I. Executive Summary

The landscape of drug lifecycle management is fundamentally shaped by the intricate and evolving nature of patent claims. Historically, patent protection primarily focused on novel chemical compounds, granting innovators a period of exclusivity to recoup significant research and development investments. Over time, this foundational approach has diversified into a complex web of claims, encompassing formulations, methods of use, manufacturing processes, and even delivery devices. This strategic expansion aims to extend market exclusivity, a critical objective given the substantial costs and lengthy timelines associated with drug development and regulatory approval.

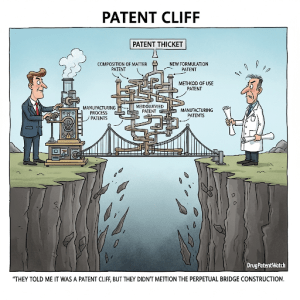

The evolution of patent claims is particularly evident in the post-Hatch-Waxman era, which, while designed to balance innovation with generic drug access, inadvertently catalyzed a sophisticated ecosystem of patent litigation. This environment has led to the rise of “patent thickets” and “evergreening” strategies, where numerous overlapping patents are deployed to deter generic and biosimilar competition. This practice, while legally permissible, intensifies the tension between incentivizing pharmaceutical innovation and ensuring affordable access to essential medicines.

Looking ahead, emerging technologies such as personalized medicine, gene therapies, and artificial intelligence are poised to further transform patent strategies. These advancements introduce new challenges, particularly concerning patent eligibility for biological materials and the attribution of inventorship in AI-driven discoveries. Concurrently, they present novel opportunities for protection through highly specific claims related to diagnostic methods, delivery systems, and AI-optimized processes. Navigating these complexities demands a proactive and integrated intellectual property strategy that leverages advanced analytics and adapts to the nuanced global legal frameworks, ultimately defining success in the pharmaceutical industry for decades to come.

II. Introduction: The Indispensable Role of Patent Claims in Pharmaceutical Innovation

Setting the Stage for Patent Centrality

Pharmaceutical innovation stands as a cornerstone of modern healthcare, yet it is an endeavor fraught with substantial financial risk and protracted timelines. The journey from initial discovery to market availability for a new drug typically spans 10 to 15 years, with research and development (R&D) costs often soaring into the billions of dollars.1 In this high-stakes environment, patents transcend their conventional role as mere legal instruments; they emerge as indispensable business assets. These exclusive rights grant a temporary monopoly, enabling pharmaceutical companies to safeguard their colossal investments and generate the revenue necessary to fuel future research and development.1 This period of market exclusivity is paramount, directly influencing a drug’s market position, attracting vital investor capital, and underpinning long-term revenue streams.6 Without robust patent protection, the economic viability of pioneering new therapies would be severely compromised, potentially stifling the very innovation that drives medical progress.

Brief Overview of the Drug Lifecycle and its Patent Intersections

The lifecycle of a pharmaceutical product is a multi-stage process, commencing with discovery and development, progressing through preclinical and clinical research, undergoing rigorous regulatory review, and culminating in market launch and post-market surveillance.12 Each of these distinct stages presents unique opportunities and formidable challenges for securing and defending intellectual property. The strategic decisions made regarding patenting at every juncture profoundly influence a drug’s commercial success and its eventual accessibility to patients.

A fundamental challenge inherent in pharmaceutical patenting stems from the disparity between the statutory patent term and the actual period of market exclusivity. A standard patent typically grants protection for 20 years from its filing date.1 However, the extensive duration required for drug development and regulatory approval, which can consume an average of 10 to 15 years from the initial patent filing to market entry, significantly erodes this 20-year period.1 This means that by the time a drug reaches patients, its effective market exclusivity may be reduced to approximately 7 to 8 years.1 This inherent delay creates a critical strategic imperative for pharmaceutical companies: to devise and implement various mechanisms to maximize the remaining patent life once a drug is approved and commercialized. The need to compensate for the “lost” patent years during development becomes a primary driver for many advanced patent strategies, such as seeking patent term extensions or developing secondary patents, all with the objective of recouping the immense R&D investments.

III. Foundational Concepts of Pharmaceutical Patent Claims

Defining Patent Claims: Scope and Purpose

A patent serves as an exclusive right granted for an invention, empowering its owner to prevent others from manufacturing, using, selling, offering for sale, or importing the patented invention for a finite duration, typically 20 years from the original filing date.1 It is crucial to recognize that this right is geographically limited; a patent issued by the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) is enforceable only within the United States, while a European Patent Office (EPO) patent is valid solely in its participating member states.15 At the very heart of any patent lies its claims, which are the precise legal statements that delineate the boundaries and scope of the invention sought to be protected.16 These claims are paramount, as they define what constitutes an infringement and thus the commercial value of the patent.

Effective claim drafting necessitates a delicate balance between providing sufficient detail and maintaining broad applicability. Patent attorneys often prioritize capturing the “broadest embodiment of the invention” rather than becoming overly engrossed in minute specifics.17 This approach, often analogized to seeing the “forest for the trees,” is strategically vital. Overly narrow claims, while potentially easier to secure, offer limited commercial utility because they can be readily circumvented by competitors through minor modifications that fall outside the precisely defined scope. Therefore, the strategic objective in drafting is to formulate claims that are expansive enough to cover foreseeable variations and future advancements, thereby “blocking competitors from designing around your patent”.17 This foundational principle profoundly influences the selection of claim types and the specific language employed throughout the patent application.

Structure of a Patent Claim: Preamble, Body, and Transitional Phrases

A patent claim is typically structured into two primary components: the preamble and the body.16 The preamble serves as an introduction, setting the context for the invention, while the body meticulously defines the invention’s features and limitations.16 The clarity and conciseness of this structure are paramount to prevent ambiguity and ensure the claim’s enforceability in legal proceedings.16

Within the claim structure, transitional phrases play a critical role in precisely defining the scope of what additional, unrecited components or steps, if any, are included or excluded from the claim.18 The interpretation of these phrases is often highly fact-dependent and determined on a case-by-case basis.

- “Comprising”: This is an inclusive, or “open-ended,” transitional term, akin to “including” or “containing”.18 Its use signifies that while the named elements are essential, the claim does not preclude the presence of other, unrecited elements or method steps. For instance, a claim describing a composition “comprising” elements A, B, and C would cover a composition containing A, B, C, and D. This phrase is generally favored when seeking broader protection, as it allows for flexibility and future improvements without necessarily narrowing the claim’s scope.

- “Consisting of”: In contrast, “consisting of” is a “closed” term, explicitly excluding any element, step, or ingredient not specifically enumerated in the claim.18 For example, a claim for a kit “consisting of” chemicals X and Y would typically not be infringed by a kit containing X, Y, and Z. This phrase is often employed in Markush claims to define a finite, closed group of alternatives.19 While it provides precise boundaries, it can make a patent more susceptible to circumvention if a competitor introduces a non-essential element not explicitly listed.

- “Consisting essentially of”: This phrase occupies an intermediate position between “comprising” and “consisting of”.18 It limits the claim’s scope to the specified materials or steps while permitting the inclusion of additional elements or steps that do not

materially affect the fundamental and novel characteristics of the claimed invention.18 The interpretation of this phrase heavily relies on a clear and precise definition of what constitutes the “basic and novel characteristics” within the patent specification.19

The selection of a single transitional word, such as “comprising” versus “consisting of,” carries profound implications for the scope of patent protection and its susceptibility to infringement or invalidation. The open-ended “comprising” offers flexibility, potentially covering future improvements or minor variations in formulations or delivery methods. Conversely, a precisely defined “consisting of” claim, if not meticulously drafted, can be easily circumvented if a competitor introduces an element not explicitly listed, even if that element is non-essential to the core invention. The inherent ambiguity of “consisting essentially of” further underscores the critical need for clear definitions and robust supporting data within the patent specification to precisely delineate the “material effect” and withstand potential legal challenges. For pharmaceutical companies, operating in an industry characterized by incremental innovation and aggressive “design-around” strategies, the careful choice of this transitional language is a fundamental strategic decision, directly impacting the breadth and defensibility of their intellectual property.

