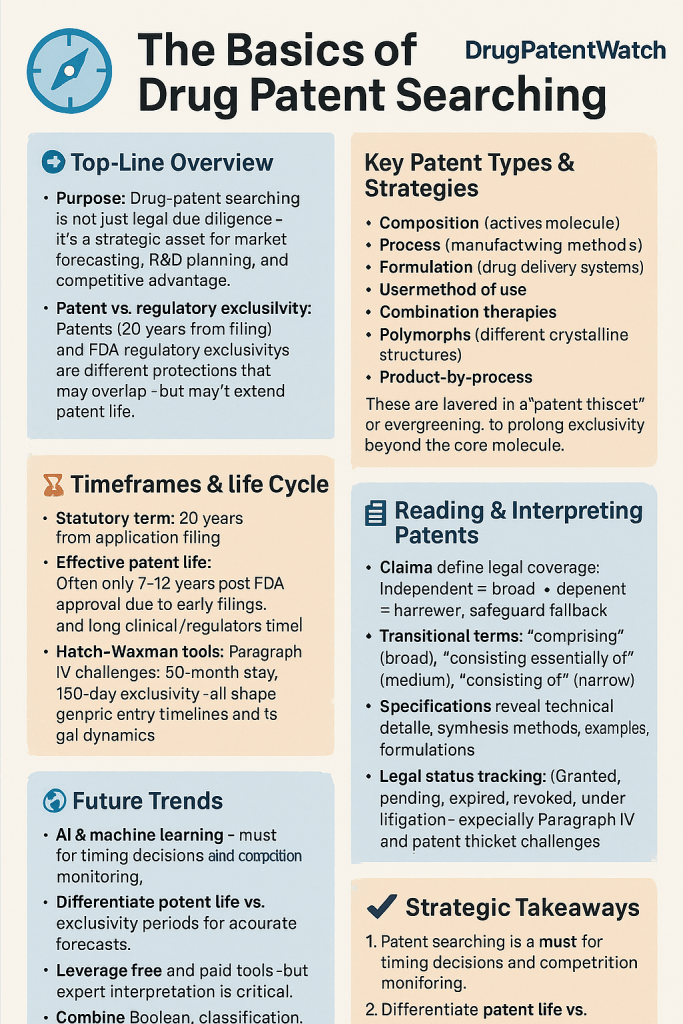

The pharmaceutical industry operates within a fiercely competitive and highly regulated environment where intellectual property, particularly drug patents, forms the bedrock of innovation and market exclusivity. Understanding the intricacies of drug patent searching is not merely a legal formality; it is a critical strategic imperative that can define a company’s success or failure. For business and pharmaceutical professionals, mastering this domain means transforming complex legal and technical data into actionable intelligence, enabling informed decisions that drive competitive advantage.

The Unseen Battleground: Why Drug Patents Define the Pharmaceutical Landscape

In the high-stakes world of drug development, patents are more than just legal documents; they are the very engine that propels innovation. They represent a fundamental economic model that allows pharmaceutical companies to undertake monumental risks and investments in the pursuit of life-saving therapies.

The Indispensable Role of Patents in Pharmaceutical Innovation

Drug patents, a vital form of intellectual property, grant their holders exclusive rights to sell a newly developed drug for a specified period, typically 20 years from the date of patent application filing.1 This exclusivity is not a luxury but a necessity. The pharmaceutical research and development (R&D) pipeline is notoriously long, expensive, and fraught with failure. Developing a new medicine can take 10-15 years and cost an average of USD 2.6 billion, with only one or two out of every 10,000 compounds successfully reaching the market. Without the prospect of exclusive market rights, the financial rationale for such high-stakes investments would largely dissipate, making it nearly impossible for companies to recoup their substantial R&D outlays and generate the profits necessary to reinvest in future discoveries.2

This protective mechanism serves as a powerful catalyst for innovation, encouraging significant investment in the development of novel drugs.7 It enables companies to maximize profits from successful treatments, which in turn attracts investors early in the development process to fund the costly clinical trials required for regulatory approval. This incentive structure is particularly vital for areas like orphan diseases, which affect fewer than 200,000 people annually in the U.S..2 For such conditions, additional exclusivity periods and greater flexibility in pricing are often granted, further encouraging drug companies to invest in treatments for smaller patient populations that might otherwise be less profitable. The very existence of these exclusive rights makes the massive R&D investments economically viable, forming the foundation of the current pharmaceutical innovation model.

The patent system operates on a fundamental “bargain”: in exchange for government-backed protection, the inventor must fully disclose enough detail about the invention so that others can understand and replicate it once the patent term expires. This public disclosure, while eventually leading to generic competition, simultaneously fuels further innovation by adding to the collective body of technical knowledge. However, this dual role of patents—as both catalysts for innovation and temporary barriers to generic competition —highlights a fundamental tension in public health policy: how to foster breakthrough discoveries while ensuring timely access to affordable medicines. This inherent conflict is a recurring theme that shapes the entire pharmaceutical landscape.

Navigating the Dual Pillars: Patents vs. Regulatory Exclusivities

A common point of confusion in the pharmaceutical industry is the distinction between patents and regulatory exclusivities. While both provide market protection, they are distinct legal instruments that operate under different authorities and rules.

Patents are property rights issued by the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) to an inventor, granting the right to exclude others from making, using, offering for sale, or selling the invention for a limited time, generally 20 years from the date of patent application filing.1 Regulatory exclusivity, conversely, refers to exclusive marketing rights granted by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) upon the approval of a drug. This prevents the submission or effective approval of generic applications for a specified period.4

A crucial point to grasp is that exclusivity periods are not added to the patent life. They are separate legal mechanisms that can run concurrently with a patent or independently. This distinction is vital for accurate market forecasting and competitive analysis. The primary purpose of exclusivity is to balance new drug innovation with generic drug competition. Exclusivity is granted upon approval if statutory requirements are met, with durations varying based on the type of exclusivity, such as New Chemical Exclusivity, Orphan Drug Exclusivity, or Pediatric Exclusivity.4

The fact that patents and exclusivities may or may not run concurrently and may or may not encompass the same claims indicates a deliberate strategic layering of protection by innovator companies. This is not an accidental outcome; it is a calculated effort to maximize market exclusivity. The distinction and potential non-concurrency of these protections mean that generic manufacturers face a more complex landscape than simply waiting for a single patent to expire. They must navigate both patent expiry dates and various exclusivity periods, which significantly impacts their market entry timelines and strategies. This necessitates sophisticated intelligence to determine the true “loss of exclusivity” date for a drug.

Table 1: Patents vs. Regulatory Exclusivities (US)

| Feature | Patents (US) | Regulatory Exclusivities (US) |

| :— | :— |:— | | Scope of Protection | Protects the invention itself (e.g., composition, method of use, formulation, polymorph) | Grants exclusive marketing rights for the approved product/indication, preventing FDA approval of competitor drugs | | Primary Purpose | Incentivize R&D and recoup investment by granting a temporary monopoly | Balance new drug innovation with generic competition | | Standard Duration | 20 years from filing date | Varies by type (e.g., NCE: 5 years, Orphan: 7 years, Biologics: 12 years) | | Start Date | Can be issued or expire at any time during development, regardless of approval status | Granted only upon approval of a drug product if statutory requirements are met | | Challengeability | Subject to challenge (e.g., validity, infringement) | Cannot be legally challenged | | Link to FDA Orange Book | Listed in Orange Book | Listed in Orange Book |

Decoding the DNA of Drug Patents: Foundational Concepts

To effectively search and interpret drug patents, one must first grasp their fundamental building blocks. This section demystifies the core concepts, from the definition of a drug patent to the various types of inventions they protect.

What Exactly is a Drug Patent?

