In the high-stakes world of pharmaceutical innovation, the term “patent cliff” looms large—a precipice where blockbuster drugs lose their market exclusivity, and revenues can plummet by as much as 80-90% in the first year of generic competition.1 With over $200 billion in annual revenue at risk through 2030 for industry titans like AbbVie’s Humira and Merck’s Keytruda, the strategic extension of a drug’s patent life has evolved from a legal formality into a cornerstone of corporate survival and growth.3 For decades, the primary tool for this extension—the Patent Term Extension (PTE)—was viewed through a narrow lens, seen largely as a reward reserved for the discovery of a truly novel drug, a New Chemical Entity (NCE).

This perspective is now dangerously outdated.

Welcome to the new frontier of market exclusivity. The most sophisticated and successful pharmaceutical and biotech companies no longer view PTE as a static prize for a new molecule. Instead, they wield it as a dynamic, strategic lever applicable across a broad and diverse spectrum of innovations. This includes not just NCEs, but also complex biologics, next-generation cell and gene therapies, novel drug-device combinations, innovative formulations, and fixed-dose combination therapies that represent the cutting edge of patient care.

The very definition of “innovation” worthy of extended protection has expanded. Regulatory bodies and courts have gradually, and sometimes grudgingly, acknowledged that a breakthrough is not limited to the initial discovery of an active pharmaceutical ingredient (API). Significant value—and therefore, an incentive for investment—also lies in the incremental yet crucial advancements that follow: a new formulation that improves patient compliance, a delivery system that enhances bioavailability, or a combination of existing drugs that creates a new standard of care. These are the innovations that often make a promising molecule a truly effective and commercially viable medicine.

This evolution is a direct response to the brutal economics of drug development. A standard 20-year patent term is a mirage. The reality is that a decade or more of that term is consumed by the grueling gauntlet of preclinical research, multi-phase clinical trials, and rigorous regulatory review by agencies like the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).6 This “lost time” dilemma means a drug may launch with as little as 7 to 10 years of effective market exclusivity, a perilously short window to recoup an investment that can exceed $1-2 billion.8 PTE is the statutory mechanism designed to correct this imbalance, to restore a portion of the time sacrificed at the altar of regulatory compliance.10

The expansion of PTE eligibility to these non-NCE products has created a powerful feedback loop. As the legal system rewards these diverse forms of innovation with extended exclusivity, it further incentivizes companies to invest in them. This shift has profound implications for R&D pipelines, patient outcomes, and the competitive landscape. However, it also walks a fine line, igniting fierce debates about “evergreening”—the controversial practice of using secondary patents and extensions to prolong monopolies and delay the entry of more affordable generics.9

This report will serve as your definitive guide to navigating this complex and evolving landscape. We will begin by deconstructing the foundational U.S. law, 35 U.S.C. § 156, to build a rock-solid understanding of its mechanics. From there, we will embark on a deep dive into the specific eligibility criteria and strategic considerations for biologics, new formulations, new therapeutic uses, and combination products. We will then expand our lens globally, conducting a rigorous comparative analysis of the U.S. PTE system against the European Union’s Supplementary Protection Certificate (SPC) regime and Japan’s uniquely flexible PTE framework. We will step into the courtroom to dissect the landmark cases that have shaped—and are still shaping—the rules of the game. Finally, we will bring these insights into the boardroom, translating complex legal doctrine into actionable strategies for R&D planning, portfolio management, and securing a decisive competitive advantage.

The Cornerstone of U.S. Exclusivity: Deconstructing Patent Term Extension under 35 U.S.C. § 156

To master the art of extending market exclusivity, you must first master the foundational legal instrument that makes it possible in the United States. Patent Term Extension is not a discretionary prize; it is a statutory right governed by a complex but logical set of rules codified in Title 35, Section 156 of the U.S. Code.13 Understanding this statute—its history, its mechanics, and its limitations—is the first and most critical step in building a robust lifecycle management strategy.

The Hatch-Waxman Act: A Grand Bargain Revisited

The story of PTE begins with the Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984, better known as the Hatch-Waxman Act.15 This landmark legislation represented a “grand bargain,” a carefully orchestrated compromise designed to solve two competing problems that were distorting the pharmaceutical market.10

On one side, innovator companies faced the “lost time” dilemma. The lengthy, FDA-mandated regulatory review process was eroding the effective life of their patents, sometimes leaving them with only a few years of market exclusivity to recoup massive R&D investments.7 This created a powerful disincentive for innovation. On the other side, the process for generic drugs to enter the market was slow and cumbersome, requiring them to repeat expensive and time-consuming clinical trials. This kept drug prices high long after patents had expired, straining healthcare budgets and limiting patient access.

Hatch-Waxman addressed both issues simultaneously. For the generics industry, it created the Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) pathway, allowing them to rely on the innovator’s safety and efficacy data to gain approval, dramatically speeding up market entry. In exchange for this new competitive threat, the Act gave innovator companies the Patent Term Extension.10 This provision was designed to restore a portion of the patent term lost during the FDA’s premarket review, thereby preserving the economic incentive for the high-risk, high-cost work of developing new medicines.18 This dual-sided solution remains the fundamental architecture of the U.S. pharmaceutical market today.

The Nuts and Bolts: Core Eligibility Requirements for PTE

At its core, 35 U.S.C. § 156(a) lays out five clear conditions that a patent must meet to be eligible for extension. Think of these as five gates you must pass through; failure at any one of them is fatal to your application.10

- The Patent Must Be Active: The patent for which you are seeking an extension must not have expired before your PTE application is submitted.10 This underscores the importance of timely filing.

- No Prior Extensions: A patent’s term can only be extended once under this section.10 This is a “one-bite-at-the-apple” rule. Furthermore, only one patent can be extended for any given product’s regulatory review period.10 If a company has multiple patents covering an approved drug, it must choose which one to extend—a critical strategic decision.

- A Timely and Proper Application: The application must be submitted by the owner of record of the patent (or their agent) and must comply with all procedural requirements.10 As we will see, the timing of this application is ruthlessly strict.

- Subject to Regulatory Review: The product claimed in the patent must have been subject to a “regulatory review period” before it could be commercially marketed or used.10 This is the foundational requirement that links the extension to the delay it is meant to compensate for.

- First Permitted Commercial Use: The regulatory approval must be the “first permitted commercial marketing or use of the product”.10 This is, without question, the most important and most heavily litigated of the five conditions. The interpretation of the word “product” in this context is the central battleground that determines whether PTE is available for new formulations, new uses, and combination therapies, a topic we will explore in exhaustive detail later in this report.

