Introduction: More Than a Name—The High-Stakes World of Pharmaceutical Branding

What’s in a name? When it comes to pharmaceuticals, the answer is: billions of dollars, years of research, and the health of millions of people. The seemingly bizarre, often unpronounceable names that adorn our medicine cabinets—Wegovy, Xeljanz, Zepbound, QALSODY—are not the product of random chance.1 They are the meticulously crafted endpoints of a multi-year, multi-million-dollar journey, a “cocktail of complex regulations, invented words, focus groups, tastes and trends, algorithms, and even AI”. A drug’s name is arguably the single most-used piece of its intellectual property, the vessel that carries the weight of a company’s scientific innovation and commercial ambition.

This report will guide you, the strategic professional, through this high-stakes world. We will move beyond a simple procedural description to deliver a strategic analysis of pharmaceutical naming. Our core thesis is that drug naming is not a mere marketing task to be checked off before launch; it is a critical strategic function that sits at the nexus of science, art, regulation, and commerce.3 The process is a complex negotiation involving a host of stakeholders: the pharmaceutical firms investing fortunes in development, the global regulatory bodies like the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) acting as gatekeepers, the scientific councils like the United States Adopted Names (USAN) Council and the World Health Organization (WHO) striving for global safety and clarity, and, most importantly, the healthcare professionals and patients who must use these names safely and effectively every single day.

We will begin by deconstructing a drug’s identity, clarifying the distinct roles of its three names: chemical, generic, and brand. From there, we will delve into the rigorous, rule-based science of generic nomenclature, revealing how this system of global standardization is not only a pillar of patient safety but also a powerful tool for commercial acceleration and competitive intelligence. We will then pivot to the creative and psychological art of brand naming, exploring how companies forge blockbuster identities that can endure for decades.

Our journey will take us through the regulatory gauntlet, demystifying the complex approval processes of the FDA and EMA and highlighting the critical risks and strategic considerations for achieving global approval. We will confront the sobering reality of Look-Alike, Sound-Alike (LASA) medication errors, quantifying the human and commercial cost of confusion and examining the lessons learned from past failures.

Finally, we will culminate in the most critical section for any business leader: a deep dive into how the entire naming ecosystem can be leveraged as a potent competitive intelligence weapon. We will show you how to read between the lines of patent filings, track competitor R&D pipelines years before they become public, and deploy advanced brand franchise strategies to dominate a therapeutic category. This report is designed to equip you not just to understand the process, but to master it—turning what many see as a complex hurdle into a source of profound and sustainable competitive advantage.

The Naming Trinity: Deconstructing a Drug’s Identity

Before we can navigate the strategic complexities of drug naming, we must first establish a foundational understanding of the three distinct names every medication possesses. Each name serves a unique purpose, moving from pure scientific description to universal identifier to commercial asset. Mastering this trinity—chemical, generic, and brand—is the first step toward leveraging nomenclature as a strategic tool.

The Chemical Name: The Molecular Blueprint

Every new drug begins its life as a molecule, and its first name is a direct reflection of that structure. The chemical name, typically assigned according to the rules of the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC), is a precise, scientific descriptor of the drug’s atomic and molecular architecture.6 It is, in essence, the compound’s molecular blueprint translated into language.

For example, the common pain reliever known to consumers as Tylenol and to pharmacists as acetaminophen has the chemical name N-(4-hydroxyphenyl) acetamide. Similarly, the anti-anxiety medication Valium, or diazepam, is chemically known as 7-chloro-1,3-dihydro-1-methyl-5-phenyl-2H-1,4-benzodiazepin-2-one.

These names are invaluable for chemists, patent attorneys, and researchers. They provide an unambiguous structural identity that is crucial for patent applications, scientific publications, and the manufacturing process. However, their very precision makes them entirely impractical for clinical or commercial use. They are complex, cumbersome, and impossible for most healthcare professionals—let alone patients—to remember or pronounce correctly. The chemical name is the drug’s “true” scientific identity, the bedrock upon which all other, more practical names are built, but it is not the name used in the daily practice of medicine.

The Generic (Nonproprietary) Name: The Universal Language of Medicine

As a drug candidate shows promise and moves toward clinical trials, it needs a more functional identifier. This is the role of the generic, or nonproprietary, name. This is the official, globally recognized name for the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API).6 Unlike a brand name, the generic name is public property; it is not owned by any single company and is intended for use in pharmacopoeias, scientific literature, and by any manufacturer producing the drug.8

For instance, sildenafil is the generic name for Pfizer’s well-known brand, Viagra.10 Atorvastatin is the generic name for the cholesterol-lowering drug Lipitor.12 This name remains with the drug for its entire lifecycle, becoming especially important after the innovator company’s patent expires. When other companies begin to manufacture the drug, they must use the same generic name, ensuring consistency and clarity in the marketplace.

The generic name is the great equalizer in global medicine. It is the critical tool that ensures a physician in Tokyo, a pharmacist in Texas, and a researcher in Geneva are all discussing the exact same active substance.8 This universal language is a cornerstone of patient safety, preventing the chaos that would ensue if every country or company used a different scientific name. Furthermore, it is the very foundation of the multi-billion dollar generic drug market, which depends on this standardized identifier to function. Without the generic name, the concept of a chemically equivalent, lower-cost alternative to a branded drug would be nearly impossible to regulate or implement safely.15

The Brand (Proprietary) Name: The Commercial Identity

Finally, we arrive at the name most familiar to consumers: the brand, or proprietary, name. This is the trademarked name developed, owned, and marketed exclusively by the company that innovated the drug.6 While the generic name is rooted in science and standardization, the brand name is born from strategy and creativity. It is designed to be catchy, memorable, and to build a unique brand identity that captures the minds of prescribers and patients.7

Think of Tylenol for acetaminophen, Advil for ibuprofen, or Lipitor for atorvastatin.7 These names are powerful commercial assets. They are the primary vehicle for a company’s marketing investment, which can often be double what is spent on the research and development of the drug itself. The goal is to build brand loyalty and differentiate the product in what is often a crowded therapeutic market. A successful brand name creates an identity so strong that doctors continue to write prescriptions for it, and patients continue to ask for it, long after cheaper generic versions become available.19 It is the company’s enduring claim on the product’s identity, a piece of intellectual property that, unlike a patent, can last forever.

The Science of Standardization: The Global Language of Generic Names

The world of generic drug naming is one of order, logic, and international cooperation. It is a system designed to replace clinical chaos with scientific clarity. This process, governed by a global partnership of regulatory and scientific bodies, creates a universal language for medicine. For the pharmaceutical strategist, understanding this system is not just about appreciating the rules; it’s about recognizing the commercial advantages and competitive intelligence opportunities embedded within this framework of standardization.

The Architects of Order: USAN and the WHO INN Programme

At the heart of generic nomenclature are two key organizations working in tandem to create a single, harmonized system for the entire world.

The World Health Organization’s International Nonproprietary Name (INN) Programme is the global standard-setter. Established in 1953, its mission is elegantly simple: to provide one unique, universally available name for every pharmaceutical substance.8 This ensures that a drug can be clearly identified, safely prescribed, and discussed without confusion anywhere on the planet. The INN list now contains over 7,000 names and continues to grow by 120-150 new names each year, a testament to the ongoing pace of pharmaceutical innovation. These names are public property, free for anyone to use, which is fundamental to their role in global health.

In the United States, the primary body is the United States Adopted Names (USAN) Council. The USAN Council is a unique partnership between the American Medical Association (AMA), the United States Pharmacopeial Convention (USP), and the American Pharmacists Association (APhA), with a liaison from the FDA.5 Its role is to assign the official generic name for any drug intended to be marketed in the US. Obtaining a USAN is a legal and regulatory necessity; with very few exceptions, a drug cannot be sold in the United States without one.