Types of Pharmaceutical Patent Claims

Pharmaceutical products are rarely protected by a singular patent. Instead, companies strategically construct a “multi-layered web of protection” or a “patent thicket” utilizing a diverse array of claim types.1 This comprehensive approach is designed to create formidable barriers against generic competition and extend market exclusivity.

- Product/Composition of Matter Patents: These are widely regarded as the “crown jewels” of pharmaceutical intellectual property.7 They are foundational, directly covering the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) itself.1 These patents grant exclusive rights to the core chemical compound, effectively preventing any other entity from manufacturing, using, or selling it.7 The novel drug can be claimed either by its specific chemical name, its unique chemical structure, or broadly within a Markush structure.20 A notable example includes empagliflozin (marketed as Jardiance®), which is protected by patents covering both the compound and its specific crystalline forms.22

- Process Patents: These claims are designed to protect the specific methods employed in producing a pharmaceutical product, including innovative manufacturing procedures or chemical synthesis steps.1 They are crucial for safeguarding exclusive production methods that may enhance efficiency, purity, or effectiveness. An illustrative example would be a patent claiming “an antibiotic obtained by growing a certain mold on culture media and purifying an extract,” where the protection lies in the unique process of its creation.23

- Method of Use Patents: These patents protect specific applications or uses of a known product, including the discovery of new therapeutic uses for existing drugs.1 Such patents incentivize the repurposing and optimization of existing pharmaceutical products, thereby contributing to improved healthcare outcomes.8 For instance, Pfizer’s Viagra, initially developed for cardiovascular issues, later secured method-of-use patents for erectile dysfunction.10 Similarly, a drug initially approved for one condition might later be patented for treating a different disease, such as finasteride for baldness or bupropion for smoking cessation.1

- Formulation Patents: These claims safeguard the unique combination of ingredients within a drug, including specialized carriers, delivery mechanisms, or packaging designed to optimize the drug’s performance, enhance efficacy, improve patient compliance, or increase stability.1 Examples include time-release capsules 8, extended-release versions like AstraZeneca’s Seroquel XR or Bristol-Myers Squibb’s Glucophage XR 1, and specific topical gels such as diclofenac formulations.26

- Combination Patents: These patents are tailored for drugs that integrate multiple active ingredients to create a novel therapeutic approach.8 They secure protection for innovative treatments that rely on synergistic effects to manage complex ailments, often seen in multi-faceted therapeutic interventions like those for HIV/AIDS or cancer.8

- Product-by-Process Claims: This specialized claim type defines a product by the process through which it is manufactured.23 Such claims are typically employed when the product’s precise structure is not yet fully elucidated or is inherently challenging to define independently of its production method.23 Critically, the patentability of such a claim rests on the novelty and non-obviousness of the

product itself, rather than solely on the process used to create it.28 A pharmaceutical company, for example, might patent a drug by describing the novel process that yields its unique formulation.29 - Markush Claims: Named after the inventor Eugene Markush, these claims enable a broader scope of protection by encompassing a diverse group of potential chemical compounds or variations.20 They describe a core chemical structure with various optional substituents, allowing the inventor to claim a “genus” of compounds rather than just a single “species”.20 A common format is: “A compound of the formula wherein R1 is selected from the group consisting of”.31 These are extensively used in chemistry and pharmaceuticals due to the vast number of potential molecular variations.

The evolution of pharmaceutical patent claims underscores a significant strategic pivot within the industry. What began as a reliance on broad “composition of matter” patents, protecting the fundamental active ingredient, has transformed into a sophisticated strategy of building expansive, multi-layered intellectual property portfolios. This “web of protection” 1 is a direct and calculated response to the relentless pressures of generic competition and the commercial imperative to extend market exclusivity well beyond the lifespan of the initial primary patent. By strategically layering patents on various aspects—such as novel formulations, new methods of use, refined manufacturing processes, or even specific crystalline forms (polymorphs)—companies construct substantial barriers to generic market entry, thereby prolonging their period of market exclusivity.34 This shift from a singular focus on the core compound to a comprehensive portfolio approach represents a pivotal evolutionary step in modern drug lifecycle management, driven by the need to maximize return on the immense R&D investments and secure a competitive edge.

Table 1: Key Types of Pharmaceutical Patent Claims

| Patent Type | What it Protects | Strategic Importance |

| Product/Composition of Matter | Active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) itself; core chemical compound. | Broadest protection; initial cornerstone of market exclusivity. |

| Process | Method of producing a pharmaceutical product; innovative manufacturing procedures. | Enhances efficiency and effectiveness of production; creates proprietary methods. |

| Method of Use | Specific uses of a known product; new therapeutic applications. | Encourages repurposing; expands market potential for existing drugs. |

| Formulation | Unique combination of ingredients, carriers, delivery mechanisms, or packaging. | Optimizes drug performance, efficacy, patient compliance, and stability; extends exclusivity. |

| Combination | Drugs combining multiple active ingredients for new therapies. | Protects synergistic approaches to complex diseases. |

| Product-by-Process | A product defined by its manufacturing process, used when structure is hard to define. | Protects complex products where structural definition is challenging; scope based on product itself. |

| Markush | A group of related chemical compounds sharing a common core structure but differing in substituents. | Allows broad chemical coverage for a genus of compounds; prevents easy design-arounds. |

IV. Historical Evolution of Pharmaceutical Patent Law

Early Patenting Landscape (Pre-WWII to Pre-Hatch-Waxman)

The journey of pharmaceutical patenting is deeply intertwined with societal views on public health and the evolving understanding of intellectual property. In earlier periods, medicines were frequently deemed too vital to be monopolized, and consequently, robust patent protection for them was often absent across many jurisdictions.34 The very concept of patents has ancient roots, tracing back to the Venetian Statute of 1474.35 Initially, patents predominantly focused on protecting novel processes and techniques, a scope that included methods for producing medicines.37 In England, the Statute of Monopolies of 1624 laid the fundamental groundwork for what would become modern patent law.36 Across the Atlantic, the early U.S. Patent Acts of 1790, 1793, and 1836 established core patentability criteria such as usefulness, novelty, and non-obviousness.15 For chemical compounds, direct product patentability remained a challenge for a considerable time, with protection often limited to the specific

process by which they were made.41

Several landmark court decisions significantly shaped the contours of patentability during this era:

- Hotchkiss v. Greenwood (1850) was a pivotal U.S. Supreme Court case that introduced the crucial concept of non-obviousness into U.S. patent law, requiring an invention to be more than a mere mechanical improvement.39

- O’Reilly v. Morse (1853) had a lasting impact on patent eligibility, notably invalidating method claims that were deemed “abstract ideas” not intrinsically tied to a particular machine or practical application.42

- A major turning point in U.S. biotechnology patent law was Diamond v. Chakrabarty (1980). In this landmark decision, the U.S. Supreme Court affirmed the patentability of a live, human-made microorganism, famously declaring that “anything under the sun that is made by man” is eligible for patenting.43 This ruling effectively opened the floodgates for the patenting of biotechnology-related inventions.

