Introduction: The $200 Billion Ticking Clock

In the pharmaceutical industry, time is the ultimate currency, and the clock is always ticking. For executives, investors, and strategists, one date on the calendar looms larger than any other: the Loss of Exclusivity (LOE). This is the moment a blockbuster drug, the financial engine of a multi-billion dollar enterprise, loses its patent protection and faces the onrushing tide of generic competition.

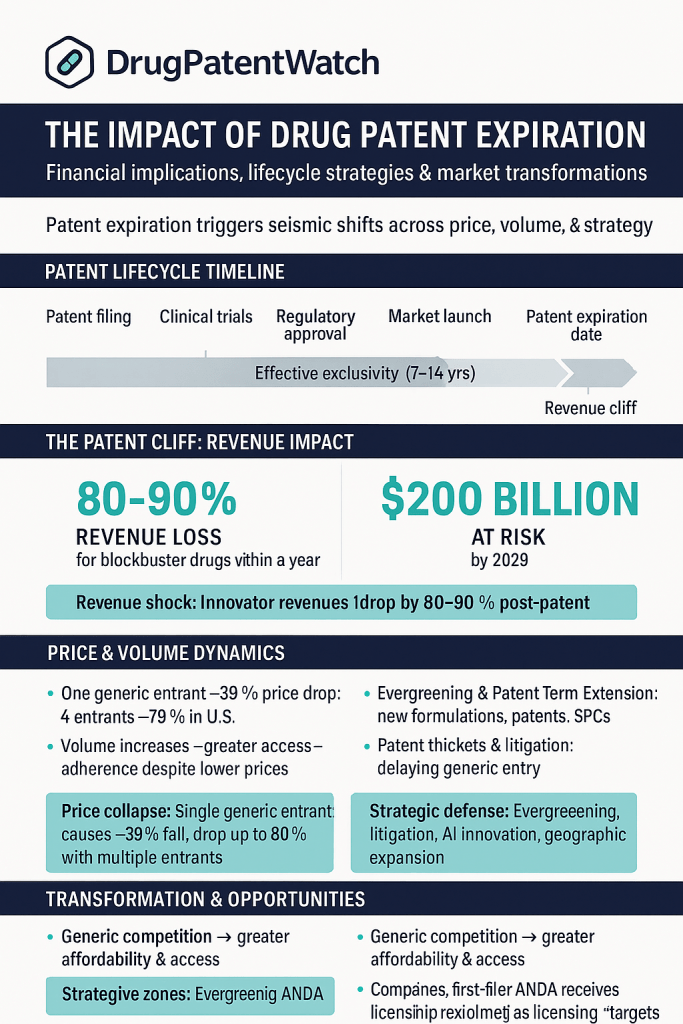

This phenomenon, famously known as the “patent cliff,” is not a distant academic concept. It is an immediate, quantified, and recurring financial reality. The numbers are staggering. Between 2025 and 2030, the global pharmaceutical industry is bracing for a wave of expirations that will put an estimated $200 billion to $400 billion in branded drug revenue at risk.1 This is not a gentle decline; it is a catastrophic financial drop. For a small-molecule blockbuster, it is not uncommon to see sales plummet by 80-90% within the first year of generic entry.5

Consider the sheer scale of the assets facing this cliff in the immediate future. Merck’s oncology titan, Keytruda, which generates over $29 billion in annual sales, faces its LOE around 2028.3 Eliquis, the anti-coagulant from BMS and Pfizer, with over $10 billion in sales, sees its key patents expire between 2027 and 2029.1 Johnson & Johnson’s Stelara, another $10 billion asset, faces biosimilar competition in 2025.7

This is the central engine of strategic action in the life sciences. For the executive, the investor, or the intellectual property (IP) strategist, patent expiration is not an end. It is the beginning of a new, high-stakes commercial battle. In this unforgiving arena, the winner is not necessarily the company with the single strongest patent, but the one with the most sophisticated, data-driven, and ruthless strategy.

This report is that strategy guide. It deconstructs the entire ecosystem of pharmaceutical exclusivity, from the legal scaffolding built by the Hatch-Waxman Act to the disruptive new rules of the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA). It details the offensive playbook for the generic and biosimilar challenger and the defensive playbook for the innovator brand. Above all, it demonstrates how, in this game, patent data is not merely a legal archive; it is the most powerful offensive weapon for turning market intelligence into market dominance.

The 2025–2030 Patent Cliff: A Decade’s-Worth of Blockbusters at Risk

To ground this strategic analysis in immediate, tangible reality, the following table outlines the key blockbuster assets and their approximate U.S. loss of exclusivity (LOE) timelines. These drugs represent the epicenter of the financial quake that will reshape the industry.

| Drug Name (Brand) | Innovator Company | Primary Indication | 2023/2024 Sales (Approx.) | Key U.S. Patent Expiration Year(s) |

| Keytruda (pembrolizumab) | Merck | Oncology | ~$29.5 Billion | ~2028 3 |

| Eliquis (apixaban) | BMS / Pfizer | Anticoagulant | >$10 Billion | ~2027-2029 1 |

| Opdivo (nivolumab) | Bristol Myers Squibb | Oncology | ~$9 Billion | ~2028 7 |

| Stelara (ustekinumab) | Johnson & Johnson | Immunology | ~$10.8 Billion | ~2025 7 |

| Eylea (aflibercept) | Regeneron / Bayer | Ophthalmology | ~$5.9 Billion (US) | ~2025-2026 4 |

| Ibrance (palbociclib) | Pfizer | Oncology | ~$4.7 Billion | ~2027 4 |

| Xarelto (rivaroxaban) | Bayer / J&J | Anticoagulant | ~$4.5 Billion (Bayer) | ~2026 4 |

| Trulicity (dulaglutide) | Eli Lilly | Diabetes | ~$7.1 Billion | ~2027 4 |

| Ocrevus (ocrelizumab) | Roche | Multiple Sclerosis | ~$7.1 Billion | ~2028-2029 4 |

| Prolia/Xgeva (denosumab) | Amgen | Osteoporosis/Oncology | ~$6.5 Billion (Combined) | ~2025-2026 4 |

Sales figures and expiration dates are approximations based on public reporting, company statements, and patent litigation settlements. Effective LOE can change.

Part 1: The Anatomy of the Cliff – Deconstructing Pharmaceutical Exclusivity

Before a company can defend its exclusivity or a challenger can attack it, both must understand what “exclusivity” truly means. It is not a single wall, but a fortress built of multiple, distinct layers of legal and regulatory protection.

The Myth of the 20-Year Patent: Understanding “Effective Patent Life”

There is a popular and dangerously simplistic misconception that a new drug receives a 20-year monopoly. While a U.S. patent does have a 20-year term from its filing date 12, the “effective patent life”—the actual period of time a drug is on the market with no competition—is tragically shorter.

Patents are the “financial engine” of the pharmaceutical industry, the core incentive that justifies the staggering R&D investment required to bring a novel medicine to patients.5 But to be effective, that patent must be filed early in the discovery process, often before the molecule has even been tested in animals.

From that filing date, the clock starts ticking. The drug must then endure a long, arduous, and costly journey:

- Preclinical toxicology and pharmacology studies.

- Phase 1, 2, and 3 clinical trials, a process that can take 6-8 years on its own.

- A 1-2 year review by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for a New Drug Application (NDA).

All this time, the 20-year patent term is burning away. The result is that by the time a drug is approved for sale, a massive portion of its patent life is already gone. The actual period of market exclusivity—the effective patent life—is typically only 7 to 12 years.5 This compressed timeline is the “crucible”.5 It creates the intense, front-loaded pressure that necessitates the aggressive commercial and lifecycle strategies that define the industry.

The Bulwark: A Multi-Layered Defense of Exclusivity

No blockbuster drug relies on a single patent. The modern exclusivity strategy is a multi-layered bulwark, a defense-in-depth designed to protect the franchise from every angle.5

- Layer 1: Composition of Matter (CoM) Patents. This is the “crown jewel” of the portfolio, the core patent that claims the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API), the molecule itself.5 This is the strongest form of protection, and its expiration date is the one circled in red on every competitor’s calendar.

- Layer 2: Secondary Patents (The “Thicket”). A savvy innovator never stops at the CoM. It builds a “patent thicket”—a dense web of hundreds of follow-on patents—around the core product.5 These are not “weak” patents; they are strategic assets designed to create legal and commercial hurdles for a generic challenger. Key types include:

- Method of Use: Patents on how the drug is used, such as claiming a new disease it can treat (a new indication).5

- Formulation: Patents on the delivery system, such as an extended-release (XR) version, a specific coating, a different concentration, or a pre-filled syringe.5

- Process (Methods of Manufacture): Patents on the specific, novel, and cost-effective way the drug is synthesized or purified.5

- Polymorphs & Enantiomers: Patents on specific crystalline forms or stereoisomers of the molecule that may offer stability or bioavailability advantages.