It’s also crucial to understand what types of patents can be extended. The statute is broad, applying to any patent that claims a “product, a method of using a product, or a method of manufacturing a product”.13 This breadth is what opens the door for extending protection beyond a simple composition of matter patent for an NCE, potentially covering patents on new indications (a method of use) or novel manufacturing processes.

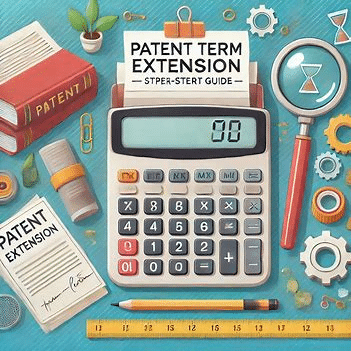

The Application and Calculation Process: A Procedural Gauntlet

Navigating the PTE application process is a high-stakes procedural duet between the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) and the FDA. Missteps can be costly and irreversible.

First and foremost is the 60-day clock. A PTE application must be submitted to the USPTO within 60 days of the product’s FDA approval date.6 This is one of the strictest deadlines in all of U.S. patent law; it is non-extendable, and there is no recourse for missing it. Once the application is filed, the USPTO reviews it for formal compliance and then forwards it to the FDA. The FDA’s role is to determine the length of the regulatory review period and certify it back to the USPTO.6

The calculation of the extension period itself is governed by a specific formula that balances the time spent in clinical testing with the time spent under active FDA review, all while being constrained by statutory caps.8 The formula is:

PTE=21(Testing Phase)+(Approval Phase)

- The Testing Phase is the period beginning on the date an Investigational New Drug (IND) application becomes effective and ending on the date a marketing application (like a New Drug Application (NDA) or Biologics License Application (BLA)) is submitted to the FDA.11 The innovator only gets credit for half of this time.

- The Approval Phase is the period from the NDA/BLA submission until the date of FDA approval.11 The innovator gets full credit for this time.

However, this calculated period is subject to two critical limitations that often dictate the final extension granted:

- The 5-Year Maximum: The total extension period cannot exceed five years.1 Even if the formula yields a result of seven years, the extension will be capped at five.

- The 14-Year Cap: The total remaining patent term after the extension is added cannot be more than 14 years from the date of the product’s FDA approval.11 This cap is a manifestation of Congress’s intent to provide a “reasonable” but not unlimited period of market exclusivity. If a patent already has 13 years of life remaining on the day of FDA approval, the maximum PTE it can receive is one year, regardless of how long the regulatory review took. This makes the timing of the initial patent filing a crucial strategic variable.

The Scope of the Extended Right: A Critical Limitation

A common and dangerous misconception is that PTE extends the entire original patent. It does not. The rights granted during the extension period are significantly narrower than the rights during the original patent term.

As stipulated in 35 U.S.C. § 156(b), the extension applies only to the specific approved product and its approved uses.6 Imagine a patent with broad claims covering a class of compounds (A, B, and C). The company develops and receives FDA approval only for compound A. The PTE will restore the patent term, but the exclusive rights during that extended period will be limited solely to compound A for its approved indications. Competitors would be free to make, use, and sell compounds B and C for any purpose as soon as the

original 20-year patent term expires.6

This narrowing of scope is a fundamental part of the Hatch-Waxman compromise. It allows the innovator to protect the specific asset that required the lengthy and expensive regulatory review, while simultaneously releasing related but unapproved technology into the public domain sooner. This fosters “design-around” innovation by competitors and prevents the extension from locking up an entire field of research. For patent holders, this means that a broad patent becomes a highly focused, rifle-shot right during the PTE period, a fact that must be factored into any enforcement or licensing strategy.

The Evolving Definition of “Product”: Opening the Door for Non-NCE Patent Term Extensions

The gateway to patent term extension for any innovation beyond a classic NCE is guarded by a single, deceptively simple phrase in the statute: the requirement that the regulatory approval be the “first permitted commercial marketing or use of the product”. For years, a restrictive interpretation of “product” as being synonymous with the “active ingredient” slammed this gate shut for most follow-on innovations. If the active ingredient had been approved before, any new formulation or use was, by definition, not the “first.”

However, a series of nuanced regulatory interpretations and landmark court decisions have pried this gate open. The legal system has begun to recognize that the true “product” undergoing regulatory review is often more than just its core molecule. This evolving understanding has created distinct pathways—some wide, some narrow—for securing PTE for a new generation of advanced medicines.

Biologics and Advanced Therapies: Defining the “Active Ingredient” in a New Era

While human biological products are explicitly included in the statutory definition of a “drug product” eligible for PTE, applying the law to these complex therapies has been a major challenge.16 The central problem? Defining the “active ingredient” when the product is not a static chemical but a living cell or a piece of genetic code.

This issue came to a head with the PTE application for YESCARTA® (axicabtagene ciloleucel), a revolutionary CAR-T cell therapy for B-cell lymphomas. The therapy involves harvesting a patient’s own T-cells, genetically engineering them to express a Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR) that targets cancer cells, and then reinfusing them into the patient. The USPTO initially balked at the PTE application, raising two critical objections:

- The cells themselves could not be the active ingredient because they are autologous and thus differ from patient to patient.

- The CAR construct was not adequately defined as an active ingredient in the application.

This challenge threatened to undermine the availability of PTE for an entire class of personalized medicines. The resolution was pivotal. The patent holder, Kite Pharma (a Gilead company), successfully argued that the true, consistent “active ingredient” was not the variable cell but the transduced viral vector containing the specific anti-CD19 CAR gene sequence. This was the novel, uniform technological component responsible for the therapy’s effect. The USPTO ultimately accepted this argument and granted the PTE.

The YESCARTA case sets a vital precedent. It signals that for advanced therapies, the definition of “active ingredient” can be flexible, focusing on the core inventive component—be it a gene sequence, a CAR construct, or another novel biological element—rather than the cellular vehicle. This provides a critical pathway for innovators in the rapidly advancing fields of cell and gene therapy to recoup their development time. The framework also extends to veterinary biologics, demonstrating the statute’s broad applicability across the life sciences sector.16

New Formulations and Delivery Systems: Rewarding Patient-Centric Innovation

Patents on new formulations of existing drugs exist in a state of perpetual tension. Critics often label them as “evergreening”—a cynical tactic to obtain secondary patents on trivial modifications to block lower-cost generics.2 Proponents, however, argue that they represent valuable “incremental innovation” that can dramatically improve a drug’s safety, efficacy, or patient compliance—for example, by moving from a twice-daily pill to a once-weekly injection.