A drug patent is a legal document that grants an inventor the sole right to market their invention for a specified period, typically 20 years from the date of the patent application filing.1 It functions as a property right issued by the USPTO, allowing the patent holder to exclude others from making, using, offering for sale, or selling the invention throughout the United States or importing it into the country for a limited time.

Like any other invention, pharmaceutical innovations must meet stringent criteria to be patentable: they must be new (novel), useful, non-obvious, and sufficiently described.9 The non-obviousness requirement ensures that the invention is not merely an incremental or predictable development that would be apparent to someone with ordinary skill in the relevant technical field.

While the statutory patent term is generally 20 years from filing 1, the commercially impactful period after a drug receives regulatory approval is often considerably shorter. Companies frequently apply for patents long before clinical trials commence, to attract potential investors and secure funding needed for advancing the drug to later stages of clinical development.2 This early filing, while a business necessity, means that a significant portion of the 20-year patent term is consumed during the lengthy R&D and regulatory review processes. As a result, the effective patent period after a drug has received final approval is often around seven to twelve years.3 This substantial reduction in effective market exclusivity is a critical factor for business planning, driving companies to explore strategies like evergreening and patent term extensions to prolong their period of market dominance.

The Anatomy of a Patent: Understanding Key Components

A patent document is a complex legal and technical blueprint of an invention. Understanding its key components is essential for extracting meaningful intelligence.

The claims are arguably the most critical part of a patent. These are the legal statements that precisely define the scope of an invention’s protection, outlining what is new and unique and establishing the boundaries of intellectual property. They are typically written as a single, heavily punctuated sentence and appear towards the end of the issued patent or patent application. The precise wording of these claims is paramount, as they form the primary legal battleground for patent infringement and validity disputes.

- Independent Claims: These claims stand on their own, not referring to any other claim, and provide the broadest possible protection for the core invention.16 For example, a claim might state: “A composition, comprising a solvent, and a metal salt dissolved in the solvent”.

- Dependent Claims: These claims refer back to and incorporate the limitations of an independent claim, adding further features or limitations to narrow the scope of protection.16 They serve as more specific contingency positions, providing narrower protection that might be upheld even if a broader independent claim is challenged or invalidated. For instance, following the example above, a dependent claim could be: “The composition of claim 1, further comprising a pH-modifying substrate.” Dependent claims are not merely narrower fallback positions; they can also clarify and, in some instances, expand the understanding of the broader claim’s scope, as demonstrated in legal precedents where dependent claims helped interpret the breadth of an independent claim.

The choice of transitional phrases within claims (e.g., “comprising,” “consisting essentially of,” “consisting of”) significantly dictates the claim’s scope. “Comprising” is an open-ended term, meaning the invention includes the recited elements but may also include others, making it the broadest. “Consisting essentially of” represents a middle ground, indicating the invention includes the recited elements and is open to others that do not materially affect the novel properties of the claimed invention. This phrase proved critical in the Eye Therapies case, where its interpretation, informed by the patent’s prosecution history, led to a finding that brimonidine was the sole active ingredient. “Consisting of” is the most restrictive, meaning the invention includes only the recited elements.

Claim interpretation typically accords claims their plain and ordinary meaning, but an inventor can act as their own lexicographer to define terms within the patent. The prosecution history, which documents the dialogue between the applicant and the patent office, can profoundly influence this interpretation, especially when atypical meanings are asserted or when the scope of claims is ambiguous. The precise choice of transitional phrases directly impacts the scope of protection and can be the deciding factor in patent infringement litigation. Drafting strong patent claims for drug inventions is a meticulous process, akin to “sculpting a masterpiece,” requiring a deep understanding of prior art, legal precepts, and strategic foresight to create a “resilient and protective shield” for the drug invention.

The specification or detailed description provides a thorough explanation of the invention, including examples of how it can be used, and often includes illustrations. This section is where the “patent bargain” of public disclosure is fulfilled, ensuring that enough detail is provided for others to understand and replicate the invention once the patent term expires. It typically covers the chemical structure, synthesis methods, therapeutic uses, formulation details, and pharmacological properties of the drug.

Many patents describe the synthesis methods used to create the drug. These descriptions can range from general overviews to detailed, step-by-step procedures, including information on starting materials, reaction conditions, purification techniques, and yield optimization. The level of detail in the patent specification regarding synthesis methods directly impacts the ease with which generic manufacturers can “design around” the patent or develop their own non-infringing processes. A thorough specification, while fulfilling disclosure requirements, can inadvertently provide a roadmap for competitors.

The specification may also contain experimental data, presented as “working examples” (describing actual performed work or achieved results) or “prophetic examples” (describing predicted or simulated results). For pharmaceutical inventions, some data demonstrating a substantial likelihood of the invention working as a human pharmaceutical is generally required. Strategic analysis of the specification helps in identifying active ingredients, potential modifications, and planning synthesis routes. It also reveals the exact scope of protection, potential vulnerabilities, and ownership information. The requirement for the specification to be “sufficiently described” or to “fully disclose enough detail… so that others can understand and replicate it” is known as the “enablement” requirement in patent law. This ensures the public benefit of disclosure is met, even if it aids future competitors.

Drawings serve as visual aids that clarify complex processes and structures. Finally, a concise abstract provides a summary of the invention.27

Types of Pharmaceutical Patents: Beyond the Molecule

Pharmaceutical companies often pursue a multi-layered patent strategy, securing protection for various aspects of a drug to create a comprehensive “web of protection”. This approach involves different types of patents beyond just the active molecule.

- Composition of Matter Patents: These are considered the most valuable and fundamental patents in the pharmaceutical industry. They protect the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) itself, ensuring that no other company can manufacture, use, or sell the patented chemical entity without permission during the patent term.8

- Process Patents: These protect the method of producing a specific pharmaceutical product, focusing on innovative manufacturing procedures or chemical processes developed by companies.6 They are vital for enhancing efficiency and effectiveness in production.

- Use Patents (Method of Use): These protect specific uses of a known product, including newly discovered therapeutic uses for existing drugs. This encourages drug repurposing and optimizing existing pharmaceutical products.6

- Formulation Patents: These protect the unique combination of ingredients in a drug, including special carriers, delivery mechanisms, or packaging that optimizes the drug’s performance.6 Examples include time-release capsules or novel delivery systems that target drugs directly to affected organs.8

- Combination Patents: These cater to drugs that combine multiple active ingredients to create a new therapy. DrugPatentWatch analyses highlight the importance of patenting the combination as a whole, rather than focusing solely on individual components, to strengthen the patent position and discourage replication.

- Polymorph Patents: These protect different crystalline forms of a drug substance, which can exhibit distinct physical properties such as solubility or stability.

- Product-by-Process Patents: This type of claim protects a chemical or other process used to manufacture the drug, and importantly, it also confers protection against the importation of a product made by that patented process.

The existence of multiple patent types beyond the active ingredient (e.g., formulation, use, process, polymorphs) 6 directly enables “evergreening” strategies. This is a deliberate approach by innovator companies to extend the lifetime of their patent monopolies, often by surrounding an original inventive patent with numerous additional patents that may have limited or no inventiveness.7 This practice aims to prolong monopoly periods and delay generic drug entry.7 While some secondary patents protect “genuine follow-on innovation,” distinguishing this from strategic use to extend monopolies is often “very difficult”. This raises important questions about the true innovative value of some later-stage patents versus their primary role in market protection, highlighting a major point of controversy and policy debate within the pharmaceutical industry.

The Clock is Ticking: Patent Duration and Key Dates

Understanding the lifecycle of a patent and its associated key dates is fundamental for strategic planning in the pharmaceutical sector.

The standard patent term in the United States is generally 20 years from the date of the patent application filing.1 However, this statutory term often differs significantly from the

effective patent life. Due to the lengthy R&D and regulatory approval processes inherent in drug development, the effective patent period after a drug receives FDA approval is considerably shorter, typically ranging from 7 to 12 years.3 This disparity arises because companies often file patents very early in the development process to secure priority and attract necessary investment. This business imperative of early patenting to secure funding directly leads to a reduced commercially valuable period of exclusivity post-approval, creating a fundamental tension for innovators.