Crucially, these two bodies do not operate in isolation. There is a deep and long-standing collaboration between the USAN Council and the WHO’s INN Programme. Their shared goal is to ensure that the USAN assigned in the United States is, whenever possible, identical to the INN used internationally.5 This harmonization effort is remarkably successful, and it is now rare for a drug to have a different generic name inside and outside the US. The well-known case of acetaminophen (USAN) versus paracetamol (INN) is a historical anomaly that predates the modern era of close collaboration.5

This global partnership is often framed in the context of patient safety, which is its primary purpose. However, for a company engaged in modern, global drug development, this harmonization provides a powerful commercial advantage. Pharmaceutical innovation is no longer a domestic affair; clinical trials are vast, multinational operations spanning dozens of countries. A single, harmonized generic name dramatically simplifies the logistics, regulatory submissions, and communication for these global trials. Instead of juggling multiple regional names for a single compound, researchers, regulators, and participants in every country can use one consistent identifier. This reduction in complexity minimizes the potential for error, streamlines the entire development process, and ultimately helps accelerate a drug’s journey to market. Thus, the scientific goal of harmonization directly translates into a significant commercial benefit.

Cracking the Code: The Logic of the INN Stem System

The INN system is not arbitrary; it is built on a logical foundation known as the stem system. A “stem” is a specific syllable, usually a suffix, that is shared by drugs within the same pharmacological or chemical class. It acts as a code, conveying essential information about the drug’s mechanism of action to anyone familiar with the system.5

Michael Quinlan, a naming expert at Pfizer, aptly describes the stem as the drug’s “family name”. For example:

- Drugs with the stem -olol (e.g., atenolol, propranolol) are beta-blockers, used to treat cardiovascular conditions.

- Drugs with the stem -pril (e.g., captopril, lisinopril) are ACE inhibitors, another class of antihypertensive agents.

- Drugs with the stem -statin (e.g., atorvastatin, simvastatin) are HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors used to lower cholesterol.

- Drugs with the stem -mab (e.g., adalimumab, trastuzumab) are monoclonal antibodies, a major class of biologic therapies.

While the stem identifies the family, the “prefix” is what gives the drug its unique identity. This is typically a distinctive, often randomly generated syllable or two that distinguishes one member of the class from another (e.g., the atorva- in atorvastatin versus the simva- in simvastatin).5 This combination of a unique prefix and a common stem creates a name that is both informative and distinct.

To provide a practical reference for professionals, the following table outlines some of the most common stems and their meanings.

Table 1: The INN Stem Lexicon: Decoding Generic Drug Names

| Stem | Drug Class / Definition | Examples |

| -afil | Phosphodiesterase 5 (PDE5) inhibitor | Sildenafil, Tadalafil |

| -anib | Angiogenesis inhibitor | Pazopanib, Vandetanib 21 |

| -azepam | Benzodiazepine (antianxiety) | Diazepam, Lorazepam 21 |

| -caine | Local anesthetic | Lidocaine, Procaine 21 |

| cef- | Cephalosporin antibiotic | Cefalexin, Cefazolin 21 |

| -cillin | Penicillin antibiotic | Amoxicillin, Ampicillin |

| -coxib | COX-2 inhibitor (anti-inflammatory) | Celecoxib, Rofecoxib |

| -cycline | Tetracycline antibiotic | Doxycycline, Minocycline |

| -gliptin | DPP-4 inhibitor (antidiabetic) | Sitagliptin, Vildagliptin |

| -mab | Monoclonal antibody | Adalimumab, Trastuzumab 21 |

| -meran | Messenger RNA (mRNA) product | Tozinameran, Elasomeran 21 |

| -olol | Beta-blocker | Atenolol, Metoprolol 21 |

| -prazole | Proton-pump inhibitor | Omeprazole, Lansoprazole |

| -pril | ACE inhibitor | Captopril, Enalapril 21 |

| -sartan | Angiotensin II receptor blocker | Losartan, Valsartan 21 |

| -statin | HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor | Atorvastatin, Simvastatin 21 |

| -tide | Peptide and glycopeptide | Liraglutide, Semaglutide |

| -vir | Antiviral | Acyclovir, Ritonavir 21 |

From Lab to Lexicon: The Generic Naming Process

The formal process of securing a generic name is a carefully timed and structured negotiation. It typically begins when a drug candidate enters Phase I or Phase II clinical trials, years before it is ready for marketing approval.5 This early timing is strategic. It allows the company to use a standardized, professional name in scientific publications and at conferences, which is far preferable to using an internal company code like “PF-04965842”.5

The process itself is described as a “negotiation” among three parties: the sponsoring pharmaceutical firm, the USAN Council, and the WHO INN Expert Group. The firm initiates the process by submitting an application with several proposed names. The councils then begin their review, evaluating the proposals against several key criteria:

- Adherence to the Stem System: Does the name use the correct stem for its drug class?

- Uniqueness and Clarity: Is the prefix distinct enough to avoid confusion with other generic or brand names? Is it easy to pronounce and remember?

- Global Viability: How well does the name translate into other languages? To ensure global usability, certain letters that are not common to all languages using the Roman alphabet—specifically Y, H, K, J, and W—are avoided in the prefix.

- Non-Promotional Nature: The name cannot contain elements that could be considered marketing, such as parts of the company’s name or laudatory terms like “new” or “best”.

- Avoidance of Limiting Medical Terms: The prefix should not imply a single use (e.g., starting with “Onc-” for an oncology drug), as the drug may later be found to have other therapeutic applications.

Once a name is agreed upon by the firm and the USAN Council, it is submitted to the WHO. The INN Expert Group conducts its own review. If they concur, the name is published as a “proposed INN” (pINN). This opens a four-month public comment period during which any party can raise an objection.8 If no valid objections are raised, the name is finalized and published as a “recommended INN” (rINN), becoming the official generic name for that substance worldwide.8

This seemingly administrative process holds significant value for competitive intelligence. The USAN/INN application is one of the earliest public-facing milestones in a drug’s long development journey. The choice of a stem in the application is a clear and definitive signal of a competitor’s R&D strategy, revealing their commitment to a specific compound and its precise mechanism of action. A savvy analyst can establish monitoring systems for new USAN and INN proposals. The appearance of a new “-tinib” (a tyrosine kinase inhibitor, often for cancer) from a key competitor provides a concrete, early warning of their direction in oncology. This allows a company to begin mapping the future competitive landscape, assessing the threat, and formulating counter-strategies years before the drug has a brand name or appears in late-stage clinical trial databases. It transforms a bureaucratic procedure into a powerful source of predictive, actionable intelligence.

The Art of the Brand: Crafting a Blockbuster Identity

If generic naming is a science of order and standardization, then brand naming is an art of persuasion and differentiation. It’s where the cold logic of chemistry gives way to the warmer currents of psychology, marketing, and creativity. The goal is no longer to classify but to captivate. Crafting a proprietary name is a high-risk, high-reward endeavor aimed at building a commercial identity so powerful that it can become a cultural icon and drive billions in revenue, even long after its patent protection has faded.

The Power of a Name: From Molecule to Cultural Icon

The freedom from the rigid rules of generic nomenclature allows for immense creativity in brand naming. The objective is to create a name that is unique, evocative, and easy for both doctors and patients to remember and pronounce.7 This name becomes a powerful piece of intellectual property. As Michael Quinlan of Pfizer notes, “Pharmaceutical companies tend to promote by their brand name because that’s always going to be our name”. The generic name, sildenafil, eventually enters the public domain, but the brand name, Viagra, is owned by Pfizer forever.

This enduring ownership is the foundation of brand equity. A strong brand name, backed by a compelling narrative and extensive marketing, can build immense loyalty. The aim is to make the brand synonymous with the treatment itself, so that it remains the top choice for prescribers and consumers even when cheaper generic alternatives become available.

The most successful brand names often work on a subtle, psychological level. They are meant to be representative of the drug in some way, suggesting a benefit or evoking a positive feeling without making a direct, regulated claim. Consider these iconic examples:

- Viagra: The name was masterfully crafted to suggest vigor, vitality, and power. It has even been linked to the Sanskrit word for “tiger” (vyaghra), tapping into deep-seated concepts of strength.28 This powerful name helped transform a sensitive medical condition, erectile dysfunction, into a mainstream lifestyle conversation.

