Introduction

The Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984, colloquially known as the Hatch-Waxman Act, represents a landmark legislative compromise that fundamentally reshaped the American pharmaceutical landscape. Conceived as a grand bargain, the Act sought to resolve a deep-seated conflict between two critical public policy objectives: fostering the high-risk, high-cost innovation required to develop new life-saving medicines and ensuring broad, affordable public access to those medicines once their period of exclusivity had reasonably expired. By creating a modern, streamlined pathway for generic drug approval while simultaneously offering a mechanism to restore patent life lost to regulatory delays, the Act successfully catalyzed the growth of a robust generic drug industry, leading to profound public health benefits and trillions of dollars in healthcare savings.1

However, the history of the past four decades reveals that this grand bargain was not a static solution but the beginning of an ongoing, dynamic struggle. The intricate legal and regulatory framework established by Hatch-Waxman inadvertently created a new and complex battlefield. On this field, sophisticated legal, regulatory, and commercial strategies—many of which were not fully anticipated by the Act’s drafters—are now deployed by both innovator and generic firms to gain competitive advantage.3 Practices such as “evergreening,” the creation of dense “patent thickets,” and strategic litigation settlements have emerged as powerful tools to extend market monopolies, perpetually challenging the delicate balance the Act was designed to achieve.1

This report provides a comprehensive historical analysis of this evolution. It begins by examining the dysfunctional pre-1984 landscape that necessitated legislative intervention. It then deconstructs the original architecture of the Hatch-Waxman Act, detailing the specific provisions that formed its central compromise. The analysis traces the subsequent interpretation of the Act by the judiciary and its refinement through further legislation, highlighting how its core tenets have been tested and reshaped over time. The report dissects the industry’s strategic responses, using detailed case studies of blockbuster drugs to illustrate how the Act’s framework has been leveraged and, at times, exploited. It proceeds to quantify the profound economic consequences of this system on drug pricing, innovator revenues, and research and development (R&D) investment. Finally, by comparing the U.S. system to its primary international counterpart in the European Union and assessing the current state of reform efforts, this report offers a holistic and nuanced perspective on the past, present, and future of pharmaceutical patent policy in the United States.

Section I: The Genesis of the Grand Bargain: The Pre-1984 Pharmaceutical Landscape

To understand the profound impact of the Hatch-Waxman Act, one must first appreciate the deeply flawed and economically inefficient system it replaced. The pre-1984 pharmaceutical market was characterized by a series of legal and regulatory distortions that simultaneously stifled innovation and suppressed competition, creating a system that served neither innovator companies, generic manufacturers, nor the public interest.8

The Innovator’s Dilemma: The “Drug Lag” and Eroding Patent Terms

For innovator pharmaceutical companies, the primary challenge was the steady erosion of their effective patent life. A U.S. patent granted a 17-year term of exclusivity from the date of issuance.10 However, the regulatory hurdles required to bring a new drug to market were becoming increasingly formidable. Following the thalidomide tragedy of the late 1950s, Congress passed the 1962 Kefauver-Harris Amendments to the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic (FD&C) Act.11 These amendments significantly strengthened the authority of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), mandating for the first time that manufacturers prove not only that a new drug was safe, but also that it was

effective for its intended use.11

While a crucial advancement for public health, this new efficacy requirement substantially lengthened the clinical trial and regulatory review process, a period often referred to as the “drug lag”.8 Because the patent clock started ticking from the date of issuance, regardless of when the drug was approved for marketing, innovator companies were losing a substantial portion of their patent term—sometimes up to a decade or more—before they could earn a single dollar in revenue.8 This significant reduction in the effective period of market exclusivity diminished the potential return on investment, creating a powerful disincentive for the costly and high-risk R&D necessary to discover new medicines.8

The Generic Manufacturer’s Impasse

The environment for generic drug manufacturers was equally untenable. Before 1984, there was no abbreviated pathway for generic drug approval. A generic company wishing to market a copy of an approved brand-name drug was required to submit its own full New Drug Application (NDA) to the FDA.14 This meant conducting independent, and entirely duplicative, clinical trials to prove the safety and efficacy of its product, even though the active ingredient had already been proven safe and effective by the innovator company.8 This process was prohibitively expensive, unnecessarily time-consuming, and created a formidable barrier to entry for potential competitors.14

The Roche v. Bolar Decision and the De Facto Patent Extension

The situation for generics was critically exacerbated by the prevailing interpretation of patent law, which was solidified in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit’s 1984 decision in Roche Products, Inc. v. Bolar Pharmaceutical Co..15 Bolar, a generic manufacturer, had begun conducting bioequivalence testing on a patented drug before the patent’s expiration in preparation for filing an NDA. Roche sued for patent infringement, and the court sided with the innovator, ruling that using a patented invention for testing and regulatory submission purposes was not exempt from infringement.15

This ruling created a second major distortion to the patent term. It meant that generic companies could not even begin the multi-year process of development and FDA review until after the innovator’s patent had fully expired.8 The practical effect was a

de facto extension of the innovator’s market monopoly. Even after a patent expired, the brand-name drug would continue to face no competition for the additional time—an average of three years—that it took the first generic to complete its own regulatory process and gain FDA approval.16

Market Stagnation

The combined effect of these “patent term distortions” was a dysfunctional and non-competitive market.8 Innovator firms saw their valuable patent terms being consumed by regulatory delays, while generic firms were legally and financially blocked from entering the market in a timely manner. This resulted in a stagnant generic market where consumers were denied access to lower-cost alternatives long after patents had expired. In 1984, generic drugs accounted for a mere 19% of all prescriptions filled in the U.S., and only about 35% of top-selling brand-name drugs faced any generic competition after their patents lapsed.8

This landscape created a paradox. The very regulatory framework designed to protect public health by ensuring drug safety and efficacy had inadvertently created a system that was economically inefficient and harmful to both innovation and competition. The stringent FDA requirements that made drugs safer also made them less accessible by crippling the generic market, while simultaneously diminishing the financial incentives for developing new drugs by eroding the effective patent term. This untenable situation created the political impetus for a comprehensive legislative solution, culminating in the “grand legislative compromise” that became the Hatch-Waxman Act.1

Section II: The Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984

Enacted on September 24, 1984, the Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act (Public Law 98-417), or Hatch-Waxman Act, was a masterclass in legislative compromise.19 Sponsored by Senator Orrin Hatch (R-UT) and Representative Henry Waxman (D-CA), the Act meticulously balanced the competing demands of the innovator and generic pharmaceutical industries by amending both the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act and Title 35 of the U.S. Code governing patents.14 It created a new, symbiotic relationship between the two sectors, fundamentally reshaping the pharmaceutical market.

A. Provisions for Generic Competition: Opening the Floodgates

The Act’s most transformative provisions were aimed at dismantling the barriers that had long prevented a robust generic drug market from emerging.

The Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA)

The cornerstone of the Act was the creation of the Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) pathway, codified in Section 505(j) of the FD&C Act.14 This provision allowed generic manufacturers, for the first time, to rely on the FDA’s prior finding of safety and effectiveness for an approved brand-name drug (the “reference listed drug”).11 Instead of conducting their own costly and duplicative clinical trials, generic applicants were now required only to demonstrate that their product was

bioequivalent to the reference drug.15 Bioequivalence meant proving that the generic product contained the same active ingredient(s), dosage form, strength, and route of administration, and that it was absorbed by the body at a comparable rate and to a comparable extent.11 This streamlined process dramatically reduced the time and cost of generic drug development, lowering the cost from many millions of dollars to approximately $1 million to $2 million and shortening the approval timeline from years to months.16

The “Safe Harbor” Provision (35 U.S.C. § 271(e)(1))

To ensure that generic firms could take full advantage of the new ANDA pathway, the Act statutorily overturned the Roche v. Bolar decision.15 The new “safe harbor” provision stipulated that it was not an act of patent infringement to make, use, or sell a patented invention “solely for uses reasonably related to the development and submission of information under a Federal law which regulates the manufacture, use, or sale of drugs”.18 This critical change allowed generic companies to begin their development work and bioequivalence testing

before the innovator’s patents expired, enabling them to prepare their ANDAs and be ready for market entry on the very day of patent expiration.2

The “Orange Book” and Patent Certifications

The Act mandated that the FDA publish a list of all approved drug products, which became known as the “Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations,” or the Orange Book.14 Innovator companies were required to identify and list in the Orange Book any patents that they asserted could reasonably be infringed by the manufacture, use, or sale of an unapproved version of their drug.16

When submitting an ANDA, a generic applicant was required to review the Orange Book and make one of four certifications for each listed patent 16:

- Paragraph I Certification: That no patent information has been filed for the reference drug.

