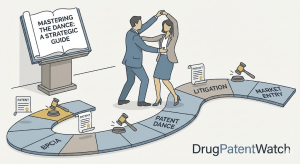

The launch of a biosimilar is not merely a scientific achievement; it is the culmination of a complex, multi-year strategic campaign. At the heart of this campaign lies a uniquely American legal construct: the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA) and its intricate, often misunderstood, pre-litigation framework colloquially known as the “patent dance.” This is no simple two-step. It is a high-stakes chess match, a complex choreography of disclosures, deadlines, and strategic decisions where a single misstep can cost billions in revenue or delay market access for years.

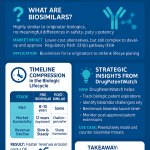

The financial stakes are staggering. Biologic drugs, while accounting for a mere 2% of all prescriptions in the United States, command a breathtaking 37% of net drug spending.1 As blockbuster biologics approach their patent cliffs, the global biosimilar market is projected to surge from $34.8 billion in 2024 to an estimated $93.1 billion by 2030.2 For biosimilar developers, who invest an average of $100 million to $250 million over seven to eight years to bring a product to market, capturing a piece of this prize is essential for survival.1 For the incumbent reference product sponsors, protecting these multi-billion-dollar revenue streams is a paramount corporate objective.

This report is not a simple recitation of the BPCIA’s statutory text. It is a strategic deep dive designed for the sophisticated audience on the front lines of this battle: the IP, R&D, and business development teams at pharmaceutical and biotech companies, the law firms that advise them, and the investors who fund them. We will move beyond the “what” of the patent dance to explore the “why” and the “how”—dissecting the strategic calculus behind every move, from the initial decision to engage in the dance to the final litigation and settlement negotiations. We will ground this analysis in hard data, landmark court decisions, and real-world case studies to provide a definitive guide for turning the complexities of the biosimilar patent timeline into a tangible competitive advantage.

The Legislative Backdrop: Why Biologics Needed Their Own Dance Floor

To truly master the patent dance, one must first understand why it was created. The BPCIA did not emerge in a vacuum; it was a direct legislative response to a unique scientific reality that the existing framework for generic drugs, the Hatch-Waxman Act, was ill-equipped to handle. The very nature of biologics demanded a new set of rules.

More Than a Recipe: The Scientific Complexity of Biologics

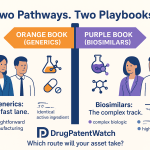

Pharmaceutical drugs fall into two broad categories: small-molecule chemical compounds and large-molecule biologics. Small-molecule drugs, like aspirin, are synthesized through predictable chemical processes and have relatively simple, well-defined structures. A generic version can be proven to be chemically identical to the original.

Biologics, in stark contrast, are a world apart. They are vast, complex proteins or other macromolecules derived from living systems like bacteria, yeast, or mammalian cell lines.3 Their manufacturing process is not just a recipe; it is an integral part of the final product. Minor, almost imperceptible changes in the cell line, the nutrient media, or the purification conditions can result in structural differences in the final molecule.3 This has led to the industry mantra: “the process is the product”.5

Because of this inherent variability, a follow-on biologic can never be an identical copy of the reference product. Instead, the goal is to demonstrate that it is “highly similar” with “no clinically meaningful differences” in safety, purity, and potency.6 This fundamental scientific distinction is the bedrock upon which the entire BPCIA is built. It explains why we have “biosimilars” and not “biogenerics,” and why a simple chemical equivalency test is insufficient.

This scientific reality has profound implications for intellectual property. If the process defines the product, then patenting the intricate methods of manufacturing becomes just as critical—if not more so—than patenting the molecule itself. This is a significant departure from the small-molecule world, where the final chemical structure is often the primary focus of IP protection. As we will see, the BPCIA’s requirement for a biosimilar applicant to disclose its confidential manufacturing process during the patent dance is not an incidental detail; it is a direct challenge to the heart of the reference product sponsor’s IP fortress, making the decision to disclose a moment of immense strategic weight.

The Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA) of 2009

Enacted as part of the Affordable Care Act in 2010, the BPCIA was Congress’s attempt to thread a difficult needle: to create a pathway for lower-cost biosimilars to enter the market while preserving the powerful incentives for innovator companies to continue investing in the research and development of new, life-saving biologics.3

The Act established two key pillars to achieve this balance:

- An Abbreviated Approval Pathway: Modeled loosely on the Hatch-Waxman Act, the BPCIA created the abbreviated Biologics License Application (aBLA) pathway.5 This allows a biosimilar developer to gain FDA approval by demonstrating biosimilarity to an approved reference product, leveraging the originator’s extensive and costly clinical trial data on safety and efficacy. This drastically reduces the time and expense of development compared to a standalone BLA for a novel biologic.

- Robust Exclusivity Periods for Innovators: To reward the massive investment required for biologic R&D, the BPCIA grants the reference product a generous 12-year period of market exclusivity, starting from the date of its first FDA licensure.2 During this time, the FDA is prohibited from approving a biosimilar version of that product. Furthermore, a biosimilar applicant is barred from even

filing an aBLA for the first four years of that 12-year period.2

These exclusivity periods create the macro-timeline for biosimilar competition. The patent dance is the micro-process that operates within this timeline. It is the formal mechanism designed to identify and resolve patent disputes that arise after the four-year filing window opens, with the goal of clearing a legal path for the biosimilar to launch as soon as the 12-year exclusivity period expires.

The Choreography in Detail: A Step-by-Step Timeline of the Patent Dance

The BPCIA lays out a highly structured, multi-step process for information exchange and patent dispute resolution. If followed to the letter and using the maximum allotted time, the entire dance, from initial disclosure to the filing of the first lawsuit, can take up to 250 days, or approximately eight months.17 This section provides a granular, step-by-step breakdown of this complex choreography, serving as a technical and strategic reference guide.

The Curtain Rises: Initiation and Initial Disclosures

The dance begins not with a choice, but with a regulatory milestone: the FDA’s acceptance of the biosimilar applicant’s aBLA for review. This event starts the clock on the first, and arguably most critical, step.

- Step 1. The Applicant’s Opening Move (Day 0 + 20 Days): Within 20 days of receiving notice from the FDA that its aBLA has been accepted, the biosimilar applicant “shall provide” the reference product sponsor (RPS) with a confidential copy of its complete aBLA. The applicant must also provide “such other information that describes the process or processes used to manufacture the biological product”.7 This disclosure is the ticket to the dance floor. It is a moment of profound strategic importance, as it involves handing over highly sensitive and proprietary information to a direct competitor.

