In the world of pharmaceuticals, there are moments of predictable, seismic financial impact. The announcement of Phase III clinical trial results. An unexpected FDA approval. But perhaps no event is as systematically significant, as strategically complex, and as financially consequential as the filing of a Paragraph IV drug patent challenge. This isn’t merely a legal skirmish confined to a courtroom; it is the opening move in a billion-dollar chess match that reverberates across research labs, boardrooms, and the trading floors of Wall Street.

For the uninitiated, a Paragraph IV (PIV) filing may seem like a procedural footnote in the lengthy process of bringing a generic drug to market. But for those of us who operate at the nexus of law, finance, and pharmaceuticals, it is the starting gun. It is the first concrete event that transforms a brand-name drug’s patent portfolio from a static legal asset into a dynamic financial instrument with a fluctuating, and now quantifiable, risk profile. The moment a generic manufacturer serves that notice letter, it initiates a cascade of events that can erase billions from a brand company’s market capitalization, create fortunes for a successful generic challenger, and fundamentally alter the competitive landscape for years to come. The stakes are almost impossibly high. Between 2025 and 2030, the pharmaceutical industry is projected to face a patent cliff that puts nearly $236 billion in annual revenue at risk—a cliff whose timing and steepness are often dictated by the outcome of these very challenges.

This report is designed to deconstruct this high-stakes game. We will journey from the legislative halls where the rules were written to the federal courtrooms where patents live or die, and ultimately to Wall Street, where the financial verdict is rendered in real-time. My goal is to provide a definitive resource for business professionals, executives, and investors who need to understand not just what a Paragraph IV challenge is, but what it truly means for their strategies, their portfolios, and their bottom lines. We will explore how a single legal certification can trigger a multi-year, multi-million-dollar litigation marathon, how a brand company can leverage a 30-month regulatory stay to protect billions in revenue, and how a generic challenger can win a prize—180 days of market exclusivity—that can be worth hundreds of millions of dollars.

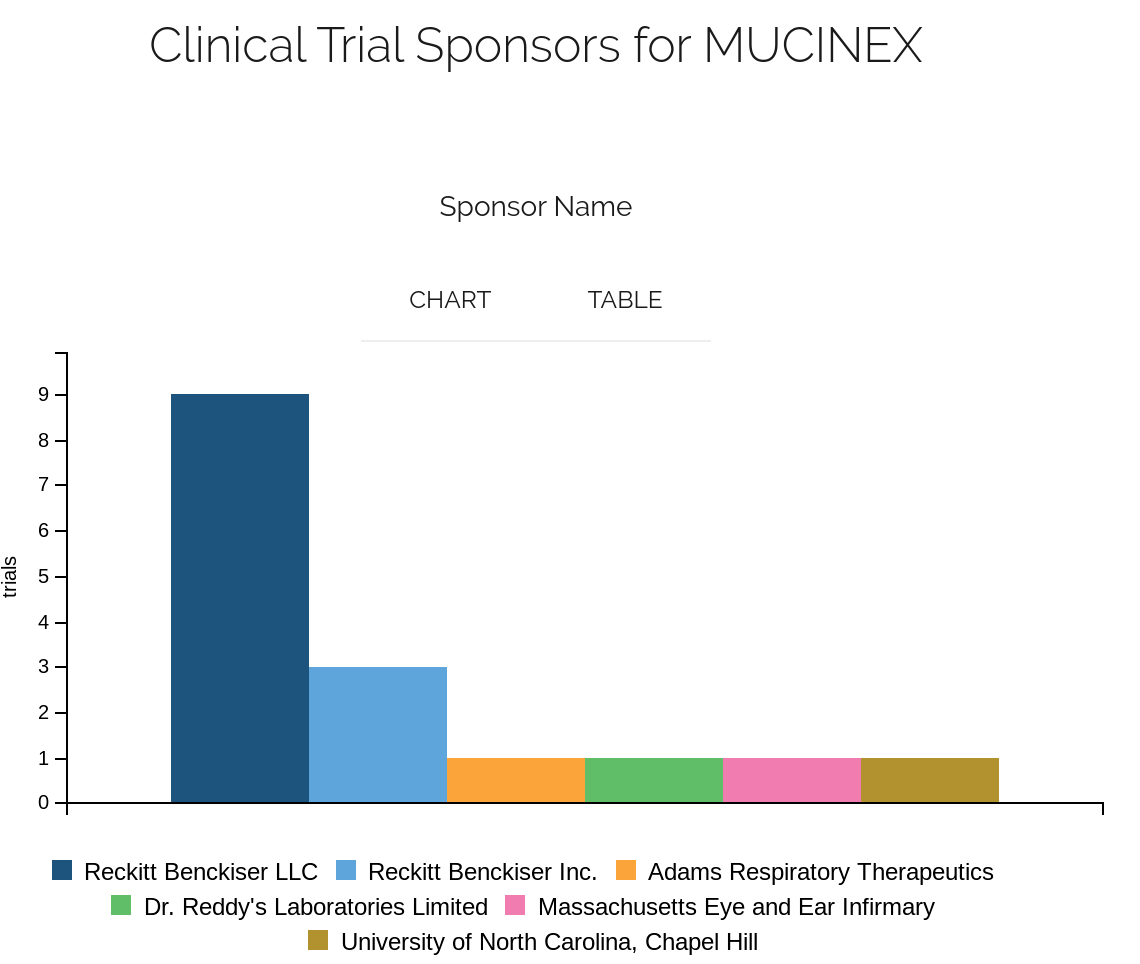

The structured, timeline-driven nature of this process, a legacy of the landmark Hatch-Waxman Act, has done more than just create a legal pathway; it has inadvertently created a new, specialized ecosystem. An entire sub-sector of law firms, consultants, investment funds, and competitive intelligence platforms like DrugPatentWatch now exists solely to analyze, predict, and capitalize on these legal battles.3 The law, in its attempt to balance innovation and access, has fully “financialized” pharmaceutical patent disputes. Understanding this game isn’t just an advantage; in today’s market, it’s a necessity for survival and success. Let’s begin by examining the regulatory bedrock upon which this entire structure is built.

The Regulatory Bedrock: Understanding the Hatch-Waxman Act

To grasp the financial shockwaves of a Paragraph IV challenge, you must first understand the legislative earthquake that created the fault lines. That earthquake was the Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984, known universally as the Hatch-Waxman Act.5 This single piece of legislation, a masterclass in political compromise, is the foundational operating system for the entire U.S. small-molecule drug market. Every strategic decision, every lifecycle plan, and every patent lawsuit is, in essence, a move dictated by the rules and incentives encoded within this act.

The Grand Bargain of 1984

Before 1984, the pharmaceutical landscape was starkly different and, for many, broken. Innovator companies faced a “patent cliff” of their own making; the lengthy FDA approval process could consume a decade or more of a patent’s 20-year term, leaving them with a frustratingly short window to recoup billions in R&D investment.7 On the other side, the generic industry was nascent and struggling. To gain approval, a generic company had to conduct its own expensive and time-consuming clinical trials to prove safety and efficacy, even for a drug that had been on the market for years.5

The situation was brought to a head by a pivotal court case, Roche Products, Inc. v. Bolar Pharmaceutical Co..10 The court ruled that even the act of testing a generic drug for FDA approval

before the brand’s patent expired constituted patent infringement. This decision effectively handed brand companies a de facto patent extension, as generics could only begin their two-to-three-year development and approval process after the patent expired, leaving the brand with several more years of monopoly sales.

Congress, led by Senator Orrin Hatch and Representative Henry Waxman, recognized the need for a compromise. The resulting Hatch-Waxman Act was a grand bargain designed to balance the competing interests of innovation and affordability.5

- For the Brand Innovators: The act provided two crucial benefits. First, it created a mechanism for patent term extension, allowing companies to recapture some of the patent life lost during the FDA’s regulatory review, up to a maximum of five years.1 Second, it established periods of

data exclusivity, most notably a five-year exclusivity for New Chemical Entities (NCEs), during which the FDA could not approve a generic application relying on the innovator’s data.13 These provisions ensured innovators had a protected window to earn a return on their investment. - For the Generic Manufacturers: The act was transformative. It created the Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) process, the cornerstone of the modern generic industry.5 Under an ANDA, a generic firm no longer needed to conduct its own clinical trials. Instead, it could rely on the FDA’s previous finding of safety and effectiveness for the brand-name drug, needing only to demonstrate that its product was bioequivalent.7 Furthermore, the act established a “safe harbor,” overturning the

Roche v. Bolar decision and explicitly allowing generics to conduct R&D activities “reasonably related to the development and submission of information” to the FDA without it being considered patent infringement.5

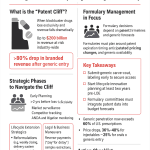

The impact was immediate and profound. Before Hatch-Waxman, generic drugs accounted for a mere 19% of prescriptions filled in the U.S. Today, that figure is over 90%, a testament to the act’s success in creating a robust, competitive market for affordable medicines.5 This legislative framework didn’t just level the playing field; it drew the lines, set the rules, and placed the pieces for the high-stakes chess match to come.