- Lipitor: For the blockbuster cholesterol drug, the name is a clear and effective portmanteau of “lipid” and “inhibitor,” immediately communicating its core function to healthcare professionals in a simple, memorable way.30

- Lyrica: Used to treat nerve and muscle pain, this name calls to mind the harmony and soothing quality of “lyrics” or music, creating a positive, gentle association for a drug that manages a difficult condition.

The Creative Crucible: The Role of Naming Agencies

Given the immense stakes—balancing creativity, trademark law, global linguistics, and stringent regulatory requirements—most pharmaceutical companies do not go it alone. They engage specialized naming agencies that live and breathe this complex world. Firms like Brand Institute, Brandsymbol, and Addison Whitney (a Syneos Health company) bring decades of focused expertise to the table.32

The process typically begins during Phase II or III of clinical trials and starts with intense strategic alignment. The agency and the pharmaceutical company collaborate to define the drug’s core value proposition, its target audience, and the desired emotional and phonetic tone of the name.17 Is the drug a powerful, life-saving intervention that needs a name with strong consonants? Or is it a maintenance therapy for a chronic condition that would benefit from a softer, more reassuring sound?

From this strategic brief, the creative teams are unleashed. They often brainstorm hundreds, sometimes thousands, of potential names. Many top agencies pride themselves on starting from a “blank canvas” for each project, avoiding the use of pre-existing name banks to ensure originality and a perfect fit for the specific product.32

These creative efforts generally fall into a few strategic categories:

- Evocative/Abstract Names: These names suggest a feeling, benefit, or positive outcome without making a direct claim. Celebrex, for arthritis, hints at “celebration” of movement. Paxil, for depression and anxiety, evokes “peace”. This is a popular approach as it builds an emotional connection while navigating the strict rules against promotional claims.

- “Empty Vessel” Names: This strategy involves creating a completely new, made-up word. A name like Xeljanz has no inherent meaning but is phonetically distinct, easy to trademark, and provides a “white space” for the company to build a brand identity around from scratch.

- Mechanism-Adjacent Names: These names hint at the science in a simplified way, often for a professional audience. Lipitor (lipid inhibitor) is a classic example. This approach can build credibility with prescribers by subtly referencing the drug’s mechanism of action.

The Funnel of Viability: From 1,000 Ideas to One Global Brand

The journey from a thousand brainstormed ideas to a single, approved global brand name is a brutal process of elimination. Pfizer’s Michael Quinlan vividly describes it as a funnel: “Think of it as a funnel, or like sand through the hour glass: that one grain that makes it through the bottom is what we hope is its global brand name”. This funnel has several critical screening layers, each designed to test the viability of a name from a different angle.4

- Trademark Screening: This is the first major hurdle. Teams of in-house or agency trademark paralegals conduct exhaustive searches across hundreds of international databases.32 They are looking for any potential conflict with existing trademarks, not just in the pharmaceutical space but in any category. A name must be legally available to be ownable.

- Linguistic and Cultural Checks: A name that sounds great in English could be a disaster in another language. Agencies employ in-country, native-speaking professionals to vet candidate names in major global markets. They check for negative connotations, embarrassing translations, or difficult pronunciations.20 A global brand cannot afford a local linguistic faux pas.

- Market Research: The most promising names are then tested with the target audience. Surveys and focus groups with healthcare professionals and patients are used to gauge reactions. How memorable is the name? Is it easy to say and spell? What feelings or ideas does it evoke? Does it sound too much like another drug they know?

- Safety Screening: This is the most critical and intensive screen, which we will detail further in the regulatory and LASA sections. It involves simulating real-world scenarios—handwritten prescriptions, verbal orders, computer data entry—to identify any potential for confusion with other drug names that could lead to a medication error.

This entire process is made more difficult by an ever-increasing challenge: the “crowding” of the pharmaceutical lexicon. Every year, hundreds of new generic and brand names are added to the global vocabulary. Naming consultants speak of the immense difficulty of finding a “white space”—a unique corner of the linguistic landscape that hasn’t already been claimed. This saturation makes the creative process harder, the legal screening more fraught with potential conflicts, and the risk of regulatory rejection significantly higher. This trend is a direct driver of the cost and complexity of modern drug naming, forcing companies to become more inventive—for instance, by using unusual letters like X, Q, and Z to create distinctiveness—and to rely more heavily on the sophisticated data analysis and deep expertise of specialized agencies to navigate this crowded field successfully.

Navigating the Regulatory Gauntlet: Gaining Approval in Key Markets

Creating a clever, memorable, and legally available brand name is only half the battle. That name must then survive the intense scrutiny of the world’s most powerful drug regulatory agencies. This regulatory review is, as one expert puts it, the “additional hurdle that no other industry really has”. A name that has cleared all trademark and marketing checks can still be rejected at the final regulatory gate, making this stage a source of significant risk and uncertainty. Understanding the distinct priorities and processes of the key gatekeepers—the FDA in the US and the EMA in Europe—is paramount for any global pharmaceutical strategy.

The FDA’s Dual Mandate: Balancing Safety and Promotion

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s review of a proprietary name is a delicate balancing act, governed by two specialized divisions with distinct, and sometimes conflicting, mandates.

First is the Division of Medication Error Prevention and Analysis (DMEPA), which acts as the FDA’s safety police. DMEPA’s exclusive focus is on preventing medication errors that could arise from name confusion. Their review is a forensic examination of a proposed name’s potential to be mistaken for another. They scrutinize its spelling (orthography), its sound when spoken (phonetics), and its appearance in both computer text and, critically, in notoriously illegible physician handwriting.

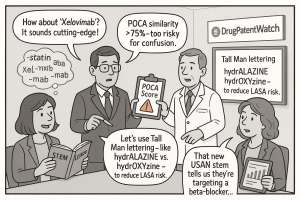

To aid this analysis, DMEPA employs a powerful computational tool called the Phonetic and Orthographic Computer Analysis (POCA) system.33 POCA runs a proposed name against a massive database of existing drug names and calculates a similarity score. While not the only factor, a combined phonetic and orthographic POCA score exceeding a 75% similarity threshold is a major red flag and a strong predictor of rejection.

The second arm of the FDA’s review is the Office of Prescription Drug Promotion (OPDP), which serves as the claim police. OPDP’s mandate is to ensure that a brand name is not “fanciful” or misleadingly promotional, which would misbrand the drug under the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act.38 They reject names that:

- Overstate the drug’s efficacy (e.g., “CureAll”).

- Minimize its risks (e.g., “SafeDose”).

- Broaden its approved indications.

- Make unsubstantiated claims of superiority over other drugs.

This dual-review system creates an inherent tension that every proposed name must navigate. A name needs to be unique and memorable enough to build a brand and avoid confusion with others (satisfying DMEPA), but it cannot be so unique or suggestive that it crosses the line into promotion (triggering an objection from OPDP). It is a narrow tightrope to walk, and a fall on either side leads to rejection.

The European Challenge: The EMA’s Name Review Group (NRG)

While the FDA’s process is rigorous, many in the industry consider the European Medicines Agency’s Name Review Group (NRG) to be the toughest naming gatekeeper in the world.40 The NRG reviews names for all drugs seeking approval via the EU’s centralized procedure. The statistics are stark: the rejection rate for proposed names at the NRG can be as high as 55%.40 This makes a successful EMA name submission a significant strategic achievement.

The NRG’s criteria for rejection are comprehensive and strictly enforced. A proposed name will be found unacceptable if it 41:

- Causes Confusion: This is the primary concern, mirroring the FDA’s. The name cannot be liable to cause confusion in print, handwriting, or speech with any other medicinal product, including those that have been recently withdrawn from the market.41

- Is Misleading: The name cannot convey misleading information about the drug’s therapeutic use, its pharmaceutical properties (e.g., suggesting it’s a “depot” injection when it’s not), or its composition.42

- Is Promotional: Like the FDA’s OPDP, the NRG prohibits names that carry a promotional message.

- Contains an INN Stem: This is a critical and strict rule in Europe. An invented brand name cannot be derived from an INN and must not contain an INN stem. For example, a name like “Cardiopril” for a new ACE inhibitor would be rejected because it incorporates the “-pril” stem.

- Uses Ambiguous Qualifiers: The use of single letters or numbers is strongly discouraged as they can be easily confused with dosage strengths or instructions (e.g., “Drug X 2” could be misinterpreted as “Drug X, 2 tablets”).