The Exchange of Lists: Defining the Battlefield

Once the applicant has made its initial disclosure, the focus shifts to the RPS, who must now lay its patent cards on the table. This begins a series of back-and-forth exchanges designed to identify the specific patents that will form the basis of the dispute.

- Step 2. The RPS’s Patent List (Day 20 + 60 Days): The RPS has 60 days from receiving the aBLA and manufacturing information to provide the applicant with a list of all unexpired patents for which it believes a claim of infringement could reasonably be asserted. The RPS must also identify which, if any, of these patents it would be willing to license.7 This is the RPS’s first opportunity to define the scope of the conflict, and it is often where the intimidating nature of a “patent thicket” is first revealed.

- Step 3. The Applicant’s Rebuttal (Day 80 + 60 Days): The ball is now back in the applicant’s court. Within 60 days, the applicant must respond with a detailed, claim-by-claim statement outlining the factual and legal basis for its position that each patent on the RPS’s list is invalid, unenforceable, and/or not infringed. The applicant may also, at this stage, provide a counter-list of any additional patents it believes could be asserted.7 This is a labor-intensive step that requires the applicant to reveal its core legal and technical defenses.

- Step 4. The RPS’s Sur-Rebuttal (Day 140 + 60 Days): The RPS then has a final 60-day period to provide its own detailed, claim-by-claim rebuttal to the applicant’s invalidity and non-infringement arguments.7 This completes the formal exchange of detailed contentions.

The Negotiation and the First Wave of Litigation

With all arguments on the table, the BPCIA provides a short window for the parties to try and narrow the scope of the impending lawsuit before it is filed.

- Step 5. The Negotiation (Day 200 + 15 Days): The parties are given up to 15 days to “engage in good faith negotiations to agree on a list of patents that shall be the subject of an action for patent infringement”.7 The goal is to focus the initial litigation on the most critical patents, saving time and resources.

This negotiation can lead to two distinct outcomes, each with its own path to the courthouse:

- Step 6a. Litigation by Agreement (Day 215 + 30 Days): If the parties successfully agree on a list of patents, the RPS is then obligated to file an infringement action asserting those specific patents within 30 days of the agreement.7

- Step 6b. Litigation by Disagreement (Day 215 + 5 + 30 Days): If the parties cannot reach an agreement within the 15-day window, a different procedure kicks in. The biosimilar applicant must first notify the RPS of the number of patents it will include on its own litigation list. Then, within 5 days, the parties simultaneously exchange their respective lists of patents they believe should be litigated. The RPS must then file suit within 30 days on all patents included on both lists.7 This mechanism gives the applicant significant control, as it can limit the size of the initial lawsuit by declaring a small number of patents.

The Second Act: Notice of Commercial Marketing and the Second Wave

The first wave of litigation is not the end of the story. The BPCIA creates a second trigger for legal action, tied directly to the biosimilar’s impending market launch.

- Step 7. The 180-Day Notice: The biosimilar applicant “shall provide notice to the reference product sponsor not later than 180 days before the date of the first commercial marketing” of its approved product.17 This notice is mandatory and serves as the starting gun for the second phase of litigation. During this 180-day period, the RPS can seek a preliminary injunction to block the launch based on any patents that were identified during the patent dance (in Step 2) but were

not litigated in the first wave of litigation.7

This intricate, deadline-driven process is summarized in the table below, providing an at-a-glance guide for navigating the dance.

| Step | Action | Responsible Party | Statutory Deadline | Governing Statute |

| 0 | FDA accepts biosimilar’s abbreviated Biologics License Application (aBLA) for review. | FDA | N/A | 42 U.S.C. § 262(l)(1)(A) |

| 1 | Provide RPS with a copy of the aBLA and detailed manufacturing information. | Biosimilar Applicant | Within 20 days of FDA acceptance. | 42 U.S.C. § 262(l)(2)(A) |

| 2 | Provide Applicant with a list of patents that could be infringed and identify any available for license. | Reference Product Sponsor (RPS) | Within 60 days of receiving aBLA. | 42 U.S.C. § 262(l)(3)(A) |

| 3 | Provide RPS with detailed claim-by-claim arguments for non-infringement/invalidity and an optional counter-list of patents. | Biosimilar Applicant | Within 60 days of receiving RPS’s patent list. | 42 U.S.C. § 262(l)(3)(B) |

| 4 | Provide Applicant with a detailed claim-by-claim rebuttal to its non-infringement/invalidity arguments. | Reference Product Sponsor (RPS) | Within 60 days of receiving Applicant’s statement. | 42 U.S.C. § 262(l)(3)(C) |

| 5 | Engage in good faith negotiations to agree on a list of patents for the first wave of litigation. | Both Parties | For a period of 15 days. | 42 U.S.C. § 262(l)(4) |

| 6a | If Agreement Reached: RPS must file an infringement suit on the agreed-upon list of patents. | Reference Product Sponsor (RPS) | Within 30 days of the agreement. | 42 U.S.C. § 262(l)(6)(A) |

| 6b | If No Agreement: Applicant notifies RPS of the number of patents it will list; parties simultaneously exchange lists; RPS files suit on all patents on both lists. | Both Parties | Exchange within 5 days of notice; Suit within 30 days of exchange. | 42 U.S.C. § 262(l)(5) & (l)(6)(B) |

| 7 | Provide RPS with notice of intended commercial marketing. This triggers the second wave of litigation. | Biosimilar Applicant | At least 180 days before first commercial marketing. | 42 U.S.C. § 262(l)(8)(A) |

The Plot Twist: How Sandoz v. Amgen Rewrote the Rules of Engagement

For years, the intricate choreography detailed above was assumed to be a mandatory performance. The statute’s use of the word “shall” seemed to leave no room for improvisation. Then, in 2017, the U.S. Supreme Court took center stage and, in a landmark decision, fundamentally rewrote the script, transforming the patent dance from a rigid sequence into a game of strategic choice.