The Orange Book: The Official Battleground Map

If the Hatch-Waxman Act is the rulebook, the FDA’s publication, Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations—better known as the Orange Book—is the official game board.21 This seemingly mundane government document is the linchpin of the entire system, serving as the central, public repository of information that dictates how and when patent challenges can occur.

First published in 1979 and codified by the Hatch-Waxman Act, the Orange Book lists all FDA-approved small-molecule drugs, their approval status, therapeutic equivalence ratings, and, most critically, the patents and regulatory exclusivities that protect them.5 When a brand company submits a New Drug Application (NDA), it is required by statute to provide the FDA with a list of any patents that claim the drug substance (the active pharmaceutical ingredient), the drug product (the formulation or composition), or a method of using the drug.21

It’s just as important to understand what is not listed. Per FDA regulations, patents covering manufacturing processes, packaging, metabolites, or intermediates are not to be included in the Orange Book.21 This distinction is crucial because a generic company filing an ANDA is only required to make a certification against the patents that are properly listed in the Orange Book for the reference drug.25

This makes the Orange Book far more than a simple database; it is a strategic communication tool and a public declaration of a brand’s defensive perimeter.

- For Brand Companies: The act of listing a patent is what makes it eligible for the protections afforded by Hatch-Waxman, including the all-important 30-month stay of generic approval if litigation is initiated. The decision of which patents to list, and how to craft the “use codes” that describe what a method-of-use patent covers, is a critical strategic choice. A poorly described or improperly listed patent can be challenged and potentially delisted, weakening the brand’s defense. This process is the first step in constructing the “patent thicket” designed to deter or delay generic entry.

- For Generic Companies: The Orange Book is a treasure map. It provides a clear, publicly accessible list of the exact patents that must be challenged, invalidated, or designed around to bring a generic product to market. It allows potential challengers to conduct due diligence, assess the strength of a brand’s patent portfolio, and formulate a legal strategy long before filing an ANDA.

In essence, the Orange Book translates the abstract world of patent law into a concrete set of targets. It defines the battlefield, identifies the fortifications, and provides the intelligence necessary for the first shots of the patent war to be fired.

The Paragraph IV Filing: Firing the Starting Gun

The intricate system established by Hatch-Waxman and mapped out in the Orange Book sets the stage for conflict. The mechanism that ignites that conflict, transforming a potential dispute into an active, high-stakes legal and financial event, is the Paragraph IV certification. This is not a passive declaration; it is an aggressive, calculated move designed to provoke a confrontation and accelerate market entry.

What is a Paragraph IV Certification?

When a generic manufacturer files an ANDA, it must address every patent listed in the Orange Book for the brand-name drug it seeks to copy. The Hatch-Waxman Act provides four ways to do this, known as certifications 11:

- Paragraph I Certification: A statement that no patent information has been filed with the FDA.

- Paragraph II Certification: A statement that the patent has already expired.

- Paragraph III Certification: A statement that the generic company will wait to market its product until the patent expires on its stated date.

- Paragraph IV Certification: A statement that, in the generic applicant’s opinion, the listed patent is “invalid, unenforceable, or will not be infringed by the generic product”.25

The first three certifications are straightforward regulatory pathways that result in generic entry after patent protection has lapsed. The Paragraph IV certification, however, is a direct challenge. It is a bold assertion that the brand’s intellectual property fortress is built on sand.

What makes the Paragraph IV certification a masterfully designed legal tool is its status as an “artificial act of infringement” under U.S. patent law (35 U.S.C. § 271(e)(2)).29 This is a crucial legal fiction. Normally, to sue for patent infringement, a patent holder would have to wait until an infringing product is actually made, used, or sold. This would create a high-risk “chicken-and-egg” scenario: the generic would have to launch its product and incur massive commercialization costs, risking catastrophic damages if it later lost the patent suit. The brand, in turn, would suffer immediate and irreversible market share loss while the litigation played out.

The artificial act of infringement solves this dilemma. It gives the brand company immediate legal standing to sue the generic applicant the moment the Paragraph IV certification is made. This allows the entire patent dispute to be litigated and, ideally, resolved before the generic product ever hits the shelves, all within the structured timeline established by the Act. It creates a contained, predictable arena for a battle that would otherwise be chaotic and commercially destructive for both sides.

The Notice Letter: The Formal Declaration of War

The filing of an ANDA with a Paragraph IV certification with the FDA is the internal decision to go to war. The Paragraph IV notice letter is the formal declaration delivered to the enemy’s gate. This is not a simple courtesy notification; it is a legally mandated, strategically critical document that formally initiates the 45-day countdown for litigation.16

By law, the generic applicant must send this notice letter to the brand company (the NDA holder) and the patent owner within 20 days of receiving an acknowledgment from the FDA that its ANDA has been received and is sufficiently complete for a substantive review.29 This timing is strict; sending a notice letter prematurely, before the FDA’s acknowledgment, has been ruled improper by courts, as it could trigger unnecessary litigation over incomplete applications.

The content of the notice letter is equally prescribed. It must include a “detailed statement of the factual and legal basis” for the generic company’s opinion that the patent is invalid, unenforceable, or not infringed.29 This requires the generic company to lay out its initial arguments, citing prior art for invalidity claims or explaining how its product formulation “designs around” the patent’s claims for non-infringement arguments.

The drafting of this letter is one of the first and most crucial strategic decisions in the entire process. It’s a delicate balancing act. The letter must be detailed enough to meet the statutory requirements and establish a good-faith basis for the challenge. A flimsy or poorly reasoned letter can undermine the generic’s credibility from the outset. However, revealing too much can give the brand a premature and overly detailed look into the generic’s litigation playbook.

A powerful, well-crafted notice letter can act as a strategic weapon. It might persuade the brand company that its patent is weaker than it thought, potentially leading it to not assert that specific patent in litigation, thereby narrowing the scope of the dispute. In some cases, a particularly strong notice letter might even prompt the brand to offer an early, favorable settlement to avoid a costly and risky court battle. This document, therefore, is the opening salvo—a carefully calibrated piece of legal and strategic communication that sets the tone for the multi-year, multi-million-dollar conflict to follow. Once it is received, the clock starts ticking for the brand company to make its next move.

The Litigation Lifecycle: A Multi-Year, High-Stakes Marathon

The receipt of a Paragraph IV notice letter forces the brand-name company into a critical decision, but one with a timeline measured in days. The response to this declaration of war sets in motion a litigation process that is anything but swift. It is a multi-year marathon through the U.S. legal system, a high-stakes contest of legal strategy, scientific evidence, and financial endurance. Central to this process is a unique procedural shield granted to the brand: the 30-month stay.

The 30-Month Stay: The Brand’s Most Powerful Shield

If the brand company files a patent infringement lawsuit against the generic applicant within 45 days of receiving the notice letter, it triggers one of the most powerful defensive tools in the Hatch-Waxman arsenal: an automatic 30-month stay of FDA approval for the generic’s ANDA.27 This provision effectively bars the FDA from granting final approval to the generic drug for a period of 30 months from the date the notice letter was received, unless the patent expires or a court rules in the generic’s favor before that time is up.33

From a purely legal perspective, the stay is intended to provide a “reasonable amount of time for patent litigation to resolve” before a potentially infringing product enters the market. From a business and financial perspective, however, the 30-month stay is a golden shield. It represents a guaranteed period of continued market exclusivity, a protected revenue stream that can be worth hundreds of millions, and in the case of blockbuster drugs, billions of dollars.

This transforms the brand’s decision to sue into a straightforward financial calculation, a classic Net Present Value (NPV) analysis. Imagine a blockbuster drug generating $2 billion in annual revenue. The 30-month stay protects approximately $5 billion in sales that would otherwise be immediately at risk from generic competition. The cost of initiating and fighting the litigation might be substantial, perhaps $10 million to $20 million over several years.36 The investment decision is stark: spend $20 million to protect a $5 billion revenue stream. The NPV of this decision is overwhelmingly positive.

