Introduction: The High-Stakes World of Pharmaceutical Exclusivity

The true market life of a pharmaceutical product is not defined by a single date on a calendar but by a complex, overlapping, and fiercely contested timeline. This timeline is governed by two distinct yet intertwined systems of market protection: patents granted by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) and regulatory exclusivities granted by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA).1 Understanding how to navigate this labyrinth of intellectual property and regulatory law is a critical function for any stakeholder in the pharmaceutical ecosystem, from innovator companies seeking to maximize their return on investment to generic and biosimilar manufacturers aiming to bring affordable alternatives to market.

At the heart of this landscape lies a fundamental tension: the need to incentivize costly and high-risk innovation through temporary monopolies versus the societal imperative to promote public access to affordable medicines through competition.2 This conflict is the primary driver behind the intricate legislative frameworks, such as the Hatch-Waxman Act and the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA), and the sophisticated strategic gamesmanship that defines the industry. The entire system is designed to balance these competing interests, creating a dynamic where brand-name companies build legal fortresses to protect their assets while challengers systematically seek to dismantle them.3

This dynamic is most dramatically illustrated by the phenomenon known as the “patent cliff”—the sharp and often catastrophic decline in revenue a company experiences when a blockbuster drug loses market exclusivity.7 The scale of this recurring event is staggering, with an estimated $200 billion to $300 billion in annual branded drug sales at risk globally between 2023 and 2030 as approximately 190 drugs, including 69 blockbusters, lose their protection.7 This immense financial pressure serves as the primary catalyst for both the defensive lifecycle management strategies employed by innovators and the market-entry tactics pursued by challengers.

This report provides a comprehensive strategic guide to understanding and managing these overlapping exclusivities. It will deconstruct the dual pillars of market protection, detail the data sources and analytical workflows required to map the exclusivity landscape, and explore the strategic frameworks governing market challenges and defenses. Through an examination of advanced case studies and emerging trends, this analysis will equip industry professionals with the nuanced understanding required to navigate the high-stakes world of pharmaceutical exclusivity.

Section 1: The Dual Pillars of Pharmaceutical Market Protection

A drug’s period of market monopoly is not a monolith. It is a composite shield built from two distinct materials: patents and regulatory exclusivities. These protections are granted by different government agencies (USPTO and FDA, respectively), are governed by separate statutes, and can run concurrently, creating a layered and often complex timeline of market protection.1 A comprehensive strategy requires a deep understanding of both.

1.1. The Patent Estate: Building a Legal Fortress with the USPTO

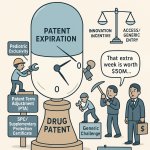

A patent is a powerful form of intellectual property that grants an inventor exclusive rights to an invention for a limited time, typically 20 years from the patent application’s filing date.12 In the pharmaceutical context, a patent does not grant the right to market a drug—that is the FDA’s purview—but rather the right to

exclude others from making, using, selling, or importing the patented invention.13 To be granted by the USPTO, an invention must meet three core criteria: it must be novel, useful, and non-obvious.1

Innovator companies strategically build a “patent estate” around a successful drug, which is composed of various types of patents filed at different times. This estate can be broadly categorized into primary and secondary patents.

- Base/Primary Patents: These are the foundational patents, typically filed early in the drug development process. They cover the core active pharmaceutical ingredient (API)—the molecule or biologic itself—and are considered the most valuable as they provide the broadest protection.13

- Secondary/Follow-on Patents: As a drug moves through its lifecycle, companies file numerous secondary patents on incremental innovations. These can cover new formulations, methods of use for new diseases, different dosage forms, or manufacturing processes.1 While these patents are often weaker and more susceptible to legal challenges, they play a crucial role in extending a drug’s commercial life beyond the expiration of the primary patent.15 A single drug can be protected by a portfolio of more than 100 patents.1

The strategic layering of different patent types is what creates a “patent thicket”—a dense, overlapping web of intellectual property designed to deter competition. The key types of patents that form the bricks of this fortress are detailed in Table 1.

The strategic value of a patent thicket is not merely additive; its effect on a potential challenger is exponential. It fundamentally shifts the competitive battleground from a straightforward legal dispute over the validity of a single, strong core patent to a protracted war of attrition over dozens, or even hundreds, of often weaker secondary patents. A generic challenger might possess a strong legal argument to invalidate a drug’s primary compound patent. In a one-on-one legal fight, the challenger might have a high probability of success. However, the innovator company has not relied on a single line of defense. It has proactively filed additional patents covering the drug’s extended-release formulation, its method of use for three distinct medical indications, and two different crystalline structures of the active molecule.13

The challenger is no longer facing a single lawsuit but a barrage of five or more. The cost of litigation multiplies alarmingly; challenging just one patent can cost a generic company as much as $1 million.19 The prospect of litigating a thicket of over 100 patents, a documented reality for some drugs, becomes financially untenable for all but the largest challengers.1 Even if the challenger succeeds in invalidating the first few patents, the innovator can employ a strategy of “serial litigation,” suing on the next patent in the thicket as soon as the previous case is resolved.17 This transforms the challenger’s core strategic question from a legal one (“Can we win the case?”) to a financial one (“Can we afford to keep fighting?”). In this way, a large number of weaker, follow-on patents become a powerful economic weapon, deterring challenges and forcing competitors into settlements on terms that are highly favorable to the innovator, often irrespective of the individual patents’ legal merits.15

Table 1: Comparison of Pharmaceutical Patent Types and Strategic Value

| Patent Type | What It Protects | Typical Filing Stage | Strategic Purpose | Example |

| Composition of Matter / Compound | The chemical structure of the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) itself. 13 | Early R&D, pre-clinical. | Core Protection. The “gold standard” of patents, providing the broadest and strongest defense against competitors. 16 | A patent on the novel molecule sildenafil. |

| Formulation | The specific combination of the API with other ingredients (excipients), or the drug’s delivery system. 12 | Mid-to-late lifecycle. | Lifecycle Extension. Improves patient compliance or drug performance (e.g., reduced dosing frequency). Defends against generics by creating a new, improved version. 13 | A once-weekly, sustained-release formulation of fluoxetine (Prozac). 18 |

| Method of Use | A specific application of a drug, such as treating a particular disease (a new indication) or a specific dosing regimen. 12 | Can be filed anytime a new use is discovered. | Drug Repurposing & Lifecycle Extension. Expands the market for an existing drug and creates new layers of exclusivity. 20 | A patent on using finasteride (originally for prostate issues) to treat male pattern baldness. |

| Process | The specific method or steps used to manufacture the drug substance or drug product. 12 | Concurrent with manufacturing development. | Manufacturing Control. Can prevent competitors from using a more efficient or cost-effective manufacturing process. | A novel, high-yield synthesis pathway for a complex molecule. |

| Polymorph / Enantiomer | Different crystalline structures (polymorphs) or stereoisomers (enantiomers) of the same API. 13 | Mid-to-late lifecycle. | Lifecycle Extension (“Chiral Switch”). A single, more effective enantiomer of a previously approved racemic mixture can be patented as a new invention. 18 | Esomeprazole (Nexium) as the single S-enantiomer of the racemic drug omeprazole (Prilosec). 9 |

| Combination | A therapy that combines two or more active ingredients into a single product. 12 | Varies; often used for complex diseases. | Synergistic Therapy Protection. Protects innovative treatments that rely on combining multiple drugs for enhanced efficacy. | A fixed-dose combination pill for treating HIV containing multiple antiretroviral drugs. 12 |

1.2. The Regulatory Shield: Carving out Exclusivity with the FDA

Operating in parallel to the patent system is a regime of regulatory exclusivity, a protection granted directly by the FDA upon a drug’s approval.1 This protection is not a property right but a statutory prohibition that prevents the FDA from approving certain competitor applications for a defined period, regardless of patent status.1 This system is unique to the pharmaceutical industry and was designed to provide specific incentives for innovation in areas of public health need.22

Regulatory exclusivities serve as both a strategic backstop and a powerful amplifier of market protection. They are not merely parallel tracks to patents; their interaction with the patent system creates a more resilient and often longer-lasting shield against competition. Consider a scenario where a company launches a new drug. Its core compound patent, filed early in a lengthy development process, may have only eight years of life remaining upon FDA approval.2 If this were the only protection, generic competition could begin in eight years.