A Global Strategy: Harmonizing for Success

Given that most major drugs are launched globally, companies must develop a naming strategy that can succeed in both the US and the EU, as well as other key markets like Canada and Japan. The following table provides a comparative overview to help strategists plan for these parallel, yet distinct, review processes.

Table 2: The Regulatory Gauntlet: FDA vs. EMA Brand Name Review

| Feature | U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) | European Medicines Agency (EMA) |

| Primary Review Bodies | Division of Medication Error Prevention and Analysis (DMEPA); Office of Prescription Drug Promotion (OPDP) | Name Review Group (NRG) 40 |

| Core Focus | Dual focus: Preventing medication errors (DMEPA) and preventing misleading promotion (OPDP) | Primarily public health and safety, with a strong emphasis on preventing confusion and misleading connotations 42 |

| Key Analytical Tools | Phonetic and Orthographic Computer Analysis (POCA) system to assess name similarity 33 | Comprehensive review by experts from all EU member states, considering multiple languages and phonetic systems 42 |

| Rule on INN Stems | Strongly discouraged to avoid confusion, but not an absolute prohibition | Strictly prohibited. Invented names cannot be derived from INNs or contain INN stems |

| Submission Process | Typically one name reviewed at a time. A second can be submitted if the first is rejected | Up to two names can be submitted for review per request 42 |

| Rejection Rate | Significant, but not publicly quantified. Anecdotally lower than EMA. | Extremely high, reported to be as much as 55% 40 |

| Review Timeline | Tentative review can occur post-Phase II, but final approval is not granted until just before marketing authorization | Tentative review can occur up to 18 months before planned submission. Acceptance is valid for 3 years 42 |

A critical strategic risk inherent in this system is what can be called the “reservation dilemma.” A company can spend years and significant resources developing a brand name, shepherd it through internal checks, and even receive a “tentatively acceptable” ruling from the FDA after its Phase II trials. However, this is not a final guarantee. The biggest danger is that another company, also operating under the veil of confidentiality, has a drug in a similar stage of review with a confusingly similar name. If that other drug gets full approval first, it can torpedo your chosen name at the eleventh hour, forcing a last-minute scramble that can disrupt launch preparations, marketing campaigns, and supply chain logistics. The FDA has acknowledged this industry concern and has explored the possibility of a name “reservation” system, but one has not been implemented due to the immense complexity of managing confidential commercial information across multiple pending applications. This unresolved issue represents a significant and largely unmitigable strategic risk, placing an enormous premium on developing not just one, but a portfolio of several strong, viable, and well-vetted name candidates for any major drug launch.

The High Cost of Confusion: LASA Errors and Patient Safety

In the world of pharmaceutical naming, confusion is not just a marketing inconvenience; it is a direct threat to human life. The single most important principle guiding the entire naming process, from generic stems to brand creation, is the prevention of medication errors. Look-Alike, Sound-Alike (LASA) drug names are a persistent and dangerous vulnerability in the healthcare system. Understanding the scale of this problem, learning from catastrophic failures, and internalizing the strategies for risk mitigation are not just matters of regulatory compliance—they are fundamental to a company’s ethical responsibility and long-term commercial viability.

A Persistent Threat: Quantifying the LASA Problem

The statistics surrounding LASA errors are sobering. According to data from national reporting programs, confusion arising from similar drug names is one of the most common causes of medication errors, accounting for a staggering 25% of all reported incidents.45 The consequences are severe. In the United States alone, medication errors are responsible for at least one death every single day and injure approximately 1.3 million people annually, with LASA confusion being a major contributing factor.

A report from the World Health Organization (WHO) included the following statistics from a variety of sources related to the prevalence of medication discrepancies at transitions of care: 3.4-97% of adult patients and 22-72.3% of pediatric patients had at least one medication discrepancy on admission to the hospital. 62% of patients had at least one unintentional medication discrepancy during internal hospital transfer. 25-80% of patients had at least one mediation discrepancy or failure to communicate in-hospital medication changes at discharge.

These errors can happen at any point in the medication use process. A physician with illegible handwriting scrawls a prescription that is misinterpreted by the pharmacist. A nurse in a busy hospital ward mishears a verbal order. A pharmacy technician selects the wrong drug from a computerized dropdown menu where two similar names appear next to each other. A patient gets confused between two of their own medications with similar-looking packages.45

This is a truly global problem. A study in Australia and New Zealand found that of 462 anesthetic-related medication incidents, substitution was one of the top error categories. A three-year study in a hospital in India found that while LASA incidents were 2.67% of total errors, the majority (68.57%) were due to phonetically similar names. The World Health Organization has recognized LASA errors as a critical global patient safety challenge and has issued guidelines to help healthcare systems address the risk. The danger is magnified when the drugs involved are “high-alert” medications like opioids, insulin, or chemotherapy agents, where a mix-up can be rapidly fatal.

Lessons from Failure: When Brand Names Are Recalled

The ultimate commercial consequence of a LASA-prone name is a forced name change after the product is already on the market. This is a logistical and financial nightmare for a company, involving relabeling all stock, re-educating the entire medical community, and rebuilding brand recognition from scratch. These events, while rare, serve as powerful cautionary tales for the entire industry.

Table 3: Anatomy of a Name Change: Learning from LASA Errors

| Original Brand Name (Generic) | Confused With | The Story of the Mix-Up | The Outcome |

| Losec (omeprazole) | Lasix (furosemide) | Shortly after its 1989 launch, reports emerged of the proton pump inhibitor Losec being confused with the potent diuretic Lasix. The names looked similar in cursive script, and both were available in a 20 mg dose. The confusion led to at least one patient death. 19 | The manufacturer changed the brand name in the United States to Prilosec to create greater distinction. |

| Reminyl (galantamine HBr) | Amaryl (glimepiride) | Reminyl, a drug for Alzheimer’s disease, was repeatedly confused with Amaryl, a drug used to lower blood sugar in patients with diabetes. Both were available as 4 mg tablets. In at least two documented cases, Alzheimer’s patients were given Amaryl by mistake, resulting in fatal hypoglycemia. | Following these tragic events and working with the FDA, the manufacturer changed the brand name to Razadyne in 2005. |

| Brintellix (vortioxetine) | Brilinta (ticagrelor) | The FDA received 50 reports of confusion between the antidepressant Brintellix and the blood thinner Brilinta. Both names start with “Bri-,” are of similar length, and can look and sound alike. In 12 cases, the wrong drug was dispensed, though no patients were reported to have taken the wrong medication. 50 | To prevent future errors, the FDA requested a name change, and the brand name was changed to Trintellix. |

| Kapidex (dexlansoprazole) | Casodex (bicalutamide) & Kadian (morphine) | The heartburn medication Kapidex was being confused with Casodex, a prostate cancer drug, and Kadian, a potent extended-release opioid. The potential for catastrophic harm from these mix-ups was extremely high. | The manufacturer proactively changed the brand name to Dexilant in 2010 to mitigate the risk. |

| Celebra (celecoxib) | Celexa (citalopram) | In a pre-launch victory for safety, the proposed name for the blockbuster arthritis drug, Celebra, was flagged by a pharmacy professor as being too similar to the already-marketed antidepressant Celexa. | The FDA agreed with the concern, and the name was changed to the now-famous Celebrex before the drug ever hit the market. |

Building a Safety Net: Proactive Risk Mitigation

Learning from these failures, the industry and regulators have developed a multi-layered safety net to catch and prevent LASA errors before they can cause harm.

A simple but effective strategy is the use of Tall Man Lettering. Endorsed by the FDA and the Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP), this technique uses a mix of lower-case and upper-case letters to visually emphasize the dissimilar parts of two look-alike names. For example, the generic names hydralazine and hydroxyzine become hydrALAZINE and hydrOXYzine. The antidepressant Paxil and the antifungal Lamisil become PAXil and LAMisil. This simple visual cue can be remarkably effective at breaking the brain’s tendency to gloss over the similar parts of the words.51

Technology also plays a crucial role. Barcode Medication Administration (BCMA) systems, which require a nurse to scan both the patient’s wristband and the medication’s barcode before administration, can prevent many dispensing and administration errors. Furthermore, modern Clinical Decision Support (CDS) systems embedded within Electronic Health Records (EHRs) can be programmed to flash an alert to a physician when they are about to prescribe a drug with a known LASA counterpart, forcing a moment of verification.

