Introduction: The Allure of Simplicity in a World of Complexity

In the high-stakes world of pharmaceutical research and development, information is the most valuable currency. The journey from a promising molecule to a blockbuster drug is a marathon paved with billions of dollars, fraught with scientific uncertainty, and, most critically, governed by a labyrinthine landscape of intellectual property. Every decision—from which research path to pursue, to when to challenge a competitor, to the optimal timing for a generic launch—hinges on having a clear, accurate, and comprehensive understanding of the patent ecosystem. A single misstep, a single overlooked patent, can lead to catastrophic financial losses, decade-long legal battles, or the complete derailment of a promising therapeutic program.

Why Drug Patent Searching is a High-Stakes Game

Let’s be clear: we’re not talking about a casual search for a new gadget. Pharmaceutical patent searching is a different beast entirely. The claims in a drug patent aren’t just protecting a physical invention; they’re defining a legal monopoly over chemical structures, manufacturing processes, methods of use, and formulations that can be worth tens of billions of dollars over the life of the patent.

Consider the stakes. The average cost to develop a new drug has been estimated to be over $2.6 billion [1]. This colossal investment is only justifiable if the resulting product is protected by a robust patent portfolio, granting a period of market exclusivity to recoup costs and generate profit. For a generic or biosimilar manufacturer, the game is one of precision timing. Launching a product too early—infringing on a valid patent—can result in treble damages and crippling injunctions. Launching too late means surrendering hundreds of millions in revenue to competitors who got their timing right. For the innovator, the challenge is to build an IP fortress, ensuring no gaps in coverage that a competitor could exploit.

This isn’t just a legal exercise; it’s the strategic bedrock of the entire industry. It dictates M&A activity, licensing deals, R&D budgets, and ultimately, shareholder value. In this context, the quality of your patent intelligence isn’t just a detail; it’s the difference between market leadership and market exit.

The Promise of Google Patents: A Democratizing Force?

Into this high-stakes arena steps Google Patents. Launched in 2006, it was a revelation. Suddenly, a vast, global repository of patent documents was available to anyone with an internet connection—for free. The interface was familiar, the search bar was inviting, and the promise was intoxicating: the democratization of patent information. No longer was patent searching the exclusive domain of highly paid specialists in wood-paneled law firms. A scientist in a startup, a business development manager in a mid-sized pharma company, or even an academic researcher could now, in theory, access the same documents as a patent attorney at a Big Pharma giant.

Google Patents offers an undeniable value proposition. It provides keyword searching across millions of documents from over 100 patent offices, often with machine-translated versions of foreign documents and links to prior art cited by examiners. For a quick, preliminary search, for finding a specific patent number you already have, or for general educational purposes, it is an incredible resource. It has lowered the barrier to entry for basic patent awareness, and for that, it should be commended.

The Core Thesis: When “Good Enough” is Dangerously Insufficient

Herein lies the danger. The very ease and accessibility of Google Patents can lull users into a false sense of security. It makes the monumentally complex task of pharmaceutical patent searching feel simple. And in the pharmaceutical industry, feeling simple is often a prelude to being wrong. Relying solely on a generalist search engine for a specialist’s task is akin to using a consumer-grade GPS for navigating a naval minefield. While it might get you through calm, open waters, it lacks the specific, critical data layers needed to detect the hidden dangers that can sink your entire enterprise.

This article is not an indictment of Google Patents as a tool. It is a critical examination of its limitations in the specific, high-stakes context of pharmaceutical strategy. We will dissect the hidden pitfalls—the data gaps, the search algorithm fallacies, the missing regulatory context, and the legal status black holes—that make it an inadequate standalone solution for any serious commercial decision-making in the pharma space. We will argue that for tasks like Freedom-to-Operate (FTO) analysis, patentability assessments, and competitive intelligence, “good enough” is a recipe for disaster. Your IP strategy, the very foundation of your company’s future, deserves more than a free search bar. It requires a professional, curated, and context-rich intelligence solution.

The Fundamental Disconnect: Understanding What Google Patents Is—and What It Isn’t

To understand the pitfalls of Google Patents, we must first grasp its fundamental nature. At its core, Google Patents is a search engine. It is a marvel of computer science, designed to crawl, index, and make searchable a colossal volume of publicly available data. Its primary function is text retrieval based on algorithms honed for web searching. This is its greatest strength and its most profound weakness.

A Search Engine, Not a Curated Database

Think of the difference between a vast, un-cataloged warehouse of books (Google Patents) and a specialized research library (a professional patent intelligence platform). In the warehouse, every book is technically there, somewhere. If you know the exact title and author, you can probably find it. But if you need to find every book on a specific, nuanced topic—say, “19th-century maritime trade law in Southeast Asia”—the warehouse attendant can only point you to the “L” section for law and the “H” section for history and wish you luck.

The research librarian, however, has not only cataloged the books but has also read them, understood their context, and created cross-references. They know that a key text on your topic is actually in the biography section, disguised as a sea captain’s memoir, and that a crucial legal precedent is discussed in a German-language journal of economics that you would have never thought to search. The librarian provides curation, context, and insight. The warehouse provides a pile.

The Algorithm’s Blind Spots: Keyword Ambiguity and Conceptual Gaps

Google’s algorithms are built on keyword matching and semantic associations derived from analyzing trillions of web pages. This works beautifully for general queries. But pharmaceutical patents are written in a dense, highly specific, and often deliberately obtuse language.

A keyword search for a drug’s common name, for instance, is tragically incomplete. A patent might refer to the compound only by its IUPAC chemical name, an internal company project code (e.g., “Compound AZ-123”), or as part of a broad chemical class. The algorithm, lacking a deep, built-in pharmaceutical ontology, cannot inherently know that “Paracetamol,” “Acetaminophen,” and “N-(4-hydroxyphenyl)acetamide” are the exact same active pharmaceutical ingredient (API). A human expert knows this instantly. A specialized database has this information hard-coded into its very structure. Google’s algorithm is left guessing based on co-occurrence in other documents, a method that is prone to error and omission.

The Lack of Pharmaceutical-Specific Ontologies

An ontology is a formal representation of knowledge, a map of concepts and their relationships. A pharmaceutical ontology would connect a drug’s brand name (e.g., Lipitor) to its generic name (atorvastatin), its chemical structure, its therapeutic class (statin), its mechanism of action (HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor), the diseases it treats (hypercholesterolemia), and the companies that hold patents on it.

Google Patents lacks this deep, structured, pharmaceutical-specific knowledge graph. It cannot, for example, allow you to search for “all patents related to oral dosage forms of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) that are set to expire in the next three years.” That query requires multiple layers of integrated data that a simple text index cannot provide. You can search for the words “oral dosage” and “SSRI,” but the results will be a noisy, incomplete list, missing patents that claim SSRIs without using that exact acronym or that cover oral formulations using different terminology. This is the difference between searching for data and querying for intelligence.

The Illusion of Global Coverage

Google boasts of including documents from over 100 patent offices, which sounds impressively comprehensive. However, the depth, timeliness, and quality of this coverage can be dangerously inconsistent.

The Patchwork of Data: Missing Jurisdictions and Publication Delays

While major patent offices like the USPTO (United States), EPO (Europe), and WIPO (International) are well-covered, the data from smaller but commercially significant jurisdictions can be sporadic or delayed. Important emerging markets like Brazil, India, or Mexico have complex national patent systems, and the data feeds available to a general-purpose crawler like Google may not be as timely or complete as those obtained through direct agreements by specialized providers.