The Supreme Court’s Landmark Rulings

The case, Sandoz Inc. v. Amgen Inc., arose from Sandoz’s development of Zarxio, a biosimilar to Amgen’s blockbuster biologic Neupogen.23 Sandoz made a bold strategic move: upon receiving FDA acceptance of its aBLA, it notified Amgen but explicitly refused to provide its application and manufacturing data, thereby declining to initiate the patent dance.24 The ensuing legal battle culminated in a unanimous Supreme Court decision with two critical holdings that now define the BPCIA landscape:

- The Patent Dance is Optional: The Court held that a biosimilar applicant cannot be forced to participate in the patent dance through a federal injunction.17 It reasoned that Congress had already provided a specific remedy for an applicant’s failure to make the initial disclosure: 42 U.S.C. § 262(l)(9)(C), which allows the RPS to immediately file a declaratory judgment action for patent infringement. The Court concluded that this statutory remedy was the

exclusive federal remedy, precluding courts from inventing others, like an injunction to compel participation.27 - The 180-Day Notice Can Be Given Pre-Approval: The Court overturned the Federal Circuit’s prior interpretation, ruling that a biosimilar applicant can provide its 180-day notice of commercial marketing before receiving final FDA approval for its product.17 The Federal Circuit had previously held that the notice was only effective post-licensure, a decision that critics argued amounted to a de facto six-month extension of the originator’s market exclusivity.22

The Strategic Fallout: A Fundamental Shift in Power Dynamics

The impact of the Sandoz decision cannot be overstated. It caused a seismic shift in the power dynamics of the BPCIA framework, transforming the patent dance from a procedural requirement into a strategic chessboard and handing the crucial opening move entirely to the biosimilar applicant.

Before this ruling, the dance was perceived as a linear, compulsory process. Both parties were locked into a predictable, if lengthy, timeline of exchanges. The Sandoz decision blew this structure apart. By making the dance optional, the Supreme Court created a fundamental fork in the road at the very outset of the process. The biosimilar applicant now holds all the cards in the initial engagement. It can choose to dance fully, adhering to every step. It can dance partially, engaging in some steps but not others. Or, like Sandoz, it can refuse to step onto the dance floor at all.18

This forces the RPS into an entirely reactive posture. Instead of following a predictable script, the RPS must now prepare for multiple strategic contingencies, its actions dictated entirely by the applicant’s initial choice. The applicant, not the statute, now controls the tempo and the nature of the initial conflict.

Furthermore, by allowing the 180-day notice to be given at any point (even during FDA review), the Court provided applicants with a powerful tool to compress the timeline to market launch. An applicant can now time its notice so that the 180-day clock expires concurrently with its anticipated FDA approval date, enabling a launch immediately upon licensure. This effectively nullified the extra six months of market protection that RPSs had enjoyed under the previous interpretation, a significant commercial blow.

The cumulative effect of these two rulings was a massive transfer of strategic initiative from the reference product sponsor to the biosimilar applicant. The applicant now dictates the “when” and “how” of the initial patent dispute, a formidable advantage in any high-stakes negotiation or litigation. The question for every biosimilar developer is no longer how to dance, but if they should dance at all.

The Applicant’s Gambit: To Dance or Not to Dance?

The Sandoz decision presents every biosimilar applicant with a critical strategic choice at the very beginning of their journey. The decision of whether to engage in the patent dance is not a simple one; it involves a complex trade-off between control, transparency, and risk. The optimal path depends entirely on the specific facts of the case, particularly the nature of the reference product’s patent estate.

The Case for Engaging in the Dance

Choosing to participate in the formal patent dance process offers a significant, albeit counterintuitive, advantage: control. This is the “controlled conflict” approach.

By engaging in the dance, the applicant can exert substantial influence over the timing and scope of the initial litigation.18 The structured timeline, while lengthy, provides a predictable pathway, which is invaluable for internal planning, budgeting, and setting investor expectations. More importantly, if the parties fail to agree on a list of patents to litigate, the BPCIA framework grants the applicant the power to define the size of the lawsuit. The applicant declares the number of patents it is willing to litigate, and each side then selects patents up to that number.18 This prevents the RPS from overwhelming the applicant with a lawsuit covering dozens or even hundreds of patents in the first wave. It allows the applicant to focus its resources on challenging the most threatening patents first, litigating from a position of relative strength.32

Participating in the dance also preserves the applicant’s right to file its own declaratory judgment action to challenge patents at a later stage, a right that is forfeited if the dance is skipped.17 For an applicant facing a complex patent landscape, maintaining this procedural flexibility can be a crucial long-term advantage.

The Case for Sidestepping the Dance

The alternative strategy is to refuse the invitation to dance. This is the “black box” approach, and its primary, overriding benefit is secrecy.

The price of admission to the dance is the disclosure of the applicant’s full aBLA and, most critically, its proprietary manufacturing process information.25 This information is the lifeblood of a biosimilar program, often containing invaluable trade secrets developed over years of painstaking work. Handing this detailed roadmap over to a direct competitor, even under confidentiality agreements, is a significant risk. It gives the RPS a perfect blueprint from which to craft infringement theories, potentially identifying vulnerabilities the applicant hadn’t even considered.

By refusing to dance, the applicant keeps its “black box” sealed. It forces the RPS to build an infringement case based on public information, assumptions, and whatever it can glean through reverse engineering—a far more difficult and less certain undertaking. This strategy is particularly potent when an applicant is confident that it has successfully “designed around” the RPS’s key process patents. In such a scenario, disclosing the novel, non-infringing process would not only reveal a key legal defense prematurely but also give away a valuable competitive advantage and trade secrets.

The Consequences of the Choice

Neither path is without its perils. The decision to opt out of the dance carries immediate and significant consequences. The strategic initiative for litigation shifts decisively to the RPS.

As established in Sandoz, the sole remedy for an applicant’s refusal to dance is that the RPS gains the right to immediately file a declaratory judgment action for infringement, validity, or enforceability of any patent that claims the biological product or its use.17 The RPS is no longer constrained to a negotiated list; it can assert its entire relevant patent portfolio at once, forcing the applicant into a sprawling, multi-front legal battle from day one. The applicant loses all control over the initial scope and timing of the litigation.

Furthermore, the financial stakes may be higher. By eschewing the dance, an applicant may forfeit the BPCIA’s damages limitation provision. Under 35 U.S.C. § 271(e)(6), if an RPS fails to bring suit within 30 days of the completion of the dance, its potential damages may be limited to a “reasonable royalty.” An applicant who refuses to dance may not be able to benefit from this safe harbor, potentially exposing it to the full measure of damages, including the RPS’s lost profits, which can be exponentially higher.17

Ultimately, the decision to dance or not is not a one-size-fits-all corporate policy but a highly nuanced, product-specific calculation. The evidence shows that companies make this choice on a case-by-case basis. Sandoz, for instance, famously skipped the dance for its filgrastim biosimilar but chose to engage in the process for its pegfilgrastim and etanercept biosimilars.20

This variability points to a clear underlying logic: the optimal strategy is a direct function of the specific patent landscape surrounding the target biologic. A thorough freedom-to-operate (FTO) analysis is the essential prerequisite for making this critical strategic choice. If the RPS’s patent estate is dominated by patents on the core molecule—which the biosimilar, by definition, must be highly similar to—there is little to be gained by hiding the aBLA. In this case, the benefits of controlling the litigation scope by participating in the dance are paramount. Conversely, if the RPS has built a formidable patent thicket around its manufacturing processes, and the applicant has invested heavily in developing a novel, non-infringing process, the “black box” strategy of not dancing becomes far more attractive. Protecting that key non-infringement argument and the associated trade secrets outweighs the benefits of a structured litigation. In this complex environment, leveraging comprehensive patent intelligence platforms like DrugPatentWatch to meticulously map the patent terrain is not just advisable; it is a critical necessity for informed, strategic decision-making.16

The Sponsor’s Counter-Play: Defending the Fortress

While the biosimilar applicant may control the opening moves, the reference product sponsor is far from a passive participant. The RPS’s strategic objective is clear: to maximize the commercial life of its blockbuster biologic by defending its market exclusivity for as long as possible. This defense is built on a foundation of proactive IP management and reactive legal strategy.

