Section 1: The Global Patent Imperative: A High-Stakes Balancing Act

Introduction: Beyond a Legal Formality, a Core Business Asset

In the high-stakes world of pharmaceutical innovation, a patent is far more than a legal document; it is the foundational asset upon which entire companies are built, markets are won, and the future of medicine is financed. For business leaders and strategic decision-makers in the biopharma sector, viewing patent protection as a mere legal formality or a defensive shield is a critical miscalculation. Instead, it must be understood as the central pillar of corporate strategy—a dynamic, offensive tool that secures market exclusivity, justifies massive investment, and ultimately drives shareholder value. This report provides a comprehensive blueprint for navigating the complex, treacherous, and ever-evolving landscape of global pharmaceutical patent protection, designed to transform your intellectual property (IP) from a cost center into a formidable competitive advantage.

The entire pharmaceutical business model rests on a delicate and often contentious societal bargain: a temporary, government-granted monopoly in exchange for the monumental risk and expense of inventing and developing new life-saving medicines. The scale of this investment is staggering. Bringing a single new drug to market frequently requires upwards of $2 billion and can take 12 to 13 years from the initial discovery to final regulatory approval. This protracted timeline means that a significant portion of the standard 20-year patent term is consumed before a single dollar of revenue is generated, leaving an effective market exclusivity period of often just 7 to 8 years.2

It is within this compressed window that a company must recoup its entire research and development (R&D) expenditure and generate the profits necessary to fund the next wave of innovation. The numbers speak for themselves: drugs protected by robust patents generate 80-90% of their lifetime revenue during these few years of exclusivity. The moment that protection expires—an event known as the “patent cliff”—the consequences are immediate and severe, with revenue plummeting by as much as 90% following the entry of generic competition. Between 2025 and 2030 alone, an estimated $236 billion in global pharmaceutical revenue is projected to be lost as patents for blockbuster drugs expire.

This unforgiving economic reality places an immense premium on crafting a sophisticated, forward-thinking global patent strategy. It is a discipline that demands more than just legal acumen; it requires a deep understanding of international treaties, the unique political and legal nuances of key markets, advanced lifecycle management tactics, and the strategic use of patent data as a powerful intelligence weapon. From the harmonized systems of the United States and Europe to the challenging but crucial emerging markets of China, India, and Brazil, every decision—where to file, when to file, and how to defend—carries billion-dollar implications. This report will guide you through that decision-making process, providing the strategic framework needed to not only protect your innovations but to leverage them for global market dominance.

A Brief History: From “Patent Medicines” to Precision Medicine

To master the modern landscape of pharmaceutical IP, one must first understand its complicated and often controversial history. The very concept of a “patent medicine” is, for better or worse, tied to an era of entrepreneurial zeal that predates the modern, science-driven pharmaceutical industry. In the 19th century, the patent medicine industry was one of America’s fastest-growing sectors, but it did not rely on legal drug patents from the U.S. government for its active ingredients.

Instead, the term referred to proprietary concoctions, or “nostrums,” whose contents were typically trademarked but kept secret. These remedies were often made of common ingredients like alcohol and vegetable extracts, and some were fortified with morphine, opium, or cocaine.1 Sold with colorful names and even more colorful claims, these products were marketed as cures for nearly every ailment known to man, from colic in infants to cancer. This era, often referred to as one of “quackery,” was characterized by baseless claims and a complete lack of regulation, leading to tragic results for many unsuspecting consumers.1

This historical legacy of exploitation and fraudulent claims created a deep-seated public skepticism toward the industry’s profit motives that persists to this day. When modern pharmaceutical companies defend the high prices of their patented drugs by citing the immense costs of R&D, they are arguing against a powerful historical narrative of profiteering. This context is crucial. A company’s global patent strategy is not executed in a vacuum; it is deployed in a world that is inherently wary of the link between medicine and monopoly. Therefore, a successful IP strategy must be about more than just legal and economic justification; it must be supported by transparent communication and a clear articulation of the value the innovation brings to patients and society, thereby overcoming a century of ingrained public distrust.

The transition from this unregulated past to the highly structured present began in the early 20th century with the passage of legislation like the 1906 Pure Food and Drug Act, which was a direct response to the abuses of the patent medicine trade. The modern pharmaceutical industry, with its profound emphasis on scientific research, clinical trials, and regulatory oversight, is a world away from its 19th-century predecessor. Its reliance on patents is not a tool to protect secret formulas but a necessary mechanism to incentivize the enormous financial risk required to turn a scientific discovery into a safe and effective therapy.1 Understanding this evolution is the first step in building a patent strategy that is not only legally sound but also publicly defensible.

Section 2: Architecting Your Global Footprint: Core Filing Strategies and Frameworks

The Global IP Architecture: Understanding the Pillars

Protecting a pharmaceutical innovation across multiple countries is not a matter of securing a single “world patent.” Rather, it requires navigating a complex patchwork of international treaties and regional agreements that together form the global IP architecture. A patent is a national right, meaning protection must be sought and granted in each individual country where a company wishes to prevent others from making, using, or selling its invention. However, several key international frameworks exist to streamline this process, making a global filing strategy both feasible and manageable. For any pharmaceutical company with international ambitions, a deep, strategic understanding of these pillars is non-negotiable.

The TRIPS Agreement: The “Grand Bargain” and Its Flexibilities

The foundational treaty of the modern global IP system is the World Trade Organization’s (WTO) Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights, commonly known as TRIPS.7 Negotiated during the Uruguay Round of trade talks and effective since 1995, TRIPS introduced intellectual property rules into the multilateral trading system for the first time, creating a “grand bargain” between developed and developing nations. In essence, developing countries agreed to adopt higher standards of IP protection in exchange for better market access for their goods, such as clothing and agricultural products.8

For the pharmaceutical industry, the most critical provisions of TRIPS were those related to patents. The agreement mandates that all WTO member countries must provide patent protection for all technological inventions, including pharmaceuticals, for a minimum term of 20 years from the filing date.8 It also requires members to establish effective legal and administrative procedures to enforce these rights, making it possible for patent holders to seek redress if their rights are infringed.

However, the imposition of these standards created a fundamental and lasting tension. Historically, developed nations like the United States and those in Europe adopted strong patent protection only after reaching high levels of per capita income, typically upwards of $20,000. The TRIPS agreement, in contrast, required developing countries to adopt these same stringent standards at much lower income levels, often between $500 and $8,000 per capita. This premature imposition of a developed-world patent framework is perceived by many developing nations as prioritizing foreign commercial interests over their pressing public health needs. This perception is the direct root of the aggressive use of TRIPS “flexibilities”—provisions built into the agreement that allow countries to temper the full force of patent monopolies.

The most significant of these flexibilities include:

- Transitional Periods: TRIPS granted developing and least-developed countries extended timelines to phase in their obligations, particularly for pharmaceutical product patents.8 India, for example, used its 10-year transition period until 2005 to build its now-dominant generic drug industry.

- Compulsory Licensing: This is a powerful tool that allows a government to authorize a third party (such as a local generic manufacturer) to produce a patented product without the consent of the patent holder, typically in response to a public health crisis or if the drug is not being made available on reasonable terms.8 The patent holder is paid “adequate remuneration,” but the monopoly is effectively broken.

- The Doha Declaration: In 2001, amidst the global HIV/AIDS crisis, the WTO issued the Doha Declaration on TRIPS and Public Health. This landmark declaration affirmed the primacy of public health over private intellectual property rights, clarifying that countries have the right to use TRIPS flexibilities to their fullest extent to protect public health and promote access to medicines for all.7

A global patent strategy must therefore be risk-weighted, acknowledging that while TRIPS provides a baseline of protection, patents in developing jurisdictions are inherently more vulnerable to political and public health-driven challenges.

The Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT): Your Strategic Delaying Tactic

While TRIPS sets the rules of the game, the Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) provides the most common playbook for executing an international filing strategy. Administered by the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), the PCT is an international treaty with 158 contracting states that provides a unified and cost-effective procedure for seeking patent protection in multiple countries simultaneously.14

Filing a single “international application” under the PCT has the same legal effect as filing separate national patent applications in all of the designated member countries. This initial filing secures a priority date—a critical timestamp that establishes the novelty of the invention. The application then enters the “international phase,” which includes a formal examination and an “international search” conducted by an authorized International Searching Authority (ISA). The ISA produces a search report and a written opinion on the invention’s potential patentability, giving the applicant an early, non-binding assessment of their chances of success.

However, the true strategic genius of the PCT system lies in what it allows a company not to do. The international phase typically lasts for 30 months (or 31 in some jurisdictions) from the earliest priority date. Only at the end of this period must the applicant decide in which specific countries they wish to proceed by entering the “national phase.” This is the point at which the significant costs of national filing fees, translation fees, and local patent attorney fees are incurred.

This 30-month delay transforms the PCT from a mere legal convenience into a powerful financial management and strategic planning tool, particularly for capital-constrained startups and biotech firms. Filing patents in just 10 different countries can easily cost over $250,000 over the life of the patents, with a substantial portion of that cost due upfront. The PCT allows a company to defer these major expenditures while critical events unfold. In that two-and-a-half-year window, a company can:

- Obtain crucial Phase II clinical trial data to better assess the drug’s efficacy and commercial potential.

- Secure the next round of venture capital funding or a strategic partnership.

- Conduct further market research to refine its list of target countries.

- Monitor the competitive landscape for new threats.

By aligning the major patent cost outlays with key value inflection points in the R&D cycle, the PCT de-risks the entire IP process. It turns what would be a high-risk, upfront capital expenditure into a staged investment, allowing a company to make more informed decisions about where to allocate its precious resources.

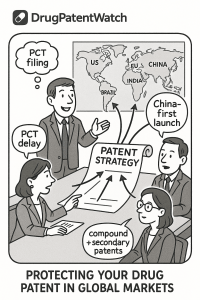

Crafting Your International Filing Strategy: Where, When, and How

With an understanding of the global architecture, the next step is to build a filing strategy tailored to your specific product, budget, and business goals. The default advice to “file everywhere your product is made, used, or sold” is both financially impractical and strategically naive. A smarter approach involves a disciplined analysis of several key factors.

First, validate the business need for each jurisdiction. Is this a market where you realistically expect to generate significant revenue? A patent in a country with negligible market potential is a wasted investment. For business models dependent on per capita income, affluent markets like the United States, Europe, and Japan are obvious priorities. For models driven by population volume, major emerging markets like China and India become essential.

Second, analyze the competitive landscape. One of the most effective ways to develop a foreign filing strategy is to conduct a worldwide patent search on the key foreign patents of your main competitors. This reveals where your rivals see value and helps establish a baseline of essential countries for your industry and therapeutic area. Platforms like DrugPatentWatch are invaluable for this kind of competitive intelligence, offering deep insights into competitor patent portfolios, litigation histories, and filing patterns.17

Third, assess the legal and enforcement environment. A patent is worthless if it cannot be enforced. A better strategy is to prioritize countries where the legal system is fair and predictable in enforcing the patent rights of foreign companies. This involves evaluating the strength of the judiciary, the availability of remedies like injunctions, and the political stability of the region.

A practical framework for synthesizing these factors is the “two-thirds market filing strategy”. This approach advocates for filing in a limited number of jurisdictions that collectively cover the most lucrative percentage—for example, two-thirds—of your potential global market. If analysis shows that the U.S., China, Europe, and Japan will account for the majority of worldwide revenue for your product, then focusing your patent budget on securing robust protection in these key jurisdictions provides the greatest return on investment. This concentrated approach not only protects your primary revenue streams but can also create a significant competitive advantage. By establishing an exclusive geography in the key two-thirds of the market, you can deter competitors from even entering the unprotected one-third, as they may lack the economies of scale to compete effectively.

The following table provides a high-level comparison of the two primary routes for international filing:

Table 2: Strategic Pros and Cons: PCT Route vs. Direct National Filing

| Feature | Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) Route | Direct National/Regional Filing (Paris Convention) |

| Process | File one “international” application, which secures a filing date in all 158 member states. Enter national/regional phase up to 30/31 months later. | File separate applications directly with each national or regional patent office within 12 months of the first (priority) filing. |

| Upfront Cost | Lower. A single set of fees is paid for the international phase. Major costs (national fees, translations) are deferred for 30 months. | Higher. Multiple sets of filing fees, translation costs, and attorney fees are due within the first 12 months. |

| Strategic Flexibility | High. The 30-month delay provides valuable time to assess clinical data, market potential, and funding before committing to expensive national filings. | Low. The decision on which countries to file in must be made within 12 months, often before key R&D milestones are reached. |

| Early Feedback | Provides a preliminary, non-binding opinion on patentability (International Search Report and Written Opinion) during the international phase. | No centralized preliminary feedback. Assessment of patentability occurs separately in each national office during examination. |

| Speed to Grant | Slower overall time to grant, as the 30-month international phase precedes national examination. | Potentially faster time to grant in individual countries, as national examination can begin immediately after the 12-month priority period. |

| Best For | Startups, biotechs, and companies with uncertain drug candidates or budgets. Ideal for preserving options and aligning IP costs with R&D milestones. | Companies with high certainty in a drug’s potential and a clear, limited set of target markets. Useful for expediting grant in a few key jurisdictions. |

Section 3: Navigating the Major Blocs: The U.S. and European Patent Landscapes

While the PCT provides a global entry point, the real work of securing and enforcing a patent happens at the national and regional levels. The United States and Europe represent the two largest and most sophisticated pharmaceutical markets in the world. Mastering their distinct patent systems is fundamental to any successful global IP strategy.

The United States: The World’s Largest Pharmaceutical Market

The United States patent system, administered by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO), is the gold standard for many pharmaceutical innovators. It offers robust protection and a well-developed legal framework for enforcement. A key feature for early-stage companies is the provisional patent application. This is a lower-cost, less formal filing that allows a company to secure an early priority date without the need for formal patent claims. This gives the applicant a 12-month window to file a full, non-provisional application, providing a cost-effective way to establish a foothold while further developing the invention.

The U.S. landscape is heavily shaped by the Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984, better known as the Hatch-Waxman Act. This landmark legislation created the modern framework for balancing the interests of innovator (branded) drug companies and generic manufacturers. It established the Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) pathway, allowing generics to gain FDA approval by demonstrating bioequivalence without having to repeat costly clinical trials. In exchange, it created a system of patent term extensions (PTEs) to restore some of the patent life lost during the lengthy FDA review process, a crucial mechanism we will explore in detail in Section 5.

The European Union: A Unified but Complex System

Navigating the European patent landscape has historically been a more fragmented affair. However, recent developments are creating a more unified and streamlined, albeit complex, system.

The European Patent Office (EPO) Process: From Filing to Grant

The primary route for obtaining patent protection across Europe is through the European Patent Office (EPO). An applicant files a single European patent application in one of the three official languages (English, French, or German), designating the member states of the European Patent Convention in which they seek protection.21

The process mirrors that of other major patent offices and includes several key stages :

- Drafting and Filing: The application must contain a request for grant, a detailed description of the invention, one or more claims defining the scope of protection sought, any necessary drawings, and an abstract.

- Formal Examination and Search: The EPO conducts a formal examination to ensure the application meets all requirements and performs a comprehensive “European search” to identify relevant prior art. The resulting search report gives the applicant a clear idea of the patentability hurdles they face.

- Substantive Examination: An EPO examiner then assesses whether the invention meets the core requirements of patentability: novelty, inventive step, and industrial applicability. This often involves a back-and-forth dialogue between the examiner and the applicant’s attorney, where claims may be amended to overcome objections.

- Grant: If the examiner is satisfied, the patent is granted. At this point, the single European patent transforms into a “bundle” of individual national patents. To complete the process, the patent holder must validate the patent in each designated country. This typically involves filing translations of the claims (or the full patent in some cases) with the national patent offices and paying the required fees.