Several key dates are crucial for tracking a drug patent:

- Priority Date: This is the earliest date on which an inventor can establish a date of invention. It is critically important because it determines what references can be asserted as prior art against a patent application during its examination. In a “race to the patent office” system, the inventor with the earliest priority date generally wins the rights to the patent. The priority date may be the same as the initial filing date, or it can be claimed from an earlier-filed application, such as a provisional patent application.

- Filing Date: This is the date the patent application is formally submitted to the patent office. This date marks the beginning of the 20-year patent term.1

- Publication Date: Patent applications are typically published 18 months from their priority date.34 This public disclosure transforms a regulatory requirement into a powerful strategic intelligence tool. It provides a valuable intelligence opportunity, serving as an “early warning system” for competitive threats by allowing companies to systematically track new filings and gain insights into competitor R&D pipelines years before products reach the market.

- Grant Date: This is the date the patent office officially grants the patent. It is distinct from the priority date.

- Expiration Date: This is the date the patent protection ends, opening the door for generic competition.2

The Regulatory Compass: FDA’s Role and Market Exclusivities

The pharmaceutical landscape in the United States is heavily influenced by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and its regulatory exclusivities. These mechanisms interact intricately with patents to shape market dynamics, with a particular focus on the landmark Hatch-Waxman Act.

The Orange Book and Purple Book: Your Essential Guides

For anyone seeking to determine the patent and exclusivity status of a drug in the United States, two primary governmental resources are indispensable: the FDA’s Orange Book and the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) databases.

The FDA’s Orange Book, officially known as “Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations,” stands as the authoritative U.S. database listing all FDA-approved non-biologic (small-molecule) drugs.4 It meticulously links approved drug products to their associated patents and regulatory exclusivity information.4 Patents eligible for Orange Book listing generally cover the drug substance (active ingredient), the drug product (formulation and composition), or the approved method of use.12 Crucially, patents claiming the process or manufacture of the drug substance, its packaging, or metabolites or intermediates are

not eligible for listing.12 The Orange Book is not merely a list; it serves as a de facto roadmap for generic manufacturers. By analyzing patent expiration dates and regulatory exclusivity periods within it, companies can identify optimal timing for market entry with generic or biosimilar products. This precise timing is critical, as entering too early risks patent infringement litigation, while entering too late means missing the first-to-file advantage that can secure a period of market exclusivity for generic manufacturers.

For biological products, such as vaccines, blood components, and monoclonal antibodies, the FDA maintains a separate publication known as the Purple Book.12 This database lists FDA-approved biological drugs and provides valuable insights into their intellectual property landscape, including patent details.

These books are critical resources for a wide range of stakeholders, including healthcare providers, pharmacists, and drug manufacturers. For drug manufacturers, the information on a drug’s patents and regulatory exclusivities is vital for determining when and whether generic competition can occur.12 The requirement for branded companies to list patents in the Orange Book 4 directly enables the “Paragraph IV certification” mechanism and the subsequent “30-month stay” on generic approvals if litigation ensues.38

Understanding Regulatory Exclusivities: A Shield Beyond Patents

Beyond patents, the FDA grants various types of exclusivities upon drug approval, which function as distinct shields of market protection. These exclusivities run for specific durations and, importantly, are not added to the patent life.4

Key types of regulatory exclusivities include:

- New Chemical Entity (NCE) Exclusivity: This provides 5 years of exclusivity and is granted to drugs containing no active moiety that has been previously approved by the FDA.4 It bars the FDA from accepting for review any Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) or 505(b)(2) application for a drug containing the same active moiety during this period.

- Orphan Drug Exclusivity (ODE): This grants 7 years of exclusivity for drugs designated and approved to treat diseases or conditions affecting fewer than 200,000 people in the U.S..2

- “Other” Exclusivity: This provides 3 years of exclusivity for a “change” to an approved drug if the application or supplement contains reports of new clinical investigations (not bioavailability studies) conducted or sponsored by the applicant and deemed essential for approval.4

- Pediatric Exclusivity (PED): This adds 6 months to existing patents and exclusivities.4 It serves as an incentive for companies to conduct studies on the use of their drugs in pediatric populations, ensuring that new treatments are available for all age groups.

- Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA) Exclusivity: For biological products, this grants 12 years of market exclusivity for reference products, with an additional 1 year for the first interchangeable biosimilar.

A critical distinction for generic manufacturers is that data exclusivity “cannot be legally challenged” , whereas patents are “subject to challenge”. This means that even if a generic company believes a patent is invalid, they may still be prevented from accessing the originator’s clinical trial data for their own applications until the data exclusivity period expires. This creates a different strategic hurdle compared to patent challenges, significantly influencing the timing and viability of generic entry. The ongoing debate around data exclusivity durations, with some advocating for the U.S. to adopt the European Union’s longer 10-11 year periods , highlights the continuous policy tension between incentivizing pharmaceutical innovation (through longer exclusivity) and promoting timely access to affordable medicines (through shorter exclusivity). This dynamic regulatory landscape requires continuous monitoring by business professionals.

Table 3: Specific Types of Exclusivities and Their Durations (US)

| Exclusivity Type | Standard Duration | Key Characteristics |

| New Chemical Entity (NCE) 4 | 5 years | Granted for drugs with no previously approved active moiety; bars FDA from accepting ANDAs for drugs with the same active moiety. |

| Orphan Drug Exclusivity (ODE) 4 | 7 years | Granted for drugs treating rare diseases (affecting <200,000 people in the U.S.). |

| “Other” Exclusivity 4 | 3 years | Granted for new clinical investigations (not bioavailability studies) essential for approval of a change to an approved drug. |

| Pediatric Exclusivity (PED) 4 | 6 months (added to existing IP) | Incentivizes pediatric studies; adds to existing patent or exclusivity terms. |

| 180-Day Generic Exclusivity 4 | 180 days | Granted to the “first” generic applicant to file a Paragraph IV certification and successfully challenge a listed patent. |

| Biologics (BPCIA) | 12 years (reference product) | Market exclusivity for reference biologics, with 1 year for first interchangeable biosimilar. |

The Hatch-Waxman Act: A Game-Changer for Generics

The Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984, commonly known as the Hatch-Waxman Act, fundamentally reshaped the pharmaceutical industry. Its primary purpose was to facilitate the approval of generic drugs while simultaneously providing incentives for innovator companies to continue their research and development efforts.4 The Act streamlined the approval process for generics by allowing Abbreviated New Drug Applications (ANDAs) based on a demonstration of bioequivalence to the brand-name drug, rather than requiring costly and time-consuming full clinical trials.13

Key provisions of the Hatch-Waxman Act include:

- Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA): This streamlined pathway allows generic drug manufacturers to seek approval by demonstrating that their product is pharmaceutically equivalent and bioequivalent to a Reference Listed Drug (RLD), which is the brand-name drug it seeks to replicate.6 The ANDA submission must include comprehensive data proving this bioequivalence, along with detailed information about the generic drug’s quality, manufacturing process, and sameness in terms of active ingredients, dosage form, strength, and route of administration.

- Paragraph IV Certification: This is a high-stakes mechanism enabling generic manufacturers to challenge the validity, enforceability, or infringement of a brand-name drug’s listed patents.6 By filing a Paragraph IV certification, a generic company asserts that its proposed product will not infringe any valid, enforceable patent.

- 30-Month Stay: If a branded company files a patent infringement lawsuit within 45 days of receiving a Paragraph IV certification notice, the FDA is required to postpone the generic drug’s approval for 30 months.38 This period allows the patent litigation to proceed and typically expires well before generic entry would otherwise occur. This mechanism creates a structured arena for competition, often leading to significant litigation between innovator and generic companies.