Preparing the Patent Thicket: A Proactive Defense

The most effective defense begins years before a biosimilar application is ever filed. The cornerstone of modern RPS strategy is the construction of a dense, multi-layered, and intentionally complex “patent thicket”.10 This goes far beyond patenting the core molecule. It involves systematically filing for patent protection on every conceivable aspect of the product and its lifecycle, including:

- Manufacturing Methods: As “the process is the product,” patents on specific cell lines, culture media, purification steps, and analytical methods are paramount.9

- Formulations: Patents can cover specific excipients, concentrations, and buffer systems that improve stability or reduce patient injection-site pain.38

- Dosing Regimens and Methods of Use: Patents on new indications or more convenient dosing schedules can extend exclusivity.38

- Delivery Devices: Patents on proprietary auto-injectors or pens can create another barrier to entry.

The infamous case of AbbVie’s Humira is the textbook example of this strategy in action. AbbVie amassed a portfolio of over 130 patents protecting Humira, many of them filed well after the drug’s initial approval and focused on incremental formulation or manufacturing changes. A deep analysis of this portfolio revealed that roughly 80% of the patents were “non-patentably distinct,” meaning they covered very similar subject matter.37 The goal of such a thicket is not necessarily for every patent to be a bastion of legal invincibility. Rather, the objective is to make a comprehensive patent challenge prohibitively complex, time-consuming, and expensive for any potential challenger.37 It shifts the battle from a legal debate on the merits of a few key patents to a war of economic attrition, a battle that heavily favors the well-capitalized incumbent.

Responding to the Applicant’s Dance Decision

Once an aBLA is filed, the RPS must shift to a reactive posture, its strategy dictated by the applicant’s choice regarding the dance.

- If the Applicant Dances: The 60-day window for the RPS to produce its initial patent list is incredibly tight. This requires extensive preparation long before the aBLA is even filed. The RPS must have a thoroughly vetted, prioritized list of patents ready to deploy. This list is a strategic document. It must be comprehensive enough to be a credible deterrent but not so over-inclusive that it exposes weak patents to challenge unnecessarily. The RPS must also make a strategic decision on which patents, if any, to offer for license, a move that could potentially resolve disputes over secondary patents early and allow both parties to focus on the core issues.

- If the Applicant Refuses to Dance: The applicant’s refusal to dance hands the RPS a powerful weapon: the immediate right to file a declaratory judgment action on its entire relevant patent portfolio.17 This allows the RPS to seize control of the litigation, define the initial battlefield on its own terms, and force the applicant onto the defensive across a broad front. However, this strategy is not without its challenges. The RPS must be prepared to assert its patents “blind,” without the benefit of having seen the applicant’s confidential aBLA and manufacturing processes. This requires a high degree of confidence in the breadth and strength of its patent estate.

Leveraging the New Transparency Rules

A recent legislative change has added a new layer of complexity to the RPS’s strategy. The Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2021 included a provision requiring that any patent list an RPS provides to an applicant during the patent dance must be submitted to the FDA for public listing in the “Purple Book” within 30 days of the exchange.41

This seemingly simple transparency measure creates a significant strategic dilemma for the RPS. Previously, the patent lists exchanged during the dance were confidential between the two parties.7 Now, the RPS’s opening salvo of patents becomes a public record. This forces a difficult calculation. On one hand, the RPS wants to present a formidable list to deter the current applicant. On the other hand, every patent on that public list becomes a potential target for an

Inter Partes Review (IPR) at the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB), not just by the current applicant but by any other potential competitor or interested third party.

An RPS might therefore become more conservative with its initial list, hesitant to publicly assert weaker patents that could be easily invalidated. This could, in turn, embolden the applicant, who faces a less intimidating initial list. This new transparency requirement subtly weakens the RPS’s ability to use an overwhelmingly large, unvetted list as a pure scare tactic in the dance’s opening phase, forcing a more carefully curated and defensible initial assertion.

The Anatomy of BPCIA Litigation: Beyond the Initial Dance Steps

The patent dance, whether completed or sidestepped, is merely the prelude. The ultimate resolution of the patent dispute unfolds in the courtroom and, increasingly, in parallel administrative proceedings. The BPCIA framework shapes this litigation in unique ways, creating a multi-phased conflict where the economic realities often loom larger than the legal arguments.

The Two Waves of Litigation

The BPCIA statute was designed to create two distinct phases, or “waves,” of patent litigation.2

- Phase 1 (The “First Wave”): This is the immediate lawsuit filed after the completion of the patent dance (or the applicant’s refusal to dance). It is intended to address the patents that the parties have identified as the most critical barriers to the biosimilar’s launch.

- Phase 2 (The “Second Wave”): This phase is triggered by the applicant’s 180-day Notice of Commercial Marketing. It provides the RPS with an opportunity to seek a preliminary injunction to block the biosimilar’s launch based on any patents that were included on its initial patent list but were not litigated in the first wave.7

In theory, this structure allows for an orderly resolution of patent disputes, tackling the biggest issues first while preserving rights on secondary patents. In practice, however, the Supreme Court’s Sandoz decision has dramatically altered this dynamic. By allowing the 180-day notice to be given before FDA approval, the ruling enables applicants to collapse the timeline between the two phases. An applicant can now receive FDA approval with the 180-day clock already expired, forcing all remaining patent disputes to be resolved in a single, high-pressure battle over a preliminary injunction on the eve of launch.20 This effectively merges the two waves into one, concentrating the legal and financial pressure into a single, critical moment.