Ultimately, the most effective mitigation happens long before a drug reaches the pharmacy shelf. The rigorous safety screening conducted by pharmaceutical companies and their naming agencies is the first and most important line of defense. This includes not just computational analysis like POCA, but also real-world prescription simulation tests. These studies involve showing handwritten prescriptions, playing back simulated verbal orders, and having participants type names into computer systems to see where confusion might arise in a realistic setting.

This deep focus on safety has profound competitive implications. When developing a new product, a company’s competitive analysis must extend beyond the clinical profiles and marketing messages of rival drugs to include a “nomenclatural analysis.” If the market-leading drug in a therapeutic class is named “Xylos,” proposing a new competitor named “Zylos” is not just a regulatory gamble, it’s a poor strategic choice. Even if it were to be approved, the high likelihood of pharmacist callbacks, dispensing errors, and potential patient harm would tarnish the brand’s reputation from day one. A truly savvy company will therefore proactively seek a name that is phonetically and orthographically distinct from its key competitors, carving out a unique and, most importantly, safe identity in the minds of prescribers, pharmacists, and patients.

From Data to Dominance: Naming as a Competitive Intelligence Tool

We now arrive at the strategic apex of our discussion. For the most sophisticated pharmaceutical organizations, the naming process is not a siloed regulatory or marketing function. It is a powerful, continuous engine of competitive intelligence. Every step, from the first whisper of a generic name application to the global launch of a brand, generates a trail of data. Learning to capture, analyze, and act on this data can transform a company’s strategy from reactive to predictive, providing a decisive edge in the marketplace.

Beyond the Label: The Naming Process as a Strategic Operation

The critical shift in mindset is to view the entire naming ecosystem as a source of strategic intelligence.4 Each component reveals a different facet of a competitor’s strategy:

- The generic name application is an early, public declaration of a competitor’s commitment to a specific molecule and mechanism of action.

- The choice of a brand name and its associated marketing campaign reveals their commercial strategy, target audience, and desired market positioning.

- The global regulatory filings for that name unveil their timeline, international ambitions, and the scale of their planned launch.

- And most profoundly, the patent filings that underpin the entire enterprise contain a detailed blueprint of their deepest R&D secrets and long-term lifecycle plans.

By connecting these seemingly disparate dots, a company can build a remarkably complete picture of a competitor’s strategy and intentions, often years before they are publicly announced.

Unlocking Competitor Strategy with Patent Data

Pharmaceutical patents are a treasure trove of competitive intelligence, and services like DrugPatentWatch have built their business on helping companies systematically mine this rich data source.4 A patent is far more than a legal shield; it is a detailed roadmap of a competitor’s scientific thinking, their development challenges, and their strategic vision for a product.57

Reading Between the Lines of a Patent Filing

To the untrained eye, a patent is an impenetrable wall of legal and scientific jargon. But for a trained analyst, it is a detailed story waiting to be read. The key is knowing what to look for 57:

- The Claims: This section is the legal fortress of the patent, defining exactly what the innovator considers novel and is protecting. By analyzing what is claimed versus what is left unclaimed, a competitor can identify potential “design-around” opportunities. If a patent claims a specific formulation with excipients A, B, and C, it immediately raises the strategic question: could we develop a non-infringing formulation using A, B, and D?.

- The Detailed Description and Examples: This section is the closest you can get to reading a competitor’s lab notebook. It often details the various formulations that were tested, the excipients used to overcome challenges like poor solubility, the stability data generated, and the manufacturing processes explored. This reveals not just what worked, but also what didn’t work, providing invaluable insights into the product’s underlying strengths and weaknesses.

- The Patent Type: The nature of the patent itself is a strategic signal. Is it a foundational composition-of-matter patent protecting the core molecule? Is it a new method-of-use patent, indicating an attempt to expand into new diseases? Is it a formulation patent for a new delivery system (e.g., changing from a tablet to an injectable)? Or is it a process patent for a more efficient manufacturing method? Each type reveals a different strategic intent, from initial discovery to market expansion to defending against generic competition.

This level of analysis allows a company to move beyond simple observation and begin to reverse-engineer a competitor’s entire R&D and lifecycle management strategy. Imagine a competitor’s initial patent for a new oral tablet mentions significant challenges with the drug’s solubility and details the various enhancers they tested to overcome this. This reveals a potential weakness in their first-generation product. If, a few years later, the same competitor files a new set of patents focused on a novel liquid formulation or a long-acting injectable version of the same drug, the strategic picture becomes crystal clear. The competitor is actively developing a next-generation, “evergreening” product designed to address the limitations of the original and extend their franchise dominance beyond the initial patent cliff.

This intelligence is strategic gold. It allows your company to make two critical moves. First, you can potentially target the known weakness (e.g., poor solubility, dosing inconvenience) of their current product in your own marketing and clinical development. Second, and more importantly, you can initiate R&D on your own next-generation competitor years before their new product is ever publicly announced, shifting your entire strategic posture from reactive to proactive.

Pipeline Reconnaissance and White Space Analysis

The power of patent intelligence extends beyond individual products to mapping the entire competitive landscape. Because patent applications are typically published 18 months after their initial filing, systematic monitoring provides a powerful early warning system for emerging competitive threats, often years before those threats appear in clinical trial databases or at scientific conferences.

By aggregating and analyzing all patent filings within a specific therapeutic area, a company can create a detailed “patent landscape.” This landscape can reveal:

- Who the key players are and the intensity of their research activity.

- What technologies and mechanisms of action are trending.

- Where the “white space” is—that is, therapeutic targets, delivery technologies, or combination therapies with limited patent coverage, representing potential opportunities for development with less competition.

This analysis can guide every aspect of strategy, from internal R&D project prioritization to in-licensing and M&A activity. By linking patent families to specific pipeline products, an analyst can track a competitor’s progress from the preclinical stage all the way to launch. It is even possible to identify “stealth programs”—projects with significant patent activity but no public disclosure—giving you a glimpse into a competitor’s secret pipeline.

Advanced Brand Franchise Strategies

As companies become more sophisticated, they use naming and branding as a central part of their franchise strategy, especially for molecules with broad potential.

A masterclass in this approach is the dual-brand strategy employed by Novo Nordisk for its molecule semaglutide. Instead of launching it under one name, they created two distinct brands: Ozempic for Type 2 diabetes and Wegovy for obesity.60 This was a brilliant strategic move. It allowed them to create tailored marketing campaigns, messaging, and even pricing structures for two very different patient populations and reimbursement environments. The “empowerment” narrative of Ozempic could be targeted at diabetes patients, while the “partnership in weight loss” story of Wegovy could be directed at the obesity market. This level of market segmentation and targeted branding would have been impossible to achieve with a single brand name.

Another area of advanced strategy lies in the world of biologics and biosimilars. In the United States, the FDA now requires that all new biologics and their biosimilar competitors have a unique, four-letter, meaningless suffix attached to their nonproprietary name (e.g., the reference biologic is infliximab, and a biosimilar is infliximab-dyyb). The stated purpose of this policy is to improve pharmacovigilance by making it easier to track which specific product a patient received. However, this is a highly contentious issue. Innovator companies often support the distinct suffixes, arguing they are critical for safety. Biosimilar manufacturers, on the other hand, argue that the suffixes create an artificial perception of difference in the minds of physicians and patients, which could hinder the uptake of lower-cost biosimilars and protect the innovator’s market share. Navigating this complex naming convention is now a core strategic consideration for any company operating in the biologics space.

Case Studies in Naming: Triumphs and Tribulations

Theories and strategies are best understood when seen in action. The stories behind some of the world’s most famous drug names provide invaluable lessons in the art and science of pharmaceutical branding, showcasing how a name can define a market, overcome competitive challenges, and become a cultural phenomenon.