- In Europe, the adoption of the European Patent Convention (EPC) in 1973 (which came into force in 1977) marked a significant stride towards harmonization of patent laws across member states.36 Critically, the EPC allowed for the protection of chemical compounds

per se, a notable departure from earlier national laws that often restricted protection to manufacturing processes.41

Prior to the enactment of the Hatch-Waxman Act in 1984, generic drug manufacturers faced substantial impediments to market entry. Existing U.S. law generally prohibited generic competitors from conducting the necessary tests for FDA approval using patented methods until the underlying patents had expired.48 This legal constraint effectively prolonged the market exclusivity of brand-name drugs for several years beyond their primary patent expiration dates.49 The

Roche v. Bolar case in 1984 vividly illustrated this dilemma, where a generic company was sued for patent infringement merely for using a patented compound to conduct FDA-mandated bioequivalence testing in preparation for market entry.51

The historical trajectory of pharmaceutical patent law reveals a gradual but decisive shift from an initial reluctance to grant patents on medicines, often viewing them as public goods, towards a robust system that directly protects chemical compounds and their diverse applications. This evolution reflects the increasing industrialization of drug discovery and the burgeoning recognition of the immense R&D costs involved.34 Moving beyond mere process patents to directly protecting the final product—the chemical compound itself—provided a far stronger incentive for innovation by securing broader and more enforceable market exclusivity. The

Roche v. Bolar case 51 served as a critical catalyst, starkly highlighting the need for a legislative solution that could balance the imperative to incentivize pharmaceutical innovation with the public’s desire for timely access to more affordable generic medicines. This judicial challenge directly paved the way for the comprehensive reforms embodied in the Hatch-Waxman Act.

The Transformative Impact of the Hatch-Waxman Act (1984)

The Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984, universally known as the Hatch-Waxman Act, represents a watershed moment in U.S. pharmaceutical regulation. Its core objective was to forge a delicate equilibrium: stimulating pharmaceutical innovation by safeguarding intellectual property rights while simultaneously fostering competition by promoting the timely entry of affordable generic drugs.34

The Act introduced several key provisions that fundamentally reshaped the pharmaceutical landscape:

- Patent Term Restoration (PTR): Recognizing the protracted nature of drug development and regulatory review, Hatch-Waxman allowed pharmaceutical companies to extend the term of their patents to compensate for time lost during the FDA approval process.34 This provision aimed to ensure that innovators had a commercially viable period of exclusivity to recoup their substantial R&D investments.

- Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA): This groundbreaking pathway streamlined the approval process for generic drugs. Generic manufacturers could now gain approval by demonstrating bioequivalence to a previously approved Reference Listed Drug (RLD) without needing to repeat costly and time-consuming animal and human clinical trials.34 This significantly reduced the barriers to generic market entry.

- “Safe Harbor” Provision (35 U.S.C. § 271(e)(1)): Directly addressing the Roche v. Bolar dilemma, this provision explicitly exempted generic manufacturers from patent infringement liability for activities conducted solely to generate information required for FDA approval, even if those activities occurred before the patent’s expiration.38

- Orange Book Listing: The Act mandated that brand-name drug manufacturers list all patents covering their approved drugs in the FDA’s “Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations,” commonly known as the Orange Book.34 This provided crucial transparency for generic manufacturers seeking to identify expiring patents or challenge existing ones.

- Paragraph IV Certification: Generic applicants gained the ability to challenge the validity or infringement of Orange Book-listed patents by filing a “Paragraph IV certification” within their ANDA submission.38 This certification asserts that the patent is either invalid or will not be infringed by the generic product.

- 180-Day Market Exclusivity: A powerful incentive for generic challenges, this provision awarded 180 days of exclusive marketing rights to the first generic manufacturer to file a Paragraph IV certification and successfully challenge a patent.48 This temporary monopoly provided a significant commercial advantage to the pioneering generic.

- 30-Month Stay: To protect innovators, if a brand-name company sued the generic applicant for patent infringement within 45 days of receiving a Paragraph IV notice, FDA approval of the ANDA was generally stayed for 30 months.48 This period allowed time for the patent litigation to proceed, preventing immediate generic entry.

While the Hatch-Waxman Act was designed to balance competing interests, its mechanisms inadvertently catalyzed a sophisticated legal and commercial ecosystem centered around patent litigation. The incentives embedded within the Act, particularly the 180-day exclusivity for the first Paragraph IV filer and the 30-month stay for the innovator, transformed patent challenges from a mere legal defense into a high-stakes strategic play for both brand-name and generic pharmaceutical companies. This framework directly led to a significant increase in both generic drug penetration and the volume of patent litigation.48 The 180-day exclusivity, while intended to accelerate generic entry, often prompts a “race to the bottom” among generic manufacturers to be the first to file, which then triggers the 30-month litigation stay. This means that even when a generic product is ready for market, its entry can be legally blocked for a substantial period, often benefiting the innovator. This inherent paradox within the Hatch-Waxman framework has been a key point of criticism, as it can lead to controversial “pay-for-delay” settlements where brand-name companies compensate generic manufacturers to postpone their market entry.48 Consequently, the Act did not merely regulate; it fundamentally reshaped the competitive dynamic, making legal strategy as critical as scientific innovation in the pharmaceutical marketplace.

Post-Hatch-Waxman Era: The Rise of Secondary Patents, Patent Thickets, and Evergreening

The post-Hatch-Waxman era witnessed a profound adaptation in pharmaceutical patent strategies. As the industry grappled with the implications of streamlined generic entry, companies increasingly turned to “secondary patents” to protect aspects of a drug beyond its initial active ingredient.1 These patents cover a diverse range of innovations, including new formulations, specific dosage forms, novel methods of use, refined manufacturing processes, and different crystalline forms (polymorphs) of the active compound.34 The overarching strategic objective behind this proliferation of secondary patents is to extend market exclusivity well beyond the expiration of the primary compound patent.34

This increased reliance on secondary patents has led to the emergence of “patent thickets”—dense, overlapping networks of intellectual property rights surrounding a single drug product.7 These thickets are strategically constructed to make it exceptionally challenging and costly for generic manufacturers to enter the market.63 A prominent example is AbbVie’s Humira, for which the company amassed over 100 patents, including those related to manufacturing, formulation, and administration, effectively delaying biosimilar entry in the U.S. until 2023, years after biosimilars had entered the European market.65 Challenging such a multitude of patents can cost generic companies millions of dollars and involve protracted legal battles.63

Closely related to patent thickets is the controversial practice of “evergreening”.1 This strategy involves extending drug patent protection through incremental modifications or new applications of existing compounds, often without introducing significant therapeutic advancements.1 Common tactics include patenting new formulations (e.g., extended-release versions), novel delivery methods, combination drugs, or new uses for existing drugs.1 The FDA’s Orange Book, initially listing primarily compound patents, evolved to include these formulation, method-of-use, and other secondary patents, reflecting these strategic shifts.34

The post-Hatch-Waxman era has been characterized by a strategic “arms race” in intellectual property protection. Brand-name pharmaceutical companies have adeptly leveraged the inherent flexibility of patent law to prolong their market exclusivity. This proactive and often aggressive deployment of secondary patents and the creation of patent thickets, while operating within legal boundaries, has fundamentally reshaped the competitive landscape. The battleground has shifted from solely scientific innovation to include intricate legal maneuvering. This dynamic is driven by the economic pressure arising from impending generic competition 14, which incentivizes brand-name companies to find legal avenues to extend their monopolies. Secondary patents and thickets have become primary tools for achieving this “monopoly extension”.65 This has led to a system where companies invest heavily not only in developing new drugs but also in cultivating extensive patent portfolios around existing ones. This “strategic arms race” results in increased litigation costs for both innovators and generics 63 and fuels ongoing public policy debates regarding drug pricing and patient access.5

Table 2: Major Milestones in US Pharmaceutical Patent Law

| Year | Milestone/Event | Description/Impact |

| 1850 | Hotchkiss v. Greenwood | Introduced the concept of non-obviousness as a patentability requirement in U.S. patent law.39 |

| 1853 | O’Reilly v. Morse | Influential decision invalidating method claims for “abstract ideas” not tied to a particular machine, shaping patent eligibility.42 |

| 1980 | Diamond v. Chakrabarty | U.S. Supreme Court held a live, man-made microorganism patentable, asserting “anything under the sun that is made by man” is eligible for patenting, opening biotechnology patenting.43 |

| 1984 | Roche v. Bolar | Highlighted the issue of generic companies being sued for patent infringement for pre-expiration testing for FDA approval, leading directly to the Hatch-Waxman Act.51 |

| 1984 | Hatch-Waxman Act (Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act) | Landmark legislation balancing innovation incentives (Patent Term Restoration) with generic drug access (ANDA, Safe Harbor, 180-day exclusivity, Orange Book).34 |

V. Strategic Patenting Across the Drug Lifecycle

The strategic deployment and management of patent claims are integral to every phase of a drug’s lifecycle, from its nascent discovery to its eventual post-market exclusivity.