- 180-Day Exclusivity: This serves as a significant incentive granted to the “first” generic applicant to file a substantially complete ANDA containing a Paragraph IV certification and successfully challenge a listed patent.4 This 180-day period of market exclusivity can begin either from the date the first generic begins commercial marketing of the drug or from the date of a court decision favorable to the generic. During this period, the FDA cannot approve subsequently submitted ANDAs for the same drug, even if they are otherwise ready for approval.

The Hatch-Waxman Act simultaneously incentivizes generic entry through streamlined approval and 180-day exclusivity, while providing mechanisms for branded companies to defend their patents through Paragraph IV challenges and the 30-month stay.4 This creates a dynamic, often litigious, environment. Pharmaceutical patent litigation, particularly Paragraph IV challenges, becomes the “critical pathway through which most generic launch timelines are ultimately determined”. Analyzing litigation data, therefore, provides crucial insights into the timing and likelihood of generic entry, elevating legal battles from mere events to primary predictive indicators for market dynamics.

Table 2: Key Provisions of the Hatch-Waxman Act

| Provision | Description | Purpose/Impact |

| Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) 13 | Streamlined approval process for generic drugs, requiring demonstration of bioequivalence to a brand-name drug. | Facilitates faster and less expensive generic entry by avoiding full clinical trials. |

| Paragraph IV Certification 42 | Generic manufacturer certifies that listed patents are invalid or not infringed by their proposed generic product. | High-stakes strategy for early generic market entry; triggers potential litigation. |

| 30-Month Stay 41 | If branded company sues within 45 days of Paragraph IV notice, FDA postpones generic approval for 30 months. | Allows time for patent litigation to resolve; delays generic market entry. |

| 180-Day Exclusivity 42 | Exclusive right to market a generic drug for 180 days, granted to the first Paragraph IV filer who successfully challenges a patent. | Incentivizes early patent challenges; provides significant market advantage to the first generic entrant. |

Mastering the Hunt: Essential Tools and Techniques for Drug Patent Searching

Effective drug patent searching is both an art and a science. It requires not only knowing where to look but also how to craft precise queries and interpret the vast amount of information available. This section outlines the essential tools and sophisticated methodologies that transform basic information retrieval into strategic intelligence gathering.

Publicly Accessible Databases: Your Starting Point

For initial reconnaissance and foundational research, several publicly accessible databases offer a wealth of patent information:

- USPTO Patent Public Search: This is the official and definitive database for U.S. patents and published applications.6 It replaced older legacy tools, offering enhanced access to prior art and supporting a variety of search criteria, including applicant/assignee name, inventor name, publication date ranges, and keywords, with Boolean and proximity operators.45 It also provides access to the Global Dossier, which contains file histories from participating intellectual property (IP) offices, and information on Patent and Trademark Resource Centers (PTRCs) for in-person assistance.

- EPO Espacenet: A comprehensive database from the European Patent Office, Espacenet provides access to millions of patent documents, including worldwide and UK patents.47 It offers technical, legal, and business information, allowing users to track emerging trends and check patent validity.

- WIPO PATENTSCOPE: The World Intellectual Property Organization’s (WIPO) online facility is a global gateway for searching millions of patent documents, including published international Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) applications.6 It supports diverse search criteria such as keywords, International Patent Classification (IPC) codes, chemical compounds, and numbers across multiple languages, offering WIPO Translate for instant translation. PATENTSCOPE also includes predefined searches (e.g., for AI or COVID-19 related patents) and provides access to programs like ASPI (Access to Specialized Patent Information) for developing countries.

- Google Patents: A widely used, free patent search engine that indexes patents from various offices globally. It is a convenient tool for quick lookups and general exploration, often serving as a starting point for identifying patent expiration dates.

- I-MAK’s Drug Patent Book: This public resource provides a comprehensive list of patents for top-selling U.S. drugs, detailing patent family grouping, patent type, Orange/Purple Book listing, and a brief description of what each patent covers. It aims to improve transparency and inform policy debates on drug prices.

The widespread availability of robust free databases like USPTO Patent Public Search, Espacenet, and PATENTSCOPE 6 democratizes access to fundamental patent information. This empowers smaller companies, academic researchers, and even the public to conduct initial due diligence and competitive analysis, significantly lowering the barrier to entry for understanding the IP landscape.

Specialized Commercial Platforms: Unlocking Deeper Insights

While public databases offer a solid foundation, specialized commercial platforms provide curated data, advanced analytics, and integrated intelligence capabilities essential for a deeper competitive edge.

- DrugPatentWatch: This platform is a valuable resource offering insights into global drug patents, patent expiration, exclusivity status, and competitive landscapes for pharmaceuticals. It provides data on drug patents, litigation histories, detailed patent and generic drug manufacturer information, and alerts on upcoming patent expirations.53 DrugPatentWatch incorporates data directly from the FDA, USPTO, and other global government sources, updated frequently—often daily—to ensure fresh and accurate information.53 It assists users in identifying market entry opportunities, uncovering prior art in expired and abandoned patents, and tracking first generic entrants. The platform’s focus on providing “insights” and “strategic angles” indicates an emphasis on clear presentation of complex data.30

- Cortellis: A comprehensive platform that combines a vast collection of pharmaceutical industry data and life science content, including news, drug and medical device information, clinical trials, literature, patents, licensing, and company data. It allows for highly flexible patent searches by therapeutic area, company, patent numbers, classification codes, technology, and keywords.

- Derwent Innovation (Clarivate Analytics): This platform provides access to the Derwent World Patents Index (DWPI), a curated patent database featuring editorially enhanced titles and abstracts, specialized subject matter classification coding, and proprietary patent invention-centric family building. Clarivate Patent Intelligence Solutions help organizations evaluate patentability and freedom-to-operate with confidence, and optimize patent portfolios.

- LexisNexis TotalPatent One®: A robust patent search platform offering comprehensive research capabilities across issued patents, published patent applications, utility models, and design patents globally. It boasts over 135 million documents from 107 authorities, including full-text from 67 authorities, with English translations for over 100 million documents. LexisNexis PatentSight® further enhances this with innovation analytics and visualization tools like sunburst charts and advanced patent family charts.

- PatBase (Minesoft/RWS Group): A global patent database covering over 106 authorities, hosting more than 140 million patent and related documents organized into patent families to reduce duplication and save search time. It offers specialized tools like Chemical Explorer for simplifying chemical information searching from patent full text, images, and R-group table compounds.

- PatSnap: This platform connects 116 jurisdictions, 140 million patents, and over 250 million innovation data points from around the world. PatSnap Analytics makes it possible to perform highly targeted global searches that generate reliable, detailed innovation intelligence, helping companies manage risk, spot new opportunities, defend innovations, and monitor the competitive landscape.

- WIPS Global: This service integrates artificial intelligence technology with its system, providing patent analysis services for all levels of users. Its database is optimized for various patent-related tasks, including trial, litigation, generics, chemical compounds, and IP strategy establishment, assisting patent practitioners in efficient performance.

- PatentsKart: This platform offers specialized drug patent linkage databases, including user-friendly and accurate Orange Book and Purple Book data, as well as comprehensive Japanese pharmaceutical patents with their expiration dates. This information is crucial for understanding market exclusivity and potential competition in the Japanese market.

These commercial platforms move beyond simply providing raw data by offering curated data, advanced analytics, and integration with other business intelligence tools.49 This reflects the industry’s need for

actionable intelligence, not just raw data. The ability of these platforms to integrate patent data with other business intelligence sources—such as CRM platforms, market data, and clinical trial information 49—allows for a holistic view of the market. This integrated approach is crucial for comprehensive competitive intelligence and strategic decision-making, providing a significant competitive advantage.