- Layer 3: FDA Regulatory Exclusivities. Wholly separate from patents (which are granted by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, or USPTO), these are market protections granted by the FDA upon approval.12 They run concurrently with patents and serve as a critical backstop. If a core patent is invalidated in court, these exclusivities can still block generic entry. Key types include:

- New Chemical Entity (NCE) Exclusivity: 5 years of data exclusivity for a small-molecule drug containing an active ingredient never before approved by the FDA.14

- Orphan Drug Exclusivity (ODE): 7 years of market exclusivity for a drug that treats a rare disease (affecting fewer than 200,000 people in the U.S.).5

- New Clinical Study Exclusivity: 3 years of protection for a new indication or formulation that required new clinical trials to approve.15

- Pediatric Exclusivity: A 6-month “bonus” added to all existing patents and exclusivities for the drug as a reward for conducting studies in children.5 As seen in the case of Lipitor, this 6-month extension on a multi-billion dollar drug can be worth a fortune.16

The Market Data Battleground: Orange Book vs. Purple Book

How does a challenger know which patents and exclusivities to fight? The FDA maintains two critical, yet fundamentally different, public databases that serve as the official “maps” of the exclusivity battlefield. Understanding their differences is key to understanding the strategic divergence between the generic and biosimilar markets.

- The Orange Book (Small Molecules): The FDA’s Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations 17 is the bible for the generic industry. Mandated by the Hatch-Waxman Act, it requires innovator companies to proactively list all the patents they claim cover their approved small-molecule drugs.17 For a generic challenger, the Orange Book is a comprehensive roadmap for litigation. It is a “menu” of patents that the generic company must certify against, allowing it to plan its entire legal and commercial strategy before investing millions in development.

- The Purple Book (Biologics): The Lists of Licensed Biological Products with Reference Product Exclusivity and Biosimilarity or Interchangeability Evaluations 17 is a vastly different and more recent creation. It serves the same purpose for biologics and their “biosimilar” competitors, but with critical, game-changing limitations.

The strategic difference between these two books cannot be overstated. The Orange Book is a model of proactive transparency, providing a clear target for generic challengers. The Purple Book, by contrast, creates a structural barrier of asymmetric information that heavily favors the innovator.

For years, the Purple Book did not even list patents. While recent legislation has added this requirement, it comes with crippling limitations. Unlike the Orange Book, innovators are often not required to post their patent information until after a biosimilar applicant has already filed its application.20 Even then, the patents are often “revealed for the first time during the litigation itself” 21, and the innovator has no statutory obligation to keep the list current.20

This forces the biosimilar developer to “fly blind.” A company must invest hundreds of millions of dollars and several years to develop its “highly similar” biologic and build a manufacturing facility, all without knowing the full scope of the patent landscape it will have to litigate. This asymmetric information risk, built directly into the data structure of the BPCIA, is a fundamental defensive moat for the innovator and a key reason why the biosimilar market is far less competitive than its small-molecule counterpart.

Part 2: The Small-Molecule Battlefield – How Hatch-Waxman Wrote the Rules of War

To understand the modern pharmaceutical market, one must return to 1984. The Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act, universally known as the Hatch-Waxman Act, is arguably the most brilliant and impactful piece of industrial legislation of the 20th century. It didn’t just regulate an industry; it created a battlefield, complete with a “great compromise” that armed both sides and guaranteed a permanent, high-stakes conflict.15

The Great Compromise: A Masterpiece of Strategic Incentives

The Act was a delicate balance, a “great compromise” designed to solve two problems at once: how to incentivize generic competition while also rewarding and protecting brand innovation.15

What the Innovator (Brand) Got:

- Patent Term Extension: For the first time, brands could “recapture” a portion of the patent life that was lost during the lengthy FDA review process, extending the back end of their monopoly.14

- Regulatory Exclusivity: The creation of the 5-year NCE and 3-year new clinical study exclusivities, which act as a “generic-proof” firewall for a set period, even if patents are weak or non-existent.14

What the Challenger (Generic) Got:

- The ANDA Pathway: The Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) pathway was the generic industry’s genesis. It allowed generics to get to market by simply proving bioequivalence (that their drug behaved the same in the body) rather than repeating the brand’s multi-decade, billion-dollar clinical trials.5

- The “Safe Harbor”: The Act created a “safe harbor” allowing generic companies to conduct R&D and testing during the innovator’s patent term without being sued for infringement.15 This ensured the generic could be “ready to launch” on Day 1 post-expiration.

- The Golden Ticket: The most powerful incentive of all—a 180-day period of market exclusivity awarded to the first generic company to successfully file an ANDA that challenged the brand’s patents.15

The success of this framework is undeniable. Before Hatch-Waxman, generics accounted for just 19% of U.S. prescriptions. Today, that number is over 90%.22 The 2025 U.S. Generic & Biosimilar Medicines Savings Report found that generics and biosimilars saved the U.S. healthcare system $467 billion in 2024 alone, and $3.4 trillion over the past decade.24

“90% of U.S. Prescriptions Filled, 12% of Rx Drug Spending”

The Golden Ticket: The Economic Power of 180-Day Exclusivity

Why is the 180-day exclusivity the “golden ticket”? Because it is a “very strong financial incentive” 26 that effectively creates a “mini-patent” for the first generic challenger.27

During this 6-month window, the “first-to-file” generic is the only generic on the market, creating a duopoly with the brand. It can capture massive market share, often at a price only 10-20% below the brand, rather than the 90% drop seen when multiple generics enter.

The ROI is staggering. Generic companies widely estimate that 60% to 80% of their entire potential profit for a given product is made during this 180-day window.27 Profits “fall sharply” once this period ends and the market becomes a commodity free-for-all.27 This massive, front-loaded reward is precisely what Congress designed to “encourage generic applicants to challenge a listed patent”.23 It is the fuel for the entire pharmaceutical litigation engine.

The Gauntlet: Paragraph IV Certification and the 30-Month Stay

Hatch-Waxman forces the conflict through a brilliant and unavoidable legal gauntlet. To win the 180-day prize, a generic company must file an ANDA that includes a “certification” for every patent the brand has listed in the Orange Book.29

- Paragraph I: No patent information filed.

- Paragraph II: The patent has already expired.

- Paragraph III: The generic will wait until the patent expires to launch.

- Paragraph IV (The “Act of War”): The generic applicant formally declares that, in its opinion, the brand’s patent is “invalid, unenforceable, or will not be infringed by the generic product”.5

This P.IV certification is the only way to trigger the 180-day exclusivity.

Once the generic files this P.IV challenge, it must send a “Notice Letter” to the brand-name company and patent owner, providing a detailed factual and legal basis for its challenge.30

This is where the genius of the system’s “mutually-assured-conflict” design becomes clear. Once the brand receives this notice letter, a 45-day clock starts. If the brand files a patent infringement lawsuit against the generic within that 45-day window…29

…it triggers an automatic 30-month stay of the FDA’s approval of the generic’s ANDA.30

This 30-month stay is the central economic lever of the entire Hatch-Waxman system. It is a brilliant, self-perpetuating conflict generator that funnels both rational, profit-seeking parties directly into federal court.

Think about the incentives. The generic must file a P.IV to have a chance at the 180-day prize. But the act of filing the P.IV gives the brand the right to automatically block the generic’s approval for 2.5 years, a “free” market extension (pending the litigation outcome). The brand always sues. The generic wants to be sued, as this is the only path to “locking in” its first-to-file status. The system weaponizes time, pitting a 180-day jackpot against a 30-month delay, and guarantees that for every valuable drug, there will be a lawsuit.

The Ultimate Gamble: The “At-Risk Launch”

What happens if the 30-month stay expires, but the patent litigation is still grinding through the courts? The FDA is now free to approve the generic’s ANDA. The generic company then faces one of the highest-stakes decisions in all of business: the “at-risk launch”.35

The generic can choose to launch its product and start capturing market share while the patent case is still being decided.

- The Reward: If the generic ultimately wins the lawsuit, it has had the market to itself (or with few competitors) for months or even years, reaping hundreds of millions in profits.

- The Risk: If the generic loses the lawsuit, it is liable for catastrophic damages, often calculated as the brand’s total lost profits—an amount that can easily run into the billions.36

This decision is not a legal one; it is a complex, scenario-based financial model.35 The generic’s executive team must weigh the Net Present Value (NPV) of at-risk profits against the potential for a company-ending damages award, all weighted by their confidence in the legal case.

Case Study: The Protonix “At-Risk” Disaster

This gamble is not theoretical. In 2007, the generic manufacturers Teva and Sun were so confident in their legal arguments against Wyeth’s (later Pfizer’s) patents on the blockbuster acid-reflux drug Protonix (pantoprazole) that they launched their generic versions “at-risk”.37

Their confidence was misplaced. In 2010, a jury rejected their claims of non-infringement and invalidity. The result was one of the largest patent settlements in pharmaceutical history: Teva and Sun were forced to pay a staggering $2.15 billion in damages.37

The Protonix case serves as a permanent, chilling reminder of the stakes. It also demonstrates why access to deep litigation data—like that provided by platforms such as DrugPatentWatch—is not a luxury. Understanding a competitor’s willingness to risk billions, and the legal arguments they used, is critical intelligence for modeling these multi-billion dollar decisions.37

Part 3: The New Frontier – Biologics and the Biosimilar Challenge

While the Hatch-Waxman Act defined the rules for small-molecule drugs, a new and far more complex battlefield has emerged. This is the world of biologics—and their would-be competitors, biosimilars.