Drug Discovery and Early Development (Preclinical)

The initial phase of drug discovery and early development, encompassing preclinical research, is where the foundational intellectual property is first identified and protected.12 Patenting efforts at this stage primarily focus on novel molecules, identifying new drug targets, and developing innovative methods of synthesis or screening.77 The core protection typically sought involves Composition of Matter patents for the active compounds, alongside initial methods of use.1

The timing of these initial patent filings is a critical strategic consideration. Companies frequently file provisional patent applications early in the process to secure a priority date.1 This allows them to continue refining the invention for up to 12 months while maintaining their place in the “first-to-file” system, which is globally recognized as crucial for patent priority.10 However, a delicate balance must be struck: delaying the formal patent filing until later stages of development can theoretically extend the effective patent term once the drug reaches the market. Yet, this approach carries the inherent risk of preemption by competitors or unintended public disclosure of the invention, which could invalidate future patent claims.10

Prior to filing, a thorough patent landscape analysis is indispensable. This involves meticulously examining existing patents, scientific literature, and competitor activities to identify both opportunities (such as unprotected compounds or underserved therapeutic areas) and potential risks (like infringement issues or expiring competitor patents).10 Such an analysis not only informs the direction of R&D but also helps in crafting claims that effectively “block competitors from designing around” the new invention.17

Innovators in drug discovery face a complex challenge: how to balance the need for early disclosure to secure a priority date and broad claims with the desire to preserve patent life for market exclusivity. The standard 20-year patent term begins upon filing, meaning that the extensive time spent in R&D and regulatory review directly reduces the period of effective market exclusivity.1 This creates a clear trade-off: filing too early risks the patent expiring before the drug is fully commercialized, while delaying filing to maximize market life risks a competitor filing first or the invention becoming public knowledge. The provisional patent system offers a tactical solution to this tension. It provides a low-cost, temporary placeholder for 12 months, allowing companies to stake their claim and secure a priority date without immediately starting the 20-year patent clock.1 This strategic maneuver grants valuable time to further develop and optimize the invention, gather additional data, and refine the patent application, thereby mitigating the risks associated with both premature disclosure and delayed protection.

Clinical Trials and Regulatory Approval

As a drug candidate progresses into clinical trials, the strategic focus of patenting expands significantly. Clinical trials frequently unveil new patentable inventions beyond the initial compound, such as novel formulations, optimized methods of administration, precise dosage regimens, or entirely new indications for an existing drug.1 These “secondary patents” are pivotal for extending market exclusivity and fortifying the drug’s intellectual property portfolio.7 Examples include the development of extended-release formulations like AstraZeneca’s Seroquel XR or Bristol-Myers Squibb’s Glucophage XR 1, new routes of administration such as intranasal delivery for migraine treatments 1, or the discovery of new therapeutic uses for existing compounds, as seen with finasteride for baldness or bupropion for smoking cessation.7

However, clinical trials inherently involve the generation and, at times, public disclosure of data, including protocols and results.82 This public dissemination can inadvertently create “prior art” that may undermine the novelty or non-obviousness of later-filed patent claims. To mitigate this risk, companies employ strategies such as strict confidentiality agreements with investigators and careful timing of data publications.82

The Hatch-Waxman Act introduced mechanisms for extending patent life to compensate for the lengthy regulatory review process. Patent Term Extensions (PTEs) are granted to offset delays incurred during FDA approval 34, while Patent Term Adjustments (PTAs) account for delays in patent prosecution at the USPTO.34 Additionally, pediatric exclusivity offers an extra six months of market protection for drugs for which pediatric studies are conducted.34

The intersection of regulatory processes and patent strategy is critical. Patents play a significant role in attracting the necessary investment to fund costly clinical trials.3 Therefore, aligning patent filing strategies with key regulatory milestones, such as Investigational New Drug (IND) applications and New Drug Application (NDA) or Biologics License Application (BLA) submissions, is crucial for maximizing the period of market exclusivity.1

Clinical trial data, while indispensable for demonstrating a drug’s utility and efficacy for regulatory approval and for strengthening patent claims, simultaneously presents a significant challenge: its public disclosure can inadvertently create prior art that undermines the novelty or non-obviousness of later-filed patents.86 This creates a complex situation for innovators. Prior art, which includes any publicly available information before a patent application is filed, can invalidate a patent if the claimed invention is no longer considered new or is rendered obvious in light of that information.15 This inherent tension necessitates a delicate balancing act for pharmaceutical companies. They must generate sufficient clinical data to robustly support their patent claims and secure regulatory approval, while simultaneously protecting that data from becoming publicly accessible before the necessary patent applications are filed. This strategic imperative involves careful timing of patent filings—for instance, delaying until strong Phase II or III data is available but ensuring filing occurs before widespread public dissemination.82 It also requires the rigorous use of confidentiality agreements with all parties involved in clinical trials 82 and the meticulous crafting of claims that protect aspects of the invention not publicly disclosed, such as specific chemical structures or formulation ingredients.87 The requirement for “sufficient disclosure” within the patent application itself further complicates this balance, as some data must be included to enable others skilled in the art to practice the invention.15

Market Launch and Post-Market Exclusivity

Upon successful regulatory approval, the focus shifts to strategic market launch and the meticulous management of post-market exclusivity. Patents are not merely legal protections at this stage; they become powerful marketing tools. Leveraging patents as selling points enhances a brand’s value and serves as a key differentiator in a competitive market.79 A comprehensive intellectual property strategy, encompassing both utility patents for functional features and design patents for aesthetic elements, is crucial for holistic product protection.79 Furthermore, filing patents prior to any public disclosure is paramount to preserve potential foreign patent rights, as many jurisdictions lack the grace periods found in U.S. law.79

As a drug approaches its primary patent expiration, pharmaceutical companies deploy a range of defensive strategies to mitigate the impact of generic entry:

- Patent Thickets and Evergreening: Companies continue to build and enforce patent thickets through the strategic filing of secondary patents—covering formulations, methods of use, polymorphs, and manufacturing processes—to deter generic competition and prolong market exclusivity.5

- Patent Term Extensions: Mechanisms like PTEs, PTAs, and pediatric exclusivity are actively utilized to extend the period of patent protection, compensating for regulatory and prosecution delays.34

- Product-Line Extensions: A common strategy involves developing and launching improved versions of existing products, such as extended-release formulations, new indications, or combination drugs. The aim is to encourage patients and prescribers to switch to the new, still-patented product before the original drug loses exclusivity.14

The expiration of pharmaceutical patents marks a significant inflection point, often referred to as a “patent cliff,” triggering a “seismic shift” in the market.14 Generic competition rapidly enters, leading to dramatic declines in revenue for the innovator company.14 Strategies to manage this loss of exclusivity (LOE) include adjusting market access and pricing strategies, or even transitioning the product to over-the-counter (OTC) status.14

The post-market phase fundamentally transforms patent strategy into a continuous and often aggressive battle for market share. The concept of “evergreening” 1 is a direct manifestation of this commercial imperative, where pharmaceutical companies strive to create a perpetual cycle of patent protection. This is often achieved not necessarily through revolutionary breakthroughs, but through incremental improvements that can be patented, such as new formulations, delivery methods, or additional indications.1 This practice highlights a tension between the original intent of patent law—to incentivize truly novel inventions—and its commercial application in maintaining market monopolies. The economic pressure to sustain profitability and recoup massive R&D investments 1 drives companies to seek continuous, even minor, patent protection. While legally permissible, this strategy is frequently criticized for unduly extending monopolies without a commensurate increase in therapeutic benefit, thereby contributing to persistently high drug prices and limiting patient access to more affordable medicines.5 Consequently, the strategic goal in this phase shifts from simply protecting a single invention to managing an entire portfolio of patents designed for sustained revenue generation and competitive deterrence.

