In the high-stakes world of pharmaceuticals, the ability to predict the future isn’t just an advantage; it’s a fundamental requirement for survival and success. For both brand-name drug manufacturers bracing for the inevitable patent cliff and generic companies seeking the next blockbuster opportunity, the question is always the same: When will the competition arrive? For years, analysts have pieced together clues from patent filings, court dockets, and industry whispers. But what if there was a clearer, more definitive signal—a regulatory milestone that acts as a starting gun for the final, most intense phase of a drug’s lifecycle?

There is. It’s called a Tentative Approval.

You might be wondering, “If these approvals aren’t final, why should I care?”. Well, my friend, tentative approvals are the closest thing we have to a crystal ball in the pharmaceutical industry. Issued by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), these approvals are like golden tickets that generic drug manufacturers receive when their products have met all the necessary scientific and regulatory requirements for approval—with one crucial catch. They cannot yet be granted final approval for marketing because of existing patents or other market exclusivities protecting the brand-name drug.1

This single document transforms the forecasting landscape. It cuts through the fog of scientific and manufacturing uncertainty, confirming that a generic competitor is not just a theoretical threat but a tangible one, ready and waiting at the gates. The only remaining barrier is the intellectual property (IP) fortress built around the brand-name product. By understanding and strategically analyzing these approvals, you can move beyond reactive defense and into the realm of proactive, predictive strategy. You can begin to:

- Predict with far greater accuracy when generic versions of key brand-name drugs will hit the market.

- Identify the specific companies that will be your primary competitors in a given therapeutic category.

- Estimate the level and intensity of future competition, forecasting the speed of price erosion and market share loss.

- Make highly informed, data-driven decisions about your own product development, lifecycle management, and marketing strategies.

This report is your comprehensive guide to unlocking the predictive power of tentative approvals. We will dissect the intricate regulatory framework that governs this process, explore the high-stakes legal battles that define it, and provide a practical toolkit for turning this public data into a powerful competitive advantage. We’ll move from the foundational principles of the Hatch-Waxman Act to the granular details of litigation strategy, using real-world case studies to illustrate how these forces play out in the market. By the end, you won’t just understand what a tentative approval is; you’ll know how to wield it as a strategic weapon to anticipate, navigate, and ultimately master the dynamics of generic entry.

The Regulatory Bedrock: Understanding the Hatch-Waxman Act and the Generic Approval Pathway

To truly grasp the significance of a tentative approval, we must first travel back to 1984. Before this pivotal year, the generic drug industry as we know it today simply did not exist. The landscape was dominated by brand-name manufacturers, and the path to market for a generic equivalent was a Sisyphean task, deliberately designed to be almost insurmountable. This all changed with the passage of a landmark piece of legislation: the Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act, more famously known as the Hatch-Waxman Act.3

Named for its sponsors, Senator Orrin Hatch and Representative Henry Waxman, this Act was a masterclass in legislative compromise. It struck a delicate but revolutionary balance between two competing interests: the need to incentivize pharmaceutical innovation through strong patent protection for brand-name companies and the public health imperative to increase access to affordable medications through generic competition.3 The result was a “grand bargain” that fundamentally reshaped the pharmaceutical industry and laid the legal and economic foundation for the modern generic market.3

The Birth of the Modern Generic Industry

Before Hatch-Waxman, a company wishing to market a generic drug faced a daunting regulatory burden. It was required to submit a full New Drug Application (NDA), complete with its own expensive and time-consuming clinical trials to independently prove the drug’s safety and effectiveness. This was the case even if the brand-name version, containing the exact same active ingredient, had been on the market for years and its safety and efficacy were already well-established. This created a massive barrier to entry, making generic development economically unviable for all but the most determined players.

The result? In 1984, when the Act was passed, generic drugs accounted for a mere 19% of all prescriptions filled in the United States. The Hatch-Waxman Act shattered this paradigm. Today, thanks to the streamlined pathway it created, generics account for more than 90% of prescriptions filled, saving the U.S. healthcare system trillions of dollars and dramatically increasing patient access to life-saving medicines.3

A Grand Bargain: Key Provisions of the Act

The genius of the Hatch-Waxman Act lies in the balanced incentives it created for both sides of the pharmaceutical aisle. It was not a zero-sum game; it was a carefully constructed framework where both innovators and generic manufacturers received significant benefits.

For Generics: The Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) Pathway

The cornerstone of the Act’s pro-competitive measures was the creation of the Abbreviated New Drug Application, or ANDA, under section 505(j) of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic (FD&C) Act.3 This new pathway was revolutionary. Instead of conducting their own duplicative clinical trials, generic applicants could now rely on the FDA’s previous finding that the innovator’s product—the Reference Listed Drug (RLD)—was safe and effective.

The primary requirement for an ANDA applicant became demonstrating bioequivalence: proving that their generic drug delivered the same amount of active ingredient into a patient’s bloodstream over the same period of time as the brand-name drug.10 This dramatically lowered the cost and time required to bring a generic to market.

Furthermore, the Act created a crucial “safe harbor” provision. This allowed generic companies to conduct the development and testing work necessary for their ANDA submission—activities that would otherwise constitute patent infringement—without fear of being sued by the brand manufacturer during this preparatory phase.3 This provision was a direct response to a court case,

Roche Products, Inc. v. Bolar Pharmaceutical Co., which had effectively extended a brand’s monopoly by preventing generics from even starting their development work until after the patent expired.

For Brands: Patent Term Restoration & Market Exclusivity

To ensure that this new pro-generic framework didn’t stifle innovation, the Hatch-Waxman Act provided significant new protections for brand-name drug manufacturers. The most important of these were:

- Patent Term Restoration: The Act acknowledged that a significant portion of a patent’s 20-year term is often consumed by the lengthy clinical trial and FDA review process. To compensate for this, it allows brand companies to apply for an extension of their patent term for a portion of the time lost to regulatory review, ensuring a more meaningful period of market exclusivity post-approval.3

- Data Exclusivity: The Act also created new forms of FDA-administered market exclusivity that are entirely separate from patents. The most significant is the five-year New Chemical Entity (NCE) exclusivity. This provision prevents the FDA from even accepting an ANDA for a drug containing a new active ingredient for the first four years after the brand drug’s approval, and from approving it for five years.6 Other exclusivities, such as a three-year period for new clinical investigations supporting a new use of a previously approved drug, were also established.

This intricate system of checks and balances did more than just create a regulatory pathway; it established a predictable, timeline-driven system of conflict. The Act’s provisions—the ANDA filing as an “artificial act of infringement,” the 45-day window for the brand to sue, the automatic 30-month stay on FDA approval, and the coveted 180-day exclusivity prize for the first challenger—are not just administrative rules.15 They are the explicit mechanics of a high-stakes strategic game. This “gamification” of the patent challenge process is what makes generic entry forecasting possible. Because the steps are codified, sequential, and tied to specific deadlines, a savvy analyst can map these milestones from the moment a patent challenge is initiated, creating a structured and reliable framework for predicting potential launch windows.

The Anatomy of a Tentative Approval

Now that we’ve established the regulatory stage set by the Hatch-Waxman Act, let’s zoom in on our lead actor: the Tentative Approval (TA). A TA is a formal communication from the FDA that carries immense strategic weight. It is a definitive signal that a generic drug application has successfully cleared all scientific and manufacturing hurdles and is, in the eyes of the regulator, ready for prime time.2 The only thing holding it back from full, final approval is the lingering presence of the brand-name drug’s intellectual property rights.

According to the FDA’s Generic Drugs Program reports, tentative approvals are a routine and significant part of the regulatory workload. For example, in a representative fiscal year, the agency might issue 174 tentative approvals alongside 483 full approvals. This high frequency underscores their importance as a common and reliable indicator of the future competitive pipeline.