When it comes to PTE, the “first permitted use” requirement remains a formidable barrier. Because the “product” is generally defined as the “active ingredient,” and that ingredient has been previously approved, a new formulation is almost always considered a subsequent approval, making it ineligible for PTE.25

However, a crucial exception exists for drug-device combination products. Here, the innovation is not just in the drug’s formulation but in the integrated system used to deliver it. If a novel delivery device—like a specialized inhaler or a pre-filled auto-injector—is integral to the product and requires its own data for regulatory approval, the “product” being reviewed by the FDA is the entire combination.

A key case study involves an inhaler device for an asthma medication that received a PTE. The extension was granted not because the active ingredient was new (it wasn’t), but because the innovative device design, which improved drug delivery and patient usability, was a core part of the FDA’s regulatory review. The PTE was based on the approval of the entire system.

This creates a clear strategic directive. While a simple extended-release tablet of an old drug is highly unlikely to secure a PTE in the U.S., a more complex product that integrates a drug with a novel, patented delivery technology stands a much stronger chance. This incentivizes a shift in R&D focus from simple reformulations to more technologically advanced, patient-centric delivery systems.

New Therapeutic Uses: The Untapped Potential of Drug Repurposing

Discovering a new use for an existing drug—often called drug repurposing or repositioning—is a highly efficient and cost-effective R&D strategy. It leverages known safety profiles to address unmet medical needs more quickly and cheaply than developing an NCE from scratch. The statute explicitly allows for PTE on patents claiming a “method of using a product,” which would seem to be the perfect tool to incentivize the expensive clinical trials needed to get a new indication approved.13

Unfortunately, the “first permitted use” hurdle proves just as challenging here as it does for new formulations. The prevailing interpretation by the USPTO and the courts is that if the “product” (the active ingredient) has been previously approved for any indication, a subsequent approval for a new indication is not the “first” approval of that product. This makes obtaining a PTE for a repurposed drug a significant uphill battle in the U.S.

While some continue to argue for a broader interpretation—that the “product” should be considered the combination of the active ingredient and its new use—this has not gained widespread legal traction. The more common and successful strategy for protecting a repurposed drug is to secure a new, strong patent on the method of use for the new indication and rely on that patent’s natural 20-year term, rather than attempting to extend an older composition of matter patent.

“Incremental innovation in pharmaceuticals can lead to substantial improvements in treatment efficacy, patient compliance, and overall healthcare outcomes. These advancements deserve recognition through patent term extensions.”

— Dr. Sarah Johnson, Pharmaceutical Patent Expert

Combination Products: The “One New Ingredient” Rule

For fixed-dose combination (FDC) products—pills that contain two or more active ingredients—the rules for PTE eligibility in the U.S. are refreshingly clear, having been solidified by Federal Circuit case law. A combination product is eligible for PTE if it meets a two-pronged test 17:

- At least one of the active ingredients in the combination must be new. It must be an NCE or a new salt/ester that has never been previously approved by the FDA.

- The patent for which the extension is sought must claim that newly-approved active ingredient.

Conversely, a new combination product where all of the active ingredients have been previously approved in other products is not eligible for PTE. This is true even if the combination produces a powerful synergistic effect that makes it far more effective than its individual components. The courts have explicitly stated that synergy, while clinically important, is irrelevant to the PTE eligibility analysis. This rule was established in cases that rejected PTE for new combinations of well-known drugs, cementing a pragmatic, substance-based approach.

Drug-device combinations represent a special category. The FDA may review them primarily as a drug or primarily as a device. The PTE statute is flexible, allowing the product to be classified as either for the purpose of determining eligibility. The critical factor is that the entire integrated product undergoes a single, unified regulatory review.17 This provides a viable PTE pathway for products that pair an older drug with a novel device, as the regulatory delay is associated with the approval of the complete system.

The legal battles over these non-NCE categories all hinge on the interpretation of the word “product.” A clear trend has emerged: the legal standard adapts to the nature of the technology. For traditional small molecules, the “product” is strictly the active ingredient, creating a high bar. For advanced biologics like CAR-T, the definition has become more sophisticated, focusing on the novel technological driver. For integrated drug-device systems, the “product” can be the entire combination. This provides a strategic roadmap for innovators: the more technologically distinct and integrated your non-NCE innovation is, the stronger your case for PTE eligibility becomes.

A Global Gauntlet: Comparing PTE Strategies in the U.S., EU, and Japan

A successful lifecycle management strategy cannot be confined to a single market. The three largest pharmaceutical markets—the United States, the European Union, and Japan—each have their own unique systems for extending patent life. While they share the same overarching goal of compensating innovators for regulatory delays, their legal frameworks, eligibility criteria, and strategic implications are profoundly different. A “one-size-fits-all” global strategy is not just suboptimal; it is a recipe for failure. Understanding these differences is essential for maximizing the global value of a pharmaceutical asset.

Table 1: U.S. PTE vs. EU SPC vs. Japan PTE – A Comparative Snapshot

This table provides a critical, at-a-glance reference for global IP strategists. It distills the complex rules of the three most important pharmaceutical markets into a digestible format, allowing for quick comparison of the core mechanics and eligibility criteria that drive global lifecycle management decisions.

| Feature | United States (PTE) | European Union (SPC) | Japan (PTE) |

| Nature of Right | Extension of the original patent term | A separate, sui generis (unique) IP right that takes effect after patent expiry 8 | Extension of the original patent term 32 |

| Legal Basis | 35 U.S.C. § 156 (Hatch-Waxman Act) | Regulation (EC) No 469/2009 34 | Japanese Patent Act, Article 67 36 |

| Maximum Extension | 5 years 8 | 5 years (plus 6-month pediatric extension) 30 | 5 years 32 |

| Total Exclusivity Cap | 14 years from FDA approval 8 | Generally 15 years from first EU marketing authorization (15.5 with pediatric extension) 8 | No cap 27 |

| # of Patents Extended per Product | Only one patent per regulatory review 10 | Only one “basic patent” per product | Multiple patents can be extended for the same approved product 27 |

| Eligibility for New Uses | Challenging; generally no if active ingredient was previously approved. | No, following CJEU ruling in Santen 38 | Yes, subsequent approvals for new indications can form the basis for new extensions 27 |

| Eligibility for New Formulations | Challenging; generally no if active ingredient was previously approved. | No, following CJEU ruling in Abraxis | Yes, subsequent approvals for new formulations, dosages, etc., can form the basis for new extensions 32 |

| Eligibility for Combination Products | Yes, if at least one active ingredient is new. | Complex; requires the combination itself to be the “invention” of the patent (Teva/Merck test) 42 | Yes, even if all active ingredients were previously approved, if the combination is novel |