A Different Beast: Why Biologics Aren’t Just “Big Pills”

The first and most important concept to grasp is that biologics are fundamentally different from the small-molecule “pills” governed by Hatch-Waxman.

- Small Molecules (Generics): These are simple, stable, chemically synthesized compounds with well-defined structures.17 Think of a bicycle—every component is known, and it can be replicated identically by any competent manufacturer. This is what allows a generic to prove “bioequivalence.”

- Biologics (Biosimilars): These are large, highly complex proteins—such as monoclonal antibodies—derived from living organisms like yeast or mammalian cell cultures.17 Think of a racehorse. Even if you have the parents, you cannot guarantee the offspring will be identical. Biologics are exquisitely sensitive to their manufacturing environment. The “process is the product.”

Because an identical copy is scientifically impossible, a “generic” biologic cannot exist. This fundamental difference in science is why a completely different legal and regulatory framework was needed.39

The Labyrinth: Decoding the BPCIA 351(k) Pathway

Enacted in 2010 as part of the Affordable Care Act, the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA) created the new abbreviated pathway for biosimilars.38 This pathway, known as Section 351(k), is a labyrinth compared to the streamlined ANDA process.41

It created two distinct, new tiers of approval:

- The “Biosimilar” Standard: The challenger must demonstrate its product is “highly similar” to the innovator’s “reference product.” More importantly, it must prove there are “no clinically meaningful differences” between the two in terms of safety, purity, and potency.41 This requires a significant data package, often including head-to-head clinical trials, making development costs exponentially higher than for a simple generic.

- The “Interchangeable” Standard: This is a higher and far more commercially valuable tier of approval. To earn this designation, the biosimilar applicant must conduct additional switching studies 41 to prove that a patient can be moved back and forth between the brand and the biosimilar multiple times with no change in safety or efficacy.

This two-tiered system is a massive defensive moat for innovators. Under Hatch-Waxman, all approved generics are “A-rated” and automatically “interchangeable,” meaning a pharmacist can substitute them for the brand at will.42

Under the BPCIA, this is not the case. A product approved only as “biosimilar” (without interchangeability) cannot be automatically substituted at the pharmacy. This shatters the entire low-cost, high-volume generic business model. A non-interchangeable biosimilar company must deploy its own full-scale sales force to visit doctors and actively convince them to specifically prescribe their product over the trusted, time-tested reference brand. This commercial hurdle, far more than the science, is what has protected innovator biologics for so long.

“Shall We Dance?”: The Biosimilar Patent Dance Explained

To manage the even-more-complex patent issues surrounding biologics (where “process” patents are as important as “composition” patents), the BPCIA created an intricate, multi-step process for exchanging information and defining the scope of litigation. It was so complex that it was immediately nicknamed the “Patent Dance”.43

The dance involves a series of rigid, timed steps:

- Step 1: Within 20 days of the FDA accepting its 351(k) application, the biosimilar applicant “shall” provide a copy of its entire application and manufacturing information to the innovator company (the “Reference Product Sponsor” or RPS).43

- Step 2: The RPS then has 60 days to provide the applicant with a list of all patents it believes could be infringed.

- Step 3: The applicant must respond with its detailed legal arguments for why each patent is invalid, unenforceable, or not infringed.

- Step 4: The RPS responds to that… and so on.

This “dance” is designed to identify and narrow the list of patents to be litigated in a “first wave” of litigation.45

However, the BPCIA was not a model of legislative clarity. Challengers immediately began to question whether this entire, burdensome process was truly mandatory. The question went all the way to the Supreme Court.

In Sandoz v. Amgen (2017), the Court delivered two bombshells:

- The entire “Patent Dance” is optional.46 An applicant can refuse to dance and opt out of the information exchange, though there are legal consequences for doing so (namely, the innovator can immediately sue on any and all patents it wishes).

- The BPCIA’s other key timing provision—a required 180-day notice of commercial marketing—is mandatory. However, the Court ruled that this notice can be given before or after FDA approval, allowing biosimilar companies to give notice “at-risk” and launch immediately upon licensure.46

Market Reality Check: U.S. vs. E.U. Biosimilar Uptake

The BPCIA was intended to create a thriving biosimilar market, but its results in the U.S. have been mixed, especially when compared to Europe.47 European nations, with single-payer health systems, have seen rapid and deep biosimilar adoption, with some reference biologics losing 80-90% of their market share within a year.48

In the U.S., adoption has been far slower. This is due to the strategic trifecta of innovator defenses:

- Patent Thickets: Innovators have used patent thickets to sue and settle with biosimilar challengers, often delaying entry for years (as seen with Humira).

- The Interchangeability Barrier: The high cost and difficulty of achieving “interchangeable” status has limited automatic substitution, crippling the biosimilar business model.

- A Fragmented Payer System: The complex U.S. system of rebates and formularies has, in some cases, made it more profitable for Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs) to keep the high-list, high-rebate brand on formulary than to adopt the low-list, low-rebate biosimilar.

Despite these hurdles, the market is maturing. In therapeutic areas like oncology, where physicians in clinics (rather than PBMs) make the purchasing decisions, biosimilar uptake has been robust and rapid.49 And the fundamental economics of a “race-to-market” still hold: data shows that the first two to three biosimilar entrants typically capture more than 90% of the market share.49 The stakes remain incredibly high.

The Two Battlefields: Hatch-Waxman (Generic) vs. BPCIA (Biosimilar)

For the strategist, understanding the fundamental differences in these two legal frameworks is the first step to building a winning commercial plan.

| Feature | Hatch-Waxman (Small-Molecule Generic) | BPCIA (Biologic / Biosimilar) |

| The Law | 1984, Drug Price Competition & Patent Term Restoration Act | 2010, Biologics Price Competition & Innovation Act (ACA) |

| The Product | Chemically synthesized, simple, identical copy possible. | From living organisms, complex, “highly similar” copy. |

| Approval Pathway | Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) | 351(k) Abbreviated Biologics License Application (aBLA) |

| Key Standard | Bioequivalence (identical) | Biosimilarity (highly similar, no clinical differences) |

| Key Database | Orange Book 17 (Proactive, comprehensive patent list) | Purple Book 17 (Reactive, incomplete patent list) |

| Key Market Incentive | 180-Day “First-to-File” Exclusivity 15 | 12-Year “Reference Product” Exclusivity (for brand); “Interchangeable” Status (for challenger) 41 |

| Core Litigation | Paragraph IV Challenge 29 | The “Patent Dance” 43 |

| Automatic Stay? | Yes: Triggers 30-Month Stay of FDA approval.34 | No: No automatic stay; innovator must seek a preliminary injunction. |

Part 4: The Innovator’s Playbook – Defensive Strategies for Lifecycle Management

When a multi-billion dollar franchise is on the line, innovator companies do not simply wait for the clock to run out. They deploy a sophisticated, multi-year, and highly aggressive “Lifecycle Management” (LCM) playbook.50 This is a “war of attrition” fought on legal, regulatory, and commercial fronts. The goal: extend the monopoly, delay generic entry, and maximize revenue for every possible day.

Strategy 1: The “Patent Thicket” and “Evergreening”

This is the most famous—and infamous—defensive strategy. It involves building a “dense web of overlapping intellectual property rights” 13—a “thicket”—of hundreds of secondary patents around a single drug. This is also known as “evergreening,” the process of serially filing new patents to extend the product’s life.53

The goal is not necessarily to win 250 individual lawsuits. The goal is to make the cost, time, and uncertainty of litigating all of them so prohibitively high that no generic competitor will dare to try.52 It is a strategy of “delay or deter” 13, creating a legal and commercial “uncertainty” that a generic challenger, and its investors, cannot stomach.52

Case Study: AbbVie’s Humira (adalimumab)

Humira is the canonical, most-studied, and most successful example of the patent thicket strategy in history.

- The Prize: The world’s best-selling drug, Humira (adalimumab) generated peak annual sales of $21.2 billion in 2022.55 In 2021 alone, it brought in “almost $21 billion… around $57 million a day”.13

- The Thicket: Humira’s core “composition of matter” patent expired in the U.S. in December 2016.55 By all rights, biosimilars should have entered in 2017. They did not. Why? Because AbbVie had built an impenetrable fortress. The company applied for or obtained over 250 patents.56 When biosimilars were preparing to launch, AbbVie had over 132 active patents protecting Humira.13

- The “Evergreen” Data: The most telling statistic is when these patents were filed. Research shows that approximately 90% of the patent filings for Humira were made after the drug was already on the market.13 These were not patents on a new invention, but patents on the preservation of a monopoly.