However, if the drug is a New Chemical Entity (NCE), it automatically receives five years of NCE exclusivity from the FDA.22 This exclusivity is a powerful backstop. Under the Hatch-Waxman Act, a generic competitor cannot even

submit an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) containing a Paragraph IV patent challenge until four years after the brand drug’s approval (the “NCE-1” date).24 The earliest a patent infringement lawsuit can begin is at this four-year mark. If a suit is filed, it triggers an automatic 30-month stay on FDA approval of the generic. Therefore, the earliest a generic could possibly launch is four years (to file the ANDA) plus 30 months (the litigation stay), which equals 6.5 years post-approval. The five-year NCE exclusivity has effectively guaranteed a minimum 6.5-year market life, acting as a crucial backstop to the patent that was set to expire at year eight.

This effect can be amplified further. If this same NCE drug were also designated as a Qualified Infectious Disease Product (QIDP) under the GAIN Act, its five-year NCE exclusivity would be extended by an additional five years, for a total of 10 years.26 Now, the generic competitor cannot file its patent challenge until year nine (the NCE-1 date becomes 10 years minus one). The earliest possible generic approval is now pushed to nine years plus the 30-month stay, totaling 11.5 years. If the company also secures a six-month Pediatric Exclusivity, this is added on top of all existing patents and exclusivities, pushing the timeline out even further. This demonstrates that analyzing patent expiration dates in isolation is a fundamental strategic error. The strategic stacking of regulatory exclusivities can fundamentally reshape the competitive timeline, often extending a drug’s monopoly far beyond what patent data alone would suggest.

The various types of regulatory exclusivities are detailed in Table 2.

Table 2: Comprehensive Guide to FDA Regulatory Exclusivities

| Exclusivity Type | Governing Act | Duration | What It Blocks | Key Requirements & Notes | Stacking Potential |

| New Chemical Entity (NCE) | Hatch-Waxman Act | 5 Years | Blocks FDA submission of an ANDA/505(b)(2) for 4 years; blocks approval for 5 years. 22 | Granted to drugs containing an active moiety never before approved by the FDA. 23 | Can be extended by GAIN and/or Pediatric Exclusivity. 26 |

| New Clinical Investigation | Hatch-Waxman Act | 3 Years | Blocks FDA approval of an ANDA/505(b)(2) for the protected change. | For new uses/formulations of a previously approved drug, requiring new, essential clinical studies. 22 | Can be extended by GAIN and/or Pediatric Exclusivity. 26 |

| Orphan Drug (ODE) | Orphan Drug Act | 7 Years | Blocks FDA approval of another application (brand or generic) for the same drug for the same orphan indication. 22 | For drugs treating a rare disease affecting <200,000 people in the U.S. 10 | Can be extended by GAIN and/or Pediatric Exclusivity. 26 |

| Pediatric (PED) | Best Pharmaceuticals for Children Act (BPCA) | 6 Months | Adds 6 months of market protection to all existing patents and exclusivities for that active moiety held by the sponsor. 11 | Granted upon completion of pediatric studies requested by the FDA in a Written Request. 30 | Adds to other exclusivities; does not stand alone. |

| GAIN | Generating Antibiotic Incentives Now Act | 5 Years | Adds 5 years to any qualifying NCE, 3-Year, or Orphan Drug exclusivity. 11 | For drugs designated as a Qualified Infectious Disease Product (QIDP) to treat serious or life-threatening infections. 26 | Adds to other exclusivities; does not stand alone. |

| 180-Day Generic Drug | Hatch-Waxman Act | 180 Days | Blocks FDA approval of subsequent ANDAs for the same drug. | Awarded to the first generic applicant(s) to file a substantially complete ANDA with a Paragraph IV patent challenge. 5 | An incentive for generics; does not apply to brand drugs. |

| Reference Product (Biologic) | BPCIA | 12 Years | Blocks FDA submission of a biosimilar application for 4 years; blocks approval for 12 years from first licensure. 34 | Granted to a novel biologic product upon its first approval. | Can be extended by Pediatric Exclusivity. 35 |

| Competitive Generic Therapy (CGT) | FDA Reauthorization Act of 2017 | 180 Days | Blocks FDA approval of subsequent ANDAs for the same drug. | For drugs with inadequate generic competition; may overlap with 180-day patent challenge exclusivity in limited circumstances. 27 | An incentive for generics; does not apply to brand drugs. |

Section 2: The Data Nexus: Deciphering the Orange Book and Beyond

To effectively manage the overlap of patents and exclusivities, stakeholders must move beyond conceptual understanding to practical data analysis. The primary tool for this is the FDA’s “Orange Book,” the public repository where the worlds of patent law and drug regulation officially intersect. However, a complete strategic picture often requires supplementing this public data with specialized commercial intelligence.

2.1. Anatomy of the Orange Book: The Public Ledger of Exclusivity

The FDA’s publication, Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations, commonly known as the Orange Book, is the definitive public resource for information on drug approvals, patents, and exclusivities.37 Established in the wake of the Hatch-Waxman Amendments, its purpose is to provide a transparent registry linking approved drug products to the patents that brand-name sponsors claim cover their products, as well as any FDA-granted regulatory exclusivities.3 It is the central public ledger that underpins the entire framework of generic drug competition in the United States.40

For analytical purposes, the most valuable part of the Orange Book is its downloadable data files, which are typically provided as text or CSV files. The key files for exclusivity analysis are products, patents, and exclusivity.41

- products.txt / products.csv: This file contains product-level information, linking a drug’s trade name and active ingredient to its unique application number (Appl_No). Key fields include Trade_Name, Applicant, Strength, Dosage_Form, and the RLD (Reference Listed Drug) designation, which identifies the innovator product that generics must reference.41

- patents.txt / patents.csv: This is the core file for patent analysis. It lists every patent that an innovator has submitted to the FDA for a given product. The critical data fields for strategic analysis are:

- Appl_No and Product_No: These link the patent back to a specific drug product.

- Patent_No: The unique identifier for the patent.

- Patent_Expire_Date: The date the patent’s term ends, including any extensions. This is a primary data point for any loss-of-exclusivity (LOE) forecast.

- Drug_Substance_Flag and Drug_Product_Flag: These “Y” or “null” flags indicate whether the patent claims to cover the active ingredient itself or the formulated drug product (e.g., a tablet or capsule). This helps in assessing the breadth of patent protection.

- Patent_Use_Code: A specific code (e.g., U-123) that corresponds to a particular FDA-approved method of use or indication. This is one of the most strategically important fields, as it defines the scope of method-of-use patents and opens the door for generic “carve-out” strategies.41

- exclusivity.txt / exclusivity.csv: This file explicitly lists all FDA-granted regulatory exclusivities for a product. Its key fields are:

- Appl_No and Product_No: Links the exclusivity to a specific drug.

- Exclusivity_Code: A code that identifies the type of exclusivity (e.g., NCE, ODE, PED, GAIN).

- Exclusivity_Date: The date on which the regulatory protection expires.41

The Orange Book is not a static library of information; it is a dynamic battlefield where companies send clear strategic signals to their competitors. The act of listing a patent, particularly a secondary patent for a new formulation or method of use, is a public declaration of the innovator’s intent to defend that aspect of their product franchise. It puts the entire generic industry on notice that any attempt to copy that feature will trigger litigation. The choice of a Patent_Use_Code is an equally critical strategic move. An innovator might list a patent with a very broad use code in an attempt to block all generic entry. Conversely, they might list a patent tied to a very narrow indication.