Table 3: Strategic Patenting Activities by Drug Lifecycle Stage

| Drug Lifecycle Stage | Key Patenting Activities |

| Discovery & Early Development | File provisional patents for core compounds, initial methods of use, and key intermediates; conduct thorough patent landscape analysis to identify opportunities and risks; meticulous documentation of R&D. |

| Preclinical Research | Continue refining claims based on preclinical data; file secondary patents for new formulations, polymorphs, or manufacturing processes; ensure robust data to support claims. |

| Clinical Trials | Patent new formulations, methods of administration, specific dosage regimens, or new indications discovered during trials; manage public disclosure risks of clinical data through confidentiality agreements and strategic timing of publications. |

| Regulatory Approval | Pursue Patent Term Extensions (PTEs) and Patent Term Adjustments (PTAs) to compensate for regulatory delays; align patent filing strategies with regulatory milestones (e.g., IND, NDA/BLA submissions); seek pediatric exclusivity. |

| Market Launch | Leverage patents as selling points for product differentiation and brand value; ensure comprehensive IP strategy including utility and design patents; file foreign patent applications before public disclosure. |

| Post-Market Exclusivity | Continue to build and enforce patent thickets through secondary patents (formulations, methods of use, polymorphs, manufacturing processes) to deter generics; utilize evergreening strategies; manage loss of exclusivity (LOE) through product-line extensions, market access adjustments, or OTC switches. |

Table 4: Key Patent and Regulatory Exclusivities (US, EU, Japan)

| Protection Type | US Duration/Conditions | EU Duration/Conditions | Japan Duration/Conditions |

| Standard Patent Term | 20 years from filing date | 20 years from filing date | 20 years from filing date |

| Patent Term Extension (PTE)/Supplementary Protection Certificate (SPC) | Up to 5 years (compensates for FDA review time) 55 | Up to 5 years (SPC) plus 6 months for pediatric uses 55 | Up to 5 years (compensates for regulatory approval delays) 80 |

| New Chemical Entity (NCE) Exclusivity/Regulatory Data Protection (RDP) | 5 years (for new active moieties) 55 | 8 years (data protection) + 2 years (market exclusivity), extendable to 11 years with new indication 80 | 8-10 years (data exclusivity) 80 |

| Orphan Drug Exclusivity (ODE)/Orphan Market Exclusivity (OME) | 7 years (for drugs treating rare diseases) 55 | 10 years (for orphan medicinal products) 80 | Up to 10 years 80 |

| Pediatric Exclusivity | Adds 6 months to existing patents/exclusivities 55 | Adds 6 months to existing exclusivity 55 | No specific provision 80 |

| Biologics Exclusivity | 12 years of market exclusivity for reference products 80 | Covered by data/market exclusivity (8+2+1 regime) 80 | 8 years data exclusivity 80 |

VI. Impact on Generic and Biosimilar Competition

The Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) Pathway and Patent Challenges

The Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) pathway, a cornerstone of the Hatch-Waxman Act, revolutionized the generic drug industry. It permits generic drugs to gain regulatory approval based on demonstrated bioequivalence to a Reference Listed Drug (RLD), thereby circumventing the need to repeat costly and time-consuming animal and human clinical trials.38 This streamlined process significantly reduced the time and financial burden for generic manufacturers to enter the market once primary patents expired.49

A critical component of the ANDA pathway is the Paragraph IV certification. This allows generic manufacturers to assert that a patent listed in the FDA’s Orange Book is either invalid or will not be infringed by their proposed generic product.38 Such a certification frequently triggers immediate patent litigation initiated by the brand-name drug owner.57 To incentivize these challenges, the first generic manufacturer to successfully file a Paragraph IV certification and prevail in litigation is awarded 180 days of exclusive marketing rights, providing a significant head start in the generic market.48 Conversely, if the brand-name company sues the generic applicant within 45 days of receiving the Paragraph IV notice, FDA approval of the ANDA is typically stayed for 30 months, allowing the patent litigation to proceed before generic market entry.48

The Hatch-Waxman Act, while ostensibly designed to promote generic entry and lower drug prices, inadvertently created a framework that incentivizes complex and often protracted patent litigation. The 180-day market exclusivity awarded to the first Paragraph IV filer, coupled with the 30-month stay for the innovator, transforms patent challenges into a strategic chess match rather than a straightforward legal process. This means that even when a generic product is fully developed and ready for market, its entry can be legally blocked for a substantial period, often benefiting the innovator company. This inherent tension within the Act has been a significant point of contention. The “incentive” of the 180-day exclusivity often leads to a fierce competition among generic companies to be the first to file, which, paradoxically, then triggers the 30-month litigation stay. This delay benefits the brand-name company by prolonging its monopoly, even if the underlying patent is eventually found to be invalid or not infringed. This dynamic can also lead to controversial “pay-for-delay” settlements, where brand-name companies pay generic manufacturers to postpone their market entry, further delaying the availability of more affordable medicines.48 Thus, the Act’s dual goals have often resulted in a complex interplay of incentives and delays, shaping the competitive landscape in unforeseen ways.

The Rise of Patent Thickets and Litigation

Brand-name pharmaceutical companies have increasingly adopted a strategic approach of creating “patent thickets”—dense webs of overlapping intellectual property rights surrounding a single drug product.34 These thickets, which can involve 70 or more patents per drug, are designed to protect products from generic competition by making market entry significantly more challenging and costly for generic manufacturers.63 The patents within these thickets often cover various aspects, including formulations, methods of use, manufacturing processes, and even delivery devices.68

The impact of these thickets is profound. Challenging the numerous patents within a thicket can cost generic companies millions of dollars and lead to lengthy and complex legal battles.63 The case of AbbVie’s Humira stands as a prime example. AbbVie amassed over 132 additional patents related to Humira, with some extending exclusivity until as late as 2034.65 This extensive patent portfolio and the ensuing litigation successfully delayed biosimilar entry in the U.S. until 2023, despite biosimilars having entered the European market much earlier.65 Critics argue that patent thickets and the associated practice of evergreening unduly extend monopolies without providing significant new therapeutic benefits, thereby contributing to persistently high drug prices.5

Patent thickets, while legally distinct from the original compound patent, effectively function as a de facto extension of market exclusivity by imposing a substantial legal and financial burden on generic and biosimilar manufacturers. This transforms the competitive landscape from one primarily driven by scientific innovation and manufacturing efficiency to one heavily influenced by legal resourcefulness and the capacity for protracted litigation. The sheer volume and complexity of patents within a thicket create a formidable “litigation barrier”.65 Even if individual patents within the thicket might be considered weak or potentially invalid, the prohibitive cost of litigating dozens of patents, coupled with the significant risk of substantial damages if found to infringe, makes it economically unfeasible for many generic companies to mount a comprehensive challenge.63 This dynamic effectively extends the brand’s monopoly, even in the absence of a single, unassailable primary patent. Consequently, market access for more affordable medicines is not solely determined by the expiration of the original patent but by the brand-name company’s ability to maintain a robust, multi-layered intellectual property defense that significantly raises the “cost of entry” for competitors. This has profound implications for drug pricing and patient access, as starkly demonstrated by the protracted market exclusivity of drugs like Humira.65

Biosimilars and the “Patent Dance”

Biologics, unlike small-molecule drugs, are complex medicines derived from living organisms.9 Their follow-on products, biosimilars, are highly similar versions of these reference biologics, necessitating a distinct regulatory approval pathway compared to traditional generics.9 Biologics benefit from robust intellectual property protection, which includes not only patents covering their core molecular structure, formulations, and manufacturing processes but also extended data exclusivity periods.9 In the U.S., regulatory exclusivity for biologics typically spans 12 years.80

The Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA) established an abbreviated pathway for biosimilar approval and introduced a unique, structured dispute resolution procedure colloquially known as the “patent dance”.9 This framework mandates a structured exchange of confidential information between the biosimilar applicant and the reference product sponsor, designed to identify and facilitate the early resolution of potential patent disputes.101 While the BPCIA states that the applicant “shall” provide certain information, the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in

Amgen v. Sandoz (2017) clarified that the patent dance is not strictly mandatory.101 However, opting out carries significant consequences, such as shifting control over the timing and scope of litigation to the reference product sponsor.101

The BPCIA’s “patent dance” is more than a mere litigation procedure; it functions as a legislatively mandated negotiation framework specifically tailored to facilitate the early resolution of complex patent disputes surrounding biologics. The inherent complexity of biologics and the extensive patent portfolios (often characterized as patent thickets) that protect them necessitate such a structured approach.9 The Supreme Court’s affirmation that the patent dance is not mandatory underscores its role as a strategic tool rather than an inflexible requirement. This provides parties with the flexibility to weigh the risks and benefits of engaging in the structured information exchange, with its attendant disclosure requirements, against the potential advantages of proceeding directly to litigation. This adds a unique layer of strategic complexity to biosimilar market entry, as companies must not only assess the validity of patents but also carefully consider the tactical implications of participating in or abstaining from the “dance.”

Table 5: Examples of Prominent Patent Thickets

| Drug Name | Innovator Company | Key Patent Strategy/Claims | Impact on Generic/Biosimilar Entry |

| Humira (adalimumab) | AbbVie | Over 132-250+ secondary patents on formulation, manufacturing processes, methods of administration, and devices, with some expiring as late as 2034.65 | Delayed U.S. biosimilar entry until 2023, despite earlier entry in Europe (October 2018), leading to billions in excess spending.65 |

| Lipitor (atorvastatin) | Pfizer | Extensive patent landscape covering novel formulations, manufacturing processes, intermediate purification methods, and polymorphs (e.g., crystalline and amorphous forms, US 5,273,995).103 | Primary patent expired in late 2010, leading to rapid generic proliferation. Subsequent litigation and settlements, including alleged “pay-for-delay” schemes, aimed to delay generic entry.61 |

VII. Emerging Trends and Future Outlook

The landscape of pharmaceutical patent claims is in a constant state of flux, driven by rapid scientific advancements and evolving legal interpretations. Several emerging trends are poised to redefine patent strategies and intellectual property management in the coming decades.

Personalized Medicine and Gene Therapies

Personalized Medicine (Precision Medicine) involves tailoring medical treatments to an individual’s unique genetic makeup, environmental factors, and lifestyle.107 This approach naturally leads to the development of more narrowly defined patent claims that target specific genetic markers or patient subgroups.34

However, patenting innovations in personalized medicine presents distinct challenges:

- Complexity of Genetic-Based Treatments: The intricate biotechnological processes and deep understanding of genetic interactions involved make it difficult to meet traditional patent requirements of novelty, non-obviousness, and utility.109 Proving novelty is particularly challenging given the vast existing body of genetic research, and demonstrating non-obviousness for treatments built upon known genetic information is equally complex.109

- Patent Eligibility of Genetic Information: The legal landscape surrounding the patentability of naturally occurring genetic sequences remains complex and varies significantly by jurisdiction.109 Landmark cases, such as

Association for Molecular Pathology v. Myriad Genetics (2013) in the U.S., significantly limited the patentability of “mere isolation of genes,” ruling that naturally occurring DNA sequences are products of nature and thus not patentable.39 - Data Protection and Privacy: Personalized medicine’s reliance on extensive genetic and health data introduces significant data protection and privacy challenges, necessitating compliance with stringent regulations like GDPR and HIPAA.109

Despite these hurdles, opportunities for patenting abound:

- Focus on Novel Biotechnological Processes: A viable strategy involves focusing patent protection on the unique methods or technologies used to develop, administer, or diagnose with personalized treatments, rather than on the genetic sequences themselves.109

- Diagnostic Methods and Algorithms: Patents can cover novel diagnostic equipment, biomarkers, and unique algorithms used in the analysis of patient data, such as those that match patients to the most effective therapies.109 Integrating these algorithms with specific hardware can further strengthen patent claims by demonstrating a practical application.109

Gene Therapies involve the insertion of genetic material into cells to treat genetic diseases.115 Patenting in this rapidly advancing field presents its own set of challenges and opportunities:

- Challenges: The inherent complexity of biological processes and the fast-paced evolution of gene therapy technology make it difficult to maintain a robust patent portfolio.116 Ethical implications concerning genetic modifications are also a significant consideration.116 High-profile disputes, such as the CRISPR-Cas9 patent battle, underscore the complexities surrounding foundational gene editing technologies and inventorship.117 Patent claims must be meticulously crafted to cover specific vectors, therapeutic genes, and delivery methods while anticipating potential design-arounds by competitors.116

- Opportunities: Patentable aspects include novel vectors, gene editing technologies (e.g., CRISPR-Cas9), innovative methods of delivery (e.g., viral vectors like adeno-associated virus (AAV) or non-viral approaches such as lipid nanoparticles (LNPs)), and the therapeutic genes themselves.115 Strategic portfolio development and leveraging international patent treaties are crucial for securing broad protection.116

The legal precedents limiting the patentability of naturally occurring genetic material have fundamentally shifted the focus in personalized medicine and gene therapy patenting. The emphasis is increasingly moving from patenting the biological “product” itself (e.g., a raw gene sequence) to protecting the methods of using, modifying, delivering, or diagnosing with that biological material. This strategic adaptation is a direct consequence of rulings like Myriad Genetics, which clarified that isolated DNA, if identical to naturally occurring DNA, is not patentable subject matter.39 Consequently, companies are now concentrating their patenting efforts on “novel biotechnological processes” 109, “methods and technologies that identify genetic markers” 110, “algorithms for data analysis” 110, and “novel vectors, gene editing technologies, methods of delivery”.116 This represents a critical transition from protecting the “what” (the biological entity) to the “how” (its application, modification, or diagnostic process). This necessitates extremely precise and technically detailed claim drafting, often requiring the integration of hardware or specific clinical applications to overcome rejections based on “abstract ideas” or “natural phenomena”.111 This trend not only shapes the future landscape of biotech intellectual property but also drives innovation towards the

application and utility of biological insights rather than solely their discovery.

Artificial Intelligence (AI) in Drug Discovery and Patenting

Artificial intelligence is rapidly transforming the drug discovery pipeline, offering unprecedented potential to accelerate target identification, optimize molecule design, and streamline clinical trials.2 This integration can significantly shorten traditional development timelines and substantially reduce costs.

However, patenting drugs developed with AI introduces complex legal challenges:

- Human Inventorship: A core tenet of U.S. patent law requires a human inventor; AI cannot be named as such.2 To secure a patent, human contributions must be “significant,” involving actions such as designing the AI model, validating AI-generated outputs through wet lab experiments, or iterating on results to improve efficacy or safety.2

- Subject Matter Eligibility: AI-related inventions, particularly algorithms, face the risk of being classified as abstract ideas or natural phenomena under 35 U.S.C. § 101.2 Patent claims must demonstrate how these ideas are integrated into practical applications or yield technical improvements to be deemed patent-eligible.2

- Disclosure Requirements: The “black box” nature of some AI systems, where their decision-making processes are opaque, complicates the patent requirement to provide sufficient detail for a person skilled in the art to practice the invention without undue experimentation.2

- Non-obviousness: As AI becomes a standard tool in drug discovery, the definition of what constitutes a “non-obvious” invention may shift. If AI can readily generate a molecule, demonstrating significant human ingenuity beyond the AI’s output becomes crucial for patentability.2

Despite these challenges, strategic opportunities for successful patenting exist:

- Documenting Human Contributions: Meticulous record-keeping of the inventive process, including AI prompts, parameters, human decisions based on AI outputs, and experimental validation data, is vital to establish human inventorship.2

- Modifying AI Outputs: Actively synthesizing, testing, and optimizing AI-generated suggestions through human experimentation demonstrates significant human contribution and strengthens patent claims.2