- The Result: The strategy worked perfectly. Biosimilar competitors like Amgen, Sandoz, and Boehringer Ingelheim, each with an approved product, were faced with a “thicket” of over 100 patents. The cost and risk of litigating them all was too high. One by one, they all settled with AbbVie, agreeing to a licensed market entry date of 2023.45 AbbVie successfully, and legally, used its patent thicket to secure an additional seven years of U.S. monopoly, worth well over $100 billion.

Strategy 2: The “Authorized Generic” (AG)

This is a brilliant “cannibalize and conquer” strategy. When a P.IV challenger (the “first-filer”) is set to launch and enjoy its 180-day exclusivity, the innovator brand does something unexpected: it launches its own generic version on the same day.58 This “authorized generic” (AG) is the exact same branded product, just in a different bottle, often sold through a partner company.

Case Study: Pfizer’s Lipitor (atorvastatin)

Pfizer’s defense of Lipitor is a masterclass in aggressive, multi-pronged LOE strategy.

- The Prize: Lipitor was a pharmaceutical goliath, with peak annual sales of $12.9 billion in 2006.16

- The Cliff: The main U.S. patent expired on November 30, 2011.16 The generic firm Ranbaxy had secured the “golden ticket”—the 180-day exclusivity for being the first-to-file a P.IV challenge.59

- Pfizer’s “180-Day War” 16: Pfizer refused to surrender. It executed a three-pronged counter-attack to destroy the value of Ranbaxy’s exclusivity:

- Launch an AG: Pfizer signed a deal with Watson Pharmaceuticals to launch an authorized generic version of atorvastatin, manufactured by Pfizer itself.59 This allowed Pfizer to instantly capture a huge portion of the “generic” market. Crucially, Pfizer was estimated to retain approximately 70% of the profits from Watson’s AG sales.59

- Subsidize the Brand: Pfizer launched a massive direct-to-patient program called “Lipitor for You”.16 This program offered co-pay cards that dropped the patient’s out-of-pocket cost for branded Lipitor to as little as $4 per month.16 This made the brand cheaper than the generic for many insured patients.

- Leverage Brand Loyalty: Pfizer had spent over a decade and hundreds of millions on direct-to-consumer advertising, like the famous Robert Jarvik “I take Lipitor instead of a generic” campaign.61 This created a powerful “brand stickiness” and sowed just enough doubt about generics to convince many patients and doctors to stay with the brand, especially when it was now just $4.

- The Result: Pfizer’s strategy was a resounding success. Ranbaxy, which had expected a 180-day monopoly, instead found itself in a 3-way market war against (1) the heavily subsidized brand, (2) the Pfizer-backed AG, and (3) its own product. Pfizer fundamentally devalued the 180-day prize. It conceded the “generic” market, but by doing so, kept 70% of the profits from it.59

Strategy 3: “Product Hopping”

“Product hopping” is a subtle but powerful evolution of the patent thicket. The strategy is to “hop” the market from an old, soon-to-be-off-patent product to a new, patent-protected version.

The classic “hop” involves launching a minor variation—such as a new extended-release formulation or a different dosing schedule—shortly before the original product’s patent expires.56 The innovator then uses its entire sales force and marketing muscle to aggressively “switch” doctors and patients to the new version.

When the generic version of the original product finally launches, it finds the market has already moved on. The generic is stranded, launching a product that no one uses or prescribes anymore, making it an “imperfect substitute”.56

Case Study: AbbVie’s Humira (Revisited)

AbbVie, the master of the thicket, is also a master of the hop. In the run-up to the 2023 biosimilar entry, AbbVie executed a classic “product hop”.56

- The Hop: It heavily marketed and transitioned a large portion of the market from the original Humira formulation to a new, high-concentration, less-painful (citrate-free) formulation.56

- The Trap: The biosimilars set to launch in 2023 were approved based on studies against the original formulation. They are not automatically interchangeable with the new, high-concentration formulation that now dominates the market.

- The Result: This hop again shatters the biosimilar business model. It blocks automatic pharmacy-level substitution and forces biosimilar companies back into the expensive, brand-style marketing of convincing doctors to specifically switch patients back to an “older,” (perceived) more-painful formulation.

Strategy 4: The Rx-to-OTC Switch

This strategy attempts to bypass the patent cliff entirely. Instead of fighting generics in the prescription (Rx) market, the innovator converts its product to an over-the-counter (OTC) medicine. The goal is to leverage the massive brand equity and name recognition—built by years of Rx-only status and advertising—into a new, long-term, and dominant consumer health franchise. The innovator can then command a premium price as a trusted OTC brand, surviving long after the patent has expired.

Case Study: Claritin (loratadine) & Zyrtec (cetirizine)

This is one of the most famous examples, but with a twist: the innovators were forced into the switch.

- The Threat: In the late 1990s, second-generation antihistamines like Claritin, Zyrtec, and Allegra were prescription-only blockbusters. Health insurers, led by Blue Cross of California (WellPoint), were spending a fortune on them.62

- The Catalyst: In 1998, WellPoint filed a Citizen Petition with the FDA.62 This petition demanded that the FDA force the switch of these drugs from Rx-to-OTC, arguing they were incredibly safe (non-sedating) and that consumers could easily self-administer them.62

- The Conflict: The drug manufacturers (Schering-Plough, Pfizer, etc.) aggressively opposed the switch. The insured prescription market was far more profitable than the cutthroat, out-of-pocket OTC market.62

- The Outcome: The FDA advisory committees ultimately agreed with WellPoint.63 The switch happened. The innovators lost their prescription monopoly, but the story didn’t end there. They successfully transitioned Claritin and Zyrtec into dominant, premium-priced consumer brands that still command massive market share and revenue today, even in the face of cheaper generic OTC versions.64 They survived the patent cliff by “hopping” to a new battlefield: the consumer pharmacy aisle.

Strategy 5: Legal and Regulatory Delay Tactics

When all else fails, the final line of defense is to use the legal and regulatory system itself to create delays, buying precious months or even years of additional monopoly sales.

- A) “Pay-for-Delay” / Reverse Payment Settlements:

This tactic involves the brand-name innovator paying the generic challenger to delay its market entry.23 The brand pays the “first-to-file” generic to settle the P.IV lawsuit and abandon its patent challenge. Because these deals were often seen as de facto market division, they attracted intense scrutiny from the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), which now views them as presumptively illegal.67 As a result, simple cash payments are gone. The practice has evolved into “complex side business deals” 68—such as a co-promotion agreement or a supply deal—that are harder for regulators to unwind but achieve the same anti-competitive delay. - Case Study: Novartis’ Gleevec (imatinib):

Novartis’s blockbuster cancer drug Gleevec faced P.IV challenges from generic makers. The company reached a settlement with the first-filer, Sun Pharma.69

- The Deal: The Gleevec patent was set to expire in July 2015. The settlement, however, stipulated that Sun Pharma would delay its generic launch for an additional 7 months, until February 2016.69

- The Kicker: This delay was worth an estimated 6% boost to Novartis’s 2015 earnings per share.69 But the real nuance emerged after the launch. When Sun Pharma did launch its “generic” in 2016, with its 180-day exclusivity, its “generic price” was “not much lower than the branded drug price”.58 This suggests a shared duopoly was created. Novartis avoided the 90% price cliff, and Sun Pharma enjoyed a 180-day, high-margin payday without having to compete against an Authorized Generic. The only loser, in this scenario, was the payer.

- B) The “Citizen Petition” (CP):

The FDA allows any “citizen” (including corporations) to file a petition raising concerns about a drug’s safety or efficacy.70 Innovator companies have historically used this process as a last-ditch delay tactic. Just weeks or days before a generic’s approval is due, the brand will file a CP raising new, complex scientific questions about the generic’s bioequivalence, manufacturing standards, or potential safety risks.71 While the FDA rarely grants these petitions, it is statutorily required to review and respond to them. The resulting delay, even if only for a few months, can be worth tens or hundreds of millions of dollars in extended monopoly sales.

Part 5: The New Apocalypse – How the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) Changes Everything

For 40 years, the Hatch-Waxman and BPCIA frameworks were the game. The innovator’s playbook, while complex, was known. Strategies were built around patent expiration dates, 30-month stays, and 180-day exclusivities.

In 2022, that entire game board was flipped over.

The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) has fundamentally rewritten the rules of pharmaceutical exclusivity. It has introduced a new and unavoidable loss of exclusivity event that is completely untethered from a company’s patent portfolio. For strategists, the IRA is not a minor policy tweak; it is an existential threat and a forced realignment of all R&D and commercial strategy.

The “New” Patent Cliff: Price “Negotiation” as Forced Exclusivity Loss

The IRA’s most potent provision empowers the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) to “negotiate” a Maximum Fair Price (MFP) for a select list of the highest-spending single-source drugs in the Medicare program.72

This “negotiation” is not a typical back-and-forth. It is, for all intents and purposes, a price-setting mechanism backed by a crippling excise tax for non-compliance.

Here is why this is a strategic bombshell:

- It Creates a New, Non-Patent LOE: The IRA creates a new, artificial, non-patent-based Loss of Exclusivity date.73 A drug can have a “thicket” of 100 valid patents lasting for another decade, but if it’s selected for negotiation, its price is cut by government decree.