For a generic company planning a global launch, a six-month delay in the publication of a granted patent in Brazil isn’t a minor inconvenience; it’s a critical intelligence failure that could lead to a mistaken market entry and subsequent infringement lawsuit. Professional platforms invest heavily in sourcing timely, reliable data directly from these national offices because their clients’ businesses depend on it.

The Problem with Machine Translations: Nuance Lost in Translation

A key feature of Google Patents is its on-the-fly machine translation of foreign documents. This is a fantastic tool for getting a quick “gist” of a patent in Japanese or German. However, patent law is a field where nuance is everything. The precise wording of a claim defines its legal scope, and machine translation is notoriously unreliable for capturing the subtle but critical distinctions in legal and technical language.

Consider a claim term like “substantially free of.” In a legal context, does “substantially” mean 95%, 99%, or 99.9%? The answer could be buried in the patent’s specification or in the case law of that specific country. A machine translation might render this term inconsistently or strip it of its legal meaning, leading a researcher to a completely flawed understanding of the patent’s scope. Relying on machine translation for anything more than a cursory overview is a form of intellectual property roulette.

The Static Snapshot: Where is the Legal Status and Litigation Data?

Perhaps the most significant disconnect is that a patent document is not a static piece of paper. It is a living legal right whose status changes over time. It can be challenged, invalidated, licensed, or allowed to expire. Google Patents primarily provides a snapshot of the patent as it was published. It does a poor job of tracking the dynamic lifecycle of a patent.

Is the patent still in force? Have the required maintenance fees been paid in Germany, France, and the UK? Was the patent challenged in a post-grant review at the USPTO? Is it currently the subject of a major lawsuit in the District of Delaware?

This information is the lifeblood of strategic decision-making, and it is largely absent from Google Patents. It exists in separate, disconnected databases: maintenance fee records at national patent offices, dockets from the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB), and federal court records. To a business strategist, a patent’s value is inextricably linked to its enforceability and legal history. By presenting the patent document in a vacuum, Google Patents provides the text without the context, the body without the pulse. Professional platforms invest immense resources in integrating these disparate datasets to provide a 360-degree view of a patent’s true, current legal and commercial standing.

Pitfall #1: The Peril of Incomplete or Lagging Data

In the world of pharmaceutical patents, what you don’t know can, and absolutely will, hurt you. The value of patent intelligence is directly proportional to its completeness and timeliness. An analysis based on an incomplete or outdated dataset is worse than no analysis at all, as it fosters a false confidence that can lead to disastrous strategic blunders. This is one of the most insidious pitfalls of relying solely on Google Patents.

The Black Hole of Pre-Grant Publications (PGPubs)

One of the fundamental principles of most modern patent systems is a period of secrecy. When a company files a patent application, it is not immediately made public. In the United States and many other jurisdictions, the application is typically published 18 months after its earliest priority filing date [2]. This 18-month period is a black hole for competitors. A company could have filed for a patent on a revolutionary new formulation for a blockbuster drug, and for a year and a half, the outside world remains completely unaware.

The 18-Month Secrecy Period: What You Can’t See Can Hurt You

This delay is a feature, not a bug, of the patent system, designed to give applicants time to evaluate their invention’s commercial potential before disclosing it publicly. But for a competitor, this creates a period of profound uncertainty. You might be investing hundreds of millions of dollars in a new R&D program, only to discover 18 months later that a rival company filed a patent application covering the same technology a year ago. You have just wasted immense resources pursuing a path that is now potentially blocked.

While no search tool can see into this 18-month black hole, the critical issue is how quickly and comprehensively patent applications are made available the moment they are published. This is where reliance on a general web crawler can be perilous.

Case Study: A Generic’s Nightmare Scenario

Imagine a generic drug manufacturer, “GenoPharm,” is planning to launch a generic version of a drug whose main compound patent is expiring. Their FTO analysis, conducted using Google Patents, shows a clear path to market. They invest $50 million in bioequivalence studies and manufacturing scale-up.

What they missed was a new patent application filed by the innovator, “OriginPharma,” 17 months prior, covering a new, more stable crystalline form of the drug. This application was published by the USPTO last Tuesday. However, Google’s indexing schedule, which is optimized for the web as a whole, hasn’t yet picked up and processed this brand-new Pre-Grant Publication (PGPub). GenoPharm’s searches, run on Monday, came up clean.

Three weeks later, after GenoPharm has publicly announced its launch plans, their legal team finally stumbles upon the published application. Panic ensues. Their entire launch strategy is now threatened by a new patent that could issue and block their product for years. Had they been using a professional intelligence service with direct, daily data feeds from the USPTO, they would have known about this blocking application the day it was published, saving them from public embarrassment and allowing them to pivot their strategy before committing further resources.

Data Ingestion Lags: When Real-Time Matters

The GenoPharm scenario highlights the critical issue of data lag. Google is a master of crawling the web, but the “web” is not the same as the primary, raw data feeds from the world’s patent offices. Professional patent databases often pay for direct, structured data feeds from sources like the USPTO, EPO, and WIPO. This allows them to update their databases daily, or even more frequently, with newly published applications and granted patents.

The Difference Between USPTO Direct Feeds and Google’s Indexing Schedule

The USPTO releases data on newly published applications and granted patents on specific days of the week. A professional service with a direct feed can parse, clean, and integrate this data into their searchable database within hours. Their clients can set up alerts and be notified of a competitor’s new patent publication the very same day.

Google Patents, on the other hand, crawls the public websites of these patent offices. While this crawling is frequent, it is not instantaneous and is subject to the priorities of Google’s global web-crawling infrastructure. A delay of a few days, or even a week, between official publication and indexation on Google Patents is not uncommon. In the fast-moving pharmaceutical sector, a week can be an eternity. It can be the difference between being the first to file a challenge against a competitor’s patent and being the second, or the difference between making a go/no-go decision with complete information versus partial information.

The Competitive Edge of Timeliness

Consider a scenario in business development. A mid-sized biotech company is in late-stage negotiations to be acquired by a Big Pharma company for $500 million. The deal hinges on the strength of the biotech’s IP portfolio. The day before the deal is set to be finalized, a key competitor publishes a patent application that could potentially block the biotech’s lead candidate.

The acquiring company, if it relies on a professional, real-time alert service, gets an email notification that morning. Their IP team immediately analyzes the new application and advises a pause on the acquisition to assess the new threat. The deal is renegotiated at a lower valuation, saving the acquirer hundreds of millions.

The biotech’s team, relying on periodic searches on Google Patents, is caught completely flat-footed. They don’t discover the publication for another week, by which time their negotiating leverage has vanished. Timeliness is not a luxury; it is a powerful competitive weapon.

The Murky Waters of International Data

The problem of data completeness and timeliness is magnified when dealing with international patent data. The promise of a single, unified global search bar is seductive, but the reality is far messier.

Challenges with Non-Latin Scripts and National Peculiarities

Many commercially important countries, such as China, Japan, South Korea, and Russia, use non-Latin scripts. While Google’s machine translation is helpful for a gist, searching in the original language is often essential for accuracy. Furthermore, the way data is structured and made available varies wildly from country to country. Some national patent offices have sophisticated online databases; others are less advanced.