The PTAB as a Parallel Battlefield

The district court is not the only venue where these battles are fought. Shrewd biosimilar applicants have increasingly turned to the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office’s Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) as a parallel front in their war against the RPS’s patent estate.2

By filing petitions for Inter Partes Review (IPR), an applicant can challenge the validity of an RPS’s patents in a forum that is often faster, less expensive, and statistically more favorable to the challenger than federal district court. This creates a powerful “pincer movement” strategy. The applicant can engage the RPS in the complex and resource-intensive patent dance and district court litigation, while simultaneously launching targeted IPRs against the most threatening patents. A victory at the PTAB can invalidate a patent entirely, removing it from the chessboard before it can even be fully litigated in court. This dual-track approach has become a standard and highly effective component of modern biosimilar litigation strategy.

The Ubiquity of Settlements

Despite the elaborate statutory framework designed to facilitate litigation, the vast majority of BPCIA disputes do not end with a final court judgment on the merits. Instead, they end in a negotiated settlement. Data suggests that as many as two-thirds of all terminated BPCIA litigations have ended in settlement or voluntary dismissal.32

The reasons for this are rooted in the immense economic risks faced by both sides. For a biosimilar applicant that has already invested upwards of $100 million in development, launching “at risk” before all patent disputes are resolved is a terrifying gamble. A subsequent finding of infringement could result in crippling damages, including the RPS’s lost profits, which could easily run into the billions and bankrupt the company.33

For the RPS, the risk is equally profound. While its revenue stream is secure during the litigation, an adverse court ruling that invalidates a key patent could open the floodgates to competition years earlier than anticipated, wiping out billions in future sales.

With the stakes so high and the outcome of complex patent litigation inherently uncertain, the most rational economic decision for both parties is often to seek certainty through a settlement. The patent dance, in this context, often functions less as a mechanism for streamlining litigation and more as a formal, high-cost discovery and information-gathering exercise. It allows each side to probe the other’s strengths and weaknesses, assess the true level of risk, and establish leverage for the inevitable business negotiation. The dance, therefore, frequently becomes a prelude to a deal that provides the applicant with a guaranteed, albeit delayed, market entry date, and grants the RPS a longer period of unchallenged exclusivity than it might have secured if it had risked and lost in court. The Humira saga, which saw AbbVie strike deals with numerous biosimilar manufacturers for staggered launch dates beginning in 2023, is the quintessential example of this dynamic in action.39

Case Studies from the Dance Floor: Strategy in Action

The strategic principles and legal nuances of the BPCIA framework are best understood through the lens of real-world conflicts. The litigation surrounding some of the world’s most successful biologics has shaped the interpretation of the law and provides invaluable lessons in strategy and execution.

Sandoz v. Amgen (Zarxio/Neupogen) – The Dance Refused

The dispute over Sandoz’s Zarxio, a biosimilar to Amgen’s Neupogen, is the origin story of modern BPCIA strategy. In a move that was at the time considered audacious, Sandoz chose to completely opt out of the patent dance, refusing to provide Amgen with its aBLA and manufacturing data.24 Sandoz’s rationale was to protect its proprietary manufacturing processes and to challenge the prevailing interpretation that the dance was mandatory. This bold gambit triggered the lawsuit that traveled all the way to the Supreme Court, resulting in the landmark 2017 decision that confirmed the dance’s optionality and reshaped the entire strategic landscape.23 Sandoz’s strategy, while risky, ultimately paid off, not only by protecting its confidential information but by creating the very legal precedent that now empowers all subsequent biosimilar applicants. The case serves as a powerful illustration of how a calculated legal challenge can redefine the rules of engagement for an entire industry.

The Humira Saga – The Patent Thicket Triumphant

No case better illustrates the power of the patent thicket strategy than the battle over AbbVie’s Humira (adalimumab), the best-selling drug in history. AbbVie constructed a virtually impenetrable fortress of over 130 patents, many of which were filed late in the drug’s lifecycle and covered incremental changes.37 As multiple biosimilar developers, including Amgen, Sandoz, and Boehringer Ingelheim, received FDA approval for their versions—some as early as 2016—they were met with a barrage of patent infringement lawsuits from AbbVie.45

The sheer volume of patents made a full legal challenge a daunting and ruinously expensive prospect for any single challenger. The patent dance, in this context, did little to streamline the disputes. Instead, it became the opening phase of a war of attrition. Ultimately, every major biosimilar challenger capitulated, entering into settlement agreements with AbbVie. These deals created an orchestrated and staggered series of market entry dates, all beginning in 2023, years after the primary patent on Humira had expired and years after the biosimilars were deemed safe and effective by the FDA.43 The Humira saga stands as a stark testament to how a sufficiently dense patent thicket can overwhelm the BPCIA’s intended mechanisms and effectively delay competition through overwhelming legal and economic pressure.

The Remicade (Infliximab) Litigations – Early Lessons in Procedure and Damages

The early litigations between Janssen, the sponsor of Remicade (infliximab), and biosimilar developer Celltrion provided some of the first crucial judicial interpretations of the BPCIA’s procedural intricacies. In one key instance, Celltrion attempted to file a declaratory judgment action to invalidate Remicade patents before it had even submitted its aBLA to the FDA. The court dismissed the case, establishing the important precedent that the BPCIA’s litigation framework cannot be preempted and that a concrete dispute, anchored by an accepted aBLA, is required.28

Even more significantly, the Remicade case provided a critical ruling on the consequences of failing to fully participate in the dance. Celltrion engaged in the initial steps but then, according to Janssen, refused to participate in the good faith negotiation phase. In a pivotal decision, the court ruled that this failure to complete the dance meant that Celltrion could not benefit from the BPCIA’s damages limitation provision. This exposed Celltrion to the risk of paying Janssen’s full lost profits, rather than just a reasonable royalty, if it were ultimately found to infringe.33 This case sent a clear message to the industry: while the dance as a whole is optional, once you choose to participate, you cannot selectively skip the required steps without facing potentially severe financial consequences.

The Rituxan (Rituximab) Disputes – Navigating International and Procedural Hurdles

The legal battles over biosimilars to Genentech’s Rituxan (rituximab) further clarified the procedural obligations of the dance. In a case involving Celltrion, the biosimilar applicant engaged in the initial information exchanges but then failed to participate in the crucial negotiation and list-exchange steps that determine the scope of the first-wave litigation. Celltrion argued that its notice of commercial marketing should trigger a new phase allowing it to file a declaratory judgment action. The court disagreed, dismissing Celltrion’s lawsuit.48

The court’s reasoning was clear: the BPCIA sets out a specific sequence of steps, and an applicant’s failure to comply with those steps bars it from bringing its own declaratory judgment action. The ruling reinforced the idea that while the decision to enter the dance is voluntary, the steps within the dance are not. A party cannot unilaterally terminate the process midway through to gain a procedural advantage. This case highlights the critical importance of meticulous adherence to the statutory framework once the decision to dance has been made, as procedural foot-faults can lead to a complete forfeiture of important legal rights.