The Unitary Patent and Unified Patent Court (UPC): A New Era for European Litigation

The most significant change to the European patent landscape in a generation arrived on June 1, 2023, with the launch of the Unitary Patent and the Unified Patent Court (UPC). This new system, which currently covers 17 EU member states (with more expected to join, like Romania in September 2024), offers a revolutionary alternative to the traditional “bundle” of national patents.23

- The Unitary Patent (UP): Upon grant of a European patent, the patent holder can now request “unitary effect.” This creates a single, unified patent that provides uniform protection across all participating UPC member states. This eliminates the need for costly and burdensome national validation procedures in each of those countries.

- The Unified Patent Court (UPC): This is a new, specialized court with exclusive jurisdiction over disputes involving Unitary Patents and, eventually, all European patents (unless they have been “opted out” during a transitional period). The UPC has local and regional divisions across Europe, as well as a central division and a Court of Appeal.24

The strategic implications of this new system are profound. The UPC creates a “high-risk, high-reward” environment that fundamentally alters the calculus of European patent strategy. On one hand, it offers the unprecedented power and efficiency of obtaining a single injunction that can halt infringement across 17 countries simultaneously—a massive win for patent holders. On the other hand, it introduces the existential threat of a single, centralized revocation action. A competitor can now challenge a patent in the UPC, and if successful, that patent will be nullified across all participating countries in one fell swoop.

Before the UPC, invalidating a European patent required launching separate, costly, and often unpredictable legal actions in the national courts of each country. The risk was fragmented. The UPC centralizes this risk. For a pharmaceutical product protected by only one or two core patents—such as a primary compound patent—this represents a single point of failure that could be catastrophic.

This new dynamic compels a strategic shift. To mitigate the risk of a single, devastating revocation, companies are now more incentivized to build more resilient, multi-layered patent portfolios. The strategic response is to create redundancy by filing more secondary patents—on new formulations, dosage regimens, methods of manufacturing, and second medical uses—and bringing them under the UPC’s jurisdiction. This creates a defensive “patent thicket.” Even if a challenger successfully invalidates the primary compound patent in a central revocation action, other patents in the thicket may survive, preserving a degree of market exclusivity and turning a potential patent cliff into a more manageable slope. In this way, the very structure of the UPC system inadvertently makes the controversial strategy of building patent thickets a more necessary and rational defensive maneuver in Europe.

Section 4: The New Frontier: Mastering Patent Protection in Emerging Markets

For decades, the global pharmaceutical industry’s focus was squarely on the “triad” markets of the United States, Europe, and Japan. Emerging markets were often an afterthought, viewed as high-risk, low-reward territories plagued by weak IP protection and political instability. That paradigm has shattered. Today, countries like China, India, and Brazil are not just optional markets; they are indispensable engines of global growth. China’s pharmaceutical market, for instance, now contributes over 20% to the global industry.

However, navigating the patent landscapes of these nations presents a unique and formidable set of challenges. Their IP systems have been shaped by different historical trajectories, economic priorities, and public health concerns. They are characterized by variable patent laws, a greater willingness to use tools like compulsory licensing, and often inconsistent enforcement mechanisms.11 Success in these markets requires a bespoke strategy, grounded in a deep understanding of local laws, legal precedents, and political realities.

The Shifting Landscape: From High Risk to High Priority

The journey to TRIPS compliance has been uneven across the developing world. While the agreement established a minimum floor for IP protection, many countries have implemented its provisions in ways that reflect their own national interests. This has resulted in a patchwork of legal standards that can catch unwary foreign companies by surprise. Common challenges include:

- Variability in Patentable Subject Matter: What is considered a patentable invention in the U.S. or Europe may not be in India or Brazil. Certain jurisdictions, for example, have stricter rules against patenting new uses of known substances or minor modifications to existing drugs.13

- The Specter of Compulsory Licensing: As discussed, this TRIPS flexibility remains a powerful tool for governments to break patent monopolies on essential medicines, creating significant uncertainty for patent holders.8

- Weak or Inconsistent Enforcement: Even when a patent is granted, enforcing it can be difficult. Weak judicial systems, corruption, local protectionism, and a lack of specialized IP courts can make obtaining injunctions or damages a long and frustrating process.13

Despite these risks, the sheer size and growth potential of these markets make them impossible to ignore. The key is not to avoid them, but to engage with them intelligently, with a strategy that is tailored to their specific legal and commercial environments.

Case Study: China’s Transformation into an IP Powerhouse

Nowhere is the transformation of the global IP landscape more evident than in China. Once considered a haven for IP infringement, China has undertaken a radical overhaul of its patent system, turning it into a critical battleground for global pharmaceutical companies. With over 1.5 million patent applications filed in 2022, China is now the world’s leader in patent filings.

More importantly, its enforcement regime has become surprisingly robust and efficient. China’s specialized IP courts are resolving approximately 70% of infringement cases within 12 months, a stark contrast to the multi-year sagas common in the U.S.. Furthermore, these courts have become increasingly favorable to patent holders, including foreign ones. In 2022, foreign plaintiffs achieved an impressive 77% success rate in patent infringement cases against Chinese defendants. Damage awards are also rising, reflecting a growing recognition of the value of intellectual property.

This legal evolution is part of a deliberate, top-down industrial policy designed to attract cutting-edge R&D and position China as a global leader in biopharmaceutical innovation. Two recent reforms are central to this strategy:

- The Patent Term Compensation System: Effective June 1, 2021, China introduced a system similar to PTE in the U.S. and SPCs in Europe. It allows for a patent term extension of up to five years to compensate for delays in the regulatory approval process, with the total effective patent term capped at 14 years post-approval.29 However, there is a crucial catch: to be eligible, the drug must have received its first marketing approval anywhere in the world

in China. This “China-first” requirement is a game-changer. Historically, multinational companies launched new drugs first in the U.S. or Europe, with China following years later. This new system creates a powerful incentive to reverse that sequence. The prospect of an additional five years of monopoly in the world’s second-largest pharmaceutical market forces companies to completely re-evaluate their global launch strategies, potentially shifting the entire center of gravity for new drug commercialization eastward. - The Patent Linkage System: Also introduced in 2021, this system creates a mechanism similar to that in the U.S. for resolving patent disputes before a generic drug enters the market. When a generic manufacturer files for approval and challenges an existing patent, the patent holder has 45 days to file a lawsuit. This triggers an automatic 9-month stay on the generic’s approval, giving the courts time to adjudicate the patent dispute.18 This provides innovator companies with a clear and timely pathway to defend their patents and prevent infringing products from reaching the market.

China’s IP system is no longer a liability to be managed but a strategic tool to be leveraged. By understanding and adapting to these new rules, companies can secure significant competitive advantages in this vital market.

Case Study: India, “The Pharmacy of the World”

