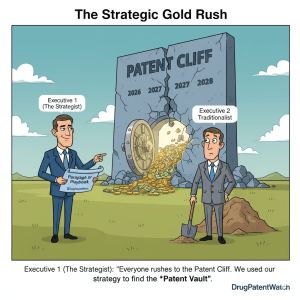

Welcome to the high-stakes world of generic pharmaceuticals. If you believe this industry is simply about replicating molecules and selling them cheap, you’re already at a disadvantage. The reality is far more complex, more strategic, and infinitely more fascinating. This isn’t just a marketplace; it’s a battlefield where legal acumen, regulatory finesse, and commercial audacity determine victory. The spoils of this war are staggering. Over the past decade, generic and biosimilar medicines have saved the U.S. healthcare system an estimated $3.1 trillion, with a breathtaking $445 billion in savings in 2023 alone.1 This colossal transfer of value is driven by a recurring phenomenon known as the “patent cliff,” a period where blockbuster drugs lose their market exclusivity, unleashing a torrent of competition. In the coming years, we are poised to witness one of the largest cliffs in history, with over $200 billion in branded drug sales set to go off-patent.1

This is the generic gold rush. But make no mistake, success is not guaranteed. Launching a generic drug isn’t just about hitting the market—it’s about dominating it. You’re stepping into an arena where timing is everything, pricing is a weapon, and perception can make or break your launch. The very term “generic” is a misnomer in a strategic context. While the molecules may be copies, the strategies to bring them to market are unique, innovative, and often more intricate than the original brand’s launch campaign. The true innovation in this space lies not in the R&D of the molecule, but in the R&D of the strategy to overcome formidable brand defenses and secure market access. This report is your playbook. We will deconstruct the three foundational pillars of a successful generic launch—regulatory mastery, legal strategy, and commercial execution. Then, we will dive deep into three of the most consequential generic launches in pharmaceutical history: the takedown of the world’s best-selling drug, atorvastatin (Lipitor); the battle over value and access for the life-saving cancer treatment, imatinib (Gleevec); and the high-stakes gamble of an “at-risk” launch for the blood thinner, clopidogrel (Plavix). These are not just historical accounts; they are living case studies packed with actionable intelligence. Our goal is to equip you, the strategic decision-maker, with the nuanced understanding required to turn patent data, regulatory pathways, and market intelligence into a decisive and durable competitive advantage. Let’s begin.

Part I: The Blueprint for Generic Success – Mastering the Three Pillars of Market Entry

Before we dissect the landmark battles that have defined the generic landscape, we must first understand the fundamental principles of engagement. A successful generic launch is not the result of a single brilliant move but the flawless execution of a multi-year strategy built upon three non-negotiable pillars: navigating the complex regulatory gauntlet, mastering the legal chess match of patent law, and executing a razor-sharp commercial playbook. Neglect any one of these, and you risk turning a potential blockbuster into a costly failure.

Pillar 1: Navigating the Regulatory Gauntlet – From Bioequivalence to cGMP

The journey of every generic drug begins not in a courtroom or a marketing meeting, but in the meticulous world of regulatory science. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and its global counterparts are the ultimate gatekeepers. Gaining their approval is the price of entry, and achieving it with speed and precision is the first major competitive advantage you can secure. Regulatory compliance is not a passive, check-the-box activity; it is an active, strategic weapon. A flawless, first-cycle approval of your Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) can shave months off your launch timeline, maximizing the value of the lucrative 180-day exclusivity window and leaving slower competitors in your wake. Conversely, delays caused by incomplete data, failed bioequivalence studies, or manufacturing compliance issues can be catastrophic, ceding the first-mover advantage and millions in revenue to a rival.

The ANDA Pathway: More Than Just an Abbreviation

The cornerstone of the generic drug approval process in the United States is the Abbreviated New Drug Application, or ANDA.5 Established by the landmark Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984, the ANDA process is what makes the modern generic industry possible.6 The application is “abbreviated” because it allows a generic manufacturer to rely on the FDA’s previous finding that the brand-name drug, or Reference Listed Drug (RLD), is safe and effective.5 This critical provision means generic companies do not need to conduct their own costly and duplicative preclinical and clinical trials, dramatically lowering the barrier to market entry.5

However, “abbreviated” does not mean simple. An ANDA is a comprehensive submission that must scientifically prove to the FDA that the generic product is, for all intents and purposes, the same as the brand-name drug it references.8 The core requirements are stringent and multifaceted:

- Same Active Ingredient: The generic must contain the identical active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) as the brand.

- Pharmaceutical Equivalence: The product must be of the same dosage form (e.g., tablet, injectable), route of administration, and strength as the RLD.5

- Bioequivalence: This is the scientific heart of the ANDA. The generic manufacturer must demonstrate through rigorous studies that its product delivers the same amount of active ingredient into a patient’s bloodstream in the same amount of time as the brand drug.5

- Identical Labeling: The drug information label for the generic must be the same as the brand-name drug’s label, with only minor permissible differences.8

- Manufacturing Excellence: The applicant must prove that its manufacturing methods and facilities adhere to the FDA’s strict Current Good Manufacturing Practices (cGMP). This ensures the drug can be produced correctly, consistently, and safely on a commercial scale. The FDA often verifies this through on-site facility inspections before granting approval.8

The submission itself is a massive undertaking, requiring exhaustive data on chemistry, manufacturing, and controls (CMC), detailed results from bioequivalence studies, and stability data proving the drug does not break down over time.4 A typical ANDA review by the FDA takes around 10 to 12 months, but this timeline can easily stretch to 18 months or longer if the initial submission is incomplete or contains deficiencies that require multiple review cycles. In 2023, a notable 15% of ANDAs were rejected by the FDA due to incomplete data, underscoring the critical importance of meticulous preparation.

The Science of “Sameness”: The Crucial Hurdle of Bioequivalence (BE)

Of all the requirements in an ANDA, proving bioequivalence (BE) is the most significant scientific challenge and the highest hurdle to overcome. It is the linchpin that connects the generic product to the brand’s established record of safety and efficacy. The FDA’s definition is precise: bioequivalence means there is no significant difference in the rate and extent to which the active ingredient becomes available at the site of drug action when administered at the same dose under similar conditions.

For most systemically acting oral drugs, this is demonstrated through in vivo pharmacokinetic (PK) studies. These studies typically involve administering both the generic (test) drug and the brand (reference) drug to a group of 24 to 36 healthy volunteers in a crossover design, then drawing blood samples at regular intervals.4 The analysis focuses on two key parameters:

- Cmax (Maximum Concentration): The peak concentration of the drug in the bloodstream, which reflects the rate of absorption.

- AUC (Area Under the Curve): The total exposure to the drug over time, which reflects the extent of absorption.

To be deemed bioequivalent, the 90% confidence interval for the ratio of the geometric means (Test/Reference) for both Cmax and AUC must fall within the narrow range of 80.00% to 125.00%. This statistical standard ensures that any minor differences between the two products are not clinically significant.

The challenge lies in achieving this “sameness” without access to the innovator’s proprietary formulation data. Generic formulators are essentially reverse-engineering a product. They know the active ingredient, but the specific mix of inactive ingredients, or excipients, and the manufacturing process variables can have a profound impact on how a drug dissolves and is absorbed by the body. A formulation that appears identical on paper may fail a BE study, forcing the company back to the drawing board for a costly and time-consuming reformulation effort.

This challenge is magnified exponentially for complex generics. While a simple oral tablet has a relatively straightforward path, products like topical creams, transdermal patches, metered-dose inhalers, or long-acting injectables present formidable scientific hurdles.1 For these products, standard blood-level PK studies may not be feasible or relevant.

- Locally Acting Drugs: For a topical cream applied to the skin or an inhaled corticosteroid delivered to the lungs, the site of action is local, and systemic blood levels may be negligible or uncorrelated with efficacy. Proving BE for these products may require alternative methods like pharmacodynamic (PD) studies (measuring a biological response, like skin blanching for a steroid cream) or, in the most difficult cases, full-blown clinical endpoint studies.

- Complex Formulations: A transdermal patch must not only deliver the drug at the same rate and extent but also demonstrate equivalent skin adhesion and irritation profiles. An inhaler is a complex drug-device combination, and the generic must prove equivalent performance across a range of patient inhalation flow rates.