- Paragraph II Certification: That the listed patent has already expired.

- Paragraph III Certification: Stating the date on which the patent will expire, with the generic applicant agreeing not to market its product until that date.

- Paragraph IV Certification: That the listed patent is invalid, unenforceable, or will not be infringed by the marketing of the generic product.

Incentivizing Patent Challenges: The 180-Day Exclusivity

To encourage generic manufacturers to actively challenge patents they believed were weak or invalid, the Act created a powerful financial incentive. It granted a 180-day period of market exclusivity to the first generic applicant to file a substantially complete ANDA containing a Paragraph IV certification.11 During this six-month period, the FDA could not approve any subsequent ANDAs for the same drug, allowing the first challenger to enjoy a period of limited competition (often a duopoly with the brand) and capture significant market share.

B. Incentives for Innovators: Restoring Lost Time

In exchange for these pro-generic provisions, the Act provided significant new protections for innovator companies, designed to restore the incentives for R&D that had been eroded by regulatory delays.

Patent Term Extension (PTE)

Title II of the Act established a formal mechanism for Patent Term Extension (PTE), allowing innovator companies to apply to the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) to restore a portion of the patent term that was consumed during the FDA’s clinical testing and regulatory review periods.1 This was the central concession to the brand-name industry, aimed at ensuring that the patent system could continue to provide a meaningful period of market exclusivity to recoup massive R&D investments.10

Data and Market Exclusivity

Crucially, the Act also created new forms of regulatory exclusivity that are administered by the FDA and operate entirely independently of patents.15 These exclusivities provided a guaranteed period of market protection, even if a drug had no patent protection at all. The two most important were:

- Five-Year New Chemical Entity (NCE) Exclusivity: Granted to the first approval of a drug containing an active ingredient (or “active moiety”) never before approved by the FDA. For five years from the date of the brand’s approval, the FDA was prohibited from accepting any ANDA for a generic version of that drug. A generic firm wishing to file a Paragraph IV challenge could file its ANDA after four years.19

- Three-Year New Clinical Study Exclusivity: Awarded for the approval of an application or supplement that contained new clinical investigations (other than bioavailability studies) that were essential to the approval. This typically applied to changes to previously approved drugs, such as new indications, new dosage forms, or a switch from prescription to over-the-counter (OTC) status. This exclusivity blocked the FDA from approving an ANDA for that specific change for three years.28

The Hatch-Waxman Act did not simply create a quid pro quo of generic entry for patent extension. It engineered a complex, interconnected ecosystem where patent law and food and drug law became fused. The listing of a patent in the FDA’s Orange Book became a regulatory act with immediate and profound commercial consequences.24 The filing of a Paragraph IV certification by a generic company was defined as a new, “artificial act of infringement,” a legal trigger that initiated a highly structured and predictable litigation pathway.15 This pathway included unique procedural mechanisms not found elsewhere in patent law, most notably an automatic 30-month stay of the generic’s FDA approval upon the filing of an infringement suit by the brand company.33 This provision effectively granted the innovator a preliminary injunction without having to meet the traditional legal standards for such relief. The 180-day exclusivity reward transformed the first generic challenger into a pivotal market player, whose strategic decisions could determine the timing of market entry for all subsequent generic competitors.11 In essence, the Act’s genius—and the source of its future complexities—was in creating a formal, pre-market framework for resolving patent disputes, fundamentally altering the business and legal strategies of the entire pharmaceutical industry.

| Provision | Beneficiary | Purpose | Key Details |

| Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) | Generic | To expedite generic drug approval and lower market entry barriers. | Allows reliance on innovator’s safety/efficacy data; requires only proof of bioequivalence.14 |

| “Safe Harbor” (35 U.S.C. § 271(e)(1)) | Generic | To allow pre-expiration development of generics. | Overturns Roche v. Bolar; exempts activities related to FDA submissions from patent infringement.15 |

| 180-Day Generic Exclusivity | Generic | To incentivize challenges to innovator patents. | Awarded to the first generic applicant to file a Paragraph IV certification, blocking other ANDAs for 6 months.11 |

| Patent Term Extension (PTE) | Innovator | To restore patent life lost during the FDA regulatory review process. | Restores a portion of time lost, subject to a 5-year maximum extension and a 14-year cap on total market life post-approval.10 |

| 5-Year New Chemical Entity (NCE) Exclusivity | Innovator | To provide a guaranteed market monopoly for novel drugs. | Blocks the FDA from accepting an ANDA for 5 years (or 4 years for a Paragraph IV challenge) for a new active ingredient.30 |

| 3-Year New Clinical Study Exclusivity | Innovator | To incentivize further research and improvements on existing drugs. | Blocks FDA approval of an ANDA for 3 years for a specific change supported by new, essential clinical trials.28 |

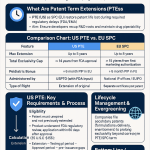

Section III: The Mechanics and Justification of Patent Term Extension

The provision for Patent Term Extension (PTE) was the central pillar of the Hatch-Waxman Act’s concessions to the innovator pharmaceutical industry. Governed by 35 U.S.C. § 156, its explicit purpose is to restore a portion of the patent term that is unavoidably lost while a product undergoes the mandatory and lengthy regulatory review process required for marketing approval.29 This mechanism was designed to preserve the economic incentive for innovation by ensuring that a patent provides a commercially meaningful period of market exclusivity.10

Statutory Basis and Eligibility Requirements

To qualify for a PTE, a patent and the associated product must meet a series of stringent statutory requirements, ensuring that the extension is narrowly targeted 29:

- Patent Status: The patent for which an extension is sought must not have expired at the time of application.

- No Prior Extension: The term of the patent must not have been previously extended under 35 U.S.C. § 156. A single patent can only be extended once.

- Timely Application: The patent owner must submit a complete application to the USPTO within a strict 60-day period following the date of the product’s marketing approval from the FDA.

- Regulatory Review: The product must have been subjected to a “regulatory review period” before its commercial marketing or use was permitted.

- First Permitted Use: The marketing approval must be the first permitted commercial marketing or use of the product’s active ingredient. This is a critical limitation that has been the subject of significant litigation.

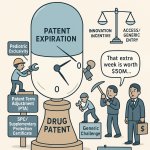

The PTE Calculation Formula

The statute does not provide a simple day-for-day restoration of lost time. Instead, it employs a complex formula designed to credit the patent holder for different phases of the regulatory process at different rates, while also penalizing any lack of diligence.16 The length of the extension is calculated as:

PTE=(21×Testing Period)+(1×Approval Period)

- Testing Period: This is the period beginning on the effective date of the Investigational New Drug (IND) application and ending on the date the New Drug Application (NDA) or Biologics License Application (BLA) is initially submitted to the FDA. The patent holder receives credit for only one-half of the duration of this period.

- Approval Period: This is the period beginning on the date the NDA or BLA was submitted and ending on the date of its approval by the FDA. The patent holder receives full, day-for-day credit for this period.

This total is then subject to several important deductions. The extension is reduced by any period during which the applicant did not act with “due diligence” as determined by the FDA, and by any portion of the regulatory review period that occurred before the patent was granted.29

Statutory Caps and Limitations

Even after this complex calculation, the final extension period is constrained by two overarching statutory caps that place firm limits on the total benefit an innovator can receive 10:

- The 5-Year Maximum: The total extension granted cannot exceed five years, regardless of how long the regulatory review period was.

- The 14-Year Cap: The total remaining term of the patent after the extension is applied cannot be more than 14 years from the date of the product’s FDA approval. This cap is intended to limit the total effective market life of the product post-approval.

Scope of the Extended Right

A crucial, and often misunderstood, aspect of PTE is that it does not extend the full scope of the original patent’s claims. During the extension period, the rights conferred by the patent are limited to the approved product, its approved method of use, or its method of manufacture.29 This means the patent holder cannot use the extended term to sue for infringement based on other, unapproved uses of the patented technology that would have been covered by the original patent claims.