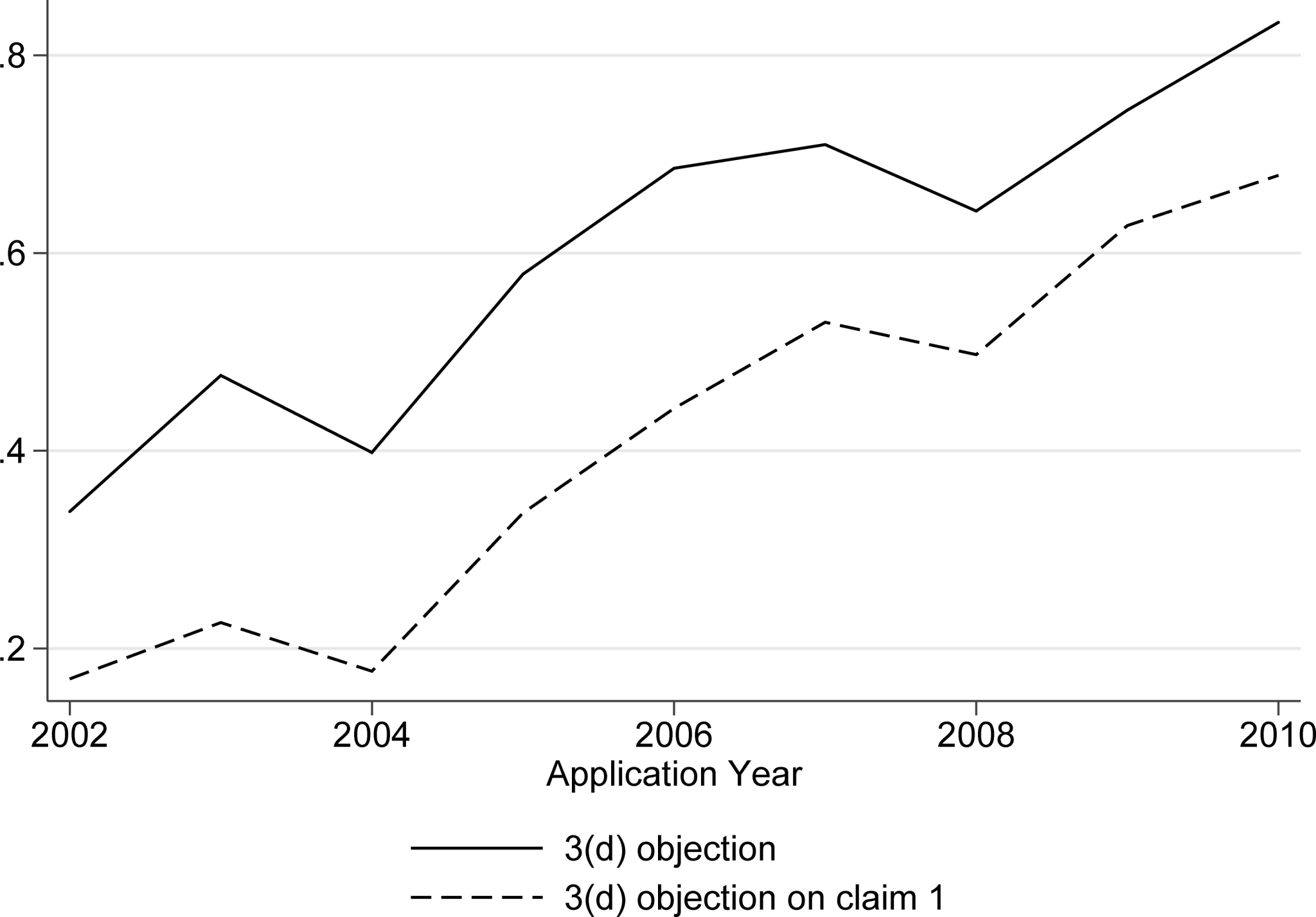

India’s patent system is arguably the most unique and challenging among the major global markets. Its laws have been profoundly shaped by its post-colonial history and its rise as the “pharmacy of the world”—a dominant global supplier of low-cost generic medicines.32 While India amended its patent laws to become TRIPS-compliant in 2005, it did so while building in powerful safeguards to protect public health and its domestic generic industry. Two provisions are particularly critical for foreign pharmaceutical companies to understand.

- Section 3(d) of the Patents Act: This is the cornerstone of India’s approach to pharmaceutical patents and its primary weapon against “evergreening”—the practice of obtaining new patents for minor modifications of existing drugs to extend a monopoly. Section 3(d) explicitly states that a new form of a known substance (such as a salt, ester, or polymorph) is not considered a new invention unless it demonstrates a “significant enhancement of the known efficacy” of that substance.28

This provision was famously tested in the landmark 2013 Supreme Court of India case, Novartis v. Union of India. Novartis sought a patent for a new crystalline form of its cancer drug Gleevec (imatinib mesylate), arguing it had improved bioavailability. The court rejected the patent, ruling that improved bioavailability did not necessarily translate to enhanced therapeutic efficacy and that Novartis had not provided the clinical data to prove it.

The implications of Section 3(d) are profound. It forces a fundamental integration of a company’s legal and clinical development strategies. To obtain a secondary patent in India, it is not enough to show that a new formulation is novel and non-obvious from a chemical perspective. The company must proactively design and conduct clinical or preclinical studies to generate hard data that explicitly proves superior efficacy. The legal requirement dictates the scientific strategy, meaning the IP and clinical teams must collaborate from the very beginning of any lifecycle management project intended for the Indian market.

- Compulsory Licensing: India’s patent law contains broad provisions for compulsory licensing, which can be granted three years after a patent is issued if it is determined that the reasonable requirements of the public have not been met, the drug is not available at a reasonably affordable price, or the patent is not “worked” in the territory of India.28

In 2012, India issued its first and only compulsory license for a pharmaceutical product in the case of Natco Pharma v. Bayer Corporation. The license was granted to the Indian generic company Natco to produce a version of Bayer’s patented cancer drug Nexavar (sorafenib tosylate). The Controller General of Patents found that Bayer was supplying the drug to only a tiny fraction of the patient population and at a price that was prohibitively expensive for most Indians.35 While the threat of compulsory licensing is ever-present, it is important to note that it is used as a measure of last resort. The Indian courts have placed a heavy burden of proof on the applicant to demonstrate that the conditions have been met and that they have first made reasonable efforts to obtain a voluntary license from the patent holder.

Case Study: Brazil and the “Patent Paradox”

Brazil, the largest pharmaceutical market in Latin America, presents its own set of unique challenges. The country has a long history of using public health concerns to shape its IP policy. Like India, Brazil has famously used the threat of compulsory licensing as a tool to negotiate significant price reductions from multinational pharmaceutical companies, particularly for HIV/AIDS drugs in the early 2000s.38

However, one of the most significant contemporary challenges in Brazil is what has been termed the “patent paradox”. This refers to a situation where, despite a relatively low number of pharmaceutical patents being granted, innovator companies are often able to maintain a “de facto monopoly” for extended periods. This occurs due to extremely long delays in the examination of patent applications by the Brazilian patent office (BRPTO).

A patent application that is pending examination creates significant legal uncertainty for potential generic competitors. If they launch a product and the patent is later granted, they could be liable for substantial damages for infringement. This risk is often enough to deter generic entry, allowing the innovator company to remain the sole supplier and charge monopoly prices, even without a granted patent. This situation is aggravated by originator companies filing numerous secondary patent applications, or “evergreening,” which further clogs the examination pipeline and prolongs the period of legal uncertainty. For companies seeking to enforce their rights, the Brazilian judicial system can be effective, but litigation, particularly the damages quantification phase, can be a lengthy and separate proceeding.

The following table summarizes the key features and strategic considerations for these critical markets compared to the U.S. and EU.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Key Global Patent Jurisdictions

| Feature | United States | European Union (UPC) | China | India |

| Key IP Body | USPTO | EPO / UPC | CNIPA | IPO |

| Patent Term | 20 years from filing | 20 years from filing | 20 years from filing | 20 years from filing |

| Term Extension | Patent Term Extension (PTE) – up to 5 years | Supplementary Protection Certificate (SPC) – up to 5 years (+6 mo. pediatric) | Patent Term Compensation – up to 5 years (requires China-first approval) | No provision for patent term extension |

| Key Doctrines | Hatch-Waxman Act, Provisional Applications | Unitary Patent, Unified Patent Court (UPC) | Patent Linkage System, “China-First” Policy | Section 3(d) (Efficacy Standard), Compulsory Licensing |

| “Evergreening” | Permissive, often challenged via litigation | Permissive, subject to inventive step analysis | Increasingly scrutinized but still common | Strictly prohibited by Section 3(d) unless enhanced efficacy is proven |

| Enforcement | Robust but slow and expensive litigation | Potentially fast and pan-European via UPC; high risk of central revocation | Increasingly robust, fast, and favorable to patent holders | Moderate; judiciary balances IP rights with public health concerns |

| Strategic Focus | Building patent thickets, navigating ANDA litigation | Deciding on UP/UPC opt-in, managing central revocation risk | Aligning launch strategy with term compensation rules, using linkage system | Generating clinical data to support efficacy for secondary patents, managing compulsory license risk |

Section 5: Extending the Horizon: Maximizing Your Patent’s Lifespan and Value

For a pharmaceutical company, the expiration date of a primary compound patent is not an endpoint; it is a critical strategic challenge to be managed. Given that the effective market exclusivity period is already severely truncated by long development and regulatory timelines, every additional day of protection is immensely valuable. Innovator companies have developed a sophisticated toolkit of legal and commercial strategies designed to maximize a drug’s patented life and create a more gradual, manageable decline in revenue, rather than a catastrophic fall off the patent cliff.