Specialized platforms invest significant resources in normalizing this disparate global data. This involves not just translation, but transliteration of names, standardization of company assignees (e.g., ensuring “Bayer AG,” “Bayer,” and “Bayer Aktiengesellschaft” are all treated as the same entity), and understanding the unique legal and procedural rules of each jurisdiction. This painstaking data curation is largely invisible to the end-user but is absolutely essential for reliable international searching. A search on Google Patents might miss a key Chinese patent because the assignee’s name was translated slightly differently or because the specific database Google is crawling has a coverage gap for that particular year.

The WIPO PCT System vs. National Phase Entry: A Point of Confusion

The Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) system, administered by WIPO, allows an applicant to file a single “international” patent application and delay the decision of which countries to enter for up to 30 or 31 months [3]. Google Patents displays these PCT applications (published with a “WO” number). However, a PCT application is not a global patent; it is merely a placeholder. For it to become an enforceable right, the applicant must file a “national phase entry” in each individual country or region they desire.

This is a critical point of confusion. A user might see a PCT application on Google Patents and mistakenly assume it provides patent coverage in the United States, Europe, and Japan. In reality, the applicant may have only entered the national phase in Japan. The application is effectively dead in the US and Europe.

Conversely, and more dangerously, a user might not find a US patent via a keyword search but miss the fact that an English-language PCT application, which was designated for the US, exists. They might mistakenly believe the coast is clear. Tracking the family tree of a patent—from its initial priority filing, through the PCT stage, to its various national phase entries and granted patents—is a complex task. Google Patents provides links to “family members,” but the data can be incomplete or difficult to interpret. Professional platforms specialize in presenting this family information in a clear, legally meaningful way, allowing users to see at a glance exactly where a patent is active, pending, or abandoned. This curated view prevents dangerous misinterpretations about the geographic scope of a competitor’s rights.

Pitfall #2: The Deception of Keyword Searching in Pharma

At first glance, the search bar in Google Patents seems like a gateway to endless knowledge. Just type in the name of a drug, a target, or a technology, and the secrets of the pharmaceutical world will be revealed. This is a profound and dangerous misconception. In the specialized lexicon of patent law and medicinal chemistry, keyword searching is a blunt instrument, incapable of capturing the precision and complexity required for a meaningful search. It creates an illusion of comprehensiveness while leaving vast, critical gaps in its wake.

The Semantic Trap: Synonyms, Acronyms, and Project Codes

The language of drug development is a minefield of synonyms. A single compound is a chameleon, changing its name depending on the context. Let’s take the example of Pfizer’s blockbuster drug, sildenafil. A truly comprehensive search for patents related to this compound would need to include:

- Brand Name: Viagra, Revatio

- International Nonproprietary Name (INN): Sildenafil

- IUPAC Chemical Name: 1-[[3-(6,7-dihydro-1-methyl-7-oxo-3-propyl-1H-pyrazolo[4,3-d]pyrimidin-5-yl)-4-ethoxyphenyl]sulfonyl]-4-methylpiperazine

- Internal Company Code: UK-92,480

No single researcher, without specialized tools, can be expected to know and search for all these variations. A patent filed early in the development process might only refer to the compound as UK-92,480. A search for “sildenafil” or “Viagra” on Google Patents would completely miss this foundational document. The algorithm has no innate understanding that these disparate strings of text all refer to the same molecule.

The Art of “Code-Switching” in Scientific Language

Patent attorneys are masters of linguistic obfuscation. They often draft claims using broad, generic language to capture as wide a scope of protection as possible, while describing specific examples in the patent’s specification using different terminology. For example, the claims might refer to “an acidic proton donor,” while the examples specify “hydrochloric acid” or “citric acid.” A keyword search for “citric acid formulation” might miss the broader, more dominant patent entirely.

This isn’t just about simple synonyms. It’s about conceptual relationships. A patent might claim a “method of treating autoimmune disorders” but only provide examples for “rheumatoid arthritis” and “psoriasis.” A keyword search for “lupus,” another autoimmune disorder, would miss this patent, even though the patent’s claims could very well be interpreted by a court to cover the treatment of lupus. Specialized databases with curated thesauruses and concept mapping can bridge these semantic gaps, but a general keyword algorithm cannot.

The Markush Structure Conundrum

If keyword searching is a blunt instrument, then against the fortress of Markush claims, it is utterly useless. Markush structures are a unique and powerful feature of chemical and pharmaceutical patent claims, and they represent a complete dead-end for any search strategy based on text alone.

What is a Markush Claim? A Brief Primer

Imagine you’ve invented a new type of key. Instead of patenting just one specific key, you want to patent the concept of the key. You might claim: “A key comprising a head, a shaft, and a plurality of teeth, wherein the head is made of a material selected from the group consisting of brass, steel, and aluminum.”

This “selected from the group consisting of” language is the essence of a Markush claim. It allows a patent applicant to claim a whole family of related compounds in a single claim, even if they haven’t physically synthesized and tested every single one.

In a pharmaceutical patent, a Markush claim might look something like this (highly simplified):

“A compound of Formula I: R1-X-R2, wherein:

R1 is selected from the group consisting of methyl, ethyl, and propyl;

X is a linker selected from the group consisting of an amide and an ester; and

R2 is a cyclic moiety selected from the group consisting of phenyl, pyridyl, and thiophene.”

This single claim covers 3 x 2 x 3 = 18 different, distinct chemical compounds. A real-world Markush claim can cover billions or even trillions of potential compounds by defining multiple variable positions (R1, R2, R3, etc.) with long lists of possible chemical groups for each.

Why Keyword and Even Basic Chemical Structure Searches Fail

Now, try searching for one specific compound covered by that claim on Google Patents. Let’s say your company is developing “methyl-amide-phenyl.” You type that into the search bar. You get zero results. You conclude you are free to operate. You have just made a potentially billion-dollar mistake.

Your compound’s name doesn’t appear in the text of the patent. The patent doesn’t list out all 18 compounds it covers. It only provides the generic formula. Google’s text-based algorithm cannot read the chemical formula, understand the variables, and determine that your specific molecule is one of the 18 possibilities encompassed by the claim. It is conceptually impossible for a keyword search to solve this problem.

Even a simple chemical structure drawing tool that searches for exact matches would fail. Your specific structure isn’t drawn in the patent; only the generic “template” structure is.

The Need for Specialized Chemical Search Capabilities

To overcome this, you need highly specialized search platforms that allow for chemical substructure searching. These systems, often built around sophisticated chemical databases, allow a user to draw a molecule (or a piece of a molecule) and search for any patent that discloses a Markush structure that would encompass the drawn molecule. This is a computationally intensive task that requires a deep integration of chemical intelligence with patent data. It is the absolute standard for any serious FTO or patentability search in the chemical or pharmaceutical arts. Services like DrugPatentWatch and other professional platforms build their value on precisely these kinds of specialized search capabilities that are simply beyond the scope of a generalist tool like Google Patents.

“It is estimated that over 60% of all chemical patents contain Markush-type claims. For pharmaceutical patents, this figure is likely much higher. Ignoring Markush structures in a prior art or freedom-to-operate search is not just a tactical error; it is professional malpractice.”— Based on analysis from the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) and industry experts [4].

The Limitations of Google’s Classification Search (CPC/IPC)

To its credit, Google Patents does allow users to search and filter by patent classifications, such as the Cooperative Patent Classification (CPC) system used by the USPTO and EPO. This seems like a way to overcome the ambiguity of keywords. Instead of searching for words, you can search for patents classified under “A61K 31/40” (Medicinal preparations containing heterocyclic compounds having a five-membered ring with one nitrogen atom).

