I. Introduction: The Billion-Dollar Labyrinth

The High-Stakes World of Biologic Patents

A patent is far more than a legal instrument; it is the central financial asset, the cornerstone upon which multi-billion-dollar enterprises are built and defended. This is particularly true in the realm of biologic drugs, where the intersection of profound scientific complexity, immense financial risk, and intricate legal frameworks has created a veritable labyrinth. Navigating this maze is the defining strategic challenge for innovators, biosimilar developers, investors, and policymakers alike. The core tension is a delicate balance: the imperative to incentivize the astronomical investment required for breakthrough innovation against the profound societal need for affordable access to life-altering medicines.1

The economics of this landscape are staggering. Bringing a single new biologic drug to market is a gamble of epic proportions, with the average capitalized cost estimated at $2.6 billion.2 This figure accounts not only for the direct costs of research and clinical trials but also for the immense cost of failure—for every successful biologic, thousands of candidates fall by the wayside—and the opportunity cost of capital tied up for over a decade.3 To justify such risk, innovator companies rely on a period of market exclusivity, protected by intellectual property rights, to recoup their investment and fund the next wave of discovery.5

Why Biologics Changed the IP Game

The arrival of biologics—large, complex molecules derived from living systems—fundamentally reshaped the intellectual property game. Unlike traditional, chemically synthesized small-molecule drugs, biologics introduced a new level of scientific nuance that existing patent law was not fully equipped to handle.6 Their inherent complexity and the nature of their manufacturing created novel challenges and opportunities for patenting, leading to the development of sophisticated, multi-layered IP strategies that are far more intricate than those for their small-molecule counterparts.8

This IP maze has become more critical than ever as biologics have moved from the periphery to the center of the pharmaceutical universe. Today, biologics account for a remarkable 46% of all medicine spending in the United States and represent the fastest-growing segment of the market.6 As blockbuster biologics for cancer, autoimmune diseases, and other chronic conditions generate tens of billions of dollars in annual revenue, the patents protecting them have become the focus of intense legal and commercial battles.

The term “patent maze” is not merely a metaphor. It is the direct and logical outcome of the biopharmaceutical industry’s economic model. The astronomical development costs and high failure rates are the fundamental cause, and the aggressive, complex, and often overlapping patenting strategies are the rational effect. This dynamic creates a self-reinforcing cycle: the high cost of R&D justifies the creation of dense patent portfolios to ensure a return on investment; these portfolios, in turn, dramatically increase the cost, risk, and complexity for competitors seeking to enter the market, which further entrenches the innovator’s position and the high prices needed to sustain the model. The maze, therefore, is an emergent property of the industry’s underlying financial structure, not just an incidental feature of patent law. This report serves as a strategic guide to understanding and navigating this billion-dollar labyrinth, providing the critical insights needed to make informed decisions in this high-stakes arena.

II. The Foundation: Why Biologics Are Not Just “Big Pills”

To comprehend the unique challenges of patenting biologic drugs, one must first appreciate the profound scientific and regulatory distinctions that separate them from traditional, chemically synthesized small-molecule drugs. These differences are not merely academic; they form the bedrock upon which the entire legal, commercial, and strategic framework for biologics is built.

From Atoms to Antibodies: The Scientific Chasm Between Small Molecules and Biologics

The term “large molecule” only begins to capture the immense difference in scale and complexity between biologics and their small-molecule predecessors. This scientific chasm manifests in several critical areas that directly influence patent strategy.

Size and Structure

A typical small-molecule drug, like aspirin, is a simple, well-defined chemical compound consisting of perhaps 20 to 100 atoms.6 Its structure can be precisely characterized and reproduced. In stark contrast, a biologic, such as a monoclonal antibody, is a molecular titan. It can contain from 5,000 to 50,000 atoms and possess a molecular weight hundreds of times greater than a small molecule.6 More importantly, these proteins fold into intricate and unique three-dimensional (3D) structures. This complex conformation is not an incidental feature; it is absolutely integral to the drug’s biological activity and function.6 Even minor variations in this 3D structure can render the drug ineffective or, worse, unsafe.

Origin and Manufacturing: “The Process is the Product”

This structural complexity is a direct result of how biologics are made. Small-molecule drugs are manufactured through controlled chemical synthesis, a process that allows for exacting precision and results in batches that are chemically identical and consistent.12 Biologics, however, are produced in or derived from living organisms—such as mammalian cell cultures, bacteria, or yeast—using recombinant DNA technology.6

This living-system-based manufacturing is inherently variable. Minor, unavoidable fluctuations in the process—such as changes in temperature, cell culture media, or purification methods—can introduce subtle variations in the final product, a phenomenon known as “micro-heterogeneity”.15 This means that even within a single batch of a biologic, no two molecules are perfectly identical. Consequently, it is scientifically impossible for a competitor to create an exact replica of an innovator’s biologic. This fundamental reality gives rise to the critical distinction between a “generic” (an identical copy of a small-molecule drug) and a “biosimilar” (a product that is

highly similar to a reference biologic, with no clinically meaningful differences).15 It also underpins one of the most important doctrines in biologics IP:

“the process is the product.” Because the manufacturing process so profoundly defines the final product’s structure, safety, and efficacy, the process itself becomes a core, patentable asset.17

Stability and Administration

The delicate, complex structure of biologics makes them far less stable than small-molecule drugs. While a pill like ibuprofen can sit in a medicine cabinet for years without losing efficacy, most biologics are fragile and must be refrigerated at all times to maintain their 3D structure and function.11 This fragility, combined with their large size, also dictates their route of administration. Small molecules are often orally bioavailable and can be taken as pills.13 Biologics, however, are not orally active as they would be digested; they must be administered via injection or intravenous infusion.10

Mechanism of Action and Specificity

The structural complexity of biologics allows for highly specific mechanisms of action. Monoclonal antibodies, for example, are often designed to bind with exquisite specificity to a single target, such as a receptor on a cancer cell or a cytokine driving an autoimmune response.6 This high specificity generally leads to fewer off-target effects compared to small molecules, which can sometimes interact with multiple unintended targets throughout the body.10 While this is a therapeutic advantage, it creates unique patenting challenges, particularly when attempting to claim a broad family of molecules based on their function (e.g., “all antibodies that bind to target X”).

The “process is the product” concept is arguably the single most important scientific driver of the entire biologic patent maze. For small molecules, manufacturing methods are often protected as trade secrets or are the subject of secondary process patents. For biologics, this concept elevates the manufacturing process to a primary, core asset. The science dictates that minor process changes can yield significant product differences.15 Regulators, therefore, scrutinize the manufacturing process as an integral part of the Biologics License Application (BLA).7 This inextricable link means that patents covering novel aspects of manufacturing—such as proprietary cell lines, unique culture conditions, or innovative purification techniques—are as fundamental to protecting the commercial product as the composition of matter patent itself.1 This elevation of process patents incentivizes innovators to build a substantial portion of their patent thicket around manufacturing, a strategy that is both less common and less powerful in the small-molecule world.2 This, in turn, makes the BPCIA’s requirement for biosimilar developers to disclose their confidential manufacturing information a particularly high-stakes and strategically fraught step, creating a unique and formidable barrier to market entry.16

The Two Pillars of Protection: Interplay of Patent Rights and FDA Regulatory Exclusivity

Protecting a multi-billion-dollar biologic asset from competition relies on two distinct but complementary legal frameworks. A comprehensive lifecycle management strategy requires mastering the interplay between them.6

Patent Protection (USPTO)

Granted by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO), a patent provides the owner with the right to exclude others from making, using, or selling the patented invention for a term of approximately 20 years from the filing date.1 This is the primary and most flexible tool for building a long-term defensive fortress around a biologic. Patents can cover a wide range of inventions, from the molecule itself to its various formulations, manufacturing methods, and uses.1

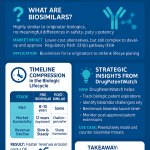

Regulatory Data Exclusivity (FDA)

Granted by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) upon approval of a new drug, regulatory exclusivity provides a fixed period of market protection that is independent of patent status.7 For a new reference biologic that receives its first license via a BLA, the BPCIA provides two key periods of exclusivity 19:

- 12-Year Data Exclusivity: The FDA may not approve a biosimilar application referencing the innovator product until 12 years after the date of the innovator’s first licensure.