Compensating for Lost Time: Patent Term Extensions and SPCs

The most direct and widely accepted method for extending a drug’s monopoly period is through statutory mechanisms that compensate for regulatory delays. These systems acknowledge the unique burden placed on the pharmaceutical industry, where a patent can be granted years before the product is legally allowed to be sold.

Patent Term Extension (PTE) in the United States

As part of the Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984, the U.S. Congress created the Patent Term Extension (PTE) system. This provision allows the owner of a patent claiming a new drug product to apply to have the patent term restored to compensate for time lost during the FDA’s premarket regulatory review period.20

To be eligible for a PTE, a patent must meet several strict criteria :

- The patent must not have expired.

- The patent’s term must not have been previously extended.

- The product must have been subjected to a regulatory review period before its commercial marketing.

- The approval must be the first permitted commercial marketing or use of the product’s active ingredient.

The calculation for the length of the extension is complex, but it generally restores a portion of the time spent in clinical trials and the full time the drug was under review at the FDA. However, the extension is subject to two important caps: the maximum extension granted cannot exceed five years, and the total remaining patent term after the extension cannot be more than 14 years from the date of the drug’s regulatory approval. A timely application must be filed with the USPTO within 60 days of the FDA approval date.20

Supplementary Protection Certificates (SPCs) in Europe

The European Union has a similar system that provides for Supplementary Protection Certificates (SPCs). An SPC is not a direct extension of the patent itself but is a sui generis (unique) IP right that comes into effect the day after the basic patent expires.42 Like a PTE, an SPC is designed to compensate the patent holder for the long time required to obtain a marketing authorization for a new medicinal product.

The key features of the SPC system include 42:

- Eligibility: To obtain an SPC, the product must be protected by a basic patent in force, have a valid marketing authorization in the country where the SPC is sought, and it must be the first authorization to place that product on the market as a medicinal product.

- Duration: An SPC can extend the period of exclusivity for a maximum of five years. The total combined period of protection from the patent and the SPC cannot exceed 15 years from the date of the first marketing authorization in the European Economic Area (EEA).

- Pediatric Extension: A further six-month extension to the SPC can be granted if the company has conducted studies on the drug’s use in children in accordance with an agreed-upon Paediatric Investigation Plan (PIP). This incentive has been successful in increasing the number of medicines tested and approved for pediatric use.43

- Manufacturing Waiver: A significant recent development is the “SPC manufacturing waiver.” This provision allows EU-based generic and biosimilar manufacturers to produce a version of an SPC-protected medicine during the certificate’s term, but only for the purpose of exporting it to markets outside the EEA where protection does not exist or has expired.43 This was introduced to prevent European manufacturers from being at a competitive disadvantage compared to their counterparts in countries without SPC-like protection.

The following table highlights the key differences between the U.S. and European systems.

Table 3: Overview of Patent Term Extension Mechanisms (PTE vs. SPC)

| Feature | U.S. Patent Term Extension (PTE) | European Supplementary Protection Certificate (SPC) |

| Legal Nature | A direct extension of the term of the existing patent. | A separate, sui generis IP right that takes effect after the patent expires. |

| Maximum Duration | 5 years. | 5 years. |

| Overall Cap | Total remaining patent term cannot exceed 14 years from the date of FDA approval. | Total patent + SPC protection cannot exceed 15 years from the date of first EEA marketing authorization. |

| Pediatric Incentive | No direct equivalent tied to the PTE mechanism. | 6-month extension to the SPC is available for completing a Paediatric Investigation Plan (PIP). |

| Geographic Scope | Applies only within the United States. | Must be applied for and granted on a country-by-country basis within the EU/EEA. |

| Manufacturing Waiver | No equivalent provision. | Allows EU-based manufacturers to produce for export to non-EEA markets during the SPC term. |

Building the Fortress: The Strategy of Patent Thickets

Beyond statutory extensions, the most powerful—and controversial—strategy for prolonging a drug’s commercial life is the creation of a “patent thicket.” This involves proactively building an impenetrable fortress of intellectual property around a single blockbuster drug by securing numerous, often overlapping, patents on every conceivable aspect of the product.2

The Anatomy of a Patent Thicket

A robust patent thicket goes far beyond the single primary patent covering the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API). It is a dense and formidable web of secondary patents that can include 19:

- New Formulations: Such as extended-release versions that offer more convenient dosing.

- New Delivery Methods: Patents on new devices or methods for administering the drug, like an auto-injector pen or an intranasal spray.

- New Methods of Use: Securing patents for novel therapeutic uses or indications for an existing drug.

- Polymorphs: Patents on different crystalline structures of the API that may offer advantages in stability or manufacturing.

- Manufacturing Processes: Patents covering novel and more efficient methods of producing the drug.

- Combination Therapies: Patents on the use of the drug in combination with other active ingredients.

This strategy, often criticized by opponents as “evergreening,” is designed to make it extraordinarily difficult, risky, and expensive for a generic or biosimilar competitor to enter the market, even long after the primary compound patent has expired.3 The generic company must navigate this dense legal minefield, potentially facing dozens of infringement lawsuits on multiple fronts.

From a corporate finance perspective, building a patent thicket is an entirely rational strategy designed to mitigate the catastrophic financial impact of the patent cliff. A single patent has a single, predictable expiration date, creating a sudden and dramatic revenue drop. A patent thicket, however, consists of dozens or even hundreds of patents with different expiration dates and varying scopes of protection. This complexity makes it economically unfeasible for a competitor to challenge and invalidate every single patent. This creates a staggered and less certain timeline for generic entry, effectively transforming the sharp “cliff” into a more gradual and manageable “slope.” This provides greater revenue predictability for the innovator company, which is highly valued by investors and allows for more stable long-term financial planning and continued investment in R&D.

Case Study: AbbVie’s Humira and the Art of Monopoly Extension

The quintessential example of a successful patent thicket strategy is AbbVie’s handling of its blockbuster drug, Humira (adalimumab). Launched in the U.S. in 2002, Humira’s primary patent was set to expire in 2016. However, through a relentless and brilliantly executed IP strategy, AbbVie managed to delay the entry of biosimilar competitors in the lucrative U.S. market until 2023.49

AbbVie’s strategy involved filing a staggering 247 patent applications related to Humira, creating a thicket so dense that it was virtually impenetrable.46 These patents covered everything from specific manufacturing processes to new formulations and methods of treating different autoimmune conditions. Faced with the daunting prospect of fighting dozens of lawsuits, potential biosimilar entrants one by one chose to settle with AbbVie, agreeing to delay their U.S. launch dates in exchange for royalty-free licenses in Europe and other markets. This strategy extended Humira’s U.S. monopoly for an additional seven years, generating tens of billions of dollars in additional revenue for AbbVie and serving as a masterclass in the strategic weaponization of patent law.

Section 6: Defending the Fortress: Global Enforcement and Anti-Infringement Strategies

Securing a global portfolio of patents is only half the battle. A patent is ultimately a right to exclude others, and that right is only as valuable as its owner’s ability and willingness to enforce it. The global enforcement landscape is a complex battlefield, fraught with differing legal standards, sophisticated threats, and immense costs. A proactive, well-funded, and strategically coordinated enforcement plan is essential to defending the fortress of intellectual property that a company has so painstakingly built.

The Global Battlefield: Enforcing Your Rights Across Borders

Enforcing a patent against an infringer across multiple jurisdictions is a complex and resource-intensive undertaking. Because patent rights are national, an infringement action must typically be brought in each country where the infringement is occurring.9 This presents several significant challenges:

- Differing Legal Standards: The rules of evidence, the standards for proving infringement, and the availability of remedies can vary dramatically from one country to another. For example, the process for obtaining discovery (the pre-trial exchange of evidence) is far more extensive in the U.S. than in most European countries.

- High Costs: Multi-jurisdictional litigation is extraordinarily expensive, involving fees for local legal teams, court costs, and expert witnesses in each country. A single high-stakes pharmaceutical patent case in the U.S. can cost millions of dollars to litigate through trial and appeal.