This is a step up from pure keyword searching, but it’s fraught with its own set of problems.

Broad Categories vs. Granular Therapeutic Areas

Patent classification systems are designed by patent offices for the purpose of assigning applications to examiners with the right technical background. They are not designed from the ground up to serve the needs of commercial or strategic analysis. As a result, the categories can be incredibly broad. The classification for a particular type of compound might contain thousands, or tens of thousands, of patents. Sifting through these results to find the relevant documents is an enormous task.

Furthermore, a single patent can be assigned multiple classifications, and the consistency of classification can vary between examiners and across different patent offices. You might find a key patent is classified in a way you wouldn’t expect, causing you to miss it if you rely solely on filtering by what you assume is the “correct” class.

The Human Element of Accurate Classification

The most sophisticated intelligence platforms don’t just rely on the classifications provided by the patent office. They employ teams of Ph.D. scientists and subject matter experts to apply their own, more granular and commercially relevant tagging and classification to patents. They can create custom taxonomies for “JAK inhibitors,” “antibody-drug conjugates,” or “mRNA delivery systems” that are far more precise and useful than the broad patent office categories.

This human-driven curation allows for searches that are simply impossible with standard classifications. It allows a user to find all patents related to a specific biological pathway, even if the patents themselves never use a consistent term for it. This layer of human intelligence, built on top of the raw patent data, is a crucial differentiator that generalist tools cannot replicate. Relying on the raw CPC codes provided in Google Patents is like navigating a city using only its zip codes; you know the general neighborhood, but you have no idea where the specific streets or points of interest are located.

Pitfall #3: The Missing Link – Integrating Regulatory and Commercial Data

A patent, in isolation, is a fascinating legal document. But to a business, its value is zero unless it is connected to a real-world product, a market, and a regulatory pathway. A patent is not a right to sell a drug; it is only the right to exclude others from selling it. The right to actually market and sell a drug comes from regulatory bodies like the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) or the European Medicines Agency (EMA).

This is arguably the single greatest weakness of using Google Patents for pharmaceutical strategy: it exists in a vacuum, completely disconnected from the regulatory and commercial data that gives a patent its context and value. Making strategic decisions without this integrated data is like trying to captain a ship by looking only at a map of the winds, with no knowledge of the currents, the tides, or the destination port.

A Patent is Not a Product: The Disconnect from FDA Data

When a pharmaceutical company gets a new drug approved, the FDA lists the approved product in a publication known as the “Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations,” more famously called the “Orange Book” [5]. For biologics, the equivalent is the “Purple Book” [6]. Critically, the innovator company must identify which of its patents it believes cover the approved drug. These patents are then listed in the Orange Book alongside the product.

This listing is the cornerstone of the entire brand-name vs. generic drug ecosystem in the United States. It puts the world on notice about which patents a generic company will have to challenge or design around to bring its version to market.

The Orange Book and Purple Book: The Real Gates to Market Entry

For a generic strategist, the Orange Book is the starting point for everything. It tells them which patents the innovator believes are relevant. The expiration dates of these listed patents often define the “patent cliff,” the moment when a blockbuster drug is expected to face generic competition and a massive drop in sales.

Google Patents has no link to the Orange Book. You can find a patent for atorvastatin on Google Patents, but you can’t see, on that same page, that it’s the key patent for Lipitor, that it’s listed in the Orange Book, when it’s set to expire, and what regulatory exclusivities might also be in play. You are looking at a single puzzle piece with no view of the final picture.

Why Linking Patents to Approved Drugs is a Non-Trivial Task

Creating this link is a complex, manual, and expert-driven process. There is no simple database field that says “Patent ‘123 is for Drug XYZ.” It requires experts to read the patent claims, understand the approved drug’s characteristics, and make a definitive connection. Companies like DrugPatentWatch have built their entire business model on performing this crucial, value-adding task. They meticulously comb through FDA data, patent filings, and litigation records to create a seamless, integrated database where a user can start with a drug name and immediately see all associated patents, regulatory exclusivities, litigation history, and patent expiration forecasts.

This integration transforms raw patent data into actionable business intelligence. It allows a user to ask strategically vital questions like:

- “Which patents protecting the $10 billion/year drug Humira have been challenged in court?”

- “What is the earliest possible date a generic competitor could launch for the cancer drug Keytruda, considering both patents and regulatory exclusivities?”

- “Show me all the formulation patents for oral semaglutide (Rybelsus) that expire after 2030.”

These are questions that are impossible to answer on Google Patents, yet they are the everyday queries that drive billion-dollar decisions in the pharmaceutical industry.

The Absence of Exclusivity Data

Patents are not the only form of intellectual property that keeps generics off the market. Regulatory bodies grant other forms of market exclusivity that are completely independent of patents. A user who looks only at patent expiration dates on Google Patents might get a dangerously misleading picture of the competitive landscape.

Orphan Drug Exclusivity (ODE), New Chemical Entity (NCE) Exclusivity, Pediatric Exclusivity

Here are some of the most critical non-patent exclusivities in the U.S.:

- New Chemical Entity (NCE) Exclusivity: A five-year period of market exclusivity for a drug containing an active ingredient never before approved by the FDA. A generic application cannot even be submitted to the FDA for the first four years [7].

- Orphan Drug Exclusivity (ODE): A seven-year period of market exclusivity for a drug approved to treat a rare disease (affecting fewer than 200,000 people in the U.S.). This exclusivity can block other drugs, even if they are unpatented, from being approved for the same orphan indication [8].

- Pediatric Exclusivity: A six-month extension added to existing patents and exclusivities as a reward for conducting pediatric studies of the drug. This six-month period can be worth billions of dollars for a blockbuster drug.

A generic company might find a drug with patents that are all expired, and, based on a Google Patents search, believe the market is open. However, if the drug has ODE, they are still blocked from the market for several years. This is a catastrophic miscalculation born from looking at an incomplete dataset. Professional platforms integrate this FDA-sourced exclusivity data directly into their drug profiles, providing a clear and complete timeline of all IP barriers to market entry.

The Financial Blind Spot: No Sales Data, No Market Context

All patents are not created equal. A patent covering a niche, first-generation compound that failed in Phase II trials is legally identical to a patent covering a $20 billion/year biologic, but their commercial value is worlds apart. To make smart strategic decisions, you need to prioritize. You need to focus your resources—whether for R&D, litigation, or licensing—on the assets that matter commercially.

A Strong Patent on a Failed Drug: The Value Illusion

Google Patents presents all patents as equals. It provides no context on whether the patented invention ever became a product, let alone a successful one. A business development manager could spend weeks analyzing the patent portfolio of a potential acquisition target, only to find out later that the company’s lead compound, despite its ironclad patent protection, was a commercial flop that barely registered any sales. This is an enormous waste of time and resources.

Using Data to Prioritize Targets

Professional intelligence platforms solve this problem by integrating pharmaceutical sales data. By linking patents to drugs and drugs to their annual sales figures, these platforms allow users to instantly sort and filter opportunities by commercial value.

Imagine you are a director at a generic firm tasked with identifying the top 10 most promising product targets for the next five years. On a platform like DrugPatentWatch, you could run a single query: “Show me all drugs with annual U.S. sales greater than $500 million that will lose both patent protection and regulatory exclusivity in the next 3 to 5 years, and which have fewer than three existing generic filers.”