These complex studies, particularly clinical endpoint trials, can add millions of dollars ($2–6 million or more) and years to the development timeline, with a significantly higher risk of failure. This reality acts as a major economic deterrent, meaning many complex drugs face little to no generic competition, a key reason why the FDA’s Generic Drug User Fee Amendments (GDUFA) program has prioritized research to develop more efficient BE methods for these products.7

Table 1: The Blueprint for a Generic Blockbuster: Key Regulatory and Legal Milestones

| Phase | Key Activities | Critical Checkpoints | Strategic Considerations |

| Phase 1: Pre-Development & Opportunity Selection (Years -5 to -3) | – Monitor patent expirations and exclusivities using platforms like DrugPatentWatch. – Conduct market research to identify high-value targets ($>1B brand sales). – Analyze competitive landscape (number of potential filers). – Perform initial “freedom-to-operate” (FTO) analysis on brand’s patent estate. | – Is the market size sufficient to justify investment? – Is the patent landscape challengeable? – Do we have the technical capability for formulation and manufacturing? | – Prioritize “first-to-file” (FTF) opportunities for 180-day exclusivity. – Assess risk of “patent thickets” and “evergreening” strategies. |

| Phase 2: Formulation & ANDA Preparation (Years -3 to -1) | – Reverse-engineer the Reference Listed Drug (RLD). – Develop and test multiple formulations. – Conduct pivotal bioequivalence (BE) studies. – Compile comprehensive Chemistry, Manufacturing, and Controls (CMC) data. – Prepare and finalize the full ANDA submission in eCTD format. | – Successful BE study outcome (90% CI within 80-125%). – All manufacturing processes are cGMP compliant. – ANDA dossier is complete and error-free to ensure first-cycle review. | – Invest in Quality by Design (QbD) to minimize BE study failures. – Engage with FDA early for complex generics to align on BE study design. |

| Phase 3: ANDA Filing & Patent Challenge (Year -1 to Launch) | – Submit ANDA to FDA with a Paragraph IV (P-IV) certification. – Send P-IV notice letter to brand and patent holders within 20 days of FDA acceptance. – Prepare for patent infringement lawsuit from brand owner. | – FDA acceptance of ANDA filing. – Brand files suit within 45 days, triggering the 30-month stay. – Secure FTF status for 180-day exclusivity. | – A P-IV filing is an “artificial act of infringement” and a declaration of intent. – The 30-month stay provides a defined window for litigation. |

| Phase 4: Litigation & Pre-Launch (During 30-Month Stay) | – Engage in patent litigation (discovery, depositions, trial). – Explore potential settlement agreements (beware of antitrust scrutiny). – Scale up manufacturing and secure API supply chain. – Develop commercial launch plan (pricing, marketing, payer engagement). | – Favorable court ruling (patent invalid/not infringed) or settlement. – FDA grants tentative approval pending patent resolution. – All commercial and supply chain elements are ready for “Day 1” launch. | – Litigation is a calculated business risk; success rates for FTF challengers are high (~76%). – Prepare for brand defense tactics like “authorized generics.” |

| Phase 5: Launch & Post-Launch (Day 1 Onward) | – Launch product immediately upon final FDA approval and patent clearance. – Execute pricing strategy (modest discount during exclusivity, aggressive post-exclusivity). – Monitor market uptake, sales data, and competitor actions. – Manage pharmacovigilance and post-market safety reporting. | – Achieve target market share within the first 6 months. – Maintain supply chain integrity and avoid stock-outs. – Adhere to all post-marketing regulatory commitments. | – The first mover captures a dominant and persistent market share. – Be prepared to dynamically adjust pricing as more competitors enter the market (“Day 181”). |

Pillar 2: The Legal Chess Match – Winning the Hatch-Waxman Game

If the regulatory process is the scientific foundation of a generic launch, the legal strategy is its sharp-edged sword. The pharmaceutical patent landscape is not a serene park but a fiercely contested territory governed by a single, monumental piece of legislation: the Hatch-Waxman Act. Understanding its intricacies is not just a task for your legal department; it is a C-suite imperative. The Paragraph IV challenge process is the central economic engine of the modern generic industry. It transforms patent law from a static, impenetrable barrier into a dynamic, high-stakes game of risk and reward. The companies that thrive in this environment are not merely good manufacturers; they are elite legal and strategic risk-takers whose core competency is evaluating the legal vulnerability of a multi-billion-dollar patent against the immense financial reward of being the first to tear it down.

The Hatch-Waxman Act: The Law That Created an Industry

Enacted in 1984, the Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act—universally known as the Hatch-Waxman Act—was a grand legislative compromise that fundamentally reshaped the pharmaceutical industry.7 Its genius lies in its elegant balance of two competing interests. On one hand, it sought to preserve the incentives for innovation by granting brand-name drug companies patent term extensions to compensate for the time their products spent in the lengthy FDA approval process.16 On the other hand, it aimed to accelerate the availability of affordable medicines by creating a streamlined pathway for generic competition.7

Before Hatch-Waxman, the generic industry was nascent. Generic firms had to conduct their own clinical trials, and the simple act of developing a generic version of a patented drug could be considered patent infringement, effectively adding years to a brand’s monopoly even after its patent expired.7 The Act changed everything. As discussed, it created the ANDA pathway, but it also introduced two other revolutionary provisions:

- The “Safe Harbor”: Codified in 35 U.S.C. §271(e)(1), this provision created a statutory exemption from patent infringement for activities “reasonably related to the development and submission of information” to the FDA.7 This “safe harbor” is the legal bedrock that allows generic companies to begin development work, conduct bioequivalence studies, and prepare their ANDAs long before the brand’s patents expire, ensuring they are ready to launch on the very day of patent expiry.

- The Patent Certification Process: The Act requires brand companies to list all relevant patents covering their drugs in an FDA publication known as the “Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations,” or the “Orange Book”.7 In turn, any generic company filing an ANDA must make a certification for each patent listed in the Orange Book for the RLD it is copying. This mechanism sets the stage for the legal battles to come.

The Paragraph IV Challenge: A Declaration of War

When filing an ANDA, a generic applicant must choose one of four certifications for each Orange Book-listed patent 14:

- Paragraph I: No patent information has been filed in the Orange Book.

- Paragraph II: The patent has already expired.

- Paragraph III: The generic company will wait to launch until the patent expires.

- Paragraph IV: The patent is invalid, unenforceable, or will not be infringed by the generic product.

While the first three are straightforward declarations of compliance, a Paragraph IV (P-IV) certification is a direct and aggressive challenge to the brand’s intellectual property. It is a calculated declaration of war.14 Under the Hatch-Waxman Act, the very act of filing an ANDA with a P-IV certification is considered an “artificial act of infringement,” which gives the brand company the immediate right to sue.14

This triggers a carefully choreographed legal dance. The generic company must send a detailed “notice letter” to the brand owner and patent holder within 20 days of the FDA accepting its ANDA for review. This letter must lay out the full factual and legal basis for the generic’s assertion that the patent is invalid or not infringed. Upon receiving this notice, the brand owner has a critical 45-day window. If they file a patent infringement lawsuit within that period, it triggers an automatic 30-month stay on the FDA’s ability to grant final approval to the generic’s ANDA. This stay is a powerful tool for the brand, providing a roughly two-and-a-half-year period of protected revenue while the patent dispute is litigated in court, regardless of the ultimate outcome.

The Grand Prize: 180-Day Exclusivity

Why would a generic company invite such a costly and time-consuming lawsuit? The answer lies in the grand prize offered by the Hatch-Waxman Act: 180-day marketing exclusivity.10 To incentivize generic firms to take on the risk and expense of challenging potentially weak or invalid patents, the law grants a lucrative six-month period of exclusivity to the first applicant (or group of applicants on the same day) to file a “substantially complete” ANDA containing a P-IV certification.14

During this 180-day period, the FDA is barred from approving any subsequent ANDAs for the same drug. This effectively creates a temporary duopoly between the brand-name drug and the first generic challenger. The financial implications are immense. Freed from the threat of immediate, multi-player competition, the first-to-file (FTF) generic can price its product at a relatively modest discount to the brand—often just 15% to 30% lower—while rapidly capturing a dominant market share.4 This allows the FTF to recoup its development and litigation costs and earn substantial profits before the “Day 181” phenomenon occurs, when the floodgates open to other generics and prices plummet by as much as 95%. The potential payoff is so significant that it makes the legal gamble worthwhile; one study found that FTF P-IV challenges have a 76% success rate.