- It Has a “Contagion Effect”: The MFP is not a secret. It is public.74 While the law technically only applies to Medicare, this public price point gives “unprecedented leverage” to all other payers.74 Commercial PBMs and insurers will walk into their own negotiations and ask a simple question: “Why should we pay a net price of $500 when you just agreed to sell to Medicare for $200?” The MFP will, in effect, become a new, public price ceiling that will be exported to the entire U.S. market.73

The “Pill Penalty”: A Strategic Bombshell for R&D Portfolios

The IRA’s most controversial and strategically potent provision is a small, technical-sounding distinction that has been nicknamed the “pill penalty”.75

The law does not treat all drugs equally. It creates two different “clocks” that determine when a drug becomes eligible for price negotiation:

- Small-Molecule Drugs (Pills): Eligible for negotiation just 9 years after their FDA approval date.76

- Biologics (Large Molecules): Eligible for negotiation only after 13 years from their FDA approval date.76

This 4-year difference—the “pill penalty”—is not a minor tweak. In pharmaceutical economics, the last few years of a drug’s lifecycle (e.g., years 9 through 13) are the most profitable, “peak revenue” years. The brand is well-established, marketing costs are lower, and the drug is at its maximum adoption.

The IRA systematically carves out this most valuable economic period for small molecules, while leaving it entirely intact for biologics.

This creates a massive, structural disincentive for R&D in small-molecule drugs.77 A rational investor or a Big Pharma business development team, when faced with two promising assets for the same disease (e.g., oncology), must now make a simple calculation:

- Asset A: A convenient oral pill that patients can take at home. (9-year clock)

- Asset B: A complex, infused biologic that patients must get at a clinic. (13-year clock)

The IRA economically forces the strategist to favor the biologic to gain those four additional years of peak, un-negotiated profitability.

This is not a theoretical, far-future problem. The shift is already happening. New research has found that since the IRA was introduced, aggregate small-molecule investment by companies valued under $2 billion has declined by 68%. For treatments specifically targeting diseases with a high proportion of Medicare beneficiaries, the median size of investments fell by 74%.79 The IRA, in effect, is actively shaping the future R&D pipeline away from convenient pills and toward more complex, costly, and burdensome injected/infused biologics.76

“Cryptic Patent Reform”: How the IRA Defangs the Patent Thicket

For IP strategists, the IRA’s most profound impact is this: it is a form of “cryptic patent reform”.80

The IRA never mentions the word “patent.” It does not change a single line of patent law. And yet, it fundamentally alters the value of every patent in the industry.

Consider the Humira case. Why would AbbVie spend a decade and hundreds of millions building a 250-patent thicket 56 to protect its U.S. monopoly until Year 17 (from launch), if the IRA (a biologic) is just going to step in and set the price at Year 13 anyway?

The IRA’s 13-year (for biologics) or 9-year (for pills) negotiation clock becomes the new, earlier, and unavoidable patent cliff.73

The entire economic model of “evergreening”—of filing late-stage formulation and method-of-use patents to add 3, 5, or 7 more years of exclusivity—has been defanged. The ROI on filing those late-stage patents has just plummeted. The IRA clears the patent thicket ex post 80, not by invalidating the patents, but by making them economically irrational to file.

This forces a complete pivot in lifecycle strategy. Companies must now shift their focus away from late-stage defense (thickets) and toward early-stage maximization: optimizing for launch speed, securing broad market access from Day 1, and maximizing revenue before the new, artificial IRA cliff arrives.

Part 6: Turning Data into Dollars: The ROI of Competitive Patent Intelligence

The battlefield, as described, is a dizzying maze of legal, regulatory, and economic tripwires. The rules are complex, the stakes are measured in billions, and a new, disruptive force (the IRA) has just redrawn the map.

How can leadership teams possibly navigate this?

The answer is that the complexity itself creates the opportunity. The “winner” is no longer the company with the single thickest patent wall. The winner is the company with the fastest and most accurate information. Success in this new era is 100% dependent on high-quality, actionable, and predictive competitive intelligence (CI).

Mindset Shift: “Winning the Market, Not Just the Lawsuit”

The first step is a fundamental mindset shift. Patent data is not a dusty, defensive legal archive managed by outside counsel. It is an offensive commercial radar.68

The goal, as one pharmaceutical expert noted, is that “You don’t need to win the patent, you need to win the market”.83

True market victory “is fundamentally defined by an organization’s adeptness in navigating complex regulatory frameworks, executing agile commercial strategies,… and, critically, prioritizing patient access”.83 This requires transforming raw patent and litigation data from a reactive legal problem into a proactive commercial weapon.

This is where specialized business intelligence platforms, such as DrugPatentWatch, become a non-negotiable part of the executive toolkit. They are designed to aggregate, analyze, and deliver the precise, actionable data needed to execute the strategies discussed in this report.84

The Competitive Intelligence (CI) Playbook

Different players in the ecosystem use this data to answer different, high-value questions. The ROI of a sophisticated CI platform lies in its ability to provide specific, timely answers to all of them.

For the Innovator (Brand) Team (BD, IP, & R&D):

- Threat Anticipation: The brand’s worst-case scenario is being blindsided by a P.IV challenge. A CI platform provides daily alerts on new ANDA filings and P.IV certifications.85 This is an early warning system that provides time to prepare the 30-month stay litigation.

- M&A and In-Licensing: The Business Development team, tasked with “buying” new revenue to fill the patent cliff gap 2, uses patent portfolio analysis to evaluate potential M&A targets or in-licensing partners.86 DrugPatentWatch allows them to assess the strength and durability of a target’s patent estate before making a billion-dollar offer.88

- “White Space” R&D: The R&D team can use patent landscape analysis to find the “white space” in a crowded therapeutic area. By seeing where competitors are filing, they can “design around” them and focus on novel, non-infringing pathways, transforming a legal tactic into a source of genuine innovation.68

- Global Lifecycle Management: The game is global. A platform that tracks patent status in 130+ countries 89, alongside local regulatory exclusivities 88, allows the brand to plan a staggered global lifecycle, optimizing for each market’s unique rules.

For the Challenger (Generic/Biosimilar) Team:

- High-Value Target Identification: The generic’s portfolio management team uses the platform to screen for the most profitable targets: drugs with high annual sales, near-term patent expirations, and (ideally) a weak or thin patent thicket.85

- “De-Thicketing”: Before challenging a Humira-style blockbuster, the legal team must map the entire thicket—CoM, formulation, method-of-use, and manufacturing patents. A comprehensive database is the only way to find the “weakest link” in the chain to target for a P.IV challenge.52

- Securing the “Golden Ticket”: The 180-day exclusivity is a “first-to-file” race. “First-to-file analysis” 88 is critical. This involves not only filing first but monitoring competitors to see if anyone else filed on the same day, which would force a shared exclusivity.

- Supply Chain Security: A generic drug is useless without a secure supply of its Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API). CI platforms that identify API manufacturers 85 are essential for securing the supply chain months or years before a planned launch.

For the Investor, Payer, and Wholesaler:

- Investors (Equity Analysts): A pharma company’s stock price is directly tied to its patent cliff.91 Analysts use precise LOE forecasting models 7 to predict revenue erosion and update their “sell” or “buy” ratings.

- Payers (Insurers/PBMs): Formulary and budget management teams use patent expiration forecasts to project future drug spend.89 Knowing that a $20 billion biologic is going biosimilar in 2025 allows them to build that 90% cost saving into their next year’s budget.

- Wholesalers & Distributors: The “at-risk” problem also applies to inventory. A wholesaler “stuck” with a warehouse full of high-cost branded Lipitor on December 1st, 2011, when the cheap generic launched, would face a massive financial loss. They use “advance notice of patent expiry to avoid over-stocking off-patent drugs”.89

The real ROI of CI is not in reacting to these events, but in predicting them. Sophisticated teams use platforms like DrugPatentWatch to ask offensive questions: “Which of my competitors is most vulnerable to a P.IV challenge?” “Who are the API manufacturers lining up to supply the generic for their blockbuster?” “What is my P.IV opponent’s litigation history 88—do they typically settle, or do they launch at-risk?”

This is how raw data is transformed into a decisive, multi-billion-dollar competitive advantage.

Part 7: The Bleeding Edge – Future Battlegrounds (2025-2030)

The strategic game is never static. As innovators and challengers adapt to the IRA, new battlegrounds are already emerging. IP strategists must now operate in a world of extreme regulatory uncertainty, where the very rules of the game are in flux.