This signaling actively shapes the strategic calculus of potential challengers. A generic company analyzing the Orange Book might see a dense thicket of patents and conclude that a full-frontal patent challenge is too costly and risky. However, upon closer inspection of the Patent_Use_Code data, they might identify a narrow method-of-use patent covering only a specific orphan indication. This discovery opens a strategic door: the generic can design its product and label to explicitly “carve out” the patented use, thereby seeking approval for the drug’s other, non-patented indications and avoiding infringement altogether.27 In this context, the data within the Orange Book is not merely descriptive; it is prescriptive, actively guiding the litigation, settlement, and market entry strategies of all players in the industry.

2.2. Translating Data into Intelligence: A Practical Workflow

A systematic approach is required to translate the raw data from the Orange Book into a coherent and actionable exclusivity timeline.

- Step 1: Identify the Target Product. Begin by identifying the brand-name drug of interest and locate it in the products file to obtain its New Drug Application number (Appl_No). This drug will be designated as the Reference Listed Drug (RLD).

- Step 2: Map the Patent Estate. Using the Appl_No, filter the patents file to extract all patents listed against the RLD. The primary data points are the Patent_No and, most importantly, the Patent_Expire_Date. These dates should be plotted on a timeline to create an initial map of the patent protection.

- Step 3: Decode the Patent Claims. For each patent on the timeline, analyze the Drug_Substance_Flag, Drug_Product_Flag, and Patent_Use_Code fields. This step provides crucial context. A patent flagged as covering the drug substance is generally stronger than one covering only a specific formulation. The Patent_Use_Code is essential for identifying potential “carve-out” opportunities, where a generic can avoid infringement by omitting a patented indication from its label.27

- Step 4: Map the Regulatory Shield. Using the same Appl_No, filter the exclusivity file to identify all granted regulatory exclusivities. Extract the Exclusivity_Code and Exclusivity_Date for each. Add these protection periods to the timeline created in Step 2.

- Step 5: Synthesize and Identify the Final Hurdle. The combined timeline now shows all overlapping patent and regulatory protections. The latest date on this timeline—whether from a patent or an exclusivity period—represents the final barrier to entry. This is the date a generic or biosimilar competitor could potentially launch without successfully challenging any patents. Any entry before this date requires navigating the litigation pathways defined by Hatch-Waxman or the BPCIA.

2.3. Beyond the Orange Book: Commercial Intelligence Platforms

While the Orange Book is the foundational source of public data, it has significant limitations for comprehensive competitive intelligence. It does not contain information on international patent filings, the status of ongoing patent litigation, details of settlement agreements, or data on drugs in the clinical trial pipeline.40

To fill these critical information gaps, the industry relies on specialized commercial intelligence services like DrugPatentWatch, Clarivate, IQVIA, and others.43 These platforms integrate Orange Book data with a wealth of other information sources, providing a much deeper and more dynamic view of the competitive landscape. Their services include:

- Litigation Tracking: Monitoring Paragraph IV patent challenges, court filings, and settlement agreements to anticipate the possibility of early generic entry.43

- Global Patent Data: Providing information on patent filings and status in jurisdictions outside the U.S., which is essential for global market strategy.43

- Pipeline and Clinical Trial Analysis: Tracking investigational drugs in development to identify future competitive threats or potential licensing opportunities.43

- API and Supplier Information: Identifying manufacturers of active pharmaceutical ingredients and finished drug products, which is crucial for supply chain and manufacturing strategy.43

- Automated Alerts and Forecasting: Providing customized alerts for key events like patent expirations or new litigation, and offering tools to forecast future revenue events and market shifts.46

By leveraging these services, companies can move from a static analysis of public data to a proactive, real-time strategy that accounts for the full spectrum of legal, regulatory, and commercial variables influencing a drug’s exclusivity.

Section 3: Strategic Navigation for Market Challengers (Generics & Biosimilars)

For companies seeking to market generic or biosimilar versions of innovator drugs, the landscape of patents and exclusivities is not a shield but a series of obstacles to be overcome. The U.S. has established two distinct and highly structured legal frameworks to govern these challenges: the Hatch-Waxman Act for small-molecule drugs and the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA) for biologics.

3.1. The Hatch-Waxman Gauntlet: Challenging Small-Molecule Patents

The Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984, or the Hatch-Waxman Act, revolutionized the pharmaceutical industry by creating a streamlined pathway for generic drug approval.3 It allows a generic manufacturer to file an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA), which relies on the FDA’s previous finding of safety and effectiveness for the innovator’s brand-name drug (the RLD). The generic company must primarily demonstrate that its product is bioequivalent to the RLD.1

A critical component of the ANDA process is the requirement for the generic applicant to address every patent listed in the Orange Book for the RLD. This is done via one of four patent certifications.5 The most strategically important of these is the Paragraph IV (PIV) certification.

A PIV certification is a declaration by the generic applicant that, in its opinion, the innovator’s patent is invalid, unenforceable, or will not be infringed by the generic product.52 This filing is considered an “artificial act of infringement” under U.S. law, a legal construct that allows patent litigation to commence before the generic drug is actually launched, providing a structured forum to resolve disputes pre-market.54 The PIV pathway is the most common and aggressive route for early generic entry.51

The PIV process follows a strict, time-sensitive sequence of events:

- ANDA Submission with PIV Certification: The generic company files its ANDA with the FDA, including a PIV certification against one or more of the RLD’s listed patents.

- Paragraph IV Notice Letter: Once the FDA acknowledges that the ANDA is sufficiently complete for review, the generic applicant has 20 days to send a formal notice letter to the brand-name drug sponsor and the patent owner. This letter must provide a detailed statement explaining the factual and legal basis for the PIV certification.5

- The 45-Day Window to Sue: Upon receiving the notice letter, the brand-name company has a 45-day window to file a patent infringement lawsuit against the generic applicant.5

- The Automatic 30-Month Stay: If the brand company files suit within this 45-day period, it triggers an automatic 30-month stay of FDA approval for the ANDA. During this stay, the FDA generally cannot grant final approval to the generic application, unless the court case is resolved in the generic’s favor sooner. This provision gives the innovator a significant period of guaranteed market protection while the patent dispute is litigated.5

To incentivize generics to undertake the risk and expense of patent litigation, the Hatch-Waxman Act includes a powerful reward: 180-day marketing exclusivity. The first generic applicant (or applicants, if multiple file on the same day) to submit a “substantially complete” ANDA with a PIV certification is generally eligible for this 180-day period of exclusivity.5 During these six months, the FDA will not approve any other ANDAs for the same drug. This effectively creates a duopoly between the brand-name drug and the first generic, allowing the generic to capture significant market share at a price point that is typically only moderately discounted from the brand price.7 This 180-day period is often the most profitable phase of a generic drug’s lifecycle and is the ultimate prize in the PIV challenge process.

The 180-day exclusivity incentive creates a frantic, high-stakes race among generic companies to be the “first-to-file” a PIV challenge. This race often culminates on a specific, predetermined date, such as the “NCE-1” date, which is four years after the approval of a brand-name drug that was a New Chemical Entity.51 The decision to invest millions of dollars in developing a generic product and preparing for litigation is a significant gamble, one that is often made with incomplete information about the innovator’s full defensive strategy.