Table 4: Overview of Major Drug Patent Databases

| Database | Type | Primary Focus/Benefits | Key Features |

| USPTO Patent Public Search 6 | Public | Official U.S. patent and application database; enhanced access to prior art. | Boolean/proximity operators, field-specific searching, Global Dossier access. |

| EPO Espacenet 47 | Public | Comprehensive European and worldwide patent documents; technical, legal, business info. | Track emerging trends, check patent validity, millions of documents. |

| WIPO PATENTSCOPE 6 | Public | Global patent search, including PCT applications; multilingual support. | Keywords, IPC, chemical compounds, WIPO Translate, predefined searches. |

| DrugPatentWatch 53 | Commercial | Global drug patent intelligence, expiration, exclusivity, competitive landscapes. | Litigation histories, generic manufacturer info, alerts, market entry opportunities. |

| Cortellis | Commercial | Comprehensive pharma/life science data: news, drugs, trials, literature, patents. | Search by therapeutic area, company, patent numbers, classification codes, keywords. |

| Derwent Innovation 36 | Commercial | Curated patent database (DWPI) with editorial enhancements; patent family building. | Evaluate patentability, FTO, optimize portfolios, extensive data integration. |

| LexisNexis TotalPatent One® 57 | Commercial | Extensive global patent coverage; full-text and English translations. | PatentSight analytics, sunburst charts, advanced patent family charts. |

| PatBase | Commercial | Global patent database organized into patent families; chemical search tools. | Covers 106+ authorities, Chemical Explorer for chemical info searching. |

| PatSnap | Commercial | Connects global patent and innovation data points; targeted searches. | Risk management, opportunity spotting, competitor monitoring, innovation intelligence. |

| WIPS Global | Commercial | AI-integrated patent analysis; optimized for litigation, generics, chemical compounds. | AI technology, specialized databases for patent works, IP strategy. |

| PatentsKart | Commercial | Specialized drug patent linkage databases (Orange/Purple Book, Japan Pharma). | User-friendly search, patent expiration dates, transparency for biologics patents. |

Crafting Your Search Strategy: The Art of Keywords and Operators

Effective patent searching goes beyond simply typing a few words into a search bar. It involves a strategic approach to query construction, leveraging various operators to refine results and ensure comprehensive coverage.

Before diving into databases, it is crucial to define your search scope clearly. This involves identifying the core components of your invention or area of interest, its unique properties, and novel aspects. Using clear and precise language in this initial definition will maximize the effectiveness of your subsequent patent search.

Keyword selection is a critical first step. Think broadly and creatively, including scientific terms, common names, synonyms, and related concepts. Consider different ways an invention might be described.

To refine and expand your search results, a mastery of search operators is essential:

- Boolean Operators:

- AND: Narrows results by requiring all specified terms to be present in the search results (e.g., “drug AND patent”).60

- OR: Expands results by requiring at least one of the specified terms to be present (e.g., “cancer OR oncology”).60

- NOT (or ANDNOT): Excludes terms, refining specificity by removing documents containing the specified term (e.g., “tablet NOT capsule”).60

- Proximity Operators: These operators find terms within a specified number of words from each other (e.g., “drug NEAR/5 delivery”). This is particularly useful when searching for concepts that are frequently mentioned together but not always adjacent, allowing for the capture of relevant documents that might otherwise be missed.60

- Wildcards and Truncation: Symbols such as an asterisk (), question mark (?), or dollar sign ($) can replace one or more characters in a word. This allows for capturing variations, different spellings, or plural forms (e.g., “pharmaceutic” would yield results for pharmaceutical, pharmaceutics, etc.).60

- Phrases: Using quotation marks around a set of words ensures that the search engine finds the exact phrase (e.g., “gene therapy”).

- Field-Specific Searching: Many databases allow users to target searches within specific fields of a patent document, such as the title (.ti.), abstract (.ab.), claims (.clm.), or assignee name (.as.). This granular control enables highly precise analysis and can significantly improve the relevance of search results.

The strategic combination of Boolean, proximity, and truncation operators 60 is not just about finding patents, but about balancing

precision (the relevance of the results) and recall (the completeness of the results). This highlights the iterative and strategic nature of effective patent searching, where the goal is to find all relevant documents without being overwhelmed by irrelevant ones.

Table 5: Common Patent Search Operators and Their Use

| Operator | Function | Example | Impact on Results |

| Boolean Operators | |||

| AND 60 | Requires all terms to be present. | drug AND delivery | Narrows results, increases precision. |

| OR 60 | Requires at least one term to be present. | cancer OR oncology | Expands results, increases recall. |

| NOT (or ANDNOT) 60 | Excludes specific terms. | tablet NOT capsule | Narrows results, refines specificity. |

| Proximity Operators | |||

| NEAR (e.g., NEAR/5) 60 | Finds terms within a specified distance of each other. | “drug” NEAR/5 “formulation” | Finds related concepts mentioned closely, improving relevance. |

| Wildcards/Truncation | |||

| * (asterisk) 60 | Replaces one or more characters at the end of a word. | pharmaceutic* | Finds pharmaceutical, pharmaceutics, etc., capturing variations. |

| ? (question mark) | Replaces a single character. | color? | Finds color, colour, etc., capturing spelling variations. |

| Phrases | |||

| “” (quotation marks) | Searches for an exact phrase. | “gene therapy” | Ensures terms appear together in the specified order. |

Navigating Classification Systems: IPC, CPC, and USPC

Beyond keywords, patent classification systems offer a powerful, structured approach to searching, especially when dealing with complex technical fields or international documents.

Patent classification systems—such as the International Patent Classification (IPC), Cooperative Patent Classification (CPC), and US Patent Classification (USPC)—categorize patents based on their technical features. This systematic categorization makes it significantly easier to find relevant prior art in specific technological areas. These systems provide language-independent symbols for classification, which is a key advantage for global patent searching.62

- IPC (International Patent Classification): Established by the Strasbourg Agreement, the IPC is a hierarchical system of language-independent symbols used globally for classifying patents and utility models according to different areas of technology.62 WIPO provides various resources, including IPCCAT (a categorization assistance tool) and STATS (a tool for IPC predictions based on statistical analysis), to assist users with IPC classification and searching.

- CPC (Cooperative Patent Classification): Jointly managed by the European Patent Office (EPO) and the USPTO, the CPC is an extension of the IPC, offering a finer subdivision with approximately 250,000 entries.61 It is largely compatible with the IPC, and CPC codes can often be easily converted to their hierarchically higher IPC equivalents.

- USPC (US Patent Classification): This is the classification system historically used by the USPTO. While still relevant for older U.S. patents, the CPC is increasingly becoming the standard for cooperative classification.

Leveraging classification codes involves identifying the primary classification codes relevant to your invention and using them to search within patent databases. Cross-references within these systems can help uncover related categories that might not be immediately obvious from keyword searches. The increasing harmonization of classification systems, such as the CPC, indicates a clear trend toward greater standardization and transparency in patent information worldwide.

The use of classification systems, with their language-independent symbols 62, is a powerful tool for overcoming language barriers in global patent searching. This provides a critical advantage over keyword-only searches, which can be limited by translation nuances and terminology differences. Furthermore, leveraging classification codes is a strategic method for assessing novelty (ensuring an invention is truly new) and conducting Freedom-to-Operate (FTO) analyses (ensuring a product does not infringe existing patents). By categorizing patents by technical features, classification systems allow for a highly targeted and comprehensive review of the technological landscape, directly supporting these critical business decisions.