This financial reality means that the initial decision to file suit within the 45-day window is often less about the ultimate legal merits of the case and more about the automatic, immediate financial benefit of triggering the stay. It is an almost reflexive defensive move, a low-cost insurance policy that buys the brand company two and a half years of time—time to litigate, time to negotiate a settlement, and time to execute commercial strategies to soften the eventual impact of generic entry.

Key Phases of Hatch-Waxman Litigation

Once the lawsuit is filed and the 30-month stay is in effect, the parties embark on a complex and lengthy litigation process. While each case is unique, they generally follow a predictable series of phases, each with its own strategic importance.

Discovery and Initial Motions

This initial phase involves the exchange of information and documents between the parties. The generic company’s ANDA, which contains the complete details of its proposed product, is a central piece of evidence. The brand company will seek to understand every aspect of the generic’s formulation and manufacturing process to build its infringement case. The generic, in turn, will seek documents from the brand related to the invention and prosecution of the patent to build its invalidity case. This phase can be contentious and lengthy, often involving disputes over the scope of discovery and confidentiality.

Claim Construction: The Decisive Markman Hearing

Perhaps the single most critical phase of any patent litigation is claim construction, often referred to as a Markman hearing. In this proceeding, the judge, not a jury, determines the legal meaning and scope of the key terms used in the patent’s claims. The claims are the numbered sentences at the end of a patent that define the precise boundaries of the invention.

The outcome of the Markman hearing can be dispositive. A broad interpretation of a claim term by the judge might make it easy for the brand to prove infringement, while a narrow interpretation might allow the generic’s product to fall outside the patent’s scope, leading to a judgment of non-infringement. Because this phase is so pivotal, it is heavily litigated. A favorable ruling here can lead to an early settlement or a summary judgment motion that ends the case without a full trial.

Trial and Judgment

If the case does not settle or get resolved on summary judgment, it proceeds to trial. Here, both sides present their evidence and expert testimony on the core issues of infringement and validity. The brand company has the burden of proving, by a “preponderance of the evidence,” that the generic’s product will infringe its patent. The generic company, which is challenging a patent that was duly issued by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO), faces a higher burden: it must prove the patent is invalid by “clear and convincing evidence.” The trial can last for days or weeks, culminating in a decision by the judge (as most Hatch-Waxman cases are bench trials, not jury trials).

The Inevitable Appeal

The district court’s decision is rarely the final word. Given the enormous financial stakes, the losing party almost invariably appeals the decision to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (CAFC). The CAFC is a specialized appellate court with nationwide jurisdiction over patent cases. This adds another 12 to 18 months to the litigation timeline, meaning the final resolution of a patent challenge often occurs long after the 30-month stay has expired.

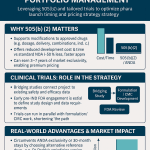

The Parallel Battlefield: Inter Partes Review (IPR)

The landscape of patent litigation was fundamentally altered by the America Invents Act of 2011, which created a new administrative process at the USPTO called Inter Partes Review (IPR).16 An IPR allows a third party (like a generic company) to challenge the validity of an issued patent directly before the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB), a tribunal of technically-savvy administrative patent judges.

This has become an incredibly popular tool for generic challengers, who often file IPR petitions in parallel with the district court litigation. The reasons are clear:

- Lower Burden of Proof: In an IPR, a patent claim is found invalid if it is shown to be unpatentable by a “preponderance of the evidence,” a lower standard than the “clear and convincing evidence” required in district court.

- Technical Expertise: The PTAB judges have scientific or engineering backgrounds, which can be advantageous when arguing complex technical issues of invalidity.

- Speed and Cost: An IPR is designed to be a faster and less expensive proceeding than a full-blown district court case, with a final decision typically rendered within 18 months of filing.

The rise of the IPR has given generic companies a powerful “second bite at the apple.” It creates a dual-front war for the brand company, forcing it to defend its patent in two separate forums simultaneously. The high rate of patent claim cancellation in IPR proceedings has significantly increased the risk for patent holders and, in turn, has increased the pressure on them to settle the district court litigation to avoid a potentially fatal blow from the PTAB. This parallel process has irrevocably shifted the strategic calculus and balance of power in Paragraph IV disputes.

The Financial Stakes: Quantifying Risk and Reward

The legal and procedural complexities of a Paragraph IV challenge are not an academic exercise; they are the mechanics that drive one of the most significant value transfers in the corporate world. For the generic challenger, success means winning a lottery ticket of immense value. For the brand incumbent, the challenge represents an existential threat to its most profitable asset. Understanding the economics of this zero-sum game is critical to appreciating the motivations of each player and the financial shockwaves that follow.

The Generic’s Prize: The Economics of 180-Day Exclusivity

The primary incentive for a generic company to undertake the risk and expense of a Paragraph IV challenge is the “brass ring” offered by the Hatch-Waxman Act: 180 days of market exclusivity.20 This prize is awarded to the

first generic applicant to file a “substantially complete” ANDA containing a Paragraph IV certification.30

During this six-month period, which typically begins on the day the first generic commercially markets its product, the FDA is barred from approving any subsequent ANDAs for the same drug. This effectively creates a temporary duopoly between the brand-name drug and the first generic entrant. This market structure is incredibly lucrative.

The financial dynamics are straightforward. In a duopoly, the first generic can price its product at only a modest discount to the brand’s price—often just 15% to 25% lower—while still rapidly capturing a significant portion of the market share.16 For a blockbuster drug with billions in annual sales, this translates into hundreds of millions of dollars in high-margin revenue. The Supreme Court itself has acknowledged that this exclusivity period can be worth “several hundred million dollars” to a generic manufacturer.

The case of Barr Laboratories’ challenge to Eli Lilly’s blockbuster antidepressant Prozac is a textbook example of this value creation. During its 180-day exclusivity period for generic fluoxetine, Barr captured 65% of the market within the first two months. The influx of revenue was so significant that it nearly doubled the company’s overall gross profit margin, from 16.8% to 28.7%.

However, this golden period is fleeting. Once the 180 days expire, the floodgates open. Multiple other generic manufacturers, whose ANDAs were pending at the FDA, can now launch their products. The market dynamic shifts instantly from a duopoly to a highly competitive, commoditized market. The ensuing price war is brutal and swift. With four or more generic competitors, prices typically plummet by 85% or more from the original brand price. An FDA analysis found that once six generics are on the market, price reductions often exceed 95%.

This “winner-take-most” dynamic makes the race to be the “first-to-file” (FTF) an all-consuming strategic priority for generic companies. It is not enough to simply challenge a patent; the entire R&D, legal, and regulatory apparatus of the company must be geared towards preparing and submitting a perfect, “substantially complete” ANDA on the earliest possible day. This intense competition for FTF status is precisely what the Hatch-Waxman Act was designed to encourage, as it ensures that weak patents on the most commercially valuable drugs face prompt and vigorous challenges.

The Brand’s Peril: The “Patent Cliff” and Defensive Strategies

For the brand-name company, the financial stakes are the mirror image of the generic’s prize: a catastrophic loss of revenue known as the “patent cliff.” This term vividly captures the sudden, steep, and often devastating decline in sales that occurs when a blockbuster drug loses patent protection and faces generic competition.2

The financial impact is staggering. It is not uncommon for a drug that once generated billions in annual sales to see its revenue plummet by 80% to 90% within the first year of generic entry. The case of Pfizer’s Lipitor is iconic. With peak annual sales of approximately $13 billion, Lipitor was the best-selling drug in history. In the year following its loss of exclusivity, worldwide revenues fell by 59%, from $9.5 billion in 2011 to just $3.9 billion in 2012.2 This is not a slow erosion; it is a financial tsunami that can reshape a company’s entire P&L statement in a matter of quarters.

Given this peril, innovator companies have developed a sophisticated playbook of defensive strategies designed to delay, deter, or mitigate the impact of Paragraph IV challenges and the subsequent patent cliff.

Building “Patent Thickets”

Rather than relying on a single patent, brand companies strategically build a dense and overlapping portfolio of intellectual property around a successful drug. This “patent thicket” can include not only the core composition-of-matter patent on the active ingredient but also dozens of secondary patents covering different crystalline forms (polymorphs), formulations, methods of use for different indications, and manufacturing processes.8 The goal is to create a formidable legal barrier that is complex, time-consuming, and expensive for a generic challenger to litigate its way through, patent by patent.