At the time of filing, the generic company has meticulously analyzed the patents listed in the FDA’s Orange Book. However, this public data represents only what the innovator has chosen to disclose. The generic filer does not know the full strength of the brand’s litigation team, whether the innovator holds unlisted patents (such as those covering manufacturing processes, which are not listed in the Orange Book), or what other lifecycle management strategies the brand may deploy in response to the challenge. For example, the brand may be secretly preparing to launch its own “authorized generic” to disrupt the 180-day exclusivity period, or it may be planning to switch the market to a new, patent-protected formulation of the drug (“product hopping”). The generic company is therefore making a multi-million-dollar bet on its ability to win the patent litigation and secure the lucrative 180-day prize, without knowing the full hand of its opponent. This fundamental information asymmetry defines the high-risk, high-reward nature of the PIV challenge and is a central feature of the competitive dynamics in the small-molecule drug market.

3.2. The BPCIA “Patent Dance”: A Different Choreography for Biosimilars

The approval pathway for biosimilars—products that are “highly similar” to an existing, FDA-approved biologic reference product—is governed by the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA) of 2010.34 While the BPCIA’s goal of fostering competition is similar to that of Hatch-Waxman, its mechanism for resolving patent disputes is markedly different. Instead of the confrontational PIV process, the BPCIA outlines a highly structured, multi-step information exchange colloquially known as the “patent dance”.57

The patent dance is designed to facilitate the early identification and narrowing of patent disputes before full-blown litigation begins. The key steps and timelines include 57:

- Initial Disclosure: Within 20 days of the FDA accepting its abbreviated Biologics License Application (aBLA), the biosimilar applicant may provide a copy of its aBLA and information about its manufacturing process to the reference product sponsor (RPS).

- RPS Patent List: The RPS then has 60 days to provide the applicant with a list of all patents it believes could reasonably be asserted against the biosimilar product.

- Applicant’s Response: The applicant has 60 days to respond with its own list of patents it believes are relevant and must provide a detailed statement explaining, on a claim-by-claim basis, why each of the RPS’s patents is invalid, unenforceable, or not infringed.

- RPS’s Counter-Response: The RPS then has 60 days to provide its own detailed rebuttal, explaining why its patents are valid and would be infringed.

- Negotiation: Following this exchange, the parties have 15 days to negotiate in good faith to agree upon a final list of patents that will be litigated in the first wave of litigation.

- First Wave of Litigation: If an agreement is reached, the RPS must bring an infringement action within 30 days on the agreed-upon patents. If no agreement is reached, the parties exchange lists of patents they intend to litigate, and the RPS must sue within 30 days.

A crucial feature of this framework is its optionality. In the landmark case Sandoz v. Amgen, the Supreme Court held that the patent dance is not mandatory; a biosimilar applicant cannot be forced to participate.60 This creates a critical early strategic decision for the biosimilar developer.

- Consequences of Engaging in the Dance: By participating, the biosimilar applicant gains a degree of control over the timing and scope of the initial litigation. It allows both parties to see each other’s positions and potentially narrow the dispute, which could lead to more efficient resolution.

- Consequences of Opting Out: If a biosimilar applicant chooses to forgo the dance, it loses the ability to shape the initial phase of the conflict. The decision of when and which patents to litigate shifts entirely to the RPS, who can immediately file a patent infringement suit on any patent it believes is relevant.58 This can lead to broader, more unpredictable, and potentially more costly litigation for the biosimilar applicant.

The strategic choice of whether to “dance” is a complex one, weighing the benefits of a structured, predictable process against the potential tactical advantages of forcing the innovator’s hand in open court without a formal prelude.

Table 4: Comparative Overview: Hatch-Waxman P-IV vs. BPCIA Patent Dance

| Feature | Hatch-Waxman (PIV Challenge) | BPCIA (Patent Dance) | Strategic Implication |

| Governing Act | Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984 | Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act of 2010 | Different legal frameworks for small molecules vs. biologics. |

| Triggering Event | Filing of an ANDA with a Paragraph IV certification. 54 | Filing of an aBLA; applicant may choose to initiate the dance. 57 | The PIV challenge is inherently confrontational; the patent dance is an optional, structured negotiation. |

| Information Exchange | A one-way “Notice Letter” from the generic to the brand detailing the basis of the challenge. 5 | A multi-step, reciprocal exchange of patent lists and detailed legal arguments between the applicant and sponsor. 57 | The dance is designed for transparency and narrowing disputes pre-litigation; the PIV process moves directly to a potential lawsuit. |

| Automatic Stay | A 30-month automatic stay on FDA approval is triggered if the brand sues within 45 days of notice. 5 | No automatic stay of FDA approval. Litigation proceeds on its own timeline. | The 30-month stay is a powerful defensive tool for brand-name small-molecule drugs that does not exist for biologics. |

| Exclusivity Incentive | 180 days of marketing exclusivity for the first successful PIV challenger. 51 | No equivalent 180-day exclusivity for the first biosimilar challenger. | The 180-day prize creates a powerful “race-to-file” dynamic for generics that is absent in the biosimilar space. |

| Optionality | The PIV certification is the required pathway for a pre-expiration patent challenge. | The entire patent dance process is optional for the biosimilar applicant. 58 | Biosimilar applicants have a key strategic choice at the outset: engage in the structured dance or proceed directly to potential litigation. |

Section 4: Lifecycle Management and Defense for Innovators

For innovator companies, the period of market exclusivity is a finite and precious resource. The immense pressure of the looming patent cliff compels them to develop and execute sophisticated strategies aimed at defending their key products and extending their commercial lifespan for as long as possible. These strategies are not limited to legal patent filings but often involve a coordinated campaign across regulatory, legal, and commercial domains.

4.1. Fortifying the Fortress: “Evergreening” and the Patent Thicket

The most common and controversial set of lifecycle management strategies revolves around the concepts of “evergreening” and the “patent thicket.”

- Evergreening: This is the practice of systematically filing for and obtaining new, secondary patents on an existing drug to extend its period of monopoly protection.13 These secondary patents typically cover incremental modifications rather than true breakthrough inventions. Common evergreening techniques include patenting:

- New formulations (e.g., an extended-release version that allows for less frequent dosing).13

- New methods of use (i.e., discovering the drug is effective for a different disease).13

- New delivery methods (e.g., a nasal spray version of a drug previously available as a pill).18

- Specific isomers or polymorphs of the original active ingredient.13

The practice is highly contentious. Proponents, typically innovator companies, argue that evergreening represents legitimate, ongoing R&D that leads to tangible patient benefits, such as improved safety, efficacy, or convenience, and that this continued investment deserves patent protection.61 Critics, including generic manufacturers and healthcare advocates, contend that it is a strategic abuse of the patent system designed to block competition, maintain high prices, and reward trivial tweaks that offer little to no therapeutic advantage over the original product.15

- The Patent Thicket: Evergreening is the process by which a patent thicket is cultivated. As discussed previously, a patent thicket is a dense and overlapping web of patents surrounding a single product.13 The strategic goal is to create a legal and financial minefield that is so complex and costly for a potential challenger to navigate that it deters them from even attempting to enter the market, or at least forces them into a favorable settlement.17

4.2. Case Study: The Humira® (adalimumab) Patent Thicket

AbbVie’s defense of its blockbuster biologic, Humira, is the quintessential case study of the patent thicket strategy in action. Humira, used to treat a range of autoimmune diseases, was one of the best-selling drugs in history, and AbbVie employed an unprecedented patenting strategy to protect its revenue stream.

- The Scale of the Thicket: AbbVie constructed a massive patent estate around Humira, accumulating approximately 136 patents.17 The original patent on the Humira molecule was set to expire in 2016 in the U.S., but this dense thicket of secondary patents extended protection for years beyond that date.