The Brand’s Counter-Offensive: Patent Thickets, Pay-for-Delay, and Authorized Generics

Brand-name companies do not stand idly by as their multi-billion-dollar revenue streams are threatened. They have developed a sophisticated and aggressive arsenal of defensive strategies designed to delay, deter, and disrupt generic entry.

- Patent Thickets and Evergreening: This is a primary defensive line. Instead of relying on a single core patent, innovator companies create a dense “thicket” of overlapping secondary patents around a single drug.10 These patents may cover minor variations, such as different crystalline forms, new formulations (e.g., extended-release), specific methods of use, or manufacturing processes. This strategy, known as “evergreening,” is designed to extend a drug’s monopoly far beyond the expiration of its original composition-of-matter patent.18 For top-selling drugs, an astonishing 66% of patent applications are filed

after the drug has already received FDA approval, indicating a clear strategy of market extension rather than initial innovation. - “Pay-for-Delay” Settlements: Faced with a P-IV challenge, a brand company might conclude that its patents are vulnerable or that the cost of litigation is too high. In the past, a common tactic was to settle the lawsuit with a “reverse payment,” also known as a “pay-for-delay” agreement. In these deals, the brand company pays the generic challenger to abandon its patent challenge and agree to delay its market entry for a specified period.14 These settlements have come under intense antitrust scrutiny from the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), which argues they are anti-competitive agreements that harm consumers by keeping drug prices artificially high. An FTC study concluded these deals cost consumers and taxpayers $3.5 billion annually. The landmark 2013 Supreme Court case,

FTC v. Actavis, ruled that such payments could indeed violate antitrust laws, fundamentally changing the landscape for these types of settlements.14 - Authorized Generics (AGs): This is a particularly cunning counter-move. An authorized generic is a generic version of a drug that is marketed by the brand company itself or under license to another firm.23 The brand company will often launch its AG during the 180-day exclusivity period of the first P-IV challenger. Because the AG is not approved under an ANDA, it is not blocked by the 180-day exclusivity. This move directly attacks the FTF’s most valuable asset. The presence of an AG can slash the first filer’s revenues by 40% to 52% during the exclusivity period by immediately introducing price competition, though it also tends to lower prices for consumers more quickly.

Pillar 3: The Commercial Playbook – From Market Intel to Supply Chain Mastery

Winning the regulatory and legal battles gets you to the starting line, but a well-executed commercial strategy is what wins the race. The commercial playbook for a generic launch is a discipline of precision, foresight, and operational excellence. It begins years before launch with rigorous intelligence gathering and ends with a supply chain that can withstand the immense pressure of a blockbuster launch. In the generic world, the initial high-margin period of exclusivity is a fleeting window of opportunity. The enduring competitive advantage, the one that allows a company to survive and thrive in the hyper-competitive post-exclusivity market, is not determined by the launch price, but by the underlying cost structure. The most critical long-term investments are therefore not in flashy marketing campaigns, but in the unglamorous, indispensable work of optimizing manufacturing and mastering the supply chain.

The “Day Zero” Imperative: Market Research and Opportunity Selection

The decision to pursue a generic drug is the most important one a company will make, and it must be rooted in data, not intuition. A successful launch begins years in advance with a disciplined process of market research and opportunity selection. The goal is to build a portfolio of products that balances risk and reward.

The process starts with identifying high-value targets. This involves systematically monitoring brand-name drugs with significant sales—typically those generating over $1 billion annually before patent expiration—as they approach their patent cliff. But high sales alone are not enough; the competitive landscape is equally critical. A blockbuster drug will attract a crowd of competitors, leading to rapid and severe price erosion. The ideal target may be a drug with a market size large enough to be profitable ($50 million to $200 million annually is often considered a sweet spot) but not so large that it invites a flood of “Day 181” entrants.

This is where sophisticated competitive intelligence becomes invaluable. Platforms like DrugPatentWatch are essential tools for the modern generic strategist. They provide curated, integrated data on patent expiration dates, regulatory exclusivities, the status of patent litigation, and competitor ANDA filings.1 By leveraging such platforms, companies can move beyond simple patent expiry lists and build a dynamic picture of the future competitive environment, allowing them to identify low-competition niches and make smarter, data-driven decisions about which products to add to their development pipeline. Predictive modeling, which analyzes historical launch data to forecast a generic’s potential performance, is another powerful tool; one study found that companies using such analytics saw 20% higher market penetration within six months of launch.1

The Art of Pricing: Balancing Value, Perception, and Competition

Generic drug pricing is a dynamic art, a delicate balancing act between capturing value, managing perception, and responding to intense competitive pressure. The strategy must evolve rapidly as the market moves from a duopoly to a multi-player commodity environment.

- Phase 1: The Exclusivity Window. For the first-to-file generic enjoying 180-day exclusivity, the pricing strategy is focused on value capture. The product can be launched at a modest discount to the brand’s wholesale acquisition cost (WAC), typically in the range of 15% to 30%.4 This allows the company to rapidly recoup its significant development and legal costs while capturing a dominant share of the market from the higher-priced brand.

- Phase 2: The Post-Exclusivity Plunge. The moment the 180-day exclusivity period ends—often referred to as “Day 181″—the market dynamics change instantly and brutally. The FDA can now approve other ANDAs, and as more competitors enter, prices plummet. The data on this price erosion is stark and predictable: with just two generic competitors, the average price reduction compared to the brand is 54%. With three to five competitors, prices fall further. With six or more competitors, prices can drop by an astonishing 95%. In this phase, the strategy shifts from value capture to market share defense. Pricing becomes reactive and is driven primarily by cost-of-goods-sold (COGS). The goal is to price just low enough to maintain volume while still covering costs and a minimal profit margin.

The Unsung Hero: Building a Resilient Supply Chain

A brilliant legal victory and a perfect pricing strategy are meaningless if you cannot get your product onto pharmacy shelves. A robust, scalable, and compliant supply chain is the operational backbone of a successful launch and a powerful, though often overlooked, competitive advantage.

The process begins with the rigorous vetting and qualification of Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) suppliers. Given the geographic concentration of API manufacturing in regions like India and China, building a resilient supply chain requires diversifying sources to mitigate geopolitical risks, potential quality crises, or shipping disruptions.1 A company that has qualified multiple API suppliers is not only insulated from shortages but is also positioned to capitalize on a competitor’s supply failure by rapidly scaling up its own production.

Furthermore, the supply chain must be built for the immense demand spike of a major launch. Over 30% of generic launches experience unexpected surges in demand in their first year. The inability to meet this demand can permanently damage a company’s reputation with wholesalers and pharmacy chains. The 2022 shortage of generic amoxicillin serves as a stark reminder of how quickly supply chain glitches can erode market confidence and tank a launch.

Gaining Access: Winning Over Payers and PBMs

In the U.S. healthcare system, market access is controlled by powerful intermediaries, chief among them Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs). Securing a favorable position on their formularies—the lists of covered drugs—is non-negotiable for a successful launch.

Fortunately, the generic value proposition aligns perfectly with the PBMs’ core objective of cost containment. Generic drugs are typically placed in Tier 1 on formularies, the category with the lowest patient co-payment. This financial incentive is a powerful driver of utilization, as both patients and pharmacists are motivated to choose the lowest-cost option. Unlike brand-name drugs, which often involve complex rebate negotiations, the engagement with PBMs for generics is more straightforward, centered on their low net price. The key is to engage with payers and PBMs early in the pre-launch phase, providing them with data on cost-effectiveness and launch timing so they can update their formularies and ensure rapid uptake the moment your product hits the market.

Part II: Titans of Generic Entry – In-Depth Case Studies

The principles outlined in Part I provide the theoretical blueprint for success. Now, we turn to the real world, where these strategies are tested under the immense pressure of multi-billion-dollar markets. The following three case studies represent some of the most significant and instructive generic launches in pharmaceutical history. They are not just stories of patent expirations; they are epic sagas of legal warfare, bold commercial gambles, and market-altering consequences. By dissecting the strategies of both the brand defenders and the generic challengers, we can distill timeless lessons that remain profoundly relevant today.