The result is a highly-qualified, rank-ordered list of strategic targets. This query, which takes minutes on an integrated platform, would be impossible to execute on Google Patents. It would require weeks of manual effort, cross-referencing multiple disconnected databases (patents, FDA, financial reports) and would still be fraught with the risk of error and omission. The ability to overlay commercial data on top of IP data is not a luxury feature; it is fundamental to modern pharmaceutical strategy.

Pitfall #4: The Critical Failure to Track Legal Status and Post-Grant Events

A patent is not a monolith, fixed in time. It is a dynamic legal asset whose strength, validity, and enforceability can change dramatically after it is granted. It can be challenged by competitors, narrowed in scope, or even cancelled entirely. It can lapse for failure to pay fees, be extended through legislative quirks, or become the subject of intense, multi-year litigation. Ignoring this post-grant lifecycle is like navigating by a map drawn on the day a city was founded, oblivious to the new highways, demolished buildings, and redrawn boundaries that have emerged since. Google Patents, by and large, shows you the patent as it was born, not the battle-scarred veteran it may have become.

The Patent “Zombie”: Is it Alive or Dead?

One of the most basic questions you can ask about a patent is: “Is it still in force?” The answer is often surprisingly complex, and Google Patents is ill-equipped to provide a reliable answer.

The Importance of Maintenance Fees and Annuities

In the United States, maintenance fees must be paid to the USPTO at 3.5, 7.5, and 11.5 years after a patent is granted to keep it in force [9]. In Europe and most other countries, these “annuities” must be paid every single year. Failure to pay these fees results in the patent expiring.

This is a frequent occurrence. A company might decide a particular patent is no longer commercially relevant and strategically choose not to pay the fees, allowing it to lapse. A competitor who sees this patent on Google Patents might see its original 20-year expiration date and mistakenly believe it is still a threat, unnecessarily halting or delaying their own projects. They are being spooked by a “zombie” patent—one that looks alive on the surface but is, in fact, legally dead.

Conversely, a company might assume a patent has expired based on non-payment, only to find out the patent owner paid the fee within a grace period or successfully petitioned to have the patent reinstated.

Reliably tracking the payment status of maintenance fees across dozens of countries is a massive data aggregation task. Each country’s patent office has its own database and rules. Professional intelligence platforms specialize in this aggregation, ingesting data from these disparate sources and presenting a simple, clear status for each patent in a family: “Active,” “Expired,” “Lapsed.” This simple status indicator can save thousands of hours of manual research and prevent critical misjudgments about a patent’s enforceability.

The Post-Grant Battlefield: IPRs, PGRs, and Reexaminations

The moment a patent is granted is not the end of the story; it’s often just the beginning of the fight. In the United States, the America Invents Act of 2011 created powerful new ways to challenge the validity of a patent directly at the USPTO’s Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB), without having to go to federal court. The most common of these are:

- Inter Partes Review (IPR): A proceeding where anyone can challenge the validity of patent claims based on prior art consisting of patents or printed publications.

- Post-Grant Review (PGR): A proceeding available within the first nine months of a patent’s grant, allowing a challenge on any ground of invalidity.

These PTAB proceedings have become a central feature of pharmaceutical patent strategy, especially for generic and biosimilar companies seeking to clear a path to market. The outcome of an IPR can invalidate a multi-billion-dollar patent.

Understanding PTAB Proceedings

This PTAB data—the filing of a petition, the decision to institute a trial, the arguments made by both sides, and the final written decision—is a treasure trove of competitive intelligence. It tells you which companies are challenging which patents, what the strongest prior art arguments are, and how strong the patent office itself considers the claims to be.

Where to Find This Data (and why it’s not on Google Patents)

This information resides in the USPTO’s own PTAB database, which is separate from the patent publication database. Google Patents does not integrate this data. You can look at a patent on Google and have no idea that it is currently undergoing a life-or-death struggle in an IPR. You might be basing your strategy on a patent that has a 50% chance of being invalidated in the next six months.

Professional platforms, in contrast, treat PTAB integration as a mission-critical feature. They link every IPR and PGR proceeding directly to the patent being challenged. On a drug’s profile page, a user can see a complete list of all PTAB challenges, their current status, and often links to the key documents. This allows a strategist to assess the real-world strength of a patent, not just its face value. Seeing that three different competitors have filed IPRs against a key formulation patent is a powerful signal about its perceived vulnerabilities.

Litigation Intelligence: The Ultimate Test of a Patent’s Strength

While PTAB challenges are important, the ultimate crucible for a patent’s strength is district court litigation. When a generic company files an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) with a “Paragraph IV” certification, they are essentially telling the FDA that they believe the innovator’s Orange Book-listed patents are invalid or will not be infringed by their generic product [10]. This act almost always triggers a lawsuit from the innovator, and the ensuing litigation is where the fate of billions of dollars in revenue is decided.

The Invisibility of District Court Filings on a Patent Profile

This litigation data—which includes the complaint, the answer, claim construction orders, expert reports, and ultimately, the court’s judgment—is the most valuable intelligence available for assessing a patent’s true strength and the innovator’s strategic posture. It reveals how courts have interpreted the patent’s claims and how resilient the patent is to invalidity arguments.

This data is filed in the U.S. Federal Court system (via the PACER database) and is completely disconnected from the USPTO’s databases. Google Patents has no access to it. You can view the most important patent on a blockbuster drug and have no inkling that it was found invalid by the District of Delaware last year, a decision that is currently under appeal at the Federal Circuit.

Using Litigation Outcomes to Assess Risk

A sophisticated generic company will not just look at a patent’s text; they will look at its litigation history. Has this patent family been litigated before? How did the courts construe the key claim terms? Were the innovator’s infringement arguments strong or weak?

Professional intelligence platforms invest heavily in sourcing and integrating this court data. They link every lawsuit back to the specific patents and drugs involved. This allows a user to see, at a glance, the complete litigation history for a product. This integrated view is essential for risk assessment. A patent that has survived multiple court challenges is a formidable barrier. A patent that has been repeatedly weakened or found invalid in previous cases represents a much lower risk. Making a strategic decision without this litigation intelligence is like walking into a negotiation without knowing the outcome of the last three times your opponent negotiated a similar deal.

The Strategic Implications: How These Pitfalls Translate to Business Risk

The technical pitfalls we’ve discussed—data gaps, flawed search methods, and missing context—are not mere academic concerns. They translate directly into tangible, high-stakes business risks that can impact every facet of a pharmaceutical enterprise. Relying on an incomplete picture of the IP landscape doesn’t just lead to poor analysis; it leads to value-destroying decisions.

Freedom-to-Operate (FTO) Searches: A Minefield on Google Patents

A Freedom-to-Operate (FTO) analysis is perhaps the most critical IP due diligence a company can undertake. The core question is: “Can we launch our planned product without infringing on the valid, in-force patent rights of others?” The consequences of getting this wrong are severe.

The False Negative: Believing You’re Clear When You’re Not

This is the most dangerous risk of all. A team uses Google Patents for an FTO search. They use keywords for their compound and formulation. They search for the innovator’s name. They look at the patents that come up and, based on their expiration dates and a cursory reading, conclude they are in the clear.

They have fallen into every trap we’ve outlined. Their search missed:

- A blocking patent referenced only by an internal project code.

- A broad Markush claim that covers their specific molecule without ever naming it.

- A recently published patent application that hasn’t been indexed by Google yet.

- A key patent filed by a university that the innovator later acquired, so it doesn’t show up under the innovator’s name.

- A “zombie patent” they thought was dead but which was actually revived after a late maintenance fee payment.

