to biosimilar success. Why did it not seem to matter for the Humira biosimilars?

While the “interchangeable” designation allows for pharmacy-level substitution, the Humira launch demonstrated that for drugs managed by PBMs, formulary control is a more powerful force. Initially, neither interchangeable nor non-interchangeable Humira biosimilars gained significant market share because PBMs kept the originator, Humira, as the preferred drug. The market only shifted when PBMs decided to remove Humira from their formularies and replace it with their own private-label biosimilars. This showed that a PBM’s ability to dictate coverage is the primary driver of uptake, regardless of a product’s interchangeability status.

4. Will biosimilars actually lower my personal out-of-pocket costs?

It depends. For physician-administered drugs under Medicare Part B, biosimilars have been shown to directly lower beneficiary out-of-pocket costs. However, for drugs from a retail pharmacy (covered by the pharmacy benefit), the savings are less direct. Your co-pay is often based on the drug’s high list price, not the lower net price your insurer pays after rebates. Therefore, even if the system is saving money, you may not see a reduction in your co-pay unless your health plan is specifically designed to pass those savings on to you, for example by covering a low-list-price biosimilar in a preferred tier.

5. What is the single biggest change that could improve the U.S. biosimilar market?

While there is no single silver bullet, many experts point to reforming the PBM and rebate system as the most impactful change. Addressing the misaligned incentives that allow PBMs to profit more from high-list-price, high-rebate drugs than from low-list-price biosimilars would fundamentally alter the commercial landscape. Increased transparency and policies that link patient cost-sharing to net prices, combined with stronger antitrust enforcement against exclusionary contracting, would likely do more than any other single action to foster a truly competitive and sustainable biosimilar market.

References

- Commemorating the 15th Anniversary of the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/cder-conversations/commemorating-15th-anniversary-biologics-price-competition-and-innovation-act

- The Biosimilar Reimbursement Revolution: Navigating Disruption and Seizing Competitive Advantage – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-impact-of-biosimilars-on-biologic-drug-reimbursement-models/

- Patent Thickets and Litigation Abuses Hinder all Biosimilars …, accessed August 5, 2025, https://accessiblemeds.org/resources/press-releases/patent-thickets-and-litigation-abuses-hinder-all-biosimilars/

- Clearing the Thicket: New Report Outlines Legislative Fixes to Boost Biosimilar Access, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.centerforbiosimilars.com/view/clearing-the-thicket-new-report-outlines-legislative-fixes-to-boost-biosimilar-access

- 2024 U.S. Generic & Biosimilar Medicines Savings Report, accessed August 5, 2025, https://accessiblemeds.org/resources/reports/2024-savings-report/

- Report: 2023 U.S. Generic and Biosimilar Medicines Savings Report …, accessed August 5, 2025, https://accessiblemeds.org/resources/reports/2023-savings-report-2/

- The Future of Top-Selling Biologics: Biosimilars on the Rise, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.pharmacytimes.com/view/the-future-of-top-selling-biologics-biosimilars-on-the-rise

- Samsung Bioepis Report Showcases Adalimumab Biosimilar …, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.centerforbiosimilars.com/view/samsung-bioepis-report-showcases-adalimumab-biosimilar-growth-in-market-share

- Major lessons learned from Zarxio’s US launch: the start of a …, accessed August 5, 2025, https://gabi-journal.net/major-lessons-learned-from-zarxios-us-launch-the-start-of-a-biosimilar-revolution.html

- Physicians’ perceptions of the uptake of biosimilars: a systematic review | BMJ Open, accessed August 5, 2025, https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/10/5/e034183

- An unofficial legislative history of the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act of 2009 – PubMed, accessed August 5, 2025, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24479247/

- Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.dpc.senate.gov/healthreformbill/healthbill70.pdf

- Difference between generic drugs and biosimilar drugs | Gouvernement du Québec, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.quebec.ca/en/health/medications/biosimilar-drugs/difference-between-generic-drugs-and-biosimilar-drugs

- Generic and Biosimilar Medications – National MS Society, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.nationalmssociety.org/managing-ms/treating-ms/disease-modifying-therapies/generic-biosimilars

- Foundational Concepts Generics and Biosimilars – FDA, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/media/154912/download

- Biosimilars Education and Advocacy AiArthritis, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.aiarthritis.org/biosimilars

- Cracking the Biosimilar Code: A Deep Dive into Effective IP Strategies – Drug Patent Watch, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/cracking-the-biosimilar-code-a-deep-dive-into-effective-ip-strategies/

- Biosimilar Product Regulatory Review and Approval | FDA, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/files/drugs/published/Biosimilar-Product-Regulatory-Review-and-Approval.pdf

- Biosimilar Approval Process | Sandoz US, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.sandoz.com/us-en/biosimilars/biosimilar-approval-process/

- Biosimilar Regulatory Review and Approval – FDA, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/media/151061/download

- Prescriber Perspectives on Biosimilar Adoption and Potential Role of Clinical Pharmacology: A Workshop Summary – PMC, accessed August 5, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10099086/

- The Economics of Biosimilars – PMC, accessed August 5, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4031732/

- The Paradox of Progress: Does Biosimilar Competition Truly Reduce Patient Out-of-Pocket Costs for Biologic Drugs? – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/biosimilar-competition-does-not-reduce-patient-out-of-pocket-costs-for-biologic-drugs/

- Innovative Formulation Strategies for Biosimilars: Trends Focused on Buffer-Free Systems, Safety, Regulatory Alignment, and Intellectual Property Challenges – PMC – PubMed Central, accessed August 5, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12196224/

- Interchangeable Biological Products – FDA, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/media/151094/download

- Biosimilar Interchangeability FAQs – Biosimilars Council, accessed August 5, 2025, https://biosimilarscouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/2023-Biosimilar-Interchangeability-FAQs.pdf