- 4-Year Filing Exclusivity: A biosimilar developer cannot even submit its application to the FDA until 4 years after the innovator’s first licensure.

Other forms of FDA exclusivity can also apply, such as Orphan Drug Exclusivity (ODE), which grants 7 years of market exclusivity for drugs treating rare diseases, and Pediatric Exclusivity, which can add a 6-month extension to existing patents and exclusivities.21

Strategic Interplay

It is critical to understand that these two pillars of protection run in parallel; they are not additive.21 The 12-year data exclusivity provides a guaranteed, patent-independent shield against biosimilar competition in the product’s early life. However, an innovator’s patent strategy is designed to build a wall of protection that extends far beyond this 12-year period. A well-constructed patent thicket can delay biosimilar entry for many additional years, as demonstrated by numerous blockbuster biologics.1 The ultimate duration of market exclusivity for a biologic is therefore determined not by the 12-year clock alone, but by the strength, breadth, and expiration dates of its patent portfolio.

Table 1: Biologics vs. Small-Molecule Drugs: A Comparative Analysis of Key Attributes and IP Implications

| Attribute | Small-Molecule Drugs | Biologics | Strategic IP Implication |

| Size/Complexity | Low molecular weight (<900 Da); 20-100 atoms; simple, well-defined structure.6 | High molecular weight (>10 kDa); 5,000-50,000 atoms; complex, heterogeneous 3D structure.6 | The complexity of biologics makes them difficult to fully characterize, leading to heightened patent disclosure requirements (written description, enablement).6 |

| Manufacturing | Chemical synthesis; consistent and reproducible.6 | Produced in or derived from living organisms; inherent process-dependent variability and micro-heterogeneity.6 | The “process is the product” doctrine makes manufacturing process patents a core, high-value asset, critical for building a defensible patent thicket.1 |

| Structure | Definable and stable; can be precisely replicated to create identical “generics”.11 | Degradable and sensitive to manufacturing; cannot be perfectly replicated, leading to “biosimilars” instead of generics.11 | The inability to create identical copies is the basis for the separate BPCIA regulatory pathway and the “highly similar” standard for approval.16 |

| Stability | Generally shelf-stable at room temperature.11 | Often unstable; typically requires refrigeration to maintain structure and function.11 | Patents on novel, more stable formulations (e.g., allowing for longer storage or less stringent temperature controls) are a key lifecycle management strategy.23 |

| Administration | Often orally bioavailable (pills).10 | Typically requires injection or infusion.10 | Patents covering new delivery devices (e.g., auto-injectors) or formulations that improve patient convenience can provide significant, long-lasting market protection.24 |

| Specificity | Can have off-target effects due to lower specificity.10 | Typically exhibit high target specificity, leading to a more favorable side-effect profile.10 | While a therapeutic advantage, high specificity makes it harder to secure broad, functionally-defined patent claims (e.g., all antibodies binding a target) post-Amgen v. Sanofi.6 |

III. Building the Fortress: The Anatomy of an Innovator’s Patent Strategy

The immense investment required for biologic development creates a powerful imperative for innovator companies to secure the longest and most robust period of market exclusivity possible. This has given rise to sophisticated, multi-layered patent strategies designed not merely to protect a single invention, but to construct a formidable fortress around a blockbuster product.

Primary vs. Secondary Patents: The Blueprint of Exclusivity

An innovator’s patent portfolio is architected in layers, with each layer serving a distinct strategic purpose.

Primary Patents

These are the foundational patents that provide the initial period of exclusivity. They typically cover the core innovation—the new molecular entity itself.23 For a biologic, this is often a

composition of matter patent claiming the active molecule, for example, by its specific amino acid or nucleic acid sequence.2 These primary patents are the most valuable and provide the initial 20-year monopoly that is essential for recouping R&D costs.23

Secondary Patents

Long before the primary patent is set to expire, innovators engage in a continuous process of filing secondary patents to protect incremental improvements and related inventions. This strategy, often called lifecycle management, aims to extend the product’s effective commercial life. The landscape of secondary patents is vast and varied:

- Formulation Patents: These protect specific formulations of the drug, such as the combination of the active biologic with certain excipients, stabilizers, or buffers that might improve its stability, reduce immunogenicity, or allow for a more convenient dosage form (e.g., a high-concentration, citrate-free formulation to reduce injection pain).1

- Method of Use Patents: These patents do not claim the drug itself but rather a specific method of using it to treat a particular disease or patient population.1 As a biologic is studied over its lifecycle, new therapeutic applications are often discovered. Securing new method-of-use patents for these new indications is a powerful way to extend market protection.21

- Manufacturing Process Patents: As established, these are exceptionally important for biologics. Innovators continuously refine their manufacturing processes to improve yield, purity, or consistency. Each of these improvements—from the specific host cell line used for expression to novel protein purification protocols or methods for achieving a specific glycosylation profile—can be the subject of a new patent.1

- Device Patents: Many biologics are administered using specialized delivery devices, such as pre-filled syringes, auto-injectors, or infusion pumps. Patents on these devices can create a powerful and long-lasting barrier to competition. A biosimilar developer may have a non-infringing biologic, but if it cannot be delivered to the patient without infringing a device patent, its market potential is severely limited. This strategy can extend exclusivity for many years after the primary drug patent has expired.24

The Art of the Thicket: How a Web of Patents Creates a Moat

The strategic accumulation of these secondary patents around a single product leads to the formation of what is known as a “patent thicket.”

Defining “Patent Thickets” and “Evergreening”

A patent thicket is a dense, overlapping web of patent rights that a company builds around a single product.6 The practice of strategically filing these secondary patents to continuously extend a drug’s monopoly far beyond the life of its primary patent is known as

“evergreening”.1 This is a widespread practice; one analysis found that 78% of new patents issued for drugs were not for new medicines but for incremental changes to existing ones.2

“By seeking a multitude of patents for marginal aspects of a biologic, brand name drug companies are able to create a ‘thicket’ of patents that can dramatically extend exclusivity periods — blocking cheaper generics, or biosimilars, from coming to market.” 29

The strategic purpose of a patent thicket is not just to protect a series of individual inventions. It is a defensive strategy designed to create a formidable and complex barrier that exponentially increases the cost, time, risk, and uncertainty for any potential biosimilar competitor.6 A challenger must not defeat a single patent; they must navigate or invalidate every single patent in the thicket to achieve freedom to operate. This daunting legal and financial challenge can deter many potential competitors from even attempting to enter the market.17

Case Study in Focus: AbbVie’s Humira® – The Archetypal Patent Thicket

There is no better illustration of the power and complexity of a patent thicket than AbbVie’s strategy for its blockbuster biologic, Humira® (adalimumab). The Humira case is the archetypal example studied by IP professionals, business strategists, and policymakers.