Based on this “false negative” result, the company proceeds with a multi-hundred-million-dollar investment in clinical trials and manufacturing. Two years later, on the eve of their product launch, they receive a cease-and-desist letter, followed swiftly by a patent infringement lawsuit.

The Cost of Getting FTO Wrong: Injunctions and Damages

The potential outcomes of such a lawsuit are devastating. A court could issue a preliminary injunction, halting the launch and letting competitors capture the market. If the infringement is proven, the company could be liable for massive damages, including lost profits. If the infringement is found to be “willful”—meaning the company knew about the patent and infringed anyway, or was “willfully blind” to its existence—those damages can be tripled by the court [11].

A flawed FTO search is not just an information gap; it’s a multi-billion-dollar liability waiting to happen. The cost savings of using a free tool are rendered utterly meaningless when compared to the catastrophic cost of a single, undiscovered blocking patent. No serious FTO opinion from legal counsel would ever be based solely on Google Patents searches for precisely these reasons.

Patentability & Prior Art Searches: Building on a Shaky Foundation

For an innovator company, the goal is the opposite of FTO: to secure the broadest, most defensible patent protection possible. This begins with a thorough patentability, or prior art, search. The question here is: “Is our invention new and non-obvious in light of everything that has come before?”

The Risk of an Invalidated Patent

If your R&D team develops a new molecule, and your patent attorney drafts an application based on a prior art search conducted on Google Patents, you are building your IP fortress on sand. The search may have missed a crucial piece of prior art—a foreign patent, a scientific journal article, a Ph.D. thesis—that renders your invention obvious.

You might successfully get the patent granted because the patent examiner, who also has limited time and resources, might also miss that specific piece of art. You celebrate your newly issued patent and proceed to invest a billion dollars to bring the drug to market. The moment you sue your first generic competitor, however, their legal team, using professional-grade tools and databases, will conduct a far more exhaustive search. They will find that obscure piece of prior art your initial search missed. They will use it to challenge your patent in an IPR or in court, and there is a high probability your patent—the foundation of your drug’s entire commercial value—will be invalidated. The billion-dollar investment is now unprotected.

The Examiner’s Perspective vs. The Keyword Searcher

A professional patent searcher, often a former examiner themselves, doesn’t just search for keywords. They think like an examiner. They search across multiple databases (patent and non-patent literature), use classification-based strategies, and understand how to combine references to build an obviousness argument. They know that the most relevant art might not be a single document but a combination of two or three that, when put together, would have made the invention obvious to a person of “ordinary skill in the art.” This conceptual searching is far beyond the capabilities of a simple keyword search on Google Patents.

Competitive Intelligence: Seeing a Distorted Picture

Beyond FTO and patentability, patent data is a vital source of competitive intelligence. It can reveal a competitor’s R&D strategy, their areas of focus, their key inventors, and their potential future products. But if the data is incomplete or out of context, the picture you see is distorted.

Misjudging a Competitor’s IP Moat

You might analyze a competitor’s portfolio on Google Patents and conclude their position around their lead drug is weak, consisting of only a few patents with early expiration dates. Based on this, you decide to launch a competing program.

What you’ve missed is the full picture, which a professional platform would reveal:

- The competitor has a robust portfolio of pending applications that haven’t granted yet.

- They have exclusively in-licensed a key university patent.

- Their main patent has survived three separate IPR challenges, proving its strength.

- They have successfully litigated the patent in Europe, showing they are aggressive in its defense.

- The drug has been granted Orphan Drug Exclusivity, blocking you for seven years regardless of the patent status.

Your assessment of a “weak” IP moat was based on a fraction of the relevant information. The reality is that you are challenging a fortress. This misjudgment leads to a colossal waste of R&D resources on a program that has little chance of commercial success.

Missing Opportunities for Licensing or Acquisition

The distortion works both ways. You might overlook a small biotech company because their visible patent portfolio on Google Patents looks sparse. However, a deeper dive on an integrated platform might show they have a foundational patent application, currently in the 18-month blackout period, that is about to publish and could dominate a new therapeutic area. You miss the opportunity to license or acquire this technology cheaply before its value becomes obvious to the rest of the world. By the time the patent publishes and shows up on Google, you’re in a bidding war with every Big Pharma company. The opportunity for a high-value, early-stage deal has been lost due to a lack of timely, forward-looking intelligence.

Bridging the Gap: The Rise of Professional Pharmaceutical Intelligence Platforms

The inherent limitations of a generalist tool like Google Patents have created a clear and compelling need for specialized, professional-grade solutions. These platforms are not merely search engines; they are comprehensive intelligence systems designed from the ground up to address the unique complexities of the pharmaceutical industry. They bridge the gap between raw data and actionable strategy by focusing on three core pillars: curation, integration, and domain-specific functionality.

What Sets a Professional Platform Apart?

The difference between using Google Patents and a professional platform is the difference between being given a dictionary and having a conversation with a linguist. Both involve words, but one provides data while the other provides understanding.

Curation and Data Integration as a Core Philosophy

At the heart of any professional platform is the philosophy of curation. These services understand that raw data from patent offices is messy, inconsistent, and disconnected. Their primary value proposition is to clean, normalize, and, most importantly, integrate this data.

This involves:

- Assignee Normalization: Ensuring that “Pfizer Inc.,” “Pfizer,” and “Pfizer R&D” are all correctly identified as the same entity, allowing for a truly comprehensive view of a company’s portfolio.

- Data Cleaning: Correcting errors in raw data feeds, filling in missing information, and standardizing formats across dozens of international sources.

- Deep Integration: Building the crucial links between disparate datasets. A single patent is linked to the drug it protects, the company that owns it, the regulatory exclusivities associated with that drug, the PTAB challenges against the patent, and the court cases where it has been asserted. This creates a rich, multi-layered profile for every asset.

This curated, integrated database becomes a single source of truth, eliminating the need for users to manually cross-reference a half-dozen different websites and hope they’ve connected the dots correctly.

Expert Annotation and Human Oversight

While algorithms are powerful, they lack human judgment. Professional platforms employ teams of subject matter experts—Ph.D. scientists, pharmacists, and IP analysts—to provide a layer of human intelligence on top of the data. This can involve:

- Creating custom taxonomies for specific drug classes or technologies.

- Manually verifying the link between a patent and a product.

- Summarizing the outcomes of complex litigation in plain English.

- Forecasting patent expiration dates by taking into account not just the statutory term, but also potential extensions like Patent Term Adjustment (PTA) and Pediatric Exclusivity.

This human oversight ensures the data is not just accurate but also contextually relevant and easy to understand for business professionals, not just patent attorneys.

Advanced, Domain-Specific Search Capabilities

Recognizing the failure of simple keyword searching, professional platforms offer a suite of advanced, domain-specific search tools tailored to the needs of pharma users. These include:

- Integrated Chemical Structure Search: The ability to draw a chemical structure, substructure, or scaffold and find all patents that claim it, including within complex Markush claims.

- Biosequence Searching: For biologics, the ability to search for specific DNA, RNA, or amino acid sequences within patent claims and disclosures.

- Advanced Fielded Searching: The ability to construct highly specific queries that combine dozens of different fields, such as “Find all patents assigned to Merck, related to oncology, with a priority date after 2020, that are currently involved in an IPR proceeding.”

These tools empower users to ask precise strategic questions and receive precise, relevant answers, cutting through the noise that plagues generalist search engines.