More Than a “Maybe”: What a TA Signifies

It is critical to understand that a tentative approval is not a preliminary, conditional, or uncertain finding. It is a final decision from the FDA’s scientific review teams. When a generic manufacturer receives a TA letter, it means their Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) has been thoroughly reviewed and found to meet the same rigorous standards for safety, efficacy, and quality as any other FDA-approved drug.2

This is a crucial distinction for anyone involved in forecasting. The issuance of a TA effectively removes two major variables from the generic launch equation:

- Scientific Uncertainty: The FDA has confirmed that the generic product is bioequivalent to the brand-name drug. There are no lingering questions about its formulation or performance.

- Manufacturing Uncertainty: The FDA has also reviewed and approved the applicant’s manufacturing processes, facilities, and quality control systems.

This external validation by the FDA confirms that the generic company is not just legally prepared to challenge a patent but is also operationally prepared to manufacture and launch its product at scale as soon as the legal barriers are removed. For a competitive intelligence analyst, this signal significantly de-risks the forecast, allowing you to shift focus almost entirely to the legal and IP timeline, which, as we’ve seen, is a structured and predictable process.

The Roadblocks: Patents and Exclusivities Explained

So, what are these barriers that turn a potential full approval into a tentative one? They fall into two main categories: patents and FDA-administered exclusivities. The TA letter itself will generally specify which of these are preventing final approval, providing a clear roadmap of the remaining hurdles.

- Patents: The most common roadblock is one or more unexpired patents listed in the FDA’s Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations, colloquially known as the Orange Book.2 These patents, granted by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (PTO), can cover the drug’s active ingredient, its formulation, a method of using it to treat a specific disease, or even a manufacturing process.14 A TA is issued when a generic is ready for market before these patents expire.

- Exclusivities: These are periods of marketing protection granted by the FDA upon a drug’s approval and are completely separate from patents. They are designed to encourage certain types of drug development. If a generic is ready before one of these exclusivity periods ends, it will receive a TA. Key exclusivities include:

- New Chemical Entity (NCE) Exclusivity: Five years of protection for drugs containing an active ingredient never before approved by the FDA.6

- New Clinical Investigation Exclusivity: Three years of protection for new uses or formulations of existing drugs that required new clinical trials.

- Orphan Drug Exclusivity (ODE): Seven years of protection for drugs developed to treat rare diseases (affecting fewer than 200,000 people in the U.S.).14

- Pediatric Exclusivity: An additional six months of protection added to existing patents and exclusivities as a reward for conducting pediatric studies.

By receiving a TA, a generic company secures its place in the approval queue. Once the last patent or exclusivity period expires or is resolved through litigation, the company can convert its TA into a final approval, often with a simple notification to the agency, and prepare for market launch.

The Challenger’s Opening Move: The Paragraph IV Certification

The journey from ANDA submission to tentative approval—and eventually to market—almost always begins with a single, audacious strategic move: the Paragraph IV certification. This is not a passive declaration; it is a direct challenge to the brand-name manufacturer’s intellectual property and the legal mechanism that triggers the entire Hatch-Waxman litigation process. In the competitive chess match of generic entry, the Paragraph IV filing is the opening gambit.

This strategy is remarkably common. The FDA has noted that approximately 40% of all ANDAs it receives contain a Paragraph IV patent challenge. For high-value blockbuster drugs, the rate is even higher, with one study finding that 93% of top-selling drugs faced at least one such challenge. This tells us that challenging patents is not the exception; it is the primary and preferred strategy for generic companies seeking to enter lucrative markets.

The Four Certifications: Choosing Your Path

When a generic company files an ANDA, it must address every patent listed in the Orange Book for the brand-name drug it seeks to copy. The Hatch-Waxman Act provides four ways to do this, known as patent certifications.1 The choice of certification defines the company’s entire market entry strategy.

| Certification | Meaning | Strategic Implication |

| Paragraph I | No patent information has been submitted to the FDA for the brand-name drug. | Uncontested entry is possible, but this is extremely rare for modern drugs. |

| Paragraph II | The patent listed in the Orange Book has already expired. | Uncontested entry is possible, as there is no IP barrier. |

| Paragraph III | The patent listed in the Orange Book is still in force, and the generic company will wait to market its product until the patent expires. | This is a non-confrontational, delayed-entry strategy. The generic will likely face competition from day one of its launch. |

| Paragraph IV | The patent listed in the Orange Book is invalid, unenforceable, or will not be infringed by the generic company’s product. | This is an aggressive, early-market entry strategy. It initiates patent litigation but also opens the door to the highly valuable 180-day exclusivity period. |

While Paragraphs I, II, and III represent straightforward, non-confrontational paths, the Paragraph IV certification is a declaration of war. It is a bold statement that the generic company believes the brand’s patent protection is either weak or irrelevant to their product and that they are prepared to prove it in court.

The High-Stakes Gambit: Why File a Paragraph IV?

Why would a generic company voluntarily invite a costly and complex patent lawsuit from a well-funded brand-name manufacturer? The answer lies in the grand prize established by the Hatch-Waxman Act: 180 days of marketing exclusivity.1

This provision is the single most powerful incentive in the generic drug industry. The first generic applicant to file a “substantially complete” ANDA containing a Paragraph IV certification and successfully navigate the ensuing legal challenges is granted the exclusive right to market their generic for 180 days.19 During this six-month period, the FDA is barred from approving any subsequent ANDAs for the same drug.

This creates a temporary duopoly between the brand-name drug and the first generic.25 In this environment, the first generic can price its product at only a modest discount to the brand (often just 15-25% lower) and rapidly capture a massive portion of the market share.25 The profits earned during this period can be astronomical, often reaching hundreds of millions of dollars for a blockbuster drug, and are essential for offsetting the significant financial risks and legal costs of the patent challenge itself.13 Without the potential reward of this exclusivity period, few generic companies would have the incentive to undertake the expensive and uncertain process of patent litigation.

The Process in Motion: Notice Letters and the 45-Day Countdown

Filing a Paragraph IV certification sets in motion a strict, legally mandated sequence of events that every analyst must understand to build an accurate timeline.

- FDA Acknowledgment: First, the generic company submits its ANDA to the FDA. The agency then reviews it for completeness and, if satisfactory, sends an acknowledgment letter to the applicant confirming the application has been received for review.

- The Notice Letter: Upon receiving this acknowledgment, a 20-day clock starts ticking. Within this window, the generic applicant must send a formal “notice letter” to both the brand-name company (the NDA holder) and the owner of the patent(s) being challenged.18 This isn’t a simple notification; it is a detailed legal document that must lay out the full factual and legal basis for the generic’s claim that the patent is invalid or not infringed.

- The 45-Day Countdown: The moment the brand company receives this notice letter, a new, even more critical clock begins: a 45-day countdown.16 The brand manufacturer has exactly 45 days to decide whether to file a patent infringement lawsuit against the generic challenger.

This 45-day decision is the pivot point upon which the entire timeline for generic entry turns. If the brand does not sue within this window, the FDA can approve the ANDA as soon as its scientific review is complete (assuming no other patents or exclusivities are in the way). But if the brand does sue—which it almost invariably does for a valuable product—it triggers the next major phase of the process: the legal battle and the automatic 30-month stay.

The Legal Battlefield: Litigation, Stays, and Settlements

Once the brand-name manufacturer files a patent infringement suit within the 45-day window, the conflict moves from regulatory filings to the federal courtroom. This initiates a complex and often lengthy legal process governed by the unique rules of the Hatch-Waxman Act. For forecasters, this phase introduces the most significant variables affecting the generic launch timeline: the 30-month stay, the unpredictable nature of litigation, and the high probability of a negotiated settlement.