By the Numbers

The scale of the Humira patent estate is breathtaking. AbbVie and its predecessors filed a total of 247 patent applications in the United States related to Humira, with the explicit goal of delaying competition for a potential 39 years.31 This resulted in over

130 granted patents.32 The timing of these filings is particularly revealing: a staggering

89% of the patent applications were filed after Humira was first approved by the FDA in 2002.31 Nearly half of the total applications were filed between 2014 and 2018, more than a decade after the product was on the market.31

The Anatomy of the Thicket

A deeper analysis reveals the structure of this fortress. Research has shown that the U.S. patent thicket was not just large, but also highly redundant. One study found that 80% of the U.S. patents in Humira’s core portfolio were “non-patentably distinct” from one another, meaning they covered essentially the same underlying inventions.32 These duplicative patents were often obtained through a procedural mechanism known as a “terminal disclaimer,” which allows an applicant to get a patent on an obvious variation of an earlier invention, provided it expires on the same date as the original.35 While legally permissible, this allowed AbbVie to transform just 14 distinct inventions into a portfolio of 73 granted patents.34 This stands in stark contrast to Humira’s European patent portfolio, which was dramatically smaller due to stricter patenting rules that make it more difficult to obtain such duplicative patents.34

The Economic Impact

The strategic effectiveness of the Humira thicket is undeniable. The primary patent on adalimumab expired in the U.S. in 2016. In Europe, where the patent portfolio was much smaller, biosimilars entered the market in October 2018.34 In the U.S., however, biosimilar developers were confronted with a wall of over 100 patents. Faced with the prohibitive cost and uncertainty of litigating this thicket, every biosimilar challenger ultimately settled with AbbVie, agreeing to delay their U.S. market entry until 2023—a full five years after their European launch.32

The financial consequences were enormous. In 2019, after biosimilars had launched in Europe, Humira’s international sales fell to $4.3 billion, while its U.S. sales, protected by the thicket, stood at $14.9 billion.33 This extended monopoly in the U.S. was estimated to have cost the healthcare system billions of dollars in potential savings.31

The Legal Challenge

AbbVie’s strategy was challenged in court as being anti-competitive and a violation of antitrust laws. However, these lawsuits were largely unsuccessful.37 The courts found that AbbVie’s conduct was generally protected by the

Noerr-Pennington doctrine, which provides immunity from antitrust liability for petitioning the government, including applying for and enforcing patents, unless the conduct is a “sham”.33 Because AbbVie had a reasonable success rate in obtaining its patents from the USPTO, the court ruled that its patenting activities were not “objectively baseless” and therefore did not meet the high bar required to be considered sham litigation.33

The Humira case reveals that the true power of a patent thicket lies not just in the number of patents, but in its structure and the legal mechanisms that enable its creation. A biosimilar developer needs freedom to operate, which means they must clear all blocking patents asserted against them.39 AbbVie’s strategy was not merely to obtain many patents, but to obtain many

duplicative patents covering the same core inventions, a practice permitted in the U.S. through continuation applications and terminal disclaimers.34 This forces a challenger into a war of attrition, compelling them to litigate dozens of patents that are legally distinct but inventively similar. The challenge becomes less about scientific invalidity and more about financial and legal endurance. The sheer cost and complexity of invalidating over 60 patents, even if many are individually weak, is exponentially higher than challenging a few strong ones.34 The thicket’s power, therefore, comes from exploiting a specific feature of U.S. patent prosecution to multiply the legal and financial burden on competitors, effectively weaponizing the litigation process itself as the primary barrier to market entry.

IV. The Gauntlet: The BPCIA and the Strategic “Patent Dance”

Recognizing that the existing Hatch-Waxman framework for small-molecule generics was ill-suited for the scientific complexities of biologics, Congress enacted the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA) in 2010.40 The BPCIA was designed with two primary goals: first, to create an abbreviated licensure pathway for biosimilars to promote competition and lower costs, and second, to establish a unique, structured process for identifying and resolving patent disputes

before a biosimilar launches.19 This pre-launch patent resolution framework, colloquially known as the “patent dance,” is a complex, high-stakes negotiation that has become a central feature of the biosimilar landscape.

Decoding the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA)

The BPCIA represents a fundamentally different approach to patent dispute resolution than the Hatch-Waxman Act. While Hatch-Waxman relies on a public listing of patents in the FDA’s “Orange Book” and an automatic 30-month stay of generic approval upon the filing of a lawsuit, the BPCIA created a private, multi-step information exchange process with no automatic stay.3 This intricate series of deadlines and disclosures is intended to bring order to potentially massive and complex patent disputes, allowing the parties to narrow the issues for litigation before the biosimilar hits the market.44

The Steps of the Dance: A Tactical Walkthrough

The patent dance is a highly choreographed process governed by strict statutory timelines. While the full process is detailed, the key strategic steps are as follows 16:

- The Opening Move (Day 0): Within 20 days of the FDA accepting its abbreviated Biologics License Application (aBLA) for review, the biosimilar applicant kicks off the dance by providing the Reference Product Sponsor (RPS) with a confidential copy of its aBLA and detailed information about its manufacturing process. This is a critical and often contentious step, as it requires the disclosure of highly sensitive trade secrets.

- The Innovator’s List (Day 60): The RPS reviews the provided information and, within 60 days, provides the applicant with a list of all patents for which it believes a claim of infringement could reasonably be asserted (the “3A list”).

- The Challenger’s Rebuttal (Day 120): The biosimilar applicant has 60 days to respond with a detailed statement explaining, on a claim-by-claim basis, why it believes the listed patents are invalid, unenforceable, or will not be infringed. The applicant may also provide its own list of patents it believes are relevant.

- The Innovator’s Sur-Rebuttal (Day 180): The RPS then has 60 days to provide its own detailed rebuttal, responding to the applicant’s invalidity and non-infringement arguments.

- Negotiating the First Wave (Days 180-230): With the initial contentions exchanged, the parties have a 50-day window to negotiate in good faith to agree on a final, manageable list of patents that will be litigated in the “first wave” of litigation.

- Simultaneous Exchange (Day 250): If the parties cannot agree on a list, they proceed to a simultaneous exchange. The applicant provides a list of the patents it is willing to litigate, and the RPS provides its own list. The BPCIA includes specific rules limiting the number of patents the RPS can list, which is tied to the number listed by the applicant.

- First Wave Litigation (Day 280): Within 30 days of the final list being established (either by agreement or exchange), the RPS must file a patent infringement lawsuit based only on the patents on that list.

This entire process, if followed to completion, can take approximately eight to nine months.45 Separately, the BPCIA requires the biosimilar applicant to provide the RPS with a

180-day notice of commercial marketing before it can launch its product. This notice triggers the “second wave” of litigation, where the RPS can seek a preliminary injunction and sue for infringement on any patents that were on its initial 3A list but were not litigated in the first wave.45

To Dance or Not to Dance? The Post-Amgen v. Sandoz Strategic Calculus

For years, a central question was whether this complex dance was mandatory. In 2017, the Supreme Court provided a definitive answer in Sandoz Inc. v. Amgen Inc., ruling that the patent dance is not mandatory under federal law.45 A biosimilar applicant cannot be forced to participate. This decision transformed the dance from a required procedure into a critical strategic choice with significant consequences for both sides.

Consequences of Opting Out (for the Biosimilar Applicant)

A biosimilar developer who chooses to bypass the dance faces several repercussions 45:

- Loss of Control: The decision of when, where, and on which patents to litigate shifts entirely to the RPS. The innovator can immediately file a broad infringement suit on any patent that claims the biological product or its use, without the limitations imposed by the first-wave litigation process.

- Forfeiture of Rights: The applicant loses the right to file a declaratory judgment action to proactively challenge the validity of the innovator’s patents.

- Potential for Enhanced Damages: Opting out may forfeit certain statutory limitations on the recovery of damages in the ensuing litigation.

Strategic Considerations

The decision to participate is a complex risk-reward calculation.

- Why Dance? A biosimilar developer might choose to participate to gain a measure of control. The dance provides a structured framework to narrow the scope of the initial, costly litigation down to a manageable number of key patents. It also preserves the applicant’s full range of legal options for challenging those patents.

- Why Sit It Out? The primary reason to opt out is to protect highly sensitive manufacturing process information. The first step of the dance requires turning over the “keys to the kingdom”—the detailed blueprint of how the biosimilar is made. For many developers, the risk of this proprietary information being exposed outweighs the procedural benefits of the dance. Others may opt out to accelerate timelines or to avoid being drawn into a protracted, resource-draining process.