- Risk of Conflicting Rulings: It is entirely possible for a patent to be found valid and infringed in one country, but invalid in another, leading to a fragmented and uncertain market landscape.

The global battle over Bayer’s blockbuster anticoagulant Xarelto (rivaroxaban) provides a vivid example of these challenges. Bayer has been engaged in a fierce, cross-border war to defend its patents against numerous generic manufacturers in dozens of jurisdictions. The results have been mixed: Bayer has secured preliminary injunctions in Germany, but its key patent has been found invalid in the UK, Australia, and South Africa, highlighting the unpredictability of global patent litigation.

The advent of the Unified Patent Court (UPC) in Europe is set to dramatically reshape this landscape. As discussed, the UPC offers the ability to obtain a single injunction with effect across 17 member states, vastly increasing the efficiency of enforcement for patent holders. However, this efficiency comes with the commensurate risk of a single central revocation. Early data from the UPC shows a finely balanced success rate, with patentees prevailing in about 50% of decisions on the merits. In the U.S., statistics from 2023 show that pharmaceutical patents accounted for 18% of all patent litigation cases, with plaintiffs achieving a 40% success rate in obtaining preliminary injunctions.53

The Counterfeit Drug Epidemic: An Existential Threat

One of the most insidious threats to both patent holders and public health is the global trade in counterfeit pharmaceuticals. This is not merely a matter of patent infringement; it is a large-scale criminal enterprise that puts millions of lives at risk.55

The scale of the problem is breathtaking. Analysts estimate the global counterfeit drug market to be worth between $200 billion and $432 billion annually, making it one of the most lucrative illicit trades in the world. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that at least 1 in 10 medical products circulating in low- and middle-income countries are substandard or falsified. The human cost is devastating. These fake drugs may contain no active ingredient, the wrong active ingredient, or toxic substances. In Africa alone, the proliferation of counterfeit antimalarial drugs is estimated to cause more than 120,000 deaths each year.

There is a direct and crucial link between weak patent enforcement and the rise of counterfeiting. A legal and regulatory environment where IP rights are not consistently protected creates a fertile ground for all forms of illicit activity. Counterfeiters are rational economic actors, drawn to markets with high potential profits and low perceived risks. When an innovator company demonstrates a strong and consistent willingness to enforce its patents against generic infringers, it sends a powerful signal to the entire market that it will aggressively defend its IP. This litigious posture raises the perceived risk for criminal organizations, who may view the market as less attractive because the legitimate patent holder has already established legal precedent and a network of legal and investigative resources on the ground. Therefore, a company’s patent litigation strategy is not just about stopping a single generic competitor; it is a critical, yet often overlooked, component of its broader brand protection and anti-counterfeiting efforts, helping to secure the integrity of the supply chain and protect patients.

Global efforts to combat this scourge are underway, led by organizations like the WHO, which operates a Global Surveillance and Monitoring System to track and report incidents of falsified medical products.56 These efforts rely on a combination of strengthening regulatory policies, enhancing quality control, and fostering public-private partnerships to dismantle these criminal networks.

Parallel Importation: The Arbitrage Dilemma

A legally distinct but related challenge is that of parallel importation. This is the practice of buying a patented drug in a country where the manufacturer sells it at a low price and then importing it for resale into a country where the price is much higher, undercutting the manufacturer’s authorized distributor.60 This is a form of arbitrage, exploiting the differential pricing strategies that pharmaceutical companies use across the globe.

The debate over parallel importation is fierce.

- Proponents argue that it is a legitimate tool to increase competition and lower drug prices for consumers, providing access to more affordable medicines. They contend that once a patent holder has sold a product, their rights should be “exhausted,” and they should not be able to control its subsequent resale.

- Opponents, primarily innovator pharmaceutical companies, argue that parallel trade undermines the very foundation of their business model. They claim it erodes the profits necessary to fund future R&D, as it prevents them from charging higher prices in wealthy markets to subsidize lower prices in poorer ones. They also raise serious concerns about supply chain integrity, arguing that parallel trade creates opportunities for counterfeit or improperly handled drugs to enter the legitimate supply chain.

The legal status of parallel importation varies significantly by jurisdiction. The European Union generally permits parallel trade between its member states under the principle of a single market. In contrast, the United States has taken a much stricter stance. In the landmark Jazz Photo decision, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit confirmed that the “exhaustion” doctrine does not apply to sales that occur in foreign countries. This gives U.S. patent holders a powerful tool to block the unauthorized parallel importation of their drugs into the U.S. market.

Section 7: From Data to Dominance: Leveraging Patent Intelligence for Competitive Advantage

In the 21st-century pharmaceutical industry, the most successful companies are not just those with the best scientists, but also those with the best intelligence. A proactive, data-driven approach to intellectual property is no longer a luxury; it is a prerequisite for survival. The vast global repositories of patent documents are not just legal archives; they are a rich, underutilized source of competitive intelligence that can provide unprecedented insights into competitor strategies, technological trends, and emerging market opportunities.

The Patent Filing as an Intelligence Document

A patent application is a strategic declaration of intent. Because most applications become public 18 months after their initial filing, they provide a valuable early warning system, offering a window into a competitor’s R&D pipeline years before a product enters clinical trials or is announced publicly. Systematically monitoring and analyzing these documents can transform a company’s strategic decision-making process.

“Companies that use patent data for trend forecasting are 2.3 times more likely to be market leaders in their respective fields.”

— McKinsey & Company report

By tracking competitor patent filings, a company can:

- Forecast Competitor Product Launches: Identify new products in development, predict their therapeutic targets, and anticipate their potential features and timelines.

- Inform R&D Decisions: Detect crowded therapeutic areas where competitors have established dense patent thickets, allowing a company to pivot its own resources toward less contested or more promising “white space” opportunities.

- Mitigate Risk: Assess freedom-to-operate for its own pipeline products, identify potential infringement risks early, and develop contingency plans for the market entry of a rival product.

- Identify M&A and Licensing Opportunities: Discover smaller biotech companies or academic institutions with strong, foundational patents in a key area of interest, flagging them as potential acquisition or in-licensing targets.

A Practical Guide to Patent Monitoring and Analysis

Extracting actionable intelligence from the torrent of global patent data requires a systematic and technologically enabled approach. An effective monitoring system involves several key steps :

- Define Objectives: Clearly articulate what information you need. Are you tracking a specific competitor’s activity in oncology? Monitoring all new filings related to a particular biological pathway? Identifying emerging technologies in drug delivery?

- Establish Parameters: Create sophisticated search strategies that incorporate relevant keywords, international patent classification (IPC) or cooperative patent classification (CPC) codes, specific company names, and key inventor names.

- Implement Alert Systems: Use automated tools to provide real-time or weekly notifications whenever a new patent document matching your criteria is published.

- Analyze and Disseminate: The raw data must be analyzed to extract strategic insights. This goes beyond simply reading the abstract. It involves a deep dive into the patent’s claims to understand the precise scope of protection being sought, analyzing citation patterns to identify influential technologies, and mapping patent families to understand a competitor’s global filing strategy.

Advanced techniques like patent landscaping can provide a visual representation of the competitive environment, showing clusters of innovation, identifying key players, and highlighting areas with sparse patent coverage—the “white spaces” that represent opportunities for your own R&D.

Tools of the Trade: The Role of Intelligence Platforms

Manually sifting through millions of patent documents is an impossible task. The rise of sophisticated, AI-driven patent intelligence platforms has democratized this process, providing powerful analytical tools that were once the exclusive domain of large, specialized teams.

Platforms like DrugPatentWatch are specifically designed for the pharmaceutical industry, providing a fully integrated database that combines patent information with critical regulatory, litigation, and clinical trial data.17 Such a platform allows a company to:

- Manage its Portfolio: Anticipate patent expiration dates, identify potential generic suppliers, and inform portfolio management decisions.

- Conduct Competitive Intelligence: Assess the litigation history of patent challengers, track the research paths of competitors by monitoring their patent applications and clinical trials, and set up daily email alerts for specific drugs or technologies.17

- Identify Market Opportunities: Use biopharmaceutical forecasting tools to discover potential new therapeutic indications for existing drugs and identify the first generic companies to challenge a patent.