The strict eligibility rules, particularly the “first permitted use” and “one patent per product” limitations, have created a high-stakes strategic landscape for innovator companies. A company may hold multiple patents covering a single drug—for the active compound, a specific formulation, a method of use, or a manufacturing process.32 However, it can only choose

one of these patents to extend for that drug’s first approval.16 This decision, which must be made within the 60-day window after FDA approval, is critical. The company must analyze its patent portfolio to determine which patent, when extended, will provide the most robust and durable protection against generic competition. This has led to intense legal battles over the definition of a “product.” For instance, the Federal Circuit has grappled with whether a new ester or salt form of a previously approved active ingredient constitutes a new “product” eligible for its own PTE, with decisions like

Photocure v. Kappos and Novartis v. Ezra Ventures shaping the boundaries of this rule.4 These cases demonstrate that the seemingly straightforward statutory requirements are, in practice, a fertile ground for sophisticated legal maneuvering and strategic planning aimed at maximizing a drug’s period of market exclusivity.

Section IV: The Act in Practice: Evolution, Judicial Interpretation, and Legislative Refinement

The Hatch-Waxman Act, as enacted in 1984, was not a final, static framework but rather the foundation upon which four decades of judicial interpretation, strategic industry behavior, and legislative correction have been built. The practical application of the Act has been continuously shaped by the courts, which have been called upon to clarify its ambiguities, and by Congress, which has intervened to close loopholes that emerged over time.

A. Landmark Judicial Interpretations: The Supreme Court Weighs In

The Supreme Court has played a pivotal role in defining the contours of the Hatch-Waxman framework, issuing a series of landmark decisions that have clarified the rights and obligations of both innovator and generic manufacturers.

Defining the “Safe Harbor”

The scope of the § 271(e)(1) “safe harbor” was an early point of contention. In Eli Lilly & Co. v. Medtronic, Inc. (1990), the Court established a broad interpretation, holding that the safe harbor’s protection from infringement claims extended not only to generic drugs but also to medical devices.18 The Court reasoned that since device manufacturers were also eligible for patent term extensions under the Act, the overall statutory structure implied a “perfect ‘product’ fit” where the safe harbor should apply symmetrically.18 Fifteen years later, in

Merck KGaA v. Integra Lifesciences I, Ltd. (2005), the Court further expanded the safe harbor’s reach, ruling that it covers a wide range of preclinical research activities—not just activities directly included in a regulatory submission—as long as they are “reasonably related” to the development of information for the FDA.18 Together, these decisions provided robust protection for a wide array of R&D activities essential for generic and biosimilar development.

Clarifying Generic Rights and Responsibilities

The Court has also issued key rulings that both empower and constrain generic manufacturers. In Caraco Pharmaceutical Laboratories, Ltd. v. Novo Nordisk A/S (2012), the Court sided with the generic industry, holding that a generic applicant could use the Act’s counterclaim provision to compel a brand-name company to correct an overly broad or inaccurate “use code” in the Orange Book.18 This was a significant victory for generics, as it strengthened their ability to “carve out” patented indications from their labels and market their products for non-infringing uses.

Conversely, in a pair of preemption cases, the Court reinforced the strict limitations on generic autonomy. In PLIVA, Inc. v. Mensing (2011) and Mutual Pharmaceutical Co. v. Bartlett (2013), the Court held that federal law preempts state-law tort claims against generic manufacturers for failure-to-warn and defective design.18 The reasoning was that generic companies have an “ongoing federal duty of ‘sameness'”—their labels and product composition must be identical to the brand-name reference product. Because they cannot unilaterally change their labels or product design to comply with state laws, it is impossible for them to satisfy both federal and state requirements, and thus federal law prevails.18

B. The Rise of Strategic Settlements and Antitrust Scrutiny

The unique litigation framework of Hatch-Waxman gave rise to a new and controversial commercial practice: the “reverse payment” or “pay-for-delay” settlement agreement. In these arrangements, a brand-name patent holder pays a generic challenger to abandon its patent litigation and agree to delay its market entry for a specified period.15 Critics argued these deals were anti-competitive, as they allowed a brand with a potentially weak patent to pay off the first challenger, thereby protecting its monopoly from both that challenger and all subsequent generics blocked by the first-filer’s 180-day exclusivity.42

FTC v. Actavis (2013)

This issue reached the Supreme Court in the landmark case FTC v. Actavis, Inc. The Court rejected both the prevailing “scope of the patent” test, which had largely immunized these settlements from antitrust law, and the Federal Trade Commission’s (FTC) argument that they should be deemed presumptively illegal.41 Instead, the Court charted a middle course, establishing that such settlements could be subject to antitrust scrutiny under the “rule of reason”.18 Justice Breyer’s majority opinion reasoned that a large and “unjustified” payment from the patentee to the alleged infringer could suggest that the parties were avoiding the risk of competition at the consumer’s expense.44 The decision opened the door for antitrust enforcement against these agreements, fundamentally altering the strategic calculus of patent settlements.

Post-Actavis Developments: What Constitutes a “Payment”?

A key question left open by Actavis was what forms of consideration, other than cash, could constitute a “payment.” The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit addressed this in King Drug Co. of Florence, Inc. v. SmithKline Beecham Corp. (2015). The court held that a “no-authorized generic” (no-AG) agreement—in which the brand company promises not to launch its own authorized generic version of the drug during the first-filer’s 180-day exclusivity period—could be a thing of “great monetary value” and thus qualify as a form of reverse payment subject to Actavis scrutiny.48 This decision broadened the scope of settlement terms that could trigger an antitrust challenge. Since

Actavis, the FTC has reported a significant decline in explicit cash reverse payments but has noted a corresponding increase in other forms of “possible compensation” that warrant continued scrutiny.52

C. Legislative Corrections: The Medicare Modernization Act of 2003 (MMA)

By the early 2000s, nearly two decades of experience with the Hatch-Waxman Act had revealed several loopholes that innovator companies were exploiting to delay generic competition. A common tactic was to list new patents in the Orange Book after a generic had already filed its ANDA, thereby triggering multiple, sequential 30-month stays and indefinitely postponing generic approval.6 Another issue was “parking,” where the first generic filer would settle with the brand and then decline to launch its product, using its 180-day exclusivity to block all other generics from the market.16

In response, Congress passed the Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act of 2003 (MMA), which included several key amendments to the Hatch-Waxman Act designed to close these loopholes 6:

- Single 30-Month Stay: The MMA limited the brand-name company to only one automatic 30-month stay per ANDA, which could only be triggered by patents that were listed in the Orange Book before the generic company filed its application.16

- 180-Day Exclusivity Reform: The Act reformed the 180-day exclusivity by changing its trigger from a “court decision” finding the patent invalid or not infringed to the date of the “first commercial marketing” of the generic drug. This change prevented the first filer from parking its exclusivity. The MMA also created several “forfeiture” provisions, under which the first filer would lose its exclusivity if it failed to obtain tentative approval or market its product within certain timeframes, or if it entered into an anti-competitive agreement.16

- Declaratory Judgment Actions: The MMA provided a new tool for generics. If a brand company received a Paragraph IV notice but chose not to file an infringement suit within the prescribed 45-day window, the generic applicant could now bring a declaratory judgment action in court to resolve the patent dispute.6