The 30-Month Stay: A Shield for Brands, A Hurdle for Generics

The filing of the lawsuit immediately triggers one of the most powerful defensive tools available to brand companies: the automatic 30-month stay of approval.14 This provision automatically bars the FDA from granting final approval to the generic applicant’s ANDA for a period of up to 30 months from the date the brand received the Paragraph IV notice letter.17

This stay is, in effect, an automatic preliminary injunction granted by statute, without the brand company having to prove to a court that it is likely to win the case. It provides the brand with a guaranteed period of continued market exclusivity, giving it valuable time to prepare for the eventual generic entry by implementing lifecycle management strategies, building up inventory of an authorized generic, or negotiating a favorable settlement.25

However, the 30-month stay is not absolute. It can be terminated earlier if a court rules in favor of the generic company (i.e., finds the patent invalid or not infringed) or if the litigation is otherwise resolved.16 Conversely, a judge can also shorten or extend the stay depending on the conduct of the parties during the litigation.

While the 30-month stay is a well-known feature of the Hatch-Waxman landscape, it’s crucial to recognize that it is often not the final rate-limiting step. Data from one comprehensive study revealed a median gap of 3.2 years between the expiration of the 30-month stay and the actual launch of the generic drug. This indicates that the stay is a predictable, early-stage delay. The real uncertainty and the source of longer delays often stem from the full duration of the litigation itself, including appeals, and the brand’s strategic deployment of additional patents to create new barriers to entry. An analyst who focuses only on the 30-month clock will almost certainly produce an inaccurate and premature forecast.

The Reality of Hatch-Waxman Litigation

Hatch-Waxman patent litigation is a highly specialized field. The cases typically revolve around two core arguments from the generic challenger:

- Non-infringement: The generic company argues that the specific formulation or manufacturing process of its product does not fall within the scope of the brand’s patent claims.

- Invalidity: The generic company argues that the brand’s patent should never have been granted by the PTO in the first place because it is “obvious” in light of prior art or fails to meet other statutory requirements for patentability.

These cases are most often litigated in a few key federal district courts, historically the District of Delaware and the District of New Jersey, due to their judges’ deep expertise in complex patent law. The median time to trial for patent cases is around 24.5 months, which fits neatly within the 30-month stay period, but appeals can extend the process significantly longer.

In recent years, another critical venue has emerged: the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) at the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. Generic companies can file a parallel challenge to a patent’s validity at the PTAB through a process called Inter Partes Review (IPR). IPRs are often faster and cheaper than district court litigation and have a notoriously high rate of invalidating patent claims—in some years, over 70% of claims that go to a final written decision are found unpatentable.31 A successful IPR can put immense pressure on the brand company in the parallel district court case and can significantly accelerate a settlement.

The Art of the Deal: Why Most Cases Settle

Despite the high stakes, the vast majority of Hatch-Waxman cases do not go to a final verdict. Instead, they are resolved through a settlement agreement. The economic logic is compelling for both sides.

- For the Brand Company: Litigation carries the existential risk of having a key patent invalidated, which would open the floodgates to immediate and widespread generic competition. A settlement allows the brand to trade this risk for a certain, negotiated generic entry date, often years before the patent was set to expire but later than would occur if they lost the lawsuit.

- For the Generic Company: Litigation is incredibly expensive and the outcome is never guaranteed. A settlement provides a certain date of market entry, eliminating risk and allowing the company to plan its launch with confidence.

These settlements can be complex, but they often involve a “pay-for-delay” or “reverse payment” component, where the brand manufacturer provides some form of compensation to the generic challenger in exchange for an agreement to delay their market entry. This compensation can be a direct cash payment or, more subtly, an agreement by the brand not to launch its own “authorized generic” to compete during the first-filer’s 180-day exclusivity period. These agreements have come under intense scrutiny from the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), which argues they are anti-competitive and cost consumers billions of dollars by delaying access to cheaper medicines.

The Grand Prize: The 180-Day Exclusivity Period

At the heart of every Paragraph IV challenge lies the pursuit of the ultimate prize in the generic pharmaceutical world: the 180-day marketing exclusivity period. This powerful incentive, created by the Hatch-Waxman Act, is the primary economic engine driving generic companies to undertake the immense risks and costs of patent litigation.19 Understanding the value, mechanics, and strategic implications of this exclusivity is absolutely essential to forecasting generic entry and market dynamics.

The Economics of Exclusivity

The 180-day exclusivity period is a game-changer because it fundamentally alters the competitive landscape. Instead of a “patent cliff” where a brand’s monopoly is immediately replaced by a flood of low-cost generics, the exclusivity period creates a temporary, six-month duopoly consisting of only the brand-name drug and the first-to-file generic.

This limited competition allows the first generic entrant to command a much higher price than would be possible in a crowded market. While prices for generics can eventually fall by 80-90% or more, the first generic typically enters at a price only 15-30% below the brand.25 This combination of significant market share capture and relatively high prices makes the 180-day period extraordinarily profitable.

“The U.S. Supreme Court has noted that this 180-day exclusivity period can be worth ‘several hundred million dollars’ to generic manufacturers, with financial rewards for blockbuster drugs potentially reaching hundreds of millions of dollars.”

This potential windfall is what justifies the millions of dollars spent on legal fees and the risk of facing a massive damages award if the patent challenge fails. It is the reward for being the first to successfully break down the patent barriers protecting a lucrative drug.

Earning and Losing the Prize: Forfeiture Events

Eligibility for 180-day exclusivity is not a permanent right; it is a privilege that can be lost. Initially, some first-filers would “park” their exclusivity by settling with the brand for a delayed entry date, effectively blocking all other generic competitors from entering the market in the interim. To combat this, the Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act of 2003 (MMA) introduced a series of forfeiture provisions.17

These provisions create a “use it or lose it” dynamic. A first applicant can forfeit its exclusivity if it fails to take certain actions, thereby allowing the next eligible generic applicant to be approved. Key forfeiture events include:

- Failure to Market: The first applicant fails to market its drug within a specified timeframe (e.g., 75 days) after a final court decision in its favor or after another generic’s ANDA is approved.17

- Withdrawal of Application: The first applicant withdraws its ANDA or amends its patent certification from a Paragraph IV to a Paragraph III.17

- Failure to Obtain Tentative Approval: The first applicant fails to obtain a tentative approval from the FDA within a specified period (typically 30 months) after its ANDA was filed.17

- Agreement with Another Applicant: The first applicant enters into an anti-competitive agreement with the brand company or another generic that is found to violate antitrust laws.

These forfeiture provisions are critical for analysts to track, as they can dramatically alter the competitive timeline. The failure of a first-filer to secure its exclusivity can open the door for the second or third filer to launch much earlier than anticipated.

The Brand’s Countermove: The Authorized Generic (AG)

Even when a generic company successfully wins 180-day exclusivity, the brand-name manufacturer has a powerful countermove: the authorized generic (AG). An AG is the exact same product as the brand-name drug, produced by the brand company itself (or a partner), but marketed without the brand name and sold at a generic price.

By launching an AG during the 180-day exclusivity period, the brand company can compete directly with the first generic challenger. This move has a devastating impact on the first-filer’s profitability. An FTC report found that the presence of an AG reduces the first generic’s revenues by an average of 40% to 52% during the exclusivity period and by 53% to 62% in the 30 months that follow.

The AG is a potent strategic weapon. The mere threat of launching an AG gives the brand company significant leverage in settlement negotiations. As the FTC has noted, a common component of “pay-for-delay” settlements is an explicit promise from the brand not to launch an AG in exchange for the generic agreeing to a later entry date. For analysts, monitoring a brand’s corporate structure for generic subsidiaries or its history of launching AGs is a key indicator of its likely defensive strategy.