- Specialized AI Systems: Developing AI systems tailored to specific, complex problems (e.g., optimizing binding affinity) highlights human ingenuity in the system’s design, thereby enhancing patent claims.2

- Legal Expertise: Engaging experienced patent counsel with a dual understanding of AI and pharmaceuticals is essential for drafting robust claims that meet USPTO requirements and navigate the evolving legal landscape.2

The integration of AI into drug discovery is compelling patent offices and courts to redefine fundamental legal concepts such as human inventorship and the very definition of a non-obvious “invention.” As AI systems grow in sophistication, the distinction between human ingenuity and machine-generated output becomes increasingly blurred, compelling the legal system to clarify the boundaries of patentability. The central issue revolves around how to attribute inventorship when AI plays a significant role in the inventive process. This requires a precise definition of “significant human contribution”.2 Furthermore, if an AI can “easily generate” a new molecule, it directly challenges the traditional concept of “non-obviousness,” which has long been a cornerstone of patent law.2 This ongoing re-evaluation of what constitutes patentable innovation in an AI-driven world will likely lead to new legal precedents and potentially legislative changes. Pharmaceutical companies must adapt by meticulously documenting human oversight and intervention at every stage of AI-assisted discovery, effectively demonstrating that the human element remains central to the “inventive concept” to secure and defend their patents.

Leveraging Patent Analytics for Competitive Advantage

Patent data, often overlooked beyond its direct legal function, constitutes a veritable “treasure trove” of strategic information.127 This data provides profound insights into competitors’ R&D priorities, technological strengths, future strategic directions, and emerging market trends.

- Competitive Intelligence: Systematic patent monitoring serves as an early warning system for competitive threats, enabling companies to detect nascent competitive products years before they enter clinical trials or receive regulatory approval.128 This intelligence is crucial for evaluating the potential impact of competitor innovations on existing product lines, assessing and redirecting R&D investments, and accurately forecasting market dynamics.58

- Freedom-to-Operate (FTO) Analysis: An FTO analysis is a critical legal assessment designed to identify potential patent barriers that could impede the commercialization of a product.128 In biopharmaceuticals, this involves a meticulous scrutiny of patents related to drug compounds, formulations, manufacturing methods, and therapeutic uses.132 For generic developers, a rigorous FTO is indispensable to avoid costly litigation and ensure successful market entry.132

- White Space Analysis: This analytical approach identifies gaps within the existing patent landscape where there is limited or no innovation.128 These “white spaces” represent significant opportunities for proprietary development with reduced competitive pressure, guiding R&D strategy towards higher-value opportunities and stronger intellectual property positions.128

- AI-Driven Analytics: The advent of machine learning tools has further enhanced patent analytics, enabling the prediction of patent litigations, more efficient identification of white spaces, and streamlining of the FTO process.2

Patent analytics has fundamentally transformed intellectual property management from a reactive legal function—primarily focused on responding to infringement—into a proactive strategic tool. By systematically leveraging patent data, companies can anticipate market shifts, identify competitive threats, and pinpoint innovation opportunities before they become widely apparent. This allows for more informed R&D investments and strategic market positioning.128 This evolution signifies a maturation of intellectual property strategy, elevating it from mere legal compliance to a core component of business intelligence and strategic planning. Companies that effectively integrate patent analytics into their decision-making processes gain a significant competitive edge in the fast-paced and high-stakes pharmaceutical market.10

Global Variations and Harmonization Efforts

The global pharmaceutical industry operates within a fragmented legal landscape, where patent laws and regulatory exclusivities vary significantly across different countries.7 This necessitates a nuanced, jurisdiction-specific approach to developing and executing global patent strategies.10

Key differences in patentability criteria include:

- Method of Treatment Claims: In the U.S., methods for treating or diagnosing human diseases are generally patentable, albeit with a “safe harbor” provision to protect medical practitioners from infringement liability.144 Conversely, in Europe, Japan, and China, methods of treatment are generally

not patentable, primarily due to concerns about restricting medical practice at the point of care.144 However, careful claim wording, such as “purpose-limited composition claims” or “Swiss-type claims” (e.g., “use of compound X in the manufacture of a medicament for treating Y”), can often achieve similar protection in these regions.20 - Polymorphs: While different crystalline forms (polymorphs) of a chemical compound are generally patentable, the standards for doing so vary. China, for instance, imposes stricter criteria, demanding quantifiable evidence of superiority (e.g., enhanced efficacy or stability) over prior art forms and rejecting patents based on routine screening alone.148 This contrasts with the U.S. or Europe, where structural novelty or demonstrating a problem-solving utility may suffice.148

Regulatory exclusivities also exhibit significant global variations in their types and durations. For example, a New Chemical Entity (NCE) in the U.S. typically receives 5 years of exclusivity, while in the EU, data exclusivity can extend to 8 years plus 2 years of market exclusivity (with a potential for an additional year for a new therapeutic indication, totaling 11 years).80 Japan also offers data exclusivity, typically ranging from 8 to 10 years.80

Despite ongoing harmonization efforts through international agreements like the Paris Convention, the Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT), and TRIPS, which have facilitated global patenting processes and introduced some unified criteria 34, substantial differences persist. These variations create significant complexities for pharmaceutical companies seeking comprehensive global protection.146

The persistent global variations in patentability, particularly for method of treatment claims and polymorphs, mean that a “one-size-fits-all” patent strategy is insufficient for pharmaceutical companies operating internationally. Instead, companies must adopt a “jurisdiction-specific claiming” approach, meticulously tailoring their patent applications and claims to meet the unique legal requirements and interpretative nuances of each target market. For instance, a method of treatment claim that is directly patentable in the U.S. may need to be rephrased as a “purpose-limited composition claim” or a “Swiss-type claim” in Europe or Japan to be considered patentable subject matter.149 Similarly, for polymorphs, China’s requirement for comparative data demonstrating superiority over prior art forms may necessitate additional experimental evidence that is not strictly required in other jurisdictions.148 This jurisdiction-specific approach adds significant layers of complexity and cost to building a global patent portfolio. It signifies that achieving global market access is not merely about securing

a patent, but about securing the right kind of patent in each relevant market. This often demands early engagement with local legal experts and foresight during the R&D and drafting stages to generate the necessary supporting data to satisfy diverse national patentability standards.148

Table 6: Comparison of Patentability Criteria for Method of Treatment/Polymorphs across Key Jurisdictions

| Claim Type | Jurisdiction | Patentability Status | Key Considerations/Examples |

| Method of Treatment | US | Patentable | Safe Harbor provision protects medical practitioners from infringement.144 Example: “A method of treating a malignant tumor by administering compound X…”.149 |

| EU | Not Patentable | Excluded to avoid restricting medical practice. Can be protected via “Swiss-type claims” (e.g., “use of substance X for the manufacture of a medicament for treating Y”) or purpose-limited composition claims.20 | |

| Japan | Not Patentable | Excluded due to industrial applicability requirement. Can be rewritten into purpose-limited composition claims.146 Example: “A pharmaceutical composition for treating a malignant tumor comprising compound X…”.149 | |

| China | Not Patentable | Methods for diagnosis of diseases are not patentable.147 | |

| Polymorphs | US | Patentable | Structural novelty or problem-solving utility may suffice. Example: Crystalline empagliflozin (Jardiance®).22 |

| EU | Patentable | Structural novelty or problem-solving utility may suffice.105 | |

| Japan | Patentable | Strict interpretation of inventive step can pose challenges.145 | |

| China | Difficult to Patent | Requires quantifiable evidence of superiority (e.g., enhanced efficacy, stability) over prior art forms; rejects routine screening alone.148 |

VIII. Conclusion: Navigating the Future of Pharmaceutical Patent Claims

The evolution of patent claims in drug lifecycle management stands as a compelling testament to the dynamic interplay among scientific advancement, intricate legal frameworks, and commercial imperatives. What began with relatively simple compound patents has transformed into a sophisticated landscape characterized by complex thickets of secondary claims. This strategic adaptation has been driven by the continuous need to maximize market exclusivity and incentivize the substantial investments required for pharmaceutical innovation.