- Antitrust Filing Requirement: The MMA required that brand-generic patent settlement agreements be filed with the FTC and the Department of Justice, allowing for proactive antitrust review.16

| Case (Year) | Core Issue | Holding | Significance/Impact |

| Eli Lilly v. Medtronic (1990) | Scope of § 271(e)(1) “Safe Harbor” | The safe harbor from patent infringement for activities related to FDA submissions applies to medical devices, not just drugs.18 | Broadly interpreted the safe harbor, facilitating development for a wide range of regulated products. |

| Merck KGaA v. Integra (2005) | Scope of § 271(e)(1) “Safe Harbor” | The safe harbor protects all uses of patented inventions reasonably related to an FDA submission, including preclinical research.18 | Further expanded the scope of protected R&D activities for generic and biosimilar developers. |

| PLIVA v. Mensing (2011) | Federal Preemption of State Law | Federal law preempts state-law failure-to-warn claims against generic manufacturers due to their “duty of sameness” with the brand label.18 | Shielded generic firms from a significant area of tort liability, reinforcing their limited autonomy. |

| Caraco v. Novo Nordisk (2012) | Generic Counterclaims | Generic firms can sue to force a brand to correct an inaccurate or overly broad patent “use code” in the Orange Book.18 | Empowered generics to challenge improper Orange Book listings and facilitate “skinny label” market entry. |

| FTC v. Actavis (2013) | Antitrust Scrutiny of Settlements | “Pay-for-delay” or “reverse payment” settlements are not immune from antitrust law and must be evaluated under the “rule of reason”.18 | Subjected a key brand strategy for delaying generic entry to antitrust challenge, fundamentally changing settlement negotiations. |

| Mutual v. Bartlett (2013) | Federal Preemption of State Law | Federal law also preempts state-law design-defect claims against generic manufacturers due to the “duty of sameness”.18 | Broadened preemption protection for generic firms, confirming they cannot be compelled by state law to alter their products. |

Section V: The Unintended Consequences and Strategic Exploitation of Patent Exclusivity

While the Hatch-Waxman Act succeeded in its primary goal of fostering a generic drug market, its complex framework also created fertile ground for sophisticated and often controversial strategies by innovator companies to prolong their market monopolies. These strategies, which go far beyond the single patent term extension envisioned by the Act, have become central to the business model of the modern pharmaceutical industry and are the focus of intense policy debate.

A. The “Evergreening” Phenomenon: Lifecycle Management as a Business Model

“Evergreening,” a term often used by critics, or “lifecycle management,” as the industry prefers, refers to a wide array of tactics used to extend the period of market exclusivity for a drug, often by obtaining new, overlapping patents or regulatory exclusivities as the original protections near expiration.32 The goal is to create a continuous barrier to generic competition, effectively keeping the revenue stream from a successful product “evergreen”.57

Common evergreening tactics include:

- New Formulations: Developing and patenting minor modifications to an existing drug, such as an extended-release version that allows for once-daily dosing. While offering patient convenience, these new formulations may not provide a significant therapeutic advantage over the original product but can secure a new patent and a three-year regulatory exclusivity.55

- Chiral Switching: Many drugs are sold as “racemic mixtures,” containing equal parts of two mirror-image molecules called enantiomers. A common strategy is to isolate the single, more active enantiomer, patent it as a “new” drug, and market it just as the patent on the original mixture is expiring. This was the strategy behind the switch from omeprazole (Prilosec) to esomeprazole (Nexium).59

- New Delivery Systems: For combination products, particularly biologics, companies can obtain new patents on the delivery device—such as an auto-injector pen or a metered-dose inhaler—even after the patents on the active drug ingredient have expired. These device patents can then be used to block generic or biosimilar entry.61

- Combination Products: Patenting a new pill that combines a proprietary drug with another, often older and generic, drug can create a new product with its own period of exclusivity.62

The debate over these practices is polarized. Innovator companies and their defenders argue that these are legitimate, patentable improvements that enhance patient care, improve adherence, and represent valuable innovation.32 Critics, however, contend that they are often trivial tweaks designed primarily to thwart competition and maintain monopoly prices. They point to evidence showing that the vast majority of “new” patents granted are for existing drugs, not truly novel medicines, suggesting that the system incentivizes low-value modifications over breakthrough research.55

B. The Rise of the “Patent Thicket”

A more aggressive and legally complex strategy is the creation of a “patent thicket”—a dense web of dozens or even hundreds of overlapping patents covering a single drug product.66 These patents may cover not only the active ingredient but also manufacturing processes, formulations, methods of use for different diseases, and aspects of the delivery device.70

The strategic power of a patent thicket lies not in the strength of any single patent, but in the cumulative burden it imposes on a potential competitor. For a generic or biosimilar company to enter the market, it must navigate this dense web, challenging or designing around every potentially relevant patent. The sheer cost and complexity of litigating dozens of patents simultaneously can be a prohibitive barrier, effectively deterring challenges and delaying competition, even if many of the underlying patents are weak.70 This strategy is particularly effective for complex biologic drugs, which are regulated under the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act of 2009 (BPCIA).32 The BPCIA’s intricate patent dispute resolution process, known as the “patent dance,” can be leveraged by innovator companies to assert their thicket and create significant legal uncertainty for biosimilar developers.32

C. Case Studies in Lifecycle Management

The evolution of these strategies can be best understood through the examination of several iconic blockbuster drugs.

1. Lipitor (Atorvastatin): Evergreening and Authorized Generics

As the best-selling drug in history with peak annual sales exceeding $13 billion, Pfizer’s cholesterol-lowering medication Lipitor was the subject of an intense and multi-faceted lifecycle management strategy as its main patent expiration approached in 2011.38 Pfizer engaged in extensive patent litigation worldwide against generic challenger Ranbaxy, ultimately reaching a settlement that permitted generic entry in the U.S. on November 30, 2011.75 However, Pfizer deployed several other tactics to soften the impact of the patent cliff. It struck a deal with Watson Pharmaceuticals to launch an “authorized generic” (AG) version of Lipitor on the same day as Ranbaxy’s generic. The AG, being identical to the branded product, allowed Pfizer to directly compete in the generic market and significantly diluted the value of Ranbaxy’s 180-day first-filer exclusivity.78 Simultaneously, Pfizer aggressively marketed the branded product, offering deep rebates to insurers and pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) to keep Lipitor on preferred formulary tiers and launching the “Lipitor for You” program, which offered a $4 co-pay to patients, often making the brand cheaper than the generic.78 While Lipitor’s sales still fell dramatically—by nearly 60% in the year following generic entry—these strategies enabled Pfizer to retain hundreds of millions of dollars in additional profit.13

2. Humira (Adalimumab): The Quintessential Patent Thicket

AbbVie’s autoimmune drug Humira is the canonical example of a modern patent thicket.66 AbbVie built a massive U.S. patent estate around the drug, filing over 247 patent applications, with a staggering 89% of them filed

after Humira was first approved by the FDA in 2002.80 Independent analysis suggests that approximately 80% of these patents are “duplicative” or non-patentably distinct, linked together by legal instruments known as terminal disclaimers.67 This formidable legal fortress allowed AbbVie to delay the entry of biosimilar competitors in the U.S. until 2023, a full five years after biosimilars had launched in Europe, where the patent estate was far less dense.73 The economic impact of this delay has been immense, estimated to have cost the U.S. healthcare system tens of billions of dollars in excess spending.72 Over two-thirds of Humira’s cumulative U.S. sales were generated

after its primary patents had expired, demonstrating the profound commercial power of a well-constructed patent thicket.81

3. Nexium (Esomeprazole): The “Purple Pill” Chiral Switch

AstraZeneca’s strategy for its blockbuster heartburn medication Prilosec (omeprazole) exemplifies the “chiral switch” and “product hopping” tactics.60 Prilosec is a racemic mixture of two enantiomers. Just before Prilosec’s main patent expired, AstraZeneca patented and launched Nexium, which contained only the single S-isomer (esomeprazole).60 The company then launched a massive direct-to-consumer marketing campaign, branding Nexium as “the new purple pill” and implying its superiority to the older drug.82 This successfully transitioned a large portion of the patient base from Prilosec to the newly patented Nexium before generic omeprazole became widely available.60 Despite subsequent studies showing little to no significant clinical advantage of esomeprazole over omeprazole for most patients, the strategy was a resounding commercial success. Nexium became a multi-billion dollar blockbuster in its own right, effectively extending AstraZeneca’s monopoly in the proton-pump inhibitor market for another decade.60

| Drug (Company) | Core Strategy | Key Tactics | Outcome | ||

| Lipitor (Pfizer) | Market-Based Defense & Authorized Generic | – Strategic litigation and settlement 77 | – Launch of an authorized generic to dilute 180-day exclusivity 78 | – Deep rebates to PBMs and patient co-pay programs 79 | Softened the patent cliff, retaining significant revenue post-expiration despite a ~60% sales drop.13 |

| Humira (AbbVie) | Patent Thicket | – Amassed >247 patent applications, 89% filed post-approval 80 | – Created a dense web of overlapping and duplicative patents 70 | – Used the thicket to force settlements with biosimilar challengers 67 | Delayed U.S. biosimilar entry until 2023 (5 years after EU), costing the U.S. healthcare system billions.80 |

| Nexium (AstraZeneca) | Chiral Switch & Product Hopping | – Patented a single enantiomer (esomeprazole) of an older drug (omeprazole) 60 | – Aggressive direct-to-consumer marketing to imply superiority 82 | – Transitioned market share from the old drug to the new one before generic entry | Successfully extended market monopoly despite minimal therapeutic advantage, creating a new blockbuster drug.60 |

Section VI: Economic and Market Impact Analysis

The implementation of the Hatch-Waxman Act has had a profound and multifaceted economic impact, simultaneously creating a thriving generic market that has generated massive cost savings while also intensifying the financial pressures on innovator companies, which in turn has shaped their R&D and commercial strategies.