Viagra (sildenafil): Creating a Category, Breaking a Taboo

The story of Viagra is a classic tale of scientific serendipity meeting marketing genius. The compound, sildenafil, was originally developed by Pfizer in the late 1980s as a potential treatment for angina (chest pain).63 During early clinical trials, it showed little promise for the heart, but male participants began reporting a surprising and consistent side effect: improved erections. Pfizer’s researchers quickly recognized they had stumbled upon a potential blockbuster for a completely different condition.

The challenge was immense. Erectile dysfunction was a taboo subject, shrouded in stigma. The brand needed a name that was not only medically credible but also empowering and accessible enough to bring the conversation into the mainstream. The name they created, Viagra, was a masterstroke. It was crafted to evoke powerful, positive concepts: vigor, vitality, and the flow of Niagara Falls.20 Some have even noted its phonetic resonance with the Sanskrit word

vyaghra, meaning “tiger”. The name was strong, confident, and aspirational.

The branding extended to the product’s physical form. The team initially proposed a five-sided shield shape for the tablet, but this was rejected by regulators as being “too phallic”.65 In a moment of inspired adaptation, the team simply knocked one side off the design, creating the iconic, trademarked “little blue pill” in its distinctive diamond shape. The synergy between the powerful name and the unique visual identity was electric. When Viagra launched in 1998, it did more than just treat a medical condition; it created a new market, transformed a sensitive issue into a global lifestyle conversation, and became what

Newsweek called the “hottest new drug in history”.

Lipitor (atorvastatin): Dominating a Crowded Market

Unlike Viagra, which created a market, Lipitor had to fight its way to the top of an already crowded one. When Pfizer launched atorvastatin in 1997, it was the fifth “me-too” statin to enter the fiercely competitive cholesterol-lowering market, facing established players like Merck’s Zocor and Bristol-Myers Squibb’s Pravachol.

Its strategy for dominance was built on two pillars: superior efficacy and brilliant branding. The name Lipitor was a key part of this strategy. It was simple, professional, and directly communicated the drug’s benefit to its target audience of physicians. The name is a clear and effective portmanteau of “lipid” and “inhibitor,” instantly signaling its mechanism of action.30

This scientifically grounded name was then backed by one of the largest and most successful marketing campaigns in pharmaceutical history. The campaign centered on the drug’s superior LDL-cholesterol-lowering ability compared to its rivals. As generic competitors began to emerge, the marketing shifted to a message of authenticity and inimitableness, famously captured by the tagline, “Only Lipitor is Lipitor”. The brand became so powerful that even after its patent expired, it retained a significant market share, demonstrating how a well-chosen name, coupled with a relentless marketing strategy, can build an enduring commercial fortress.

Ozempic & Wegovy (semaglutide): A Masterclass in Market Segmentation

The most recent and perhaps most sophisticated naming case study is that of Novo Nordisk’s semaglutide. The molecule, a GLP-1 receptor agonist, showed immense promise for two distinct, though often related, conditions: Type 2 diabetes and obesity.68 Instead of launching one product for both, Novo Nordisk made the bold strategic decision to create two separate brands, a classic dual-brand strategy designed to maximize market penetration.60

Working with the naming agency Addison Whitney, they developed two unique brand identities, each tailored to a specific patient journey and psychological mindset.

For the Type 2 diabetes indication, they created Ozempic. The name was constructed to be strong and hopeful. The “O” was a nod to the circular journey of management, the “zem” was a direct phonetic link to the generic name semaglutide, “emp” suggested patient empowerment, and “pic” evoked the idea of reaching a peak of health or picking the best treatment.

For the obesity indication, they created Wegovy. This name was designed to be a partner in the weight loss journey. The “we” immediately suggests partnership and can also hint at weight. The “go” implies action and movement, and the “vy” ending provides a pleasant phonetic cadence. The underlying message, as described by the agency, was “weight goes away”.

This dual-name strategy has been a resounding success. It has allowed Novo Nordisk to run completely separate, highly targeted marketing campaigns. The “Oh, oh, oh, Ozempic” jingle has become a cultural touchstone for diabetes treatment, while Wegovy’s marketing can focus squarely on the benefits of weight management and improved cardiovascular health. This case study is a perfect illustration of the modern art of pharmaceutical naming, where a single molecule can be given multiple identities to conquer multiple markets.

Conclusion: The Synthesis of Science, Art, and Strategy

The journey of a drug’s name, from a complex chemical string to a household brand, is a microcosm of the modern pharmaceutical industry itself. It is a process defined by a fundamental duality: the rigorous, rule-based science of generic nomenclature and the creative, high-stakes art of proprietary branding. We have seen how these two worlds, while distinct in their methods, are inextricably linked by the overarching imperatives of patient safety and commercial success.

The creation of a generic name through the harmonized efforts of the USAN Council and the WHO’s INN Programme is a triumph of global cooperation. This standardized lexicon, built on the logical foundation of the stem system, is the bedrock of safe prescribing and the engine of the generic drug market. Yet, as we have explored, for the strategic analyst, it is also much more. The timing of a USAN application and the choice of a stem are among the earliest public signals of a competitor’s pipeline, offering a precious window of predictive intelligence.

Conversely, the crafting of a brand name is a high-wire act of creativity, psychology, and risk management. It is a funnel of viability where thousands of ideas are systematically culled by legal, linguistic, and market-based pressures. The ultimate goal is to forge a unique and enduring commercial asset, an identity that can drive market share and command loyalty for decades. This creative process, however, is tightly constrained by the regulatory gauntlets of the FDA and EMA, whose mandates to protect patients from confusion and misleading claims serve as the ultimate arbiters of a name’s fate. The ever-present threat of Look-Alike, Sound-Alike errors, underscored by the sobering history of post-market name changes, makes patient safety the non-negotiable foundation upon which all naming decisions must be built.

Ultimately, the most successful pharmaceutical companies are those that have moved beyond viewing naming as a final, tactical step before launch. They understand that it is an integral part of their commercial and competitive intelligence strategy from the earliest stages of a drug’s development. They leverage patent data not just as a legal shield, but as a strategic blueprint to reverse-engineer competitor R&D and anticipate future market shifts. They see every naming decision as an opportunity to build value, mitigate risk, and position their products for dominance. The name on the bottle, therefore, is far more than a simple label. It is the embodiment of years of research, a critical tool for patient safety, a powerful commercial asset, and a clear window into the strategic heart of the company that created it. Mastering the comprehensive science and art of drug naming is, and will continue to be, essential for thriving in the complex and competitive landscape of modern medicine.

Key Takeaways

- Generic Names are Early Intel: The USAN/INN stem and application timing are among the earliest public signals of a competitor’s R&D pipeline and strategic direction. Monitor these filings to gain a predictive edge.

- Brand Naming is a High-Risk, High-Reward Endeavor: With regulatory rejection rates as high as 55% at the EMA, relying on specialized naming agencies and a rigorous, data-driven screening process is not a luxury—it is essential for risk management.

- LASA Risk is a Commercial Catastrophe: The financial and reputational damage of a post-market name change due to medication errors is immense. Upfront investment in comprehensive safety testing, including real-world simulations, provides a massive return on investment by preventing these failures.

- Patents are a Strategic Blueprint: Go beyond viewing patents as mere legal documents. Analyze competitor patents to reverse-engineer their R&D processes, predict their next-generation products, and identify “white space” opportunities in the market. Use dedicated services like DrugPatentWatch to systematize this intelligence gathering.

- Dual-Branding is a Power Play: For molecules with multiple distinct indications (e.g., diabetes and obesity), a dual-brand strategy allows for highly targeted marketing, pricing, and market access that can unlock significantly more value than a single brand.

- Strategy Starts Early: The most effective naming processes begin in Phase I or II of clinical trials. They should be deeply integrated with the company’s broader competitive intelligence, brand strategy, and lifecycle management plans, not treated as an isolated, last-minute task.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. Why do so many new drug names sound so strange or use letters like ‘X,’ ‘Z,’ and ‘Q’?