“Product Hopping” and “Evergreening”

This strategy involves making minor modifications to a drug product as its primary patent nears expiration and then launching it as a “new and improved” version. This could be a switch from a twice-daily tablet to a once-daily extended-release formulation, or a combination of two older drugs into a single pill.8 The brand company then heavily markets the new version and attempts to “hop” patients over from the old product before generics can launch. If the new version is protected by its own patents, it can effectively extend the product franchise’s life, a practice critics refer to as “evergreening.”

Launching an “Authorized Generic” (AG)

One of the most powerful and controversial defensive moves is the launch of an authorized generic. This is a generic version of the brand-name drug that is marketed by the brand company itself or by a generic partner under a license.50 Crucially, an AG can be launched during the 180-day exclusivity period of the first-to-file challenger.

This move fundamentally alters the economics of the 180-day prize. Instead of a profitable duopoly, the market becomes a three-way competition between the brand, the FTF generic, and the authorized generic. The presence of the AG dramatically accelerates price erosion and can slash the first-filer’s exclusivity revenues by 40% to 60%.37 The threat of launching an AG has become a powerful bargaining chip for brand companies in settlement negotiations. By offering

not to launch an AG, a brand can provide significant value to the generic challenger, often in exchange for a later, negotiated entry date, without making a direct cash payment that could attract antitrust scrutiny.

These defensive strategies show that brand companies are not passive victims of the patent cliff. They are active participants in a dynamic game, using a combination of legal, regulatory, and commercial tactics to protect their most valuable assets for as long as possible.

Wall Street’s Verdict: How the Market Prices Paragraph IV Risk

The battle between brand and generic is not fought in a vacuum. Every legal filing, every court hearing, and every settlement negotiation is scrutinized in real-time by an army of financial analysts, portfolio managers, and institutional investors. For Wall Street, Paragraph IV litigation is not just a legal process; it is a series of predictable, tradable events that directly impact future cash flows and, therefore, current stock valuations. The market’s reaction provides a clear, and often brutal, verdict on the financial implications of each move in this high-stakes game.

Event-Driven Investing: Trading on Litigation Milestones

The structured nature of the Hatch-Waxman process creates a series of clear inflection points that are ideal for event-driven investment strategies. Sophisticated investors track these milestones closely, adjusting their positions based on their assessment of the likely outcomes. The financial markets are remarkably efficient at pricing the binary risk inherent in patent litigation, and academic “event studies” that analyze stock price movements around these key dates have quantified the enormous stakes involved.

One comprehensive study published in The Journal of Law and Economics used an event-study approach to estimate the average financial stakes in Paragraph IV cases that reached a court decision. The findings were staggering:

- For Brand-Name Firms: The average amount of market capitalization at stake was $4.3 billion.52

- For Generic Firms: The average amount at stake was $204.3 million.52

These figures represent the market’s valuation of a continued monopoly versus the onset of generic competition. The study also found that the market reacts swiftly and predictably to court rulings. On average, when a brand company wins a patent case, its stock value rises by about 2.1%, while the generic challenger’s value falls by about 1.6%.

The market’s reaction to settlement announcements is particularly telling. A separate NBER working paper found that when settlements are announced that contain terms suggestive of a “pay-for-delay” arrangement (such as a brand agreeing not to launch an authorized generic), the brand company’s stock price increases by an average of 3.5%. This positive reaction indicates that investors interpret these deals as being anticompetitive, preserving the brand’s monopoly profits for longer than the market had previously expected. The study estimated that these types of settlements cost U.S. drug purchasers an additional $3.1 to $3.2 billion per year.

This market behavior reveals a crucial truth: the stock price of a pharmaceutical company with a major drug facing a Paragraph IV challenge is, in effect, a probability-weighted average of two distinct future realities. One reality is a continued high-margin monopoly, and the other is a catastrophic patent cliff. Every litigation event—from the initial filing to the final appeal—causes the market to update its probabilities, leading to immediate and sometimes dramatic shifts in the stock price. A massive price swing after a court ruling signifies that the outcome was a surprise to the market, while a muted reaction suggests the outcome was already largely anticipated and “priced in.”

The Analyst’s View: Modeling the Patent Cliff

This process of pricing risk is formalized in the valuation models built by sell-side and buy-side analysts. For any analyst covering the pharmaceutical sector, a company’s “patent exposure” is a primary input into their financial models and a key determinant of their “buy,” “hold,” or “sell” ratings.55

Investment bank research reports from firms like Morgan Stanley, Goldman Sachs, and DBS Bank explicitly detail a company’s patent cliff risk, often including charts that show what percentage of a company’s sales are at risk of losing exclusivity in the coming years.55 A company like Bristol Myers Squibb, with a high exposure of 68% of its sales facing patent expiry, is viewed with caution, while a company like Eli Lilly, with a strong pipeline and lower near-term patent risk, is viewed more favorably.55

Analysts build detailed revenue erosion curves for each major drug, forecasting the steepness of the decline based on factors like the number of generic filers, the potential for an authorized generic launch, and the nature of the market. This modeling directly impacts the firm’s discounted cash flow (DCF) valuation and the price target assigned to its stock.

A deeper and more subtle dynamic influencing these outcomes is the rise of common ownership. The largest institutional investors—firms like BlackRock, Vanguard, and State Street—are often the top shareholders in both a brand-name company and its primary generic competitors.60 This creates a complex set of incentives. While a settlement that delays generic entry might harm the value of the generic firm in their portfolio, it could create a much larger gain in the value of the (typically much larger) brand-name firm. The net effect on the institutional investor’s total portfolio could be positive.

Research has shown that this institutional horizontal shareholding is significantly and positively associated with the likelihood of pay-for-delay settlements.60 This suggests that the financial interests of these powerful, common owners may create a subtle pressure on company management to favor anticompetitive outcomes that maximize overall portfolio value, even at the expense of vigorous market competition. For investors and analysts, understanding this web of shared ownership is becoming increasingly crucial for predicting how patent disputes will ultimately be resolved.

The Art of the Deal: Settlement Dynamics and Antitrust Scrutiny

While the prospect of a winner-take-all courtroom verdict generates headlines, the reality of Paragraph IV litigation is that the vast majority of cases never reach a final judgment. Instead, they are resolved behind closed doors through a negotiated settlement. One study found that only about 31% of disputes end in a trial, with the mean settlement rate being close to 37%. The powerful economic forces pulling both brand and generic companies toward a deal are often too strong to resist.

Why Settle? The Economic Rationale

The decision to settle is rooted in a simple desire to mitigate risk and achieve certainty. For both sides, litigation is a high-stakes gamble with potentially catastrophic downsides.

- For the Brand Company: A loss in court means the immediate and irreversible onset of the patent cliff, wiping out billions in future revenue.

- For the Generic Company: A loss means years of investment in R&D and millions of dollars in legal fees are completely wasted, with no return.

Litigation is also incredibly expensive. A complex Paragraph IV case can easily cost each party $5 million to $10 million or more in legal fees.30 A settlement allows both parties to avoid these costs and, more importantly, to eliminate their worst-case scenario.

At its core, a settlement is a sophisticated risk-sharing agreement. The brand company holds a highly valuable but risky asset: its patent-protected monopoly revenue stream. The generic challenger holds what is effectively a “call option” on that revenue stream—the right to enter the market and capture a share of it if its patent challenge is successful. A settlement allows the brand to essentially “buy back” that option from the generic. In exchange for the generic dropping its lawsuit, the brand agrees to grant it a license to enter the market on a specified future date. This guarantees the generic a return on its investment while allowing the brand to preserve its monopoly for a defined period, providing certainty for both parties and their shareholders. The negotiation, then, is simply about the price of this risk transfer, with the primary currency being the length of the delay in the generic’s entry date.

“Pay-for-Delay” and the FTC v. Actavis Revolution

The most controversial form of settlement is the “reverse payment” or “pay-for-delay” agreement. In its classic form, this involves the brand-name company (the patent holder and plaintiff) paying the generic company (the alleged infringer and defendant) to settle the case and agree to delay its market entry.63 This is “reverse” because in typical patent litigation, any payment flows from the infringer to the patent holder.

For years, these agreements were largely shielded from antitrust scrutiny under the logic that any delay within the 20-year scope of the patent was a legitimate exercise of the patent holder’s right to exclude. However, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and other critics argued that these deals were often nakedly anticompetitive agreements to split monopoly profits, harming consumers by keeping lower-cost generics off the market.65

This debate culminated in the landmark 2013 Supreme Court decision, FTC v. Actavis, Inc..64 The Court rejected the idea that these settlements were immune from antitrust law. It ruled that a large and “unexplained” payment from a brand to a generic could be a strong indicator of an unreasonable restraint on trade. The Court established that such agreements must be evaluated under the antitrust

“rule of reason,” a fact-intensive analysis that weighs the pro-competitive justifications of an agreement against its potential anticompetitive harms.64

The Actavis decision fundamentally changed the legal landscape and the art of the settlement deal. It did not ban settlements, but it made large, direct cash payments from brand to generic extremely risky from an antitrust perspective. The industry, however, is adept at adapting to legal constraints. The ruling simply made settlement negotiations more creative.