The European Union’s Supplementary Protection Certificate (SPC): A Different Beast

The EU’s system is fundamentally different from that of the U.S. A Supplementary Protection Certificate (SPC) is not a simple extension of a patent. It is a sui generis—or unique—intellectual property right that is legally distinct from the patent on which it is based. It springs into existence the day after the “basic patent” expires, effectively tacking on an additional period of exclusivity.8

Historically, the SPC system has been fragmented. An innovator must file for and obtain a separate SPC in each EU member state where they hold a patent and have a marketing authorization, a process that is costly, administratively burdensome, and can lead to divergent outcomes across the Union.45 To address this, the European Commission has proposed a major reform to create a centralized examination procedure and a “unitary SPC” that would provide uniform protection across all participating member states, complementing the new Unitary Patent system.34

Another key feature of the EU regime is the SPC manufacturing waiver. Introduced in 2019, this provision was a significant concession to the generics and biosimilars industry. It allows EU-based manufacturers to produce a generic or biosimilar version of an SPC-protected medicine during the SPC term, provided the product is exclusively for export to countries where protection has expired or never existed. It also allows for stockpiling of the product in the final six months of the SPC term to facilitate a “day 1” launch within the EU the moment the SPC expires.34 This waiver aims to bolster the competitiveness of European generic manufacturers on the global stage, but it represents a notable erosion of the innovator’s exclusivity compared to the U.S. system.

Japan’s PTE System: The Innovator’s Paradise?

On nearly every point where the U.S. and EU systems are restrictive, Japan’s PTE framework is remarkably flexible and innovator-friendly. This makes Japan a critical, and often underestimated, jurisdiction for building a global patent fortress.

The key advantages of the Japanese system are threefold 27:

- Multiple Patent Extensions: In the U.S. and EU, only one patent can be extended for a given approved product. In Japan, an innovator can extend the term of all patents covering the approved drug. This could include a patent on the active ingredient, a separate patent on the formulation, another on a method of use, and even one on the manufacturing process—all extended based on a single regulatory approval.

- Multiple Extensions per Patent: This is perhaps the most significant difference. The same patent can be extended multiple times. If a company first gets approval for a drug for one indication, it can get a PTE. If, years later, it secures approval for a new indication, a new dosage, or a new formulation of that same drug, it can file for another PTE on the same patent.32 This directly rewards the kind of incremental, lifecycle-extending R&D that is explicitly

not rewarded with extensions in the U.S. and EU. - No Overall Exclusivity Cap: Japan does not impose the 14- or 15-year caps on total market exclusivity found in the U.S. and EU.27 While each individual extension is capped at five years, the total effective protection period can be significantly longer.

The trade-off for this extraordinary flexibility is a narrower scope of protection during the extended term. In Japan, the extended patent right is strictly limited to the working of the patented invention for the product as approved—meaning for the specific ingredients, dosage, administration, and indication listed in the marketing approval that formed the basis for the extension.

These profound differences are not accidental; they reflect divergent policy priorities. The U.S. system is designed to reward the introduction of a new active substance to the market. The EU’s system, as shaped by its judiciary, aims to reward the core invention of the basic patent. Japan’s system, in contrast, is designed to incentivize all clinical R&D that results in a new, approved therapeutic option for patients. This means a global pharmaceutical company cannot have a uniform lifecycle strategy. The value of a new formulation in the pipeline is dramatically different depending on the target market: in Japan, it could be the key to a five-year extension; in the U.S. and EU, it is likely worth nothing in terms of extended exclusivity. This reality forces a geographically segmented approach to R&D, M&A, and commercial launch sequencing.

The Gavel and the Globe: Landmark Court Rulings You Cannot Ignore

Statutes provide the blueprint for patent term extension, but it is in the courtroom where the lines are drawn and the rules are truly defined. A handful of landmark decisions from the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit and the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) have fundamentally shaped the modern PTE and SPC landscape. Ignoring these precedents is like navigating a minefield blindfolded; understanding them is essential for crafting resilient and effective IP strategies.

U.S. Federal Circuit: Forging a Pragmatic Path

The Federal Circuit, as the specialized appellate court for patent matters in the U.S., has generally taken a pragmatic, text-based approach to interpreting 35 U.S.C. § 156. Its key decisions have provided crucial clarity on the definition of a “product.”

- PhotoCure ASA v. Kappos (2010): This case was a turning point. Before PhotoCure, the USPTO often used the term “active moiety”—the core molecule responsible for a drug’s action—to determine eligibility. The Federal Circuit rejected this, holding that the statute’s plain language refers to the “active ingredient,” which is the specific substance present in the final, approved drug product. This decision tightened the eligibility criteria, making it more difficult to obtain PTE for different salt forms or esters if a related version of the active ingredient had already been approved.

- Ortho-McNeil Pharmaceutical, Inc. v. Lupin Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (2010): In a significant win for innovators, the court addressed the issue of enantiomers—mirror-image versions of a chiral molecule. It affirmed the long-standing practice of the FDA and USPTO to treat a single enantiomer (like escitalopram in Lexapro) as a “different” drug product from the racemate (a 50/50 mixture of both enantiomers, like citalopram in Celexa). This ruling confirmed that developing a purified, more effective enantiomer of an existing racemic drug was an innovative step worthy of its own PTE.

- Merck Sharp & Dohme B.V. v. Aurobindo Pharma USA, Inc. (2025): This very recent decision tackled a complex but important procedural question concerning reissued patents. A patent can be “reissued” to correct errors, and the question was whether the PTE calculation should start from the issue date of the original patent or the later reissue date. The court held that the clock starts with the original patent’s issue date.53 This was a major victory for patent holders, ensuring that the corrective process of reissue does not inadvertently penalize them by shortening the potential length of their patent term extension.

The Court of Justice of the EU (CJEU): A Restrictive and Unifying Doctrine

In stark contrast to the Federal Circuit, the CJEU has acted as a powerful centralizing force in Europe, issuing a series of highly influential—and often highly restrictive—rulings. The court has consistently interpreted the SPC Regulation narrowly, with a clear focus on preventing the extension of monopolies beyond what it deems the core purpose of the legislation.