The Final Score: The Future of the Dance and Biosimilar Competition

More than a decade after its enactment, the BPCIA and its patent dance remain a focal point of intense debate and strategic maneuvering. The framework has undeniably reshaped the landscape for biologic medicines, but its success in achieving its dual goals of fostering innovation and promoting affordable access is a matter of ongoing assessment.

Is the Dance Fulfilling Its Purpose?

The patent dance was intended to create an orderly, predictable, and streamlined process for resolving patent disputes before a biosimilar launch. The reality has been far more complex. Evidence suggests that the process often fails to achieve one of its primary goals: narrowing the number of patents asserted in litigation. One analysis of BPCIA cases found almost no difference in the average number of patents at issue between cases where the parties completed the dance and cases where they did not.49

Instead of providing clarity and certainty, the dance can become just another layer of costly and time-consuming legal strategy.14 While it has proven effective at forcing parties to the negotiating table and promoting settlements 32, the outcomes of those settlements—often involving significant delays in market entry—raise questions about whether the BPCIA is truly delivering on its promise of timely access to lower-cost medicines. The delays can be substantial, with one study suggesting that the current litigation framework delays biosimilar market entry by an average of 1.8 years after the primary patent on the reference biologic expires.51

The Evolving Toolkit: Integrating Data for Competitive Advantage

In this high-stakes, high-complexity environment, success is increasingly dependent on access to comprehensive, real-time intelligence. The days of making strategic decisions based on static information are over. Both biosimilar applicants and reference product sponsors must continuously monitor the dynamic patent and regulatory landscape to inform their strategies.

For an applicant, this means conducting exhaustive freedom-to-operate analyses and patent landscape mapping long before committing hundreds of millions of dollars to a development program. For a sponsor, it means vigilantly tracking competitor pipelines, monitoring PTAB challenges against its portfolio, and dynamically adjusting its life-cycle management and patenting strategies.

This is where sophisticated patent intelligence platforms become indispensable. Services like DrugPatentWatch provide the critical tools needed to navigate this terrain effectively. By offering real-time patent monitoring, detailed landscape analysis, and deep competitive intelligence, such platforms empower legal and business teams to make proactive, data-driven decisions at every stage of the BPCIA process—from the initial product selection and the crucial “to dance or not to dance” decision, all the way through litigation and the final settlement negotiation.16 In the modern biosimilar battle, superior information is superior firepower.

The Road Ahead: Potential Reforms and Market Evolution

The biosimilar patent dance is not a static entity. It is constantly evolving under the influence of new court decisions, regulatory guidance, and potential legislative reforms. Several proposals are currently being debated that could further alter the strategic landscape, such as legislative caps on the number of patents an RPS can assert in BPCIA litigation, a direct response to the “patent thicket” strategy.40

Simultaneously, the FDA continues to refine its regulatory approach. Moves to streamline the requirements for an “interchangeability” designation or to waive the need for certain clinical efficacy studies could significantly lower the cost and time of biosimilar development.52 Such changes would lower the barriers to entry, potentially encouraging more companies to enter the market and increasing competitive pressure.

The future of the dance will be shaped by this dynamic interplay of legal, regulatory, and market forces. The ultimate question remains whether these evolutions will finally tilt the balance, allowing the BPCIA to fully deliver on its foundational promise: a robust, competitive biosimilar market that provides significant healthcare savings—projected to be over $180 billion in the next five years—while continuing to reward the profound innovation that brings life-saving biologic medicines to patients.2 The dance will go on, and for those who know the steps, the rewards will be immense.

Key Takeaways

- The Patent Dance is a Strategic Choice, Not a Mandate: Following the Supreme Court’s decision in Sandoz v. Amgen, the decision to engage in the BPCIA patent dance rests entirely with the biosimilar applicant. This transforms the process from a rigid procedure into a critical strategic decision based on the specific patent landscape of the target biologic.

- Control vs. Secrecy is the Core Applicant Dilemma: Dancing offers the applicant significant control over the scope and timing of the initial litigation. Refusing to dance protects highly sensitive manufacturing process information but cedes control of the litigation to the reference product sponsor and carries potentially higher financial risks.

- Patent Thickets are the RPS’s Primary Defense: The most effective strategy for reference product sponsors is the proactive creation of a dense, multi-layered patent portfolio covering not just the molecule but also manufacturing processes, formulations, and methods of use. This strategy aims to make litigation prohibitively complex and expensive for challengers.

- The 180-Day Notice is a Key Timing Weapon: The ability to provide the 180-day notice of commercial marketing before FDA approval allows biosimilar applicants to compress the launch timeline and eliminate what was once a de facto six-month extension of market exclusivity for the originator.

- Litigation Often Leads to Settlement: Due to the immense financial risks for both sides—crippling damages for the applicant, premature loss of exclusivity for the sponsor—the majority of BPCIA disputes are resolved through negotiated settlements that provide market entry certainty, rather than through a final court decision.

- Data-Driven Strategy is Non-Negotiable: Success in the BPCIA framework requires continuous, in-depth analysis of the patent landscape. Leveraging comprehensive patent intelligence tools like DrugPatentWatch is essential for making informed decisions at every stage of the process, from initial FTO analysis to litigation and settlement strategy.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. Can a biosimilar applicant start the patent dance, and then decide to stop partway through? What are the consequences?

While the Supreme Court made the initial decision to dance optional, the steps within the dance are generally considered mandatory once initiated. Case law, particularly from the Rituxan and Remicade litigations, has shown that courts take a dim view of applicants attempting to unilaterally abandon the process midway through. For example, failing to participate in the good faith negotiation and list-exchange steps after the initial disclosures can result in the court dismissing the applicant’s own declaratory judgment actions and potentially forfeiting the right to limit damages to a reasonable royalty. The prevailing view is that once you step onto the dance floor, you are expected to complete the choreography; selectively skipping steps can lead to severe procedural and financial penalties.

2. How has the new requirement to publish patent dance lists in the FDA’s Purple Book changed the strategy for Reference Product Sponsors (RPS)?

This transparency requirement has introduced a new layer of strategic complexity for the RPS. Previously, the initial list of asserted patents was a confidential exchange, allowing the RPS to present a broad, intimidating list as a negotiation tactic. Now, that list becomes public record. This creates a dilemma: asserting a very large list publicly exposes weaker patents to challenge via IPRs from any third party, not just the current applicant. However, asserting too narrow a list might fail to deter the applicant and could be seen as a sign of weakness. It forces the RPS to be more judicious and strategic with its initial assertions, likely focusing on a more curated list of its strongest patents rather than relying on sheer volume.