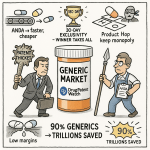

A. The Generic Revolution: Quantifying the Impact

By any measure, the Act’s primary goal of fostering generic competition has been an overwhelming success.

- Market Penetration: Prior to 1984, generic drugs constituted only 19% of prescriptions dispensed in the United States. Following the Act’s implementation, this figure has skyrocketed, with generics now accounting for over 90% of all prescriptions filled.2 The U.S. has become the world leader in generic drug utilization, a direct testament to the effectiveness of the ANDA pathway and other pro-competitive provisions of the Act.17

- Price Reduction and Cost Savings: The entry of generic competition into the market leads to dramatic and sustained price reductions. While the first generic entrant may only offer a modest discount, prices fall precipitously as more competitors enter. With four or more manufacturers, the generic price can fall by over 70% compared to the brand price; with a highly competitive market of 16 or more manufacturers, savings can approach 90%.84 This price competition has translated into staggering savings for the U.S. healthcare system. Over the last decade, generic drugs have saved the system nearly $3 trillion, with recent annual savings exceeding $400 billion.2 These savings benefit all payers, including federal programs like Medicare, commercial health plans, and individual patients through lower out-of-pocket costs.26

B. The “Patent Cliff”: Revenue Impact on Innovators

The direct corollary to the success of the generic market is the phenomenon known as the “patent cliff.” This term aptly describes the sharp, often catastrophic, decline in revenue that an innovator company experiences when a blockbuster drug loses its market exclusivity and faces an influx of low-cost generic competitors.74

- Scale and Magnitude: It is not uncommon for a brand-name drug to lose 80-90% of its revenue within the first year of generic entry.85 For companies heavily reliant on a single product, this represents an existential threat. The pharmaceutical industry is in a perpetual state of confronting this challenge; between 2025 and 2030, it is estimated that drugs representing $200 billion to $400 billion in annual revenue are at risk of losing patent protection.74

- Case Examples: The real-world impact of the patent cliff is stark. Pfizer’s Lipitor saw its annual sales plummet from $9.6 billion in 2011, the year before generic entry, to $3.9 billion in 2012.79 Eli Lilly’s antidepressant Prozac lost nearly 70% of its market share and $2.4 billion in annual sales shortly after its patent expired.88 More recently, AbbVie’s Humira, despite its defensive patent thicket, saw its sales fall by over 30% in the first nine months following the launch of biosimilars in the U.S. in 2023.85

The patent cliff is not merely a financial event; it has become the central organizing principle of the modern pharmaceutical business model. The existential threat posed by a 90% revenue loss is the primary driver behind the industry’s strategic decision-making. This immense pressure fuels a dual-track response. On one hand, it incentivizes legitimate, high-risk R&D to discover the next generation of blockbuster drugs that can replace the impending lost revenue.74 This aligns with the public interest in medical innovation. On the other hand, it creates a powerful incentive to engage in the aggressive and controversial lifecycle management strategies—evergreening, patent thickets, and strategic settlements—designed to defend existing revenue streams and postpone the cliff for as long as possible.38 This reveals a deep, structural paradox at the heart of the Hatch-Waxman framework: the very mechanism that delivers massive cost savings to the public (rapid and deep generic competition) is also the engine that drives the anti-competitive behaviors that are the subject of so much policy debate and litigation.

C. R&D Investment Trends: A Contested Narrative

The impact of the Hatch-Waxman Act on pharmaceutical innovation and R&D investment is a subject of ongoing and vigorous debate.

- The Pro-Innovation Argument: Proponents of the current system argue that the Act’s incentives have been highly effective. They point to the dramatic growth in industry R&D spending, which, adjusted for inflation, increased tenfold from the 1980s to $83 billion in 2019.90 The share of revenues devoted to R&D by pharmaceutical companies has also grown, averaging about one-quarter of net revenues in 2019, nearly double the share in 2000.90 Furthermore, the number of new drugs approved by the FDA has increased significantly, rising by 60% between 2010 and 2019 compared to the previous decade.90 Some economic analyses suggest that the increased competitive pressure from generics post-Hatch-Waxman actually spurred

greater R&D investment by innovator firms, as they sought to develop new, patent-protected products to replace those facing generic competition.89 - The Counter-Argument (Stifled Innovation): Critics contend that these raw spending figures are misleading and do not reflect a proportional increase in true, breakthrough innovation. They argue that the intense pressure of the patent cliff incentivizes companies to pursue lower-risk, less innovative R&D strategies focused on “evergreening” existing products rather than pursuing high-risk research into novel therapies for unmet medical needs.63 Evidence supports this view, with one study finding that 78% of newly issued drug patents were for modifications to existing drugs, not new medicines.65 This suggests that a significant portion of the increased R&D spending is directed toward building patent thickets and developing clinically marginal product improvements, rather than advancing the frontiers of science.84

| Drug (Company) | Peak Annual Sales (USD) | U.S. Patent Expiration Year | Post-Expiration Revenue Impact |

| Lipitor (Pfizer) | ~$13 Billion | 2011 | Sales plummeted by over 50% in the first year; worldwide revenues fell 59% from $9.5B in 2011 to $3.9B in 2012.85 |

| Plavix (BMS / Sanofi) | ~$9 Billion | 2012 | Experienced a significant and rapid drop in sales as multiple generic alternatives became available.85 |

| Humira (AbbVie) | ~$21.2 Billion | 2023 (effective biosimilar entry) | Sales fell 30.8% in the first nine months of 2023; a less severe drop than typical due to defensive strategies.85 |

| Keytruda (Merck) | ~$29.5 Billion (2023) | 2028 | Sales are projected to decline by 19% in the first year post-expiration, from $33.7B to $27.4B.85 |

| Eliquis (BMS / Pfizer) | >$10 Billion | ~2026-2028 | Facing a significant patent cliff that is a major strategic concern for the innovator companies.85 |

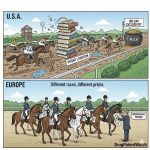

Section VII: A Global Perspective: Comparing U.S. PTE with the EU’s SPC System

The U.S. approach to compensating for regulatory delays is not the only model. A comparative analysis with the system used in the European Union—the Supplementary Protection Certificate (SPC)—provides valuable context and highlights the unique features and consequences of U.S. pharmaceutical patent policy.34

Distinct Frameworks, Similar Goals

Both the U.S. and the EU systems are designed to achieve the same fundamental goal: to restore a portion of the effective intellectual property protection for a medicinal product that is lost due to the lengthy time required for regulatory approval.34 However, they employ fundamentally different legal mechanisms to achieve this end. The U.S. uses a

Patent Term Extension (PTE), which, as its name implies, extends the term of an existing patent.36 The EU, by contrast, uses a

Supplementary Protection Certificate (SPC), which is not an extension of the patent itself but a separate, sui generis (unique in its characteristics) intellectual property right that takes effect only after the underlying patent has expired.34

Key Differences in Mechanics and Application

The divergence in the legal nature of these rights leads to several critical differences in their application and impact:

- Exclusivity Cap: While both systems provide a maximum extension of up to five years, their overall caps on market life differ. The U.S. PTE is limited by the 14-year cap, meaning the total patent term cannot exceed 14 years from the date of FDA approval.34 The EU SPC system is generally designed to provide a total period of effective market exclusivity (from the date of first marketing authorization) of up to 15 years.34

- Pediatric Extension: Both jurisdictions offer an additional six-month extension as an incentive for conducting pediatric studies. In the U.S., this is a separate “pediatric exclusivity” that attaches to other exclusivities.34 In the EU, it is a direct six-month extension of the SPC itself, granted for completing a Paediatric Investigation Plan (PIP).99

- Susceptibility to “Gaming” and Patent Thickets: The U.S. patent system, with its provisions for continuation applications and the high cost of litigation, is widely seen as more conducive to the creation of patent thickets.70 The European Patent Office (EPO) applies a stricter “added matter” doctrine, which makes it more difficult for applicants to expand the scope of their claims during prosecution and build large, overlapping families of duplicative patents from a single initial application.73 This structural difference in patent prosecution is a key reason why patent thickets are less prevalent and less dense in Europe.