The Washington Wildcard: The “War on Thickets” Continues

The IRA was just one front in the government’s assault on high drug prices. The “patent thicket” has become a primary target for regulators and politicians.94

In May 2024, the USPTO itself joined the fray. It proposed a new rule package aimed at “promoting competition by lowering the cost of challenging groups of patents”.95

The core of the proposal was a radical change to “terminal disclaimers.” A terminal disclaimer is a tool patent holders use to get a secondary, “obvious” patent approved by “disclaiming” any patent term beyond the original, or “tying” the patents together. The USPTO’s proposed “thicket-buster” rule was simple: if a company built a thicket of 10 patents tied together by terminal disclaimers, and a generic challenger successfully invalidated even one claim on one of those patents… all 10 patents would become unenforceable.95

The reaction was explosive. The FTC loved the proposal, submitting a comment that it would “address practices that can lead to patent system abuse”.98 The patent bar, pharma industry, and former USPTO directors were apoplectic, arguing it was a massive, illegal overreach.97

In December 2024, the USPTO officially withdrew the proposed rule.97 It cited “resource constraints,” which the industry interpreted as bowing to overwhelming political and legal opposition.

But this is a “ceasefire,” not a “peace treaty.” The government’s intent is now perfectly clear. Stakeholders must “keep in mind that the proposed rules were responsive to Congressional concern… and new rules or legislative action could be proposed during the next administration”.97

This regulatory uncertainty itself is a weapon. It devalues the very late-stage patents that form a thicket. Why would a company invest in a 10-patent thicket if a future rule change could cause the entire structure to collapse like a house of cards? This political risk reinforces the IRA’s economic impact, further pushing R&D strategy away from late-stage evergreening.

The Next Frontier: Cell, Gene, and the “Trade Secret Thicket”

While regulators are busy fighting the last war over patent thickets, the next war is already being defined by cutting-edge therapies in cell and gene (C&G).100

For these revolutionary treatments (e.g., CAR-T), the “product” is not a pill. The “product” is a complex, multi-week manufacturing process that involves extracting a patient’s own cells, genetically re-engineering them, growing them in a bioreactor, and re-infusing them.102

How does one “patent” this?

An innovator can patent the core genetic construct or the target.100 But the real value—the “secret sauce” that makes the therapy safe and effective—is the manufacturing know-how.

This is where the strategy pivots. Many C&G therapy companies are protecting their most valuable IP not as patents, but as trade secrets.103

- A patent must be publicly disclosed in detail and expires in 20 years.

- A trade secret (if properly protected) is never publicly disclosed and lasts forever.

This creates a new kind of thicket: an “information thicket.” A would-be “biosimilar” challenger for a CAR-T therapy faces an impossible barrier. It cannot “design around” a manufacturing process it cannot see. It may be scientifically impossible for the challenger to prove its product is “highly similar” without access to the innovator’s trade secrets.

This is the new, durable, non-patent-based moat. It is a form of exclusivity that the current BPCIA framework is completely unequipped to handle, and it will be the defining IP battleground of the next decade.

Conclusion: Navigating the New Map of Exclusivity

The old map of pharmaceutical exclusivity is obsolete. The simple, linear journey from a 20-year patent to a 10-year monopoly is gone. The “patent cliff” is no longer a single, predictable date on a calendar.

The modern strategist must now navigate a far more complex and dynamic landscape, a “map” with multiple, overlapping, and constantly shifting cliffs:

- The Hatch-Waxman Cliff: A P.IV challenge triggering a 30-month stay.

- The BPCIA Cliff: A “Patent Dance” complicated by interchangeability barriers and asymmetric information.

- The IRA Cliff: The new, non-patent “negotiation” clock (9 or 13 years) that can arrive decades before patents are set to expire.

- The Political Cliff: A “war on thickets” from Washington, creating regulatory uncertainty that devalues the very act of late-stage patenting.

Success in this new environment is no longer about building an impenetrable legal fortress. That fortress can now be bypassed (by the IRA) or torn down (by regulators).

Success is about strategic agility. It is about knowing which lever to pull and when: to launch an Authorized Generic, to execute a “product hop,” to settle a P.IV challenge, or to pivot an entire R&D portfolio from pills to biologics.

This level of agility is impossible without deep, predictive, and actionable competitive intelligence. The market no longer belongs to the company with the most patents; it belongs to the company that sees the entire map.

Key Takeaways

- The “Patent Cliff” is Now a “Cliff Series.” Exclusivity is no longer a single date. Innovators face a series of distinct LOE events: patent expiration (P.IV challenge), biosimilar entry (BPCIA), and the new, artificial IRA “negotiation” cliff.

- The IRA’s “Pill Penalty” is an R&D Pivot. The 9-year negotiation clock for pills versus 13 years for biologics is not a minor policy tweak. It is a massive financial disincentive for small-molecule R&D, and data shows investment is already pivoting toward more complex, “safer” biologics.

- The IRA is “Cryptic Patent Reform.” The IRA defangs the patent thicket. By setting an early, unavoidable price cliff, it makes the ROI on filing late-stage “evergreening” patents plummet. The economic incentive to build a 20-year thicket is gone.

- Innovator Defense is a Multi-Pronged War. A successful brand defense is not just about patents. It is a “war of attrition” using a playbook of:

- Patent Thickets (e.g., Humira) to “delay and deter” litigation.

- Authorized Generics (e.g., Lipitor) to “cannibalize and conquer” the generic market, retaining ~70% of profits.

- Product Hopping (e.g., Humira’s new formulation) to make generic/biosimilar launches “imperfect substitutes.”

- The “Golden Ticket” Drives All Generic Strategy. The 180-day exclusivity is the “mini-patent” that fuels the entire generic industry. Generics can make 60-80% of their total profit in this 6-month window, which is why they will risk billions in P.IV litigation (or “at-risk” launches) to get it.

- Biologic Defense is Built on Asymmetry. The biosimilar (BPCIA) challenge is far harder than the generic (Hatch-Waxman) one. The innovator’s defense is built on structural moats: the “Purple Book” (incomplete data), the “Interchangeability” standard (a commercial barrier), and, increasingly, “Trade Secret Thickets” for cell/gene therapies.

- Competitive Intelligence is the New “Crown Jewel.” In this complex environment, victory depends on superior information. CI platforms are no longer a legal tool; they are an offensive commercial weapon for finding targets, anticipating threats, managing supply chains, and (for investors) forecasting revenue.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. Q: What is the “pill penalty” in the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), and why is it so controversial?

A: The “pill penalty” refers to the IRA’s staggered timeline for price negotiation. It makes small-molecule drugs (typically, pills) eligible for Medicare price setting just 9 years after FDA approval, while biologics (large molecules) are “safe” for 13 years.76 This 4-year difference is controversial because it carves out the most profitable peak-revenue years (years 9-13) for pills, but not biologics. Critics argue this creates a massive, artificial disincentive for R&D into new small-molecule drugs, forcing investors and R&D pipelines to pivot toward more complex, costly, and burdensome biologics.77

2. Q: My company’s blockbuster drug is a biologic. Am I safe from the IRA’s “pill penalty”?

A: Yes and no. You are “safe” from the 9-year “pill penalty” clock; your drug will receive the more favorable 13-year clock before it can be selected for negotiation.77 However, you are not safe from the IRA itself. The 13-year clock still acts as a “cryptic patent reform.” If your company (like AbbVie with Humira) built a patent thicket designed to last 17, 18, or 20 years, the IRA’s 13-year negotiation date just made those late-stage patents economically irrelevant. The IRA effectively moves up your loss of exclusivity date by years, independent of your patent strength.

3. Q: What is the difference between a “patent thicket” and “product hopping”?

A: Both are “evergreening” strategies, but they work differently. A patent thicket (e.g., Humira’s 250+ patents) is a legal barrier.13 It uses a “dense web” of patents to make a legal challenge so complex, expensive, and uncertain that competitors (biosimilars) are deterred from even trying, and instead settle for a late entry date.45

A product hop (e.g., Humira’s new high-concentration formula) is a commercial barrier.56 It “hops” the market to a new, patent-protected version of the drug before the generic for the old version launches. When the generic arrives, it finds the market has moved on, making it an “imperfect substitute” that cannot be automatically swapped at the pharmacy.56

4. Q: Why would a brand company (like Pfizer with Lipitor) launch its own generic and compete with itself?

A: This “Authorized Generic” (AG) strategy is a brilliant “cannibalize and conquer” move.58 Pfizer knew it couldn’t stop Ranbaxy’s “first-to-file” generic, which had 180-day exclusivity.59 So, instead of letting Ranbaxy have 100% of the generic market, Pfizer launched its own AG with a partner, Watson.59 This allowed Pfizer to:

- Devalue the 180-day prize: Ranbaxy now faced a competitor from Day 1.

- Retain profits: Pfizer was estimated to keep 70% of the profits from its own AG’s sales.59

Pfizer effectively conceded the “generic” market but did so on its own terms, capturing the lion’s share of the profits from that market, rather than getting 0%.

5. Q: As a generic drug manufacturer, what is the single most important piece of data I need to successfully challenge a brand patent?

A: The most critical data point is “first-to-file” status. The entire generic business model is built on the 180-day exclusivity “golden ticket,” which is only available to the first “substantially complete” ANDA with a Paragraph IV certification.29 Before any other analysis, a generic company must know: “Can we be first?” This requires a sophisticated competitive intelligence system—like DrugPatentWatch—that provides “first-to-file analysis”.88 This system monitors all competitor ANDA filings in real-time, allowing a company to know if the 180-day prize is still on the table, or if it has already been claimed by a competitor.