Table 2: Tale of Three Titans: Comparative Analysis of Landmark Generic Launches

| Feature | Atorvastatin (Lipitor) | Imatinib (Gleevec) | Clopidogrel (Plavix) |

| Brand Company | Pfizer | Novartis | Bristol-Myers Squibb / Sanofi |

| Challenger (FTF) | Ranbaxy Laboratories | Sun Pharma | Apotex Inc. |

| Brand’s Peak Annual Sales | ~$13 Billion | ~$4.7 Billion | ~$9.8 Billion |

| Core Brand Defense Strategy | Multi-front commercial warfare: DTC advertising, PBM deals, authorized generic (AG).24 | Legal “evergreening”: Securing secondary patents on a more stable crystalline salt form of the molecule.20 | Legal maneuvering and “pay-for-delay”: Attempted settlement to delay generic entry, which later collapsed.29 |

| Core Challenger Strategy | First-to-File (FTF) P-IV challenge, but launch was delayed by settlement and FDA manufacturing issues. | FTF P-IV challenge targeting the secondary “evergreening” patents, followed by a negotiated settlement for entry.20 | FTF P-IV challenge followed by a high-stakes “at-risk” launch after a settlement deal failed.32 |

| Key Outcome | Massive market disruption. Generic atorvastatin rapidly dominated, saving the healthcare system billions. Pfizer’s revenue plummeted despite its aggressive defense.34 | Landmark legal precedent against “evergreening” in India. In the US, generic imatinib became the cost-effective standard of care, saving billions.36 | A cautionary tale. Apotex lost the patent suit and was ordered to pay over $442 million in damages. However, their brief at-risk launch cost BMS over $1.2 billion in lost sales.38 |

| Enduring Strategic Lesson | For a true blockbuster, a brand will co-opt the generic’s low-cost value proposition to defend market share, forcing generics to compete on more than just price. | The strategic battleground for specialty drugs is shifting to more nuanced legal arguments over what constitutes a patentable invention and commercial arguments over economic value (e.g., ICER). | An “at-risk” launch is the ultimate high-risk, high-reward gamble that requires rigorous, probabilistic financial modeling and a board-level appetite for potentially catastrophic risk. |

Case Study 1: Atorvastatin (Generic Lipitor) – The Blockbuster Takedown

There has never been a patent cliff quite like Lipitor’s. It was not merely a drug; it was a global phenomenon, the single best-selling pharmaceutical product in history. Its story is the quintessential case study in how a determined brand, armed with a nearly limitless budget, can wage a multi-front war to defend its franchise—and how, in the end, the relentless economic force of generic competition can still triumph.

The Stage: The World’s Best-Selling Drug on the Precipice

By the time its primary U.S. patent was set to expire on November 30, 2011, Pfizer’s Lipitor (atorvastatin) had achieved a status that few drugs ever will. It was a household name, a cholesterol-lowering statin that had generated more than $150 billion in cumulative revenue for its owner.26 At its peak in 2006, annual sales reached a staggering $12.9 billion. The expiration of its patent was, without exaggeration, the most anticipated and financially significant event in the history of the generic drug industry. The sheer size of the prize meant that the ensuing battle would be fought with unprecedented intensity and strategic creativity.

The Brand’s Fortress: Pfizer’s Multi-Pronged Defense

Facing the loss of its crown jewel, Pfizer refused to go quietly. It architected and executed one of the most aggressive, comprehensive, and expensive brand defense campaigns ever witnessed. This was not a single strategy but a coordinated, multi-front war designed to slow the erosion of its market share and extract every last dollar of revenue from its blockbuster.

First came the marketing and direct-to-consumer (DTC) advertising blitz. For years leading up to the patent expiry, Pfizer’s promotion of Lipitor centered on a single, powerful message: authenticity and inimitableness.26 The most famous of these campaigns featured Dr. Robert Jarvik, an inventor of the artificial heart, who was presented not as an actor but as a “real” doctor and patient, reinforcing the idea that Lipitor was the authentic, original article. The tagline “I take Lipitor instead of a generic” was embedded in the public consciousness, creating a powerful narrative that no generic could truly compare. Even after the Jarvik campaign faced controversy, the core message continued with the tautological but effective slogan, “Only Lipitor is Lipitor”.

Second, Pfizer went directly to the power brokers of the supply chain: payers and PBMs. In a move that upended traditional generic launch dynamics, Pfizer began cutting deals with major PBMs like Medco Health Solutions to offer them deep discounts on brand-name Lipitor for at least six months post-patent expiry.24 The goal was to make the brand-name drug cheaper for the health plan than the first generic. This was complemented by co-pay cards for patients, which could be used as secondary insurance to lower their out-of-pocket costs, sometimes making the brand co-pay lower than the generic co-pay.24 This strategy was designed to eliminate the financial incentive for patients and plans to switch, directly attacking the generic’s core value proposition.

Third, Pfizer deployed the authorized generic (AG). Recognizing that a generic challenger would eventually break through, Pfizer made a deal with Watson Pharmaceuticals (now part of Teva) to launch an authorized generic version of Lipitor.24 This AG would launch on the same day as the first independent generic, immediately introducing competition during the challenger’s 180-day exclusivity period. This was a calculated move to accelerate price erosion and cannibalize the sales of its primary generic rival, ensuring that if profits were to be made on a generic, a portion would flow back to Pfizer.

Finally, Pfizer engaged in the expected legal delays and litigation. It pursued every available legal avenue to extend its patent life and delay the inevitable entry of a generic competitor, including engaging in a protracted legal battle with the first-to-file challenger, Ranbaxy Laboratories.24

The Challenger’s Gambit: Ranbaxy’s First-to-File Strategy

The role of the primary challenger fell to Indian generic giant Ranbaxy Laboratories. As the first company to file an ANDA with a Paragraph IV certification, Ranbaxy held the coveted prize of 180-day marketing exclusivity.24 However, its path to market was anything but smooth.

Ranbaxy’s strategy was complicated from the start by a mutual settlement agreement with Pfizer. This deal, which later became the subject of a massive antitrust lawsuit alleging it was an illegal pay-for-delay scheme, deferred Ranbaxy’s planned launch by five months, from June to November 2011.24 This delay alone cost the U.S. healthcare system billions in potential savings.

Compounding the delay were severe quality control problems. The FDA uncovered significant data integrity and manufacturing standard violations at two of Ranbaxy’s key production facilities in India, placing a hold on approvals from those plants and casting a shadow over the company’s impending Lipitor launch. This created immense uncertainty, with many in the industry questioning whether Ranbaxy would be able to launch at all. Ultimately, Ranbaxy managed to secure FDA approval and launched its generic atorvastatin, manufactured at its U.S.-based Ohm Laboratories facility, on November 30, 2011.42

The Aftermath: Market Disruption and Unprecedented Savings

Despite Pfizer’s formidable and multifaceted defense, the launch of generic atorvastatin was a watershed moment for the U.S. healthcare system. The economic forces at play were simply too powerful to be held back indefinitely.

The financial impact on Pfizer was immediate and severe. In the fourth quarter of 2011, the first to include generic competition, Pfizer’s profit fell by half.48 For the full year of 2012, Pfizer’s revenues dropped by 10%, a decline primarily attributed to the loss of Lipitor exclusivity in the U.S. and Europe. The company’s Primary Care unit saw its revenues decline by a staggering 28% operationally, with the loss of Lipitor sales accounting for an approximate $1.8 billion hit in a single quarter.