The availability of these powerful tools fundamentally changes the role of a company’s IP department. It elevates it from a reactive, legal cost center focused on filing and prosecution to a proactive, strategic business intelligence unit. The modern IP counsel is no longer just a legal expert; they are a strategic advisor who uses patent data to provide critical insights to R&D, business development, and executive leadership. This shift enables even smaller biotech firms to “punch above their weight,” allowing them to monitor the activities of global giants, identify niche opportunities, and build a strong IP position before larger competitors can react. This, in turn, forces large pharma to become more agile and data-driven in its own strategic planning, creating a more dynamic and competitive innovation ecosystem.

Section 8: The Next Wave: Future-Proofing Your IP Strategy

The global pharmaceutical IP landscape is in a state of constant flux, shaped by disruptive technologies, evolving scientific paradigms, and shifting political winds. A strategy built for today’s challenges will be obsolete tomorrow. Future-proofing your IP strategy requires a forward-looking perspective that anticipates and adapts to the next wave of innovation and the new legal dilemmas it will inevitably create.

The AI Revolution: New Drugs, New Dilemmas

The most transformative force currently reshaping the pharmaceutical industry is artificial intelligence (AI). AI and machine learning algorithms are revolutionizing drug discovery, dramatically accelerating the process of identifying novel drug candidates. AI systems can analyze vast biological and chemical datasets to predict protein structures, design new molecular compounds, and identify promising therapeutic targets with a speed and accuracy that is impossible for humans alone.66 This technological leap is slashing preclinical development timelines, with some AI-driven projects moving from target identification to a preclinical candidate in as little as 18 months—a process that traditionally takes 5 to 6 years.

While this acceleration promises a new era of medical breakthroughs, it also creates unprecedented challenges for a patent system designed for human-centric innovation.

The Inventorship Crisis: Can a Machine Invent?

The central legal dilemma posed by AI is the question of inventorship. U.S. patent law, and the laws of most other major jurisdictions, are clear: an inventor must be a “natural person”. This principle was firmly cemented in the landmark Thaler v. Vidal case, where courts in the U.S., UK, and Europe rejected patent applications that listed an AI system named DABUS as the sole inventor.

However, the reality of modern R&D is that AI is rarely the sole inventor; it is a powerful tool used by human scientists. Recognizing this, the USPTO issued guidance in 2024 clarifying that inventions created with the assistance of AI are patentable, provided that a human researcher has made a “significant contribution” to the conception of the invention.

This “significant human contribution” standard is now the critical threshold. It means that to secure and defend a patent for an AI-assisted discovery, a company must be able to prove the active and inventive involvement of its human scientists. This could include :

- Curating and structuring the training data used by the AI model.

- Designing the specific problem or query posed to the AI.

- Interpreting the AI’s output and using scientific judgment to select the most promising candidates from a list of AI-generated options.

- Designing and conducting the experiments needed to validate the AI’s predictions.

This legal requirement is creating an entirely new discipline of strategic documentation. The quality of a company’s research records—lab notebooks, meeting minutes, internal reports—and its ability to construct a compelling narrative of human-AI collaboration will become as crucial as the scientific data itself in defending a patent’s validity. A competitor challenging such a patent will inevitably argue that the human contribution was trivial and that the AI performed all the truly inventive work. The patent holder’s ability to rebut this claim will depend on meticulous, contemporaneous documentation that demonstrates human ingenuity at every critical step of the discovery process. Companies must begin training their scientists in this new form of “legal-scientific” documentation to future-proof their AI-generated IP.

Patentability Challenges for AI-Generated Inventions

Beyond inventorship, AI-generated drugs face heightened scrutiny under the traditional patentability criteria of novelty and non-obviousness. An AI model trained on vast public databases of known chemical compounds may inadvertently generate a molecule that is structurally similar or identical to something in the prior art, thus failing the novelty test. Similarly, determining whether an AI’s output would have been “obvious” to a person skilled in the art is a complex legal question that courts are only beginning to grapple with.

The Future of Biologics, Personalized Medicine, and Beyond

The technological shift is not limited to AI. The rise of biologics—large, complex molecules like monoclonal antibodies and cell and gene therapies—has already altered the IP landscape. Compared to traditional small-molecule drugs, biologics are often protected by more extensive and complex patent thickets, covering not just the molecule itself but also the specific cell lines used to produce it and intricate manufacturing processes.52

Looking further ahead, the advent of personalized medicine, where treatments are tailored to an individual’s genetic makeup, will continue to test the boundaries of patent law. In this new paradigm, the data itself—the genomic information and the algorithms used to analyze it—becomes an immensely valuable form of intangible asset, raising new questions about data ownership, privacy, and the patentability of diagnostic methods.

In response to the spiraling costs and complexities of R&D in these cutting-edge fields, the industry is also seeing a trend toward more collaborative innovation models. Open innovation platforms and large-scale public-private partnerships (PPPs) are becoming more common as a way to share pre-competitive research, pool resources, and de-risk the early stages of drug development.69

Conclusion: The Proactive, Integrated Future of Pharmaceutical IP

The journey through the intricate world of global pharmaceutical patent protection reveals a clear and urgent imperative: in an industry defined by billion-dollar risks and relentless competition, a reactive, siloed approach to intellectual property is a recipe for failure. The most successful and resilient companies of the future will be those that treat patent strategy not as a legal backstop, but as a core, proactive, and deeply integrated business function.

Effective global patent protection in the modern era demands a holistic approach. It requires a legal team that understands the nuances of Section 3(d) in India and the UPC in Europe. It requires a clinical development team that designs trials with an eye toward generating the efficacy data needed to support secondary patents. It requires a business development team that uses patent intelligence to hunt for acquisition targets and forecast market shifts. And it requires a C-suite that sees the IP portfolio not as a collection of legal documents, but as a strategic arsenal to be deployed, defended, and monetized to drive long-term growth.

From architecting a cost-effective global filing strategy using the PCT, to navigating the unique minefields of emerging markets, to building a formidable patent fortress around a blockbuster asset, and preparing for the disruptive force of AI, the challenges are immense. But for those who master this complex discipline, the rewards are equally profound: the ability to protect groundbreaking innovation, deliver transformative medicines to patients, and secure a dominant and sustainable position in the global marketplace.

Key Takeaways

- Patents are a Core Business Asset, Not Just a Legal Shield: The immense cost of R&D (over $2 billion per drug) and the short effective market exclusivity period (7-8 years) make a proactive, offensive patent strategy essential for financial survival and funding future innovation.

- The PCT is a Critical Financial and Strategic Tool: The Patent Cooperation Treaty’s 30-month delay before national phase entry is not just a procedural convenience; it is a vital mechanism for deferring major costs, de-risking investment, and aligning IP expenditures with key R&D milestones.

- Emerging Markets Require Bespoke Strategies: One-size-fits-all patent strategies will fail in key growth markets. Success requires a deep understanding of country-specific rules like China’s “China-first” patent term extension, India’s strict “enhanced efficacy” standard (Section 3(d)), and Brazil’s “patent paradox.”

- The UPC Has Reshaped European Litigation: The Unified Patent Court creates a high-risk, high-reward environment. While it offers powerful pan-European enforcement, the threat of a single, central revocation action makes building resilient, multi-layered patent portfolios (“thickets”) a more critical defensive strategy in Europe.

- Patent Intelligence is a Competitive Weapon: Systematically monitoring and analyzing competitor patent filings through platforms like DrugPatentWatch provides an invaluable early warning system for new competitive threats and a roadmap to “white space” opportunities for a company’s own R&D.

- AI is Forcing a Rethink of Inventorship and Documentation: While AI is accelerating drug discovery, current patent law requires a “significant human contribution” for an invention to be patentable. This elevates the strategic importance of meticulously documenting the human-AI collaborative process as a preemptive legal defense.