- Abraxis Bioscience (C-443/17): The End of the Line for New Formulations. This was a devastating blow to lifecycle management strategies based on formulation improvements. The CJEU held that an SPC cannot be granted for a new formulation (in this case, Abraxane®, a nanoparticle albumin-bound version of paclitaxel) of an active ingredient that had already received a marketing authorization. The court reasoned that the “product” is strictly the active ingredient itself, and the “first authorisation” is the first time that ingredient was ever approved, regardless of its formulation.

- Santen (C-673/18): Overturning Precedent on New Uses. In an even more dramatic move, the CJEU used the Santen case to explicitly overturn the interpretation of its own decade-old precedent from Neurim. The court ruled that an SPC is not available for a new therapeutic use of a previously authorized product.38 This decision effectively closed the door on obtaining SPCs for repurposed drugs in the EU, a strategy that many companies had been pursuing.

- Boston Scientific (C-527/17): No SPCs for Drug-Device Combinations. The CJEU took a rigidly literal approach to the SPC Regulation, which applies to “medicinal products.” It held that a drug-eluting stent, which is regulated as a “medical device,” is not eligible for an SPC, even though it incorporates a medicinal substance that undergoes a form of regulatory assessment.56 This created a clear dividing line, denying extended protection to a major class of innovative combination products.

- Teva/Merck (C-119/22 & C-149/22): The New “Invention Test” for Combination Products. This recent and complex ruling established a high bar for obtaining SPCs for fixed-dose combinations. The CJEU declared that it is not enough for the basic patent to simply mention the combination of active ingredients (e.g., A+B). To be eligible for an SPC, the combination itself must be the core invention covered by the patent. The patent must demonstrate that the combination is required to solve the technical problem it addresses, for example, by providing data showing an unexpected synergistic effect.42 This “invention test” makes it significantly harder to get SPCs for combinations in the EU compared to the more straightforward “one new ingredient” rule in the U.S.

The CJEU’s judicial activism reveals a clear trend: it is systematically harmonizing SPC law across the EU, but in a restrictive direction. It is closing perceived loopholes and tying SPC eligibility ever more tightly to the core inventive concept of the basic patent and the absolute first marketing authorization of an active ingredient. This creates a challenging and uncertain environment for innovators, placing a massive premium on drafting the “basic patent” with extraordinary foresight.

The differing approaches of the U.S. Federal Circuit and the EU’s CJEU reflect their distinct institutional philosophies. The Federal Circuit often appears more focused on the commercial realities of the Hatch-Waxman compromise, while the CJEU is more concerned with the doctrinal purpose of the SPC Regulation within the broader context of the EU single market. This divergence means that legal outcomes are highly jurisdiction-dependent, reinforcing the absolute necessity of bespoke, region-specific IP strategies.

From Law to Lifecycles: Leveraging PTE for Competitive Advantage

Understanding the intricate statutes and landmark court cases is only half the battle. The true measure of an expert is the ability to translate that legal knowledge into a tangible competitive advantage. Patent term extension is not a passive, administrative task to be checked off a list after a drug is approved. It is an active, strategic weapon that should be integrated into every phase of a product’s lifecycle, from the earliest stages of R&D to the final defense against the patent cliff.

Integrating PTE into R&D and Portfolio Strategy

The biggest mistake a company can make is to wait until the 60-day filing window opens to think about PTE. By then, the most critical strategic decisions have already been made, and opportunities may have been irrevocably lost. A forward-thinking organization embeds PTE considerations into its R&D and portfolio management processes from day one.

- Early-Stage Candidate Selection: When evaluating multiple lead candidates, their potential for PTE eligibility in key markets should be a weighted factor. A candidate that is a true NCE has a clear path in all jurisdictions. A candidate that is a new enantiomer has a strong case in the U.S. A candidate that is part of a novel combination with an existing drug has a clear path in the U.S. but a very difficult one in the EU. These considerations can and should influence which molecules are advanced into costly clinical development.

- The Strategic Value of Incrementalism: While the term “evergreening” carries negative connotations, pursuing genuine, clinically meaningful incremental innovation is a valid and powerful business strategy. The key is to focus R&D resources on the types of innovations that have a clear pathway to extended exclusivity in target markets. This means prioritizing:

- Combination products that pair a novel agent with an established one to leverage the U.S. “one new ingredient” rule.

- Advanced drug-device combinations where the device is novel and requires an integrated regulatory review, creating a strong PTE case in the U.S.

- New formulations, new dosages, and new indications specifically for the Japanese market, where such innovations are explicitly rewarded with new PTEs.

- Due Diligence in M&A and Licensing: For business development teams, a target’s PTE potential is a critical and often overlooked valuation metric. A deep, nuanced understanding of the global rules is essential to accurately price an asset. A biotech with a promising repurposed drug may look attractive, but its potential for extended exclusivity is near zero in the EU and challenging in the U.S., a fact that must be reflected in its net present value (NPV) calculation. Conversely, a company with a strong patent portfolio in Japan might be undervalued if the acquirer fails to appreciate the potential for multiple, overlapping PTEs.

The Role of Competitive Intelligence: Using Data to Win

The PTE and SPC landscape is not static. It is a dynamic battlefield shaped by new approvals, new filings, and ongoing litigation. To succeed, you must have a clear and continuous view of your competitors’ strategies.

This is where sophisticated competitive intelligence platforms like DrugPatentWatch become indispensable. These tools transform raw patent and regulatory data into actionable strategic intelligence. A company can leverage DrugPatentWatch to :

- Monitor Competitor Filings: Track the filing and status of rival PTE and SPC applications in real-time. This provides an early warning system, revealing which of your competitors’ products will have extended market exclusivity and for how long.

- Track Litigation: Keep a close watch on legal challenges to granted PTEs and SPCs. A successful challenge by a generic company can dramatically alter the competitive landscape, creating an unexpected market entry opportunity for others.

- Forecast the Patent Cliff: Build highly accurate models of patent expiration dates that account for granted and potential extensions. This allows for precise forecasting of generic and biosimilar entry, which is critical for financial planning and resource allocation.

- Identify Strategic Trends: Analyze which types of innovations are successfully securing extensions in which jurisdictions. If competitors are consistently winning PTEs for a certain class of drug-device combinations, it may signal a promising area for your own R&D efforts.

The goal is to move from a reactive, defensive posture to a proactive, offensive one. This intelligence allows you to file the right patents in the right countries, strategically challenge competitors’ weak extensions, and build business models based on a realistic and data-driven assessment of market exclusivity periods.