Success in this perpetually evolving environment demands a holistic and proactive intellectual property strategy that seamlessly integrates legal, scientific, and business insights. Key imperatives for pharmaceutical companies include: building diverse and layered patent portfolios that cover every conceivable aspect of a drug; maintaining meticulous documentation of all inventive contributions, particularly in the context of AI-assisted discoveries; conducting early and continuous patent landscape analyses, encompassing Freedom-to-Operate (FTO) and white space identification; and demonstrating agility in adapting to the significant global variations in patentability criteria and regulatory exclusivities.

The enduring tension between incentivizing pharmaceutical innovation through robust patent protection and ensuring affordable public access to life-saving medicines remains a central and contentious debate. Looking forward, the transformative influence of personalized medicine, gene therapies, and artificial intelligence will further complicate this delicate balance. These emerging technologies introduce novel challenges related to patent eligibility for biological materials and the attribution of inventorship in AI-driven processes, while simultaneously opening new avenues for strategic patenting through highly specific claims. Navigating these multifaceted complexities with foresight and adaptability will be the defining characteristic of leadership in the pharmaceutical industry for decades to come, shaping both the future of medical innovation and equitable healthcare access.

Works cited

- Patentability of methods of treatment and diagnosis – Venner Shipley, accessed July 26, 2025, https://www.vennershipley.com/insights-events/patentability-of-methods-of-treatment-and-diagnosis/

- Filing Strategies for Maximizing Pharma Patents: A Comprehensive Guide for Business Professionals – DrugPatentWatch, accessed July 26, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/filing-strategies-for-maximizing-pharma-patents/

- Patenting Drugs Developed with Artificial Intelligence: Navigating the Legal Landscape, accessed July 26, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/patenting-drugs-developed-with-artificial-intelligence-navigating-the-legal-landscape/

- The Interface of Patents with the Regulatory Drug Approval Process and How Resulting Interplay Can Affect Market Entry – IP Mall, accessed July 26, 2025, https://ipmall.law.unh.edu/sites/default/files/hosted_resources/IP_handbook/ch10/ipHandbook-Ch%2010%2009%20Fernandez-Huie-Hsu%20Patent%20and%20FDA%20Interface%20rev.pdf

- Conducting a Biopharmaceutical Freedom-to-Operate (FTO) Analysis: Strategies for Efficient and Robust Results – DrugPatentWatch, accessed July 26, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/conducting-a-biopharmaceutical-freedom-to-operate-fto-analysis-strategies-for-efficient-and-robust-results/

- The Role of Patents and Regulatory Exclusivities in Drug Pricing | Congress.gov, accessed July 26, 2025, https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/R46679

- Patent Considerations for Drug Regulatory Approval – PatentPC, accessed July 26, 2025, https://patentpc.com/blog/patent-consideration-for-drug-regulatory-approval

- The Patent Playbook Your Lawyers Won’t Write: Patent strategy development framework for pharmaceutical companies – DrugPatentWatch, accessed July 26, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-patent-playbook-your-lawyers-wont-write-patent-strategy-development-framework-for-pharmaceutical-companies/

- What are the types of pharmaceutical patents? – Patsnap Synapse, accessed July 26, 2025, https://synapse.patsnap.com/blog/what-are-the-types-of-pharmaceutical-patents

- What role do IP rights play in biologics and biosimilars? – Patsnap Synapse, accessed July 26, 2025, https://synapse.patsnap.com/article/what-role-do-ip-rights-play-in-biologics-and-biosimilars

- Developing a Comprehensive Drug Patent Strategy – DrugPatentWatch – Transform Data into Market Domination, accessed July 26, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/developing-a-comprehensive-drug-patent-strategy/

- Patent Considerations for Medical Device Clinical Trials – PatentPC, accessed July 26, 2025, https://patentpc.com/blog/patent-considerations-for-medical-device-clinical-trials

- What Are the 5 Stages of Drug Development? | University of Cincinnati, accessed July 26, 2025, https://online.uc.edu/blog/drug-development-phases/

- The Drug Development Process | FDA, accessed July 26, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/patients/learn-about-drug-and-device-approvals/drug-development-process

- The Impact of Drug Patent Expiration: Financial Implications, Lifecycle Strategies, and Market Transformations – DrugPatentWatch, accessed July 26, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-impact-of-drug-patent-expiration-financial-implications-lifecycle-strategies-and-market-transformations/

- Lesson 1: Patent Concepts | UW-Madison Libraries, accessed July 26, 2025, https://learn.library.wisc.edu/patents/lesson-1/

- Mastering the Body of a Patent Claim – Number Analytics, accessed July 26, 2025, https://www.numberanalytics.com/blog/mastering-body-of-patent-claim

- 7 Core Concepts: Patent Fundamentals – OC Patent Lawyer, accessed July 26, 2025, https://ocpatentlawyer.com/wp-content/uploads/prospectiveclientdownloads/7CoreConceptsPatentFundamental.pdf

- blueironip.com, accessed July 26, 2025, https://blueironip.com/ufaqs/how-does-the-phrase-consisting-essentially-of-differ-from-comprising-and-consisting-of-in-patent-claims/#:~:text=%E2%80%9CComprising%E2%80%9D%3A%20Open%2Dended,invention’s%20basic%20and%20novel%20characteristics.

- MPEP 2111.03: Transitional Phrases, November 2024 (BitLaw), accessed July 26, 2025, https://www.bitlaw.com/source/mpep/2111-03.html

- Types of Pharmaceutical Patent | MPA Business Services, accessed July 26, 2025, http://mpasearch.co.uk/product-process-formulation-patents

- Patent Litigation in the Pharmaceutical Industry: Key Considerations, accessed July 26, 2025, https://patentpc.com/blog/patent-litigation-in-the-pharmaceutical-industry-key-considerations

- Using Solid Form Patents to Protect Pharmaceutical Products — Part I – Barash Law, accessed July 26, 2025, https://www.ebarashlaw.com/insights/part1

- Topic 8 – Specific Types of Claims – WIPO, accessed July 26, 2025, https://www.wipo.int/edocs/mdocs/aspac/en/wipo_ip_cmb_17/wipo_ip_cmb_17_8.pdf

- Patenting New Uses for Old Inventions – Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law, accessed July 26, 2025, https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2919&context=vlr

- Patent protection strategies – PMC, accessed July 26, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3146086/

- US8541470B2 – Topical pharmaceutical formulation – Google Patents, accessed July 26, 2025, https://patents.google.com/patent/US8541470B2/en

- What is a Product-By-Process Claim? – BlueIron IP, accessed July 26, 2025, https://blueironip.com/ufaqs/what-is-a-product-by-process-claim/

- 2113-Product-by-Process Claims – USPTO, accessed July 26, 2025, https://www.uspto.gov/web/offices/pac/mpep/s2113.html

- Product-by-Process Claiming: A Deep Dive, accessed July 26, 2025, https://www.numberanalytics.com/blog/product-by-process-claiming-deep-dive

- 2117-Markush Claims – USPTO, accessed July 26, 2025, https://www.uspto.gov/web/offices/pac/mpep/s2117.html

- What is the format for Markush claims? – Patsnap Synapse, accessed July 26, 2025, https://synapse.patsnap.com/article/what-is-the-format-for-markush-claims

- Markush structure – Wikipedia, accessed July 26, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Markush_structure

- Navigating Markush Claims in Patent Ethics – Number Analytics, accessed July 26, 2025, https://www.numberanalytics.com/blog/ultimate-guide-markush-claims-patent-ethics

- The Evolution of Patent Claims in Drug Lifecycle Management …, accessed July 26, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-evolution-of-patent-claims-in-drug-lifecycle-management/

- History of patent law – Wikipedia, accessed July 26, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_patent_law