- Enforcement is a Deterrent: A company’s willingness to aggressively enforce its patents against infringers does more than protect against a single threat; it sends a powerful signal that raises the perceived risk for counterfeiters and helps secure the integrity of the entire supply chain.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. Our company is a small biotech with a promising lead compound but limited funds. What is the most capital-efficient way to begin building a global patent strategy?

The most capital-efficient approach is to leverage a two-pronged strategy centered on the U.S. Provisional Patent Application and the Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT). First, file a provisional application in the U.S. This is a relatively low-cost filing that secures a priority date for your invention for 12 months without the expense of formal claims. Within that 12-month period, file a single PCT application. This extends your option to seek patent protection in 158 member countries for an additional 30 months from your original priority date. This combined strategy gives you a total of 42 months (3.5 years) before you must incur the significant costs of national filing and translation fees, providing a crucial window to gather more clinical data, secure funding, or find a strategic partner.

2. We are planning to launch our new drug in the U.S. and Europe first. What are the biggest risks of delaying our patent filing in China?

The biggest risk is forfeiting the opportunity for up to five years of additional market exclusivity under China’s new Patent Term Compensation system. This system is designed to reward companies that make China the first country in the world for marketing approval. By prioritizing a U.S. or EU launch, you become ineligible for this valuable extension. Given that China is the world’s second-largest pharmaceutical market, this is a significant commercial trade-off. A modern global strategy must now weigh the benefits of a traditional Western launch sequence against the potential for a substantially longer monopoly period in China.

3. What is the single most important legal doctrine to understand when considering a secondary patent (e.g., for a new formulation) in India?

The single most important doctrine is Section 3(d) of the Indian Patents Act. This provision explicitly prevents the patenting of new forms of known substances unless the applicant can prove that the new form results in a “significant enhancement of the known efficacy”. This is a much higher bar than in the U.S. or Europe, where novelty and non-obviousness might suffice. As the Novartis v. Union of India case demonstrated, simply showing improved bioavailability is not enough; you must provide concrete evidence of improved therapeutic effect. This means your legal strategy for India must be directly integrated with your clinical development strategy from the outset.

4. How has the new Unified Patent Court (UPC) in Europe changed the strategic value of building a “patent thicket”?

The UPC has arguably made patent thickets a more necessary defensive strategy in Europe. The court’s centralized system creates a “single point of failure” risk; a competitor can potentially invalidate a key patent across 17 countries with a single successful revocation action. For a drug protected by only one or two patents, this is an existential threat. A patent thicket—a portfolio of multiple patents covering different aspects like formulation, dosage, and manufacturing—creates redundancy. Even if the primary compound patent is centrally revoked, other patents in the thicket may survive, preserving some level of market exclusivity and mitigating the catastrophic impact of a single legal loss.

5. My R&D team is heavily using an AI platform to generate novel drug candidates. What is the most critical step we need to take now to ensure these discoveries will be patentable?

The most critical step is to implement a rigorous system for documenting the “significant human contribution” at every stage of the discovery process. Current patent law does not recognize AI as an inventor, so you must be able to prove that your human scientists were the true “masters of the tool”. This means meticulously recording how your scientists framed the problem for the AI, how they curated the training data, how they applied their expertise to interpret and select from the AI’s outputs, and how they conceived of the experiments to validate the results. These records are no longer just scientific notes; they are your primary legal defense against a future challenge that your patent is invalid for lack of a human inventor.

References

- The history and economics of pharmaceutical patents – Emerald Insight, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.emerald.com/books/edited-volume/13485/chapter/84098938/The-history-and-economics-of-pharmaceutical

- Patent Defense Isn’t a Legal Problem. It’s a Strategy Problem. Patent Defense Tactics That Every Pharma Company Needs – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/patent-defense-isnt-a-legal-problem-its-a-strategy-problem-patent-defense-tactics-that-every-pharma-company-needs/

- Problems with Drug Patents – DebateUS, accessed August 5, 2025, https://debateus.org/problems-with-drug-patents/

- History of Patent Medicine – Hagley Museum, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.hagley.org/research/digital-exhibits/history-patent-medicine

- A History of Pharmaceuticals – Milken Institute Review, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.milkenreview.org/articles/a-history-of-pharmaceuticals?IssueID=58

- The history and economics of pharmaceutical patents – ResearchGate, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/235303942_The_history_and_economics_of_pharmaceutical_patents

- TRIPS, Pharmaceutical Patents, and Access to Essential Medicines: A Long Way From Seattle to Doha – Chicago Unbound, accessed August 5, 2025, https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/cjil/vol3/iss1/6/

- Medicines, Patents, and TRIPS: Has the intellectual property pact opened a Pandora’s box for the Pharmaceuticals industry in: Health and Development – IMF eLibrary, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.elibrary.imf.org/display/book/9781589063419/ch06.xml

- Intellectual Property Protection And The Pharmaceutical Industry | Oblon, McClelland, Maier & Neustadt, L.L.P., accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.oblon.com/publications/intellectual-property-protection-and-the-pharmaceutical-industry

- What is the impact of intellectual property rules on access to medicines? A systematic review, accessed August 5, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9013034/

- WIPO/ECTK/SOF/01/2.6: Recent Developments and Challenges in …, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.wipo.int/edocs/mdocs/innovation/en/wipo_ectk_sof_01/wipo_ectk_sof_01_2_6.doc

- A “Calibrated Approach”: Pharmaceutical FDI and the Evolution of Indian Patent Law – USITC’s, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.usitc.gov/publications/332/journals/pharm_fdi_indian_patent_law.pdf

- Patent Considerations for Drug Patents in Developing Countries, accessed August 5, 2025, https://patentpc.com/blog/patent-considerations-drug-patents-developing-countries

- PCT – The International Patent System – WIPO, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.wipo.int/en/web/pct-system

- Patent Cooperation Treaty – Wikipedia, accessed August 5, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Patent_Cooperation_Treaty

- Foreign Patent Filing: 5 Strategies to Develop an International Patent Portfolio – Triangle IP, accessed August 5, 2025, https://triangleip.com/patent-filing-strategies/

- DrugPatentWatch | Software Reviews & Alternatives – Crozdesk, accessed August 5, 2025, https://crozdesk.com/software/drugpatentwatch

- The Double-Edged Sword: Opportunities and Challenges in China’s Patent Litigation System – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-double-edged-sword-opportunities-and-challenges-in-chinas-patent-litigation-system/

- Filing Strategies for Maximizing Pharma Patents: A Comprehensive Guide for Business Professionals – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/filing-strategies-for-maximizing-pharma-patents/

- 2750-Patent Term Extension for Delays at other Agencies under 35 U.S.C. 156 – USPTO, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.uspto.gov/web/offices/pac/mpep/s2750.html

- Applying for a patent | epo.org, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.epo.org/en/applying

- How to apply for a patent | epo.org, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.epo.org/en/new-to-patents/how-to-apply-for-a-patent

- Unitary Patent Guide updated | epo.org, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.epo.org/en/news-events/news/unitary-patent-guide-updated

- UPC patent infringement: recent updates for the life sciences sector, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.taylorwessing.com/en/synapse/2025/two-years-of-upc-patent-litigation/upc-patent-infringement

- (Cross-border) jurisdiction Archives – Kluwer Patent Blog, accessed August 5, 2025, https://patentblog.kluweriplaw.com/category/cross-border-jurisdiction/

- Showdown in Munich: Federal Patent Court revokes Xarelto patent, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.juve-patent.com/cases/showdown-in-munich-federal-patent-court-revokes-xarelto-patent/

- Patents, Pricing, and Access to Essential Medicines in Developing Countries, accessed August 5, 2025, https://journalofethics.ama-assn.org/article/patents-pricing-and-access-essential-medicines-developing-countries/2009-07

- Pharmaceutical Patenting in India | candcip, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.candcip.com/pharmaceutical-patenting-in-india

- China’s First “5-Year Extension” Case Under the Patent Term …, accessed August 5, 2025, https://se1910.com/chinas-first-5-year-extension-case-under-the-patent-term-compensation-system/

- China introduces pharmaceutical patent term compensation system – Asia IP, accessed August 5, 2025, https://asiaiplaw.com/article/china-introduces-pharmaceutical-patent-term-compensation-system