The intricate design of the BPCIA patent dance, originally intended to foster an orderly, pre-launch resolution of disputes, has had a profound and perhaps unintended consequence: it has created a system of “managed competition” driven by widespread settlements. The process is so lengthy, expensive, and fraught with risk for both parties that it creates powerful incentives to find a negotiated off-ramp rather than see the process through to its litigious conclusion. The dance requires the biosimilar developer to expose its most valuable trade secrets, while the innovator faces the risk of its key patents being invalidated in two separate waves of litigation. The sheer number of patents in a typical thicket makes litigating them all to a final verdict a multi-year, multi-million-dollar endeavor with an uncertain outcome.3 Faced with this landscape, it is often more commercially rational for both sides to settle. Data confirms this trend, with one analysis showing that 67% of terminated BPCIA litigations ended in settlement.46 These settlements frequently involve staggered market entry dates, as famously seen with Humira, where multiple biosimilar competitors agreed to launch in an orderly fashion in 2023.32 Thus, the BPCIA’s complexity does not often produce clear winners and losers in court; instead, it fosters a business environment where the timing and pace of competition are negotiated behind closed doors. The maze is not solved; it is bypassed through strategic deals, a reality far removed from the more aggressive, price-driven competition seen in the small-molecule generic market.

Table 2: The BPCIA “Patent Dance” – A Step-by-Step Timeline and Strategic Considerations

| Step | Timeline (Days) | Action Required | Biosimilar Applicant’s Strategic Consideration | Innovator’s (RPS) Strategic Consideration |

| 0 | N/A | Decision Point: Applicant decides whether to initiate the dance. | Participate: Control initial litigation scope, preserve DJ rights. Opt-Out: Protect manufacturing trade secrets, but cede control of litigation timing/scope. | Prepare for immediate, broad litigation if applicant opts out. If they opt-in, prepare to analyze sensitive manufacturing data. |

| 1 | Day 0 | Applicant provides aBLA and manufacturing info to RPS. | The most critical risk point: disclosure of highly confidential trade secrets. Is the procedural benefit worth this risk? | A crucial intelligence-gathering opportunity to understand the competitor’s process and identify potential infringement. |

| 2 | Day 60 | RPS provides its “3A list” of potentially infringed patents. | Analyze the list to gauge the scale of the challenge. A long list signals an aggressive, costly defense. | Strategic decision on breadth: A comprehensive list preserves rights for second-wave litigation, but a targeted list may focus negotiations. |

| 3 | Day 120 | Applicant provides detailed non-infringement/invalidity arguments. | Opportunity to signal strength and focus the dispute on the weakest patents. A strong showing may encourage early settlement. | First look at the challenger’s legal strategy and the prior art they will rely on. Assess the vulnerability of the portfolio. |

| 4 | Day 180 | RPS provides its detailed rebuttal to the applicant’s arguments. | Evaluate the strength of the innovator’s counter-arguments to refine litigation strategy and settlement position. | Opportunity to defend the patent portfolio’s strength and deter the challenger from proceeding with costly litigation. |

| 5 | Days 180-230 | Parties negotiate a list of patents for first-wave litigation. | A key negotiation to limit the scope and cost of the initial lawsuit. Success here can save millions in legal fees. | A chance to focus the initial fight on the strongest patents to secure an early victory or favorable settlement terms. |

| 6 | Day 250 | If no agreement, parties simultaneously exchange patent lists. | A tactical choice. Listing fewer patents forces the innovator to also limit their list, but may leave key threats unaddressed until the second wave. | Must carefully select the most critical patents within the BPCIA’s numerical limits, balancing immediate and future threats. |

| 7 | Day 280 | RPS files the “first wave” infringement suit. | The formal litigation begins. The scope is now set, and resources must be allocated for a multi-year legal battle. | The lawsuit is filed, but the “second wave” remains a future threat, contingent on the 180-day notice. |

| 8 | N/A | Applicant provides 180-day Notice of Commercial Marketing. | Triggers the second wave of litigation. Timing is strategic: can be given before or after FDA approval to manage litigation timelines. | The final trigger to assert all remaining patents from the 3A list and seek a preliminary injunction to block the launch. |

V. The Challenger’s Playbook: Strategies for Navigating the Maze

For a biosimilar developer, the innovator’s patent fortress is not an impenetrable wall but a complex maze that must be systematically navigated. Success requires a sophisticated, multi-pronged strategy that blends deep legal analysis, cutting-edge science, and astute business judgment. The investment is substantial—developing a biosimilar can cost between $100 million and $300 million—making a well-executed IP strategy essential to protecting this investment.49

The First Line of Defense: Conducting a Robust Freedom-to-Operate (FTO) Analysis

Before significant resources are committed, the foundational step for any biosimilar program is a comprehensive Freedom-to-Operate (FTO) analysis. This is not a perfunctory legal task but a core business strategy that informs the entire development pathway.39

FTO vs. Patentability

It is vital to distinguish FTO from patentability. Patentability analysis asks, “Can I get a patent on my own invention?” It is about securing offensive rights. FTO analysis asks, “Can I commercialize my product without being sued for infringing someone else’s patents?” It is a defensive necessity.39 Owning a patent on a novel manufacturing process for a biosimilar does not grant the right to sell that biosimilar if doing so infringes the innovator’s primary patent on the molecule itself.

The FTO Process

A robust FTO analysis is a systematic, multi-phase process 39:

- Scoping: This initial phase defines the analysis. It involves deconstructing the proposed biosimilar product into its key technical features (the molecule, formulation, manufacturing process, delivery device) and defining the key commercial jurisdictions (e.g., U.S., Europe, Japan) where the product will be made and sold.

- Searching: This involves a comprehensive search of in-force patents and published applications in the defined jurisdictions. This goes beyond simple keyword searches and employs a multi-pronged strategy using patent classification systems, assignee/inventor searches, and citation analysis, often leveraging powerful commercial databases and specialized platforms.

- Analysis: This is the most critical phase, where patent attorneys meticulously analyze the claims of the identified patents. Infringement is determined only by what is legally claimed, not what is described in the rest of the patent. Each element of a patent’s claims is mapped against the features of the proposed biosimilar product.

- Risk Stratification: The output is not a simple “yes” or “no” but a spectrum of risk. Potentially problematic patents are stratified into tiers—High, Medium, and Low—based on the likelihood of infringement, the legal strength of the patent, and its commercial impact.

The Cost-Benefit Analysis

While a comprehensive FTO analysis can cost from $50,000 to over $500,000 for a complex biologic, this expense should be viewed as a high-yield insurance policy.39 This investment is a fraction of the $100-$300 million at risk in the development program and pales in comparison to the multi-million-dollar cost of patent litigation.3 Conducting FTO early allows a developer to make strategic pivots—such as designing around a blocking patent or abandoning a high-risk project—before millions in R&D costs are sunk.

Attacking the Fortress: Challenging Patent Validity

When an FTO analysis identifies high-risk blocking patents that cannot be avoided, the biosimilar developer must go on the offensive. The primary strategies involve challenging the validity of the innovator’s patents.

District Court Litigation

This is the traditional pathway for patent challenges and is the ultimate forum for resolving disputes under the BPCIA. It is also the most expensive and time-consuming option, with a typical case lasting three to five years and costing millions of dollars through trial and appeal.3 However, it is the only forum where a patent can be challenged on all possible grounds of invalidity, including lack of written description and enablement, which are often potent arguments against broad biologic patent claims.

Inter Partes Review (IPR): A Faster, More Focused Assault

Since its creation in 2012, the Inter Partes Review (IPR) process has become a key strategic weapon for biosimilar developers.52 An IPR is a trial proceeding conducted before technically expert administrative patent judges at the USPTO’s Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) to review the patentability of claims based on prior art patents and printed publications.

- The IPR Advantage: IPRs are highly attractive to challengers for several reasons 52:

- Speed: A final decision is typically rendered within 18 months of filing.

- Cost: While still significant, an IPR is substantially less expensive than district court litigation.

- Lower Burden of Proof: The challenger must prove unpatentability by a “preponderance of the evidence,” a lower standard than the “clear and convincing evidence” required in district court.

- Technical Expertise: The PTAB judges have scientific or technical backgrounds, which can be an advantage when arguing complex technical issues.