3. If most BPCIA cases settle, what is the real value of engaging in the costly and complex patent dance?

The value of the patent dance in a settlement-driven environment lies in its function as a formal mechanism for discovery and leverage-building. It forces a structured exchange of highly detailed information and legal arguments that would otherwise only be available through protracted court-ordered discovery. This process allows both sides to gain a much clearer understanding of the strengths and weaknesses of their respective positions much earlier in the dispute. For the applicant, it reveals the patents the RPS truly values. For the RPS, it reveals the applicant’s non-infringement and invalidity defenses. This mutual clarification of risk is what enables productive settlement negotiations. The dance, therefore, isn’t just a prelude to litigation; it’s the essential prelude to a rational business negotiation.

4. Can a biosimilar applicant use the “safe harbor” provision (35 U.S.C. § 271(e)(1)) to protect pre-launch manufacturing and stockpiling of their product?

This is a contentious and high-risk area. The safe harbor protects activities “solely for uses reasonably related to the development and submission of information under a Federal law which regulates the…use of drugs.” This clearly covers R&D activities and manufacturing batches for the purpose of submitting the aBLA. However, courts have interpreted this narrowly. Manufacturing large quantities of a biosimilar for the purpose of building up commercial inventory to launch immediately upon approval (i.e., “stockpiling”) has been found to fall outside the scope of the safe harbor. Such activities could be considered an act of commercial infringement, potentially exposing the applicant to significant damages even before the product is sold. Applicants must be extremely cautious in managing their pre-launch manufacturing activities to avoid crossing this line.

5. How does the concept of “interchangeability” affect the patent dance and litigation strategy?

Interchangeability is a separate, higher regulatory standard beyond biosimilarity, allowing a pharmacist to substitute the interchangeable product for the reference biologic without consulting the prescriber. While the patent dance itself does not change based on whether an applicant seeks an interchangeability designation, the commercial stakes are higher. An interchangeable biosimilar is expected to capture market share more rapidly, making the potential “at-risk” launch damages for the applicant even greater. For the RPS, the threat is more acute, making them more likely to litigate aggressively to prevent the launch of an interchangeable competitor. Furthermore, the BPCIA grants a period of exclusivity to the first biosimilar to achieve an interchangeable designation, creating a race among applicants that can influence their willingness to take risks in litigation or accept settlement terms to be first to market with that coveted status.

Works cited

- The Paradox of Progress: Does Biosimilar Competition Truly Reduce Patient Out-of-Pocket Costs for Biologic Drugs? – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/biosimilar-competition-does-not-reduce-patient-out-of-pocket-costs-for-biologic-drugs/

- Predicting Patent Litigation Outcomes for Biosimilars: Navigating the Complex Landscape of Pharmaceutical Innovation for Biosimilars – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/predicting-patent-litigation-outcomes-for-biosimilars/

- “SHALL”WE DANCE?INTERPRETING THE BPCIA’S PATENT PROVISIONS – Berkeley Technology Law Journal, accessed August 18, 2025, https://btlj.org/data/articles2016/vol31/31_ar/0659_0686_Tanaka_WEB.pdf

- Evaluating Biosimilar Development Projects: An Analytical Framework Utilizing Net Present Value – PMC, accessed August 18, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11955401/

- The Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act: Is a Generic Market for Biologics Attainable? – Scholarship Repository, accessed August 18, 2025, https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1150&context=wmblr

- Pharmaceutical Patent Disputes: Biosimilar Entry Under the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA) | Congress.gov, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/IF13029

- The Biosimilar Regulatory Pathway and the Patent Dance(1), accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.jenner.com/a/web/pjTABXAWvtwg9iwnp1c2QN/4HRMZQ/The_Biosimilar_Regulatory_Pathway_and_the_Patent_Dance.pdf

- Manufacturers Of Biosimilar Drugs Sit Out The ‘Patent Dance’ | Health Affairs Forefront, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/forefront.20170310.059143/

- Cracking the Biosimilar Code: A Deep Dive into Effective IP Strategies – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/cracking-the-biosimilar-code-a-deep-dive-into-effective-ip-strategies/

- Biologics, Biosimilars and Patents: – I-MAK, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.i-mak.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Biologics-Biosimilars-Guide_IMAK.pdf

- What Is the Impact of the BPCIA Patent Dance on Market Entry? – Patsnap Synapse, accessed August 18, 2025, https://synapse.patsnap.com/article/what-is-the-impact-of-the-bpcia-patent-dance-on-market-entry

- Commemorating the 15th Anniversary of the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/cder-conversations/commemorating-15th-anniversary-biologics-price-competition-and-innovation-act

- Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act of 2009 – Wikipedia, accessed August 18, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Biologics_Price_Competition_and_Innovation_Act_of_2009

- Market Access 2024 | The biosimilars dance: how drugmakers game the US patent system, accessed August 18, 2025, https://deep-dive.pharmaphorum.com/magazine/market-access-2024/biosimilars-dance-drugmakers-us-patent-system/

- How Biosimilars Are Approved and Litigated: Patent Dance Timeline – Fish & Richardson, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.fr.com/insights/ip-law-essentials/how-biosimilars-approved-litigated-patent-dance-timeline/

- Biosimilar Patent Dance: Leveraging PTAB Challenges for Strategic …, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/biosimilar-patent-dance-leveraging-ptab-challenges-for-strategic-advantage/

- What Is the Patent Dance? | Winston & Strawn Law Glossary, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.winston.com/en/legal-glossary/patent-dance

- Shall We (Patent) Dance — Key Considerations For Biosimilar Applicants, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.biosimilardevelopment.com/doc/shall-we-patent-dance-key-considerations-for-biosimilar-applicants-0001

- The Inner Workings of the BPCIA Patent Dance – Center for Biosimilars, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.centerforbiosimilars.com/view/the-inner-workings-of-the-bpcia-patent-dance

- The Patent Dance | Articles | Finnegan | Leading IP+ Law Firm, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.finnegan.com/en/insights/articles/the-patent-dance-article.html

- Guide to the BPCIA’s Biosimilars Patent Dance – Big Molecule Watch, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.bigmoleculewatch.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2022/12/Patent-Dance-Guide-December-2022.pdf

- Dance or Not, Biosimilar Applicants Must Provide 180-Day Notice of Commercial Marketing Under the BPCIA – Akin Gump, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.akingump.com/en/insights/blogs/ip-newsflash/dance-or-not-biosimilar-applicants-must-provide-180-day-notice