Table 6: Essential INID Codes for Drug Patent Documents

| INID Code | Description | Significance for Drug Patents |

| (11) 27 | Number of the patent document (publication number) | Unique identifier for the patent; essential for direct lookup. |

| (21) 27 | Number given to the application (application number) | Identifies the specific patent application. |

| (22) 27 | Date of making application (filing date) | Crucial for determining the 20-year patent term and priority. |

| (31) 27 | Number assigned to priority application | Links to earlier applications from which priority is claimed. |

| (32) 27 | Date of filing of priority application (priority date) | The earliest date of invention, critical for prior art assessment. |

| (33) | Country in which priority application was filed | Indicates the origin of the priority claim. |

| (43) 27 | Publication day of unexamined application | Date the patent application became publicly available (often 18 months from priority). |

| (45) | Date of publication by printing of a granted patent | Date the patent was officially granted. |

| (51) | International Patent Classification (IPC) | Indicates the primary technical classification of the invention. |

| (54) 27 | Title of the invention | Provides a concise overview of the patent’s subject matter. |

| (57) 27 | Abstract or claim | Summarizes the invention and its scope. |

| (71) 27 | Name of applicant | Identifies the current owner of the patent application. |

| (72) 27 | Name of inventor | Identifies the individual(s) who conceived the invention. |

The Chemical Code: Searching by Structure (SMILES, Markush)

For chemical and pharmaceutical inventions, searching by chemical structure is often far more precise and effective than keyword searching alone. Chemical compounds can have multiple names, complex descriptions, or subtle structural variations that keyword searches might miss entirely.68

Chemical structure representations form the basis of these searches. Queries typically begin with either a graphical depiction (e.g., molecular formulas, skeletal structures, 2D/3D models) or a textual notation (e.g., SMILES notation, Mol files).

- SMILES Notation: The Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System (SMILES) is a textual representation of chemical structures that allows for clear and concise description of molecules.36 AI-driven platforms like PatSight can automate the extraction of key data from chemical patents and deliver results in formats like CSV or SDF files with SMILES notation.

- Markush Structures: These are powerful, generic representations used extensively in patent claims to define a broad class or family of related chemical compounds.68 Markush structures combine both visual and textual elements to describe a molecular backbone with variable substituents at specific positions.70 A single Markush formula allows inventors to claim a wide variety of similar compounds in one claim, effectively preventing competitors from making minor molecular modifications to bypass the patent. Some Markush structures can be so general that they encompass millions of actual chemical entities.71

Search algorithms and matching criteria for chemical structure searches rely on specialized algorithms and databases capable of understanding and interpreting these complex chemical structures, including Markush structures. Users can specify matching criteria such as exact match, substructure match (finding records containing a specified structural fragment), or a similarity threshold.

Specialized databases for chemical structure search, such as CAS Scientific Patent Explorer, allow for direct searching of patents by chemical structure, including Markush searches. Commercial databases like STN (which includes CASLINK, REGISTRY, MARPAT, and CAPLUS) are also crucial for this type of detailed chemical patent searching.

Chemical structure searching, especially with Markush structures, is paramount for chemical and pharmaceutical patents. It allows for highly precise prior art searches (to determine novelty) and infringement analyses (to ensure freedom-to-operate), as it accounts for the vast number of chemical variations that keyword searches alone might miss.69 The unique nature of chemical claims necessitates this specialized approach. Furthermore, the increasing role of AI in chemical structure recognition, with platforms like PatSight automating “accurate chemical structure recognition” and tools like MarkushGrapher using multimodal approaches to interpret complex Markush structures , signifies a significant technological advancement. AI is making complex chemical patent searching more efficient and accurate, enhancing the capabilities of patent intelligence.

Beyond the Surface: Interpreting Patent Documents for Strategic Advantage

Raw patent data is merely the starting point. The true value lies in interpreting these complex documents to extract strategic intelligence. This section delves into the nuances of patent claims, specifications, legal statuses, and prosecution histories, transforming the reader into a patent intelligence maestro.

Deconstructing Patent Claims: The Heart of Protection

Patent claims are the legal statements that define the precise scope of an invention’s protection. They are typically written as a single, heavily punctuated sentence and appear towards the end of the patent document. These claims represent the legal boundaries of what the patent owner can exclude others from doing.

- Independent Claims: These are the broadest claims in a patent, standing alone without referring to any other claim. They define the core invention in its most expansive terms, providing the inventor with the most comprehensive protection.16

- Example: “A composition, comprising a solvent, and a metal salt dissolved in the solvent.”

- Dependent Claims: These claims refer back to and incorporate all the limitations of a preceding independent or dependent claim, adding further specific features or limitations to narrow the scope of protection.16 They serve as crucial fallback positions in case broader claims are challenged or invalidated, offering more specific protection that might be upheld.

- Example: “The composition of claim 1, further comprising a pH-modifying substrate in an amount sufficient to adjust the pH to a value of from 3.5-5.”.

The transitional phrases used in claims, such as “comprising,” “consisting essentially of,” and “consisting of,” are pivotal in defining the claim’s scope.

- “Comprising” is an open-ended term, meaning the invention includes the recited elements but may also include other unrecited elements. This provides the broadest scope.

- “Consisting essentially of” represents a middle ground. It means the invention includes the recited elements and may include others, but only if those others do not materially affect the basic and novel properties of the claimed invention. The interpretation of this phrase can be highly nuanced and heavily influenced by the patent’s prosecution history, as illustrated in the Eye Therapies case. In that case, the Federal Circuit determined that “consisting essentially of” meant brimonidine as the sole active ingredient, based on arguments made during prosecution to distinguish the invention from prior art. This demonstrates how the precise choice of transitional phrases directly impacts the scope of protection and can be the deciding factor in patent infringement litigation.

- “Consisting of” is a closed-ended term, meaning the invention includes only the recited elements, making it the narrowest in scope.

Claim interpretation typically accords claims their plain and ordinary meaning, but an inventor has the right to act as their own lexicographer to define terms within the patent. The prosecution history, which documents the entire examination process, can significantly influence this interpretation, particularly when terms have an “atypical meaning” or when the scope of claims is ambiguous. Courts often refer to this history to understand the inventor’s intent and how claims were narrowed or defined during examination.

Drafting strong patent claims for drug inventions is a highly strategic endeavor, often likened to “sculpting a masterpiece”. It demands a deep understanding of existing prior art, adherence to legal precepts, and strategic foresight to create a “resilient and protective shield” for the drug invention. This process is not merely a technical exercise but a critical strategic one that directly impacts the defensibility and commercial value of a pharmaceutical innovation.

Unpacking the Specification: Unveiling the Invention’s Secrets

While claims define the legal boundaries, the specification (or detailed description) provides the technical blueprint of the invention. This section offers a thorough description, including the chemical structure, synthesis methods, therapeutic uses, formulation details, and pharmacological properties of the drug. It is within the specification that the “bargain” of public disclosure is fulfilled, requiring the inventor to provide enough detail for others to understand and replicate the invention once the patent term expires. This is known as the “enablement” requirement in patent law, ensuring that the public benefits from the disclosed knowledge, even if it aids future competitors.

Synthesis methods are frequently described in detail within patents, ranging from general overviews to step-by-step procedures. These descriptions often include crucial information on starting materials, reaction conditions, purification techniques, and strategies for yield optimization. The level of detail provided in the patent specification regarding synthesis methods directly impacts the ease with which generic manufacturers can “design around” existing patents or develop their own non-infringing processes. While fulfilling disclosure requirements, a thorough specification can inadvertently provide a roadmap for competitors seeking to enter the market.

The specification may also contain experimental data, presented as “working examples” (describing actual performed work or achieved results) or “prophetic examples” (describing predicted or simulated results). Prophetic examples, sometimes called “paper” or “hypothetical” examples, are included to demonstrate the invention’s applicability and support the breadth of the claims, even if the experiments have not yet been performed. For pharmaceutical inventions, some data demonstrating a substantial likelihood of the invention working as a human pharmaceutical is typically required.

Strategic analysis of the specification involves more than just reading; it means identifying the active ingredients, recognizing potential modifications, and planning alternative synthesis routes. This granular level of detail enables precise analysis of patent claims, helping to understand the exact scope of protection, identify potential vulnerabilities, and track ownership, which is crucial for assessing patent strength, potential infringement risks, and strategic competitive positioning.