- Manufacturing Waiver: A significant policy divergence is the EU’s “SPC manufacturing waiver”.97 Introduced in 2019, this provision allows EU-based manufacturers to produce a generic or biosimilar version of an SPC-protected medicine during the SPC’s term, provided the product is made exclusively for export to countries where no patent or SPC protection exists. It also allows for stockpiling during the final six months of the SPC term to facilitate a “Day 1” launch within the EU upon expiry.102 This pro-competitive measure, aimed at bolstering the EU’s generic manufacturing base, has no direct equivalent in the U.S. system.

Real-World Consequences

These legal and procedural differences have tangible, real-world consequences for market competition and patient access. The case of Humira is illustrative. AbbVie’s massive U.S. patent thicket, which was not replicable to the same extent under the stricter European patent system, was the primary reason that biosimilar versions of the drug launched in Europe in October 2018, more than four years before they became available to patients in the United States in January 2023.73 This multi-year delay in competition is estimated to have cost the American healthcare system billions of dollars in additional spending on the branded product.

| Feature | U.S. Patent Term Extension (PTE) | EU Supplementary Protection Certificate (SPC) |

| Enabling Legislation | Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984 | Council Regulation (EEC) No 1768/92 (now Reg 469/2009) |

| Nature of Right | An extension of the term of an existing patent.34 | A new, separate sui generis IP right that takes effect after the patent expires.34 |

| Administering Body | USPTO (in coordination with FDA).34 | National patent offices of member states; new centralized procedure via EUIPO emerging.101 |

| Maximum Extension | Up to 5 years.34 | Up to 5 years.34 |

| Total Exclusivity Cap | Total patent term cannot exceed 14 years from FDA approval.34 | Total market exclusivity (patent + SPC) generally aims for 15 years from first marketing authorization.34 |

| Pediatric Extension | Additional 6 months of exclusivity (not a direct PTE extension).34 | Additional 6 months added directly to the SPC term.99 |

| Filing Deadline | Within 60 days of regulatory approval.34 | Within 6 months of marketing authorization or patent grant (whichever is later).102 |

| Scope of Protection | Limited to the approved product for its approved indication(s) during the extended term.29 | Protects the “product” (active ingredient or combination) covered by the marketing authorization.99 |

| Multiple Patents/Products | Only one patent can be extended per approved product.35 | Only one SPC can be granted per product, based on the first marketing authorization.102 |

| Manufacturing Waiver | None. Manufacturing for any purpose during the patent term is infringement. | Yes. Allows manufacturing during the SPC term for export and for stockpiling for Day 1 EU launch.97 |

Section VIII: The Future of Pharmaceutical Patent Policy

Forty years after its passage, the Hatch-Waxman Act remains the central framework governing pharmaceutical competition in the United States. However, the system is in a constant state of flux, subject to ongoing scrutiny and reform efforts from all branches of government. The core tension between incentivizing innovation and promoting affordability is as acute as ever, and the debate over whether the “grand bargain” remains balanced continues to drive policy discussions.

A. Current Controversies and Proposed Reforms (2024-2025)

Recent years have seen a flurry of activity aimed at recalibrating the Hatch-Waxman system and curbing perceived abuses of the patent system.

- FTC Scrutiny of Orange Book Listings: The Federal Trade Commission has adopted a more aggressive enforcement posture, challenging what it deems “improper” Orange Book listings as potential violations of antitrust law.103 In 2023 and 2024, the agency challenged hundreds of patents, particularly those covering drug delivery devices rather than active ingredients, arguing that such listings can unlawfully deter generic competition.104 This represents a significant shift from the historical deference granted to innovator companies in their listing decisions.

- The “Skinny Label” Debate: The viability of the “skinny label” strategy—where a generic carves out a patented use from its label to avoid infringement—has been thrown into uncertainty by court decisions that have found generics liable for “induced infringement” if doctors prescribe the generic for the patented use. This has prompted legislative proposals, such as the “Skinny Labels, Big Savings Act,” which aim to provide a clearer safe harbor for generics employing this pro-competitive strategy.103

- USPTO Reform Efforts: The U.S. Patent and Trademark Office has also taken administrative steps to address concerns about patent quality and strategic patenting. The agency has proposed and implemented significant fee increases for filing continuation applications and for seeking patent term extensions, measures aimed at discouraging the proliferation of large, low-quality patent families.105 The USPTO has also proposed new rules regarding the use of terminal disclaimers, a legal tool frequently used in the construction of patent thickets, which would limit the enforceability of patents tied to another patent that has been invalidated.104

- Broader Legislative Proposals: Congress continues to consider a range of legislative reforms. Some, like the PREVAIL Act, are viewed as pro-innovator, as they would make it more difficult for third parties to challenge the validity of patents at the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB).106 Other proposals take direct aim at evergreening and patent thickets, for example, by creating a presumption that only one or two patents beyond the initial patent on the active ingredient are legitimate, or by prohibiting the enforcement of multiple patents linked by terminal disclaimers.107

- The Post-Chevron World: A major development with potentially far-reaching consequences is the Supreme Court’s 2024 decision in Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo, which overturned the long-standing Chevron deference doctrine.108 This doctrine had required courts to defer to a federal agency’s reasonable interpretation of an ambiguous statute. Its demise means that courts will now have more power to substitute their own judgment for that of agencies like the FDA and the USPTO when interpreting the complex provisions of the FD&C Act and the Patent Act. This could lead to increased litigation and uncertainty regarding many of the regulatory interpretations that have underpinned the Hatch-Waxman framework for decades.108

B. The Enduring Tension: Is the Grand Bargain Still Balanced?

Forty years on, there is no consensus on the state of the Hatch-Waxman Act’s grand bargain. The perspectives remain deeply divided.

- The Innovator Perspective: From this viewpoint, the system is fundamentally working as intended. The incentives for innovation, including patent term extension and regulatory exclusivities, are essential to justify the enormous cost and risk of modern drug development, especially in the face of the severe patent cliff that follows exclusivity loss.105 Practices labeled pejoratively as “evergreening” are, in fact, the legitimate patenting of valuable follow-on innovations that improve patient outcomes and convenience.32 Proponents argue that the focus on patents as a driver of high drug prices is misplaced, and that the real market distortions lie elsewhere, such as in the rebate system controlled by pharmacy benefit managers.17

- The Generic/Public Interest Perspective: This perspective holds that the system’s balance has been dangerously tilted in favor of innovators. Loopholes in the law have been systematically exploited to create anti-competitive patent thickets and to delay generic entry far beyond the period “reasonably contemplated” by the Act’s drafters.1 This gaming of the system comes at an enormous cost to patients, employers, and government payers, who are forced to pay monopoly prices for years longer than necessary.64 From this view, significant reform is needed to restore the Act’s pro-competitive intent.109

Ultimately, the Hatch-Waxman Act remains, as one analysis described it, a “convoluted and expensive approach to balancing innovation and competition”.7 It has been remarkably successful in achieving its goal of creating a generic market, yet it has simultaneously spawned a multi-billion-dollar industry of legal and regulatory gamesmanship. The core tension between rewarding invention and ensuring access is unresolved. The “balance” of the grand bargain is not a fixed point but a constantly shifting equilibrium, perpetually recalibrated by the strategic actions of industry and the reactive interventions of courts, Congress, and administrative agencies. The future of pharmaceutical patent policy is unlikely to involve a complete overhaul of this foundational law. Instead, it will likely be characterized by continued, targeted reforms as policymakers and stakeholders continue to grapple with the system’s manifest successes and its profound, persistent flaws.