- The Nature of the Patents: The vast majority of these were not foundational patents on the drug itself. Peer-reviewed research found that around 80% of the patents in the Humira estate were duplicative or covered incremental changes, such as manufacturing processes or formulations.17

- The Strategic Outcome: Potential biosimilar competitors, despite having products ready for market, were faced with the daunting prospect of fighting AbbVie on 136 different patent fronts. The risk of engaging in years of “prohibitively expensive” and “serial” litigation—where winning one case might simply lead to being sued on the next patent—was immense.17 This overwhelming legal leverage effectively forced every major biosimilar challenger into settlement agreements. These settlements allowed biosimilar entry to begin in the U.S. in 2023. While this was years after the primary patent expired, it was a full 11 years

before the last patents in the thicket were set to expire, demonstrating both the power of the thicket to delay competition and the role of settlements in eventually breaking the logjam.17

4.3. Case Study: The Revlimid® (lenalidomide) Multi-Pronged Defense

The defense of the cancer drug Revlimid by Celgene (later acquired by Bristol Myers Squibb) represents an even more sophisticated, multi-domain approach to lifecycle management, going beyond a simple patent thicket.

- The Patent Thicket: The foundation of the strategy was a formidable patent thicket. Celgene/BMS filed at least 206 patent applications related to Revlimid, with 117 being granted in the U.S. This created a significant legal barrier to entry long after the primary patent on the active ingredient expired in 2019.19

- Weaponizing a Regulatory Requirement (REMS): Revlimid is associated with a risk of severe birth defects, and as a condition of its approval, the FDA required a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) program to ensure its safe use. This program, called RevAssist, tightly controlled the drug’s distribution.63 Celgene strategically weaponized this safety requirement as a commercial barrier. It used the REMS program to refuse to sell samples of Revlimid to generic manufacturers. Without these samples, the generic companies could not conduct the bioequivalence studies required by the FDA for ANDA approval. This tactic was used to block or delay at least 14 different generic manufacturers and became the subject of a congressional investigation and antitrust lawsuits.63

- Leveraging Regulatory Exclusivities: Celgene also pursued and obtained multiple orphan drug designations for Revlimid for various rare cancer indications. Each of these designations carried the potential for a seven-year period of orphan drug exclusivity, adding further layers of non-patent protection.63

- Strategic, Volume-Limited Settlements: The combined pressure of the massive patent thicket and the REMS-based sample blockade created overwhelming leverage for Celgene. This forced generic challengers into highly strategic settlement agreements. Instead of a simple entry date, the settlements were structured to allow for a slow, controlled erosion of Revlimid’s market share. Generic entry was permitted to begin in March 2022, but on a strictly volume-limited basis. The initial generic volume was capped at a mid-single-digit percentage of the total market. These volume restrictions will remain in place, gradually easing over time, until January 31, 2026, when unlimited generic competition is finally permitted.19

The most successful innovator defense strategies, as exemplified by the Revlimid case, are not merely about filing patents. They are proactive, integrated campaigns waged across legal, regulatory, and commercial fronts. A defense strategy based purely on patents, like the Humira model, relies on the sheer number and complexity of the IP. The Revlimid strategy demonstrates a more sophisticated approach. Celgene did not just build a patent thicket.19 It ingeniously leveraged a mandatory FDA

regulatory requirement—the REMS program—as a physical and commercial barrier, preventing competitors from obtaining the materials needed to even begin the generic approval process.63 This was a powerful, non-patent-based delay tactic. Simultaneously, the company pursued multiple

regulatory exclusivities by securing orphan drug designations for new indications, each adding another potential layer of protection.63 Finally, it used the combined pressure from the patent litigation risk and the REMS blockade to force competitors into highly favorable

commercial agreements. These settlements controlled not just the date of generic entry, but the very volume of competition for several years, transforming a sharp patent cliff into a gentle, managed decline.64 This case illustrates that managing exclusivity overlaps at the highest level requires a masterful understanding of how to use every available tool—patent law, FDA regulations, and commercial negotiation—in a coordinated, multi-domain strategy to protect a valuable franchise.

Section 5: The Overlap Zone: Advanced Analysis and Antitrust Considerations

The true complexity of pharmaceutical exclusivity management lies in the overlap zone, where different patents and regulatory protections interact, stack, and create market dynamics that are not apparent from analyzing any single protection in isolation. This section synthesizes the previous concepts to explore these interactions, their financial consequences, and the legal guardrails designed to prevent anticompetitive behavior.

5.1. Stacking and Concurrence: How Overlaps Create Extended Protection

The additive power of certain regulatory exclusivities can dramatically extend a drug’s monopoly period beyond what NCE or orphan drug status alone would provide. The GAIN Act and the Pediatric Exclusivity provision are the most powerful “stacking” mechanisms.

- Pediatric Exclusivity (PED) as a Universal Extender: The six-month pediatric exclusivity is uniquely powerful because it attaches to the end of all existing patent and regulatory exclusivity periods for a given active moiety held by that sponsor.11 It is a universal amplifier of market protection. When it is granted, the FDA’s Orange Book will show each relevant patent listed twice: once with its original expiration date, and a second time with the six-month extension.11

- GAIN Exclusivity as a Major Extension: The five-year GAIN exclusivity for Qualified Infectious Disease Products (QIDPs) is added directly to certain other exclusivities, creating substantial extensions.26

The combination of these stacking provisions can lead to very long periods of market protection, as illustrated by the scenarios in Table 3.

The interplay between a dense patent thicket and the 30-month litigation stay creates a period of “shadow exclusivity” that can extend a drug’s market protection well beyond its formal patent or regulatory expiration dates. This de facto extension is not an official exclusivity granted by the FDA but is a direct and powerful consequence of the strategic use of the litigation framework established by the Hatch-Waxman Act.

Consider a drug whose five-year NCE exclusivity has expired and whose last meaningful patent is set to expire at year 12 post-approval. On paper, the market should open to generic competition at year 12. However, the innovator has built a thicket of 50 patents, with some secondary patents not expiring until year 18. A generic company files a PIV challenge at year four, as early as the NCE exclusivity allows. The brand-name company responds by suing on a handful of its earliest-expiring patents, which triggers the 30-month stay, blocking FDA approval until at least 6.5 years post-approval.5

The litigation over this first wave of patents can take several years to resolve. As that litigation concludes, the innovator can engage in “serial litigation” by suing the generic challenger again, this time on a different set of patents from its thicket.17 While a 30-month stay is generally triggered only by litigation on newly listed patents, the sheer cost and time required for the generic to fight its way through the entire 50-patent thicket effectively blocks market entry. The challenger faces the prospect of winning one lawsuit only to be immediately faced with another, a process that could go on for years and cost tens of millions of dollars. The result is a period of continued market protection for the innovator—for example, from year 12 (the end of the original key patent) to year 16 (when a settlement is finally reached)—that is not a formal, FDA-granted exclusivity but a “shadow exclusivity” created by the innovator’s strategic exploitation of the litigation system. This is a crucial, non-obvious layer of protection that can only be understood by analyzing the interaction between a company’s patent strategy and the mechanics of the Hatch-Waxman framework.