The Analyst’s Toolkit: Turning Data into Competitive Advantage

Understanding the intricate dance of regulations, litigation, and strategy is one thing; translating that understanding into an accurate, actionable forecast is another. This requires a systematic approach to gathering and synthesizing data from a variety of sources. Fortunately, the highly regulated nature of the pharmaceutical industry means that a wealth of information is publicly available—if you know where to look and how to connect the dots.

Mastering the Public Domain: FDA Databases

The FDA maintains several publicly accessible databases that are the foundational building blocks of any generic entry forecast. These resources provide the raw data on patents, exclusivities, and application statuses.

The Orange Book: The IP Blueprint

The Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations, or Orange Book, is the official register of all FDA-approved drugs, their patents, and their exclusivities.14 For any analyst, this is ground zero. A thorough review of a brand drug’s Orange Book listing will reveal:

- All listed patents: Including their expiration dates.

- Patent Use Codes: These codes describe what the patent covers (e.g., “U-123” might refer to a method of treating a specific condition), which is critical for understanding “skinny label” strategies where a generic might launch for only non-patented indications.

- All applicable exclusivities: NCE, ODE, pediatric, etc., and their expiration dates.

By mapping out these dates, you can create a baseline IP timeline and identify the earliest possible dates for generic entry via a non-confrontational Paragraph III filing.

Drugs@FDA: The Regulatory Dossier

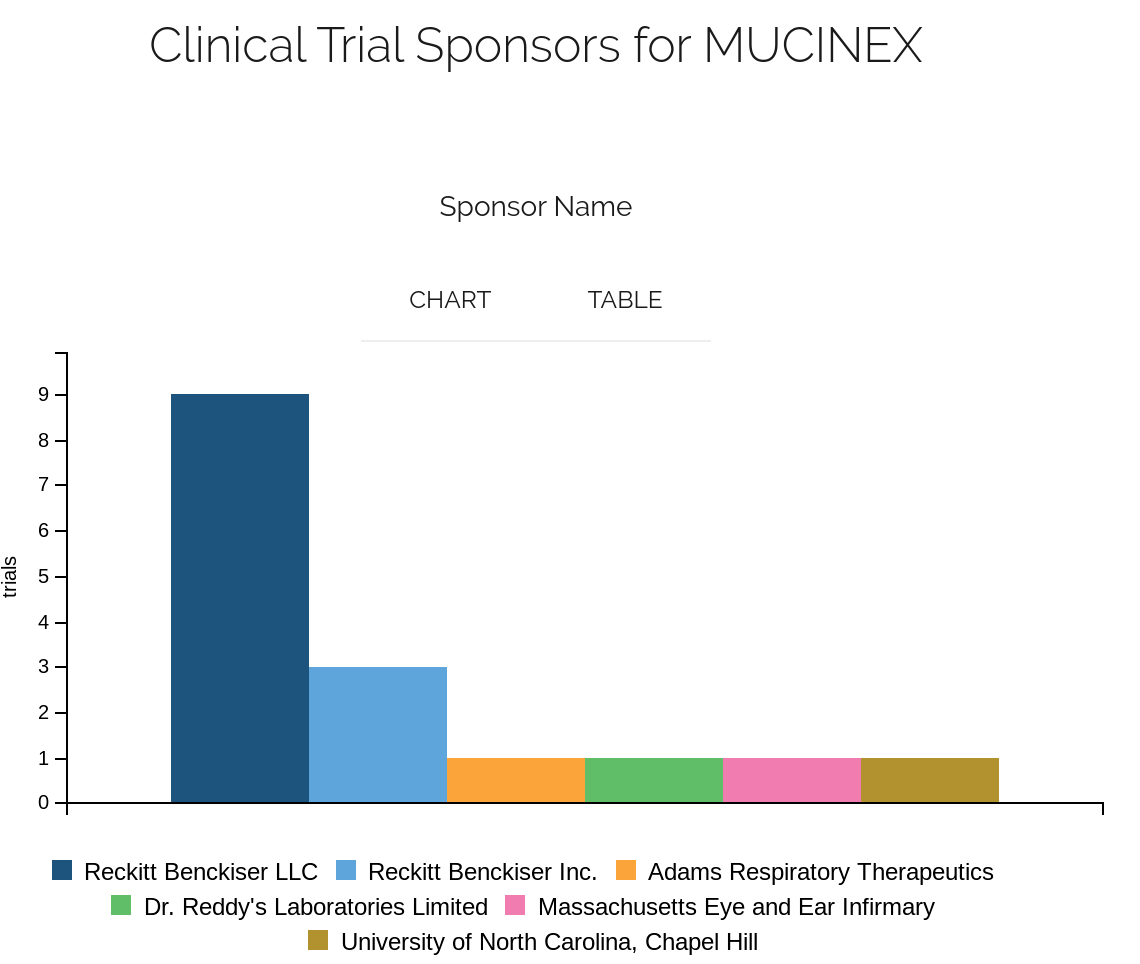

The Drugs@FDA database is a searchable catalog of FDA-approved drug products.39 Its primary value for forecasting lies in its detailed information on individual applications. By searching for a generic drug by its active ingredient, you can:

- Identify all ANDA filers: See which companies have submitted applications for a specific brand drug.

- Check Application Status: Crucially, this is where you can determine if an ANDA has been fully approved or has received a tentative approval.14

- Access Regulatory Documents: For applications approved since 1998, the database often provides access to key documents, including the approval or tentative approval letter, which can provide clues about the specific patents or exclusivities that are blocking final approval.14

The Paragraph IV Certification List: The Challenger Roster

Perhaps the most valuable, yet often underutilized, FDA resource is the Paragraph IV Patent Certifications List. This list, updated regularly, provides a clear view of which drugs are being actively challenged. For each drug, it details:

- RLD Name and NDA Number: Identifies the brand-name drug being targeted.

- Date of First PIV Submission: This is a critical data point. It reveals the exact date that the first substantially complete ANDA with a Paragraph IV certification was filed, establishing who is in the running for 180-day exclusivity.

- Number of Potential First Applicant ANDAs Submitted: This column is a goldmine of competitive intelligence. It tells you not just that a challenge has occurred, but how many companies filed on that first day. If this number is “1,” you are likely looking at a single first-filer. If it is “3,” you know that three companies are eligible to share the 180-day exclusivity, which will lead to more aggressive pricing during that period.

The Power of Integration: Using Commercial Intelligence Platforms

While FDA databases provide the essential raw data, the information is often fragmented. The Orange Book has patent data, Drugs@FDA has approval statuses, and court dockets have litigation information. Connecting these disparate pieces to form a coherent strategic picture can be a time-consuming and manual process.

This is where commercial competitive intelligence platforms become indispensable. Services like DrugPatentWatch are designed to aggregate, integrate, and analyze this information, providing a holistic and actionable view of the competitive landscape.44 These platforms offer several key advantages:

- Integrated Data: They link a drug’s patent and exclusivity data directly to its ANDA filers, tentative approvals, and ongoing litigation, saving analysts countless hours of manual cross-referencing.44

- Alerts and Monitoring: You can set up alerts to be notified immediately of key events, such as a new Paragraph IV filing, a new tentative approval, or a key court ruling, allowing you to react in real-time.

- Advanced Analytics: These platforms provide tools to search and filter data in sophisticated ways, helping to identify trends, assess the past success of patent challengers, and inform portfolio management decisions.25

By leveraging such a platform, you can move from simple data collection to true business intelligence, focusing your energy on strategic analysis rather than manual data assembly.