Understanding Patent Legal Statuses: Active, Expired, Litigated, and More

A patent’s legal status is a dynamic indicator of its enforceability, market exclusivity, and susceptibility to generic competition. Continuous monitoring of these statuses is crucial for accurate competitive intelligence and risk assessment.

- Active/Granted/In Force: This status indicates that the patent is currently valid and enforceable, providing the patent holder with exclusive rights.

- Pending: The patent application has been published or is under examination, but the patent has not yet been issued or formally abandoned.

- Expired: The patent term has ended, and the protection it afforded has ceased.2 This status is a green light for generic competition, as it opens the door for other manufacturers to produce and sell their versions of the drug.

- Abandoned: A patent application or granted patent is no longer active, often due to the applicant’s failure to respond to office actions within specified timeframes or to pay required maintenance fees.74 In some circumstances, an abandoned application may be revived.

- Withdrawn: An application that was open to public inspection was formally withdrawn at the request of the applicant.

- Rejected: An application has been rejected by the patent examiner during the prosecution phase.

- Revoked/Invalidated: The patent has been declared invalid, either partially or wholly. This often occurs through opposition proceedings initiated by a third party or as a result of litigation.

- Lapsed/Ceased: This status often results from the non-payment of annual maintenance fees, leading to the invalidation of the patent.

- Litigated: The patent is currently involved in a legal dispute, such as an infringement suit or a Paragraph IV challenge.17 This is a key indicator for potential generic entry and requires close monitoring, as the outcome directly influences market timelines.

- Re-examined: A third party or the inventor has requested a re-examination of the patent to verify its patentability.

- Opposed: A third party has initiated an opposition proceeding to challenge the validity of a pending patent application or a granted patent.

- Pledged/Trust: These statuses indicate financial arrangements where the patent rights are used as collateral, similar to a mortgage.

Patents involved in litigation, particularly those subject to Paragraph IV challenges, are critical indicators for predicting generic drug launches. The outcome of this litigation directly dictates when a generic can enter the market, potentially even through “at-risk” launches where a generic manufacturer begins selling its product before patent litigation concludes, accepting the risk of potential damages if they are ultimately found to infringe. This makes litigation status a primary predictive variable for understanding market dynamics. A patent’s “active” status is not static; it can be challenged, abandoned, or invalidated. This dynamic nature means continuous monitoring of legal status is essential for accurate competitive intelligence and risk assessment, as the current legal vulnerability or strength of a patent must be continuously assessed.

The Power of Prosecution History: What Happened Behind the Scenes?

The prosecution history refers to the complete record of communications and actions between the patent applicant and the patent office during the examination process. This includes all office actions (rejections, objections), the applicant’s responses, any amendments made to the claims or specification, and the arguments presented to overcome rejections.

The significance of prosecution history is profound, particularly for interpreting patent claims. While claims are typically given their plain and ordinary meaning, the prosecution history can reveal instances where terms were given an “atypical meaning” or where the scope of claims was narrowed or defined during examination. Courts frequently refer to this history to understand the inventor’s intent and the precise scope of protection that was ultimately granted.

A compelling case example is Eye Therapies v. Slayback Pharma. In this case, the Federal Circuit Court of Appeals used the prosecution history of the ‘742 patent to interpret the transitional phrase “consisting essentially of” in the claims. During prosecution, Eye Therapies had amended its claims from “comprising” to “consisting essentially of” to distinguish its invention from prior art that disclosed combination therapies. The examiner, in allowing the claims, noted that this amendment meant the claimed methods “do not require the use of any other active ingredients in addition to brimonidine”. The court ultimately relied on this prosecution history to conclude that the phrase “consisting essentially of” in this specific context meant brimonidine as the sole active ingredient, thereby excluding other active ingredients from the scope of the claims. This case vividly illustrates how statements and amendments made during patent prosecution can significantly impact the interpretation of claim terms in subsequent litigation, potentially altering the scope of patent protection.

The prosecution history reveals the negotiation between the applicant and the patent office. It is not just about what was ultimately granted, but why it was granted and what scope was surrendered or clarified along the way. This provides invaluable context for assessing a patent’s true strength and potential vulnerabilities, offering a deeper understanding of its defensibility or susceptibility to challenges beyond its face value.

Turning Data into Gold: Strategic Applications of Patent Intelligence

For business professionals, patent data is not merely information; it is a strategic asset. Sophisticated analysis of patent intelligence can drive competitive advantage across various facets of the pharmaceutical business, from R&D to market entry and risk mitigation.

Competitive Intelligence: Tracking R&D Pipelines and Market Shifts

Patent intelligence serves as a powerful early warning system for competitive threats. By systematically monitoring and analyzing patent filings, companies can gain unprecedented insights into competitor research directions, technological innovations, and potential market entries years before products reach the market. This allows organizations to make informed decisions about their own R&D investments, potentially redirecting resources to more promising or less crowded therapeutic areas.

- Pipeline Monitoring: Tracking patent applications provides a window into competitor R&D pipelines, revealing their priorities, emerging therapeutic areas, and product development.36 For instance, the filing of initial composition of matter patents might indicate early-stage programs that will require development support in 1-2 years, while formulation patents might suggest programs approaching clinical development and commercial manufacturing. This allows for proactive rather than reactive R&D adjustments.

- Technology Trend Identification: Patent activity signals shifts in target selection within therapeutic areas, emerging modalities gaining traction (e.g., from small molecules to biologics), evolving approaches to addressing specific mechanisms of action, changing formulation and delivery technologies, and new manufacturing processes being adopted.

- Mapping Competitor Platforms: Analyzing patents helps identify core molecular scaffolds or biological platforms, enabling technologies that span multiple products, and cross-therapeutic applications of similar approaches that form a competitor’s underlying technology platform.

- Strategic Decision-Making: Patent intelligence enables the evaluation of the potential impact of competitor innovations on existing product lines, the assessment of freedom-to-operate constraints for pipeline products, the identification of patent challenges or invalidation opportunities, and the development of contingency plans for market entry by competitive products.36

By leveraging patent intelligence, companies can shift from a reactive stance—merely responding to competitor launches—to a proactive one, anticipating market shifts and competitive moves. This is the essence of competitive advantage, enabling strategic maneuvering before competitors even realize a threat exists.

Freedom-to-Operate (FTO) Analysis: Mitigating Infringement Risks

Freedom-to-Operate (FTO) analysis, also known as a “clearance search,” is a critical due diligence process undertaken to ensure that a new product, process, or service does not infringe on existing, active patents held by others.

The process involves a comprehensive search of patent databases for in-force patents that might be relevant to a company’s product or technology. This includes a meticulous analysis of patent claims, their legal status, and the geographic coverage of the patents. Given the extensive “patent thickets” that often surround many drugs, FTO analysis is particularly vital in the pharmaceutical industry to prevent costly legal disputes that can halt product launches and incur massive damages.78

Identifying potential infringement risks early in the development lifecycle allows companies to implement crucial risk mitigation strategies. These can include “designing around” existing patents by modifying the product or process, negotiating licensing agreements with patent holders, or proactively challenging problematic patents through legal avenues.24 A robust FTO analysis directly impacts a company’s ability to bring a product to market without legal encumbrances. Failure to conduct thorough FTO can lead to expensive litigation, injunctions that block market entry, and significant financial penalties.78

Market Entry Strategies: Seizing Generic Opportunities

For generic pharmaceutical manufacturers, timing is everything when it comes to market entry. Entering too early risks costly patent infringement litigation, while entering too late means missing the crucial “first-to-file” advantage.

- Leveraging Orange Book Data: Analyzing patent expiration dates and regulatory exclusivity periods listed in the FDA’s Orange Book is fundamental for identifying optimal market entry windows for generic or biosimilar products.13 DrugPatentWatch, with its constantly updated insights on patent expiration, is a key tool for this analysis.