Conversely, the market uptake of the generic was swift and the savings were enormous. A study analyzing the period from 2012 to 2014 found that while the total number of atorvastatin users in the U.S. increased by 20% (from 12.5 million to 15.0 million), total spending on the drug decreased by 23% (from $7.0 billion to $5.4 billion). The expenditure on brand-name Lipitor itself collapsed, falling from $3.5 billion in 2012 to just $357 million in 2014. In the United Kingdom, the launch of generic atorvastatin was estimated to have saved the National Health Service (NHS) £350 million in the first 12 months alone. Over time, the dominance of the generic became absolute. By 2022, in the U.S. Medicaid population, generics accounted for 99.9% of all statin prescription claims. The shift towards generic variants became the dominant trend in the atorvastatin market, driving cost-effectiveness and increasing accessibility for patients worldwide.51

The Lipitor case study is a powerful testament to the fact that for a true blockbuster, the market is large enough for both the brand and the generic to deploy billion-dollar strategies. It fundamentally redefined the nature of brand defense. Pfizer’s approach demonstrated that a brand company will not hesitate to co-opt the generic’s core value proposition—low cost—through strategic discounting and PBM partnerships. This created a paradoxical, if temporary, market where the brand was sometimes cheaper for the patient or payer than the generic. This reveals a critical lesson for today’s generic strategists: when the stakes are this high, you must anticipate that the brand will sacrifice its own pricing structure to disrupt your launch model. A successful counter-strategy must therefore go beyond simple price competition and may require a focus on supply chain reliability, deep partnerships with payers who refuse the brand’s deals, or other creative value propositions.

Case Study 2: Imatinib (Generic Gleevec) – The Battle Over Value, Access, and Evergreening

If the Lipitor case was a heavyweight brawl over a mass-market blockbuster, the story of generic Gleevec represents a more modern and nuanced conflict. This was a battle fought not just over patents, but over the very definition of innovation. It involved a life-saving specialty cancer drug with a controversial price tag, a sophisticated “evergreening” strategy by the brand, and a landmark legal decision in India that sent shockwaves through the global pharmaceutical industry. The Gleevec case marks the maturation of the generic industry, moving it from the realm of simple small molecules to the complex, high-value world of specialty pharmaceuticals.

The Stage: A Life-Saving Cancer Drug with a Controversial Price Tag

Novartis’s Gleevec (imatinib) was nothing short of a medical miracle. Approved by the FDA in 2001, this targeted tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) transformed Chronic Myeloid Leukemia (CML) from a fatal cancer into a manageable chronic condition, giving many patients a normal life expectancy.36 It was a triumph of modern medicine. However, this breakthrough came with a steep and ever-increasing price. Initially launched at around $30,000 per year, the price of Gleevec in the U.S. soared to an astonishing $120,000 per year by 2016.20

This pricing strategy, while generating billions in revenue for Novartis (global sales were $4.66 billion in 2015), created significant patient access issues and drew sharp criticism from physicians and patient advocates.20 The combination of its life-saving efficacy and its exorbitant price made Gleevec a prime, albeit highly scrutinized, target for generic competition.

The Brand’s Moat: Novartis’s Evergreening and Global Patent Strategy

Novartis, like Pfizer before it, was determined to protect its valuable franchise. Its defense, however, was less about mass-market commercial tactics and more about a sophisticated, legally-focused “evergreening” strategy designed to extend Gleevec’s monopoly well beyond its initial patent term.18

The strategy hinged on a subtle but critical chemical distinction. Novartis had first patented the base imatinib molecule in the early 1990s. However, the company argued that this initial form was not medically viable and could not be administered to patients.28 Through further research, its scientists developed a specific crystalline salt form—imatinib mesylate—which was more stable and had 30% greater bioavailability, allowing it to be formulated into an effective oral pill. Novartis successfully argued in the U.S. and other jurisdictions that this new salt form was a distinct and patentable invention, and it was awarded a secondary patent on this form that extended its market exclusivity to 2019.20

This strategy, however, met a formidable roadblock in India. The country’s 2005 Patents Act contains a unique provision, Section 3(d), which explicitly disallows patents on new forms of known substances unless they demonstrate a significant enhancement in therapeutic efficacy.37 In a historic and protracted legal battle, the Indian Supreme Court ruled against Novartis in 2013, finding that the beta-crystalline form of imatinib mesylate was not a new invention but merely an amended version of a known substance that did not offer improved efficacy.37 The court’s decision was a landmark victory for health activists and the Indian generic industry, and a major blow to the practice of evergreening globally.

In the United States, the legal landscape was different. The secondary patents were valid and formed the core of Novartis’s defense. Sun Pharma, the first-to-file generic challenger, filed a lawsuit in 2013 seeking to have the patents declared invalid.55 The two companies eventually reached a settlement agreement. In exchange for dropping the litigation, Sun Pharma was granted a license to launch its generic version on February 1, 2016—seven months after the expiration of Gleevec’s original compound patent, but more than three years before the secondary formulation patent was set to expire.20

The Challenger’s Approach: Sun Pharma’s Calculated Entry

As the first-to-file challenger, Sun Pharma secured the all-important 180-day marketing exclusivity in the U.S..31 Its launch strategy reflected the unique dynamics of a specialty oncology market.

- Pricing Strategy: Sun Pharma announced it would price its generic at a 30% discount to Gleevec’s brand price. While this represented significant savings, it was a far cry from the 80-90% price drops often seen with mass-market generics. This more conservative pricing reflected the higher costs associated with developing and litigating a complex specialty drug, as well as the opportunity to maximize revenue during the lucrative exclusivity period. Analysts projected that Sun could earn $250-300 million in revenue during these first six months alone.31

- “Skinny Labeling”: A key part of the market access strategy involved the use of a “skinny label.” At the time of the generic launch, Novartis still held patent protection for the use of imatinib in treating gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs). To avoid infringing this patent, Sun Pharma’s generic was launched with a label that “carved out” the GIST indication, including only the indications for which patents had expired, such as CML. This is a common and powerful strategy enabled by the Hatch-Waxman Act that allows generics to come to market for some, but not all, of a brand drug’s approved uses.

The Aftermath: Redefining Generic Value and Cost-Effectiveness

The arrival of generic imatinib had a profound impact on the CML treatment landscape and the economics of cancer care. The cost savings were immense. One comprehensive analysis modeled that the use of generic imatinib would save U.S. payers a staggering $15 billion over a five-year period. In the first two years alone, savings amounted to $2.5 billion.36

The case also ignited a crucial debate about value in medicine. With the availability of a lower-cost, bioequivalent generic, the high prices of Novartis’s branded Gleevec and its newer, second-generation (and also patent-protected) TKIs came under intense scrutiny. Health economics analyses became a powerful tool. One influential study calculated that choosing to start treatment with a patented TKI instead of generic imatinib had an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) of $883,730 per quality-adjusted life year (QALY) gained. This figure is nearly 18 times higher than the commonly accepted willingness-to-pay threshold of $50,000 per QALY, making the choice of generic imatinib as a first-line therapy an overwhelmingly cost-effective strategy.

The market responded accordingly. Uptake of the generic was rapid and widespread. Within just three years of its launch, more than 90% of newly diagnosed patients with CML or GIST were starting their treatment with a generic version of imatinib. The generic had successfully displaced the brand as the standard of care, unlocking billions in savings and improving access to this life-saving therapy. The Gleevec case illustrates that for future specialty and complex generics, the legal fight will become more technical, centered on nuanced arguments about what constitutes a patentable invention. Simultaneously, the commercial strategy will need to incorporate sophisticated health economics arguments to justify pricing and drive adoption, especially when the initial discount is not as steep as with traditional generics.

Case Study 3: Clopidogrel (Generic Plavix) – The High-Stakes Gamble of an “At-Risk” Launch

Our final case study is a cautionary tale, a high-stakes drama of legal brinkmanship, regulatory intervention, and a strategic gamble that went spectacularly wrong—and yet, in a way, still succeeded. The story of generic Plavix, and specifically the actions of Canadian generic firm Apotex, is the ultimate masterclass in risk management. It demonstrates what happens when a challenger, frustrated by the brand’s defensive maneuvers, decides to throw caution to the wind and launch its product “at-risk,” before the final resolution of a patent dispute. It is a story that forces a critical strategic question: how do you quantify and manage a level of risk that could either secure market dominance or lead to financial ruin?