Building a Global PTE/SPC Fortress: A Holistic Approach

Maximizing patent life in the modern global environment requires a holistic and integrated approach. The old model of siloed departments—where R&D invents, regulatory approves, and legal files—is no longer sufficient.

- The Integrated Team: Success demands seamless collaboration between patent attorneys, regulatory affairs specialists, and commercial teams. The way a product is defined in its BLA or NDA submission to the FDA can have profound and irreversible consequences for its PTE eligibility. The regulatory strategy and the IP strategy must be developed in lockstep.

- Jurisdiction-Specific Patent Drafting: A patent is not a generic document. Applications should be drafted with the specific PTE and SPC requirements of each major jurisdiction in mind. A patent intended to support an SPC for a combination product in the EU may need to include more explicit data on synergy to satisfy the Teva/Merck “invention test” than a corresponding application filed in the U.S.

- Lifecycle Management as a Continuous Process: Ultimately, patent term extension is the capstone of a multi-decade lifecycle management strategy. It is the final, crucial step in maximizing the return on an immense investment of time and capital. It is the primary defense against the inevitable patent cliff.3 By embracing a sophisticated, globally-aware, and data-driven approach, companies can transform this complex legal provision into one of their most powerful tools for creating and preserving value.

Conclusion and Strategic Imperatives

The landscape of pharmaceutical patent term extension has irrevocably shifted. The once-dominant paradigm, focused almost exclusively on New Chemical Entities, has given way to a more complex and nuanced reality where a diverse array of innovations—from biologics and combination products to advanced delivery systems—can achieve extended market exclusivity. However, this expansion of opportunity has been accompanied by a dramatic fragmentation of the global legal framework. The paths to extension in the United States, the European Union, and Japan have diverged, reflecting fundamentally different policy priorities and judicial philosophies.

Success in this new era is no longer about simply filing the right form at the right time. It is about embedding a deep, strategic understanding of these global intricacies into the very DNA of a pharmaceutical organization. It requires a proactive, forward-looking approach that transforms intellectual property from a defensive shield into an offensive weapon for value creation and competitive advantage.

Based on the exhaustive analysis in this report, three strategic imperatives emerge for any company seeking to master the art of lifecycle management:

- Integrate Early and Often: The consideration of patent term extension cannot be an afterthought. It must be a critical input at the earliest stages of R&D, influencing candidate selection, clinical trial design, and portfolio prioritization. The regulatory and IP strategies must be developed as a single, cohesive plan, not as separate workstreams that converge only at the time of marketing approval.

- Think Globally, Act Locally: A “one-size-fits-all” approach to patenting and lifecycle management is a recipe for leaving billions of dollars on the table. Companies must develop a global IP architecture but execute it with bespoke strategies meticulously tailored to the unique rules and judicial precedents of the U.S., EU, and Japan. The valuation of a pipeline asset, its launch sequence, and its long-term commercial plan must reflect this jurisdictional reality.

- Weaponize Intelligence: In a dynamic and contentious environment, knowledge is power. The continuous monitoring of the legal, regulatory, and competitive landscapes is not a luxury but a necessity. Leveraging advanced tools and data analytics to track competitor filings, monitor litigation, and accurately forecast patent cliffs allows a company to move from a reactive to a proactive stance, turning market intelligence into a decisive strategic advantage.

The companies that embrace these imperatives will be the ones who not only survive the coming patent cliffs but thrive in the new frontier of market exclusivity. They will be the ones who successfully translate the full value of their innovation—in all its forms—into durable market leadership and continued investment in the next generation of life-saving medicines.

Key Takeaways

- PTE is Not Just for NCEs: The U.S., EU, and Japan all provide pathways for extending patent life for non-NCE innovations, but the eligibility criteria differ dramatically.

- The U.S. “One New Ingredient” Rule: In the U.S., a combination product is eligible for PTE if at least one of its active ingredients is new to the market.

- The EU’s Restrictive Stance: The EU’s high court (CJEU) has effectively barred SPCs for new uses (Santen) and new formulations (Abraxis) of previously approved drugs and has imposed a strict “invention test” for combination products (Teva/Merck).

- Japan’s Unmatched Flexibility: Japan offers the most innovator-friendly system, allowing multiple patents to be extended for one product and allowing the same patent to be extended multiple times for new indications or formulations.

- “Product” Definition is Key: The legal interpretation of the term “product” is the central battleground for PTE eligibility, with different standards emerging for small molecules, biologics, and drug-device combinations.

- Strategy Must Be Jurisdiction-Specific: A “one-size-fits-all” global IP strategy is doomed to fail. The valuation of a pipeline asset and its lifecycle plan must be tailored to the specific rules of each major market.

- Case Law is Dynamic: The legal landscape is constantly being shaped by court decisions. Staying abreast of the latest rulings from the U.S. Federal Circuit and the EU’s CJEU is critical for risk management and strategy.

- Competitive Intelligence is Power: Using platforms like DrugPatentWatch to monitor competitor PTE/SPC activity and litigation is essential for building accurate forecasts and identifying strategic opportunities.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. Can a patent that has been terminally disclaimed to overcome a double-patenting rejection still receive a patent term extension in the U.S.?

Yes. This is a crucial and often misunderstood point. The Federal Circuit has held that a statutory grant of PTE under 35 U.S.C. § 156 is not overridden by a terminal disclaimer filed during prosecution to obviate a non-statutory double patenting rejection.10 The extension period is calculated and then added to the expiration date set by the terminal disclaimer. This allows companies to pursue robust patent family strategies, such as filing continuation applications to capture different aspects of an invention, without forfeiting the right to a valuable patent term extension on a key patent.

2. If I get an SPC for my drug in Germany, is it automatically effective across the entire EU?

No, not under the current system. Supplementary Protection Certificates are national rights. You must apply for and be granted an SPC in each individual EU member state where you have a corresponding basic patent in force and wish to secure extended protection.30 This fragmented process can lead to different outcomes in different countries. However, the European Commission has proposed reforms to create a centralized examination procedure and a “unitary SPC” that would provide uniform protection across participating EU member states, which would significantly streamline this process if adopted.34

3. My company has a patent on a new extended-release formulation of a drug that has been on the market for years. Based on the EU’s Abraxis decision, is there any hope for an SPC?

Based on the CJEU’s clear and restrictive ruling in the Abraxis case, the prospects for obtaining an SPC in the EU are extremely low, if not zero. The court held that the “product” for SPC purposes is the active ingredient itself, not its formulation. If that active ingredient has already been the subject of a prior marketing authorization, a subsequent authorization for a new formulation cannot be considered the “first authorization” required by Article 3(d) of the SPC Regulation. The fact that the new formulation is itself novel and patented is, unfortunately, irrelevant for SPC eligibility under current EU case law.