A Closer Look at the Solution: How Platforms like DrugPatentWatch Operate

To make this concrete, let’s consider a platform like DrugPatentWatch. It exemplifies the professional approach by focusing on providing business intelligence, not just patent data. A typical workflow on such a platform completely transforms the user experience compared to Google Patents.

Linking Patents to Drugs, Exclusivities, and Litigation

A user doesn’t start with a patent number or a keyword. They start with a business question. For example, they can simply type the name of a drug, like “Ozempic,” into the search bar. The result is not a list of 10,000 patent documents. Instead, they get a comprehensive dashboard for the drug itself.

This dashboard immediately shows:

- The active ingredient (semaglutide) and its marketer (Novo Nordisk).

- Annual sales figures and trends.

- A list of all Orange Book-listed patents, each with a calculated, expert-verified expiration date.

- A clear timeline of all regulatory exclusivities (e.g., NCE, Pediatric).

- A list of all known litigation and PTAB challenges related to the drug’s patents, with status updates.

- A predictive timeline showing the earliest possible date for generic or biosimilar entry.

Every piece of data is linked. You can click on a patent and see its full details. You can click on a lawsuit and see which patents are being disputed. The information is presented in a way that directly supports strategic decision-making.

Providing Actionable Business Intelligence, Not Just Raw Data

The goal of a platform like DrugPatentWatch is to accelerate the path from data to insight. It achieves this through alerts, reports, and analytical tools built on top of its integrated database. A business development manager can set up an alert to be notified by email the moment a new patent is listed in the Orange Book for a competitor’s drug. A generic strategist can generate a report of all major products losing exclusivity in the next five years, sorted by market size.

This proactive, intelligence-driven approach is a world away from the reactive, manual process of piecing together clues from a simple search engine.

The Power of Predictive Analytics: Forecasting Patent Expirations and Generic Entry

Perhaps one of the most sophisticated features is the use of predictive analytics. Calculating a patent’s true expiration date is not as simple as adding 20 years to its filing date. It can be shortened by terminal disclaimers or lengthened by Patent Term Extension (PTE) for regulatory delays and Patent Term Adjustment (PTA) for patent office delays. These calculations are complex. Professional platforms automate them and combine them with exclusivity data to provide a clear, visual timeline forecasting when a product’s monopoly is likely to end. This predictive capability is one of the highest-value outputs, directly informing multi-billion-dollar R&D and launch-timing decisions.

The ROI of Professional Tools: An Investment, Not an Expense

It is tempting for organizations to balk at the subscription cost of a professional intelligence platform when a “free” alternative like Google Patents exists. This is a classic false economy. The true cost of an information resource is not its price tag; it is the cost of the mistakes made due to its inadequacies.

Calculating the Cost of a Single Mistake

- What is the cost of a 6-month delay in a generic launch because you missed a patent’s true expiration date? For a major drug, this can easily be $100 million – $500 million in lost revenue.

- What is the cost of being forced to settle an infringement lawsuit for a patent your FTO search missed? Likely in the tens of millions of dollars, plus legal fees.

- What is the cost of investing $50 million into an R&D program only to find it’s blocked by a competitor’s patent you couldn’t find?

- What is the cost of your team of five Ph.D. scientists spending 100 hours each manually searching and cross-referencing data, when a single query on a professional platform could have answered the question in minutes?

When viewed against these potential losses, the subscription fee for a high-quality intelligence platform is not an expense; it is a remarkably cheap insurance policy.

Speed to Insight: The Competitive Advantage

In today’s hyper-competitive pharmaceutical market, speed is paramount. The team that can most quickly and accurately assess a landscape, identify an opportunity, or spot a threat is the team that wins. Professional platforms are force multipliers, enabling smaller teams to perform high-level analysis and allowing large organizations to make faster, more confident decisions. The ROI is measured not just in risks avoided, but in opportunities seized before the competition even knows they exist.

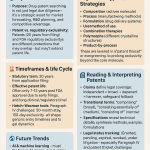

A Practical Guide: When is Google Patents “Good Enough”?

Our in-depth critique is not meant to suggest that Google Patents has no value. It is a powerful tool when used appropriately, for tasks where its limitations do not pose a strategic risk. Acknowledging its proper place in the toolbox is key to a balanced IP intelligence strategy. So, when is it okay to turn to the free search bar?

Quick & Dirty Preliminary Searches

At the very nascent stages of an idea, Google Patents can be excellent for a quick, informal “smell test.” A scientist has a new idea for a drug target. A 15-minute search on Google Patents can give a rough sense of how crowded the field is. Is it wide open, or are there thousands of documents from major players? This is not a definitive search, but it can help in the early brainstorming phase to quickly weed out ideas that are clearly non-starters before dedicating serious resources.

Educational Purposes and General Exploration

For students, academics, journalists, or anyone outside the commercial IP world, Google Patents is a fantastic educational resource. It’s an accessible way to learn about the patent system, explore the inventions of a particular company, or simply satisfy curiosity about how a certain technology works. In these low-stakes scenarios, the risks of data gaps or lack of context are negligible.

Finding a Specific, Known Patent Document

If you already have a patent or publication number and simply need to retrieve the document to read it or download a PDF, Google Patents is often the fastest and easiest way to do so. Its performance as a document retrieval tool is excellent. The danger arises not in retrieving the document, but in making assumptions based only on the face of that document without the surrounding legal and commercial context.

In essence, Google Patents is suitable for any task where the cost of being wrong is low. However, the moment a decision involves significant investment, legal risk, or strategic commitment—the bread and butter of the pharmaceutical industry—it is time to graduate to a professional tool built for the task at hand.

Conclusion: Moving Beyond the Free Search Bar

The siren’s song of Google Patents is its deceptive simplicity. It offers a free, user-friendly window into the world of intellectual property, promising to democratize access to vital information. While it has succeeded in raising basic patent awareness, this very accessibility masks a series of profound and dangerous pitfalls for any organization making serious business decisions in the pharmaceutical arena.

Recapping the Hidden Costs of “Free”

We’ve seen that the “free” in Google Patents comes at a hidden cost. The cost of incomplete and lagging data that can cause you to miss a newly published threat. The cost of a keyword-based search that is blind to the chemical structures and legal jargon that define a patent’s true scope. The cost of viewing a patent in a vacuum, divorced from the FDA regulatory data, litigation history, and commercial context that determine its real-world value and strength. And the cost of being unaware of a patent’s current legal status, leaving you to fight zombie patents or build strategies on IP that has already been invalidated.

These are not trivial shortcomings. They are fundamental gaps that lead directly to flawed FTO analyses, weak patent filings, and distorted competitive intelligence. They create a business risk that is simply unacceptable in an industry where a single IP mistake can be measured in the tens of millions, if not billions, of dollars.

Embracing a Holistic, Data-Driven Approach to Pharmaceutical IP Strategy

The alternative is not to abandon search technology, but to embrace a more sophisticated, holistic approach. The future of pharmaceutical strategy lies in integrated intelligence platforms that treat patent data not as the endpoint, but as a single, crucial layer in a multi-dimensional map. This map must include regulatory pathways, market data, legal proceedings, and chemical intelligence, all curated, connected, and analyzed by a combination of powerful technology and human expertise.

Platforms like DrugPatentWatch and their peers are not just “better search engines.” They are strategic decision-support systems. They are designed to answer not just “What does this patent say?” but “What does this patent mean for my business?” They replace ambiguity with clarity, manual labor with automated insight, and unacceptable risk with informed confidence.