The Stage: A Blood Thinner Blockbuster and a Ticking Clock

Plavix (clopidogrel), an antiplatelet medication used to prevent heart attacks and strokes, was another colossal blockbuster, co-marketed by Bristol-Myers Squibb (BMS) and Sanofi. With global sales approaching $9.8 billion in 2009, it was the second best-selling drug in the world and a critical revenue driver for both companies.25 The primary patent protecting the drug was set to expire, and the designated first-to-file challenger was Apotex Inc., a notoriously aggressive Canadian generic manufacturer.30

The Brand’s Defense: The Controversial “Pay-for-Delay” Settlement

As was standard practice, BMS and Sanofi filed a patent infringement lawsuit against Apotex after it submitted its ANDA with a Paragraph IV certification. The two sides then entered into negotiations to settle the litigation. In March 2006, they reached an agreement that was a classic example of a “pay-for-delay” deal.29 Under the terms, Apotex agreed to delay the launch of its generic version until September 2011, just a few months before the patent was set to expire. In exchange, BMS and Sanofi would make a substantial payment to Apotex, rumored to be at least $40 million.29

However, the legal and regulatory environment around such deals was rapidly changing. The FTC and a group of state attorneys general intervened, refusing to approve the settlement on antitrust grounds, arguing it was an illegal conspiracy to keep a lower-cost generic off the market.29 The deal collapsed, the lawsuit was back on, and Apotex was left facing a lengthy and uncertain court battle.

The Challenger’s Ultimate Gamble: The “At-Risk” Launch

Frustrated by the failed settlement and confident in its legal position that the Plavix patent was invalid, Apotex made a momentous and audacious decision. On August 8, 2006, without waiting for the court to rule on the patent’s validity, Apotex launched its generic clopidogrel in the U.S. market.32 This was an “at-risk” launch—a massive gamble that the company would ultimately win the patent case.

The immediate effect was explosive. The launch triggered the start of Apotex’s 180-day exclusivity period and unleashed a flood of low-cost generic Plavix into the U.S. supply chain.32 BMS and Sanofi immediately raced to court, seeking an injunction to halt the sales. While an earlier agreement prevented them from getting an immediate temporary restraining order, on August 31, 2006—just 24 days after the launch—a federal judge granted a permanent injunction that barred Apotex from further marketing its product pending the outcome of the trial.29 The genie was out of the bottle, but the court was trying to force it back in.

The Aftermath: A Pyrrhic Victory and a Costly Lesson

The legal and financial fallout from Apotex’s 24-day gamble was immense and serves as a stark lesson in the asymmetry of risk in patent litigation.

- The Legal Fallout: Apotex’s bet did not pay off. In 2007, the U.S. District Court ruled that the Plavix patent was valid and had been infringed by Apotex. This decision was upheld on appeal. Because Apotex had launched at-risk, it was now liable for massive damages. After years of further legal wrangling over the amount, Apotex was ultimately ordered to pay BMS and Sanofi a staggering $442.2 million in damages, plus over $1.2 million in interest and $900,000 in costs.38

- Financial Impact on the Brand: While BMS and Sanofi won the lawsuit and received a massive damages award, it was a pyrrhic victory. The financial damage caused by Apotex’s brief at-risk launch was catastrophic. The few weeks of generic competition, combined with the large volume of generic product that remained in the distribution channel and had to be worked through, decimated Plavix sales. In its 2006 annual report, BMS stated that the at-risk launch had reduced its Plavix sales by $1.2 billion to $1.4 billion in that year alone. The company swung from a net profit of $499 million in Q4 2005 to a net loss of $134 million in Q4 2006, a reversal driven almost entirely by the Plavix situation.

- Market Dynamics: When Plavix’s patent exclusivity finally and legitimately expired in May 2012, the market transition was swift. Multiple generics entered, and the price of clopidogrel plummeted. Bristol-Myers Squibb’s second-quarter 2012 revenue for Plavix plunged by 60% year-over-year. U.S. prescription data shows the aftermath clearly: while the number of patients taking clopidogrel has remained relatively stable, the average total cost per prescription fell from over $133 in 2013 to just over $21 in 2022.

The Plavix case is the ultimate cautionary tale about risk management. An “at-risk” launch is the pharmaceutical equivalent of an all-in bet in poker. The potential upside—capturing a blockbuster market years ahead of schedule—is enormous, but the potential downside is financially crippling. This case study moves beyond a simple win/loss narrative to become a masterclass in risk assessment. It implies that a generic company’s legal team must provide its business leadership with more than just an opinion on a patent’s validity; they must provide a rigorous, probabilistic assessment of success. The business, in turn, must model the financial outcomes of both winning and losing the subsequent lawsuit. The decision to launch at-risk must be a calculated, board-level decision based on this comprehensive modeling, not on legal optimism alone. Apotex miscalculated the odds, and the price was nearly half a billion dollars.

Part III: Synthesizing the Lessons – A Strategic Framework for the Future

The epic battles over Lipitor, Gleevec, and Plavix are more than just compelling corporate history. They are the foundational texts from which we can derive a modern strategic framework for generic and biosimilar competition. By analyzing the common threads that run through these victories and defeats, and by looking ahead to the powerful trends reshaping the industry, we can distill a set of core principles to guide decision-making in this ever-evolving landscape. The ultimate goal is to move your organization from a reactive posture, where you are surprised by market shifts, to a proactive one, where you anticipate, plan for, and capitalize on them to the fullest extent.

Cross-Case Analysis: The Common Threads of Victory and Defeat

When viewed together, the three case studies reveal a set of universal truths about the nature of generic competition. These principles transcend specific drugs or companies and form the bedrock of strategic thinking in this sector.

- The Primacy of First-to-File (FTF) Status: In every single case, the cornerstone of the challenger’s strategy was securing the first-to-file position and the 180-day exclusivity it confers. Ranbaxy for Lipitor, Sun Pharma for Gleevec, and Apotex for Plavix all built their entire strategic approach around this singular, powerful incentive. It is the engine of the Hatch-Waxman system and remains the single most valuable asset a generic company can possess when targeting a major product.

- The Asymmetry of Risk: The Plavix case illustrates this principle in its starkest form. When a generic launches at-risk, the potential outcomes are profoundly imbalanced. The brand’s downside is a temporary loss of profit. The generic’s downside is a potentially bankrupting damages award. This fundamental asymmetry shapes every strategic interaction, from settlement negotiations to launch decisions. Brand companies can afford to be aggressive in litigation because their risk is capped, while generic companies must be far more calculated, as a single misstep can be fatal.

- The Evolution of Brand Defense: The case studies show a clear evolution in how brand companies defend their franchises. The Plavix defense in the mid-2000s was centered on a relatively straightforward (though ultimately illegal) pay-for-delay settlement. By the 2010s, the defenses had become far more sophisticated. Pfizer’s war for Lipitor was a masterclass in commercial and supply-chain warfare, while Novartis’s defense of Gleevec was a highly technical legal strategy rooted in the nuances of chemical formulation. This demonstrates that generic challengers must anticipate an increasingly creative and multi-pronged defense tailored to the specific product and market.

- The Inevitability of the Cliff: Perhaps the most important lesson is that while a brand can delay and disrupt, it cannot ultimately defy the economic gravity of the patent cliff. Pfizer’s all-out defense of Lipitor, arguably the most aggressive in history, succeeded only in slowing the erosion, not stopping it. The financial impact, as shown in the table below, is both predictable and devastating. For a generic company, this is a source of confidence: the market forces are on your side. For a brand company, it is a stark mandate: you must innovate your way out of the cliff, because you cannot defend your way out of it forever.

Table 3: The Financial Aftermath: Quantifying the Patent Cliff

| Company & Product | Pre-Exclusivity Peak Annual Sales | Post-Exclusivity Revenue Impact | Key Takeaway |

| Pfizer (Lipitor) | $12.9 Billion (2006) | – Q4 2011 profit fell by 50%. – Full-year 2012 revenues declined by 10% ($6.3 billion), primarily due to Lipitor. – Primary Care unit revenues dropped 28% in one quarter. | The loss of a single blockbuster can erase billions in revenue and fundamentally alter a company’s financial trajectory almost overnight. |

| Novartis (Gleevec) | $4.66 Billion (2015) 53 | – Q3 2016 net sales were flat (-1% cc) as growth products were needed to offset Gleevec’s generic erosion. – The company’s core operating income margin declined due to the loss of exclusivity. | Even for a diversified company, the loss of a specialty blockbuster creates a significant headwind that requires strong performance from the rest of the portfolio to overcome. |

| Bristol-Myers Squibb (Plavix) | ~$6.6 Billion (U.S. sales in 2011, year before LOE) | – The brief 2006 at-risk launch cost BMS $1.2-$1.4 billion in lost sales. – After full LOE in May 2012, Q2 2012 Plavix revenue plunged 60%. – Full-year 2012 earnings forecast was lowered. | The financial shock of generic entry is immediate and severe. Even a temporary disruption can have a billion-dollar impact on the top line. |

The Future of Generic Competition: Navigating the New Landscape

The lessons from these past battles are invaluable, but the strategic landscape is constantly shifting. The future of generic competition will be shaped by new scientific frontiers, transformative policy changes, and an increasingly complex global marketplace. Success will require not only mastering the old playbook but also adapting to these powerful new trends.