Building Your Forecasting Model: A Step-by-Step Approach

Armed with these tools and a deep understanding of the regulatory process, you can now build a robust, multi-stage forecasting model to anticipate generic entry.

- Identify the Target: Begin by selecting a high-revenue brand-name drug. Analyze its sales data and use the Orange Book to determine the expiration date of its core composition-of-matter patent. This date represents the “worst-case” scenario for the brand, the latest date a generic could enter without a patent challenge.

- Monitor for the First Signal: Set up alerts (e.g., in DrugPatentWatch) to monitor for the first Paragraph IV certification against the target drug. The “Date of First PIV Submission” on the FDA’s list officially starts the clock. Note the number of first-day filers.

- Map the IP Landscape: Conduct a deep dive into the brand’s full patent portfolio. Go beyond the core patent and identify all secondary patents covering formulations, methods of use, and manufacturing processes. These “patent thickets” are the brand’s second line of defense and are the most likely source of delays beyond the initial 30-month stay.22

- Track the Litigation Timeline: Once the brand files suit (within 45 days), a 30-month stay begins. Mark this date on your calendar, but treat it as a milestone, not a launch date. Begin actively tracking the litigation in federal court and any parallel IPR proceedings at the PTAB. Key events to watch for include claim construction (Markman) hearings, summary judgment motions, trial dates, and, most importantly, any signs of settlement negotiations.

- Watch for Tentative Approvals: The issuance of the first TA is a major confirmation signal. It validates that the generic is scientifically and regulatorily ready to launch. Continue to track the number of TAs granted; the more TAs that are issued, the more intense the competition will be on day one post-exclusivity.

- Assess the Brand’s Defensive Posture: Analyze the brand company’s past behavior. Do they have a history of launching authorized generics? Are they actively developing a next-generation product to “product hop” patients to before the patent expires? Are they known to settle early or litigate to the bitter end?

- Develop and Refine Scenarios: Based on the progress of the litigation and the strength of the remaining patents, develop multiple launch scenarios:

- Best-Case (for Generic): The generic wins a key summary judgment motion or IPR, invalidating the core patent and leading to an early settlement or an “at-risk” launch.

- Most-Likely Case: The case settles, with a negotiated entry date that is typically 1-3 years before the patent’s natural expiration.

- Worst-Case (for Generic): The generic loses the initial litigation and must wait for the patent to expire or win on appeal, a process that can take several years.

This systematic, data-driven approach transforms forecasting from a guessing game into a strategic discipline, allowing you to anticipate market shifts with a much higher degree of confidence.

From Theory to Practice: In-Depth Case Studies

The principles and processes we’ve discussed are not just theoretical constructs; they are the real-world rules of engagement that determine the fate of billion-dollar drug markets. To see how these dynamics play out, let’s examine the generic launches of three iconic blockbuster drugs: Lipitor, Plavix, and Abilify. Each case study offers a unique lesson in brand defense, generic strategy, and the critical role of the regulatory and legal framework.

Case Study 1: The Fortress – Defending Lipitor (Atorvastatin)

Pfizer’s Lipitor was, for a time, the best-selling drug in the history of the pharmaceutical industry. Its loss of exclusivity was a monumental event, and Pfizer’s defense provides a masterclass in strategic lifecycle management and managing a patent cliff.

- The Challenge: The primary patent on atorvastatin was set to expire in 2011. The first Paragraph IV challenge was filed by Indian generic manufacturer Ranbaxy Laboratories.

- The Brand’s Strategy – A Multi-Pronged Defense: Pfizer didn’t rely on a single tactic; it built a fortress.

- Litigate and Settle: Pfizer sued Ranbaxy for patent infringement, triggering the 30-month stay. Rather than risk losing the patent in court, Pfizer eventually reached a settlement with Ranbaxy. This agreement was a strategic masterstroke: it delayed Ranbaxy’s generic entry by several months past the patent expiry date, giving Pfizer more time to prepare.

- Launch an Authorized Generic (AG): Pfizer knew that even with the delay, Ranbaxy would eventually enter with 180-day exclusivity. To counter this, Pfizer struck a deal with Watson Pharmaceuticals (now part of Teva) to launch an authorized generic version of Lipitor on the very first day of Ranbaxy’s exclusivity period. This immediately cut the first-filer’s market in half and significantly diluted the value of the exclusivity prize.

- Aggressive Marketing and Rebates: In the years and months leading up to the patent expiry, Pfizer invested heavily in direct-to-consumer advertising to build immense brand loyalty, famously using the slogan, “I take Lipitor instead of a generic”. It also offered deep rebates and discounts to pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) and insurance companies to keep brand-name Lipitor on preferred formulary tiers, even at a price competitive with the initial generics.50

- The Outcome: Pfizer’s strategy was remarkably successful. While it could not prevent the eventual erosion of Lipitor’s market share, its multi-layered defense allowed it to manage the decline gracefully, maximize revenue in the final years of exclusivity, and capture a significant portion of the initial generic market through its AG. The case demonstrated that a well-executed defensive strategy could turn a catastrophic patent cliff into a manageable business transition. The aftermath still showed the power of generics; total atorvastatin use increased by 20% while total expenditures decreased by 23% in the years following generic entry, though persistent brand use still led to an estimated $2.1 billion in “excessive waste”.

Case Study 2: The Workaround – The Battle for Plavix (Clopidogrel)

The genericization of the blockbuster antiplatelet drug Plavix, co-marketed by Bristol-Myers Squibb and Sanofi, illustrates a different kind of strategic battle—one focused on scientific creativity and navigating a complex international patent landscape.

- The Challenge: The core patent on Plavix covered a specific crystalline form of clopidogrel bisulfate. A Canadian generic company, Apotex, attempted an “at-risk” launch in 2006, but was ultimately shut down by the courts and forced to pay massive damages. This initial failure, however, did not deter other challengers.

- The Generic Strategy – Scientific Innovation: Instead of directly challenging the main patent, other generic manufacturers, particularly in Europe, pursued a clever workaround. They developed alternative salt forms of clopidogrel, such as clopidogrel besylate, arguing that these forms did not infringe the brand’s patents on the bisulfate salt. This allowed them to design around the core IP.

- Regulatory and Market Complexity: This strategy created a complex situation. Early European generics were approved with different salt forms and often for a “skinny label”—a limited set of indications that were not covered by later-expiring method-of-use patents. This raised concerns among physicians and regulators about bioequivalence and potential differences in clinical outcomes, which the brand company sought to exploit.53 The situation was further complicated by an EMA recall of some generic clopidogrel products due to manufacturing issues in India.

- The Outcome: Despite the brand’s efforts to sow doubt and the initial complexities, the generic strategy ultimately succeeded. Health authorities across Europe adopted pragmatic measures, including physician education and compulsory generic substitution, to encourage the uptake of the lower-cost alternatives. When the U.S. patent finally expired in 2012, the FDA approved numerous generic versions from multiple manufacturers simultaneously, leading to a rapid collapse in price and market share for brand-name Plavix. The Plavix case highlights that even the strongest patents can sometimes be circumvented through scientific ingenuity and that a brand’s defense must anticipate not just legal challenges, but scientific ones as well.

Case Study 3: The High-Stakes Bet – Abilify’s “At-Risk” Launch

The story of generic Abilify (aripiprazole), an atypical antipsychotic from Otsuka and Bristol-Myers Squibb, is a quintessential example of a brand attempting to leverage a secondary exclusivity to protect a blockbuster franchise and a generic company making a calculated, high-stakes bet to launch “at risk.”

- The Challenge: The main patent on Abilify was set to expire in April 2015. Multiple generic companies, including Teva, Alembic, and Torrent, filed Paragraph IV certifications and received tentative approvals.