Works cited

- Learning from the Pharmaceutical Industry: How to Avoid a Patent Cliff – Caldwell Law, accessed November 9, 2025, https://caldwelllaw.com/news/learning-from-the-pharmaceutical-industry-how-to-avoid-a-patent-cliff/

- The Multi-Billion Dollar Countdown: Decoding the Patent Cliff and Seizing the Generic Opportunity – DrugPatentWatch, accessed November 9, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/patent-expirations-seizing-opportunities-in-the-generic-drug-market/

- Big Pharma Prepares for ‘Patent Cliff’ as Blockbuster Drug Revenue Losses Loom, accessed November 9, 2025, https://www.tradeandindustrydev.com/industry/bio-pharmaceuticals/big-pharma-prepares-patent-cliff-blockbuster-drug-34694

- Top drug patent expirations in next 5 years – Proclinical, accessed November 9, 2025, https://www.proclinical.com/blogs/2024-2/top-10-drugs-with-patents-due-to-expire-in-the-next-5-years

- The End of Exclusivity: Navigating the Drug Patent Cliff for …, accessed November 9, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-impact-of-drug-patent-expiration-financial-implications-lifecycle-strategies-and-market-transformations/

- The Patent Cliff’s Shadow: Impact on Branded Competitor Drug Sales – DrugPatentWatch, accessed November 9, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-effect-of-patent-expiration-on-sales-of-branded-competitor-drugs-in-a-therapeutic-class/

- Advanced Models for Predicting Pharma Stock Performance in the Face of Patent Expiration, accessed November 9, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/advanced-models-for-predicting-pharma-stock-performance-in-the-face-of-patent-expiration/

- Bargain Hunting After Drug Patent Expirations: A Contrarian Investment Strategy, accessed November 9, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/bargain-hunting-after-drug-patent-expirations-a-contrarian-investment-strategy/

- The top 15 blockbuster patent expirations coming this decade – Fierce Pharma, accessed November 9, 2025, https://www.fiercepharma.com/special-report/top-15-blockbuster-patent-expirations-coming-decade

- 25 High-Value Drugs Losing Patent Protection in 2025: What It Means for Healthcare, accessed November 9, 2025, https://biopharmaapac.com/analysis/60/5727/25-high-value-drugs-losing-patent-protection-in-2025-what-it-means-for-healthcare.html

- An Analysis on leveraging the patent cliff with drug sales worth USD 251 billion going off-patent and analysis of different drug – Department of Pharmaceuticals, accessed November 9, 2025, https://pharma-dept.gov.in/sites/default/files/FINAL-An%20analysis%20on%20leveraging%20the%20patent%20cliff.pdf

- The Role of Patents and Regulatory Exclusivities in Drug Pricing | Congress.gov, accessed November 9, 2025, https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/R46679

- In the case of brand name drugs versus generics, patents can be …, accessed November 9, 2025, https://wvutoday.wvu.edu/stories/2022/12/19/in-the-case-of-brand-name-drugs-vs-generics-patents-can-be-bad-medicine-wvu-law-professor-says

- The Hatch-Waxman Act | Curtis, Mallet-Prevost, Colt & Mosle LLP, accessed November 9, 2025, https://www.curtis.com/glossary/intellectual-property/hatch-waxman-act

- Hatch-Waxman 101 – Fish & Richardson, accessed November 9, 2025, https://www.fr.com/insights/thought-leadership/blogs/hatch-waxman-101-3/

- Pfizer’s 180-Day War for Lipitor | PM360, accessed November 9, 2025, https://www.pm360online.com/pfizers-180-day-war-for-lipitor/

- Drug Patent Research: Expert Tips for Using the FDA Orange and Purple Books, accessed November 9, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/drug-patent-research-expert-tips-for-using-the-fda-orange-and-purple-books/

- Paucity of intellectual property rights information in the US biologics system a decade after passage of the Biosimilars Act – NIH, accessed November 9, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11081489/

- FAQs – FDA Purple Book, accessed November 9, 2025, https://purplebooksearch.fda.gov/faqs

- Revamped Purple Book Offers Greater Patent Transparency for Biologics – Morgan Lewis, accessed November 9, 2025, https://www.morganlewis.com/blogs/asprescribed/2021/05/revamped-purple-book-offers-greater-patent-transparency-for-biologics

- The Purple Book and The Orange Book – When do Patents Expire and Regulatory Exclusivities end for FDA Approved Products? | Insights & Resources | Goodwin, accessed November 9, 2025, https://www.goodwinlaw.com/en/insights/blogs/2020/09/the-purple-book-and-the-orange-book–when-do-paten

- 40 Years of Hatch-Waxman: How does the Hatch-Waxman Act help patients? | PhRMA, accessed November 9, 2025, https://phrma.org/blog/40-years-of-hatch-waxman-how-does-the-hatch-waxman-act-help-patients

- The Hatch-Waxman Act: A Primer – EveryCRSReport.com, accessed November 9, 2025, https://www.everycrsreport.com/reports/R44643.html

- 2025 U.S. Generic & Biosimilar Medicines Savings Report …, accessed November 9, 2025, https://accessiblemeds.org/resources/reports/2025-savings-report/

- Generic and Biosimilar Medicines Save $467 Billion in 2024, accessed November 9, 2025, https://biosimilarscouncil.org/news/generic-and-biosimilar-medicines-save-467-billion-in-2024/

- Guidance for Industry 180-Day Exclusivity When Multiple ANDAs Are Submitted on the Same Day – FDA, accessed November 9, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/files/drugs/published/180-Day-Exclusivity-When-Multiple-ANDAs-Are-Submitted-on-the-Same-Day.pdf

- Earning Exclusivity: Generic Drug Incentives and the Hatch …, accessed November 9, 2025, https://law.stanford.edu/index.php?webauth-document=publication/259458/doc/slspublic/ssrn-id1736822.pdf

- The Hatch-Waxman 180-Day Exclusivity Incentive Accelerates Patient Access to First Generics, accessed November 9, 2025, https://accessiblemeds.org/resources/fact-sheets/the-hatch-waxman-180-day-exclusivity-incentive-accelerates-patient-access-to-first-generics/

- Patent Certifications and Suitability Petitions – FDA, accessed November 9, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/abbreviated-new-drug-application-anda/patent-certifications-and-suitability-petitions

- What Every Pharma Executive Needs to Know About Paragraph IV Challenges, accessed November 9, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/what-every-pharma-executive-needs-to-know-about-paragraph-iv-challenges/

- Tips For Drafting Paragraph IV Notice Letters | Crowell & Moring LLP, accessed November 9, 2025, https://www.crowell.com/a/web/v44TR8jyG1KCHtJ5Xyv4CK/tips-for-drafting-paragraph-iv-notice-letters.pdf

- STRATEGIES FOR FILING SUCCESSFUL PARAGRAPH IV CERTIFICATIONS, accessed November 9, 2025, https://www.ssjr.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/presentations/lawyer_1/92706VA.pdf

- IPI Regulatory & Marketplace – Strategies Adopted by Branded Drug Manufacturers against Para IV Filers, accessed November 9, 2025, https://international-pharma.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Strategies-adopted-by-branded-drug.pdf

- Hatch-Waxman Overview | Axinn, Veltrop & Harkrider LLP, accessed November 9, 2025, https://www.axinn.com/en/insights/publications/hatch-waxman-overview

- Launch-at-Risk Analysis | Secretariat, accessed November 9, 2025, https://secretariat-intl.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/CaseStudy-Launch-at-Risk-Analysis-Draft.pdf

- NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES NO FREE LAUNCH: AT-RISK ENTRY BY GENERIC DRUG FIRMS Keith M. Drake Robert He Thomas McGuire Alice K. N, accessed November 9, 2025, https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w29131/w29131.pdf

- The Role of Litigation Data in Predicting Generic Drug Launches …, accessed November 9, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-role-of-litigation-data-in-predicting-generic-drug-launches/

- INTERCHANGEABLE BIOSIMILARS, accessed November 9, 2025, https://biosimilarscouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/22354-Focus-on-Interchangeable-Biosimilars.pdf

- Patent cliff and strategic switch: exploring strategic design possibilities in the pharmaceutical industry – PMC – NIH, accessed November 9, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4899342/

- Biologics and Biosimilars: Background and Key Issues – Congress.gov, accessed November 9, 2025, https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/R44620

- Understanding Interchangeable Biosimilars at the Federal and State Levels – AJMC, accessed November 9, 2025, https://www.ajmc.com/view/understanding-interchangeable-biosimilars-at-the-federal-and-state-levels

- Biosimilarity and Interchangeability in the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act of 2009 and FDA’s 2012 Draft Guidance for Industry – PMC – NIH, accessed November 9, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3827854/

- Patent Dance Insights: A Q&A on Reducing Legal Battles in the Biosimilar Landscape, accessed November 9, 2025, https://www.centerforbiosimilars.com/view/patent-dance-insights-a-q-a-on-reducing-legal-battles-in-the-biosimilar-landscape