Table 3: Exclusivity Stacking Scenarios

| Base Exclusivity | Added Exclusivity (GAIN) | Added Exclusivity (PED) | Total Exclusivity Period | Earliest PIV Filing Date (NCE-1) |

| NCE (5 years) | N/A | N/A | 5 years | 4 years post-approval |

| NCE (5 years) | + 5 years | N/A | 10 years | 9 years post-approval |

| NCE (5 years) | + 5 years | + 6 months | 10.5 years | 9 years post-approval |

| Orphan Drug (7 years) | N/A | N/A | 7 years | N/A (ODE blocks approval, not submission) |

| Orphan Drug (7 years) | + 5 years | N/A | 12 years | N/A |

| Orphan Drug (7 years) | + 5 years | + 6 months | 12.5 years | N/A |

5.2. The Financial Stakes: Navigating the Patent Cliff

The “patent cliff” is the term used to describe the dramatic and often immediate loss of revenue that an innovator company experiences when one of its blockbuster drugs loses market exclusivity.7 This is not a gradual decline; it is common for a drug to lose 80-90% of its revenue within the first year of generic competition.7

- Economic Impact: The financial consequences are immense. The pharmaceutical industry is projected to face the loss of over $200 billion in annual revenue from drugs going off-patent between 2025 and 2030.8 For an individual company heavily reliant on a single product, such a loss can be an existential threat, leading to significant drops in overall profitability and forcing cuts in R&D spending for future innovation.66 For example, when Pfizer’s cholesterol drug Lipitor lost exclusivity, its U.S. sales were predicted to fall by 87% in the following year.9

- Price Erosion: The entry of generic competitors leads to intense price competition and significant price reductions. Studies have shown that drug prices can fall to as low as 6.6% of their pre-expiry price within a few years of generic entry, although the extent of the reduction varies significantly by country and by product.9

5.3. The Post-Actavis World: Antitrust Scrutiny of Settlements

Given the high financial stakes, brand and generic companies often choose to settle patent litigation rather than fight it to a conclusion. However, the nature of these settlements has come under intense antitrust scrutiny. A particularly controversial practice is the “reverse payment” or “pay-for-delay” settlement, in which the brand-name patent holder pays the generic challenger to drop its patent challenge and agree to delay its market entry.68 Regulators argue that such payments are a way for the brand to share its monopoly profits with a potential competitor to the detriment of consumers, who are denied earlier access to lower-cost medicines.

This issue came to a head in the 2013 Supreme Court case FTC v. Actavis, Inc..

- The Supreme Court’s Ruling: The Court rejected a simple, bright-line rule for these settlements. It ruled that they are not presumptively illegal, but they are also not immune from antitrust scrutiny simply because they occur within the scope of a patent’s life. Instead, the Court held that reverse payment settlements must be evaluated under the antitrust “rule of reason”.69 A payment from the brand to the generic that is “large and unexplained” can be evidence of an illegal agreement to restrain trade.70

- The Aftermath and Lingering Uncertainty: The Actavis decision left it to the lower courts to structure and apply the rule of reason analysis, a task they have struggled with, leading to inconsistent application and significant legal uncertainty.70 A key area of debate has been the definition of a “payment.” Courts have expanded the concept beyond simple cash transfers to include other forms of value, such as a brand’s promise not to launch its own “authorized generic” (a “no-AG” agreement), which would compete with the settling generic’s product.70 The legal landscape for patent settlements remains complex and fraught with risk, requiring careful navigation to avoid antitrust liability.

Section 6: The Future Landscape: Emerging Technologies and Global Perspectives

The strategic landscape of pharmaceutical exclusivity is not static. It is continuously being reshaped by technological advancements, particularly in artificial intelligence, and by the diverse legal and regulatory environments of the global market.

6.1. The Rise of AI in Patent Intelligence and Drug Discovery

Artificial intelligence is rapidly transforming the pharmaceutical industry, from early-stage research to competitive intelligence. AI algorithms can analyze massive biological and chemical datasets to accelerate drug discovery, significantly shortening the traditional 10-15 year development timeline and reducing the immense costs, which can exceed $2 billion per drug.72

- AI’s Role in R&D: AI is being used for target identification (pinpointing disease-related proteins or genes), de novo molecule design (creating novel drug structures), and optimizing clinical trials (predicting patient responses and reducing costs).72

- AI’s Role in Patent Intelligence: Commercial platforms are now using AI to automate and enhance patent analysis. AI agents can conduct prior art searches in seconds, help draft patent applications, and monitor global patent filings and litigation trends in real time, providing a significant competitive advantage.74

While AI offers tremendous potential, it also introduces novel and complex legal challenges for patenting the resulting inventions.

- The Human Inventorship Requirement: A fundamental principle of U.S. patent law is that an inventor must be a human being. An AI system cannot be listed as an inventor on a patent. This was affirmed in the case Thaler v. Vidal.72

- The “Significant Contribution” Test: For an AI-assisted invention to be patentable, a human must have made a “significant contribution” to the invention’s conception. The USPTO has issued guidance advising that this determination should be made using the Pannu factors, which are traditionally used to assess joint inventorship.75 Under this test, a human’s contribution must be more than simply prompting an AI with a problem; it requires substantive input, such as designing the AI model, creatively selecting the training data, conducting experiments to validate or modify the AI’s output, or using the AI’s results to make a further inventive leap.72

The strategic implication for companies is clear: those using AI in their R&D must meticulously document the specific, significant contributions of their human researchers throughout the inventive process to ensure they can secure valid patent protection for their discoveries.

The rise of AI is poised to exacerbate the problem of the patent thicket. While AI can accelerate the discovery of breakthrough drugs, it can also be used to rapidly and cheaply generate thousands of potential minor modifications, alternative formulations, and new uses for an existing drug. This will make it significantly easier and less expensive for innovator companies to build even denser and more complex patent thickets than those seen today.

Currently, creating and testing a new drug formulation or identifying a new therapeutic use requires substantial human effort and expensive laboratory work, which places a practical limit on the number of secondary patents an innovator can pursue.18 AI, however, can computationally generate thousands of viable alternative formulations or predict novel biological targets for an existing molecule in a fraction of the time and at a fraction of the cost.72 An innovator could leverage these AI-generated outputs to file a vast number of provisional patent applications, creating an immense, computationally-derived patent thicket. While each of these patent applications would still need to meet the legal standards of novelty, non-obviousness, and significant human contribution, the sheer volume of AI-generated starting points would dramatically lower the cost and effort required to construct the thicket. This means that in the future, a market challenger may not be facing a thicket of 136 patents, as was the case with Humira, but potentially a thicket of thousands. This would make the litigation pathway even more economically unfeasible for challengers, further entrenching the market power of the innovator’s intellectual property position.

6.2. A Global Lens: Key Differences in International Patent Law

There is no such thing as a “global patent.” Patent rights are territorial, meaning protection must be sought and obtained in each individual country or region where a company wishes to have a monopoly.76 While many core principles are shared, there are significant differences in patent law and practice around the world that impact pharmaceutical strategy.

- United States vs. Europe: These are the two largest markets, and their systems have key distinctions.

- United States: The U.S. system is characterized by its unique dual structure of USPTO-granted patents and a robust system of FDA-granted regulatory exclusivities.1 U.S. patent law has also been complicated by Supreme Court decisions, such as

Mayo v. Prometheus, which have made it more difficult to patent inventions related to diagnostic methods and natural laws.77 - Europe: The European Patent Office (EPO) provides a centralized examination process. A key feature of European patent law is its stronger emphasis on ethical considerations, which are codified in the Biotechnology Directive. This directive explicitly prohibits the patenting of certain inventions, such as processes for cloning human beings, on moral grounds.77

- Other Key Jurisdictions:

- India: India is known for its very strict approach to secondary patents. Section 3(d) of the Indian Patent Act prevents the patenting of new forms of a known substance unless the new form demonstrates a significant enhancement in therapeutic efficacy. This provision makes evergreening strategies much more difficult to execute in India than in the U.S. or Europe.77

- Japan: The Japan Patent Office (JPO) is known for its rigorous and detailed examination process, which requires comprehensive descriptions and a high standard for inventive step.76

A successful global pharmaceutical strategy requires a tailored approach to intellectual property, one that recognizes and adapts to the unique legal requirements, policy priorities, and enforcement environments of each major market.

Conclusion & Strategic Recommendations

The market exclusivity of a pharmaceutical product is not a simple 20-year term but a dynamic and contested lifespan shaped by the complex interplay of a multi-layered patent estate and a parallel system of FDA-granted regulatory protections. The immense financial pressure of the patent cliff has driven both innovators and challengers to develop sophisticated strategies to defend franchises and create market opportunities. Success in this high-stakes environment depends on treating exclusivity management not as a perfunctory legal function but as a core pillar of competitive strategy, grounded in deep, data-driven analysis.