This is a direct result of the “crowded” nature of the pharmaceutical lexicon and the strict rules against name confusion. As thousands of drug names have been trademarked and approved, it has become increasingly difficult to find names that are unique and do not sound or look like existing ones. To create this necessary distinction, naming agencies and pharmaceutical companies often turn to less common letters like ‘X,’ ‘Z,’ ‘Q,’ and ‘J’. These letters create a unique phonetic and orthographic signature, making the name more memorable and less likely to be confused with another during prescribing or dispensing. A name like Xeljanz or Pristiq is intentionally designed to stand out in a crowded field.

2. If a generic drug is chemically identical to the brand-name version, why do companies spend millions on creating and defending a brand name?

The brand name is a long-term commercial asset that, unlike a patent, does not expire. Pharmaceutical companies invest heavily in branding for several reasons:

- Building Trust and Loyalty: Through marketing, companies aim to build trust with physicians and patients, associating the brand name with quality, reliability, and the positive outcomes of the original clinical trials.

- Differentiation: The brand name is the primary tool for differentiating their product from competitors, even those in the same drug class.

- Post-Patent Value: After a patent expires, many generic versions of the drug will enter the market. A strong brand name can lead to “brand loyalty,” where doctors continue to prescribe and patients continue to request the original brand, even if it is more expensive than the generic alternatives. This helps the innovator company retain significant market share and revenue long after losing exclusivity.19

- Marketing Focus: It is far easier and more effective to build a marketing campaign and a memorable story around a unique name like “Lipitor” than around the more clinical generic name “atorvastatin”.

3. What is the single biggest mistake a company can make in the drug naming process?

The single biggest mistake is underestimating the importance of early and comprehensive safety testing for Look-Alike, Sound-Alike (LASA) potential. While regulatory and trademark hurdles are significant, a failure in safety can have the most catastrophic consequences. A name that repeatedly causes medication errors can lead to patient harm or death, resulting in devastating lawsuits, immense reputational damage, and the ultimate commercial disaster: a forced post-market name change.50 Companies that cut corners on safety screening or fall in love with a “creative” name without rigorously testing it in real-world simulations (handwriting, verbal orders, etc.) are taking an unacceptable risk.

4. How can a smaller biotech company with a limited budget effectively navigate the complex and expensive naming process?

While large pharma companies have vast resources, smaller biotechs can navigate the process strategically:

- Start Early: Time is a valuable resource. Begin the naming process in early Phase II to allow ample time for review and to address any potential issues without rushing before a product launch.

- Focus on a “Global-Ready” Name: Concentrate resources on developing a single name that is viable in key markets (US and EU) from the outset, rather than developing multiple regional names. This involves early linguistic and regulatory checks for both jurisdictions.

- Leverage Expert Consultation Wisely: While hiring a top-tier naming agency for the full process may be costly, smaller companies can engage them for specific, high-value services, such as the final safety and regulatory risk assessment of a few top candidate names.

- Prioritize Safety Over Marketing Flair: A smaller company’s first priority should be a name that is unequivocally safe and approvable. A simple, clear, and distinct name that sails through regulatory review is far more valuable than a “creative” but risky name that gets rejected, causing costly delays.

- Use Competitive Intelligence: Smaller companies can use affordable and accessible tools, like those offered by DrugPatentWatch, to monitor the competitive and patent landscape, helping them to choose a strategic “white space” for their name without needing a massive internal analytics department.

5. With the rise of AI, how is the process of drug naming likely to change in the next 5-10 years?

Artificial intelligence is already beginning to augment the drug naming process and its role is expected to grow significantly. Here’s how:

- Accelerated Ideation: AI algorithms can generate thousands of potential names in minutes, based on specific phonetic, linguistic, and strategic parameters. This can rapidly expand the initial pool of candidates for human creatives to refine.2

- Enhanced Screening: AI will revolutionize the screening process. AI-powered tools can conduct preliminary trademark and linguistic checks across global databases with incredible speed and accuracy. Most importantly, advanced AI, including natural language processing and image recognition, can be trained to perform more sophisticated POCA-like analyses and even simulate handwriting recognition to flag potential LASA conflicts with a higher degree of predictive accuracy.59

- Predictive Analytics: AI can analyze vast datasets of past naming successes and failures to predict the likelihood of a new name being rejected by a specific regulatory body like the FDA or EMA. This could help companies better allocate resources to names with the highest probability of success.

- Human-AI Collaboration: AI will not likely replace human creativity and strategic judgment but will become a powerful partner. The future of naming will involve a symbiotic relationship where AI handles the massive data processing and initial screening, freeing up human experts to focus on the nuanced strategic, psychological, and cultural aspects of building a global brand.

References

- Course – Drug Discovery Case Studies, accessed August 4, 2025, https://drugdiscovery.jhu.edu/our-courses/drug-discovery-case-studies/

- Why Do Prescription Drugs Have Such Crazy Names? | Global Health NOW, accessed August 4, 2025, https://globalhealthnow.org/2024-07/why-do-prescription-drugs-have-such-crazy-names

- How Are New Drugs Named? The Process Explained! – Absolute Awakenings, accessed August 4, 2025, https://absoluteawakenings.com/how-are-new-drugs-named-the-process-explained/

- The Comprehensive Science and Art of Pharmaceutical Drug Naming – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-comprehensive-science-and-art-of-pharmaceutical-drug-naming/

- How Do Drugs Get Named? | Journal of Ethics | American Medical Association, accessed August 4, 2025, https://journalofethics.ama-assn.org/article/how-do-drugs-get-named/2019-08

- Drug nomenclature – Wikipedia, accessed August 4, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Drug_nomenclature

- Overview of Generic Drugs and Drug Naming – Drugs – Merck Manual Consumer Version, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.merckmanuals.com/home/drugs/brand-name-and-generic-drugs/overview-of-generic-drugs-and-drug-naming

- Guidance on INN – Health products policy and standards, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.who.int/teams/health-product-and-policy-standards/inn/guidance-on-inn

- International Nonproprietary Names (INN) – Drugs.com, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.drugs.com/inn.html

- Sildenafil: MedlinePlus Drug Information, accessed August 4, 2025, https://medlineplus.gov/druginfo/meds/a699015.html

- Sildenafil – Wikipedia, accessed August 4, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sildenafil

- Atorvastatin: Uses, Interactions, Mechanism of Action | DrugBank Online, accessed August 4, 2025, https://go.drugbank.com/drugs/DB01076

- Atorvastatin – Wikipedia, accessed August 4, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Atorvastatin

- International Non-proprietary Names – Medsafe, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.medsafe.govt.nz/profs/riss/inn.asp

- Generic Drugs: Questions & Answers | FDA, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/frequently-asked-questions-popular-topics/generic-drugs-questions-answers

- www.humana.com, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.humana.com/pharmacy/medication-information/difference-between-generic-and-brand-drug#:~:text=A%20generic%20drug%20is%20a,brand%2Dname%20drug’s%20patent%20expires.

- Pharmaceutical Branding: A Comprehensive Guide to Building a …, accessed August 4, 2025, https://alltimedesign.com/pharmaceutical-branding-a-comprehensive-guide-to-building-a-successful-pharmaceutical-brand/

- Pharmaceutical Industry Quotes – Goodreads, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.goodreads.com/quotes/tag/pharmaceutical-industry

- The adverse effects of brand-name drug prescribing – PMC, accessed August 4, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3307571/

- Naming Medication: How Do Drugs Get Their Names? – Pfizer, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.pfizer.com/news/articles/part_2_what_s_in_a_brand_name_how_drugs_get_their_names

- International nonproprietary name – Wikipedia, accessed August 4, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/International_nonproprietary_name

- Procedure for USAN name selection – American Medical Association, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.ama-assn.org/about/united-states-adopted-names-usan/procedure-usan-name-selection

- Ever Wonder How Drugs Are Named? Read On – Pfizer, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.pfizer.com/news/articles/ever_wonder_how_drugs_are_named_read_on

- Pharmacology Cheat Sheet: Generic Drug Stems – Nurseslabs, accessed August 4, 2025, https://nurseslabs.com/common-generic-drug-stem-cheat-sheet/

- International Nonproprietary Names (INN) for novel vaccine substances: A matter of safety, accessed August 4, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8625196/