4. In Japan, if I get a PTE for my drug based on its approval for treating hypertension, and two years later I get a new approval for treating heart failure, can I extend my patent again?

Yes, this is a key strategic advantage of the Japanese patent system. Unlike the “one extension per patent” rule in the U.S. and EU, Japan allows for multiple PTEs to be granted on the same patent based on different regulatory approvals.27 As long as the second approval for heart failure can be distinguished from the first approval for hypertension (e.g., by indication, dosage, or formulation), you can file a new PTE application. This could result in a new extension period being granted for your patent, further prolonging its life (subject to the 5-year cap for that specific extension).

5. What is the single biggest mistake companies make when it comes to PTE strategy?

The single biggest mistake is treating patent term extension as a purely administrative, post-approval task. This reactive approach fails to recognize that PTE is a powerful strategic asset whose value is determined by decisions made years, or even a decade, earlier. An effective PTE strategy is not a filing exercise; it is a core component of the entire drug development and commercialization plan. It should influence which patents are filed and how their claims are drafted, which clinical programs are prioritized for investment, how regulatory pathways are designed, and how potential M&A targets are valued. Waiting until the 60-day clock starts ticking after an FDA approval is a failure to leverage one of the most significant tools for value creation and preservation in the pharmaceutical industry.

References

- Drug Patents: Essential Guide to Pharmaceutical Patent Protection – UpCounsel, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.upcounsel.com/how-long-does-a-drug-patent-last

- Strategic Patenting by Pharmaceutical Companies – Should Competition Law Intervene? – PMC, accessed July 30, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7592140/

- The Impact of Patent Cliff on the Pharmaceutical Industry – Bailey Walsh, accessed July 30, 2025, https://bailey-walsh.com/news/patent-cliff-impact-on-pharmaceutical-industry/

- The Impact of Drug Patent Expiration: Financial Implications, Lifecycle Strategies, and Market Transformations – DrugPatentWatch, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-impact-of-drug-patent-expiration-financial-implications-lifecycle-strategies-and-market-transformations/

- Patent Term Extension for Drugs not Limited to new Chemical Entities – DrugPatentWatch, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/patent-term-extension-for-drugs-not-limited-to-new-chemical-entities/

- Introduction to Patent Term Extensions (PTE) – Fish & Richardson, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.fr.com/insights/ip-law-essentials/intro-patent-term-extension/

- The Role of Patent Extensions in Healthcare: Balancing Innovation and Access, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.laxxonmedical.com/post/the-role-of-patent-extensions-in-healthcare-balancing-innovation-and-access

- Understanding Patent Term Extensions: An Overview – DrugPatentWatch, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/understanding-patent-term-extensions-an-overview/

- Patent and Marketing Exclusivities 101 for Drug Developers – PMC – PubMed Central, accessed July 30, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10242760/

- Understanding the Statute on Patent Term Extension – IPWatchdog.com, accessed July 30, 2025, https://ipwatchdog.com/2024/10/28/understanding-statute-patent-term-extension/id=182598/

- Patent Term Extension – Sterne Kessler, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.sternekessler.com/news-insights/insights/patent-term-extension/

- The Role of Patents and Regulatory Exclusivities in Drug Pricing | Congress.gov, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/R46679

- 35 U.S. Code § 156 – Extension of patent term – Law.Cornell.Edu, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/35/156

- Page 74 TITLE 35—PATENTS § 156 – GovInfo, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.govinfo.gov/link/uscode/35/156

- Patent Term Extensions and the Last Man Standing | Yale Law & Policy Review, accessed July 30, 2025, https://yalelawandpolicy.org/patent-term-extensions-and-last-man-standing

- 2750-Patent Term Extension for Delays at other Agencies under 35 U.S.C. 156 – USPTO, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.uspto.gov/web/offices/pac/mpep/s2750.html

- PATENT TERM EXTENSION FOR FDA-APPROVED PRODUCTS – Mayer Brown, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.mayerbrown.com/-/media/files/perspectives-events/publications/2024/04/240410-wdc-webinar-lifesci-successfully-navigating-slides.pdf?rev=537cb0623a9841a1ad320d7e52889377

- Patent Term Extension (PTE): Driving Innovation Forward – Copperpod IP, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.copperpodip.com/post/patent-term-extension-pte-driving-innovation-forward

- The Implications of Patent-Term Extension for Pharmaceuticals, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.princeton.edu/~ota/disk3/1981/8119/811906.PDF

- 2751-Eligibility Requirements – USPTO, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.uspto.gov/web/offices/pac/mpep/s2751.html

- Pharmaceutical Patent Term Extension: An Overview – Alacrita, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.alacrita.com/whitepapers/pharmaceutical-patent-term-extension-an-overview

- The Mechanics of Patent-Term Extension, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.princeton.edu/~ota/disk3/1981/8119/811908.PDF

- Patent Term Extension For Biologics | MoFo Life Sciences – JDSupra, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.jdsupra.com/legalnews/patent-term-extension-for-biologics-4734516/

- Patent Term Extension – usda aphis, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.aphis.usda.gov/sites/default/files/pel_4_11.pdf

- Patent Term Extension Considerations For Regulated Products | Sterne Kessler, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.sternekessler.com/news-insights/insights/patent-term-extension-considerations-regulated-products/

- Patent Term Extension and the Active Ingredient Problem, accessed July 30, 2025, https://jipel.law.nyu.edu/patent-term-extension-and-the-active-ingredient-problem/

- Q&A: Patent term extension at a glance | Managing Intellectual Property, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.managingip.com/article/2a5bqtj8ume32ix5ophc0/q-a-patent-term-extension-at-a-glance

- Patent Term Extension for Drugs Not Limited to New Chemical Entities, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.troutman.com/insights/patent-term-extension-for-drugs-not-limited-to-new-chemical-entities.html

- 2753-Application Contents – USPTO, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.uspto.gov/web/offices/pac/mpep/s2753.html

- European Supplementary Protection Certificates (SPCs) for Pharmaceuticals – Gill Jennings & Every LLP, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.gje.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/European-Supplementary-Protection-Certificates-SPCs-for-pharmaceuticals-A-practical-guide-2022.pdf

- Supplementary Protection Certificates – Hlk-ip.com, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.hlk-ip.com/knowledge-hub/supplementary-protection-certificates-additional-protection-for-regulated-products/