Based on the analysis in this report, the following strategic recommendations are offered:

For Innovator Companies:

- Embrace Proactive and Multi-Domain Lifecycle Management: The defense of a blockbuster drug cannot begin when generic challengers appear. It must be a proactive strategy initiated early in the product’s life. This involves not only building a strong base patent but also systematically creating a layered patent thicket with a diverse portfolio of secondary patents covering formulations, methods of use, and delivery systems.

- Leverage Every Available Exclusivity: Innovators must actively pursue all available regulatory exclusivities. This includes designing clinical trial programs to potentially qualify for 3-year new clinical investigation exclusivity, seeking orphan drug designations where applicable, and conducting requested pediatric studies to gain the uniquely powerful six-month pediatric extension. For qualifying products, GAIN exclusivity should be a primary goal, as it can double the length of other key exclusivities.

- Integrate Legal, Regulatory, and Commercial Strategy: The most effective defense strategies, as demonstrated by the Revlimid case, are those that coordinate actions across multiple domains. Legal strategy (building the patent thicket) should be used to create leverage for commercial strategy (negotiating favorable, volume-limited settlements). Regulatory requirements, such as REMS programs, should be analyzed for their potential to create additional, non-patent-based hurdles for competitors.

For Challenger Companies (Generics & Biosimilars):

- Conduct Deep Due Diligence Beyond Patent Dates: A simple analysis of patent expiration dates from the Orange Book is insufficient and can be dangerously misleading. Challengers must conduct a thorough analysis of all listed patents, paying close attention to patent use codes to identify potential “carve-out” opportunities. Furthermore, they must map all applicable regulatory exclusivities and their stacked expiration dates to determine the true earliest possible date for market entry.

- Engage in Strategic Target Selection: Not all drugs are created equal from a challenge perspective. Challengers should prioritize targeting products with weaker or less dense patent thickets. Commercial intelligence platforms should be used to track the litigation history of specific patents and the success rates of challenges against particular innovator companies to inform a risk-benefit analysis.

- Make Calculated, Informed Risks: The 180-day generic exclusivity remains the most powerful incentive for patent challenges. Challengers must understand the high-stakes nature of the “first-to-file” race and be prepared for aggressive and costly litigation. For biosimilar developers, the decision of whether to engage in the BPCIA patent dance is a critical strategic choice that must be weighed carefully, balancing the benefits of a structured negotiation against the potential advantages of a more direct legal confrontation.

In the final analysis, the pharmaceutical exclusivity landscape will only grow more complex with the advent of new technologies like AI and the increasing globalization of the market. The organizations that thrive will be those that possess a deep, nuanced, and data-driven understanding of this labyrinth and can adeptly use its rules to their strategic advantage.

Works cited

- Pharmaceutical Patent Regulation in the United States – The Actuary Magazine, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.theactuarymagazine.org/pharmaceutical-patent-regulation-in-the-united-states/

- Determinants of Market Exclusivity for Prescription Drugs in the United States – Commonwealth Fund, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/journal-article/2017/sep/determinants-market-exclusivity-prescription-drugs-united

- 40th Anniversary of the Generic Drug Approval Pathway | FDA, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/cder-conversations/40th-anniversary-generic-drug-approval-pathway

- Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act – Wikipedia, accessed August 7, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Drug_Price_Competition_and_Patent_Term_Restoration_Act

- What Every Pharma Executive Needs to Know About Paragraph IV …, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/what-every-pharma-executive-needs-to-know-about-paragraph-iv-challenges/

- What is Hatch-Waxman? – PhRMA, accessed August 7, 2025, https://phrma.org/resources/what-is-hatch-waxman

- The Tipping Point: Navigating the Financial and Strategic Impact of …, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-impact-of-patent-expiry-on-drug-prices-a-systematic-literature-review/

- The End of Exclusivity: Navigating the Drug Patent Cliff for Competitive Advantage, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-impact-of-drug-patent-expiration-financial-implications-lifecycle-strategies-and-market-transformations/

- Evolving Pharmaceutical Strategies in a Post-Blockbuster World: Navigating Innovation, Access, and Market Dynamics – Drug Patent Watch, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/evolving-pharmaceutical-strategies-in-a-post-blockbuster-world/

- Understanding Market Exclusivity for Orphan Drug Products – Cytel, accessed August 7, 2025, https://cytel.com/perspectives/understanding-market-exclusivity-for-orphan-drug-products/

- Frequently Asked Questions on Patents and Exclusivity – FDA, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/development-approval-process-drugs/frequently-asked-questions-patents-and-exclusivity

- What are the types of pharmaceutical patents? – Patsnap Synapse, accessed August 7, 2025, https://synapse.patsnap.com/blog/what-are-the-types-of-pharmaceutical-patents

- Filing Strategies for Maximizing Pharma Patents: A Comprehensive …, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/filing-strategies-for-maximizing-pharma-patents/

- The Basics of Drug Patents – Alliance for Health Policy, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.allhealthpolicy.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Krishtel.Slides-AHP-DrugPatentWebinar-051619.pdf

- Chemical patent – Wikipedia, accessed August 7, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chemical_patent

- Types of Pharmaceutical Patents – O’Brien Patents, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.obrienpatents.com/types-pharmaceutical-patents/

- Patent Settlements Are Necessary To Help Combat Patent Thickets …, accessed August 7, 2025, https://accessiblemeds.org/resources/blog/patent-settlements-are-necessary-to-help-combat-patent-thickets/

- Patent protection strategies – PMC, accessed August 7, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3146086/

- How Celgene and Bristol Myers Squibb Used Volume Restrictions to Delay Revlimid Competition – I-MAK, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.i-mak.org/2025/04/04/how-celgene-and-bristol-myers-squibb-used-volume-restrictions-to-delay-revlimid-competition/

- The value of method of use patent claims in protecting your therapeutic assets, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-value-of-method-of-use-patent-claims-in-protecting-your-therapeutic-assets/

- A Quick Guide to Pharmaceutical Patents and Their Types – PatSeer, accessed August 7, 2025, https://patseer.com/a-quick-guide-to-pharmaceutical-patents-and-their-types/

- Patents and Exclusivities for Generic Drug Products – FDA, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/cder-conversations/patents-and-exclusivities-generic-drug-products

- Small Business Assistance: Frequently Asked Questions for New Drug Product Exclusivity, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/cder-small-business-industry-assistance-sbia/small-business-assistance-frequently-asked-questions-new-drug-product-exclusivity

- Regulatory Exclusivity for Novel Drugs and Biologics – Mayer Brown, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.mayerbrown.com/-/media/files/perspectives-events/events/2023/02/fda-lifecycle-management-webinar-regulatory-exclusivity-for-novel-drugs-and-biologics.pdf%3Frev=-1

- FDA Is Evolving on Qualifications for ‘New Chemical Entity’ | Troutman Pepper Locke, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.troutman.com/insights/fda-is-evolving-on-qualifications-for-new-chemical-entity.html

- Time to GAIN: Are Your FDA Marketing Exclusivities Eligible for …, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.finnegan.com/en/insights/articles/time-to-gain-are-your-fda-marketing-exclusivities-eligible-for-extension.html

- Exclusivity–Which one is for me? | FDA, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/media/135234/download

- FDA Regulatory Exclusivities Guide – Number Analytics, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.numberanalytics.com/blog/fda-regulatory-exclusivities-guide

- Rare Diseases at FDA, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/patients/rare-diseases-fda

- Qualifying for Pediatric Exclusivity Under Section 505A of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act – FDA, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/development-resources/qualifying-pediatric-exclusivity-under-section-505a-federal-food-drug-and-cosmetic-act-frequently