Conclusion and Recommendations

The 1984 Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act was a transformative piece of legislation that successfully addressed the dual market failures of the pre-1984 era. It unleashed the power of generic competition, resulting in trillions of dollars in healthcare savings and dramatically improving access to affordable medicines for millions of Americans. Simultaneously, it provided innovator companies with new forms of exclusivity and a mechanism to restore patent life, preserving the vital incentives for investment in pharmaceutical R&D.

However, this analysis demonstrates that the Act’s intricate framework, born of compromise, also created a new competitive paradigm. The very success of the generic market created the “patent cliff,” a powerful economic force that incentivized innovator firms to evolve beyond single-patent protection and develop sophisticated, aggressive, and often controversial strategies—from evergreening and product hopping to the construction of formidable patent thickets—to extend their market monopolies. The past four decades have been defined by a continuous strategic cat-and-mouse game, with industry exploiting ambiguities and loopholes in the law, and with the judiciary, Congress, and regulatory agencies attempting to patch the framework and re-establish the Act’s intended balance. The grand bargain of 1984 is not a settled pact but an ongoing negotiation, constantly being redefined on the battlefields of the courtroom, the halls of Congress, and the offices of the FDA and USPTO.

To better align the realities of the 21st-century pharmaceutical market with the original goals of the Hatch-Waxman Act, the following recommendations are proposed:

- For Policymakers:

- Address Patent Thickets Legislatively: Consider targeted legislation that creates a rebuttable presumption against the validity of patents in a thicket beyond a certain number for a single drug. This would shift the burden of proof to the innovator to demonstrate the distinct patentability of each patent in an excessively large portfolio.

- Raise the Standard for Follow-On Patents: Amend patent law to require a heightened standard of non-obviousness or a demonstrated significant clinical advantage for follow-on patents, such as new formulations or enantiomers, to be granted.

- Explore a U.S. Manufacturing Waiver: Commission a study on the economic and competitive impact of implementing a U.S. equivalent of the EU’s manufacturing waiver to bolster domestic generic manufacturing and allow U.S. firms to compete in global markets during a PTE period.

- For Regulators (USPTO/FDA):

- Enhance Inter-Agency Scrutiny: Formalize and strengthen the collaboration between the USPTO and the FDA to scrutinize patent applications that appear to be part of an evergreening strategy. The USPTO should have access to FDA expertise to assess the claimed therapeutic significance of follow-on inventions.

- Continue Administrative Reforms: Vigorously pursue and enforce administrative reforms aimed at curbing patent system abuse, including the FTC’s challenges to improper Orange Book listings and the USPTO’s rules on terminal disclaimers and continuation practice.

- For the Judiciary:

- Apply Robust Antitrust Scrutiny: Continue to apply a robust and flexible “rule of reason” analysis to patent settlement agreements under the FTC v. Actavis precedent. Courts should remain skeptical of complex or non-cash arrangements that have the practical effect of a large, unjustified reverse payment.

- For Industry Stakeholders:

- Innovator Firms: Realign R&D priorities toward true, high-value innovation for unmet medical needs. While lifecycle management is a valid business practice, over-reliance on low-value evergreening strategies erodes public trust and invites stricter regulation. Long-term sustainability depends on a pipeline of genuinely novel products, not just a fortress of defensive patents.

- Generic and Biosimilar Firms: Continue to serve as the primary police force of the patent system. Strategic Paragraph IV challenges are not just a business opportunity; they are the most effective mechanism for invalidating weak patents, dismantling patent thickets, and ensuring that the grand bargain delivers on its promise of timely, affordable access to medicine.

Works cited

- Patent Term Extensions and the Last Man Standing | Yale Law & Policy Review, accessed August 7, 2025, https://yalelawandpolicy.org/patent-term-extensions-and-last-man-standing

- Paving the Way for Generics: How Hatch-Waxman Changed the Industry, accessed August 7, 2025, https://knowledgewebcasts.com/paving-the-way-for-generics-how-hatch-waxman-changed-the-industry/

- Abuse of the Hatch-Waxman Act: Mylan’s Ability to Monopolize Reflects Weaknesses – BrooklynWorks, accessed August 7, 2025, https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/bjcfcl/vol11/iss2/12/

- Reining in Patent Term Extensions for Related Pharmaceutical Products Post-Photocure and Ortho-McNeil – Scholarly Commons, accessed August 7, 2025, https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1107&context=nulr

- Abuse of the Hatch-Waxman Act: Mylan’s Ability to Monopolize Reflects Weaknesses – BrooklynWorks, accessed August 7, 2025, https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1241&context=bjcfcl

- The balance between innovation and competition: the Hatch …, accessed August 7, 2025, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24505856/

- Patents, Innovation, and Competition in Pharmaceuticals: The Hatch-Waxman Act after 40 Years – American Economic Association, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/jep.20241423

- The Hatch-Waxman (Im)Balancing Act – Harvard DASH, accessed August 7, 2025, http://dash.harvard.edu/bitstream/handle/1/10015297/Paper1.html?sequence=2

- Hatch-Waxman Turns 30: Do We Need a Re-Designed Approach for the Modern Era? – Yale Law School Legal Scholarship Repository, accessed August 7, 2025, https://openyls.law.yale.edu/bitstream/handle/20.500.13051/5929/Kesselheim_2.pdf

- Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act – Corporate Counsel – FindLaw, accessed August 7, 2025, https://corporate.findlaw.com/intellectual-property/drug-price-competition-and-patent-term-restoration-act.html

- THE HATCH-WAXMAN ACT: HISTORY, STRUCTURE, AND LEGACY – HeinOnline, accessed August 7, 2025, https://heinonline.org/hol-cgi-bin/get_pdf.cgi?handle=hein.journals/antil71§ion=23

- gaming the hatch-waxman system: how pioneer drug makers exploit the law to maintain monopoly power in the prescription drug market, accessed August 7, 2025, https://scholarship.law.nd.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1104&context=jleg&httpsredir=1&referer

- Patent cliff and strategic switch: exploring strategic design possibilities in the pharmaceutical industry – PMC, accessed August 7, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4899342/

- 40th Anniversary of the Generic Drug Approval Pathway – FDA, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/cder-conversations/40th-anniversary-generic-drug-approval-pathway

- The Hatch-Waxman Act: A Primer – EveryCRSReport.com, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.everycrsreport.com/reports/R44643.html

- The Hatch-Waxman Act: A Quarter Century Later – UM Carey Law, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www2.law.umaryland.edu/marshall/crsreports/crsdocuments/R41114_03132013.pdf

- 40 Years of Hatch-Waxman: How does the Hatch-Waxman Act help patients? | PhRMA, accessed August 7, 2025, https://phrma.org/blog/40-years-of-hatch-waxman-how-does-the-hatch-waxman-act-help-patients

- Hatch-Waxman Practice in the Supreme Court of … – Winston & Strawn, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.winston.com/a/web/114242/Chapter-21-ABA-ANDA-Litigation-Strategies-and-Tactics-for-Phar.pdf

- Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act – Wikipedia, accessed August 7, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Drug_Price_Competition_and_Patent_Term_Restoration_Act

- S.2748 – 98th Congress (1983-1984): A bill to amend the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act to revise the procedures for new drug applications and to amend title 35, United States Code, to authorize the extension of the patents for certain regulated products, and for other purposes. | Congress.gov, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.congress.gov/bill/98th-congress/senate-bill/2748

- The Hatch-Waxman Act: encouraging innovation and generic drug competition – PubMed, accessed August 7, 2025, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20615183/

- Hatch-Waxman Letters – FDA, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/abbreviated-new-drug-application-anda/hatch-waxman-letters

- What is Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984? Simple Definition & Meaning – LSD.Law, accessed August 7, 2025, https://lsd.law/define/drug-price-competition-and-patent-term-restoration-act-of-1984

- Hatch-Waxman Overview | Axinn, Veltrop & Harkrider LLP, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.axinn.com/en/insights/publications/hatch-waxman-overview

- A Comparative Overview of Generic Drug Regulation in US, Europe, Australia and India, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.ijdra.com/index.php/journal/article/download/747/396

- The Impact of Generic Drugs on Healthcare Costs – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-impact-of-generic-drugs-on-healthcare-costs/