- Amgen v. Sandoz: The Supreme Court’s First Biosimilars Ruling | Mintz, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.mintz.com/insights-center/viewpoints/2017-06-14-amgen-v-sandoz-supreme-courts-first-biosimilars-ruling

- Supreme Court’s ‘Sandoz v. Amgen’ Decision Favors Biosimilars – Fox Rothschild LLP, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.foxrothschild.com/publications/supreme-courts-sandoz-v-amgen-decision-favors-biosimilars

- Case Note: Sandoz v. Amgen – Food and Drug Law Institute (FDLI), accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.fdli.org/2017/08/case-note-sandoz-v-amgen/

- 15-1039 Sandoz Inc. v. Amgen Inc. (06/12/2017) – Supreme Court, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/16pdf/15-1039_1b8e.pdf

- 5 Key Questions for Biosimilar Applicant’s to Consider – Fish …, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.fr.com/insights/thought-leadership/blogs/biosimilars-guide-bpcia-patent-dance-five-key-questions/

- Five key questions about the ‘patent dance’ answered – Generics and Biosimilars Initiative, accessed August 18, 2025, https://gabionline.net/policies-legislation/Five-key-questions-about-the-patent-dance-answered

- Sandoz v. Amgen: Biosimilar Act Disclosure Obligations Not Enforceable by Injunction— Anywhere – Food and Drug Law Institute (FDLI), accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.fdli.org/2018/07/sandoz-v-amgen-biosimilar-act-disclosure-obligations-not-enforceable-by-injunction-anywhere/

- 5 Questions To Ask About Biosimilars In 2016, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.biosimilardevelopment.com/doc/questions-to-ask-about-biosimilars-in-0001

- Biosimilar Patent Dance: BPCIA Framework & Litigation Guide – Effectual Services, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.effectualservices.com/article/biosimilar-patent-dance

- Patent Dance Insights: A Q&A on Reducing Legal Battles in the Biosimilar Landscape, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.centerforbiosimilars.com/view/patent-dance-insights-a-q-a-on-reducing-legal-battles-in-the-biosimilar-landscape

- Janssen v. Celltrion, Damages: “Patent Dance” May Determine Availability of Lost Profits, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.mintz.com/insights-center/viewpoints/2017-03-29-janssen-v-celltrion-damages-patent-dance-may-determine

- The Biosimilar Patent Dance What Can We Learn From Recent BPCIA Litigation, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.biosimilardevelopment.com/doc/the-biosimilar-patent-dance-what-can-we-learn-from-recent-bpcia-litigation-0001

- Exploring Biosimilars as a Drug Patent Strategy: Navigating the Complexities of Biologic Innovation and Market Access – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/exploring-biosimilars-as-a-drug-patent-strategy-navigating-the-complexities-of-biologic-innovation-and-market-access/

- Drug Patent Watch Launches Service Offering Real-Time Patent Monitoring for Pharmaceutical Companies. – GeneOnline News, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.geneonline.com/drug-patent-watch-launches-service-offering-real-time-patent-monitoring-for-pharmaceutical-companies/

- Biological patent thickets and delayed access to biosimilars, an American problem – PMC, accessed August 18, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9439849/

- Implications of the BPCIA on the IP Strategies of Brand Companies and Biosimilar Developers | Sterne Kessler, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.sternekessler.com/news-insights/insights/implications-bpcia-ip-strategies-brand-companies-and-biosimilar/

- A Case Study of Humira’s Patent Extension … – DASH (Harvard), accessed August 18, 2025, https://dash.harvard.edu/bitstreams/0b2cd634-f60c-422f-8861-74725c0c940b/download

- Infographic: Number of FDA Drug Approvals By Year – Center for Biosimilars, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.centerforbiosimilars.com/view/infographic-number-of-fda-drug-approvals-by-year

- Taking Advantage of the New Purple Book Patent Requirements for Biologics, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.morganlewis.com/pubs/2021/04/taking-advantage-of-the-new-purple-book-patent-requirements-for-biologics

- #Biosimilar Patent Dance: Leveraging #PTAB Challenges for Strategic Advantage #patentdance – YouTube, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qclyejztmkg

- Breaking Down Biosimilar Barriers: The Patent System, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.centerforbiosimilars.com/view/breaking-down-biosimilar-barriers-the-patent-system

- Economic Considerations Related to Biosimilar Market Entry – American Bar Association, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.americanbar.org/groups/antitrust_law/resources/newsletters/economic-considerations-biosimilar-market-entry/

- Biologics and Biosimilars Landscape 2023: IP, Policy, and Market Developments, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.fr.com/insights/thought-leadership/blogs/biologics-and-biosimilars-landscape-ip-policy-and-market-developments

- Biosimilars 2020 Year in Review – Fish & Richardson, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.fr.com/insights/thought-leadership/blogs/biosimilars-2020-year-in-review/

- Litigation Spotlight: The Infliximab (Remicade®) Litigation – Biosimilars Law Bulletin, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.biosimilarsip.com/2017/04/19/litigation-spotlight-infliximab-remicade-litigation/

- District Court Grants Genentech’s Motions to Dismiss Celltrion’s Declaratory Judgment Actions in Herceptin® and Rituxan®-Related Suits | Biosimilars Law Bulletin, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.biosimilarsip.com/2018/05/11/district-court-grants-genentechs-motions-to-dismiss-celltrions-declaratory-judgment-actions-in-herceptin-and-rituxan-related-suits/

- BPCIA Info Exchange Is Failing To Streamline Patent Litigation | Choate Hall & Stewart LLP, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.choate.com/insights/bpcia-info-exchange-is-failing-to-streamline-patent-litigation.html

- Dance of the Biologics – Berkeley Technology Law Journal, accessed August 18, 2025, https://btlj.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/0004_39-2_Feldman.pdf

- Accelerating biosimilar market access: the case for allowing earlier standing | Journal of Law and the Biosciences | Oxford Academic, accessed August 18, 2025, https://academic.oup.com/jlb/article/12/1/lsae030/7942247

- BioRationality—The Evolution of the BPCIA and the Bright Future of Biosimilars in the US, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.centerforbiosimilars.com/view/biorationality-the-evolution-of-the-bpcia-and-the-bright-future-of-biosimilars-in-the-us

- Biosimilar Litigation Considerations: Economic Factors in Intellectual Property and Antitrust Cases – Analysis Group, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.analysisgroup.com/Insights/ag-feature/biosimilar-litigation-considerations-economic-factors-in-intellectual-property-and-antitrust-cases/