- Effectiveness and Trends: Data on IPRs for biologic patents reveals a nuanced picture. The rate at which the PTAB agrees to institute an IPR on a biologic patent is lower than for other technologies, with an all-time average institution rate of 55%.54 However,

once an IPR is instituted, the success rate for the challenger is remarkably high. One study found that for instituted biologic patents, 70% of final written decisions resulted in all challenged claims being found unpatentable.54 This makes IPR a high-risk, high-reward proposition. - Strategic Limitations: The most significant limitation of an IPR is that a patent can only be challenged on grounds of novelty and obviousness based on prior art. Crucially, IPRs cannot be used to argue that a patent is invalid for lack of written description or enablement—often the most powerful arguments against the validity of broad biologic patent claims.52

Inventing Around: The Science and Strategy of “Design-Arounds”

A third strategic option is to use science to navigate the legal maze. A “design-around” involves modifying the biosimilar product or, more commonly, its manufacturing process in a way that avoids infringing the specific language of an innovator’s patent claims.56 For example, if an innovator has a patent on a specific protein purification process using a particular sequence of chromatography steps, a biosimilar developer could invent a new, non-infringing purification process that achieves a similar result. This is a delicate balancing act. The new process must be different enough to avoid infringement, but the final product must remain “highly similar” to the reference biologic to qualify for the abbreviated regulatory approval pathway.57 A successful design-around requires deep scientific expertise, a thorough understanding of the patent landscape, and can lead to new, patentable innovations for the biosimilar developer itself.59

For a biosimilar developer, the strategic challenge is not a simple binary choice of whether to litigate. It is a sophisticated portfolio management problem that requires deciding which patents in the thicket to challenge, where to challenge them (PTAB or district court), and when. A brute-force approach of challenging every patent is financially unviable. A more refined strategy involves triaging the innovator’s patent portfolio based on vulnerability. The “scalpel” of the IPR process is best used for targeted strikes against weaker secondary patents—such as those on formulations or specific methods of use—that are most susceptible to obviousness challenges based on prior art.52 This can efficiently clear away some of the underbrush of the thicket. This, in turn, allows the developer to preserve its “heavy artillery”—the substantial budget required for district court litigation—for the core composition of matter or key manufacturing patents. These foundational patents are often best challenged in court, where arguments based on enablement and written description, which are disallowed in IPRs, can be fully deployed.52 This multi-forum, targeted approach optimizes the allocation of capital, manages risk, and increases the overall probability of successfully clearing a path to market.

Table 3: A Biosimilar Developer’s Strategic Options for a Blocking Patent

| Strategy | Primary Goal | Estimated Cost | Typical Timeline | Key Advantages | Key Risks/Disadvantages |

| District Court Litigation | Invalidate patent(s) on any legal grounds. | $5M+ through trial and appeal.3 | 3-5+ years | Allows for all invalidity arguments (including enablement/written description); can resolve entire dispute in one forum. | Extremely high cost; very long timeline; high legal standard (“clear and convincing evidence”). |

| IPR Challenge | Invalidate patent(s) on prior art grounds only. | $500k – $1M+ | 18 months | Faster, cheaper, lower burden of proof (“preponderance of the evidence”), expert technical judges.52 | Limited grounds (no enablement/written description challenges); risk of estoppel if unsuccessful. |

| License-In | Gain legal permission to use the patented technology. | Varies (upfront fees + royalties on sales). | Months to a year+ (negotiation). | Provides certainty and speed to market; avoids litigation risk and cost. | Ongoing cost reduces margins; may fund a competitor; requires a willing licensor. |

| Design Around | Modify product/process to avoid infringement. | Varies (significant R&D investment). | 1-3+ years (R&D and validation). | Avoids licensing fees; can create new, proprietary IP for the developer. | May cause significant delays; risk of suboptimal product; may still face infringement suits. |

| At-Risk Launch | Launch the product despite the patent, planning to litigate if sued. | Potentially highest cost (litigation + treble damages if willful infringement is found). | Immediate market entry. | Potential for first-mover advantage among biosimilars; puts pressure on the innovator. | Extreme financial and legal risk; could result in a market-destroying injunction and massive damages. |

VI. The Market Impact: Competition, Costs, and the Future of Access

The complex legal and strategic battles fought over biologic patents are not abstract exercises. They have profound, real-world consequences for the entire healthcare ecosystem, dictating the pace of competition, the cost of medicines, and ultimately, patient access to innovative therapies.

The Bottom Line: Economic Impact of Biosimilar Entry

The primary promise of the BPCIA was that biosimilar competition would drive down the high cost of biologic drugs, generating substantial savings for patients and payers. The results, thus far, have been significant but uneven.

Savings Potential

The potential for savings is immense. Projections have estimated that biosimilars could save the U.S. healthcare system over $180 billion in the next five years alone.20 A 2017 RAND Corporation study projected savings of

$54 billion over the decade from 2017 to 2026.60 The delay of Humira biosimilars alone was estimated to have cost Medicare programs

$2.19 billion in lost savings from 2016 to 2019.36 These figures underscore the enormous financial stakes involved in biosimilar market entry.

Price Erosion

Data clearly shows that biosimilar competition works to lower prices. The introduction of biosimilars leads to a decline in the overall average sales price for a given molecule (including both the reference product and its biosimilars). The magnitude of this price drop is directly correlated with the level of biosimilar uptake. For molecules where biosimilars have captured a high market share (>60%), prices have fallen dramatically, with reductions ranging from 21% to over 59%.61 Overall, costs for molecules with biosimilar competition are down between 18% and 50%.9

Adoption Rates – A Mixed Bag

While the price impact is clear, the rate at which biosimilars are adopted in the U.S. has been a mixed bag, revealing that patent clearance is only the first hurdle.

- Success Stories: Recent oncology biosimilars have seen rapid and successful launches. Biosimilars for bevacizumab (Avastin®), trastuzumab (Herceptin®), and rituximab (Rituxan®), all launched around 2019, achieved remarkable market shares of 82%, 80%, and 67%, respectively, within their first three years.9 This level of uptake is comparable to, or even exceeds, that seen in European markets.

- Slower Uptake: In contrast, earlier biosimilar launches faced significant headwinds. The biosimilar for infliximab (Remicade®), which launched in 2016, captured only 3% of the market volume after one year and a modest 13% after three years.9 Its market share has since grown to over 40%, but only after a long, slow climb.9

Several factors contribute to this variation in uptake. Innovator companies often employ post-launch commercial strategies, such as offering substantial rebates to payers and pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) to maintain preferred formulary status for the reference product, creating “rebate walls” that disincentivize switching to a biosimilar.9 Furthermore, prescriber and patient confidence, along with the lack of an “interchangeable” designation from the FDA—which would allow for automatic substitution at the pharmacy level like a generic drug—can create additional friction and slow adoption.63

Landmark Litigation Beyond Humira: Enbrel® and Herceptin®

While the Humira case is the most famous example of a patent thicket, other landmark litigation has shaped the strategic landscape.

Amgen’s Enbrel®: A Masterclass in Long-Term Defense

Amgen’s Enbrel® (etanercept) provides a powerful counter-narrative to the Humira story. Originally approved by the FDA in 1998, Enbrel remains without biosimilar competition in the U.S. and is projected to maintain its monopoly until 2029.66 This remarkable 31-year period of exclusivity was not achieved through a massive thicket of over a hundred patents, but by successfully defending a few key, late-expiring patents covering the fusion protein itself and its method of manufacture.67 In a series of legal victories against Sandoz and Samsung Bioepis, Amgen proved the validity of these critical patents, demonstrating that a well-crafted, defensible core patent portfolio can be just as effective, if not more so, than a sprawling thicket.66

Genentech’s Herceptin®: A Multi-Front War

The battle over Herceptin® (trastuzumab) illustrates the complexity of defending a blockbuster against multiple, simultaneous challengers. Genentech faced a barrage of attacks on its Herceptin patent portfolio from numerous biosimilar developers, including Pfizer, Amgen, and Celltrion.69 The fight was waged across multiple fronts: in district court through the BPCIA patent dance and in the USPTO through dozens of IPR petitions (over 30 IPRs were filed against Herceptin patents).69 The immense cost and complexity of this multi-front war ultimately led Genentech to enter into settlement agreements with its various challengers, paving the way for multiple biosimilar launches starting in 2019.70 The Herceptin case highlights the significant resource drain and strategic challenge of fending off a coordinated assault from a competitive field of biosimilar developers.