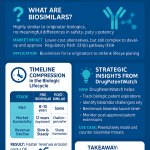

- The Rise of Complex Generics and Biosimilars: The market for simple, oral solid-dose generics is largely saturated, with intense competition driving margins to near-zero. The future of profitable growth lies in the more challenging and less crowded spaces of complex generics and biosimilars.1 These products—which include injectables, inhalers, transdermal patches, and generic versions of large-molecule biologic drugs—have high scientific and technical barriers to entry. The difficulty in development and manufacturing naturally limits the number of competitors, allowing for more stable pricing and healthier profit margins.1 Companies that invest in the specialized scientific and regulatory expertise required to master these products will be the winners of the next decade.

- The Impact of Policy Shifts: The policy environment is a dynamic and powerful force. In the U.S., the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) of 2022 represents a seismic shift. Its provisions allowing Medicare to negotiate drug prices for top-selling drugs fundamentally alter the economic calculus for generic development. By lowering the brand price anchor against which generics must compete, the IRA may reduce the financial incentive to challenge patents on some of the very biggest blockbuster drugs.3 Furthermore, its “pill penalty,” which makes small-molecule drugs eligible for negotiation after just nine years (versus 13 years for biologics), is expected to shift innovator R&D investment away from small molecules, potentially shrinking the pipeline of future generic targets.3

- Diverging Global Markets: A one-size-fits-all global strategy is now obsolete. The world has fractured into distinct regional markets, each with its own unique rules of engagement. Success requires deep, localized expertise. A strategy built for the patent-centric litigation of the U.S. will fail in China, where success is dictated by winning government tenders through the Volume-Based Procurement (VBP) system, which demands aggressive pricing and hyper-efficient manufacturing. Similarly, navigating Europe requires mastering a complex mosaic of national pricing, reimbursement, and tendering systems.

- The Centrality of Intelligence: In this increasingly complex and fragmented world, the need for sophisticated, integrated competitive intelligence has never been greater. The ability to track patents, monitor litigation, anticipate regulatory changes, and understand competitor pipelines across multiple jurisdictions is no longer a luxury but a core strategic necessity. Platforms like DrugPatentWatch that aggregate and analyze this disparate data are becoming indispensable tools for identifying opportunities and mitigating risks in a global market.1

The confluence of these trends points toward a future of bifurcation in the generic industry. One segment will be a high-volume, low-margin “commodity” market for simple molecules, a game of massive scale where only the most efficient global manufacturers can survive. Concurrently, a high-margin, “specialty” generic and biosimilar market will flourish, where success will be defined not by scale, but by scientific sophistication, regulatory mastery, and the strategic acumen to navigate complex legal and pricing challenges. Companies must consciously and strategically choose which of these games they intend to play—and win.

Conclusion: From Intelligence to Action

The journey through the world of generic pharmaceuticals reveals a landscape far more dynamic and strategically demanding than its “copycat” reputation suggests. The successes and failures of the challengers who took on titans like Lipitor, Gleevec, and Plavix are not relics of the past; they are enduring lessons etched into the industry’s DNA. They teach us that victory is not a matter of chance but the deliberate product of a deeply integrated strategy that fuses legal audacity, regulatory precision, and commercial foresight into a single, unified force.

Sustained success in this industry requires a fundamental shift in mindset: from that of a low-cost manufacturer to that of a high-level strategist. It demands an organization that treats its legal and regulatory departments not as cost centers or compliance functions, but as core drivers of competitive advantage. It requires a commercial team that thinks in terms of multi-year campaigns, not quarterly sales targets. And it necessitates a leadership team that possesses the courage to make calculated, high-stakes bets based on rigorous, data-driven intelligence. The patent cliffs will continue to appear, and the gold rush will continue. The companies that thrive will be those that have learned the lessons of the past to master the challenges of the future.

“In the United States, 9 out of 10 prescriptions filled are for generic drugs. Increasing the availability of generic drugs helps to create competition in the marketplace, which then helps to make treatment more affordable and increases access to healthcare for more patients.”

— U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)

Key Takeaways

- Strategy is the True Innovation: In the generic industry, the most valuable R&D is often in the development of a winning legal, regulatory, and commercial strategy, not just the replication of a molecule.

- Master the Hatch-Waxman Game: The Paragraph IV challenge and the pursuit of 180-day first-to-file exclusivity are the central economic drivers of the U.S. generic market. Mastering this legal and regulatory process is non-negotiable.

- Brand Defense is a Multi-Front War: Expect innovator companies to defend their blockbusters with an increasingly sophisticated arsenal, including patent thickets, authorized generics, and aggressive PBM contracting. A successful generic launch requires anticipating and countering these moves.

- The “At-Risk” Launch is a Nuclear Option: The Plavix case study serves as a stark warning. An at-risk launch is a company-defining gamble that should only be considered after rigorous, probabilistic financial modeling of both success and failure scenarios.

- Cost Structure Determines Long-Term Survival: The high margins of the exclusivity period are temporary. In the inevitable multi-player, post-exclusivity market, the company with the most efficient manufacturing and resilient supply chain will win.

- The Future is Complex and Global: Profitable growth is shifting from simple oral solids to complex generics and biosimilars. Success in this new era requires deeper scientific expertise and tailored strategies for divergent global markets like the U.S., Europe, and China.

- Intelligence is Your Ultimate Weapon: In a landscape shaped by shifting patents, regulations, and policies (like the IRA), the ability to gather, integrate, and act on competitive intelligence from platforms like DrugPatentWatch is a critical source of advantage.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. How has the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) changed the calculus for selecting Paragraph IV challenge targets?

The IRA has introduced a significant new variable into the strategic calculus. Previously, the most attractive P-IV targets were blockbuster small-molecule drugs with the highest brand prices, as this created the largest potential revenue pool. The IRA’s Medicare price negotiation program directly targets these same drugs, establishing a much lower “maximum fair price” (MFP) that a future generic would have to compete against. This drastically reduces the potential ROI for a generic challenger, making some former blockbuster targets less attractive. Strategists must now model the potential MFP for a target drug and assess whether the remaining market opportunity justifies the high cost and risk of P-IV litigation. It may shift focus towards drugs with a large commercial (non-Medicare) patient base or towards biologics, which have a longer (13-year) pre-negotiation window compared to small molecules (9 years).1

2. For a mid-sized generic firm, is it more strategic to pursue a “first-to-file” on a smaller product or be a “Day 181” entrant on a blockbuster?

This is a classic portfolio strategy question that depends on the firm’s risk tolerance and capabilities. Pursuing a “first-to-file” (FTF) on a smaller, niche product (e.g., $50-$200 million in brand sales) can be highly strategic. The litigation costs may be lower, and the market is less likely to attract a swarm of competitors, potentially leading to a more stable and prolonged period of profitability during the 180-day exclusivity. Being a “Day 181” entrant on a blockbuster like Lipitor means you avoid the immense cost and risk of P-IV litigation, but you enter a market where prices are already in freefall. Success in this scenario depends entirely on having a best-in-class cost structure and supply chain that allows you to compete profitably at razor-thin margins. For many mid-sized firms, the controlled risk and higher potential margin of a successful FTF on a smaller product is often the more attractive strategic path.

3. What are the key differences in preparing an ANDA for a complex generic (e.g., an inhaler) versus a simple oral solid?