- The Brand’s Strategy – The Orphan Drug Gambit: In a last-ditch effort to extend its monopoly, Otsuka secured FDA approval for Abilify to treat a rare pediatric condition, Tourette’s syndrome, in late 2014. Because Tourette’s is an orphan disease, this new indication came with seven years of Orphan Drug Exclusivity (ODE). Otsuka then argued in court that this new exclusivity should block all generic versions of Abilify—for all indications, including schizophrenia and bipolar disorder—until 2021.

- The Generic Counter – The “At-Risk” Launch: The generic challengers fought back, arguing that orphan drug exclusivity is indication-specific and could not be used to protect the massive, non-orphan uses of the drug. In April 2015, a federal court denied Otsuka’s request for a temporary restraining order to block the generics, finding its legal argument was unlikely to succeed. This was the critical signal. Although Otsuka’s litigation was not fully resolved and appeals were still possible, Teva and other generic manufacturers made a strategic decision. On April 28, 2015, they launched their generic versions “at risk”.56

- The Outcome: The bet paid off. The courts ultimately affirmed that the orphan drug exclusivity for Tourette’s did not protect the other indications, and the generic launch proceeded. An “at-risk” launch is one of the riskiest maneuvers in the pharmaceutical playbook. If the generic company is ultimately found to be infringing a valid patent, it can be liable for massive damages, potentially including the brand’s lost profits and even treble damages for willful infringement. However, as the Abilify case shows, after a significant legal victory that substantially de-risks the litigation, a company with a tentative approval and a mature supply chain can seize the first-mover advantage and enter the market, transforming the competitive landscape overnight.

These cases reveal the dynamic, strategic interplay between brand and generic companies. The following table summarizes the common moves and counter-moves in this high-stakes game.

| Brand-Name Tactic | Strategic Goal | Generic Counter-Strategy | Strategic Goal |

| Patent Thicket Creation | Delay/deter entry by increasing litigation cost and complexity. | Paragraph IV Challenge on core patents + Inter Partes Review (IPR) on weaker secondary patents. | Invalidate key patents to clear a path to market; gain 180-day exclusivity. |

| Filing Lawsuit to Trigger 30-Month Stay | Gain a guaranteed 30 months of continued monopoly to prepare defenses and negotiate. | Vigorously litigate to win before the stay expires; prepare for an “at-risk” launch immediately upon stay expiration. | Shorten the delay; seize market share before appeals are exhausted. |

| Launching an Authorized Generic (AG) | Capture a portion of generic revenue; significantly dilute the value of the 180-day exclusivity prize. | Price aggressively to gain market share from both the brand and the AG; focus on securing PBM contracts. | Mitigate the financial impact of the AG and establish a strong market foothold. |

| “Pay-for-Delay” Settlement | Control the generic entry date to maximize brand revenue; avoid the risk of losing the patent in court. | Accept a settlement for a guaranteed entry date and potentially a no-AG promise. | Secure a profitable, risk-free market entry and avoid further litigation costs. |

| Filing a Citizen Petition with the FDA | Create non-patent-related regulatory delays by raising questions about the generic’s safety or equivalence. | Challenge the petition’s scientific merits at the FDA; argue in court that it is a sham intended only to delay competition. | Overcome non-scientific hurdles and prevent last-minute roadblocks to approval. |

The Future of Generic Competition: Emerging Trends and Strategic Imperatives

The intricate dance between brand and generic manufacturers, choreographed by the Hatch-Waxman Act, is not static. The landscape is constantly evolving, shaped by new technologies, shifting regulatory priorities, and mounting political pressure over drug prices. As we look to the future, several key trends are poised to redefine the strategic imperatives for all players in the pharmaceutical ecosystem.

The Shifting Regulatory and Legal Sands

The very tactics that have defined brand defense strategies for decades are coming under increasing fire. Practices like “patent thickets”—where companies build a dense web of overlapping, often weak, secondary patents to deter challenges—and “pay-for-delay” settlements are facing intense scrutiny from the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), Congress, and the public.34 There is a growing political will to curb what are perceived as abuses of the patent system designed to stifle competition beyond what was intended by the Hatch-Waxman Act. This suggests that relying solely on legal maneuvering to extend a product’s lifecycle will become an increasingly risky and less sustainable strategy for brand-name companies.

Paradoxically, the very success of the generic drug model has created its own set of challenges. The relentless downward pressure on prices has made the market for many simple generics so competitive that profit margins have become razor-thin. This has led some manufacturers to exit certain markets altogether, contributing to a rise in drug shortages for essential, low-cost medications like sterile injectables.61 As Marta Wosińska, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, notes, “The price pressure on manufacturers is tremendous… At the heart of the issue is the market does not reward quality and reliability”. This market fragility presents both a challenge for public health and a strategic opportunity for generic companies with robust and reliable supply chains.

The Rise of Complex Generics and Biosimilars

While the market for simple small-molecule drugs becomes more commoditized, the next frontier of competition lies in complex generics and biosimilars. Complex generics—such as drug-device combinations, long-acting injectables, or transdermal patches—are scientifically more difficult to replicate and require more extensive proof of equivalence. Biosimilars, which are the “generic” versions of large-molecule biologic drugs, face an even higher bar for approval under a separate regulatory pathway.

The principles of patent challenges and market exclusivity still apply, but the scientific and manufacturing hurdles add another layer of complexity to forecasting. A tentative approval for a complex generic or a biosimilar is an even stronger signal of a company’s technical prowess and readiness to compete.

Strategic Imperatives for the Next Decade

The pharmaceutical industry is currently staring down the most significant patent cliff in its history. Between 2025 and 2030, dozens of high-revenue products are projected to lose exclusivity, putting an estimated $236 billion to $400 billion in annual revenue at risk.63 This unprecedented wave of expirations will intensify all the competitive dynamics we have discussed, making strategic foresight more critical than ever.

- For Brand-Name Manufacturers: The imperative is to shift from a primary focus on legal defense to a renewed focus on genuine innovation. While intelligent lifecycle management and patent strategy will always be important, the long-term survival of innovator companies will depend on their ability to build robust pipelines that can replace lost revenue with new, high-value therapies.

- For Generic Manufacturers: The future belongs to those who can master complexity. This means not only navigating the legal intricacies of Paragraph IV litigation but also developing the scientific capabilities to produce complex generics and biosimilars. Sophisticated portfolio selection will be key, focusing on products that offer a durable market opportunity and a manageable litigation risk profile.

- For All Stakeholders: In this evolving and increasingly competitive environment, the ability to read the regulatory tea leaves is no longer just an advantage—it is a core competency for survival. Understanding the signals embedded in the FDA’s actions, particularly the issuance of a tentative approval, provides the critical foresight needed to anticipate market shifts, allocate resources effectively, and make the strategic decisions that will separate the winners from the losers in the decade to come.

Key Takeaways

- Tentative Approvals are Powerful Predictors: A tentative approval from the FDA is a definitive signal that a generic drug is scientifically and regulatorily ready for market, with only intellectual property (patents or exclusivities) standing in the way. It removes scientific and manufacturing uncertainty from the forecasting equation.

- The Hatch-Waxman Act Created a “Game”: The Act established a structured, timeline-driven process for patent challenges, including the Paragraph IV certification, the 45-day window to sue, the 30-month stay, and the 180-day exclusivity prize. Understanding these “rules of the game” is crucial for predicting the sequence and timing of events.

- Paragraph IV and 180-Day Exclusivity Drive the Market: The pursuit of the highly lucrative 180-day exclusivity period is the primary economic incentive for generic companies to challenge brand-name patents via a Paragraph IV certification. This exclusivity creates a temporary duopoly, allowing for significant profit-taking.