The Role of Strategic Intelligence: Leveraging Data for Competitive Advantage

The complexity of this landscape—with its overlapping patents, intricate litigation pathways, and dynamic market access factors—makes strategic intelligence an indispensable tool. Navigating the maze effectively is impossible without a clear, data-driven map of the terrain. This is where specialized patent intelligence platforms become critical assets for both innovator and biosimilar companies.73

Platforms like DrugPatentWatch provide a fully integrated view of the pharmaceutical landscape, combining patent data with regulatory information, litigation updates, clinical trial data, and market analytics.76

- For Biosimilar Developers, such a platform is essential for the entire development lifecycle. It allows them to perform initial landscape analysis to select promising target molecules, identify all relevant patents and their expiration dates to inform a robust FTO analysis, track ongoing litigation to assess the strengths and weaknesses of an innovator’s portfolio, and identify potential “at-risk” launch opportunities where key patents may be vulnerable.4

- For Innovator Companies, these tools are vital for competitive intelligence and lifecycle management. They enable innovators to monitor the biosimilar development pipeline, anticipate which products will face competition and when, analyze the past successes and failures of potential challengers, and identify “white space” for filing new secondary patents to strengthen their own defensive thickets.74

In today’s environment, relying on manual searches or disparate data sources is no longer viable. The ability to access and analyze integrated, real-time data is a fundamental requirement for making sound strategic decisions, whether it’s deciding which biosimilar to develop, how to structure a patent thicket, or when to pursue a settlement.

The slow initial uptake of biosimilars like infliximab reveals a critical truth: breaking through the patent maze is only the first half of the battle. A biosimilar developer can successfully navigate years of complex litigation and win the right to market their product, only to face a second, equally challenging maze of market access. This commercial maze is constructed from different materials—payer rebate structures, PBM formularies, physician incentives, and the lack of automatic substitution at the pharmacy—but its effect is the same: it can neutralize the competitive impact of a successful patent strategy. Innovator companies, having lost the patent fight, can pivot to a commercial strategy, leveraging “rebate walls” to make it financially unattractive for payers to prefer the lower-list-price biosimilar.9 Furthermore, without an “interchangeable” designation, pharmacists cannot automatically substitute the biosimilar for the reference product, creating significant friction that hinders uptake.63 This means that an innovator’s defensive strategy does not end with its patents; it can extend into a commercial “thicket” of contracts and rebates that serves as a powerful post-launch barrier. For biosimilar developers, this reality dictates that a comprehensive market access strategy must be developed in parallel with their IP strategy from the very beginning of the development program.

VII. The Horizon: Patenting the Next Generation of Biologics

As the biopharmaceutical industry pushes into new frontiers of medicine, the patent maze is poised to become even more complex. The rise of revolutionary platforms like cell and gene therapies (CGTs) and mRNA technologies presents a new wave of unprecedented intellectual property challenges that will define the next generation of patent law and strategy.

The New Frontier: Cell and Gene Therapies (CGTs) and mRNA Technologies

These next-generation therapeutics are fundamentally different from traditional biologics like monoclonal antibodies, and these differences create unique IP hurdles.

Unique IP Challenges of “Living Drugs”

Cell and gene therapies, such as CAR-T therapies for cancer, are often described as “living drugs.” They are not single molecules but complex, multi-component systems that are frequently personalized for each patient.77 This creates a host of IP challenges:

- Complexity of the “Product”: What is the patentable invention? Is it the therapeutic gene sequence, the viral vector used to deliver it, the gene-editing tool (like CRISPR) used to modify the cells, or the final, engineered cell product itself? Innovators are filing patents on all these components, creating an incredibly dense and overlapping IP landscape from the outset.77

- The Process is the Invention: For CGTs, the manufacturing process is not just integral to the product; it is often the core invention. The bespoke, patient-specific protocols for selecting, modifying, and expanding cells are highly innovative and complex.77 This makes process patents even more critical than for traditional biologics.

- The Rise of Trade Secrets: Given the difficulty of fully describing and patenting these highly customized manufacturing processes without enabling competitors, many companies are opting to protect critical aspects of their CGT manufacturing as closely guarded trade secrets.28 This reliance on secrecy creates a different kind of barrier to future competition.

- The Question of a “Biosimilar” CGT: The very concept of a biosimilar for a personalized CAR-T therapy is fraught with difficulty. How can a competitor prove their product is “highly similar” when the starting material is the patient’s own cells and the manufacturing process is bespoke? The regulatory, manufacturing, and IP hurdles for creating a follow-on CGT are immense and largely uncharted.77

The mRNA Revolution

The rapid development and deployment of mRNA vaccines for COVID-19 highlighted the power of this new therapeutic platform, but also brought its unique patent issues to the forefront.79 The patent landscape for mRNA technology is layered and contentious:

- Platform vs. Product: Is the key invention the specific mRNA sequence that codes for a viral antigen (the “product”), or is it the underlying platform technology that makes it work?

- Key Platform Components: The critical innovations in mRNA technology often lie in the platform elements, such as chemical modifications to the mRNA molecule to make it more stable and less immunogenic, and the lipid nanoparticle (LNP) delivery system used to encapsulate the mRNA and deliver it into cells. Multiple companies hold foundational patents on these platform components, leading to complex licensing negotiations and litigation.79

- Future Thickets: This platform-based approach creates the potential for new types of patent thickets. A company that controls key patents on LNP technology, for example, could potentially block not just one vaccine, but any future mRNA vaccine or therapeutic that uses that delivery system.80

The emergence of CGTs and mRNA technologies may signal a fundamental shift in patent strategy, moving from the product-centric thickets seen with Humira to more powerful and durable platform-centric thickets. A product-specific patent portfolio controls a single drug. A platform-specific patent portfolio—covering a core technology like an LNP delivery system, a viral vector, or a gene-editing tool—could potentially control an entire class of future therapies that rely on that platform. A competitor would no longer be able to “design around” the features of a single product; they would be forced to invent an entirely new, non-infringing platform, a scientific and IP barrier of a much higher order. The next generation of blockbuster patent battles may not be fought over individual molecules, but over the foundational technological platforms that will produce the medicines of the future. The company that wins this battle could control entire therapeutic areas for decades, making today’s patent maze look like a simple, straight path by comparison.

The Quest for Harmony: The Future of International Biologic Patent Law

The challenges of patenting biologics are not confined to the United States. As biopharmaceutical development is a global enterprise, companies must navigate a patchwork of different national and regional patent laws. There are ongoing efforts at international bodies like the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) and through industry and government groups like Group B+ to promote the harmonization of substantive patent law, with the goal of simplifying procedures and reducing costs for innovators.81

However, significant differences remain between key jurisdictions like the U.S., Europe, and major Asian markets.39 These include differing rules on:

- Patentable Subject Matter: For example, methods of medical treatment are patentable in the U.S. but are generally not patentable in Europe (though claims to a substance for use in a method of treatment are allowed).

- Grace Periods: The U.S. provides a one-year grace period for an inventor’s own public disclosures, while Europe has virtually no grace period, requiring absolute novelty at the time of filing.

- Double Patenting: As seen in the Humira case, U.S. law is more permissive of obtaining multiple, non-patentably distinct patents on the same invention via terminal disclaimers, a practice that is much more difficult in Europe.34

These differences require companies to develop sophisticated, jurisdiction-specific patent filing and enforcement strategies, adding another layer of complexity to the global biologic patent maze.

VIII. Conclusion

The world of biologic drug patents is a dynamic and formidable labyrinth, shaped by the convergence of cutting-edge science, unforgiving economics, and evolving law. It is a domain where intellectual property is not an afterthought but the central pillar of business strategy, dictating market dynamics, fueling innovation, and ultimately determining patient access to transformative medicines. Successfully navigating this maze requires more than just legal expertise; it demands a holistic, strategic mindset that integrates R&D, commercial, and legal considerations from the earliest stages of development.