Instead of direct cash, value is now often transferred in more subtle ways that are harder for regulators to challenge as a direct “payment for delay.” These can include:

- “No-AG” Commitments: A promise by the brand not to launch an authorized generic during the first-filer’s 180-day exclusivity period. This is a clear transfer of value, as it preserves the full profitability of the exclusivity period for the generic, but it is not a cash payment.

- Side Deals: Agreements related to other products, such as co-promotion deals or licenses on different drugs, where the terms may be structured to be overly favorable to the generic company.

- Volume-Limited Licenses: Agreements that allow a generic to enter the market before patent expiration but limit the quantity of product it can sell, thus preserving a significant share of the market for the brand.

The legacy of Actavis is a more complex and nuanced world of settlement negotiations. It requires regulators, investors, and competitors to look beyond the headline entry date and scrutinize the full commercial context of any deal to understand whether it is a legitimate resolution of a patent dispute or an illegal agreement to divide a market.

High-Profile Case Studies: Lessons from the Trenches

The theories, regulations, and financial models surrounding Paragraph IV challenges come to life in the real-world battles fought over blockbuster drugs. These high-profile cases are more than just legal history; they are rich case studies in strategy, risk management, and financial impact, offering invaluable lessons for any executive or investor navigating this landscape.

Case Study 1: Pfizer’s Lipitor – The Birth of the Modern Patent Cliff Defense

When the patent on Pfizer’s Lipitor (atorvastatin) was set to expire in 2011, the entire industry was watching. As the best-selling drug in history, with peak annual sales approaching $13 billion, Lipitor’s fall from exclusivity was destined to be a watershed moment.2 What transpired was not a passive tumble off the cliff, but a masterclass in aggressive, multi-pronged defense that wrote the playbook for modern lifecycle management.

- The Strategy: Pfizer refused to cede the market. In the run-up to the patent expiration, it continued to invest heavily in marketing to maintain brand loyalty. But its most innovative moves came at the moment of generic entry.

- The Authorized Generic Gambit: Pfizer partnered with Watson Pharmaceuticals to launch an authorized generic version of Lipitor on the very same day the first independent generic from Ranbaxy hit the market. This immediately diluted the value of Ranbaxy’s 180-day exclusivity, allowing Pfizer to retain a significant share (an estimated 70%) of the profits from the “generic” market it was now competing in.47

- The Price War: In an unprecedented move, Pfizer went to war on price against the generics with its own branded product. Through its “Lipitor-For-You” program, Pfizer offered privately insured patients a coupon card that lowered their co-payment for branded Lipitor to just $4 a month—often less than the co-pay for the new generic.69 It also offered deep rebates to pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) and insurance plans to keep Lipitor in a preferential position on formularies.

- The Financial Impact: The patent cliff was still severe. Pfizer’s global Lipitor revenues plummeted by 42% in the first quarter of 2012 compared to the prior year. However, the defensive strategy was a resounding success in mitigating the damage. At the end of the 180-day generic exclusivity period, Pfizer had retained an astonishing 30% of the U.S. atorvastatin market, far exceeding analyst expectations. They had successfully transformed a steep cliff into a more manageable slope, preserving billions of dollars in revenue.

- The Lesson: The Lipitor case proved that patent expiration does not have to be a passive event. Proactive, creative, and aggressive commercial strategies can significantly alter the trajectory of revenue decline, demonstrating that brand equity and market access can be powerful weapons even in the face of generic competition.

Case Study 2: Teva’s Copaxone – When Patent Strategy Crosses the Line

Teva Pharmaceutical’s defense of its blockbuster multiple sclerosis drug, Copaxone (glatiramer acetate), serves as a cautionary tale about the fine line between legitimate lifecycle management and anticompetitive abuse of the patent system.

- The Strategy: Faced with the expiration of its core patents, Teva embarked on a multi-year campaign to obstruct generic competition that regulators ultimately deemed illegal.

- The “Divisionals Game”: Teva was found to have misused the European patent system by strategically filing and withdrawing waves of “divisional” patents—secondary patents derived from an earlier application. This created a constantly shifting web of intellectual property that forced generic competitors to repeatedly engage in new, lengthy, and costly legal challenges to clear a path to market.71

- The Disparagement Campaign: Teva also engaged in a systematic campaign to spread misleading information about a competing generic product, targeting doctors and health authorities with messaging designed to create doubts about its safety and efficacy, despite the product having been approved by those same authorities.71

- The Financial Impact: The regulatory backlash was severe. In October 2024, the European Commission imposed a fine of €462.6 million (approximately $503 million) on Teva for abusing its dominant market position.71 This was one of the largest fines ever levied in the pharmaceutical sector, sending a clear message that regulators are willing to impose massive penalties for conduct that crosses the line from aggressive defense to illegal market exclusion.

- The Lesson: The Teva case highlights the significant legal and financial risks associated with overly aggressive “evergreening” strategies. While building a robust patent portfolio is a standard and legitimate business practice, using the patent system itself as a tool for procedural obstruction can attract severe antitrust scrutiny. This adds another critical layer of risk for companies and their investors to assess when evaluating a firm’s lifecycle management strategy.

Case Study 3: Gilead’s Truvada – A Battle Over Public-Private Innovation

The patent challenge against Gilead’s HIV drug Truvada (emtricitabine/tenofovir) was unique. The challenger was not a rival generic company, but the United States Government itself.

- The Strategy: The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) sued Gilead in 2019, alleging that government scientists at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) were the true inventors of using Truvada for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). HHS claimed that Gilead was infringing on government-held patents and owed the public substantial royalties.

- The Financial Impact: Gilead fought back, arguing that the government’s patents were invalid and that the government had breached its own research collaboration contracts with the company by filing for them. The legal battle was long and costly for both sides. The turning point came in May 2023, when a federal jury delivered a unanimous verdict, finding the government’s patents to be invalid. The five-year litigation finally concluded with a settlement in 2025, with Gilead avoiding what could have been a massive liability in back-royalties and damages.

- The Lesson: The Truvada case introduces a novel and unpredictable type of patent challenger: the government. It highlights the complex and often contentious interface between publicly funded research and private-sector commercialization. For companies that collaborate with government agencies like the NIH or CDC, this case underscores the critical importance of clearly defining intellectual property rights and inventorship in research agreements. It creates a unique form of legal and financial risk that must be carefully managed, as the very partner in innovation could one day become the adversary in litigation.

These cases, summarized in the table below, illustrate the diverse strategies and profound financial outcomes that define the Paragraph IV landscape.

| Drug (Brand Name) | Innovator Company | Peak Annual Sales (Approx.) | Year of First PIV Challenge | Outcome & Quantifiable Financial Impact |

| Lipitor (atorvastatin) | Pfizer | ~$13 Billion | ~2005 | Managed decline via AG & rebates; sales fell by >$5B in first year post-LOE. |

| Plavix (clopidogrel) | BMS / Sanofi | ~$9 Billion | ~2002 | Lost patent battle; faced rapid generic erosion, massive revenue cliff. |

| Copaxone (glatiramer acetate) | Teva | ~$4 Billion | ~2008 | Accused of anticompetitive tactics; fined €462.6M by EU Commission. |

| Revlimid (lenalidomide) | Celgene (BMS) | ~$12 Billion | ~2010 | Strategic settlements allowing for volume-limited generic entry, creating a managed “slope” instead of a “cliff”. |

| Truvada (for PrEP) | Gilead | ~$3 Billion | 2019 (by US Gov’t) | Won invalidity verdict against US Gov’t patents, avoiding royalties/damages. |

Conclusion: A Strategic Framework for Navigating the PIV Landscape

The journey from a Paragraph IV filing in a legal brief to its ultimate impact on a company’s stock price is a complex, multi-stage process governed by a unique interplay of law, science, and finance. As we have seen, this is no mere procedural hurdle. It is a core driver of value and risk in the pharmaceutical industry. The ability to anticipate, analyze, and strategically respond to these challenges is no longer a niche legal concern but a fundamental competency for any executive, strategist, or investor in this sector. The key learnings from our deep dive can be synthesized into an actionable framework for each of the key players in this high-stakes game.