- New FDA pediatric draft guidances include proposal that could limit pediatric exclusivity grants – Hogan Lovells, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.hoganlovells.com/en/publications/new-fda-pediatric-draft-guidances-include-proposal-that-could-limit-pediatric-exclusivity-grants

- GAIN: How a New Law is Stimulating the Development of Antibiotics | The Pew Charitable Trusts, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.pew.org/en/research-and-analysis/issue-briefs/2013/11/07/gain-how-a-new-law-is-stimulating-the-development-of-antibiotics

- GENERATING ANTIBIOTIC INCENTIVES NOW – FDA, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/files/about%20fda/published/Report-to-Congress-on-Generating-Antibiotic-Incentives-Now-%28GAIN%29.pdf

- Commemorating the 15th Anniversary of the Biologics Price … – FDA, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/cder-conversations/commemorating-15th-anniversary-biologics-price-competition-and-innovation-act

- Pediatric Studies of Biologics – Safe and Effective Medicines for Children – NCBI Bookshelf, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK202045/

- Guidance for Industry: Competitive Generic Therapies – FDA, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/media/136063/download

- Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations | Orange Book – FDA, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-approvals-and-databases/approved-drug-products-therapeutic-equivalence-evaluations-orange-book

- Orange Book Preface – FDA, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/development-approval-process-drugs/orange-book-preface

- Freshly Squeezed: Orange Book History and Key Updates at 45, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.fdli.org/2025/05/freshly-squeezed-orange-book-history-and-key-updates-at-45/

- Patent Use Codes for Pharmaceutical Products: A Comprehensive Analysis for Strategic Advantage – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/patent-use-codes-for-pharmaceutical-products-a-comprehensive-analysis/

- Orange Book Data Files | FDA, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-approvals-and-databases/orange-book-data-files

- FDA Orange Book Drug Data – Kaggle, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/thedevastator/fda-orange-book-drug-data

- DrugPatentWatch | Software Reviews & Alternatives – Crozdesk, accessed August 7, 2025, https://crozdesk.com/software/drugpatentwatch

- Drugs to Watch Report | Clarivate, accessed August 7, 2025, https://clarivate.com/drugs-to-watch/

- What are the top Biopharmaceutical Business Intelligence Services? – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/what-are-the-top-biopharmaceutical-business-intelligence-services/

- Real-Time Patent Intelligence: Unlock Pharma Market Opportunities – Arctic Invent, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.arcticinvent.com/technologies/drug-patent-watch

- Our search for a reliable patent intelligence solution ended with …, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/

- DrugPatentWatch 2025 Company Profile: Valuation, Funding & Investors | PitchBook, accessed August 7, 2025, https://pitchbook.com/profiles/company/519079-87

- www.fda.gov, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/abbreviated-new-drug-application-anda/hatch-waxman-letters#:~:text=The%20%22Drug%20Price%20Competition%20and,Drug%2C%20and%20Cosmetic%20Act%20(FD%26C

- The timing of 30‐month stay expirations and generic entry: A cohort study of first generics, 2013–2020, accessed August 7, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8504843/

- Paragraph IV Explained – ParagraphFour.com, accessed August 7, 2025, https://paragraphfour.com/paragraph-iv-explained/

- Mastering Paragraph IV Certification – Number Analytics, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.numberanalytics.com/blog/mastering-paragraph-iv-certification

- Patent Certifications and Suitability Petitions – FDA, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/abbreviated-new-drug-application-anda/patent-certifications-and-suitability-petitions

- Tips For Drafting Paragraph IV Notice Letters | Crowell & Moring LLP, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.crowell.com/a/web/v44TR8jyG1KCHtJ5Xyv4CK/tips-for-drafting-paragraph-iv-notice-letters.pdf

- Hatch-Waxman Act – Practical Law, accessed August 7, 2025, https://uk.practicallaw.thomsonreuters.com/Glossary/PracticalLaw/I2e45aeaf642211e38578f7ccc38dcbee

- Orange Book Exclusivity: Part III – 180-Day and Competitive Generic Therapy Exclusivities, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=S-8mXTOp6kM

- Biosimilar Patent Dance: Leveraging PTAB Challenges for Strategic Advantage, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/biosimilar-patent-dance-leveraging-ptab-challenges-for-strategic-advantage/

- What Is the Patent Dance? | Winston & Strawn Law Glossary …, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.winston.com/en/legal-glossary/patent-dance

- Guide to the BPCIA’s Biosimilars Patent Dance – Big Molecule Watch, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.bigmoleculewatch.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2022/12/Patent-Dance-Guide-December-2022.pdf

- 5 Key Questions for Biosimilar Applicant’s to Consider – Fish & Richardson, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.fr.com/insights/thought-leadership/blogs/biosimilars-guide-bpcia-patent-dance-five-key-questions/

- Drug patents: the evergreening problem – PMC, accessed August 7, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3680578/

- Patent Database Exposes Pharma’s Pricey “Evergreen” Strategy – UC Law SF, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.uclawsf.edu/2020/09/24/patent-drug-database/

- Congressional Investigation of RevAssist-Linked and General …, accessed August 7, 2025, https://ascopubs.org/doi/10.1200/OP.23.00579

- Bristol Myers Squibb Announces Settlement of U.S. Patent Litigation for REVLIMID® (lenalidomide) With Dr. Reddy’s, accessed August 7, 2025, https://news.bms.com/news/details/2020/Bristol-Myers-Squibb-Announces-Settlement-of-U.S.-Patent-Litigation-for-REVLIMID-lenalidomide-With-Dr.-Reddys/default.aspx

- Celgene’s New Revlimid® Lawsuits Shows Shifting Tactics From Earlier Natco Case, accessed August 7, 2025, https://ipwatchdog.com/2017/11/21/celgenes-new-revlimid-lawsuits-shows-shifting-tactics/id=90357/

- The Role of Assets In Place: Loss of Market Exclusivity and Investment, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w27588/w27588.pdf

- The Impact of Patent Expiry on Drug Prices: A Systematic Literature Review – PMC, accessed August 7, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6132437/

- FTC v. ACTAVIS: The Patent-Antitrust Intersection Revisited – Texas A&M Law Scholarship, accessed August 7, 2025, https://scholarship.law.tamu.edu/facscholar/508/

- FTC v. Actavis Inc. | Oyez, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.oyez.org/cases/2012/12-416

- A Decade of FTC v. Actavis: The Reverse Payment Framework Is …, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/publications/antitrust/journal/86/issue-2/decade-of-ftc-v-actavis.pdf

- A Decade of FTC v. Actavis: The Reverse Payment Framework Is Older, but Are Courts Wiser in Applying It | White & Case LLP, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.whitecase.com/insight-our-thinking/decade-ftc-v-actavis-reverse-payment-framework-older-are-courts-wiser-applying

- Patenting Drugs Developed with Artificial Intelligence: Navigating …, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/patenting-drugs-developed-with-artificial-intelligence-navigating-the-legal-landscape/

- Artificial Intelligence in Pharmaceutical Technology and Drug Delivery Design – PMC, accessed August 7, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10385763/

- Patsnap | AI-powered IP and R&D Intelligence, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.patsnap.com/

- Patentability Risks Posed by AI in Drug Discovery | Insights – Ropes & Gray LLP, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.ropesgray.com/en/insights/alerts/2024/10/patentability-risks-posed-by-ai-in-drug-discovery

- How International Patent Laws Differ: A Comparative Study – PatentPC, accessed August 7, 2025, https://patentpc.com/blog/how-international-patent-laws-differ-a-comparative-study

- Biotech Patent Protection: US vs Europe vs Asia Key Differences, accessed August 7, 2025, https://synapse.patsnap.com/article/biotech-patent-protection-us-vs-europe-vs-asia-key-differences