Key Takeaways

- Science is the Genesis: The fundamental scientific complexity of biologics—their large size, intricate 3D structures, and process-dependent manufacturing—is the root cause of their unique and challenging patent landscape. The “process is the product” doctrine is not a legal fiction but a scientific reality that elevates manufacturing patents to a core strategic asset.

- The Innovator’s Moat is Dual-Layered: An innovator’s market exclusivity is built on two pillars: a fixed 12-year period of FDA data exclusivity and a flexible, potentially much longer period of patent protection. A successful lifecycle strategy depends on building a multi-layered patent thicket of primary and secondary patents designed to extend market dominance long after the initial regulatory exclusivity has expired.

- The BPCIA is a Strategic Gauntlet: The BPCIA, intended to create an orderly pathway for biosimilar competition, has instead established a complex, costly, and high-stakes legal gauntlet. Its intricate “patent dance” and lack of an automatic litigation stay have created a landscape where negotiated settlements and managed market entry often become more rational commercial outcomes than all-out litigation.

- The Challenger’s Playbook is Multi-Faceted: For biosimilar developers, success is not about finding a single silver bullet. It requires a multi-pronged offensive: beginning with deep Freedom-to-Operate analysis, followed by targeted patent challenges using a combination of faster, narrower IPRs and broader, more expensive district court litigation, and complemented by sophisticated scientific “design-around” capabilities.

- The Maze Has Two Parts: Breaking through the patent maze is only the first half of the battle for a biosimilar. The second, equally critical challenge is navigating the commercial maze of market access, which is defined by payer rebate walls, physician incentives, and the lack of automatic substitution. A winning strategy must address both IP and market access hurdles in parallel.

- Intelligence is Non-Negotiable: In this high-stakes environment, strategic patent intelligence is not a luxury but a necessity. Leveraging integrated data platforms like DrugPatentWatch to monitor patent expirations, track litigation, and analyze competitor pipelines is essential for making informed, data-driven decisions that can mean the difference between market success and failure.

- The Horizon is More Complex: The future of biologics IP, driven by cell and gene therapies and mRNA platforms, will be defined by even greater complexity. The strategic focus is likely to shift from product-specific patent thickets to broader, more powerful platform-based monopolies, presenting a new generation of challenges and opportunities.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. What is the single biggest difference between patenting a biologic versus a small-molecule drug?

The single biggest difference stems from the “process is the product” doctrine. For a small-molecule drug, the patent focus is overwhelmingly on the final, well-defined chemical structure. For a biologic, because its final structure and function are inextricably linked to the variable process used to create it in living cells, patents on the manufacturing process (e.g., the specific cell line, purification methods) are just as critical and valuable as patents on the molecule’s sequence itself. This elevates the entire manufacturing operation from a trade secret to a core, patentable asset.

2. Why would a biosimilar company ever choose not to participate in the BPCIA “patent dance”?

The primary reason is to protect its own intellectual property. The first step of the dance requires the biosimilar applicant to provide the innovator with its complete FDA application and, crucially, detailed information about its proprietary manufacturing process. For many companies, this information represents their most valuable trade secrets. They may calculate that the risk of handing this “blueprint” to a direct competitor outweighs the procedural benefits of the dance (like narrowing the scope of initial litigation), choosing instead to face a broader, more immediate lawsuit where they can keep their process confidential for longer.

3. Is building a “patent thicket” illegal?

Generally, no. Building a patent thicket by filing numerous patents on various aspects of a single product is a legal and, from an innovator’s perspective, a rational economic strategy to protect a massive investment. Antitrust challenges against patent thickets, like the one against Humira, have been largely unsuccessful. Courts have been reluctant to penalize companies for using the patent system as it was designed, even if the result is a formidable barrier to competition. A challenge typically succeeds only if the patenting conduct can be proven to be a “sham,” meaning the patents were obtained fraudulently or were “objectively baseless,” a very high legal standard to meet.

4. How has the Supreme Court’s Amgen v. Sanofi decision changed how biologic patents are written and challenged?

The Amgen v. Sanofi decision significantly raised the bar for the “enablement” requirement for biologic patents. The Court ruled that to claim a broad class of antibodies by their function (e.g., “all antibodies that bind to protein X and block its function”), the patent must teach someone skilled in the art how to make and use the full scope of that claimed class without undue experimentation. Simply providing a few examples and a general roadmap is no longer sufficient. This decision makes it much harder for innovators to obtain broad, functionally-defined patents. Strategically, this forces innovators to file more numerous, narrower patents tied to specific structures (contributing to thickets) and gives biosimilar challengers a powerful new argument to invalidate overly broad patent claims on enablement grounds.

5. With all these patent barriers, what is the realistic prospect for biosimilars to actually lower healthcare costs in the U.S.?

The prospect is strong, but the path is challenging and the savings will not be as immediate or as deep as with small-molecule generics. While patent thickets and litigation can cause significant delays (as seen with Humira), biosimilars are coming to market and driving down prices, especially in the oncology space where uptake has been rapid. Projections still point to over $100 billion in savings in the coming years. However, the full potential will only be realized if policymakers address not just patent system abuses but also the post-launch market access barriers, such as rebate walls and the slow adoption of interchangeability, that can stifle competition even after patent hurdles are cleared.

Works cited

- The Role of Patents and Regulatory Exclusivities in Drug Pricing | Congress.gov, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/R46679

- The Dark Reality of Drug Patent Thickets: Innovation or Exploitation? – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-dark-reality-of-drug-patent-thickets-innovation-or-exploitation/

- Managing Drug Patent Litigation Costs: A Strategic Playbook for the …, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/managing-drug-patent-litigation-costs/

- Exploring Biosimilars as a Drug Patent Strategy: Navigating the Complexities of Biologic Innovation and Market Access – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/exploring-biosimilars-as-a-drug-patent-strategy-navigating-the-complexities-of-biologic-innovation-and-market-access/

- Patent protection strategies – PMC, accessed August 18, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3146086/

- Securing Innovation: A Comprehensive Guide to Drafting and Prosecuting Patent Applications for Biologic Drugs – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/drafting-drug-patent-applications-for-biologic-drugs/

- Navigating the Complexities of Biologic Drug Patents – PatentPC, accessed August 18, 2025, https://patentpc.com/blog/navigating-complexities-biologic-drug-patents

- Intellectual Property Protection for Biologics – Academic Entrepreneurship for Medical and Health Scientists, accessed August 18, 2025, https://academicentrepreneurship.pubpub.org/pub/d8ruzeq0

- Biosimilars in the United States 2023-2027 – IQVIA, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.iqvia.com/insights/the-iqvia-institute/reports-and-publications/reports/biosimilars-in-the-united-states-2023-2027

- Small Molecules vs. Biologics: Key Drug Differences – Allucent, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.allucent.com/resources/blog/points-consider-drug-development-biologics-and-small-molecules

- Small Molecule vs Biologics – YouTube, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WCC2dJGX7pQ

- Differences between Biologics and Small Molecules | UCL …, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.ucl.ac.uk/therapeutic-innovation-networks/differences-between-biologics-and-small-molecules

- Biologics vs. Small Molecule Drugs: Which Are Better? – Ascendia Pharmaceutical Solutions, accessed August 18, 2025, https://ascendiacdmo.com/newsroom/2021/10/27/biologics-vs-small-molecule-drugs

- Difference Between Small Molecule and Large Molecule Drugs – Caris Life Sciences, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.carislifesciences.com/difference-between-small-molecule-and-large-molecule-drugs/

- Biologics, Biosimilars, and Generics – Analysis Group, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.analysisgroup.com/biologics-biosimilars-and-generics/

- Taking Advantage of the New Purple Book Patent Requirements for Biologics, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.morganlewis.com/pubs/2021/04/taking-advantage-of-the-new-purple-book-patent-requirements-for-biologics