Strategic Takeaways for Brand Companies

For innovator firms, the defense of a blockbuster drug is a battle for the company’s financial lifeblood. A passive or reactive approach is a recipe for disaster.

- Build a Fortress, Not a Wall: Proactive patent portfolio management is the foundation of any successful defense. A single patent, no matter how strong, is a single point of failure. A robust “patent thicket”—a layered, overlapping portfolio of patents covering the compound, formulations, methods of use, and manufacturing processes—is essential. This strategy is not about improperly extending a monopoly but about ensuring that true innovation at every stage of a product’s life is protected, creating a more defensible and resilient asset.

- Weaponize the 30-Month Stay: The automatic 30-month stay is the most valuable immediate asset in the defensive arsenal. The decision to file suit within 45 days should be seen as an automatic financial decision to secure a guaranteed period of revenue protection. This time should not be wasted. It must be used to aggressively litigate, but also to prepare for the inevitable.

- Plan for the Post-Exclusivity World: A comprehensive lifecycle management plan must be in place years before the first Paragraph IV letter arrives. This includes developing next-generation products to switch patients to, preparing for the potential launch of an authorized generic, and crafting the commercial strategies—from pricing to payer negotiations—that will mitigate the patent cliff and manage the transition to a competitive market.

Strategic Takeaways for Generic Companies

For generic manufacturers, Paragraph IV challenges are the primary engine of growth and value creation. Success requires a combination of scientific acumen, regulatory precision, and legal audacity.

- The Race to “First-to-File” is Everything: The winner-take-most economics of the 180-day exclusivity period means that speed and accuracy are paramount. The entire organization must be aligned to identify opportunities early and submit a “substantially complete” ANDA on the first possible day. This is a game of inches where a single day can be the difference between a blockbuster success and a marginal product.

- Due Diligence is Your Weapon: A successful challenge begins with deep intelligence. Thoroughly analyzing a brand’s patent portfolio using resources like the Orange Book and specialized databases is essential to identify the weakest links—the patents with questionable validity or those that can be easily designed around.

- Litigate to Settle: While the goal is to win in court, the practical reality is that litigation is often a means to a more favorable end: a negotiated settlement. Understanding the brand’s financial incentives, its tolerance for risk, and the strategic value of assets like a “no-AG” commitment is key to maximizing the value of your challenger position at the negotiating table.

Strategic Takeaways for Investors

For the investment community, Paragraph IV litigation represents a series of predictable, material events that create both risk and opportunity.

- Monitor the Filing as a Material Event: A Paragraph IV filing against a key product is a red flag that requires immediate attention. Investors must monitor these events closely using public resources like the FDA’s Paragraph IV Certification List and specialized competitive intelligence platforms that provide deeper context and analysis.

- Scrutinize the Patent Cliff and the Pipeline: A company’s exposure to patent expirations is one of the most significant risks to its long-term valuation. A core part of any investment thesis must be a rigorous assessment of a company’s patent cliff and the strength and probability of success of its R&D pipeline to replace those lost revenues.

- Look Beyond the Headlines: The story is often more complex than a simple “win” or “loss.” Investors need to analyze the specific terms of settlement agreements to understand the true economic impact. Furthermore, understanding the web of common ownership among brand and generic firms can provide a deeper insight into why certain seemingly irrational or anticompetitive deals are made.

The fundamental game of strategic legal and financial maneuvering established by the Hatch-Waxman Act is not going away. While new frontiers are opening, such as the application of similar principles to the biologics and biosimilars space under the BPCIA, the core dynamics will persist. The companies and investors who master this complex interplay—who can read the legal tea leaves to predict financial outcomes—will be the ones who thrive in the ever-evolving pharmaceutical landscape.

Key Takeaways

- Hatch-Waxman Act as the Foundation: The 1984 Hatch-Waxman Act created the modern generic drug industry by establishing the ANDA pathway and incentivizing patent challenges, fundamentally shaping all strategic decisions in the small-molecule drug market.

- Paragraph IV Filing is a Financial Catalyst: A Paragraph IV certification is not just a legal filing; it is an “artificial act of infringement” that triggers a predictable legal and financial process, transforming a patent’s theoretical value into a quantifiable market risk.

- The 30-Month Stay is a Multi-Billion Dollar Shield: For brand companies, triggering the 30-month stay by filing suit within 45 days of a notice letter is a critical financial strategy that guarantees a period of continued monopoly revenue worth billions.

- 180-Day Exclusivity is the Ultimate Prize: For generic challengers, securing “first-to-file” status and the subsequent 180 days of market exclusivity is immensely valuable, often accounting for the majority of a generic drug’s lifetime profitability.

- The “Patent Cliff” is Real and Severe: The loss of patent exclusivity typically leads to an 80-90% decline in a brand drug’s revenue within the first year, making defensive strategies like building “patent thickets” and launching “authorized generics” essential.

- Wall Street Prices Litigation in Real-Time: Financial markets treat Paragraph IV litigation as a series of tradable events. Stock prices react immediately to key milestones, with event studies showing that billions of dollars in market capitalization are at stake in these legal battles.

- Settlement is the Norm, Not the Exception: The high cost and binary risk of litigation drive most parties to settle. The FTC v. Actavis decision has made these settlements more complex, shifting value transfer from direct cash payments to more subtle commercial agreements.

- Strategy is Paramount: Success for all parties—brand, generic, and investor—hinges on a deep, strategic understanding of this complex ecosystem, from proactive patent portfolio management to precise regulatory filings and sophisticated financial analysis.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. Why would a generic company file a Paragraph IV challenge if it almost guarantees an expensive lawsuit and a 30-month delay in approval?

A generic company files a Paragraph IV challenge for one primary reason: the potential for a massive financial reward. While it does trigger a costly lawsuit and a 30-month stay, it is the only pathway to enter the market before the brand’s patents expire. The prize for being the first successful challenger is the 180-day exclusivity period, which can generate hundreds of millions of dollars in high-margin revenue. This potential windfall is often more than enough to justify the litigation risk and expense, especially for blockbuster drugs. The 30-month stay, while a delay, is a known quantity that allows the generic to litigate without the catastrophic risk of launching and then having to pay damages if they lose the case.

2. What is a “patent thicket” and how does it actually work to deter generic competition?

A “patent thicket” is a dense, overlapping web of patents that a brand company builds around a single drug. Instead of just one patent on the active molecule, the company will file numerous additional patents on different aspects like specific formulations (e.g., an extended-release tablet), methods of use (treating a specific disease), crystalline structures (polymorphs), and manufacturing processes. This works as a deterrent in two ways. First, it dramatically increases the cost and complexity for a generic challenger, who must now analyze and potentially litigate dozens of patents instead of just one or two. Second, it increases the brand’s chances of winning on at least one patent, as the generic must successfully defeat every asserted patent to gain market entry. It turns the legal challenge from a single battle into a long, multi-front war of attrition.

3. If a district court rules that a brand’s patent is invalid, can the generic company launch immediately, even if the brand company appeals?

Yes, they can, but it’s known as an “at-risk launch.” A district court decision in favor of the generic challenger terminates the 30-month stay, allowing the FDA to grant final approval. The generic can then choose to launch its product commercially. However, the “at-risk” designation comes from the fact that the brand company will almost certainly appeal the decision to the Federal Circuit. If the appellate court reverses the lower court’s decision and finds the patent is valid and infringed, the generic company could be liable for massive damages, potentially including the brand’s lost profits, for all the sales it made during the appeal period. This makes the decision to launch at-risk a high-stakes business calculation based on the generic’s confidence in the strength of the district court’s ruling.

4. How has the Supreme Court’s FTC v. Actavis decision on “pay-for-delay” settlements actually changed company behavior?

The Actavis decision made it much riskier for a brand company to make a large, direct cash payment to a generic company in exchange for delaying market entry. This practice is now a major red flag for antitrust regulators. However, it did not stop settlements. Instead, it forced companies to become more creative in how value is transferred. Behavior has shifted from explicit cash payments to more subtle, but still valuable, considerations. The most common is a “no-AG” agreement, where the brand promises not to launch its own authorized generic during the challenger’s 180-day exclusivity period. This preserves the full profit potential of the exclusivity for the generic and is a clear transfer of value, but it’s less likely to be challenged as a direct “payment.” The decision has made the “art of the deal” more complex and has pushed potentially anticompetitive terms into less transparent side agreements.

5. As an investor, what is the single most important metric to watch when assessing a pharmaceutical company’s risk from Paragraph IV challenges?