- The 30-Month Stay is Not the Final Hurdle: While the 30-month stay provides a predictable initial delay, data shows that generic launch often occurs years after it expires. The true timeline is dictated by the full length of litigation (including appeals), settlement negotiations, and the brand’s use of secondary patents (“patent thickets”).

- Data Synthesis is Key to Accurate Forecasting: Effective forecasting requires synthesizing data from multiple sources. Public FDA databases (Orange Book, Drugs@FDA, Paragraph IV List) provide the raw data, while commercial intelligence platforms like DrugPatentWatch integrate this information to provide a holistic, actionable view of the competitive landscape.

- Brand and Generic Strategies are a Chess Match: Both sides employ sophisticated tactics. Brands use patent thickets, authorized generics, and settlements to defend their franchises. Generics use Paragraph IV challenges, IPRs, and “at-risk” launches to break through these defenses. Analyzing these strategic patterns is essential for anticipating outcomes.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. How long does it typically take for a generic drug to receive final approval after obtaining a tentative approval?

The timeline can vary dramatically, from a few months to several years. It is not determined by a fixed FDA clock but by the resolution of the intellectual property blocking the final approval. If the block is a patent that is nearing its expiration date, the conversion to final approval may be quick and predictable. However, if the block is a patent being actively litigated following a Paragraph IV challenge, the timeline depends entirely on the litigation’s outcome. This could be resolved relatively quickly through a settlement, or it could extend for years through trial and appeals. A key insight is that the median time from the expiration of the 30-month litigation stay to actual generic launch is over three years, indicating that the litigation itself, not just the initial stay, is the primary determinant of the timeline.

2. How accurate are tentative approvals in predicting the actual timing of generic market entry?

Tentative approvals are highly accurate in predicting that a specific generic competitor is prepared to enter the market, but they are not a precise predictor of the timing of that entry on their own. A TA confirms that all scientific and manufacturing hurdles have been cleared, which is a major milestone. However, the actual launch date is contingent on external factors like patent expiration dates, the duration and outcome of patent litigation, and potential settlement agreements between the brand and generic companies.1 The most effective forecasting uses the TA as a key confirmation signal within a broader model that also tracks the legal and strategic landscape.

3. Can multiple generic manufacturers receive tentative approval for the same drug, and what does that imply for the market?

Yes, absolutely. It is very common for multiple generic manufacturers to file ANDAs and subsequently receive tentative approvals for the same brand-name drug. This is a critical piece of competitive intelligence. The number of tentative approvals is a direct indicator of the level of competition that will emerge once the patents and exclusivities expire. A single TA might suggest a more orderly market, at least initially. However, if five or six companies have TAs, it signals that upon the resolution of the IP, the market will immediately become hyper-competitive, leading to rapid and severe price erosion, with prices potentially dropping by 95% or more.46

4. What is an “at-risk” launch, and how does a tentative approval factor into the decision to launch at risk?

An “at-risk” launch occurs when a generic company decides to market its product after the 30-month stay has expired but before all patent litigation, including appeals, has been fully resolved. It’s a high-stakes gamble: the reward is capturing first-mover market share, but the risk is being forced to pay massive damages (potentially triple the brand’s lost profits) if the patent is ultimately upheld. A tentative approval is a prerequisite for even considering an at-risk launch. A company cannot launch any product, at risk or otherwise, without at least a TA that can be converted to a final approval. The TA provides the confidence that the product is regulatorily sound, allowing the company to focus its risk assessment purely on the legal probability of winning the patent case.

5. If a generic company receives a tentative approval, can the brand-name company still prevent its launch indefinitely?

A brand-name company cannot prevent a generic launch indefinitely, but it can employ strategies to delay it significantly. The primary tool is patent litigation. By defending existing patents and strategically filing for and listing new, secondary patents on different formulations or methods of use (creating a “patent thicket”), a brand can create a series of overlapping legal hurdles that a generic company must overcome one by one.22 While a generic with a tentative approval will eventually get to market once the last patent expires, a brand’s legal strategy can mean the difference between a generic launching 12 years after the brand’s approval versus 17 years or more, which can translate into billions of dollars in extended revenue for the brand.

References

- Predicting patent challenges for small-molecule drugs: A cross-sectional study – PMC, accessed August 4, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11867330/

- How to Use Tentative Drug Approvals to Anticipate Generic Entry – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/how-to-use-tentative-drug-approvals-to-anticipate-generic-entry/

- Information for Industry on FDA’s Tentative Approval Process Under the PEPFAR Program, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/media/183851/download

- 40th Anniversary of the Generic Drug Approval Pathway | FDA, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/cder-conversations/40th-anniversary-generic-drug-approval-pathway

- www.fda.gov, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/abbreviated-new-drug-application-anda/hatch-waxman-letters#:~:text=The%20%22Drug%20Price%20Competition%20and,Drug%2C%20and%20Cosmetic%20Act%20(FD%26C

- What is Hatch-Waxman? – PhRMA, accessed August 4, 2025, https://phrma.org/resources/what-is-hatch-waxman

- Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act – Wikipedia, accessed August 4, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Drug_Price_Competition_and_Patent_Term_Restoration_Act

- The Global Generic Drug Market: Trends, Opportunities, and Challenges – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-global-generic-drug-market-trends-opportunities-and-challenges/

- Generic Drugs Market Size, Research, Trends and Forecast – Towards Healthcare, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.towardshealthcare.com/insights/generic-drugs-market

- Competition in Generic Drug Markets | NBER, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.nber.org/digest/nov17/competition-generic-drug-markets

- No Free Launch: At-Risk Entry by Generic Drug Firms, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w29131/w29131.pdf

- Generic Drug Entry Timeline: Predicting Market Dynamics After …, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/generic-drug-entry-timeline-predicting-market-dynamics-after-patent-loss/

- The Hatch-Waxman Act (Simply Explained) – Biotech Patent Law, accessed August 4, 2025, https://berksiplaw.com/2019/06/the-hatch-waxman-act-simply-explained/

- Paragraph IV Explained – ParagraphFour.com, accessed August 4, 2025, https://paragraphfour.com/paragraph-iv-explained/

- Patents and Exclusivities for Generic Drug Products – FDA, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/cder-conversations/patents-and-exclusivities-generic-drug-products

- Hatch-Waxman Act – Practical Law, accessed August 4, 2025, https://uk.practicallaw.thomsonreuters.com/Glossary/PracticalLaw/I2e45aeaf642211e38578f7ccc38dcbee

- The timing of 30‐month stay expirations and generic entry: A cohort study of first generics, 2013–2020, accessed August 4, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8504843/

- STRATEGIES FOR FILING SUCCESSFUL PARAGRAPH IV CERTIFICATIONS, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.ssjr.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/presentations/lawyer_1/61808DC.pdf

- Tips For Drafting Paragraph IV Notice Letters | Crowell & Moring LLP, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.crowell.com/a/web/v44TR8jyG1KCHtJ5Xyv4CK/tips-for-drafting-paragraph-iv-notice-letters.pdf

- The 180-Day Rule Supports Generic Competition. Here’s How …, accessed August 4, 2025, https://accessiblemeds.org/resources/blog/180-day-rule-supports-generic-competition-heres-how/

- Generics Dataset – FDA, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/media/125078/download

- Generic Drugs Program Monthly and Quarterly Activities Report | FDA, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/industry/generic-drug-user-fee-amendments/generic-drugs-program-monthly-and-quarterly-activities-report

- The Role of Patents and Regulatory Exclusivities in Drug Pricing | Congress.gov, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/R46679