- The Patent Trap: The Struggle for Competition and Affordability in the Field of Biologic Drugs – Columbia Journal of Law & Social Problems, accessed August 18, 2025, https://jlsp.law.columbia.edu/wp-content/blogs.dir/213/files/2021/11/Vol.-54-Geaghan-Breiner.pdf

- Patenting – Drugs & Biologics – SC CTSI, accessed August 18, 2025, https://sc-ctsi.org/resources/regulatory-resources/drugs-biologics/patenting

- Commemorating the 15th Anniversary of the Biologics Price … – FDA, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/cder-conversations/commemorating-15th-anniversary-biologics-price-competition-and-innovation-act

- Predicting Patent Litigation Outcomes for Biosimilars: Navigating the Complex Landscape of Pharmaceutical Innovation for Biosimilars – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/predicting-patent-litigation-outcomes-for-biosimilars/

- Patents and Exclusivity | FDA, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/media/92548/download

- Blending Two Worlds: Small Molecule Drugs vs Biologics – Dotmatics, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.dotmatics.com/blog/blending-two-worlds-small-molecule-drugs-vs-biologics

- Patents to biological medicines in combination: is two really better than one?, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.penningtonslaw.com/news-publications/latest-news/2022/patents-to-biological-medicines-in-combination-is-two-really-better-than-one

- Is Patent “Evergreening” Restricting Access to Medicine/Device Combination Products?, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/is-patent-evergreening-restricting-access-to-medicine-device-combination-products/

- Patent “Evergreening” of Medicine–Device Combination Products: A Global Perspective – PMC – PubMed Central, accessed August 18, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9764446/

- Patent Protection Strategies: Safeguarding Your Innovations in a Competitive World, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/patent-protection-strategies/

- Pharmaceutical Patent Litigation and the Emerging Biosimilars: A Conversation with Kevin M. Nelson, JD – PMC, accessed August 18, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5394541/

- Manufacturing Barriers to Biologics Competition and Innovation – Iowa Law Review, accessed August 18, 2025, https://ilr.law.uiowa.edu/sites/ilr.law.uiowa.edu/files/2022-10/Manufacturing%20Barriers%20to%20Biologics%20Competition%20and%20Innovation.pdf

- DOSE OF REALITY: NEW ANALYSIS UNDERSCORES HOW OFTEN BIG PHARMA’S PATENTS ARE UNRELATED TO CLINICAL INNOVATION – CSRxP, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.csrxp.org/dose-of-reality-new-analysis-underscores-how-often-big-pharmas-patents-are-unrelated-to-clinical-innovation/

- How Patent Thickets Constrain the US Biosimilars Market and Domestic Manufacturing – Matrix Global Advisors, accessed August 18, 2025, https://getmga.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/PatentThickets_May2021_FINAL.pdf

- Humira – I-MAK, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.i-mak.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/i-mak.humira.report.3.final-REVISED-2020-10-06.pdf

- Patent Settlements Are Necessary To Help Combat Patent Thickets, accessed August 18, 2025, https://accessiblemeds.org/resources/blog/patent-settlements-are-necessary-to-help-combat-patent-thickets/

- 7th Circuit Hears Oral Arguments in Humira “Patent Thicket” Antitrust Case, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.biosimilarsip.com/2021/04/15/7th-circuit-hears-oral-arguments-in-humira-patent-thicket-antitrust-case/

- Biological patent thickets and delayed access to biosimilars, an …, accessed August 18, 2025, https://academic.oup.com/jlb/article/9/2/lsac022/6680093

- Biologic Patent Thickets and Terminal Disclaimers – PMC, accessed August 18, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10722383/

- The Humira Case: Exploring the Blockbuster Ahead of United States Biosimilar Launch, accessed August 18, 2025, https://trinitylifesciences.com/blog/the-humira-case-exploring-the-blockbuster-ahead-of-united-states-biosimilar-launch/

- In the Thick(et) of It: Addressing Biologic Patent Thickets Using the Sham Exception to Noerr-Pennington, accessed August 18, 2025, https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/iplj/vol33/iss3/5/

- A New Antitrust Approach After Humira ‘Patent Thicket’ Ruling | ArentFox Schiff, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.afslaw.com/perspectives/news/a-new-antitrust-approach-after-humira-patent-thicket-ruling

- Conducting a Biopharmaceutical Freedom-to-Operate (FTO …, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/conducting-a-biopharmaceutical-freedom-to-operate-fto-analysis-strategies-for-efficient-and-robust-results/

- “The Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act 10–A Stocktaking” by Yaniv Heled – Texas A&M Law Scholarship, accessed August 18, 2025, https://scholarship.law.tamu.edu/journal-of-property-law/vol7/iss1/3/

- Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act of 2009 – Wikipedia, accessed August 18, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Biologics_Price_Competition_and_Innovation_Act_of_2009

- Biological Product Innovation and Competition – FDA, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/biosimilars/biological-product-innovation-and-competition

- Mastering BPCIA in Patent Litigation – Number Analytics, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.numberanalytics.com/blog/mastering-bpcIA-patent-litigation

- “SHALL”WE DANCE?INTERPRETING THE BPCIA’S PATENT PROVISIONS – Berkeley Technology Law Journal, accessed August 18, 2025, https://btlj.org/data/articles2016/vol31/31_ar/0659_0686_Tanaka_WEB.pdf

- What Is the Patent Dance? | Winston & Strawn Law Glossary …, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.winston.com/en/legal-glossary/patent-dance

- Patent Dance Insights: A Q&A on Reducing Legal Battles in the Biosimilar Landscape, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.centerforbiosimilars.com/view/patent-dance-insights-a-q-a-on-reducing-legal-battles-in-the-biosimilar-landscape

- Guide to the BPCIA’s Biosimilars Patent Dance – Big Molecule Watch, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.bigmoleculewatch.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2022/12/Patent-Dance-Guide-December-2022.pdf

- 5 Key Questions for Biosimilar Applicant’s to Consider – Fish & Richardson, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.fr.com/insights/thought-leadership/blogs/biosimilars-guide-bpcia-patent-dance-five-key-questions/

- Patent Thickets and Litigation Abuses Hinder all Biosimilars, accessed August 18, 2025, https://accessiblemeds.org/resources/press-releases/patent-thickets-and-litigation-abuses-hinder-all-biosimilars/

- Navigating the Biosimilar Patent Landscape With Ha Kung Wong, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.centerforbiosimilars.com/view/navigating-the-biosimilar-patent-landscape-with-ha-kung-wong

- Freedom to Operate and Patent/Regulatory Exclusivity for Life Sciences – IPWatchdog.com, accessed August 18, 2025, https://ipwatchdog.com/2019/02/04/freedom-to-operate-interplay-patent-regulatory-exclusivity-life-sciences/id=105930/

- Current Trends In Biologics-Related Inter Partes Reviews | Steptoe, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.steptoe.com/en/news-publications/current-trends-in-biologics-related-inter-partes-reviews.html

- Disrupting the Balance: The Conflict Between Hatch-Waxman and Inter Partes Review, accessed August 18, 2025, https://jipel.law.nyu.edu/vol-6-no-1-2-shepherd/

- PTAB statistics show interesting trends for Orange Book and biologic patents in AIA proceedings | Mintz, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.mintz.com/insights-center/viewpoints/2231/2021-08-24-ptab-statistics-show-interesting-trends-orange-book-and

- Biologics at the PTAB: Statistics and Insights into Notable Biologics Decisions | Sterne Kessler, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.sternekessler.com/news-insights/insights/biologics-ptab-statistics-and-insights-notable-biologics-decisions/

- Addressing Patent Challenges in Biologics and Biosimilars – PatentPC, accessed August 18, 2025, https://patentpc.com/blog/addressing-patent-challenges-biologics-and-biosimilars

- Strategies for effective biosimilar clinical trial design and execution – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/strategies-for-effective-biosimilar-clinical-trial-design-and-execution/

- Key design considerations on comparative clinical efficacy studies for biosimilars: adalimumab as an example | RMD Open, accessed August 18, 2025, https://rmdopen.bmj.com/content/2/1/e000154