While there are many important metrics, the single most critical one is revenue concentration. An investor must ask: “What percentage of this company’s total revenue and, more importantly, its total profit, comes from a single drug that is approaching the end of its patent life?” A company that derives 40% or 50% of its profits from one product is in a far more precarious position than a diversified company where no single product accounts for more than 10%. High revenue concentration creates a “bet-the-company” scenario around a single patent litigation outcome. This should be followed by a close examination of the company’s R&D pipeline to assess its ability to generate new revenue streams to offset the inevitable decline of its aging blockbuster.

References

- Paragraph IV Filings & ANDA Explained – Minesoft, accessed August 8, 2025, https://minesoft.com/paragraph-iv-filings-generic-drugs-big-pharma/

- The End of Exclusivity: Navigating the Drug Patent Cliff for …, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-impact-of-drug-patent-expiration-financial-implications-lifecycle-strategies-and-market-transformations/

- Make Better Decisions | PDF – Scribd, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.scribd.com/document/489304689/Make-Better-Decisions

- Make Better Decisions – Share | PDF | Generic Drug | Phases Of Clinical Research – Scribd, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.scribd.com/document/563750797/make-better-decisions-share

- 40th Anniversary of the Generic Drug Approval Pathway – FDA, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/cder-conversations/40th-anniversary-generic-drug-approval-pathway

- What is Hatch-Waxman? – PhRMA, accessed August 8, 2025, https://phrma.org/resources/what-is-hatch-waxman

- THE HATCH-WAXMAN ACT: HISTORY, STRUCTURE, AND LEGACY – HeinOnline, accessed August 8, 2025, https://heinonline.org/hol-cgi-bin/get_pdf.cgi?handle=hein.journals/antil71§ion=23

- How Drug Life-Cycle Management Patent Strategies May Impact Formulary Management, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.ajmc.com/view/a636-article

- The 30th Anniversary of the Hatch-Watchman Act: Foreword – Mitchell Hamline Open Access, accessed August 8, 2025, https://open.mitchellhamline.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1584&context=wmlr

- The Hatch-Waxman Act (Simply Explained) – Biotech Patent Law, accessed August 8, 2025, https://berksiplaw.com/2019/06/the-hatch-waxman-act-simply-explained/

- STRATEGIES FOR FILING SUCCESSFUL PARAGRAPH IV CERTIFICATIONS – St. Onge Steward Johnston & Reens LLC, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.ssjr.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/presentations/lawyer_1/92706VA.pdf

- The balance between innovation and competition: the Hatch-Waxman Act, the 2003 Amendments, and beyond – PubMed, accessed August 8, 2025, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24505856/

- Hatch-Waxman 101 – Fish & Richardson, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.fr.com/insights/thought-leadership/blogs/hatch-waxman-101-3/

- Hatch-Waxman Act – Practical Law, accessed August 8, 2025, https://uk.practicallaw.thomsonreuters.com/Glossary/PracticalLaw/I2e45aeaf642211e38578f7ccc38dcbee

- Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act – Wikipedia, accessed August 8, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Drug_Price_Competition_and_Patent_Term_Restoration_Act

- Paragraph IV Explained – ParagraphFour.com, accessed August 8, 2025, https://paragraphfour.com/paragraph-iv-explained/

- What is ANDA? – UPM Pharmaceuticals, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.upm-inc.com/what-is-anda

- The ANDA Process: A Guide to FDA Submission & Approval – Excedr, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.excedr.com/blog/what-is-abbreviated-new-drug-application

- 40 Years of Hatch-Waxman: How does the Hatch-Waxman Act help patients? | PhRMA, accessed August 8, 2025, https://phrma.org/blog/40-years-of-hatch-waxman-how-does-the-hatch-waxman-act-help-patients

- The 180-Day Rule Supports Generic Competition. Here’s How., accessed August 8, 2025, https://accessiblemeds.org/resources/blog/180-day-rule-supports-generic-competition-heres-how/

- Patent Listing in FDA’s Orange Book – Congress.gov, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/IF12644

- Freshly Squeezed: Orange Book History and Key Updates at 45, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.fdli.org/2025/05/freshly-squeezed-orange-book-history-and-key-updates-at-45/

- Orange Book 101 | The FDA’s Official Register of Drugs, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.fr.com/insights/ip-law-essentials/orange-book-101/

- Orange Book Data Files – FDA, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-approvals-and-databases/orange-book-data-files

- Mastering Paragraph IV Certification – Number Analytics, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.numberanalytics.com/blog/mastering-paragraph-iv-certification

- Life-Cycle Management: Legal Issues and Strategies – Drug Information Association, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.diaglobal.org/productfiles/25849/20110518/track2/10%20t2-4_chen%20shaoyu.ppt

- Intricacies of the 30-Month Stay in Pharmaceutical Patent Cases | Articles – Finnegan, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.finnegan.com/en/insights/articles/intricacies-of-the-30-month-stay-in-pharmaceutical-patent-cases.html

- Sharpen Your Sword for Litigation: Incumbent Strategic Reaction to the Threat of Entry | Management Science – PubsOnLine, accessed August 8, 2025, https://pubsonline.informs.org/doi/10.1287/mnsc.2023.00900

- Tips For Drafting Paragraph IV Notice Letters | Crowell & Moring LLP, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.crowell.com/a/web/v44TR8jyG1KCHtJ5Xyv4CK/tips-for-drafting-paragraph-iv-notice-letters.pdf

- What Every Pharma Executive Needs to Know About Paragraph IV Challenges, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/what-every-pharma-executive-needs-to-know-about-paragraph-iv-challenges/

- Hatch Waxman Litigation 101 | DLA Piper, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.dlapiper.com/insights/publications/2020/06/ipt-news-q2-2020/hatch-waxman-litigation-101

- FDA ANDAs containing paragraph IV patent certifications, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.gabionline.net/policies-legislation/FDA-ANDAs-containing-paragraph-IV-patent-certifications

- Leveling the Playing Field—The Role of Venture Capital in Hatch–Waxman Act Patent Litigation, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.bartonesq.com/pdf/PDFArtic.pdf

- The timing of 30‐month stay expirations and generic entry: A cohort study of first generics, 2013–2020, accessed August 8, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8504843/

- Patent Certifications and Suitability Petitions – FDA, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/abbreviated-new-drug-application-anda/patent-certifications-and-suitability-petitions

- The Hatch-Waxman 180-Day Exclusivity Incentive Accelerates Patient Access to First Generics, accessed August 8, 2025, https://accessiblemeds.org/resources/fact-sheets/the-hatch-waxman-180-day-exclusivity-incentive-accelerates-patient-access-to-first-generics/

- Should We Settle? Considerations For Generic Companies Before Settling Hatch-Waxman Litigation – Cantor Colburn, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.cantorcolburn.com/media/news/40_201110_Sept%202011%20Shoudl%20We%20Settle%20-%20Hatch-Waxman%20Litigation.pdf

- Hatch-Waxman: How to Prepare for the Paragraph IV Letter – Fish & Richardson, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.fr.com/uploads/793-hatch-waxman-paragraph-iv_final-copy.pdf

- 5 Ways to Predict Patent Litigation Outcomes – DrugPatentWatch …, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/5-ways-to-predict-patent-litigation-outcomes/

- IPRs and ANDA Litigation – Federal Bar Association, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.fedbar.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/feature4-janfeb15-pdf-1.pdf

- Most-Favored Entry Clauses in Drug-Patent Litigation Settlements: A Reply to Drake and McGuire (2022) – American Bar Association, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/publications/antitrust/magazine/2023/december/most-favored-entry-clauses.pdf

- Small Business Assistance | 180-Day Generic Drug Exclusivity – FDA, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/cder-small-business-industry-assistance-sbia/small-business-assistance-180-day-generic-drug-exclusivity

- Earning Exclusivity: Generic Drug Incentives and the Hatch-‐Waxman Act1 C. Scott – Stanford Law School, accessed August 8, 2025, https://law.stanford.edu/index.php?webauth-document=publication/259458/doc/slspublic/ssrn-id1736822.pdf

- Authorized Generics In The US: Prevalence, Characteristics, And Timing, 2010–19, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/10.1377/hlthaff.2022.01677

- The Economics of Generic Drug Pricing Strategies: A Comprehensive Analysis – DrugPatentWatch – Transform Data into Market Domination, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-economics-of-generic-drug-pricing-strategies-a-comprehensive-analysis/

- The Costs of Pharma Cheating – I-MAK, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.i-mak.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/AELP_052023_PharmaCheats_Report_FINAL.pdf