The Final Word: Your IP Strategy Deserves More Than a Search Engine

Ultimately, the choice of an information tool is a reflection of how seriously an organization takes its strategic functions. Using a generic search engine for a mission-critical pharmaceutical IP analysis is like asking a family doctor to perform neurosurgery. Both are medical professionals, but the context demands a specialist with the right tools, training, and depth of knowledge.

Your intellectual property is the lifeblood of your company. It underpins your R&D investments, protects your market share, and drives your long-term value. An IP strategy built on a foundation of incomplete, decontextualized, and potentially outdated information is not a strategy at all—it’s a gamble. It’s time to move beyond the free search bar and invest in the professional intelligence your business deserves. The stakes are simply too high for anything less.

Key Takeaways

- High-Stakes Environment: Pharmaceutical patent analysis is a critical business function where errors can lead to billions in losses, making “good enough” tools dangerously insufficient.

- Google Patents is a Search Engine, Not an Intelligence Platform: Its core function is text retrieval, which is fundamentally unsuited for the complexities of pharmaceutical patents, especially regarding chemical structures (Markush claims) and legal terminology.

- Data Gaps and Lags are a Major Risk: Reliance on Google Patents can cause you to miss recently published applications (due to indexing delays) or misinterpret a patent’s scope due to incomplete international data or unreliable machine translations.

- Context is King: The true value and strength of a patent can only be understood by integrating it with external data sets that Google Patents lacks, including FDA regulatory data (Orange Book), non-patent exclusivities, litigation history (PTAB & District Courts), and commercial sales data.

- Legal Status is Dynamic: Google Patents provides a static view of a patent. It cannot reliably track a patent’s current enforceability, such as whether maintenance fees have been paid or if the patent has been invalidated in a post-grant proceeding.

- Strategic Risks are Tangible: These pitfalls directly translate into business disasters like failed Freedom-to-Operate (FTO) searches leading to infringement, weak patentability analyses leading to invalidated patents, and flawed competitive intelligence.

- Professional Platforms Offer a Solution: Specialized services like DrugPatentWatch provide value through data curation, integration, and expert annotation, offering domain-specific tools (e.g., chemical structure search) that turn raw data into actionable business intelligence.

- The ROI of Professional Tools is Clear: The subscription cost of a professional platform is a negligible expense when compared to the catastrophic financial and strategic costs of a single IP mistake.

Frequently Asked questions (FAQ)

1. Can’t I just use Google Patents for a preliminary search and then have my patent attorney finalize it?

While this sounds like a reasonable workflow, it’s inefficient and can still be risky. By starting with an incomplete tool, you may lead your internal team or your expensive legal counsel down the wrong path, wasting valuable time and resources analyzing an incomplete landscape. Furthermore, you might make a preliminary “no-go” decision on a project based on flawed data from Google Patents, killing a valuable opportunity before it ever reaches your attorney. Using a professional platform from the start ensures that everyone, from the bench scientist to senior counsel, is working with the same high-quality, contextualized data from day one.

2. Our company is a small startup with a limited budget. How can we justify the cost of a professional subscription?

For a startup, the IP strategy is arguably even more critical than for an established player, as the entire company’s valuation often rests on its core intellectual property. The cost of a subscription should be viewed as a core R&D or business development expense, not an optional luxury. The cost of making one wrong move—pursuing a blocked technology or failing to adequately protect your own invention—is an existential threat to a startup. The ROI is realized by avoiding that single catastrophic error, securing a stronger position for fundraising or partnership, and operating with a speed and confidence that belies your size.

3. Besides the specific pitfalls mentioned, what is the single biggest conceptual mistake people make when using Google Patents?

The biggest conceptual mistake is equating “finding a document” with “understanding a situation.” Google Patents is excellent at the former. The user feels successful because they typed in keywords and received a list of patent documents. However, this success is illusory. They haven’t understood the competitive landscape, the patent’s legal strength, its connection to a commercial product, or its true expiration date. They have simply retrieved text. The mistake is believing that data retrieval is a substitute for genuine intelligence analysis.

4. How does a platform like DrugPatentWatch actually get all the litigation and regulatory data that Google Patents is missing?

This is a core part of their value proposition and a significant operational undertaking. These platforms build sophisticated, automated systems and employ expert teams to gather data from dozens of disparate sources. They have direct data feeds from patent offices, they systematically scrape FDA databases like the Orange Book, they tap into court record databases like PACER for litigation filings, and they pull data from the PTAB’s public portals. The crucial step is then using a combination of algorithms and human experts to parse, clean, and—most importantly—link all this information together, connecting a specific lawsuit back to the exact patent and the drug it protects. This data aggregation and integration is a full-time, expert job.

5. If Google wanted to, couldn’t they add all these features and make their tool just as good as the professional platforms?

Theoretically, yes. Google has immense technical resources. However, it’s a question of business model and focus. Google’s core business is organizing the world’s public information and selling advertising. The level of niche, expert-driven curation, manual data verification, and specialized customer support required for a high-end pharmaceutical intelligence platform is far outside this core model. It requires deep domain expertise in patent law, medicinal chemistry, and FDA regulation. While Google could acquire a company in this space, it’s unlikely they would build such a specialized, high-touch service from scratch, as it doesn’t scale in the same way their primary advertising business does.

References

[1] Wouters, O. J., McKee, M., & Luyten, J. (2020). Estimated Research and Development Investment Needed to Bring a New Medicine to Market, 2009-2018. JAMA, 323(9), 844–853.

[2] United States Patent and Trademark Office. (n.d.). 18-Month Publication of Patent Applications. Retrieved from https://www.uspto.gov/web/offices/pac/mpep/s1120.html

[3] World Intellectual Property Organization. (n.d.). The PCT Applicant’s Guide. Retrieved from [suspicious link removed]

[4] World Intellectual Property Organization. (2011). WIPO Standard ST.26. Annex C, Technical Annex, Section 7. (This reference synthesizes the concept of the prevalence and importance of Markush claims as discussed in WIPO technical standards and general industry knowledge).

[5] U.S. Food & Drug Administration. (n.d.). Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations (Orange Book). Retrieved from https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-approvals-and-databases/approved-drug-products-therapeutic-equivalence-evaluations-orange-book

[6] U.S. Food & Drug Administration. (n.d.). Purple Book: Lists of Licensed Biological Products with Reference Product Exclusivity and Biosimilarity or Interchangeability Evaluations. Retrieved from https://purplebook.fda.gov

[7] U.S. Food & Drug Administration. (n.d.). Frequently Asked Questions on Patents and Exclusivity. Retrieved from https://www.fda.gov/drugs/development-approval-process-drugs/frequently-asked-questions-patents-and-exclusivity

[8] U.S. Food & Drug Administration. (n.d.). Orphan Drug Act – Relevant Excerpts. Retrieved from https://www.fda.gov/industry/developing-products-rare-diseases-conditions/orphan-drug-act-relevant-excerpts

[9] United States Patent and Trademark Office. (n.d.). Maintaining a patent. Retrieved from https://www.uspto.gov/patents/maintain

[10] U.S. Food & Drug Administration. (n.d.). Hatch-Waxman Letters. Retrieved from https://www.fda.gov/drugs/abbreviated-new-drug-application-anda/hatch-waxman-letters

[11] Supreme Court of the United States. (2016). Halo Electronics, Inc. v. Pulse Electronics, Inc., 579 U.S. ___ (2016). This case clarified the standard for willful infringement and enhanced damages.