- Patent Term Extension (PTE), accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.siks.jp/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Patent_Term_Extension.pdf

- Overview of the Patent Term Extension in Japan – KAWAGUTI & PARTNERS, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.kawaguti.gr.jp/aboutlaw/jp_practices/01_1.html

- Supplementary protection certificates for pharmaceutical and plant protection products – European Commission – Internal Market, Industry, Entrepreneurship and SMEs, accessed July 30, 2025, https://single-market-economy.ec.europa.eu/industry/strategy/intellectual-property/patent-protection-eu/supplementary-protection-certificates-pharmaceutical-and-plant-protection-products_en

- Revision of the Supplementary Protection Certificate Regulations for medicinal and plant protection products – European Parliament, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2023/740258/EPRS_BRI(2023)740258_EN.pdf

- 4 The System for Registration of Extension of the Duration of Patent Rights of Pharmaceuticals or the like and the Appropriate Operation Thereof, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.iip.or.jp/e/summary/pdf/detail2014/e26_04.pdf

- New Ruling on Scope of Protection of Extended Patent Rights in JAPAN, accessed July 30, 2025, https://allegropat.com/extension-pharmaceutical-patent-japan/

- Europe: CJEU holds supplementary protection certificate s not …, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.globalcompliancenews.com/2020/08/03/europe-cjeu-holds-spcs-not-available-for-new-therapeutic-applications-of-authorised-products-20200727/

- New CJEU ruling on supplementary protection certificate for second medical use products, accessed July 30, 2025, https://kromannreumert.com/en/news/new-cjeu-ruling-on-supplementary-protection-certificate-second-medical-use-products

- SPCs: new formulations of previously marketed … – D Young & Co, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.dyoung.com/en/knowledgebank/articles/spc-new-formulations

- New Examination Guidelines for Patent Term Extension|News …, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.aoyamapat.gr.jp/en/news/1380

- CJEU’s Ruling on the SPC Regulation and Combination SPCs – Hannes Snellman, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.hannessnellman.com/news-and-views/blog/cjeus-ruling-on-the-spc-regulation-and-combination-spcs/

- National courts apply the CJEU’s “invention test” for combination …, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.jakemp.com/knowledge-hub/national-courts-apply-the-cjeus-invention-test-for-combination-spcs-and-differ-in-their-application/

- Pharma companies get some clarity on SPCs for combination products – Pinsent Masons, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.pinsentmasons.com/out-law/news/pharma-companies-get-some-clarity-spcs-combination-products

- Supplementary protection certificates (SPCs) – Initiative details – European Union, accessed July 30, 2025, https://ec.europa.eu/info/law/better-regulation/have-your-say/initiatives/13353-Medicinal-&-plant-protection-products-single-procedure-for-the-granting-of-SPCs_en

- Explanatory Memorandum to COM(2023)231 – Supplementary protection certificate for medicinal products (recast) – EU monitor, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.eumonitor.eu/9353000/1/j4nvhdfdk3hydzq_j9vvik7m1c3gyxp/vm2lhx5hh2yb

- Q&A on the Supplementary Protection Certificates – European Commission, accessed July 30, 2025, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/el/QANDA_23_2455

- Changes proposed in Europe for Supplementary Protection Certificates and the creation of a unitary SPC – ABG IP, accessed July 30, 2025, https://abg-ip.com/european-unitary-spc/

- Supplementary protection certificates – Efpia, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.efpia.eu/about-medicines/development-of-medicines/intellectual-property/supplementary-protection-certificates/

- Supplementary protection certificate for medicinal products: Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) – Nederlandse Grondwet, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.denederlandsegrondwet.nl/id/vkoqg1ogmuxo/nieuws/supplementary_protection_certificate_for

- Supplementary Protection Certificates – Meissner Bolte, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.meissnerbolte.com/fileadmin/user_upload/pdf/broschueren/supplementary_protection_ceritifcates.pdf

- Protection beyond 20 years: data on SPCs and other term extensions for pharmaceutical patents | epo.org, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.epo.org/en/searching-for-patents/helpful-resources/patent-knowledge-news/protection-beyond-20-years-data-spcs

- Federal Circuit Affirms Patent Term Extension Calculation – The National Law Review, accessed July 30, 2025, https://natlawreview.com/article/whats-reissue-patent-term-extensions-reissue-patents

- Federal Circuit: Patent Term Extension for Reissued Patents is Calculated Using the Original Patent’s Issue Date Where the Original Patent Covers the Drug Product – Akin Gump, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.akingump.com/en/insights/blogs/ip-newsflash/federal-circuit-patent-term-extension-for-reissued-patents-is-calculated-using-the-original-patents-issue-date-where-the-original-patent-covers-the-drug-product

- Merck Sharp & Dohme B.V. v. Aurobindo Pharma USA, Inc. – U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.cafc.uscourts.gov/opinions-orders/23-2254.OPINION.3-13-2025_2481365.pdf

- No Supplementary Protection Certificates for drug-device …, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.stevens-bolton.com/site/insights/articles/no-spcs-for-drugdevice-combinations

- European Union Court of Justice rules on SPCs for medical devices, accessed July 30, 2025, https://abg-ip.com/publication-first-office-action-related-supplementary-protection-certificate-application/

- Drug Patent Life: The Complete Guide to Pharmaceutical Patent …, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/how-long-do-drug-patents-last/

- yalelawandpolicy.org, accessed July 30, 2025, https://yalelawandpolicy.org/patent-term-extensions-and-last-man-standing#:~:text=The%20Hatch%2DWaxman%20Act%20allows,a%20conservatively%20estimated%20%2453.6%20billion.

- What is a Patent Term Extension and How Do I Get One? – Whitcomb Selinsky PC, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.whitcomblawpc.com/business-law-blog/patent-term-extension

- Use of patent term extensions to restore regulatory time for medical devices in the United States – PubMed, accessed July 30, 2025, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38831711/

- Understanding Patent Term Extensions in Different Countries – PatentPC, accessed July 30, 2025, https://patentpc.com/blog/understanding-patent-term-extensions-in-different-countries

- Patent Term Extensions and Adjustments – Loc, accessed July 30, 2025, https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/service/ll/llglrd/2016296552/2016296552.pdf

- Patent term extension and test data protection obligations: identifying the gap in policy, research, and practice of implementing free trade agreements – Oxford Academic, accessed July 30, 2025, https://academic.oup.com/jlb/article/10/2/lsad017/7210272