- Paragraph IV Challenges: Generic companies can strategically challenge the validity or non-infringement of innovator patents via Paragraph IV certifications.39 If successful, the first generic applicant to file such a certification is eligible for 180 days of market exclusivity, preventing other generics from entering during that period and allowing them to capture a significant market share.4 This incentivizes early patent challenges and accelerates generic competition. The 180-day exclusivity granted to the first generic filer directly leads to a significant market share advantage (typically 70-80% within the first year) and higher initial prices for that first entrant.39 This creates a high-stakes “race” for generic companies.

- Predicting Generic Launches: Tracking litigation data, including “at-risk” launches (where a generic manufacturer begins selling its product before patent litigation concludes, taking a calculated risk), is crucial for predicting generic entry timelines. The first generic entrant typically prices its products 15-30% below the brand, and within 12 months, multiple generics usually enter, driving prices down 50-80%. Brand products often lose 80-90% of market share within one year of multiple generic entry.

The impending expiration of patents on blockbuster drugs, often referred to as the “patent cliff” 37, is not merely a loss for branded companies but a significant catalyst for market transformation. This phenomenon creates massive opportunities for generic manufacturers and fundamentally shifts the overall market landscape.13 Strategic responses by innovator companies facing generic entry include lowering their prices, launching authorized generics, or accelerating the development of next-generation products to mitigate anticipated revenue loss.37

Identifying White Space: Fueling Future Innovation

Beyond defensive strategies, patent intelligence is a powerful tool for identifying “white space”—therapeutic areas, technological approaches, or delivery mechanisms with limited or no existing patent coverage. These areas often indicate unmet needs or untapped market opportunities.

The methodology for identifying white space involves a comprehensive patent landscape analysis. This includes mapping all patents within a therapeutic area of interest, analyzing citation patterns to find highly influential early-stage technologies, and identifying shifts in technology trends. For example, a company might discover a mechanistically related target with minimal patent activity despite promising biology, or identify delivery approaches not yet claimed for specific indications.

The strategic value of identifying white space is immense. It allows companies to redirect R&D investments to more promising or less crowded areas, fostering genuine breakthrough innovation rather than incremental improvements. It can also reveal opportunities for novel applications of existing technologies or combination therapies with minimal competitive activity. The identification of these patent gaps directly influences R&D prioritization, leading companies to invest in truly novel areas rather than competing in crowded fields.

Navigating “Evergreening” Strategies: Challenges and Countermeasures

“Evergreening” is a controversial strategy employed by pharmaceutical companies to extend the lifetime of their patent monopolies. This is often achieved by obtaining numerous additional patents on minor variations of an original drug, such as new formulations, dosage forms, routes of administration, or new uses.7 The primary aim of evergreening is to prolong monopoly periods and delay generic drug entry, thereby maintaining high drug costs.

Common types of evergreening include:

- Product Hopping/Switching: This involves patenting minor variations like changes to the drug’s physical form (e.g., capsule to tablet), subtle chemical changes (e.g., chiral switches to different enantiomeric mixtures), or switching from short-acting to long-acting formulations.23

- New Formulations/Delivery Methods: Patenting extended-release versions or novel delivery systems for an existing drug.9

- New Methods of Use/Indications: Securing patents for novel therapeutic uses of an existing drug, even if the drug compound itself is old.2

- Patent Clustering/Thickets: Building a “comprehensive ‘web of protection'” by accumulating multiple patents around a single drug, making it difficult for generics to navigate the IP landscape without infringement.7

The impact of evergreening can be substantial. For instance, product hopping of the multiple sclerosis drug glatiramer acetate (Copaxone) resulted in an estimated cost to consumers of $4.3 to $6.5 billion over two and a half years. This illustrates that evergreening transforms what might seem like a niche legal strategy into a major public health and economic issue. It also undermines the fundamental “patent bargain” by extending monopolies beyond what might be considered genuine innovation.

While secondary patents can protect genuine follow-on innovation, evergreening highlights how the patent system can be “strategically manipulated” to prolong monopolies and delay generic entry.7 Distinguishing between these two motivations is “very difficult” , creating a significant point of controversy and policy debate.

For generic manufacturers, understanding these strategies is crucial for developing effective countermeasures:

- Paragraph IV Challenges: Directly challenging the validity or non-infringement of evergreening patents is a primary legal avenue.6

- “Skinny Labels”: Marketing a generic for only the non-patented uses of a drug, thereby “carving out” patented method-of-use indications, allows generics to avoid infringement.6

- Developing Novel Synthesis Routes: Generic companies can invest in R&D to devise manufacturing processes that avoid patented methods of synthesis.

- Litigation: Engaging in legal battles to invalidate or bypass these secondary patents is a common strategy to accelerate generic market entry.7

Table 7: Common Evergreening Strategies

| Strategy | Description | Example | Impact |

| Product Hopping/Switching 23 | Patenting minor variations (e.g., dosage form, chemical changes, release characteristics) of an existing drug. | Switching from short- to long-acting formulations; chiral switches (e.g., Copaxone, Namenda).23 | Extends market exclusivity, delays generic entry, can cost consumers billions. |

| New Formulations/Delivery Methods 9 | Patenting new ways a drug is prepared or administered. | Extended-release versions (e.g., Prozac, Glucophage XR) or novel delivery systems. | Prolongs patent protection, enhances patient compliance or efficacy. |

| New Methods of Use/Indications 2 | Securing patents for novel therapeutic uses of an existing drug. | Discovering a new disease indication for an already approved drug. | Expands market scope, creates new revenue streams, extends exclusivity for that specific use. |

| Patent Clustering/Thickets 7 | Accumulating numerous patents around a single drug to create a complex web of protection. | Multiple patents covering different aspects: compound, formulation, process, use, polymorphs. | Deters generic entry by increasing litigation risk and complexity for challengers. |

Table 8: Pharmaceutical Patent Litigation Statistics (US)

| Statistic | Value/Trend (2023) | Implication |

| % of patent infringement cases resulting in injunctions | 45% | Injunctions are a significant remedy for patent holders to stop ongoing infringement. |

| % of patent cases with preliminary injunctions granted | 30% | Courts view certain infringement scenarios with urgency, granting temporary halts early in litigation. |

| % of patent infringement cases with permanent injunctions issued | 20% | Permanent injunctions are less common but represent a definitive, long-term halt to infringing activities. |

| % of injunctions granted in favor of the plaintiff | 60% | Patent holders (plaintiffs) have a higher likelihood of securing injunctions to protect their IP. |

| Median duration for a preliminary injunction | 6 months | Provides a temporary but significant period to prevent further harm while the case proceeds. |

| Median duration for a permanent injunction | 18 months | Long-term impact on infringing parties, effectively stopping activities related to the patented invention. |

| % of all patent injunctions related to pharmaceutical patents | 15% | Highlights the heavy reliance on patent protection and litigation in the pharmaceutical industry. |

The Horizon of Innovation: Emerging Trends in Patent Intelligence

The landscape of patent intelligence is continuously evolving, driven by technological advancements that are revolutionizing how patent data is searched, analyzed, and leveraged.

The Rise of AI and Machine Learning in Patent Analysis

Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) are transforming patent analysis, moving beyond traditional manual processes to enable unprecedented speed, depth, and predictive capabilities.

- Automated Search and Analysis: AI algorithms can rapidly analyze vast amounts of patent documents, identifying relevant prior art, potential threats, and weaknesses in IP portfolios. They automate routine tasks such as preliminary searches, freeing up patent professionals to focus on more complex analyses that require human expertise and judgment. This ability to analyze scores of documents quickly and automate repetitive tasks directly leads to increased speed and depth in patent analysis, allowing for more comprehensive and timely competitive intelligence.