- H.R.3605 – 98th Congress (1983-1984): Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.congress.gov/bill/98th-congress/house-bill/3605

- 40 Years of Hatch-Waxman: What is the Hatch-Waxman Act? | PhRMA, accessed August 7, 2025, https://phrma.org/blog/40-years-of-hatch-waxman-what-is-the-hatch-waxman-act

- Patent Term Extension – Sterne Kessler, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.sternekessler.com/news-insights/insights/patent-term-extension/

- Pharmaceutical Patent Term Extensions: A Brief Explanation – Every CRS Report, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.everycrsreport.com/reports/RS21129.epub

- Hatch-Waxman 101 – Fish & Richardson, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.fr.com/insights/thought-leadership/blogs/hatch-waxman-101-3/

- Pharmaceutical Patenting Practices: A Legal Overview – Congress.gov, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/IF11561

- Hatch-Waxman Act – Westlaw, accessed August 7, 2025, https://content.next.westlaw.com/Glossary/PracticalLaw/I2e45aeaf642211e38578f7ccc38dcbee

- Understanding Patent Term Extensions: An Overview …, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/understanding-patent-term-extensions-an-overview/

- Pharmaceutical Patent Term Extension: An Overview – Alacrita, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.alacrita.com/whitepapers/pharmaceutical-patent-term-extension-an-overview

- Understanding Patent Term Extensions in Different Countries – PatentPC, accessed August 7, 2025, https://patentpc.com/blog/understanding-patent-term-extensions-in-different-countries

- The New Frontier of Market Exclusivity: Maximizing Drug Patent Life Beyond the Molecule, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/patent-term-extension-for-drugs-not-limited-to-new-chemical-entities/

- Managing the challenges of pharmaceutical patent expiry: a case study of Lipitor, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/309540780_Managing_the_challenges_of_pharmaceutical_patent_expiry_a_case_study_of_Lipitor

- Hatch-Waxman Act | Legal Information Institute – Law.Cornell.Edu, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.law.cornell.edu/category/keywords/hatch-waxman_act

- SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES, accessed August 7, 2025, https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/564/09-993/index.pdf

- Federal Trade Commission v. Actavis Inc 570 U.S. 136 Supreme Court (2013) Prepared by UNCTAD’s Intellectual Property Unit Su, accessed August 7, 2025, https://unctad.org/ippcaselaw/sites/default/files/ippcaselaw/2020-12/FTC%20v.%20Actavis%20570%20U.S.%20Supreme%20Court%20%282013%29.pdf

- FTC v. Actavis, Inc. – Wikipedia, accessed August 7, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/FTC_v._Actavis,_Inc.

- Federal Trade Commission v. Actavis – SCOTUSblog, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.scotusblog.com/cases/case-files/federal-trade-commission-v-watson-pharmaceuticals-inc/

- FTC v. Actavis Inc. – Oyez, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.oyez.org/cases/2012/12-416

- A Decade of FTC v. Actavis: The Reverse Payment Framework Is Older, But Are Courts Wiser in Applying It? – American Bar Association, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/publications/antitrust/journal/86/issue-2/decade-of-ftc-v-actavis.pdf

- Anticompetitive Patent Settlements and the Supreme Court’s Actavis Decision, accessed August 7, 2025, https://scholarship.law.upenn.edu/faculty_scholarship/1844/

- 235 Win, Lose, or Draw? A Decade of Pharma Antitrust Since FTC vs. Actavis, accessed August 7, 2025, https://ourcuriousamalgam.com/episode/235-pharma-antitrust-ftc-actavis/

- WHY THE SUPREME COURT SHOULD DENY CERTIORARI IN KING DRUG, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.competitionpolicyinternational.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/CPI-Special-Feature-Carrier-September-FINAL.pdf

- King Drug Co. of Florence, Inc. v. SmithKline Beecham Corp. (3rd Cir. 2015) – Patent Docs, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.patentdocs.org/2015/07/king-drug-co-of-florence-inc-v-smithkline-beecham-corp-3rd-cir-2015.html

- King Drug Co. of Florence v. Smithkline Beecham Corp., No. 14-1243 (3d Cir. 2015), accessed August 7, 2025, https://law.justia.com/cases/federal/appellate-courts/ca3/14-1243/14-1243-2015-06-26.html

- SmithKline Beecham Corp. v. King Drug Co. of Florence, Inc. – SCOTUSblog, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.scotusblog.com/cases/case-files/smithkline-beecham-corp-v-king-drug-co-of-florence-inc/

- Then, now, and down the road: Trends in pharmaceutical patent settlements after FTC v. Actavis, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.ftc.gov/enforcement/competition-matters/2019/05/then-now-down-road-trends-pharmaceutical-patent-settlements-after-ftc-v-actavis

- The Balance Between Innovation and Competition: The Hatch-Waxman Act, the 2003 Amendments, and Beyond – DASH (Harvard), accessed August 7, 2025, https://dash.harvard.edu/bitstreams/7312037c-94cf-6bd4-e053-0100007fdf3b/download

- Changes to Hatch-Waxman.indd – Alston & Bird, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.alston.com/-/media/files/insights/publications/2004/03/ilife-sciences-advisoryi-changes-to-hatchwaxman-un/files/changes-to-hatchwaxman/fileattachment/changes-to-hatchwaxman.pdf

- Does Drug Patent Evergreening Prevent Generic Entry …, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/does-drug-patent-evergreening-prevent-generic-entry/

- Pharmaceutical Patents and Evergreening (VIII) – The Cambridge …, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/cambridge-handbook-of-investmentdriven-intellectual-property/pharmaceutical-patents-and-evergreening/9A97A3E6D258E9A47DCF88E5EA495F44

- The Evergreening Myth | Cato Institute, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.cato.org/regulation/fall-2020/evergreening-myth

- The “Evergreening” Metaphor in Intellectual Property Scholarship – IdeaExchange@UAkron, accessed August 7, 2025, https://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2510&context=akronlawreview

- Patent protection strategies – PMC, accessed August 7, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3146086/

- A case study of AstraZeneca’s omeprazole/esomeprazole chiral switch strategy – GaBIJ, accessed August 7, 2025, https://gabi-journal.net/a-case-study-of-astrazenecas-omeprazole-esomeprazole-chiral-switch-strategy.html

- Is Patent “Evergreening” Restricting Access to Medicine/Device Combination Products?, accessed August 7, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4766186/

- The Billion-Dollar Equation: Mastering Patent Term Extension to Secure Market Dominance, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/calculating-the-regulatory-review-period-for-patent-term-extension/

- Drug patents: the evergreening problem – PMC, accessed August 7, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3680578/

- Patent Database Exposes Pharma’s Pricey “Evergreen” Strategy – UC Law SF, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.uclawsf.edu/2020/09/24/patent-drug-database/

- May your drug price be evergreen | Journal of Law and the Biosciences – Oxford Academic, accessed August 7, 2025, https://academic.oup.com/jlb/article/5/3/590/5232981

- In the Thick(et) of It: Addressing Biologic Patent Thickets Using the Sham Exception to Noerr-Pennington, accessed August 7, 2025, https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/iplj/vol33/iss3/5/

- Patent Settlements Are Necessary To Help Combat Patent Thickets, accessed August 7, 2025, https://accessiblemeds.org/resources/blog/patent-settlements-are-necessary-to-help-combat-patent-thickets/

- In the Thick(et) of It: Addressing Biologic Patent Thickets Using the Sham Exception to Noerr-Pennington, accessed August 7, 2025, https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1826&context=iplj

- COMPETING WITH PATENT THICKETS: ANTITRUST LAW’S ROLE IN PROMOTING BIOSIMILARS – Boston University, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.bu.edu/bulawreview/files/2022/03/HUSTAD.pdf

- Biological patent thickets and delayed access to biosimilars, an American problem – PMC, accessed August 7, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9439849/

- The Dark Reality of Drug Patent Thickets: Innovation or Exploitation? – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-dark-reality-of-drug-patent-thickets-innovation-or-exploitation/

- Patent thickets are pricing Americans out of medicine – FREOPP, accessed August 7, 2025, https://freopp.org/oppblog/patent-thickets-are-pricing-americans-out-of-medicine/