- Pfizer’s 180-Day War for Lipitor | PM360, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.pm360online.com/pfizers-180-day-war-for-lipitor/

- Optimizing Your Drug Patent Strategy: A Comprehensive Guide for Pharmaceutical Companies – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/optimizing-your-drug-patent-strategy-a-comprehensive-guide-for-pharmaceutical-companies/

- The History and Political Economy of the Hatch-Waxman Amendments – eRepository @ Seton Hall, accessed August 8, 2025, https://scholarship.shu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1677&context=shlr

- Generic Drug Challenges Prior to Patent Expiration C. Scott Hemphill* and Bhaven N. Sampat – NYU Law, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.law.nyu.edu/sites/default/files/ECM_PRO_064165.pdf

- Strategies that delay or prevent the timely availability of affordable generic drugs in the United States, accessed August 8, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4915805/

- The Distribution of Surplus in the US Pharmaceutical Industry …, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/abs/10.1086/707407

- The Distribution of Surplus in the US Pharmaceutical Industry: Evidence from Paragraph iv Patent-Litigation Decisions, accessed August 8, 2025, https://jonwms.web.unc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/10989/2021/06/ParIVSettlements_JLE.pdf

- NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES USING STOCK PRICE …, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w33196/w33196.pdf

- Global Pharmaceutical Sector – DBS, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.dbs.com/content/article/pdf/AIO/052024/240524_insights_global_pharmaceutical_sector_surviving_the_patent_cliff_challenge.pdf

- JP Morgan Initiating Coverage On Indegene With TP 570 Niche | PDF – Scribd, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.scribd.com/document/767803356/JP-Morgan-Initiating-Coverage-on-Indegene-with-TP-570-Niche

- Morgan Stanley Remains Bullish on Eli Lilly (LLY) – FINVIZ.com, accessed August 8, 2025, https://finviz.com/news/116758/morgan-stanley-remains-bullish-on-eli-lilly-lly

- Global Pharma: Surviving the patent cliff challenge – DBS, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.dbs.com/in/treasures/aics/templatedata/article/generic/data/en/GR/052024/240524_insights_global_pharmaceutical_sector_surviving_the_patent_cliff_challenge.xml

- Global Health Care Conference: Strategy Sector Views + Analyst Stock Picks – Morgan Stanley, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.morganstanley.com/content/dam/msdotcom/ideas/USEQUITY_20200914_0000.pdf

- The Anticompetitive Effects of Common Ownership: The Case of Paragraph IV Generic Entry, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/pandp.20201029

- Institutional Horizontal Shareholdings and Generic Entry in the Pharmaceutical Industry – American Economic Association, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.aeaweb.org/conference/2020/preliminary/paper/BzH9QTnD

- Fake Entry, accessed August 8, 2025, http://ewfs.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/ssrn-4848427.pdf

- Reverse Payment Settlements: The U.S. Supreme Court Has Finally Agreed to Resolve the Issue, 12 J. Marshall Rev. Intell. Prop. L – UIC Law Open Access Repository, accessed August 8, 2025, https://repository.law.uic.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1315&context=ripl

- Settlement Should Be the End of Story: A Proposed Procedure to Settle Hatch-Waxman Paragraph IV Litigations Modeled After Rule 2 – eRepository @ Seton Hall, accessed August 8, 2025, https://scholarship.shu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1562&context=shlr

- Are Settlements in Patent Litigation Collusive? Evidence from Paragraph IV Challenges – National Bureau of Economic Research, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w22194/w22194.pdf

- ‘Pay to Delay’ Settlements in Patent Litigation | NBER, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.nber.org/digest/jul16/pay-delay-settlements-patent-litigation

- U.S. Supreme Court Adopts “Rule of Reason” Test for Reverse Payment Settlements, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.hahnlaw.com/insights/us-supreme-court-adopts-rule-of-reason-test-for-reverse-payment-settlements/

- The Simple Math of Royalties and Drug Competition During the 180-Day Generic Exclusivity Period | NBER, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.nber.org/papers/w31018

- Managing the challenges of pharmaceutical patent expiry: a case study of Lipitor, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.emerald.com/jstpm/article-split/7/3/258/249506/Managing-the-challenges-of-pharmaceutical-patent

- Pfizer’s Lipitor: A New Model for Delaying the Effects of Patent Expiration, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.patentdocs.org/2011/12/pfizers-lipitor-a-new-model-for-delaying-the-effects-of-patent-expiration.html

- Commission fines Teva €462.6 million over misuse of the patent system and disparagement to delay rival multiple sclerosis medicine, accessed August 8, 2025, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_24_5581

- European Commission Fines Teva €462.6 Million for Misusing Divisional patents and Disparaging Generic Competitors in the Copaxone Market – McDermott Will & Emery, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.mwe.com/insights/european-commission-fines-teva-e462-6-million-for-misusing-divisional-patents-and-disparaging-generic-competitors-in-the-copaxone-market/

- EU Commission fines Teva €462.6 million for misuse of divisional patents and disparagement campaign | Herbert Smith Freehills Kramer | Global law firm, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.hsfkramer.com/notes/crt/2024-posts/EU-Commission-fines-Teva-4626-million-for-misuse-of-divisional-patents-and-disparagement-campaign

- Stiff EU Antitrust Fine for ‘Misuse’ of Patent System Delaying Rival Pharma Entry // Cooley // Global Law Firm, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.cooley.com/news/insight/2024/2024-11-19-stiff-eu-antitrust-fine-for-misuse-of-patent-system-delaying-rival-pharma-entry

- Gilead Statement on Successful Resolution with U.S. Department of Justice and the Department of Health and Human Services on Patents, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.gilead.com/company/company-statements/2025/gilead-statement-on-successful-resolution-with-us-department-of-justice-and-the-department-of-health-and-human-services-on-patents

- www.fda.gov, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/abbreviated-new-drug-application-anda/hatch-waxman-letters#:~:text=The%20%22Drug%20Price%20Competition%20and,Drug%2C%20and%20Cosmetic%20Act%20(FD%26C

- 21 CFR 314.94 — Content and format of an ANDA. – eCFR, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-21/chapter-I/subchapter-D/part-314/subpart-C/section-314.94

- Paragraph IV Patent Certifications July 7, 2025 – FDA, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/media/166048/download

- Orange Book Patent Listing and Patent Certifications: Key Provisions in FDA’s Proposed Regulations Implementing the Medicare Modernization Act of 2003 | Insights | Ropes & Gray LLP, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.ropesgray.com/en/insights/alerts/2015/02/orange-book-patent-listing-and-patent-certifications-key-provisions-in-fdas-proposed-regulations

- Legislative History of the Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984 – PL 98-417 – IP Mall – University of New Hampshire, accessed August 8, 2025, https://ipmall.law.unh.edu/content/legislative-history-drug-price-competition-and-patent-term-restoration-act-1984-pl-98-417

- Patent Term Extensions and the Last Man Standing | Yale Law & Policy Review, accessed August 8, 2025, https://yalelawandpolicy.org/patent-term-extensions-and-last-man-standing

- An International Guide to Patent Case Management for Judges – WIPO, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.wipo.int/patent-judicial-guide/en/full-guide/united-states/10.13.2

- Hatch-Waxman 201 – Fish & Richardson, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.fr.com/insights/thought-leadership/blogs/hatch-waxman-201-3/

- Regulation and welfare: evidence from paragraph IV generic entry in the pharmaceutical industry – IDEAS/RePEc, accessed August 8, 2025, https://ideas.repec.org/a/bla/randje/v47y2016i4p857-890.html

- PHARMACEUTICAL PATENT CHALLENGES AND THEIR IMPLICAITONS FOR INNOVATION AND GENERIC COMPETION HENRY GRABOWSKI A CARLOS BRAIN B AN, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.aeaweb.org/conference/2015/retrieve.php?pdfid=3499&tk=r6QR3A3H

- Full article: Continuing trends in U.S. brand-name and generic drug competition, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13696998.2021.1952795

- Continuing trends in U.S. brand-name and generic drug competition – Taylor & Francis Online, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/13696998.2021.1952795

- Pharmaceutical Patent Challenges: Company Strategies and Litigation Outcomes, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.1162/AJHE_a_00066

- Estimating the Effect of Entry on Generic Drug Prices Using Hatch-Waxman Exclusivity – Federal Trade Commission, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.ftc.gov/sites/default/files/documents/reports/estimating-effect-entry-generic-drug-prices-using-hatch-waxman-exclusivity/wp317.pdf