The differences are substantial and center on the bioequivalence (BE) and Chemistry, Manufacturing, and Controls (CMC) sections. For a simple oral solid, the BE pathway is well-established: a standard in vivo pharmacokinetic study in healthy volunteers.4 For a complex generic like a metered-dose inhaler, the ANDA is far more demanding. It requires not only demonstrating pharmacokinetic equivalence but also proving equivalence in vitro for a battery of device-specific characteristics, such as delivered dose uniformity and aerodynamic particle size distribution. It may also require more complex in vivo pharmacodynamic or even clinical endpoint studies to prove therapeutic equivalence at the site of action (the lungs). The CMC section is also vastly more complex, as the application must characterize both the drug formulation and the intricate mechanics of the device itself. This requires specialized scientific expertise and a much larger investment in development.

4. How can a generic company effectively counter a brand’s “authorized generic” (AG) strategy during the 180-day exclusivity period?

Countering an AG is one of the toughest challenges for a first-filer. Since the AG introduces immediate price competition, the FTF’s primary strategy is to leverage its own operational advantages. This includes having a robust supply chain ready to meet 100% of the market demand on day one, as any supply disruption will cede share to the AG. The FTF should also engage in aggressive pre-launch contracting with major PBMs, pharmacy chains, and wholesalers, locking in purchase volumes and favorable terms. By highlighting its status as the “true” independent generic and guaranteeing supply reliability, the FTF can build partnerships that blunt the impact of the AG. In some cases, a generic may even price slightly more aggressively than anticipated to quickly capture volume before the AG can gain a foothold.

5. Given the Gleevec case in India, how should a global generic company approach patent portfolios that rely heavily on “evergreening” strategies in different legal jurisdictions?

The Gleevec case underscores the critical importance of a jurisdiction-specific legal strategy. A global generic company cannot assume that a patent which is valid in the U.S. will be valid elsewhere, especially in countries like India with specific anti-evergreening provisions like Section 3(d).37 The strategic approach should be to conduct a deep, country-by-country analysis of the brand’s patent portfolio. In jurisdictions with strong anti-evergreening laws, the company can be more aggressive in challenging secondary patents on formulations or crystalline forms. In jurisdictions like the U.S., where such patents are more frequently upheld, the strategy may shift towards designing around the patent claims or preparing for a more protracted and expensive invalidity challenge. This requires a highly sophisticated global IP team that understands the nuances of local patent law and can tailor the company’s legal and commercial strategy accordingly.

References

- The Global Generic Drug Market: Trends, Opportunities, and …, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-global-generic-drug-market-trends-opportunities-and-challenges/

- 2024 U.S. Generic & Biosimilar Medicines Savings Report, accessed August 6, 2025, https://accessiblemeds.org/resources/reports/2024-savings-report/

- The Patent Cliff’s Shadow: Impact on Branded Competitor Drug Sales – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-effect-of-patent-expiration-on-sales-of-branded-competitor-drugs-in-a-therapeutic-class/

- How to Implement a Successful Generic Drug Launch Strategy …, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/how-to-implement-a-successful-generic-drug-launch-strategy/

- Abbreviated New Drug Application – Wikipedia, accessed August 6, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abbreviated_New_Drug_Application

- Abbreviated New Drug Applications (ANDA) Explained: A Quick-Guide – The FDA Group, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.thefdagroup.com/blog/abbreviated-new-drug-applications-anda

- 40th Anniversary of the Generic Drug Approval Pathway | FDA, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/cder-conversations/40th-anniversary-generic-drug-approval-pathway

- What Is the Approval Process for Generic Drugs? | FDA, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/generic-drugs/what-approval-process-generic-drugs

- Navigating the ANDA and FDA Approval Processes – bioaccess, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.bioaccessla.com/blog/navigating-the-anda-and-fda-approval-processes

- Tracking Generic Drug Launches: A Comprehensive Guide for …, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/customer-success-will-a-generic-version-of-a-drug-launch-and-when/

- Generic Drugs Market Size to Hit USD 775.61 Billion by 2033 – BioSpace, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.biospace.com/press-releases/generic-drugs-market-size-to-hit-usd-775-61-billion-by-2033

- FDA Critical Path Initiatives: Opportunities for Generic Drug …, accessed August 6, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2751455/

- Office of Generic Drugs 2022 Annual Report – FDA, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/generic-drugs/office-generic-drugs-2022-annual-report

- What Every Pharma Executive Needs to Know About Paragraph IV …, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/what-every-pharma-executive-needs-to-know-about-paragraph-iv-challenges/

- What is Hatch-Waxman? – PhRMA, accessed August 6, 2025, https://phrma.org/resources/what-is-hatch-waxman

- Patent Term Extensions and the Last Man Standing | Yale Law & Policy Review, accessed August 6, 2025, https://yalelawandpolicy.org/patent-term-extensions-and-last-man-standing

- The Hatch-Waxman Act: A Primer – EveryCRSReport.com, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.everycrsreport.com/reports/R44643.html

- What is a patent challenge, and why is it common in generics?, accessed August 6, 2025, https://synapse.patsnap.com/article/what-is-a-patent-challenge-and-why-is-it-common-in-generics

- Patent Certifications and Suitability Petitions – FDA, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/abbreviated-new-drug-application-anda/patent-certifications-and-suitability-petitions

- Oncology drug pricing – the case of generic imatinib, accessed August 6, 2025, https://gabionline.net/generics/research/Oncology-drug-pricing-the-case-of-generic-imatinib

- FTC Report on Drug Company “Pay-for-Delay” Agreements | Health Industry Washington Watch, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.healthindustrywashingtonwatch.com/2010/01/articles/odds-ends/ftc-report-on-drug-company-pay-for-delay-agreements/

- Pay for Delay | Federal Trade Commission, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/topics/competition-enforcement/pay-delay

- Generic Drug Challenges Prior to Patent Expiration C. Scott Hemphill* and Bhaven N. Sampat – NYU Law, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.law.nyu.edu/sites/default/files/ECM_PRO_064165.pdf

- Generic Atorvastatin and Health Care Costs – PMC, accessed August 6, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3319770/

- What lessons can be learned from the launch of generic clopidogrel …, accessed August 6, 2025, https://gabi-journal.net/what-lessons-can-be-learnt-from-the-launch-of-generic-clopidogrel.html

- Managing the challenges of pharmaceutical patent expiry: a case study of Lipitor, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/309540780_Managing_the_challenges_of_pharmaceutical_patent_expiry_a_case_study_of_Lipitor

- Pfizer’s Big Problem: Lipitor Patent Expiration – Pharmacy Times, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.pharmacytimes.com/view/pfizers-big-problem-lipitor-patent-expiration

- “To patent or not to patent? the case of Novartis’ cancer drug Glivec in India” – PMC, accessed August 6, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3884017/

- Plavix fzzranchise in jeopardy – PMC, accessed August 6, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7096798/

- Former Bristol-Myers Squibb Senior Vice President Indicted for Lying to the Federal Government About Popular Blood-Thinning Drug – Department of Justice, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.justice.gov/archive/atr/public/press_releases/2008/232525.htm

- Sun Pharma may earn $250 300 mn in 6 months from Gleevec generic – BusinessToday, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.businesstoday.in/industry/pharma/story/sun-pharma-may-earn-250-300-million-in-six-months-from-gleevec-generic-55277-2015-12-04

- Putting the Genie Back in the Bottle – Apotex Petitions FDA to Recognize Remaining 180-Day Exclusivity for Generic PLAVIX Launched At-Risk, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.thefdalawblog.com/2008/02/putting-the-gen/

- Apotex Announces Launch of Generic Clopidogrel, Flouting Settlement Agreement, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/542538

- Trends in use of Lipitor after introduction of generic atorvastatin, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.gabionline.net/generics/research/Trends-in-use-of-Lipitor-after-introduction-of-generic-atorvastatin

- Pfizer Reports Fourth-Quarter and Full-Year 2012 Results; Provides 2013 Financial Guidance, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.pfizer.com/news/press-release/press-release-detail/pfizer_reports_fourth_quarter_and_full_year_2012_results_provides_2013_financial_guidance

- Cost savings from the use of generic Gleevec (imatinib), accessed August 6, 2025, https://gabionline.net/generics/research/Cost-savings-from-the-use-of-generic-Gleevec-imatinib

- Novartis Loses Historic India Patent Case On Cancer Drug Glivec, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.asianscientist.com/2013/04/features/novartis-loses-historic-india-patent-case-cancer-drug-glivec-2013/