- Cooley – Guide to Successful Drug Naming, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.cooley.com/-/media/cooley/pdf/practices/cooley—guide-to-successful-drug-naming.ashx

- Ever Wonder How Drugs Get Their Names? – Pfizer, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.pfizer.com/news/behind-the-science/ever-wonder-how-drugs-get-their-names

- The name that gave rise to a billion dollar category – Interbrand, accessed August 4, 2025, https://interbrand.com/health/work/the-name-that-gave-rise-to-a-billion-dollar-category/

- The Origins of 5 Well Known Drug Names – Pharma IQ, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.pharma-iq.com/pre-clinical-discovery-and-development/articles/the-origins-of-5-well-known-drug-names

- Lipitor: How does this statin affect cholesterol levels? – Medical News Today, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/248136

- “For Me There Is No Substitute”: Authenticity, Uniqueness, and the Lessons of Lipitor, accessed August 4, 2025, https://journalofethics.ama-assn.org/article/me-there-no-substitute-authenticity-uniqueness-and-lessons-lipitor/2010-10

- World’s Leading Pharmaceutical Branding and … – Brand Institute, accessed August 4, 2025, https://brandinstitute.com/worlds-leading-pharmaceutical-branding-and-naming-company-brand-institute/

- Pharmaceutical Branding & Naming Services – Brandsymbol, accessed August 4, 2025, https://brandsymbol.com/pharmaceutical-branding/

- Healthcare Naming & Brand Identity – Syneos Health, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.syneoshealth.com/solutions/commercial-delivery/syneos-health-communications/healthcare-naming-brand-identity

- Inside the Pharma Name Game: Drug Word Choice Key to Building a Lasting Identity, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.pharmexec.com/view/inside-the-pharma-name-game-drug-word-choice-key-to-building-a-lasting-identity

- What’s in a Name? For Prescription Drugs, Both Art and Science – Cobalt Communications, accessed August 4, 2025, https://cobaltcommunications.com/cobalt-60/whats-in-a-name-for-prescription-drugs-both-art-and-science/

- Pharmaceutical Brand Strategy – Orientation Marketing, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.orientation.agency/insights/pharmaceutical-brand-strategy

- Drug Name Review | FDA, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/fda-drug-info-rounds-video/drug-name-review

- SOPP 8001.4: Review of Proprietary Names for CBER Regulated Products – FDA, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/media/95529/download

- Brand Name Approvals for Medicinal Products in the European Union: A Vital Part of Drug Safety, accessed August 4, 2025, https://brandinstitute.com/brand-name-approvals-for-medicinal-products-in-the-european-union-a-vital-part-of-drug-safety/

- The State Agency of Medicines guideline for the naming of …, accessed August 4, 2025, https://ravimiamet.ee/state-agency-medicines-guideline-naming-medicinal-products

- Guideline on the acceptability of names for human medicinal … – EMA, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/guideline-acceptability-names-human-medicinal-products-processed-through-centralised-procedure-scientific-guideline

- Naming of human medicinal products | Swedish Medical Products Agency, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.lakemedelsverket.se/en/laws-and-regulations/guidelines/guideline-on-labelling-package-leaflets-and-naming-of-human-medicinal-products/naming-of-human-medicinal-products

- Exploring the Possibility of Proprietary Name Reservation for Drug Products; Establishment of a Public Docket – Federal Register, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2014/07/28/2014-17691/exploring-the-possibility-of-proprietary-name-reservation-for-drug-products-establishment-of-a

- Medication Errors Related to Look-Alike, Sound-Alike Drugs—How Big is the Problem and What Progress is Being Made? – Anesthesia Patient Safety Foundation, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.apsf.org/article/medication-errors-related-to-look-alike-sound-alike-drugs-how-big-is-the-problem-and-what-progress-is-being-made/

- Medication Errors Linked to Drug Name Confusion Advisory, accessed August 4, 2025, https://patientsafety.pa.gov/ADVISORIES/Pages/200412_07.aspx

- Quick Safety Issue 26: Transitions of Care: Managing medications (Updated April 2022), accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.jointcommission.org/en-us/knowledge-library/newsletters/quick-safety/issue-26

- Retrospective Analysis of Look-alike and Sound-alike Drug Incidents in a Tertiary Care Hospital – Indian Journal of Pharmacy Practice, accessed August 4, 2025, https://ijopp.org/files/IndJPharmPract-14-2-114.pdf

- Look-alike, sound-alike medication perioperative incidents in a regional Australian hospital: assessment using a novel medication safety culture assessment tool – Oxford Academic, accessed August 4, 2025, https://academic.oup.com/intqhc/article/37/1/mzaf018/8051336

- 5 Notable Drug Name Changes – Pharmacy Times, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.pharmacytimes.com/view/5-notable-drug-name-changes

- Chapter 6. The Role of Drug Names in Medication Errors – PharmacyLibrary, accessed August 4, 2025, https://pharmacylibrary.com/doi/10.21019/9781582120928.ch6

- FDA: Brand Name Confusion Led to Dozens of Medication Errors – RAPS, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.raps.org/news-and-articles/news-articles/2015/7/fda-brand-name-confusion-led-to-dozens-of-medicat

- How can clinicians improve medication safety for look-alike and …, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.merative.com/blog/medication-safety-for-look-alike-sound-alike-drugs

- Drug Patent Watch Blog Explains Multi-Stage Naming Process for …, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.geneonline.com/drug-patent-watch-blog-explains-multi-stage-naming-process-for-medications/

- DrugPatentWatch | Software Reviews & Alternatives – Crozdesk, accessed August 4, 2025, https://crozdesk.com/software/drugpatentwatch

- DrugPatentWatch Highlights 5 Strategies for Generic Drug Manufacturers to Succeed Post-Patent Expiration – GeneOnline News, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.geneonline.com/drugpatentwatch-highlights-5-strategies-for-generic-drug-manufacturers-to-succeed-post-patent-expiration/

- Cracking the Code: Using Drug Patents to Reveal Competitor …, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/cracking-the-code-using-drug-patents-to-reveal-competitor-formulation-strategies/

- How to Track Competitor R&D Pipelines Through Drug Patent …, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/how-to-track-competitor-rd-pipelines-through-drug-patent-filings/

- Using Patent Filings to Model Branded Pharmaceutical Post-Expiration Strategies, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/using-patent-filings-to-model-branded-pharmaceutical-post-expiration-strategies/

- Dual Naming: Ozempic + Wegovy – Novo Nordisk – Addison Whitney, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.addisonwhitney.com/case-studies/dual-naming-ozempic-wegovy/

- The Ozempic Dilemma: What makes a dual-brand approach viable? | Articles | CRA, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.crai.com/insights-events/publications/the-ozempic-dilemma-what-makes-a-dual-brand-approach-viable/

- Naming Convention, Interchangeability, and Patient Interest in Biosimilars – PMC, accessed August 4, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7428664/

- Sildenafil: Uses, Interactions, Mechanism of Action | DrugBank Online, accessed August 4, 2025, https://go.drugbank.com/drugs/DB00203

- Viagra’s Journey to Blockbuster Patent and the Single Journal Article It Cites – ACS Axial, accessed August 4, 2025, https://axial.acs.org/medicinal-chemistry/viagra-s-journey-to-blockbuster-patent-and-the-single-journal-article-it-cites

- How Viagra Got Its Name | Viagra: The Little Blue Pill that Changed the World | discovery+, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fuiolyVjoj8

- How “Viagra” Got Its Name And Blue Diamond Shape|Viagra: The Little Blue Pill That Changed The World – YouTube, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bk9MnyCPMCc&pp=0gcJCfwAo7VqN5tD

- About LIPITOR® (atorvastatin calcium) tablets, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.lipitor.com/en/about-lipitor

- Semaglutide: Uses, Dosage, Side Effects, Brands – Drugs.com, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.drugs.com/semaglutide.html

- Semaglutide – Wikipedia, accessed August 4, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Semaglutide

- How Novo Nordisk intends to make Wegovy as well-known as Ozempic – Marketing Brew, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.marketingbrew.com/stories/2024/09/03/how-novo-nordisk-intends-to-make-wegovy-as-well-known-as-ozempic