- What’s Your Move? The Development of Patent Dance Jurisprudence After Sandoz and Its Practical Impacts – Food and Drug Law Institute, accessed November 9, 2025, https://www.fdli.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/10-Noh.pdf

- How Biosimilars Are Approved and Litigated: Patent Dance Timeline – Fish & Richardson, accessed November 9, 2025, https://www.fr.com/insights/ip-law-essentials/how-biosimilars-approved-litigated-patent-dance-timeline/

- What Is the Patent Dance? | Winston & Strawn Law Glossary, accessed November 9, 2025, https://www.winston.com/en/legal-glossary/patent-dance

- The Impact of Biosimilar Competition in Europe 2024 – IQVIA, accessed November 9, 2025, https://www.iqvia.com/library/white-papers/the-impact-of-biosimilar-competition-in-europe-2024

- The Impact of Biosimilar Competition in Europe – IQVIA, accessed November 9, 2025, https://www.iqvia.com/-/media/iqvia/pdfs/library/white-papers/the-impact-of-biosimilar-competition-in-europe-2024.pdf

- Rising Tide Lifts US Biosimilars Market | BCG, accessed November 9, 2025, https://www.bcg.com/publications/2024/rising-tide-lifts-us-biosimilars-market

- How Pharmaceutical Life Cycle Management Strategies Are Evolving – DrugPatentWatch, accessed November 9, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/how-pharmaceutical-life-cycle-management-strategies-are-evolving/

- Case Studies in Optimal Lifecycle Management – Syneos Health, accessed November 9, 2025, https://www.syneoshealth.com/insights-hub/lifecycle-management-series/case-studies-in-optimal-lifecycle-management

- Strategic Patenting by Pharmaceutical Companies – Should Competition Law Intervene? – PMC – NIH, accessed November 9, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7592140/

- Patent Database Exposes Pharma’s Pricey “Evergreen” Strategy – UC Law San Francisco, accessed November 9, 2025, https://www.uclawsf.edu/2020/09/24/patent-drug-database/

- The Global Patent Thicket: A Comparative Analysis of Pharmaceutical Monopoly Strategies in the U.S., Europe, and Emerging Markets – DrugPatentWatch, accessed November 9, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/how-do-patent-thickets-vary-across-different-countries/

- Humira Patent Expiration: What’s Next for its Biosimilars? – GreyB, accessed November 9, 2025, https://www.greyb.com/blog/humira-patent-expiration/

- Humira: The First $20 Billion Drug | AJMC, accessed November 9, 2025, https://www.ajmc.com/view/humira-the-first-20-billion-drug

- Can AbbVie’s legacy live beyond its once best-selling drug Humira? – Labiotech, accessed November 9, 2025, https://www.labiotech.eu/in-depth/abbvie-beyond-humira/

- The Arrival of Generic Imatinib Into the U.S. Market: An Educational Event – The ASCO Post, accessed November 9, 2025, https://ascopost.com/issues/may-25-2016/the-arrival-of-generic-imatinib-into-the-us-market-an-educational-event/

- How can pharmaceutical marketing evolve with generic entry? The …, accessed November 9, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/how-can-pharmaceutical-marketing-evolve-with-generic-entry-the-example-of-lipitor/

- Is Pfizer’s Lipitor Strategy Working? – Drug Channels, accessed November 9, 2025, https://www.drugchannels.net/2012/01/is-pfizers-lipitor-strategy-working.html

- “For Me There Is No Substitute”: Authenticity, Uniqueness, and the Lessons of Lipitor, accessed November 9, 2025, https://journalofethics.ama-assn.org/article/me-there-no-substitute-authenticity-uniqueness-and-lessons-lipitor/2010-10

- Pharmaceutical Switching | Stanford Graduate School of Business, accessed November 9, 2025, https://www.gsb.stanford.edu/faculty-research/case-studies/pharmaceutical-switching

- The RX-TO-OTC Switch of Claritin, Allegra, and Zyrtec: An Unprecedented FDA Response to Petitioner – Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of, accessed November 9, 2025, https://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=&httpsredir=1&article=1146&context=aulr

- When Rx-to-OTC Switch Medications Become Generic – U.S. Pharmacist, accessed November 9, 2025, https://www.uspharmacist.com/article/when-rx-to-otc-switch-medications-become-generic

- The effect of the Rx-to-OTC switch of loratadine and changes in prescription drug benefits on utilization and cost of therapy – PubMed, accessed November 9, 2025, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15974556/

- Paying for Delay: Pharmaceutical Patent Settlement as a Regulatory Design Problem, accessed November 9, 2025, https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/contract_economic_organization/11/

- Pay for Delay | Federal Trade Commission, accessed November 9, 2025, https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/topics/competition-enforcement/pay-delay

- Using Drug Patents to Block Competitors: The Tactics and Consequences, accessed November 9, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/using-drug-patents-to-block-competitors-the-tactics-and-consequences/

- Novartis settles Sun Pharma suit, winning 7-month reprieve from generic Gleevec, accessed November 9, 2025, https://www.fiercepharma.com/sales-and-marketing/novartis-settles-sun-pharma-suit-winning-7-month-reprieve-from-generic-gleevec

- CDRH Petitions – FDA, accessed November 9, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/about-fda/cdrh-foia-how-get-records-cdrh/cdrh-petitions

- Abuse of the FDA Citizen Petition Process: Ripe for Antitrust Challenge? – Wilson Sonsini, accessed November 9, 2025, https://www.wsgr.com/PDFSearch/silber0112.pdf

- Potential Implications of Inflation Reduction Act on Pharmaceutical Patent Litigation | Articles, accessed November 9, 2025, https://www.finnegan.com/en/insights/articles/potential-implications-of-inflation-reduction-act-on-pharmaceutical-patent-litigation.html

- The Impact of the Inflation Reduction Act on the Economic Lifecycle of a Pharmaceutical Brand – IQVIA, accessed November 9, 2025, https://www.iqvia.com/locations/united-states/blogs/2024/09/impact-of-the-inflation-reduction-act

- The Patent Cliff Playbook: A Strategic Guide for Payers to Optimize Cost and Coverage, accessed November 9, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-patent-cliff-playbook-a-strategic-guide-for-payers-to-optimize-cost-and-coverage/

- How the IRA is impacting the generic drug market | PhRMA, accessed November 9, 2025, https://phrma.org/blog/how-the-ira-is-impacting-the-generic-drug-market

- Understanding the Inflation Reduction Act’s Pill Penalty A technical fix is needed to ensure all patients continue to benefit fr, accessed November 9, 2025, https://cahc.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/Small-molecule-penalty-one-pager.pdf

- Reflections on the Inflation Reduction Act’s Pill Penalty | Brownstein, accessed November 9, 2025, https://www.bhfs.com/insight/reflections-on-the-inflation-reduction-act-s-pill-penalty/

- Explaining the Prescription Drug Provisions in the Inflation Reduction Act – KFF, accessed November 9, 2025, https://www.kff.org/medicare/explaining-the-prescription-drug-provisions-in-the-inflation-reduction-act/

- Study reveals the Inflation Reduction Act’s ‘pill penalty’ is reducing …, accessed November 9, 2025, https://becarispublishing.com/digital-content/blog-post/study-reveals-inflation-reduction-act-s-pill-penalty-reducing-investment-small-molecule

- Cryptic Patent Reform Through the Inflation Reduction Act, accessed November 9, 2025, https://repository.law.umich.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1366&context=law_econ_current

- Role of Competitive Intelligence in Pharma and Healthcare Sector – DelveInsight, accessed November 9, 2025, https://www.delveinsight.com/blog/competitive-intelligence-in-healthcare-sector

- Patent Analytics in Competitive Intelligence: A Deep Dive – PATOffice, accessed November 9, 2025, https://www.patoffice.de/en/blog/patent-analytics-competitive-intelligence

- You Don’t Need to Win the Patent — You Need to Win the Market: What No One Tells You About Winning Drug Patent Challenges – DrugPatentWatch – Transform Data into Market Domination, accessed November 9, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/you-dont-need-to-win-the-patent-you-need-to-win-the-market-what-no-one-tells-you-about-winning-drug-patent-challenges/

- Real World Blockchain Uses in the Pharmaceutical Industry – DrugPatentWatch, accessed November 9, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/real-world-blockchain-uses-in-the-pharmaceutical-industry/

- DrugPatentWatch | Software Reviews & Alternatives – Crozdesk, accessed November 9, 2025, https://crozdesk.com/software/drugpatentwatch

- Patent Analytics for competitive intelligence in the pharmaceutical industry – Intelacia, accessed November 9, 2025, https://intelacia.com/patent-analytics-for-competitive-intelligence-in-the-pharmaceutical-industry/

- Pharmaceutical Competitive Intelligence | 2025 Guide – BiopharmaVantage, accessed November 9, 2025, https://www.biopharmavantage.com/competitive-intelligence

- Using DrugPatentWatch to Support Out-Licensing and Partnering …, accessed November 9, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/using-drugpatentwatch-to-support-out-licensing-and-partnering-decisions/