- Drug Patents: How Pharmaceutical IP Incentivizes Innovation and Affects Pricing, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.als.net/news/drug-patents/

- Full article: Continuing trends in U.S. brand-name and generic drug competition, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13696998.2021.1952795

- What Every Pharma Executive Needs to Know About Paragraph IV Challenges, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/what-every-pharma-executive-needs-to-know-about-paragraph-iv-challenges/

- FDA’s Draft Guidance for Industry on 180-Day Exclusivity – Duane Morris LLP, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.duanemorris.com/alerts/fda_draft_guidance_for_industry_on_180_day_exclusivity_0317.html

- First Generic Launch has Significant First-Mover Advantage Over Later Generic Drug Entrants – DrugPatentWatch – Transform Data into Market Domination, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/first-generic-launch-has-significant-first-mover-advantage-over-later-generic-drug-entrants/

- The Role of Litigation Data in Predicting Generic Drug Launches – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-role-of-litigation-data-in-predicting-generic-drug-launches/

- Pharmaceutical Patents, Paragraph IV, and Pay-for-Delay – Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of, accessed August 4, 2025, https://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1024&context=ipbrief

- “Hatch-Waxman’s Renegades” by John R. Thomas – Scholarship @ GEORGETOWN LAW, accessed August 4, 2025, https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub/2521/

- Patent Litigation Statistics: An Overview of Recent Trends – PatentPC, accessed August 4, 2025, https://patentpc.com/blog/patent-litigation-statistics-an-overview-of-recent-trends

- What to Expect from the PTAB in 2023: Unpatentability Rates | Crowell & Moring LLP, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.crowell.com/en/insights/client-alerts/what-to-expect-from-the-ptab-in-2023-unpatentability-rates

- Recent Statistics Show PTAB Invalidation Rates Continue to Climb – IPWatchdog.com, accessed August 4, 2025, https://ipwatchdog.com/2024/06/25/recent-statistics-show-ptab-invalidation-rates-continue-climb/id=178226/

- Pay for Delay | Federal Trade Commission, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/topics/competition-enforcement/pay-delay

- FTC Report Examines How Authorized Generics Affect the …, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/news/press-releases/2011/08/ftc-report-examines-how-authorized-generics-affect-pharmaceutical-market

- The Law of 180-Day Exclusivity (Open Access) – Food and Drug Law Institute (FDLI), accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.fdli.org/2016/09/law-180-day-exclusivity/

- Electronic Orange Book – YouTube, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RCk-lEdcvPM

- Frequency of first generic drugs approved through “skinny labeling,” 2021 to 2023 | Journal of Managed Care & Specialty Pharmacy, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.jmcp.org/doi/10.18553/jmcp.2025.31.4.343

- Generic Drug Development | FDA, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/abbreviated-new-drug-application-anda/generic-drug-development

- Drug Approvals and Databases | FDA, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/development-approval-process-drugs/drug-approvals-and-databases

- Drugs – FDA, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs

- Drugs@FDA Database – Dataset – Catalog – Data.gov, accessed August 4, 2025, https://catalog.data.gov/dataset/drugsfda-database

- Patent Certifications and Suitability Petitions – FDA, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/abbreviated-new-drug-application-anda/patent-certifications-and-suitability-petitions

- DrugPatentWatch | Software Reviews & Alternatives – Crozdesk, accessed August 4, 2025, https://crozdesk.com/software/drugpatentwatch

- DrugPatentWatch 2025 Company Profile: Valuation, Funding & Investors | PitchBook, accessed August 4, 2025, https://pitchbook.com/profiles/company/519079-87

- Tracking Generic Drug Launches: A Comprehensive Guide for Pharmaceutical Professionals – DrugPatentWatch – Transform Data into Market Domination, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/customer-success-will-a-generic-version-of-a-drug-launch-and-when/

- Drug Patent Watch: Generic Drug Pricing Requires Market Awareness, Data Analysis, and Stakeholder Collaboration – GeneOnline News, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.geneonline.com/drug-patent-watch-generic-drug-pricing-requires-market-awareness-data-analysis-and-stakeholder-collaboration/

- Stop patent abuse and unleash generic and biosimilar price competition, accessed August 4, 2025, https://accessiblemeds.org/campaign/abuse-patent-system-keeping-drug-prices-high-patients/

- Trends in use of Lipitor after introduction of generic atorvastatin, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.gabionline.net/generics/research/Trends-in-use-of-Lipitor-after-introduction-of-generic-atorvastatin

- Generic Atorvastatin and Health Care Costs – PMC, accessed August 4, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3319770/

- “For Me There Is No Substitute”: Authenticity, Uniqueness, and the Lessons of Lipitor, accessed August 4, 2025, https://journalofethics.ama-assn.org/article/me-there-no-substitute-authenticity-uniqueness-and-lessons-lipitor/2010-10

- Managing the challenges of pharmaceutical patent expiry: a case study of Lipitor, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/309540780_Managing_the_challenges_of_pharmaceutical_patent_expiry_a_case_study_of_Lipitor

- What lessons can be learned from the launch of generic clopidogrel …, accessed August 4, 2025, https://gabi-journal.net/what-lessons-can-be-learnt-from-the-launch-of-generic-clopidogrel.html

- Clinical Outcomes of Plavix and Generic Clopidogrel for Patients Hospitalized With an Acute Coronary Syndrome | Circulation – American Heart Association Journals, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/circoutcomes.117.004194

- FDA Approves Generic Versions of Blood Thinner Plavix | DAIC, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.dicardiology.com/article/fda-approves-generic-versions-blood-thinner-plavix

- FDA Approves Generic Release of Abilify – Tower MSA, accessed August 4, 2025, https://towermsa.com/2015/05/01/fda-approves-generic-release-of-abilify/

- Otsuka’s efforts to block generic Abilify fail | BioPharma Dive, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.biopharmadive.com/news/otsukas-efforts-to-block-generic-abilify-fail/399933/

- Teva Launches Generic Abilify® Tablets in the United States, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.tevausa.com/news-and-media/press-releases/teva-launches-generic-abilify-tablets-in-the-united-states/

- Pharmaceutical Patent Abuse: To Infinity and Beyond! | Association for Accessible Medicines, accessed August 4, 2025, https://accessiblemeds.org/resources/blog/pharmaceutical-patent-abuse-infinity-and-beyond/

- DOJ and FTC Host Second Session on Structural and Regulatory Impediments to Drug Competition | Sheppard Mullin Richter & Hampton LLP – JDSupra, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.jdsupra.com/legalnews/doj-and-ftc-host-second-session-on-8604572/

- Will pharmaceutical tariffs achieve their goals? – Brookings Institution, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/pharmaceutical-tariffs-how-they-play-out/

- Generic drugs in the US are too cheap to be sustainable, experts say – The Guardian, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.theguardian.com/science/2024/jan/18/us-generic-drugs-prices-causing-shortage

- www.drugpatentwatch.com, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-impact-of-drug-patent-expiration-financial-implications-lifecycle-strategies-and-market-transformations/#:~:text=Industry%20analysts%20project%20that%20between,in%20annual%20revenue%20at%20risk.&text=This%20isn’t%20a%20distant,feature%20of%20the%20pharmaceutical%20market.

- Patent Cliff 2025: Impact on Pharma Investors – Crispidea, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.crispidea.com/pharma-investing-patent-cliff-2025/

- The $400 Billion Patent Cliff: Big Pharma’s Revenue Crisis – The American Bazaar, accessed August 4, 2025, https://americanbazaaronline.com/2025/08/04/the-400-billion-patent-cliff-big-pharmas-revenue-crisis-465788/

- The Simple Framework for Finding Generic Drug Winners – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/opportunities-for-generic-drug-development/